Abstract

Background

Patient interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10 responses early in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SaB) are associated with bacteremia duration and mortality. We hypothesized that these responses vary depending on antimicrobial therapy, with particular interest in whether the superiority of β-lactams links to key cytokine pathways.

Methods

Three medical centers included 59 patients with SaB (47 methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA], 12 methicillin-sensitive S. aureus [MSSA]) from 2015–2017. In the first 48 hours, patients were treated with either a β-lactam (n = 24), including oxacillin, cefazolin, or ceftaroline, or a glyco-/lipopeptide (n = 35), that is, vancomycin or daptomycin. Patient sera from days 1, 3, and 7 were assayed for IL-1β and IL-10 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

On presentation, IL-10 was elevated in mortality (P = .008) and persistent bacteremia (P = .034), while no difference occurred in IL-1β. Regarding treatment groups, IL-1β and IL-10 were similar prior to receiving antibiotic. Patients treated with β-lactam had higher IL-1β on days 3 (median +5.6 pg/mL; P = .007) and 7 (+10.9 pg/mL; P = .016). Ex vivo, addition of the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra to whole blood reduced staphylococcal killing, supporting an IL-1β functional significance in SaB clearance. β-lactam–treated patients had sharper declines in IL-10 than vancomycin or daptomycin –treated patients over 7 days.

Conclusions

These data underscore the importance of β-lactams for SaB, including consideration that the adjunctive role of β-lactams for MRSA in select patients helps elicit favorable host cytokine responses.

Keywords: cytokines, vancomycin, daptomycin, β-lactam, bacteremia

In this study, we evaluate the host cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10 response in the first 7 days of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SaB) treatment. β-lactam therapy resulted in a more favorable host response, underscoring the importance of using β-lactams whenever possible for SaB, including select methicillin-resistant S. aureus patients to help elicit favorable host cytokine response profiles.

Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of both community- and hospital-acquired bacteremia in the United States, with an estimated annual incidence of 15–40 cases per 100 000 individuals [1]. Despite diagnostic and therapeutic advances, mortality rates for patients with S. aureus bacteremia (SaB) remain as high as 15%–20% or even higher in patients with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infection [2, 3]. The sources of SaB are diverse, including skin and soft tissue infections, catheter-associated infections, prosthetic joint infections, and endocarditis, among others. Patient outcomes vary greatly depending on the source and spread of infection. Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of vancomycin or daptomycin to treat MRSA and a β-lactam, such as intravenous nafcillin, oxacillin, or cefazolin, to treat methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) infection [4]. Recent studies demonstrate that the addition of anti-staphylococcal β-lactams nafcillin/oxacillin/cefazolin to vancomycin or daptomycin therapy can reduce the duration of MRSA bacteremia [5, 6]. Similarly, use of ceftaroline combined with vancomycin or daptomycin shortens bacteremia and may reduce mortality in high-risk patients [5, 7].

Various cytokine responses have recently been linked to the severity of SaB infection. A robust interleukin (IL)-1β response, evidenced by elevated serum IL-1β concentrations at clinical presentation, is important for SaB clearance, wherein a failure of this response predisposes prolonged bacteremia (>4 days) [8, 9]. Staphylococcus aureus strains with reduced vancomycin susceptibility display attenuated virulence, greater intracellular persistence, and delayed bacteremia clearance linked to dampened proinflammatory cytokine production [10, 11]. Additional studies identified high intravascular S. aureus burden driving peptidoglycan-mediated IL-10 elevation as an independent risk factor for mortality [8, 12]. These select cytokine biomarkers, among others, may be valuable for identifying those patients at greatest risk for disease complications and guiding optimal antibiotic therapy [13].

To date, correlations of serum IL-1β and IL-10 levels to clinical outcome in SaB have been limited to serum cytokine values obtained at the time of clinical presentation, prior to initiation of antimicrobial therapy. This study was performed to evaluate host responses for these cytokines during the first 7 days of antimicrobial therapy. Specifically, we hypothesized that favorable clinical data corresponding to β-lactam therapy in SaB may be based, at least in part, on the ability of this drug class to promote a more vigorous immunostimulatory IL-1β response and/or an attenuation of the dysregulated immunosuppressive IL-10 response.

METHODS

Fifty-nine patients aged ≥18 years with SaB were identified retrospectively from 3 medical centers: UW Health (Madison, WI), Sharp Memorial Hospital (San Diego, CA), and Sharp Grossmont Hospital (La Mesa, CA). These patients included consecutive patients from a randomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02660346) of daptomycin plus ceftaroline vs standard of care [5] and an ongoing S. aureus bacteria immune response biorepository study at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Each institution ascertained health-sciences institutional review board protocol approval prior to study initiation [5, 8]. Patients had diverse sources of infection, including endovascular, extravascular, and catheter-related infections. All patients had complicated bacteremia as previously defined [4, 14]. Of these patients, 47 were infected with MRSA and 12 with MSSA.

