Abstract

Rehabilitation psychology is based on foundational principles that can guide us toward health equity among disabled and nondisabled communities. We summarize the literature on disparities in the disability community and underscore the urgency to address underlying inequities to eliminate disparities. We include examples of population-level interventions that promote equity in the disability community. We conclude with a call for a broader mission for rehabilitation psychologists based on the field’s foundational principles, and outline emerging opportunities to widen our impact and advance equity. Our foundational principles, built on systems theory, call on rehabilitation psychologist to work at macrosystemic levels. As rehabilitation psychologists, we need to widen our focus from the micro (individual) to the macro (population) level. We need to bring the respect, dignity, and collaborative spirit that inspire our work with individuals to the broader community by advocating for structures and policies that promote equity for disabled persons.

Keywords: rehabilitation psychology, advocacy, disability, health equity, social justice

Introduction

In the prologue to Physical Disability: A Psychosocial Approach (2nd edition), Beatrice Wright (1983) demonstrated that promotion of access, inclusion, and social justice among the disability community has rested as the core of rehabilitation psychology for decades:

Major advances have occurred on medical and technological fronts, and landmark legislation has embodied some of the best ideas of modern rehabilitation. The past three decades witnessed a new affirmation of human and civil rights and a determination on the part of disadvantaged groups, including people with disabilities, to speak out and act on their own behalf. But how much can we count on continued progress? Some years ago my reply was “Not very much. … To assert otherwise would be to invite apathy” (Wright, 1972, p. 357). The elimination of attitudinal and other barriers that deny access to opportunities in the general life of the community is a mandate of basic human rights, but human rights are fragile insofar as they are subject to the vicissitudes of broad, sweeping social, economic, and political circumstances. (p. x)

Indeed, the writing of Wright and other influential early leaders like Roger Barker, Tamara Dembo, Kurt Lewin, and Lee Meyerson established a social justice imperative early in the development of the specialty. It was in Physical Disability: A Psychosocial Approach that Wright (1983) advocated for foundational principles in rehabilitation psychology’s research, educational, and clinical endeavors. Dunn, Ehde, and Wegener (2016) described the field of rehabilitation psychology as being “concerned with the psychological, biological, social, environmental, and political factors that influence the lives and well-being of people with disabilities or chronic health conditions” (p. 1). The principles, detailed in subsequent sections, can guide rehabilitation psychologists’ work to promote health equity for a broader community of disabled persons.

Purpose and Perspectives

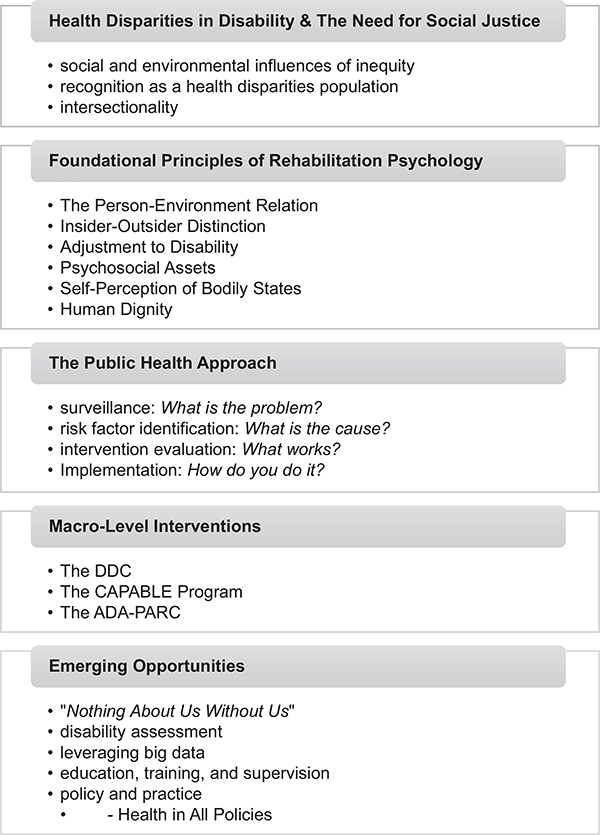

The purpose of this commentary is to call rehabilitation psychologists to action by broadening our work from the micro (individual) to the macro (population) level to promote equity across a broader group of disabled persons. Figure 1 presents an advanced organizer of our objectives, which are as follows: (1) highlight the need for social justice based on a nonsystematic review of the literature on health disparities and influences of inequities between disabled and nondisabled persons (Grant & Booth, 2009); (2) describe how rehabilitation psychologists can leverage our field’s foundational principles and principles of the field of public health, to address this need through population-level interventions; (3) provide examples of prior interventions implemented in disability communities; and (4) outline emerging opportunities for rehabilitation psychologists to promote health equity among disability communities.

Figure 1.

Advanced organizer of the commentary “Promoting Equity at the Population Level: Putting the Foundational Principles Into Practice through Disability Advocacy.” DDC = Durham Diabetes Coalition; ADA-PARC = Americans with Disabilities Act—Participatory Action Research Consortium.

This commentary reflects the perspectives of its authors and the zeitgeist of the field of rehabilitation psychology. We want to be explicit with respect to our decision about language use and our focus on disability topics predominantly within the U.S. In solidarity with Dunn and Andrews’ (2015) call for psychologists to employ the evolving language for disability, we use both person-first (i.e., people with disabilities) and identity-first (i.e., disabled persons) in this article. Doing so helps to combat stigma and prejudice about disability and highlights the “decision to exercise choice over one’s disability destiny” (Dunn & Andrews, 2015, p. 257). The U.S.-based framing of this commentary is not to minimize the importance of global health and policy. Rather, we want to highlight the challenges associated with the state of health care in the U.S.—that despite having the highest health care expenditures, the U.S. continues to have the poorest population health outcomes (OECD, 2015; Papanicolas, Woskie, & Jha, 2018). In this commentary, we focus on factors that adversely impact the disability community, such as the fee-for-service system and the underinvestment in addressing the social determinants of health, and that are primary determinants of health in the U.S. (Obama, 2016; Papanicolas et al., 2018).

We, as the authors, represent various disciplines and diverse intersections of race, ethnicity, disability, sex, and professional experiences. Notably, among the authors of this commentary are two women with disabilities, including a woman of color. Our work reflects the role of our various identities in shaping the experiences and needs of disabled persons. The disability community as a minority group is often discussed as if it is distinct from racial minority communities; however, there is substantial overlap among the two groups (Krahn, Walker, & Correa-De-Araujo, 2015). Traditionally, the disability literature has not given enough attention to people of color with disabilities (McDonald, Keys, & Balcazar, 2007). The historical lack of attention, coupled with the strong influence of racism in the U.S., has prevented many people of color from deeply reflecting on this aspect (disability) of identity (Banks, 2015; Levine & Breshears, 2019; McDonald et al., 2007). Thus, just as Dunn and Andrews (2015) called for increased flexibility in psychologists’ use of person-first and identity-first language, we ask readers to maintain this flexibility for how psychologists can broaden the impact of their work to promote health equity among a wider group of disabled persons, including those who have historically been underrecognized and underserved within our field.

