Abstract

Background

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, cath labs have had to modify their workflow for elective and urgent patients.

Methods

We surveyed 16 physicians across 3 hospitals in our healthcare system to address COVID-19 related concerns in the management of interventional and structural heart disease patients, and to formulate system wide criteria for deferring cases till after the pandemic.

Results

Our survey yielded common concerns centered on the need to protect patients, cath lab staff and physicians from unnecessary exposure to COVID-19; for COVID-19 testing prior to arrival to the cath lab; for clear communication between the referring physician and the interventionalist; but there was initial uncertainty among physicians regarding the optimal management of ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI; percutaneous coronary intervention versus thrombolytics). Patients with stable angina and hemodynamically stable acute coronary syndromes were deemed suitable for initial medical management, except when they had large ischemic burden. Most transcatheter aortic valve implantations (TAVI) were felt appropriate for postponement except in symptomatic patients with aortic valve area <0.5 cm2 or recent hospitalization for heart failure (HF). Most percutaneous mitral valve repair (pMVR) procedures were felt appropriate for postponement except in patients with HF. All left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) and patent foramen ovale (PFO)/atrial septal defect (ASD) closure procedures were felt appropriate for postponement.

Conclusion

Our survey of an experienced team of clinicians yielded concise guidelines to direct the management of CAD and structural heart disease patients during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Cath lab, COVID, Structural

Highlights

-

•

In our survey of interventional cardiologists, primary PCI was the preferred method for treating patients with STEMI.

-

•

Stable angina and hemodynamically stable ACS are suitable for medical management, except if they have large ischemic burden.

-

•

TAVI maybe postponed except in symptomatic patients with AVA < 0.5 cm2 or those with recent heart failure.

-

•

Percutaneous MVR maybe postponed except in patients with HF.All LAAC, PFO/ASD closures maybe postponed.

-

•

Most follow-up visits can be conducted via telemedicine rather than in-person visits.

In light of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, professional societies have released broad guidelines for the management of cath lab patients during the pandemic [1,2]. Initial guidelines focused largely on coronary interventions and do not address the care of patients who require structural heart interventions (e.g. TAVI, pMVR, LAAC, PFO/ASD closure). Further, it is unclear whether physicians uniformly agree with professional society guidelines and significant questions remain unanswered. For example, which elective coronary and structural heart interventions may be deferred till after the pandemic? How should we best manage STEMI: with PCI or thrombolytics? When should personal protective equipment (PPE) be worn during a procedure? We surveyed interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons and imaging cardiologists in our multispecialty group to answer these questions. The purpose of this exercise was to create a framework that can serve as a ready reference for cath labs during the early phase of this pandemic, that encompasses not only coronary but also structural interventions, that prioritizes care to unstable patients without unnecessarily exposing stable patients to COVID-19 infection, that provides protection to hospital staff and cardiologists and respects the resource constraints our healthcare systems face.

1. Methods

Across our multi-hospital healthcare delivery system, we surveyed 16 physicians [9 interventional cardiologists (IC, including 4 structural IC), an electrophysiologist experienced in left atrial appendage closure (LAAC), 2 imaging cardiologists and 4 cardiac surgeons] at 3 hospitals in Central and Northeastern Pennsylvania to delineate specific criteria to guide management of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and structural heart diseases [severe aortic stenosis (AS), mitral regurgitation (MR), atrial fibrillation with poor candidacy for oral anticoagulation (OAC), and patent foramen ovale (PFO)] and atrial septal defect (ASD)]. Using email communication, online questionnaire and conference calls, we conducted 2 separate surveys, one for CAD scenarios and 1 for structural heart interventions.

