Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide. Complex diseases with highly heterogenous disease progression among patient populations, cardiovascular diseases feature multi-factorial contributions from both genetic and environmental stressors. Despite significant effort utilizing multiple approaches from molecular biology to genome-wide association studies, the genetic landscape of cardiovascular diseases, particularly for the nonfamilial forms of heart failure, are still poorly understood. In the past decade, systems-level approaches based on omics technologies have become an important approach for the study of complex traits in large populations. These advances create opportunities to integrate genetic variation with other biological layers to identify and prioritize candidate genes, understand pathogenic pathways and elucidate gene-gene and gene-environment interactions. In this review, we will highlight some of the recent progress made using systems genetics approaches to uncover novel mechanisms and molecular bases of cardiovascular pathophysiological manifestations. The key technology and data analysis platforms necessary to implement systems genetics will be described and the current major challenges as well as future directions will also be discussed. For complex cardiovascular diseases, such as heart failure, systems genetics represents a powerful strategy to obtain mechanistic insights and to develop individualized diagnostic and therapeutic regiments, paving the way for precision cardiovascular medicine.

Keywords: Systems biology, genetics, heart diseases

Introduction

Taken together, cardiovascular diseases are the number one killer in the world, with nearly half (121.5 million) of all adults over the age of 20 in the United States showing some evidence of a cardiovascular disorder1. Like most common disorders, cardiovascular diseases exhibit complex forms of inheritance that arise out of interactions between genetic and environmental factors. Traditional genetic approaches, however, have often struggled to identify the underlying biological networks implicated in these disorders. The vast majority of research funding and publications are limited to the same 5–10% of the protein-coding genes in the genome, very few of which have contributed successfully to current clinical diagnosis and therapy2 while the remaining 90–95% are understudied with untapped potential. Clearly an approach that can harness the power of genetics and systems biology is needed to untangle the disease mechanisms and to identify new targets for diagnosis and therapies.

This review is organized into three sections. The first discusses the general design of systems genetics studies and some useful tools for data analysis. Beyond simply identifying genes contributing to complex traits, systems genetics seeks to understand the higher order interactions involved in complex traits, using approaches such as network modeling. The second section describes applications of systems genetics to cardiovascular diseases and related metabolic disorders. Here, we have attempted to provide illustrative examples rather than be comprehensive. While a major application of this approach continues to be the understanding of complex diseases, systems genetics has proven useful for examining fundamental questions such as pharmacogenetics, gene regulation networks, and signaling cross-talk between tissues. The third section highlights current challenges and potential solutions under development and discusses the prospects for a more comprehensive understanding of the genetic bases of cardiometabolic disorders.

I. Design and Implementation of a Systems Genetics Study

Systems genetics: basic concepts

The completion of human genome sequence followed by the subsequent identification of millions of common genetic variations within human populations has enabled new types of research to explore novel genes for many traits. Indeed, Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have now identified thousands of genomic loci for common diseases3 (Table 1). GWAS have also revealed that common diseases are generally highly complex, such that genetic susceptibility is linked to hundreds or perhaps thousands of small-effect variants which together predispose or protect and individual from that disease. Extracting useful insights from these findings to elucidate disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets for specific individuals is critical for the development and implementation of precision medicine for cardiovascular diseases.

Table 1.

Significant GWAS loci for different phenotypic traits or diseases as of Dec 31st, 2019

| Phenotype | Significant Loci |

|---|---|

| Blood Pressure | 3954 |

| Height | 3275 |

| Total Cholesterol | 1443 |

| T2 Diabetes | 935 |

| Arrythmia | 504 |

| Stroke | 145 |

| Hypertension | 114 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 57 |

| Heart Failure | 41 |

| Atherosclerosis | 22 |

The challenges in moving forward are considerable. Despite successes at identifying large number of genomic loci associated with many human clinical traits, relatively few of these loci have provided key insights into the underlying pathways involved due to inadequate genetic resolution or a lack of understanding regarding the basic biology of the candidate genes. Further complicating the study of cardiovascular diseases is their chronic, late onset nature. Additionally, how sex differences contribute to disease susceptibility is as yet largely unexplored. Therefore, more powerful approaches beyond genome-wide association analyses are needed to decode the genetic fabric underpinning complex cardiovascular diseases.

“Systems genetics”, also termed “integrative genetics”, is a population and systems-based approach that was developed to uncover genes and gene-environment interactions underlying complex traits (see Table 2 for the key terms in Systems Genetics studies). In contrast to a traditional GWAS approach, which is largely limited to the direct association between genetic variants and phenotypic traits, systems genetics leverages high throughput “omics” technologies, such as RNAseq or mass spectrometry-based metabolomics, to quantitate additional molecular traits (e.g. expression levels or metabolite abundances) alongside more complex clinical phenotypes. Systems genetics approaches integrate these disparate data types using correlation, co-mapping, or other modeling approaches to generate hypotheses linking genetic variants and complex traits (see illustration in Figure 1A). One major benefit of these integrative approaches is that it addresses the issue of multiple comparison testing which is pervasive in approaches such as GWAS, RNAseq or any other high-throughput technique. By integrating multiple data types together, systems genetics approaches can recover some of the results which are often discarded in single-layer approaches by bolstering their data with additional information from other biological layers.

Table 2.

Commonly used terms in systems genetics and their definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Complex Disease | A disease caused by the interaction of multiple genetic and environmental factors |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association Study: A technique where changes in a phenotype are associated with changes in the genome. Other forms, such as EWAS (epigenome-wide association study) apply the same concept to other biological layers |

| QTL | Quantitative Trait Locus: A region (locus) of the genome which is significantly associated with a phenotype. QTLs are broken down into types that represent the biological layer to which they are referring. (eg eQTL for expression, pQTL for protein abundance, miRQTL for microRNAs, etc.) |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| Cis/Trans | Sometimes called ‘local’ and ‘distant’, these terms refer to the mechanism of action between a SNP and its target in a QTL. When a SNP is affecting a gene on the same chromosome and within the same LD block, it is said to be acting in cis, while a SNP affecting the expression of a gene elsewhere on the genome (eg on another chromosome) is said to be acting in trans |

| Bisulfite Sequencing | A common means to query the methylome. Unmethylated cytosines are converted to Uracil by bisulfite treatment, resulting in a clear signature which can be detected during DNA sequencing. |

| ChIP | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation: The name for a class of approaches which determine if a given protein binds to a given region of DNA |

| 3C | Chromosome Conformation Capture: A way to examine whether two locations on the genome interact with one another in 3-d space. |

| 4C | Chromosome Conformation Capture-on-Chip: Captures interactions between one locus and the rest of the genome |

| Hi-C | Identifies all interactions between DNA in 3-d space in the genome |

| RIPseq | RNA Immunoprecipitation Sequencing: Maps which RNA sequences are bound by a given protein |

| ATACseq | Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing: An approach which identifies genome-wide chromatin accessibility |

| Polygenic Risk Score | A way to integrate the results of many QTLs together to calculate a single score which predicts the susceptibility of an individual to a disease based on their DNA. |

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of Systems Genetic Strategy,

A. for the concept and key components of a systems genetics study; B. An example of integration of mRNA expression and chromatin structure; C. An example of expression quantitative trait (eQTL) hot-spot analysis; D. An example of integrated transcriptomic gene module analysis for upstream and downstream network interactions.

Systems biology approaches often start from studying how genetic variations perturb complex clinical traits by acting through different molecular dimensions, such as gene expression, protein-protein interactions or metabolic modulations. By querying these individual, simpler traits as a function of genetic variation across a population, one can uncover the ways in which molecular phenotypes affect clinical phenotypes and disentangle complex clinical traits into interrelated component parts4,5. Therefore, systems genetics findings go beyond simple associative relationships between individual genes and traits, and are able to offer molecular insights into the mechanistic paths involved in the onset and progression of diseases.

