Abstract

This special issue of Social Service Review presents original research on the determinants and consequences of economic instability, with a focus on the interplay between instability and social policy. To frame that discussion, we define economic instability as repeated changes in employment, income, or financial well-being over time, particularly changes that are not intentional, predictable, or part of upward mobility. We also present a conceptual framework for how instability occurs in multiple domains of family life and how social policy has the potential to both buffer and exacerbate instability in employment and family structure. The articles in the volume engage many of these domains, including employment and program instability, and multiple areas of social policy, including workplace regulations and child-care subsidies. They also point to paths for future research, which we summarize in the final section of this introduction.

INTRODUCTION

Across many areas of life, instability marks the day-to-day reality of low-income Americans. Unpredictable employment and work schedules (Hollister 2011; Hollister and Smith 2014; Lambert, Fugiel, and Henly 2014), fluctuating public benefits (Lambert and Henly 2013; Mills et al. 2014; Ben-Ishai 2015), changes in romantic relationships and household composition (Cherlin 2010), and unwanted housing and neighborhood churning (Desmond, Gershenson, and Kiviat 2015; Desmond and Shollenberger 2015; Desmond 2016) all too commonly mark the lives of poor Americans. Taken together, these sources of economic instability create much greater income variability for low-income families than for their high-income counterparts, and this gap in income variability has grown larger in recent years (Morris et al. 2015). Both the causes of income variability and the fluctuations in resources have been shown to affect material hardship and adult and child outcomes (e.g., Leete and Bania 2010; Sandstrom and Huerta 2013; Hardy 2014; Gennetian et al. 2015).

Income variability can also reflect upward mobility or planned decisions to balance work and family responsibilities. The emblematic “American Dream” of social and economic mobility requires repeated upward movements in educational attainment, income, or occupational status. Even down-ward changes in economic circumstances can reflect intentional decisions and preferences to invest in human capital, pursue a better job match, raise children, or trade earnings for time at home. The combination of positive and negative dimensions of variability poses challenges for researchers attempting to understand the causes and consequences of economic fluctuations and for policy makers and administrators designing and implementing public programs to promote family well-being.

This special issue of Social Service Review presents new research on economic instability among low-income families and on how instability relates to policy design, implementation, and outcomes. To frame those empirical contributions, we first define economic instability in the context of prior research and introduce a broad conceptual model for the domains of economic instability, including income support programs. Next, we introduce each of the articles in this volume and summarize how they contribute to our understanding of these topics. Finally, we suggest several areas for future research on economic instability and social policy inspired by the articles in this issue.

DEFINING ECONOMIC INSTABILITY

Research on poverty and social policy has traditionally considered economic disadvantage to be a static state. Similarly, both the rhetoric and design of current US income support policies focus on either helping the persistently low resourced (e.g., food stamps) or promoting work as a path to upward mobility and self-sufficiency (e.g., childcare subsidies). Public discussions about social policy often focus on the intergenerational cycle of poverty and the so-called poverty trap because, for many families, low incomes persist for years, lifetimes, and generations. In fact, the income eligibility thresholds and benefit calculators used by income support programs rest on a binary notion of families being either stably poor or upwardly mobile with consistently sufficient income. For instance, an increase in income that pushes a family above the eligibility limits is taken as proof that the family has achieved self-sufficiency.

While chronic poverty is a real and documented pattern for many low-income families, recent research highlights the increased prevalence of unstable employment and income among low-income families (e.g., Kalleberg 2010; Moffitt and Gottschalk 2012; Hardy and Ziliak 2014; Western et al. 2016). The term “earnings instability” was first used in Gottschalk and Moffitt’s (Gottschalk and Moffitt 1994, 2009; Moffitt and Gottschalk 2012) decompositions of earnings variance into permanent and transitory components, the former being predicted by worker characteristics, such as age and education, and the latter being the residual, unexplained variance, which they also call earnings instability. Others have gone on to study earnings and income fluctuations using different measures, such as the number or frequency of large income changes (Gosselin and Zimmerman 2008; Dahl, DeLeire, and Schwabish 2011; Hacker et al. 2014; Western et al. 2016), the coefficient of variation (Newman 2008; Leete and Bania 2010; Gennetian et al. 2015), and arc percentage change (Dynan, Elmendorf, and Sichel 2012; Hardy and Ziliak 2014; Wolf et al. 2014; Gennetian et al. 2015).

The takeaway from this large literature is that earnings and income variability have increased substantially for all individuals and households since the 1970s but particularly for workers with less education and families with less income (Gottschalk and Moffitt 2009; Dynan et al. 2012; Morduch and Schneider 2017). For example, Morduch and Schneider (2017) use the data from the US Financial Diaries (USFD) project, which tracked a year’s worth of financial transactions for 235 low-income and moderate-income households. They find poor families experience more and larger monthly income dips than do families with higher incomes. In addition, the majority of families in the USFD (70 percent) spent at least 1 month of the year in poverty.

