Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has turned into a global human tragedy and economic devastation. Governments have implemented lockdown measures, blocked international travel, and enforced other public containment measures to mitigate the virus morbidity and mortality. As of today, no drug has the power to fight the infection and bring normalcy to the utter chaos. This leaves us with only one choice namely an effective and safe vaccine that shall be manufactured as soon as possible and available to all countries and populations affected by the pandemic at an affordable price. There has been an unprecedented fast track path taken in Research & Development by the World community for developing an effective and safe vaccine. Platform technology has been exploited to develop candidate vaccines in a matter of days to weeks, and as of now, 108 such vaccines are available. Six of these vaccines have entered clinical trials. As clinical trials are “rate-limiting” and “time-consuming”, many innovative methods are in practice for a fast track. These include parallel phase I-II trials and obtaining efficacy data from phase IIb trials. Human “challenge experiments” to confirm efficacy in humans is under serious consideration. The availability of the COVID-19 vaccine has become a race against time in the middle of death and devastation. There is an atmosphere of tremendous hype around the COVID-19 vaccine, and developers are using every moment to make claims, which remain unverified. However, concerns are raised about a rush to deploy a COVID-19 vaccine. Applying “Quick fix” and “short cuts” can lead to errors with disastrous consequences.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus, vaccine, platform technology clinical trials

Abbreviations: ADE, Antibody-Dependent Enhancement; CEPI, Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; MERS-CoV, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus; MHC, Major Histocompatibility Complex; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; WHO, World Health Organization

The coronavirus infection which originated from Wuhan, China, in December 2019, has turned into a global catastrophe.1 The virus has been designated as severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease caused by the agent as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).2 World Health Organization (WHO) pronounced the disease as a pandemic on March 11, 2020.3 As of May 4th, 2020, the infection has spread to 212 countries and territories around the World and 2 international conveyances, with over 3.5 million cases and around 250000 deaths.4 The disease on average affects over 33,000 individuals with over 1300 deaths daily. The world community has responded to the challenge of death and devastation with resilience and determination.5 Governments have implemented lockdown measures, blocked international travel, and enforced other public containment measures to mitigate the virus morbidity and mortality.6, 7, 8 There has been a major understanding of the disease as well as the pathogen, and these data have been generated and widely publicized in a matter of days and weeks rather than years and decades, an unprecedented occurrence in the history of medicine.9, 10, 11, 12

Coronavirus family

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to a family of zoonotic viruses known as Coronavirus, genus Betacoronavirus and is closely related to 2 other viruses namely Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV).13 All 3 are bat viruses and cross over to cause human infection through an intermediate host (civets for SARS-CoV, camels for MERS-CoV, and possibly pangolins for SARS-CoV-2).14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Coronaviruses are enveloped viruses, around 125 nm in diameter, with a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome of around 30 kb and a nucleocapsid of helical symmetry. This is wrapped in an icosahedral protein shell. The surface has multiple club-shaped spikes, which creates the appearance of solar corona on electron micrsocopy (EM). The viral envelope consists of a lipid bilayer, in which the membrane (M), envelope (E), and spike (S) structural proteins are anchored. All the coronaviruses use angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors as a cellular entry receptor; however, the propensity of SARS-CoV-2 to attach to these receptors is much higher, giving it high infectivity.13

Need for coronavirus vaccine

There has been an intensive search for an effective drug against the virus or the resultant disease and has not led to any breakthrough agents. Few drugs namely hydroxychloroquine and remdesivir have been advocated as desperate measures to fight COVID-19 based on a few preliminary, contradictory, and inconclusive studies.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 What we need is a drug that is at least 95% effective to stop the pandemic. These and other drugs may save lives but are nowhere near that power to bring normalcy in the utter chaos caused by the pandemic.24 This leaves us with only one choice namely an effective and safe vaccine that shall be manufactured as soon as possible and available to all countries and populations affected by the pandemic at an affordable price.25,26 A vaccine has the power to generate herd immunity in the communities, which will reduce the incidence of disease, block transmission, and reduce the social and economic burden of the disease. Very high immunization coverage can effectively fight the pandemic, prevent secondary waves of infection, and control the seasonal endemic infection outbursts. Eventually, the disease can be eradicated as has happened in many other diseases that have had even with higher potential than COVID-19 to cause pandemics namely smallpox, poliomyelitis, etc.27,28

Vaccine immunology

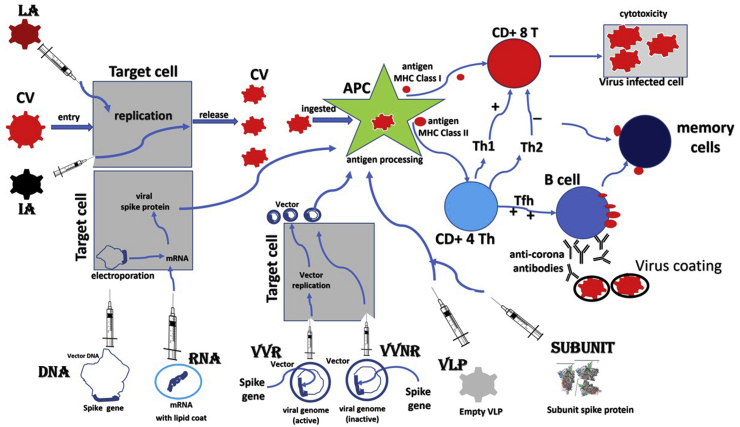

Adaptive Immune Response

A vaccine is medical preparations ranging from intact organisms (attenuated live or inactivated) to genetically engineered parts of the organisms (antigenic) that induce both arms of the adaptive immune system and stimulate a sufficient number of memory T cells and B lymphocytes.29 Vaccines should contain antigens necessary to mount the specific response without causing disease. Once challenged with the pathogen, memory cells yield effector T cells and antibody-producing B cells and fight the infection. The antibodies have to be the neutralizing type which binds to the virus and block infection.30 The virus coated with neutralizing antibodies either cannot interact with the receptor or may be unable to uncoat of the genome. Most currently licensed vaccines induce neutralizing antibody responses capable of mediating long-term protection against lytic viruses such as influenza and smallpox.31 The T cell–based responses that recognize and kill infected cells do also fight the infection.32 Following antigen processing in dendritic cells, the small peptides are displayed at the cell surface at the groove of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II molecules. Cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) recognize MHC class I-peptide complexes and differentiate into cytotoxic effector cells capable of killing infected cells or pathogens. Helper T cells (CD4+) recognize MHC class II-peptide complexes and differentiate in effector cells that produce preferentially T helper 1 cells (Th1) or T helper cells 2 (Th2) cytokines (Figure 1). Th1 support CD8+ T cell differentiation, which is in contrast inhibited by Th2-like cytokines. Vaccines against chronic pathogens namely Mycobacterium tuberculosis, malaria, HCV, HIV, etc. more often require cell-mediated immune responses to control the infection.33

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of 8 platform strategies used for the development of COVID-19 vaccines, and the pathway each one follows to induce T cell and B cell immune response. The strategies include live-attenuated vaccine (LA), inactivated vaccine (IA), DNA vaccine (DNA), RNA vaccine (RNA), viral vector replicating vaccine (VVR), viral vector nonreplicating (VVNR), virus-like particles (VLP), and subunit vaccine (Subunit). CV, coronavirus; APC, antigen processing cell.

Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

The success of a vaccine against a pathogen is a complex issue and depends on the biology of the virus and the type of immune response elicited by the body against the organism. While vaccines have been successful against several pathogens including 14 major infectious diseases,27,28 not all infectious diseases are vaccine-preventable.34,35 The development of vaccines against HIV and HCV has proved challenging. These viruses have an extreme genetic heterogeneity including the hypervariable regions (target for neutralizing antibodies), and the mutation contributes to immune escape.36 The mutations lead to a mixture of genomes in the patient over time and from patient to patient. Also, antibodies mounted against such viral infections are predominantly nonneutralizing. Neutralizing antibodies are often either absent or weak to fight the pathogen or neutralize only a narrow range of circulating viral strains and only appear in a subgroup of patients who either recover or are “elite controller”.37 Another aspect to be considered is whether the virus can be grown in cell culture and transmitted to small animals for experimentation. Since HCV has been discovered by molecular cloning in 1989, its propagation in cell culture has been difficult, which hampers the ability of investigators to experiment with various antigenic components of the virus.38

COVID-19 Vaccine Immunology

To develop a safe and effective vaccine against COVID-19, we need to consider several things about the SARS-CoV-2 and the immune response against the natural infection and the vaccine.

Mutations

Does SARS-CoV-2 mutate, how fast and will mutations cause a phenomenon of immune escape as is seen in HIV and HCV.34,35 SARS-CoV-2 has shown mutations as is true to every RNA virus. However, the mutations are slow and mild, and mutants show nearly similar sequences as in the parent strain. Dorp et al.39 studied genomic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 and recorded 198 filtered recurrent mutations; however, most of the mutations were either neutral or even deleterious and of no clinical significance in vaccine immunity. Ahmad et al.40 found no mutations in 120 available SARS-CoV-2 sequences and identified a set of B cell and T cell epitopes derived from the spike (S) and nucleoprotein (N) proteins that map identically to SARS-CoV-2 proteins. These findings provide a screened set of epitopes that can help guide experimental efforts toward the development of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2.

COVID-19 Immune Response

What type of immune response occurs in natural COVID-19 and after vaccination and are antibodies neutralizing in nature? SARS-CoV-2 infection evokes a robust adaptive immune response of both T cell and B cell type arms.41,42 Furthermore, both IgM and IgG antibodies appear around the 10th day of infection, and most patients seroconvert within 3 weeks. The antibodies are raised against internal nucleoprotein (N) and spike protein (S) of the virion and have neutralizing activity.43 Now that several candidate vaccines are in the clinical trial, investigators shall study the strength and nature of immune response against the vaccine antigen (mostly spike protein).

COVID-19 Re-infections

Are people who recover from COVID-19 infection protected from a second or a third infection? Should re-infections occur, it would imply that immune response against SARS-CoV-2 is not protective, making possibilities of a successful vaccine difficult. There were scary reports from South Korea about patients thought to have recovered from COVID-19 had tested positive again.44 An intense debate started about re-activation or re-infections of the virus. Soon these reports were put to rest, and the positive sample were found to be residual dead fragments of the virus, not the virus, which had re-activated or re-infected.45 After these reports, 2 groups of investigators have shown that SARS-CoV-2 antibodies are protective. Bao et al. showed that 2 monkeys who recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection were protected from re-infection on the challenge during convalescence.46 Gao et al. administered candidate vaccine PiCoVacc Sinovac Biotech to mice, rats, and nonhuman primates. The antibodies raised against the vaccine in animals showed neutralizing ability against SARS-CoV-2 strains. Three immunizations of 2 doses (3 μg or 6 μg per dose) gave partial or complete protection in macaques against SARS-CoV-2.47 These data are exciting and if reproducible in humans confirm that vaccines against COVID-19 shall be protective.

Duration of Immunity

For the COVID-19 vaccination program to succeed, the antibody response mounted against the virus/vaccine must be long-lasting. As of today, it is not possible to address this question as the virus has been in the community only for the last few months. However, we can take leads from data generated about the duration of immunity against 2 other coronaviruses namely SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.14,17 Both these viruses, which are closely related to SARS-CoV-2, induce a robust T cell and B cell immune response which is long-lasting. Many candidate vaccines against both these viruses had gone through successful clinical trials and are safe and immunogenic.48

Antibody-Dependent Enhancement

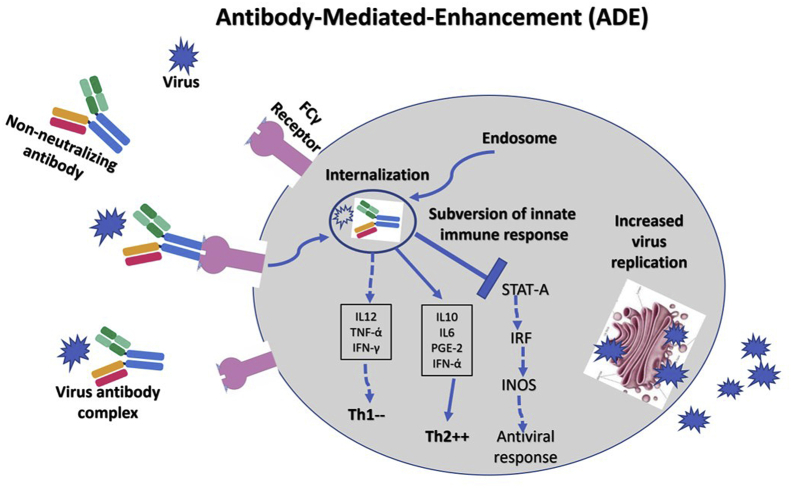

The greatest fear among vaccine developers is to create a vaccine that does not protect from infection but causes disease exacerbation, increased morbidity, and mortality.48, 49, 50, 51 Some vaccines can mount antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), which negates the basic purpose of vaccination.52 This response is mediated by the type of nonneutralizing antibodies mounted against infection or vaccination. The immune response to such vaccines is subverted, leading to exacerbated illness. This could be because of Fc receptor- or complement bearing cells-mediated mechanisms. The Fc-region of the antibody binds to FCγR on the immune cells, which subverts the immune response by reducing TH1 cytokines (interleukin 2 (IL-2), tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a), and interferon gamma (IFN-g)) and skews TH2 cytokines (interleukin 10 (IL-10), interleukin 6 (IL-6), prostaglandin E2 (PGE-2), and interferon alpha (INF-a)) and inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription protein pathway leading to increased viral replication (Figure 2). ADE is of clinical significance in several viral infections including influenza, RSV, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, Dengue virus, Zika virus, and West Nile virus. Considering ADE is a major impediment to vaccine development, efforts to identify highly selected epitopes have been done to avoid the production of antibodies responsible for disease enhancement.

