Abstract

Objectives. To estimate the combined effect of California’s Tobacco 21 law (enacted June 2016) and $2-per-pack cigarette excise tax increase (enacted April 2017) on cigarette prices and sales, compared with matched comparator states.

Methods. We used synthetic control methods to compare cigarette prices and sales after the policies were enacted, relative to what we would have expected without the policy reforms. To estimate the counterfactual, we matched pre-reform covariate and outcome trends between California and control states to construct a “synthetic” California.

Results. Compared with the synthetic control in 2018, cigarette prices in California were $1.89 higher ($7.86 vs $5.97; P < .001), and cigarette sales were 16.6% lower (19.9 vs 16.6 packs per capita; P < .001). This reduction in sales equates to 153.9 million fewer packs being sold between 2017 and 2018.

Conclusions. California’s new cigarette tax was largely passed on to consumers. The new cigarette tax, combined with the Tobacco 21 law, have contributed to a rapid and substantial reduction in cigarette consumption in California.

California has been a national leader in tobacco control since the California Tobacco Control Program was established in 1989. As a result, cigarette pack sales per capita have declined 80% across the state over the past 30 years.1 Despite this, approximately 3.3 million adult smokers were still residing in California in 2016.2

A 2015 report by the National Academy of Medicine concluded that restricting tobacco sales to those aged 21 years or older would effectively reduce youth and young adult smoking and have a substantial positive effect on future population-level smoking rates.3 Consequently, in June 2016, California enacted a Tobacco 21 law.

Shortly afterward, in April 2017, California enacted a voter-approved tax increase of $2 per pack of cigarettes and an equivalent amount on electronic cigarettes and other tobacco products (Proposition 56). In addition to higher pack prices being a disincentive for current and potential smokers, the tax revenues fund tobacco-related law enforcement and medical treatment.4 However, not all tax initiatives are equally successful. Tax-induced price increases may be circumvented, for example, by introducing cheaper products or setting lower baseline prices for consumers who are most price sensitive.5

Our aim was to evaluate the extent to which Proposition 56 has been passed on to smokers and the combined effect the Tobacco 21 law and Proposition 56 have had on cigarette sales.

METHODS

We used synthetic control methods to construct a control group that matched pre-reform covariates and outcomes in California. To create the counterfactual, we used longitudinal outcome and covariate data from a weighted combination of 30 comparison states that did not introduce a statewide under-21 law or tobacco tax between 2011 and 2018. Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) shows the excluded states and the reason for their exclusion.

Outcomes and Covariates

We compiled annual state-level data from 2011 to 2018 on cigarette pack prices (calculated as retail revenue divided by sales) and sales per capita from “The Tax Burden on Tobacco, 1970-2018.”1 Time-varying, state-level covariates evaluated in the development of our counterfactuals included (for 2011–2018 except as indicated) percentage younger than 25 years, percentage male, percentage White, and log-transformed income per capita (2011–2017) from the American Community Survey; percentage aged 18 years or older who smoke cigarettes and percentage aged 18 years or older who drink alcohol from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; and tobacco control spending per capita (2011–2016) from the Bridging the Gap/ImpacTeen Project.6 We also evaluated log-transformed cigarette pack price for the sales model.1 All dollar values were inflated to 2018 dollars.

Statistical Analysis

We constructed our “synthetic” California groups as a weighted average of all available control states, with weights selected to find the best match (minimum mean squared prediction error) to California in outcome and covariate trends before policy implementation (2011–2016). We estimated the cigarette pack price and sales separately. After calculating the weights, we compared California and synthetic California in 2017 and 2018. Given the proximity of the Tobacco 21 law (June 2016) and Proposition 56 (April 2017) enactment, we assumed that their combined effect on cigarette sales started after 2016 so that the intervention time point aligned in our sales and price analyses. In a sensitivity analysis, however, we assumed that their effect on sales started after 2015 to account for the possibility that the Tobacco 21 law had an appreciable effect in the second half of 2016. In a further sensitivity analysis, we excluded New York from the donor pool because even though New York did not enact a tax increase or the Tobacco 21 law during the study period, it implemented several important tobacco control policy and administrative changes during the study period.

