Abstract

Background

Parents use apps to access information on child health, but there are no standards for providing evidence-based advice, support, and information. Well-developed apps that promote appropriate infant feeding and play can support healthy growth and development. A 2015 systematic assessment of smartphone apps in Australia about infant feeding and play found that most apps had minimal information, with poor readability and app quality.

Objective

This study aimed to systematically evaluate the information and quality of smartphone apps providing information on breastfeeding, formula feeding, introducing solids, or infant play for consumers.

Methods

The Google Play store and Apple App Store were searched for free and paid Android and iPhone Operating System (iOS) apps using keywords for infant feeding, breastfeeding, formula feeding, and tummy time. The apps were evaluated between September 2018 and January 2019 for information content based on Australian guidelines, app quality using the 5-point Mobile App Rating Scale, readability, and suitability of health information.

Results

A total of 2196 unique apps were found and screened. Overall, 47 apps were evaluated, totaling 59 evaluations for apps across both the Android and iOS platforms. In all, 11 apps had affiliations to universities and health services as app developers, writers, or editors. Furthermore, 33 apps were commercially developed. The information contained within the apps was poor: 64% (38/59) of the evaluations found no or low coverage of information found in the Australian guidelines on infant feeding and activity, and 53% (31/59) of the evaluations found incomplete or incorrect information with regard to the depth of information provided. Subjective app assessment by health care practitioners on whether they would use, purchase, or recommend the app ranged from poor to acceptable (median 2.50). Objective assessment of the apps’ engagement, functionality, aesthetics, and information was scored as acceptable (median 3.63). The median readability score for the apps was at the American Grade 8 reading level. The suitability of health information was rated superior or adequate for content, reading demand, layout, and interaction with the readers.

Conclusions

The quality of smartphone apps on infant feeding and activity was moderate based on the objective measurements of engagement, functionality, aesthetics, and information from a reliable source. The overall quality of information on infant feeding and activity was poor, indicated by low coverage of topics and incomplete or partially complete information. The key areas for improvement involved providing evidence-based information consistent with the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council’s Infant Feeding Guidelines. Apps supported and developed by health care professionals with adequate health service funding can ensure that parents are provided with credible and reliable resources.

Keywords: breast feeding, bottle feeding, infant food, readability, consumer health information, breastfeeding, mobile apps, smartphones

Introduction

Background

Parents of a new baby can access a wealth of information and support from the internet through multiple electronic devices [1-3]. There is evidence to suggest, however, that web-based advice is not always evidence-based, even in the critical area of infant nutrition [4]. Smartphone ownership has expanded worldwide, with 81% of Australian adults and 97% of Australians aged 18 to 34 years owning a smartphone in 2018 [5]. Recent national data suggest that 46% of Australian adults accessed the internet for health information [6]. In 2017, 84% of Australian adults used mobile phones to access the internet, exceeding access through laptop computers (69%) and desktop computers (54%) [7]. Furthermore, smartphone ownership has now surpassed the ownership of desktop and laptop computers [8].

The proliferation of web-based health information sources is reflected by the growing literature for health care professionals discussing and advising the use of new technology [9-12]. Studies have shown that parents and pregnant women trusted hospital, government, and university websites as accurate, regulated, useful, and current sources of pregnancy and parenting information [13,14]. Parents in a video education study on introducing solid foods preferred the internet as a source of information for infant nutrition and felt that public authorities were important information providers [15].

Governments and nonprofit organizations have developed smartphone apps to promote and enhance breastfeeding [16-20]. A recent content analysis of social support in 31 breastfeeding apps found that the most common topics were managing breastfeeding problems (informational support) and locating where to express or breastfeed in public (instrumental support) [21]. Increasingly, clinical trials have assessed mobile health (mHealth) and smartphone apps as interventions to promote and support breastfeeding among mothers and their partners [22-24] through text messaging, goal setting, access to information and videos, provision of online support groups, and troubleshooting breastfeeding difficulties. A review by Tang et al [25] on digital interventions that support breastfeeding found that client communication systems to communicate breastfeeding information, facilitate communication, and provide on-demand information services through text messages, phone calls, email, smartphone apps, and websites may improve breastfeeding adherence.

In Australia, government health services use mHealth apps to support routine child and family health nursing practice in fields such as child literacy and development [26,27], immunization [28], and safe infant sleeping [29]. An early childhood obesity prevention trial will test an app developed for parents and caregivers [30] to be integrated into an Australian statewide pregnancy coaching service [31]. Clearly, apps used as part of routine care must meet practice standards for providing understandable, reliable, current, and evidence-based information independent of commercial associations. This highlights the need for evidence-based, well-developed, and updated apps.

Despite the proliferation of apps and their increasing popularity with parents, their quality may not have kept pace with their quantity. Earlier research on infant feeding apps and websites available in Australia found that 78% of the apps were of poor quality, with deficits in the breadth and completeness of information, author credibility, and readability [4]. A similar review of infant feeding apps in China found that most apps advertised infant formula and parenting products and rated poorly on the availability of information, author credibility, and transparency in disclosing advertising policy, app ownership, and app sponsorship [32]. A recent review of mHealth apps for parents of infants in neonatal intensive care units found that smartphone apps were functional but had low quality and credibility, with only 2 apps rated good by nurse and information scientist reviewers and only 5 apps deemed trustworthy [33].