Patients were selected and divided into 2 groups based on their initial treatment within 48 hours of clinical presentation. Patients in the glyco/lipopeptide group (n = 35) were treated with either vancomycin or daptomycin alone as the current standard of care for MRSA bacteremia. Patients in the β-lactam group (n = 24) were treated with oxacillin, nafcillin, cefazolin, or ceftaroline. Patients with MSSA bacteremia primarily received oxacillin, nafcillin, or cefazolin as the main treatment within 48 hours of presentation per standard protocol at each institution. Ceftaroline was used as part of a combination randomized study with daptomycin for MRSA, which was initiated on day 1 of patient presentation [5]. β-lactam–treated patients may have also received a glyco/lipopeptide at some point during their therapy, but β-lactam therapy was never discontinued. Conversely, patients in the glyco/lipopeptide group only received vancomycin or daptomycin throughout their entire course and never received a β-lactam at any point during therapy. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics for the 2 groups were compared using the t test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables depending on Gaussian distribution and the Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Statistical analysis was performed in Stata version 15 (Stata Corp LP).

Serum samples were obtained from patients with SaB on day 1 of presentation prior to treatment initiation and then on day 3 and day 7 of treatment. Sera were stored at −80°C until the time of analysis. IL-1β and IL-10 quantitative sandwich enzyme-linked immunoassays were performed on each collected sample in duplicate. The manufacturer’s (R&D Systems) recommended protocol was followed, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm. IL-1β and IL-10 concentrations for patients in the 2 treatment groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test in Prism (GraphPad Software, LLC). Significance was defined as P < .05.

For ex vivo whole blood studies, a single colony of MRSA TCH1516 was grown overnight to stationary phase in 5 mL Todd Hewitt (TH) broth, washed once in 5 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended to an optical density 600 nm wavelength (OD600) absorbency of 0.4 in PBS. Whole blood was collected in hirudin-containing tubes from 3 healthy donors. Blood for each condition was placed in a 2-mL siliconized Eppendorf tube and treated with carrier control (1.8 mg disodium EDTA, 82.2 sodium chloride, 19.3 mg sodium citrate, and 10.5 mg polysorbate 80 in 10 mL water, filtered with a 0.2-µm filter) or with 2500 ng/mL IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra for 30 minutes at 37°C with rotation. The anakinra concentration tested represents steady state concentrations achieved in plasma with 1–3 mg/kg recommended doses [15]. After preincubation, MRSA was added to a final inoculum of 1 × 106 colony forming units (CFU)/mL and incubated with rotation at 37°C for 2 hours. Samples were transferred to a 96-well round-bottom plate and sonicated in triplicate twice for 3 seconds with a 3-second pause in between. Each sample was then serially diluted, plated on TH agar plates, and incubated at 37°C overnight; bacterial CFUs were enumerated. Differences in bacterial counts obtained with anakinra vs without anakinra in blood killing assays from the 6 individual blood donors were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test.

RESULTS

Baseline patient and infection characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Patients who received β-lactam antibiotics (n = 24) did not differ significantly in terms of age, sex, comorbid conditions, source of infection, intensive care unit admission, or vancomycin susceptibility compared to those treated with glyco/lipopeptides only (n = 35). Though not statistically significant, we note that more patients in the β-lactam group had endovascular sources, while more in the glyco/lipopeptide group had a catheter-associated source of bacteremia. Also, the β-lactam group trended toward higher white blood cell counts at presentation (P = .073), but other inflammation or disease severity metrics including C-reactive protein and Pitt bacteremia score were comparable between the 2 groups. More patients in the glyco/lipopeptide group had MRSA (P = .012), but still more than half of the patients who received β-lactams had MRSA. Hospital length of stay was 1.5 days shorter on average in the β-lactam group (P = .442).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Infection Characteristics

| Variablea | Glyco/Lipopeptide | β-Lactam | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 35 | n = 24 | ||

| Age, years | 61.1 ± 3.1 | 60.4 ± 2.9 | .891 |

| Male | 23 (34) | 15 (62.5) | >.999 |

| Source | … | … | >.138 |

| Endovascular | 10 (28.6) | 9 (37.5) | … |

| Secondary | 21 (60) | 15 (62.5) | … |

| Catheter | 4 (11.4) | 0 | … |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 33 (94.2) | 14 (58.3) | .012 |

| Serum creatinine at presentation, mg/dL | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | .900 |

