Abstract

Objectives:

Severe acute kidney injury (AKI) is a known risk factor for infection and mortality. However, whether stage 1 AKI is a risk factor for infection has not been evaluated in adults. We hypothesized that stage 1 AKI following cardiac surgery would independently associate with infection and mortality.

Methods:

In this retrospective propensity-score matched study, we evaluated 1,620 adult patients who underwent non-emergent cardiac surgery at the University of Colorado Hospital from 2011 to 2017. Patients who developed stage 1 AKI by Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes creatinine criteria within 72 hours of surgery were matched to patients who did not develop AKI. The primary outcome was an infection, defined as a new surgical site infection, positive blood or urine culture, or development of pneumonia. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital mortality, stroke, and intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital length of stay (LOS).

Results:

Stage 1 AKI occurred in 293 patients (18.3%). Infection occurred in 20.9% of patients with stage 1 AKI compared to 8.1% in the non-AKI group (p<0.001). In propensity-score matched analysis, stage 1 AKI independently associated with increased infection (OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.37-3.17), ICU LOS (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.71–3.31), and hospital LOS (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.17-1.45).

Conclusions:

Stage 1 AKI is independently associated with post-operative infection, ICU LOS, and hospital LOS. Treatment strategies focused on prevention, early recognition, and optimal medical management of AKI may decrease significant postoperative morbidity.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common postoperative complication that has been shown to significantly increase rates of morbidity and mortality (1–3). AKI has been defined since 2012 by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria and is divided into three stages based on increases in serum creatinine or decreases in urine output (4). Stage 1 AKI is defined by an absolute increase in serum creatinine of 0.3 mg/dL from baseline. Stage 2 is defined as a doubling of creatinine from baseline, and stage 3 is defined as a tripling in creatinine, new initiation of dialysis, or an absolute creatinine value ≥4.0 mg/dL.

Postoperative AKI is a strong predictor of mortality, and severe AKI independently increases mortality by 3-8 fold (5). Even small increases in creatinine of 0.5 mg/dL following cardiac surgery have been shown to have strong deleterious effects (6, 7). However, there are few studies specifically evaluating mortality outcomes using the KDIGO stage 1 definition, and results have been mixed (8, 9).

Sepsis is the leading cause of death in patients with AKI (10). While sepsis as a cause of AKI has been well documented (11), AKI is also increasingly recognized as a risk factor for subsequent sepsis (12, 13). Post-operative infections, including mediastinitis, sepsis, and pneumonia, are serious complications of cardiothoracic surgery. These complications have been shown to increase mortality rates by over five-fold (14). Numerous risk factors for postoperative infection have been identified, including age, female gender, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, chronic lung disease, peripheral vascular disease, immunosuppressive treatment, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, ejection fraction, intraoperative blood products, and, importantly, severe AKI (15–17).

Severe postoperative AKI following cardiac surgery has been shown in several studies to independently increase the risk of subsequent infection (18–20). Zanardo et al. evaluated 737 patients with baseline creatinine values < 1.5 mg/dL and found that the development of AKI, defined as a post-operative peak creatinine of ≥ 2.5 mg/dL, increased the rates of post-operative infection from 0.8% to 25.9% (20). Thakar et al. later found that in post-surgical patients, the development of AKI, defined as a 50% decline in creatinine clearance, increased rates of infection to 23.7%, and 58.5% in cases where dialysis was required (19). Prior studies have only assessed the impact of KDIGO stage 2 and stage 3 AKI on subsequent infectious complications. The impact of stage 1 AKI on subsequent rates of infection following cardiac surgery is, therefore unknown.

In this retrospective study, we evaluate the impact of post-operative stage 1 AKI on rates of infection following cardiac surgery. We hypothesized that stage 1 AKI would be independently associated with increased rates of postoperative infection and mortality. 59

Methods

Study Population:

We conducted a retrospective chart review from January 2011 to July 2017 utilizing the University of Colorado Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Colorado. Subjects were included if they were ≥18 years of age, underwent elective or urgent cardiac surgery at the University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), and had at least one pre-operative creatinine value available. Subjects were excluded for the following reasons: 1) intraoperative death, 2) serum creatinine measures not available for the first 3 postoperative days, 3) received antibiotics within 2 weeks prior to surgery, 4) developed an infection within 48 hours of surgery, 5) AKI at the time of surgery 6) end-stage renal disease, 7) cardiogenic shock at the time of surgery, 8) transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) or thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair (TEVAR) procedures, 9) procedures performed for infectious endocarditis or aortic dissection, and 10) solid-organ transplant recipients.

Definitions of Predictor Variable:

Postoperative AKI was defined using KDIGO guidelines (4) as an increase in creatinine of at least 0.3 mg/dL. Stage 1 AKI was defined as an increase in creatinine of at least 0.3 mg/dL without more than a doubling from baseline. AKI had to occur within 72 hours of surgery to determine that the AKI was temporally related to surgery, and preceded infection.

Outcomes:

The primary outcome was infection, which was defined as having one of the following: 1) documented surgical site infection which included deep sternal wound infection, superficial wound infection, and cellulitis of incision or vein harvest sites; 2) positive blood culture or urine culture with >100,00 CFUs; 3) imaging suggestive of new-onset pneumonia based on radiology reports. Secondary outcomes were in-hospital mortality, prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital length of stay (LOS), and postoperative stroke.

Matching Variables:

We adjusted our analyses for variables that have been shown to be associated with infection, including age, gender, BMI, hematocrit, smoking status, use of immunosuppressive medication preoperatively, comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic lung disease, previous cardiovascular interventions, as well as perfusion time, and intraoperative blood product transfusions. We also matched patients based on surgical type, such as aneurysm repair, valvular surgery, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), ventricular assist device (VAD) placement, , and combination, which included combined operations (CABG with valve replacement, for instance). Due to the lower number of patients, when matching patients with stage 2-3 AKI gender, age, perfusion time, surgical time, and intraoperative blood product were used.

