Abstract

Photorhabdus akhurstii is an insect–parasitic bacterium that symbiotically associates with the nematode, Heterorhabditis indica. The bacterium possesses several pathogenicity islands that aids in conferring toxicity to different insects. Herein, we constructed the plasmid clones of coding sequences of four toxin genes (pirA, tcaA, tccA and tccC; each was isolated from four P. akhurstii strains IARI-SGMG3, IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1) in Escherichia coli and subsequently, their biological activity were investigated against the fourth-instar larvae of the model insect, Galleria mellonella via intra-hemocoel injection. Bioinformatics analyses indicated inter-strain amino acid sequence difference at several positions of the candidate toxins. In corroboration, differential insecticidal activity of the identical toxin protein (PirA, TcaA, TccA and TccC conferred 15–59, 27–100, 25–100 and 33–98% insect mortality, respectively, across the strains) derived from the different bacterial strains was observed, suggesting that the diverse gene pool in Indian strains of P. akhurstii leads to strain-specific virulence in this bacterium. These toxin candidates appear to be an attractive option to deploy them in biopesticide development for managing the insect pests globally.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-02288-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: PirA, TcaA, TccA, TccC, Bacterial strains, RVA assay, Galleria mellonella

Introduction

The gram-negative, non-sporulating, rod-shaped bacteria Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus sp. (Family—Morganellaceae; Class—Gammaproteobacteria; Order—Enterobacteriales) symbiotically associate with insect–parasitic nematodes Steinernema and Heterorhabditis sp. (Family—Steinernematidae, Heterorhabditidae; Class—Chromadorea, Secernentea; Order—Rhabditida), respectively (Boemare et al. 2002; Machado et al. 2018). Nematode infective juveniles (IJs) harbour the bacteria in their intestine and release them directly into the insect hemocoel upon invasion via cuticle or natural openings. The extremely virulent bacteria produce a repertoire of enzymes, toxins and antibiotics that aid in killing the insect host and transform the host tissue into contaminant-free nutrient-rich soup. Post-exhaustion of nutrient reserves, IJs re-associate with bacteria and emerge out of the insect in search of the fresh ones (Blackburn et al. 1998; Webster et al. 2002; ffrench-Constant et al. 2014). The nematode–bacterium pair is capable to kill a wide range of insects encompassing orders Diptera, Hemiptera, Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, Dictyoptera and Orthoptera (Grewal et al. 2005; Lacey and Georgis 2012).

Indian agriculture suffers heavily due to insect pest damage with an estimated 16.8% annual yield loss amounting to US $36 billion (Dhaliwal et al. 2015; Rathee and Dalal 2018). Pest management tactics involving insecticidal Cry (crystal) proteins produced by the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis are increasingly becoming questionable because of the ever increasing reports of resistance development in insect pests in different states of India (Mohan et al. 2016; Nair et al. 2016; Naik et al. 2018; Fand et al. 2019). Incidentally, Photorhabdus toxins were proposed as suitable alternatives to B. thuringiensis-based transgenic crops at global level (ffrench-Constant et al. 2007, 2014; Sheets and Aktories 2017). In view of this, exploring the diversity of different toxins in native strains of Photorhabus sp. may enrich the insect management repository in India and provide important information for deployment of Photorhabdus-based biopesticides in near future (Shankhu et al. 2020).

Photorhabdus sp. secretes a wide range of insecticidal proteins, including oligomeric tripartite toxin complexes (Tc), Photorhabdusinsect-related (Pir) binary toxins, makes caterpillar floppy (mcf) toxins, Photorhabdusvirulence cassettes (PVC), ubiquitous Txp40 toxin, Photorhabdusinsecticidal toxin (Pit), XaxAB and Photox binary toxins (Bowen et al. 1998; Daborn et al. 2002; Waterfield et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2006; Li et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2014; Mathur et al. 2018, 2019; Vlisidou et al. 2019). These toxin proteins were identified from different species and strains of Photorhabdus genera and were expressed in a heterologous host, Escherichia coli in order to test their biological activity against different insects.

In India, Photorhabdus akhurstii (recently elevated to species level from P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii; Machado et al. 2018) symbiotically associates with Heterorhabditis indica to kill the insect pests in different cropping systems. In our laboratory, a de novo genome sequencing analysis of five P. akhurstii strains isolated from different geographical locations indicated considerable inter-strain sequence divergence (Somvanshi et al. 2019). In parallel, we have demonstrated the strain-specific toxicity of P. akhurstii Txp40 and TcaB (belongs to multi subunit Tc toxin) protein may be related to their altered amino acid sequences (Mathur et al. 2018, 2019). In the present study, we have cloned and characterized a number of toxins (TcaA, TccA, TccC and PirA) from four different strains of P. akhurstii and showed their differential biological activity (via Rapid Virulence Annotation (RVA) assay; Waterfield et al. 2008; Ullah et al. 2014) can be correlated to their sequence divergence in different strains.

Materials and methods

Bacteria and nematode culture

The four strains of P. akhurstii namely IARI-SGMG3 (16S rRNA accession no. JX221722), IARI- SGGJ2 (KJ995729), IARI-SGHR2 (HQ637411) and IARI-SGMS1 (HQ637414) were extracted from the IJs of H. indica which were collected from various geographic locations of India, such as Meghalaya, Gujarat, Haryana and Maharashtra, respectively. Nematode strains were multiplied on model insect larvae (fourth-instar) of Galleria mellonella by following the White’s trap method (McMullen and Stock 2014). After collection from White’s trap, freshly harvested IJs were surface-sterilized with 2% NaOCl and sterile distilled water followed by manual crushing of IJs in a tissue grinder. One loop of the ground suspension was streaked on Petri dishes containing nutrient bromothymol blue agar (NBTA; ingredients are detailed in Kumar et al. 2016) and incubated for 48 h at 28 °C. Next, pure green bacterial colonies were isolated and their strain identity was confirmed via 16S rDNA sequencing.