The application of systems genetics is rapidly evolving alongside its core methods, resulting in a versatile, dynamic and continually improving set of analytical tools. Systems genetics is often used as a follow-up approach to further interrogate the results from GWAS. Most human GWAS loci contain multiple candidate genes and significant interest lies in the prioritization of these candidates to determine which is most likely to be identified as the causal gene in downstream analyses. To accomplish this aim, one can, for example, integrate gene expression data obtained from a relevant tissue across the same (or a similar) population to the GWAS cohort and ask whether the targeted genetic variations (such as a set of single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs) that affect the clinical traits also perturb the expression or function of one of the genes in the locus. Loci affecting gene expression are termed expression Quantitative Trait Loci, or eQTL6–8, and genetic variants with strongest effects on gene expression often reside in close proximity to the target genes and are termed cis-eQTLs. In this case, a gene with a strong cis-eQTL within the GWAS locus should be prioritized as a causal gene candidate within the locus for the specific clinical trait.

Figure 1A shows the various biologic layers that can be subjected to systems genetics analyses. The arrows indicate the flow of information between layers that have been examined in several studies, shown as examples in Figure 1B–D. The most straightforward method employed to understand the relationships between the elements of different biologic layers, or within a biologic layer, is correlation. For example, Figure 1B shows correlation at a locus for a SNP, gene expression, and DNA accessibility, suggesting that they may be causally linked, although correlation can also be observed due to artifacts such as batch effects. Another important method, as described briefly above, is mapping traits from different layers (such as a clinical trait and a transcript level trait) to the same genetic locus given enough statistical power to make these connections at each layer. For example, Figure 1C shows that various metabolic syndrome traits and expression of the KLF14 transcription factor all map to the KLF14 gene locus9. A third approach involves using statistical modeling to integrate biological layers. Many different methods have been developed for applications such as causal modeling, pathway enrichment and network modeling. For example, Figure 1D shows the integration of multiple biologic layers to predict upstream and downstream regulators of key genes within a transcriptomic network. Systems genetics studies using populations of model organisms such as rats, mice, flies, or yeast have proven to be particularly useful for examining the overall architecture of complex traits, including topics such as gene-by-gene and gene-by environment interactions. Studies with model organisms have the important advantage that it is possible to control environmental factors and other sources of heterogeneity such as differences in age. Also, studies of model organisms allow easy access to relevant tissues, something generally not possible in human studies.

Currently, the prevailing approach employed by most biologists is “reductionistic” in nature, which involves one-dimensional experimental tests of causality. For example, genes suspected in human diseases can be individually perturbed in experimental models such as cultured cells, genetically modified mice or other model organisms. The resulting phenotypes are evaluated, frequently under simple gain- and loss-of-function conditions, for relevance to the diseases and assessed as to whether or not the gene in question is necessary and sufficient to lead to or exacerbate a disease state. Systems genetics approaches take a different route to establish such relevance based on the relationship between the genetic variants and the multi-dimensional functional outcome. Although these two approaches differ in methodology and scientific rationale, they can be highly complementary and supportive to each other. For scientists using reductionistic approaches, data generated from systems genetics studies can serve as a valuable resource for developing new hypotheses and identifying novel links between their favorite genes and pathways with specific phenotypic traits. As discussed below, systems genetics approaches, making use of natural variation, are relatively unbiased in contrast to purely reductionistic studies that, by necessity, rely on researchers to make decisions on which genes to study and how to build working models. This is especially relevant now since data derived from many systems genetics studies, involving both humans and model organisms, are readily available with public access and interrogations and increasingly sophisticated tools have been developed to use such data to identify disease-associated pathways and complex interactions.

The overarching goal of systems genetics for complex disease traits is to integrate different layers of information, from genetic variants to transcriptomic and other molecular features, to the ultimate phenotypic traits in order to identify cross-layer connections and elucidate disease causing pathways. For example, a complex disease such as type II diabetes can be viewed as the inability of the body to properly regulate glucose. It is possible to identify candidate polymorphisms, transcripts, proteins and metabolites that predispose or protect individuals to diabetes by simple correlative analysis between diseased and healthy individuals. These isolated analyses, however, only reveal part of the complexity without the full understanding of inter-layer interactions and thus offer limited mechanistic insights for the pathogenesis and progression of the disease. Integrating and establishing the interconnections between these layers, multi-layer pathways may be established to offer more predictive models and better mechanistic understanding of disease manifestations, such as a regulatory network for insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells, or the action of insulin on different tissues such as the vasculature, muscle, liver, and fat. Consequently, systems genetics approaches seek to examine these cellular and physiological processes at different layers, each simpler in etiology than the eventual disease traits with a goal of understanding the complex whole through its simpler parts. Therefore, there are two key components in the implementation of a systems genetics study: one is dataset acquisition and annotation and the other is dataset integration and analysis.

Data Acquisition and Annotation from Individual Biological Layers.

Before a systems genetics study can be performed, data must be collected from the desired biological layers, often using high-throughput platforms. These layer-specific data acquisition platforms are discussed below with key representative analytic toolsets listed in Figure 2.

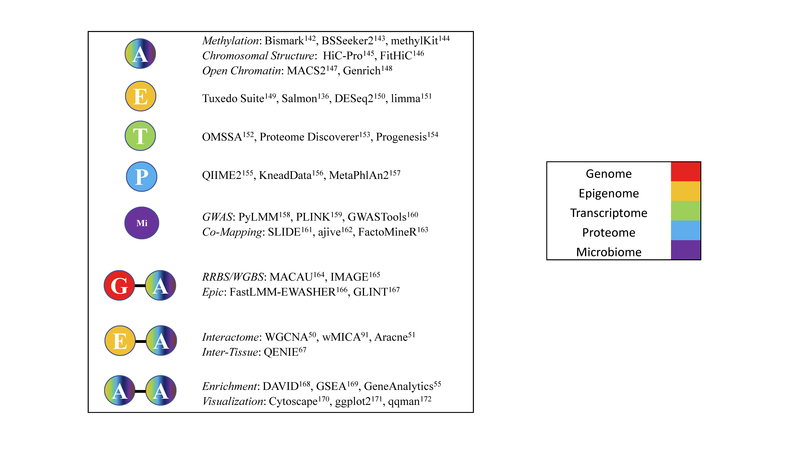

Figure 2. Analysis Tools Used at Different Biological Layers.

Example bioinformatic algorithms used to analyze data at different biological layers. G is genome, E is Epigenome, T is Transcriptome, P is Proteome, Mi is Microbiome, and A is any biological layer.

The genomic layer is the foundational layer on which most studies rely. Associations between DNA polymorphisms and phenotypes have led to the identification of large number of possible disease causing genes10 through GWAS as well as helped us disentangle cause and effect between environmental factors and phenotypes using Mendelian Randomization11. High-resolution genotyping can benefit systems studies at every layer of biology. Due to the principle of co-mapping, described in greater detail below, if one polymorphism is linked to different phenotypic and molecular traits from multiple layers, it provides valuable insights to not only the genes implicated but the pathways linking the genes to the diseases. Methodology for profiling the genomic layer is well established. Genetic variations are typically queried using SNP genotyping arrays, which represent a cost-effective and high-throughput means of gathering information about common variations between individuals in a population, although certain common variations such as copy number variations cannot be efficiently detected in this way. A typical human SNP array can directly identify about one million polymorphisms which, through linkage disequilibrium, can be used to impute several million additional SNPs and recover a large percentage of the total predicted variation in a population, although this can be affected by population structure, and rare variants remain challenging to impute in most populations. Similar arrays are available for model organisms12.

