Abstract

Incidence of cachexia is highly prevalent in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC); advanced disease stage directly correlates with decreased muscle and fat mass in PDAC patients. The pancreatic tumor microenvironment is central to the release of systemic factors that govern lipolysis, proteolysis, and muscle and fat degeneration leading to the cachectic phenotype in cancer patients. The current study explores the role of macrophages, a key immunosuppressive player in the pancreatic tumor microenvironment, in regulating cancer cachexia. We observed a negative correlation between CD163-positive macrophage infiltration and muscle-fiber cross sectional area in human PDAC patients. To investigate the role of macrophages in myodegeneration, we utilized conditioned media transplant assays and orthotopic models of PDAC-induced cachexia in immune-competent mice with and without macrophage depletion. We observed that macrophage-derived conditioned medium, in combination with tumor cell-conditioned medium, synergistically promoted muscle atrophy through STAT3 signaling. Furthermore, macrophage depletion attenuated systemic inflammation and muscle wasting in pancreatic tumor-bearing mice. Targeting macrophage-mediated STAT3 activation or macrophage-derived interleukin-1 alpha or interleukin-6 diminished myofiber atrophy. Taken together, the current study identified the critical association between macrophages and cachexia phenotype in pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: Macrophages, cancer cachexia, STAT3, IL-6, Pancreatic Cancer

1. Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related annual deaths in the United States, with a five-year patient survival rate of 8% [1]. The poor prognosis is due to its late diagnosis, rapid progression, and chemo-resistance. Cachexia, continual weight loss due to muscle and fat breakdown, is one of the important hallmarks of pancreatic cancer that afflicts nearly eighty percent of pancreatic cancer patients and is associated with poor quality of life, poor prognosis and mortality [2–4]. In particular, skeletal muscles in PDAC patients display a progressive loss of muscle mass with or without loss of fat mass that translates into reduced muscle strength, fatigue, and reduced physical function [5, 6]. Additionally, cachectic phenotype predisposes patients toward reduce tolerance to chemotherapy. In the context of immune system, systemic factors such as CRP (c-reactive protein), IL-6, and IL-10 have been associated with weight loss, cachexia, and poor prognosis of cancer patients [7]. However, the role of immunosuppressive subsets in promoting the cachectic phenotype in PDAC remains elusive.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are central to the immunosuppressive cascades in PDAC. TAMs assist in extracellular matrix remodeling, while limiting tumor antigen recognition/presentation and consequent cytotoxic T cell response [8–11]. Interestingly, TAMs, specifically M2 macrophage subtypes, are also the key reservoirs of immunosuppressive cytokines, including IL-6, TNFα, IL-1, and IL-10. These cytokines are well-established cachectic factors for several cancer models [12–14]. The direct contribution of TAMs in the etiology of pancreatic cancer-associated cachexia however remains understudied.

To date, the only evidence for the involvement of macrophages in cachexia came from Martignoni et al., where they highlight a correlation between CD68+ positive cells in liver with cancer-related cachexia in pancreatic cancer [15]. However, a recent report indicates that macrophages prevent against the loss of adipose tissue during cachexia in the preclinical model of hepatocellular carcinoma [16]. These contradictory studies highlight the need to unravel the impact of macrophage on muscle atrophy. Investigating the role of macrophages in cachexia may yield novel targets for the effective management of the cachectic phenotype in PDACs. Hence, we explored the role of macrophages in cachexia in a preclinical model of pancreatic cancer. Our in vitro and in vivo studies document the direct effect of macrophages on myotube degradation and tumor growth in an orthotopic implantation model of pancreatic cancer in immunocompetent mice. Mechanistic studies further revealed that attenuation of the STAT3 phosphorylation underlies the cachectic phenotype in skeletal muscle of macrophage-depleted tumor-bearing mice. Taken together, this is the first study that unravels a direct role of macrophages on muscle wasting in a preclinical model of pancreatic cancer.

2. Material and methods

2. 1. Mice, Cells, and Reagents

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson laboratories and maintained at UNMC, as previously described [17]. A C57BL/6J-congenic KrasG12D; Trp53R172H/+; Pdx-1-Cre (KPC) mouse tumor-derived cell line was kindly provided by Dr. David Tuveson (CSHL) and maintained in DMEM media containing 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 mg/mL). C2C12 cells were purchased from ATCC and maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS as previously described [18]. Anti-IL-6 (MAB406) and Anti-IL-1α (AF-400-NA) antibodies were purchased from R&D Systems. Anti-CD163 for immunohistochemistry was purchased from Novus Biologicals. Mice were cared in accordance with institutional IACUC guidelines.

2.2. Tumor growth and macrophage depletion in mice

C57BL/6J-congenic KPC mouse-derived tumor cells (KPC1245; 5×104 cells/30μl) were implanted in the pancreas of eight to nine-weeks-old female immunocompetent C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory) using the established protocols [19, 20]. Post implantation mice were randomized into two experimental groups (n=10 mice/group), and treated with Clodronate liposomes (100 μl, i.v) three times per week as described previously[21]. Subsequently, mice were monitored for tumor growth and euthanized when reached the euthanasia criteria as per the institutional IACUC guidelines. Tumor volume was measured and calculated as described previously [22].

2.3. Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry staining

Primary tumors were harvested from tumor-bearing mice and processed for flow cytometry as described previously[23]. Flow cytometry data was analyzed using FlowJo Version 8.8.7 software (TreeStar). Also, gastrocnemius muscle was collected from tumor-bearing mice and fixed with 10% (vol/vol) formalin for 24 hr at room temperature. Muscle sections were processed for protein carbonylation and nitrosylation staining and imaged using a Leica microscope with LSF processing system [24]. Protein nitrosylation was evaluated by using Anti-3-Nitrotyrosine antibody [39B6] (ab61392) from Abcam. For immuno-staining, CD163 positive cells were counted at least in three fields per muscle specimen.

2.4. Isolation of bone marrow-derived macrophages and preparation of conditioned media from M2-polarized macrophages

Primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were isolated from the 6–8 week old C57BL/6J mice[25]. For macrophage differentiation, BMDMs were cultured in DMEM media containing 20% of L929-derived supernatant. Differentiated macrophages were polarized to M2-macrophages using IL-4 (20ng/ml) treatment. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and cultured in serum-free DMEM media for 24 hours.

2.5. C2C12 differentiation and CM preparation

C2C12 cells were differentiated into myotubes [26, 27]. Tumor cell-conditioned medium was prepared by culturing KPC mice-derived tumor cells at 70% confluence in the serum-free DMEM for 24 hours. Subsequently, the medium was harvested and filtered (0.2 μm pore-sized filter). We treated differentiated myotubes with conditioned media derived from the macrophages, tumor cells (KPC1245), or a mixture of both media in equal proportions. A complete DMEM medium was used as the control for the study.

2.6. Rotarod test and grip-strength measurement

We performed the rotarod test by utilizing Rotamex-5 (Columbus Instruments, OH, USA) and measured fore-limb grip strength of mice by using a grip strength meter (Columbus Instruments, OH, USA) as described previously[18].

2.7. Western Blot analyses

Expression of Atrogin, MuRF1, MyHC, STAT3, and pSTAT3 was determined using western blot analysis. Atrogin (mouse monoclonal IgG1, 1:500) and MuRF1 (mouse monoclonal IgG1, 1:1000) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz, CA, USA. STAT3 (rabbit monoclonal IgG, 1:1000) and pSTAT3 (rabbit monoclonal IgG, 1:1000) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). MyHC (MF-20, mouse monoclonal IgG, 1:000) was obtained from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, USA. The anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (ab61392, mouse monoclonal IgG2a, 1:100 dilution) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK).

2. 8. Measurement of cytokine levels

Cytokine levels in the blood plasma of tumor-bearing mice were measured by utilizing ELISA assay kits (BioLegend Inc, San Diego, CA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.9. Myotube-width and muscle-fiber cross sectional area measurement

Myotube-width measurement was performed by using Image J software. For each myotube, at least six measurements were recorded and average values of minimum 10 myotubes per field have been presented. Muscle-fiber cross sectional area was measured by using ImageJ, all the fibers present in at least three field were measured.

2.10. Statistical Analyses

Tumor volume and weight measurements were analyzed using Student’s t-test analyses. One-way ANOVA analyses (Tukey’s post-hoc test) were performed for the comparison between different groups. All p values of ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Macrophages augment pancreatic tumor cell-induced myotube atrophy