We assessed statistical significance by using a permutation-based test comparing the treated and synthetic control populations. Specifically, we estimated the placebo effect by assuming that each state in the control pool had been treated instead of California. We calculated a P value as the proportion of placebo effects at least as large as California’s effect, standardized by how closely the control state resembled California. The estimated reduction in the number of cigarette packs sold as a result of the Tobacco 21 law and Proposition 56 was calculated by multiplying the difference in cigarette sales per capita between California and its synthetic control by California’s population size in 2017 and 2018 then summing across those years.

We conducted statistical analyses with Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) using the user-generated “synth” and “synth_runner” packages.

RESULTS

The covariates and pre-reform outcome data used in our price analysis to construct synthetic California were percentage younger than 25 years; log-transformed income per capita; percentage aged 18 years or older who drink alcohol; and cigarette pack price for 2011, 2013, 2014, and 2016. For our cigarette sales analysis, synthetic California was constructed with log-transformed cigarette pack price; percentage younger than 25 years; log-transformed income per capita; and cigarette sales for 2011, 2013, and 2015. States with a nonzero weight contribution are listed in Table B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The minimum mean squared prediction error was 0.0006 for our price model and 0.0115 for our sales model, indicating that our synthetic control groups were an excellent fit for the pre-reform California data. The balance of our predictor variables are shown in Tables C and D (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