Epigenomics is often referred to as the functional state of the genome and consists of non-sequence modifications to DNA and chromatin such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, nuclease accessibility, and chromatin architecture. There has been a recent explosion of interest in the epigenome due to the rapidly expanding scope of the so-called histone-code, its increasingly appreciated role in gene regulation as well as its malleability in response to external and/or environmental influences13. A set of tailored techniques is required to profile the epigenomic landscape. For example, DNA methylation is often queried using either whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) or its cheaper alternatives, reduced representational bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) or the Infinium MethylationEpic array14,15. The main tradeoff between these techniques is in completeness versus cost. WGBS, by far the more expensive technique, recovers the methylation status of over 25 million CpGs, while RRBS and the Epic array focus on a smaller subset of CpG sites enriched for locations of interest either through enzyme digestion and size selection (RRBS) or manual curation (Epic). Other genome-wide techniques include ATACseq16 and DNAse I hypersensitivity mapping17, both means of identifying regions of the genome with open chromatin that are thought to be transcriptionally active. The targeted epigenomic modifications can be profiled using specific Chromatin Immuno-precipitation (ChIP)-sequencing. For higher levels of chromatin organization, genome wide profiling can be achieved using a chromosome conformation capture protocol such as 4C-sequencing or HI-C sequencing. Although critically important at a conceptual level, implementing this scale of analysis across a large population for systems genetics study is a very challenging endeavor. Although genome-wide DNA methylation assays are both reliable and well-established, the unit cost is still quite high due to the depth of sequencing coverage required. In contrast, profiling for chromatin modification and genome architecture is both technically challenging and highly dependent upon the quality of the specific reagents, adding experimental variations to the dataset. Finally, epigenomic features are inherently cell-type specific and whole tissue profiling represents the composite results from different types of cells, and special care needs to be taken to attempt to account for cell-type composition when analyzing the results.

Beyond genetics and epigenetics is the transcriptome, which is frequently used to identify pathways driving and/or affected by a genetic mutation, an environmental stimulus, or a disease state. Affected by genomic variation and closely regulated by epigenetic changes, gene expression data are incredibly valuable on their own even before they are integrated with other biological layers. Transcript levels were traditionally measured using expression arrays but are now frequently obtained through total RNA sequencing. Sequencing-based approaches have the advantage of a greater dynamic range and the ability to capture the entire transcriptomic landscape within the sample, allowing researchers to recover novel genes, isoforms or low-abundance transcripts frequently omitted from designed microarrays. Similar to epigenetic profiling, transcriptomic profiling is highly cell-type specific and current approaches to whole tissue RNA sequencing or array analysis have limitations regarding possible cell type heterogeneity and each cell’s specific contributions to transcriptomic variation among the individuals in a population.

The next biological layer, proteomics, concerns the products of mRNA translation. Proteomic databases consist of abundances, localizations, post-translational modifications and interacting partners, adding more evidence of biological pathways which affect and are altered by diseases. Crucially, this layer often needs to be separately examined from the transcriptome as several studies have now comprehensively examined the relationships between the levels of transcripts and the levels of the proteins they encode as a function of genetic variation18–20 and report surprising little correlation between transcript levels and protein levels (R–0.3). This discordancy probably has many causes, including protein stabilities and protein-protein interactions; for example, the levels of one subunit of a heterodimer are limited by the levels of a second subunit, and any subunit that is in excess will likely undergo rapid degradation. Many proteome assays rely on high-throughput mass spectrometry18, with quantitative proteomics frequently employing techniques such as Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC) to provide consistent protein quantification across many different samples21. Advances in the SILAC technology have allowed for use of the technique in model organisms22 Assays also exist to explore physical interactions between proteins on a global scale to understand how, where, and with which other proteins they function23. The Pulse-Chase approach allows researchers to explore the temporality of protein translation and abundance in response to a stimulus or a genetic perturbance24. Numerous approaches also exist to connect this layer of biology to other layers, such as ChIP-seq, which identifies locations of the genome where a known protein interacts with DNA or RIP-seq, which examines RNA-Protein complexes.

Additional biological layers between the genome and phenotypic traits of interest are broadly compressed into the ‘metabolome’, a catch-all and rapidly expanding dimension in systems biology which includes everything from tissue composition to circulating ions to hormones and other small molecule signals to classically defined metabolites. Many of these parameters are routinely measured from patients as well as healthy populations, or experimental cohorts using well established biochemical assays. A wealth of information is already available linking them to disease states, such as glucose and insulin with diabetes or cholesterol with cardiovascular risk.

As our appreciation for biological complexity continues to grow, the relevant layers of systems genetics will evolve as well. Indeed, recent discoveries in co-habiting microbiomes in humans open a new biological dimension in systems genetics. The microbiome, consisting of hundreds of species of bacteria as well as fungi and viruses, are directly affected by dietary changes and host-immune responses, and they in turn influence various physiologic functions, including susceptibility to various diseases. It is clear that the gut microbiome contributes substantially to the overall metabolic regulation of the host25, thus playing important roles in many human diseases, including cardio-metabolic disorders26. It also appears that host genetics can influence the composition of the microbiome, with a high heritability in animal models maintained under a controlled environment27 and modest heritability in human populations28. The microbiome is often queried using genomic DNA sequencing of, among other sources, fecal matter to identify the species present within an individual.

Integration of Biological Layers Using Systems Genetics Techniques

After data from individual biological layers are collected, systems biology techniques will be needed to integrate these layers in order to generate hypotheses and reveal insights about biological questions (see Figure 2). Nearly every quantitative outcome derived from the high-throughput techniques described above can be directly related to the polymorphisms present in the genome based on the same principle of genome-wide association analysis for a particular phenotype. The resulting quantitative trait loci (QTLs) can be further examined for mechanistic insight. Different biological layers’ associations with the genome are typically referred to as different sub-types of QTLs: meQTLs for methylation, xQTLs for other epigenetic markers, eQTL for gene expression, miRQTLs for microRNAs, sQTL for splicing, pQTLs for protein, mQTL for metabolites and cQTLs for clinical traits/phenotypes. These association is not limited to genomic variants. In principle, other variants from different layers of biology can be used as a basis for association analysis. For example, using DNA methylation as a basis leads to newer approaches such as Epigenome Wide Association studies (EWAS)29.

Taken individually, each significant QTL provides its own testable hypothesis, yet the power of systems genetics is more evident when multiple types of QTLs are combined. These approaches are typically part of an iterative process, where a model of disease is constructed piece by piece either through combinatorial testing across different biological layers, or through more sophisticated computational tools. Systems geneticists frequently rely on optimization algorithms to identify the most likely set of parameters drawn from multiple biological layers which results in the observed phenotypes30,31, or on predictive models such as Marcov Chain Monte Carlo methods, which fit experimental data to stochastically varying equations32.

One example of an approach that combines multiple forms of QTL is a study by Zhang et al33 in which eQTLs and cQTLs were integrated to identify genes located within atrial fibrillation loci. This approach is a form of an approach sometimes called a Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS)34 and is an example of co-mapping, in which a single polymorphism or locus is tied to multiple biological layers, generating hypotheses as to how an individual SNP acts through the associated molecular phenotypes to affect the trait of interest (see, for example, Teslovich et al35 and Soldner et al36). Similar approaches have used DNA methylation as the molecular phenotype instead of transcription or as an anchor in place of DNA variation to identify regions of the genome where differential methylation might affect diabetes risk37 or other phenotypes38–40. Analogous methods have been proposed and utilized for the proteomic41,42, metabolomic43 and microbiome44–46 biological layers. Small et al9 identified a transcription factor, KLF14, which was a TWAS hit for loci involved in diabetes and HDL. They further identified the KLF14 locus as a ‘master regulator locus’ which significantly affected the expression of many adipose genes. This latter approach, sometimes called ‘hotspot analysis’, limits itself to a single type of QTL to identify individual polymorphisms which have a statistically significant effect on a large number of molecular phenotypes, indicating genes which might be fruitful targets for later investigations. A related concept is the Phenome-wide Association Study (a PheWAS), in which the concept of GWAS is turned on its head and a single polymorphism is tested for association with a large number of individual traits47.