Cloning and sequencing of toxin genes

The protein sequences of P. luminescens toxin genes tcaA (Genbank accession number: AAC38623), tccA (AAC38628), tccC (AAC38630) and pirA (ABE68878) were used as the query in non-redundant database of NCBI for translated nucleotide sequences via tBLASTn algorithm. The open reading frames (ORFs) of 3288, 2898, 3132 and 417 bp corresponding to tcaA, tccA, tccC and pirA, respectively, were identified and primers were designed for those sequences using Primer3Plus server with default parameters. Primer details are given in Supplementary Table S1.

The genomic DNA was isolated from four strains of P. akhurstii (bacteria were multiplied in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth at 28 °C for 48 h and harvested when OD600nm of the culture reached to 1.2–1.5) using PureLink genomic DNA mini kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of the DNA were assessed in a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by resolving in 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel. ORFs of tcaA, tccA, tccC and pirA were PCR-amplified from different strains using high-fidelity Phusion DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) enzyme. Inserts were cloned into pGEM-T (Promega) vector via TA cloning followed by electroporation-based transformation into E. coli DH5α competent cells (New England Biolabs). Recombinant plasmids were isolated from the PCR-positive clones (cultured on LB agar supplemented with 50 µg/ml ampicillin) using Plasmid Miniprep kit (Qiagen). All the candidate toxin gene sequences were determined via Sanger sequencing (each gene was sequenced twice). For longer sequences primer walking was employed. Primer details are given in S1 Table. Further, recombinant pGEM-T clones (contains T7 RNA polymerase promoter that drives the expression of an ORF) were allowed to infect E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (RNA polymerase of this E. coli strain recognizes T7 promoter) for testing the biological activity of the toxin. In parallel, to validate the targeted overexpression of the toxin proteins, candidate genes were cloned into a protein expression vector, pET29a via restriction digestion followed by transformation into E. coli BL21 cells. Cell cultures were treated with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) in LB broth at 37 °C for 4 h and protein induction was checked on 12% SDS-PAGE with reference to uninduced cell culture as described previously (Mathur et al. 2018, 2019).

Bioinformatics analyses of toxin genes

Obtained toxin gene sequences were translated into amino acid sequences (via ExPASy server) which were interrogated via BLASTp in NCBI non-redundant database and examined for conserved domains using SMART (https://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/), InterProScan (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/), motif database (https://molbiol-tools.ca/Motifs.htm) and ThreaDom (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/) algorithms. SignalP 4.1 and TMHMM 2.0 (https://www.cbs.dtu.dk/) servers were used to search signal peptide and transmembrane helix in the protein. Amino acid sequences were aligned with their homologues in other gram-negative bacterial species using CLUSTALW multiple sequence alignment (MSA) tool with default parameters. Phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA10 bioinformatics tool using a maximum-likelihood phylogeny based on the selection of the appropriate model (Le and Gascuel) using MODELTEST.

Insect rearing

The greater wax moth (G. mellonella) first-instar larvae were reared from the eggs of previous rearing culture at 28 ± 2 °C and 70% ± 5% relative humidity (RH) on an artificial diet containing wheat flour (200 g), corn flour (200 g), milk powder (50 g), dried yeast powder (20 g), honey (75 ml) and glycerine (75 ml). 20 mg kanamycin/kg body weight of insect was co-administered in the diet to prevent bacterial contamination. The pupation of larvae took place during 6–7th instar stage and adults emerged from pupal cocoon within 10–15 days. The adult moths were collected, surface sterilized with 70% ethanol and kept for mating in closed aerated containers. Eggs from the next generation were hatched and reared in sterile diet till the fourth-instar larval stage was attained. Fourth-instar larvae were surface sterilized and used in the bioassays.

Determination of insecticidal activity of toxin genes via RVA assay

The individual colonies of E. coli BL21(DE3) containing TcaA, TccA, TccC and PirA clones were cultured as described above. The culture broth was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 min at 4 °C. After decanting the supernatants, pellets were re-suspended in 50 mM Tris buffer and sonicated on ice. Protein concentration of the sonicated sample was estimated via Bradford’s method using BSA as standard. 5–10 µl of the sample (amounting to 10 µg of protein) was injected into the hemocoel of G. mellonella through the prolegs using a 26 s gauge, 10 µl capacity Hamilton syringe (Sigma-Aldrich). As control, E. coli harbouring the empty pGEM-T plasmid was used. In addition, sonicated samples were thermally (heat treated at 70 °C for 15 min) and chemically (digested with 10 µg/ml of Proteinase K) inactivated and injected into the insect hemocoel to ascertain whether insecticidal activity was conferred by the candidate toxins. In parallel, post-centrifugation of culture broth, pellets were diluted to 103 CFU/µl which was used as the whole-cell injection sample. Supernatants were 50-fold concentrated via SpeedVac vacuum concentrator (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and applied as another injection sample.

Insects were incubated at 28 °C and 70% RH in 6-well polystyrene plates. Insects were checked regularly for symptom development and mortality. Each treatment consisted of 15 test insects and the whole experiment was repeated thrice. The mortality data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD (honest significant difference) test in SAS statistical package.

Results

Considerable sequence divergence across the P. akhurstii strains of different geographic locations

An ORF of tcaA (3288 bp), tccA (2898 bp), tccC (3132 bp) and pirA (417 bp) was successfully PCR-amplified from the genomic DNA of all the four strains of P. akhurstii and subsequently cloned in pGEM-T and sequenced twice. The agarose gel photographs of the selective DNA fragments are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Genbank accession numbers obtained for toxin gene sequences from different strains are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

