Abstract

A set of nitro-activated ruthenium-based Hoveyda-Grubbs type olefin metathesis catalysts bearing sterically modified N-hetero-cyclic carbene (NHC) ligands have been obtained, characterised and studied in a set of model metathesis reactions. It was found that catalysts bearing standard SIMes and SIPr ligands (4a and 4b) gave the best results in metathesis of substrates with more accessible C–C double bonds. At the same time, catalysts bearing engineered naphthyl-substituted NHC ligands (4d–e) exhibited high activity towards formation of tetrasubstituted C–C double bonds, the reaction which was traditionally Achilles’ heel of the nitro-activated Hoveyda–Grubbs catalyst.

Keywords: metathesis, ruthenium, nitro catalysts, NHC ligands, olefins

1. Introduction

Although first transition metal complexes bearing N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands were studied independently by Wanzlick [1] and Öfele [2] in the late 1960s, these intriguing species remained unexplored for many years. They re-entered the stage in 1991 when Arduengo and co-workers prepared the first stable and crystalline N-heterocyclic carbene (IAd) [3]. Since then, because of easy fine-tuning of the steric and electronic properties of these compounds [4], NHCs have been widely used both as organocatalysts and as ligands for numerous transition metals catalysed reactions [5].

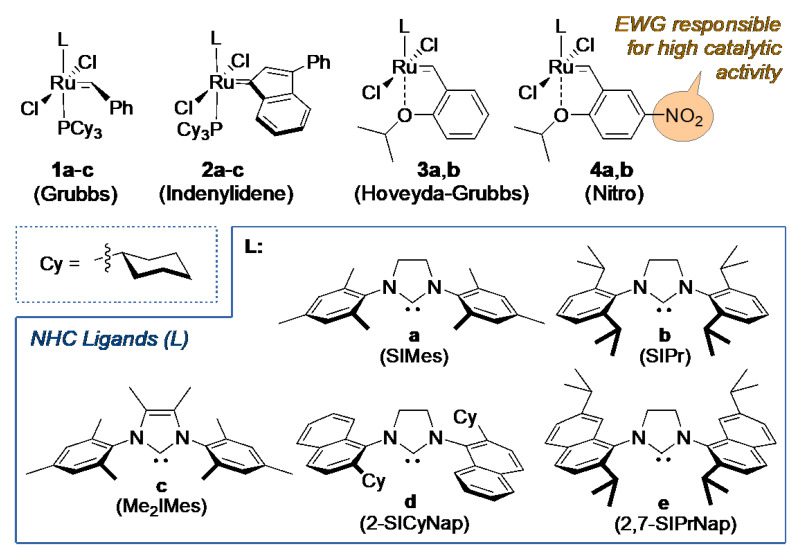

Olefin metathesis is a useful methodology enabling formation of multiple carbon–carbon double bonds [6,7,8]. Pioneering studies on this reaction were undertaken by scientists working in industry and in academia, where one might mention milestone contributions by Anderson and Merckling (Du Pont–norbornene polymerization) [9], Banks and Bailey (Philips Petroleum—so-called the three-olefin process) [10], and Natta (linear and cyclic olefin polymerization) [11]. In these early contributions, undefined catalytic systems and harsh conditions were usually applied, which limited the applicability of this transformation to rather simple systems. The discovery of Schrock's molybdenum [12] and Grubbs' first-generation ruthenium [13] complexes in the 1990s significantly enhanced pertinence of this methodology, but the real avalanche of olefin metathesis applications happened only after the introduction of the so-called second-generation Ru catalysts, i.e., Ru-complexes bearing at least one NHC ligand [14,15,16]. Currently, a number of complexes are commercially available, inter alia, general-use catalysts like Umicore Grubbs Catalyst M2a (1a) [17] introduced in 1999 [18] and its SIPr variant (1b), Umicore M2 (2a) [19], Hoveyda–Grubbs' catalyst (3a) [20] and SIPr analogue (3b), and nitro-catalysts 4a,b (Figure 1) [21,22,23].

Figure 1.

Examples of commercial Ru-based olefin metathesis catalysts and N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands (a–e).

Given the importance of the NHC ligand in ruthenium olefin metathesis catalysts, these ligands (L) have been optimised over the years. It was found that modification of the central five-membered N-heterocycle leads to decreasing activity or faster decomposition of the corresponding complex [24,25]. Similar results were obtained when replacing the aromatic side chain substituents with aliphatic ones [26,27,28,29,30]. However, unsymmetrically substituted NHC ligands, bearing one aromatic and one aliphatic N-substituent, have found their important niche as specialised catalysts [31,32,33]. On the other hand, introducing slightly bulkier aryl substituents compared to SIMes [34,35,36,37] or modifications of the 4 and 5 position in the imidazolium ring [26,38,39,40] cause usually an opposite effect resulting in an increase of the catalysts’ activity.

Besides varying the NHC ligand, benzylidene ligands offer a broad testing ground for modifications of the catalytic properties of these ruthenium complexes [41]. Our group has developed a nitro-activated version of the Hoveyda complex 4a [42,43,44,45]. The presence of an electron-withdrawing group (EWG) [43,46] in para position results in weakening of Ru-O bond, therefore accelerating the initiation rate of the resulting catalyst. As a consequence, 4a has been utilised as a successful metathesis catalyst in natural products and target-oriented syntheses [47,48], as well as the industrial context, such as in the ring-closing metathesis (RCM) at scale up to 7 kg leading to the antiviral BILN 2061 agent precursor at Boehringer–Ingelheim plant [49,50], anticancer agent Largazole at decagrams scale at Oceanyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc. [51], and in continuous flow using a scalable membrane pervaporation device at Snapdragon Chemistry, Inc. [52]. Interestingly, the iodide-containing analogue of 4a gave very good results in a number of challenging CM and RCM reactions [53]. Importantly, increased stability towards ethylene makes this diiodo derivative especially suitable for macrocyclization RCM of unbiased dienes [53]. Based on the excellent results reported by Bertrand and Grubbs on cyclic-alkyl-amino carbene (CAAC) ligands [54], Skowerski et al. obtained a CAAC analogue of 4a that promoted difficult RCM macrocyclization at 30 ppm, and cross metathesis of acrylonitrile at 300 ppm Ru loading and lower [55]. In addition, the successful nitro-catalyst design has provided an impetus for developing a number of derivative catalysts utilising the same EWG-activation concept [46,56,57,58]. On the other hand, replacement of the chelating oxygen atom by groups containing sulphur [59,60,61] or nitrogen [61,62,63] results in so-called latent complexes [64,65]. These catalysts exhibit increased stability, but have to be activated thermally, chemically or photochemically.

Herein, we describe the synthesis of a small set of nitro-activated catalysts bearing NHC ligands (L) of different steric properties (Figure 1 and Scheme 1). Catalyst 4a bearing a well-known SIMes ligand (Figure 1, NHC structures: a) was chosen as the benchmark, while the less known SIPr (Figure 1, 4b) [53] and the new complexes with Me2IMes [40] and with two naphthalene based ligands (Figure 1, NHC structures: c–e) developed by Dorta, were studied in detail [66,67,68,69]. These five complexes were characterised structurally and then tested in model olefin metathesis reactions [70] to check how steric properties of the different NHC ligands influence structural and catalytic properties of the resulting Ru complexes.

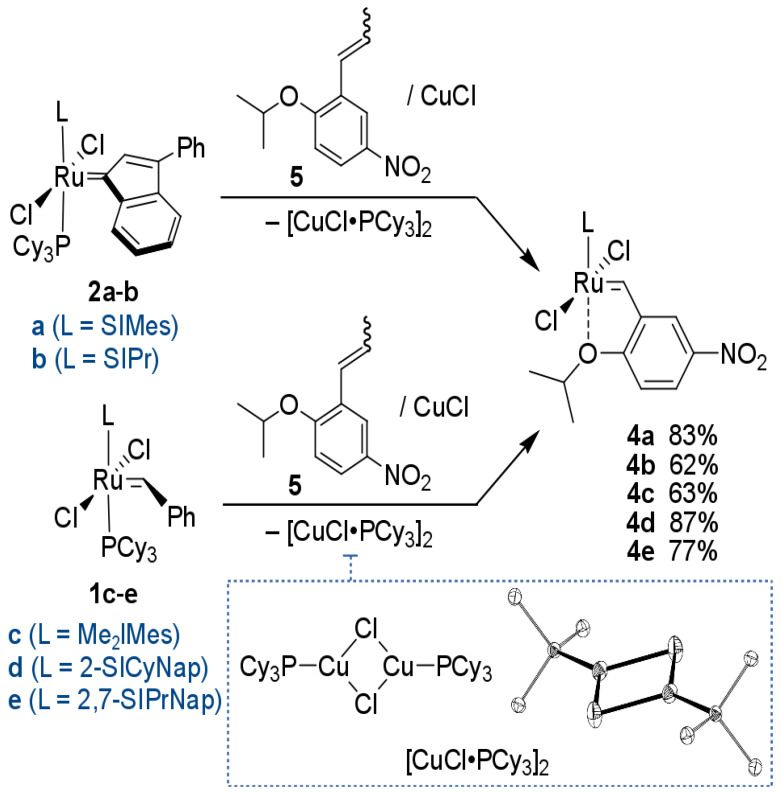

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of complexes 4a–e.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of the Ruthenium Complexes

All complexes were synthesised via the stoichiometric metathesis-ligand exchange reaction according to a procedure initially disclosed by Hoveyda [71] and illustrated on Scheme 1. Depending on the NHC precursor, the reactions were performed either in toluene or in DCM, in the presence of copper(I) chloride—a commonly used phosphine scavenger [71]. Complexes 4a and 4b were obtained from commercially available second-generation indenylidene complexes 2a and 2b in 83% and 62% yield, respectively. Interestingly, during these syntheses, we were able to isolate the putative CuCl•PCy3 complex in pure form and solve its crystallographic structure. It is stated that despite the fact that CuCl is being used as a phosphine scavenger in the preparation of various Hoveyda complexes for almost 20 years [71], according to our knowledge the product of this reaction has not yet been unambiguously characterised [72]. The synthesis of complexes 4c–e was carried out using appropriate Grubbs second generation complexes 1c–e as the source of ruthenium [40,66,68,73].