Statistical Analysis:

For each of the outcomes we adjusted for covariates using propensity-score matching (21). A propensity score for each patient was calculated using a multivariable logistic regression model in which the dependent variable was the presence of stage 1 AKI or stage 2 and 3 AKI and the independent variables were the preoperative and operative adjustment variables. For the propensity model, the β-coefficients were combined with the patient’s values for each covariate to generate individual propensity scores. In the stage 1 AKI match, patients were first stratified by surgical type, and then these patient-level propensity scores were then used to match patients with AKI stage 1 to similar patients without AKI using the 1-to-1 greedy matching method. When matching patients with AKI stage 2-3, stratification based on the surgical type was not possible, and so surgical type was included as part of the propensity score generation. A 2-to-1 greedy matching method was used for stage 2-3 AKI (22). Generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were used to test the propensity-matched cohort to account for correlation within each matched pair. For all outcomes and risk-adjusted results, statistical significance and confidence intervals were adjusted for multiple comparisons (i.e., four outcomes and two risk-adjustment methods) using the Bonferroni method by multiplying the p values or dividing the alpha levels by the number of comparisons. All statistical tests were considered to be significant at a 2-sided p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics and unadjusted comparison of the study population.

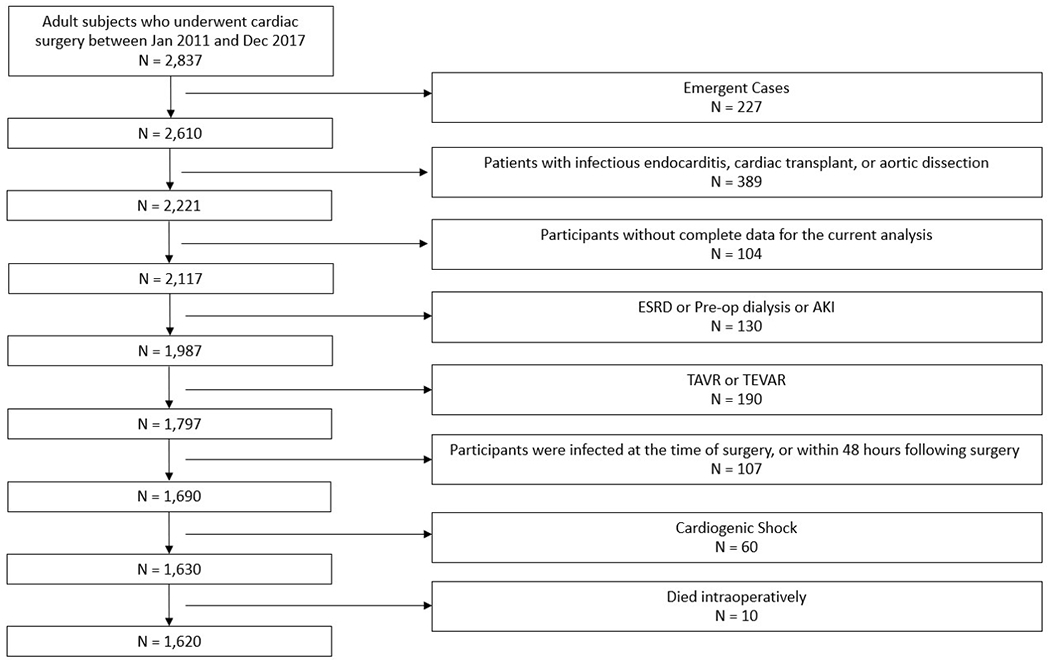

A total of 2,837 patients underwent cardiac surgery at the University of Colorado during the study period, of which 1,620 met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Before matching, significant differences existed in the baseline characteristics of patients with no AKI , stage 1 AKI, and stage 2-3 AKI (Table 1). A total of 297 patients (18.3%) developed stage 1 AKI, and 52 patients (3.2%) developed stage 2-3 AKI. Unadjusted comparisons demonstrated that patients who developed AKI were less often females, had higher body mass index, lower preoperative hematocrit, and higher numbers of comorbidities than those who did not develop AKI. Particularly, patients in both stage I and stage 2-3 AKI had a higher incidence of hypertension, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and LV dysfunction (EF<50%). Also, their surgeries were prolonged with longer cardiopulmonary bypass times, and they had higher rates of intraoperative blood product administration. Patients with AKI were also more likely to undergo combined surgical procedures. Finally, baseline eGFR was slightly lower in the Stage 1 AKI group than the no AKI group, although this difference was not observed in patients who developed stage 2-3 AKI (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study Cohort selection. The flow diagram depicting the details of patients screened, and reasons for patient exclusion.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of 1620 patients undergoing cardiac surgery by the occurrence of acute kidney injury.

| No AKI | Stage 1 AKI | Stage 2 & 3 AKI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=1,271) | (n=297) | (n=52) | |||

| Characteristics | N (%)* | N (%)* | P value† | N (%)* | P value† |

| Female | 394 (31.0) | 65 (21.9) | .002 | 19 (36.5) | .40 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 60.6 (13.8) | 62.6 (13.5) | .02 | 61.9 (14.8) | .53 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 950 (74.7) | 212 (71.4 | .39 | 39 (75.0) | .99 |

| Hispanic | 186 (14.6) | 43 (14.5) | 8 (15.4) | ||

| Black | 79 (6.2) | 25 (8.4) | 3 (5.8) | ||

| Other/unknown | 56 (4.4) | 17 (5.7) | 2 (3.9) | ||

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 28.2 (6.1) | 29.3 (6.5) | .01 | 29.3 (6.8) | .28 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Sleep apnea | 250 (19.7) | 64 (21.6) | .47 | 9 (17.3) | .67 |

| Hypertension | 862 (67.8) | 237 (79.8) | <.001 | 41 (78.9) | .09 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 359 (28.3) | 126 (42.4) | <.001 | 18 (34.6) | .32 |

| Chronic lung disease | 244 (19.2) | 72 (24.2) | .05 | 12 (23.1) | .49 |

| Liver disease | 33 (2.6) | 13 (4.4) | .10 | 1 (1.9) | .99 |

| Congestive heart failure | 474 (37.3) | 138 (46.5) | .004 | 24 (46.2) | .20 |

| Cancer with 5 years | 117 (9.2) | 17 (5.7) | .05 | 8 (15.4) | .14 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 62 (4.9) | 30 (10.1) | <.001 | 4 (7.7) | .36 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 137 (10.8) | 43 (14.5) | .07 | 6 (11.5) | .86 |