Since the 2015 study [4], the Australian ownership of smartphones has increased from 64% to 81%, and the proportion of users accessing the internet through mobile phones has increased from 42% to 84% [7,34]. In 2017, there were 325,000 health, fitness, and medical apps available [35]. The increasing interest in infant feeding and physical activity apps indicated by popular search queries in the Google search engine (Multimedia Appendix 1) demonstrates the need to systematically assess and update the current smartphone app landscape. Furthermore, there is a continual turnover of smartphone apps, with several apps from the 2015 study [4] subsequently removed from distribution.

Aim

Given the rapid expansion of digital technology into the realm of child health, this study aimed to evaluate the quality of information on infant nutrition and physical activity currently available to Australian parents via smartphone apps. It updates and expands the 2015 systematic assessment, examining the comprehensibility, suitability, and readability of information in free and paid apps available in Australia.

Methods

Study Design

This study used systematic methods to identify, select, and evaluate infant feeding and activity apps that were available in Australia between August 2018 and January 2019. It assessed aspects of their quality and utility using validated and purpose-specific instruments to replicate and update an earlier study [4]. Full details of the methods are given in Multimedia Appendix 2, and evaluation tools are described in Multimedia Appendix 3.

Stage 1: App Selection

Smartphone apps were identified by searching app platforms from the two largest smartphone operating systems: App Store for iPhone Operating System (iOS; Apple Inc) and Google Play for Android (Google LLC). The search terms included variations in infant feeding, baby feeding, breastfeeding, formula feeding, bottle feeding, baby food, baby weaning, infant activity, and tummy time.

We used the search engine Google Play on a desktop for searching Android apps [36]. It was not possible to search the App Store on a desktop [37]; therefore, we conducted all App Store searches on the authors’ iOS smartphones.

Members of the research team screened all located apps for eligibility: 4 authors screened iOS apps, and 2 authors screened Android apps. The first author cross-checked all apps. Apps were reviewed if they met the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements regarding the inclusion of apps in the study were discussed until consensus was reached.

The inclusion criteria for selection included apps written in English, targeted at parents of infants up to one year of age, and containing information on at least one of the following topics: milk feeding behaviors (breastfeeding, formula feeding, expressing breast milk, frequency or timing of feeding, and correct preparation of infant formula), solid food feeding behaviors (age of introduction, types of food introduced, repeated exposure, varied exposure, and reducing exposure to unhealthy food and beverages), or infant activity (tummy time, infant play, and movement).

In the selection stage, we excluded apps that were inaccessible with dead or broken links; were formatted as electronic books, news, magazines, podcasts, blogs, or word documents; had restricted access; did not have an English language option or were machine-translated into English; were games or gaming apps, or contained stolen or farmed content [38] from other apps or websites. Examples of excluded apps are given in Multimedia Appendix 2. Apps whose main function was to monitor or time infant care tasks, without providing any educational information on infant feeding and activity, were also excluded.

Stage 2: App Evaluation

In this stage, reviewers evaluated the selected apps on several dimensions (coverage and depth of information, quality, data security, and app accessibility, suitability, and readability) using a range of instruments. The reviewers rated all instruments using the Research Electronic Data Capture platform (Vanderbilt University) [39].

Coverage and Depth of Information

Accurate coverage (referred to hereafter as coverage) and depth of information were evaluated using a quantitative tool developed for the 2015 study [4], based on the Australian government’s guidelines on infant feeding [40] and physical activity [41], with permission from the tool’s authors. It has 9 topics with 22 subtopics on encouraging and supporting breastfeeding, initiating breastfeeding, establishing and maintaining breastfeeding, managing common breastfeeding problems, expressing and storing breast milk, breastfeeding in specific situations, preparing and using infant formula, introducing solid foods, and encouraging infant activity.

Coverage, defined as the breadth of the subtopics correctly covered in each app, was scored as either correct (+1), incorrect (−1), not addressed (0), or not applicable. Depth, defined as the completeness of information covered in each subtopic, was scored as partially complete (+0.5), complete (+1), or incompletely addressed or incorrect information (0). If the subtopic was scored incorrectly for coverage, it was automatically scored as incorrect for depth.

We also rated each app’s coverage using the criteria from the Health-Related Website Evaluation Form [42]. Coverage was summarized as excellent (≥90%), adequate (75%-89%), or poor (≤74%). Depth was summarized as complete (100%), partial (50%-99%), or low or no (≤49%) completeness.

App Quality

App quality was evaluated using the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS) [43], which was not available at the time of the original study in 2015. The MARS is a 23-item quality rating tool that uses a 5-point rating scale, scored as 1 (inadequate), 2 (poor), 3 (acceptable), 4 (good), and 5 (excellent), with 4 objective scales on engagement (5 domains on interesting, fun, or interactive content), functionality (4 domains on app navigation and logical usability), aesthetics (3 domains on graphic design and visual appeal), and information quality (7 domains on credibility of source). The MARS also includes 1 subjective quality scale incorporating the user’s judgment on their likelihood of recommending, using, and purchasing the app and a personal 5-star rating. This is reported separately as the subjective MARS score.

A final measurement of app quality, the objective MARS score, is calculated as a 5-star rating using the mean from the scores from the objective (engagement, functionality, aesthetics, and information quality) scales.

App Usability

The authors of the previous study [4] developed 2 additional scales not included in other app assessment tools available or found by the authors during the app evaluation stage. These were data security, with items assessing data encryption and privacy, and accessibility, incorporating multilanguage options, one-handed functionality, and availability of help guides. We added these scales to the MARS tool to create the modified MARS score, which we calculated separately from the objective MARS score.

Suitability of Information

The appropriateness of the information on the apps was evaluated using the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) tool [44]. The SAM is a 22-item validated instrument that assesses content, literacy level, graphics, layout, interaction with readers, and cultural appropriateness. Each item is scored as superior (+2), adequate (+1), not suitable (0), or not applicable. The sum of the scores of the items generates a final score summarized as superior (70%-100%), adequate (40%-69%), or not suitable (0%-39%) appropriateness of information for the target audience.