| Complicated bacteremiac | 35 (100) | 24 (100) | >.999 |

| White blood cell count at presentation, 103 cells/µL | 15.3 ± 1.3 | 19.4 ± 1.9 | .073 |

| Platelet count at presentation, 103 cells/µL | 230.4 ± 23.4 | 249.9 ± 41.8 | .665 |

| C-reactive protein at presentation,d mg/L | 122.0 [15.0–340.6] | 124.9 [10–304.5] | .765 |

| Vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration, mg/L | 1.0 | 1.0 | .396 |

| Pitt bacteremia scored | 1 [0–8] | 1 [0–8] | .808 |

| Comorbidities | … | … | >.530 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (45.7) | 10 (41.7) | … |

| Liver disease | 9 (25.7) | 4 (16.7) | … |

| Immunocompromised | 2 (5.7) | 2 (8.3) | … |

| End-stage renal disease | 6 (17.1) | 3 (12.5) | … |

| Patient location at index culture | … | … | … |

| Intensive care unit | 3 (8.5) | 3 (12.5) | .679 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 12.4 ± 1.4 | 10.9 ± 0.8 | .442 |

| Duration of bacteremia, daysc | 2 [1–11] | 2 [1–9] | … |

| In-hospital mortality | 6 (17.1) | 3 (12.5) | … |

a Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables unless otherwise noted.

b The t test, Mann-Whitney U test, or Fisher exact test was used for analysis for the appropriate data type.

c Defined as patients with positive blood culture results who do not meet the following criteria for uncomplicated bacteremia: exclusion of endocarditis, no implanted prostheses, follow-up blood cultures performed on specimens obtained 2–4 days after the initial set that do not grow Staphylococcus aureus, defervescence within 72 hours of initiating effective therapy, and no evidence of metastatic sites of infection.

d Median [range].

Table 2 displays the antibiotic treatments initiated within 48 hours of patient presentation. The majority of patients in the glyco/lipopeptide group received vancomycin (80%), while the others received daptomycin. Patients in the β-lactam group received ceftaroline combined with daptomycin (58.3%), while others received oxacillin or cefazolin alone or oxacillin combined with vancomycin. All of these therapies were maintained for at least 14 days of treatment with the exception of 2 patients who initially received oxacillin plus vancomycin. These patients had definitive MSSA, and they were deescalated to oxacillin alone as the β-lactam therapy for full bacteremia treatment duration.

Table 2.

Antibiotic Therapy Initiated Within 48 Hours of Presentation

| Antibiotic | Glyco/Lipopeptide | β-Lactam |

|---|---|---|

| n = 35 | n = 24 | |

| Vancomycin | 28 | ... |

| Daptomycin | 7 | ... |

| Oxacillin | ... | 6 |

| Cefazolin | ... | 2 |

| Vancomycin plus oxacillina | … | 2 |

| Daptomycin plus ceftaroline | ... | 14 |

a Vancomycin was discontinued after 48 hours due to definitive methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, and oxacillin was continued for the duration of treatment of bacteremia.

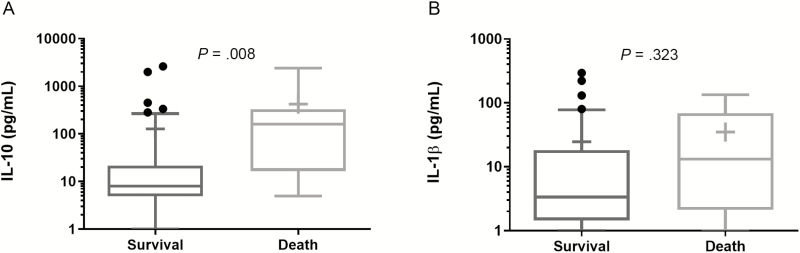

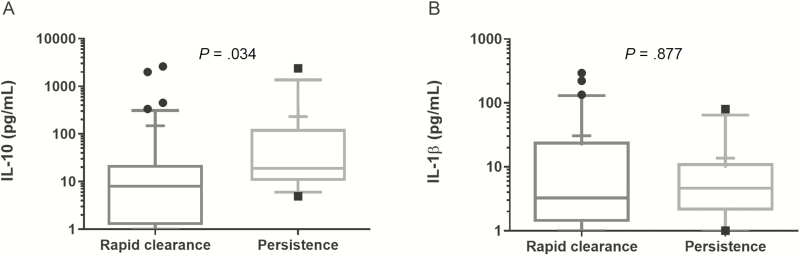

Consistent with prior data, patients who died in both groups had higher IL-10 serum concentrations at day 1 of presentation compared to survivors (P = .008) and no differences in median IL-1β concentration (Figure 1). For bacteremia >4 days duration, IL-10 was also higher than in patients with rapid bacteremia clearance (P = .034), with no observed difference in IL-1β (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

(A) IL-10 and (B) IL-1β concentrations in patient sera on day 1 of presentation compared by outcome of 30-Day survival or mortality. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. Median (line) and mean (+). Abbreviation: IL, interleukin.

