Abstract

Background and aim

The role of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) in the management of liver metastasis is increasing, using ablative doses with the goal of local control and ultimately improving survival. The aim of this study is to evaluate our initial results regarding local control, overall survival and toxicity in patients with liver metastases treated with this technique, due to the lack of evidence reported in Latin America.

Materials/methods

We performed a retrospective chart review from November 2012 to June 2018 of 24 patients with 32 liver metastases. Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed for local control and overall survival. Clinical and prognostic factors were further analyzed by independent analysis. Median follow-up period was 22 months (range, 1–65 months).

Results

Median age was 62 years (range, 40–84 years). Colorectal carcinoma was the most common primary cancer. Overall 1-year and 2-years local control rates were 82% (95% Confidence Interval [CI], 70–98%) and 76.2% (95% CI, 45–90%), respectively. Median overall survival rate was 35 months (95%, CI 20.5–48 months). Overall 1-year and 2-year survival rates were 85.83% (95% CI, 64–99%) and 68% (95% CI, 45–84%), respectively. No acute or late grade 3 or 4 toxicity was observed during the follow-up period.

Conclusions

SBRT achieves excellent local control and overall survival rates with low toxicity in patients with liver metastases. Based on our literature review, our results are consistent with larger reports. Further randomized trials are required to compare with other local therapies.

Keywords: Liver metastases, Stereotactic body radiotherapy, CyberKnife

1. Background

Approximately 30–40% of all patients with solid tumors will develop liver metastases during the natural course of the disease.1 The most common primary site is colorectal carcinoma due to the direct drainage through the portal venous system. Other sources of liver metastases include the lung, breast, bladder, pancreas, head, neck and melanoma.2 Hepatic involvement can cause significant morbidity with pain, anorexia, ascites affecting health-related quality of life and increasing mortality.

Since Hellman and Weichselbaum changed the historical concept of metastatic disease as an incurable state proposing an intermediate stage called “oligo metastatic disease”, therapeutic approaches have changed dramatically from systemic and palliative to more aggressive local therapies.3,4

Surgical resection continuous to be the gold standard treatment for liver metastases with a 5-year survival rate of up to 30−60%.5,6 However, only 10–20% of these patients are amenable to resection due to comorbidities, unfavorable liver involvement, uncontrolled primary tumor or extrahepatic disease.7

Different techniques of minimally invasive therapies for liver metastases have been used in patients ineligible for surgery, including radiofrequency ablation (RFA), microwave ablation, transarterial chemo embolization (TACE) and cryotherapy. These techniques have shown promising results, but present multiple limitations and variable local control rates.8, 9, 10, 11

Over the past two decades, technological advances in the field of radiation treatment planning and delivery as well as the improvement in diagnostic imaging have provided the means of delivering high radical doses to the tumor while sparing normal tissue. Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has proven to achieve the goals of radiosurgery, long used for brain tumors, becoming an attractive technique for liver irradiation.

The liver has a radiobiologically parallel architecture model, with the liver acini as functional subunits.12 Risk of developing a complication depends on dose distribution throughout the whole organ rather than the maximum dose to a small area.13 Dose-limiting toxicity liver complex has been defined since the 1990s as radiation-induced liver disease (RILD). RILD presents as a clinical syndrome with ascites, hepatomegaly and elevated liver enzyme occurring approximately 4–8 weeks following radiation therapy.14 The mean liver dose associated with the development of RILD is 30−36 Gy (using conventional 2 Gy per fraction).15 Therefore, conventional radiotherapy has been limited to very selected cases in the palliative care scenario.

In contrast to conventional radiotherapy, SBRT can deliver highly conformal dose distribution with a rapid dose drop-off that offers the ability to spare large portions of the liver while allowing dose escalation, reducing the risk of RILD.16 Early studies have shown promising results, but this procedure must be performed cautiously given the challenges of organ motion and the low radiation tolerance of the surrounding tissue.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

2. Aim

Due to scarce Latin American literature, the purpose of this report is to analyze our initial results on the use of Cyberknife SBRT for liver metastases in patients that refuse or are not candidates for surgery and compare with previously published data.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study design

Using a retrospective cohort design, we reviewed charts of 24 patients with liver metastases of nine different primary sites treated with SBRT at tertiary referral center in Monterrey, México, from November 2012 to June 2018. All patients presented with locally progressive liver disease and refused or were not eligible for surgical resection due to tumor extension, location and/or patients’ comorbidities. Sufficient liver volume free of disease was a requirement to comply with tolerance (>700 cc receiving less than 15 Gy).