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing depicting FCγ receptor (FCγR)–mediated antibody-mediated enhancement. This response is mediated by the type of nonneutralizing antibodies mounted against infection or vaccination. The immune response to such vaccines is subverted, leading to exacerbated illness. The Fc-region of the antibody binds to FCγR on the immune cells, which subverts the immune response by reducing TH1 cytokines (IL-2, TNF-a, and IFN-γ) and skews TH2 cytokines (IL-10, IL-6, PGE-2, and INF-ά) and inhibits STAT pathway leading to increased viral replication. STAT-A, signal transducer and activator of transcription protein-A; IRF, interferon regulatory factor, INOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase.

ADE has been reported in animals during vaccination trials with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.14,17,35 Vaccine candidates against coronaviruses based on full-length spike protein induce nonneutralizing antibodies, lack of protection of animals against a viral challenge, and severe disease enhancement presenting as enhanced hepatitis, increased morbidity, and stronger inflammatory response.17 As of today, there are no reports of ADE with the use of COVID-19 candidate vaccines in nonhuman primates and humans.51 However, it is an early period in the development of these vaccines, and as the matter is of major importance in the success of such a vaccine, we need to be vigilant. ADE following COVID-19 vaccination if reported can be prevented by shielding nonneutralizing epitopes of S protein by glycosylation or selecting critical neutralizing epitopes of the S antigen to elicit a more robust protective immunity.

Developing a COVID-19 vaccine

Stages of Vaccine Development

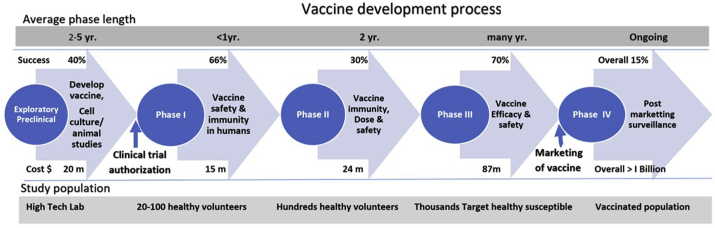

Every new vaccine follows a stringent protocol in Research and Development (R&D) which has to be meticulously followed and completed before it is licensed to be marketed (Figure 3). Regulatory authorities namely WHO, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the European Medicines Agency, and national authorities of many countries have issued guidelines relevant to the clinical evaluation of vaccines.53, 54, 55 The guidelines for vaccine development are more stringent than those meant for drug development. The reason for this is obvious, and the vaccines are for global use, have enormous potential for production and marketing, and are given to healthy populations including children, elderly, and pregnant mothers. The vaccine development follows a unique stepwise pattern and is broadly divided into Exploratory, Preclinical, Clinical, and Postmarketing stages. The clinical stage is divided into 3 phases, namely phases I, II, and III. There are 2 regulatory permissions needed namely “Clinical Trial Authorization” before the clinical stage to allow “First-in-human” testing and “Biologic License Application/Approval” for the marketing of the vaccine after successful clinical trials (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Schematic drawing showing steps in vaccine development. The vaccine development follows a unique stepwise pattern and is broadly divided into Exploratory, Preclinical, Clinical, and Postmarketing stages. The clinical stage is divided into 3 phases, namely phases I, II, and III. There are 2 regulatory permissions needed namely “Clinical Trial Authorization” before the clinical stage to allow “First-in-human” testing and marketing of the vaccine after successful clinical trials.

Table 1.

The Vaccine Development Stages and the Process.

| Phase | Aim | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Exploratory | Develop a vaccine. | Research intensive phase. Identify synthetic or natural antigen. Develop a vaccine (natural or synthetic). Time: 25 years.b The success rate to proceed is 40%.g Causes of failure based on the nature of the pathogen. |

| Preclinical |

The vaccine is safe and immunogenic. Evaluate the starting dose for human studies. |

Subjects: Vaccine is studied in Cell culture & animals. Design: Toxicity and antibody response, challenge studies. Time: <1 year. The success to proceed is 33%.g Causes of a failure—vaccine toxic or ineffective immune response, underfunding. |

| Clinical Trial Authorization | Allow human experiments (Application for IND) | The basis for authorization-Manufacturing steps & analytical methods for vaccine & placebo production, Availability and stability of vaccine & placebo during clinical studies. Time: within 30 days. |

| Phase Ic | First-in-human testing. Vaccine safety and immune response. | Subjects: Healthy volunteers (20-100). Site: vicinity of the tertiary care for close observation. Design: Escalation study to avoid severe adverse effects (SAEs). Monitor: Health outcomes (clinical and laboratory) and antibody production Time: a few mon. Success rate to proceed 66%.g Caution: Follow strict go/no-go criteria based on safety and immunity data |

| Phase IIc,d,e |

Vaccine safety, immunity/partial efficacy. Dose–response, schedule, and method of delivery |

Subjects: Healthy volunteers (hundreds), may include a diverse set of humans. Site: Community-based (university, colleges, schools, etc). Study design: Studied against a placebo, adjuvant, or established vaccine. Dose: Test vaccine in different schedules and a diverse set of humans. Monitor: Health outcomes (clinical and laboratory) and antibody response Partial efficacy data can be procured under circumstances. Time: 2yr. Success rate to proceed 30%. g |

| Phase IIIc | Vaccine efficacy and safetya | Subjects: Target population (thousands). Site: Field conditions similar to future vaccine use. Design: Vaccine randomized vis-a-vis a placebo, adjuvant, or an established vaccine. Monitor: Vaccine efficacy and SAE. Time: Many years. Success rate to proceed 70%.g |

| Biologic License Application | Marketing of vaccinef | The basis for approval-The vaccine is safe and effective in humans (Efficacy >95%). Capacity to produce in bulk for market demand. Affordable cost to a susceptible population. |

| Phase IV | Postmarketing surveillance | Spontaneous reporting (Adverse Events Reporting System). Monitor: Data collected by the end-users. |

This figure includes vaccines that are abandoned during the development process.

Vaccine Efficacy (VE) = (Iu-Iv/Iu) ×100= (1-Iv/Iu) ×100= (1-RR) ×100%. (Iv = incidence in vaccine group, Iu = incidence in unvaccinated group, RR = relative risk).