Complex 4c was obtained in the reaction of 1c with propenylbenzene derivative 5 in the presence of CuCl as a microcrystalline brownish solid with a moderate yield of 63%. Complexes 4d and 4e were obtained in a similar way from 5 and corresponding Grubbs-type catalysts [66,68,73] 1d or 1e as greenish microcrystalline solids in good yields, 87% and 77% respectively. General conditions for the synthesis of complexes 4a–e are shown in Table 1. As solids, all new Ru-compounds were stable when under an inert atmosphere and were stored for weeks without any sign of decomposition (acc. to TLC and NMR). Having these catalysts in hand, we were ready to study how different NHC arrangements [74] present in 4a–e influence the resulted complex structures and activity.

Table 1.

Detailed conditions used in synthesis of 4a–e.

| Catalyst | Solvent | Time (min) | Temp. (°C) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | Toluene | 60 | 80 | 83 |

| 4b | Toluene | 60 | 80 | 60 |

| 4c | Toluene | 60 | 60 | 63 |

| 4d | DCM | 20 | 40 | 87 |

| 4e | DCM | 10 | 40 | 77 |

2.2. Structure Analysis

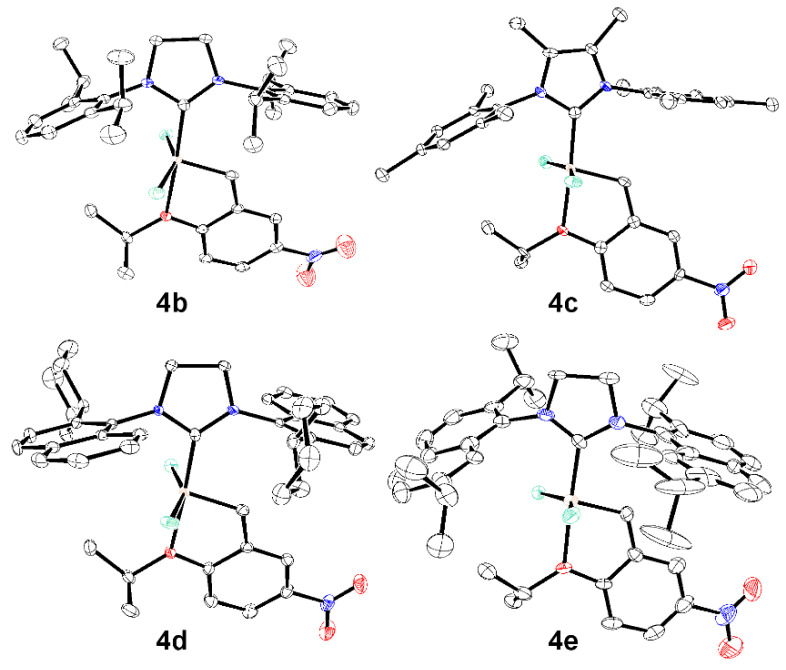

The crystal structures of 4b–e have been determined by applying single crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 2). It allows for investigation of structural conformations and steric subtleties of the studied compounds. The structure of 4a has been previously reported [75] and another related molecule—a catalyst 4f (Figure 3) developed by Buchmeiser [24] that contains saturated 1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl) 3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidin-2-ylidene ligand—was included in Table 2 for comparison purposes [24] (while selected bond lengths and angles are given in Table 2, the full set of X-ray data is provided in Table S1 in Supplementary Materials).

Figure 2.

Solid state crystallographic structures of 4a, 4b, 4c and 4e complexes. Colour codes: blue—nitrogen, red—oxygen, green—chlorine.

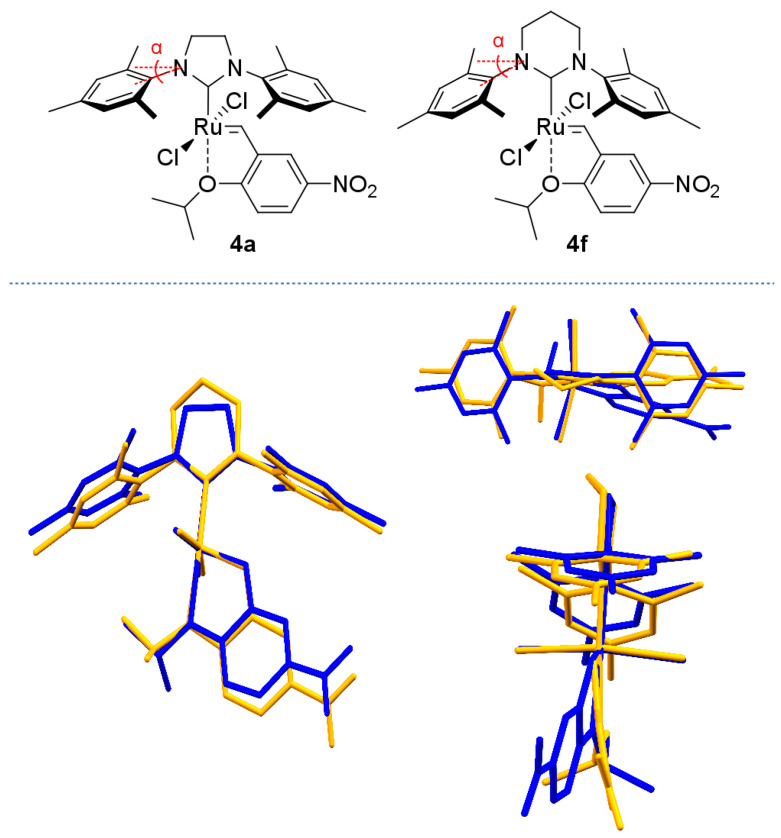

Figure 3.

Molecular structures of 4a and 4f. Front, top, and side view of molecule overlay of 4a (blue), 4f (orange). For angle α values see Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) in complexes 4a–e. The 4e structure contains two molecules in the asymmetric unit.

| 4a [75] | 4b | 4c | 4d | 4e a | 4f [24] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru‒C(1) | 1.979(3) | 1.985(4) | 1.990(4) | 1.970(3) | 2.002(9) 2.012(9) |

2.013(2) |

| Ru‒O(1) | 2.287(1) | 2.244(2) | 2.232(2) | 2.254(2) | 2.285(5) 2.252(5) |

2.310(2) |

| Ru‒C(2) | 1.825(2) | 1.829(4) | 1.821(3) | 1.827(3) | 1.836(9) 1.838(9) |

1.825(3) |

| Ru‒Cl(1) | 2.333(1) | 2.324(1) | 2.335(1) | 2.328(1) | 2.328(2) 2.328(2) |

2.343(1) |

| Ru‒Cl(2) | 2.330(1) | 2.333(1) | 2.339(1) | 2.331(1) | 2.328(2) 2.324(2) |

2.343(1) |

| C(1)-Ru-O(1) | 178.45(6) | 172.5(1) | 175.6(1) | 175.4(1) | 176.8(3) 177.8(3) |

175.93(8) |

| C(1)-Ru-C(2) | 101.36(8) | 102.1(1) | 103.0(1) | 102.4(1) | 99.9(4) 101.6(4) |

105.1(1) |

| Ru-C(2)-C(3)-C(4) | 8.6(2) | −8.9(5) | 5.9(4) | −5.4(3) | −2(1) 2(1) |

−4.5(3) |

| C(2)-Ru-C(1)-N(1) | 7.6(2) | 14.2(4) | 5.5(4) | 13.0(3) | −31.8(9) 27(1) |

0.8(2) |

| α | 19.8(1) | 20.8(3) | 20.1(2) | 19.0(2) | 19.4(7) 12.4(7) |

25.4(2) |

| VBur (%) | 35.4 | 36.5 | 34.7 | 34.6 | 34.8 36.1 |

38.0 |

a The 4e structure contains two molecules in the asymmetric unit.

All ruthenium complexes adopt a distorted square bi-pyramid coordination mode around the central ruthenium atom. The top of these pyramids are the O(1) oxygen of the benzylidene chelate and the C(1) carbon atoms of the NHC ligand. The average distance for the Ru-Cl bond amounts to 2.33 Å with a small variation from this value and the chloride atoms are in the trans configuration.

Most of the geometrical parameters do not differ much as they stay in the range of the 3σ threshold, however some interesting trends can be observed. The substitution of various NHC ligands strongly influences the Ru-O(1) bond. The bond is shortened in comparison to the parent SIMes-bearing (4a) compound (2.287(1) Å) with the exception of the NHC ring modification to the 6-member one in the 4f moiety (2.310(2) Å).

An opposite trend was found for the Ru-C(1) bond, which is elongated except for the 4d molecule. The Ru-C(2) bond changes within a smaller range with the shortest distance for the 4a and 4c (1.825(2)Å and 1.821(3) Å, respectively), whereas the longest bond distance is recorded for the 4e structure 1.836(9) Å and 1.838(9) Å).