Collected data included gender, age, Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), primary site of the tumor, number and location of liver metastases (by segments), previous local treatment and dosimetry. Pretreatment evaluation included physical examination, imaging studies (Computed tomogram [CT], Magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], Positron Emission Tomography [PET/CT]) and laboratory tests including blood counts and liver enzymes.

3.2. Radiosurgery characteristics

All treatments were delivered using the CyberKnife Radiosurgery System (Accuray, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The patients had three solid gold fiducial markers (FM) placed percutaneously around the tumor by an interventional radiologist, 7–10 days before planning scans to rule out FM migration. A high-resolution contrast-enhanced CT of the liver was obtained for planning. After October 2017, MRI and PET/CT were fused with planning CT using the MIM System.

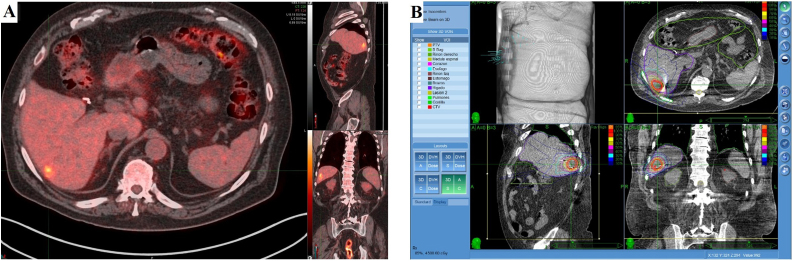

Target volumes were delineated by the radiation oncologist using all available imaging studies. The gross tumor volume (GTV) delineated as the edge of contrast enhancement and considered the same as clinical target volume (CTV). The planning target volume (PTV) defined as CTV plus a 3−5 mm margin. Dose planning was performed using the Multiplan Software (Accuray Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) with a non-isocentric and non-coplanar radiation delivery (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic PET/CT showing one hepatic lesion used for treatment planning (A). Treatment planning images with a non-isocentric and non-coplanar radiation delivery system. Prescribed dose of 45 Gy in three fractions (B).

The prescription dose and fractionation were decided following the published data and the preference of the treating physician according to radio-sensitivity of the primary tumor, tumor volume, location and distance from critical structures. To ensure delivery accuracy, all patients used real-time tumor tracking by Synchrony® Respiratory Motion Tracking System.

3.3. Follow-up

Daily follow-up was performed during treatment for treatment-related toxicity, every 2 weeks after SBRT and every 3–6 months thereafter until death or the date of closure of the study (June 2018). Evaluation included clinical examination, blood count, serum liver enzymes and diagnostic images (CT, MRI and/or PET).

Acute toxicity was scored according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTVAE) version 4.0 defined as adverse events occurring within 3–6 months after SBRT.23 Late toxicity was defined as toxicities occurring after 6 months to last follow-up using the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (RTOG/EORTC) criteria.24

3.4. Statistical methods

Baseline characteristics are presented as frequencies or median with interquartile range, based on the distribution of the data. Local Control (LC) rate was the primary endpoint; secondary endpoints included OS, acute and late toxicity. Death for any reason during the follow up period was considered to be an event for the overall survival.

The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 and PERCIST 1.0 were used to defined local control depending on the availability of PET.23,24 LC was defined as freedom from local progression by the RECISTS or PERSIST criteria.