Social science researchers studying multiple domains of family life also use the term “instability,” but they imbue the term with an explicit focus on repeated, involuntary, or unpredictable changes (Cavanagh and Huston 2006, 2008; Hill et al. 2013; Sandstrom and Huerta 2013; Gennetian et al. 2015). Similarly, Hacker and colleagues (Hacker 2008; Hacker and Jacobs 2008; Hacker et al. 2014) and Western and colleagues (2012, 2016) use the term “economic insecurity” to describe variability that is a manifestation of the increased risk from unpredictable events experienced by families or households in the modern economy. Finally, although it is not discussed as such in the literature, mobility is also a form of variability, but one that is assumed to be desirable and beneficial. Mobility can be the positive result of risk taking when opportunities are presented. For instance, leaving a steady job to pursue additional education involves some risk and could certainly result in economic instability, but it might be a path toward upward mobility and stability at a higher income than before.

For this volume, we define economic instability as repeated changes in employment, income, or financial well-being over time, particularly changes that are not intentional, predictable, or part of upward mobility. Instability captures the experience of a pattern of multiple changes, which are not, as a whole, leading to better circumstances but instead may contribute to the disruption of family routines, stress, and hardship. This is similar to prior definitions of instability, particularly Sandstrom and Huerta’s (2013) definition of instability as an “abrupt, involuntary, and/or negative change in individual or family circumstances, which is likely to have adverse implications for child development” (10).Unlike prior definitions, however, ours emphasizes that instability is a pattern, rather than a single event, and that adverse consequences are most likely when families lose control of, or a sense of progress about, their economic circumstances.

DOMAINS OF ECONOMIC INSTABILITY

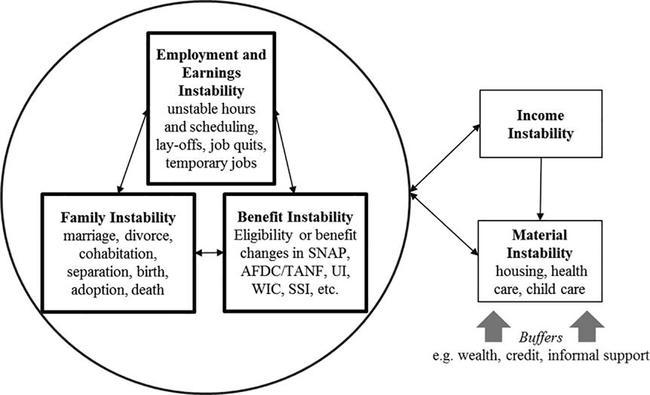

Figure 1 displays a conceptual framework for understanding economic instability in low-income family life. At the center of this framework, there is a triad of domains (shown inside the circle) that drive economic instability—employment and earnings, family composition, and benefit receipt.

FIGURE 1.

Economic instability conceptual framework

EMPLOYMENT AND EARNINGS INSTABILITY

Workers in low-income families face greater between- and within-job instability as a function of both economic cycles and enduring structural changes to the economy (Fligstein and Shin 2004; Kalleberg 2009, 2010; Farber 2010). Between-job instability refers to repeated movements in and out of employment statuses or between jobs through quitting jobs, layoffs, and firings. Although job tenure for American workers has been flat or slightly increasing since the 1990s (Hipple and Sok 2013), the average trend obscures substantial declines for most workers. All men and never-married women have seen declines in long-term employment tenure and increases in short-term job instability in recent decades (Farber 2010; Hollister 2011; Hollister and Smith 2014). Increases in between-job instability have been particularly large for less educated, nonwhite, and private sector workers (Jaeger and Stevens 1999). Only married women have actually experienced an improvement in job tenure, a change that is attributable to more continuous employment around childbirth (Hollister 2011; Hollister and Smith 2014).

Within-job instability relates to changes in the number or timing of hours worked, such as nonstandard work arrangements, unpredictable work scheduling, last-minute changes to posted work schedules, and week-to-week variation in days or shifts worked (Kalleberg 2000; Kalleberg, Reskin, and Hudson 2000; Henly and Lambert 2014; Lambert et al. 2014; Board of Governors 2016). Research on within-job instability demonstrates that low-income workers face more irregular work schedules, relative to their higher-income peers (Lambert et al. 2014; Golden 2015). In a nationally representative sample, 69 percent of mothers and 80 percent of fathers working in low-wage jobs experienced fluctuations in working hours by approximately 40 percent over a month (Lambert et al. 2014). According to another national data set, within-job instability is the number one cause of month-to-month income variability (Board of Governors 2016; Morduch and Schneider 2017).