The torsion angles are the most sensitive parameters in the crystal studies, and they differ in all studied complexes, although not that significantly. The Ru-C(2)-C(3)-C(4)-O(1) ring in the Hoveyda pre-catalyst is almost planar. The Ru-C(2)-C(3)-C(4) torsion angle, which defines the mutual orientation of the carbene bond and the NHC ligand is more flexible (Figure 4). Yet again, similar values were found for complexes 4a and 4c that form negative torsion angles, whereas one can see positive values of this angle for the 4b and 4d complexes, with the 4e precatalyst in the middle of the range. The ligands with more bulky character demand a bigger rotation of the C(2)-Ru-C(1)-N(1) torsion angle (4b, 4d and 4e).

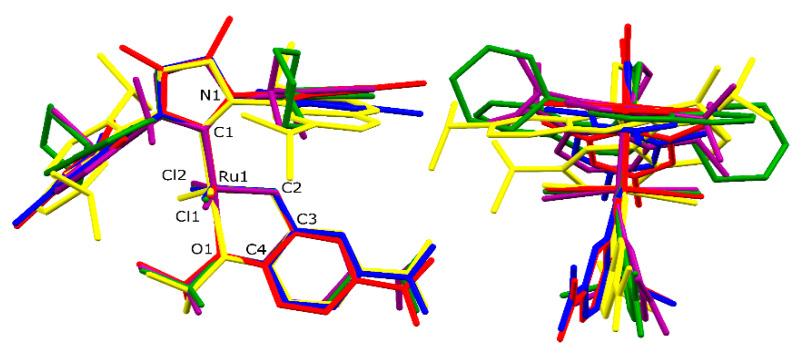

Figure 4.

Front and side view of molecule overlay of 4a (blue), 4b (purple), 4c (red), 4d (green) and 4e (yellow) complexes with label used to define selected geometrical parameters.

The angle α (Figure 3) represents visually how much the N-aryl ‘wings’ of the NHC ligands are lowered towards the metal centre. For (S)IMes-decorated complexes (4a, 4c) this angle measures 19.8 and 20.1°, and is only slightly larger (20.8°) in the case of SIPr bearing 4b. Importantly, the naphthyl members of the series have the N-substituents more ‘up’ (19.0° for 4d), being in strong contrast to complex 4f where the NHC wings are visibly lowered (25.4°) thus shielding the Ru centre more. However, some individual geometrical parameters can mislead the overall comparison. The root means square (RMS) analysis, taking into account the following six atoms: Ru, C(1), C(2), O(1), Cl(1) and Cl(2), has revealed similarity of the studied structures to the initial 4a compound. The RMS values are 0.090, 0.053, 0.057, 0.049, 0.062 Å and 0.104 Å for 4b, 4c, 4d, 4e′, 4e′′ and 4f, respectively. The structures 4c, 4d and 4e′ revealed a bigger similarity to the 4a complex, and this finding agrees with the Vbur% values.

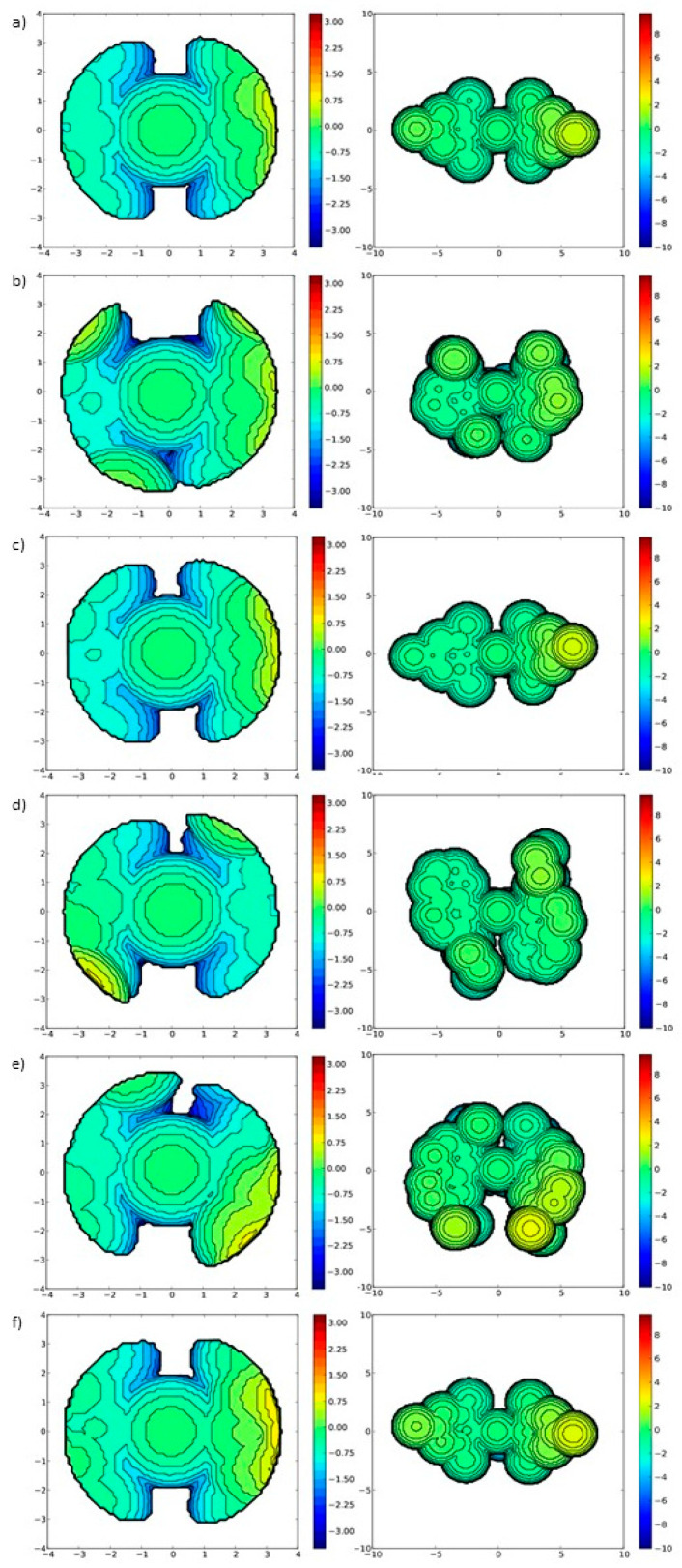

Using the data obtained from diffraction studies, we also calculated the buried volume (Vbur%) parameters [76] for the studied series of nitro-catalysts bearing NHC ligands (Figure 5). As expected, Vbur% value of SIPr in 4b (36.5%) was bigger than the one of SIMes in 4a (35.4%) and Me2IMes in 4c (34.7%). The value obtained for Dorta's 2-SICyNap, present in catalyst 4d (34.6%) was similar to the one obtained for Me2IMes in 4c (34.7%), even though the (cyclohexyl)naphthyl groups in 4d can be considered as relatively bulkier in comparison with smaller Mes N-substituents in 4c. Therefore it seems that they have similar steric demand of ligand (at least in the proximity of Ru).

Figure 5.

Steric maps calculated in SambVca software for complexes 4a to 4f. Standard (3.5 Å) and enlarged (10 Å) radii were used. (a) Catalyst 4a, (b) Catalyst 4b, (c) Catalyst 4c, (d) Catalyst 4d, (e) Catalyst 4e, (f) Catalyst 4f.

Because crystals of catalyst 4e that were measured by us contained two molecules in the asymmetric unit (4e′ and 4e′′), the Vbur% values were calculated for each of them (Table 2). The relatively big difference between them was probably caused by various spatial arrangements of the naphthyl groups in both of these molecules. 4a and 4c had the smallest NHC, while the 4d and 4e′′ the largest. In the case of compounds 4b and 4e" the greater steric hindrance around the Ru atom is visible on the Vbur maps, which directly influenced the increased calculated Vbur value. The least protected Ru centre in this series is visible for complexes 4c and 4d and corresponds to the lowest Vbur values. Buchmeiser's catalyst 4f has the highest Vbur value, which is probably correlated to the presence of the pyrimidine ring and different electron density than for the other NHCs. The difference between 4f and other catalysts is marginal and is best visible for 10 Å radii (Figure 5f), where below the central atom some negative electron density is visible.

2.3. Comparative Catalytic Activity Studies of Nitro-Catalysts 4a–e

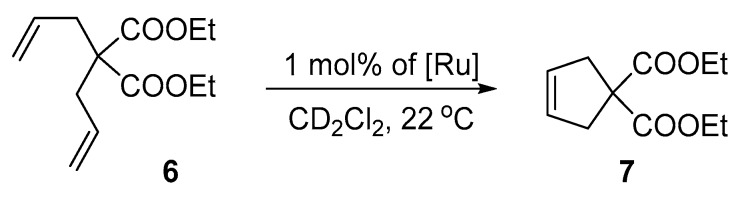

The performance of the nitro-catalysts 4a–e was evaluated in the ring-closing and ene-yne metathesis of six model substrates: diethyl 2,2-diallylmalonate (6), diethyl 2-allyl-2-(2-methylallyl)malonate (8), 2,2-di(2-methylallyl)tosylate (10), diethyl 2,2-di(2-methylallyl)malonate (12), allyl 1,1-diphenylpropargyl ether (14), and (1-(prop-1-en-2-yl-methoxy)prop-2-yne-1,1-diyl)dibenzene (16). In the first stage of this research the RCM reaction of 2,2-diallylmalonate (6), the most commonly used model substrate [77] was examined in the presence of 1 mol% of nitro-catalysts 4a–e (Scheme 2). Reactions were performed in NMR tubes at ambient temperature.