NCBI Genbank accession numbers obtained for different toxin gene sequences

| Gene name | P. akhurstii strain | Accession number |

|---|---|---|

| pirA | IARI-SGMG3 | MN496042 |

| pirA | IARI-SGGJ2 | MN496043 |

| pirA | IARI-SGHR2 | MN496044 |

| pirA | IARI-SGMS1 | MN496045 |

| tcaA | IARI-SGMG3 | MN496046 |

| tcaA | IARI-SGGJ2 | MN496047 |

| tcaA | IARI-SGHR2 | MN496048 |

| tcaA | IARI-SGMS1 | MN496049 |

| tccA | IARI-SGMG3 | MN496050 |

| tccA | IARI-SGGJ2 | MN496051 |

| tccA | IARI-SGHR2 | MN496052 |

| tccA | IARI-SGMS1 | MN496053 |

| tccC | IARI-SGMG3 | MN496054 |

| tccC | IARI-SGGJ2 | MN496055 |

| tccC | IARI-SGHR2 | MN496056 |

| tccC | IARI-SGMS1 | MN496057 |

A BLASTp search (Query coverage—100%; Expect value—0) of PirA revealed homologues in P. akhurstii strain K1 (sequence identity—99.25%), P. luminescens (98.55%), P. bodei (93.98%), P. temperata (90.98%), P. asymbiotica (88.72%), P. heterorhabditis (87.97%), P. australis (87.22%), P. namnaonensis (61.84%) and P. laumondii (49.9%). As expected, P. akhurstii PirA shared homology with other entomopathogenic bacteria, Xenorhabdus nematophila (55.8%), X. poinarii (55%), X. beddingii (54.1%), X. japonica (52%), X. budapestensis (51.52%), X. ehlersii (50.5%) etc. In addition, P. akhurstii PirA was homologous to gram-negative, animal- and plant-pathogenic bacteria, Yersinia enterocolitica (47.37%), Y. aldovae (48.87%), Y. intermedia (46.95%), Y. nurmii (45.9%) and Pectobacterium carotovorum (50.98%). A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed to analyze the relationship of PirA derived from four strains of P. akhurstii with 29 homologues from other bacterial species that belonged to only three genera of the Enterobacteriales order. The tree (Fig. 1) showed that P. akhurstii PirA of strain IARI-SGMG3, IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1 constitute a distinct group that includes strain K1 and P. luminescens PirA. Interestingly, PirA homologue of plant-pathogenic P. carotovorum branches nearest to this clade in contrast to animal-pathogenic Yersinia sp. which branches farthest from this clade. However, the clade comprising X. khoisanae, X. miraniensis, X. nematophila, X. poinarii and X. koppenhoeferi was nearer to P. akhurstii clade than the clade comprising P. asymbiotica, P. australis, P. heterorhabditis, P. bodei and P. temperata. When PirA sequence from P. luminescens was aligned with its homologues from different strains of P. akhurstii, amino acid residues differed at positions 17, 31, 66, 84, 96 and 113. In addition, functionally similar amino acid changes were documented at positions 32, 42, 43, 114, 127 and 129 (Fig. 2).

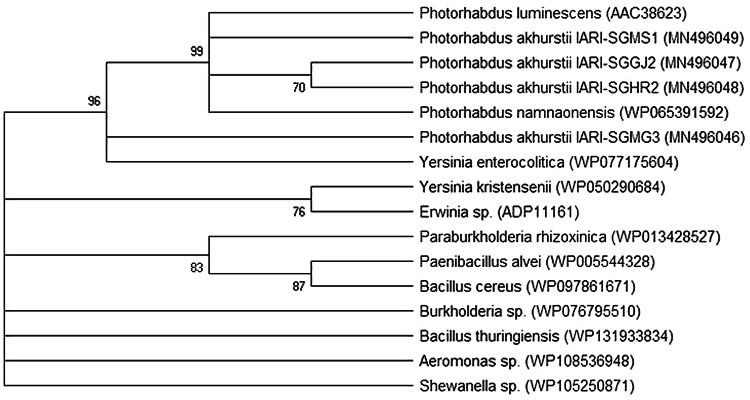

Fig. 1.

Sequence conservation of P. akhurstii PirA protein across the different bacterial genera of order Enterobacteriales. A maximum-likelihood phylogeny of PirA and its putative homologues is shown. Genbank accession numbers for different gene sequences are provided in the parentheses. Bootstrap values (corresponding to different cluster nodes) are shown as percentages. The bootstrap consensus tree was inferred from 1000 replicates to represent the evolutionary history and branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 50% bootstrap replicates were collapsed. Sequence alignments were manually corrected by eliminating the gaps and missing data

Fig. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of amino acid residues of PirA protein derived from P. akhurstii strain IARI-SGMG3, IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1 with P. luminescens PirA. Amino acid residues differed at 17 (neutral threonine changed to acidic glutamate), 31 (basic histidine altered to neutral tyrosine), 66 (neutral serine changed to basic lysine), 84 (nonpolar tyrosine altered to polar, sulphur-containing cysteine), 96 (nonpolar alanine changed to polar, hydroxyl-containing serine) and 113 (polar serine to nonpolar glycine)

Conversely, because of the larger sequence size, P. akhurstii TcaA homologues were found in comparatively lesser number of bacterial species (16 homologues from Enterobacteriales order). A BLASTp search (Query coverage—100%; E value—0) indicated 96.44, 93.8, 67.24, 55.24, 47.7, 49.9, 50.6, 42.79, 41.18, 39.78, 50.64 and 48.16% sequence identity in P. luminescens, P. namnaonensis, Y. enterocolitica, Y. kristensenii, Erwinia sp., Burkholderia sp., Paraburkholderia rhizoxinica, Bacillus thuringiensis, B. cereus, Paenibacillus alvei, Aeromonas sp. and Shewanella sp., respectively. The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3) exhibited clustering of P. akhurstii TcaA of strain IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1 with P. luminescens and P. namnaonensis TcaA to form a distinct clade. Intriguingly, P. akhurstii IARI-SGMG3 and Y. enterocolitica sub-clustered nearer to that clade. Other homologues belonging to genera Bacillus, Erwinia, Burkholderia, Aeromonas, Shewanella etc. branched away from P. akhurstii clade. When TcaA sequence from P. luminescens was aligned with its homologues from different strains of P. akhurstii, amino acid residues differed at numerous positions. Most interestingly, unlike of other strains additional two amino acids, such as asparagine and threonine was documented at position 337 and 338 of TcaA protein of P. akhurstii strain IARI-SGMG3 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Sequence conservation of P. akhurstii TcaA protein across the different bacterial genera of order Enterobacteriales. A maximum-likelihood phylogeny of TcaA and its putative homologues is shown. Genbank accession numbers for different gene sequences are provided in the parentheses. Cluster nodes are strongly supported by a bootstrap analysis (1,000 replicates) value of more than 70%

Fig. 4.