Figure 2.

(A) IL-10 and (B) IL-1β concentrations in patient sera on day 1 of presentation compared by outcome of rapid bacteremia clearance (≤4 days) or persistent bacteremia (>4 days). The Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. Median (line) and mean (+). Abbreviation: IL, interleukin.

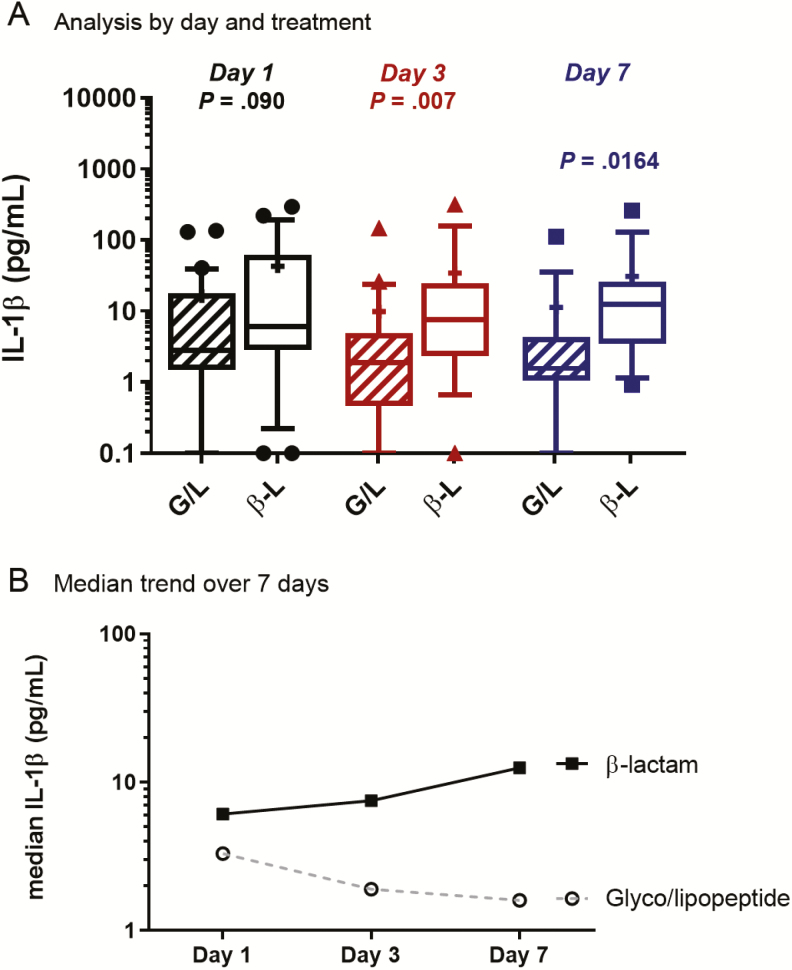

All SaB patients had serum samples collected on day 1 of hospital presentation and then on days 3 and 7 following initiation of therapy. There were no significant differences in IL-1β concentrations between the 2 groups at patient presentation (Figure 3). The median IL-1β concentration prior to antibiotic therapy was 6.1 pg/mL for β-lactam–treated patients and 2.8 pg/mL for glyco/lipopeptide-treated patients (P = .090). On day 3, patients treated with a β-lactam had significantly higher IL-1β levels than glyco/lipopeptide-treated patients (median, 7.5 pg/mL vs 1.9 pg/mL, respectively; P = .007). The difference between groups was also noted at day 7 of therapy, with β-lactam treatment resulting in higher IL-1β concentrations (median, 12.5 pg/mL) than glyco/lipopeptide treatment (1.6 pg/mL; P = .016). Comparatively per patient, β-lactam treatment resulted in 23% and 105% median increases in IL-1β at days 3 and 7, respectively, while glyco/lipopeptide treatment resulted in 32% and 44% reduction in IL-1β at those same time points following presentation (Figure 3). Of interest, this difference also occurred among MRSA patients treated with daptomycin plus ceftaroline vs daptomycin or vancomycin alone (Supplementary Figure 1A).

Figure 3.

IL-1β concentrations in patient sera treated with G/L or β-L antibiotic at day 1, day 3, and day 7 of therapy. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. Median (line) and mean (+). Abbreviations: B-L, β-lactam; G/L, glyco/lipopeptide; IL, interleukin.

