Abstract

The coordination of the hypoxic response is attributed, in part, to hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (Hif-1α), a regulator of hypoxia-induced transcription. After the teleost-specific genome duplication, most teleost fishes lost the duplicate copy of Hif-1α, except species in the cyprinid lineage that retained both paralogues of Hif-1α (Hif1aa and Hif1ab). Little is known about the contribution of Hif-1α, and specifically of each paralogue, to hypoxia tolerance. Here, we examined hypoxia tolerance in wild-type (Hif1aa+/+ab+/+) and Hif-1α knockout lines (Hif1aa−/−; Hif1ab−/−; Hif1aa−/−ab−/−) of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Critical O2 tension (Pcrit; the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) at which O2 consumption can no longer be maintained) and time to loss of equilibrium (LOE), two indices of hypoxia tolerance, were assessed in larvae and adults. Knockout of both paralogues significantly increased Pcrit (decreased hypoxia tolerance) in larval fish. Prior exposure of larvae to hypoxia decreased Pcrit in wild-type fish, an effect mediated by the Hif1aa paralogue. In adults, individuals with a knockout of either paralogue exhibited significantly decreased time to LOE but no difference in Pcrit. Together, these results demonstrate that in zebrafish, tolerance to hypoxia and improved hypoxia tolerance after pre-exposure to hypoxia (pre-conditioning) are mediated, at least in part, by Hif-1α.

Keywords: hypoxia-inducible factor, hypoxia tolerance, development, zebrafish, loss of equilibrium, critical oxygen tension

1. Introduction

Since its discovery as a nuclear factor that increases transcription of the erythropoietin gene in hypoxia [1], hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) has been the focus of intense research because of its importance as a global regulator of the transcriptional response of vertebrates to hypoxia [2]. A heterodimeric protein, HIF is composed of an O2− regulated HIF-α subunit and a constitutively expressed HIF-β subunit. In the presence of O2, HIF-α is rapidly degraded, but as O2 becomes limiting in a cell, HIF-α rapidly accumulates, enters the nucleus, dimerizes with HIF-β and then binds to hypoxia-responsive elements of target genes to stimulate transcription. In mammals, HIF is known to regulate numerous and diverse processes including erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, energy metabolism, cell proliferation, apoptosis and embryonic development [3–6].

For species that naturally experience chronic or intermittent hypoxia, it is thought that functional divergence in HIF-α from other vertebrates may underlie enhanced hypoxic tolerance [7]. Studies on high-altitude mammals have identified the HIF-prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) pathway as being under selection, contributing to hypoxia tolerance and high-altitude phenotype in Tibetan human populations [8] and Tibetan pigs [9]. Because aquatic habitats are particularly vulnerable to hypoxia, O2 is considered an important driver in the evolution of fishes [10], and variations in the Hif (nomenclature switch: for protein abbreviation in mammals all letters are capitalized while in fishes only the first letter is capitalized) pathway may have contributed to adaptations to hypoxia. An examination of nine species of fishes found no clear evidence of divergence in protein-coding sequence of Hif-1α with respect to tolerance to hypoxia [11]. However, signatures of positive selection were identified in Hif-1α of African lungfish (Protopterus annectens) [12] and relaxed negative selection and greater functional divergence in teleost Hif-1α as compared to the mammalian HIF-1α was attributed to the greater variability of O2 in the aquatic environment [7,13].

A whole-genome duplication event at the base of the teleost fish lineage probably played an important role in the diversification and radiation of teleost fishes [14]. The genome duplication generated two copies each of the three hif-α genes, hif-1α, hif-2α and hif-3α genes (hif1aa and hif1ab, hif2aa and hif2ab, hif3aa and hif3ab; previously the paralogues were identified as hif1A and hif1B, hif2A hif2B, hif3A and hif3B, respectively [15]) that were retained only in the cyprinid lineage that includes zebrafish (Danio rerio) [16]. Transcription patterns during development and in response to hypoxia in zebrafish possibly demonstrate that Hif paralogues may have undergone sub-functionalization, a process where the functions of the ancestral gene are divided between the paralogues [16,17]. Retention of the duplicated genes of Hif may have provided the increased adaptive potential to respond to hypoxia in cyprinids [16], yet our understanding of the specific roles and the extent of functional divergence of Hif paralogues remain limited.

In mammals, loss of PHD has been shown to increase hypoxia tolerance in mice [18], however, a direct assessment of HIF-1α in contributing to hypoxia tolerance has not been possible because HIF-1α knockout results in embryonic lethality [19]. By contrast to mammals, in zebrafish, a tractable species for gene editing, it is possible to generate a viable mutant with knockout of both paralogues of Hif-1α (Hif1aa−/−ab−/−) [20]. In this study, we examined the role of Hif-1α paralogues on conferring hypoxia tolerance in zebrafish, by comparing hypoxic responses in wild-types and knockouts previously generated by Gerri et al. [20]. Several methods are used routinely to assess hypoxia tolerance. These methods include: (i) determination of critical O2 tension (Pcrit; the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) at which an animal can no longer sustain O2 consumption (ṀO2)), and (ii) time to loss of equilibrium (LOE). Because each method may be influenced, at least in part, by different underlying physiological mechanisms, it is preferable to use multiple methods when assessing hypoxia tolerance [21]. Thus, in the current study, time to LOE and Pcrit were quantified in adult zebrafish and Pcrit was quantified in larval zebrafish experiencing loss of either Hif-1α paralogue (Hif1aa−/− or Hif1ab−/−) and of both (double knockout; Hif1aa−/−ab−/−). Additionally, zebrafish larvae were raised under hypoxic conditions to assess whether pre-exposure lowered Pcrit and whether such a pre-conditioning effect was mediated by Hif-1α. While both metrics of hypoxia tolerance were quantified in adult zebrafish, in larval zebrafish it was not possible to assess time to LOE owing to the size of the individuals and their level of activity. We predicted that a loss of Hif-1α would impair hypoxia tolerance in larval and adult zebrafish and that Hif-1α plays a role in pre-conditioning to hypoxia in zebrafish larvae. The evolutionary trajectory of the two paralogues of Hif-1α following duplication, mainly whether there has been sub-functionalization, neo-functionalization (paralogues acquire novel functions) or no change of function of either paralogue as compared to that of the ancestral gene, is unknown. However, some evidence points to differences in the effect of Hif-1α paralogues on the hypoxic control of breathing, suggesting divergence of function between the two paralogues [22]. As such, if the Hif-1α paralogues have diverged in function, we predicted that there would be a difference in the contribution of each paralogue to hypoxia tolerance and pre-conditioning to hypoxia.

