Abstract

In patients with bladder cancer (BC), the association between ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5 (ST3GAL5) expression and clinical outcomes, particularly regarding muscle-invasive disease, high tumor grade and prognosis, remain unknown. In the present study, the expression of ST3GAL5 and its association with clinical outcomes in patients with BC was analyzed using various public bioinformatics databases. The difference in ST3GAL5 expression between BC and healthy bladder tissues was also evaluated using data from the Oncomine database, The Cancer Genome Atlas and Gene Expression Omnibus database. The differences in ST3GAL5 expression between muscle invasive BC (MIBC) and non-muscle invasive BC (NMIBC), and high- and low-grade BC were also analyzed. Furthermore, genes that were positively co-expressed with ST3GAL5 in patients with BC were identified from the intersection between the Oncomine, Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2 and UALCAN databases. Enrichment analysis by Gene Ontology, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, Reactome pathway enrichment analyses and a gene-concept network was performed using R package. Gene set enrichment analysis was also performed to assess the signaling pathways influenced by the high and low expression of ST3GAL5 in BC. The results indicated that ST3GAL5 expression was significantly lower in BC tissues compared with normal bladder tissues (P<0.05). Furthermore, ST3GAL5 expression in MIBC and high-grade BC was significantly lower compared with NMIBC and low-grade BC (P<0.05), respectively. The results from Kaplan-Meier survival analysis result demonstrated that ST3GAL5 downregulation was associated with poor survival in patients with BC (P<0.05). Taken together, these findings suggested that ST3GAL5 may be considered as an anti-oncogene in BC, could represent a potential predictive and prognostic biomarker for BC and may be a molecular target for tumor therapy.

Keywords: bladder cancer; ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5; methylation; muscle invasive; high grade; prognosis

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is the 7th most common cancer affecting men in the world and the 11th most common cancer in the total population (1). BC affects ~3.4 million people worldwide, with 430,000 new cases diagnosed in 2015 (2). In the United States, 80,470 new cases of BC and 17,670 BC-associated mortality cases were expected to occur in 2019 (3). Furthermore, BC incidence and mortality rates vary across countries due to the differences in risk factors, detection and diagnostic practices and treatments availability (4). The most common type of BC is bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), which accounts for ~90% of all cases (5). In addition, BLCA can be low grade or high grade (6). Low grade BLCA rarely results in cancer invasion in the bladder muscular wall or metastasis to other parts of the body, and patients rarely succumb to low grade BLCA; however, the majority of BLCA-associated mortality cases result from the high-grade disease (6). BC can also be stratified into muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) and non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), according to invasion of the muscularis propria (6). In particular, ~75% of newly diagnosed BC cases are non-invasive, including Stages Ta, Tis or T1, based according to the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer (UICC/AJCC) staging system (8th edition) (4). NMIBC exhibits a high prevalence due to the long-term survival rates and the lower risk of cancer-specific mortality compared with patients with MIBC (6). Furthermore, improvements in the early detection and treatment of BC have increased patient survival status; however, BC-associated mortality remains high. It is therefore crucial to identify novel biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets to improve the clinical treatment of patients with BLCA.

ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5 (ST3GAL5) is a protein coding gene, which catalyzes the formation of ganglioside monosialodihexosylganglioside (GM3) (7). Ganglioside GM3 is known to participate in the induction of cell differentiation, modulation of cell proliferation, maintenance of fibroblast morphology, signal transduction and integrin-mediated cell adhesion (8). Furthermore, ganglioside GM3 is associated with numerous types of tumor, including lung cancer, brain cancer and melanomas, and was reported to significantly influence cancer development and progression (9–12). GM3 is also upregulated in several types of cancer, such as lung and brain cancer, and melanoma, and can be used as a tumor-associated carbohydrate antigen in immunotherapy (9,10). In addition, GM3 inhibits tumor cell proliferation through angiogenesis inhibition or decrease in cell motility (9,11,13). However, the expression profile and functional role of ST3GAL5 in BLCA remain unclear. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first data mining study to predict the potential role of ST3GAL5 in BLCA, based on publicly available gene expression and clinical outcome databases.

In the present study, the expression of ST3GAL5 and its clinical outcomes were investigated in patients with BLCA using various public gene expression and survival datasets. In addition, the DNA methylation and gene expression patterns of ST3GAL5 in BLCA were analyzed. Furthermore, enrichment analyses were performed on genes that were positively co-expressed with ST3GAL5 in BLCA, and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was also used. The findings from the present study hypothesized that ST3GAL5 downregulation may influence BLCA carcinogenesis, suggesting that ST3GAL5 may represent a novel therapeutic target in BLCA.

Materials and methods

Data set acquisition and processing

All data were acquired and processed from the public bioinformatics databases Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) (14), Oncomine (www.oncomine.org) (15,16), Tumor IMmune Estimation Resource (TIMER; cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer) (17,18), Gene Expression across Normal and Tumor tissue (GENT; medical-genome.kribb.re.kr/GENT) (19,20), University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) Xena (xenabrowser.net) (21), Gene expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2 (GEPIA2; gepia2.cancer-pku.cn) (22) and Kaplan-Meier plotter (kmplot.com/analysis) (23). The BLCA microarray datasets GSE13507 (24), GSE120736 (25) and GSE31684 (25,26) were downloaded from the GEO database to analyze the expression of ST3GAL5. The Lee Bladder (27), Blaveri Bladder 2 (28), Sanchez-Carbayo Bladder 2 (29) and Stransky Bladder (30) datasets from the Oncomine database were extracted and processed using the R package ‘ROncomine’ v0.0.0.9 (github.com/yikeshu0611/ROncomine). The datasets from Genomic Data Commons (GDC; gdc.cancer.gov), The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; cancergenome.nih.gov) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx; commonfund.nih.gov/GTEx) databases were downloaded using UCSC Xena browser tool (xenabrowser.net/). In the Oncomine database, the default settings were used and the threshold parameters were as follows: P<1×10−4, |fold change|>2 and gene rank in the top 10%. In the GENT database, data were analyzed using the Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array platform (http://www.affymetrix.com/support/technical/byproduct.affx?product=hg-u133-plus).

Enrichment analysis

The Gene Ontology (GO) terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis were determined using the R package ‘clusterProfiler’ v3.14.3 (31), and the Reactome pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the R package ‘ReactomePA’ v1.30.0 (32). Subsequently, the gene-concept network analysis were performed using the R package ‘clusterProfiler’ and ‘ReactomePA’. Microarray datasets of accession number GSE83586 (33) were downloaded from the GEO database in order to investigate the relevant signaling pathways using GSEA. According to the mean expression value of ST3GAL5 in the GSE83586 dataset, the matrix file was divided into high- and low-expression groups, and GSEA was performed using GSEA 4.02 software (34) in order to determine the KEGG pathways (c2.cp.kegg.v7.0.symbols) associated with high and low expression of ST3GAL5. Gene set permutations were performed 1,000 times for each analysis. The false discovery rate <0.25, |normalized enrichment score| >1 and nominal P<0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Subsequently, replotting of the output from the GSEA report folder was conducted using the R package ‘Rtoolbox’ v1.4 (github.com/PeeperLab/Rtoolbox).