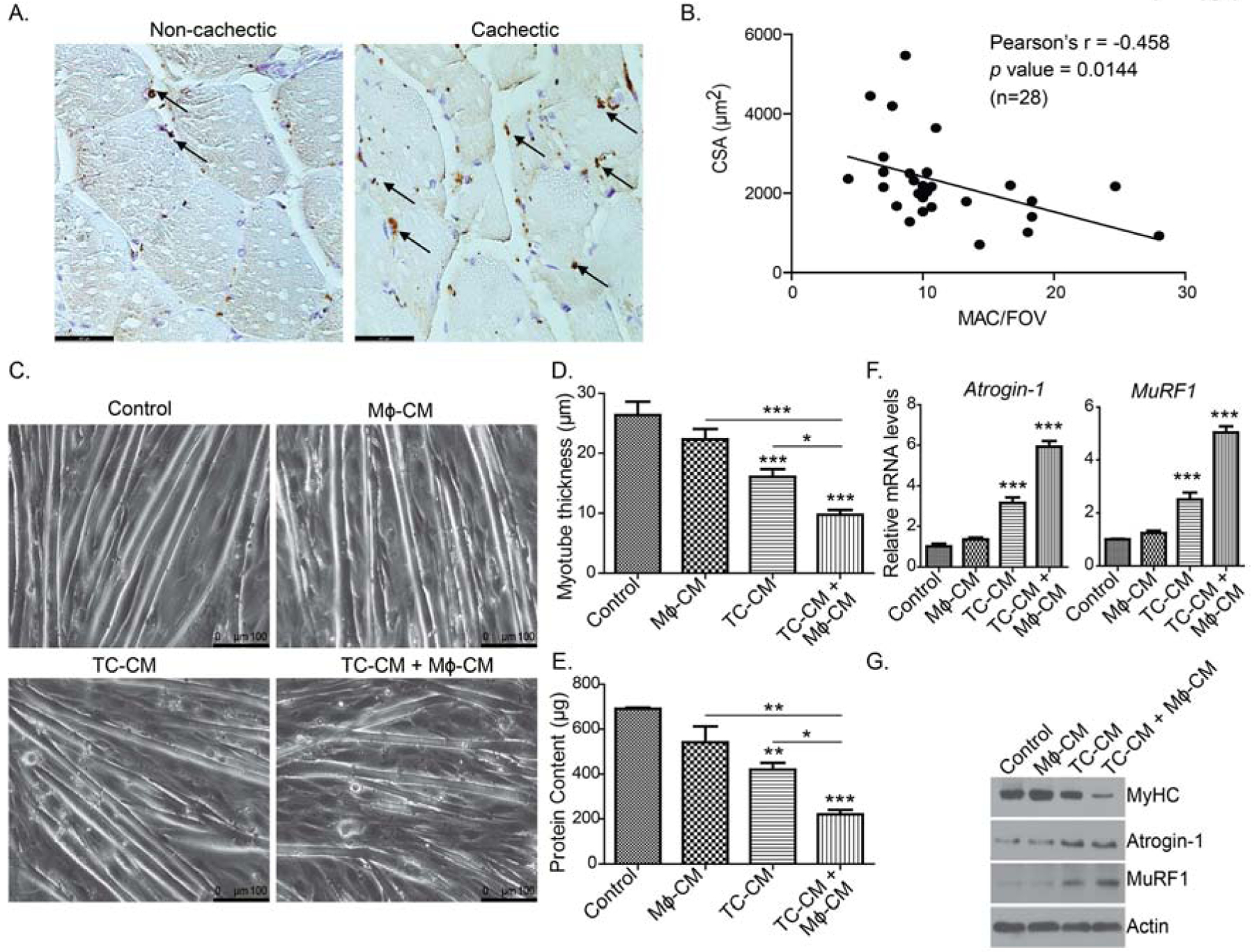

Muscle atrophy is a key hallmark feature of cancer cachexia. Macrophages are important for muscle repair [28]. These cells are present at the injury site to activate satellite cells for the repairing process [29–32]. To investigate the role of macrophages in muscle atrophy, we first investigated if macrophage recruitment in human pancreatic cancer patient skeletal muscles correlated with cachexia. Hence, we examined macrophage infiltration in the skeletal muscle of cachectic and non-cachectic PDAC patients by using CD163, a marker for pro-inflammatory M2 macrophages that are prevalent in cancer patients. We recorded notable numbers of M2 macrophages in the skeletal muscle from PDAC patients (Fig.1A). We also observed a negative correlation between macrophage infiltration and muscle cross-sectional area, suggesting a potential role of M2 macrophages in muscle wasting in PDAC (Fig.1B). We next assayed if M2-polarized macrophages contributed directly to myodegeneration in culture conditions. The C2C12 myotube atrophy assays offer an ideal system to study direct effects of any treatments on myofiber atrophy. Thus, to study the role of macrophages in cancer-induced muscle wasting, we utilized the C2C12 myotube atrophy assay system along with M2-polarized macrophages (hereinafter referred to as macrophages) [26]. In the present study, we noted pronounced myotube degeneration upon combined treatment with conditioned media (CM) from KPC1245 PDAC tumor cells and macrophages, as compared to control media or CM from macrophages or KPC cells alone (Fig.1C–D). Correspondingly, we observed reduced protein content in myotubes treated with combined CM from tumor cells and macrophages (Fig. 1E). Subsequently, we investigated key determinants of myotube atrophy. We evaluated the expression of skeletal muscle atrophy markers, i.e., myosin heavy chain (MyHC), a core myofibrillar protein, and muscle-specific E3 ubiquitin ligases Atrogin-1 (also known as MAFbx/FBXO32) and muscle RING finger protein-1 (MuRF1) at mRNA and protein levels in control and CM-treated C2C12 myotubes (Fig.1F–G) [33, 34]. Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are the key regulator of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation in skeletal muscle. Herein, we observed a significant up regulation of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 transcripts and protein levels in the C2C12 myotubes upon treatment with tumor cell-M2 macrophage combined CM as compared to controls. In contrast, we observed attenuated protein levels of myosin heavy chain (MyHC) in tumor cell-M2 macrophage combined CM-treated myotubes (Fig.1G). Together, our data demonstrate that macrophages and tumor cells together can accelerate myotube atrophy under culture conditions.

Figure 1: Macrophages potentiate myodegeneration in pancreatic cancer.

(A), Representative IHC images showing CD163-stained M2 macrophage recruitment in cachectic and non-cachectic human pancreatic cancer patient skeletal muscles. (B), A dot-plot representing a negative correlation between muscle fiber cross-sectional are (CSA) and CD163+ macrophage numbers in a given field of view (MAC/FOV). Scale bar is 46.7μm. (C), Bright-field images of C2C12-derived myotubes treated with conditioned media from KPC1245 tumor cells (TC-CM) or M2-polarized macrophages (Mϕ-CM), or a combination of both. (D), myotube thickness for conditions represented in panel (C). Scale bar is 100μm. (E), Total protein content in different conditioned media-treated myotubes. (F), The mRNA expression levels of Atrogin-1 (Fbox32) and MuRF1 (Trim 63) by qPCR analysis. (F) Protein expression of myosin heavy chain (MyHC), Atrogin-1, and MuRF1 in different conditioned media-treated C2C12-derived myotubes. Beta-actin was used as an internal control. * p < 0 .05, ** p < 0 .01, *** p < 0.001, compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

3.2. Macrophage depletion limits pancreatic tumor growth in KPC tumor-bearing mice

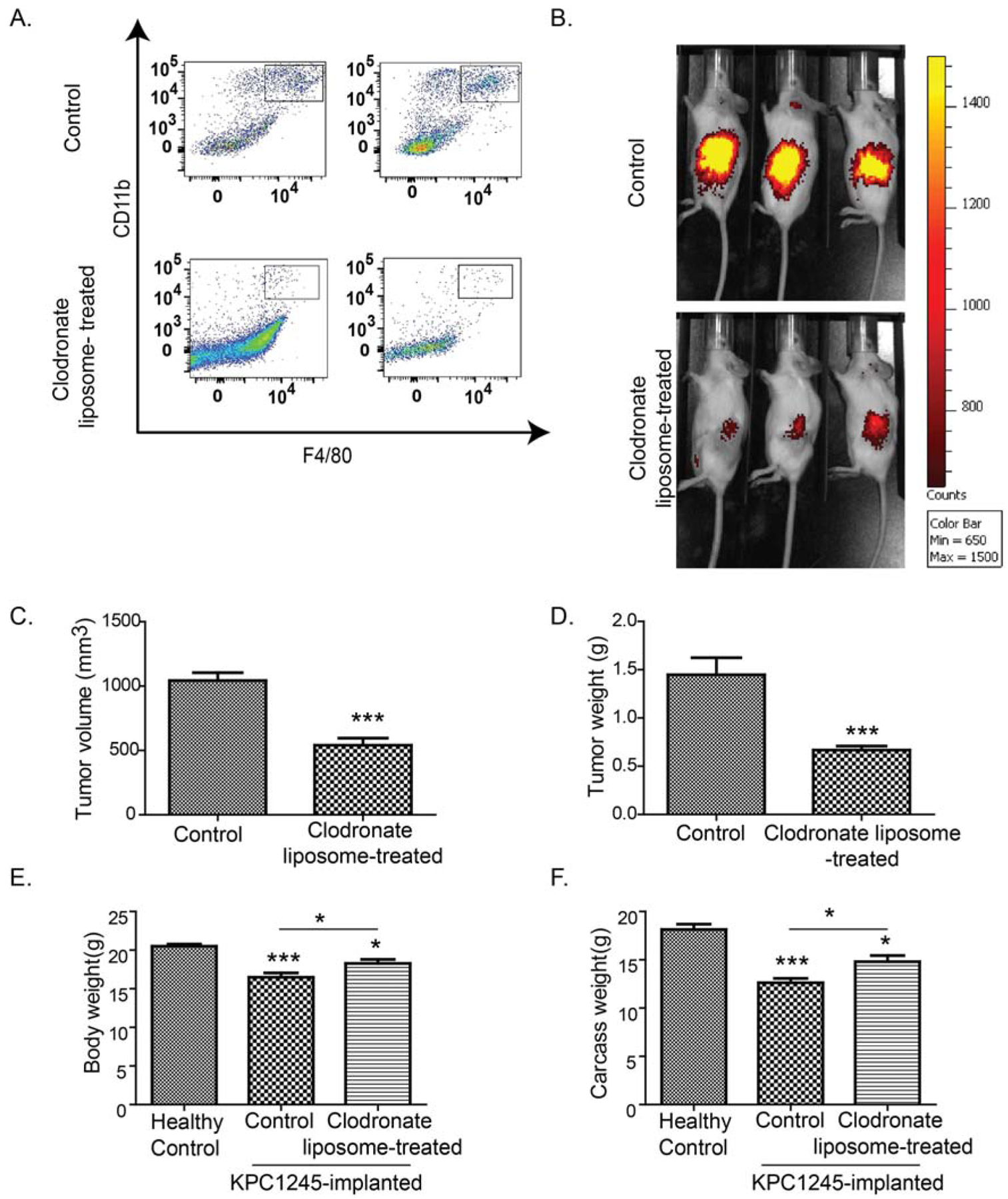

Next, we examined the effect of macrophage depletion on the muscle physiology in pancreatic tumor-bearing mice. Clodronate liposome-mediated macrophage depletion is a common strategy for studying the impact of the macrophage in tumor models [35, 36]. Hence, we used clodronate liposomes in a syngeneic orthotopic model of pancreatic cancer, wherein C57BL/6J-congenic KPC mouse tumor-derived cell line was injected into the pancreas of C57BL/6J mice. We noted a marked reduction in CD11b+F4/80+macrophages in the tumor (Fig. 2A)upon treatment with clodronate liposomes. We first examined the pancreatic tumor size in live mice in the presence and absence of macrophages by imaging for 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2DG) uptake. Rapidly proliferating tumor cells have high flux through glycolysis and takes up 2DG at faster rate.[37] An analog of 2DG, 18F labeled 2-Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) is used for clinical diagnosis of tumors with PET imaging [38]. Our imaging studies documented a significant reduction in 2DG uptake in clodronate liposome-treated mice tumors as compared to tumors from control saline-treated mice (Fig. 2B). We also observed that macrophage depletion caused a significant reduction in tumor volume and weight, measured upon necropsy as compared to control mice (Fig. 2C–D). Also, macrophage depletion significantly restored body weight and carcass weight of tumor-bearing mice as compared to controls (Fig. 2E–F).