Platform technology has shortened time for vaccine production from years to days.

Clinical trials are rate-limiting in vaccine marketing.

Human challenge studies can be done in phase IIa in certain diseases where the challenge is ethical.

Phase IIb studies can provide data on efficacy in regions with a high prevalence of the disease in the community.

The cost of developing a vaccine from research and discovery to product registration is around US$ 1 Billion.

The overall success rate for vaccine development is around 15%.

A Race Against Time

Given the above several facts about vaccine development are glaring. Vaccine development from the exploratory stage to marketing is a lengthy process and generally takes between 5 and 10 years. For the COVID-19 vaccine, this period is being substantially compressed by the use of modern platform technology to develop the candidate vaccine (preclinical stage) and fast authorization by regulatory agencies for clinical trials. It took Moderna Inc. (American biotechnology company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts) only 42 days from sequence analysis of the virus to create a new generation vaccine (mRNA-1273) at the Company's cGMP facility. This would have normally taken more than 2 years period without platform technology to develop such a vaccine. However, clinical trials that follow a unique protocol are “rate-limiting” and “time-consuming”. Here also, to respond to the pandemic, the investigators are exploring innovative methods of data collection. Many developers are running clinical trials in parallel (phase I-II) to shorten the time for approval. Some have started collecting data on efficacy from phase II itself (IIb). There is an intense debate on whether challenge studies are ethical in COVID-19, assessing the risk to a healthy volunteer.56 If allowed and done, efficacy data on the COVID-19 vaccine shall be available in a matter of weeks rather than years. However, it will be dangerous to grant authorization without proof that the COVID-19 vaccine is immunogenic, effective, and safe.

Success Rate

The second item which needs consideration is the success rate of vaccine development from clinical trial authorization to License. Typically, this rate was <10% during the period 2000-2010. A 2016 study showed that around 20% of vaccine clinical trials make up from phase I to license.57 Of the 37 vaccines developed for the Ebola virus, only one was licensed based on efficacy and safety in the phase II trial. In the COVID-19 vaccine landscape, investigators have introduced a few new generation vaccines based on nucleic acid technology. Such vaccine technology is not in clinical practice against any infectious disease, and experts believe the success rate of such a vaccine to get licensed is not more than 5%.58,59

Costs

It has also to be considered that vaccine development is a high cost and high-risk involvement.59 Apart from competition between other major vaccine manufacturers, the cost of developing a single new vaccine against an infectious disease exceeds US $1 billion. The figure includes vaccines that are abandoned during the development process. Here, given impending human catastrophe and global devastation, several Governmental and nongovernmental agencies have supported institutions with sufficient funds. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) is a foundation that takes donations from public, private, philanthropic, and civil society organizations to finance independent research projects to develop vaccines against emerging infectious diseases. In March 2020, CEPI announced the US $ 2 billion to accelerate the development of the COVID-19 vaccine.60 Similarly, the US Government has agreed to pay $ 483 million to Moderna Inc. to develop the COVID-19 vaccine.61 The Canadian Government has initiated a CA $ 1.3 billion innovation fund for vaccine research and development through 2022.62

Platform Technology—A Gamechanger

The technology behind the development of vaccines in R&D has seen a transformation in the recent past. Over the year's candidate vaccines were made through traditional methods of biotechnology. Because of this making of a prototype vaccine took between 2 and 5 years and was limited to a few types of vaccines. It needed the availability of cutting-edge research facilities to work with the infectious agent and was possible only in few laboratories over the globe.58,59 Recently, platform technology has been employed in developing candidate vaccines.63,64 Platform technology offers several advantages in the development of vaccines which include automation, speed, ability to develop several prototype vaccines from the single system, cost-effectiveness, and developing among other complex mRNA vaccines with ease. It is believed that the mRNA-based vaccine developed by platform technology appears particularly promising in terms of ease of manufacture, adaptability to various targets, and biological delivery.65 As candidate vaccines can be developed in a matter of days rather than years, the platform technology has been termed as a single game-changer in the fight against epidemics or pandemics caused by new agents.66, 67, 68

COVID-19 Vaccine Platform Technologies

Researches are trialing several designs to develop candidate vaccines against COVID-19. Overall, 8 types of designs, under 4 broad groups have been tried to develop candidate COVID-19 vaccines (Table 2). Each vaccine design has a subtle structure, advantages, and disadvantages in immunogenicity, safety, ease of use, and effectiveness (Figure 1).29,69,70

Table 2.

Various Types of VVaccines Categorized by the Antigen Used in the Preparation.

| Vaccine | Structure | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Virus vaccines | ||

| Attenuated | Virus is weakened by passing through animal or human cells, until genome mutates and unable to cause disease | Inexpensive, rapid production Live vaccine, small chance of disease, replicates Needs cold chain Induces strong long-lasting T cell & B cell immune response Good for attaining herd immunity in the community Vaccine in use: BCG, Smallpox, MMR, Chickenpox, Rotavirus, Yellow fever, Polio (OPV) |

| Inactivated | Virus inactivated with formaldehyde or heat | Noninfectious, cannot cause disease. Can be freeze dried, no cold chain needed Needs adjuvant for immune response Can cause TH2 cell skewed response (ADE) Vaccines in use: Polio (IPV), HAV, Rabies. Hepatitis A, rabies, Flu. Candidate COVID-19 vaccine: PiCoVacc (Sinovac Biotech) |

| Nucleic acid vaccines | ||

| DNA vaccine | Gene encoding antigenic components (Spike protein) | Safe, cannot cause disease. Yet unproven in practice. Can cause TH2 cell skewed response (ADE) when used alone. Highly immunogenic, generate high titre neutralizing antibodies when given with inactivated vaccine. Electroporation device needed for delivery Candidate COVID-19 vaccine: INO-4800 (Inovio Pharma, CEPI, Korean Institute of Health, International Vaccine Institute) |

| RNA vaccine | mRNA vaccine for spike protein, with a lipid coat | Safe, cannot cause disease, Can cause TH2 cell skewed response, Yet unproven in practice Candidate COVID-19 vaccine: mRNA-1273 (Moderna/NIAID). BNT162 (a1, b1, b2, c2) (BioNTech/Fosun Pharma/Pfizer) |

| Viral vector vaccines | ||

| Replicating | An unrelated virus like measles or adenovirus is genetically engineered to encode the gene of interest | Safe, Induces strong T cell and B cell response, Vaccines in use: Hepatitis B, pertussis, pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae, HPV, Hib (Haemophilus influenza) |

| Nonreplicating | An unrelated virus like measles or adenovirus (with inactive gene) is genetically engineered to encode the gene of interest | Safe, Need booster shots to induce long-term immunity, No vaccine licensed yet Candidate COVID vaccine: Ad5-nCoV (CanSino Biological Inc./Beijing Institute of Biotechnology). ChAdOx1-nCoV-19 (University of Oxford) |

| Protein-based vaccines | ||

| Subunit | Antigenic components (spike protein) are generated in vitro and harvested for vaccine | Safe, Need multiple dosing and adjuvants |

| Virus-like particles | Empty virus shells with no genetic material | Safe, Strong immune response, Difficult to manufacture |

ADE, antibody-dependent enhancement.

