Abstract

Human interleukin-12 (hIL-12) is a cytokine with anticancer activity, but its systemic application is limited by toxic inflammatory responses. We assessed the safety and biological effects of an hIL-12 gene, transcriptionally regulated by an oral activator. A multicenter phase 1 dose-escalation trial ( NCT02026271) treated 31 patients undergoing resection of recurrent high-grade glioma. Resection cavity walls were injected (day 0) with a fixed dose of the hIL-12 vector (Ad–RTS–hIL–12). The oral activator for hIL-12, veledimex (VDX), was administered preoperatively (assaying blood-brain barrier penetration) and postoperatively (measuring hIL-12 transcriptional regulation). Cohorts received 10 to 40 mg of VDX before and after Ad–RTS–hIL-12. Dose-related increases in VDX, IL-12, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) were observed in peripheral blood, with about 40% VDX tumor penetration. Frequency and severity of adverse events, including cytokine release syndrome, correlated with VDX dose, reversing promptly upon discontinuation. VDX (20 mg) had superior drug compliance and 12.7 months median overall survival (mOS) at mean follow-up of 13.1 months. Concurrent corticosteroids negatively affected survival: In patients cumulatively receiving >20 mg versus ≤20 mg of dexamethasone (days 0 to 14), mOS was 6.4 and 16.7 months, respectively, in all patients and 6.4 and 17.8 months, respectively, in the 20-mg VDX cohort. Re-resection in five of five patients with suspected recurrence after Ad–RTS–hIL-12 revealed mostly pseudoprogression with increased tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes producing IFN-γ and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1). These inflammatory infiltrates support an immunological antitumor effect of hIL-12. This phase 1 trial showed acceptable tolerability of regulated hIL-12 with encouraging preliminary results.

INTRODUCTION

Recurrent high-grade glioma (rHGG), also known as grade III or IV astrocytoma or glioblastoma (GBM), is an aggressive brain tumor with poor prognosis, with a median overall survival (mOS) of 6 to 9 months (1, 2). Treatment of rHGG has been limited partly because of incomplete understanding of the tumor microenvironment and immune evasion (3-6). rHGGs are spatially and temporally heterogenous, with diverse cell lineages bearing different mutational profiles that become expanded by chemotherapy and radiation (7-12). The tumor mass includes abnormal vasculature, an acellular structural framework, and an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment consisting of cells found during predominant T helper cell 0 (TH0) polarization, such as myeloid-derived and T suppressor cells, with a paucity of natural killer (NK) and cytotoxic T cells that are impaired by checkpoint signaling (13-16). Immune checkpoint inhibitors (iCPIs) may have a therapeutic role in the treatment of rHGG as early-stage clinical trials have recently reported (5, 15, 17, 18). However, the timing of drug dosing and the ability of iCPIs to sustain antitumor effects as monotherapy for most patients with recurrent GBM remain to be elucidated. Several products (bevacizumab, carmustine wafer, NovoTTF-100A, and lomustine), approved by the Food and Drug Administration, are not curative. Additional therapeutic options include nitrosoureas, temozolomide rechallenge, bevacizumab, administration of targeted biologics, and gross total resection (GTR) of contrast-enhancing area: These provide patients with rHGG with therapeutic options, but more effective therapies for rHGG are still needed (3, 19, 20).

Interleukin-12 (IL-12), a heterodimeric cytokine, enhances natural and adaptive immunity, potently stimulates production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and changes the tumor microenvironment from one that contains less differentiated TH0 cells to one that has more inflammatory TH1 cells (21-25). IL-12 has been shown to increase CD8+ T cell counts, improving survival in the GL-261 mouse glioma model (26, 27). There was interest in the use of recombinant IL-12 in humans with cancer, and clinical trials of systemic IL-12 were undertaken but had to be stopped because the cytokine, administered as a recombinant soluble protein, was poorly tolerated (28-32). With the objective of minimizing systemic toxicity, a ligand-inducible expression switch [RheoSwitch Therapeutic System (RTS)] was developed to locally control production of IL-12 in the tumor microenvironment. In this system, transcription of the IL-12 transgene occurs only in the presence of the activator ligand, veledimex (VDX) (26, 33). In mice, VDX regulates the RTS gene switch in an engineered replication-incompetent adenoviral Ad-RTS-mIL-12 gene therapy vector, resulting in VDX dose–dependent production of mouse IL-12 (mIL-12) in a model of GBM (26, 33). VDX crossed the blood-brain barrier (BBB) in the GL-261 orthotopic model of mouse glioma, with about 50% of the VDX plasma concentration present in the tumor.

Here, we report the results of an open-label, phase 1 dose-escalation study to determine safety and tolerability of variable VDX doses with a fixed intratumoral Ad–RTS–hIL-12 dose in patients undergoing rHGG resection. We show that VDX regulates production of IL-12 gene therapy in rHGG, converting an immunologically “cold” tumor microenvironment to inflamed “hot” due to increased influx of IFN-γ-producing T cells. We present preliminary evidence of encouraging mOS compared to historical controls, which is further improved when use of corticosteroids is minimized.

RESULTS

Accrued patients’ characteristics represent a heavily pretreated population

Demographics

Thirty-one patients (mean, 49 years; range, 26 to 74 years) were treated with Ad–RTS–hIL-12 + VDX (Table 1), including 20 (64.5%) with isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)–wild type GBM, 5 (16.1%) with IDH-mutant GBM, 3 (9.7%) with GBM not otherwise specified, 2 (6.5%) with IDH-mutant astrocytoma, and 1 (3.2%) with IDH–wild type astrocytoma. Twelve (38.7%) had O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation, which, in tumor cells, correlates with improved survival outcome in newly diagnosed GBM and improved response to temozolomide chemotherapy (34, 35). Eight (25.8%) were unmethylated, and 11 (35.5%) had unknown methylation statuses (statuses are unavailable from historical pathology reports).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics. vp, vector particles; NOS, not otherwise specified; KPS, Karnofsky performance score; LFTs, liver function tests; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; MGMT, methylguanine methyltransferase.

| Ad–RTS–hIL-12 (2 × 1011 vp) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-mg VDX n = 6 |

20-mg VDX n = 15 |

30-mg VDX n = 4 |

40-mg VDX n = 6 |

|

| Age (years): mean (min–max) | 49 (29–61) | 46 (26–68) | 60 (43–74) | 48 (36–58) |

| Gender (male:female) | 3: 3 | 10: 5 | 2: 2 | 4: 2 |

| Recurrence | ||||

| First | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Second | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Third or more | 0 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Prior lines of treatment (mean) | 2.0 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Prior bevacizumab | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| No | 5 | 11 | 0 | 5 |

| Disease at study entry | ||||

| IDH–wild type GBM | 4 | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| IDH-mutant GBM | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| GBM, NOS | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| IDH–wild type astrocytoma | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IDH-mutant astrocytoma | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| MGMT status | ||||

| Methylated | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Unmethylated | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Unknown | 3 | 8 | 2 | 1 |

| KPS at screening | ||||

| ≥90 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 4 |

| ≥70 and <90 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| Steroid use within 4 weeks before first dose | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

| No | 3 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total steroid use (mg) | ||||

| Days 0 to 14 | 82 (0–102) | 48 (0–140) | 106 (0–136) | 49.5 (10–102) |

| Median (min–max) | ||||

| Veledimex dosing | 79 | 84 | 63 | 58 |

| Compliance (%) | ||||

| Dose-limiting toxicities contributing to assessment of maximum tolerated dose | — | Aseptic meningitis | CRS, elevated LFTs | |

Prior therapies

Patients were previously treated with a mean of 2.3 (range, 1 to 5) lines of therapy. Ten (32%) patients had failed to respond to bevacizumab. Eighteen patients (58%) received corticosteroids within 4 weeks of Ad–RTS–hIL-12 + VDX.

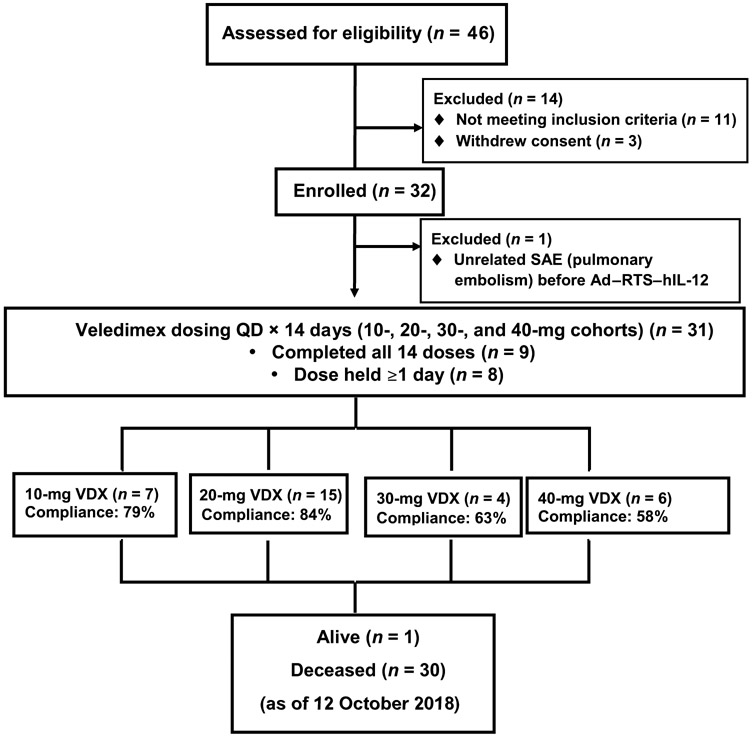

Treatment

Eleven patients (35%) underwent GTR based on the first postoperative scan (baseline). VDX (once per day) was started on postoperative day 1 for 14 days. The patient flow (CONSORT) diagram is shown in Fig. 1, with patient accrual at three institutions shown as the number of patients by VDX dosing level. Although no assessment of vector particles in tumor could be performed, the assays of human IL-12 (hIL-12) production shown in Fig. 2 provide evidence that enough vector particles transduced cells in the cavity to express the transgene.