2. Material and methods

(a). Experimental animals

Adult zebrafish, D. rerio, were housed in 10 l acrylic tanks in recirculating aquatic housing systems (Aquatic Habitats, Apopka, USA) at the University of Ottawa aquatic care facility. The fish were maintained at 28°C on a 14 h : 10 h light : dark cycle and fed to satiation twice a day. Genotypes tested for hypoxia tolerance in this study were wild-type zebrafish from in-house stock at the University of Ottawa, Hif1aa−/− and Hif1aa−/−ab−/− generated via TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 technologies [20] and Hif1ab−/− generated via CRISPR/Cas9 (Joanna Yeh Laboratory, Harvard Medical School). Zebrafish embryos of each genotype were obtained from controlled breeding events. The day before breeding, one male and two female fish were placed into a 2 l breeding tank and separated by a clear barrier. The following morning, water was changed and the barrier was removed allowing fish to breed. Embryos were collected and raised in 50 ml Petri dishes (density: 40 embryos per dish) containing dechloraminated city of Ottawa tap water and 0.05% methylene blue in an incubator maintained at 28°C. Water in the Petri dishes was changed daily. All procedures for animal use and experimentation were carried out in compliance with the University of Ottawa Animal Care and Veterinary Service guidelines under protocol BL-1700 and adhered to the recommendations for animal use provided by the Canadian Council for Animal Care.

(b). Critical O2 tension (Pcrit)

Larvae of each genotype were raised to 7 days post fertilization (dpf) under 21 kPa (normoxia) water PO2 tensions. A separate group of larvae of each genotype were raised from 4 to 7 dpf at 12 kPa (termed mild, long duration hypoxia), while a third group of larvae of all genotypes were raised from 6 to 7 dpf at 4 kPa (termed severe, short duration hypoxia). Approximately 40 individual larvae were confined in submerged cylindrical chambers with mesh bottoms and tops to allow for mixing (submersible pump) of water within a 30 l glass tank. The hypoxic water being supplied to the 30 l tank was derived from the outflow of the water equilibration column, which was gassed with appropriate mixtures of air and N2 to yield the PO2's of 12 and 4 kPa. A custom gas mixer fabricated at the University of Ottawa provided the gas mixtures and O2 levels were monitored with a hand held O2 metre (Handy Polariz O2, OxyGuard, Birkerod, Denmark).

At 7 dpf, approximately 15 individuals were transferred to 2 ml glass chambers (Loligo Systems, Viborg, Denmark) and placed in a temperature controlled water bath set at 28°C. A stir bar separated from the larvae by stainless steel mesh mixed water in the chamber during the closed system respirometry trial. The larvae were allowed to recover for 30 min during which time half the volume of the chamber was replaced every 10 min to ensure water PO2 remained at normoxic levels. At the start of the trial, the chambers were sealed and water PO2 was measured continuously using fibre optic O2 probes (FOXY AL-300, Ocean Optics, Dunedin, USA). The trial was terminated when water PO2 reached a minimum. Wet weight of the zebrafish larvae was determined by methods described in [23].

In adults, O2 consumption (ṀO2) at 28°C was measured using closed system respirometry. Individual fish were placed into 15.6 ml glass chambers fitted with O2 sensor spots (Loligo Systems, Viborg, Denmark) and flushed continuously with water from a 20 l recirculating tank gassed with air and allowed to recover for 24 h. At the beginning of the trial, flush pumps were turned off while recirculating pumps continued to adequately mix water throughout the trial. Water PO2 was monitored continuously and recorded using AutoResp (Loligo Systems, Viborg, Denmark) and a trial was terminated when water PO2 reached a minimum (roughly 150 min).

The slope of water PO2 versus time (binned in 3 min intervals) was used to calculate ṀO2 in larval and zebrafish for each genotype. The solubility coefficient of O2 in freshwater at 28°C [24] was used to convert water PO2 to O2 concentration. The inflection point, representing Pcrit, was determined from a plot of ṀO2 versus water PO2 with a ‘broken-stick’ or segmented linear regression (BSR) [25] using REGRESS software (www.wfu.edu/~mudayja/software/o2.exe) for each trial. A linear regression of ṀO2 versus PO2 at low PO2 was fitted to determine when the ṀO2 equalled routine ṀO2, providing an alternative estimate of Pcrit (LLO) [26]. Routine ṀO2 was determined by averaging values above 12 kPa, the water PO2 above which 7 dpf larvae and adult zebrafish do not hyperventilate [27,28].