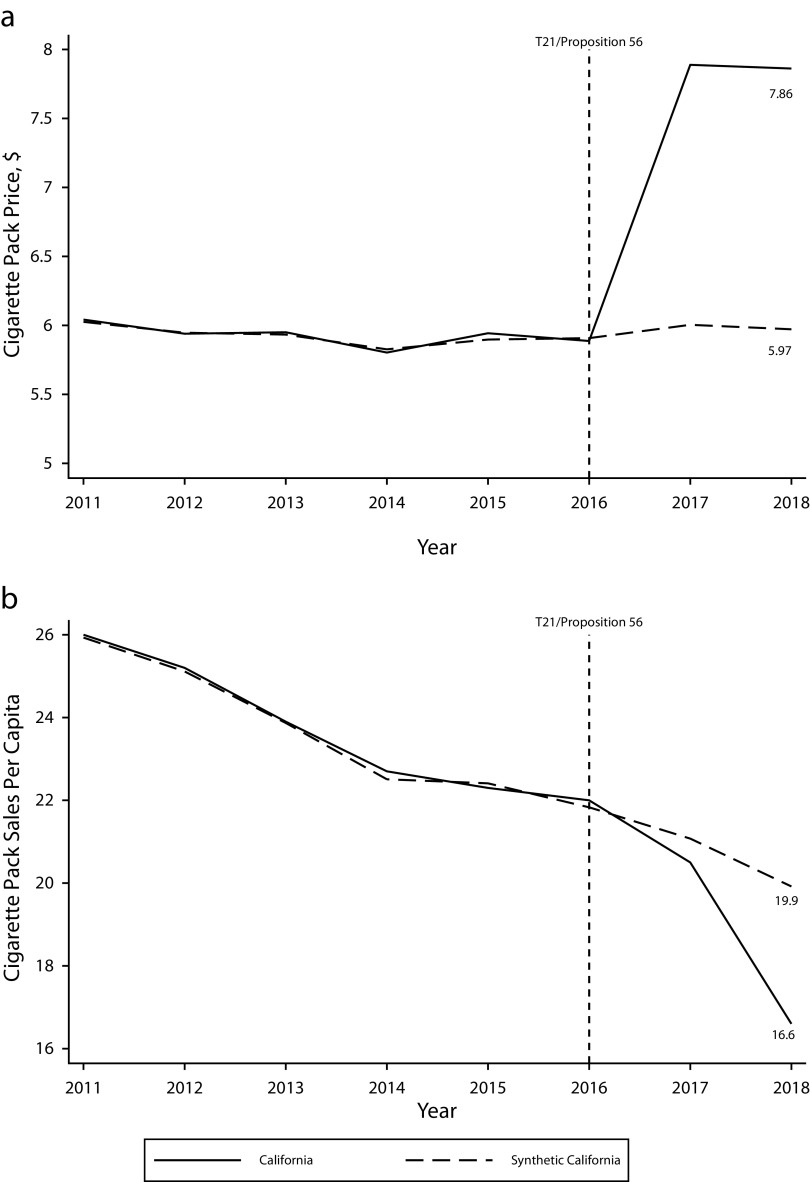

Figure 1a compares average cigarette pack prices over time between California and synthetic California. Proposition 56 resulted in consumers paying $1.89 more for a pack of cigarettes in 2018 than they would have paid without this policy ($7.86 vs $5.97; standardized P < .001). Our permutation tests indicated that none of the 30 potential control states had a price trend that diverged this much from their synthetic control (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

Comparison Before and After Implementation of the Tobacco 21 Law and Proposition 56 of Annual Cigarette (a) Prices and (b) Sales: California and Synthetic California, 2011–2018

Note. Cigarette pack prices are in 2018 dollars. The vertical dashed line indicates when the policies were implemented (2016).

Figure 1b compares cigarette pack sales over time between California and synthetic California. The Tobacco 21 law and Proposition 56 reduced 2018 cigarette sales in California by 16.6% (19.9 vs 16.6 packs per capita; standardized P < .001). This accounted for 61.1% of the total decline in sales between 2016 (22.0 packs per capita) and 2018 (16.6 packs per capita). Permutation testing indicated that none of the 30 potential control states had a sales trend that diverged this much from their synthetic control (Figure B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). On the basis of these findings, we estimate that the policies resulted in 22.6 million and 131.3 million fewer packs of cigarettes being sold in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

In our sensitivity analysis assuming the intervention effect on cigarette sales started after 2015, our findings were very similar to the main model: a decline of 3.4 packs per capita (Figure C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). When we excluded New York from the donor pool in our other sensitivity analysis, our price model was unchanged because New York did not contribute to the main analysis, and our sales model produced the same effect size as the main analysis: a decline of 3.3 packs per capita (Figure D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

DISCUSSION

We estimated that 95% of the Proposition 56 cigarette tax was passed on to consumers. This builds on a recent study of retail audit data that found overshifting of Proposition 56 (i.e., greater than $2) for 4 major cigarette brands but undershifting for several demographic groups and a significantly greater likelihood of stores offering discounts after implementation of the new tax.7 The price increase we observed, in conjunction with the similarly timed Tobacco 21 law, contributed to a reduction in cigarette pack sales in 2017 and 2018. This is consistent with a large previous literature on cigarette taxes4 and recent data on prohibiting tobacco sales for consumers younger than 21 years.8

Abadie et al.9 used methods similar to ours to estimate the effect of a $0.51 ($0.25 in 1989 dollars) tax increase on cigarettes introduced in California in 1989. This equated to a 28% increase in retail price (assuming it was all passed on to consumers) and resulted in pack sales declining by approximately 10% (9 packs per capita) in the first 2 years of the intervention. Abadie et al.’s estimates suggest a price elasticity of demand of −0.36, or a 10% increase in cigarette price producing a 3.6% decrease in cigarette consumption. We found that Proposition 56 increased cigarette pack prices by 31.7% (from $5.97 to $7.86). If we assume that the Tobacco 21 law contributed 2% to the reduction in cigarette sales we observed up to 2018, in line with national effect estimates,10 then Proposition 56 resulted in a 14.6% decline in pack sales in the first 2 years. This equates to a price elasticity of demand of −0.46, or a 10% increase in cigarette price producing a 4.6% decrease in cigarette consumption. Our and Abadie et al.’s price elasticities are consistent with other studies from the United States, although estimates vary widely.11 Encouragingly, this indicates that cigarette price increases in the modern era still may be an effective policy tool.