FAMILY INSTABILITY

Changes to family structure or composition can also cause economic instability. Changes in the number of working adults in the home have direct consequences for family income. In addition, the number of children or elders in the home, and the marital status of the primary earners, can affect the family’s expenses and the pooling of resources. Only in the past decade have researchers in family studies moved from studying the point-in-time statuses of family structure or composition to examining the prevalence and consequences of transitions in family life (e.g., Ackerman et al. 1999, 2002; Cavanagh and Huston 2006, 2008).

Instability in family composition is particularly relevant for low-income individuals relative to their higher-income peers because low-income individuals have higher rates of cohabitation, divorce, and union dissolution (Manning, Smock, and Majumdar 2004). The higher rate of cohabitation among lower-income families increases instability, as many cohabiting unions are short-lived and have a higher risk of dissolution (Teachman and Polonko 1990; Bramlett and Mosher 2002). Finally, the implications of changes to family composition may be far greater for low-income families who are unlikely to have savings or to be able to recover child support from a noncustodial parent.

BENEFIT INSTABILITY

Means-tested income support programs are a key source of income and in-kind benefits for many low-income families. These programs include the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and cash assistance programs for the poor, disabled, elderly, and unemployed, as well as subsidy programs such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP; formerly called food stamps), Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), public housing and housing vouchers, and child-care subsidies.

If income support programs become more generous when incomes fall and less generous when incomes rise, they should decrease economic instability. Indeed, evidence suggests that the combined set of income support programs reduces year-on-year income instability, particularly for the lowest income families (Bitler, Hoynes, and Kuka 2017; Hardy 2017), but that the stabilizing effects of income support programs have decreased over time (Hardy 2017). One potential explanation for this change is that both federal welfare reform and multiple expansions of the EITC have tied eligibility and benefit levels more tightly to unstable employment and earnings. Families receiving income supports have to report employment, earnings, or income at the time of application, during the period of receipt, and at specified recertification points. When earnings or other sources of family income fluctuate, these program rules may lead to income supports fluctuating too. In other words, income supports may amplify rather than compensate for employment or family structure instability (Hill and Ybarra 2014; Romich and Hill 2017).

Ideally, families exit income support programs after a permanent or sustained increase in income. Yet, the reality of low-income family life is that changes in employment and family structure are rarely permanent. Program rules could make a family seem eligible in some periods but not in others, when the family’s needs have not fundamentally changed and average income across months may put them at consistent eligibility. This seems particularly likely with seasonal employment, large fluctuations in work hours, or varying income from multiple jobs or self-employment income. A study of SNAP churning—leaving the program and returning within 4 months—provides evidence of this problem. Most churning is related to changes in residence, employment, and household composition, and many of those changes are short-lived (Mills et al. 2014). Research also suggests that programs with more frequent and complex recertification processes, such as Medicaid/CHIP and child-care subsidies, have more disenrollment and churning (e.g., Herndon et al. 2008; Pilarz, Claessens, and Gelatt 2016). Also, among families eligible for SNAP, those that experience greater earnings variability have lower program participation than those with permanently low levels of household income (Moffitt and Ribar 2008).

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN DOMAINS

Instability in all three domains comes together to produce income instability and what we call “material instability,” or repeated and unpredictable changes in basic needs and services, such as housing, child care, and health care. The provision of basic needs and services can be destabilized by both income instability and the loss of public benefits. Growing evidence from both qualitative studies and surveys documents the high frequency of change in low-income family life and the linkage between change in employment and change in child care (Scott, London, and Hurst 2005; Ben-Ishai, Matthews, and Levin-Epstein 2014; Scott and Abelson 2016) and change in employment and change in housing (Desmond and Gershenson 2016).

As Sandstrom and Huerta (2013) point out, instability in one domain can lead to instability in another, and instability across domains can have additive or interactive effects. For example, a tenuous romantic relationship could be one fight away from a breakup and a housing transition, which could interfere with work, necessitate school changes for children, and stretch limited resources to pay for new housing searches and security deposits. Unpredictable work hours could also lead to a reliance on informal or unstable child-care arrangements, which could contribute to a family’s ability to use child-care subsidies, to changes in the cost of child care, and to material hardships in other areas. Low-income families are more likely to experience all of these different types of economic instability and are less likely to have savings, access to credit, or informal support networks, the potential buffers that could help smooth consumption and protect well-being.

ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE

The articles in this special issue extend our knowledge of the relationship between economic instability, the safety net, and the well-being of low-income families. The first article, “In and Out of Poverty: Episodic Poverty and Income Volatility in the US Financial Diaries” by Jonathan Morduch and Julie Siwicki, draws on a unique data set, the USFD, to document the experience of income instability. The authors use this unusually detailed income data to map out changes in family income including month-to-month entries into and exits from poverty. Although their sample consists of families with an average income of nearly 200 percent of the poverty line, over half of all households were below the poverty line for at least 1 month during the time of their study. They calculate volatility with and without government transfers and find that transfers reduce income volatility through increasing average income rather than through offsetting month-to-month fluctuations.