Not all types of layer-wide data are appropriate for QTL mapping, which requires the high-throughput analysis of numerous individuals. For example, Hi-C, a method which examines the genome-wide physical conformation of DNA in 3-d space, cannot be easily used on the number of individuals necessary to generate QTLs. These data, however, can still be incorporated with association data for other types of molecular phenotypes. For example, using an approach called Capture Hi-C, Baxter et al48 looked at the physical interactions between 100 breast cancer SNPs and nearby regions of DNA and identified likely candidate genes at 33 of these loci, confirming their results either with eQTLs or through survival curves for individuals with high, intermediate or low expression of the identified candidate loci. The Encode Project49, available in both human and multiple animal models, has examined dozens of epigenetic marks in numerous cell types, providing information on open and closed chromatin regions, likely locations of enhancer elements and transcription-factor binding sites. Any of these marks can be used to refine and improve upon GWAS results and generate hypotheses as to the cell type and gene affected by the associated polymorphism. Other approaches, such as ATACseq16 can be used to identify which genes near a given SNP are likely to be tied to a phenotype of interest based on regional accessibility to the DNA.

The interaction of elements within the same biological level, especially the transcriptome and proteome are often called the interactome. The interactome can be used to place novel genes found via GWAS or other means into biological contexts. Historically, the interactome was often explored in a piecemeal fashion, each link constructed as a result of an individual experiment querying whether one protein was physically linked to another protein via co-immunoprecipitation assays. The development of the microarray and high-throughput transcriptomics allowed for unbiased, data-driven co-expression network methods to be developed (e.g. Langfelter & Horvath50, Margolin et al51, or Rau et al52) in which data across a population was leveraged to identify genes whose expression levels are correlated to one another. Utilizing concepts from graph theory, these genes and the links between them can then be prioritized for further study. There are three common approaches to establish interactomes: the identification of ‘hub’ genes, the identification of gene ‘modules,’ and the identification of ‘connector’ genes. ‘Hub’ genes are defined as genes that are highly correlated to a large number of other genes or transcripts. Special priority is placed on hub genes located near known phenotype-associated genes, with the hypothesis that these hub genes are playing an important role in the phenotype53,54. Transcriptional gene modules are groups of genes with a shared expression pattern distinct from other sets of genes across the population. These modules can be examined for enrichment for genes with particular functions with tools such as GeneAnalytics55 and correlated with phenotypes of interest, thus linking molecular pathways and cellular processes with a specific phenotype. Gene modules are also particularly useful for suggesting roles for genes with previously unknown functions: if a novel transcript is highly correlated with many genes from a given gene family, it is likely that this gene may have a related role53,56,57. Finally, ‘connector’ genes are genes which connect gene modules to one another and can be identified by looking for genes with high Centrality, a measurement of the fraction of shortest paths between any pair of transcripts within a network which pass through a gene of interest. These transcripts frequently play important roles in disease58,59 and are useful targets for drug development due to their role in connecting pathways to one another60. Modern protein-protein interaction networks are constructed through a variety of high-throughput approaches61 that prioritize physical interaction over correlated abundances. Once constructed, however, the same graph theory principles hold, allowing researchers to identify hubs, modules and connectors in the protein interactome. These approaches are also valid for any other biological layer in which high-throughput data can be meaningfully linked through correlation, physical interaction or other means, such as the metabolome62,63. Finally, using both epigenetic and transcriptomic data allows a researcher to construct a transcription-factor-centric network, in which ChIP-seq data on transcription factors are combined with gene expression information to refine network structure around key genes known to regulate the expression of other transcripts64–66.

It is also possible for systems genetics approaches to study differences which arise between different tissues. Although the genomic layer remains functionally identical in each cell of an organism, changes in other biological layers, notably the epigenome, result in the differentiation of different cell types from one another. Individual tissues and cell types may have radically different patterns of gene expression, protein regulation and play different roles in phenotypic development, resulting in differences in QTLs, interaction networks and other systems genetics results from tissue to tissue. Although systems genetics requires a tissue-specific context, this fact can also be leveraged to discover inter-tissue communication and uncover their synergistic or interdependent contributions to disease. Seldin et al67 developed a statistical approach to identify novel tissue-tissue circuits using expression data from multiple tissues of a mouse population. By identifying secreted proteins in one tissue with strong correlation to transcription and enriched pathways in a second tissue, they find adipose-derived Lipocalin-5 is able to enhance skeletal muscle mitochondrial function and insulin sensitivity, and liver-secreted Notum can promote browning of white adipose tissue in the context of obesity and diabetes. Such inter-tissue communication becomes evident only when the results from systems genetics derived from different biological layers are integrated67. Similar approaches could potentially be developed to identify crosstalk mediated by circulating miRNAs or exosomes68.

Systems genetics resources and availability

In the prior sections, we have laid out a variety of concepts by which researchers can integrate biological layers with one another to study their phenotypic trait of interest. In many cases, the data necessary to begin these analyses are already available in online databases. For example, many journals now mandate the depositing of sequence data (DNA, RNA, ATAC, etc.) into online repositories such as the sequence read archive (SRA: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) which currently has over 1.5 million archived datasets from human cells and/or tissues, or the gene expression omnibus (GEO: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), which is focused on gene expression through either microarray or RNAseq approaches and currently contains expression data on nearly 1.8 million human samples or the database for genes and phenotypes (DbGaP: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap/) which holds phenotypic information for over 325 thousand individual phenotypes. It is highly likely that for any given phenotype a researcher is studying there are at least a few datasets available in one of these repositories or ones similar to them that would directly aid in hypothesis generation or in helping to solve a research question. Researchers have developed a number of tools and online resources to help navigate the massive amount of available information. A summary of some of these tools (Figure 2) and data resources (Table 3) are provided.

Table 3. Representative resources for Systems Genetics studies.

| Type | Resource Name | G | E | T | Pr | Me | Mi | Ph | Q | I | Description | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repository | Array Express | X | X | X | X | Large repository of systems genetics data across multiple layers | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/ | |||||

| Repository | BioGrid | X | X | X | Interaction data from genetic and proteomic studies | https://thebiogrid.org/ | ||||||

| Repository | Database of Interacting Proteins | X | X | Large repository of protein-protein interactions | https://dip.doe-mbi.ucla.edu/dip/Main.cgi | |||||||

| Repository | dbGaP | X | X | X | Large repository for raw GWAS data for human studies | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap/ | ||||||

| Repository | EBI GWAS Catalog | X | Large repository of published GWAS studies in humans | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/ | ||||||||

| Repository | Encode Project | X | X | Repository of information on epigenetic marks | https://www.encodeproject.org/ | |||||||

| Repository | Epigenomics Roadmap Project | X | X | Human epigenomic information in multiple tissues and diseases | http://www.roadmapepigenomics.org/ | |||||||

| Repository | European Genome-Phenome Archive | X | X | X | X | X | Repository of human systems genetics data | https://ega-archive.org/ | ||||

| Repository | Framingham Heart Study | X | X | X | X | A cardiovascular disease study active since 1948 | https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/ | |||||

| Repository | GEO | X | X | X | X | Large repository for multiple biological layers, but mostly pertaining to the transcriptome | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ | |||||

| Repository | GWAS Central | X | Repository for genetic association studies | https://gwascentral.org | ||||||||

| Repository | Harvard Personal Genome Project | X | X | X | Multi-layer data from volunteers | https://pgp.med.harvard.edu/ | ||||||

| Repository | Human Metabolome Database | X | Repository for metabolites in disease and healthy states | http://www.hmdb.ca/ | ||||||||

| Repository | IntAct Database | X | X | Large repository of protein-protein interactions | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/ | |||||||

| Repository | Japanese Genotype-Phenotype Archive | X | X | X | Repository of human systems genetics data from Japan | https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/jga/index-e.html | ||||||

| Repository | Metabolic Syndrome in Men Study (Metsim) | X | X | X | X | X | X | A comprehensive systems genetics study for metabolic syndrome and related disorders | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000743.v1.p1 | |||

| Repository | MetaboLights | X | Large metabolite repository | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/ | ||||||||

| Repository | MicrobiomeDB | X | Repository for microbiome data from multiple species | https://microbiomedb.org/mbio/app/ | ||||||||