1.1. CAD

After an initial round of emails to explore common concerns, an electronic survey was conducted of 8 interventional cardiologists (IC) to delineate optimum treatment strategies for STEMI patients, focusing on the use of thrombolytics versus PCI, the need for COVID testing prior to cath lab arrival and use of PPE for cath lab staff and IC. Subsequently, we held a telephone conference call with all ICs in attendance to formalize system wide guidelines for each of the common CAD scenarios (STEMI, hemodynamically unstable acute coronary syndrome (ACS), hemodynamically stable ACS, or stable angina). We classified patients into 4 categories based on their COVID status: ‘COVID+ and intubated’, ‘COVID+ but not intubated’, ‘Person Under Investigation’ (PUI, defined as recent fever, upper respiratory symptoms or travel within 14 days to CDC level 2–4 area, or exposure to a confirmed case or cluster of suspected cases), and ‘Healthy’ (defined as COVID- and not PUI). We posed the following specific questions: 1. Which patients with unknown COVID status should be tested for COVID using rapid point-of-care (POC) testing prior to arrival to the cath lab? 2. When should physicians and cath lab staff wear personal protective equipment (PPE)? 3. For STEMI, which patients, if any, should be considered for thrombolytic therapy? 4. For ACS patients, when should we consider invasive versus conservative management? 5. Which patients with stable CAD should undergo coronary angiography and possible PCI?

1.2. Structural heart interventions

For 4 separate procedures (TAVR, LAAC, percutaneous mitral valve repair (MVR), PFO/ASD closure), an initial set of suggestions about pre-operative work-up, intervention and post-procedure follow-up was sent by email to 4 structural ICs, 4 cardiac surgeons, 1 Electrophysiologist and 2 imaging cardiologists for their input. The initial proposal was modified and approved for use by the structural teams across our health care system.

2. Results

Our survey yielded some common responses. 1. Clear communication between the referring physician and interventional cardiologist is necessary for all patients sent to the cath lab so that the urgency of the procedure is established. In STEMI cases, this will usually involve the Emergency Department physician and IC. In other instances, this will usually involve the referring cardiologist or critical care medicine attending and the IC. 2. COVID status should be determined for elective patients coming to the cath lab if they meet PUI screening criteria. 3. The IC and Cath lab staff should don PPE (gown, N-95 mask, face shield; or powered air-purifying respirator) for all COVID+ patients and PUI. 4. In COVID+ or PUI patients with STEMI, a lower threshold should be used for endotracheal intubation before arrival to the cath lab to avoid aerosolization from coughing during the procedure.