The hypothetical target audience used in the app evaluation was Australians with a year 3 to 4 reading level, with or without a multicultural background [45].

Readability

The SAM also assesses the readability, or grade level of written text, measured using the Flesch-Kincaid (F-K) [46] and the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) [47] tools. The reviewers assessed the readability by typing a section of writing from each app into an online readability calculator [48] that calculated F-K and SMOG scores; they also used Microsoft Word software (2010 and later; Microsoft Corporation) [49] to generate an alternative F-K score. Each reviewer selected the passage of the text they assessed.

The F-K and SMOG scores are reported as American reading grades. The Australian federal government’s Plain English guidelines [45] recommend writing for a reading level of Australian school year 3 to 4, the equivalent of American Grade 3 to 4 reading level. The South Australian state government’s health literacy guidelines recommend writing for a reading level of Australian year 8 [50].

Readability is an item in the SAM. Using the SAM, we summarized F-K and SMOG readability scores as superior (Grade 5 and lower reading level), adequate (Grade 6 to 8 reading level), or not suitable (Grade 9 or higher reading level).

Interrater Reliability

We undertook interrater reliability (IRR) testing with 2 or more reviewers assessing at least 20% of the selected apps using all rating tools. We tested apps that were available on both iOS and Android platforms. Discrepancies were discussed until reviewers reached a consensus on their final ratings.

IRR was calculated for the readability scores, MARS scores, SAM, and the evaluation of information content using Krippendorff α (α), which is appropriate when there are missing or incomplete data. Using Krippendorff standards for data reliability, .667≤α<.80 was accepted as tentatively reliable, and α≥.80 was accepted as reliable.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corporation). Descriptive results on the ratings from the various instruments are reported as median (IQR). We calculated the correlations among different measures of readability using the Spearman rank-order correlation. We also compared the 5-point rating scores in the MARS tool with the user ratings of the apps presented in the Apple App Store and Google Play Store using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Krippendorff α was calculated using the KALPHA macro for IBM SPSS [51]. Significant values were indicated at P<.05.

Ethics Approval

This study did not require ethics approval.

Results

Stage 1: Smartphone App Selection

Screening Process

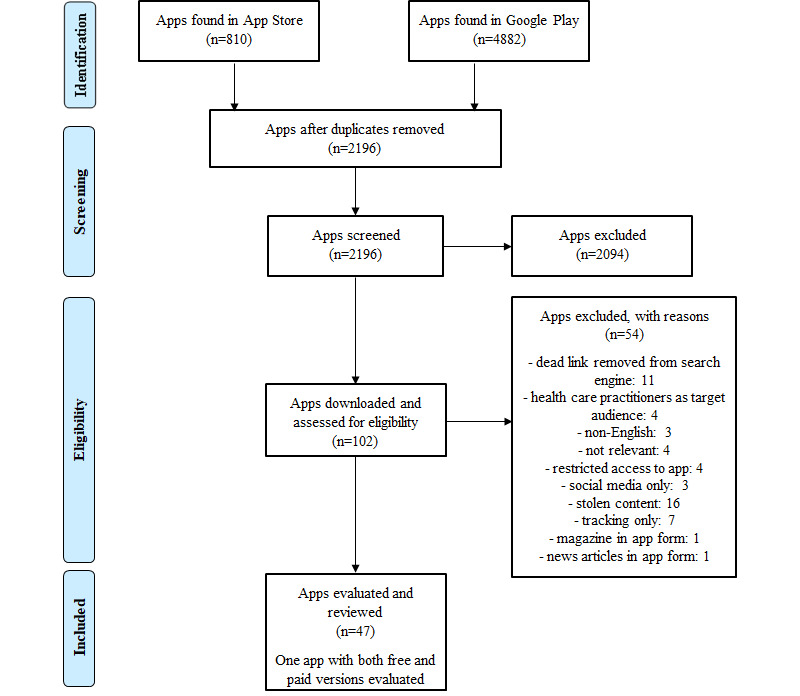

App searches were performed between August and September 2018. A total of 5692 apps were identified for screening (Figure 1), with 3496 duplicates removed and 2196 apps screened for potential inclusion. After screening, 102 apps were downloaded for evaluation. Of these, 54 were excluded, and 47 were reviewed between September 2018 and January 2019. The apps included in this study are described in Multimedia Appendix 4. We undertook 59 evaluations for 47 apps, including 27 and 32 evaluations on iOS and Android smartphones, respectively.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram of smartphone app selection process.

Description of the Selected Apps

Overall, 1 app was developed with nationally competitive research funding, 10 apps were developed by the government or had government affiliations, 3 apps were developed by universities or had university affiliations, and 33 were commercial.

Furthermore, 2 apps were trialed with surveys [52,53]. One app was used in a randomized controlled trial but was not objectively evaluated [54]. Of the 47 apps, 35 apps (74%) were free to access, although 12 of these required payment to remove advertisements; access additional content, functions, and information; or access the full app without preview restrictions. Overall, 12 of the 47 apps (26%) were only accessible by purchase. A total of 10 apps were, as reported by app developers, available in languages other than English (eg, Arabic, Bosnian, Chinese, Danish, Dutch, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, and Vietnamese).

Of the 47 apps, 32 apps (68%) were located through infant feeding–related search terms, 13 (28%) through terms related to introduction to solids, and 25 (53%) through infant activity–related terms. Several apps were found through multiple keyword search terms, for example, in search terms related to infant feeding and introduction to solids.