Health Disparities in the Disability Community

The need for health equity stems from prevailing disparities among disabled and nondisabled persons, which span multiple contexts such as health care access, health behaviors, exposure to unhealthy environments, and insurance coverage (Krahn et al., 2015). Working-age adults with disabilities are over twice as likely than those without disabilities to delay or forego medical appointments because of concerns of costs, regardless of health insurance coverage status (Okoro, Hollis, Cyrus, & Griffin-Blake, 2018). People with physical disabilities are almost twice as likely to have unmet medical (75%), dental (57%), and prescription medication needs (85%; Mahmoudi & Meade, 2015). Disabled persons are at a greater risk for being a victim of nonfatal violent crimes, including rape, sexual assault, robbery, and (aggravated and simple) assault (Harrell, 2012; Rand & Harrell, 2009). Between 2011 and 2015, violent victimization against disabled persons occurred at almost a three times higher rate compared to the rate for nondisabled persons (12.7 per 1,000; Harrell, 2012). Higher rates of victimization among persons with disabilities compared to those without disabilities exist regardless of sex, race, or ethnicity.

Social and Environmental Influences of Inequity

The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) psychosocial framework captures the range of influences of inequities in a manner that previous models of disability overlooked (World Health Organization [WHO], 2002). The WHO characterizes disability and functioning as outcomes of interactions between health conditions and contextual factors. Moreover, empirical evidence points to social and built societal environments as leading contributors to existing health disparities between disabled and nondisabled persons, rendering these inequalities as largely preventable (Cieza & Bickenbach, 2015).

These contributing factors can range anywhere from the lengthy history in the U.S. of disenfranchising disabled persons through discriminatory practices, to creating legislation without considering the perspectives of appropriate stakeholders, primarily people with disabilities (Krahn et al., 2015). Such practices have resulted in major barriers to optimal quality of life and health for disabled persons, including social isolation, restricted mobility, social stigma, economic and institutional support, and architectural barriers (Cockerham, Hamby, & Oates, 2017; Hammel et al., 2015).

Livneh (2001) underscored the various social and societal factors that can impact disabled persons with a synopsis of the disability adaptation process. Adapting to chronic illness and disability broadly involves antecedents or triggering events of the disabling condition, the psychosocial adaptation process, and related anticipated outcomes of the process—which should be viewed through the lens of three contextual conditions: biological and biographical status, psychosocial status, and environmental conditions. Similar to the evolution of the field that should be reflected through our language usage and foundational principles, individuals’ experiences of adapting to disability likely will vary based on individual experiences and the zeitgeist (Dunn et al., 2016; Levine & Breshears, 2019; Livneh, 2001). For example, people with disabilities identified factors information technology access and economic well-being as key environmental barriers that arose with the advancement of technology and focus on work as central to one’s life within the Western U.S. culture (Hammel et al., 2015).

Social elements of disablement reveal the limitations in traditional models of disability, such as the biomedical or disease model. Notably, recognition of problematic elements of disablement has already led to population-level efforts demonstrating that disablement is not equivalent to impairment. Specifically, when disabled persons have the same environmental resources and opportunities as nondisabled persons, the so-called impairments are no longer substantial barriers to participation and inclusion (Krahn et al., 2015; WHO, 2002).

Recognizing the Disability Community as a Health Disparities Population

Classification of the disability community as such is important because federal recognition of such disparities allows for additional funding opportunities, consideration of disability perspectives in policymaking, and reallocation of resources to the disability community (Krahn et al., 2015; Turk & McDermott, 2017). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2010) outlines the following criteria for a group to be classified as a disparities population: (a) differences in population health outcomes that are (b) related to social, economic, or environmental historical disadvantages, and (c) are avoidable (Krahn et al., 2015; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010).

We outlined data from the existing literature and the ICF model that demonstrate the environmental factors that have led to the prevailing inequalities among disabled and nondisabled persons (WHO, 2002). These factors, known as the social determinants of health (SDOH), including gender, socioeconomic background (SEB), geographic location, and experiences of racial discrimination can impact health and well-being (Marmot, Friel, Bell, Houweling, & Taylor, 2008). Decisions made within and outside of the health care sector can equally result in adverse health consequences (Whitehead, 1991). A decision made in health care and another made in the finance industry can increase prescription costs, which can be a barrier to medication access for individuals from lower SEB. Over time, it is clear how such large-scale decisions can reinforce and maintain the inequities we currently observe. These SDOH that impact health and health care access for disabled persons are largely avoidable, thus meeting criteria to be recognized as a health disparity population per the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2010).

Intersectionality

The concept of intersectionality “allows for a more meaningful understanding of the systemic inequality experienced by individuals who have multiple minority identities,” which can reinforce one another in innumerable ways (Levine & Breshears, 2019, p. 148). Many people with disabilities often have other marginalized identities, which results in additional experiences of disadvantage as a result of the historical and systemic legacies that are perpetuated in society (Pal, 2011). Recognition of such marginalized identities and associated disadvantages is critical in the work of a psychologist (Rosenthal, 2016). Among the different identity categories, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and SEB are increasingly recognized in the disability literature (Crenshaw, 1991; Groomes, Kampfe, & Mapuranga, 2011; Nelson & Lund, 2017).

In the U.S., women, people of color, and particularly women of color experience disproportionately more disadvantages across sectors of society (Annamma, Connor, & Ferri, 2013; Brenner & Clarke, 2018). Women are more likely than men to report disability, and African Americans experience substantially higher disability rates than Whites (Okoro et al., 2018; Thorpe et al., 2014). Rates of chronic diseases are markedly higher among populations of color (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2009). Additionally, people of color are more likely to experience neighborhood stressors such as exposure to violence and health risks (e.g., poorer housing conditions, fewer health food options, fewer green spaces, and lower quality medical facilities) that increase likelihood of disability and chronic illness (Thorpe et al., 2014).

We highlight the disparities that exist at the intersection of disability with gender, and with race/ethnicity because of the gender- and race-based disparities literature that has proliferated in recent decades. It is, however, important to note that there are additional dimensions of intersectionality that are interwoven in the same complex ways that race/ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic status are, that shape our daily experiences of institutional discrimination for historically oppressed groups (Levine & Breshears, 2019; McDonald et al., 2007). Although outside the scope of this article, we remind rehabilitation psychologists to delve deeper into the intersecting identities that comprise the disability community in future research.

The Need for Social Justice

The pervasive systemic nature of inequities and disparities has contributed to the complacency of society in allowing for these injustices to exist in the disability community. Social justice and the preventable nature of existing disparities warrant increased attention and action to reduce health inequities. According to Braveman, Arkin, Orleans, Proctor, and Plough (2017),

Social justice means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care. (p. 2)

Health equity is widely viewed as “social justice in health” because disparities are the direct result of inequitable practices of society, including the allocation of resources needed to maintain health (Braveman et al., 2011). Equity, which is often interchangeably used with quality, refers to fairness and justice, whereas equality refers to sameness. This distinction is important given that disabled persons are part of a historically underserved group that has experienced disadvantages that have accumulated over time. Because of this history, disabled persons are more likely than nondisabled persons to encounter obstacles to optimal health (Krahn et al., 2015; Thorpe et al., 2014).

To promote equality among the disability community, disabled persons would continue to receive the same resources as nondisabled persons regardless of whether this method addresses the barriers resulting directly from a history of disadvantage. To promote health equity in disability, however, reallocation of more resources for the disability community in order to remove the entrenched barriers to optimal health care access would be warranted. The concept of equity has been represented in different areas of disability studies, including Kosciulek’s (1999) consumer direction approach and Young’s (1990) notions of distributive justice. A consumer-directed system involves informed consumers who have control and opportunity to make decisions and influence policymaking (Kosciulek, 1999). Consumer direction would allow disabled persons to assess their own needs, determine how their needs can be met, and evaluate the method used to meet these needs. The distributive paradigm of justice focuses on the morally proper allocation of social benefits and burdens among members of society (Young, 1990). These can include material resources (e.g., wealth and income) as well as social goods (e.g., rights, opportunity, power, and self-respect).