Live-attenuated vaccine is developed by the process in which the live virus is passed through animal or human cells until genome mutates and is unable to cause disease. The weekend virus replicates like a natural infection and causes strong T cell and B cell immune response, which is long-lasting. Such vaccines are good to attain herd immunity in the population and block transmission of disease. However, there is a small chance of reversion of mutation to virulence and the occurrence of disease. Besides, such vaccines need a cold chain for distribution to the community. Examples of such vaccines are BCG, smallpox, MMR (Measles, Mumps, & Rubella), Rotavirus, Poliomyelitis (OPV), etc. Inactivated vaccines are treated with formaldehyde or heat, and as the virus is killed, such vaccines are safe and cannot cause disease. However, such vaccines do not replicate, cause a suboptimum immune response, and need repeated dosing and adjuvants to enhance immunity. ADE has been reported in such vaccines, and to avoid this, we need to maintain the structure of epitopes on the surface antigen during inactivation. Examples of such vaccines include poliomyelitis (IPV), HAV, rabies, etc.

Nucleic acid vaccines are the new generation vaccines, made available by modern technology. A DNA vaccine is made by inserting DNA encoding the antigen from the pathogen into plasmid DNA. RNA vaccines employ lipid-coated mRNA of the SARS-CoV-2 which expresses Spike protein. The expressed proteins are presented BY MHC class I to CD+ 8 T cells and inducing a strong T cell response. These vaccines are safe, easy to manufacture by the platform technology, and maybe gamechanger in the future of vaccines. As of today, there are no nucleic acid vaccines in clinical practice.

Recombinant vector virus vaccines are producing through recombinant DNA technology. This involves inserting the DNA, encoding an antigen from the pathogen into bacteria or virus vectors, expressing the antigen in these cells, and then purifying it from them.67 During vaccination, the vector replicates, and along with it, the encoded DNA is expressed and processed, giving robust T cell and B cell immune response. Vectors may be bacteria such as E. coli or viruses such as Adenovirus or poxvirus. Classical examples of vector vaccines are HBV, HPV, Whooping cough, Hib, and Meningococcus.

Subunit vaccines composed of purified antigen peptides of viruses like Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 and are safe to use. Such an antigen is directly presented to MCH class II and often does not generate a robust cytotoxic T cell response (MHC class I dependent). Thus, such vaccines need repeated dosing and adjuvants to enhance immunity. Virus-like particles are made from empty virus particles without genetic material. Such vaccines are safe and immunogenic, however, are difficult to manufacture.

COVID-19 Vaccines Landscape

There has been unprecedented fast track path taken in R&D by the World community for developing candidate COVID-19 vaccines. As of 5 May 2020, the global COVID-19 vaccine R&D includes 108 candidate vaccines.71 The platform for 108 candidate vaccines are diverse and include live-attenuated vaccine (n = 3), inactivated vaccine (n = 7), DNA vaccine (n = 10), RNA vaccine (n = 16), replicating viral vector vaccine (n = 12), nonreplicating viral vector vaccine (n = 15), protein subunit vaccine (n = 36), virus-like particles (n = 6), and unknown (n = 3). These platforms have been used in the past in 45 instances against a variety of infectious pathogens (Table 2).

COVID-19 Candidate Vaccines

Till now, several candidate vaccines have completed the exploratory and preclinical stage, obtained Clinical Trial Authorization, and initiated recruitment of volunteers for clinical trials.72 Of these, 6 candidate vaccines stand at the forefront of clinical trials (Table 3).

Table 3.

The Candidate COVID-19 Vaccines in Clinical Evaluation.

| Name of vaccine (Developer) | Candidate vaccine (Platform) | Location | Current stage (participants) | Trial quality | Status (completion date) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad5-nCoV (CanSino Biological Inc./Beijing Institute of Biotechnology) | Recombinant Adenovirus Type 5 Vector (Nonreplicating Viral Vector) | China | Phase II (500) | Safety & Immune response; Randomized double-blind placebo controlled | Recruiting (Jan 2021). |

| Phase I (108) | Safety; 3 different doses | Completed. | |||

| mRNA-1273 (Moderna/NIAID) | Lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated mRNA (RNA) | USA | Phase II (IND submission) | – | – |

| Phase I45 | Safety & immune response; 3 arms (dose 25, 100, 250 mcg) | Recruiting (June 2021). | |||

| PiCoVacc (Sinovac Biotech) | Inactivated SARS-CoV + Alum (Inactivated) | China | Phase I-II (144) | Randomized double-blind single center placebo-controlled | Recruiting (Dec 2020) |

| ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (University of Oxford) | Adenovirus vector (Nonreplicating Viral Vector) | UK | Phase I-II (510) | Single-blinded randomized placebo controlled multicenter safety and efficacy. | Recruiting (May 2021) |

|

BNT162 (a1, b1, b2, c2) (BioNTech/Fosun Pharma/Pfizer) |

Lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated—mRNA (RNA) | Germany | Phase I-II (196) | Safety & immune response; 4 vaccines, dose-escalation, parallel cohort | Recruiting (May 2021) |

| INO-4800 (Inovio Pharmaceuticals, CEPI, Korean Institute of Health, International Vaccine Institute) | DNA plasmid vaccine with electroporation (DNA) | USA, South Korea | Planning phase II-III trials. | Safety and efficacy trial | – |

| Phase I-II40 | Phase I in South Korea in parallel with phase I in the USA, completed phase I using 2 doses spaced 4 weeks apart. | Results June 2020 |

Ad5-nCoV from CanSino Biologicals Inc. is a recombinant vaccine using Adenovirus-vector. CanSino has an adenovirus-vector vaccine for Ebola (Ad5-EBOV) that is in phase II trials. Phase I trial has been completed on 108 volunteers; however, results have not been disclosed as of today. At present phase II trials are underway, and CanSino plans to enroll 500 volunteers to evaluate vaccine safety and immunogenicity.73,74

mRNA-1273 from Moderna is a lipid encapsulated mRNA vaccine and is undergoing safety and immune response phase I trial in Seattle. The company has filed for an IND to go for parallel phase II trials.61,75

PiCoVacc from Sinovac Biotech is an inactivated virus vaccine and is undergoing parallel phase I-II trials planned on 144 volunteers. Sinovac has partnered with US-based Dynavax. The vaccine produced neutralizing antibodies in mice, rats, and rhesus monkey which are protective in challenge experiments.47,76