Data management and statistical analysis

Cancer staging was assessed using the 8th edition of the UICC/AJCC cancer staging system. The gene expression profile and survival data were downloaded, converted, constructed and managed using Microsoft Office Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation). All statistical analyses were performed using R software (www.r-project.org; v3.6.1). The box plot was constructed using the R package ‘ggplot2’ v3.2.1 (35). The Cnetplot was constructed using the R package ‘clusterProfiler’ and ‘ReactomePA’. Student's t-test was used to compare the means of two independent samples, and one-way ANOVA was used to compare the means of multiple independent samples followed by Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazard models were used for survival analysis by using R package ‘survival’ v3.1.8 and ‘survminer’ v0.4.6. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was performed to adjust for covariate effects, and stratification analysis was used to reduce the potential confounding effect on the estimation of hazard ratio (HR). Missing data were coded and excluded from the analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

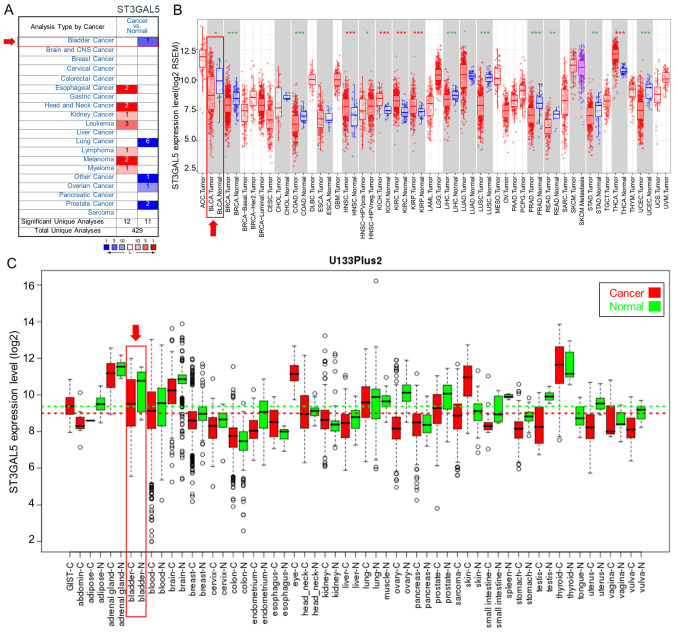

Expression of ST3GAL5 in different types of cancer

The differences in ST3GAL5 expression between various types of cancer and paired healthy tissues were compared from three independent bioinformatics databases. In the Oncomine database, the comparison between each type of cancer and healthy tissues identified the downregulation of ST3GAL5 expression in bladder, lung, ovarian, prostate and ‘other’ cancers, and the upregulation of ST3GAL5 expression in esophageal cancer, head and neck cancer, kidney cancer, leukemia, lymphoma, melanoma and myeloma (Fig. 1A). ST3GAL5 expression was also analyzed in tumor and healthy tissues using TCGA data and the TIMER tool (Fig. 1B). Among the different types of cancer, 10 presented significantly lower ST3GAL5 expression, and five had significantly higher ST3GAL5 expression compared with paired healthy tissues (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, data from the GENT database indicated that ST3GAL5 expression was downregulated in certain cancer types, including bladder, blood, brain, breast, liver, ovary, prostate, stomach and testicular cancers (Fig. 1C). The three databases demonstrated the downregulation of ST3GAL5 in different cancer types. Furthermore, ST3GAL5 expression in BLCA tissues was significantly decreased in the three databases compared with paired healthy tissues.

Figure 1.

Expression of ST3GAL5 in different types of cancer. (A) Expression of ST3GAL5 in 20 types of cancer vs. healthy tissues from the Oncomine database. The cell color is determined by the best gene rank percentile for the analysis within the cell. Red color represents overexpression and blue color represents downregulation. (B) Expression of ST3GAL5 in different types of tumor vs. healthy tissues in data from the Tumor IMmune Estimation Resource website. Boxes represent the median, 25 and 75th percentiles, and each dot represents expression of samples. (C) Expression of ST3GAL5 in tumor vs. healthy tissues from the Gene Expression across Normal and Tumor tissue database. Boxes represent the median, 25 and 75th percentiles, and dots represent outliers. ST3GAL5, ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5.

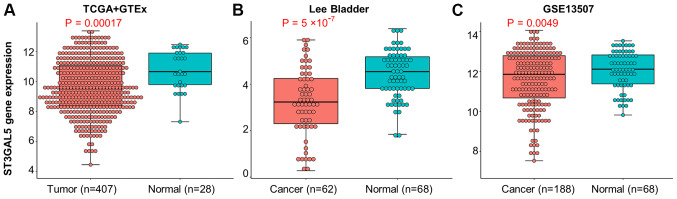

Expression of ST3GAL5 in BLCA and healthy bladder tissues

To observe the expression of ST3GAL5 in BLCA, three independent datasets from TGCA + GTEx, Oncomine and GEO databases were analyzed. Data from TCGA + GTEx database were acquired using the USCS Xena browser tool. Moreover, data from the Oncomine Lee Bladder dataset were extracted and processed using the R package ‘ROncomine’. The GEO datasets were acquired from the accession number GSE13507. The results demonstrated a significant downregulation of ST3GAL5 in BLCA tissues compared with healthy bladder tissues (Fig. 2A-C).

Figure 2.

Expression of ST3GAL5 between BLCA and healthy bladder tissues. (A) Expression of ST3GAL5 in BLCA from TCGA + GTEx databases, the data was downloaded from UCSC Xena browser tool. (B) Expression of ST3GAL5 in BLCA from the Oncomine database, the threshold was designed using default settings parameters: P<1×10−4, |fold-change|>2, and gene rank in top 10%. (C) The expressions of ST3GAL5 in BLCA from the GEO database under accession numbers GSE13507. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression; UCSC, University of California, Santa Cruz; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; ST3GAL5, ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5.

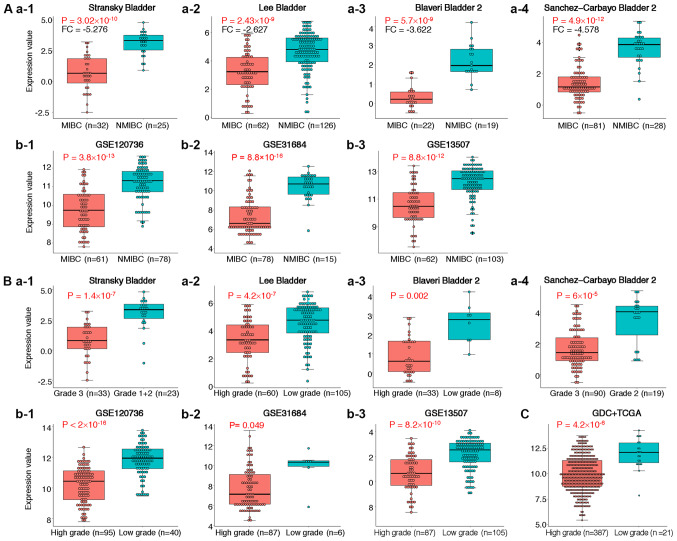

Expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC and high-grade BLCA tissues

To further determine of ST3GAL5 expression in MIBC and high-grade BLCA, four individual datasets from the Oncomine database were analyzed (Table I). The results from meta-analysis demonstrated that ST3GAL5 was significantly downregulated in MIBC across the four datasets (Table I). In these four datasets, ST3GAL5 was significantly downregulated in MIBC and high-grade BLCA (Fig. 3A-a1-4 and B-a1-4). The data acquired from the GEO datasets GSE120736, GSE31684 and GSE13507 also presented significantly lower expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC and high-grade BLCA (Fig. 3A-b1-3 and B-b1-3, respectively). In addition, decreased expression of ST3GAL5 in high-grade BLCA tissues was reported in the GDC + TCGA BLCA datasets, using the USCS Xena browser tool (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results demonstrated that ST3GAL5 downregulation was associated with MIBC and high-grade BLCA.