Stage 2: Smartphone App Evaluation

Interrater Reliability

Overall, 12 of the 47 apps (26%) were evaluated independently by 2 different reviewers using iOS and Android platforms (Multimedia Appendix 4) to assess the IRR.

There was reliable IRR agreement (α≥.80) for the objective MARS ratings and the depth of information content in the infant activity subtopic. There was acceptable IRR agreement (.667≤α<.80) for the modified MARS ratings, depth of information content in the infant feeding subtopic, and coverage of information content in the infant activity subtopic.

Although the IRR scores were relatively low on several instruments, the reviewers discussed discrepancies and the interpretation of evaluation criteria to ensure greater unanimity in future scoring. The following tables present results for 59 evaluations, taking into account the 12 apps rated by the 2 reviewers.

Coverage and Depth of Information

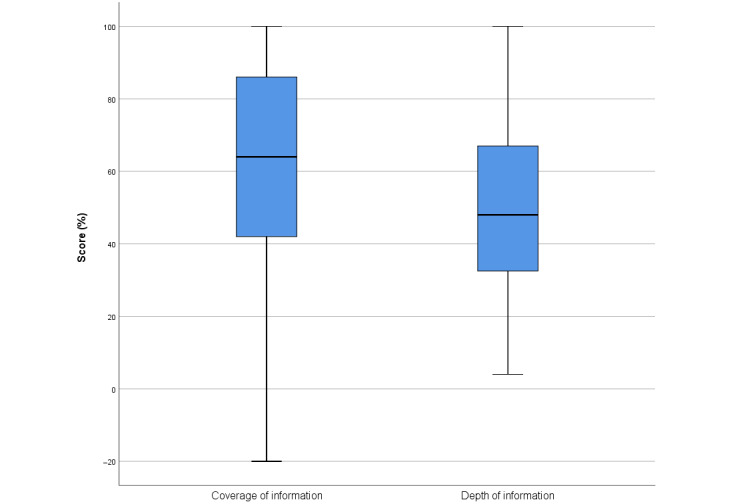

The coverage and depth of information provided by most apps were relatively poor (Table 1). Assessment with the content evaluation tool (Multimedia Appendix 3) found a median coverage, or breadth of subtopics correctly covered, of 64% (IQR 40%-87%; Figure 2). The depth, or completeness of information covered in the subtopics, had a median rating of 48% (IQR 32%-67%). The majority of app evaluations (31/59, 53%) had low or no completeness of subtopics (Tables 2 and 3). Furthermore, two-thirds of the app evaluations (38/59, 64%) showed that the apps had poor depth of information, and only 7% (4/59) of the app evaluations rated information as complete (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 1.

The quantitative coverage and depth of information based on Australian infant feeding and physical activity guidelines in all apps (N=59 evaluations of 47 apps).

| Information quality | Median (%) | IQR (%) | Range (%) | Number of evaluations, n | |

| Coverage | |||||

|

|

All apps | 64 | 40-87 | −20 to 100a | 59 |

|

|

Infant feeding apps | 67 | 40-80 | 7 to 100 | 37 |

|

|

Introduction to solid foods apps | 50 | 0-88 | −100 to 100a | 37 |

|

|

Infant activity apps | 100 | 50-100 | 0 to 100 | 33 |

| Depth | |||||

|

|

All apps | 48 | 32-67 | 4 to 100 | 59 |

|

|

Infant feeding apps | 38 | 21-50 | 0 to 86 | 37 |

|

|

Introduction to solid foods apps | 38 | 6-50 | 0 to 100 | 37 |

|

|

Infant activity apps | 50 | 50-88 | 0 to 100 | 33 |

aResults with negative scores indicate apps with overall negative scoring for topics reported incorrectly.

Figure 2.

Quantitative evaluation of the coverage of information and the depth of information across all subtopics on infant feeding, introduction to solids, and physical activity in apps. A total of 59 evaluations were conducted for 47 apps. Median and IQR reported.

Table 2.

The qualitative evaluation of coverage of information based on Australian infant feeding and physical activity guidelines in all apps (N=59 evaluations of 47 apps).

| Coverage of information | Poor, n (%) | Adequate, n (%) | Excellent, n (%) | Number of evaluations, n |

| All apps | 38 (64) | 8 (14) | 13 (22) | 59 |

| Infant feeding apps | 25 (68) | 6 (16) | 6 (16) | 37 |

| Introduction to solid foods apps | 26 (70) | 2 (5) | 9 (24) | 37 |

| Infant activity apps | 10 (29) | 0 (0) | 24 (71) | 33 |

Table 3.

The qualitative evaluation of depth of information based on Australian infant feeding and physical activity guidelines in all apps (N=59 evaluations of 47 apps).

| Depth of information | Low or no completeness, n (%) | Partial completeness, n (%) | Complete, n (%) | Number of evaluations, n |

| All apps | 31 (53) | 24 (41) | 4 (7) | 59 |

| Infant feeding apps | 27 (73) | 10 (27) | 0 (0) | 37 |

| Introduction to solid foods apps | 26 (70) | 9 (24) | 2 (5) | 37 |

| Infant activity apps | 7 (21) | 8 (56) | 19 (24) | 33 |

Detailed reporting of the coverage and depth of information within each subtopic are shown in Multimedia Appendix 4. Subtopics pertinent to clinicians are described below under Coverage of Information in Subtopics and Depth of Information in Subtopics and in Table 4.

Table 4.