The next two articles in this issue examine how families cope with high levels of instability. In “Instability of Work and Care: How Work Schedules Shape Child-Care Arrangements for Parents Working in the Service Sector,” Dani Carrillo and colleagues use qualitative data collected from workers in the service industry to examine how families manage the responsibilities of work and child care. They present evidence that unstable and unpredictable schedules pose a greater challenge to family life than do nonstandard hours and that using informal support networks for child care is a key coping strategy.

In their article “Use of Informal Safety Nets during the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Benefit Cycle: How Poor Families Cope with Within-Month Economic Instability,” Anika Schenck-Fontaine, Anna Gassman-Pines, and Zoelene Hill use survey data from low-income families in Durham, North Carolina, to examine how families cope with another external source of instability: the SNAP benefit cycle. Because SNAP benefits are distributed once a month and are designed to provide only a partial subsidy of food costs, most families receiving SNAP experience a dip in income in the final week of each month. This variability is predictable, but it can still be substantial for families without sufficient income or savings to buffer that dip. Similar to Carrillo and colleagues, Schenck-Fontaine and colleagues find that families rely on informal support networks to buffer against instability, which still leaves families with insufficient income.

The article “What Explains Short Spells on Child Care Subsidies?” by Julia Henly and colleagues directly addresses the factors that may contribute to instability in income support program participation by analyzing one income support program: child-care subsidies. The authors link administrative records and survey data from Illinois and New York to explore child-care subsidy receipt. They find that recipients more often lost subsidies during the 18-month observation period in Illinois than in New York, concurrent with differences in administrative program rules across the states. Challenges with enrollment in subsidies are also associated with shorter receipt duration, perhaps reflecting too high an administrative burden for participation. Finally, aspects of low-wage work, including insufficient and nonstandard hours, make child-care subsidy receipt particularly challenging for some families.

Sharon Wolf and Taryn Morrissey use nationally representative data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation to estimate relationships between family economic instability, food insecurity, and child health. Their article, “Economic Instability, Food Insecurity, and Child Health in the Wake of the Great Recession,” finds that both the incidence and the accumulation of instability predict poorer child outcomes, particularly for children with less educated parents. These findings are consistent with a few prior studies that identify adverse effects of income instability on children (Gennetian et al. 2015; Wagmiller 2015; Hardy 2017), but this is the first study to find that relationship for health outcomes.

DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The articles in this special issue add to a growing literature on the prevalence of economic instability among low-income families, the interactions between that instability and income support programs, and the potentially detrimental consequences of economic instability for adult and child outcomes. They also offer clear signposts for future paths of research in this field. Below, we briefly describe five key directions for future research.

COLLECTING MORE AND BETTER LONGITUDINAL DATA OVER LONGER TIME HORIZONS

Any measure of instability requires consistent measurement across time, often at regular intervals. Furthermore, what looks like instability in a short time horizon (e.g., 2 or 3 years) may be investments in later stability. For example, a woman leaving an abusive relationship may face economic insecurity in the near term followed by improved economic and relationship stability in the long term. Job changes early in adulthood are another example, as they may be associated with temporary fluctuations in wages followed by increased earnings over time. Distinguishing the “primary trend,” as they say in investment theory, from short-term volatility requires long time horizons and multiple data points. There is no standard in the study of family income for how long that time horizon should be or how many data points are necessary.

The USFD data (see Morduch and Siwicki in this issue) set a high bar for the comprehensiveness and detail of the financial information collected from families. The limitations of that study come from its relatively small and nonrepresentative sample. This field of research would benefit greatly from the fielding of one or more longitudinal surveys of a probability sample to collect information on daily or weekly economic circumstances, as well as rich demographic information and valid process and outcome measures. This effort could be embedded as a module in an existing survey, such as the Panel Study of Income Dynamics or the Survey of Income and Program Participation, or it could be a standalone effort. Either way, the quality of the data would depend on using mixed modes of data collection (e.g., online and in person), as well as the collection of supporting paperwork (e.g., bills and pay stubs). Most important, the study would need to collect data regularly for an extended period to be able to distinguish variability in economic circumstances from level and trend characteristics. Linkages to administrative data sources could enhance longitudinal studies and allow for better measures of patterns of employment and program participation.

GRAPPLING WITH THE RELATED BUT DISTINCT CONCEPTS OF INSUFFICIENCY, INSTABILITY, AND MOBILITY AS CONSTRUCTS, MEASURES, AND PROGRAM GOALS

Future research should work to delineate the conceptual and methodological differences of instability and to have an open discussion of how these differences play out in the lives of low-income workers. The USFD study shows that families place a higher value on achieving financial stability than they do on moving up the income ladder (Morduch and Schneider 2017). Findings from Wolf and Morrissey’s article in this issue show that both positive instability (gaining employment) and negative instability (losing employment) predict food insecurity. If instability is simply a component of earnings inequality, as conceptualized in the studies of Gottschalk and Moffitt (e.g., 1994, 2009), then public programs should consider simply increasing the amount of money provided to workers. If however, instability is a force all on its own, current program goals may be out of date and may need to be revised to explicitly address financial instability.