Fig. 1. Study CONSORT diagram.

Patient accrual at four institutions shown as the number of patients treated at doses of 10, 20, 30, and 40 mg of VDX. The percentage of compliance represents the number of days that the VDX was orally administered versus the total number of days that each patient was expected to take the drug over 14 days. SAE, serious adverse event; QD, once a day.

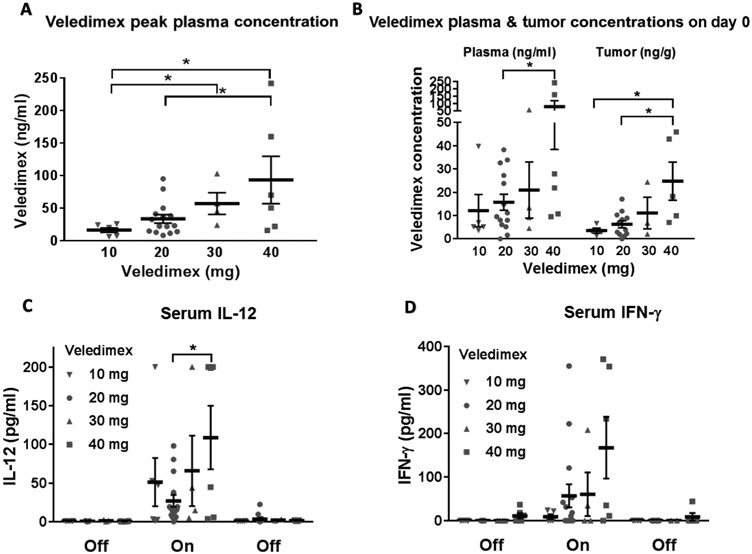

Fig. 2. VDX, IL-12, and IFN-γ concentrations upon VDX treatment.

(A) Peak plasma concentrations of VDX at each drug dosage. Each symbol represents plasma from a single patient. (B) VDX in plasma and intratumorally at the time of surgical resection. VDX was administered to each patient about 3 hours before the start of the craniotomy. Serum and tumor obtained at the time of resection were assayed for VDX concentrations. (C) IL-12 in peripheral blood before, during, and after VDX dosing. (D) IFN-γ in peripheral blood before, during, and after VDX dosing. *P < 0.05.

Safety

The primary analysis was to determine the tolerability of escalating VDX doses with administration of a single fixed dose of 2 × 1011 vector particles (vp) of replication-incompetent Ad–RTS–hIL-12 (Fig. 1). To determine a maximum tolerated VDX dose, a starting dose of 20 mg was administered to the first cohort. VDX was next escalated to 40 mg and then deescalated to 30 mg. These two doses were relatively poorly tolerated because of adverse events (AEs), resulting in dose holds and the inability to complete VDX dosing. On the basis of this result, although the protocol-defined maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was not reached because dosing in the 30-mg cohort was held before the development of dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs), 20 mg of VDX was declared the optimal dose for further development in an expansion cohort of eight additional patients. In addition, a cohort using 10 mg of VDX was assessed to determine a minimally effective dose.

Dose-dependent VDX peak-plasma concentrations correlated significantly (P < 0.05) with the dose, with significant differences between 10 and 30 mg of VDX (P < 0.02), 10 and 40 mg of VDX (P < 0.03), and 20 and 40 mg of VDX (P < 0.04) (Fig. 2A). AEs were reported at all VDX dose levels, with higher incidence of drug discontinuation at the higher doses (Table 2). All AEs were reversible after VDX interruption. Central nervous system (CNS) AEs were generally ≤grade 2 and confounded by underlying disease and surgery. Related ≥grade 3 CNS AEs reported included three events of headache and single events of brain edema, confusional state, and aseptic meningitis. The most common related ≥grade 3 AEs were lymphopenia/leukopenia, elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/aspartate aminotransferase (AST), neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and hyponatremia. Among the most common AEs, including individual AE components of cytokine release syndrome (CRS), the mean time to reversal (return to baseline or grade 1) upon VDX discontinuation was 4.5, 6.8, 8.8, and 9.1 days for lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and elevated ALT/AST, respectively. Although normalization of elevated body temperature was the first clinical sign of recovery, timing was confounded by concurrent use of antipyretics (including acetaminophen) and/or corticosteroids and the frequency of temperature recording. Transient flu-like symptoms and signs consistent with CRS occurred with varying severity but without observed grade ≥ 4 CRS. Frequency of grade 3 CRS was 0, 12.5, 25, and 50% in the 10-, 20-, 30-, and 40-mg dose groups, respectively, and was reversed upon holding or terminating VDX. In patients with grade 3 CRS, significant increases in serum IFN-γ over baseline (9 ± 6 pg/ml versus 239 ± 62 pg/ml, P < 0.01) and IL-12 (0.6 ± 0.2 pg/ml versus 105 ± 33 pg/ml, P < 0.02) were observed. In patients with milder or no CRS, significant increases in serum IFN-γ over baseline (0 ± 0 pg/ml versus 13 ± 6 pg/ml, P < 0.05) and IL-12 (0.6 ± 0.2 pg/ml versus 17 ± 5 pg/ml, p < 0.02) were also observed but to a lesser extent. A comparison of the peak cytokine concentrations in no or milder CRS versus grade 3 CRS showed significant increases in both serum IFN-γ (13 ± 6 pg/ml versus 239 ± 62 pg/ml, P < 0.02) and IL-12 (17 ± 5 pg/ml versus 105 ± 33 pg/ml, P < 0.04) in patients with CRS. In one patient with a grade 3 CRS, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sampling revealed high concentrations of IL-12 and IFN-γ by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and pleocytosis with elevated NK cell (75% of CSF lymphocytes) and CD3+ T cell counts (20%) detected by flow cytometry.

Table 2.

AEs and VDX compliance.

| Ad–RTS–hIL-12 (2 × 1011 vp) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-mg VDX n = 6 |

20-mg VDX n = 15 |

30 mg of VDX n = 4 |

40 mg of VDX n = 6 |

|

| Event term | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| ≥Grade 3–related AEs | ||||

| Lymphopenia/lymphocyte count decrease | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (20.3) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) |

| Increased LFTs | 2 (33.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 2 (33.3) |

| Leukopenia/leukocyte count decrease | 1 (16.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Neutropenia/neutrophil count decrease | 1 (16.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia/platelet count decrease | 0 | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 0 | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| Cytokine release syndrome | ||||

| CRS grade 2a | 2 (33.3) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) |

| CRS grade 3a | 0 | 2 (13.3) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| ≥Grade 3 neurologic AEs | ||||

| Headache | 0 | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Brain edema | 0 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Confusional state | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| Aseptic meningitis | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 |

| VDX dosing | ||||

| Compliance (%) | 79 | 84 | 63 | 58 |

CRS as determined by Ziopharm CRS Working Definition, which reflects that CRS may clinically present as a multisystem disorder and therefore considers the following criteria: occurrence of influenza-like symptoms; grading of certain hepatic (transaminitis), hematological (lymphopenia), neurological, renal, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and/or cardiac toxicities; any oxygen requirement or need for vasopressor(s); and/or increased peripheral cytokine concentrations.

VDX crosses the BBB and regulates transcription of recombinant IL-12, eliciting and sustaining an intratumoral immune response

Dose-dependent increases in plasma and tumor VDX concentrations were observed, with about 40% of VDX plasma concentrations detected in resected rHGG tissue after a single VDX dose (Fig. 2B), consistent with BBB penetration. Sampling before (“off,” baseline value before VDX dosing), during (“on,” peak value for each patient during the 14 days of VDX administration with samples collected on days 1, 3, 7, and 14), and after VDX (“off,” 2 weeks after cessation of VDX administration) revealed an increase in IL-12 and IFN-γ serum concentrations proportional to VDX dose (Fig. 2, C and D), indicating that VDX stimulated IL-12 transcription and subsequent generation of its downstream effector, IFN-γ. IL-12 and IFN-γ serum concentrations returned to baseline after VDX discontinuation, consistent with transient regulation of hIL-12 transcription. Three (±2) hours after VDX administration, the peak IL-12 serum concentration across the four cohorts was 25 to 109 pg/ml, and the peak IFN-γ serum concentration was 15 to 168 pg/ml. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is routinely used to monitor the progression of HGG. In addition, the contrast imaging agent, gadolinium (Gd), is administered intravenously to patients. The agent remains intravascular in the brain because it does not cross the BBB. However, if the BBB is disrupted by tumor, inflammation, or necrosis, then Gd leaks out (36). This uptake of contrast in brain tissue is the accepted surrogate to measure HGG/rHGG and its response to therapy. Because this uptake of Gd can also occur during inflammation or necrosis from previous treatments (such as radiation), this measurement by Gd uptake may also be unrelated to tumor growth. This has been called pseudoprogression to distinguish it from true tumor progression (37-41). Five patients with progressive MRI enhancement underwent another resection 1, 1.5, 4.3, 5.3, and 5.8 months after Ad–RTS–hIL-12 injection. In all five patients, there was evidence of increased inflammatory infiltrates, and immunohistochemistry revealed visible increases in CD8+ T cell infiltrates in the tumors (fig. S1). The patient (PT10) who recurred at 1 month could tolerate only six doses of VDX (40 mg), and post-injection tissue showed mostly recurrent tumor, but the other four patients’ post-injection excised tissues were more consistent with pseudoprogression. Neuropathologic analysis showed a decrease in vascular proliferation in the patient (PT17) with suspected recurrence at 1.5 months (table S1).