Table I.

Comparison of ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5 across four datasets in the downregulation analysis from the Oncomine database.

| Dataset | FC | P-value | Gene rank | MIBC | NMIBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanchez-Carbayo Bladder 2 | −9.324 | 2.43×10−9 | 315 (in top 3%) | 32 | 25 |

| Blaveri Bladder 2 | −3.622 | 2.86×10−9 | 66 (in top 2%) | 62 | 126 |

| Stransky Bladder | −5.276 | 3.02×10−10 | 3 (in top 1%) | 22 | 19 |

| Lee Bladder | 2.627 | 2.43×10−12 | 7 (in top 1%) | 81 | 28 |

Meta-analysis: Median Rank=36.5, P=2.64×10−9. FC, fold-change; MIBC, muscle invasive bladder cancer; NMIBC, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Figure 3.

Expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC and high-grade BLCA. (A) Expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC compared with NMIBC. (A-a-1) Stansky Bladder dataset from the Oncomine database reported lower expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC. (A-a-2) Lee Bladder dataset from the Oncomine database reported lower expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC. (A-a-3) Blaveri Bladder 2 dataset from the Oncomine database reported lower expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC. (A-a-4) Sanchez-Carbayo Bladder 2 dataset from the Oncomine database reported lower expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC. (A-b-1) GSE120736 dataset from the GEO database presented lower expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC. (A-b-2) GSE31684 dataset from the GEO database presented lower expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC. (A-b-3) GSE13507 dataset from the GEO database presented lower expression of ST3GAL5 in MIBC. (B) Expression of ST3GAL5 in high grade BLCA compared with low grade BLCA. (B-a-1) Stansky Bladder dataset from the Oncomine database demonstrated lower expression of ST3GAL5 in high grade BLCA. (B-a-2) Lee Bladder dataset from the Oncomine database demonstrated lower expression of ST3GAL5 in high grade BLCA. (B-a-3) Blaveri Bladder 2 dataset from the Oncomine database demonstrated lower expression of ST3GAL5 in high grade BLCA. (B-a-4) Sanchez-Carbayo Bladder 2 from the Oncomine database demonstrated lower expression of ST3GAL5 in high grade BLCA. (B-b-1) GSE120736 dataset from the GEO database presented lower expression of ST3GAL5 in high grade BLCA. (B-b-2) GSE31684 from the GEO database presented lower expression of ST3GAL5 in high grade BLCA. (B-b-3) GSE13507 from the GEO database presented lower expression of ST3GAL5 in high grade BLCA. (C) GDC + TCGA-BLCA dataset showed lower expression of ST3GAL5 in high grade BLCA. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; ST3GAL5, ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5; MIBC, muscle invasive bladder cancer; NMIBC, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; GDC, Genomic Data Commons.

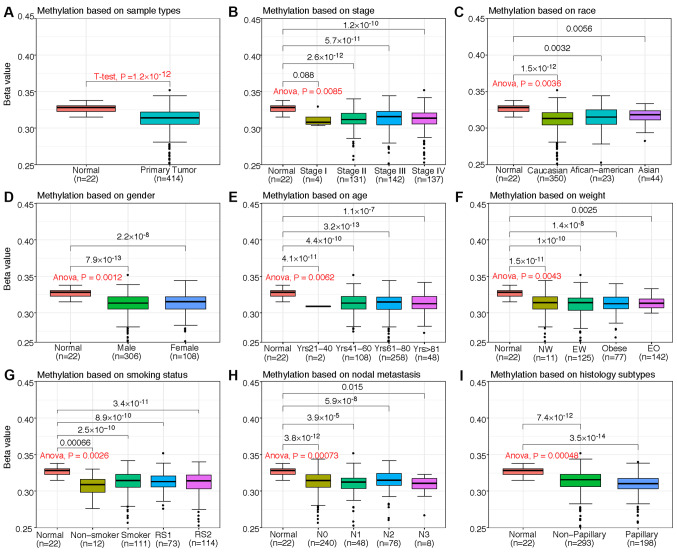

Association between ST3GAL5 expression and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with BLCA

The present study investigated the association between ST3GAL5 mRNA expression, promoter methylation level and the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with BLCA from the TCGA-BLCA dataset by using the Xena web tool. Compared with healthy bladder tissues, the expression of ST3GAL5 was downregulated in tissues from primary tumors, Stage IV cancer, extreme weight, smoking for >15 years, non-papillary tumors and nodal metastasis status N1 (Table II). Furthermore, ST3GAL5 expression was downregulated in male and female patients with BLCA. However, the level of ST3GAL5 promoter methylation in patients with BLCA was significantly decreased, regardless of patient clinicopathological characteristics, including cancer stage, ethnicity, sex, age, weight, smoking status, nodal metastasis status and histological subtype compared with healthy patients (Fig. 4). Therefore, it was hypothesized that decreased ST3GAL5 promoter methylation may be positively associated with numerous clinicopathological characteristics of patients with BLCA.

Table II.

Association between ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5 expression and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with bladder urothelial carcinoma.

| Expression value | P-value | ||||

| Parameter | Sample (n) | Mean | SD | t-test or ANOVA | Multiple comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type | 0.023 | ||||

| Healthy | 21 | 9.772 | 1.979 | ||

| Primary tumor | 408 | 8.855 | 1.792 | ||

| Cancer stage | 1.88×10−6 | ||||

| Healthy | 21 | 9.772 | 1.979 | ||

| Primary tumor | |||||

| Stage I | 4 | 10.241 | 1.705 | 1.000 | |

| Stage II | 130 | 9.470 | 1.839 | 1.000 | |

| Stage III | 140 | 8.644 | 1.761 | 0.067 | |

| Stage IV | 134 | 8.432 | 1.676 | 0.014 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.121 | ||||