In their article in this issue, Schenck-Fontaine and colleagues move us in this direction. The authors describe the SNAP benefit as producing instability as a result of insufficiency. In other words, SNAP benefits are distributed one time per month but are insufficient to last the entire month. As a consequence, income levels dip in the last week of every month. This predictable variability may not be detrimental if families are able to plan for and buffer against the change. Many low-income families do not have extra resources to smooth consumption, however, which leads to the concern that even this predictable change may lead to food insufficiency and hunger. Should we think about SNAP benefits as insufficient, unstable, or both? And, would the problem of running out of SNAP benefits best be solved by increasing the benefit levels or by distributing the benefits two or more times per month? Scholars of SNAP and the safety net in general should pursue these empirical and political questions.

EXAMINING THE AVAILABILITY AND COSTS OF THE STRATEGIES FAMILIES USE TO COPE WITH INSTABILITY, INCLUDING SAVINGS, CREDIT, AND INFORMAL SUPPORT

Two of the articles in this issue, one by Carrillo and colleagues and one by Schenck-Fontaine and colleagues, provide evidence suggesting that low-income families are relying on family and friends to buffer against both employment and income instability. While some studies point to the benefits of informal support networks for economic well-being and health (Henly, Danziger, and Offer 2005; Leininger, Ryan, and Kalil 2009; Ryan, Kalil, and Leininger 2009), others suggest that informal support networks are limited and often burdensome for low-income families. The most disadvantaged families are often the ones without access to informal support (Harknett and Hartnett 2011). In addition, the capacity to respond to a kin member’s need depends in part on one’s own financial resources, which follow racialized distributions of income and wealth. For instance, poor whites are more likely than poor African Americans to have middle-class relatives (Heflin and Patillo 2006), and whites hold much greater wealth on average than blacks or Latinos, even after holding education constant (Hamilton and Darity 2017). In addition, relying on informal support networks may be stressful, cause conflict, or be detrimental to the financial well-being of family and friends (O’Brien 2012; Offer 2012). Finally, research suggests that informal support networks are mechanisms for survival but not for mobility (Henly et al. 2005).

More research is needed to understand the ways in which families are able to cope with instability and the extent to which those strategies represent choice and preferences versus a lack of options. A recent example of this is survey work by the Federal Reserve System, which asks participants whether they would be able to handle a small financial disruption of $400. Forty-six percent of respondents indicated they could not pay $400 and would instead use a variety of informal and formal strategies, including using a credit card they would pay off over time (38 percent), using a bank loan or line of credit (7 percent), using payday loan or bank overdraft (4 percent), borrowing from friends or family (28 percent), or selling something (17 percent; Board of Governors 2016).

INTEGRATING MEASURES OF (IN)STABILITY INTO ALL STUDIES OF THE EFFECTS OF INCOME SUPPORT PROGRAMS AND RELATED POLICIES

Income support programs sometimes stabilize family economic circumstances, but their rules and administration can also exacerbate instability caused by employment or family structure. The goals of income support programs in the United States have traditionally been to provide for basic needs, encourage employment, and minimize the cost to taxpayers. It is possible that these programs could be reoriented to promote stability that leads to mobility, but we do not yet know what changes would be required to accomplish that goal and whether the goal could be reconciled with minimizing program costs. For this reason, it is imperative that studies of income support programs examine their effects on dynamic measures of economic and other family circumstances, for instance, by measuring income level and variability, employment status at a point in time and employment patterns over time, and gaps in health insurance or child-care subsidies as well as point-in-time coverage or usage. Importantly, many of our income support programs seek to promote economic mobility, but rarely do program performance measures or evaluation outcomes capture long-term trends in economic well-being for recipients.

USING ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIMENTS TO TEST PROGRAMMATIC CHANGES DESIGNED TO PROMOTE STABILITY

Arguably, more stable income support may serve as a precursor to mobility, allowing families to catch their breath and prepare for stretching further upward toward mobility. By forgiving temporary bumps in income, or by expanding the period considered for income reporting, programs may allow families more stability. If that stability leads to better outcomes, the costs and benefits of the approach may be more positive for the participants and the public.

These are questions that could be answered by administrative experiments, which are relatively low in cost and provide high-quality evidence of the effects of a change in program operations. Experiments of innovative program rules or practices could help policy makers and program administrators weigh the benefits of stability against the risks of overcoverage, or the use of benefits and services by families who are outside of the target population. In their article in this issue, Henly and colleagues suggest that jobs shift at times when people lose child-care subsidies. Allowing families to earn a bit more while still receiving level child-care benefits may allow them to save sufficient funds to pay the expected deposits. Permitting families to maintain child care through periods of unemployment may buffer the influence of job loss and make it easier to accept a new job, knowing a child has continuous care.