MSA of amino acid residues of TcaA protein derived from P. akhurstii strain IARI-SGMG3, IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1 with P. luminescens TcaA. Amino acid residues differed at numerous positions. When compared with other strains, insertion of two similar amino acids, such as asparagine and threonine (polar, neutral) at position 337 and 338 is evident in IARI-SGMG3 TcaA

Similarly, P. akhurstii TccA homologues were found only in 15 entries from Enterobacteriales order. A BLASTp search (Query coverage—100%; E value—0) indicated 97.72, 92.86, 88.82, 55.24, 47.88, 88.31, 87.72, 56.98, 51.41, 38.24 and 48.37% sequence identity in P. luminescens, P. laumondii, P. khanii, P. namnaonensis, P. bodei, P. temperata, P. thracensis, Burkholderia sp., Enterobacter sp., Salmonella enterica and Granulibacter bethesdensis, respectively. The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5) exhibited clustering of P. akhurstii TccA of strain IARI-SGMG3 with P. luminescens TccA followed by the close sub-clustering with P. akhurstii strain IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1. TccA homologues from other bacterial genera such as Burkholderia, Granulibacter, Enterobacter and Salmonella branched away from P. akhurstii group. When TccA sequence from P. luminescens was aligned with its homologues from different strains of P. akhurstii, amino acid residues differed at plethora of positions (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Sequence conservation of P. akhurstii TccA protein across the different bacterial genera of order Enterobacteriales. A maximum-likelihood phylogeny of TccA and its putative homologues is shown. Genbank accession numbers for different gene sequences are provided in the parentheses. Cluster nodes are strongly supported by a bootstrap analysis (1000 replicates) value of more than 70%

Fig. 6.

MSA of amino acid residues of TccA protein derived from P. akhurstii strain IARI-SGMG3, IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1 with P. luminescens TccA. Amino acid residues differed at several positions. For example—polar, hydroxyl threonine changed to nonpolar, aliphatic alanine at position 253, 415, 779, 858 and 914; polar, hydroxyl serine altered to nonpolar, aliphatic glycine at position 83, 256 and 656; polar, hydroxyl threonine changed to nonpolar, aliphatic valine at position 277 and 868; polar, hydroxyl threonine changed to nonpolar, aliphatic isoleucine at position 340 and 630; neutral alanine altered to acidic glutamate at position 369

P. akhurstii TccC homologues were found in 13 entries from Enterobacteriales order. A BLASTp search (Query coverage—100%; E value—0) indicated significant sequence identity exclusively in insect–parasitic bacteria including P. luminescens (99.04%), P. namnaonensis (92.65%), P. khanii (89.17%), P. temperata (89.53%), P. thracensis (90.8%), P. bodei (93.48%), P. laumondii (93.58%), X. nematophila (65.18%) and X. bovienii (67.57%). The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 7) showed clustering of P. akhurstii TccC of strain IARI-SGHR2 with P. luminescens TccC followed by the close sub-clustering with P. akhurstii strain IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGMG3 and IARI-SGMS1. As expected, TccC homologues from Xenorhabdus group branched farther from P. akhurstii clade. When TccC sequence from P. luminescens was aligned with its homologues from different strains of P. akhurstii, amino acid residues differed at positions 37, 56, 65, 81, 86, 107, 139, 140, 145, 158, 405, 452 and 491. Additionally, functionally similar amino acid alterations were observed at positions 33, 50, 181, 423 and 614 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Sequence conservation of P. akhurstii TccC protein across the different bacterial genera of order Enterobacteriales. A maximum-likelihood phylogeny of TccC and its putative homologues is shown. Genbank accession numbers for gene different sequences are provided in the parentheses. Cluster nodes are strongly supported by a bootstrap analysis (1,000 replicates) value of more than 70%

Fig. 8.

MSA of amino acid residues of TccC protein derived from P. akhurstii strain IARI-SGMG3, IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1 with P. luminescens TccC. Amino acid residues differed at a number of positions. For example—polar, hydroxyl threonine changed to nonpolar, aliphatic alanine at position 65, 86 and 405; neutral glycine altered to acidic glutamate at position 37; polar, amide-containing glutamine changed to nonpolar, aromatic tyrosine at position 56; neutral glycine altered to acidic aspartate at position 81; polar, hydroxyl serine changed to nonpolar, cyclic proline at position 107; polar serine altered to nonpolar, aromatic phenylalanine at position 139; polar, amide-containing asparagine changed to nonpolar, cyclic proline at position 140; neutral, amide-containing glutamine altered to basic lysine at position 145; polar, hydroxyl serine changed to nonpolar, aliphatic alanine at position 158; neutral glutamine altered to basic arginine at position 452; polar, hydroxyl serine changed to nonpolar, aliphatic glycine at position 491

Differential insecticidal activity of candidate toxins derived from different P. akhurstii strains