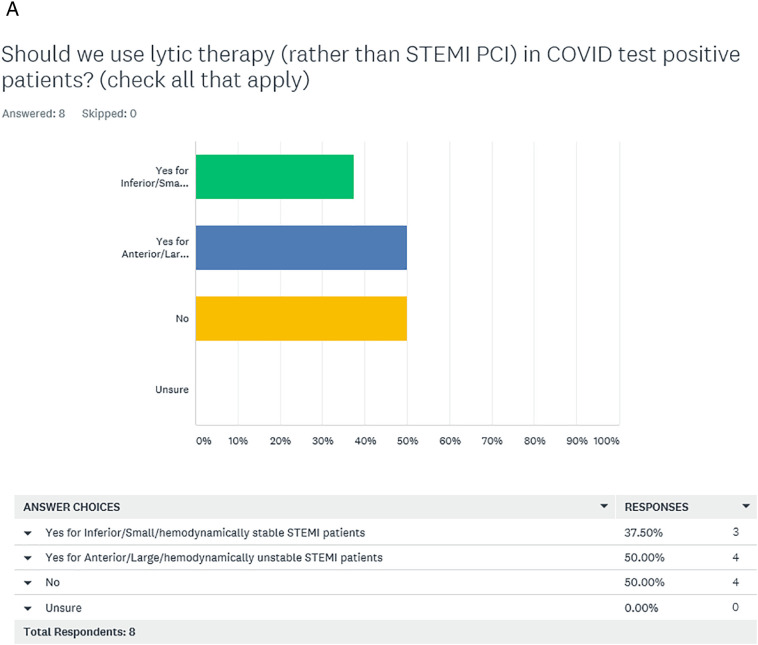

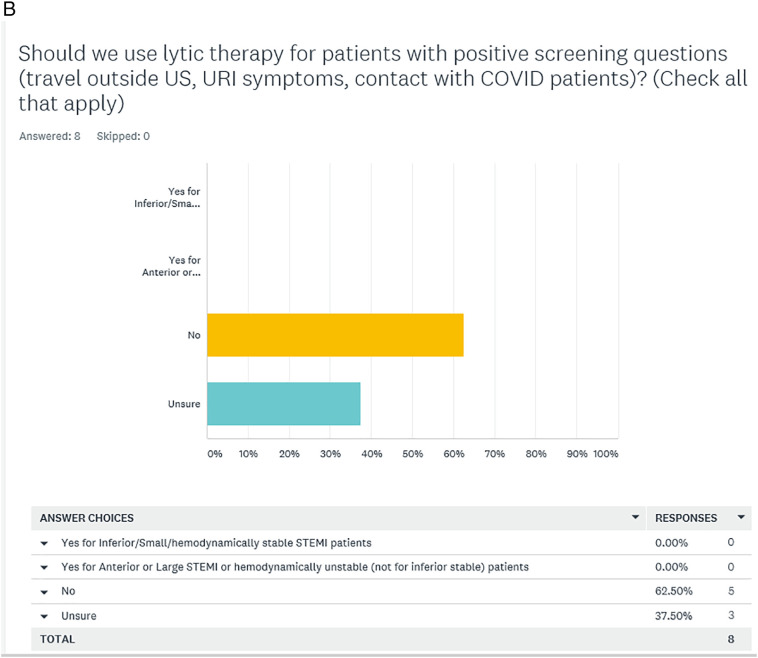

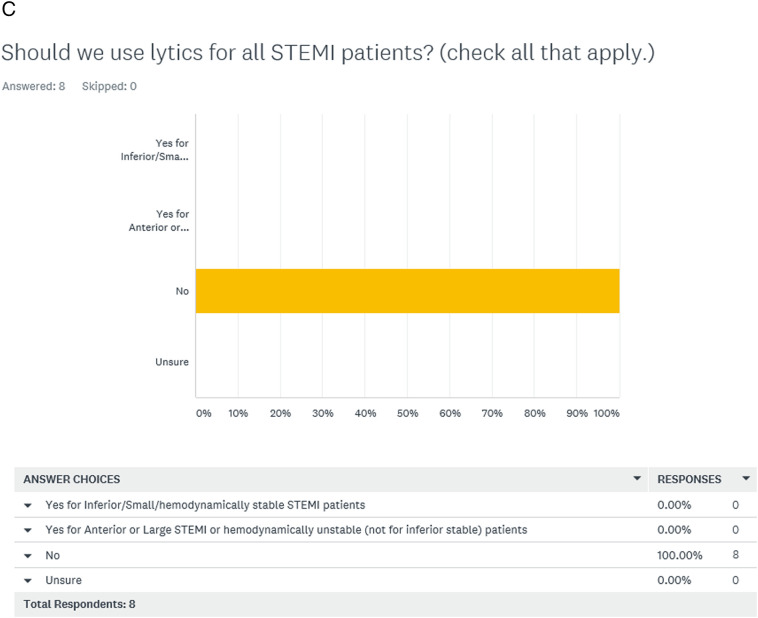

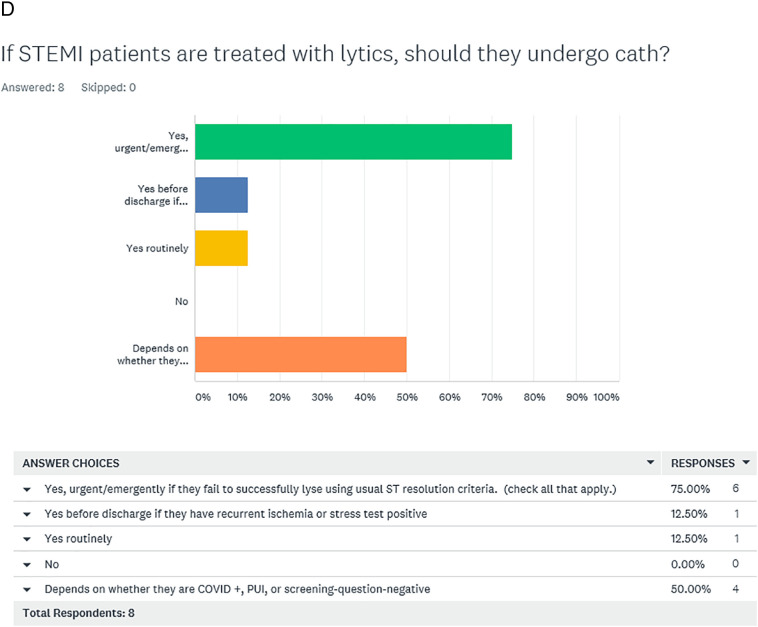

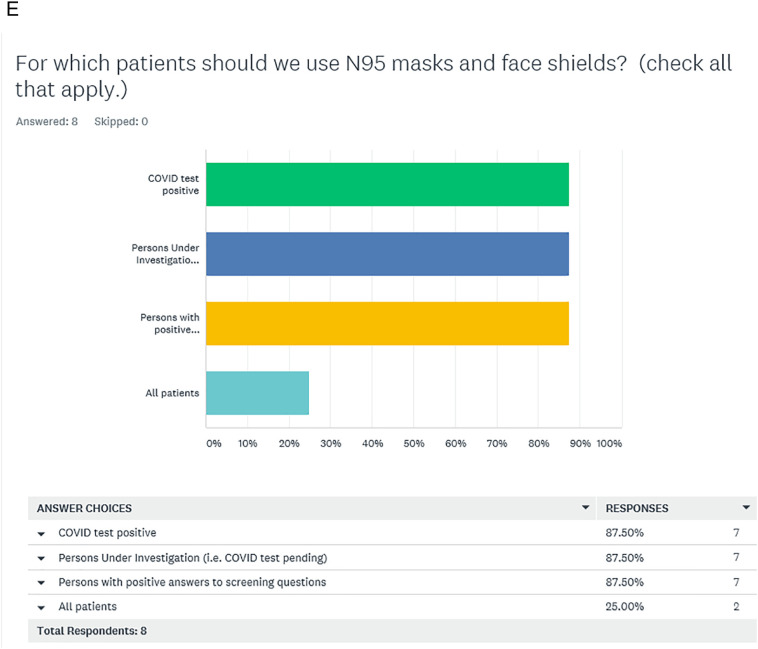

2.1. Electronic survey (Fig. 1A–E)

Fig. 1.

Electronic survey responses of 8 interventional cardiologists to questions regarding management of STEMI and use of personal protective equipment in the cath lab during the COVID-19 pandemic.

With regards to care of the STEMI patient, there was initial uncertainty in the surveyed group about use of PCI (versus lytics). For COVID+ patients, 4/8 ICs felt we should continue to use primary PCI for all STEMI cases, while 4/8 voted to use lytics for some STEMI cases (Fig. 1A). For PUI patients presenting with STEMI, 5/8 ICs did not approve the use of lytics and 3/8 ICs were ‘unsure’ (Fig. 1B). None of the ICs felt that we should use lytic therapy for all STEMI patients during the pandemic (Fig. 1C). If lytic therapy was used, 6/8 ICs felt that urgent or emergent coronary angiography should be performed if there was evidence of lytic failure (Fig. 1D). Regarding the use of PPE, most agreed that the interventional team use PPE for COVID+ and PUI+ patients, while a minority (2/8 ICs) felt that the interventional team use PPE for all STEMI cases during the pandemic (Fig. 1E).

2.2. Teleconference

The pros and cons of primary PCI versus lytics were discussed at the teleconference, with emphasis on randomized trials showing significant improvement in outcomes with primary PCI3. Following telephone discussion, our group preferred PCI (over lytics) for STEMI and invasive management (over conservative therapy) for hemodynamically unstable ACS. Whereas, for stable angina and hemodynamically stable ACS, our group preferred conservative management except when patients had rest angina or large ischemic burden. Specific treatment modalities preferred by our surveyed IC are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Suggested workflow for coronary artery disease management during COVID-19 pandemic.

| Condition | COVID+ patient ICU/intubated |

COVID+ patient Not ICU |

Person under investigation (PUI) | Healthy patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction | –Cath and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), rather than lytic therapy –Medical therapy if PCI would be futile or unlikely to help the patient |