Foundational Principles of Rehabilitation Psychology

To address this need for health equity, we as rehabilitation psychologists must leverage the resources available to us—our foundational principles, which are inherently social justice in nature. Dunn et al. (2016) summarized the foundational principles to include the Person–Environment Relation, Insider–Outsider Distinction, Adjustment to Disability, Psychosocial Assets, and Human Dignity. They declared that the principles “represent more than an abstract or aspirational philosophy,” and as a result, should intentionally guide population-level efforts within the field (p. 2). The foundational principles are dynamic in nature and should evolve with the field, particularly if they are no longer useful in the existing zeitgeist. Table 1 outlines the principles, which are also explained below.

Table 1.

Foundational Principles of Rehabilitation Psychology

| Principle | Definition |

|---|---|

| The Person–Environment relation | Attributions about people with disabilities tend to focus on presumed dispositional rather than available situational characteristics. Environmental constraints usually matter more than personality factors to living with a disability. |

| The Insider–Outsider distinction | People with disabilities (insiders) know what life with a chronic condition is like (e.g., sometimes challenging but usually manageable) whereas casual observers (outsiders) who lack relevant experience presume that disability is defining, all encompassing, and decidedly negative. |

| Adjustment to disability | Coping with a disability or chronic illness is an ongoing dynamic process, one dependent on making constructive changes to the social and the physical environment. |

| Psychological assets | People with disabilities possess or can acquire personal or psychological qualities that can ameliorate challenge posed by disability and also enrich daily living. |

| Self-Perception of bodily states | Experience of bodily states (e.g., pain, fatigue, distress) is based on people’s perceptions of the phenomena, not exclusively the actual sensations. Changing attitudes, expectations, or environmental conditions can constructively alter perceptions. |

| Human dignity | Regardless of the source or severity of a disability or chronic health condition, all people deserve respect, encouragement, and to be treated with dignity. |

Note. From “The Foundational Principles as Psychological Lodestars: Theoretical Inspiration and Empirical Direction in Rehabilitation Psychology,” by D. S. Dunn, D. M. Ehde, and S. T. Wegener, 2016, Rehabilitation Psychology, 61, p. 2. Copyright 2016 by American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

The Person–Environment Relation

Kurt Lewin (1935) developed the framework for understanding the interactions between person and environment, B = f(P, E), where B represents an observable behavior, P represents the within-factors that influence behaviors (e.g., states and traits), and E represents external environmental factors in one’s physical and social surroundings. This is consistent with the WHO Organization’s ICF model (WHO, 2002), which construes disability as a complex interaction between person and environment. Both frameworks demonstrate the meaning of the principle of the Person–Environment Relationship, which views human behavior as a function of person–environment interactions.

Insider–Outsider Distinction

The Insider–Outsider Distinction represents discrepancies in perceptions of disabled and nondisabled persons (Dembo, 1964). Nondisabled individuals may assume that disabled persons let their disability define who they are and experience ongoing preoccupation about their conditions. Disabled persons, however, know from experience that their disability or chronic condition is only one of the multiple rich aspects of their lives, which also include family, career, hobbies, and more (Duggan & Dijkers, 2001). This foundational principle highlights the rationale for inclusion of disabled persons in our work.

Adjustment to Disability

Adjustment to chronic illness and disability is an ever-changing process involving adaptation and acceptance by the individual (Dunn et al., 2016; Livneh, 2001). These three processes are linked in a unique manner that varies based on the individual and their ability to: (1) develop a constructive perspective on their abilities and potential for future success; (2) have a positive self-concept; (3) possess a sense of personal mastery and to effectively navigate their social and physical environments (Dunn et al., 2016).

Psychosocial Assets

Beatrice Wright was a strong proponent for the strengths or assets of each individual regardless of the presence and severity of disability or chronic condition (Dunn & Andrews, 2015; Wright, 1983). Assets can be intangible (e.g., self-concept or personality) or tangible (e.g., financial resources or income). To capitalize on individuals’ strengths to reach their goals across clinical settings has been a key function of rehabilitation psychologists in patient care.

Self-Perception of Bodily States

People’s subjective perceptions largely determine how they think, feel, and act (Wegner & Gilbert, 2000). This principle explains how individuals’ experience of pain, stiffness, or fatigue is based on their own perceptions and the perceptions of others’, regardless of the actual sensations that may be present (Fordyce, 1984; Main, Keefe, Jensen, Vlaeyen, & Vowles, 2015). Perceptions and behaviors can be modified for good or for bad according to our attitudes, expectations, and environmental factors—and thus, serve as targets for intervention.

Human Dignity

“An essential core-concept of human dignity is that a person is not an object, not a thing” (Wright, 1972, p. 12). The principle of Human Dignity signifies that every person has a right to be respected, encouraged, and treated as a human being regardless of the form (physical, intellectual, or cognitive) or severity of disability or the presence of chronic illness. This, among the other foundational principles, should underlie any efforts by our field to promote health equity among disabled persons.

The Public Health Approach

The shared focus between our field and the field of public health on the role of environmental factors in shaping disability and chronic health outcomes suggest the benefits to be had with interprofessional collaboration (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014; Wright, 1983). Public health, however, focuses on change at the population (macro) level, whereas we as rehabilitation psychologists have traditionally had a heavier focus at the individual (micro) level (MacLachlan, 2014). The value of public health in broadening the scope of our work as rehabilitation psychologists can be evidenced across the stages of the public health model: surveillance (“What is the problem?”); risk factor identification (“What is the cause?”); intervention evaluation (“What works?”); and implementation (“How do you do it?”; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014).

Just as rehabilitation psychology’s foundational principles have inherent social justice imperatives, health equity has been a driving force for public health since inequities by social class and social status resulted in inequalities in health (Fee & Gonzalez, 2017). The field of public health is based on principles that overlap with those of rehabilitation psychology, which underscore the role of environmental factors in health outcomes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014; Wright, 1983). Per the Institute of Medicine, the mission of public health is to “fulfill society’s interest in assuring conditions in which people can be healthy” by using its core model, which is consistent with our social justice ethos (Institute of Medicine U.S. Committee for the Study of the Future of Public Health, 1988; Wright, 1987).

Macro-Level Interventions

To date, many of the efforts of rehabilitation psychologists have focused on affecting change at the individual level—for patients and their caregivers (MacLachlan, 2014; Wright, 1983). However, current disparities among the disability community warrant greater focus on community- and population-level programs aligned with the common ethos of rehabilitation psychology and public health (Bentley, Bruyère, LeBlanc, & MacLachlan, 2016; MacLachlan, 2014). This is vital if we want to reach broader groups of persons with disabilities, particularly those with multiple intersecting identities who may have been historically overlooked by disability scholars—or at least have had their identity categories other than disability (e.g., gender, race, sexual orientation, and SEB) overlooked. We as rehabilitation psychologists need more pursuit of macrolevel systematic change by championing disability as a human rights and social justice issue while working to “[move] communities and organizations toward greater access for all in the healthcare space, the workplace, and public engagement” (American Psychological Association, n.d.).