The biological activity of E. coli (as whole cell or sonicated) harbouring the recombinant clones (pGEM-T::pirA, pGEM-T::tcaA, pGEM-T::tccA and pGEM-T::tccC) was tested by intra-hemocoel injection assay to deliver the candidate toxins directly into the insect hemolymph alike the release of entomopathogenic bacteria by its nematode partner while infecting host insects. Time–response curves indicated that mean percent survival of G. mellonella gradually decreased with increasing incubation period after the toxin injection (candidate toxins were extracted from P. akhurstii strain IARI-SGMG3; Fig. 9). For PirA, insect mortality data significantly (P < 0.05, as compared to empty plasmid control) ranged between 15–59% (sonicated) and 10–55% (whole cell) during 1–3 days post-inoculation (DPI; Fig. 9a). Conversely, TcaA conferred 27–100% (sonicated, P < 0.01) and 20–85% (whole cell, P < 0.05) insect toxicity during 1–3 DPI (Fig. 9b). Similarly, TccA caused 25–100% (sonicated, P < 0.05) and 22–95% (whole cell, P < 0.05) insect mortality during the same period (Fig. 9c). TccC resulted in 33–98% (sonicated, P < 0.01) and 21–87% (whole cell, P < 0.05) insect mortality during 1–3 DPI (Fig. 9d). In case of TcaA and TccC injection, sonicated cells exhibited significantly greater (P < 0.01) insecticidal effect as compared to whole-cell samples (Fig. 9b, d). Therefore, for bacterial strain-specific toxicity comparison, sonicated samples were used. The supernatants, heat-inactivated and proteinase K-digested samples showed nonsignificant (P > 0.05) and negligible insect toxicity as compared to control (Fig. 9), suggesting the candidate toxin-specific insecticidal activity in our assay.

Fig. 9.

The biological activity of PirA (a), TcaA (b), TccA (c) and TccC (d) toxins derived from P. akhurstii strain IARI-SGMG3 on fourth-instar larvae of G. mellonella. Different forms of the toxin (whole E. coli cells (103 CFU) harbouring recombinant plasmids, sonicated cells (10 µg protein) harbouring recombinant plasmids, heat-inactivated sonicated cells (10 µg) and Proteinase K-digested sonicated cells (10 µg)) were intra-hemocoel injected into the insect larvae and incubated for 3 days. Concentrated cell supernatants (1 µg) and E. coli cells (10 µg) harbouring the empty plasmid were used as the control. X- and Y-axis in time–response curves indicate days after toxin injection and percent insect mortality, respectively. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean of three experiments. Asterisks indicate the significant difference in treatment (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01) when compared with the control

Subsequently, toxicity data of all the four strains were compared together. Toxins isolated from all the strains conferred significantly greater (P < 0.01) insecticidal activity at 1–3 DPI when compared with the control (Fig. 10). For PirA toxin, strain-specific insecticidal activity was recorded between IARI-SGGJ2 and IARI-SGMS1/IARI-SGHR2 at 3 DPI (P < 0.01; Fig. 10a). Similarly, for TcaA, differential insecticidal activity was documented among IARI-SGMS1 and IARI-SGMG3/IARI-SGGJ2/ IARI-SGHR2 at both 2 and 3 DPI (P < 0.01; Fig. 10b). For TccA, differential insecticidal potency was observed between IARI-SGMG3/IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGGJ2/IARI-SGMS1 at all the time points, i.e. 1–3 DPI (P < 0.01; Fig. 10c). In corroboration, for TccC, strain-specific insecticidal activity was documented among IARI-SGMG3/ IARI-SGGJ2 and IARI-SGHR2/IARI-SGMS1 at all the time points (P < 0.01; Fig. 10d). Larvae injected with the Tc toxin of either strain showed rapid blackening of hemolymph and became completely morbid at 72 h (Fig. 10e).

Fig. 10.

Strain-specific biological activity of PirA (a), TcaA (b), TccA (c) and TccC (d) toxins derived from P. akhurstii strain IARI-SGMG3, IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1 on fourth-instar larvae of G. mellonella. Sonicated E. coli cells (10 µg protein) harbouring recombinant plasmids were intra-hemocoel injected into the insect larvae and incubated for 3 days. E. coli cells (10 µg) harbouring the empty plasmid were used as the control. X- and Y-axis in time–response curves indicate days after toxin injection and percent insect mortality, respectively. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean of three experiments. Treatments with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.01, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Images (e) depict the hemolymph discoloration in TcaA toxin-challenged larvae as compared to healthy insect at 72 h after injection

In parallel, biological activity of the sonicated E. coli cells harbouring the recombinant expression clones (pET29a::pirA, pET29a::tcaA, pET29a::tccA and pET29a::tccC) corroborated with the RVA assay (data not shown). A representative SDS–PAGE photograph of overexpression of the target proteins are shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

Discussion

Previously, in our laboratory, strain (six strains collected from different agro-climatic zones of India)-specific virulence of P. akhurstii was demonstrated against G. mellonella in vitro; IARI-SGMG3 was found to be the most virulent one (Kushwah et al. 2017). This prompted us to investigate the inter-strain sequence variance of the toxin genes/proteins which are the determinant of insecticidal activity of the bacteria. Expectedly, we found inter-strain (four strains were used for the study, namely, IARI-SGMG3, IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1) amino acid sequence divergence at numerous positions of all the candidate toxin proteins, i.e. PirA, TcaA, TccA and TccC. Interestingly, unlike of other strains an addition of two functionally similar amino acids in TcaA protein of strain IARI-SGMG3 was documented at positions 337 and 338. Most importantly, identical amino acid alterations among the strains encoding TccA (threonine changed to alanine at position 253, 415, 779, 858 and 914; serine altered to glycine at position 83, 256 and 656; threonine changed to valine at position 277 and 868; threonine altered to isoleucine at position 340 and 630) and TccC (threonine changed to alanine at position 65, 86 and 405) were also observed. Earlier, it was experimentally proved that a single amino acid residue alteration can significantly modify the biological activity conferred by the corresponding proteins (Joshi et al. 2008; Henderson 2010; Yang et al. 2012; Mathur et al. 2018, 2019). Therefore, in the present study, we assessed the biological activity of candidate toxin genes (cloned from four P. akhurstii strains) in G. mellonella via RVA assay.