Figure 2: Macrophage depletion reduces tumor burden in a syngeneic orthotopic mouse model of pancreatic cancer.

KPC1245 cells were orthotopically implanted into the pancreas of C57BL/6 albino mice. After seven days of implantation, mice were treated with clodronate-liposomes to deplete macrophages (Mϕ) or control liposomes. After two weeks of treatment, mice were sacrificed. (A), Representative dot plots demonstrate macrophage depletion in clodronate-liposome-treated mice. (B), Representative images of near-infrared dye-conjugated 2-DG uptake in control and clodronate-liposome- treated tumor-bearing mice. (C-D), Bar charts represents average tumor volume (C) and tumor weight (D) in control and clodronate-liposome-treated mice at the time of necropsy. (E), Bar graph represents body weight of healthy controls, KPC1245 tumor-bearing mice, and KPC1245 tumor-bearing mice treated with clodronate-liposomes. (F), Bar graph represents carcass weight of healthy controls, tumor-bearing mice, and tumor-bearing mice treated with clodronate-liposomes at the time of necropsy. Values are presented as average ± SEM, * p< 0.05, *** p < 0.001, compared by Student’s t-test in C-D, or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test in E-F.

3.3. Macrophage depletion restores body strength and skeletal muscle function

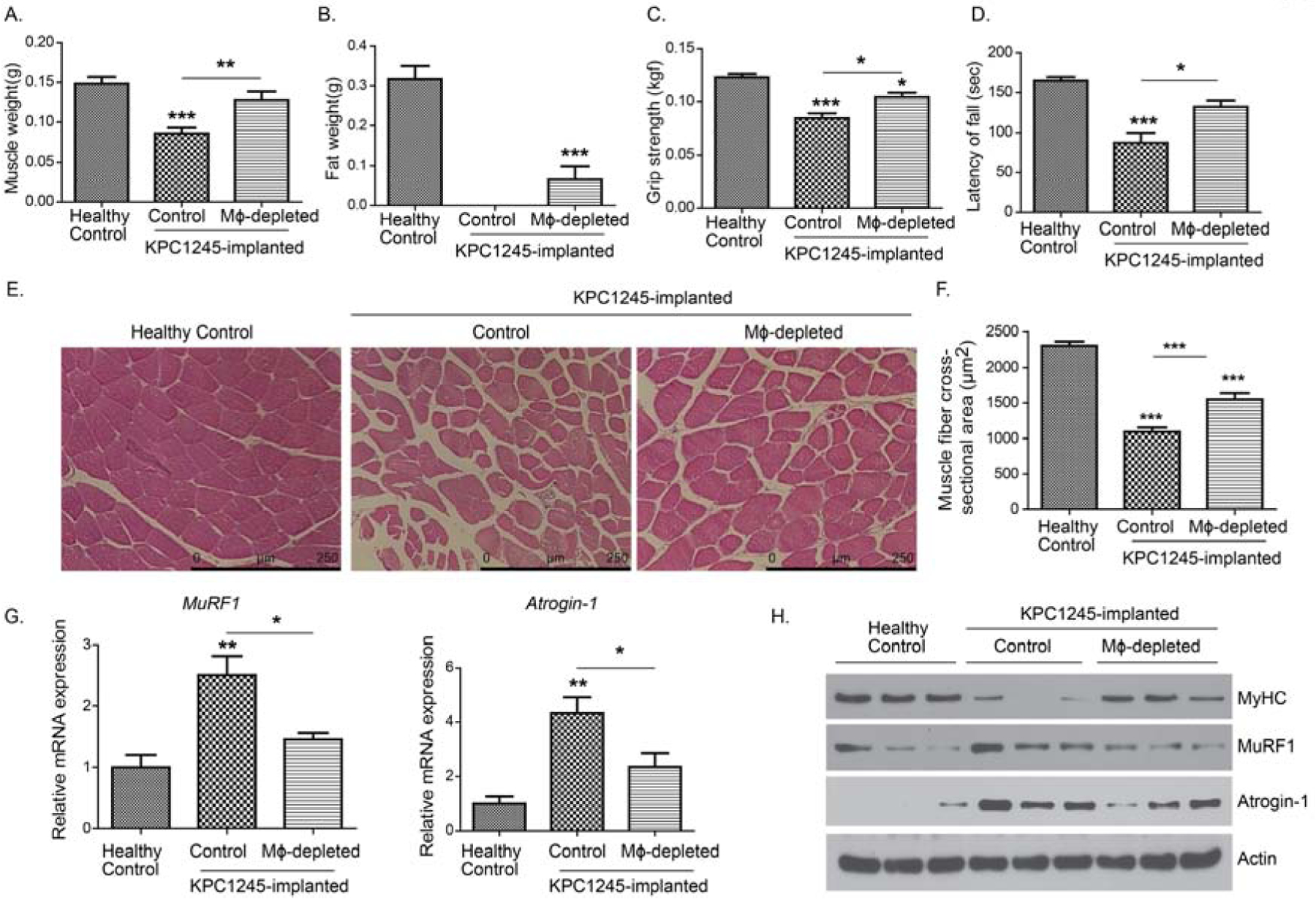

Clinical manifestation of cancer cachexia is characterized by wasting of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. Hence, we assessed if macrophage depletion could abrogate muscle and fat loss in pancreatic tumor-bearing mice. To achieve this, we measured the weight of the gastrocnemius muscle and epididymal fat in tumor-bearing mice. Pancreatic tumor-bearing mice experienced nearly two-third loss in gastrocnemius muscle mass as compared to healthy non-tumor bearing mice (Fig. 3A). In parallel, these mice displayed complete abrogation of epididymal fat as compared to the healthy control mice (Fig. 3B). Of note, macrophage depletion with clodronate liposomes displayed a significant increase in muscle and epididymal fat weight in tumor-bearing mice. Next, we performed grip strength and rotarod performance tests to estimate maximum isometric forelimb strength and endurance of tumor-bearing mice, respectively. We observed reduced grip strength and latency-to-fall in the rotarod test in tumor-bearing mice as compared to healthy controls (Fig. 3C–D). In contrast, macrophage depletion significantly increased the grip strength and latency-to-fall in tumor-bearing mice. We also evaluated the muscle fiber cross-sectional area in gastrocnemius muscles. Gastrocnemius muscles from tumor-bearing mice displayed a significantly reduced cross-sectional area as compared to healthy mice (Fig. 3E–F). However, macrophage-depletion significantly restored myofiber cross-sectional area in tumor-bearing mice. To further confirm muscle wasting, we examined muscle atrophy markers, i.e., MyHC, Atrogin-1, and MuRF1 in the gastrocnemius muscle by performing immunoblot analyses and real-time PCR assays. As shown in Fig. 3G–H, gastrocnemius muscle from tumor-bearing mice displayed increased expression of MuRF1 and Atrogin-1 at both mRNA and protein levels. Also, the muscle from tumor-bearing mice displayed decreased MyHC expression. In contrast, macrophage depletion significantly reduced the expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1, and restored MyHC levels in the gastrocnemius muscle of tumor-bearing mice.

Figure 3: Macrophage depletion reduces the cachectic phenotype in a syngeneic orthotopic model of pancreatic cancer.

KPC1245 cells were orthotopically implanted in the pancreas of C57BL/6 albino mice. After seven days of implantation, mice were treated with clodronate liposomes or control liposomes. After two weeks of treatment, mice were sacrificed. Healthy control mice were also sacrificed as controls. (A-B), Bar charts represent average gastrocnemius muscle weight (A) or epididymal fat weight (B) at the time of necropsy. (B-C), Bar charts represent grip strength (C) and latency of fall (D) measured after 12 days of treatment by utilizing mouse grip strength meter and Rotarod, respectively. (E), H&E staining of gastrocnemius muscle from healthy controls, and control liposome-treated and clodronate liposomes-treated tumor-bearing mice. Scale bar is 250μm. (F), average muscle fiber cross-sectional area of healthy controls, and control liposome-treated and clodronate liposomes-treated tumor-bearing mice. (G), Relative mRNA expression of Atrogin-1 (Fbox32) and MuRF1 (Trim 63) in gastrocnemius muscles from different groups. (H), Protein expression of myosin heavy chain (MyHC), Atrogin-1, and MuRF1 in gastrocnemius from different groups. Beta-actin was used as an internal control. Values are presented as average ± SEM, * p< 0.05, ** p < 0 .01, *** p < 0.001, compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