Similarly, 22 states opt to provide transitional SNAP benefits for 5 months after a family leaves the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (without reapplication or additional paperwork). In theory, this widely implemented policy could promote stability and mobility and could be a model for other programs, but we know of no evaluation documenting the effects of the policy. For instance, when individual or family earnings or income move above program eligibility limits, are these changes lasting or temporary? Studies of these and other policy approaches can help identify the costs and benefits of an increased focus on stability to recipients and to society broadly.

Even if program changes fail to influence economic stability, data from administrative experiments could be used to examine the range of effects of instability on child and adult outcomes. As Wolf and Morrissey show in their article in this issue, instability can have adverse consequences for child outcomes and development. A broader understanding of the effects of instability would be an important component of cost-benefit analysis and could build political support for programmatic improvements to improve stability.

Acknowledgments

Hill, Romich, and Mattingly receive research grant funding from the Family Self-Sufficiency and Stability Research Consortium of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation in the Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services. The authors would like to thank Emily Schmitt, Michael Fishman, Matthew Stagner, and Jonathan McCay for their comments on early drafts of this manuscript. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Biography

Heather D. Hill is an associate professor in the Daniel J. Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington. Her research examines social policy, economic disadvantage, and child well-being.

Jennifer Romich is an associate professor of social welfare and director of the West Coast Poverty Center at the University of Washington. Her research examines low-income workers’ family economic well-being and interactions with public policy.

Marybeth J. Mattingly is director of research on vulnerable families at the Carsey School of Public Policy and a research assistant professor of sociology at the University of New Hampshire. She also serves as a research consultant with the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality. Her research focuses on innovative ways of understanding poverty and safety net programs, as well as the realities of low-wage work.

Shomon Shamsuddin is an assistant professor of social policy at Tufts University. His research explores how formal and informal policies affect urban poverty and inequality.

Hilary Wething is a doctoral candidate of public policy and management at the Daniel J. Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington. Her research explores how public policy affects the economic security and instability of low-income households.

Contributor Information

HEATHER D. HILL, University of Washington

JENNIFER ROMICH, University of Washington.

MARYBETH J. MATTINGLY, University of New Hampshire

SHOMON SHAMSUDDIN, Tufts University.

HILARY WETHING, University of Washington.

REFERENCES

- Ackerman Brian P., Brown Eleanor D., Kristen Schoff D’Eramo, and Izard Carroll E.. 2002. “Maternal Relationship Instability and the School Behavior of Children from Disadvantaged Families.” Developmental Psychology 38 (5): 694–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman Brian P., Kogos Jen, Youngstrom Eric, Schoff Kristen, and Izard Carroll. 1999. “Family Instability and the Problem Behaviors of Children from Economically Disadvantaged Families.” Developmental Psychology 35 (1): 258–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ishai Liz. 2015. “Volatile Job Schedules and Access to Public Benefits.” CLASP, Washington, DC: http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/volatile-job-schedules-and-access-to-public-benefits. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ishai L, Matthews H, and Levin-Epstein J. 2014. Scrambling for Stability: The Challenges of Job Schedule Volatility and Child Care. Washington, DC: CLASP. [Google Scholar]