The depth (completeness) of information in the subtopics reported (N=59 evaluations of 47 apps).

| Completeness of information | Complete, n | Partially complete, n | Incorrect or incomplete, n | Number of evaluations, na | |

| Encouraging and supporting breastfeeding | |||||

|

|

Breastfeeding as the physiological norm | 16 | 11 | 5 | 32 |

|

|

Protection and promotion of breastfeeding | 6 | 14 | 1 | 21 |

|

|

Breastfeeding education for parents | 12 | 12 | 1 | 25 |

| Initiating breastfeeding | |||||

|

|

Physiology of breast milk and breastfeeding | 4 | 17 | 1 | 22 |

|

|

The first breastfeed | 3 | 6 | 5 | 14 |

| Establishing and maintaining breastfeeding | |||||

|

|

Difficulty establishing breastfeeding | 1 | 10 | 2 | 13 |

|

|

Factors affecting establishment of breastfeeding | 1 | 10 | 5 | 16 |

|

|

Monitoring an infant’s progress | 8 | 14 | 4 | 26 |

|

|

Maternal nutrition | 4 | 11 | 7 | 22 |

| Breastfeeding, common problems, and their management | |||||

|

|

Maternal factors affecting breastfeeding | 3 | 15 | 1 | 19 |

|

|

Infant factors affecting breastfeeding | 1 | 12 | 3 | 16 |

| Expressing and storing breast milk | |||||

|

|

Expressing breast milk | 5 | 13 | 5 | 23 |

|

|

Feeding with expressed breast milk | 5 | 5 | 1 | 11 |

|

|

Storage of expressed breast milk | 10 | 5 | 9 | 24 |

| Breastfeeding in special situations | |||||

|

|

Tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs | 2 | 13 | 6 | 21 |

| Infant formula | |||||

|

|

Preparing infant formula | 2 | 4 | 7 | 13 |

|

|

Using infant formula | 6 | 6 | 4 | 16 |

|

|

Special infant formula | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 |

| Introducing solids | |||||

|

|

When should solid foods be introduced? | 7 | 15 | 13 | 35 |

|

|

What foods should be introduced? | 3 | 3 | 21 | 27 |

|

|

Foods and beverages most suitable for infants or foods that should be used in care | 4 | 14 | 9 | 27 |

|

|

Healthy foods in the first 12 months (continued exposure and opportunity to sample a wide variety of healthy foods) | 10 | 9 | 5 | 24 |

| Infant activity | |||||

|

|

Encouraging physical activity for infants from birth for healthy development | 16 | 11 | 1 | 28 |

|

|

Advice on types of infant physical activity and movements for development, including reaching and grasping; pulling and pushing; moving their head, body, and limbs during daily routines; and supervised floor play, including tummy time | 10 | 13 | 2 | 25 |

aNot all apps included information on all subtopics.

Coverage of Information in Subtopics

Information coverage was lowest in apps related to infant feeding and introduction to solid foods. Infant activity subtopics were more likely to provide correct advice, with only 1 app reporting incorrect advice on encouraging infant activity for healthy development.

For information on infant feeding, incorrect advice was most frequently reported in the following subtopics: maternal nutrition during breastfeeding (3 apps), expressing and storing breast milk (3 apps across topics), breastfeeding in specific situations (tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use; 3 apps), and preparing and using infant formula (2-4 apps).

For information on introducing solid foods, incorrect advice was most frequently reported on the time to introduce solid foods (9 apps), first foods to introduce (15 apps), foods and beverages most suitable for infants (5 apps), and exposure to healthy foods for the first 12 months (3 apps).

Depth of Information in Subtopics

The ratings on the depth of information were lowest in apps related to infant feeding and introduction to solid foods (Table 4).

In apps on infant feeding, the depth of information was best reported for special infant formula, with 3 apps reporting partially complete information and 1 app reporting complete information. Incomplete or incorrect information was reported in all other subtopics across infant feeding apps. Partially complete information on infant feeding was more frequently reported than complete information.

In apps on introduction to solid foods, incomplete or incorrect information was reported in all subtopics. For appropriate first foods, incomplete or incorrect information was reported more frequently than correct information. Partially complete information on when to introduce solid foods and foods and beverages most suitable for infants was more frequently reported than complete information.

Most apps on infant activity reported partially complete information on encouraging infant activity for healthy development and complete information on the types of different infant physical activities or movements for development.

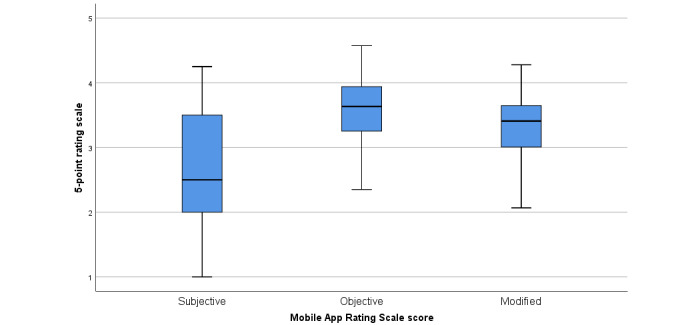

App Quality

Table 5 and Figure 3 present the results of app quality evaluation using the MARS tool, which rates different objective and subjective dimensions of app quality.

Table 5.