| Healthy | 21 | 9.772 | 1.979 | ||

| Primary tumor | |||||

| Caucasian | 347 | 8.852 | 1.817 | 0.151 | |

| African-American | 21 | 9.147 | 1.745 | 1.000 | |

| Asian | 40 | 8.715 | 1.829 | 0.192 | |

| Sex | 0.067 | ||||

| Healthy | 21 | 9.772 | 1.979 | ||

| Primary tumor | |||||

| Male | 302 | 8.821 | 1.846 | 0.064 | |

| Female | 106 | 8.945 | 1.718 | 0.174 | |

| Age, years | 0.018 | ||||

| Healthy | 21 | 9.772 | 1.979 | ||

| Primary tumor | |||||

| 21-40 | 2 | 10.690 | 0.396 | 1.000 | |

| 41-60 | 106 | 9.156 | 1.813 | 1.000 | |

| 61-80 | 253 | 8.700 | 1.760 | 0.095 | |

| >80 | 47 | 8.919 | 2.024 | 0.737 | |

| Weight | 0.012 | ||||

| Healthy | 21 | 9.772 | 1.979 | ||

| Primary tumor | |||||

| Normal weight | 140 | 9.144 | 1.860 | 1.000 | |

| Extreme weight | 124 | 8.509 | 1.828 | 0.035 | |

| Obese | 75 | 8.961 | 1.670 | 0.720 | |

| Extreme obese | 10 | 8.986 | 1.889 | 1.000 | |

| NA | 59 | ||||

| Smoking habits | 0.028 | ||||

| Healthy | 21 | 9.772 | 1.979 | ||

| Primary tumor | |||||

| Non-smoker | 12 | 9.061 | 1.967 | 1.000 | |

| Smoker | 109 | 9.075 | 1.797 | 1.000 | |

| Reformed smoker 1 (<15 years) | 72 | 8.947 | 1.716 | 0.700 | |

| Reformed smoker 2 (>15 years) | 113 | 8.509 | 1.888 | 0.039 | |

| NA | 102 | ||||

| Nodal metastasis status | 0.004 | ||||

| Healthy | 21 | 9.772 | 1.979 | ||

| Primary tumor | |||||

| N0 | 237 | 9.033 | 1.857 | 0.721 | |

| N1 | 46 | 8.177 | 1.759 | 0.008 | |

| N2 | 75 | 8.635 | 1.584 | 0.109 | |

| N3 | 8 | 8.631 | 1.693 | 1.000 | |

| NA | 42 | ||||

| Histological subtypes | 1.66×10−7 | ||||

| Healthy | 21 | 9.772 | 1.979 | ||

| Primary tumor | |||||

| Non-papillary | 271 | 8.544 | 1.654 | 0.007 | |

| Papillary | 132 | 9.525 | 1.964 | 1.000 | |

| NA | 5 | ||||

In multiple comparisons, the healthy group represented the reference group. Patients with body mass index (BMI) 18–24 were classified as ‘Normal weight’, those with BMI 25–29 were classified as ‘Extreme weight’, those with BMI 30–39 were classified as ‘Obese’ and those with BMI ≥40 as ‘Extreme obese’. Data regarding weight, smoking habits, nodal metastasis status and histological subtype were missing (NA) for some patients with primary tumor. N0, No regional lymph node metastasis; N1, Metastases in 1–3 axillary lymph nodes; N2, Metastases in 4–9 axillary lymph nodes; N3, Metastases in ≥10 axillary lymph nodes; NA, not available.

Figure 4.

Box plots from TCGA clinical data according to categorization of the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with BLCA and healthy patients (normal). Promoter methylation of ST3GAL5 in BLCA (different color plot) and healthy (red plot) tissues based on (A) sample type, (B) individual cancer stages, (C) ethnicity, (D) sex, (E) age, (F) weight, (G) smoking status, (H) nodal metastasis status and (I) histological subtype. The β-value for assessment of methylation level ranged from 0 (least methylated) to 1 (most methylated). NW, normal weight; EW, extreme weight; EO, extreme obese; RS1, reformed smoker (<15 years); RS2, reformed smoker (>15 years); TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; ST3GAL5, ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5; Yrs, years; N1, metastases in 1–3 axillary lymph nodes; N2, metastases in 4–9 axillary lymph nodes; N3, metastases in ≥10 axillary lymph nodes.

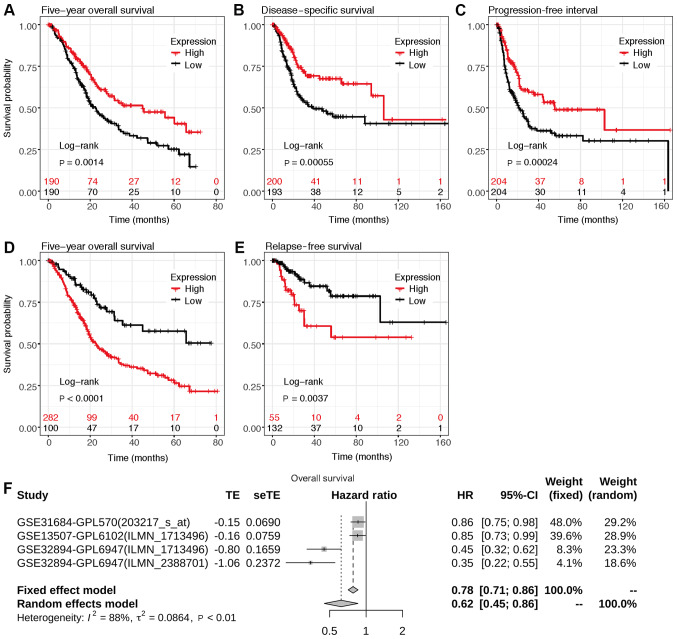

Association between ST3GAL5 expression and survival prognosis in patients with BLCA

To investigate the association between ST3GAL5 expression and survival prognosis in patients with BLCA, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed using data from the GDC, TCGA and GEO databases via the UCSC Xena browser and Kaplan-Meier plotter web tools. The 5-year overall survival (OS), disease specific survival, progression free interval and relapse free survival were all positively associated with lower ST3GAL5 expression in patients with BLCA (Fig. 5A-E).

Figure 5.

Assessment of the 5-year overall survival according to ST3GAL5 expression in patients with BLCA. Survival plot data from the UCSC Xena browse tool, gene expression data and (A) overall survival, (B) disease specific survival and (C) progression free interval information were downloaded from TCGA-BLCA datasets. Survival plots from the KM plotter, gene expression data and (D) overall survival and (E) relapse free survival information were downloaded from the GEO, EGA and TCGA datasets. Analyses focused on ST3GAL5 expression in patients with BLCA. (F) Forest plots of the GEO datasets evaluating association of ST3GAL5 with the overall survival in patients with BLCA using GENT2 web tool. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; ST3GAL5, ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; EGA, European Genome-phenome Archive; GENT, Gene Expression across Normal and Tumor tissue; UCSC, University of California, Santa Cruz; HR, hazard ratio.

Meta-survival analysis of OS was performed using data from GENT2 web (gent2.appex.kr/gent2) tools and depicted as forest plots (Fig. 5F). The results demonstrated that low ST3GAL5 expression was associated with poor OS [P<0.001; HR, 2.934; 95% CI (1.916–4.493); τ2, 0.086; I2, 0.884]. These results indicated the prognostic relevance of ST3GAL5 expression in patients with BLCA.