A representative patient (PT37) MRI series is shown in Fig. 3A, including areas with gradual increases in enhancement in both the occipital and parietal needle tracks. The size of the parietal lesion appeared to increase and then subsequently decrease, consistent with pseudoprogression (Fig. 3A). Re-resected tissue revealed new mixtures of immune cells, interspersed with varying amounts of tumor cells, and reactive changes. Sufficient tissue for multiplexed immunofluorescence of GBMs before and after gene therapy was available for three of five patients (PT37, PT38, and PT39; Fig. 3B). This showed a 17-fold increase in the mean number of CD3+ T cells [tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)] after treatment, as well as increases in CD3+CD8+ T cells, PD-1+ immune cells, and PD-L1–expressing cells (Fig. 3C). In contrast, there was no difference in CD3+CD4+FoxP3+ T regulatory cells or CD56+ NK cells by immunohistochemistry before and after IL-12 therapy (Fig. 3C). Intratumoral (localized) IFN-γ was measured with means ± SEM of 4 ± 3 pg/g and 226 ± 138 pg/g before and after gene therapy, respectively (Fig. 3D). Concurrent serum IFN-γ was below the limit of quantification in these three patients whose tumors were re-resected and analyzed after gene therapy. These results suggested that IL-12 gene therapy elicited sustained tumor infiltration of T cells producing IFN-γ, thereby promoting a proinflammatory tumor environment.

Fig. 3. Radiologic and immunologic analyses of tumors after treatment.

(A) Three patients with suspected progression after treatment underwent re-resection of contrast-enhancing suspected tumor. The MRI images shown are from one patient who had a right occipital recurrent GBM resected. The MRI scans from 1 day after surgery (baseline) and from weeks 4, 8, and 24 are shown. The injections were given in an area of the occipital lobe and one area more superior toward the parietal lobe. Red and yellow arrows show areas with changes in enhancement in the occipital and parietal needle tracks. (B) Left panels: GBM from the patient shown in (A) at the time of resection before injection of Ad–RTS–hIL-12 [shown in the top panel at 20× magnification (scale bar, 100 μm) and in the bottom panel at 100× magnification (scale bar, 50 μm)]. Right panels: GBM from the same patient 175 days after treatment (at the time of suspected pseudoprogression). Resected material from the occipital lesion was analyzed by immunofluorescence histochemistry for expression of CD3+ (yellow), CD8+ (red), CD3+CD8+ (orange), PD-1+ (green), PD-L1+ (cyan), and GFAP (white) [shown in the top panel at 20× magnification (scale bar, 100 μm) and in the bottom panel at 100× magnification (scale bar, 50 μm)]. (C and D) Quantitative analyses of baseline and posttreatment expression of immunologic markers in tumors for the three patients undergoing re-resection after injection. (C) Counts of CD3+-, CD3+CD8+-, PD-1+-, CD3+CD4+FoxP3+-, CD56+-, and PD-L1+–expressing cells per square millimeter of tumor. (D) IFN-γ in the three GBMs before and after treatment.

Preliminary efficacy analyses suggest encouraging OS

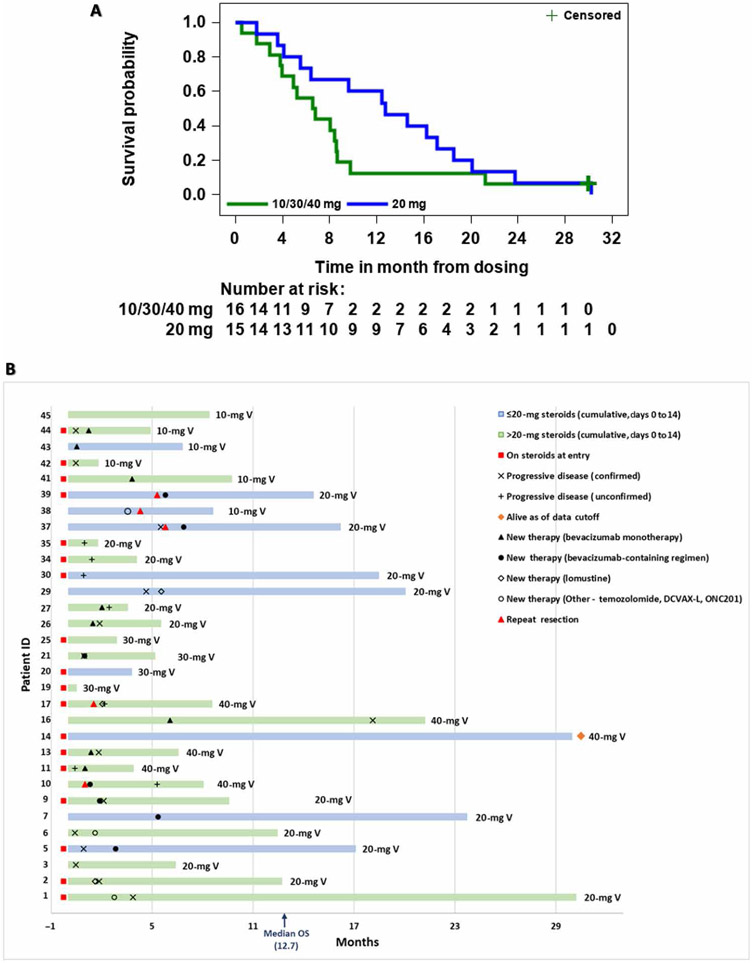

The 20-mg VDX cohort exhibited a mOS of 12.7 months with 13.1 months of mean follow-up (Fig. 4A). Survival in the 20-mg cohort at 12, 18, and 24 months was 60, 26.7, and 13.3%, respectively. Survival at 12 months in the 10-, 20-, 30-, and 40-mg cohorts was 0, 60, 0, and 30%, respectively. One patient receiving the 40-mg VDX dose was alive at the time of data cutoff (~30 months) (Fig. 4B). Twenty-one patients elected to pursue additional therapies with a median start time of 2.6 months (minimum, 1 month; maximum, 7.4 months).

Fig. 4. Analyses of treatment efficacy.

(A) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS) for the 20-mg (blue line) versus combined 10-, 30-, and 40-mg cohorts (green line). The + censored label refers to the single patient alive at time of data cutoff. (B) Survival swimmer plot. The x axis lists survival time in months, with each patient number on the y axis. Blue and green colors represent patients who received 20 mg or less or more than 20 mg of cumulative dexamethasone, respectively, during days 0 to 14 of VDX treatment. The 10-, 20-, 30-, and 40-mg V designations at the end of each bar represent the dose of VDX that each patient received. Patients on steroids at entry, timing of progressive disease, and other therapy events are listed. The median OS was 12.7 months.

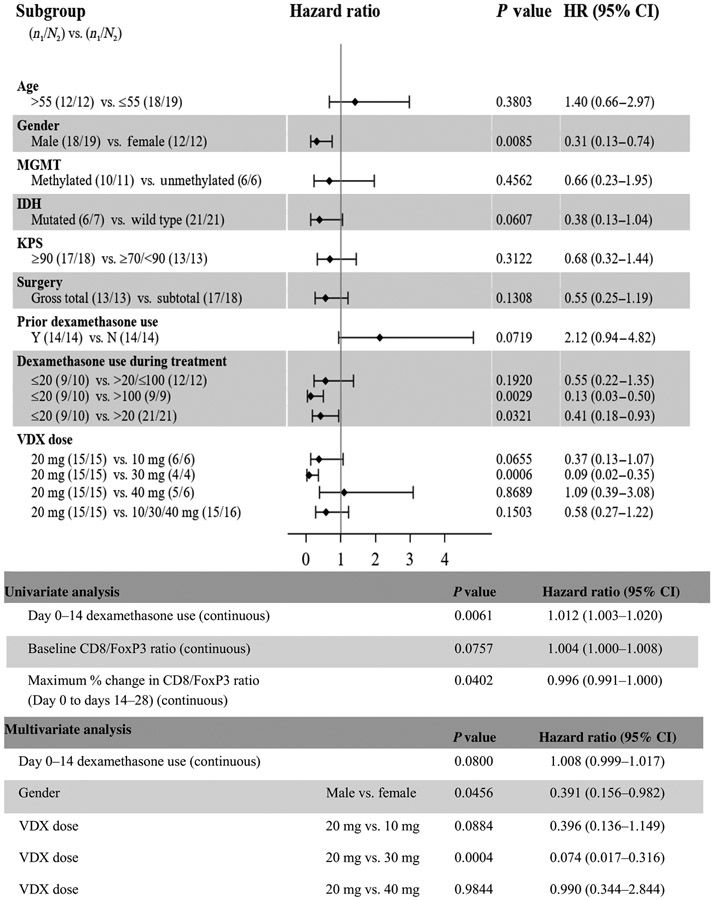

Potential prognostic variables for overall survival (OS) were examined using Cox regression (Fig. 5). P values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the estimate of the hazard ratio identified that cumulative dexamethasone exposure to less versus more than 20 mg (P = 0.0321) and male gender (P = 0.0085) had a significant, positive association with OS. IDH (mutated) status at initial diagnosis (P = 0.0607) and prior dexamethasone use (P = 0.0719) had no significant association with OS. Age, functional status, MGMT methylation at initial diagnosis, and extent of tumor resection failed to correlate with OS. Analysis using a multivariate Cox regression model demonstrated that VDX dose (20 mg versus 30 mg, P = 0.0004) and gender (P = 0.0456) remained statistically significant for a positive association with OS, whereas dexamethasone did not show a significant correlation with OS (P = 0.08).