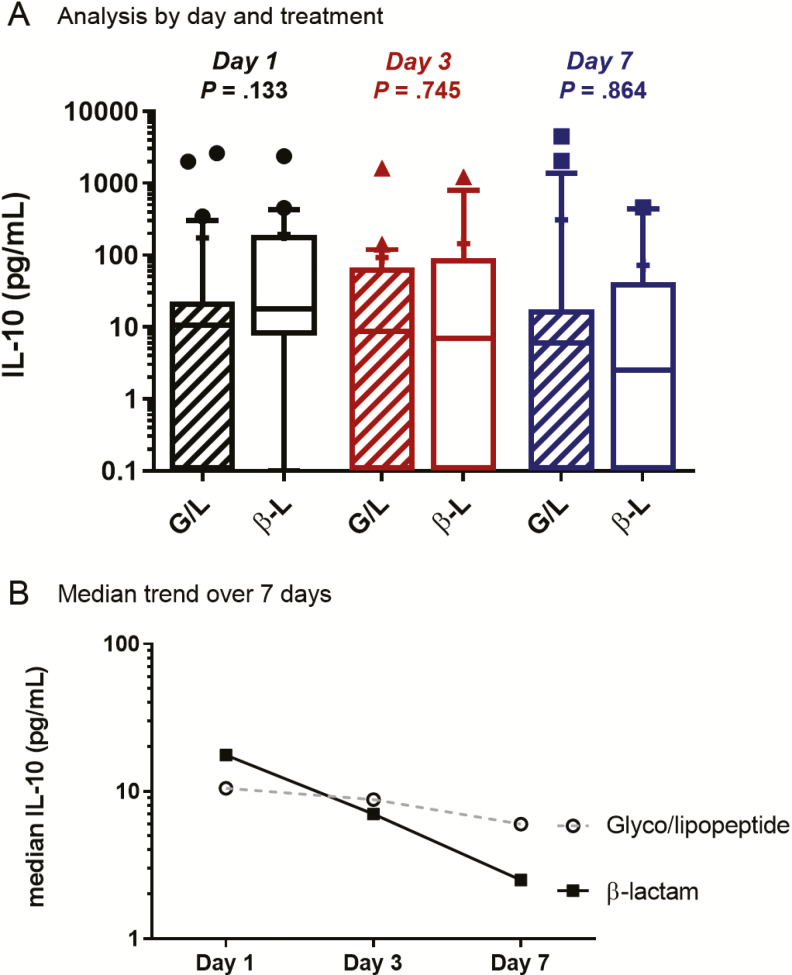

Patient sera were also analyzed for IL-10 concentrations at presentation (day 1) and on days 3 and 7 of treatment (Figure 4). On clinical presentation prior to antibiotic therapy, patients in the β-lactam–treated group had a median IL-10 level of 17.6 pg/mL, and patients treated with glyco/lipopeptides had a median IL-10 level of 10.5 pg/mL (P = .133). By day 3, IL-10 levels were lower in patients treated with β-lactams than in patients treated with glyco/lipopeptides (median, 7.0 pg/mL vs 8.8 pg/mL; P = .745). On day 7, IL-10 levels were also lower in patients treated with β-lactams (2.5 pg/mL vs 6.0 pg/mL for glyco/lipopeptides; P = .864). Overall, patients treated with β-lactam had a 60% reduction in IL-10 levels from day 1 to day 3 and a 64% reduction from day 3 to day 7 (86% total reduction in first 7 days). For glyco/lipopeptide-treated patients, reduction in IL-10 levels was only 16% from presentation to day 3 and 32% between day 3 and day 7 (42% overall; Figure 4). This trend was similar in the MRSA bacteremia patients treated with daptomycin plus ceftaroline vs vancomycin or daptomycin alone (Supplementary Figure 1B). Most notably, IL-10 concentrations in patients treated with daptomycin plus ceftaroline were within normal range (<5 pg/mL) at days 3 and 7 but they remained elevated with vancomycin or daptomycin monotherapy.

Figure 4.

IL-10 concentrations in patient sera treated with G/L or β-L antibiotic at day 1, day 3, and day 7 of therapy. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. Median (line) and mean (+). Abbreviations: B-L, β-lactam; G/L, glyco/lipopeptide; IL, interleukin.