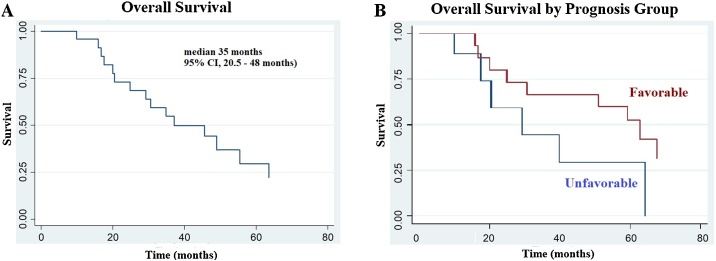

Primary tumor site was used as predictive of survival on both univariate and multivariate analysis. Primary tumors of colorectal, breast and lung cancer were associated with better survival compared with tumors that originated in other sites. We analyzed overall survival rate by primary tumor site, defined as favorable group including colorectal, breast and lung cancer, and unfavorable group with all six resting primary tumors. Since half of the patients were GI primary tumors, we added a secondary assessment of GI vs. non GI primaries in terms of overall survival results (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival outcomes. Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival after Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) for liver metastases (A). Survival rates by prognosis group: favorable and unfavorable primary tumor (B).

Kaplan–Meier method was used to evaluate LC and time to death and, subsequently, a comparison between favorable and unfavorable prognosis groups was made by the Wilcoxon log-rank test. Univariate cox proportional hazards regression model was used to evaluate for predictive factors associated with OS to calculate hazard ratios (HRs). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical test was based on a 2-sided significance level. Because of our small sample size, the risk of overfitting a regression model and no statistical significance on univariate models, we did not include a multivariate Cox proportional model. Data analysis was performed using STATA version 14.2 (StataCorp LCC, TX, USA).

4. Results

4.1. Patient characteristics

Twenty-four patients with thirty-two liver metastases were identified, with a median age of 62 years (Range, 40–84 years) and Karnofsky performance status >70 in 100%. The most frequent primary tumor site was colon-rectal (50%), breast (17%), head and neck (8%) and gastric cancer (8%). Sixteen patients were diagnosed with oligometastatic disease (≤ 5 metastatic tumors) and only one patient received prior embolization. Duration between embolization and SBRT was 4 months.

The most common regimen used was 45 Gy in 3 fractions (BED = 112.5 Gy10, EQD2 = 94 Gy) with an interval interfraction of 24 h. Tumor volume ranged from 2.4 to 115 cc (median of 21.5 cc). Treatment volumes were prescribed to a medium 82% isodose line (range, 72–93%). All patients completed their planned course of SBRT. Follow up information was available for every patient with a median follow-up period of 22 months (range, 1–65 months). Nine patients were alive at the time of the analysis. Patient’s and treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients and treatment characteristics.

| Characteristics | No. patients (%) | Median (range) |

|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 24 | |

| Male | 13 (54) | |

| Female | 11 (46) | |

| Age (years) | 62 (40–84) | |

| KPS | 80 (70–100) | |

| Primary site | ||

| Colorectal | 12 (50) | |

| Breast | 4 (17) | |

| Head and neck | 2 (8) | |

| Gastric | 2 (8) | |

| Others | 4 (17) | |

| Oligometastasic disease | 16 (67) | |

| Prior embolization | 1 (4) | |

| No. liver metastases | 32 | |

| Location (by segment) | ||

| III | 3 (9) | |

| IV | 3 (9) | |

| V | 3 (9) | |

| VI | 8 (25) | |

| VII | 5 (16) | |

| VIII | 10 (32) | |

| Tumor volume (cc) | 21.5 ( 2.4–115.9 ) | |

| Dose (Gy) | 36 ( 30–45 ) | |

| No. fractions | 3 ( 3–5 ) |

KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status.

4.2. Local control

Overall, the 1-year and 2-year local control rates were 82% (95%, CI 70–98%) and 76.2% (95% CI, 45–90%), respectively. Local recurrence was documented in 6 lesions (18.75%), during the follow up period. With 1102 months of time at risk, the incidence rate of local recurrence was 11.6%.

4.3. Overall survival

Median overall survival rate was 35 months (95% CI, 20.5–48 months). Overall, 1-year and 2-year survival rates were 85.83% (95% CI, 64–99%) and 68% (95% CI, 45–84%), respectively. In a univariate survival analysis, favorable prognosis group was associated with a significantly better overall survival (Fig. 1A–B) and with a median survival of 52.8 months compared to 34.5 months in the unfavorable group (log rank test p = 0.09). In a secondary analysis of histology as a predictor of overall survival, GI primary group was associated with significantly better results with a median survival of 59.1 months compared to 37.4 months in the non-GI primary group (log rank test p = 0.06).