–Repeat PUI screening questions. –PCI by usual criteria |

||

| Hemodynamically unstable acute coronary syndrome | –Cath and PCI –Medical therapy if PCI would be futile or unlikely to help the patient |

–Repeat PUI screening questions. –Cath and PCI |

||

| Hemodynamically stable acute coronary syndrome | Medical management | –Medical management –Stress test or computed tomographic angiography (CTA) –Cath if worsening angina, markedly abnormal stress test or proximal coronary occlusions on CTA |

||

| Stable angina | Medical management | –Medical management –Stress test or CTA –Cath if worsening angina, markedly abnormal stress test or proximal coronary occlusions on CTA |

||

2.3. Structural heart interventions

Modified pathways proposed for the pre-procedural, procedural and post-procedural aspects of care are shown in Table 2 . Given the elective nature of these procedures, there was consensus that most structural procedures can be postponed, with few exceptions.

Table 2.

Suggested workflow for structural heart disease management during COVID-19 pandemic.

| New office consult, diagnostic cath and interventional procedure | Post-procedure follow up | |

|---|---|---|

| Transcutaneous aortic valve implantation (TAVI) | Postpone unless - Symptomatic with aortic valve area <0.5 cm2, or - Heart failure hospitalization within prior 6 months, or - Compelling social reasons (e.g. need support from other family members) |

Keep 1-week post-TAVR visit. Postpone or do by telemedicine: 1-month, 6-month and 1-year post-TAVI appointments. Postpone echocardiograms unless patient is symptomatic |

| Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) | Postpone all new appointments and planned cases, unless compelling social reasons | - Postpone or do by telemedicine: all follow up visits, including all 45-day post LAAC trans-esophageal echocardiograms (TEEs). - In selected cases, clinicians may stop oral anti-coagulation at 45 days, until TEE can be rescheduled. - Consider computed tomographic angiography to rule out LAA clot. |

| Percutaneous mitral valve repair | Postpone unless HF hospitalization within prior 6 months, or compelling social reasons | Postpone or do by telemedicine: 1-month follow up and echocardiograms, unless patient has symptoms of HF |

| Patent foramen ovale/atrial septal defect closure | Postpone all new appointments and planned cases, unless compelling social reasons | - Postpone or do by telemedicine: all follow up visits, and post-implant TEE. - Perform Trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE) for assessment of closure. If TTE suggests complete closure, switch dual anti-platelet therapy to single anti-platelet therapy. |

3. Discussion

Although there was significant initial disagreement among IC about the management of STEMI and use of PPE (Fig. 1A–E), we were able to achieve consensus and derive a concise framework for the care of patients with CAD (Table 1) and those requiring structural heart interventions (Table 2) during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. The guiding principle of our framework is to provide judicious care to these vulnerable patients without unnecessarily exposing them or our teams to COVID-19. In the management of STEMI, the consensus was to continue to use primary PCI over thrombolytics. This is consistent with prior trials that have demonstrated greater efficacy of primary PCI over thrombolytics in the management of STEMI [3]. The clinical benefit of primary PCI over thrombolytics is greater in anterior versus non-anterior myocardial infarction and in higher-risk patients [4,5]. Hence, we specifically surveyed the 8 ICs on whether lytics should be considered in lower-risk subsets or inferior MI. Our surveyed group felt that we should continue to use primary PCI over thrombolytics for all STEMI cases, as we have traditionally done in the pre-COVID era. This is in contrast to the position paper from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions Emerging Leader Mentorship Members and Graduates [2], that recommended consideration of lytic therapy for low-risk STEMI in the COVID era. Our specific recommendation to consider invasive management of all STEMI cases was guided by the concern that some patients presenting with STEMI may indeed have COVID myocarditis rather than coronary occlusion, and the use of lytic therapy in such cases may unnecessarily expose patients to increased risk of bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage.