| Repository | Pride Archive | X | A proteomics data repository from EBI | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/ | ||||||||

| Repository | SRA | X | X | X | X | A large repository of sequence data from multiple layers | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra | |||||

| Repository | Twin UK | X | X | X | X | X | Large twin registry with over 14,000 individuals | https://twinsuk.ac.uk | ||||

| Repository | UK Biobank | X | X | X | X | National health resource following 500,000 individuals | https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/ | |||||

| Data Curator | Collaborative Cross Resource | X | X | A mouse systems genetics resource | http://csbio.unc.edu/CCstatus/index.py | |||||||

| Data Curator | GeneWeaver | X | X | Aggregator of transcriptome data and positional candidate genes for many species and phenotypes of interest | https://geneweaver.org | |||||||

| Data Curator | GTEx | X | X | X | X | Large repository for tissue expression across 54 tissues and over 1000 individuals | https://gtexportal.org/home/ | |||||

| Data Curator | HMDP Liver EWAS Database | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | A comprehensive systems genetics resource focused on EWAS results from the liver in the HMDP | http://ewas.mcdb.ucla.edu/ | ||

| Data Curator | MassIVE | X | A repository and analysis tool for mass spectrometry data | https://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/static/massive.jsp | ||||||||

| Data Curator | Mouse Genome Informatics | X | X | X | X | Large database for mouse systems genetics data | http://www.informatics.jax.org/ | |||||

| Data Curator | NIH Human Microbiome Project | X | Microbiome data from multiple individuals | https://hmpdacc.org/ | ||||||||

| Data Curator | Omics Discovery Index | X | X | X | X | X | Aggregator for many layers of systems genetics data | https://www.omicsdi.org/ | ||||

| Data Curator | Rat Genome Database | X | X | X | X | Large database for rat systems genetics data | https://rgd.mcw.edu/ | |||||

| Data Curator | UCLA Systems Genetics Resource | X | X | X | X | Database containing information from the HMDP systems genetics resource as well as some human data | https://systems.genetics.ucla.edu/ | |||||

| Links | Curated Multi-omics Algorithms | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Continually updated list of current Multi-omics algorithms | https://github.com/mikelove/awesome-multi-omics | |

| Links | Curated Single Cell Algorithms | X | X | X | Continually updated list of current single cell algorithms | https://github.com/seandavi/awesome-single-cell | ||||||

| Links | Epigenie Epigenomics Links | X | Very large list of useful epigenomics links | https://epigenie.com/epigenetic-tools-and-databases/ | ||||||||

| Links | Metabolomics Society Links | X | Links on metabolomics | http://metabolomicssociety.org/resources/metabolomics-databases | ||||||||

| Links | Metabolomix EWAS Links | X | X | X | Links to EWAS studies | http://www.metabolomix.com/a-table-of-all-published-ewas-with-deep-molecular-phenotypes-omics/ | ||||||

| Links | Metabolomix glycomics QTL Links | X | X | X | X | Links to glycomics QTL studies | http://www.metabolomix.com/a-table-of-all-published-gwas-with-glycomics/ | |||||

| Links | Metabolomix meQTL Links | X | X | X | X | Links to meQTL studies | http://www.metabolomix.com/a-table-of-all-published-gwas-with-dna-methylation/ | |||||

| Links | Metabolomix mQTL Links | X | X | X | X | Links to mQTL studies | http://www.metabolomix.com/list-of-all-published-gwas-with-metabolomics/ | |||||

| Links | Metabolomix pQTL Links | X | X | X | X | Links to pQTL studies | http://www.metabolomix.com/a-table-of-all-published-gwas-with-proteomics/ | |||||

G, Genome; E, Epigenome; T, Transcriptome; Pr, Proteome; Me, Methylation; Mi, Microbiome; Ph, Phenome; Q, Quantitative Traits; I, Interactome.

II. Systems Genetics and Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease encompasses disorders of the vasculature and heart, and is the leading cause of death worldwide69. Although driven by common environmental risk factors, cardiovascular disease can take on many forms, each disease influencing distinct sets of cells and acting through largely distinct sets of genes. Due to this diversity, there have been an abundance of systems genetics studies designed to identify changes to genes and pathways which predispose or protect individuals from a cardiovascular disorder. In this section, we highlight a number of examples which touch upon the types of systems genetics studies we identified above.

GWAS and Beyond for Hypertension, Cardiac Hypertrophy and other Cardiac Disease Traits:

Evangelou et al70 examined over a million individuals for genetic variations associated with hypertension, which was linked to an estimated 7.8 million deaths just in 201571. The authors combined data from four different published cohorts of European descent: The UK Biobank (UKB), the International Consortium of Blood Pressure (ICBP), the US Millions Veteran Program (MVP) and the Estonian Genome Center (EGC) Biobank. Using a two-stage analysis in which suggestive loci from a combined meta-analysis of the UKB and ICBP were validated in the MVP and EGC, the authors identified 325 novel loci regulating blood pressure which passed a 5e-8 significance threshold in the first analysis, a p < 0.01 threshold in the replication analysis, and which had a concordant direction of effect in which the SNP in each cohort was affecting the phenotype in the same direction. They additionally identified 210 novel loci from a single-stage analysis designed to reduce false negatives by examining only the UKB and ICBP data but which passed a more stringent (5e-9) initial threshold and passed p <0.01 thresholds in both the UKB and ICBP data independently. Along with 366 previously reported loci, these 901 blood pressure associated loci account for 23% of all previously reported loci for this phenotype on the EBI GWAS catalog.

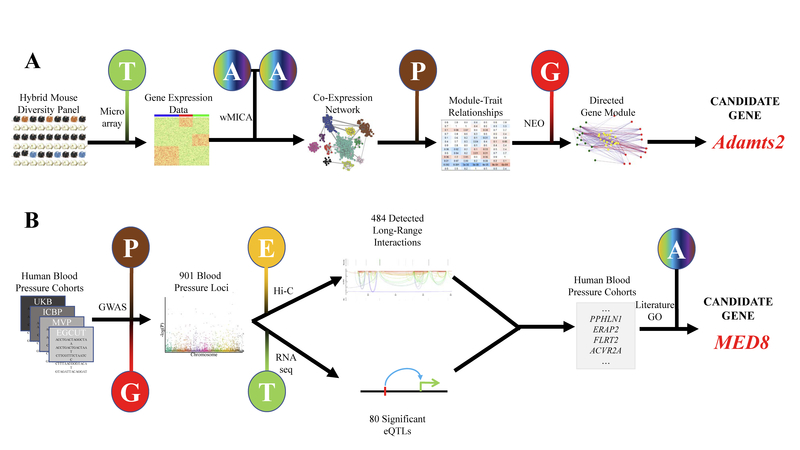

The authors followed up this GWAS approach by combining their data with other biological layers. First, they used chromatin interaction Hi-C data from five distinct cell types to identify genes which showed evidence of physical interaction with their loci (illustrated in Figure 3). Long-range interactions were identified in 484 of the 535 novel loci. Using transcriptomic datasets, the authors identified 60 novel loci with eQTLs in arterial and 20 novel loci with eQTLs in adrenal tissue. Using physical proximity as determined by Hi-C and regulatory potential as determined by eQTL analyses, the authors identified a total of 37 genes as potentially being implicated in blood pressure regulation.

Figure 3. Showcases of Systems Genetics Study for Cardiovascular Traits.

A) Rau et al 91 performed a systems genetics analysis of genes involved in heart failure by first gathering multiple layers of information from the Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel, then applying the wMICA algorithm to identify gene modules of interest before incorporating genotype data to identify important candidate genes using the Network Edge Orientation algorithm.173 B) Evangelou et al70 used four human cohorts to identify hundreds of genome-wide significant loci pertaining to high blood pressure, then utilized transcriptomic and epigenomic information to identify and prioritize candidate genes. G is Genome, E is Epigenome, T is Transcriptome, Ph is Phenome and A is Any biological layer.