Fig. 5. Forest plots of prognostic factors of subgroups examined for OS.

HR, hazard ratio.

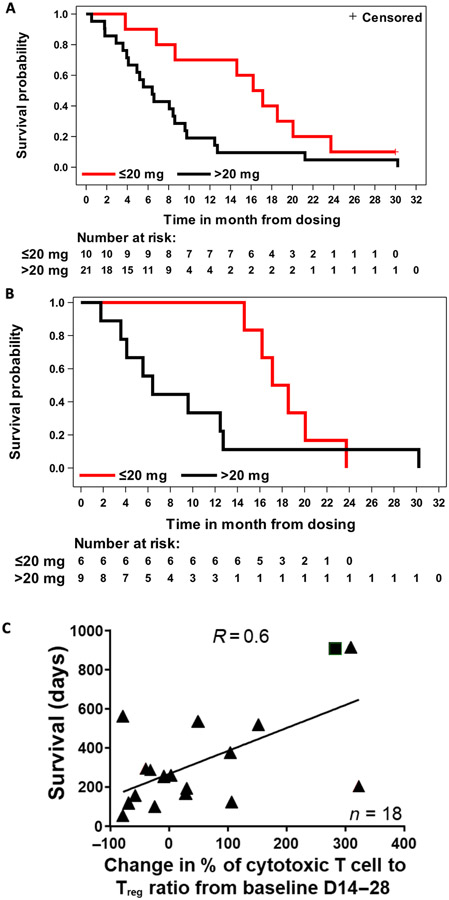

In the overall patient population, concurrent corticosteroids negatively affected survival: In patients cumulatively receiving >20 mg versus ≤20 mg of dexamethasone (days 0 to 14), mOS was 6.4 months (mean follow-up, 8.0 months) versus 16.7 months (mean follow-up, 16.0 months), respectively (Fig. 6A). In the 20-mg cohort, in patients cumulatively receiving >20 mg versus ≤20 mg of dexamethasone (days 0 to 14), mOS was 6.4 months (mean follow-up, 9.6 months) versus 17.8 months (mean follow-up, 18.4 months), respectively (Fig. 6B). To examine whether survival could be predicted on the basis of the impact of IL-12 on the immune system, we analyzed the changes in CD8+ (cytotoxic) and FoxP3+ (regulatory) T cell counts in the peripheral blood of patients on days 14 to 28 after treatment. When compared to baseline counts, a positive correlation (R = 0.6, P = 0.0071) between patient OS and percentage of change in the CD8+/FoxP3+ ratio was observed (Fig. 6C), suggesting that a systemic measurement of immune activation may correlate with therapeutic success of local administration of IL-12.

Fig. 6. Additional efficacy analyses.

(A and B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves based on cumulative dexamethasone dosage (red line, ≤20 mg of dexamethasone; black line, >20 mg of dexamethasone) for patients treated with (A) 10, 20, 30, or 40 mg of VDX (days 0 to 14) or (B) 20 mg of VDX (days 0 to 14). (C) Correlation of survival with peripheral blood CD8+ (cytotoxic T cell)/FOXP3+ [regulatory T cell (Treg)] ratio at 14 to 28 days after viral injection. Triangles represent deceased patients, and square represents an alive patient (P = 0.0071, R = 0.6).

DISCUSSION

Finding effective immunotherapy approaches against rHGG remains challenging because of the highly immunosuppressive nature of the tumor microenvironment (42). IL-12 potently activates several immune effector functions against cancer cells (32). However, trials with recombinant systemic IL-12 administration failed because of intolerable toxicity in humans, mainly because of uncontrolled CRS (29). We hypothesized that a drug-inducible gene therapy approach would minimize toxicity and would be tolerated in humans while preserving the antitumor effects of hIL-12. Here, we have shown in humans that VDX-inducible gene therapy allows for regulatable expression of hIL-12 in rHGG, resulting in IFN-γ generation and increased TILs with tolerable and reversible side effects.

This gene therapy approach could be applied in a variety of cancers to regulate local production of proteins that show low tolerability when delivered systemically. Previously, a dose of 2 × 1011 vp of an adenoviral vector constitutively delivering IFN-β was shown to cause intolerable neurotoxicity (43). In contrast, the main advantage of our study relies on the ability to control and, as necessary, halt cytokine expression using the ligand-inducible gene switch. There have been other gene therapy trials that have used adenoviral vectors to deliver IL-12 for oncologic disease (44-46). These trials did not use ligand-activated transcriptional regulation and were not performed in GBM, where toxicity from continuously uncontrolled production of IL-12 could be more deleterious. The use of a gene therapy vector to deliver IL-12 uses a different mechanism of tumor killing from the ones described in recent clinical trials with oncolytic viruses that have direct cytolytic effects from active viral replication or other gene delivery approaches, such as adenoviral vectors expressing herpes simplex thymidine kinase conferring cytotoxicity to valacyclovir (47-51).

These phase 1 data established that VDX crosses the BBB. We found a positive correlation between VDX dose and serum IL-12, as well as IFN-γ concentrations. VDX modulated the timing, duration, and magnitude of IL-12 gene expression. Serum IL-12 and IFN-γ reflect local (intratumoral) cytokine production and seepage of IL-12 through the vasculature. Transcriptional control of hIL-12 was tightly regulated by RTS as evidenced by the negligible detection of this cytokine in the blood upon discontinuation of VDX, which is consistent with absence of clinically relevant leakage. The 10-mg VDX cohort showed a slightly higher serum IL-12 concentration than anticipated, but this finding may be explained by the small size of this cohort, which included one patient taking multiple CYP 3A4–interacting medications that likely resulted in increased VDX concentrations that led to IL-12 concentrations higher than 200 pg/ml (33).

Neurologic AEs were generally mild to moderate (grade ≤ 2) and potentially confounded by underlying disease and surgery. The frequency and severity of all AEs correlated with VDX dose and reversed promptly upon holding or discontinuing VDX. Compared to the higher VDX dose cohorts (30 and 40 mg), the 10- and 20-mg cohorts presented less severe CRS and much better tolerability, resulting in higher compliance with treatment. When more severe CRS was observed, it correlated with increased serum IFN-γ concentrations and, to a lesser extent, with serum IL-12. Blood collection timing was possibly suboptimal to unequivocally document Cmax. These data highlight that production of hIL-12 within the CNS is well tolerated and that systemic side effects can be mitigated using a gene transcriptional “switch.”

GBM has been characterized as an immunological “desert” with scant TILs (3, 42). This likely limits the therapeutic potential of iCPIs. When present, resident T cells are profiled as exhausted, highlighting the immunosuppression of HGG (4, 52). These data contrast with our finding of persistent infiltration of T cells in five of five patients, weeks to months after completion of VDX. This interpretation is also supported by the observation that increased numbers of CD3+ and CD8+ lymphocytes infiltrating the tumor microenvironment may be associated with better clinical outcome in GBM (53, 54). The observation of sustained and markedly increased IFN-γ concentrations in the tumor microenvironment after the peritumoral administration of Ad–RTS–hIL-12 and activation of IL-12 gene expression by VDX is aligned with cytotoxic effector T cell function rather than with T cell anergy or exhaustion. Furthermore, local IFN-γ (presumably generated by activated TILs) in the absence of detectable IFN-γ in peripheral blood is consistent with the absence of AEs after completion of VDX. As a result, intratumoral localization of hIL-12 may allow for a more durable antitumor effect without the substantial systemic toxicity that was historically associated with systemic administration of IL-12. These data contribute to our understanding of IL-12 as a “master regulator” of the immune system and highlight that even the transient production of this cytokine may function as a match to turn tumors from cold to hot. IL-12 has also been reported to have anti-angiogenic effects (55). In one patient (PT17) with suspected recurrence 1.5 months after injection, re-resected tumor showed visual evidence of reduced vascular proliferation when compared to pre-injection tissue. However, this was not evident in the other four patients. PT10, who underwent repeat craniotomy 31 days after injection, could only tolerate six doses of VDX and thus may not have had sufficient IL-12 for angiogenesis. The other three patients were re-resected several months after injection and already had a low number of blood vessels in tumors at baseline. Therefore, IL-12 anti-angiogenic effects may not have been easy to detect in these samples.

Of all doses tested, not only did 20 mg have a better safety profile, but also it improved survival, possibly because of superior treatment compliance with VDX. However, there was a higher proportion of IDH-mutant and IDH-unknown tumors in the 20-mg cohort in comparison to other cohorts. We attempted to compare the mOS of this subgroup to historical controls, but there are limitations to this type of analysis. The mOS of 12.7 months with a mean follow-up of 13.1 months appears better than the weighted median from historical controls (8.14 months) (19, 56-67). The survival rates at 6, 9, and 12 months compared favorably to previously reported results (19, 56-67). In contrast, cohorts of 30 and 40 mg revealed shorter mOS, presumably because these patients did not tolerate the VDX treatment. In addition, in the 30-mg cohort, the patients were slightly older (60 versus 46 years), had previously undergone more failed lines of therapy (3.0 versus 2.2), had a higher rate of previous bevacizumab exposure (4 of 4 versus 4 of 15), and received a higher cumulative dose of steroids during active VDX dosing (106 mg versus 48 mg). Patients who received a cumulative dose of ≤20 mg of dexamethasone during active VDX dosing had the longest survival (16.7-month mOS in all patients treated, improving to 17.8-month mOS in the 20-mg VDX cohort), possibly because they were less likely to experience steroid immunosuppression and impairment of immune activation. Alternatively, dexamethasone-based induction of CYP 3A4 could have increased the elimination of VDX, thus inhibiting transcriptional activation of IL-12. The apparent deleterious impact of dexamethasone when dosed with VDX highlights that patients with rHGG may benefit from limiting systemic exposure of corticosteroids to maximize the benefit of immunotherapy such as hIL-12.