- Bitler Marianne, Hoynes Hilary, and Kuka Elira. 2017. “Child Poverty, the Great Recession, and the Social Safety Net in the United States.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 36 (2): 358–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Board of Governors. 2016. “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2015.” Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett Matthew, and Mosher William. 2002. “Cohabitation, Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage in the United States.” US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Health Statistics, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh Shannon E., and Huston Aletha C.. 2006. “Family Instability and Children’s Early Problem Behavior.” Social Forces 85 (1): 551–81. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2008. “The Timing of Family Instability and Children’s Social Development.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 70 (5): 1258–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew J. 2010. “Demographic Trends in the United States: A Review of Research in the 2000s.” Journal of Marriage and Family 72 (3): 403–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl Molly, Thomas DeLeire, and Schwabish Jonathan A.. 2011. “Estimates of Year-to-Year Volatility in Earnings and in Household Incomes from Administrative, Survey, and Matched Data.” Journal of Human Resources 46 (4): 750–74. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond Matthew. 2016. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. New York: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond Matthew, and Gershenson Carl. 2016. “Housing and Employment Insecurity among the Working Poor.” Social Problems 63:46–67. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond Matthew, Gershenson Carl, and Kiviat Barbara. 2015. “Forced Relocation and Residential Instability among Urban Renters.” Social Service Review 89 (2): 227–62. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond Matthew, and Shollenberger Tracey. 2015. “Forced Displacement from Rental Housing: Prevalence and Neighborhood Consequences.” Demography 52 (5): 1751–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynan Karen, Elmendorf Douglas W., and Sichel Daniel E.. 2012. “The Evolution of Household Income Volatility.” BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 12 (2): 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Farber Henry S. 2010. “Job Loss and the Decline in Job Security in the United States” 223–66 in Labor in the New Economy, edited by Abraham Katherine G., Spletzer James R., and Michael Harper. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fligstein Neil, and Shin Taekjin. 2004. “The Shareholder Value Society: A Review of the Changes in Working Conditions and Inequality in the United States, 1976–2000” 401–32 in Social Inequality, edited by Neckerman Kathryn M.. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gennetian Lisa A., Wolf Sharon, Hill Heather D., and Morris Pamela A.. 2015. “Intra-year Household Income Dynamics and Adolescent School Behavior.” Demography 52 (2): 455–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden Lonnie. 2015. “Irregular Work Scheduling and Its Consequences.” Briefing Paper no. 394. Economic Policy Institute, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin Peter, and Zimmerman Seth. 2008. “Trends in Income Volatility and Risk, 1970–2004.” Working paper. Urban Institute, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk Peter, and Moffitt Robert A.. 1994. “The Growth of Earnings Instability in the United States Labor Market.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2:217–72. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2009. “The Rising Instability of US Earnings.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 23 (4): 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker Jacob S. 2008. The Great Risk Shift: The New Economic Insecurity and the Decline of the American Dream. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker Jacob S., Huber Gregory A., Nichols Austin, Rehm Philipp, Schlesinger Mark, Valletta Rob, and Craig Stuart. 2014. “The Economic Security Index: A New Measure for Research and Policy Analysis.” Review of Income and Wealth 60 (S1): S5–S32. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker Jacob S., and Jacobs Elisabeth. 2008. “The Rising Instability of American Family Incomes, 1969–2004: Evidence from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics.” Briefing paper. Economic Policy Institute, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Darrick, and Darity William A. Jr. 2017. “The Political Economy of Education, Financial Literacy, and the Racial Wealth Gap.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 99 (1): 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy Bradley. 2014. “Childhood Income Volatility and Adult Outcomes.” Demography 51 (5): 1641–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2017. “Income Instability and the Response of the Safety Net.” Contemporary Economic Policy 35 (2): 312–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy Bradley, and Ziliak James P.. 2014. “Decomposing Trends in Income Volatility: The ‘Wild Ride’ at the Top and Bottom.” Economic Inquiry 52 (1): 459–76. [Google Scholar]

- Harknett Kristen S., and Caroline Sten Hartnett. 2011. “Who Lacks Support and Why? An Examination of Mothers’ Personal Safety Nets.” Journal of Marriage and Family 73 (4): 861–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heflin Colleen M., and Patillo Mary. 2006. “Poverty in the Family: Race, Siblings, and Socioeconomic Heterogeneity.” Social Science Research 35 (4): 804–22. [Google Scholar]

- Henly Julia R., Danziger Sandra K., and Offer Shira. 2005. “The Contribution of Social Support to the Material Well-Being of Low-Income Families.” Journal of Marriage and Family 67 (1): 122–40. [Google Scholar]

- Henly Julia R., and Lambert Susan J.. 2014. “Unpredictable Work Timing in Retail Jobs: Implications for Employee Work-Life Outcomes.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 67 (3): 986–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Herndon Jill Boylston, Vogel W. Bruce, Bucciarelli Richard L., and Shenkman Elizabeth A.. 2008. “The Effect of Renewal Policy Changes on SCHIP Disenrollment.” Health Services Research 43 (6): 2086–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill Heather D., Morris Pamela A., Gennetian Lisa A., Wolf Sharon, and Tubbs Carly. 2013. “The Consequences of Income Instability for Children’s Well-Being.” Child Development Perspectives 7 (2): 85–90. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill Heather D., and Ybarra Marci A.. 2014. “Less-Educated Workers’ Unstable Employment: Can the Safety Net Help?” Fast Focus . Institute for Research on Poverty, Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- Hipple Steven F., and Sok Emy. 2013. “Tenure of American Workers” Spotlight on Statistics. Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Hollister Matissa N. 2011. “Employment Stability in the US Labor Market: Rhetoric versus Reality.” Annual Review of Sociology 37:305–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hollister Matissa N., and Smith Kristen E.. 2014. “Unmasking the Conflicting Trends in Job Tenure by Gender in the United States, 1983–2008.” American Sociological Review 79 (1): 159–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger David A., and Ann Huff Stevens. 1999. “Is Job Stability in the United States Falling? Reconciling Trends in the Current Population Survey and Panel Study of Income Dynamics.” Journal of Labor Economics 17 (4): S1–S28. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne L. 2000. “Nonstandard Employment Relations: Part-Time, Temporary and Contract Work.” Annual Review of Sociology 26:341–65. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2009. “Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition.” American Sociological Review 74:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2010. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne L., Reskin Barbara F., and Hudson Ken. 2000. “Bad Jobs in America: Standard and Nonstandard Employment Relations and Job Quality in the United States.” American Sociological Review 65 (2): 256–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert Susan J., Fugiel Peter J., and Henly Julia R.. 2014. “Precarious Work Schedules among Early-Career Employees in the US: A National Snapshot.” Research brief. EINet at the University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert Susan J., and Henly Julia R.. 2013. “Double Jeopardy: The Misfit between Welfareto-Work Requirements and Job Realities” 69–84 in Work and the Welfare State: The Politics and Management of Policy Change, edited by Brodkin Evelyn Z. and Gregory Marston. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leete Laura, and Bania Neil. 2010. “The Effect of Income Shocks on Food Insufficiency.” Review of Economics of the Household 8 (4): 505–26. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger Lindsey Jeanne, Ryan Rebecca M., and Kalil Ariel. 2009. “Low-Income Mothers’ Social Support and Children’s Injuries.” Social Science and Medicine 68 (12): 2113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D., Smock Pamela J., and Majumdar Debarun. 2004. “The Relative Stability of Cohabiting and Marital Unions for Children.” Population Research and Policy Review 23 (2): 135–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mills Gregory B., Vericker Tracy, Lippold Kye, Wheaton Laura, and Elkin Sam. 2014. “Understanding the Rates, Causes, and Costs of Churning in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).” Report. Urban Institute, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt Robert, and Gottschalk Peter. 2012. “Trends in the Transitory Variance of Male Earnings: Methods and Evidence.” Journal of Human Resources 47 (1): 204–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt Robert, and Ribar David C.. 2008. “Variable Effects of Earnings Volatility on Food Stamp Participation” 35–62 in Income Volatility and Food Assistance in the United States, edited by Dean Joliffe and Ziliak James P.. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. [Google Scholar]