IL-1β is a multipotent cytokine with diverse effects on host immune and inflammatory responses including the recruitment and activation of neutrophils [16]. Thus, elevated IL-1β responses in β-lactam therapy likely impact S. aureus clearance and clinical features in multiple ways. As a pilot experiment to determine whether IL-1β signaling could have short-term effects within the blood compartment relevant to S. aureus clearance, we assessed whole blood killing of MRSA with or without the addition of the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra. After MRSA infection of human whole blood from 6 healthy donors in the presence of either 2500 ng/mL anakinra or carrier control, significantly higher bacterial counts were seen in 4 of 6 of the anakinra-treated samples following 2 hours of incubation (Supplementary Figure 2). Collectively among the 6 donors, bacterial counts with anakinra were higher than without anakinra (median, 1.3 fold; range, 0.8–2.6).

DISCUSSION

Despite the availability of new antibiotics with activity against S. aureus, the standard of care for bacteremia overall has remained unchanged for the past several decades, with a preference for empiric β-lactam therapy for MSSA and vancomycin for MRSA. Daptomycin has emerged as a viable treatment alternative to vancomycin for MRSA [17] but it has been effectively relegated to second-line therapy for those patients who fail vancomycin or who have allergies to first-line agents. β-lactams are the treatment of choice for MSSA bacteremia, and recent evidence of their ability to synergize with vancomycin and daptomycin have made them an intriguing combination option for complex MRSA infections. Further, β-lactams enhance host innate immune recognition and killing, which may augment antibacterial activity. This study reveals that β-lactam therapy may result in a more favorable host cytokine response profile to S. aureus in the bloodstream.

Staphylococcus aureus possesses several mechanisms to establish colonization and infection by subverting human innate immune recognition. Given the key role of inflammasome activation and IL-1β signaling for S. aureus recognition and clearance of infection [10, 18], the results of our study have important clinical implications. Here, we demonstrate that monotherapy with vancomycin or daptomycin does not elicit a robust IL-1β response in patients. However, β-lactam therapy that includes oxacillin, cefazolin, or ceftaroline, either alone or in combination with vancomycin or daptomycin, enhanced IL-1β at days 3 and 7 of therapy. We suspect that the muted IL-1β response with non–β-lactam therapy may be a predisposing factor for the longer bacteremia that has been reported in MRSA compared to MSSA [19, 20]. Our pilot experiment results suggest the potential for short-term blockade of IL-1β signaling of reduced MRSA killing in human whole blood ex vivo and support further analysis of a direct role of sustained differences in IL-1β levels in supporting clearance of MRSA bacteremia. Future studies should evaluate how cytokine signaling with treatment correlates with bacterial clearance when considering other factors for persistent bacteremia, including infection source, source control, S. aureus lineage, and susceptibility.

In several independent studies of MRSA bacteremia, β-lactam therapy when combined with vancomycin or daptomycin reduces the duration of bacteremia [21–24]. Our current results indicate a beneficial role of β-lactam administration in supporting increased IL-1β responses in SaB, regardless of the organism’s β-lactam susceptibility. Based on prior experimental evidence, we hypothesize that β-lactams may induce IL-1β expression through multiple mechanisms. First, increased shedding of small amounts of S. aureus pathogen-associated molecular patterns such as peptidoglycan, lipoteichoic acid, and superantigens may improve macrophage recognition and release of IL-1β. Second, β-lactams increase expression of the proinflammatory S. aureus α-toxin [25], which induces host IL-1β expression via the NLRP3 inflammasome [26, 27] and has been inversely correlated with virulence in endovascular infection [28]. Third, a modified peptidoglycan with reduced cross-linking is produced by MRSA upon β-lactam treatment and is sensed differently by macrophages to elicit a more robust IL-1β response [29]. Finally, β-lactam–mediated reduction of peptidoglycan O-acetylation by o-acetyl transferase [30] renders S. aureus more vulnerable to macrophage killing and induces IL-1β release [31].

The functional significance of IL-1β induction is supported by studies in which genetic or pharmacological blockade of IL-1R signaling in mice led to increased bacterial burden during S. aureus infection including septic arthritis and pneumonia [32, 33]. Here, we show in short-term ex vivo whole blood killing assays, a potential for attenuated MRSA killing by addition of IL-1 receptor blocker anakinra. Although the causality of this effect is not conclusive, these results suggest that the IL-1β–driven S. aureus killing may be recapitulated in part by the subset of the innate immune cells present in whole blood. This is a topic that should be of interest for subsequent mechanic analyses.