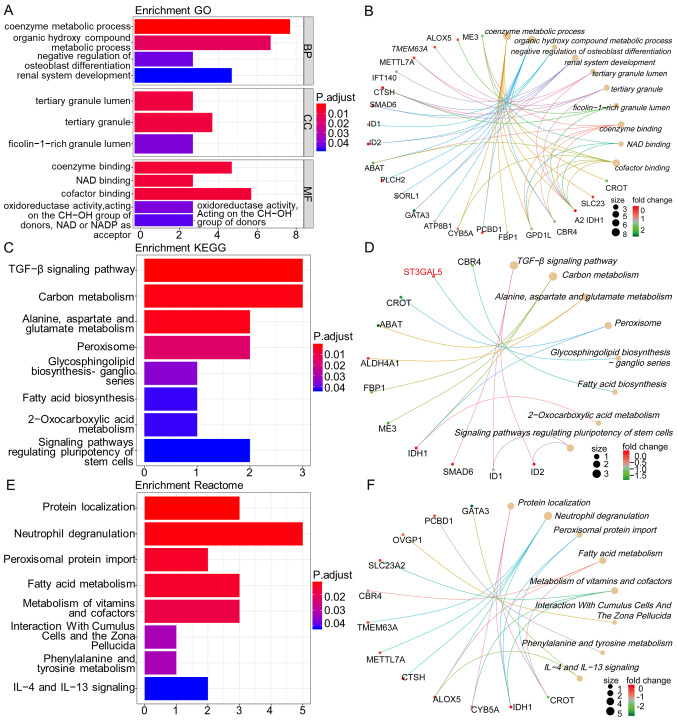

Enrichment analysis genes co-expressed with ST3GAL5 in BLCA samples

The top 250 genes that were positively co-expressed with ST3GAL5 in BLCA samples were identified using Oncomine Stransky Bladder dataset and GEPIA2 and UALCAN web tools. The genes common to these three databases were selected for further analysis. In total, 33 genes were identified as positively co-expressed with ST3GAL5 in BLCA samples. The names of the genes were as follows: [methyltransferase like 7A, SMAD6, ATPase phospholipid transporting 8B1, sortilin related receptor 1, trafficking kinesin protein 1, pterin-4 α-carbinolamine dehydratase 1, cytochrome b5 type A, isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP(+)) 1, fructose-bisphosphatase 1, GATA binding protein 3, cathepsin H, dual specificity phosphatase 2, TP53 target 1, inhibitor of DNA binding (ID) 1, phospholipase C eta 2, solute carrier family (SLC) 14 member 1 (Kidd blood group), arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase, PPFIA binding protein 2, transmembrane protein 63A, 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase, intraflagellar transport 140, SLC23A2, zinc finger protein 211, keratin associated protein 5–9, oviductal glycoprotein 1, family with sequence similarity 13 member A, ID2, carbonyl reductase 4, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like, carnitine O-octanoyltransferase, tubulin tyrosine ligase like 3, aldehyde dehydrogenase 4 family member A1 and malic enzyme 3].

Subsequently, GO, KEGG and Reactome pathway enrichment analyses, and gene-concept network analysis were performed with ST3GAL5 and the 33 positively co-expressed genes by using the R packages ‘clusterProfiler’ and ‘ReactomePA’. GO terms functional enrichment analysis was performed with ST3GAL5 and its associated genes to determine the functions associated with biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF) and cellular components (CC). ST3GAL5 and its co-expressed genes were predominantly associated with ‘coenzyme metabolic process’, ‘organic hydroxy compound metabolic process’, ‘negative regulation of osteoblast differentiation’, ‘renal system development’, ‘tertiary granule lumen’, ‘tertiary granule’, ‘ficolin-1-rich granule lumen’, ‘coenzyme binding’, ‘NAD binding’ and ‘cofactor binding’ (Fig. 6A and B).

Figure 6.

Enrichment analysis of genes co-expressed with ST3GAL5 in BLCA samples. Bar plot showing the GO terms and signaling pathways of ST3GAL5 and its positively co-expressed genes in BLCA (left column). Cnetplot showing the links between genes and biological processes by using GO, KEGG pathways or Reactome pathways as networks (right column). (A) Bar plots of GO terms enrichment. (B) Cnetplot of GO terms. (C) Bar plots of KEGG pathways. (D) Cnetplot of KEGG pathways. (E) Bar plot of Reactome pathways. (F) Cnetplot of Reactome pathways. Length of the bar represents the gene count; the color represents the P-value or adjusted P-value. P Cutoff=0.05, Q Cutoff=0.2, P adjusted method=BH. BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; ST3GAL5, ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; BH, Benjamini-Hochberg.

Furthermore, the KEGG pathways analysis for ST3GAL5 and its co-expressed genes demonstrated their association with ‘transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathway’, ‘carbon metabolism’, ‘alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism’, ‘peroxisome’, ‘glycosphingolipid biosynthesis-ganglio series’, ‘fatty acid biosynthesis’, ‘2-oxocarboxylic acid metabolism’ and ‘signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells’ (Fig. 6C and D).

Next, Reactome pathway analysis of ST3GAL5 and its co-expressed genes identified highlighted their association with ‘protein localization’, ‘neutrophil degranulation’, ‘peroxisomal protein import’, ‘fatty acid metabolism’, ‘metabolism of vitamins and cofactors’, ‘interaction with cumulus cells and the zona pellucida’, ‘phenylalanine and tyrosine metabolism’ and ‘interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 signaling’ (Fig. 6E and F). All these pathways may therefore be associated with BLCA tumor progression and tumorigenesis.

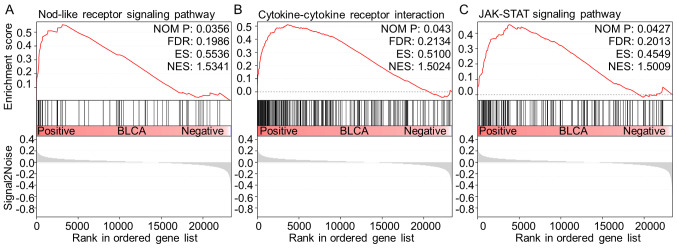

GSEA analysis between high and low ST3GAL5 expression in BLCA

To further identify the signaling pathways that are differentially activated in BLCA, GSEA was performed to investigate the difference between high- (n=124) and low-ST3GAL5 (n=183) expression groups by using the GEO dataset GSE83586. Three tumor-associated pathways were identified as significantly associated with the downregulation of ST3GAL5 expression in BLCA tissues, including ‘NOD-like receptor (NLR) signaling pathway’, ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’ and ‘Janus kinase (JAK)-STAT signaling pathway’ (Table III; Fig. 7).

Table III.