- Morduch Jonathan, and Schneider Rachel. 2017. The Financial Diaries: How American Families Cope in a World of Uncertainty. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morris Pamela, Hill Heather D., Gennetian Lisa A., Rodrigues Chris, and Tubbs Caroline. 2015. “Income Volatility in U.S. Households with Children: Another Growing Disparity between the Rich and the Poor.” IRP Discussion Paper. Institute for Research on Poverty, Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- Newman Constance. 2008. “Income Volatility and Its Implications for School Lunch” 137–69 in Income Volatility and Food Assistance in the United States, edited by Dean Joliffe and Ziliak James P.. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien Rourke L. 2012. “Depleting Capital? Race, Wealth and Informal Financial Assistance.” Social Forces 91 (2): 375–95. [Google Scholar]

- Offer Shira. 2012. “The Burden of Reciprocity: Processes of Exclusion and Withdrawal from Personal Networks among Low-Income Families.” Current Sociology 60 (6): 788–805. [Google Scholar]

- Pilarz Alejandra Ros, Claessens Amy, and Gelatt Julia. 2016. “Patterns of Child Care Subsidy Use and Stability of Subsidized Care Arrangements: Evidence from Illinois and New York.” Children and Youth Services Review 65:231–43. [Google Scholar]

- Romich Jennifer, and Hill Heather D.. 2017. “Income Instability and Income Support Programs: Recommendations for Policy and Practice.” Family Self-Sufficiency and Stability Research Consortium, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan Rebecca M., Kalil Ariel, and Leininger Lindsey. 2009. “Low-Income Mothers’ Private Safety Nets and Children’s Socioemotional Well-Being.” Journal of Marriage and Family 71 (2):278–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom Heather, and Huerta Sandra. 2013. “The Negative Effects of Instability on Child Development.” Low-Income Working Families Discussion Paper 3. Urban Institute, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Scott EK, and Abelson MJ. 2016. “Understanding the Relationship between Instability in Child Care and Instability in Employment for Families with Subsidized Care.” Journal of Family Issues 37 (3): 344–68. [Google Scholar]

- Scott EK, London AS, and Hurst A. 2005. “Instability in Patchworks of Child Care When Moving from Welfare to Work.” Journal of Marriage and Family 67 (2): 370–86. [Google Scholar]

- Teachman Jay D., and Polonko Karen A.. 1990. “Cohabitation and Marital Stability in the United-States.” Social Forces 69 (1): 207–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wagmiller Robert L. Jr. 2015. “The Temporal Dynamics of Childhood Economic Deprivation and Children’s Achievement.” Child Development Perspectives 9 (3): 158–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Western Bruce, Bloome Deirdre, Sosnaud Benjamin, and Tach Laura. 2012. “Economic Insecurity and Social Stratification.” Annual Review of Sociology 38:341–59. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2016. “Trends in Income Insecurity among U.S. Children, 1984–2010.” Demography 53 (2): 419–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf Sharon, Gennetian Lisa A., Morris Pamela A., and Hill Heather D.. 2014. “Patterns of Income Dynamics among Low-Income Families with Children.” Family Relations 63 (3): 497–510. [Google Scholar]