(c). Time to loss of equilibrium

To determine time to LOE, adult individuals were placed into 2 l polycarbonate tanks and allowed to recover overnight, using a protocol similar to that conducted on Fundulus grandis [29] and various species of sculpin [30]. During recovery, tanks were supplied continuously with 28°C flow-through normoxic water (PO2 = 21 kPa). Zebrafish are known to perform aquatic surface respiration during hypoxia [31] and thus a perforated lid was placed 1 cm below the surface of the water to prevent fish from accessing the surface during hypoxia trials. A small submersible pump was placed into each tank to ensure adequate mixing of O2. After a 24 h recovery period, hypoxic flow-through water was introduced into the tanks and desired water PO2 was reached within 30 min. Hypoxic conditions were achieved by passing water through an equilibration column bubbled with appropriate mixtures of air and N2 to reach water PO2 of either 1.6 or 2.1 kPa. Sheets of bubble wrap were placed on top of the water to limit O2 diffusion from air into the water. Water O2 levels were monitored with a hand held O2 metre (Handy Polariz O2, OxyGuard, Birkerod, Denmark) every minute for the first 30 min. Once the set hypoxic level was reached, the O2 levels stabilized and water O2 was monitored every 10 min.

Two trials with each tank housing a different genotype were conducted simultaneously. Fish behaviour was monitored continuously throughout the trials and the time required to lose equilibrium was recorded for each individual (n = 7–8 individuals per tank). A fish was considered to have lost equilibrium after a failure to right itself for at least 5 s. The experiment was terminated at 300 min and individuals (in all instances wild-type fish) that had not lost equilibrium were given a score of 300 min. As the primary goal of the time to LOE experiment was a comparison among genotypes, we did not feel it was necessary to go beyond 300 min because individuals with loss of either or both paralogues of Hif-1α lost equilibrium well before 300 min. Sex ratios (approx. 50%) and mass of individuals were consistent across genotypes (wild-type: 0.398 ± 0.016 g, Hif1ab−/−: 0.300 ± 0.022 g, Hif1aa−/−: 0.384 ± 0.020 g and Hif1aa−/−ab−/−: 0.364 ± 0.023 g). Time to LOE was not measured in larval fish owing to difficulty of determining when a fish had lost equilibrium.

(d). Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in R (https://www.R-project.org/). The effects of genotype and rearing conditions on Pcrit and on ṀO2 in larval zebrafish were tested using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in the car package [32]. Tukey's post hoc test was performed if significance was detected. Normality (Shapiro–Wilk, Q–Q plot) and equal variance (Bartlett's) tests were performed to validate the assumptions of the ANOVA.

The effect of genotype on LOE, on Pcrit and on ṀO2 in adult zebrafish was tested using one-way ANOVA. If normality or equal variance criteria were not met and the data could not be transformed, a Kruskal–Wallis test by ranks ANOVA was used followed by Dunn's post hoc test, using the PMCMR package [33]. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