ChAdOx1 from the University of Oxford is an adenovirus vector-based vaccine and plans to run parallel phase I-II trials on 510 volunteers for safety and efficacy. The Oxford group has experience with candidate vaccine for MERS-CoV (ChAdOx-MERS) and has undergone a successful phase I trial for safety. The group is pushing ahead with an aggressive clinical plan and is talking of an emergency-use vaccine ready in September 2020.77, 78, 79

BNT162 (a1, b1, b2, c2) from BioNTech is another lipid nanoparticle mRNA vaccine and has received clearance from regulatory authority form Germany to the start of phase I-II trials on 196 volunteers. The trial is dose escalation design (1–100 mcg) using 4 vaccine subtypes (a1, b1, b2, and c2). The developers have claimed to have an emergency-use vaccine by September 2020.80

INO-4800 from Inovio is a DNA plasmid vaccine. The company has experience with such platforms with candidate vaccines for MERS and SARS. The vaccine needs a delivery system through electroporation, which shall add to the cost of the vaccine. Phase I trial using 2 doses spaced 4 weeks apart has been completed, and results shall be available in June 2020. Inovio is planning to start phase II-III trials soon.81

Numerous developers at present in the preclinical stage of vaccine development have indicated to procure “Clinical Trial Authorization” by the regulatory agencies and initiate “First-in-human vaccine” testing.

COVID-19 vaccine in the middle of a pandemic

A Race Against Time in the Middle of Death and Devastation

COVID-19 vaccine development has thrown major challenges in vaccine R&D.82 The world is facing a major health catastrophe and economic devastation, and one of the definitive solutions is to have an effective and safe vaccine in the shortest possible time. The global vaccine R&D efforts have been unprecedented in history. The virus causing COVID-19 has been sequenced in a few weeks. Ordinarily, it has taken from 5 to 10 years to clone, and sequence a virus from the time the disease is discovered. There has been a tremendous race against time to develop candidate vaccine in a matter of few weeks, and as of now, 10 candidate vaccines have entered phase I-II clinical trials. It has taken us from 5 to 10 years in the history of vaccine development against other infectious agents to reach a stage as we are now with the COVID-19 vaccine. However, clinical trials as are undergoing now will be the greatest limiting factor, as these need time to acquire human data. Normally phase I, II, and III trials to be done on humans are completed between 2 and 5 years and sometimes more. This is necessary for qualifying a vaccine to be safe, immunogenic, and efficacious. As of today, candidate vaccines are undergoing phase I or parallel I-II studies and shall take several months for acquiring these data to start phase III trials. Phase III trial once initiated can take as long as 2 years. To compress the period, vaccine developers are involved in adopting parallel and adaptive development phases (I-II) to acquire safety and immunogenicity data as soon as possible to initiate phase III trials. By any imagination, these data shall not be available by early 2021 for any vaccine for regulatory authorities to allow vaccine marketing. COVID-19 vaccines could be available for human use earlier if innovative methods of clinical trials and regulatory processes are employed. One such is the use of “Challenge studies” to testify vaccine efficacy.56 Here, following proof of safety and immunogenicity in phase I-II trials, controlled “challenge studies” which can be completed in a matter of weeks are done to confirm vaccine efficacy. Challenge studies have been done in the past in other infectious diseases namely influenza, typhoid fever, cholera, and malaria. Whether “challenge studies” are ethical in COVID-19, considering the risk to the volunteer is a matter of debate before the vaccine developers.83 Also, regularity authorities can use innovative procedures to allow guarded emergency use of a vaccine. This would need careful consideration of interventional animal safety data and data of safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy acquired from phase I-II trials. With all this, vaccine developers have to be ready to scale manufacturing capacity to massive demands once the product is allowed for marketing.25

No “Quick Fix” and “Short Cuts” Please

However, concerns are raised about a rush to deploy a COVID-19 vaccine. Applying “quick fix” and “short cuts” can lead to errors with disastrous consequences.84 What regulators have to worry about is the atmosphere of hype about the COVID-19 vaccine? Public claims about breakthrough research based on poorly conducted studies or data collected through fraud is a real possibility. All data which form the basis of any findings need to be scrutinized and should be confirmed by other investigators. Relaxion on regulatory principles based on political pressure and goodwill needs to be resisted, and one needs to protect the interests of volunteers who are a part of such experiments.85 Finally, vaccine development is a risky process, and one critical issue in the COVID-19 vaccine would be the occurrence of ADE which may be disastrous for those receiving the vaccine.49,50 Regulators have to take all precautions to discourage candidate vaccines which may show such a phenomenon.

Contributions

All authors have contributed to this manuscript equally, and the final draft has been read and accepted by all authors.

Human and animal experiments

No human or animal experiments were done for the study.