In a pair of studies using the Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel (HMDP) to study cardiac hypertrophy72, 73 (showcased also in Figure 3), Rau, Wang and colleagues examined the effects of chronic β-adrenergic stimulation on heart failure across over 100 inbred mouse strains. The authors broke apart heart failure into component sub-phenotypes and monitored the progression of cardiac hypertrophy and contractile using echocardiography, histology and morphometric analysis. The authors identified 10 loci implicated in changes in heart mass, 7 loci implicated in changes in fluid retention as commonly seen in heart failure, 8 loci involved in cardiac fibrosis and 17 loci associated with systolic and diastolic echocardiographic parameters. Additional information derived from the sequencing efforts of the Welcome Trust Mouse Genomes Project74 and eQTL data were used to identify candidate genes in all but one locus. Subsequent follow-up in in vitro and in vivo models validated the roles of Adamts2, Myh14 in the regulation of left ventricular hypertrophy and dilation, and Abcc6 in cardiac fibrosis. In both cases, integrating additional biological layers, in the forms of chromatin structure and gene expression, help to extend the GWAS results to identify candidate genes linked with specific phenotypic traits.

Zhang et al33 utilized expression data from seven distinct tissues, combined with GWAS results from a large cohort of patients with atrial fibrillation to perform a TWAS analysis to identify genes contributing to atrial fibrillation. They identified a number of candidate genes enriched for actin binding and the ECM. In a similar approach, von Scheidt and colleagues75 integrated data from human GWAS studies, mouse and human gene expression profiling, and reductionistic studies in mice to identify and compare pathways contributing to atherosclerosis. In an earlier study, Petretto et al surveyed a panel of recombinant inbred rats for cardiac functions, such as left ventricular (LV) mass 76 . This panel (BXH/HXB) provided a broad range of genetic susceptibility to cardiovascular diseases and phenotype, including significant variation in LV size. Genetic loci regulating LV mass were further narrowed by combining linkage association with global expression arrays in the heart. From these studies, osteoglycin was prioritized as a cis-eQTL gene co-mapped and correlated to LV mass. Finally, Nikpay and colleagues77 utilized genotypes from the 1000 genomes project78 to identify loci which affect circulating miRNAs in 710 individuals. They found at least one genome-wide significant association in 143 circulating miRNAs. These loci were then overlapped with GWAS information to identify miRNA-regulating loci which also affect cardiovascular phenotypes. From these candidates, the authors identified several key miRNAs which may play a role in the regulation of cardiovascular disease, such as miR-1908–5p, which shares a locus with LDL, total cholesterol, fasting glucose, HbA1c and a number of lipid metabolites.

EWAS in dissection of cardiovascular diseases

Heart failure is a leading cause of hospitalization in patients over 65 in the developed countries and a disorder which has resisted GWAS approaches in the past79. Meder and colleagues14 utilized changes in DNA methylation to dissect heart failure, and they utilized 41 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and 62 control individuals to perform an initial screen for phenotype-associated CpGs through EWAS, following up with two replication cohorts containing 27 and 82 diseased and 36 and 109 control patients respectively. Utilizing the Infinium Human Methylation 450 chip on cardiac tissue samples, the authors identified 59 loci which passed multiple comparison testing. 27 CpGs associated with dilated cardiomyopathy were validated in two replication cohorts. The authors identified four transcription factor motifs which were significantly associated with these differentially methylated regions, three of which (Smad2, Smad4, and Bmal1) were previously known to be involved in heart failure. Finally, they used a cross-tissue approach to identify EWAS loci in peripheral blood that overlapped with the loci found in the heart. Unexpectedly, a significant overlap (P=3.2E-13) was observed between the two tissues, suggesting that peripheral blood methylation can act as a biomarker for changes to the cardiac methylome associated with heart failure.

Orozco et al40, working with a large mouse population, the Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel (HMDP), studied the effects of changes in CpG methylation on plasma lipid traits as well as atherosclerosis, obesity and other phenotypes for a total of 68 clinical traits. They further obtained transcriptome, proteome and metabolomic information from liver and plasma tissue for a multi-omics study. EWAS was performed on RRBS data from each biological layer, and hundreds to thousands of loci recovered at each layer. These EWAS results were compared to earlier GWAS results from the same HMDP cohort80 and a significant overlap was observed between the two studies for many molecular traits, for instance 77% overlap between two groups of cis-eQTLs identified in EWAS and GWAS. However, in keeping with the broader observations about complex disease traits, only 15% overlap was observed between the two groups of clinical trait QTLs identified in EWAS and GWAS. They then performed GWAS on each variable CpG and identified trans-meQTL hotspots, including a locus on chromosome 13 which significantly affected hundreds of CpGs. Methionine synthase reductase (Mtrr), a gene within that locus was experimentally validated as an upstream regulator for DNA methylation at the associated CpGs. These datasets are now available for exploration at each biological layer via an online platform: ewas.mcdb.ucla.edu. Finally, using a similar approach, Xie and colleagues81 examined lipid levels and their association with the methylome in 211 individuals from the STANISLAS Family study and identified two sites near the genes PRKAG2 and KREMEN2 with significant associations with lipidomic profiles.

Proteome and pQTL studies in cardiovascular diseases

Benson and colleagues42, using data from the Framingham Heart Study, performed detailed pQTL and exome analyses on the abundances of 156 proteins previously associated82 with the Framingham cardiovascular disease risk score. A discovery screen was performed in 759 individuals from the FHS Offspring cohort followed by a replication screen in the Malmö Diet and Cancer study. A total of 120 locus-protein associations were identified covering 54% (85) of the proteins of interest. Only 12 of these associations were linked to a nonsynonymous mutation in the gene through exome sequencing, a result which further confirms that the majority of polymorphisms which affected transcript/protein abundance act on non-coding regulatory regions rather than the protein-coding sequence itself, although it should be kept in mind that most databases survey healthy tissues and regulatory regions may shift position in a disease state. The authors identified one association at rs1728918 which was located within a locus associated with circulating cholesterol levels and was significantly associated with five proteins of interest. PPM1G, a nuclear phosphatase, was identified as a likely candidate gene, with subsequent in vitro experimentation validating its role in the regulation of ApoE expression.

Using six genetically distinct strains of mice, Lau et al83 combined proteomics data with transcriptomics data to better understand how the proteome is altered during pathological cardiac hypertrophy. The authors used deuterium to label newly translated proteins at two-day intervals after induction of cardiac hypertrophy by implantation of an osmotic micropump filled with the synthetic β−adrenergic agonist isoproterenol. By examining labeled vs unlabeled proteins, the authors were able to detect signatures of new protein translation, identifying 273 proteins implicated in cardiac hypertrophy, including several proteins with post-translational modifications only observed after isoproterenol administration.

Integration across multiple biological layers:

Genome-wide chromatin capture in the form of Hi-C has been used to explore the role of changes in DNA structure to the progression of heart failure as demonstrated by Rosa-Garrido et al84. Montefiori and colleagues85 performed promoter capture Hi-C (PCHi-C) in human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derived cardiomyocytes to identify interactions more likely to be involved in the regulation of gene expression. The authors noted that the majority of documented cardiovascular disease associated SNPs lie between genes. Furthermore, the majority of validated GWAS loci do not act through changes to protein structure or sequence. Accordingly, they set out to identify which genes’ promoters were associated with 524 significant cardiovascular disease GWAS loci drawn from fifty studies deposited in the NHGRI database10 for cardiac arrythmia, heart failure and myocardial infarction. They found that 19% of the putatively causal SNPs were located in promoter-distal interactions with 347 genes in cardiomyocytes, and the vast majority (90.4%) of SNP-promoter interactions skipped at least one gene promoter and 42% interacted with two different promoters. In addition, these genes’ functions were highly enriched for cardiac function and 78 (22.4%) of the identified genes resulted in a cardiovascular phenotype when knocked out in mice. Similar approaches combining Hi-C data with GWAS loci have been performed in aortic endothelial cells to identify genes associated with coronary artery disease86, while Choy et al87 used Hi-C from embryonic stem cells-derived cardiomyocytes to identify genomic regions in which heart-rate associated genes physically interact with heart-rate associated GWAS loci. Taken together, these results present a clear refutation of the common practice to label the closest gene to the GWAS locus as the most likely candidate gene, and insights from chromatin architecture and interaction lead to the identification of the most likely causal genes within cardiovascular GWAS loci.