(a). Larvae

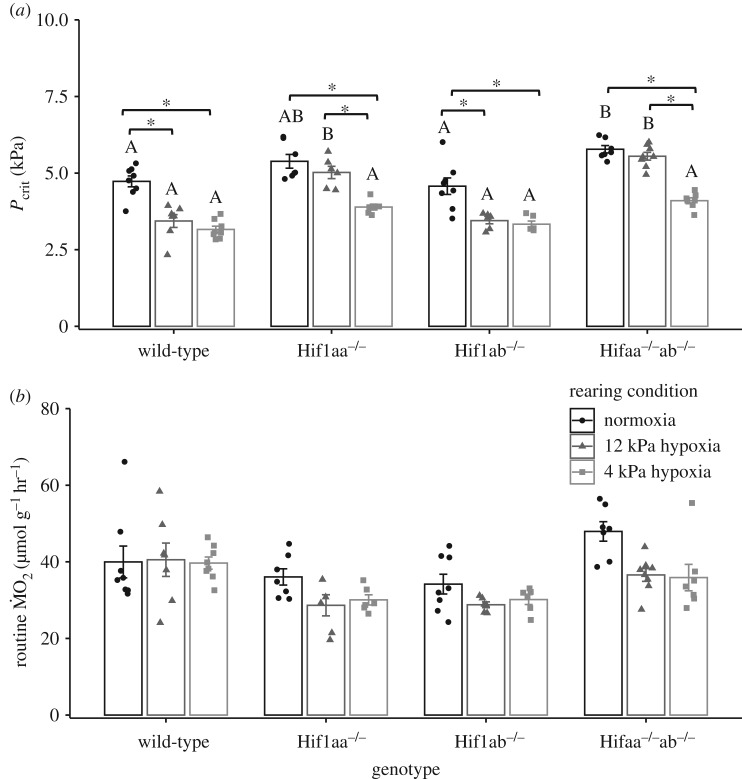

In larval zebrafish at 7 dpf, ṀO2 was measured in progressive hypoxia in fish reared in normoxia, severe and short duration hypoxia (4 kPa from 6 to 7 dpf) and mild and long duration hypoxia (12 kPa from 4 to 7 dpf) (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Mutant fish with knock out of both paralogues of Hif-1α had significantly higher Pcrit than wild-type zebrafish raised in normoxia (figure 1a). There was no difference in Pcrit between wild-type and Hif1ab−/− individuals, and Pcrit of Hif1aa−/− fish was not significantly different than Pcrit of either wild-type or Hif1aa−/−ab−/− fish. Larvae reared in severe/short hypoxia, caused a left shift in the ṀO2 versus water PO2 curve in all genotypes relative to the larvae raised in normoxia (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), resulting in a decrease in Pcrit (figure 1a). A similar decrease in Pcrit also occurred in wild-type and Hif1ab−/− larvae reared in mild/long hypoxia as compared to normoxia raised larvae. By contrast, there was no change in Pcrit between larvae raised in normoxia and mild/long hypoxia in either Hif1aa−/− or Hif1aa−/−ab−/− larvae (figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Critical O2 tension (Pcrit; a) and routine O2 consumption (routine ṀO2; b) in wild-type, Hif1aa−/−, Hif1ab−/− and Hif1aa−/−ab−/− 7 day post fertilization (dpf) larvae reared in normoxia, 12 kPa hypoxia from 4 to 7 dpf and 4 kPa hypoxia from 6 to 7 dpf. There was a significant interaction of rearing condition and genotype on Pcrit (two-way ANOVA; genotype × rearing condition: F = 3.9, p < 0.01, genotype: F = 46.8, p < 0.01, rearing condition: F = 72.8, p < 0.01; n = 6–8), but not routine ṀO2 (two-way ANOVA; genotype × rearing condition: F = 31.2, p = 0.3, genotype: F = 10.7, p < 0.01, rearing condition: F = 5.0, p < 0.01; n = 6–8). Different letters signify significant (p < 0.05) differences among genotypes within a rearing condition and an asterisk indicates significance among rearing conditions within a genotype. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m.

There was no significant interaction between genotype and the PO2 at which larvae were reared on routine ṀO2 (figure 1b).

The above Pcrit data were determined using the BSR method and an alternate method (LLO) was used to recalculate the Pcrit for larval data (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Pcrit values determined by LLO were lower than that of BSR, however, this was consistent across genotypes and rearing conditions. Using LLO determined Pcrit values, there was still a significant interaction of rearing condition and genotype on Pcrit (electronic supplementary material, table S1).

(b). Adults

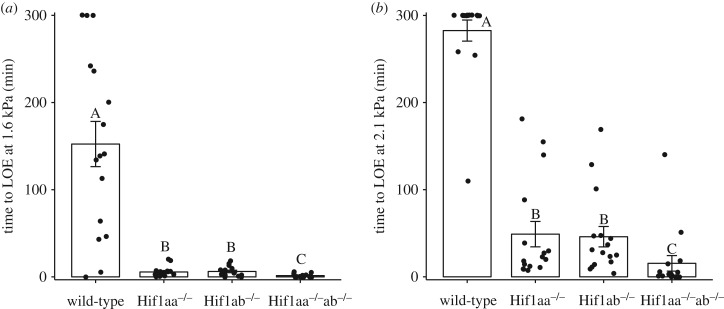

Wild-type adult zebrafish on average lost equilibrium at 152 ± 26 min, a significantly longer duration than in Hif1aa−/−, Hif1ab−/− and Hif1aa−/−ab−/− individuals when exposed to 1.6 kPa hypoxia (figure 2a). Individuals with single knockout of Hif-1α paralogue lost equilibrium within 6 ± 1 min (Hif1ab−/−) and 5 ± 1 min (Hif1aa−/−) of water PO2 stabilizing at 1.6 kPa. Fish with knockout of both Hif-1α paralogues were unable to retain equilibrium for longer than a minute. By contrast to the Hif-1α mutants, there was high variance in wild-type fish, consistent across all trials at 1.6 kPa. Some individuals lost equilibrium shortly after water PO2 levels reached 1.6 kPa while others did not lose equilibrium in the period of the experiment. At 2.1 kPa, with the exception of a few individuals, most wild-type fish did not lose equilibrium during the 300 min of exposure (figure 2b). Loss of either the Hif1aa or Hif1ab paralogue resulted in a significant decrease in the ability to retain equilibrium (49 ± 15 and 37 ± 9 min to LOE, respectively). Knockout of both paralogues caused a significantly decreased time to LOE (15.4 ± 9 min) as compared to knockout of either Hif1aa or Hif1ab paralogue.

Figure 2.

Time to loss of equilibrium (LOE) in wild-type, Hif1aa−/−, Hif1ab−/− and Hif1aa−/−ab−/− adult zebrafish exposed to 1.6 kPa (a) or 2.1 kPa (b) hypoxia. There was a significant effect of genotype on time to LOE at 1.6 kPa (χ2 = 32.62, p < 0.01, n = 23 wild-type, n = 16 Hif1aa−/− and Hif1aa−/−ab−/−, n = 15 Hif1ab−/−) and at 2.1 kPa (χ2 = 43.57, p < 0.01, n = 16 per genotype) (one-way non-parametric ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis)). Different letters signify significant (p < 0.05) differences between genotypes at each hypoxia exposure. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m.

O2 consumption as water PO2 progressively decreased was measured for all genotypes (electronic supplementary material, figure S2) and no difference was found in Pcrit (table 1). Adult Pcrit was reanalysed with an alternative method (LLO) and values were found to be higher than values determined by the BSR method (electronic supplementary material, table S2). However, this was consistent across genotypes and, similar to BSR, there was no statistical difference in Pcrit among genotypes (electronic supplementary material, table S2). Routine ṀO2 appeared lower in Hif1ab−/− fish than in fish of other genotypes, however it was not statistically different (p = 0.056).

Table 1.