Financial support

The work was financially supported by Dr. Khuroo's Medical Trust, a nonprofit organization that supports academic activities and helps poor and needy for treatment.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohammad S. Khuroo: Coceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Mohammad Khuroo: Software, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. Mehnaaz S. Khuroo: Writing - original draft. Ahmad A. Sofi: Software, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. Naira S. Khuroo: Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Gates B. Responding to Covid-19 - a once-in-a-century pandemic? N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. Naming the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and the Virus that Causes it.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(COVID-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it [updated March 11. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 [updated March 11. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anonymous . Dadax Limited.; 2020. Worldometer. Covid-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. The United States.https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?utm_campaign=homeAdvegas1? [updated May 4th, 2020. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legido-Quigley H., Asgari N., Teo Y.Y. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395:848–850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arun T.K. Economic Times; 2020. Coronavirus: is there an alternative to lockdowns? 2020 April 20th. [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO . 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public Geneva, Switzerland. [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO . 2020. Updated WHO Recommendations for International Traffic in Relation to the COVID-19 Outbreak.https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/updated-who-recommendations-for-international-traffic-in-relation-to-covid-19-outbreak Geneva, Switzerland. [Feb 29th 2020.]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar N. India Times; 2020. Lockdown 2.0: how it impacts the ailing economy. April 16th. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson R. COVID-19 disrupts vaccine delivery. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30304-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shoenfeld Y. Corona (COVID-19) time musings: our involvement in COVID-19 pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and vaccine planning. Autoimmun Rev. 2020:102538. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebrahim S.H., Ahmed Q.A., Gozzer E., Schlagenhauf P., Memish Z.A. Covid-19 and community mitigation strategies in a pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1066. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai M.M., Cavanagh D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 1997;48:1–100. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham R.L., Donaldson E.F., Baric R.S. A decade after SARS: strategies for controlling emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:836–848. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zumla A.I., Memish Z.A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: epidemic potential or a storm in a teacup? Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1243–1248. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00227213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yong C.Y., Ong H.K., Yeap S.K., Ho K.L., Tan W.S. Recent advances in the vaccine development against Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1781. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shereen M.A., Khan S., Kazmi A., Bashir N., Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res. 2020;24:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NIH . National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Bethesda, MD, USA: 2020. NIH Clinical Trial Shows Remdesivir Accelerates Recovery from Advanced COVID-19.https://www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/nih-clinical-trial-shows-remdesivir-accelerates-recovery-advanced-covid-19 [updated April 29th, 2020. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Yea. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. https://doiorg/101016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9 published online April 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rathi S., Ish P., Kalantri A., Kalantri S. Hydroxychloroquine prophylaxis for COVID-19 contacts in India. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30313-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32311324 PMC7164849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raoult D., Hsueh P.R., Stefani S., Rolain J.M. COVID-19 therapeutic and prevention. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020:105937. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khuroo M., Sofi A.A., Khuroo M. 2020. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine IN coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). FACTS, fiction & the hype. A critical appraisal...https://doiorg/106084/m9figshare12177117v1. 2020 figshare Preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gates B. 2020. The vaccine race, explained. What You Need to Know about the COVID-19 Vaccine GatsNotes the Blog of Bill Gates.https://www.gatesnotes.com/Health/What-you-need-to-know-about-the-COVID-19-vaccine Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guarascio F.U.N. Reuters Health; Brussels: 2020. Calls for the COVID Vaccine, Treatment Available for All.https://in.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-eu-virus-un/u-n-calls-for-covid-vaccine-treatment-available-for-all-idINKBN22G1MZ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dyer O. Covid-19: trump sought to buy vaccine developers exclusively for the US, say German officials. BMJ. 2020;368:m1100. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anonymous . The Dept of Health; July 20, 2010. Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Australian Government.https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anonymous . Centre for Diseases Control and Prevention; 2020. Vaccines for Your Children. Diseases You Almost Forgot about (Thanks to Vaccines)https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/parents/diseases/forgot-14-diseases.html Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aryal S. 2020. Vaccines-introduction and Types with Examples Online Microbiology Notes by Sagar Aryal.https://microbenotes.com/author/sagararyalnepal/ March 29, 2018. Updated April 9. [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clem A.S. Fundamentals of vaccine immunology. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011;3:73–78. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.77299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Payne S. Academic Press; 2017. Chapter 6. Immunity and Resistance to Viruses. Viruses: From Understanding to Investigation; pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siegrist C.-A. Chapter 2. Vaccine immunology. In: Plotkin S., Orenstein W., Offit P., Edwards K.M., editors. Plotkin's Vaccines. 7th. ed. Imprint: Elsevier; The United States: 2017. pp. 1–26. June 6th. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esser M.T., Marchese R.D., Kierstead L.S. Memory T cells and vaccines. Vaccine. 2003;21:419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Randal J. Hepatitis C vaccine hampered by viral complexity, many technical restraints. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:906–908. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.11.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alcorn K. 2020. The Search for an HIV Prevention Vaccine.http://www.aidsmap.com/about-hiv/search-hiv-prevention-vaccine [updated Feb. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bankwitz D., Steinmann E., Bitzegeio J. Hepatitis C virus hypervariable region 1 modulates receptor interactions, conceals the CD81 binding site, and protects conserved neutralizing epitopes. J Virol. 2010;84:5751–5763. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Rose R., Kent S.J., Ranasinghe C. In: Chapter 12 - Prime-Boost Vaccination: Impact on the HIV-1 Vaccine Field. Singh M., Salnikova M., editors. Elsevier Inc.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duverlie G., Wychowski C. Cell culture systems for the hepatitis C virus. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2442–2445. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lv Dorp, Aeman M., Richard D., Shaw L.P., Ford C.F., Ormond L. Emergence of genomic diversity and recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed S.F., Quadeer A.A., McKay M.R. Preliminary identification of potential vaccine targets for the COVID-19 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on SARS-CoV immunological studies. Viruses. 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/v12030254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thevarajan I., Nguyen T.H.O., Koutsakos M. Breadth of concomitant immune responses prior to patient recovery: a case report of non-severe COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:453–455. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun J., Loyal L., Frentsch M., Wendisch D., Georg P., al e. medRxiv; April 22, 2020. Presence of SARS-CoV-2-reactive T cells in 1 COVID-19 patient and healthy donors. preprint. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y., Li L. vol. 20. 2020. p. 515.www.thelancet.com/infection (SARS-CoV-2: virus dynamics and host response). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Russel A. Global News; 2020. Can You Catch Coronavirus Twice? South Korea Reports 91 Recovered Patients Tested Positive.https://globalnews.ca/news/6805414/coronavirus-south-korea-reinfection-canada/ [updated April 10th, 2020. April 10th. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guzman J. The Hill; 2020. No Evidence of Coronavirus Reinfections, South Korean Researchers Say. South Korea's Infectious Disease Experts Said Thursday Reports of Coronavirus Reinfection Were Likely Testing Errors.https://thehill.com/changing-america/well-being/medical-advances/495646-no-evidence-of-coronavirus-reinfections-south Changing America. [updated May 1, 2020. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bao L., Deng W., Gao H. Reinfection could not occur in SARS-CoV-2 infected rhesus macaques. bioRxiy. 2020 doi: 10.1101/20200313990226. May 5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao Q., Bao L., Mao H. Rapid development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abc1932. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32376603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roper R.L., Rehm K.E. SARS vaccines: where are we? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8:887–898. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peeples L. News Feature: avoiding pitfalls in the pursuit of a COVID-19 vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:8218–8221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005456117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hotez P.J., Corry D.B., Bottazzi M.E. COVID-19 vaccine design: the Janus face of immune enhancement. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0323-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32346094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Alwis R., Chen S., Gan E.S., Ooi E.E. Impact of immune enhancement on Covid-19 polyclonal hyperimmune globulin therapy and vaccine development. EBioMedicine. 2020;55:102768. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smatti M.K., Al Thani A.A., Yassine H.M. Viral-induced enhanced disease illness. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2991. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.WHO . 2017. Guidelines on Clinical Evaluation of Vaccines: Regulatory Expectations. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 1004, 2017. Replacement of Annex 1 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 924 Geneva, Switzerland.https://www.who.int/biologicals/expert_committee/WHO_TRS_1004_web_Annex_9.pdf?ua=1 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 54.(CHMP). CoHMP . 2018. Guideline on clinical evaluation of vaccines. EMEA/CHMP/VWP/164653/05 Rev. 1.https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/draft-guideline-clinical-evaluation-vaccines-revision-1_en.pdf The United Kingdom. [updated April 26th. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 55.FDA. GUIDANCE DOCUMENT . Guidance for Industry; New Hampshire Ave, Silver Spring, MD, USA: 2011. General Principles for the Development of Vaccines to Protect against Global Infectious Diseases.da.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/general-principles-development-vaccines-protect-against-global-infectious-diseases updated DECEMBER 2011. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cioffi A. COVID-19: is everything appropriate to create an effective vaccine? J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa216. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32348489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.D'Amore T., Yang Y.-P. Advances and challenges in vaccine development and manufacture. BioProc Int. 2019 https://bioprocessintl.com/manufacturing/vaccines/advances-and-challenges-in-vaccine-development-and-manufacture/ September 21. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh K., Mehta S. The clinical development process for a novel preventive vaccine: an overview. J Postgrad Med. 2016;62:4–11. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.173187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Plotkin S., Robinson J.M., Cunningham G., Iqbal R., Larson S. The complexity and cost of vaccine manufacturing-An Overview. Vaccine. 2017;35:4064–4071. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thanh Le T., Andreadakis Z., Kumar A. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:305–306. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Langreth R. Bloomberg. Quint; 2020. Moderna Soars after $483 Million Covid-19 Agreement with U.S. Robert Langreth.https://www.bloombergquint.com/coronavirus-outbreak/moderna-snares-483-million-u-s-funding-for-covid-vaccine-tests [updated April 17th, 2020. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steenhuysen J., Eisler P., Martell A., Nebehay S. April 25, 2020. Race for coronavirus vaccine draws billions of dollars worldwide, with a focus on speed Global News.https://globalnews.ca/news/6868824/research-coronavirus-vaccine/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anonymous, Center News . Center for Health Security; 2019. Center for Health Security Report Reviews the Promise and Challenges of Vaccine Platform Technologies John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/newsroom/center-news/2019/2019-04-25-vaccine-platform.html updated April 25th. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilmott R.W. Saint Louis University school of medicine and vaccine center mobilize for COVID-19 pandemic. Mo Med. 2020;117:125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Amesh A. Adalja AA, Matthew Watson M, Anita Cicero A, Tom Inglesby T. Vaccine Platforms: State of the Field and Looming Challenges. John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Medicine. Centre for Health Security. Baltimore. MD. The USA. www.centerforhealthsecurity.org.