Results of univariate Cox proportional hazard model are shown in Table 2. Age ≥70 years was significantly associated with increased mortality (HR 5.25, p 0.011). Because of our small sample size, the risk of overfitting a regression model and no statistical significance on univariate model, we did not include a multivariate Cox proportional model.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with overall survival.

| Variable | Univariate Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ≥70 y | 5.25 | 1.47−18.7 | 0.011 |

| Gender | Male | 2.13 | 0.74−6.2 | 0.162 |

| Karnofsky | ≥90 | 0.37 | 0.13−1.07 | 0.067 |

| Favorable Group | Colorectal, breast and lung cancer | 0.41 | 0.14−1.21 | 0.09 |

| Histology | GI primary | 0.39 | 0.8−1.09 | 0.06 |

| Oligometastatic disease | 1.75 | 0.59−5.11 | 0.306 | |

| Number lesions | ≥2 lesions | 1.54 | 0.33−7.09 | 0.58 |

| Tumor volume | >21 cc | 1.94 | 0.66 | 5.71 |

CI: Confidence Interval.

The plot of Schoenfeld residuals produced a random pattern (global test p = 0.9569) suggesting that the residuals of the model do not change over time and the proportional hazard assumption was reasonable.

4.4. Toxicity

Treatment was well tolerated with none of the patients with grade 3 or higher toxicity (Table 3). The most common acute clinical toxicities were fatigue (50%), nausea (25%), hepatic pain (16%) and vomiting (12%). Liver enzymes were only mildly elevated and restored to normal levels one month after treatment. Long-term side effects included fatigue (17%) and abdominal pain (12%). No radiation-induced liver disease was observed.

Table 3.

Acute and long-term toxicity.

| Adverse event | Grade 1 (%) | Grade 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Acute | ||

| Nausea | 5 (21%) | 1 (4%) |

| Vomiting | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Fatigue | 10 (42%) | 2 (8%) |

| Hepatic pain | 2 (8%) | 2 (8%) |

| AST increased | 4 (17%) | 1 (4%) |

| ALT increased | 3 (13%) | 1 (4%) |

| Anemia | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Long-term | ||

| Fatigue | 3 (13%) | 1 (4%) |

| Hepatic pain | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) |

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: Alanine aminotransferase.

5. Discussion

The use of SBRT for extracranial tumors has been developed at the Swedish Karolinska University since 1995.17 Currently, the role of SBRT from palliative care to radical intent has changed with the new technological advances and clinical applications of radiobiology, making this technique widely used as a treatment option for liver tumors.

Most published data about SBRT for liver tumors have contained both different primary liver metastases and hepatocellular carcinoma. Studies that only include liver metastases are scarce and their results range widely due to patient selection, radiation modality and lack of randomized clinical trials. Retrospective and prospective phase I/II studies have reported the efficacy and safety of different SBRT regimens for liver metastases. We reviewed the heterogeneous published reports in Table 4, Table 5 with regard to patients’ characteristics, fractionation, dose, toxicity and outcome in terms of OS and LC.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22,25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 Although no randomized data have been reported, an international multicenter phase III trial comparing RFA with SBRT for liver metastases has pending results (Radiofrequency Ablation Versus Stereotactic Radiotherapy in Colorectal Liver Metastases, RAS).39

Table 4.

Review of literature for retrospective studies for SBRT for liver metastases.

| Author (year) | Patients | Primary | Dose/fractionation | Platform | Toxicity (cases) | Local control | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blomgren (1995)17 | 31 (14) | Mixed | 7.7–45 Gy/ 1−4 | Linac | 2 haemorrhagic gastritis | 2-year LC 71.2% | NR |

| Sato (1998)18 | 4 | Mixed | 50−60 Gy/ 5−10 | Linac | 5% Grade 3−4 toxicity | 100% crude LC | NR |

| Wulf (2001)19 | 20 | Mixed | 30 Gy/ 3 | Linac | 29% Grade 1−2 | 1-year LC 76% | 1-year OS 71% |

| No Grade 3−5 | 2-year LC 61% | 2-year OS 43% | |||||

| Wulf (2006)20 | 44 | Mixed | 26−37.5 Gy/ 1−3 | Linac | No grade 2−4 toxicity | 1-year LC 86% | 1-year OS 72% |