Critical O2 tension (Pcrit) and O2 consumption (ṀO2) in wild-type, Hif1aa−/−, Hif1ab−/− and Hif1aa−/−ab−/− adult zebrafish. (There was no significant effect of genotype on routine ṀO2 (one-way ANOVA: F = 2.85, p = 0.056) or Pcrit (one-way ANOVA; F = 0.13, p = 0.94); n = 9 for wild-type, n = 7 for Hif1aa−/−, n = 8 for Hif1ab−/− and n = 6 for Hif1aa−/−ab−/−. Significance was set at p < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m.)

| genotype | ṀO2 (μmol g−1 h−1) | Pcrit (kPa) |

|---|---|---|

| wild-type | 12.5 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 0.3 |

| Hif1aa−/− | 13.3 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.3 |

| Hif1ab−/− | 9.4 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| Hif1aa−/−ab−/− | 12.8 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2 |

4. Discussion

Non-functionalization, or the loss of function of a redundant gene, is the likely evolutionary fate of most paralogues following a gene duplication event or a whole-genome duplication [34,35]. With the exception of zebrafish and other cyprinid fishes that have retained functional paralogues of Hif-1α, in most teleost fishes only remnants of the duplicated copies of hif-1α genes remain that arose during the teleost-specific whole-genome duplication [16]. Given the involvement of Hif-1α in a multitude of biological processes (e.g. angiogenesis, apoptosis, development), knocking out Hif-1α function is an important tool for evaluating the effects of Hif-1α on the overall hypoxic phenotype and for teasing apart the specific effects of each paralogue. In the present study, complete loss of Hif-1α significantly impaired hypoxia tolerance in both larval and adult zebrafish. Depending on the measure of hypoxia tolerance (i.e. Pcrit or time to LOE) and life-history stage, there were differential effects of the Hif1aa and Hif1ab paralogues, suggesting either sub-functionalization or neo-functionalization of the paralogues. In larval zebrafish, Hif1aa was implicated in determining Pcrit and shaping hypoxic pre-conditioning, while loss of either paralogue affected time to LOE to a similar degree in adult fish.

(a). Loss of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in larval zebrafish

Hypoxia tolerance can be assessed using several different methods, including determination of Pcrit, an important measure of effectiveness of extraction of O2 from hypoxic water and delivery of the O2 to the site of utilization in the tissue [21,36]. Individuals with a lower Pcrit can maintain cellular O2 supply at lower water PO2 than individuals with high Pcrit, which could enhance survival in hypoxia. In larval zebrafish raised under normoxic conditions, Pcrit was highest in individuals with knockout of both Hif-1α paralogues (Hif1aa−/−ab−/−, figure 1), indicating that a limitation in ability to maintain O2 supply occurred at higher water PO2 in the Hif1aa−/−ab−/− fish than in wild-types. This finding suggests that Hif-1α significantly impacts capacity for O2 extraction during hypoxia in larval zebrafish. The specific mechanism by which a loss of Hif-1α increases Pcrit is unknown. However, Hif-1α was previously shown to play a role in the hypoxic hyperventilatory response (HVR) in larval zebrafish [22]. A knockout of Hif-1α diminished the HVR [22] and by 7 dpf larvae hypoxic hyperventilation was shown to reduce Pcrit [28]. Hif-1α is also known to be a regulator of genes involved in angiogenesis [19] and a recent study demonstrated that Hif-1α plays an important role in macrophage-dependent angiogenesis in developing zebrafish larvae [20]. It is possible that a lack of Hif-1α during development may delay blood vessel proliferation which could limit ability to maintain cellular O2 supply during exposure of larvae to hypoxia. Extensive vascularization along the body is probably more important in 7 dpf larvae than in adult fish given that larvae at this stage primarily rely on cutaneous respiration [37]. There was no significant difference in Pcrit between wild-type larvae and Hif1aa−/− or Hif1ab−/− larvae, indicating that the presence of either paralogue is sufficient to maintain O2 extraction and use in hypoxia to a similar degree as wild-type larvae.

The beneficial impact of previous hypoxia exposure on a subsequent one (hypoxic pre-conditioning), was demonstrated previously in zebrafish larvae [38]. Exposure of 24 h post fertilization (hpf) larvae to hypoxia led to an increased ability to regulate and maintain O2 uptake in hypoxia in 4 dpf fish, while a similar exposure of 18 hpf larvae did not elicit similar hypoxic pre-conditioning. There was a significant increase of Hif-1α in 24 hpf but not 18 hpf fish, thereby indirectly linking the pre-conditioning effect to the Hif-1α pathway [38]. In the current study, we provide, to our knowledge, the first direct evidence implicating Hif-1α in hypoxic pre-conditioning in larval fish, an effect that was dependent on the nature of the hypoxia exposure.

For larvae raised in mild, longer duration (12 kPa from 4 to 7 dpf) hypoxia, wild-type fish exhibited a significant decrease in Pcrit, an effect that was not observed in larvae experiencing double knockout of Hif-1α (figure 1). The contribution of Hif-1α to the hypoxic pre-conditioning appears to be primarily related to the Hif1aa paralogue because its knockout (unlike knockout of Hif1ab) also prevented the decrease in Pcrit that was indicative of pre-conditioning. In 5–8 dpf zebrafish larvae, the vascularization index was significantly increased by hypoxia [39]. Induction of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in zebrafish has been attributed to the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [40], which is known to be regulated by Hif-1α [19]. Enhanced vascularization in hypoxia probably improves O2 uptake, thus decreasing Pcrit. It is possible that in fish with knockout of the Hif1aa paralogue raised in mild/long hypoxia, that there was no decrease in Pcrit because angiogenesis did not occur to the same extent. If this were the case, it would point to a control of VEGF in hypoxia by Hif1aa but not Hif1ab, suggesting sub-functionalization of the Hif-1α paralogues. It would be of interest for future work to examine vascularization in wild-type and Hif-1α knockout larvae raised under normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