Mobile App Rating Scale quality ratings (N=59 evaluations of 47 apps).

| MARSa evaluation scores | Median | IQR | Range | Apps rated good, n | Apps rated excellent, n |

| Engagement subscale | 3.00 | 2.60-3.40 | 1.80-4.20 | 12 | 0 |

| Functionality subscale | 4.25 | 3.75-4.75 | 2.0-5.0 | 26 | 24 |

| Aesthetics subscale | 4.33 | 4.0-4.67 | 2.0-5.0 | 32 | 10 |

| Information quality subscale | 3.60 | 3.0-3.80 | 1.75 -4.8 | 30 | 1 |

| Objective MARS scoreb | 3.63 | 3.24-3.99 | 2.07-4.28 | 38 | 1 |

| Data security subscale | 2.33 | 1.0-3.33 | 1.0-5.0 | 5 | 3 |

| Accessibility subscale | 3.00 | 2.0-3.67 | 1.0-5.0 | 18 | 1 |

| Modified MARS scorec | 3.41 | 2.99-3.64 | 2.35-4.57 | 25 | 0 |

| Subjective MARS score | 2.50 | 2.0-3.5 | 1.0-4.25 | 20 | 1 |

aMARS: Mobile App Rating Scale.

bObjective MARS score=mean of engagement subscale+functionality subscale+aesthetics subscale+information quality subscale.

cModified MARS score=mean of objective MARS score+data security subscale+accessibility subscale.

Figure 3.

Quantitative evaluation of the 5-point Mobile App Rating Scale scores.

Overall, the quality of the apps was found to be mixed. Ratings were typically higher for items included in the objective score (especially the aesthetics and functionality subscales) than the subjective score. The inclusion of the 2 items on data security and accessibility lowered the median quality ratings of the apps, especially given that most apps rated poorly on data security (median 2.33; IQR 1.00-3.33).

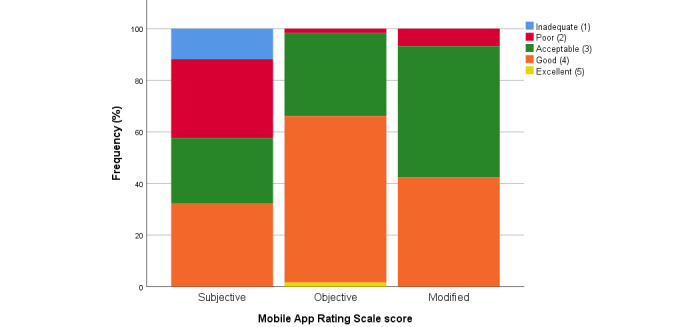

Figure 4 indicates that very few apps were rated excellent across all items on the MARS scales, although higher proportions were rated good, especially for the objective subscales.

Figure 4.

Qualitative evaluation of the 5-point Mobile App Rating Scale scores.

On the subjective MARS scale, out of 47 apps, there were 21 apps (45%) that the reviewer reported they would never recommend to others or recommend to very few people. Furthermore, reviewers, who were child health clinicians or health researchers, reported that they would not pay to access 30 of the 47 apps (64%), although 4 of these were free, developed by the government or a community health organization.

A total of 31 apps reported the authors’ qualifications with health expertise, including doctors, nurses, lactation consultants, midwives, psychologists, physiotherapists, physical therapists, speech language therapists, health promotion officers, dietitians, nutritionists, occupational therapists, and sport therapists. As noted, 33 apps were developed by commercial entities, including 15 owned or developed by health care practitioners and 9 that consulted with health practitioners.

More detailed findings on the MARS and scores are reported in Multimedia Appendix 4.

We compared the MARS quality scores with the user-rated scores from the Apple App Store and Google Play Store reported in January 2019 (Multimedia Appendix 4). There was no significant correlation between the users’ app ratings and any of the MARS scores, but there was a significant correlation among the subjective, modified, and objective MARS scores (P<.001 each, 2-tailed).

Suitability of Infomation

Overall, 42% apps (25/59 evaluations) were rated superior for suitability of health information, 54% apps (32/59 evaluations) were rated as adequate, and 3% apps (2/59 evaluations) were not suitable. More detailed findings on the SAM scores are reported in Multimedia Appendix 4.

Few apps were rated superior on the cultural appropriateness items, although most apps were considered adequate on the cultural match for an Australian setting. A few apps were considered superior when they were suitable for an Australian setting and featured information for a non-Western culture and demography. Few apps presented information with representation of images and examples demonstrating cultural diversity. The 3 apps that contained culturally diverse images were all developed outside of Australia (but were available in English); the target populations were Croatian (Baby Food Chart), mainland Chinese and Hong Kong Chinese (Info for Nursing Mum), and Maori and Pacific Islander families (Raising Children).

Many apps provided instructions for taking clear and specific actions, with topics subdivided to motivate users—for example, in apps on introducing solid foods, information was subdivided into sections on the types of food to introduce, how to prepare food, how to feed infants, and how to encourage dietary variety. Most information was provided in a question-and-answer format, which was rated as adequate reader interaction.

Readability

The reading grade of app content was consistent across the tools used (Table 6).

Table 6.

Readability scores of infant feeding and activity apps.

| American grade level reading score | Median | IQR |

| Flesch-Kincaid score (online tool) | 8 | 6-10 |

| Flesch-Kincaid score (Microsoft Word) | 8 | 6-9 |

| Simple Measure of Gobbledygook score | 8 | 6-9 |

There was a good correlation among reading grade scores using the 3 readability measures (P<.001; Multimedia Appendix 4).

However, very few apps met the Australian federal government’s recommended level for written health information of Grade 4 reading level or below: either 3 apps (using the F-K online tool), 4 apps (F-K in Word), or 5 apps (SMOG). A majority of apps met the South Australian government’s recommended level of Grade 8 level reading and below: 24 and 32 apps using F-K online tool and Microsoft Word tool, respectively, and 34 apps using the SMOG tool.

There was a low correlation among reading grades rated as not suitable, adequate, or superior in the SAM tool and the overall SAM score on adequacy of health information (r=0.25; P=.06).