3.4. Gastrocnemius muscles from macrophage-depleted tumor-bearing mice exhibit reduced oxidative stress

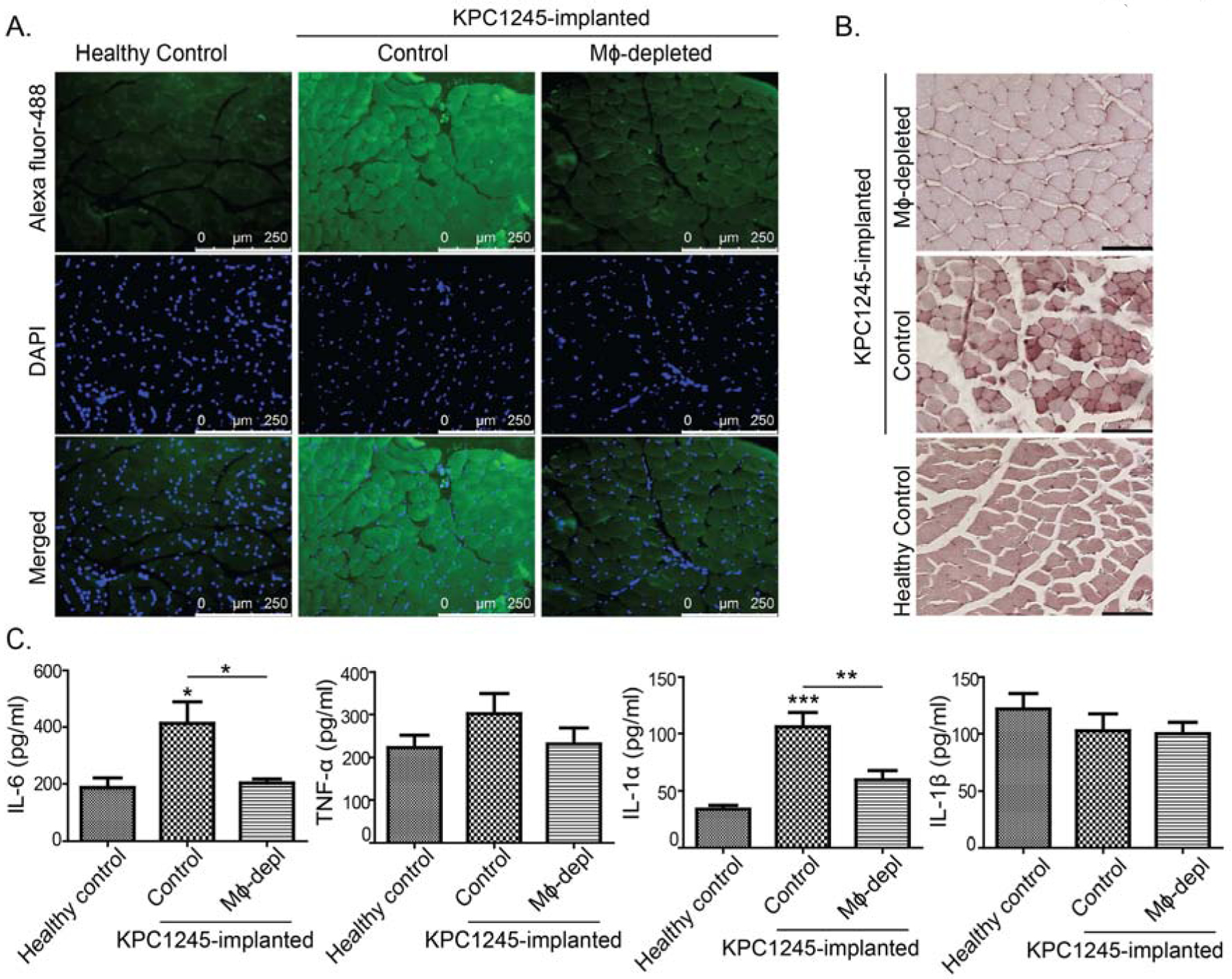

Cancer patients exhibit increased protein oxidation in skeletal muscles suggesting a crucial role of free radicals in muscle wasting in malignant diseases[39, 40]. Macrophage-derived phagocytic processes cause a respiratory burst, which translates into the production of free radicals in inflammatory insults [41, 42]. Hence, we hypothesized that macrophage-derived free radicals alter protein oxidation in skeletal muscle to impart muscle wasting. To test our hypothesis, we examined protein carbonylation and nitrosylation by performing immunofluorescence staining of muscle tissue sections. Muscles from tumor-bearing mice demonstrated increased staining for the carbonyl content and protein nitrosylation as compared to the healthy mice (Fig. 4A–B). These data suggest an intensified oxidative stress in KPC1245 tumor-bearing mice. In contrast, muscles from macrophage-depleted mice depicted reduced levels of carbonyl content. However, there was no difference in protein nitrosylation between different groups. Subsequently, we investigated pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are associated with reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β using ELISA [43–45]. In our study tumor-bearing mice demonstrated increased circulatory levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β as compared to healthy counterparts (Fig. 4C–E). However, macrophage depletion significantly abolished IL-6 and IL-1α levels in the plasma of tumor-bearing mice compared to cancer control group. However, there were no significant differences in TNF-α and IL-1β levels across different treatment groups.

Figure 4: Macrophage depletion reduces oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine production in tumor-bearing mice.

KPC1245 cell were orthotopically implanted into pancreas of C57BL/6 albino mice. After seven days of implantation, mice were treated with clodronate liposomes (macrophage depleted; Mϕ-depleted) or control liposomes (control). After two weeks of treatment, mice were sacrificed. Healthy control mice were also sacrificed along with the treated mice. (A), Carbonyl content in muscle sections from healthy control, control and Mϕ-depleted mice determined by immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar is 250μm. (B), Protein nitrosylation in muscle tissues was imaged by immunohistochemistry. Scale bar is 100μm. (C), Different cytokines levels in the plasma of healthy controls, and control and Mϕ-depleted (Mϕ-depl) mice, as determined by ELISA. Values are presented as average ± SEM, * p< 0.05, ** p < 0 .01, *** p < 0.001, compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

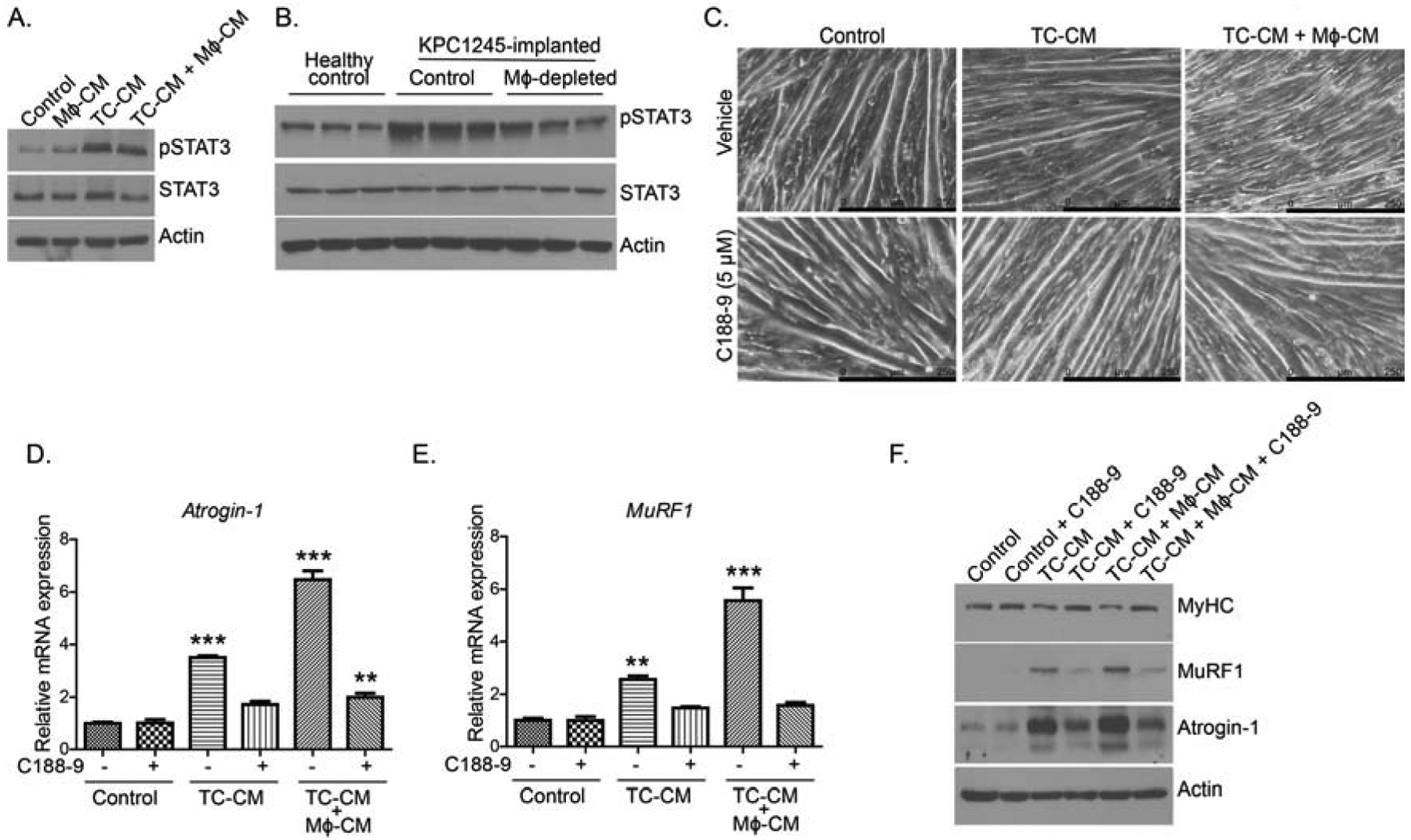

3.5. STAT3 inhibition abrogates myotube atrophy in tumor cell-macrophage CM-treated myotubes

Elevated ROS is known to activate the JAK/STAT pathway [46]. Similarly, cachexia-associated cytokine IL-6 can activate STAT3 for muscle wasting [47]. Once the pro-inflammatory status of muscle was confirmed, we assessed STAT3 levels in the in vitro and in vivo assays. To achieve this, we first examined STAT3 phosphorylation in the C2C12 myotubes treated with different CM. As anticipated, we recorded increased phosphorylation of STAT3 in C2C12 myotubes upon treatment with tumor cell-macrophage combined CM as compared to other treatment groups (Fig.5A). Similarly, we recorded increased STAT3 phosphorylation in the gastrocnemius muscle of tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 5B). Macrophage depletion, however, diminished STAT3 phosphorylation in tumor-bearing mice, as evidenced in the immunoblot analyses (Fig. 5B). To further validate the role of macrophage-mediated STAT3 activation in myodegeneration, we blocked STAT3 activation by using STAT3 inhibitor (C188–9). In the presence of C188–9, tumor cell-macrophage combined CM-treated C2C12 myotubes were thicker in diameter and less atrophic as compared to other treatment groups (Fig. 5C). Subsequently, we confirmed the effect of STAT3 inhibition on myotube atrophy by examining Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression. Tumor cell-macrophage combined CM up-regulated Atrogin-1 and Murf1 expression at mRNA (Fig. 5D–E) and protein levels (Fig. 5F) in the C2C12 myotubes. In contrast, STAT3 inhibition by C188–9 suppressed Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression in tumor cell-macrophage combined CM-treated C2C12 myotubes. Furthermore, MyHC protein levels decreased in C2C12 myotubes upon treatment with tumor cell-macrophage combined CM; however, STAT3 inhibition rescued the MyHC expression (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5: STAT3 regulates macrophage-tumor cell CM-induced myotube atrophy.