Sequencing of P. luminescens revealed several pathogenicity islands each encoding a number of putative toxins (ffrench-Constant et al. 2000; Duchaud et al. 2003). Strategies such as chromatography-based purification and cloning in cosmid/plasmid library (RVA assay) were employed to screen the toxin genes against different insects (Blackburn et al. 1998; Waterfield et al. 2008). Nevertheless, toxins isolated through different purification strategies may lose their biological activity because of alterations in their structure or, it may remain dormant in order to avoid inactivation in hostile insect gut environment (Yao et al. 2009; Ullah et al. 2014). On the contrary, cosmid/plasmid clone approach provides essential in vivo factors that facilitate the interaction of toxins with the host proteins (Morgan et al. 2001; Waterfield et al. 2008). In view of this, in the present study, plasmid clones containing the ORF of PirA and three subunits of Tc toxin (TcaA, TccA and TccC) were tested for insecticidal activity via intra-hemocoel injection in fourth-instar G. mellonella larvae. Considering that Tc genes are of large molecular weight toxins and contain many isoforms (Sheets and Aktories 2017), different Tc subunits located in different pathogenic islands were used in the current study.

RVA assays indicated that sonicated and whole cells harbouring the recombinant clones conferred the greatest insecticidal effect at 3 days after injection (PirA: 55–59%; TcaA: 85–100%; TccA: 95–100%; TccC: 87–98%), in comparison to negligible toxicity caused by cell supernatants and cells harbouring empty plasmid. Insect mortality rate dropped to insignificant level (as compared to control) when cells harbouring the recombinant clones were inactivated by heat treatment (proteins lose its tertiary and quaternary conformation during heat stress; Aloy and Russell 2003) and digested by proteinase K (renders the enzyme function inactive; Ebeling et al. 1974; Kraus et al. 1976) independently, indicating the proteinaceous nature of the candidate toxins. These results also confirmed that PirA, TcaA, TccA and TccC toxins were exclusively responsible for their insecticidal activity and no other factors were supportive for insect mortality. However, within the candidate toxins, PirA exhibited least toxicity at the same time point. Notably, PirA (mimics the insect juvenile hormone esterase enzyme) and PirB of P. luminescens when injected together in G. mellonella, full insecticidal activity of the binary toxin PirAB was achieved (Waterfield et al. 2005). The greater insecticidal activity of Tc toxins in our study is not surprising because Tc genes are considered to be the most important Photorhabdus toxin candidate because they contain midgut-pore forming domain alike of Cry toxins in B. thuringiensis and possess ADP-ribosyltransferase that targets host actins (Sheets and Aktories 2017). As expected, the phylogenetic analysis of P. akhurstii TcaA indicated its genealogical ties with homologues in B. thuringiensis and B. cereus. Intriguingly, phylogeny of PirA indicated its homologues in P. akhurstii and P. luminescens were closer to several Xenorhabdus species including X. nematophila and X. poinarii, but were farther from homologues in P. asymbiotica, P. temperata, P. bodei, P. laumondii, etc. Further, X. beddingii, X. japonica, X. ehlersii, X. ishibashi, etc. formed a distant subgroup from the original Xenorhabdus group. This is suggestive of the possibility that PirA is located in different part of the genome of different Photorhabdus species and PirA is mobile within the genome. A similar assumption for Photorhabdus mcf toxin was reported earlier (Wilkinson et al. 2009).

When mortality of G. mellonella rendered by toxins from different strains of P. akhurstii was compared, a strain-dependent insecticidal activity especially for TcaA, TccA, and TccC was documented (IARI-SGMG3 was found to cause the greatest toxic effect with mortality data for Tc toxins ranging from 98–100% at 3 days after injection). For PirA, significantly differential toxicity of strain IARI-SGGJ2 as compared to other strains was only recorded at 3 DPI. On the contrary, significantly greatest toxicity of IARI-SGMG3 as compared to other strains was recorded at 2 and 3 DPI for TcaA. TccA derived from IARI-SGMG3/IARI-SGHR2 conferred significantly higher toxicity than IARI-SGGJ2/IARI-SGMS1 at all the time points, i.e. 1, 2 and 3 DPI. Similarly, TccC isolated from IARI-SGMG3/IARI-SGGJ2 caused significantly greater toxicity than IARI-SGHR2/IARI-SGMS1 at all the time points. These findings support the hypothesis that the divergence in amino acid sequences of toxin proteins gleaned from different microbial strains may lead to differential biological activity conferred by those microorganisms. It is to be noted that the symbiotic partners (different strains of H. indica) of these bacterial strains were collected from geographically diverse locations, i.e. Meghalaya (IARI-SGMG3), Gujarat (IARI-SGGJ2), Haryana (IARI-SGHR2) and Maharashtra (IARI-SGMS1) state of India. Incidentally, Gujarat and Maharashtra comes under the Bt-cotton belt of India (Mohan et al. 2016; Naik et al. 2018).

Conclusions

Owing to the development of insect resistance to B. thuringiensis-based transgenic crops in India and worldwide the necessity of an alternative biological control agent for insect pest management has been realized (Carrière et al. 2019). Photorhabdus toxins have been proposed as an attractive alternative to manage insect pests globally (ffrench-Constant et al. 2014; Sheets and Aktories 2017). Because of the vast and diverse agro-climatic zones, Indian crop production is affected by a wide range of insects (Dhaliwal et al. 2015). It is assumed that a diverse gene pool of P. akhurstii (Somvanshi et al. 2019) is existent which arises from the long coevolution of insects with the entomopathogenic nematodes. However, exploring the toxin gene diversity in P. akhurstii is yet an underexploited territory. In view of this, the present study enriches the repository for P. akhurstii toxin candidates which warrant further investigation. In addition, the differential virulence of P. akhurstii strains due to the amino acid sequence divergence in their corresponding toxin protein sequences is also an important finding from this study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Table S1. List of oligonucleotides employed for cloning and sequencing of Photorhabdus toxin genes. Annealing temperature for each PCR reaction was 60°C.Figure S1. Agarose gel photographs showing the PCR amplified fragments of toxin genes, such as pirA (417 bp), tcaA (3288 bp), tccA (2898 bp) and tccC (3132 bp) from the genomic DNA of P. akhurstii strains IARI-SGMG3, IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1.Figure S2. SDS-PAGE analysis of P. akhurstii (IARI-SGMG3) toxins induced by 1 mM IPTG for 4 h in E. coli BL21 cells. Lanes: M—protein molecular weight marker, 1—uninduced BL21 cells harboring TcaA, 2—induced BL21 cells harboring TcaA, 3—uninduced BL21 cells harboring TccC, 4—induced BL21 cells harboring TccC, 5—uninduced BL21 cells harboring TccA, 6—induced BL21 cells harboring TccA, 7—uninduced BL21 cells harboring PirA, 8—induced BL21 cells harboring PirA. Arrows indicate the overexpression of target protein. The calculated molecular mass (using Expasy ProtParam tool; https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) of TcaA, TccC, TccA and PirA was 120, 111, 105 and 15 kDa, respectively. (PDF 366 kb)

Funding

This study was supported by Science and Engineering Research Board (Grant Number YSS/2014/000452).