Comparison With the 2015 Study

The 2015 study [4] used similar methods to evaluate infant feeding apps for parents. Although this study aimed to replicate it, some of the methods of analysis and presentation differed. Table 7 presents comparable findings between the 2 studies.

Table 7.

Comparison of evaluation outcomes used in the original 2015 study and this study.

| Instrument | This study (47 apps and 59 evaluations) | 2015 study (46 apps and 46 evaluations) | ||

| Content evaluation tool (%), median (IQR) | ||||

|

|

Coverage of information | 64 (40-87) | 65 (58-71) | |

|

|

Depth of information | 48 (32-67) | Reported graphically | |

| App quality using Quality Component Scoring System (scored out of 100%) | ||||

|

|

Median (IQR) | Not undertaken | 49 (41-60) | |

|

|

Proportion rated poor (<50% score) | Not undertaken | 91 | |

| App quality using Mobile App Rating Scale (scored out of 5 points) | ||||

|

|

Objective scale | |||

|

|

|

Median (IQR) | 3.63 (3.24-3.99) | Not developed at the time of writing |

|

|

|

Proportion rated poor (%, ≤2.5 score) | 2 | Not developed at the time of writing |

|

|

Modified scale | |||

|

|

|

Median (IQR) | 3.41 (2.99-3.64) | Not developed at the time of writing |

|

|

|

Proportion rated poor (%, ≤2.5 score) | 7 | Not developed at the time of writing |

|

|

Subjective scale | |||

|

|

|

Median (IQR) | 2.50 (2.0-3.5) | Not developed at the time of writing |

|

|

|

Proportion rated poor (%, ≤2.5 score) | 54 | Not developed at the time of writing |

| Suitability Assessment of Material (%) | ||||

|

|

Superior overall (70%-100%) | 44 | 15 | |

|

|

Adequate overall (40%-69%) | 53 | 39 | |

|

|

Not suitable (0%-39%) | 3 | 42 | |

| Readability, median (IQR) | ||||

|

|

Flesch-Kincaid online tool | 8 (6-10) | 8 (7-10) | |

|

|

Flesch-Kincaid Word tool | 8 (6-9) | 8 (7-10) | |

|

|

Simple Measure of Gobbledygook | 8 (6-9) | 7 (7-8) | |

Discussion

Principal Findings

This study evaluated 47 apps on infant feeding and physical activity and found that the information content within these apps was largely poor for coverage and depth of information presented. This study updated a systematic assessment of 46 apps available from 2013 to 2014, which similarly found poor quality information for parents [4]. Although the quality of apps, rated through the MARS, improved since the previous study, the credibility of advice did not improve; of the 59 evaluations, almost two-thirds reported poor coverage of information, and over half the app evaluations reported incorrect or incomplete information on the topics addressed.

Reviewers identified information contrary to the Australian guidelines on infant feeding [40] and physical activity [41] in 21 apps. Many of these apps were developed outside of Australia, that is, in America, the United Kingdom, and the European Union, where the official guidelines may be different from those in Australia. Although 1 app with incorrect information was developed in Australia and involved health care professionals, it was developed by a medical device company whose promotion of its breast pumps likely interfered with the provision of correct breastfeeding information.

The results using the MARS tool were largely positive. In this systematic assessment, the apps were rated as moderately engaging, functional, and visually appealing, and these apps clearly reported whether the information came from credible sources. One strength of the MARS tool is that it provides a multidimensional overview of app characteristics, all of which contribute to the user’s experience of an app and the capacity to learn from it. In this case, most apps rated well on engagement, functionality, and aesthetics. However, in MARS, the quality and quantity of the information content constitute only 2 out of the 7 domains that contribute to the final score. Therefore, the information items were inadequate to reflect the importance of the content in this context. In other words, the MARS tool gave relatively little weight to the quality and accuracy of the information provided to consumers about infant nutrition and activity.

Therefore, although many apps were qualitatively evaluated as good to excellent on the objective and modified MARS score, the information contained within these apps was poor. This is reflected in the subjective scores for the apps, with a median of 2.50 and most apps falling between inadequate and acceptable. Reviewers reported that nearly half of all apps were poor or inadequate for recommending to others.

Brown et al [55,56] systematically reviewed the content of pregnancy apps against the Australian national recommendations on healthy eating for pregnancy. Similar to this study, they found that the apps were of moderate quality (mean objective MARS score was 3.05 [SD 0.66] and 3.52 [SD 0.58] for iOS and Android apps, respectively), with the functionality scale (mean 3.32 [SD 0.66]and 4.06 [SD 0.67], for iOS and Android apps, respectively) rated highest. These reviews also found incorrect and potentially harmful information in 3 apps about avoiding alcohol during pregnancy, fasting, restricting dairy products, and using dairy alternatives to meet calcium requirements.

Similarly, a review by Richardson et al [33] on apps for parents of infants in neonatal intensive care units highlighted the inconsistencies in quality ratings according to the method used. They identified a discrepancy between high app quality ratings using the MARS tool and those using the Trust It or Trash It tool [57] for evaluating clearly reported sources of health information.

Although most apps were rated suitable for their potential users on many dimensions, they scored less on readability and cultural appropriateness. Using the readability tools, only a handful of apps met the Australian government’s requirement of year 4 reading level (3-5 apps, depending on what readability tool was used), although a majority met the less stringent South Australian government’s requirement of year 8 level. However, the reviewers’ SAM ratings suggested that most apps used a suitable vocabulary and appropriate style and ordering.