Scheme 2.

Ring-closing metathesis (RCM) of diethyl 2,2-diallylmalonate (6).

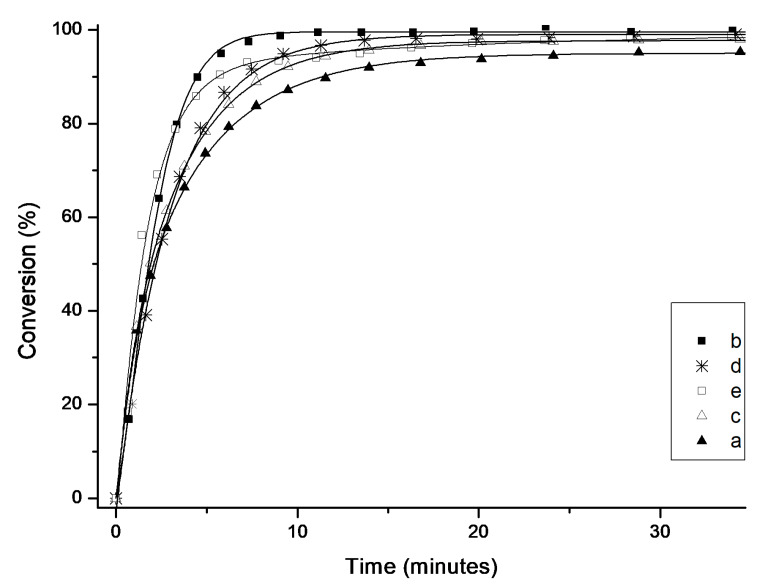

As expected for the EWG-activated family of catalysts, all tested complexes showed high activity and almost quantitative conversion was achieved after only 10–15 min (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Time/conversion curves for the RCM reaction of diethyl 2,2-diallylmalonate (6) with 1 mol% of 4a–e at 23 °C (monitored by 1H-NMR). Lines are visual aids only.

Interestingly, the least active complex was the SIMes-containing 4a. Complex 4c with an unsaturated Me2IMes ligand initiated slightly faster and provided maximal conversion after approximately 15 minutes. Both catalysts containing naphthyl substituents in their NHC ligands 4d and 4e exhibited even higher activity, with a slightly better result obtained for cyclohexyl-substituted catalyst 4d. The most active complex in the series was 4b bearing the SIPr ligand, which gave full conversion in less than 10 min.

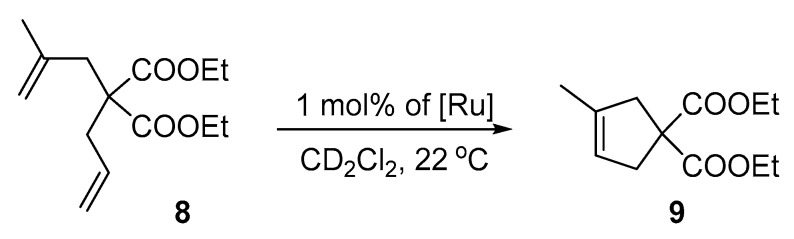

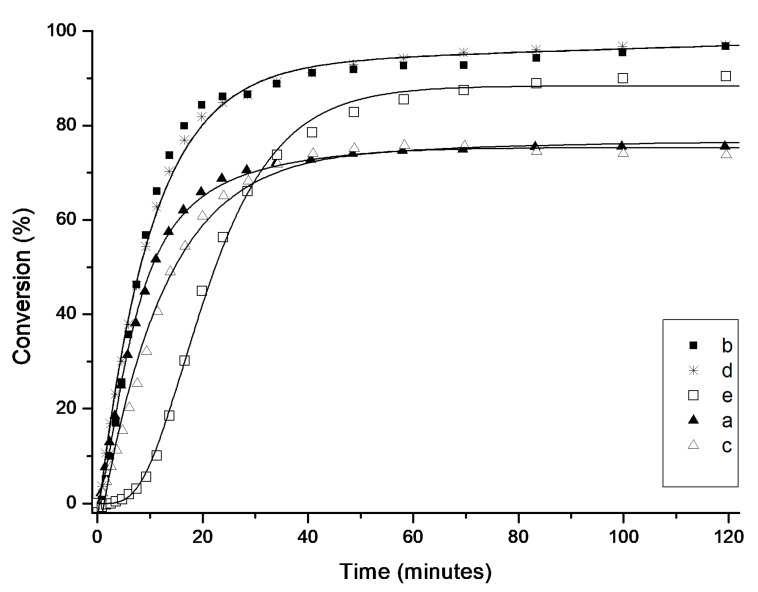

Diethyl 2,2-diallylmalonate (6) is a rather simple substrate to ring-close and is used more to examine whether a newly obtained complex exhibits any catalytic metathesis activity than to show in detail the subtle differences between similarly active catalysts. To determine how the activity of the new Ru-complexes compare, a more difficult substrate containing substituted double bonds, diethyl 2-allyl-2-(2-methyllyl)malonate (8) was studied next (Scheme 3, Figure 7).

Scheme 3.

RCM reaction of diethyl 2-allyl-2-(2-methylallyl)malonate (8).

Figure 7.

Time/conversion curves for the RCM reaction of diethyl 2-allyl-2-(2-methylallyl)malonate (8) with 1 mol% of 4a–e at 23 °C (monitored by 1H-NMR). Lines are visual aids only.

In this case, under similarly mild conditions as used for the RCM of 6, namely in the presence of 1 mol% catalyst and at room temperature, the general trend was maintained, although higher diversity between the tested catalysts was found (Figure 7). The highest activity was observed for 4b (SIPr) and 4d, (2-SICyNap) complexes containing relatively large aryl substituents in the NHC ligand. After 20 minutes they reached 84 and 81% yield, respectively, reaching in both cases 97% of RCM product 9 within 2 h.

An interesting S-shaped curve was observed for the second complex bearing bulky naphthyl-substituted NHC (4e). The latter admittedly initialised slower than the other counterparts, as after 20 min it reached only 45% conversion. Interestingly, after this initial latency period 4e initiated in a fast rate giving after 100 min 90% conversion of 8. As observed previously for the conversion of 6 to 7, the least reactive complexes in this model reaction were 4a and 4c, which initiated quicker than 4e but after two hours provided the product with only 75 and 73% yield, respectively.

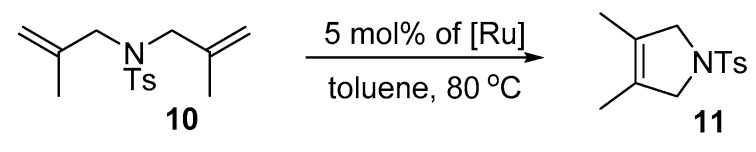

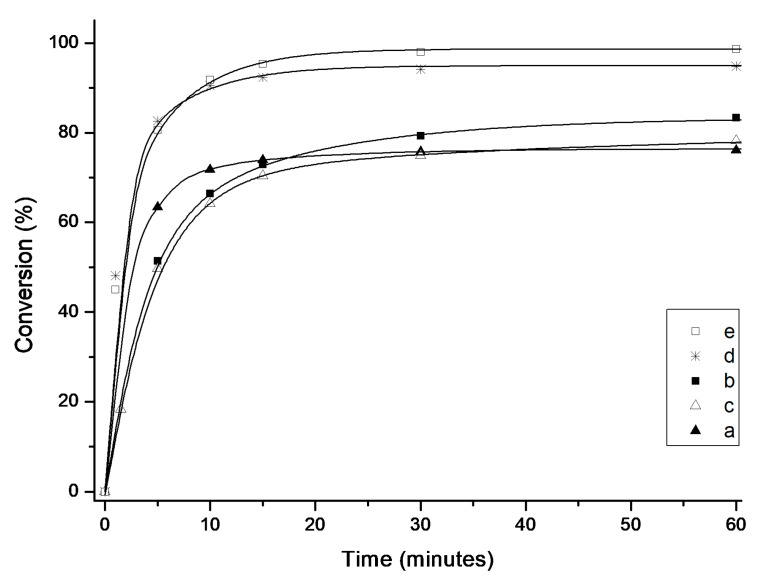

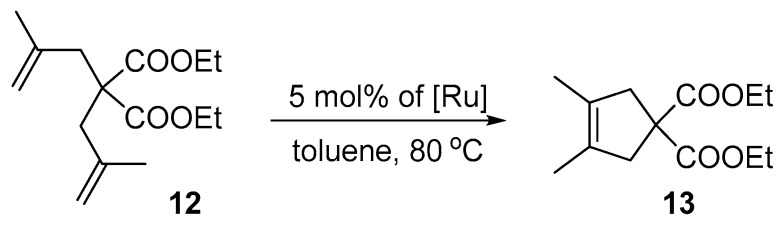

Next, we examined the activity of the nitro-catalysts in the RCM formation of tetrasubstituted olefins. Dienes 2,2-di(2-methyl allyl)tosylate (10) and diethyl 2,2-di(2-methyl allyl)malonate (12) are known to be more demanding and usually require the use of harsh conditions and specifically designed catalysts in order to achieve high yields [78]. Here, the reactions were performed in the presence of 5 mol% of complexes 4a–e at 80 °C (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

RCM reaction of 2,2-di(2-methylallyl)tosylate (10).