Gene set enrichment analysis in the group with low expression levels of ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5 in bladder urothelial carcinoma.

| Gene set name | NES | NOM P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG_SYSTEMIC_LUPUS_ERYTHEMATOSUS | 1.788003 | 0.00396 | 0.212486 |

| KEGG_AUTOIMMUNE_THYROID_DISEASE | 1.596979 | 0.027237 | 0.242572 |

| KEGG_FC_GAMMA_R_MEDIATED_PHAGOCYTOSIS | 1.593668 | 0.028689 | 0.212411 |

| KEGG_ALLOGRAFT_REJECTION | 1.579419 | 0.044747 | 0.208527 |

| KEGG_GLYCOSAMINOGLYCAN_BIOSYNTHESIS_CHONDROITIN_SULFATE | 1.577063 | 0.026923 | 0.189083 |

| KEGG_NOD_LIKE_RECEPTOR_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 1.534106 | 0.035644 | 0.198596 |

| KEGG_CYTOKINE_CYTOKINE_RECEPTOR_INTERACTION | 1.502448 | 0.042969 | 0.213385 |

| KEGG_JAK_STAT_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 1.500872 | 0.042718 | 0.201288 |

Gene sets with |NES|>1, NOM P<0.05 and FDR<0.25 were considered as significant. NES, normalized enrichment score; NOM, nominal; FDR, false discovery rate; JAK, Janus kinase; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Figure 7.

GSEA analysis between high and low expression of ST3GAL5 in BLCA. In total, three tumor-related signaling pathways were identified as positively associated with ST3GAL5 downregulation in BLCA. (A) NOD-like receptor signaling pathway. (B) Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction. (C) JAK-STAT signaling pathway. JAK, Janus kinase; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; ST3GAL5, ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5; ES, enrichment score; NES, normalized enrichment score; NOM, nominal; FDR, false discovery rate.

Discussion

BC is the most common malignancy of the urinary system, and ~90% of BC cases are urothelial carcinoma (5). Furthermore, BC can be low grade or high grade and can also be divided into MIBC and NMIBC; low grade BC rarely invades the muscular wall of the bladder and patients rarely succumb to low grade BC, while high grade BC is more likely to result in mortality (6). Furthermore, patients with NMIBC exhibit a favorable outcome (5-year overall survival of 95 vs. 69% in MIBC) (36). However, 70% of patients with BC will experience recurrence following initial treatment (surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy), including 30% out of the 70% of patients presenting with muscle invasive disease (37). In addition, cancer recurrence and progression lead to a higher disease stage, ending therefore in a less favorable outcome (38). Currently, the etiology of muscle invasion and high-grade progression in BC remains unknown. It is therefore crucial to identify an effective biomarker that could predict muscle invasion, high grade and prognosis in patients with BC.

To the best of our knowledge, ST3GAL5 expression and its effect on muscle invasion, cancer grade and prognosis in patients with BLCA have not yet been investigated. The present study investigated therefore the potential role of ST3GAL5 in BLCA. In this study, bioinformatics analysis of multiple independent public databases was performed. The results demonstrated that ST3GAL5 was downregulated in various types of cancer, including BC, and that its expression in BLCA tissues was lower compared with healthy bladder tissues. In addition, ST3GAL5 downregulation was positively associated with muscle invasion, high grade and a poor prognosis in patients with BLCA. Collectively, these findings indicated that ST3GAL5 may be considered as a tumor suppressor gene in BLCA, and may therefore inhibit the progression of BC to MIBC and high grade BLCA. These results also highlighted the potential role of ST3GAL5 as a therapeutic target in BC. However, further investigation is required to determine the underlying mechanisms of ST3GAL5 in BC progression and in the prognosis of patients with BC.

The association between ST3GAL5 expression, promoter methylation level and the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with BLCA was examined using TCGA data from the Xena browser. The results demonstrated that ST3GAL5 expression was downregulated in high stages and moderate nodal metastasis status compared with healthy bladder tissues. However, the level of ST3GAL5 promoter methylation was significantly decreased in BCLA tissues compared with healthy bladder tissues regardless of the patients' clinicopathological characteristics, including cancer stage, ethnicity, sex, age, weight, smoking status, nodal metastasis status and histological subtype. Furthermore, analysis of ST3GAL5 expression and DNA methylation status indicated that ST3GAL5 gene expression may be associated with certain CpG island sites. CpG islands are CG-rich stretches in the genome concentrated near transcription start sites; in normal cells they are protected and therefore are in a non-methylated state, but in tumors they are specifically methylated. These findings suggested therefore that ST3GAL5 promoter methylation may be associated with the clinicopathological characteristics of patients with BC.

ST3GAL5 is a protein that catalyzes the formation of ganglioside GM3 (7). ST3GAL5 is upregulated in several types of cancer, such as lung and brain cancer, and melanoma, and can serve as a tumor-associated carbohydrate antigen in immunotherapy for cancer (9,10). Furthermore, ST3GAL5, which encodes GM3, inhibits tumor cell proliferation through angiogenesis inhibition or decrease in cell motility (9). Previous studies reported that ST3GAL5 exerts some anti-proliferative effects in colon cancer (39), breast cancer (40,41), liver cancer (42) and other types of tumor (9,10). Although some studies demonstrated that ST3GAL5 has anti-tumor effects in human bladder cancer (11,14,39,43), the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. Furthermore, it was reported that ST3GAL5 effects could be associated with tumor cell apoptosis and angiogenesis inhibition (9,12,44). However, the expression profile and functional role of ST3GAL5 in BLCA remain unknown.

In the present study, the biological effect of ST3GAL5 in BLCA was investigated by using bioinformatics analysis of multiple public databases. Co-expressed genes that were positively associated with ST3GAL5 expression were identified in three public databases, and intersecting genes from all databases were considered to be significantly co-expressed genes. R packages were then used to identify the signaling pathways associated with the genes that were positively co-expressed with ST3GAL5 in BLCA samples. Furthermore, from the perspective of functional classification, GO enrichment analysis of BP, CC and MF was performed on ST3GAL5 and its co-expressed genes. The results from KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the ‘TGF-β signaling pathway’ was significantly associated with ST3GAL5 expression. The deregulation of this pathway has been reported to result in tumor progression (45). In healthy and early-stage cancer, such as breast and prostate cancer cells, the TGF-β pathway exerts tumor-suppressive properties; however, its activation in late-stage cancer can promote tumor progression, via metastasis and chemoresistance (45,46). Furthermore, the dual function and pleiotropic nature of TGF-β signaling makes of it a challenging target; therefore, careful therapeutic dosage of TGF-β drugs and careful patient selection are required (46). In the present study, although ST3GAL5 expression was downregulated in BLCA tissues compared with healthy bladder tissues, ST3GAL5 expression was significantly downregulated in high grade and advanced stage BLCA in multiple databases. The significant downregulation in high grade and advanced stage BLCA may due to the associated activation of ST3GAL5 and its co-expressed genes following the increase in TGF-β signaling transduction. Another pathway associated with ST3GAL5 expression was ‘carbon metabolism’. Cells require one-carbon units for nucleotide synthesis, methylation and reductive metabolism, which support the high proliferative rate of cancer cells (47). A previous study reported that polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism and susceptibility to BC suggested that variation in glutathione synthesis may contribute to the risk of BC (48). In the present study, Reactome pathway analysis demonstrated that the main pathway associated with ST3GAL5 expression was ‘protein localization’, and previous studies reported that changes in subcellular localization of tumor-associated proteins can influence protein structure and biological function, which are associated with tumorigenesis, tumor progression and patient prognosis (49–52). Another pathway associated with ST3GAL5 expression was ‘neutrophil degranulation’. Neutrophils have been shown to be the first responders to inflammation and infection (53). The role of neutrophils in cancer is multifactorial, but is not fully understood. Furthermore, neutrophils reflect a state of host inflammation, which is a hallmark of cancer (54), and can participate in different stages of the oncogenic process including tumor initiation, growth, proliferation and metastasis (55,56). Neutrophil granule proteins released upon cell activation have also been associated with tumor progression, and this differential granule mobilization may allow neutrophils and possibly associated cancer cells to exit the bloodstream and enter inflamed and infected tissues (53). Since neutrophils are immune cells, tumor immunity must also be considered in order to predict the prognosis of patients with BC. Takeuchi et al (55), reported that the Tumour-associated macrophage polarized M2 phenotype influences microangiogenesis, pathological outcome, tumor grade and tumor invasiveness in BC. In the present study, GO analysis of the BP and MF domains identified co-enzyme involvement in BP and MF, suggesting that co-enzymes may serve an important role in the tumorigenesis and tumor progression of BC. However, further in vitro and in vivo studies are required to elucidate the biological role of ST3GAL5 in BC. Taken together, these findings highlighted the important role of ST3GAL5 and its co-expressed genes in various carcinogenic processes.