Indeed, these vision statements clearly articulate the relevance and applicability of rehabilitation psychology interventions across community, organizational, and policy environments. We as rehabilitation psychologists should intentionally focus on translating these inherent social justice imperatives into macro-level systemic change. We now explore three public health interventions that are consistent with our field’s foundational principles and serve to promote health equity among the nondisabled and disabled community. We will outline major components of each intervention and its intersection with the foundational principles to highlight how they may serve as models for future work.

The Durham Diabetes Coalition (DDC; Spratt et al., 2015)

The DDC was a community-based demonstration project developed, in response to rising disability and death rates in underserved populations, to improve health and health care delivery for residents with diabetes in Durham County, North Carolina. The DDC’s overall goal was to improve diabetes-related outcomes at the individual, neighborhood, and population levels through implementation of interventions pertaining to the “triple aim” of (1) enhancing health, (2) improving health care, and (3) reducing costs. It involved a partnership among the Duke University Health System, Durham County Department of Public Health, National Center for Geospatial Medicine at the University of Michigan, Lincoln Community Health Center, and a community advisory board with over 20 public, political, and private community organizations.

The intervention involved education on diabetes self-management, support for managing diabetes and associated distress, enhanced access to and improved quality of health care, community organization, mobilization, and advocacy, and health system and community transformation. The strategies proposed for sustainability of the DDC include the following: sharing resources with organizations who have similar goals; incorporating their activities/services into another organization with a similar mission; applying for grants; tapping into available resources among personnel; soliciting in-kind support; and developing a fee-for-service structure.

The foundational principles of Person-Environment Relation and Psychosocial Assets were exemplified in the DDC through its core health equity practices. The program involved reallocation of resources to individuals with the highest risk for dealth or hospitalization, and the stratification of intervention intensity based on individual need. Use of the geographic health information system allowed the DDC to address environmental and social factors that impact diabetes and disability. It matched specific resources to those community with the greatest need for those resources. Moreover, it leveraged the psychosocial assets, or strengths, that individuals already possess to optimize health outcomes with intervention. The DDC further capitalized on the strength of people with disabilities by involving them as stakeholders in the Community Advisory Board. Environmental, social, and psychosocial factors and strengths of participants informed the community-based programs for diabetes care.

The Community Aging in Place, Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE) Program (Szanton, Leff, Wolff, Roberts, & Gitlin, 2016; Szanton et al., 2011, 2014)

The CAPABLE Program was developed to reduce the impact of disability on older adults with lower-income backgrounds by targeting their home environments. The programs was made available to residents of all but the wealthiest neighborhoods in Baltimore, Maryland. To reduce the overall impact of disability by improving functional outcomes among older adults, the CAPABLE Program involved multidisciplinary care teams that delivered patient-centered interventions. It employed individually tailored interventions based on people’s goals and risk profile to neighborhoods with the greatest need. These interventions enhanced control (e.g., ability to problem solve and reframe difficulties) and reduced factors that undermine control (e.g., unsafe structures [stairs] in their homes, chronic pain). These factors involved both intrinsic (person-based) and extrinsic (environment-based), modifiable risk factors.

The core practices of the CAPABLE program were well aligned with the foundational principles of Person-Environment Relation, Adjustment to Disability, and Psychosocial Assets. The program considered the assets that each person possesses to develop interventions specifically tailored to each participant. In addition, recognizing the significant role of the physical environment in disablement, the CAPABLE program made changes to individuals’ physical home environments to optimize physical functioning. The individualization of interventions was likely among the major factors that led to improvements in physical functioning across all demographic and chronic disease groups of participants.

The Americans With Disabilities Act—Participatory Action Research Consortium (ADA-PARC; Hammel et al., 2015; Hammel, McDonald, & Frieden, 2016)

The ADA-PARC was developed to identify and address disparities among disabled persons across three participation dimensions: community living, community participation, and economic participation. It employs a participatory action research (PAR) approach involving six ADA centers, community leaders, and disabled persons as stakeholders for a better understanding of how one’s built environment impacts participation among disabled and nondisabled persons. PAR is the leading approach in research used to promote equity because of its effectiveness in reducing health disparities (Hall, 1981; Viswanathan et al., 2004). It involves a shift in power that is equally distributable across stakeholders, including researchers and disabled persons, across all stages of the study.

The project involved a set of indicators for each of the three participant dimensions, leading to the development of the ADA-PARC Participation and Disability Index. This index assesses multiple domains of how well a city, county, or any other setting is performing in terms of livability, safety, participation, and so forth, for disabled persons. The ADA-PARC project also highlights the critical role that stakeholder engagement and knowledge translation are in shaping the direction and, ultimately, success of such a large project. To sustain the project’s impact, the public data is available for use to inform future resource dissemination and guide community stakeholders to increase the level of opportunities for participation among individuals with disabilities in their own communities.

The ADA-PARC is a project that was informed by every foundational rehabilitation psychology principle. It recognized the environment’s role in disablement and facilitated the process of adjustment to disability by making communities more livable to optimize community participation among disabled persons. Notably, the ADA-PARC highlighted the importance of involving disabled persons across various stages of the project. In this manner, the project highlighted the psychosocial assets of disabled persons, embodied the principle of human dignity, and minimized the potential risk of developing interventions from only an “outsider” perspective (i.e., that disability is all-encompassing).

Emerging Opportunities to Promote Equity on a Broader Level

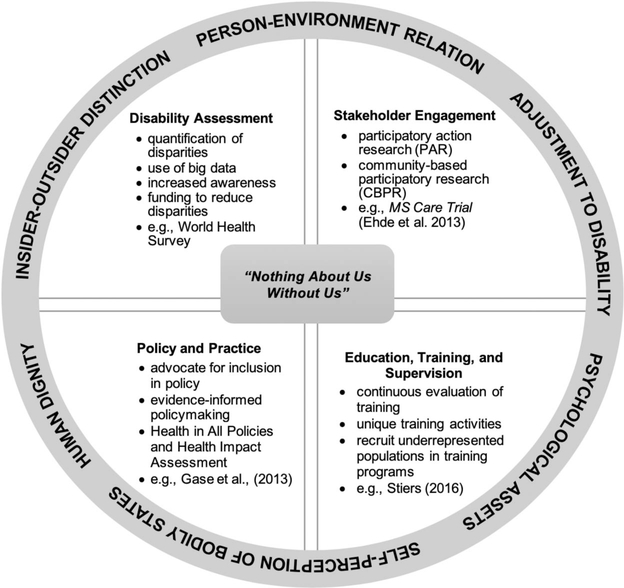

These population-level interventions share commonalities that are central to the fields of rehabilitation psychology and public health in that they (1) are grounded in one or more rehabilitation psychology foundational principles; (2) target population health metrics; (3) are data-driven; and (4) include a plan for sustainability. Factors such as these will be important to incorporate in our future work, as rehabilitation psychologists, to promote health equity among disabled persons (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014; Dunn et al., 2016; Wright, 1987). We now outline emerging opportunities for the field to reach a broader group of disabled persons and to promote health equity among the disability community. These opportunities are also presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Rehabilitation psychology foundational principles and emerging opportunities for rehabilitation psychologists to promote health equity among the disability community.