| Dyslipidemia | 726 (57.1) | 188 (63.3) | .05 | 31 (59.6) | .72 |

| Baseline platelets, mean (SD) | 220.1 (63.4) | 213.2 (68.1) | .14 | 212.5 (59.9) | .58 |

| Baseline eGFR, mean (SD) | 79.1 (18.1) | 72.0 (12.6) | <.001 | 77.4 (13.9) | .60 |

| Smoker at time of surgery | 284 (22.3) | 80 (26.9) | .09 | 11 (21.2) | .84 |

| History of IV drug abuse | 56 (4.4) | 12 (4.0) | .78 | 1 (1.9) | .72 |

| Last hematocrit, mean (SD) | 41.5 (5.5) | 39.8 (6.2) | <.001 | 39.8 (5.5) | .03 |

| Last white blood cell count, mean (SD) | 7.3 (2.4) | 7.7 (2.4) | .04 | 6.7 (2.1) | .08 |

| Ejection fraction, mean (SD) | 54.0 (14.6) | 51.6 (15.8) | .02 | 51.9 (13.6) | .29 |

| Perfusion time, mean (SD) | 130.9 (68.2) | 149.9 (79.8) | <.001 | 163.0 (87.9) | .01 |

| Surgical time, hours, mean (SD) | 6.3 (1.8) | 6.9 (2.1) | <.001 | 7.6 (2.7) | <.001 |

| Intraoperative blood products | 457 (6.0) | 143 (48.2) | <.001 | 31 (59.6) | <.001 |

| Red blood cell units, mean (SD) | 0.6 (2.4) | 1.1 (2.7) | .002 | 2.2 (4.1) | .01 |

| Platelet units, mean (SD) | 0.6 (1.0) | 0.8 (1.1) | .003 | 1.1 (1.4) | <.001 |

| Fresh frozen plasma, mean (SD) | 1.2 (3.3) | 1.8 (3.2) | .01 | 3.5 (6.1) | .01 |

| Cryoprecipitate units, mean (SD) | 0.05 (0.3) | 0.08 (0.4) | .30 | 0.08 (0.3) | .51 |

| Immunosuppressive medication prior to surgery | .56 | .39 | |||

| No | 1,006 (79.2) | 239 (80.5) | 40 (76.9) | ||

| Yes | 33 (2.6) | 10 (3.4) | 3 (5.8) | ||

| Unknown | 232 (18.3) | 48 (16.2) | 9 (17.3) | ||

| Steroid use | .94 | .11 | |||

| No | 1,127 (88.7) | 263 (88.6) | 42 (80.8) | ||

| Yes | 38 (3.0) | 8 (2.7) | 4 (7.7) | ||

| Unknown | 106 (8.3) | 26 (8.8) | 6 (11.5) | ||

| Previous cardiovascular intervention | 398 (31.3) | 102 (34.3) | .31 | 17 (32.7) | .83 |

| Surgical type | <.001 | .52 | |||

| Aortic Aneurysm repair | 149 (11.8) | 23 (7.7) | 8 (15.4) | ||

| Valve surgery | 390 (30.7) | 59 (19.9) | 11 (21.2) | ||

| Coronary artery bypass | 350 (27.5) | 112 (37.7) | 14 (26.9) | ||

| Left ventricular assist device | 21 (1.7) | 6 (2.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Combined | 175 (13.8) | 60 (20.2) | 10 (19.2) | ||

| Other | 186 (14.6) | 37 (12.5) | 9 (17.3) | ||

| Family history cardiovascular disease | 276 (21.7) | 60 (20.2) | .57 | 13 (25.0) | .57 |

| New York Heart Association class | .004 | .36 | |||

| None | 802 (63.1) | 162 (54.6) | 28 (53.9) | ||

| Class I | 28 (2.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Class II | 141 (11.1) | 37 (12.5) | 7 (13.5) | ||

| Class III | 216 (17.0) | 70 (23.6) | 11 (21.2) | ||

| Class IV | 84 (6.6) | 27 (9.1) | 6 (11.5) | ||

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; SD, standard deviation; eGRF, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IV, intravenous; IQR, interquartile range.

Values are frequency and column percent unless otherwise stated.

P values are from chi-square or Fischer’s exact and t-test and are bolded when less than .05.

“Other” surgical cases refer to any case that does not fit into another category (surgical repair of ventricular septal defect, e.g.)

Early post-surgical outcomes in unmatched cohort:

Bivariate comparison of the subgroups demonstrated that overall post-operative infections were significantly higher in patients with stage 1 AKI (20.9%) and patients with stage 2-3 AKI (34.6%) than patients without AKI (8.1%, p<0.001 each). Overall there were 24 deaths (1.5%) within 30 days of surgery. The mortality rates in stage 1 AKI and stage 2-3 AKI were 3.4% (P=0.002) and 7.7% (P=0.002), respectively, compared to 0.8% in the non-AKI group. Post-operative stroke was significantly higher in the stage 1 AKI group than the no AKI group (1.1 vs. 3.0%, p = .03). The rate of stroke in stage 2-3 AKI was slightly higher than the stage 1 AKI group (3.9%), although this did not achieve statistical significance compared to the no AKI group. ICU LOS and Hospital LOS were both significantly longer in the AKI groups than in the no AKI group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate comparison of unadjusted outcomes of 1620 patients by the occurrence of acute kidney injury.

| No AKI | Stage 1 AKI | Stage 2 & 3 AKI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=1,271) | (n=297)) | (n=52) | |||

| Outcomes | N (%)* | N (%)* | P value† | N (%)* | P value† |

| In-hospital mortality | 10 (0.8) | 10 (3.4) | .002 | 4 (7.7) | .002 |

| Infection | 103 (8.1) | 62 (20.9) | <.001 | 18 (34.6) | <.001 |

| Post-operative SSI (superficial) | 25 (2.0) | 12 (4.0) | .04 | 5 (9.6) | <.001 |

| Post-operative SSI (deep) | 13 (1.0) | 4 (1.3) | .6 | 2 (3.8) | .06 |

| Post-operative blood or urine culture (+) | 43 (3.4) | 31 (10.1) | <.001 | 10 (19.2) | <.001 |

| Pneumonia | 35 (2.8) | 24 (8.1) | <.001 | 7 (13.5) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 14 (1.1) | 9 (3.0) | .03 | 2 (3.9) | .13 |

| ICU length of stay greater than 72 hours | 440 (34.6) | 190 (64.0) | <.001 | 41 (78.9) | <.001 |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 8 (6-11) | 10 (7-16) | <.001 | 12 (8-19) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; SD, standard deviation; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

Values are frequency and column percent unless otherwise stated.