A large BLCA dataset from the GEO database was investigated in the present study. According to the mean value of ST3GAL5 expression, the dataset was divided into low- and high-expression groups, and GSEA was used to compare the two groups. The results identified three tumor-associated pathways that were associated with ST3GAL5 in BLCA, the ‘NLR signaling pathway’, ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’ and ‘JAK-STAT signaling pathway’. NLR signaling pathway is an immunology-signaling pathway, in which cytosolic NLRs are associated with certain diseases, including infections, cancer and autoimmune and inflammatory disorders (57). Furthermore, NLRs and their downstream signaling components can engage in an intricate crosstalk with cell death and autophagy pathways, which are critical processes for cancer progression (58). Kent and Blander (57) reported that chronic inflammation resulting from the activated NLRs signaling pathway is a powerful driver of carcinogenesis, which promotes gene mutation, tumor growth and progression. In the present study, results from KEGG analysis suggested that lower expression of ST3GAL5 were enriched in the ‘NLR signaling pathway’. Ozaki and Leonard (59) demonstrated that cytokines are crucial intercellular regulators and mobilizers of cells that are involved in innate and adaptive inflammatory host defenses, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, cell death, angiogenesis, and development and repair processes associated with the restoration of homeostasis. In the current study, the ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’ was positively associated with lower ST3GAL5 expression, suggesting that ST3GAL5 downregulation may promote oncogenesis by affecting the immune status of patients with BC. The JAK-STAT pathway is an essential signaling pathway involved with numerous cytokines and proliferation factors in mammals (60). Previous studies (60,61) assessing the JAK-STAT signaling pathway reported highly conserved programs linking cytokine signaling to the regulation of essential cellular mechanisms, including cell proliferation, cell invasion, cell survival, inflammation and immunity. Furthermore, aberrant active regulation of JAK-STAT signaling pathway has been reported to contribute to cancer progression and development of metastasis (60,61). In the present study, results from pathway analysis suggested that the low expression of ST3GAL5 may positively affect the progression of BLCA via tumor immunity, cytokine interaction and cytokine transduction. The results from this study suggested that immunotherapy may be used in the treatment of BLCA, and that ST3GAL5 may be considered as a novel target and potential biomarker in BLCA.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BC

bladder cancer

- BLCA

bladder urothelial carcinoma

- MIBC

muscle invasive bladder cancer

- NMIBC

non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

Funding

The present study was supported by the Key Scientific and Technological Projects of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (grant no. 2018AB023).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are available in the GEO (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), Oncomine (www.oncomine.org) and TGCA (cancergenome.nih.gov) repositories.