(A), Immunoblots of the pSTAT3 and total STAT3 in lysates from different CM-treated myotubes. (B), Immunoblots of the pSTAT3 and total STAT3 in muscle lysates from healthy controls, and control and macrophage-depleted (Mϕ-depleted) tumor-bearing mice. (C), Bright-field images of myotubes treated with different CM with or without STAT3 inhibitor C188–9. Scale bar is 250μm. (D-E), Relative mRNA expression of, Atrogin-1 (D), MuRF1 (E) in the myotubes treated with different CM with or without STAT3 inhibitor C188–9. (F), Immunoblots of myosin heavy chain (MyHC), Atrogin-1, and MuRF1 using lysates from myotubes treated with different CM with and without STAT3 inhibitor. Values are presented as average ± SEM, ** p < 0 .01, *** p < 0.001, compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test in D-E.

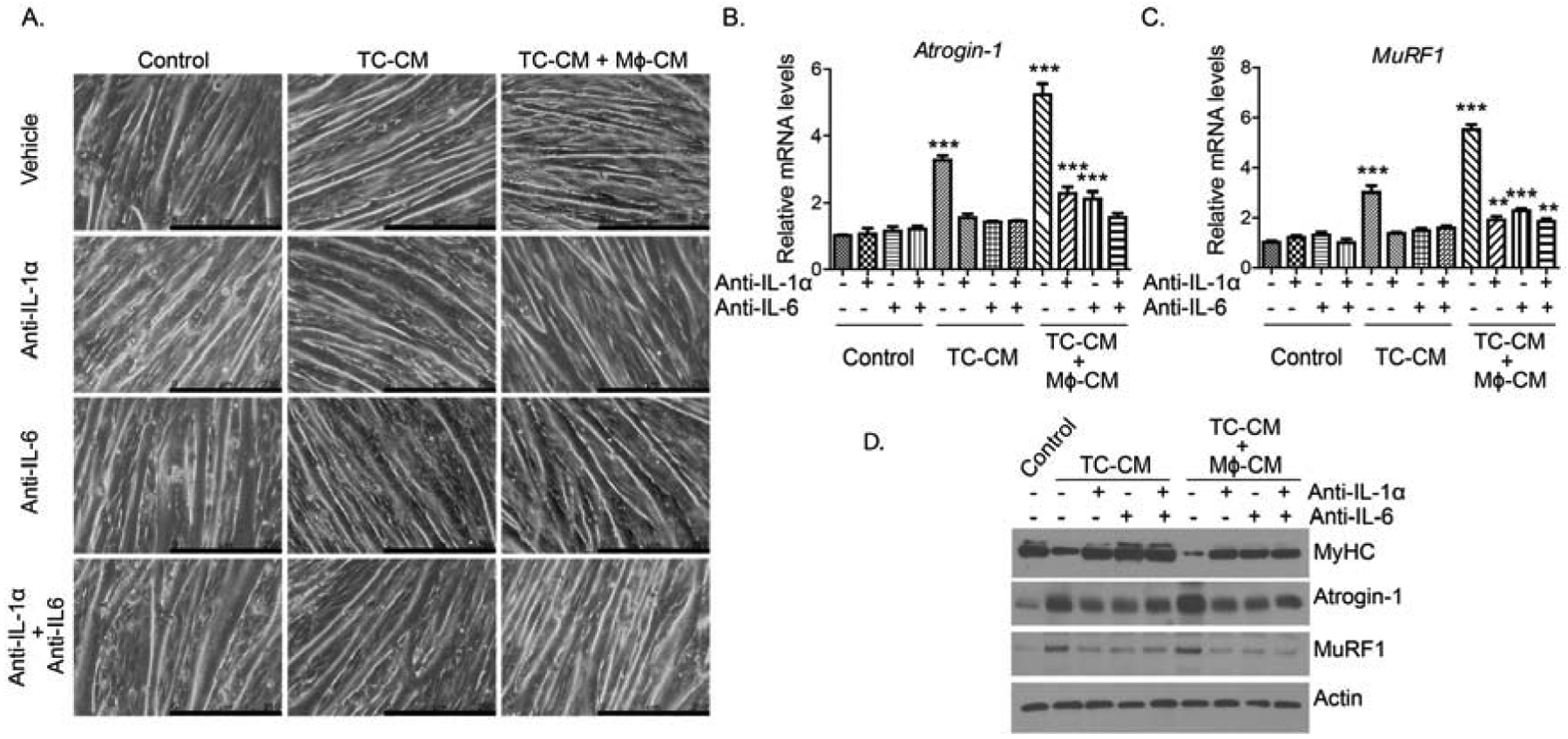

3.6. IL-6 and IL-1α blocking reverses myotube atrophy by tumor cell-macrophage CM

Our studies with an orthotopic mouse model indicated increased inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1α in skeletal muscles of tumor-bearing mice, an effect that was abolished by macrophage depletion. Hence, to investigate if IL-6 or IL-1α contributes to macrophage-mediated myotube atrophy, we performed cytokine neutralization assay in the in vitro system. Herein, we examined the effect of IL-6 or IL-1α neutralization on tumor cell-derived or tumor cell-M2 macrophage combined CM on myotube morphology. We first examined if the neutralization of IL-6 or IL-1α in CM will alter C2C12 myotube morphology. Anti-IL-6 or anti-IL-1α treatments abrogated myotube atrophy in tumor cell CM- or tumor cell-M2 macrophage CM-treated C2C12 cells. Intriguingly, we did not observe any additive effects of combining IL-6 and IL-1α neutralizations. Also, there was no significant difference in myotube thickness between anti-IL-6 and anti-IL-1α treatments (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, we noticed that the neutralization of IL-6 or IL-1α significantly downregulated Atrogin-1 (Fbxo32) and Murf1 transcript levels in tumor cell-macrophage CM-treated myotubes (Fig. 6B–C). Importantly, we did not see any significant additive effects or synergy between anti-IL-6 and anti-IL-1α treatments for Atrogin-1 (Fbxo32) and Murf1 expression. Next, we examined if cytokine neutralization would alter MyHC levels in myotubes. We noticed that tumor cell-M2 macrophage CM treatment significantly downregulated MyHC levels in C2C12 myotubes, which was reversed by anti-IL-6 or anti-IL-1α treatment (Fig. 6D). Here also we did not observe any significant difference between anti-IL-6 and anti-IL-1α treatments, or a synergy when combined together, in up-regulating MyHC protein expression. Together, our study shows that inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1α propel macrophage-mediated muscle atrophy.

Figure 6: IL1-α and IL-6 neutralizing antibodies exhibits protective effect against macrophage-tumor cell CM-induced myotube atrophy.

(A), Bright-field images of myotubes treated with different CM along with IgG controls or neutralizing antibodies against IL-1-α (10ng/ml) and IL-6 (50ng/ml). Scale bar is 250 μm. (B-C) Relative mRNA expression of Atrogin-1 (B) and MuRF1 (C) in the myotubes treated with different CM with or without neutralizing antibodies. (D), Immunoblots of myosin heavy chain (MyHC), Atrogin-1, and MuRF1 using lysates from myotubes treated different CM with or without neutralizing antibodies. Values are presented as average ± SEM, ** p < 0 .01, *** p < 0.001, compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test in C-D.

4. Discussion

Macrophages are one of the key players in tumor microenvironment that assist in tumor growth, invasion, and therapy resistance. Tumor-associated macrophages secrete immunosuppressive factors that impede cytotoxic T cell function and expansion [48]. Recently, a report by Quaranta et al. demonstrated the critical role of macrophages in establishing distant metastatic sites. Macrophage-derived granulin aids in the formation of metastatic niches by modulating resident myofibroblasts in the liver of pancreatic tumor-bearing hosts [49]. Under homeostasis, macrophages assist in muscle repair [30]. However, under chronic inflammation such as Duchene muscular dystrophy (DMD), macrophages abrogate muscle repair processes [50, 51]. To date, the role of the macrophage in PDAC-associated cachexia remains elusive. Our present study examined the contribution of macrophages in imparting muscle atrophy in a preclinical model of PDAC.

In our in vitro study, KPC tumor cell-CM and M2 macrophage-CM demonstrate synergism, compared to either cell type alone, in imparting CM-induced myotube atrophy. Also, the reciprocal association of macrophage accumulation with muscle cross-sectional area in human muscles supports our hypothesis that macrophages contribute to muscle wasting in pancreatic tumor-bearing hosts. Our data further suggest that pancreatic tumor cells augment macrophage-mediated factors that derive muscle atrophy. A previous study has shown that culture medium from endotoxin-activated macrophages can induce weight loss in injected mice [52]. This study highlights macrophage-derived TNF-α as the principal contributor to weight loss in mice. In PDAC, tumor-associated macrophages have an immunosuppressive phenotype and produce a copious amount of GM-CSF, CCL2, and IL-6 cytokines. Of these, the role of IL-6 cytokine and other family members in inducing muscle wasting and cancer-associated cachexia is already well established [53, 54]. Systemic levels of IL-6 correlate with weight loss in non-small-cell lung cancer patients [14].Together, these studies lend support to the hypothesis that macrophage and inflammatory milieu interactions in the tumor microenvironment or at skeletal muscles facilitate cancer cachexia.