| 2-year LC 58% | 2-years OS 32% | ||||||

| Katz (2007)21 | 69 | Mixed | 30−55 Gy/ 5−15 | Linac | No grade 3−4 toxicity | 10-month LC 76% | Median 14.5 months |

| 20-month LC 57% | |||||||

| van der Pool (2010)25 | 20 | CRC | 30−37.5 Gy/ 3 | Linac | Grade 3 Liver enzyme (2) | 1-year LC 100% | Median 34 months |

| and rib fracture (1) | 2-year LC 74% | ||||||

| Aitken (2014)26 | 34 | Mixed | 30−60 Gy/10 | Linac | Grade 3 Liver enzyme (1) | 1-year LC 65% | Median 14.5 months |

| 2-year LC 74% | |||||||

| Yuan (2014)27 | 57 | Mixed | 39−54 Gy/ 3−7 | CK | No grade ≥3 toxicity | 1-year LC 94.4% | Median 37.5 months |

| 2-year LC 89.7% | |||||||

| Yamashita (2014)28 | 139 (51) | Mixed | 30−60 Gy/ 3−10 | Linac | 7% grade 2−4 | 1-year LC 75% | 2-years OS 72% |

| 2-years LC 65% | |||||||

| Amendola (2017)29 | 27 | Mixed | 36−60 Gy/3 | Linac | 18% Grade 1 | 12 patients had LC | Median 9 months |

| 3% Grade 2 | |||||||

| Mahadevan (2018)30 | 427 | Mixed | 12−60 Gy / 1−5 | CK | NR | 1-year LC 84% | 1-year OS 74% |

| 2-years LC 72% | 2-year OS 49% | ||||||

| Current study | 24 | Mixed | 30−45 Gy / 3 | CK | No grade 3−4 toxicity | 1-year LC 82% | 1-years OS 85% |

| 2-years LC 76.2% | 2-years OS 68% |

NR: not reported; LC: local control; OS: overall survival; CRC: colorectal carcinoma; CK: Cyberknife System.

Table 5.

Review of literature for prostective studies for SBRT for liver metastases.

| Author (year) | Design | Patients | Primary | Dose/fractionation | Platform | Toxicity (cases) | Local control | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herfarth (2001)22 | Phase I-II | 35 | NR | 14−26 Gy/ 1 | Linac | No serious toxicity | 1-year LC 71% | 1-year OS 72% |

| 18-mo LC 67% | ||||||||

| Schefter (2005)31 | Phase I | 18 | Mixed | 36−60 Gy/ 3 | Linac | No patients experience | NR | NR |

| dose-limiting toxicity | ||||||||

| Hoyer (2006)32 | Phase II | 64 (44) | CRC | 45 Gy/ 3 | Linac | 1 liver failure | 1-year LC 95% | 1-year OS 67% |

| 2 severe late GI | 2-years LC 79% | 2-years OS 38% | ||||||

| Mendez Romero (2006)33 | Phase I-II | 25 (17) | Mixed | 30−37.5 Gy/ 3 | Linac | Grade 3 liver toxicity (2) | 2-years LC 86% | 2-years OS 62% |

| Lee (2009)34 | Phase I-II | 68 | Mixed | 27.7−60 Gy/ 6 | Linac | 10% acute Grade 3−4 | 1-year LC 71% | Median 17.6 months |

| Rusthoven (2009)35 | Phase I-II | 47 | Mixed | 36−60 Gy/ 3 | Linac | <2% Grade 3−4 late toxicity | 1-year LC 95% | Median 20.5 months |

| 2-years LC 92% | ||||||||

| Ambrosino (2009)36 | Prospective | 27 | Mixed | 25−60 Gy /3 | CK | No serious toxicity | Crude LC 74% | NR |

| Goodman (2010)37 | Phase I | 26 (19) | Mixed | 18−30 Gy / 1 | Linac/CK | Grade 2 late toxicity (4) | 1-year LF 23% | 1-year OS 61.8% |

| 2-years OS 49% | ||||||||

| Scorsetti (2013)38 | Phase II | 61 | Mixed | 75 Gy / 3 | Linac | Grade 3 late toxicity (1) | 1-year LC 94% | 1-year OS 84% |

NR: not reported; LC: local control; OS: overall survival; CRC: colorectal carcinoma; CK: Cyberknife System.