P values are from Fischer’s exact and Wilcoxon rank-sum and are bolded when less than .05.

Early post-surgical outcomes in propensity-score matched cohort:

The propensity-score matching models paired 277 patients with Stage 1 AKI to 277 non-AKI controls, and 49 stage 2-3 AKI patients to 92 non-AKI controls. Only 20 stage 1 AKI patients (6.7%) and 3 stage 2-3 AKI patients (5.8%) were unable to match successfully. Following the propensity-score matching, there was a significant reduction in variables with standard deviations > 0.1 (Supplementary Table 1).

Outcomes by AKI group after propensity-score matching are given in Table 3. The rate of infection was 9.8% compared to 19.5% in the stage 1 AKI match (p=.002) and 12.0% vs 32.7% (p=.01) in the stage 2-3 match. These differences were due primarily to increased rates of positive blood or urine cultures in those with AKI. The mortality rate in stage 1 AKI was more than double the rate in no AKI (1.4% vs. 2.9%) but did not reach statistical significance. The mortality rate in stage 2-3 AKI was 8.2%, with a strong trend towards significance (p=.05). ICU LOS and hospital LOS were both significantly longer in the AKI groups than in the no AKI groups, and differences in rates of stroke were non-significant in both groups.

Table 3.

Outcomes of patients by the occurrence of acute kidney injury for propensity-matched cohort.

| No AKI | Stage 1 AKI | No AKI | Stage 2 & 3 AKI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=277) | (n=277) | (n=92) | (n=49) | |||

| Outcomes | N (%)* | N (%)* | P value† | N (%)* | N (%)* | P value† |

| In-hospital mortality | 4 (1.4) | 8 (2.9) | .38 | 1 (1.1) | 4 (8.2) | .05 |

| Infection | 27 (9.8) | 54 (19.5) | .002 | 11 (12.0) | 16 (32.7) | .01 |

| Post-operative surgical site infection | 9 (3.3) | 14 (5.1) | .39 | 4 (4.4) | 7 (12.3) | .05 |

| Post-operative blood or urine culture (+) | 11 (4.0) | 26 (9.4) | .02 | 2 (2.2) | 9 (18.4) | .001 |

| Pneumonia | 13 (4.7) | 22 (7.9) | .16 | 5 (5.4) | 6 (12.2) | .19 |

| Stroke | 6 (2.2) | 8 (2.9) | .79 | 1 (1.1) | 2 (4.1) | .28 |

| ICU length of stay greater than 72 hours | 116 (41.9) | 175 (63.2) | <.001 | 32 (34.8) | 39 (79.6) | <.001 |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 8 (6-12) | 10 (7-16) | <.001 | 8 (6-11) | 12 (8-18) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; SD, standard deviation; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

Values are frequency and column percent unless otherwise stated.

P values are from Fischer’s exact and Wilcoxon rank-sum and are bolded when less than .05.

Early post-surgical outcomes based on the surgical type

Bivariate comparison of primary and secondary endpoints among the patients undergoing various types of surgeries are shown in Table 4. While caution should be exercised in the interpretation given the lower event rates in subgroup analysis, there was a significantly higher in-hospital mortality in aortic aneurysm repair patients who developed postoperative AKI compared to no AKI. Moreover, among CABG, valve surgery or other procedures groups, patients who sustained stage I AKI had significantly higher rates of post-operative infection.

Table 4.

Bivariate comparison of outcomes in 1620 cardiac surgery patients based on the type of surgery and occurrence of acute kidney injury.

| No AKI | Stage 1 AKI | Stage 2 & 3 AKI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=1,271 | (n=297) | (n=52) | |||

| Surgical type | N (%)* | N (%)* | P value† | N (%)* | P value† |

| Aortic Aneurysm repair | 149 (11.7) | 23 (7.7) | 8 (15.4) | ||

| In-hospital mortality | 1 (0.7) | 2 (8.7) | .05 | 1 (12.5) | NS |

| Infection | 11 (7.4) | 1 (4.4) | NS | 3 (37.5) | .02 |

| Stroke | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | NS | 1 (12.5) | NS |

| ICU length of stay greater than 72 hours | 34 (22.8) | 9 (33.1) | NS | 5 (62.5) | .02 |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 7 (5-9) | 8 (6-9) | NS | 9 (6-15) | NS |

| Valve surgery | 390 (30.7) | 59 (19.9) | 11 (21.2) | ||

| In-hospital mortality | 5 (1.3) | 2 (3.4) | NS | 1 (9.1) | NS |

| Infection | 24 (6.2) | 11 (18.6) | .003 | 3 (27.3) | .03 |

| Stroke | 7 (1.8) | 2 (3.4) | NS | 0 (0) | NS |

| ICU length of stay greater than 72 hours | 130 (33.3) | 34 (57.6) | <.001 | 9 (81.8) | .002 |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 7 (5-10) | 9 (7-14) | <.001 | 12 (8-24) | .003 |

| Coronary artery bypass | 350 (27.5) | 112 (37.7) | 14 (26.9) | ||

| In-hospital mortality | 1 (0.3) | 3 (2.7) | NS | 0 (0) | NS |

| Infection | 31 (8.9) | 25 (22.3) | <.001 | 5 (35.7) | .01 |

| Stroke | 4 (1.1) | 4 (3.6) | NS | 1 (7.1) | NS |

| ICU length of stay greater than 72 hours | 117 (33.4) | 69 (61.6) | <.001 | 11 (78.6) | <.001 |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 8 (6-11) | 11 (8-15) | <.001 | 14 (8-17) | <.001 |

| Left ventricular assist device | 21 (1.7) | 6 (2.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| In-hospital mortality | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | NS | 0 (0-0) | NS |