Against the backdrop of in vitro data, we next investigated the effect of macrophage depletion on the cachectic phenotype of pancreatic tumor-bearing mice. Herein, we employed clodronate-liposomes to target macrophages in mice. In our study, pancreatic tumor-bearing mice displayed reduced tumor burden upon macrophage depletion. Of note, macrophage depletion restored total protein content and muscle functions in tumor-bearing mice. Subsequent investigations revealed an up-regulation of cachexia-associated proteins such as Atrogin-1, MuRF1, and pSTAT3, but down regulation of MyHC, in the skeletal muscle of pancreatic tumor-bearing mice. However, macrophage depletion restored the levels of muscle atrophy-associated proteins (MyHC, MuRF1, pSTAT3) in the gastrocnemius muscle of pancreatic tumor-bearing mice. Together, the data highlight the critical role of macrophages in altering muscle strength in tumor-harboring mice. Our findings are in agreement with a previous report, which shows that macrophage depletion attenuates IL-2/CD40 therapy-induced cachexia in lung tumor-bearing elderly mice [55]. The study argues that bone marrow-derived macrophages contribute to an increased proportion of tumor-associated macrophages (TAM). Also, IL-2/anti-CD40 immunotherapy induced cachexia in elderly mice but not in young mice. In contrast to this finding, Erdem et al. suggested that macrophages protect against fat loss in the preclinical model of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [56]. The study demonstrates that conditional HIF-1α knockout in macrophages impairs their accumulation in adipose tissue that translates into reduced inflammation and unexpected beneficial function in a murine HCC model. Perhaps macrophages regulate adipose tissue and muscle differentially in tumor-bearing hosts. As our study has focused only on muscle physiology, further studies are warranted to examine the differential effect of macrophage on adipose tissue and muscle in pancreatic tumor-bearing hosts. Nevertheless, we are the first to report that macrophages can modify skeletal muscle structure and strength in pancreatic cancer. In our study, macrophage depletion restored circulating levels of IL-6 and IL-1α in pancreatic tumor-bearing mice as compared to the control group. Furthermore, IL-6 and IL-1α blocking in tumor cell-M2 macrophage-CM rescued muscle atrophy. Similar to IL-6, IL-1α is a key mediator of catabolic processes in cachexia [57]. IL-1α overexpression in tumor cells imparts muscle wasting in tumor-bearing mice, without facilitating anorexia [58]. This is in contrast to the anorexic action of IL-1β that is mediated through its action on the hypothalamus by altering signaling in neuronal populations such as proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and agouti-related protein (AGRP) [59–61]. Macrophages are the principal source of IL-1 family cytokines that are involved in the induction of other inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [62]. Under the hypoxic conditions, an inflammatory signal such as by LPS can induce IL-1α and IL-1β release from macrophages[63]. In PDAC, tumor cells contribute to IL-1α and IL-6 production and, in an autocrine manner, promote tumor cell survival and migration via STAT3 and NF-κb, respectively [64–66]. While IL-1α can control IL-6 expression through NF-κβ, it can induce weight loss in tumor-bearing mice independent of IL-6 [58]. It is interesting to note that we did not see any additive effect of combined IL-6 and IL-1α inhibitions. Perhaps both cytokines trigger a common catabolic process in myotubes. IL-6 and IL-1a increase E3 ubiquitin ligases Atrogin-1 and MuRF1. Although we have not shown that macrophages secrete these factors in tumor-bearing mice, our data suggest that depletion of macrophages attenuates cachectic cytokines in the plasma of pancreatic tumor-bearing mice. This is intriguing given that pancreatic cells and stromal cells can also produce IL-6 in abundance. A previous study has shown that macrophage depletion attenuates TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1α in the skeletal muscle of exercising mice as compared to resting mice [67]. The study argues that exhaustive exercise augments the accumulation of inflammatory macrophages and associated muscle injury. This study lends support to our observation, where we noted attenuated systemic inflammation in the absence of macrophages boosts muscle strength and function. Of note, we observed STAT3 inhibition prevented macrophage CM-induced myotube atrophy. IL-6 and other pro-inflammatory cytokines are known STAT3 inducers[68]. IL-6/STAT3 pathway regulates macrophage polarization to M2 polarization and contributes to metastasis and drug resistance[69, 70]. Taken together, tumor cell-macrophage interactions and the associated inflammatory milieu up-regulate the key cytokines that induce cancer cachexia.

In addition to muscle proteolysis, muscle regeneration and myogenesis are impaired in cancer-associated cachexia [71–74]. Under normal homeostasis, muscle regeneration is strictly governed by muscle microenvironment, where systemic factors play a key role in modulating myogenic precursors. In acute muscle injury, consequent actions of M1 and M2 macrophages aid in the repair of the damaged muscle [75]. While M1 accumulation triggers satellite cell activation, the transition of M1 to M2 induces myogenic differentiation and regeneration in damaged muscle in a time-dependent manner. Hence, any disruption in transition of M1 to M2 phenotype impairs skeletal muscle regeneration [76] Contrastingly, in chronic muscle disorders such as Duchene muscle dystrophy (DMD), M2 macrophages infiltrate early on and inhibit M1 macrophage activity to facilitate pathological fibrosis at later stages of regeneration. [50, 51]. Another study suggests that M2 macrophages can also induce muscle fibrosis through the secretion of IL-4 and IL-13, and the activation of eosinophils [77]. Our studies with human patients suggest increased prevalence of M2 macrophages (CD163+) in the skeletal muscle of pancreatic cancer patients that may impair muscle repair. This observation is supported by a recent report that demonstrates increased skeletal muscle fibrosis in cachectic pancreatic cancer patients as compared to non-cancer control subjects. [78]. More importantly this study also documents increased macrophage (CD68) infiltrations in the cachectic muscles. It is important to note that CD68 is a pan marker for macrophage however, CD163, used in the present study, specifically characterizes M2 macrophages [79]. Furthermore, we observed that macrophage depletion in mice, irrespective of the macrophage subtype, led to increased muscle strength and function in pancreatic tumor-bearing mice. Under such scenario, perhaps other immune players overtake muscle repair processes. Hence, future studies are warranted to understand the role immune cells and inflammatory milieu play in myogenesis in macrophage-depleted tumor-bearing mice. Of note, macrophage and pancreatic tumor-cell-derived can also secrete exosomes to relay signals mediating the cachectic effect. Exosomes participate in intercellular communications by carrying growth factors, enzymes, and miRNAs [80, 81]. Tumor cell-derived exosomes can modulate macrophages polarization and alter the cytotoxic abilities of the latter [82–85]. In addition, macrophage-derived exosomes can regulate tumor cell invasion and migration [80]. However, whether the cachectic agents are directly routed into the circulation or via exosomes is yet to be studied. Overall, we established that M2 macrophage-derived factors could modify skeletal muscle phenotype in pancreatic cancer. Hence, multi-combinatorial therapeutic approaches that also targeted macrophage functions will assist in restoring cancer-associated cachexia in pancreatic cancer.

Highlights:

CD163-positive macrophage infiltration in skeletal muscles negatively correlates with muscle-fiber cross sectional area in PDAC patients.

Macrophage-derived conditioned medium, in combination with tumor cell-conditioned medium, synergistically promotes muscle atrophy through STAT3 signaling.

Macrophage depletion attenuates systemic inflammation and muscle wasting in pancreatic tumor-bearing mice.

Targeting macrophage-mediated STAT3 activation or macrophage-derived IL-1 alpha or IL-6 diminished myofiber atrophy.

Grant Support

This study was funded in part by the support of grants from the National Institutes of Health grant (R01 CA210439, NCI) to PKS, the Specialized Programs for Research Excellence (SPORE, 2P50 CA127297, NCI) to MAH and PKS, NCI Research Specialist award (5R50CA211462) to PMG and the PCDC U01CA210240 to MAH. KM is supported by NCI-SPORE P50 CA127297 Career Development Award.

Abbreviations:

- PDAC

Pancreatic Ductal adenocarcinoma

- CM

Conditioned medium

- KPC

C57BL/6J-congenic KrasG12D; Trp53R172H/+; Pdx-1-Cre BMDMs: Bone marrow-derived macrophages

- 2DG

2-Deoxy-D-glucose

- FDG

2-Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose

- TAMs

Tumor-associated macrophages

- MyHC

myosin heavy chain

- MuRF1

muscle RING finger protein-1 (MuRF1)

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- POMC

Proopiomelanocortin

- AGRP

Agouti-related protein

- DMD

Duchene muscle dystrophy

- M1 macrophages

Classically activated macrophages

- M2 macrophages

Alternatively activated macrophages

- TC-CM

KPC Tumor cell-derived conditioned medium

- Mϕ-CM

M2 macrophage-derived conditioned medium

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of Potential conflict of interest