References

- Aloy P, Russell RB. Interprets: protein interaction prediction through tertiary structure. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:161–162. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn M, Golubeva E, Bowenffrench-Constant DRH. A novel insecticidal toxin from Photorhabdus luminescens, Toxin complex a (Tca), and its histopathological effects on the midgut of Manduca sexta. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3036–3041. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.3036-3041.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boemare N. Interactions between the partners of the entomopathogenic bacterium nematode complexes, Steinernema-Xenorhabdus and Heterorhabditis-Photorhabdus. Nematology. 2002;4:601–603. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen D, Rocheleau TA, Blackburn M, Andreev O, Golubeva E, Bhartiaffrench-Constant RRH. Insecticidal toxins from the bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Science. 1998;280:2129–2132. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SE, Cao AT, Dobson P, Hines ER, Akhurst RJ. East PD (2006) Txp40, a ubiquitous insecticidal toxin protein from Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:1653–1662. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1653-1662.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrière Y, Brown ZS, Downes SJ, Gujar G, Epstein G, Omoto C, et al. Governing evolution: a socioecological comparison of resistance management for insecticidal transgenic Bt crops among four countries. Ambio. 2019;49:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s13280-019-01167-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daborn PJ, Waterfield N, Silva CP, Au CPY, Sharma S, ffrench-Constant RH. A single Photorhabdus gene, makes caterpillars floppy (mcf), allows Escherichia coli to persist within and kill insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10742–10747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102068099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaliwal GS, Jindal V, Mohindru B. Crop losses due to insect pests: global and Indian scenario. Ind J Entomol. 2015;77:165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Duchaud E, Rusniok C, Frangeul L, Buchrieser C, Givaudan A, Taourit S, et al. The genome sequence of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1307–1313. doi: 10.1038/nbt886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebeling W, Hennrich N, Klockow M, Metz H, Orth HD, Lang H. Proteinase K from Tritirachium album Limber. Eur J Biochem. 1974;47:91–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fand BB, Nagrare VS, Gawande SP, Nagrale DT, Naikwadi BV, Deshmukh V, Gokte-Narkhedkar N, Waghmare VN. Widespread infestation of pink bollworm, Pectinophora gossypiella (Saunders)(Lepidoptera: Gelechidae) on Bt cotton in Central India: a new threat and concerns for cotton production. Phytoparasitica. 2019;47:313–325. [Google Scholar]

- ffrench-Constant RH, Dowling A, Waterfield NR. Insecticidal toxins from Photorhabdus bacteria and their potential use in agriculture. Toxicon. 2007;49:436–451. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ffrench-Constant RH, Dowling A. Photorhabdus toxins. In: Dhadialla TS, Gill SS, editors. Advances in insect physiology: insect midgut and insecticidal proteins. 47. San Francisco: Elsevier; 2014. pp. 343–388. [Google Scholar]