“Nothing About Us Without Us”

The effectiveness of disability advocacy rests largely on the involvement of disabled persons across all stages of advocacy action (Scotch, 2009). This notion is captured well by the international disability movement’s motto of “Nothing About Us Without Us,” which reifies the necessity to integrate disabled persons in all aspects of political, social, economic, and cultural sectors of society (Scotch, 2009). Disabled persons have experienced an array of disadvantages in society largely due to large-scale decisions about them, without them—without the key stakeholders who are regularly impacted by the issue in focus. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) highlighted the benefits of this practice in research: “Research is more likely to improve the care of patients if they and other key stakeholders are involved in all aspects” (Selby, Forsythe, & Sox, 2015, p. 2235). It is for this reason that PCORI was authorized by the U.S. Congress as a novel stakeholder-driven approach in clinical effectiveness research. Since then, we have seen a significant shift in the health care space to focus on patient-centered practice.

Although this is not a new practice for rehabilitation psychologists given the inherent social justice nature of our field, including disabled persons as stakeholders in every step of the research process is (Bentley et al., 2016; Ehde et al., 2013, 2018; Motl et al., 2018). This may also help to explain why some of the literature in the field has yielded findings that are not always sustainable in the long term (Ehde et al., 2013). In the health care space, rehabilitation psychologists regularly employ interventions to facilitate patients’ adjustment to disability, thereby producing microlevel change (Elliott & Rath, 2012). However, microlevel change does not address the larger, systemic, prevailing inequalities in our society that have an adverse impact on daily functioning for some people with disabilities (i.e., the person–environment relation). Including disabled persons as key stakeholders in the development of interventions, particularly as they would apply across underresourced communities, would allow us as researchers and clinicians to learn about the most pressing needs and optimal methods to expand our positive impact from the individual to the population level. There is great benefit to be had by informing our health equity efforts by the lived experiences of the disability community.

The practice of involving stakeholders throughout the research process has become widely recognized as PAR, which is the framework employed to develop the ADA-PARC (Hammel et al., 2016; White, Suchowierska, & Campbell, 2004). PAR is characterized by the inclusion of participants as key stakeholders throughout the phases of research, including (1) agenda setting, which involves identifying research priorities and topics relevant to the community of focus; (2) designing the study, which includes procedures implemented, measures used, and intervention development; (3) implementing the intervention of study, which can entail training staff and interventionists, recruitment/retention of staff and participants, delivery of the intervention, and troubleshooting as needed; (4) dissemination of study findings and implications to the scientific community as well as to relevant stakeholders, consumers, and the public; and (5) sustainability of intervention of focus, which can entail clinical services, programs, policy, and advocacy (Ehde et al., 2013).

Of note, PAR is linked to the traditional Action Research approach as developed by Kurt Lewin (1946). Action Research as an approach is grounded in the social psychological research tradition of rehabilitation psychology—that the action will improve a particular situation. The work continues until a particular criterion is met, or an obstacle requires the researcher(s) to revise the intervention to try again. PAR is known for its numerous benefits to participants and researchers alike, including the improvement of external validity while also maintaining scientific rigor (White et al., 2004). Additional benefits include, but are not limited to, the following: optimal feasibility of research study methods, especially when working with historically underserved community populations; increased relevancy of research findings; identification of meaningful future agendas for research; and appropriate methods of dissemination of study findings.

PAR is employed in the field of public health, where it is often referred to as community-based participatory research (CBPR), one of the eight new competencies for all health professional trainees (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). CBPR is defined as the following:

… a collaborative research approach that is designed to ensure and establish structures for participation by communities affected by the issue being studied, representatives of organizations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process to improve health and well-being through taking action, including social change. (Viswanathan et al., 2004, Summary)

CBPR has gained significant traction in the last decade due to its effectiveness in reducing racial/ethnic health disparities (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). This approach expands on traditional research designs by emphasizing the equitable distribution of power among investigators, academic partners, and community members, including disabled persons. Compared to traditional research methods, the improved external validity and effectiveness of CBPR makes it ideal for rehabilitation psychologists to promote health equity among broader groups of people with disabilities, including those with multiple intersecting identities who maybe underserved from prior disability work.

Many PAR studies are also founded on principles of collaborative care models that include an integrated patient-centered provider team, population-based methods, measurement-based treatment, evidence-based care, and accountable care (Ehde et al., 2018). These models have also shown to be effective in improving various symptoms of chronic health conditions including depression and anxiety (Archer et al., 2012). Within the field of rehabilitation psychology, the Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Care Trial by Ehde and colleagues (2018) can serve as a model for future work involving participants as stakeholders within a collaborative care approach. The MS Care Trial involved MS care managers, MS providers, primary care providers, specialty consultants, consulting psychologists with MS expertise, consulting psychiatrists, and consulting medical pain experts (Ehde et al., 2018).

PAR or CBPR, with the use of a collaborative care treatment model, proves to be advantageous for the field of rehabilitation psychology. Incorporating PAR into rehabilitation research will move our field closer toward achieving the fundamental goal of advocating with and for individuals with disabilities. Ehde and colleagues (2013) have outlined recommendations for promoting PAR in rehabilitation intervention research, which are as follows: (1) Use PAR terminology when describing stakeholder involvement in rehabilitation intervention research; (2) draw on public health’s history of CBPR for ideas on implementation of PAR in rehabilitation intervention research; (3) engage stakeholders in intervention research as much and as soon as possible to maximize research quality and knowledge translation; (4) conduct research on the PAR process, including its impact on research, services, knowledge translation, and policy; and (5) build more support for PAR into the rehabilitation research environment (see Ehde et al., 2013, for more information).

Models of PAR in rehabilitation research that can serve as guides for rehabilitation psychologists include the PALS study (Wegener, Mackenzie, Ephraim, Ehde, & Williams, 2009) and others listed in Ehde et al.’s (2013) article: Hibbard et al. (2002); Jernigan and Lorig (2011); Langston, McCallum, Campbell, Robertson, and Ralston (2005); Langston et al. (2010); Nomura et al. (2009); and Ravesloot et al. (2007).

Disability-Related Assessment

Assessment, which involves quantifying the existing, preventable inequalities among disabled and nondisabled persons, is one of the necessary first steps in promoting equity. The quantification of disparities is what leads to raised awareness among the public and funding for initiatives to reduce disparities across populations (Krahn et al., 2015). To optimize health care and health for all, a uniform characterization of individuals with elevated health care needs (e.g., disabled persons and/or persons with chronic conditions) is necessary (Gulley et al., 2018). The current state of disability indicators for health services research is problematic because of the significant variability in individual differences in people’s experience of disability, as well as the wide range of methods to assess disability that exist.

To effectively identify individuals with elevated health care needs, we need a uniform method to capture the needs of patient populations. Rehabilitation psychologists can leverage our background in psychometrics to contribute to national and international efforts at developing a uniform measure of disability (WHO, 2002). Some ongoing disability measurement efforts include the World Health Survey, Global Burden of Estimates, and local disability measurement initiatives (MacLachlan & Mannan, 2014).

Leveraging Big Data

Electronic medical records (EMR) with rehabilitation data can serve as rich sources for research on administrative health information (e.g., timeliness of care, care and appointment access), providers’ progress notes, and patient-powered data (e.g., patient health status, fall risk, measurements, and medications; Bettger et al., 2018). Publicly available data provide an opportunity for rehabilitation psychologists to contribute to a better understanding of existing health and health care disparities among disabled persons and nondisabled persons in access to care, quality of care, and screening practices.