| Infection | 3 (14.3) | 1 (16.7) | NS | 0 (0-0) | NS |

| Stroke | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS | 0 (0-0) | NS |

| ICU length of stay greater than 72 hours | 11 (52.4) | 6 (100) | NS | 0 (0-0) | NS |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 24 (17-29) | 32 (22-42) | NS | 0 (0-0) | NS |

| Combination‡ | 175 (13.8) | 30 (20.2) | 10 (19.2) | ||

| In-hospital mortality | 2 (1.1) | 3 (5.0) | NS | 0 (0) | NS |

| Infection | 20 (11.4) | 13 (21.7) | NS | 2 (20.0) | NS |

| Stroke | 2 (1.1) | 3 (5.0) | NS | 0 (0) | NS |

| ICU length of stay greater than 72 hours | 78 (44.6) | 46 (76.7) | <.001 | 9 (90.0) | .01 |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 9 (6-12) | 12 (8-19) | <.001 | 12 (7-20) | NS |

| Other‡ | 186 (14.6) | 37 (12.5) | 9 (17.3) | ||

| In-hospital mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS | 2 (22.2) | .002 |

| Infection | 14 (7.5) | 11 (29.7) | <.001 | 5 (55.6) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS | 0 (0) | NS |

| ICU length of stay greater than 72 hours | 70 (37.6) | 26 (70.3) | <.001 | 7 (77.8) | .03 |

| Hospital length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 8 (6-11) | 12 (7-20) | <.001 | 15 (7-25) | NS |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; SD, standard deviation; eGRF, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IV, intravenous; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable. NS - not significant

Values are frequency and column percent unless otherwise stated.

P values are Fischer’s exact and Wilcoxon rank-sum and are bolded when less than .05.

Other are all surgeries that did not fall under the listed procedure, and the combination refers to surgeries that featured components of more than one category.

Stage 1 AKI is associated with infection and prolonged hospital and ICU LOS.

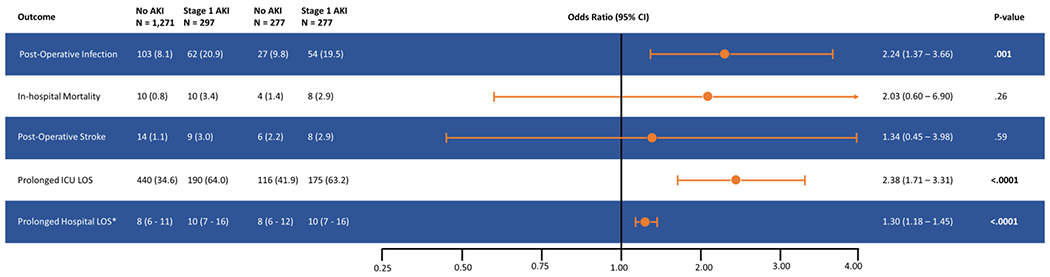

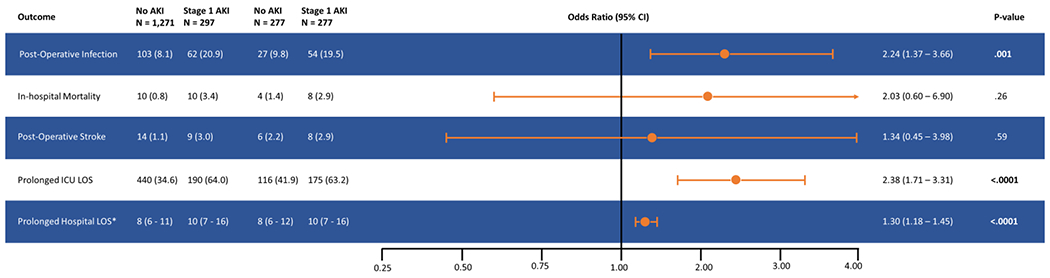

After adjusting for the differences in baseline comorbidities and surgical complexity using propensity-score matching, the patients with stage I AKI had significantly increased odds of infection when compared to matched controls. In the 277 matched pairs determined by the propensity-matched model, the odds ratio (OR) for infection was 2.24 (95% CI 1.37 – 3.66). Stage 1 AKI was associated with in-hospital mortality in the unadjusted analysis-, although not the propensity-score matched model. Prolonged ICU and hospitals LOS were more likely in the stage 1 AKI group both unadjusted and propensity-score matched models. Finally, while post-operative stroke was associated with stage 1 AKI in the unadjusted models, there were no differences between the groups after multivariable analysis and propensity matching (Table 5, Figure 2). The main findings of the study are summarized in graphical form in Figure 3.

Table 5.

Unadjusted and adjusted primary and secondary outcomes of the entire cohort by acute kidney injury.

| Stage 1 AKI | Stage 2 & 3 AKI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| In-hospital mortality | ||||

| Unadjusted* | 4.394 (1.812-10.656) | .001 | 10.508 (3.181-34.709) | <.001 |

| Propensity matched† | 2.030 (0.597-6.902) | .26 | 8.089 (0.865-75.664) | .07 |

| Infection | ||||

| Unadjusted* | 2.992 (2.120-4.224) | <.0001 | 6.003 (3.276-11.003) | <.001 |

| Propensity matched† | 2.242 (1.373-3.662) | .001 | 3.570 (1.449-8.799) | .01 |

| Stroke | ||||

| Unadjusted* | 2.806 (1.203-6.546) | .02 | 3.592 (0.795-16.231) | .10 |

| Propensity matched† | 1.343 (0.454-3.977) | .59 | 3.872 (0.336-44.602) | .28 |

| ICU length of stay greater than 72 hours | ||||

| Unadjusted* | 3.353 (2.576-4.365) | <.0001 | 7.036 (3.581-13.825) | <.001 |

| Propensity matched† | 2.381 (1.714-3.309) | <.0001 | 7.674 (3.521-16.728) | <.001 |

| Hospital length of stay‡ | ||||

| Unadjusted* | 1.449 (1.353-1.551) | <.0001 | 1.822 (1.578-2.103) | <.001 |

| Propensity matched† | 1.301 (1.167-1.451) | <.0001 | 1.858 (1.394-2.475) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit.