When tosylate 10 was used (Scheme 4), good to very good yields were achieved, however a significant difference between complexes bearing bulky naphthyl substituted NHCs (4d and 4e) and the more standard ones (4a–c) was observed (Figure 8). Despite the forcing conditions such as high catalyst loading and elevated temperature, the SIMes, SIPr and Me2IMes-bearing catalysts produced 10 in 76–83% yield after one hour. In contrast, bulkier Dorta-type complexes 4d and 4e reached almost quantitative conversion, 90 and 91% respectively, after only 20 min. Interestingly, when the reaction time was extended to 24 h also complex with SIPr ligand (4b) achieved a similar conversion of 91%, while 4a and 4c died reaching 80–82% only (Table 3).

Figure 8.

Time/conversion curves for the RCM reaction of 2,2-di(2-methylallyl)tosylate (10) with 5 mol% of 4a–e at 80 °C (monitored by GC). Lines are visual aids only.

Table 3.

RCM reaction of 2,2-di(2-methylallyl)tosylate (10) with 5 mol% of 4a–e at 80 °C (monitored by GC) after 1 and 24 h.

| Catalyst | Conversion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| After 1 h | After 24 h | |

| 4a | 76 | 82 |

| 4b | 83 | 91 |

| 4c | 78 | 80 |

| 4d | 98 | 99 |

| 4e | 95 | 97 |

When even more challenging diethyl 2,2-di(2-methylallyl)malonate (12) was used instead of 2,2-di(2-methylallyl)tosylate (10) in the presence of 5 mol% of Ru at 80 °C (Scheme 5, Table 4), only the most bulky Dorta complex 4e provided a relatively satisfactory result of 62% yield in 6 h. The other complexes (4a–d) were less active, leading to 9–21% of the desired product 13.

Scheme 5.

RCM reaction of diethyl 2,2-di(2-methylallyl)malonate (12).

Table 4.

RCM reaction of diethyl 2,2-di(2-methylallyl)malonate (12) with 5 mol% of 4a–e at 80 °C (monitored by GC) after 6 and 24 h.

| Catalyst | Conversion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| After 6 h | After 24 h | |

| 4a | 16 | 18 |

| 4b | 9 | 63 |

| 4c | 21 | 21 |

| 4d | 14 | 66 |

| 4e | 62 | 84 |

After extending the reaction time to 24 h, virtually no changes in conversion were observed in the case of complexes with mesitylene-based NHC ligands (4a and 4c). Pleasurably, we noticed a huge improvement in yield of the desired product when the reaction was conducted in the presence of Dorta-type (4e and 4d) and SIPr-based (4b) catalysts (Table 4). Especially in the case of the latter two, changes were significant (from 14% to 66% for 4d and from 9% to 63% for 4b).

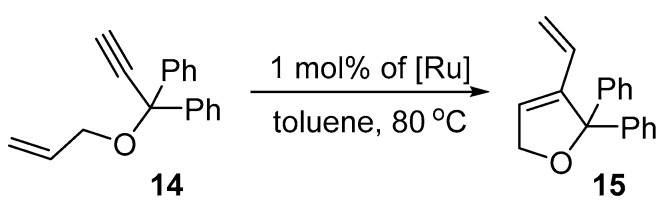

Ene-yne metathesis is a highly selective and atom-economical methodology for the synthesis of 1,3 dienes, which are valuable building blocks in organic synthesis [79]. To picture the application profile of the studied catalysts, two members of the ene-yne class of compounds were investigated with catalysts 4a–e. Reactivity profiles for the metathesis of allyl 1,1-diphenylpropargyl ether (14) were established first (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Ene-yne reaction of allyl 1,1-diphenylpropargyl ether (14).

In the ene-yne cycloisomerisation of easy to react 14 [80] the most active were catalysts containing the smallest substituents (4a–c), while those with more bulky side chain groups (4d–e) showed diminished conversions (Figure 9). Nevertheless, all catalysts, but one, 4d contain a large cyclohexyl substituent in the ortho position of the aryl ring, provided the desired product with yields above 80% during the first 6 h of the reaction. Further extension of the reaction time to 24 h resulted in slight improvement of the results leading to essentially quantitative conversions (over 90%) for 4a and 4c (Table 5).

Figure 9.

Time/conversion curves for the ene-yne reaction of allyl 1,1-diphenylpropargyl ether (14) with 1 mol% of 4a–e at 80 °C (monitored by GC). Lines are visual aids only.

Table 5.

Ene-yne reaction of allyl 1,1-diphenylpropargyl ether (14) with 1 mol% of 4a–e at 80 °C (monitored by GC) after 6 and 24 h.

| Catalyst | Conversion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| After 6 h | After 24 h | |

| 4a | 93 | 99 |

| 4b | 87 | 87 |

| 4c | 90 | 93 |

| 4d | 60 | 73 |

| 4e | 81 | 88 |

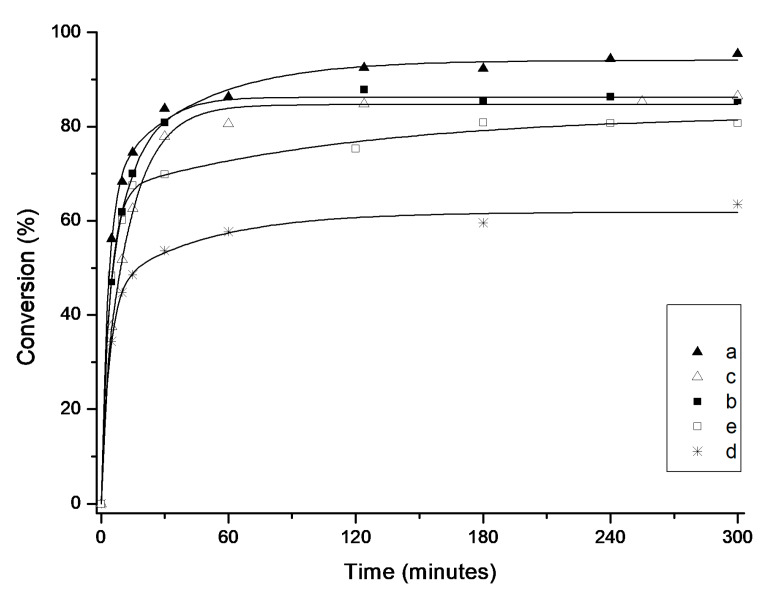

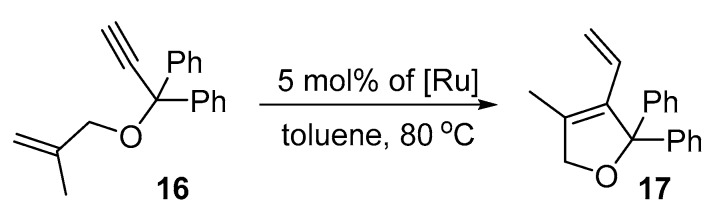

Next, the more challenging cycloisomerisation substrate (1-(prop-1-en-2-yl-methoxy)prop-2-yne-1,1-diyl)dibenzene (16) [81,82,83] was utilised (Scheme 7). As for substrate 12, also in this case the loading of the catalysts was increased from 1 to 5 mol% in order to obtain near-quantitative conversions.

Scheme 7.

Ene-yne reaction of (1-(prop-1-en-2-yl-methoxy)prop-2-yne-1,1-diyl)dibenzene (16).

Indeed, most of the complexes used gave the expected product with a yield of 90–100% in less than 6 hours, with 4d being the most active, and after extension of the reaction time to 24 h 100% of yield was reached (Table 6). The only exception was the complex 4b containing simple SIPr-ligand, which under these conditions gave only 25 and 41% conversion, after 6 and 24 h respectively.

Table 6.

Ene-yne reaction of (1-(prop-1-en-2-yl-methoxy)prop-2-yne-1,1-diyl)dibenzene (16) with 5 mol% of 4a–e at 80 °C (monitored by GC) after 6 and 24 h.

| Catalyst | Conversion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| After 6 h | After 24 h | |

| 4a | 88 | 99 |

| 4b | 15 | 42 |

| 4c | 94 | 97 |

| 4d | 94 | 98 |

| 4e | 74 | 98 |

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General

All reactions were carried out under argon flow in pre-dried glassware using Schlenk techniques. Reaction profiles performed in NMR tube were carried out in degassed CD2Cl2. CH2Cl2 (Sigma-Aldrich Sp. z o.o., Poznan, Poland) was dried by distillation with CaH2 under argon and was stored under argon. THF, toluene, n-hexane and xylene were dried by distillation with Na/K alloy. Flash chromatography was performed using Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany) silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh). NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or CD2Cl2 with Varian Mercury 400 MHz and Varian VNMRS 500 MHz spectrometers. MS (FD/FAB) was recorded with a GCT Premier spectrometer from Waters Corporation (Milford, MA, USA). MS (EI) spectra were recorded with an AMD 604 Intectra GmbH (Harpstedt, Germany) spectrometer. Other commercially available chemicals were used as received.

3.2. Synthesis of Complexes

Synthesis of 4a: Complex (2a) (220 mg, 0.232 mmol) was dissolved in toluene (7 mL), and 1-isopropoxy-4-nitro-2-(prop-1-en-1-yl)benzene (5) (61.6 mg, 0.278 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred for 5 min, CuCl (45.9 mg, 0.474 mmol) was added, and the mixture was heated at 80 °C for 30 min. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated in vacuo. From this point, all manipulations were carried out in air with reagent grade solvents. The product was purified by silica gel chromatography (AcOEt/c-hexane = 1:4 v/v). The solvent was evaporated under vacuum, and the residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (2 mL). MeOH (5 mL) was added and CH2Cl2 was slowly removed under vacuum. The precipitated was filtered, washed with MeOH (5 mL), and dried in vacuo to afford 4a as a green microcrystalline solid (130 mg, 83%). 1H-NMR (CD2Cl2, 500 MHz,): δ = 16.42 (s, 1H), 8.46 (dd, J = 9.1, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (s, 4H), 6.94 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 5.01 (sept, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 4.22 (s, 4H), 2.46–2.48 (m, 18H), 1.30 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 6H); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 289.1, 208.2, 156.8, 150.3, 145.0, 143.5, 139.6, 139.3, 129.8, 124.5, 117.2, 113.3, 78.2, 52.0, 21.3, 21.2, 19.4; IR (KBr): = 2924, 2850, 1606, 1521, 1480, 1262, 1093, 918, 745 cm−1; FDMS m/z [M+] 671.1.