For larvae raised in severe, shorter duration (4 kPa from 6 to 7 dpf) hypoxia, improved hypoxia tolerance (a lowering of Pcrit) was observed in all genotypes. The mechanisms contributing to the decrease in Pcrit in response to this particular hypoxia regimen does not appear to be linked to the Hif-1α pathway. The specific strategies fish employ to cope with hypoxia is dependent on the type of hypoxia stress [36,41]. In keeping with this paradigm, the impact of Hif-1α knockout on the aspects of the O2 cascade that are altered to enhance O2 uptake appears to differ in larval zebrafish depending on the duration and/or magnitude of hypoxic stress. Alternatively, it is worth pointing out that the role of Hif-1α on the hypoxic response of larvae raised in severe, short duration hypoxia may be masked by functional compensation from alternative mechanisms (e.g. Hif-2α). It is difficult to determine if the lack of apparent effect of Hif-1α was a result of potential redundancy in the hypoxic stress response or whether it was a result of Hif-1α not playing a role in this type of hypoxic stress. However, independent of the underlying cause, a complete knockout of Hif-1α did not have an effect on Pcrit following severe, short duration hypoxic pre-conditioning.

(b). Loss of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in adult zebrafish

Time to LOE is an important metric of hypoxia tolerance because LOE is thought to lead to imminent death, and indeed time to LOE is a good predictor of survivorship in hypoxia (e.g. [42]). In wild-type adult zebrafish, individuals lost equilibrium at PO2 well below Pcrit. On average, time to LOE was 2.5 h in fish exposed to 1.6 kPa hypoxia, which was increased markedly in fish exposed to 2.1 kPa hypoxia, with only a few individuals losing equilibrium within 5 h (figure 2). There was high variability across trials in time to LOE in wild-type fish. In a previous study, sex and season were noted to have a significant effect on survival in zebrafish experiencing severe hypoxia [43]. While all trials in the current study were performed over a short time frame (approx. four weeks), both males and females were tested, which may have contributed to at least some of the variation in time to LOE. However, while variation within wild-type zebrafish (and that of the knockout lines) may be affected by sex, contribution of sex differences to the variation among the genotypes is unlikely to be significant given that similar sex ratios were maintained in each genotype (data not shown). Future work should focus on the mechanistic underpinnings of the variation in time to LOE in wild-type zebrafish.

A complete loss of Hif-1α significantly reduced the time to LOE at both levels of hypoxia, indicating a severe compromise in hypoxia tolerance in adult zebrafish (figure 2). Time to LOE also was reduced in the single paralogue knockouts, Hif1aa−/− and Hif1ab−/− individuals, yielding similar decrements to hypoxia tolerance. The double knockout of Hif-1α yielded the lowest time to LOE, and the effect was greater than the sum of the individual Hif-1α knockout effects.

LOE has been linked to a severe disruption of brain homeostasis [44–46]. Exposure to hypoxia limits ATP production, leading to energy imbalance and a failure to meet the energetic requirements of ionic and osmotic homeostasis. This severely disrupts membrane depolarization, leading to cell death [47]. If loss of Hif-1α further limits capacity for ATP production, via impact on hypoxia-induced genes involved in aerobic and/or anaerobic metabolism, it may explain the decreased time to LOE as compared to wild-type zebrafish. In mammals, known targets of Hif-1α, such as haem oxygenase 1 and adrenomedullin, have been shown to be neuroprotective during cerebral ischaemia [48], and it is possible that in the Hif-1α knockout zebrafish, these neuroprotective mechanisms may be impacted increasing likelihood of earlier onset of brain dysfunction leading to LOE.

Unlike time to LOE, there was no difference in Pcrit or routine ṀO2 between wild-type and Hif-1α knockouts in adult fish (table 1). The impact of Hif-α on hypoxia tolerance in adult zebrafish appears to be equivocal depending on what metric of hypoxia tolerance is considered, time to LOE or Pcrit. However, the underlying physiological mechanisms that influence these metrics are at least in part distinct [21,36] and the results indicate that Hif-1α impacts hypoxic defence mechanisms contributing to increased time to LOE rather than Pcrit. A lack of difference in Pcrit among the genotypes suggests that the loss of Hif-1α does not impede O2 uptake and consequently aerobic metabolism in adult zebrafish. However, differences in anaerobic metabolism and/or metabolic depression may underlie the reduced time to LOE in individuals experiencing loss of Hif-1α. There is little evidence of metabolic depression in hypoxic adult zebrafish, pointing to a compromised anaerobic metabolism in the Hif-1α knockout fish. Because Hif-1α transcriptionally regulates many of the enzymes involved in glycolysis, including hexokinase, enolase and lactate dehydrogenase, as well as glucose transporters [5,6], knockout of Hif-1α may impact anaerobic metabolism by reducing glycolytic capacity. In support of this idea, a phylogenetically corrected comparative approach that analysed hypoxia tolerance in Danio and Davario genera found that there was a difference among species in time to LOE but not Pcrit, and that the variation was linked, in part, to differences in anaerobic energy metabolism [49].

5. Conclusion

In the current study, we demonstrate that Hif-1α significantly improves aspects of hypoxia tolerance in larval and adult zebrafish. Knockout of either Hif1aa or Hif1ab markedly decreased time to LOE in adult zebrafish exposed to hypoxia, possibly owing to diminished anaerobic metabolic capacity. Although not observed in adults, knockout of both paralogues of Hif-1α (Hif1aa−/−ab−/−) resulted in higher Pcrit or decreased hypoxia tolerance in normoxia-raised larvae. Hypoxic pre-conditioning, which was confirmed in larval zebrafish by a decrease in Pcrit, was mediated specifically by the Hif-1aa paralogue, although the role of Hif-1α in pre-conditioning was dependent upon the magnitude and/or duration of the hypoxic event. Both Hif-1α paralogues are important determinants of hypoxia tolerance and future work should focus on examining the physiological mechanisms through which each Hif-1α paralogue exerts its effects on hypoxia tolerance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Christine Archer and the University of Ottawa aquatic care facility for their help and knowledge of animal husbandry.