Sample size was 1,271 for no AKI and 297 for stage 1 AKI and 1,271 for no AKI and 52 for stage 2 & 3 AKI.

Sample size was 277 for no AKI and 277 for stage 1 AKI and 92 for no AKI and 49 for stage 2 & 3 AKI.

Length of stay was fitted to a negative binomial model.

Figure 2.

Forest Plot Stage showing odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for postoperative infection, in-hospital mortality, post-operative stroke, prolonged ICU LOS, and prolonged hospital LOS in patients with Stage 1 acute kidney injury (AKI) compared to patients who did not develop AKI. Also shown are rates of primary and secondary outcomes in unmatched and propensity-score matched patients.

Data are displayed as numbers and percentages, except where indicated.

* Mean and interquartile range

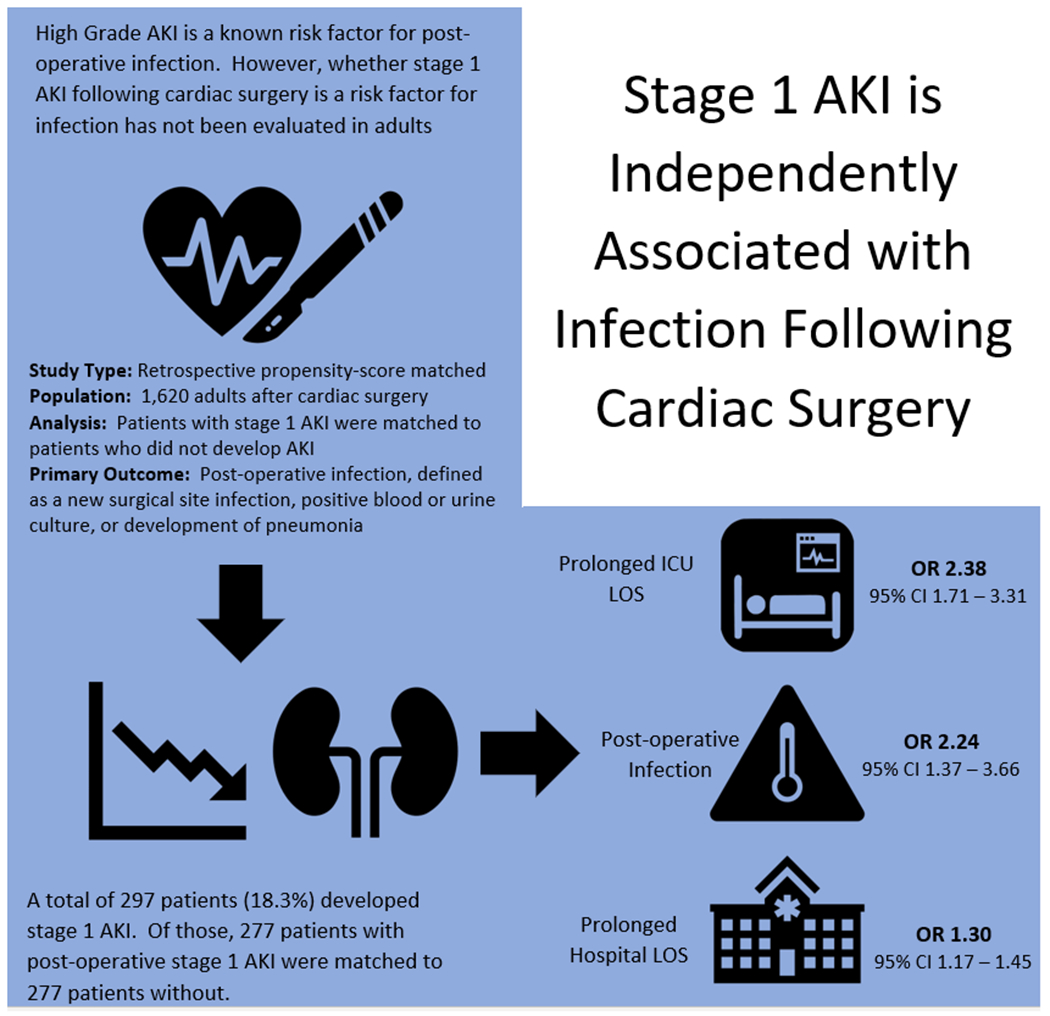

Figure 3.

Graphical summary of methods and results.

AKI, acute kidney injury; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Stage 2-3 AKI is associated with infection and prolonged hospital and ICU LOS.

In the patients with stage 2-3 AKI, there was a statistically significant increase in odds of infection in the propensity-score matched analyses (OR 3.57, 95% CI 1.45-8.80). The adjusted odds ratio for mortality was 8.09 but did not meet statistical significance. ICU and hospital LOS were significantly increased across all models, andpost-operative stroke was not associated with stage 2-3 AKI (Table 5).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study in adults to demonstrate an association between post-surgical KDIGO stage 1 AKI and subsequent infection in cardiac surgery patients. Stage 1 AKI was also associated with increased ICU and hospital length of stay, although not with post-operative stroke or in-hospital mortality after statistical adjustments.

The STS database defines post-operative AKI as either a 3-fold increase from baseline creatinine, a creatinine ≥ 4.0 mg/dL, or the initiation of dialysis. This definition corresponds to KDIGO stage III disease and captures only severe cases of AKI. Mortality rates are especially high in patients who meet these criteria for AKI (23). While several early studies have reported increased mortality with a creatinine rise of 0.5 mg/dl of greater (6, 7), there are few studies specifically evaluating the mortality impact of KDIGO stage 1 AKI (rise of 0.3 mg/dL or greater). A study by Machado et al. evaluated 2,804 cardiac surgery patients, and found stage 1 AKI rates of 35% (42% for all stages of AKI), with mortality rates of 8.2% within the stage 1 AKI group (8). The hazard ratio for mortality was 3.35 (2.19 – 5.12). A second study by Howitt et al. sought to validate the KDIGO criteria in a population of 2,267 cardiac surgery patients and reported AKI rates of 44%. The outcome of 2-year mortality was not significantly different between patients with stage 1 AKI and those without (9). In our study, while there was a large difference in unadjusted odds of mortality with Stage 1 AKI (OR = 4.4), statistical significance was lost following propensity-score matching. However, a similar pattern was seen in the stage 2-3 AKI group, which did not achieve significance after matching despite an OR of 8.1. Given the low event rate in our database, it is likely that our study was underpowered to show a difference in mortality.