MRI interpretation is particularly challenging in the rHGG population. Numerous studies have shown that the correlation between increased Gd enhancement and survival is at best limited (68, 69). The reliability of MRI in assessing tumor progression is particularly difficult in patients who have had previous surgery. Varying degrees of tumor reduction have been seen, as well as new and fluctuating lesions, consistent with previously reported imaging with viral vector–based immunotherapy (47, 50). Inflammatory and potentially delayed responses to immunotherapy further compound interpretation of response by MRI even with recent guidelines (68). Our findings with three patients who underwent posttreatment biopsy when suspected of clinical progression revealed a marked immune cell infiltrate and low tumor cell content, consistent with pseudoprogression rather than tumor progression. This highlights the difficulty and lack of predictability of MRI for true progressive disease during immunotherapy. With these cautionary statements in mind, measured progression-free survival per immunotherapy Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (iRANO) criterion was 0.9 months (95% CI, 0.4 to 2.0 m).

The impact of tumor resection on postrecurrence survival is difficult to assess, but one prospective, randomized study showed a survival of 23.4 weeks (5.4 months) in patients with more than 75% resection at reoperation (59). A more recent nonrandomized report estimated ranges from 6.5 months for patients with incomplete tumor resection to 11.4 months for patients with GTR and 9.8 months for patients who did not undergo surgery (70). An additional recent study revealed that resection of recurrent rGBM improved mOS from 4.7 to 9.6 months (71).

The observed survival in the 20-mg cohort is encouraging given the number of previous recurrences (11 of 15 patients with two or more), previous bevacizumab failures (4 of 15), concomitant steroid use, lack of exclusion for bulky or multifocal tumors, and GTR in only 35% of patients. The sustained production of IFN-γ, marked CD8+ T cell infiltration, and increased expression of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) after treatment support an immune basis for the mechanism of action of IL-12 and warrant studies including combination with iCPIs, which are currently in progress ( NCT03636477, clinicaltrials.gov). However, the observed survival benefit needs further confirmation given the small number of patients and the absence of a control arm. An alternative to the use of historical controls as a control arm would have been to use comparable cohorts of patients who were treated with standard of care at each participating institution. However, this analysis would also have been limited by the lack of agreement on what constitutes standard of care in the comparand rHGG patient population, by the number of pretreatments this comparand cohort would have gone through, and by the type of concurrent treatments that this comparand cohort was subjected to. This type of analysis may be easier to do in the newly diagnosed HGG setting, as done in (51). In addition, treatment modalities in phase 1 studies such as this aim to establish safety and tolerability, but because the treatment is delivered during neurosurgical resection, evaluation of side effects is rendered difficult by side effects caused by the surgery itself.

In summary, this phase 1 trial reports the use of a transcriptional switch to safely control dosing of hIL-12, highlighting that this can be accomplished across the BBB to remodel the tumor microenvironment with an influx of activated immune cells. The trial showed encouraging mOS (12.7 months) in patients with rHGG compared to historical controls, which further improved to 17.8 months when dexamethasone use was limited during active dosing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

ATI001-102 ( NCT02026271, clinicaltrials.gov) used a standard phase 1 open-label, unblinded, 3 + 3 dose escalation design to evaluate the safety and tolerability of Ad–RTS–hIL-12 (a single intratumoral injection, 2 × 1011 vector particles) with four oral VDX dose levels (10, 20, 30, and 40 mg) in patients with rHGG scheduled for tumor resection (either for a GTR, defined as greater than 90% removal of Gd-enhancing tumor by MRI within 48 hours or subtotal) on day 0. The arm of the trial being presented in the current study required that patients could undergo a surgical resection of tumor, but we have also accrued patients to a second arm in the clinical trial to assess the safety of stereotactic Ad–RTS–hIL-12 injection in tumors that could not be resected. The primary end point was assessment of safety of Ad–RTS–hIL-12 + VDX. Secondary end points included OS, VDX concentration, correlative measures of immune response, overall response rate, and progression-free survival. To obtain a preliminary assessment of efficacy, we used survival results from published literature (see below).

Patients

Institutional review boards approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from patients before enrollment. AEs were evaluated on the basis of National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for AEs, version 4.03. Patients were prospectively selected on the basis of age (18 to 75 years), diagnosis of supratentorial, histologically confirmed HGG (World Health Organization grade III or IV) and evidence of recurrence as determined by MRI according to the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria after receiving standard initial therapy (68, 69). Patients were required to have a Karnofsky performance status of ≥70, adequate bone marrow, liver, and kidney functions, and ability to undergo standard MRI with contrast. Patients and their tumors had to be deemed eligible for a craniotomy for tumor resection.

Patients were excluded if they had radiotherapy within 4 weeks, clinically significant concurrent medical conditions, or uncontrolled seizures. There were no limitations on the number of previous therapies, previous recurrences, or previous bevacizumab or dexamethasone use. Use of cytochrome P450 system (CYP 3A4)–interacting medications (excluding dexamethasone) was prohibited because CYP 3A4 metabolizes VDX (26, 33).

Ad–RTS–hIL-12 and VDX

Ad–RTS–hIL-12 is a replication-incompetent adenoviral serotype 5 vector encoding the hIL-12 p70 transgene under the control of the RTS gene switch (26, 72). VDX is an orally active small-molecule activator ligand(R)-N′-(3,5-dimethylbenzoyl)-N′-(2,2-dimethylhexan-3-yl)-2-ethyl-3-methoxybenzohydrazide. Data related to the pharmacokinetics of VDX in mice and monkeys have been published (26, 33).

Treatment

About 3 hours before resection, patients received one VDX dose. Peripheral blood was collected at the time of resection (on day 0). Immediately after resection, patients received intraoperative freehand injections of Ad–RTS–hIL-12 to two peritumoral sites for a total volume of 0.1 ml. Injection sites were selected by the neurosurgeon and had to be noncontiguous with the ventricle. The type and mode of injection have been described before (43, 49-51). Briefly, a 25-gauge needle attached to a tuberculin syringe was inserted into the white matter of the resected tumor cavity, and 50 μl was slowly injected over about 30 to 60 s. The needle was slowly retracted. Routine neurosurgical hemostasis was carried out.

Imaging and tumor evaluation

After the resection, baseline MRI was performed within 72 hours after Ad–RTS–hIL-12 administration. Imaging assessments were performed using the RANO/iRANO criteria (68, 69). Tumor response was evaluated radiographically at study sites and through a central reading laboratory using serial MRI scans. Radiographic tumor size was assessed using perpendicular bidimensional measurements per RANO/iRANO criterion (68, 69). Tumor response was assessed at 2 weeks (day 14), 4 weeks (day 28 ± 7 days), 8 weeks (day 56 ± 7 days), and every 8 weeks thereafter for all patients until the occurrence of confirmed tumor progression. There were no reports of ischemia or infarction at the sites of vector injection.

Measurement of VDX

Brain tumor and plasma samples were analyzed for VDX using a liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry method (33).

Cytokine analyses

Serum hIL-12 and IFN-γ were measured by ELISA using kits from R&D Systems Inc. [catalog nos. D1200 (IL-12) and DIF50 (IFN-γ)]. IL-12 and IFN-γ in CSF (intraoperative sampling) were measured by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay using a human “V-PLEX” custom kit obtained from Meso Scale Discovery (catalog no. K151A0H-01). All assays were run according to the manufacturers’ procedures. Samples were assayed in triplicate.

Tumor immunoprofiling

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples were prepared from surgical resection before treatment and biopsies after treatment at the time of suspected progression. A conventional hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained slide was reviewed (NeoGenomics Inc.) to confirm the presence of tumor and at least 500 cells before proceeding with immunofluorescence labeling. A virtual bright-field–type image of the tissue was created similar to a conventional histochemical H&E-stained tissue section, using fluorescence images (73). In this method, nuclear labeling from the 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) channel was assigned a purple pseudocolor to simulate hematoxylin staining, and nonnuclear structural characteristics derived from tissue autofluorescence in the Cy2 (fluorescein isothiocyanate) channel were assigned a pink pseudocolor to simulate eosin counterstaining. Fifteen to thirty regions of interest per slide were then manually selected for analysis by a trained pathologist from the actual serial section being multiplex immunolabeled using this “virtual” H&E stain. Multiplexed immunofluorescence was performed using MultiOmyx technology [MultiOmyx: Multi-Molecular Multiplexing Methodology, NeoGenomics Inc. (74)] to label up to 12 biomarkers on a single slide, including antibodies with specificities for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20, CD56, CD68, CD45RO, PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, FoxP3, and GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein). Each of the six cycles of labeling was performed using a pair of antibodies directly conjugated to either Cy3 or Cy5, followed by imaging using an IN Cell Analyzer 2200 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and then dye inactivation (75, 76). Nucleated cells (25,000 to 80,000) per sample were analyzed with proprietary software (MultiOmyx: Multi-Molecular Multiplexing Methodology, NeoGenomics Inc.), using the DAPI channel to align markers. Exploratory image analysis was performed using proprietary algorithms (MultiOmyx: Multi-Molecular Multiplexing Methodology, NeoGenomics Inc.) to quantify expression of markers, detect and classify cells by immunophenotype, and determine the density of cells per unit area by immunophenotype.