Synthesis of 4b: Similar to the preparation of 4a, 5 (150 mg, 0.68 mmol) was added to the solution of complex 2b (690 mg, 0.68 mmol) in toluene (15 mL). The mixture was stirred for 5 min, and CuCl (135 mg, 1.36 mmol) was added. 4b was obtained as green microcrystalline solid (380 mg, 62%). 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 16.33 (s, 1H), 8.38 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (t, J= 7.7 Hz, 4H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 4H), 6.90 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 4.99 (m, 1H), 4.20 (s, 4H), 3.56 (m, 4H), 1.40 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 6H), 1.24 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 12H); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 283.7, 210.3, 156.6, 149.0, 143.6, 143.0, 136.2, 130.0, 124.4, 124.0, 116.7, 112.8, 77.7, 77.2, 77.0, 76.7, 54.5, 28.8, 26.5, 23.3, 21.7; IR (KBr):= 3096, 3069, 2970, 2951, 2927, 2868, 1527, 1341, 1270, 1095, 914, 742 cm−1; FDMS m/z [M+] 755.10.

Synthesis 4c: Complex 2c (500 mg, 0.571 mmol) was dissolved in toluene (11 mL), and 1-isopropoxy-4-nitro-2-(prop-1-en-1-yl)benzene (5) (190 mg, 0.856 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred for 5 min, CuCl (113 mg, 1.14 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 40 min. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and concentrated in vacuo. From this point, all manipulations were carried out in air with reagent grade solvents. The product was purified by silica gel chromatography (AcOEt/c-hexane = 1:5 v/v). The solvent was evaporated under vacuum, and the residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (2 mL). MeOH (5 mL) was added and CH2Cl2 was slowly removed under vacuum. The precipitated was filtered, washed with MeOH (5 mL) and dried in vacuo to afford 4c as a brownish microcrystalline solid (250 mg, 63%). 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 16.57 (s, 1H), 8.42 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (s, 4H), 6.89 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 4.98 (m, 1H), 2.48 (s, 6H), 2.18 (s, 12H), 1.97 (s, 6H), 1.35 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 6H); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 287.0, 167.0, 156.4, 145.0, 143.2, 139.7, 138.4, 129.2, 127.8, 123.3, 116.7, 112.7, 77.5, 77.3, 77.0, 76.8, 21.8, 21.1, 21.1, 19.1, 19.1; IR (KBr): = 3103, 3084, 2986, 2969, 2921, 1604, 1571, 1520, 1384, 1337, 1320, 1095, 746, 660 cm−1; FDMS m/z [M+] 697.1.

Synthesis of 4d: Similar to the preparation of 4c, 5 (86 mg, 0.389 mmol) was added to the solution of complex 1d (250 mg, 0.243 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (15 mL). The mixture was stirred for 5 min, and CuCl (48 mg, 0.486 mmol) was added. 4d was obtained as green microcrystalline solid (180 mg, 87 %). 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 16.04 (s, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 8.23 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d J = 8.6, 2H), 7.95 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (td, J = 6.9, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (td, J = 6.9, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d J = 2.5, 1H), 6.71 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 4.77 (m, 1H), 4.48–4.34 (m, 4H), 4.12 (q, J = 14.2, 7.1 Hz, 1H), 3.11 (s, 2H), 2.16 (s, 1H), 2.04 (s, 2H), 1.98–1.96 (m, 12H), 1.74–1.55 (m, 10H), 1.48–1.37 (m, 4H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 1.09 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 1.01 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 211.5, 156.5, 145.1, 143.7, 142.8, 133.0, 131.6, 129.8, 127.9, 127.0, 126.2, 125.2, 123.9, 116.6, 112.4, 77.5, 77.2, 77.0, 76.7, 60.3, 54.5, 53.4, 39.8, 36.2, 32.5, 31.5, 30.9, 28.2, 27.5, 26.6, 26.3, 25.8, 21.1; IR (KBr): = 3067, 2925, 2849, 1735, 1523, 1441, 1340, 1267, 1091, 914, 818, 747 cm−1; FDMS m/z [M+] 851.2.

Synthesis of 4e: Similar to the preparation of 4c, 5 (64.4 mg, 0.291 mmol) was added to the solution of complex 1e (200 mg, 0.194 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL). The mixture was stirred for 5 min, and CuCl (38.4 mg, 0.388 mmol) was added. 4e was obtained as green microcrystalline solid (128 mg, 77 %). 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 16.39 (s, 1H), 16.21 (s, 1H), 8.21 (dq, J = 8.9, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.95 (s, 1H), 7.86 (dd J = 8.3, 3.2, 2H), 7.63 (t, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.40 (m, 2H), 6.69 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 4.80–4.70 (m 1H), 4.60 (s, 1H), 4.47 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.65 (quint, J = 13.1, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 3.22 (quint, J = 13.5, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 3.11 (quint, J = 13.5, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 1.44–1.36 (m, 25H), 1.13 (d, J = 5.9 2H), 1.04 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 0.93 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 286.9, 286.6, 211.2, 210.7, 156.5, 147.0, 146.1, 143.9, 143.8, 142.9, 131.7, 131.0, 129.8, 129.7, 127.7, 126.3, 125.5, 123.7, 123.3, 123.2, 122.4, 116.6, 112.5, 112.4, 77.4, 77.2, 77.0, 76.7, 54.0, 34.7, 34.4, 29.2, 29.1, 25.8, 24.0, 23.5, 23.5, 23.3, 22.8, 22.6, 21.1, 21.0, 20.7; IR (KBr): = 3090, 3058, 2960, 2870, 1604, 1525, 1473, 1340, 1256, 1092, 845 cm−1; FDMS m/z [M+] 855.3.

4. Conclusions

The family of nitro-complexes containing NHC ligands with different steric properties was synthesised, characterised and investigated in terms of activity. Analysis of the solid-state geometrical parameters manifested some interesting relationships. Intuitively, the most important difference in geometry was expressed by angle α, representing visually how the N-aryl ‘wings’ of the NHC ligand are lowered towards the metal centre (Figure 4, Table 2). In the case of the SIPr-bearing 4b the N-aryl ‘flaps’ are slightly lowered compared to (S)IMes-decorated 4a,c. Interestingly, the naphthyl members of this series (4d–e) have the N-substituents even slightly more ‘elevated’ compared to their (S)IMes and SIPr counterparts (4a–b). This is in strong contrast to complex 4f where the NHC wings are visibly lowered, thus shielding much more the Ru centre. Interestingly, the latter complex, although very useful in cyclopolymerization of diynes, in model RCM reactions was found to be less reactive than the analogue SIMes Hoveyda-Grubbs complex [24]. The Vbur% values and steric maps calculated for the studied complexes illustrated the same picture, rendering the naphthyl-containing complexes 4d–e being the least crowded and 4f having the highest Vbur% value. The model reactions also sorted the tested complexes into two groups. While in the reaction of a simple model diene (6) all catalysts exhibited similarly high activity, in the case of a still rather straightforward cycloisomerisation of ene-yne 14, the less bulky NHC containing complexes 4a–c were more active. At the same time, with more demanding sterically crowded substrates, a significant advantage of complexes with bulkier NHC ligands (4b, 4d–e) was evident. Importantly, complexes 4d–e demonstrated high activity in formation of tetra-substituted C–C double bonds [78,84], the reaction which was traditionally Achilles’ heel of the nitro-catalyst [42,43,44,45]. It is stressed that in all cases the studied model reactions were very clean and no side-products were observed.

Overall, the comparative study here suggests that the elaborated naphthyl-based catalysts (4d–e) may be better for challenging, sterically crowded substrates, while the ‘easy’ substrates can be transformed more readily in the presence of catalysts with standard NHC ligands (4a–b). Interestingly, catalysts 4c bearing Me2IMes ligand seemed the least utile.

These results show again [85] that different catalysts can be optimal for different applications, and that even small, sometimes incremental, variations can result in substantial changes in reactivity.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online. Figure S1: Atomic Displacement Parameters (ADPs) and the labeling of atoms in 4b and 4c; Figure S2: Atomic Displacement Parameters (ADPs) and the labeling of atoms in 4d; Figure S3: Atomic Displacement Parameters (ADPs) and the labeling of atoms in 4e for two molecules in asymmetric unit (4e′ and 4e′′); Figure S4: Overlay of molecules from the 4a structure (black) with the 4b (magenta), 4c structure (blue), 4d structure (green), 4f structure (grey), 4e′ structure (red) and 4e′′ (yellow) and 4g (grey; Figure S5: Atomic Displacement Parameters; Table S1: Experimental details for 4b–4e structures; Table S2: Experimental details for the CuClPCy3 measurement.