Previous reports have demonstrated an association between severe post-surgical AKI and subsequent infection but did not evaluate stage 1 AKI. As early as 1989, Corwin et al. were able to demonstrate in a propensity-matched study a significant increase in postoperative infections in patients with severe AKI (24). Subsequently, Zanardo et al. reported outcomes in 775 post-surgical patients that moderate and severe AKI increased rates of infection to 6.1% and 25.9% respectively, compared to 0.8% in those who did not develop AKI (20). Similarly, Thakar et al. analyzed 24,660 patients and found that the development of AKI increased infection rates to 58.5% if dialysis was required, and to 23.7% in those not requiring dialysis (19). These studies clearly demonstrate that severe AKI is associated with increased postoperative infection in adults, but don’t indicate whether stage 1 AKI similarly worsens outcomes. SooHoo et al. evaluated the incidence of infectious complications following AKI development in neonates undergoing the Norwood procedure (18). In this study, AKI occurred in 40% of subjects, of which 68% were classified as stage 1 disease. Infectious complications occurred in 44% of subjects, and the odds of infectious complications were over 3-fold higher in patients with AKI compared to those without after adjusting for confounders (p=0.01). This particular population lacked the comorbid conditions commonly encountered in adults undergoing cardiac surgery, which limits generalizability. In this study, we are able to demonstrate that stage 1 AKI is independently associated with increased risk of infection, this time in a large adult population.

The mechanism by which AKI increases the risk of infectious complications is currently unknown. However, recent advances in immunobiology suggest that immunoparalysis may play a role. Immunoparalysis is an acquired immunodeficiency (25) that has been observed following sepsis (26), burns (27), trauma (28), and, notably, cardiac bypass surgery (29). When present, it has been found to increase the risk of subsequent infection and death (30). While immunoparalysis may be present for as many as 7 days in patients with sepsis, the time course following surgery is often much shorter, with resolution seen within 24 hours (29). Widespread derangements in the plasma metabolome have been noted in critically ill adult patients with pneumonia and AKI compared to pneumonia without AKI, demonstrating that the metabolome in AKI is distinct and identifiably different from similarly ill patients without AKI (31). These changes in metabolites could impact immune function, leading to either increased severity or prolonged time to resolution of immunoparalysis. Further studies evaluating the impact of AKI on underlying immune function are necessary and could suggest novel methods to decrease post-operative infection in this population.

Based on our results, we would advocate that providers evaluate patients using the KDIGO stage of AKI following surgery, rather than the STS definition of “renal failure,” which captures only stage 3 disease. This will allow for better stratification of patients with clinically significant stage 1 AKI and earlier implementation of interventions, such as renal bundles that have been shown to improve patient outcomes (32). The recently published PrevAKI trial (33) showed that implementation of a “KDIGO-based care bundle” which consisted of avoidance of nephrotoxic agents, discontinuation of ACE inhibitors for the first 48 hours after surgery, avoidance of hyperglycemia (glucose >150 mg/dL, avoidance when possible of contrast, and volume optimization using a pulse contour cardiac output (PiCCO) catheter significantly reduced the rates of AKI compared to standard care alone. The PrevAKI trial also utilized AKI biomarkers, which have the potential to further identify high-risk patients. While there was insufficient biomarker data available in this retrospective study, future research should focus on incorporating these tests into a protocol to identify and intervene as early as possible in patients at risk for kidney injury (34).

Our report does, however, have several important limitations. Given the retrospective nature of this study, it is possible that other confounding factors, such as returns to the operating room, may be present that were not accounted for in the analysis. We are also unable to evaluate the mechanism of increased infection in this population and cannot definitively say whether AKI plays a causal role in subsequent infection. We used a large database combined with the meticulous chart review allowing adjustment for a large number of covariates, and the use of a robust propensity-matching model utilizing variables known to be associated with postoperative infection. We also used median baseline creatinine to define AKI, and associations with subsequent infectious complications persisted.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that stage 1 post-surgical AKI is associated with increased risk of post-operative infection, prolonged ICU and hospital length of stay in adult patients undergoing non-emergent cardiac surgery. Future studies assessing the pathophysiological link between AKI and immune dysfunction leading to subsequent infectious complications are needed. Early identification of Stage 1 AKI will allow for earlier implementation of renal bundles which have been shown to improve patient outcomes. Treatment strategies focused on prevention, early recognition, and optimal medical management of AKI may decrease significant postoperative morbidity.

Supplementary Material

Central Picture:

Forest Plot Stage showing odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for primary and secondary outcomes in patients with Stage 1 acute kidney injury (AKI) compared to patients who did not develop AKI.

Data are displayed as numbers and percentages, except where indicated.

* Mean and interquartile range

Central Message:

Post-operative infection is a serious complication of cardiac surgery. In this study we demonstrate that stage 1 acute kidney injury is an independent risk factor for post-operative infection.

Perspective Statement:

Stage 1 AKI, defined as a rise in creatinine of 0.3 mg/dL, is independently associated with an increased risk of post-operative infection. AKI impacts multiple organ systems including the brain, lungs, liver, and in this study, the immune system. Given the widespread deleterious effects of AKI, prevention of kidney injury after cardiac surgery should be a future research priority.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

Authors would like to thank Kimberly J. Marshall, BSN, RN, CPHQ, AACC, Clinical Quality Specialist in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery at the University of Colorado, as well as Michael Wells, PAC, and Courtney Matter, PAC, for their assistance in data collection. We want to acknowledge the M-TRAC (Multidisciplinary Translational Research in AKI Collaborative) Investigators at the University of Colorado, Aurora for their support and input to this manuscript.