Gene and protein interacting networks have been extensively used to study cardiovascular disorders. Talukdar and colleagues used gene expression patterns from 7 tissues involved in cardiovascular physiology to generate disease-associated gene modules based on shared gene expression (or co-expression) patterns88. By mapping these modules to the genome and filtering for networks which overlapped in the mouse, the authors pinpointed and validated several key driver genes. In a follow-up study involving a larger cohort89, the authors noted that some modules exhibited striking coordination of gene expression across tissues, and that predicted regulatory SNPs showed significant enrichment in disease status. This study highlighted adipose tissue gene expression as a key contributor to plasma lipid levels.

In a recent study, Cordero et al90 created co-expression networks from human gene expression derived from left ventricular tissue from 177 failing hearts and 136 healthy controls. The authors used the commonly-used network construction algorithm Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to construct transcriptome networks for both healthy and failing hearts. The authors observed increased co-regulation of known genes involved in cardiac remodeling, EC coupling, cardiac contraction and metabolism, with significant rewiring of intra and inter-module connectivity due to heart failure. They then identified central coordinator genes which showed increases in both local and global connectivity in the diseased network. When compared to genes identified by differential gene expression, the central coordinators were significantly more enriched for cardiomyopathy-related gene ontology terms. The authors then focus on a novel candidate gene, protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 3A (PPP1R3A), which was identified as a central coordinator. Using in vitro and in vivo approaches, the study demonstrates that PPP1R3A knockdown blunts cardiac dysfunction. In a study using the HMDP, Rau et al91 constructed co-expression modules in control and isoproterenol-treated hearts from roughly 90 inbred mouse strains. The authors utilized Maximal Information Component Analysis (MICA) to construct gene modules and identified a module containing 41 genes as being highly associated with heart weight, fluid retention and metabolic phenotypes. The Network Edge Orientation algorithm, which uses genomic data as causal anchors, was applied to the module to identify driver genes which played a significantly larger role in the regulation of the module than other genes. One of these genes, ADAM Metallopeptidase with Thrombospondin Type 1 Motif 2 (ADAMTS2) was identified as a novel heart failure candidate and in vitro studies validated its role in cardiac hypertrophy as well as its key regulatory role in its module. Herrington and colleagues 92 performed a similar study using protein abundances in coronary arteries and aortas from 100 individuals to identify proteins associated with early atherosclerosis, identifying a set of proteins whose expression was used to predict atherosclerosis in a separate cohort of individuals. Overall, the more complex of the phenotypic traits, the better outcome when multi-layers systems analysis are performed.

Interaction between environmental factors and genetics:

Environmental perturbations such as diet, drugs, carcinogens, radiation, pollution, and smoking can potentially directly influence many of the layers. The profound effect of diet on health and metabolism was nicely illustrated in a study where C57BL/6J mice were fed 20 different diets with various rations of carbohydrate, fat or protein, resulting in striking separation in overall health parameters, such as heart rate and longevity93. Parks and colleagues surveyed a panel of inbred mouse strains for body fat response, gene expression, microbiota composition and other clinical traits on high-fat/high-sucrose (HF/HS) or chow diets94,95. While the indicated traits had high heritability regardless of diet, the clinical traits, microbiota profiles and transcriptional landscapes completely shifted between chow and HF/HS conditions (for example, Fig. 2A). Therefore, systems genetics is uniquely positioned to dissect genetic factors and environmental contribution to a particular phenotypic trait, which has major significance to clinical translation regarding therapeutic strategies.

III. Current Challenges and Future Advances in Systems Genetics

The future of medicine will likely be deeply personal one, in which each individual’s health is closely monitored and diseases are prevented and treated before they can become deleterious through personalized regimens. Central to this vision is the development of ‘omics technologies and data-mining capacity to enhance the scope and predictive power of the data and their integration with clinical practices. While much of the current effort focuses on universal genotyping, other biological layers, including epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics will eventually need to be implemented to tackle most of the complex diseases. This evolution has already begun to occur, with projects such as the Vanderbilt PREDICT program96 in which genotype information was included in patient’s electronic medical records and used to provide personalized treatment after surgery. In this section, we discuss the ways in which systems genetics needs to grow and expand in order to meet the needs of the scientific and medical communities to implement the vision of personalized, actionable medicine.

Cohort diversity, size, flux, and layer completeness

As discussed in section II, many of the successes in cardiovascular systems genetics share common features, namely carefully selected, specific phenotyping paired with carefully selected and characterized populations, followed-up with perturbational analyses in the same or similar populations. This is particularly clear in the case of curated animal model populations such as the Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel, where a relatively limited number of individuals results in genome-wide and multi-omic significant results. These results are possible due to higher genetic resolution compared to traditional animal crosses as well as a carefully controlled environment with specifically titrated stressors97 combined with ease of access to crucially important tissue sources such as cardiac tissue whose supply is very limited in human cohorts. To achieve similar results, studies in human populations need to either increase their size, add additional biological layers, characterize their phenotypes more carefully in light of biological principles such as flux, and/or harness the significant diversity across human populations to identify additional loci of interest.

The predictive power of a systems genetics study increases with the number of biological layers interrogated. For example, the MuTher study98 incorporated data from four different layers: genomic, transcriptomic, metabolomic and microbiomic. This depth has resulted in a number of important findings relating to metabolic syndrome and gut microflora. In the cardiovascular field, a prime example is the Metabolic Syndrome in Men (METSIM) study of Finnish men, who have been molecularly phenotyped at multiple biological layers followed by integrated analyses across different datasets using the same principles as outlined above99–101. This integrated approach has led to the identification of elements in the microbiome which influence clinical traits relating to metabolic syndrome through changes to metabolite levels, as well as ways in which metabolite levels act to regulate the microbiome and how changes to the genome affects metabolic syndrome through metabolites and the microbiome102–104.

At the same time, researchers have begun to more fully understand the temporal aspect of many of these biological layers, a concept known as flux, in which the observable values at any layer other than the genome are constantly changing over time in response to external stressors, internal rhythms or simple stochastic chance. A classic example is the daily rhythm of blood pressure, which is lower during the night, begins to rise a few hours before waking, peaks in the mid-afternoon, and then falls again. In Systems approaches, Flux is most frequently talked about in the context of the metabolome, however recent advances in cost and efficiency have allowed researchers to start to analyze how molecules in other biological scales change over time105,106.

An important impediment to the expansion of these studies is the costs involved in performing the high-throughput experiments necessary to generate global ‘omics data. Fortunately, the costs of ‘omics technology continue to drop as technological innovations result in faster, cheaper methods. While the first human genome sequencing effort cost approximately 450 million dollars, today a whole genome can be sequenced for about a thousand dollars. These innovations continue to occur in every biological layer with the development of techniques such as Bulk RNA Barcoding-seq (BRB-seq)107 which can drive the cost of RNAseq down to approximately $20 a sample. In time, personalized medicine may begin to look like an experiment performed by Michael Snyder in 2012108 in which data from every biological layer other than the epigenome were gathered repeatedly from a single individual over 14 months, revealing significant responses across multiple ‘omics levels to changes in response to diet and infection.