Ethics

All procedures for animal use and experimentation were carried out in compliance with the University of Ottawa Animal Care and Veterinary Service guidelines under protocol BL-1700 and adhered to the recommendations for animal use provided by the Canadian Council for Animal Care.

Data accessibility

Larval and adult zebrafish MO2 versus PO2 data used to calculate Pcrit (electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2, respectively) and a comparison of methods of Pcrit determination in larval and adult zebrafish (electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S2, respectively) have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

M.M. and S.F.P. designed the experiments; M.M. carried out the experiments, M.M and C.B. conducted the statistical analyses, M.M. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and all authors provided input on the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada Discovery grant to S.F.P. and a NSERC Post-Doctoral Fellowship to M.M.

References

- 1.Semenza GL, Wang GL. 1992. A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis bind to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 5447–5454. ( 10.1128/MCB.12.12.5447) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semenza GL. 2007. Life with oxygen. Science 318, 62–64. ( 10.1126/science.1147949) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semenza GL. 1998. Hypoxia-inducible 1: master regulator of O2 hemeostasis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8, 588–594. ( 10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80016-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semenza GL. 2000. HIF-1: mediator of physiological and pathophysiological responses to hypoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 88, 1474–1480. ( 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.4.1474) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semenza GL. 2003. Targetting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev. 3, 721–732. ( 10.1038/nrc1187) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J-W, Bae S-H, Jeong J-W, Kim S-H, Kim K-W. 2004. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1)α: its protein stability and biological functions. Exp. Mol. Med. 36, 1–12. ( 10.1038/emm.2004.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rytkonen KT, Ryynanen HJ, Nikinmaa M, Primmer CR. 2008. Variable patterns in the molecular evolution of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α (HIF-1α) gene in teleost fishes and mammals. Gene 420, 1–10. ( 10.1016/j.gene.2008.04.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorenzo FR, et al. 2014. A genetic mechanism for Tibetan high-altitude adaptation. Nat. Genet. 46, 951–956. ( 10.1038/ng.3067) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma Y-F, Han X-M, Huang C-P, Zhong L, Adeola AC, Irwin DM, Xie H-B, Zhang Y-P. 2019. Population genomics analysis revealed origin and high-altitude adaptation to Tibetan pigs. Sci. Rep. 9, 11463 ( 10.1038/s41598-019-47711-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikinmaa M. 2002. Oxygen-dependent cellular functions: why fishes and their aquatic environment are a prime choice of study. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 133, 1–16. ( 10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00132-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rytkonen KT, Vuori KAM, Primmer CR, Nikinmaa M. 2007. Comparison of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in hypoxia-sensitive and hypoxia-tolerant fish species. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D 2, 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chi W, Gan X, Xiao W, Wang W, He S. 2013. Different evolutionary patterns of hypoxia-inducible factor α (HIF-α) isoforms in the basal branches of Actinopterygii and Sarcopterygii. FEBS Open Bio. 3, 479–483. ( 10.1016/j.fob.2013.09.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rytkonen KT, Williams TA, Renshaw GM, Primmer CR, Nikinmaa M. 2011. Molecular evolution of the metazoan PHD-HIF oxygen-sensing system. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 1913–1926. ( 10.1093/molbev/msr012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasauer SMK, Neuhauss SCF. 2014. Whole-genome duplication in teleost fishes and its evolutionary consequences. Mol. Genet. Genomics 289, 1045–1060. ( 10.1007/s00438-014-0889-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruzicka L, et al. 2019. The zebrafish informationnNetwork: new support for non-coding genes, richer gene ontology annotations and the alliance of genome resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D867–D873. ( 10.1093/nar/gky1090) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rytkonen KT, Akbarzadeh A, Miandare HK, Kamei H, Duan C, Leder EH, Williams TA, Nikinmaa M. 2013. Subfunctionalization of cyprinid hypoxia-inducible factors for roles in development and oxygen sensing. Evolution 67, 873–882. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01820.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rojas DA, Perez-Muizaga DA, Centanin L, Antonelli M, Wappner P, Allende M, Reyes AE. 2007. Cloning of hif-1 and hif-2 and mRNA expression pattern during development in zebrafish. Gene Expr. Pat. 7, 339–345. ( 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.08.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aragones J, et al. 2008. Deficiency or inhibition of oxygen sensor Phd1 induces hypoxia tolerance by reprogramming basal metabolism. Nat. Genet. 40, 170–180. ( 10.1038/ng.2007.62) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iyer NV, et al. 1998. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Genes Dev. 12, 149–162. ( 10.1101/gad.12.2.149) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerri C, Marin-Juez R, Marass M, Marks A, Maischein H-M, Stainier DYR. 2017. Hif-1α regulates macrophage-endothelial interactions during blood vessel development in zebrafish. Nat. Commun. 8, 15492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borowiec BG, Hoffman RD, Hess CD, Galvez F, Scott GR. 2020. Interspecific variation in hypoxia tolerance and hypoxia acclimation responses in killifish from the family Fundulidae. J. Exp. Biol. 223, jeb209692 ( 10.1242/jeb.209692) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandic M, Tzaneva V, Careau V, Perry SF. 2019. Hif-1α paralogues play a role in the hypoxic ventilatory response of larval and adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Exp. Biol. 222, jeb195198 ( 10.1242/jeb.195198) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes MC, Zimmer AM, Perry SF. 2019. The role of internal convection in respiratory gas transfer and aerobic metabolism in larval zebrafish (Danio rerio). Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 316, R255–R264. ( 10.1152/ajpregu.00315.2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boutilier RG, Heming TA, Iwama GK. 1984. Physicochemical parameters for use in fish respiratory physiology. In Fish physiology, vol. 10A (eds Hoar WS, Randall DJ), pp. 403–430. London, UK: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeager DP, Ultsch GR. 1989. Physiological regulation and conformation: a BASIC program for the determination of critical points. Physiol. Zool. 62, 888–907. ( 10.1086/physzool.62.4.30157935) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reemeyer JE, Rees BB. 2019. Standardizing the determination and interpretation of Pcrit in fishes. J. Exp. Biol. 222, jeb210633 ( 10.1242/jeb.210633) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vulesevic B, Perry SF. 2006. Developmental plasticity of ventilatory control in zebrafish, Danio rerio. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 154, 396–405. ( 10.1016/j.resp.2006.01.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan YK, Mandic M, Zimmer AM, Perry SF. 2019. Evaluating the physiological significance of hypoxic hyperventilation in larval zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Exp. Biol. 222, jeb204800 ( 10.1242/jeb.204800) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rees BB, Matute LA. 2018. Repeatable interindividual variation in hypoxia in the Gulf killifish, Fundulus grandis. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 91, 1046–1056. ( 10.1086/699596) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandic M, Speers-Roesch B, Richards JG. 2013. Hypoxia tolerance in sculpins is associated with high enzyme activity in brain but not in liver or muscle. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 86, 92–105. ( 10.1086/667938) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdallah SJ, Thomas BS, Jonz MG. 2015. Aquatic surface respiration and swimming behaviour in adult and developing zebrafish exposed to hypoxia. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 1777–1786. ( 10.1242/jeb.116343) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fox J, Weisberg S.. 2011. An R companion to applied regression, 2nd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; http://socserv.socsci.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pohlert T.2014. The pairwise multiple comparison of mean ranks package (PMCMR). R package. See http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=PMCMR .