National databases that are available for rehabilitation psychologists include (a) the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, which is the U.S. system that uses telephone surveys to assess individuals’ health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, and the use of preventative care; (b) the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Disability and Health Data System, which contains data on adults with disabilities at the state level; (c) the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey, which is a national survey that asks individuals about information related to disability, housing, demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics; (d) the National Health Interview Survey, which captures information on a variety of health-related topics (e.g., health insurance status, physical activity, disability questions) collected through personal interviews; (e) the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which collects data on the health and nutritional status of individuals nationwide using in-person interviews; and (f) the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, which includes a set of large-scale surveys to collect data on health care cost and health insurance coverage (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011, 2012, 2014; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Division of Human Development and Disability, 2012; Cohen, Cohen, & Banthin, 2009).

Given the substantial impact of policy on practice, the use of health services research can be a middle tool to facilitate communication among policy, practice, and patient outcomes (Graham, Middleton, Roberts, Mallinson, & Prvu-Bettger, 2018). We as rehabilitation psychologists should build on our collaborations with public health professionals and community/hospital administrators to better identify needs of various disability patient populations using the EMR (Bettger et al., 2018). Although the EMR necessitate real-world stakeholder input, they nonetheless provides a valuable steppingstone for such stakeholder engagement by elucidating potential areas of need.

Rehabilitation psychologists are equipped with the knowledge, with input from the disability community, and the skills to define rehabilitation in policy-relevant contexts and guide the reforms that affect rehabilitation care (Bettger et al., 2018; Graham et al., 2018). At the same time, we must acknowledge how health services data within the country’s pay-for-service model is as biased as the inherently biased health care space from which the data are obtained (Kaplan, Chambers, & Glasgow, 2014). We encourage rehabilitation psychologists to carefully consider the benefits to be had with negative consequences, albeit unintended, before utilizing large sources of health services data (Kaplan et al., 2014).

Education, Training, and Supervision

The future of our field and the sustainability of macro-level interventions to promote health equity in disability are not possible without appropriate training of future generations in our field (Stiers, 2016; Stiers et al., 2015). Part of the education and training of rehabilitation psychologists requires that trainees acquire the specialty-specific values, attitudes, knowledge, and skills related to the principles described by Wright (1983). Stiers (2016) describes a curriculum to teach disability-specific processes and values as part of rehabilitation psychology training program content and components. To optimize the quality of training for future leaders of our field, rehabilitation psychologists must take an active role within their own specialty by continually evaluating and reevaluating the quality and effectiveness of training programs. Unique training activities (e.g., service-learning techniques, disability simulation experiences) are valuable additions to training programs to help individuals understand the experience of people with disabilities (Stiers, 2016). The use of PAR can also optimize trainees’ understanding of the experiences of disabled persons.

The special issue of the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, “Effective Mentorship and Research Designs to Engage Underrepresented Populations,” highlights the invaluable insight that research scholars and faculty from underrepresented populations (based on ability status, race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic background, etc.) may hold into the complex origins and solutions to reduce health disparities (Wyatt & Belcher, 2019). Rehabilitation psychologists should recognize the importance of recruiting and mentoring a diverse group of early career professionals for the future of the field and sustainability of programs promoting health equity among the disability community.

Policy and Practice

Just as research informs evidence-based interventions for the disability community, it should also inform policy and practice. The field of Rehabilitation psychology has a long history of policy influence that can be observed at the local, national, and international levels (Bentley et al., 2016). Rehabilitation psychologists, in collaboration with the disability community, can work to establish and maintain connections with local and national policymakers to advocate for policies and systems changes that promote health equity. Perhaps more to the point, we can advocate for the involvement of disabled persons across settings where policymaking and practice guidelines are developed.

We can advocate for inclusion of disabled persons as team members in community-based implementation studies by helping team members understand that disability is not all-encompassing and provides a unique perspective (Insider–Outsider Distinction). There is a need for more dissemination and implementation research, which “seeks to understand how to systematically facilitate deployment and utilization of evidence-based approaches to improve the quality and effectiveness of health promotion, health services, and health care,” and we as rehabilitation psychologists can advocate for disabled persons’ involvement as key stakeholders throughout these processes (Tabak, Khoong, Chambers, & Brownson, 2012, pp. 1–2).

Consulting with individuals from other professions in health equity efforts allows rehabilitation psychologists the opportunity to advocate for change at the macro level (Cox, Hess, Hibbard, Layman, & Stewart, 2010). For example, we can provide consultation services to public health researchers who implement novel community-level interventions among people with disabilities to ensure the promotion of independent living, participation, and empowerment.

To support evidence-informed policymaking, rehabilitation psychologists can employ evidence briefs and deliberative dialogues—approaches that are highly regarded and have led to an intent to act by policymakers across multiple countries (Moat, Lavis, Clancy, El-Jardali, & Pantoja, 2014). Evidence briefs involve the identification of a priority policy issue relevant within the health system, coupled with synthesized evidence based on the highest quality of global research (e.g., systematic reviews) and relevant community-specific findings that are used to define the problems associated with the policy issue, potential solutions, and the main considerations in implementation of each solution. These briefs are then used as primary inputs for the deliberative dialogues that are meant to encourage interactions among policymakers, relevant stakeholders, and researchers.

These dialogues increase the likelihood that the evidence informs policymaking, particularly if they include the following information: addressing a high-priority policy issue; describing the context and various features of a problem and the way it impacts different subgroups; outlining potential solutions; elaborating what is currently known and the gaps in knowledge that remain about the solutions; taking equity, quality, and local applicability into account; and receiving support by the various groups of individuals who are affected by the issue (Moat et al., 2014).

Health in All Policies (HiAP)

Health disparities are the result of inequitable practice across multiple sectors of society; therefore, addressing them requires multilevel, multidisciplinary interventions (Carla, 2010; Pollack, Givens, & Tung, 2014; World Health Organization, 2014, 2015). HiAP is a framework designed to address these inequitable practices spanning the multiple sectors of society (Kickbusch, 2013). HiAP, which emerged in the last few decades, is founded on the principles of social justice and human rights. HiAP can be an effective tool because it highlights how decisions made in sectors other than health care (e.g., agriculture, education, the environment, finance, housing, and transportation) can impact health. Moreover, it shows how people’s improved health can advance goals of sectors even if they are outside of the health care space. HIAP identifies policymaking as a means to improve population health, health equity, and health systems (Leppo, Ollila, Pena, Wismar, & Cook, 2013; WHO, 2014, WHO, 2015):

Health in All Policies (HiAP) is an approach to public policies across sectors that systematically takes into account the health and health systems implications of decisions, seeks synergies, and avoids harmful health impacts, in order to improve population health and health equity. A HiAP approach is founded on health-related rights and obligations. It emphasizes the consequences of public policies on health determinants, and aims to improve the accountability of policymakers for health impacts at all levels of policymaking. (Leppo et al., 2013, p. 3)

Health Impact Assessments (HIA) is an approach that is increasingly being used to implement HiAP (Erwin & Brownson, 2017; Heller et al., 2014). A core value of HIA practice is the promotion of equity by elucidating impacts of policies on various populations. This process is then used to empower communities that have been marginalized (Heller et al., 2014). Heller and colleagues (2014) outlined Equity Metrics as evaluation tools to assess the effectiveness of HIA practice to promote equity, which include four overall outcomes: (a) The HIA process and products focused on equity; (b) the HIA process built the capacity and ability of communities facing health inequities to engage in future HIAs and in decision-making; (c) the HIA resulted in a shift in power beneficing communities facing inequities; and (d) the HIA contributed to changes that reduced health inequities and inequities in the social and environmental determinants of health.