Author Contributions

Experiments and data analysis, M.P. and J.C.-J.; naphthyl ligands synthesis, R.D.; X-Ray measurements, M.M. and K.W. Vbur calculation, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and K.G.; writing—review and editing, A.K., R.D. and K.G.; supervision, A.K. and K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the OPUS project financed by the National Science Centre, Poland on the basis of a decision DEC-2014/15/B/ST5/02156.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. K.G. is an advisory board member of the Apeiron Synthesis company, the producer of catalyst 4a–b.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Wanzlick H.-W., Schönherr H.-J. Direct Synthesis of a Mercury Salt-Carbene Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1968;7:141–142. doi: 10.1002/anie.196801412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Öfele K. 1,3-Dimethyl-4-imidazolinyliden-(2)-pentacarbonylchrom ein neuer übergangsmetall-carben-komplex. J. Organomet. Chem. 1968;12:P42–P43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)88691-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arduengo A.J., Harlow R.L., Kline M. A stable crystalline carbene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:361–363. doi: 10.1021/ja00001a054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gómez-Suárez A., Nelson D.J., Nolan S.P. Quantifying and understanding the steric properties of N-heterocyclic carbenes. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:2650–2660. doi: 10.1039/C7CC00255F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cazin C., editor. N-Heterocyclic Carbenes in Transition Metal Catalysis and Organocatalysis. Volume 32. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2011. pp. 1–336. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grubbs R.H., Wenzel A.G., O’Leary D.J., Khosravi E. Handbook of Metathesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grela K. Olefin Metathesis: Theory and Practice. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michrowska A., Grela K. Quest for the ideal olefin metathesis catalyst. Pure Appl. Chem. 2008;80:31–43. doi: 10.1351/pac200880010031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson A.W., Merckling N.G. Polymeric Bicyclo-(2, 2, 1)-2-Heptene. 2,721,189. U.S. Patent. 1955 Oct 18;

- 10.Banks R.L., Bailey G.C. Olefin Disproportionation. A New Catalytic Process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev. 1964;3:170–173. doi: 10.1021/i360011a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Natta G., Dall’Asta G., Mazzanti G. Stereospecific Homopolymerization of Cyclopentene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1964;3:723–729. doi: 10.1002/anie.196407231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schrock R.R., Murdzek J.S., Bazan G.C., Robbins J., Dimare M., O’Regan M. Synthesis of molybdenum imido alkylidene complexes and some reactions involving acyclic olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:3875–3886. doi: 10.1021/ja00166a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwab P., Grubbs R.H., Ziller J.W. Synthesis and Applications of RuCl2(CHR‘)(PR3)2: The Influence of the Alkylidene Moiety on Metathesis Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:100–110. doi: 10.1021/ja952676d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ackermann L., Fürstner A., Weskamp T., Kohl F.J., Herrmann W.A. Ruthenium carbene complexes with imidazolin-2-ylidene ligands allow the formation of tetrasubstituted cycloalkenes by RCM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:4787–4790. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)00919-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J., Stevens E.D., Nolan S.P., Petersen J.L. Olefin Metathesis-Active Ruthenium Complexes Bearing a Nucleophilic Carbene Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2674–2678. doi: 10.1021/ja9831352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scholl M., Trnka T.M., Morgan J.P., Grubbs R.H. Increased ring closing metathesis activity of ruthenium-based olefin metathesis catalysts coordinated with imidazolin-2-ylidene ligands. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:2247–2250. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)00217-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [(accessed on 15 April 2020)]; Available online: https://pmc.umicore.com/en/products/umicore-grubbs-catalyst-m2a-c848/

- 18.Scholl M., Ding S., Lee C.W., Grubbs R.H. Synthesis and activity of a new generation of ruthenium-based olefin metathesis catalysts coordinated with 1,3-dimesityl-4,5-dihydroimidazol-2-ylidene ligands. Org. Lett. 1999;1:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol990909q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [(accessed on 15 April 2020)]; Available online: https://catalysts.evonik.com/product/catalysts/downloads/homogeneous_catalysts_evonik.pdf.

- 20. [(accessed on 15 April 2020)]; Available online: https://pmc.umicore.com/en/products/umicore-grubbs-catalyst-m2/

- 21. [(accessed on 15 April 2020)]; Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sial/901755?lang=pl®ion=PL.

- 22. [(accessed on 15 April 2020)]; Available online: https://www.strem.com/catalog/v/44-0758/59/ruthenium_502964-52-5.

- 23. [(accessed on 15 April 2020)]; Available online: https://www.strem.com/catalog/v/44-0770/59/ruthenium_928795-51-1.

- 24.Yang L., Mayr M., Wurst K., Buchmeiser M.R. Novel metathesis catalysts based on ruthenium 1,3-dimesityl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidin-2-ylidenes: Synthesis, structure, immobilization, and catalytic activity. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:5761–5770. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Despagnet-Ayoub E., Grubbs R.H. A ruthenium olefin metathesis catalyst with a four-membered N-heterocyclic carbene ligand. Organometallics. 2005;24:338. doi: 10.1021/om049092h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fürstner A., Ackermann L., Gabor B., Goddard R., Lehmann C.W., Mynott R., Stelzer F., Thiel O.R. Comparative investigation of ruthenium-based metathesis catalysts bearing N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2001;7:3236–3253. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010803)7:15<3236::AID-CHEM3236>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dinger M.B., Nieczypor P., Mol J.C. Adamantyl-Substituted N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands in Second-Generation Grubbs-Type Metathesis Catalysts. Organometallics. 2003;22:5291. doi: 10.1021/om034062k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yun J., Marinez E.R., Grubbs R.H. A new ruthenium-based olefin metathesis catalyst coordinated with 1, 3-dimesityl-1, 4, 5, 6-tetrahydropyrimidin-2-ylidene: synthesis, X-ray structure, and reactivity. Organometallics. 2004;23:4172. doi: 10.1021/om034369j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vehlow K., Maechling S., Blechert S. Ruthenium metathesis catalysts with saturated unsymmetrical N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. Organometallics. 2006;25:25. doi: 10.1021/om0508233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledoux N., Allaert B., Pattyn S., Vander Mierde H., Vercaemst C., Verpoort F. N,N′-Dialkyl- and N-Alkyl-N-mesityl-Substituted N-Heterocyclic Carbenes as Ligands in Grubbs Catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:4654. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tornatzky J., Kannenberg A., Blechert S. New catalysts with unsymmetrical N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:8215. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30256j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamad F.B., Sun T., Xiao S., Verpoort F. Olefin metathesis ruthenium catalysts bearing unsymmetrical heterocylic carbenes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013;257:2274–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paradiso V., Costabile C., Grisi F. Ruthenium-based olefin metathesis catalysts with monodentate unsymmetrical NHC ligands. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018;14:3122–3149. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.14.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dinger M.B., Mol J.C. High turnover numbers with ruthenium-based metathesis catalysts. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2002;344:671–677. doi: 10.1002/1615-4169(200208)344:6/7<671::AID-ADSC671>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banti D., Mol J.C. Degradation of the ruthenium-based metathesis catalyst [RuCl2 (CHPh)(H2IPr)(PCy3)] with primary alcohols. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004;689:3113. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2004.07.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clavier H., Urbina-Blanco C.A., Nolan S.P. Indenylidene Ruthenium Complex Bearing a Sterically Demanding NHC Ligand: An Efficient Catalyst for Olefin Metathesis at Room Temperature. Organometallics. 2009;28:2848–2854. doi: 10.1021/om900071t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallenkamp D., Fürstner A. Stereoselective Synthesis ofE,Z-Configured 1,3-Dienes by Ring-Closing Metathesis. Application to the Total Synthesis of Lactimidomycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9232–9235. doi: 10.1021/ja2031085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bieniek M., Bujok R., Stepowska H., Jacobi A., Hagenkötter R., Arlt D., Jarzembska K.N., Makal A., Woźniak K., Grela K. New air-stable ruthenium olefin metathesis precatalysts derived from bisphenol S. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006;691:5289–5297. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2006.07.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arduengo A.J., Davidson F., Dias H.V.R., Goerlich J.R., Khasnis D., Marshall W.J., Prakasha T.K. An Air Stable Carbene and Mixed Carbene “Dimers. ” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:12742–12749. doi: 10.1021/ja973241o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kadyrov R., Rosiak A., Tarabocchia J., Szadkowska A., Bieniek M., Grela K. Catalysis of Organic Reactions. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2008. New concepts in designing ruthenium-based second generation olefin metathesis catalysts and their application; pp. 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ginzburg Y., Lemcoff N. Olefin Metathesis. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2014. Hoveyda-Type Olefin Metathesis Complexes; pp. 437–451. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grela K., Harutyunyan S., Michrowska A. A Highly Efficient Ruthenium Catalyst for Metathesis Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:4038–4040. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021104)41:21<4038::AID-ANIE4038>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michrowska A., Bujok R., Harutyunyan S., Sashuk V., Dolgonos G., Grela K., Dolgonos G.A. Nitro-Substituted Hoveyda−Grubbs Ruthenium Carbenes: Enhancement of Catalyst Activity through Electronic Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9318–9325. doi: 10.1021/ja048794v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grela K. Ruthenium Complexes as (Pre)catalysts for Metathesis Reactions. 6,867,303. U.S. Patent. 2005 Mar 15;

- 45.Bieniek M., Michrowska A., Gułajski Ł., Grela K. A Practical Larger Scale Preparation of Second-Generation Hoveyda-Type Catalysts. Organometallics. 2007;26:1096–1099. doi: 10.1021/om0607651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhan Z.-Y.J. Recyclable Ruthenium Catalysts for Metathesis Reactions. 7,632,772. U.S. Patent. 2009 Dec 15;