Historical controls

An initial literature search of randomized phase 2, 2/3, or 3 studies for patients with rHGG receiving approved treatments of lomustine, carmustine wafer, bevacizumab, temozolomide, and NovoTTF-100A identified 13 studies with a total of 2339 patients. This dataset was further refined to only include studies using North American and/or European standard of care: bevacizumab or lomustine as monotherapy (9 studies; 10 arms; 698 patients) and was used as the basis for our historical controls (55-66). We calculated a weighted mOS using the following formula

where W = weight and n = sample size.

Statistical analysis

Safety of Ad–RTS–hIL-12 + VDX was determined by AE severity and frequency to decide on DLT and MTD. VDX concentration ratios between brain tumor and plasma and peak cytokine (IL-12 and IFN-γ) concentrations are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis for VDX and cytokine concentration consisted of a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and when appropriate (when a comparison between specific treatment groups was needed), an unpaired t test was performed. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate mOS and 12-, 18-, and 24-month OS rates. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis were used to determine the effect of selected variables on OS.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Histo- and immunopathological features of tumors before and after Ad–RTS–hIL-12 + VDX treatment.

Table S1. Neuropathologic analysis of vascular proliferation in GBMs before and after Ad–RTS–hIL-12 injection + VDX.

Acknowledgments:

This paper is dedicated to the memory of the patients and their families who participated in this trial. We thank J. W. Ragheb at NeoGenomics Inc. for pathological review of tumor samples. We thank the study participants and their families for participation, as well as the research staff for hard work on the trial, and A. Gwosdow for editorial support.