In our field, rehabilitation psychologists can leverage HIA as a means to HiAP to promote equity among the disability community. The inclusion of people with disabilities throughout each stage of such efforts will be critical for sustained positive outcomes. The WHO’s website, Health in All Policies: Framework for Country Action, provides additional information for countries to adapt and implement HiAP: https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/frameworkforcountryaction/en/. For rehabilitation psychologists in the U.S., Gase, Pennotti, and Smith (2013) offer an invaluable “menu” of options to guide the incorporation of HiAP, including seven strategies, associated tactics, and emerging practices (published in the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, Vol. 19).

Conclusion: A Call to Action

Of the rehabilitation psychology foundational principles summarized by Dunn et al. (2016), the most basic and most important is human dignity. This principle highlights each person’s right to be respected, encouraged, and treated as a human being regardless of the form or severity of disability and/or the presence of chronic illness. Simply stated, “An essential core concept of human dignity is that a person is not an object, not a thing.” (Wright, 1987, p. 12) The idea that an individual deserves respect should guide the development of any intervention—whether it is at the micro- or macrolevel.

To eliminate present day health disparities between disabled and nondisabled persons, an interdisciplinary and collaborative approach grounded on the principle of human dignity and inclusive of relevant stakeholders will be critical to achieve health equity. Rehabilitation psychologists, joined with public health professionals and people with disabilities—although these groups are not always mutually exclusive—can address underlying systemic inequities at the population level by shifting power from the traditional parties (e.g., academic researchers) to individuals who experience direct consequences of existing disparities. Social justice is at the root of rehabilitation psychology foundational principles, and now is the time to be intentional in expanding our reach beyond individuals to the communities, cities, counties, and larger social structures in which they live (Dunn et al., 2016).

Impact and Implications.

This article underscores the existing health disparities, and influence of inequities, among people with disabilities and chronic health conditions; informs readers about the inherent social justice nature of rehabilitation psychology’s foundational principles, which can guide the field in promoting equity among individuals with disabilities and chronic conditions; and recommends that we, as rehabilitation psychologists, broaden our focus from the micro (individual) to the macro (population) level by joining our approaches with the field of public health to promote equity among a wider group of disabled persons.

Acknowledgments

During the initial submission of the manuscript, Jagriti ‘Jackie’ Bhattarai was a postdoctoral fellow supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society Award MB0032 (PI: Beier). Jagriti ‘Jackie’ Bhattarai is currently supported by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Disparities Solutions Pilot Award (Grant U54MD000214; PI: Jagriti ‘Jackie’ Bhattarai) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award K23MD014176 (PI: Jagriti ‘Jackie’ Bhattarai).

Contributor Information

Jagriti ‘Jackie’ Bhattarai, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Jacob Bentley, Seattle Pacific University.

Whitney Morean, Seattle Pacific University.

Stephen T. Wegener, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Keshia M. Pollack Porter, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

References

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Rehabilitation psychology. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/about/division/div22

- Annamma SA, Connor D, & Ferri B (2013). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 16, 1–31. 10.1080/13613324.2012.730511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, Lovell K, Richards D, Gask L, … Coventry P (2012). Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ME (2015). Whiteness and disability: Double marginalization. Women & Therapy, 38, 220–231. 10.1080/02703149.2015.1059191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley JA, Bruyère SM, LeBlanc J, & MacLachlan M (2016). Globalizing rehabilitation psychology: Application of foundational principles to global health and rehabilitation challenges. Rehabilitation Psychology, 61, 65–73. 10.1037/rep0000068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettger JP, Nguyen VQC, Thomas JG, Guerrier T, Yang Q, Hirsch MA, … Niemeier JP (2018). Turning data into information: Opportunities to advance rehabilitation quality, research, and policy. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 99, 1226–1231. 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.12.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Arkin E, Orleans T, Proctor D, & Plough A (2017). What is health equity? Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman PA, Kumanyika S, Fielding J, Laveist T, Borrell LN, Manderscheid R, & Troutman A (2011). Health disparities and health equity: The issue is justice. American Journal of Public Health, 101, S149–S155. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner AB, & Clarke PJ (2018). Understanding socioenvironmental contributors to racial and ethnic disparities in disability among older Americans. Research on Aging, 40, 103–130. 10.1177/0164027516681165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carla M (2010). Healthy people 2020: Social determinants of health. Rockville, MD: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid39 [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Atlanta: GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Division of Human Development and Disability. (2012). Disability and Health Data System. Retrieved from https://dhds.cdc.gov

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). Introduction to Public Health|Public Health 101 Series. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/publichealth101/public-health.html [Google Scholar]

- Cieza A, & Bickenbach JE (2015). Functioning, disability and health, international classification of International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed., pp. 543–549). New York, NY: Elsevier; 10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.14081-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham WC, Hamby BW, & Oates GR (2017). The social determinants of chronic disease. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52, S5–S12. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JW, Cohen SB, & Banthin JS (2009). The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: A national information resource to support healthcare cost research and inform policy and practice. Medical Care, 47, S44–S50. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a23e3a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR, Hess DW, Hibbard MR, Layman DE, & Stewart RK (2010). Specialty practice in rehabilitation psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41, 82–88. 10.1037/a0016411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241–1299. 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo T (1964). Sensitivity of one person to another. Rehabilitation Literature, 25, 231–235. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1965-05576-001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan CH, & Dijkers M (2001). Quality of life after spinal cord injury: A qualitative study. Rehabilitation Psychology, 46, 3–27. 10.1037/0090-5550.46.1.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn DS, & Andrews EE (2015). Person-first and identity-first language: Developing psychologists’ cultural competence using disability language. American Psychologist, 70, 255–264. 10.1037/a0038636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn DS, Ehde DM, & Wegener ST (2016). The foundational principles as psychological lodestars: Theoretical inspiration and empirical direction in rehabilitation psychology. Rehabilitation Psychology, 61, 1–6. 10.1037/rep0000082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehde DM, Alschuler KN, Sullivan MD, Molton IP, Ciol MA, Bombardier CH, … Fann JR (2018). Improving the quality of depression and pain care in multiple sclerosis using collaborative care: The MS-Care trial protocol. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 64, 219–229. 10.1016/j.cct.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehde DM, Wegener ST, Williams RM, Ephraim PL, Stevenson JE, Isenberg PJ, & MacKenzie EJ (2013). Developing, testing, and sustaining rehabilitation interventions via participatory action research. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 94, S30–S42. 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott TR, & Rath JF (2012). Rehabilitation psychology In Altmaier EM & Hansen J-IC, The Oxford handbook of counseling psychology (pp. 679–702). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erwin PC, & Brownson RC (2017). Macro trends and the future of public health practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 38, 393–412. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fee E, & Gonzalez AR (2017). The history of health equity: Concept and vision. Diversity and Equality in Health and Care, 14, 148–152. 10.21767/2049-5471.1000105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fordyce WE (1984). Behavioural science and chronic pain. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 60, 865–868. 10.1136/pgmj.60.710.865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gase LN, Pennotti R, & Smith KD (2013). “Health in All Policies”: Taking stock of emerging practices to incorporate health in decision making in the United States. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 19, 529–540. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182980c6e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JE, Middleton A, Roberts P, Mallinson T, & Prvu-Bettger J (2018). Health services research in rehabilitation and disability—The time is now. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 99, 198–203. 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ, & Booth A (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26, 91–108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groomes DAG, Kampfe CM, & Mapuranga R (2011). The relationship between race and acceptance of disability when considering services through vocational rehabilitation. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 34, 57–65. 10.3233/JVR-2010-0534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gulley SP, Rasch EK, Bethell CD, Carle AC, Druss BG, Houtrow AJ, … Chan L (2018). At the intersection of chronic disease, disability and health services research: A scoping literature review. Disability and Health Journal, 11, 192–203. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BL (1981). Participatory research, popular knowledge and power: A personal reflection. Convergence, 14, 6–20. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?idEJ257461 [Google Scholar]

- Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, Gray DB, Stark S, Kisala P, … Hahn EA (2015). Environmental barriers and supports to everyday participation: A qualitative insider perspective from people with disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96, 578–588. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammel J, McDonald KE, & Frieden L (2016). Getting to inclusion: People with developmental disabilities and the Americans With Disabilities Act Participatory Action Research Consortium. Inclusion, 4, 6–15. 10.1352/2326-6988-4.1.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell E (2012). Crime against persons with disabilities, 2009–2011. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/capd0911st.pdf

- Heller J, Givens ML, Yuen TK, Gould S, Jandu MB, Bourcier E, & Choi T (2014). Advancing efforts to achieve health equity: Equity metrics for health impact assessment practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11, 11054–11064. 10.3390/ijerph111111054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard MR, Cantor J, Charatz H, Rosenthal R, Ashman T, Gundersen N, … Gartner A (2002). Peer support in the community: Initial findings of a mentoring program for individuals with traumatic brain injury and their families. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 17, 112–131. 10.1097/00001199-20020400000004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine U.S. Committee for the Study of the Future of Public Health. (1988). The future of public health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 10.17226/1091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan VBB, & Lorig K (2011). The Internet diabetes self-management workshop for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Health Promotion Practice, 12, 261–270. 10.1177/1524839909335178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RM, Chambers DA, & Glasgow RE (2014). Big data and large sample size: A cautionary note on the potential for bias. Clinical and Translational Science, 7, 342–346. 10.1111/cts.12178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch I (2013). Health in all policies. British Medical Journal, 347, f4283 10.1136/bmj.f4283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciulek JF (1999). Consumer direction in disability policy formulation and rehabilitation service delivery. Journal of Rehabilitation, 65, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Krahn GL, Walker DK, & Correa-De-Araujo R (2015). Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. American Journal of Public Health, 105, S198–S206. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston AL, Campbell MK, Fraser WD, MacLennan GS, Selby PL, & Ralston SH (2010). Randomized trial of intensive bisphosphonate treatment versus symptomatic management in Paget’s disease of bone. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 25, 20–31. 10.1359/jbmr.090709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston AL, McCallum M, Campbell MK, Robertson C, & Ralston SH (2005). An integrated approach to consumer representation and involvement in a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Clinical Trials, 2, 80–87. 10.1191/1740774505cn065oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppo K, Ollila E, Pena S, Wismar M, & Cook S (Eds.). (2013). Health in All Policies: Seizing opportunities, implementing policies. Helsinki, Finland: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, & Breshears B (2019). Discrimination at every turn: An intersectional ecological lens for rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Psychology, 64, 146–153. 10.1037/rep0000266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin K (1935). Psycho-sociological problems of a minority group. Journal of Personality, 3, 175–187. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1935.tb01996.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin K (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2, 34–46. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Livneh H (2001). Psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability: A conceptual framework. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 44, 151–160. 10.1177/003435520104400305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacLachlan M (2014). Macropsychology, policy, and global health. American Psychologist, 69, 851–863. 10.1037/a0037852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLachlan M, & Mannan H (2014). The World Report on Disability and its implications for rehabilitation psychology. Rehabilitation Psychology, 59, 117–124. 10.1037/a0036715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi E, & Meade MA (2015). Disparities in access to health care among adults with physical disabilities: Analysis of a representative national sample for a ten-year period. Disability and Health Journal, 8, 182–190. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main CJ, Keefe FJ, Jensen MP, Vlaeyen JW, & Vowles KE (2015). Fordyce’s behavioral methods for chronic pain and illness: Republished with invited commentaries. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, & Taylor S (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 372, 1661–1669. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald KE, Keys CB, & Balcazar FE (2007). Disability, race/ethnicity and gender: Themes of cultural oppression, acts of individual resistance. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 145–161. 10.1007/s10464-007-9094-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moat KA, Lavis JN, Clancy SJ, El-Jardali F, & Pantoja T (2014). Evidence briefs and deliberative dialogues: Perceptions and intentions to act on what was learnt. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 92, 20–28. 10.2471/BLT.12.116806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motl RW, Mowry EM, Ehde DM, LaRocca NG, Smith KE, Costello K, … Chiaravalloti ND (2018). Wellness and multiple sclerosis: The National MS Society establishes a Wellness Research Working Group and research priorities. Multiple Sclerosis Journal, 24, 262–267. 10.1177/1352458516687404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2009). The power of prevention: Public health challenge of the 21st century. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/pdf/2009Power-of-Prevention.pdf

- Nelson RJ, & Lund EM (2017). Bronfenbrenner’s theoretical framework adapted to women with disabilities experiencing intimate partner violence In Johnson AJ, Nelson JR, & Lund EM (Eds.), Religion, disability, and interpersonal violence (pp. 11–23). New York, NY: Springer; 10.1007/978-3-319-56901-7_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura M, Makimoto K, Kato M, Shiba T, Matsuura C, Shigenobu K, … Ikeda M (2009). Empowering older people with early dementia and family caregivers: A participatory action research study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46, 431–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obama B (2016). United States health care reform: Progress to date and next steps. Journal of the American Medical Association, 316, 525–532. 10.1001/jama.2016.9797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2015). OECD health statistics 2015. Paris, France: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, & Griffin-Blake S (2018). Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults—United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 882–887. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6732a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal GC (2011). Disability, intersectionality and deprivation: An excluded agenda. Psychology and Developing Societies, 23, 159–176. 10.1177/097133361102300202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, & Jha AK (2018). Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. Journal of the American Medical Association, 319, 1024–1039. 10.1001/jama.2018.1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack KM, Givens ML, & Tung GJ (2014). Using health impact assessments to advance the field of injury and violence prevention. Injury Prevention, 20, 145–146. 10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand M, & Harrell E (2009). National crime victimization survey: Crime against people with disabilities. Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice; Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?typbdetail&iid2022 [Google Scholar]

- Ravesloot CH, Seekins T, Cahill T, Lindgren S, Nary DE, & White G (2007). Health promotion for people with disabilities: Development and evaluation of the Living Well With a Disability program. Health Education Research, 22, 522–531. 10.1093/her/cyl114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L (2016). Incorporating intersectionality into psychology: An opportunity to promote social justice and equity. American Psychologist, 71, 474–485. 10.1037/a0040323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotch RK (2009). “Nothing about us without us”: Disability rights in America. OAH Magazine of History, 23, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Selby JV, Forsythe L, & Sox HC (2015). Stakeholder-driven comparative effectiveness research: An update from PCORI. Journal of the American Medical Association, 314, 2235–2236. 10.1001/jama.2015.15139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt SE, Batch BC, Davis LP, Dunham AA, Easterling M, Feinglos MN, … Miranda ML (2015). Methods and initial findings from the Durham Diabetes Coalition: Integrating geospatial health technology and community interventions to reduce death and disability. Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology, 2, 26–36. 10.1016/j.jcte.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]