Authors' contributions

JL and QW participated in the design of the present study, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. SO, ZN and GD performed the study and collected background information and data. SO was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Dyba T, Randi G, Bettio M, Gavin A, Visser O, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:356–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, corp-author. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Lond Engl. 2016;388:1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burger M, Catto JW, Dalbagni G, Grossman HB, Herr H, Karakiewicz P, Kassouf W, Kiemeney LA, Vecchia CL, Shariat S, Lotan Y. Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2012;63:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyazaki J, Nishiyama H. Epidemiology of urothelial carcinoma. Int J Urol. 2017;24:730–734. doi: 10.1111/iju.13376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witjes JA, Lebret T, Compérat EM, Cowan NC, De Santis M, Bruins HM, Hernández V, Espinós EL, Dunn J, Rouanne M, et al. Updated 2016 EAU Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71:462–475. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berselli P, Zava S, Sottocornola E, Milani S, Berra B, Colombo I. Human GM3 synthase: A new mRNA variant encodes an NH2-terminal extended form of the protein. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 2006;1759:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inokuchi JI, Inamori KI, Kabayama K, Nagafuku M, Uemura S, Go S, Suzuki A, Ohno I, Kanoh H, Shishido F. Biology of GM3 Ganglioside. Prog Mol Biol Transl. 2018;156:151–195. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng C, Terreni M, Sollogoub M, Zhang Y. Ganglioside GM3 and its role in cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:2933–2947. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180129100619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakomori SI, Handa K. GM3 and cancer. Glycoconjugate J. 2015;32:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10719-014-9572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satoh M, Ito A, Nojiri H, Handa K, Numahata K, Ohyama C, Saito S, Hoshi S, Hakomori SI. Enhanced GM3 expression, associated with decreased invasiveness, is induced by brefeldin A in bladder cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2001;19:723–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawashima N, Nishimiya Y, Takahata S, Nakayama KI. Induction of Glycosphingolipid GM3 expression by valproic acid suppresses cancer cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:21424–21433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.751503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohyama C. Glycosylation in bladder cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:308–313. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0809-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodes DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Mahavisno V, Varambally R, Yu J, Briggs BB, Barrette TR, Anstet MJ, Kincead-Beal C, Kulkarni P, et al. Oncomine 3.0: Genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia. 2007;9:166–180. doi: 10.1593/neo.07112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, Ghosh D, Barrette T, Pander A, Chinnaiyan AM. ONCOMINE: A cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6:1–6. doi: 10.1016/S1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li B, Severson E, Pignon JC, Zhao H, Li T, Novak J, Jiang P, Shen H, Aster JC, Rodig S, et al. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: Implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol. 2016;17:174. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu JS, Li B, Liu XS. TIMER: A web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e108–e110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SJ, Yoon BH, Kim SK, Kim SY. GENT2: An updated gene expression database for normal and tumor tissues. BMC Med Genomics. 2019;12(Suppl 5):101. doi: 10.1186/s12920-019-0514-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin G, Kang TW, Yang S, Baek SJ, Jeong YS, Kim SY. GENT: Gene expression database of normal and tumor tissues. Cancer Informatics. 2011;10:149–157. doi: 10.4137/CIN.S7226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldman M, Craft B, Hastie M, Repečka K, McDade F, Kamath A, Banerjee A, Luo Y, Rogers D, et al. The UCSC Xena platform for public and private cancer genomics data visualization and interpretation. 2019 Biorxiv 326470. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C, Zhang Z. GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W98–W102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anaya J, Reon B, Chen WM, Bekiranov S, Dutta A. A pan-cancer analysis of prognostic genes. Peer J. 2016;3:e1499. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim WJ, Kim EJ, Kim SK, Kim YJ, Ha YS, Jeong P, Kim MJ, Yun SJ, Lee KM, Moon SK, et al. Predictive value of progression-related gene classifier in primary non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riester M, Taylor JM, Feifer A, Koppie T, Rosenberg JE, Downey RJ, Bochner BH, Michor F. Combination of a novel gene expression signature with a clinical nomogram improves the prediction of survival in high-risk bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1323–1333. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riester M, Werner L, Bellmunt J, Selvarajah S, Guancial EA, Weir BA, Stack EC, Park RS, O'Brien R, Schutz FA, et al. Integrative analysis of 1q23.3 copy-number gain in metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1873–1883. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JS, Leem SH, Lee SY, Kim SC, Park ES, Kim SB, Kim SK, Kim YJ, Kim WJ, Chu IS. Expression signature of E2F1 and its associated genes predict superficial to invasive progression of bladder tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2660–2667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blaveri E, Simko JP, Korkola JE, Brewer JL, Baehner F, Mehta K, Devries S, Koppie T, Pejavar S, Pejavar S, et al. Bladder cancer outcome and subtype classification by gene expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4044–4055. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez-Carbayo M, Socci ND, Lozano J, Saint F, Cordon-Cardo C. Defining molecular profiles of poor outcome in patients with invasive bladder cancer using oligonucleotide microarrays. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:778–789. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stransky N, Vallot C, Reyal F, Bernard-Pierrot I, de Medina SG, Segraves R, de Rycke Y, Elvin P, Cassidy A, Spraggon C, et al. Regional copy number-independent deregulation of transcription in cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1386–1396. doi: 10.1038/ng1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16:284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu G, He QY. ReactomePA: An R/Bioconductor package for reactome pathway analysis and visualization. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12:477–479. doi: 10.1039/C5MB00663E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sjödahl G, Eriksson P, Liedberg F, Höglund M. Molecular classification of urothelial carcinoma: Global mRNA classification versus tumour-cell phenotype classification. J Pathology. 2017;242:113–125. doi: 10.1002/path.4886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc National Acad Sci. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villanueva RAM, Chen ZJ. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Meas Interdiscip Res Perspectives. (2nd) 2019;17:160–167. doi: 10.1080/15366367.2019.1565254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nykopp TK, Batista da Costa J, Mannas M, Black PC. Current clinical trials in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Curr Urol Rep. 2018;19:101. doi: 10.1007/s11934-018-0852-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaufman DS, Shipley WU, Feldman AS. Bladder cancer. Lancet. 2009;374:239–249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heijden AGvd, Witjes JA. Recurrence, progression, and follow-up in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol Suppl. 2009;8:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.eursup.2009.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, Isaji T, Satoh M, Li D, Arai Y, Gu J. Antitumor effects of exogenous ganglioside GM3 on bladder cancer in an orthotopic cancer model. Urology. 2012;81:210.e211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Q, Sun M, Yu M, Fu Q, Jiang H, Yu G, Li G. Gangliosides profiling in serum of breast cancer patient: GM3 as a potential diagnostic biomarker. Glycoconjugate J. 2019;36:419–428. doi: 10.1007/s10719-019-09885-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guthmann MD, Castro MA, Cinat G, Venier C, Koliren L, Bitton RJ, Vázquez AM, Fainboim L. Cellular and humoral immune response to N-Glycolyl-GM3 elicited by prolonged immunotherapy with an anti-idiotypic vaccine in High-Risk and metastatic breast cancer patients. J Immunother. 2006;29:215–223. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000188502.11348.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cai H, Zhou H, Miao Y, Li N, Zhao L, Jia L. MiRNA expression profiles reveal the involvement of miR-26a, miR-548l and miR-34a in hepatocellular carcinoma progression through regulation of ST3GAL5. Lab Invest. 2017;97:530–542. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2017.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawamura S, Ohyama C, Watanabe R, Satoh M, Saito S, Hoshi S, Gasa S, Orikasa S. Glycolipid composition in bladder tumor: A crucial role of GM3 ganglioside in tumor invasion. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:343–347. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung TW, Choi HJ, Kim SJ, Kwak CH, Song KH, Jin UH, Chang YC, Chang HW, Lee YC, Ha KT, Kim CH. The ganglioside GM3 is associated with cisplatin-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Massagué J. TGFβ in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colak S, Ten Dijke P. Targeting TGF-β signaling in cancer. Trends Cancer. 2017;3:56–71. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newman AC, Maddocks ODK. One-carbon metabolism in cancer. Brit J Cancer. 2017;116:1499–1504. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore LE, Malats N, Rothman N, Real FX, Kogevinas M, Karami S, García-Closas R, Silverman D, Chanock S, Welch R, et al. Polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism and trans-sulfuration pathway genes and susceptibility to bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2452–2458. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X, Che K, Wang L, Zhang T, Wang G, Pang Z, Shen H, Du J. Subcellular localization of β-arrestin1 and its prognostic value in lung adenocarcinoma. Medicine. 2017;96:e8450. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J, Wang H, Huang C, Qian H. Subcellular localization of MTA proteins in normal and cancer cells. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014;33:843–856. doi: 10.1007/s10555-014-9511-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim HJ, Lee SY, Kim CY, Kim YH, Ju W, Kim SC. Subcellular localization of FOXO3a as a potential biomarker of response to combined treatment with inhibitors of PI3K and autophagy in PIK3CA-mutant cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:6608–6622. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boudhraa Z, Bouchon B, Viallard C, D'Incan M, Degoul F. Annexin A1 localization and its relevance to cancer. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016;130:205–220. doi: 10.1042/CS20150415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mollinedo F. Neutrophil degranulation, plasticity, and cancer metastasis. Trends Immunol. 2019;40:228–242. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanahan D, Weinberg Robert A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takeuchi H, Tanaka M, Tanaka A, Tsunemi A, Yamamoto H. Predominance of M2-polarized macrophages in bladder cancer affects angiogenesis, tumor grade and invasiveness. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3403–3408. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coffelt SB, Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Neutrophils in cancer: Neutral no more. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:431–446. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kent A, Blander JM. Nod-like receptors: Key molecular switches in the conundrum of cancer. Front Immunol. 2014;5:185. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saxena M, Yeretssian G. NOD-like receptors: Master regulators of inflammation and cancer. Front Immunol. 2014;5:327. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ozaki K, Leonard WJ. Cytokine and cytokine receptor pleiotropy and redundancy. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29355–29358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pencik J, Pham HTT, Schmoellerl J, Javaheri T, Schlederer M, Culig Z, Merkel O, Moriggl R, Grebien F, Kenner L. JAK-STAT signaling in cancer: From cytokines to non-coding genome. Cytokine. 2016;87:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trivedi S, Starz-Gaiano M. Drosophila Jak/STAT signaling: Regulation and relevance in human cancer and metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:4056. doi: 10.3390/ijms19124056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are available in the GEO (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), Oncomine (www.oncomine.org) and TGCA (cancergenome.nih.gov) repositories.