Poor outcomes of S. aureus bacteremia are associated with immune imbalance at clinical presentation. Cell wall peptidoglycan is a known stimulator of IL-10 production in animals, and we have previously linked bacterial burden in the bloodstream with elevated IL-10 production in patients. The bactericidal nature of β-lactams against MSSA is well described via potent inhibition of cell wall transpeptidation/transglycosylation triggering autolytic enzyme release and ultimately cell lysis. For MRSA, β-lactams strongly synergize with vancomycin or daptomycin through enhanced potency or inhibition of penicillin-binding proteins as a dual mechanism of action [22, 34, 35]. In addition, we have shown considerable synergy between β-lactams and various arms of the innate host response in providing potent staphylocidal activity, a property not shared by daptomycin, vancomycin, or linezolid [36]. In this study, the greater IL-10 reduction with β-lactam therapy compared to vancomycin or daptomycin alone may reflect more rapid reduction in bacterial inoculum by β-lactams. However, the effects of β-lactams on IL-10 and, therefore, on mortality appear to be less robust than the effect on IL-1β, a cytokine linked to bacteremia duration. This is consistent with recently published clinical data wherein addition of flucloxacillin to vancomycin for the treatment of MRSA bacteremia had a notable impact on shortening bacteremia duration but did not reduce mortality [6]. However, a more recent study that did demonstrate a mortality reduction with daptomycin plus ceftaroline when used up front in MRSA bacteremia suggests that the use of combination therapy where both drugs exert simultaneous antibacterial activity and provide enhanced immune-mediated clearance may be most beneficial for the most difficult infections.

These findings further point to the clinical relevance of the increasingly appreciated properties of antibiotics beyond what is predicted by their activities in classic bacteriological media, including minimum inhibitory concentration, and bactericidal activity. Given the fact that these important antimicrobial attributes are totally missed in bacteriological media, it is not surprising that the bactericidal vs bacteriostatic characteristics defined in such media are of questionable clinical relevance [37].

This study is limited in that it was retrospective and the cytokine responses examined were limited to IL-10 and IL-1β. In addition, most of the β-lactam therapy in the MRSA arm was for patients treated with ceftaroline in combination with daptomycin, so this may not be generalizable to other β-lactam combinations. A prospective study to examine a larger cadre of cytokines, other innate host immune responses, and acquired immunity would add further insights, particularly if study designs integrate medical decision making with the results of the host response assays, including stratifying patients by IL-10 or other host biomarkers in order to escalate or deescalate novel therapies. Such studies would help address the continuing challenges experienced with clinical trials of antibiotics for SaB [38] and are essential before host response factors are incorporated into mainstream clinical management of SaB.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that patients with SaB who receive β-lactam antibiotic therapy generate a more favorable host immune response as it relates to increased IL-1β and decreased IL-10 production over the first 7 days. These factors may strongly influence the favorable clinical outcomes in β-lactam–treated patients. Benefits of β-lactam combination therapy for MRSA bacteremia remain an area of investigation, with attention shifting to identifying the patient subset for which such therapy is beneficial.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Sue McCrone for her assistance in collecting the samples used in this study.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01AI132627 to W. E. R. and 1U54HD090259 and 1U01AI124316 to V. N. and G. S.).

Potential conflicts of interest. G. S. has received speaking honoraria from Allergan, Theravance, and Melinta; consulting fees from Allergan and Paratek Pharmaceuticals; and is on the Cidara Therapeutics Scientific Advisory Board. W. E. R. has received grant funding from Merck and speaking honoraria from Melinta. V. N. reports grants from Roche and personal fees from Cidara outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Vogel M, Schmitz RP, Hagel S, et al. Infectious disease consultation for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia— a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2016; 72:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber MJ, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Inagaki K, Lucar J, Blackshear C, Hobbs CV. Methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia— nationwide estimates of 30-day readmission, in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in the US. Clin Infect Dis in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:e18–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geriak M, Haddad F, Rizvi K, et al. Clinical data on daptomycin plus ceftaroline versus standard of care monotherapy in the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63:e02483–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davis JS, Sud A, O’Sullivan MV, et al. Combination of vancomycin and beta-lactam therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a pilot multicenter randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCreary EM, Geriak M, Zasowski EJ, et al. Multi-centre cohort study of daptomycin plus ceftaroline combination compared to matched standard-of-care treatment in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. In: 28th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. Madrid, Spain, 2018;. abstract P2038.