- ffrench-Constant RH, Waterfield N, Burland Perna Daborn VNTPJ, Bowen D, et al. A genomic sample sequence of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens W14: potential implications for virulence. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3310–3329. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.8.3310-3329.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal PS, Ehlers RU, Shapiro-Ilan DI. Critical issues and research needs for expanding the use of nematodes in biocontrol. In: Grewal PS, Ehlers RU, Shapiro-Ilan DI, editors. Nematodes as biocontrol agents. UK: CAB International, Wallingdord; 2005. pp. 479–528. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B. Integrating the cell stress response: a new view of molecular chaperones as immunological and physiological homeostatic regulators. Cell Biochem Funct. 2010;28:1–14. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi MC, Sharma A, Kant S, Birah A, Gupta GP, Khan SR, et al. An insecticidal GroEL protein with chitin binding activity from Xenorhabdus nematophila. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28287–28296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804416200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus E, Kiltz HH, Femfert UF. The specificity of proteinase K against oxidized insulin B chain. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1976;357:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Kushwah J, Ganguly S, Garg V, Somvanshi VS. Proteomic investigation of Photorhabdus bacteria for nematode–host specificity. Indian J Microbiol. 2016;56:361–367. doi: 10.1007/s12088-016-0594-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushwah J, Kumar P, Garg V, Somvanshi VS. Discovery of a highly virulent strain of Photorhabdus luminescens ssp. akhurstii from Meghalaya. India Indian J Microbiol. 2017;57:125–128. doi: 10.1007/s12088-016-0628-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey LA, Georgis R. Entomopathogenic nematodes for control of insect pests above and below ground with comments on commercial production. J Nematol. 2012;44:218–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Wu G, Liu C, Chen Y, Qiu L, Pang Y. Expression and activity of a probable toxin from Photorhabdus luminescens. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:785–790. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9246-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado RAR, Wüthrich D, Kuhnert P, Arce CCM, Thönen L, Ruiz C, et al. Whole-genome-based revisit of Photorhabdus phylogeny: proposal for the elevation of most Photorhabdus subspecies to the species level and description of one novel species Photorhabdus bodei sp. nov., and one novel subspecies Photorhabdus laumondii subsp. clarkei subsp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:2664–2681. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur C, Kushwah J, Somvanshi VS, Dutta TK. A 37 kDa Txp40 protein characterized from Photorhabdus luminescens sub sp. akhurstii conferred injectable and oral toxicity to greater wax moth Galleria mellonella. Toxicon. 2018;154:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur C, Phani V, Kushwah J, Somvanshi VS, Dutta TK. TcaB, an insecticidal protein from Photorhabdus akhurstii causes cytotoxicity in the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2019;157:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2019.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen JG, Stock SP. In vivo and in vitro rearing of entomopathogenic nematodes (Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) J Vis Exp. 2014;91:52096. doi: 10.3791/52096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan KS, Ravi KC, Suresh PJ, Sumerford D, Head GP. Field resistance to the Bacillus thuringiensis protein Cry1Ac expressed in Bollgard® hybrid cotton in pink bollworm, Pectinophora gossypiella (Saunders), populations in India. Pest Manag Sci. 2016;72:738–746. doi: 10.1002/ps.4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JA, Sergeant M, Ellis D, Ousley M, Jarrett P. Sequence analysis of insecticidal genes from Xenorhabdus nematophilus PMFI296. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:2062–2069. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.5.2062-2069.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik VC, Kumbhare S, Kranthi S, Satija U, Kranthi KR. Field-evolved resistance of pink bollworm, Pectinophora gossypiella (Saunders)(Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), to transgenic Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) cotton expressing crystal 1Ac (Cry1Ac) and Cry2Ab in India. Pest Manag Sci. 2018;74:2544–2554. doi: 10.1002/ps.5038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair R, Kamath SP, Mohan KS, Head G, Sumerford DV. Inheritance of field-relevant resistance to the Bacillus thuringiensis protein Cry1Ac in Pectinophora gossypiella (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) collected from India. Pest Manag Sci. 2016;72:558–565. doi: 10.1002/ps.4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathee M, Dalal P. Emerging insect pests in Indian agriculture. Ind J Entomol. 2018;80:267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Shankhu PY, Mathur C, Mandal A, Sagar D, Somvanshi VS, Dutta TK. Txp40, a protein from Photorhabdus akhurstii conferred potent insecticidal activity against the larvae of Helicoverpa armigera, Spodoptera litura and S. exigua. Pest Manag Sci. 2020;76:2004–2014. doi: 10.1002/ps.5732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets J, Aktories K. Insecticidal toxin complexes from Photorhabdus luminescens. In: ffrench-Constant RH, editor. The molecular biology of Photorhabdus bacteria. Cham: Springer; 2017. pp. 3–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somvanshi VS, Dubay B, Kushwah J, Ramamoorthy S, Vishnu US, Sankarasubramanian J, et al. Draft genome sequences for five Photorhabdus bacterial symbionts of entomopathogenic Heterorhabditis nematodes isolated from India. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2019;8:e01404–e1418. doi: 10.1128/MRA.01404-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah I, Jang EK, Kim MS, Shin JH, Park GS, Khan A, et al. Identification and characterization of the insecticidal toxin “makes caterpillars floppy” in Photorhabdus temperata M1021 using a cosmid library. Toxins. 2014;6:2024–2040. doi: 10.3390/toxins6072024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlisidou I, Hapeshi A, Healey JR, Smart K, Yang G, Waterfield NR. The Photorhabdus asymbiotica virulence cassettes deliver protein effectors directly into target eukaryotic cells. ELife. 2019;8:e46259. doi: 10.7554/eLife.46259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterfield N, Kamita SG, Hammock BD, Ffrench-Constant R. The Photorhabdus Pir toxins are similar to a developmentally regulated insect protein but show no juvenile hormone esterase activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;245:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterfield NR, Sanchez-Contreras M, Eleftherianos I, Dowling A, Yang G, Wilkinson P, et al. Rapid Virulence Annotation (RVA): identification of virulence factors using a bacterial genome library and multiple invertebrate hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15967–15972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711114105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JM, Chen G, Hu K, Li J. Bacterial metabolites. In: Gaugler R, editor. Entomopathogenic nematology. New York: CABI Publishing, Oxon; 2002. pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P, Waterfield NR, Crossman L, Corton C, Sanchez-Contreras M, Vlisidou I, et al. Comparative genomics of the emerging human pathogen Photorhabdus asymbiotica with the insect pathogen Photorhabdus luminescens. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:1–22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zeng HM, Lin HF, Yang XF, Liu Z, Guo LH, Yuan JJ, Qiu DW. An insecticidal protein from Xenorhabdus budapestensis that results in prophenoloxidase activation in the wax moth, Galleria mellonella. J Invertebr Pathol. 2012;110:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Q, Cui J, Zhu Y, Wang G, Hu L, Long C, et al. A bacterial type III effector family uses the papain-like hydrolytic activity to arrest the host cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3716–3721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900212106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Hu X, Li Y, Ding X, Yang Q, Sun Y, Yu Z, Xia L, Hu S. XaxAB-like binary toxin from Photorhabdus luminescens exhibits both insecticidal activity and cytotoxicity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2014;350:48–56. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Table S1. List of oligonucleotides employed for cloning and sequencing of Photorhabdus toxin genes. Annealing temperature for each PCR reaction was 60°C.Figure S1. Agarose gel photographs showing the PCR amplified fragments of toxin genes, such as pirA (417 bp), tcaA (3288 bp), tccA (2898 bp) and tccC (3132 bp) from the genomic DNA of P. akhurstii strains IARI-SGMG3, IARI-SGGJ2, IARI-SGHR2 and IARI-SGMS1.Figure S2. SDS-PAGE analysis of P. akhurstii (IARI-SGMG3) toxins induced by 1 mM IPTG for 4 h in E. coli BL21 cells. Lanes: M—protein molecular weight marker, 1—uninduced BL21 cells harboring TcaA, 2—induced BL21 cells harboring TcaA, 3—uninduced BL21 cells harboring TccC, 4—induced BL21 cells harboring TccC, 5—uninduced BL21 cells harboring TccA, 6—induced BL21 cells harboring TccA, 7—uninduced BL21 cells harboring PirA, 8—induced BL21 cells harboring PirA. Arrows indicate the overexpression of target protein. The calculated molecular mass (using Expasy ProtParam tool; https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) of TcaA, TccC, TccA and PirA was 120, 111, 105 and 15 kDa, respectively. (PDF 366 kb)