Funding: The clinical trial and correlative studies were funded by Ziopharm Oncology Inc. and by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant numbers 2P01CA163205 and CA069246-20 to E.A.C.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Competing interests: J.Y.B., N.D., J.A.B., A.B.G., J.Z., L.J.N.C., and F.L. are employees and own equity interest in Ziopharm Oncology Inc. E.A.C. is currently an advisor to Advantagene Inc., Alcyone Lifesciences, INSIGHTEC Inc., Sigilon Therapeutics, and DNAtrix Inc. and has equity interest in DNAtrix. He has also advised Oncorus, Merck, Tocagen, Stemgen, NanoTx, Ziopharm Oncology, Cerebral Therapeutics, Genenta, Janssen, Karcinolysis, and JI Shanghai Biotech. He has received research support from the NIH, U.S. Department of Defense, American Brain Tumor Association, National Brain Tumor Society, Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy, Neurosurgery Research & Education Foundation, Advantagene, NewLink Genetics, and Amgen. He is also a named inventor on patents related to oncolytic HSV1. R.V.L. has received NIH funding via NCI Brain Tumor SPORE P50CA221747, has served on the advisory boards for Monteris and Ziopharm, and has received consulting fees from AbbVie, NewLink Genetics, and ReNeuron and travel support from Genentech-Roche to present at a meeting, honoraria for medical editing for MedLink Neurology, honoraria for review of content for medical accuracy for EBSCO Publishing, and honoraria for creating and presenting content for CME board review courses for American Physician Institute. He has received personal fees from AbbVie for internal presentations. D.A.R. reports research support from Acerta Pharmaceuticals, Agenus, Celldex Therapeutics, EMD Serono, Incyte, Midatech Pharma, Omniox, and Tragara Pharmaceuticals. He has also received personal fees from Agenus, Celldex Therapeutics, EMD Serono, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Genentech-Roche, Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Merck KGaA, Monteris, Novocure, Oncorus, OxiGENE, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Stemline Therapeutics, and Taiho Oncology Inc. L.J.N.C. reports royalties from City of Hope and MD Anderson Cancer Center; equity interest in Secure Transfusion Services, Ignite Power, Chalice Wealth Partners, CytoSen Therapeutics, Kiadis Pharma, Immatics Biotechnologies, and Targazyme Inc.; and intellectual property led by or licensed to Sangamo Therapeutics, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Ziopharm Oncology Inc., Intrexon Inc. (PCT/US2011/029682, 62/690,552, 62/834,685, and 62/854,771). K.L.L. reports equity in Travera LLC and research support from Deciphera Pharmaceuticals, Tragara Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Eli Lilly and Company, BMS, and X4 Pharmaceuticals. He also serves on the advisory board for Integragen and is a consultant to BMS and RareCyte Inc. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. Trial registration number: NCT02026271. Original clinical data are available via J. Buck (Jbuck@ziopharm.com), Ziopharm Oncology Inc., One First Avenue, Parris Building 34, Navy Yard Plaza, Charlestown, Boston, MA 02129, USA.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Kamiya-Matsuoka C, Gilbert MR, Treating recurrent glioblastoma: An update. CNS Oncol. 4, 91–104 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mrugala MM, Advances and challenges in the treatment of glioblastoma: A clinician’s perspective. Discov. Med 15, 221–230 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reardon DA, Wen PY, Wucherpfennig KW, Sampson JH, Immunomodulation for glioblastoma. Curr. Opin. Neurol 30, 361–369 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricklefs FL, Alayo Q, Krenzlin H, Mahmoud AB, Speranza MC, Nakashima H, Hayes JL, Lee K, Balaj L, Passaro C, Rooj AK, Krasemann S, Carter BS, Chen CC, Steed T, Treiber J, Rodig S, Yang K, Nakano I, Lee H, Weissleder R, Breakefield XO, Godlewski J, Westphal M, Lamszus K, Freeman GJ, Bronisz A, Lawler SE, Chiocca EA, Immune evasion mediated by PD-L1 on glioblastoma-derived extracellular vesicles. Sci. Adv 4, eaar2766 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Da Ros M, De Gregorio V, Iorio AL, Giunti L, Guidi M, de Martino M, Genitori L, Sardi I, Glioblastoma chemoresistance: The double play by microenvironment and blood-brain barrier. Int. J. Mol. Sci 19, E2879 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomaszewski W, Sanchez-Perez L, Gajewski TF, Sampson JH, Brain tumor microenvironment and host state: Implications for immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res 25, 4202–4210 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer M, Reimand J, Lan X, Head R, Zhu X, Kushida M, Bayani J, Pressey JC, Lionel AC, Clarke ID, Cusimano M, Squire JA, Scherer SW, Bernstein M, Woodin MA, Bader GD, Dirks PB, Single cell-derived clonal analysis of human glioblastoma links functional and genomic heterogeneity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 112, 851–856 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathanson DA, Gini B, Mottahedeh J, Visnyei K, Koga T, Gomez G, Eskin A, Hwang K, Wang J, Masui K, Paucar A, Yang H, Ohashi M, Zhu S, Wykosky J, Reed R, Nelson SF, Cloughesy TF, James CD, Rao PN, Kornblum HI, Heath JR, Cavenee WK, Furnari FB, Mischel PS, Targeted therapy resistance mediated by dynamic regulation of extrachromosomal mutant EGFR DNA. Science 343, 72–76 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel AP, Tirosh I, Trombetta JJ, Shalek AK, Gillespie SM, Wakimoto H, Cahill DP, Nahed BV, Curry WT, Martuza RL, Louis DN, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Suva ML, Regev A, Bernstein BE, Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science 344, 1396–1401 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soeda A, Hara A, Kunisada T, Yoshimura S, Iwama T, Park DM, The evidence of glioblastoma heterogeneity. Sci. Rep 5, 7979 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sottoriva A, Spiteri I, Piccirillo SG, Touloumis A, Collins VP, Marioni JC, Curtis C, Watts C, Tavaré S, Intratumor heterogeneity in human glioblastoma reflects cancer evolutionary dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 110, 4009–4014 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Q, Hu B, Hu X, Kim H, Squatrito M, Scarpace L, deCarvalho AC, Lyu S, Li P, Li Y, Barthel F, Cho HJ, Lin Y-H, Satani N, Martinez-Ledesma E, Zheng S, Chang E, Sauve C-EG, Olar A, Lan ZD, Finocchiaro G, Phillips JJ, Berger MS, Gabrusiewicz KR, Wang G, Eskilsson E, Hu J, Mikkelsen T, DePinho RA, Muller F, Heimberger AB, Sulman EP, Nam D-H, Verhaak RGW, Tumor evolution of glioma-intrinsic gene expression subtypes associates with immunological changes in the microenvironment. Cancer Cell 32, 42–56.e6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nduom EK, Weller M, Heimberger AB, Immunosuppressive mechanisms in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 17 (Suppl. 7), vii9–vii14 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei J, Gabrusiewicz K, Heimberger A, The controversial role of microglia in malignant gliomas. Clin. Dev. Immunol 2013, 285246 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johanns TM, Dunn GP, Applied cancer immunogenomics: Leveraging neoantigen discovery in glioblastoma. Cancer J. 23, 125–130 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Platten M, Ochs K, Lemke D, Opitz C, Wick W, Microenvironmental clues for glioma immunotherapy. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep 14, 440 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cloughesy TF, Mochizuki AY, Orpilla JR, Hugo W, Lee AH, Davidson TB, Wang AC, Ellingson BM, Rytlewski JA, Sanders CM, Kawaguchi ES, Du L, Li G, Yong WH, Gaffey SC, Cohen AL, Mellinghoff IK, Lee EQ, Reardon DA, O’Brien BJ, Butowski NA, Nghiemphu PL, Clarke JL, Arrillaga-Romany IC, Colman H, Kaley TJ, de Groot JF, Liau LM, Wen PY, Prins RM, Neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 immunotherapy promotes a survival benefit with intratumoral and systemic immune responses in recurrent glioblastoma. Nat. Med 25, 477–486 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito H, Nakashima H, Chiocca EA, Molecular responses to immune checkpoint blockade in glioblastoma. Nat. Med 25, 359–361 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiocca EA, Nassiri F, Wang J, Peruzzi P, Zadeh G, Viral and other therapies for recurrent glioblastoma: Is a 24-month durable response unusual? Neuro Oncol. 21, 14–25 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omuro A, DeAngelis LM, Glioblastoma and other malignant gliomas: A clinical review. JAMA 310, 1842–1850 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasek W, Zagożdżon R, Jakobisiak M, Interleukin 12: Still a promising candidate for tumor immunotherapy? Cancer Immunol. Immunother 63, 419–435 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lotze MT, Interleukin 12: Cellular and molecular immunology of an important regulatory cytokine. Introduction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 795, xiii–xix (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trinchieri G, Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol 3, 133–146 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtsinger JM, Johnson CM, Mescher MF, CD8 T cell clonal expansion and development of effector function require prolonged exposure to antigen, costimulation, and signal 3 cytokine. J. Immunol 171, 5165–5171 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Micallef MJ, Ohtsuki T, Kohno K, Tanabe F, Ushio S, Namba M, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Fujii M, Ikeda M, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M, Interferon-γ-inducing factor enhances T helper 1 cytokine production by stimulated human T cells: Synergism with interleukin-12 for interferon-γ production. Eur. J. Immunol 26, 1647–1651 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrett JA, Cai H, Miao J, Khare PD, Gonzalez P, Dalsing-Hernandez J, Sharma G, Chan T, Cooper LJN, Lebel F, Regulated intratumoral expression of IL-12 using a RheoSwitch Therapeutic System (RTS) gene switch as gene therapy for the treatment of glioma. Cancer Gene Ther. 25, 106–116 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vom Berg J, Vrohlings M, Haller S, Haimovici A, Kulig P, Sledzinska A, Weller M, Becher B, Intratumoral IL-12 combined with CTLA-4 blockade elicits T cell–mediated glioma rejection. J. Exp. Med 210, 2803–2811 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leonard JP, Sherman ML, Fisher GL, Buchanan LJ, Larsen G, Atkins MB, Sosman JA, Dutcher JP, Vogelzang NJ, Ryan JL, Effects of single-dose interleukin-12 exposure on interleukin-12-associated toxicity and interferon-γ production. Blood 90, 2541–2548 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Car BD, Eng VM, Lipman JM, Anderson TD, The toxicology of interleukin-12: A review. Toxicol. Pathol 27, 58–63 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L, Morgan RA, Beane JD, Zheng Z, Dudley ME, Kassim SH, Nahvi AV, Ngo LT, Sherry RM, Phan GQ, Hughes MS, Kammula US, Feldman SA, Toomey MA, Kerkar SP, Restifo NP, Yang JC, Rosenberg SA, Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes genetically engineered with an inducible gene encoding interleukin-12 for the immunotherapy of metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res 21, 2278–2288 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atkins MB, Robertson MJ, Gordon M, Lotze MT, DeCoste M, DuBois JS, Ritz J, Sandler AB, Edington HD, Garzone PD, Mier JW, Canning CM, Battiato L, Tahara H, Sherman ML, Phase I evaluation of intravenous recombinant human interleukin 12 in patients with advanced malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res 3, 409–417 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodolfo M, Colombo MP, Interleukin-12 as an adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy. Methods 19, 114–120 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai H, Sun L, Miao J, Krishman S, Lebel F, Barrett JA, Plasma pharmacokinetics of veledimex, a small-molecule activator ligand for a proprietary gene therapy promoter system, in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol. Drug Dev 6, 246–257 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hegi ME, Diserens A-C, Gorlia T, Hamou M-F, de Tribolet N, Weller M, Kros JM, Hainfellner JA, Mason W, Mariani L, Bromberg JEC, Hau P, Mirimanoff RO, Cairncross JG, Janzer RC, Stupp R, MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med 352, 997–1003 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rollinger JM, Ewelt J, Seger C, Sturm S, Ellmerer EP, Stuppner H, New insights into the acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of Lycopodium clavatum. Planta Med. 71, 1040–1043 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilms G, Marchal G, Demaerel PH, Van Hecke P, Baert AL, Gadolinium-enhanced MRI of intracranial lesions. A review of indications and results. Clin. Imaging 15, 153–165 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Booth TC, Ashkan K, Brazil L, Jager R, Waldman AD, Re: Tumour progression or pseudoprogression? A review of post-treatment radiological appearances of glioblastoma. Clin. Radiol 71, 495–496 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandsma D, Stalpers L, Taal W, Sminia P, van den Bent MJ, Clinical features, mechanisms, and management of pseudoprogression in malignant gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 9, 453–461 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brandsma D, van den Bent MJ, Pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse in the treatment of gliomas. Curr. Opin. Neurol 22, 633–638 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ellingson BM, Chung C, Pope WB, Boxerman JL, Kaufmann TJ, Pseudoprogression, radionecrosis, inflammation or true tumor progression? challenges associated with glioblastoma response assessment in an evolving therapeutic landscape. J. Neurooncol 134, 495–504 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galldiks N, Kocher M, Langen K-J, Pseudoprogression after glioma therapy: An update. Expert Rev. Neurother 17, 1109–1115 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reardon DA, Wucherpfennig K, Chiocca EA, Immunotherapy for glioblastoma: On the sidelines or in the game? Discov. Med 24, 201–208 (2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chiocca EA, Smith KM, McKinney B, Palmer CA, Rosenfeld S, Lillehei K, Hamilton A, DeMasters BK, Judy K, Kirn D, A phase I trial of Ad.hIFN-β gene therapy for glioma. Mol. Ther 16, 618–626 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sangro B, Mazzolini G, Ruiz J, Herraiz M, Quiroga J, Herrero I, Benito A, Larrache J, Pueyo J, Subtil JC, Olagüe C, Sola J, Sádaba B, Lacasa C, Melero I, Qian C, Prieto J, Phase I trial of intratumoral injection of an adenovirus encoding interleukin-12 for advanced digestive tumors. J. Clin. Oncol 22, 1389–1397 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mazzolini G, Alfaro C, Sangro B, Feijoó E, Ruiz J, Benito A, Tirapu I, Arina A, Sola J, Herraiz M, Lucena F, Olague C, Subtil J, Quiroga J, Herrero I, Sadaba B, Bendandi M, Qian C, Prieto J, Melero I, Intratumoral injection of dendritic cells engineered to secrete interleukin-12 by recombinant adenovirus in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal carcinomas. J. Clin. Oncol 23, 999–1010 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosewell Shaw A, Porter CE, Watanabe N, Tanoue K, Sikora A, Gottschalk S, Brenner MK, Suzuki M, Adenovirotherapy delivering cytokine and checkpoint inhibitor augments CAR T cells against metastatic head and neck cancer. Mol. Ther 25, 2440–2451 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lang FF, Conrad C, Gomez-Manzano C, Yung WKA, Sawaya R, Weinberg JS, Prabhu SS, Rao G, Fuller GN, Aldape KD, Gumin J, Vence LM, Wistuba I, Rodriguez-Canales J, Villalobos PA, Dirven CMF, Tejada S, Valle RD, Alonso MM, Ewald B, Peterkin JJ, Tufaro F, Fueyo J, Phase I study of DNX-2401 (Delta-24-RGD) oncolytic adenovirus: Replication and immunotherapeutic effects in recurrent malignant glioma. J. Clin. Oncol 36, 1419–1427 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Desjardins A, Gromeier M, Herndon II JE, Beaubier N, Bolognesi DP, Friedman AH, Friedman HS, McSherry F, Muscat AM, Nair S, Peters KB, Randazzo D, Sampson JH, Vlahovic G, Harrison WT, McLendon RE, Ashley D, Bigner DD, Recurrent glioblastoma treated with recombinant poliovirus. N. Engl. J. Med 379, 150–161 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cloughesy TF, Landolfi J, Hogan DJ, Bloomfield S, Carter B, Chen CC, Elder JB, Kalkanis SN, Kesari S, Lai A, Lee IY, Liau LM, Mikkelsen T, Nghiemphu PL, Piccioni D, Walbert T, Chu A, Das A, Diago OR, Gammon D, Gruber HE, Hanna M, Jolly DJ, Kasahara N, McCarthy D, Mitchell L, Ostertag D, Robbins JM, Rodriguez-Aguirre M, Vogelbaum MA, Phase 1 trial of vocimagene amiretrorepvec and 5-fluorocytosine for recurrent high-grade glioma. Sci. Transl. Med 8, 341ra75 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiocca EA, Abbed KM, Tatter S, Louis DN, Hochberg FH, Barker F, Kracher J, Grossman SA, Fisher JD, Carson K, Rosenblum M, Mikkelsen T, Olson J, Markert J, Rosenfeld S, Nabors LB, Brem S, Phuphanich S, Freeman S, Kaplan R, Zwiebel J, A phase I open-label, dose-escalation, multi-institutional trial of injection with an E1B-Attenuated adenovirus, ONYX-015, into the peritumoral region of recurrent malignant gliomas, in the adjuvant setting. Mol. Ther 10, 958–966 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wheeler LA, Manzanera AG, Bell SD, Cavaliere R, McGregor JM, Grecula JC, Newton HB, Lo SS, Badie B, Portnow J, Teh BS, Trask TW, Baskin DS, New PZ, Aguilar LK, Aguilar-Cordova E, Chiocca EA, Phase II multicenter study of gene-mediated cytotoxic immunotherapy as adjuvant to surgical resection for newly diagnosed malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 18, 1137–1145 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woroniecka KI, Rhodin KE, Chongsathidkiet P, Keith KA, Fecci PE, T-cell dysfunction in glioblastoma: Applying a new framework. Clin. Cancer Res 24, 3792–3802 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kmiecik J, Poli A, Brons NHC, Waha A, Eide GE, Enger PØ, Zimmer J, Chekenya M, Elevated CD3+ and CD8+ tumor-infiltrating immune cells correlate with prolonged survival in glioblastoma patients despite integrated immunosuppressive mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment and at the systemic level. J. Neuroimmunol 264, 71–83 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keskin DB, Anandappa AJ, Sun J, Tirosh I, Mathewson ND, Li S, Oliveira G, Giobbie-Hurder A, Felt K, Gjini E, Shukla SA, Hu Z, Li L, Le PM, Allesøe RL, Richman AR, Kowalczyk MS, Abdelrahman S, Geduldig JE, Charbonneau S, Pelton K, Iorgulescu JB, Elagina L, Zhang W, Olive O, McCluskey C, Olsen LR, Stevens J, Lane WJ, Salazar AM, Daley H, Wen PY, Chiocca EA, Harden M, Lennon NJ, Gabriel S, Getz G, Lander ES, Regev A, Ritz J, Neuberg D, Rodig SJ, Ligon KL, Suva ML, Wucherpfennig KW, Hacohen N, Fritsch EF, Livak KJ, Ott PA, Wu CJ, Reardon DA, Neoantigen vaccine generates intratumoral T cell responses in phase Ib glioblastoma trial. Nature 565, 234–239 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siddiqui F, Ehrhart EJ, Charles B, Chubb L, Li C-Y, Zhang X, Larue SM, Avery PR, Dewhirst MW, Ullrich RL, Anti-angiogenic effects of interleukin-12 delivered by a novel hyperthermia induced gene construct. Int. J. Hyperthermia 22, 587–606 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Batchelor TT, Mulholland P, Neyns B, Nabors LB, Campone M, Wick A, Mason W, Mikkelsen T, Phuphanich S, Ashby LS, Degroot J, Gattamaneni R, Cher L, Rosenthal M, Payer F, Jurgensmeier JM, Jain RK, Sorensen AG, Xu J, Liu Q, van den Bent M, Phase III randomized trial comparing the efficacy of cediranib as monotherapy, and in combination with lomustine, versus lomustine alone in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol 31, 3212–3218 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brandes AA, Carpentier AF, Kesari S, Sepulveda-Sanchez JM, Wheeler HR, Chinot O, Cher L, Steinbach JP, Capper D, Specenier P, Rodon J, Cleverly A, Smith C, Gueorguieva I, Miles C, Guba SC, Desaiah D, Lahn MM, Wick W, A phase II randomized study of galunisertib monotherapy or galunisertib plus lomustine compared with lomustine monotherapy in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 18, 1146–1156 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brandes AA, Finocchiaro G, Zagonel V, Reni M, Caserta C, Fabi A, Clavarezza M, Maiello E, Eoli M, Lombardi G, Monteforte M, Proietti E, Agati R, Eusebi V, Franceschi E, AVAREG: A phase II, randomized, noncomparative study of fotemustine or bevacizumab for patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 18, 1304–1312 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brem H, Piantadosi S, Burger PC, Walker M, Selker R, Vick NA, Black K, Sisti M, Brem S, Mohr G, Muller P, Morawetz R, Schold SC; The Polymer-brain Tumor Treatment Group, Placebo-controlled trial of safety and efficacy of intraoperative controlled delivery by biodegradable polymers of chemotherapy for recurrent gliomas. Lancet 345, 1008–1012 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chamberlain MC, Johnston SK, Salvage therapy with single agent bevacizumab for recurrent glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol 96, 259–269 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Field KM, Simes J, Nowak AK, Cher L, Wheeler H, Hovey EJ, Brown CS, Barnes EH, Sawkins K, Livingstone A, Freilich R, Phal PM, Fitt G; CABARET COGNO investigators, Rosenthal MA, Randomized phase 2 study of carboplatin and bevacizumab in recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 17, 1504–1513 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, Mikkelsen T, Schiff D, Abrey LE, Yung WK, Paleologos N, Nicholas MK, Jensen R, Vredenburgh J, Huang J, Zheng M, Cloughesy T, Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol 27, 4733–4740 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, Duic P, Royce C, Stroud I, Garren N, Mackey M, Butman JA, Camphausen K, Park J, Albert PS, Fine HA, Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol 27, 740–745 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stupp R, Wong ET, Kanner AA, Steinberg D, Engelhard H, Heidecke V, Kirson ED, Taillibert S, Liebermann F, Dbaly V, Ram Z, Villano JL, Rainov N, Weinberg U, Schiff D, Kunschner L, Raizer J, Honnorat J, Sloan A, Malkin M, Landolfi JC, Payer F, Mehdorn M, Weil RJ, Pannullo SC, Westphal M, Smrcka M, Chin L, Kostron H, Hofer S, Bruce J, Cosgrove R, Paleologous N, Palti Y, Gutin PH, NovoTTF-100A versus physician’s choice chemotherapy in recurrent glioblastoma: A randomised phase III trial of a novel treatment modality. Eur. J. Cancer 48, 2192–2202 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taal W, Oosterkamp HM, Walenkamp AME, Dubbink HJ, Beerepoot LV, Hanse MCJ, Buter J, Honkoop AH, Boerman D, de Vos FYF, Dinjens WNM, Enting RH, Taphoorn MJB, van den Berkmortel FWPJ, Jansen RLH, Brandsma D, Bromberg JEC, van Heuvel I, Vernhout RM, van der Holt B, van den Bent MJ, Single-agent bevacizumab or lomustine versus a combination of bevacizumab plus lomustine in patients with recurrent glioblastoma (BELOB trial): A randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 15, 943–953 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, Taphoorn M, Sahm F, Harting I, Brandes AA, Taal W, Domont J, Idbaih A, Campone M, Clement PM, Stupp R, Fabbro M, Le Rhun E, Dubois F, Weller M, von Deimling A, Golfinopoulos V, Bromberg JC, Platten M, Klein M, van den Bent MJ, Lomustine and bevacizumab in progressive glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med 377, 1954–1963 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wick W, Puduvalli VK, Chamberlain MC, van den Bent MJ, Carpentier AF, Cher LM, Mason W, Weller M, Hong S, Musib L, Liepa AM, Thornton DE, Fine HA, Phase III study of enzastaurin compared with lomustine in the treatment of recurrent intracranial glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol 28, 1168–1174 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Okada H, Weller M, Huang R, Finocchiaro G, Gilbert MR, Wick W, Ellingson BM, Hashimoto N, Pollack IF, Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Herold-Mende C, Nayak L, Panigrahy A, Pope WB, Prins R, Sampson JH, Wen PY, Reardon DA, Immunotherapy response assessment in neuro-oncology: A report of the RANO working group. Lancet Oncol. 16, e534–e542 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, Cloughesy TF, Sorensen AG, Galanis E, Degroot J, Wick W, Gilbert MR, Lassman AB, Tsien C, Mikkelsen T, Wong ET, Chamberlain MC, Stupp R, Lamborn KR, Vogelbaum MA, van den Bent MJ, Chang SM, Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: Response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J. Clin. Oncol 28, 1963–1972 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suchorska B, Weller M, Tabatabai G, Senft C, Hau P, Sabel MC, Herrlinger U, Ketter R, Schlegel U, Marosi C, Reifenberger G, Wick W, Tonn JC, Wirsching H-G, Complete resection of contrast-enhancing tumor volume is associated with improved survival in recurrent glioblastoma—Results from the DIRECTOR trial. Neuro Oncol. 18, 549–556 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wann A, Tully PA, Barnes EH, Lwin Z, Jeffree R, Drummond KJ, Gan H, Khasraw M, Outcomes after second surgery for recurrent glioblastoma: A retrospective case-control study. J. Neurooncol 137, 409–415 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Komita H, Zhao X, Katakam AK, Kumar P, Kawabe M, Okada H, Braughler JM, Storkus WJ, Conditional interleukin-12 gene therapy promotes safe and effective antitumor immunity. Cancer Gene Ther. 16, 883–891 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kenny K, U.S. Patent 8,639,013, (2014).