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2020, CA Cancer J Clin, 70 (2020) 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tan CR, Yaffee PM, Jamil LH, Lo SK, Nissen N, Pandol SJ, Tuli R, Hendifar AE, Pancreatic cancer cachexia: a review of mechanisms and therapeutics, Frontiers in physiology, 5 (2014) 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bachmann J, Ketterer K, Marsch C, Fechtner K, Krakowski-Roosen H, Buchler MW, Friess H, Martignoni ME, Pancreatic cancer related cachexia: influence on metabolism and correlation to weight loss and pulmonary function, BMC cancer, 9 (2009) 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bachmann J, Heiligensetzer M, Krakowski-Roosen H, Buchler MW, Friess H, Martignoni ME, Cachexia worsens prognosis in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer, Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, 12 (2008) 1193–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hendifar A, Osipov A, Khanuja J, Nissen N, Naziri J, Yang W, Li Q, Tuli R, Influence of Body Mass Index and Albumin on Perioperative Morbidity and Clinical Outcomes in Resected Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, PloS one, 11 (2016) e0152172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hendifar AE, Chang JI, Huang BZ, Tuli R, Wu BU, Cachexia, and not obesity, prior to pancreatic cancer diagnosis worsens survival and is negated by chemotherapy, Journal of gastrointestinal oncology, 9 (2018) 17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Moses AG, Maingay J, Sangster K, Fearon KC, Ross JA, Pro-inflammatory cytokine release by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: relationship to acute phase response and survival, Oncology reports, 21 (2009) 1091–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ye H, Zhou Q, Zheng S, Li G, Lin Q, Wei L, Fu Z, Zhang B, Liu Y, Li Z, Chen R, Tumor-associated macrophages promote progression and the Warburg effect via CCL18/NF-kB/VCAM-1 pathway in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Cell death & disease, 9 (2018) 453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Long KB, Collier AI, Beatty GL, Macrophages: Key orchestrators of a tumor microenvironment defined by therapeutic resistance, Molecular immunology, 110 (2019) 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang Y, Velez-Delgado A, Mathew E, Li D, Mendez FM, Flannagan K, Rhim AD, Simeone DM, Beatty GL, Pasca di Magliano M, Myeloid cells are required for PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint activation and the establishment of an immunosuppressive environment in pancreatic cancer, Gut, 66 (2017) 124–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Beatty GL, Winograd R, Evans RA, Long KB, Luque SL, Lee JW, Clendenin C, Gladney WL, Knoblock DM, Guirnalda PD, Vonderheide RH, Exclusion of T Cells From Pancreatic Carcinomas in Mice Is Regulated by Ly6C(low) F4/80(+) Extratumoral Macrophages, Gastroenterology, 149 (2015) 201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Patel HJ, Patel BM, TNF-alpha and cancer cachexia: Molecular insights and clinical implications, Life sciences, 170 (2017) 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Inacio Pinto N, Carnier J, Oyama LM, Otoch JP, Alcantara PS, Tokeshi F, Nascimento CM, Cancer as a Proinflammatory Environment: Metastasis and Cachexia, Mediators of inflammation, 2015 (2015) 791060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Carson JA, Baltgalvis KA, Interleukin 6 as a key regulator of muscle mass during cachexia, Exercise and sport sciences reviews, 38 (2010) 168–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Martignoni ME, Dimitriu C, Bachmann J, Krakowski-Rosen H, Ketterer K, Kinscherf R, Friess H, Liver macrophages contribute to pancreatic cancer-related cachexia, Oncology reports, 21 (2009) 363–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Erdem M, Mockel D, Jumpertz S, John C, Fragoulis A, Rudolph I, Wulfmeier J, Springer J, Horn H, Koch M, Lurje G, Lammers T, Olde Damink S, van der Kroft G, Gremse F, Cramer T, Macrophages protect against loss of adipose tissue during cancer cachexia, Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, Combs C, Deramaudt TB, Hruban RH, Rustgi AK, Chang S, Tuveson DA, Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice, Cancer Cell, 7 (2005) 469–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shukla SK, Dasgupta A, Mehla K, Gunda V, Vernucci E, Souchek J, Goode G, King R, Mishra A, Rai I, Nagarajan S, Chaika NV, Yu F, Singh PK, Silibinin-mediated metabolic reprogramming attenuates pancreatic cancer-induced cachexia and tumor growth, Oncotarget, 6 (2015) 41146–41161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chaika NV, Gebregiworgis T, Lewallen ME, Purohit V, Radhakrishnan P, Liu X, Zhang B, Mehla K, Brown RB, Caffrey T, Yu F, Johnson KR, Powers R, Hollingsworth MA, Singh PK, MUC1 mucin stabilizes and activates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha to regulate metabolism in pancreatic cancer, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109 (2012) 13787–13792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mehla K, Tremayne J, Grunkemeyer JA, O’Connell KA, Steele MM, Caffrey TC, Zhu X, Yu F, Singh PK, Schultes BC, Madiyalakan R, Nicodemus CF, Hollingsworth MA, Combination of mAb-AR20.5, anti-PD-L1 and PolyICLC inhibits tumor progression and prolongs survival of MUC1.Tg mice challenged with pancreatic tumors, Cancer immunology, immunotherapy: CII, 67 (2018) 445–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li Z, Xu X, Feng X, Murphy PM, The Macrophage-depleting Agent Clodronate Promotes Durable Hematopoietic Chimerism and Donor-specific Skin Allograft Tolerance in Mice, Scientific reports, 6 (2016) 22143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tadros S, Shukla SK, King RJ, Gunda V, Vernucci E, Abrego J, Chaika NV, Yu F, Lazenby AJ, Berim L, Grem J, Sasson AR, Singh PK, De Novo Lipid Synthesis Facilitates Gemcitabine Resistance through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Pancreatic Cancer, Cancer research, 77 (2017) 5503–5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Riches JC, Davies JK, McClanahan F, Fatah R, Iqbal S, Agrawal S, Ramsay AG, Gribben JG, T cells from CLL patients exhibit features of T-cell exhaustion but retain capacity for cytokine production, Blood, 121 (2013) 1612–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Koutakis P, Weiss DJ, Miserlis D, Shostrom VK, Papoutsi E, Ha DM, Carpenter LA, McComb RD, Casale GP, Pipinos II, Oxidative damage in the gastrocnemius of patients with peripheral artery disease is myofiber type selective, Redox biology, 2 (2014) 921–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Attri KS, Mehla K, Singh PK, Evaluation of Macrophage Polarization in Pancreatic Cancer Microenvironment Under Hypoxia, Methods in molecular biology, 1742 (2018) 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shukla SK, Dasgupta A, Mulder SE, Singh PK, Molecular and Physiological Evaluation of Pancreatic Cancer-Induced Cachexia, Methods in molecular biology, 1882 (2019) 321–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shukla SK, Gebregiworgis T, Purohit V, Chaika NV, Gunda V, Radhakrishnan P, Mehla K, Pipinos II, Powers R, Yu F, Singh PK, Metabolic reprogramming induced by ketone bodies diminishes pancreatic cancer cachexia, Cancer & metabolism, 2 (2014) 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wang X, Zhao W, Ransohoff RM, Zhou L, Infiltrating macrophages are broadly activated at the early stage to support acute skeletal muscle injury repair, Journal of neuroimmunology, 317 (2018) 55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kharraz Y, Guerra J, Mann CJ, Serrano AL, Munoz-Canoves P, Macrophage plasticity and the role of inflammation in skeletal muscle repair, Mediators of inflammation, 2013 (2013) 491497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Arnold L, Henry A, Poron F, Baba-Amer Y, van Rooijen N, Plonquet A, Gherardi RK, Chazaud B, Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into antiinflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis, The Journal of experimental medicine, 204 (2007) 1057–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cantini M, Giurisato E, Radu C, Tiozzo S, Pampinella F, Senigaglia D, Zaniolo G, Mazzoleni F, Vitiello L, Macrophage-secreted myogenic factors: a promising tool for greatly enhancing the proliferative capacity of myoblasts in vitro and in vivo, Neurological sciences: official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology, 23 (2002) 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cantini M, Massimino ML, Bruson A, Catani C, Dalla Libera L, Carraro U, Macrophages regulate proliferation and differentiation of satellite cells, Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 202 (1994) 1688–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gomes MD, Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Navon A, Goldberg AL, Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98 (2001) 14440–14445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VK, Nunez L, Clarke BA, Poueymirou WT, Panaro FJ, Na E, Dharmarajan K, Pan ZQ, Valenzuela DM, DeChiara TM, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ, Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy, Science, 294 (2001) 1704–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Van Rooijen N, Sanders A, Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications, Journal of immunological methods, 174 (1994) 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Opperman KS, Vandyke K, Clark KC, Coulter EA, Hewett DR, Mrozik KM, Schwarz N, Evdokiou A, Croucher PI, Psaltis PJ, Noll JE, Zannettino AC, Clodronate-Liposome Mediated Macrophage Depletion Abrogates Multiple Myeloma Tumor Establishment In Vivo, Neoplasia, 21 (2019) 777–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pelicano H, Martin DS, Xu RH, Huang P, Glycolysis inhibition for anticancer treatment, Oncogene, 25 (2006) 4633–4646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Cox BL, Mackie TR, Eliceiri KW, The sweet spot: FDG and other 2-carbon glucose analogs for multi-modal metabolic imaging of tumor metabolism, American journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging, 5 (2015) 1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Escames G, Lopez LC, Tapias V, Utrilla P, Reiter RJ, Hitos AB, Leon J, Rodriguez MI, Acuna-Castroviejo D, Melatonin counteracts inducible mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle of septic mice, Journal of pineal research, 40 (2006) 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Muller FL, Song W, Jang YC, Liu Y, Sabia M, Richardson A, Van Remmen H, Denervation-induced skeletal muscle atrophy is associated with increased mitochondrial ROS production, American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology, 293 (2007) R1159–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Brune B, Dehne N, Grossmann N, Jung M, Namgaladze D, Schmid T, von Knethen A, Weigert A, Redox control of inflammation in macrophages, Antioxidants & redox signaling, 19 (2013) 595–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Forman HJ, Torres M, Reactive oxygen species and cell signaling: respiratory burst in macrophage signaling, American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 166 (2002) S4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Schulze-Osthoff K, Bakker AC, Vanhaesebroeck B, Beyaert R, Jacob WA, Fiers W, Cytotoxic activity of tumor necrosis factor is mediated by early damage of mitochondrial functions. Evidence for the