- 66.Adalja A.A. 2020. Powerful New Technologies Are Speeding the Development of a Coronavirus Vaccine. Leapsmag. Future Frontiers. Opinion Essay.https://leapsmag.com/powerful-new-technologies-are-speeding-the-development-of-a-coronavirus-vaccine/ updated March 2nd. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ewer K.J., Lambe T., Rollier C.S., Spencer A.J., Hill A.V., Dorrell L. Viral vectors as vaccine platforms: from immunogenicity to impact. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;41:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu S.C. Progress and concept for COVID-19 vaccine development. Biotechnol J. 2020 doi: 10.1002/biot.202000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Callaway E. The race for coronavirus vaccines: a graphical guide. Nature. 2020;580:576–577. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01221-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang L., Tian D., Liu W. Strategies for vaccine development of COVID-19. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao. 2020;36:593–604. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.200094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.WHO . May 5th, 2020. The Draft Landscape of COVID 19 Candidate Vaccines Geneva, Switzerland.https://www.who.int/who-documents-detail/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines updated May 5th, 2020. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lowe D. Science Translational Medicine; April 30, 2020. COVID-19. A Close Look at the Frontrunning Coronavirus Vaccines as of April 28 (Updated)https://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2020/04/23/a-close-look-at-the-frontrunning-coronavirus-vaccines-as-of-april-23 [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhu F. Jiangsu Province Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. CanSino Biologics' Ad5-nCoV the First COVID-19 Vaccine to Phase II Clinical Trials. TrialSiteNews.https://www.trialsitenews.com/cansino-biologics-ad5-ncov-the-first-covid-19-vaccine-to-phase-ii-clinical-trials/ updated April 19th. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 74.Anonymous . 2020. CanSino Bio Enrolls for Ph 2 Trial of COVID-19 Vaccine: BioSpectrum Asia Edition.https://www.biospectrumasia.com/news/37/15850/cansino-bio-enrols-for-ph-2-trial-of-ad5-ncov-vaccine-for-covid-19.html April 27. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 75.Terry M. Biospace; 2020. Moderna's COVID-19 Vaccine Clinical Trial Moves into 2nd Round of Dosing.https://www.biospace.com/article/moderna-vaccine-clinical-trial-moves-into-2nd-round-of-dosing/ updated April 23rd. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 76.Phelamei S. TIMESNOWNEWS.COM; 2020. China's First COVID-19 Vaccine Test Shows Success, Protects Indian Monkeys from Coronavirus.https://www.timesnownews.com/health/article/chinas-first-covid19-vaccine-test-shows-success-protects-indian-monkeys-from-coronavirus/588904 May 8th. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 77.Myupchar . 2020. Chadox1 by Oxford University Becomes 4th COVID-19 Vaccine to Enter Human Trials. Firstpost.https://www.firstpost.com/health/chadox1-by-oxford-university-becomes-4th-covid-19-vaccine-to-enter-human-trials-8291691.html updated April 23. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lane R. Sarah Gilbert: carving a path towards a COVID-19 vaccine. Lancet. 2020;395:1247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30796-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cohen J. Vaccine designers take first shots at COVID-19. Science. 2020;368:14–16. doi: 10.1126/science.368.6486.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alatovic J. Pfizer; 2020. Biontech and Pfizer announce completion of dosing for first cohort of phase 1/2 trial of COVID-19 vaccine candidates in Germany.https://investors.pfizer.com/investor-news/press-release-details/2020/BioNTech-and-Pfizer-announce-completion-of-dosing-for-first-cohort-of-Phase-1-2-trial-of-COVID-19-vaccine-candidates-in-Germany/default.aspx April 29. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 81.Richardson j. 2020. INOVIO Completes Enrollment in the Phase 1 U.S. Trial of INO-4800 for COVID-19 DNA Vaccine; Interim Results Expected in June. INOVIO.http://ir.inovio.com/news-releases/news-releases-details/2020/INOVIO-Completes-Enrollment-in-the-Phase-1-US-Trial-of-INO-4800-for-COVID-19-DNA-Vaccine-Interim-Results-Expected-in-June/default.aspx updated April 28th. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 82.Harrison E.A., Wu J.W. Vaccine confidence in the time of COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00634-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32318915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Callaway E. Should scientists infect healthy people with the coronavirus to test vaccines? Nature. 2020;580:17. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00927-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jiang S. Don't rush to deploy COVID-19 vaccines and drugs without sufficient safety guarantees. Nature. 2020;579:321. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00751-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Callaway E. April 22, 2020. Hundreds of people volunteer to be infected with coronavirus Nature.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32322034 Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

@mskhuroo

@mskhuroo