Early experiences with SBRT for primary and metastatic liver tumors demonstrated 40% tumor reduction and 32% complete response by imaging studies, with a 5.3% of local failures. Unfortunately, the mean survival time was only 13.4 months, with the predominant cause of death related to progressive liver cirrhosis and extrahepatic disease.17 Herfarth et al. reported the first prospective phase I/II dose escalation trial (dose from 14 Gy to 26 Gy) with no serious toxicity. Local control rates reported up to 71% and 67% (12- and 18 months, respectively) with a statistically significant difference in Kaplan–Meier LC between fractionation schemes of 14−20 Gy vs. 22−26 Gy in a single session.22 Mendez Romero and colleagues utilized 12.5 Gy in three fractions or 25 Gy in five fractions schemes, with 1- and 2-year local control rates in metastatic patients of 100% and 86%, respectively. Treatment-related toxicity included two patients with acute grade 3 toxicity.33 Stanford University Medical Center reported a phase I dose escalation study, with a single fraction from 18 to 30 Gy in 4-Gy increments. There was only a grade two acute and late toxicity reported with a 1-year cumulative incidence of local control for all patients of 77%.37

When we began using SBRT for liver metastases in 2012, the results of single-fraction appeared promising, but there were still questions about a potential toxicity of ultra-high dose radiotherapy in the abdomen. Our program was initiated using a 12.5 Gy in three fractions scheme based on these studies (six patients). However, as our experience and the literature matured, we increased dose to 45 Gy in three fractions to achieve a BED of 112 Gy10 reported to be an adequate dose for higher local control rates (BED>100Gy10, EQD2 = 90). Hoyer et al. reported their results using the same scheme of 45 Gy in three fractions with a 2-year local control of 79% and 1-year overall survival of 67% in patients with colorectal liver metastases.32 Our data compare favorably with these results, with a 1-year local control rate of 82% and 1-year overall survival of up to 85%. Survival results are probably impacted by systemic chemotherapy and immunotherapy not taken into account in this analysis.

There are several schedules now used for SBRT in liver metastases, doses range from 30 to 60 Gy in three fractions. Schefter performed a phase I trial dose escalation of 60 Gy in three fractions without reaching maximum tolerated dose (MTD) with no patients experiencing dose-limiting toxicity. These investigators defined a dose limiting of 700 cc of normal liver should receive less than 15 Gy to avoid liver toxicities.31 An observation of dose-control relationship after SBRT for liver tumors performed by the University of Colorado reported that both increased nominal dose and equivalent uniform dose improved local control.40 Lee performed a phase I-II study with doses based on tissue complication probability (NTCP)-calculated risk of RILD and Veff irradiated. They reported no RILD or higher toxicity and commented that the use of Veff led to an overestimation of toxicity risk.34 Scorsetti in Milan reported a phase II trial with 61 patients treated with 75 Gy in three fractions. The overall local control rated was 95% and 1- and 2-year overall survival of up to 80% and 70%, respectively.38 Although these series reported no patients with RILD or grade 4 toxicities, the radiobiology effects for ultra-high doses have been not fully understood and we should be cautioned that the conversion of SBRT dose schedules to equivalent doses by the use of the linear-quadratic model should be done with awareness of substantial uncertainty.

Severe toxicity related to SBRT is uncommon. The incidence of grade ≥3 toxicity rate has been reported of 1–10% and only 1% for RILD.41 There has been one reported death from hepatic failure after SBRT, possibly related to tumor volume and 60% of the liver receiving >10 Gy with a median total liver dose of 14.4 Gy31 and one death with Childs B cirrhosis secondary to liver decompensation.33 No RILD cases have been reported using the compliance of 700c of uninvolved liver receiving ≤15 Gy. The most common low-grade toxicities are usually related to lesions closed to the duodenum, bowel, skin and ribs. We do not report any grade ≥3 acute or late toxicity.