- 8. Rose WE, Eickhoff JC, Shukla SK, et al. Elevated serum interleukin-10 at time of hospital admission is predictive of mortality in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1604–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Howden BP, Johnson PD, Ward PB, Stinear TP, Davies JK. Isolates with low-level vancomycin resistance associated with persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006; 50:3039–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Howden BP, Smith DJ, Mansell A, et al. Different bacterial gene expression patterns and attenuated host immune responses are associated with the evolution of low-level vancomycin resistance during persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. BMC Microbiol 2008; 8:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cameron DR, Lin YH, Trouillet-Assant S, et al. Vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus isolates are attenuated for virulence when compared with susceptible progenitors. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017; 23:767–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rose WE, Shukla SK, Berti AD, et al. Increased endovascular Staphylococcus aureus inoculum is the link between elevated serum interleukin 10 concentrations and mortality in patients with bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:1406–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guimaraes AO, Cao Y, Hong K, et al. A prognostic model of persistent bacteremia and mortality in complicated S. aureus bloodstream infection. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 68:1502-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fowler VG Jr, Olsen MK, Corey GR, et al. Clinical identifiers of complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:2066–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ogungbenro K, Hulme S, Rothwell N, Hopkins S, Tyrrell P, Galea J. Study design and population pharmacokinetic analysis of a phase II dose-ranging study of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2016; 43:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mantovani A, Dinarello CA, Molgora M, Garlanda C. Interleukin-1 and related cytokines in the regulation of inflammation and immunity. Immunity 2019; 50:778–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pires S, Parker D. IL-1β activation in response to Staphylococcus aureus lung infection requires inflammasome-dependent and independent mechanisms. Eur J Immunol 2018; 48:1707–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levine DP, Fromm BS, Reddy BR. Slow response to vancomycin or vancomycin plus rifampin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115:674–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fowler VG Jr, Boucher HW, Corey GR, et al. ; S. Aureus Endocarditis and Bacteremia Study Group Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:653–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bartash R, Nori P. Beta-lactam combination therapy for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus species bacteremia: a summary and appraisal of the evidence. Int J Infect Dis 2017; 63:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dhand A, Bayer AS, Pogliano J, et al. Use of antistaphylococcal beta-lactams to increase daptomycin activity in eradicating persistent bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: role of enhanced daptomycin binding. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:158–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sakoulas G, Moise PA, Casapao AM, et al. Antimicrobial salvage therapy for persistent staphylococcal bacteremia using daptomycin plus ceftaroline. Clin Ther 2014; 36:1317–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gritsenko D, Fedorenko M, Ruhe JJ, Altshuler J. Combination therapy with vancomycin and ceftaroline for refractory methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a case series. Clin Ther 2017; 39:212–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stevens DL, Ma Y, Salmi DB, McIndoo E, Wallace RJ, Bryant AE. Impact of antibiotics on expression of virulence-associated exotoxin genes in methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 2007; 195:202–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Craven RR, Gao X, Allen IC, et al. Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin activates the NLRP3-inflammasome in human and mouse monocytic cells. PLoS One 2009; 4:e7446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kebaier C, Chamberland RR, Allen IC, et al. Staphylococcus aureus α-hemolysin mediates virulence in a murine model of severe pneumonia through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:807–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bayer AS, Ramos MD, Menzies BE, Yeaman MR, Shen AJ, Cheung AL. Hyperproduction of alpha-toxin by Staphylococcus aureus results in paradoxically reduced virulence in experimental endocarditis: a host defense role for platelet microbicidal proteins. Infect Immun 1997; 65:4652–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Müller S, Wolf AJ, Iliev ID, Berg BL, Underhill DM, Liu GY. Poorly cross-linked peptidoglycan in MRSA due to mecA induction activates the inflammasome and exacerbates immunopathology. Cell Host Microbe 2015; 18:604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Qoronfleh MW, Wilkinson BJ. Effects of growth of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in the presence of beta-lactams on peptidoglycan structure and susceptibility to lytic enzymes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1986; 29:250–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shimada T, Park BG, Wolf AJ, et al. Staphylococcus aureus evades lysozyme-based peptidoglycan digestion that links phagocytosis, inflammasome activation, and IL-1beta secretion. Cell Host Microbe 2010; 7:38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ali A, Na M, Svensson MN, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist treatment aggravates staphylococcal septic arthritis and sepsis in mice. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0131645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Labrousse D, Perret M, Hayez D, et al. Kineret®/IL-1ra blocks the IL-1/IL-8 inflammatory cascade during recombinant Panton Valentine leukocidin-triggered pneumonia but not during S. aureus infection. PLoS One 2014; 9:e97546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berti AD, Sakoulas G, Nizet V, Tewhey R, Rose WE. β-Lactam antibiotics targeting PBP1 selectively enhance daptomycin activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57:5005–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Berti AD, Theisen E, Sauer JD, et al. Penicillin binding protein 1 is important in the compensatory response of Staphylococcus aureus to daptomycin-induced membrane damage and is a potential target for β-lactam-daptomycin synergy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:451–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sakoulas G, Okumura CY, Thienphrapa W, et al. Nafcillin enhances innate immune-mediated killing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014; 92:139–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wald-Dickler N, Holtom P, Spellberg B. Busting the myth of “static vs cidal”: a systemic literature review. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:1470–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Holland TL, Chambers HF, Boucher HW, et al. Considerations for clinical trials of Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:865–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.