The recently concluded ISCHEMIA trial of patients with stable CAD showed that initial invasive therapy provided greater improvement in angina-related health status but did not reduce the risk of ischemic cardiovascular events or death from any cause compared to initial conservative therapy [6,7]. Consistent with prior observations that a high-risk non-invasive test is a marker of poor prognosis [8], our surveyed physicians preferred an invasive approach over conservative management in stable CAD patients with a large ischemic burden.

Subsequent to the conduct of our surveys, professional societies in the US also released guidelines for structural heart interventions [9], which closely resembled those our structural team agreed upon. Many ongoing developments in the management of COVID-19 will influence how our approaches evolve. These include the availability of point-of-care testing for COVID-19, the prevalence of myocarditis in patients presenting with ST elevations on the initial EKG [10], the success of definitive antiviral treatment strategies, and the availability of preventive strategies, including vaccines. While institutional priorities, medicolegal concerns, financial concerns related to diminished productivity, and constraints on local resources will vary across systems, our study establishes that system wide policies can be implemented at short notice with appropriate involvement of clinicians and administrative leadership.

4. Limitations

A major limitation of our paper is that our recommendations are based on the collective opinions of an experienced team of interventionalists working in an integrated health care system. There are currently no data to support the recommendations made by our team or professional societies. Further, as COVID cases decline, recommendations for the care of patients with coronary and structural heart disease will evolve in ways that are hard to predict. Many questions remain unanswered. Will interventional teams continue to use PPE in patients presenting to the cath lab with incidental upper respiratory symptoms? Will a cautious approach to invasive management of CAD with low ischemic burden become the new norm? Will some of the follow-up visits conducted in the weeks after structural interventions continue to occur with telemedicine, even after the pandemic resolves? Our paper provides practicing clinicians with a framework of recommendations during the initial and resurgent phases of the COVID pandemic.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kishore J. Harjai: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Shikhar Agarwal: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Terry Bauch: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Mark Bernardi: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Alfred S. Casale: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Sandy Green: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Michael Harostock: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Nicholas Ierovante: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Vernon Mascarenhas: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Martin Matsumura: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Yassir Nawaz: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Thomas Scott: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Deepak Singh: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Joseph J. Stella: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Pugazhendi Vijayaraman: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Gregory Yost: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. James C. Blankenship: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgement

No funding was obtained for this manuscript. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Lori Scalzo, RN, with the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Welt F.G.P., Shah P.B., Aronow H.D., Bortnick A.E., Henry T.D., Sherwood M.W. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: from ACC’s interventional council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szerlip M., Anwaruddin S., Aronow H.D., Cohen M.G., Daniels M.J., Dehghani P. Considerations for cardiac catheterization laboratory procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic perspectives from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions Emerging Leader Mentorship (SCAI ELM) members and graduates. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keeley E.C., Boura J.A., Grines C.L. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003 Jan 4;361(9351):13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Keefe J.H., Jr., Grines C.L., DeWood M.A., Bateman T.M., Christian T.F., Gibbons R.J. Factors influencing myocardial salvage with primary angioplasty. J Nucl Cardiol. 1995 Jan-Feb;2(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/s1071-3581(05)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz R., Weiss A.T., Leibowitz D., Rot D., Pollak A., Lotan C. Thrombolysis followed by coronary angiography versus primary percutaneous coronary intervention in non-anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Invasive Cardiol. 2013 Dec;25(12):632–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spertus J.A., Jones P.G., Maron D.J., O’Brien S.M., Reynolds H.R., Rosenberg Y. Health-status outcomes with invasive or conservative care in coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 9;382(15):1408–1419. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maron D.J., Hochman J.S., Reynolds H.R., Bangalore S., O’Brien S.M., Boden W.E. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 9;382(15):1395–1407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel M.R., Calhoon J.H., Dehmer G.J., Grantham J.A., Maddox T.M., Maron D.J. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/STS 2017 appropriate use criteria for coronaryrevascularization in patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017 Oct;24(5):1759–1792. doi: 10.1007/s12350-017-0917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah P.B., Welt F.G.P., Mahmud E., Phillips A., Kleiman N.S., Young M.N. Triage considerations for patients referred for structural heart disease intervention during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an ACC/SCAI consensus statement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]