The expansion of systems genetics data into larger cohorts should coincide with a push to incorporate a larger and more diverse set of cohorts. Numerous manuscripts over the past few years have called for more frequent ‘omics studies in non-European populations109–112. These studies all highlight that roughly 80% of all individuals reported in GWAS studies was European, with 75% of the remainder coming from a limited range of east Asian populations. European populations are less diverse than other global populations, which allows for easier analyses with smaller overall cohorts but likely limits the overall applicability of the results. For example, many early studies focused on the genetically isolated Icelandic population, with companies such as deCODE striving to genotype the entire population of the island to perform GWAS despite limited applicability to other population which did not share the specific polymorphisms found in the founder population of the nation. While this loss of genetic diversity in our models has implications for missing important genes and pathways involved in disease onset and progression, it has far more crucial effects on the understudied populations as there is ample evidence that risk alleles have different strengths in different populations113, meaning that medical tools such as polygenic risk scores developed from a genetically homogenous cohort may be wildly inaccurate and lead to inappropriate medical responses for the general population114.

New Technologies in ‘Omics’

To make systems genetics approaches widely available, there will be a need to dramatically enhance the robustness while reducing the cost of the current ‘Omics’ technologies. The reduction in cost and expansion in scale for the current high-throughput ‘omics technologies will make experiments possible today or in the near future which would have been prohibitively expensive only a few years ago. High-throughput proteomics, driven by improvements in mass spectrometry has begun to expand beyond protein quantification into explorations of post-translational modifications including phosphorylation115, glycosylation116 and ubiquitination117. Most global epigenetic analyses are currently too expensive to analyze in the numbers necessary to generate new types of QTLs, however it is conceivable that in a few years technologies such as Hi-C, which has already revealed the crucial role that physical DNA conformation has on disease48,118,119, will have advanced to the point that genetic variations which dictate chromosomal 3D structure in healthy and diseased individuals can be identified and integrated into larger ‘omics models. An example of this progress involves the DNA methylome, the first epigenetic layer amenable to high-throughput high-N analyses. Recently, combinations of DNA methylation marks have been used to construct a highly accurate biological aging clock120,121 and as a predictors of type 2 diabetes122.

As indicated above, many of the current ‘omics’ technologies are applied to whole tissue samples with mixed cellular identities. This is a major limitation to extrapolating diverse cellular processes in different cell types. Single Cell technologies have the potential to revolutionize our understanding of biology and the predicative power of systems genetics. This new technology has potential to disentangle tissues such as the heart and blood vessel into their component cell types and to uncover mechanisms of complex diseases with specific cellular contexts. Although the majority of current research in this area is focused on cancer, in which knowledge of the behavior of individual cells is crucial, the technology is rapidly expanding into other tissues and diseases. Single cell RNAseq is perhaps the best known example of a developed form of single-cell technology, with studies examining the change of gene expression on a single-cell basis during heart development123 and disease onset124. Similar analyses are possible in the DNA methylome125,126, proteome127 and microbiome128. Recent studies have even begun to explore how to perform single cell Hi-C analyses129,130 as well as other epigenetic marks131. Most of these studies are limited in the number of individuals studied. It is only a matter of time, however, before such approaches are utilized in a larger population as demonstrated from recent efforts where single-cell eQTL studies are being performed132,133. Further development of these techniques will lead to new classes of QTL mapping and better understanding of diseases. Linked to this expansion in technical ability to examine cells within tissue samples, additional developments in the ability to generate tissues, cell types and, perhaps one day entire organ systems from iPSC cells will allow human researchers access to difficult to collect and study tissue samples as current approaches using surrogate cells or tissues (eg blood samples instead of ventricle samples) reduce the power of various approaches and likely limit their applicability.

In parallel to the rapid progress in ‘Omics” technology hardware, significant developments in computational approaches will need to be realized in order to improve their speed and accuracy, particularly in light of the ballooning number of samples being analyzed either due to increases in study size or transitions to single-cell technologies. These new approaches may involve limiting full analysis to a more easily obtained list of priority targets as seen in the Sakhanenko and Galas Shadows Algorithm134, improving the underlying mathematical framework of an approach to reduce computational complexity as seen in the improvements of speed and efficiency of tools such as Fast-LMM135 when compared to early GWAS approaches, or both, as seen in comparing the Salmon algorithm136 to earlier RNAseq protocols such as the Tuxedo Suite (Tophat, Bowtie, Cufflinks, etc.). Figure 2 contains links to groups working to maintain lists of useful multi-omics computational techniques (e.g. https://github.com/mikelove/awesome-multi-omics) for researchers interested in working in a particular branch of systems genetics.

Conclusion and Translational Implications

Systems genetics studies seek to understand biologic networks and higher order interactions and are, therefore, well suited for the identification of drug targets and their potential side effects137. For example, systems genetics data can be mined to develop disease biomarkers. A recent study used data from a mouse systems genetics of heart failure to identify the protein GPNMB as a potential biomarker that is both sensitive and specific for various forms of human heart failure138. Recent modeling approaches such as Mergeomics are particularly well suited for understanding disease pathways and key driver genes and have led to the identification and validation of high confidence targets139. Related approaches have also been used effectively to predict drug target pathways and mechanisms. For example, one study used targeted ER stress pathways (either injected with 4-phenyl butyrate or overexpressing X-box binding protein 1) in ob/ob mice then analyzed liver gene expression using The Connectivity Map, whereby transcriptomic data can infer selective compounds which targets a given set of pathways140,141. Integration of these data prioritized Celastrol as a potential regulator of ER stress pathways.

As systems genetics continues to mature as a field, its ability to identify polymorphisms, genes and pathways which contribute to a phenotype of interest will grow. Larger study populations, sophisticated ‘omics’ tools to generate systems-level data in a more cost-effective manner and faster, more intuitive computational tools will lead to more accurate insights into disease at individual level. The results of systems genetics studies are beneficial to all members of the scientific community, from basic discovery of novel genes and pathways, to clinical practice guided by novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets. At the present time, systems genetics is well suited to understand molecular phenotypes like gene expression and metabolite abundance as well as ‘simpler’ clinical traits such as blood pressure. These benefits, however, will be realized for many more heritable and acquired diseases, and become increasingly personalized as more individuals from more diverse populations are examined.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

This work is supported in part by NIH grants HL123295, HL144651, DK117850, HL147883 and HL114437 to YW and JL. CDR is supported by NIH K99HL138301

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- GWAS

Genome Wide Association Studies

- EWAS

Epigenome Wide Association Studies

- TWAS

Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies

- PheWAS

Phenome-wide Association Studies

- RNAseq

RNA sequencing

- WGBS

Whole genome bisulfite sequencing

- RRBS

Reduced representational bisulfite sequencing

- ChIP-seq

Chromatin Immuno-precipitation sequencing

- 4C-seq

Circularized Chromosome Conformation Capture-sequencing

- High-C seq

High throughput Chromosome conformation capture sequencing

- SILAC

Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids

- RIP-seq

RNA Immunoprecipitation sequencing

- ATAC-seq

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin sequencing

- BRB-seq

Bulk RNA Barcoding sequencing

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- QTLs

Quantitative Trait Loci

- eQTL

expression Quantitative Trait Loci

- meQTLs

DNA methylation Quantitative Trait Loci

- xQTLs

epigenetic Quantitative Trait Loci

- miQTLs

miRNA Quantitative Trait Loci

- sQTLs

splicing Quantitative Trait Loci

- pQTLs

protein Quantitative Trait Loci

- mQTLs

metabolite Quantitative Trait Loci

- cQTLs

clinical Quantitative Trait Loci

- HMDP

Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel

- ECM

Extra-Cellular Matrix

- LV

Left Ventricle

- LDL

Low Density Lipoprotein

- iPSC

inducible Pluripotent Stem Cell

- HF/HS

High-Fat and High-Sucrose Diet

- NHGRI

National Health Genome Research Institute

Footnotes

Disclosures: No financial, personal or professional relationships with other people or organizations that could reasonably be perceived as conflicts of interest or as potentially influencing or biasing this manuscript.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 139, e56–e66 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoeger T, Gerlach M, Morimoto RI & Nunes Amaral LA Large-scale investigation of the reasons why potentially important genes are ignored. PLOS Biol. 16, e2006643 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]