Funding: Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery Faculty Seed grant, Anschutz Medical Campus, University of Colorado, Aurora, CO; NIH Grant T32 DK 007135

Glossary of Abbreviations

- AKI

Acute Kidney Injury

- KDIGO

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- LOS

Length Of Stay

- UCH

University of Colorado Hospital

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- STS

Society of Thoracic Surgeons

- GEE

Generalized Estimating Equation

References

- 1.Crawford TC, Magruder JT, Grimm JC, Lee SR, Suarez-Pierre A, Lehenbauer D, et al. Renal Failure After Cardiac Operations: Not All Acute Kidney Injury Is the Same. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(3):760–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu JR, Zhu JM, Jiang J, Ding XQ, Fang Y, Shen B, et al. Risk Factors for Long-Term Mortality and Progressive Chronic Kidney Disease Associated With Acute Kidney Injury After Cardiac Surgery. Medicine. 2015;94(45):e2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Shah IK, Kashyap R, Park SJ, Kashani K, et al. Long-term Outcomes and Prognostic Factors for Patients Requiring Renal Replacement Therapy After Cardiac Surgery. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(7):857–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kellum JA, Lameire N. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit Care. 2013;17(1):204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortega-Loubon C, Fernández-Molina M, Carrascal-Hinojal Y, Fulquet-Carreras E. Cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury. Ann Card Anaesth. 2016; 19(4): 687–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chertow GM, Levy EM, Hammermeister KE, Grover F, Daley J. Independent association between acute renal failure and mortality following cardiac surgery. Am J Med. 1998;104(4):343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lassnigg A, Schmidlin D, Mouhieddine M, Bachmann LM, Druml W, Bauer P, et al. Minimal changes of serum creatinine predict prognosis in patients after cardiothoracic surgery: a prospective cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(6):1597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado MN, Nakazone MA, Maia LN. Prognostic Value of Acute Kidney Injury after Cardiac Surgery according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Definition and Staging (KDIGO) Criteria. PLoS One. 2014; 9(5):e98028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howitt SH, Grant SW, Caiado C, Carlson E, Kwon D, Ioannis D, et al. The KDIGO acute kidney injury guidelines for cardiac surgery patients in critical care: a validation study.BMC Nephrol. 2018; 19(1):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selby NM, Kolhe NV, McIntyre CW, Monaghan J, Lawson N, Elliott D, et al. Defining the cause of death in hospitalised patients with acute kidney injury. PloS One.2012;7(11):e48580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagshaw SM, Uchino S, Bellomo R, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, et al. Septic acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(3):431–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matejovic M, Chvojka J, Radej J, Ledvinova L, Karvunidis T, Krouzecky A, et al. Sepsis and acute kidney injury are bidirectional. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;174:78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faubel S, Shah PB. Immediate Consequences of Acute Kidney Injury: The Impact of Traditional and Nontraditional Complications on Mortality in Acute Kidney Injury. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016;23(3):179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowler VG Jr., O’Brien SM, Muhlbaier LH, Corey GR, Ferguson TB, Peterson ED. Clinical predictors of major infections after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2005;112(9 Suppl):I358–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ailawadi G, Chang HL, O’Gara PT, O’Sullivan K, Woo YJ, DeRose JJ Jr., et al.Pneumonia after cardiac surgery: Experience of the National Institutes of Health/Canadian Institutes of Health Research Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153(6):1384–91.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Likosky DS, Wallace AS, Prager RL, Jacobs JP, Zhang M, Harrington SD, et al. Sources of Variation in Hospital-Level Infection Rates After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: An Analysis of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Heart Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(5):1570–5; discussion 5–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strobel RJ, Liang Q, Zhang M, Wu X, Rogers MA, Theurer PF, et al. A Preoperative 349 Risk Model for Postoperative Pneumonia After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102(4):1213–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SooHoo M, Griffin B, Jovanovich A, Soranno DE, Mack E, Patel SS, et al. Acute kidney injury is associated with subsequent infection in neonates after the Norwood procedure: a retrospective chart review. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thakar CV, Yared JP, Worley S, Cotman K, Paganini EP. Renal dysfunction and serious infections after open-heart surgery. Kidney Int. 2003;64(1):239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanardo G, Michielon P, Paccagnella A, Rosi P, Calo M, Salandin V, et al. Acute renal failure in the patient undergoing cardiac operation. Prevalence, mortality rate, and main risk factors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107(6):1489–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin PC. A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Statistics in medicine 2014;33(6):1057–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates 362 between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Statistics in medicine 2009;28(25):3083–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Najafi M Serum creatinine role in predicting outcome after cardiac surgery beyond acute kidney injury. World J Cardiol. 2014;6(9):1006–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corwin HL, Sprague SM, DeLaria GA, Norusis MJ. Acute renal failure associated with cardiac operations. A case-control study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;98(6):1107–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall MW, Greathouse KC, Thakkar RK, Sribnick EA, Muszynski JA. Immunoparalysis in Pediatric Critical Care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017;64(5):1089–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):260–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venet F, Tissot S, Debard AL, Faudot C, Crampe C, Pachot A, et al. Decreased monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression after severe burn injury: Correlation with severity and secondary septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(8):1910–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tschoeke SK, Ertel W. Immunoparalysis after multiple trauma. Injury. 2007;38(12):1346–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strohmeyer JC, Blume C, Meisel C, Doecke WD, Hummel M, Hoeflich C, et al. Standardized immune monitoring for the prediction of infections after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery in risk patients. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2003;53(1):54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu JF, Ma J, Chen J, Ou-Yang B, Chen MY, Li LF, et al. Changes of monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression as a reliable predictor of mortality in severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2011;15(5):R220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsalik EL, Willig LK, Rice BJ, van Velkinburgh JC, Mohney RP, McDunn JE, et al. 385 Renal systems biology of patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Kidney Int. 2015;88(4):804–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalisnik JM, Pollari F, Pfeiffer S. Progression of cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury into acute kidney disease: A case for enhanced early kidney diagnostic fine-tuning implementation? The J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156(6):2180–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meersch M, Schmidt C, Hoffmeier A, Van Aken H, Wempe C, Gerss J, et al. Prevention of cardiac surgery-associated AKI by implementing the KDIGO guidelines in high risk patients identified by biomarkers: the PrevAKI randomized controlled trial. Int Care Med. 2017;43(11):1551–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizuguchi KA, Shekar P, Frendl G. Discovery of biomarkers that diagnose kidney disease progression and novel patient management strategies needed now to prevent progressive kidney disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156(6):2181–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.