- 34.Zhang J. 2003. Evolution by gene duplication: an update. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 292–298. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00033-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Innan H, Kondrashov F. 2010. The evolution of gene duplications: classifying and distinguishing between models. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 97–108. ( 10.1038/nrg2689) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandic M, Regan MD. 2018. Can variation among hypoxic environments explain why different species use different hypoxic survival strategies? J. Exp. Biol. 221, jeb161349 ( 10.1242/jeb.161349) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rombough P. 2002. Gills are needed for ionoregulation before they are needed for O2 uptake in developing zebrafish, Danio rerio. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 1787–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robertson CE, Wright PA, Koblitz L, Bernier NJ. 2014. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates adaptive developmental plasticity of hypoxia tolerance in zebrafish. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20140637 ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.0637) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yaqoob N, Scherte T. 2010. Cardiovascular and respiratory developmental plasticity under oxygen depeleted environment and in genetically hypoxic fish (Danio rerio). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 156, 475–484. ( 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.03.033) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao R, Jensen LD, Soll I, Hauptmann G, Cao Y. 2008. Hypoxia-induced retinal angiogenesis in zebrafish as a model to study retinopathy. PLoS ONE 3, e2748 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0002748) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borowiec BG, McClelland GB, Rees BB, Scott GR. 2018. Distinct metabolic adjustments arise from acclimation to constant hypoxia and intermittent hypoxia in estuarine killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus). J. Exp. Biol. 221, jeb190900 ( 10.1242/jeb.190900) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Claireaux G, Theron M, Prineau M, Dussauze M, Merlin F-X, Le Floch S.. 2013. Effects of oil exposure and dispersant use upon environmental adaptation performance and fitness in the Europea sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax. Aquat. Toxic. 130–131, 160–170. ( 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.01.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rees BB, Sudradjat FA, Love JW. 2001. Acclimation to hypoxia increases survival time of zebrafish, Danio rerio, during lethal hypoxia. J. Exp. Zool. 289, 266–272. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiAngelo CR, Heath AG. 1987. Comparison of in vivo energy metabolism in the brain of rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri and bullhead catfish, Ictalurus nebulosus during anoxia. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 88, 297–303. ( 10.1016/0305-0491(87)90118-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nilsson GE, Ostlund-Nilsson S. 2008. Does size matter for hypoxia tolerance in fish? Biol. Rev. 83, 173–189. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00038.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Speers-Roesch B, Mandic M, Groom DJE, Richards JG. 2013. Critical oxygen tensions as predictors of hypoxia tolerance and tissue metabolic responses during hypoxia exposure in fishes. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 449, 239–249. ( 10.1016/j.jembe.2013.10.006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boutilier RG. 2001. Mechanisms of cell survival in hypoxia and hypothermia. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 3171–3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harten SK, Ashcroft M, Maxwell PH. 2010. Prolyl hydroxylase domain inhibitors: a route to HIF activation and neuroprotection. Antioxid. Redox Sign. 12, 459–480. ( 10.1089/ars.2009.2870) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao L. 2008. Hypoxia tolerance and anaerobic capacity in Danio and Devario. MSc thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Larval and adult zebrafish MO2 versus PO2 data used to calculate Pcrit (electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2, respectively) and a comparison of methods of Pcrit determination in larval and adult zebrafish (electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S2, respectively) have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.