involvement of mitochondrial radical generation, The Journal of biological chemistry, 267 (1992) 5317–5323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Langen RC, Schols AM, Kelders MC, Van Der Velden JL, Wouters EF, Janssen-Heininger YM, Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits myogenesis through redox-dependent and -independent pathways, American journal of physiology. Cell physiology, 283 (2002) C714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gelin J, Moldawer LL, Lonnroth C, Sherry B, Chizzonite R, Lundholm K, Role of endogenous tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1 for experimental tumor growth and the development of cancer cachexia, Cancer research, 51 (1991) 415–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Moresi V, Adamo S, Berghella L, The JAK/STAT Pathway in Skeletal Muscle Pathophysiology, Frontiers in physiology, 10 (2019) 500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bonetto A, Aydogdu T, Jin X, Zhang Z, Zhan R, Puzis L, Koniaris LG, Zimmers TA, JAK/STAT3 pathway inhibition blocks skeletal muscle wasting downstream of IL-6 and in experimental cancer cachexia, American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism, 303 (2012) E410–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mehla K, Singh PK, Metabolic Regulation of Macrophage Polarization in Cancer, Trends Cancer, 5 (2019) 822–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Quaranta V, Rainer C, Nielsen SR, Raymant ML, Ahmed MS, Engle DD, Taylor A, Murray T, Campbell F, Palmer DH, Tuveson DA, Mielgo A, Schmid MC, Macrophage-Derived Granulin Drives Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer, Cancer research, 78 (2018) 4253–4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tidball JG, Villalta SA, Regulatory interactions between muscle and the immune system during muscle regeneration, American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology, 298 (2010) R1173–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wehling-Henricks M, Jordan MC, Gotoh T, Grody WW, Roos KP, Tidball JG, Arginine metabolism by macrophages promotes cardiac and muscle fibrosis in mdx muscular dystrophy, PloS one, 5 (2010) e10763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cerami A, Ikeda Y, Le Trang N, Hotez PJ, Beutler B, Weight loss associated with an endotoxin-induced mediator from peritoneal macrophages: the role of cachectin (tumor necrosis factor), Immunology letters, 11 (1985) 173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Haddad F, Zaldivar F, Cooper DM, Adams GR, IL-6-induced skeletal muscle atrophy, Journal of applied physiology, 98 (2005) 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Yakabe M, Ogawa S, Ota H, Iijima K, Eto M, Ouchi Y, Akishita M, Inhibition of interleukin-6 decreases atrogene expression and ameliorates tail suspension-induced skeletal muscle atrophy, PloS one, 13 (2018) e0191318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Duong L, Radley-Crabb HG, Gardner JK, Tomay F, Dye DE, Grounds MD, Pixley FJ, Nelson DJ, Jackaman C, Macrophage Depletion in Elderly Mice Improves Response to Tumor Immunotherapy, Increases Anti-tumor T Cell Activity and Reduces Treatment-Induced Cachexia, Frontiers in genetics, 9 (2018) 526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Erdem M, Mockel D, Jumpertz S, John C, Fragoulis A, Rudolph I, Wulfmeier J, Springer J, Horn H, Koch M, Lurje G, Lammers T, Olde Damink S, van der Kroft G, Gremse F, Cramer T, Macrophages protect against loss of adipose tissue during cancer cachexia, Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle, 10 (2019) 1128–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Li W, Moylan JS, Chambers MA, Smith J, Reid MB, Interleukin-1 stimulates catabolism in C2C12 myotubes, American journal of physiology. Cell physiology, 297 (2009) C706–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kumar S, Kishimoto H, Chua HL, Badve S, Miller KD, Bigsby RM, Nakshatri H, Interleukin-1 alpha promotes tumor growth and cachexia in MCF-7 xenograft model of breast cancer, The American journal of pathology, 163 (2003) 2531–2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Apte RN, Dotan S, Elkabets M, White MR, Reich E, Carmi Y, Song X, Dvozkin T, Krelin Y, Voronov E, The involvement of IL-1 in tumorigenesis, tumor invasiveness, metastasis and tumor-host interactions, Cancer metastasis reviews, 25 (2006) 387–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].McDonald JJ, McMillan DC, Laird BJA, Targeting IL-1alpha in cancer cachexia: a narrative review, Current opinion in supportive and palliative care, 12 (2018) 453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kaushik S, Arias E, Kwon H, Lopez NM, Athonvarangkul D, Sahu S, Schwartz GJ, Pessin JE, Singh R, Loss of autophagy in hypothalamic POMC neurons impairs lipolysis, EMBO reports, 13 (2012) 258–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Dinarello CA, Overview of the IL-1 family in innate inflammation and acquired immunity, Immunological reviews, 281 (2018) 8–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Carmi Y, Voronov E, Dotan S, Lahat N, Rahat MA, Fogel M, Huszar M, White MR, Dinarello CA, Apte RN, The role of macrophage-derived IL-1 in induction and maintenance of angiogenesis, Journal of immunology, 183 (2009) 4705–4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Tjomsland V, Bojmar L, Sandstrom P, Bratthall C, Messmer D, Spangeus A, Larsson M, IL-1alpha expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma affects the tumor cell migration and is regulated by the p38MAPK signaling pathway, PloS one, 8 (2013) e70874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Voronov E, Dotan S, Krelin Y, Song X, Elkabets M, Carmi Y, Rider P, Idan C, Romzova M, Kaplanov I, Apte RN, Unique Versus Redundant Functions of IL-1alpha and IL-1beta in the Tumor Microenvironment, Frontiers in immunology, 4 (2013) 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ling J, Kang Y, Zhao R, Xia Q, Lee DF, Chang Z, Li J, Peng B, Fleming JB, Wang H, Liu J, Lemischka IR, Hung MC, Chiao PJ, KrasG12D-induced IKK2/beta/NF-kappaB activation by IL-1alpha and p62 feedforward loops is required for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Cancer cell, 21 (2012) 105–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kawanishi N, Mizokami T, Niihara H, Yada K, Suzuki K, Macrophage depletion by clodronate liposome attenuates muscle injury and inflammation following exhaustive exercise, Biochemistry and biophysics reports, 5 (2016) 146–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Niemand C, Nimmesgern A, Haan S, Fischer P, Schaper F, Rossaint R, Heinrich PC, Muller-Newen G, Activation of STAT3 by IL-6 and IL-10 in primary human macrophages is differentially modulated by suppressor of cytokine signaling 3, Journal of immunology, 170 (2003) 3263–3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Ara T, Nakata R, Sheard MA, Shimada H, Buettner R, Groshen SG, Ji L, Yu H, Jove R, Seeger RC, DeClerck YA, Critical role of STAT3 in IL-6-mediated drug resistance in human neuroblastoma, Cancer research, 73 (2013) 3852–3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Johnson DE, O’Keefe RA, Grandis JR, Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer, Nature reviews. Clinical oncology, 15 (2018) 234–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Arneson PC, Doles JD, Impaired Muscle Regeneration in Cancer-Associated Cachexia, Trends in cancer, 5 (2019) 579–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Fearon KC, Glass DJ, Guttridge DC, Cancer cachexia: mediators, signaling, and metabolic pathways, Cell metabolism, 16 (2012) 153–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Talbert EE, Guttridge DC, Impaired regeneration: A role for the muscle microenvironment in cancer cachexia, Seminars in cell & developmental biology, 54 (2016) 82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].He WA, Berardi E, Cardillo VM, Acharyya S, Aulino P, Thomas-Ahner J, Wang J, Bloomston M, Muscarella P, Nau P, Shah N, Butchbach ME, Ladner K, Adamo S, Rudnicki MA, Keller C, Coletti D, Montanaro F, Guttridge DC, NF-kappaB-mediated Pax7 dysregulation in the muscle microenvironment promotes cancer cachexia, The Journal of clinical investigation, 123 (2013) 4821–4835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Villalta SA, Nguyen HX, Deng B, Gotoh T, Tidball JG, Shifts in macrophage phenotypes and macrophage competition for arginine metabolism affect the severity of muscle pathology in muscular dystrophy, Human molecular genetics, 18 (2009) 482–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Wang H, Melton DW, Porter L, Sarwar ZU, McManus LM, Shireman PK, Altered macrophage phenotype transition impairs skeletal muscle regeneration, The American journal of pathology, 184 (2014) 1167–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wehling-Henricks M, Sokolow S, Lee JJ, Myung KH, Villalta SA, Tidball JG, Major basic protein-1 promotes fibrosis of dystrophic muscle and attenuates the cellular immune response in muscular dystrophy, Human molecular genetics, 17 (2008) 2280–2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Judge SM, Nosacka RL, Delitto D, Gerber MH, Cameron ME, Trevino JG, Judge AR, Skeletal Muscle Fibrosis in Pancreatic Cancer Patients with Respect to Survival, JNCI cancer spectrum, 2 (2018) pky043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Minami K, Hiwatashi K, Ueno S, Sakoda M, Iino S, Okumura H, Hashiguchi M, Kawasaki Y, Kurahara H, Mataki Y, Maemura K, Shinchi H, Natsugoe S, Prognostic significance of CD68, CD163 and Folate receptor-beta positive macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma, Experimental and therapeutic medicine, 15 (2018) 4465–4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Lan J, Sun L, Xu F, Liu L, Hu F, Song D, Hou Z, Wu W, Luo X, Wang J, Yuan X, Hu J, Wang G, M2 Macrophage-Derived Exosomes Promote Cell Migration and Invasion in Colon Cancer, Cancer research, 79 (2019) 146–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Esser J, Gehrmann U, D’Alexandri FL, Hidalgo-Estevez AM, Wheelock CE, Scheynius A, Gabrielsson S, Radmark O, Exosomes from human macrophages and dendritic cells contain enzymes for leukotriene biosynthesis and promote granulocyte migration, The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 126 (2010) 1032–1040, 1040 e1031–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Baig MS, Roy A, Rajpoot S, Liu D, Savai R, Banerjee S, Kawada M, Faisal SM, Saluja R, Saqib U, Ohishi T, Wary KK, Tumor-derived exosomes in the regulation of macrophage polarization, Inflammation research: official journal of the European Histamine Research Society … [et al. ], 69 (2020) 435–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Panigrahi GK, Praharaj PP, Kittaka H, Mridha AR, Black OM, Singh R, Mercer R, van Bokhoven A, Torkko KC, Agarwal C, Agarwal R, Abd Elmageed ZY, Yadav H, Mishra SK, Deep G, Exosome proteomic analyses identify inflammatory phenotype and novel biomarkers in African American prostate cancer patients, Cancer medicine, 8 (2019) 1110–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Li X, Lei Y, Wu M, Li N, Regulation of Macrophage Activation and Polarization by HCC-Derived Exosomal lncRNA TUC339, International journal of molecular sciences, 19 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Ying X, Wu Q, Wu X, Zhu Q, Wang X, Jiang L, Chen X, Wang X, Epithelial ovarian cancer-secreted exosomal miR-222–3p induces polarization of tumor-associated macrophages, Oncotarget, 7 (2016) 43076–43087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]