This study had 3 main limitations. First, we were not able to disaggregate our results by population subgroups or by individual policy. Further research should evaluate the extent to which youths, low-income earners, and minority groups have been affected by the Tobacco 21 law and Proposition 56. Second, the postintervention period was short. Abadie et al.9 showed that cigarette sales were still in decline more than 10 years after the 1989 tax increase in California, suggesting that our findings may be the beginning of a larger decline. Finally, we have assumed no residual confounding. Cigarette sales data are particularly vulnerable to changes in demand for other tobacco products and cigarette smuggling across jurisdictions. Importantly, synthetic control methods appear better able to account for time-varying unobserved confounding than standard approaches.12 Moreover, Proposition 56 applied to both cigarettes and electronic cigarettes, and in an assessment of California Department of Tax and Fee Administration monthly data, we found no evidence that the number of cigarette packs or tobacco products seized or the dollar value of tobacco products seized changed following implementation of the Proposition 56 tax.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

California’s Tobacco 21 law and Proposition 56 have reduced cigarette consumption and are likely to continue doing so for several years. Tobacco control initiatives should continue to consider age restrictions and tax increases to reduce the burden of tobacco-attributable illness.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Institutional review board approval was not required because this study used de-identified public data sets.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. The tax burden on tobacco, 1970-2018. June 13, 2019. Available at: https://chronicdata.cdc.gov/Policy/The-Tax-Burden-on-Tobacco-1970-2018/7nwe-3aj9. Accessed November 21, 2019.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State Tobacco Activities Tracking and Evaluation (STATE) System - California. Available at: https://nccd.cdc.gov/STATESystem. Accessed November 21, 2019.

- 3.Bonnie RJ, Stratton K, Kwan LY. Public Health Implications of Raising the Minimum Age of Legal Access to Tobacco Products. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. Committee on the Public Health Implications of Raising the Minimum Age for Purchasing Tobacco Products; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Institute of Medicine. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26269869. Accessed December 12, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; October 23, 2015. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/dar.12309. Accessed November 25, 2019.

- 5.Golden SD, Smith MH, Feighery EC, Roeseler A, Rogers T, Ribisl KM. Beyond excise taxes: a systematic review of literature on non-tax policy approaches to raising tobacco product prices. Tob Control. 2016;25(4):377–385. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.University of Illinois at Chicago Health Policy Center. Bridging the Gap/ImpacTeen Project. Available at: https://nccd.cdc.gov/STATESystem/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=OSH_State.CustomReports. Accessed 21 November 2019.

- 7.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Johnson TO, Andersen-Rodgers E, Zhang X, Williams RJ. Mind the gap: changes in cigarette prices after California’s tax increase. Tob Regul Sci. 2019;5(6):532–541. doi: 10.18001/trs.5.6.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman AS, Wu RJ. Do local Tobacco-21 laws reduce smoking among 18 to 20 year-olds? Nicotine Tob Res. 2019 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz123. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. J Am Stat Assoc. 2010;105(490):493–505. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winickoff JP, Hartman L, Chen ML, Gottlieb M, Nabi-Burza E, DiFranza JR. Retail impact of raising tobacco sales age to 21 years. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):e18–e21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Effectiveness of Tax and Price Policies for Tobacco Control. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, Vol 14. Available at: https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Handbooks-Of-Cancer-Prevention/Effectiveness-Of-Tax-And-Price-Policies-For-Tobacco-Control-2011. Accessed June 21, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.O’Neill S, Kreif N, Grieve R, Sutton M, Sekhon JS. Estimating causal effects: considering three alternatives to difference-in-differences estimation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2016;16(1-2):1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10742-016-0146-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]