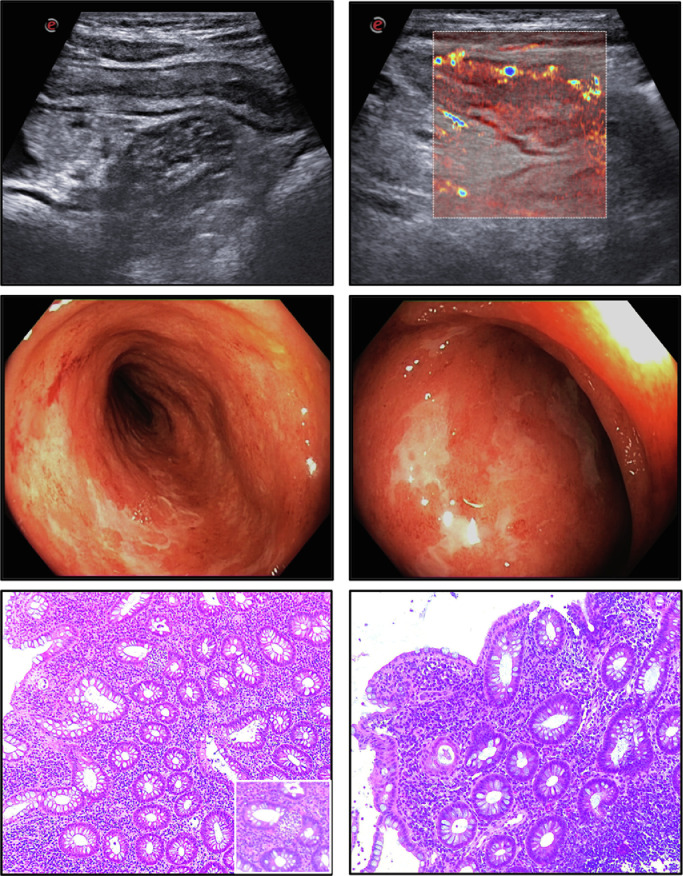

A 19-year-old, non-smoker woman with a recent history of fever, nausea, vomiting, bloody diarrhea and loss of taste and smell was admitted to the Tor Vergata Hospital. A nasofaringeal swab resulted positive for SARS-CoV-2. At entry, she had a body temperature of 38 °C, pulse of 110 beats/min, and 99% oxygen saturation. She had severe anemia but no shortness of breath or chest pain. C-reactive protein, platelets, fibrinogen and d-dimer were elevated. A chest and abdominal CT scan showed no pneumonia but increased contrast enhancement in the ileum and colon. No further pathogen was evidenced. After 1 week treatment with hydroxychloroquine, all the symptoms/signs disappeared except the severe anemia, which required a blood transfusion, and the enhanced inflammatory markers. The subsequent nasofaringeal swabs were negative for SARS-CoV-2. At day 16, a small bowel ultrasonography revealed an increased bowel wall thickening of the whole colon associated with an increased blood flow vascularization (Limberg score 4) (Fig. 1 , panels A-B) and ileocolonscopy showed an extensive colitis with mucosal friability, spontaneous bleeding and tiny and large ulcerations (Fig. 1, panels C-D). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the colonic biopsy samples showed ulcerations, crypt architectural distortion, a diffuse and active inflammatory infiltrate with crypt abscesses (Fig. 1, panels E-F). SARS-CoV2 RNA in colon/ileal and fecal samples was negative [1,2]. A diagnosis of ulcerative colitis was made and treatment with oral beclomethasone dipropionate and MMX-mesalamine was started.

Fig. 1.

Bowel ultrasonography (panels A–B), ileocolonoscopy (panels C–D) and histology (panels E–F) showing final diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease.

The clinical spectrum of SARS‐CoV‐2 ranges from asymptomatic or mild respiratory disease to pneumonia with respiratory distress syndrome and/or sepsis (Covid-19), which can result in a fatal outcome. Common symptoms are fever, cough, and shortness of breath, but gastrointestinal symptoms can occur in infected patients in line with the demonstration that SARS-CoV-2 RNA can be detected in feces and some of the infected patients remain positive in stools after becoming negative in respiratory samples [3]. Notably, the human intestine expresses constitutively high levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and the transmembrane serine protease, which are needed for SARS-CoV-2 to gain entry into the cells. Consistently, elevated levels of fecal calprotectin have been documented in Covid19-infected patients with ongoing diarrhea even in the absence of fecal SARS-CoV-2 RNA [4]. Overall these findings suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection can instigate an acute intestinal inflammation, which under specific circumstances (e.g. genetic susceptibility, exposure to environmental factors), can eventually evolve towards a chronic inflammatory disorder or potentially deteriorates the course of IBD [5]. The persistence of severe anemia and increased levels of inflammatory markers together with the marked mucosal inflammation, after clearance of the SARS-CoV-2, strongly support such a hypothesis.

Author contributions: EC, FZ, and GDVB evaluated the case, EC and GM drafted the manuscript.

This manuscript was not supported by any funding sources

Informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish these images.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for managing the patient condition and evaluating blood/stool samples to Vincenzo Malagnino, Giampiero Palmieri, Carmelina Petruzziello and Cristina Rapanotti.

References

- 1.Chan J.F., Yip C.C., To K.K. Improved molecular diagnosis of COVID-19 by the novel, highly sensitive and specific COVID-19-RdRp/Hel real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay validated in vitro and with clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;Mar 4 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00310-20. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y., Chen L., Deng Q. The Presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in Feces of COVID-19 Patients. J Med Virol. 2020;Apr 3 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25825. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeo C., Kaushal S., Yeo D. Enteric involvement of coronaviruses: is faecal-oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 possible? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(4):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30048-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Effenberger M., Grabherr F., Mayr L., Schwaerzler J. Faecal calprotectin indicates intestinal inflammation in COVID-19. Gut. 2020 Apr 20 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monteleone G., Ardizzone S. Are Patients with inflammatory bowel disease at increased risk for Covid-19 infection? J Crohn Colitis. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa061. Advance Access publication March 26, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]