- 74.Nagy ML, Hanifi A, Tirupsur A, Wong G, Fang J, Hoe N, Au Q, Padmanabhan RK, Efficient large-scale cell classification and analysis for MultiOmyx™ assays: A deep learning approach. Cancer Res. 78, 2256 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gerdes MJ, Sevinsky CJ, Sood A, Adak S, Bello MO, Bordwell A, Can A, Corwin A, Dinn S, Filkins RJ, Hollman D, Kamath V, Kaanumalle S, Kenny K, Larsen M, Lazare M, Li Q, Lowes C, McCulloch CC, McDonough E, Montalto MC, Pang Z, Rittscher J, Santamaria-Pang A, Sarachan BD, Seel ML, Seppo A, Shaikh K, Sui Y, Zhang J, Ginty F, Highly multiplexed single-cell analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cancer tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 110, 11982–11987 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sood A, Miller AM, Brogi E, Sui Y, Armenia J, McDonough E, Santamaria-Pang A, Carlin S, Stamper A, Campos C, Pang Z, Li Q, Port E, Graeber TG, Schultz N, Ginty F, Larson SM, Mellinghoff IK, Multiplexed immunofluorescence delineates proteomic cancer cell states associated with metabolism. JCI Insight 1, 87030 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Histo- and immunopathological features of tumors before and after Ad–RTS–hIL-12 + VDX treatment.

Table S1. Neuropathologic analysis of vascular proliferation in GBMs before and after Ad–RTS–hIL-12 injection + VDX.