Most of the reports described mixed primary sites, mainly from colorectal, breast and lung cancer. Only one retrospective and one prospective study focus on a single primary tumor (colorectal) using a three-fraction scheme (dose range, 30–45 Gy). In these particular reports, LC rates were reported to be up to 100−95% and 79−74%, 1- and 2-year, respectively.25,32 We evaluated the impact of primary tumor on OS and LC. Due to our limited sample size, to better assess the impact of histology on OS, we performed the analysis based on two different histology groups (favorable/unfavorable as described above) as reported previously.27,29,35 Rusthoven et al. demonstrated improved median overall survival after SBRT for liver metastases from favorable primary tumors compared with that for unfavorable primary sites.35 Furthermore, multivariate COX regression analysis identified that the primary tumor was the only independent prognostic factor that predicted overall survival in patients with liver metastases. Our results confirm previously published data that patients in the favorable histology subgroup have a longer overall survival (52.8 vs. 34.5 months, p = 0.09). As a secondary analysis we only compared GI vs. non-GI primary tumor, with a significantly better overall survival in the GI group (59.1 vs. 37.4 months, p = 0.06). In contrast, there are some reports that found no significant difference in OS between histology groups.42 The discrepancy of these results is still unclear, but may be related to systemic chemotherapy and new targeted cancer therapies.

Despite the small number of patients and relatively short follow-up period we can state that our results are in line with world-wide reports of SBRT in liver metastases. To our knowledge, no other information from Latin America has been published. Further evaluation with more patients and longer follow-up is needed to confirm these results.

6. Conclusion

SBRT is an effective and safe therapy in the management of liver metastases. Based on our literature review, our results are consistent with larger reports. This data encourages us to enroll patients for this treatment when appropriate. Further randomized trials are required to compare with other local therapies.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