- 47.Lindner F., Friedrich S., Hahn F. Total Synthesis of Complex Biosynthetic Late-Stage Intermediates and Bioconversion by a Tailoring Enzyme from Jerangolid Biosynthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2018;83:14091–14101. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.8b02047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stellfeld T., Bhatt U., Kalesse M. Synthesis of the A,B,C-Ring System of Hexacyclinic Acid. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3889–3892. doi: 10.1021/ol048720o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shu C., Zeng X., Hao M.-H., Wei X., Yee N.K., Busacca C.A., Han Z., Farina V., Senanayake C.H. RCM Macrocyclization Made Practical: An Efficient Synthesis of HCV Protease Inhibitor BILN. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1303–1306. doi: 10.1021/ol800183x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farina V., Shu C., Zeng X., Wei X., Han Z., Yee N.K., Senanayake C.H. Second-Generation Process for the HCV Protease Inhibitor BILN 2061: A Greener Approach to Ru-Catalyzed Ring-Closing Metathesis†. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2009;13:250–254. doi: 10.1021/op800225f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Q.-Y., Chaturvedi P.R., Luesch H. Process development and scale-up total synthesis of largazole, a potent class i histone deacetylase inhibitor. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018;22:190–199. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.7b00352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Breen C.P., Parrish C., Shangguan N., Majumdar S., Murnen H., Jamison T.F., Bio M.M. A scalable membrane pervaporation approach for continuous flow olefin metathesis. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.0c00061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tracz A., Matczak M., Urbaniak K., Skowerski K. Nitro-grela-type complexes containing iodides–robust and selective catalysts for olefin metathesis under challenging conditions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015;11:1823–1832. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.11.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marx V.M., Sullivan A.H., Melaimi M., Virgil S.C., Keitz B.K., Weinberger D.S., Bertrand G., Grubbs R.H. Cyclic alkyl amino carbene (caac) ruthenium complexes as remarkably active catalysts for ethenolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:1919–1923. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gawin R., Tracz A., Chwalba M., Kozakiewicz A., Trzaskowski B., Skowerski K. Cyclic Alkyl Amino Ruthenium Complexes—Efficient Catalysts for Macrocyclization and Acrylonitrile Cross Metathesis. ACS Catal. 2017;7:5443–5449. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b00597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmid T.E., Dumas A., Colombel-Rouen S., Crévisy C., Baslé O., Mauduit M. From environmentally friendly reusable ionic-tagged ruthenium-based complexes to industrially relevant homogeneous catalysts: Toward a sustainable olefin metathesis. Synlett. 2017;28:773–798. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bieniek M., Bujok R., Milewski M., Arlt D., Kajetanowicz A., Grela K. Making the family portrait complete: Synthesis of electron withdrawing group activated Hoveyda-Grubbs catalysts bearing sulfone and ketone functionalities. J. Organomet. Chem. 2020;918:121276. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2020.121276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bieniek M., Samojłowicz C., Sashuk V., Bujok R., Śledź P., Lugan N., Lavigne G., Arlt D., Grela K. Rational design and evaluation of upgraded Grubbs/Hoveyda olefin metathesis catalysts: Polyfunctional benzylidene ethers on the test bench. Organometallics. 2011;30:4144–4158. doi: 10.1021/om200463u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eivgi O., Sutar R.L., Reany O., Lemcoff N.G. Bichromatic photosynthesis of coumarins by UV filter-enabled olefin metathesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017;359:2352–2357. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201700316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ivry E., Frenklah A., Ginzburg Y., Levin E., Goldberg I., Kozuch S., Lemcoff N.G., Tzur E. Light- and thermal-activated olefin metathesis of hindered substrates. Organometallics. 2018;37:176–181. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tzur E., Szadkowska A., Ben-Asuly A., Makal A., Goldberg I., Woźniak K., Grela K., Lemcoff N.G. Studies on electronic effects in O-, N- and S-chelated ruthenium olefin-metathesis catalysts. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2010;16:8726–8737. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Żukowska K., Szadkowska A., Pazio A.E., Woźniak K., Grela K. Thermal switchability of N-chelating Hoveyda-type catalyst containing a secondary amine ligand. Organometallics. 2012;31:462–469. doi: 10.1021/om2011062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gawin A., Pump E., Slugovc C., Kajetanowicz A., Grela K. Ruthenium amide complexes—Synthesis and catalytic activity in olefin metathesis and in ring-opening polymerisation. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018;2018:1766–1774. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201800251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Monsaert S., Lozano Vila A., Drozdzak R., Van Der Voort P., Verpoort F. Latent olefin metathesis catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3360–3372. doi: 10.1039/b902345n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eivgi O., Lemcoff N.G. Turning the light on: Recent developments in photoinduced olefin metathesis. Synthesis. 2018;50:49–63. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luan X., Mariz R., Gatti M., Costabile C., Poater A., Cavallo L., Linden A., Dorta R. Identification and characterization of a new family of catalytically highly active imidazolin-2-ylidenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6848–6858. doi: 10.1021/ja800861p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vieille-Petit L., Luan X., Mariz R., Blumentritt S., Linden A., Dorta R. A new class of stable, saturated N-heterocyclic carbenes with N-naphthyl substituents: Synthesis, dynamic behavior, and catalytic potential. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009;2009:1861–1870. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200900010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vieille-Petit L., Clavier H., Linden A., Blumentritt S., Nolan S.P., Dorta R. Ruthenium olefin metathesis catalysts with N-heterocyclic carbene ligands bearing N-naphthyl side chains. Organometallics. 2010;29:775–788. doi: 10.1021/om9009697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winter P., Hiller W., Christmann M. Access to Skipped Polyene Macrolides through Ring-Closing Metathesis: Total Synthesis of the RNA Polymerase Inhibitor Ripostatin B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:3396–3400. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ritter T., Hejl A., Wenzel A.G., Funk T.W., Grubbs R.H. A standard system of characterization for olefin metathesis catalysts. Organometallics. 2006;25:5740–5745. doi: 10.1021/om060520o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Garber S.B., Kingsbury J.S., Gray B.L., Hoveyda A.H. Efficient and Recyclable Monomeric and Dendritic Ru-Based Metathesis Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8168–8179. doi: 10.1021/ja001179g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rivard M., Blechert S. Effective and Inexpensive Acrylonitrile Cross-Metathesis: Utilisation of Grubbs II Precatalyst in the Presence of Copper(I) Chloride. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003;2003:2225–2228. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200300215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vieille-Petit L., Luan X., Gatti M., Blumentritt S., Linden A., Clavier H., Nolan S.P., Dorta R. Improving Grubbs’ II type ruthenium catalysts by appropriately modifying the N-heterocyclic carbene ligand. Chem. Commun. 2009;25:3783–3785. doi: 10.1039/b904634h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Samojłowicz C., Bieniek M., Grela K. Ruthenium-based olefin metathesis catalysts bearing N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:3708–3742. doi: 10.1021/cr800524f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barbasiewicz M., Szadkowska A., Makal A., Jarzembska K.N., Grela K., Woźniak K. Is the Hoveyda-Grubbs Complex a Vinylogous Fischer-Type Carbene? Aromaticity-Controlled Activity of Ruthenium Metathesis Catalysts. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2008;14:9330–9337. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Falivene L., Credendino R., Poater A., Petta A., Serra L., Oliva R., Scarano V., Cavallo L. SambVca A Web Tool for Analyzing Catalytic Pockets with Topographic Steric Maps. Organometallics. 2016;35:2286–2293. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chatterjee A.K., Choi T.-L., Sanders D.P., Grubbs R.H. A general model for selectivity in olefin cross metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11360–11370. doi: 10.1021/ja0214882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mukherjee N., Planer S., Grela K. Formation of tetrasubstituted C–C double bonds via olefin metathesis: Challenges, catalysts, and applications in natural product synthesis. Org. Chem. Front. 2018;5:494–516. doi: 10.1039/C7QO00800G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Diver S.T., Griffiths J.R. Ene-yne metathesis. In: Grela K., editor. Olefin Metathesis: Theory and Practice. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2014. pp. 153–185. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grotevendt A.G.D., Lummiss J.A.M., Mastronardi M.L., Fogg D.E. Ethylene-Promoted versus Ethylene-Free Enyne Metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15918–15921. doi: 10.1021/ja207388v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schmid T.E., Bantreil X., Citadelle C.A., Slawin A., Cazin C.S.J. Phosphites as ligands in ruthenium-benzylidene catalysts for olefin metathesis. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:7060–7062. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10825e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guidone S., Blondiaux E., Samojłowicz C., Gułajski Ł., Kędziorek M., Malinska M., Pazio A., Wozniak K., Grela K., Doppiu A., et al. Catalytic and Structural Studies of Hoveyda-Grubbs Type Pre-Catalysts Bearing Modified Ether Ligands. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012;354:2734–2742. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201200385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Broggi J., Urbina-Blanco C.A., Clavier H., Leitgeb A., Slugovc C., Slawin A., Nolan S.P. The Influence of Phosphane Ligands on the Versatility of Ruthenium-Indenylidene Complexes in Metathesis. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2010;16:9215–9225. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lecourt C., Dhambri S., Allievi L., Sanogo Y., Zeghbib N., Ben Othman R., Lannou M.-I., Sorin G., Ardisson J. Natural products and ring-closing metathesis: synthesis of sterically congested olefins. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2018;35:105–124. doi: 10.1039/C7NP00048K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bieniek M., Michrowska A., Usanov D.L., Grela K. In an attempt to provide a user’s guide to the galaxy of benzylidene, alkoxybenzylidene, and indenylidene ruthenium olefin metathesiss catalysts. Chem. A Eur. J. 2008;14:806–818. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.