References

- 1.Blaker H., Hoffman W.J., Theuer D., Otto H.F. Pathohistological findings in liver metastases. Radiologe. 2001;41:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s001170050921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grover A., Alexander H.R., Jr The past decade of experience with isolated hepatic perfusion. Oncologist. 2004;9(6):653–664. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-6-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hellman S., Weichselbaum R.R. Oligometastases. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):8–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weichselbaum R.R., Hellman S. Oligometastases revisted. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(6):378–382. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choti M.A., Sitzman J.V., Tiburi M.F. Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2002;235(6):759–766. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomlinson J.S., Jarnagin W.R., DeMatteo R.P., Fog Y. Actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases defines cure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4575–4580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small R., Lubezky N., Ben-Haim M. Current controversies in the surgical management of colorectal cancer metastases to the liver. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007;9(10):742–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrean S., Hering J., Saied A., Helton W.S., Espat N.J. Radiofrequency ablation of primary and metastatic liver tumors: a critical review of the literature. Am J Surg. 2008;195(4):508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solbaiti L., Livraghi T., Golberg S.N. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: long-term results in 117 patients. Radiology. 2001;221(1):159–166. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2211001624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groeschl R.T., Pilgrim C.H., Hanna E.M. Microwave ablation for hepatic malignancies: a multinstitutional analysis. Ann Surg. 2014;259(6):1195–1200. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volg T.J., Zangos S., Eichler K., Yakaoub D., Nabil M. Colorectal liver metastases: regional chemotherapy via transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and hepatic chemoperfusion: an update. Eur Radiol. 2007;17(4):1025–1034. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson A., Ten Haken R.K., Robertson J.M. Analysis of clinical complication data for radiation hepatitis using a parallel architecture model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:883–891. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalogeridi M.A., Zyngogioanni A., Kyrigias G. Role of radiotherapy in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(1):101–112. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence T.S., Robertson J.M., Anscher M.S. Hepatic toxicity resulting from cancer treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1237–1248. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00418-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson L.A., Normolle D., Balter J.M. Analysis of radiationinduced liver disease using the Lyman NTCP model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:810–812. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02846-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hara W., Soltys S.G., Gibbs I.C. CyberKnife robotic radiosurgery system for tumor treatment. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7(11):1507–1515. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.11.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blomgren H., Lax I., Näslund I., Svanström R. Stereotactic high dose fraction radiation therapy of extracranial tumors using an accelerator: clinical experience of the first thirty-one patients. Acta Oncol. 1995;34:861–870. doi: 10.3109/02841869509127197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato M., Uematsu M., Yamamoto F., Shioda A., Tahara K., Fukui T. Feasibility of frameless stereotactic high-dose radiation therapy for primary or metastatic liver cancer. J Radiosurg. 1998;1:233–238. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wulf J., Hadinger U., Oppitz U. Stereotactic radiotherapy of targets in the lung and liver. Strahlenther Onkol. 2001;177(12):645–655. doi: 10.1007/pl00002379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wulf J., Guckenberger M., Haedinger U. Stereotactic radiotherapy of primary liver cancer and hepatic metastases. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:838–847. doi: 10.1080/02841860600904821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz A.W., Carey-Sampson M., Muhs A.G., Milano M.T., Schell M.C., Okunieff P. Hypofractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for limited hepatic metastases. In J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67(3):793–798. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herfarth K.K., Debus J., Wannenmacher M. Stereotactic single-dose radiation therapy of liver tumors: results of a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:164–170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health . Department of Health and Human Services; MD: 2009. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE), version 4.0. Bethesda. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox J., Stetz J., Pajak T. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (RTOG/EORTC) criteria. Int. J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1341–1346. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00060-C. Mar 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Pool A.E.M., Méndez Romero A., Wunderink W. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2010;97:377–382. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aitken K.L., Tait D.M., Nutting C.M., Khabra K., Hawkins M.A. Risk-adapted strategy partial liver irradiation for the treatment of large volume metastatic liver disease. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:702–706. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.862595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan Z.Y., Meng M.B., Liu C.L., Wang H.H. Stereotactic body radiation therapy using the CyberKnife System for patients with liver metastases. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:915–923. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S58409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamashita H., Onishi H., Matsumoto Y. Local effect of stereotactic body radiohterapy for primary and metastatic tumors in 130 Japanese patients. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:112. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-9-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amendola B., Amendola M., Blanco J.M., Perez N., Wu X. Radiosurgery for liver metastases. A single institution experience. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2017;22:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahadevan A., Blanck I., Lanciano R., Peddada A. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) for liver metastases — clinical outcomes from the international multi-institutional RSSearch Patient Registry. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13014-018-0969-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schefter T.E., Kavanagh B.D., Timmerman R.D., Cardenes H.R., Baron A., Gaspar L.E. A phase I trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for liver metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:1371–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoyer M., Roed H., Traberg H.A. Phase II study on stereotactic body radiotherapy of colorectal metastases. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:823–830. doi: 10.1080/02841860600904854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendez Romero A., Wunderink W., Hussain S.M. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for primary and metastatic liver tumors: a single Institution phase I–II study. Acta Oncol. 2006;45(7):831–837. doi: 10.1080/02841860600897934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee M.T., Kim J.J., Dinniwell R. Phase I study of individualized stereotactic body radiotherapy of liver metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1585–1591. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rusthoven K.E., Kavanagh B.D., Cardenes H. Multiinstitutional phase I/II trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1572–1578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ambrosino G., Polistina F., Constatin G. Image-guided robotic stereotactic radiosurgery for unresectable liver metastases: preliminary results. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3381–3384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodman K.A., Weigner E.A., Maturen K.E. Dose-escalation study of single-fraction stereotactic body radiotherapy for liver malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78(2):486–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scorsetti M., Arcangeli S., Tozzi A. Is stereotactic body radiation therapy an atrractive option for unsresectable liver metastases? A preliminary report from a phase 2 trial. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 2013;86(2):336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.M. Hoyer, A. Méndez, E. van der Linden, CIRRO — Danish Center for International Research in Radiation. Oncology. Høyer M, The International Liver Tumor Group RAS-trial. Radiofrequency ablation versus stereotactic body radiation therapy for colorectal liver metastases: a randomized trial. Available from: http://www.cirro.dk/assets/files/CIRRO-IP060109-levermetastaser.pdf.

- 40.McCammon R., Schefter T.E., Gaspar L.E., Zaemisch R., Gravdahl D., Kavanagh B. Observation of a dose-control relationship for lung and liver tumors after stereotactic body radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fundowicz Magdalena Adamczyk M., Kolodziej-Dybás A. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver metastasis — the linac based Greated Poland Cancer Centre practice. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2017;22:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stintzing S., Hoffmann R.T., Heinemann V. Radiosurgery of liver tumors: value of robotic radiosurgical devise to treat liver tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2877–2883. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]