Limitations

The app market is highly dynamic, and this study captured a cross-sectional snapshot of infant feeding and play apps available at one time point. Several apps in the previous study [4] were not available for download in 2018 and 2019. Even in this study, some apps had been removed from the marketplace by the time of writing, demonstrating the volatility of this information source. This changing availability makes the process of systematically reviewing apps challenging and potentially limited if key resources are not available during the selection phase.

Changes in the app search engines impacted the search process. The removal of the iOS App Store feature on iTunes in September 2017 [37] meant that the reviewers could only search using an iPhone instead of a desktop computer and prevented reliable double-checking of apps found for screening. As with other mHealth reviews conducted after September 2017 [56], double-checking of apps available in the App Store was conducted on Fnd, a web-based search tool [58], which reduces the flexibility of consumers to search for apps on desktop and synchronize the app download to their smartphone.

Search optimization, which refers to optimizing smartphone apps for visibility in search engines and browsing [59], also affected the types of apps found. To reflect the external validity of apps found by users searching through a smartphone app search engine, the authors did not include handsearching or searching for apps outside of the app search engine. Oversaturation of search engines with apps that are malware, spam, counterfeit, or contain copyrighted and farmed content [60-62] results in excessive number of apps; over 5000 apps were found during screening (Figure 1). This affects the apps found through Google Play, as search results are limited to 250 apps per search; therefore, if irrelevant apps are found in keyword searches and listed in the first 250 apps found, this is a nonoptimal search strategy, and relevant apps will be displaced from the search and not included in the analysis. This excessive number of apps caused relevant apps to be displaced by irrelevant apps; for example, a nongovernment organization–developed app on tummy time (Red Nose Safe Sleeping) was available on both search engines, but poor search optimization for keywords resulted in the app not being found through Google Play searches.

This study used keywords in English and evaluated apps available with English as the main language option. We acknowledge the multicultural background of the Australian population and the need for apps suitable for culturally and linguistically diverse parents [63], and a limitation of our study may exclude app users without English language proficiency (approximately 3.5% of Australians aged 15-49 years in 2016, data from Australian Bureau of Statistics [64]). Of the 102 relevant apps screened (Figure 1), only 3 were excluded for not being available in English. It is likely, however, that non-English–speaking parents may search for non-English sites. Zhao et al [32] used the 360 App Store and Chinese language keywords to conduct similar research, focusing on apps used by non-English–speaking parents. This shows the potential for this approach to include different app marketplaces and language search terms to explore apps available for different groups of parents.

Interrater Reliability

The IRR results (Multimedia Appendix 4) showed considerable discrepancies on some instruments. There was low agreement on readability scores, which may reflect the different passages of text selected for evaluation by the pairs of reviewers. This is likely as reading grade level was calculated using objective tools, rather than individual reviewer assessment.

Although there was acceptable agreement on the modified MARS scores between the pairs of reviewers, there was far less agreement on the subjective MARS items. This difference in scoring may reflect the reviewer’s perspectives (a dietitian researcher’s evaluation compared with a child and family health nurse clinician’s evaluation), affecting their likelihood of recommending an app and also their evaluation of its suitability for consumers using the SAM tool.

There was also mixed assessment on the coverage and depth of information on infant feeding, introduction to solids, and infant activity subtopics. Although reviewers evaluated content against the same government guidelines, they may have varied with regard to stringency in certain subtopics, such as deciding whether infants with appropriate signs of readiness can start solid foods between 4 and 6 months or if exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months was imperative [65]. Similarly, reviewers varied on how much information constituted complete or partially complete advice, affecting IRR.

Comparison With Prior Work

In replicating an earlier study of infant feeding and activity apps, we were able to compare the quality and content of apps available during 2018 to 2019 and those available 5 years earlier. The increased access to smartphones and the utilization of app-based health information among the Australian population over that time suggest that this study is highly relevant and timely. However, notwithstanding the increased suitability and functionality of these apps (measured with the SAM and MARS tools, respectively), the quality and accuracy of much of the information in apps have not greatly improved over time.

Since the 2015 study, this study identified growth in apps that are from reputable sources such as the government, universities, and health professionals: only 2 apps with university endorsements were found in the previous study [4] compared with 14 apps with university or government development or affiliation in this study. In addition, 3 apps were also used in research [52-54]. This finding indicates a positive transition of trustworthy sources that leverage the increased usage of technology and offer credible information to a wider population. This study also indicated that 9 apps were available in languages other than English, compared with none in the previous study. This demonstrates improved multilingual resources for a growing culturally diverse population.

This study was more comprehensive in that it looked at smartphone apps in Android and iOS, both paid and free to access. However, the previous study also looked at websites available on this topic, which might still be a widely used tool given the widespread use of Dr Google to search for pregnancy, birthing, and parenting information, which may not be accurate, credible, reliable, or safe [3,13,66-68].

Despite an increased proportion of apps published by reputable sources, this study also found relatively few good quality apps available. We reiterate the earlier recommendation [5] to establish a certified endorsement for apps similar to the Health on the Net Foundation Code of Conduct used on the website. This code of conduct is used to standardize the reliability of medical and health information available on the World Wide Web [69] and encourages website developers to maintain the quality standards of the organization. The 2015 study found that websites that subscribed to this code of conduct certificate had higher quality scores [4].

Only 2 apps (WebMD Baby and Pregnancy and Baby Tracker [formerly What to Expect]) were included across both studies, highlighting that the app marketplace changes continuously. A potential reason for the short shelf life of some apps could be the high maintenance cost required to keep the apps updated with the evolving smartphone operating systems. Intervention studies of health apps have reported technical issues with the implementation of their app [70], such as updates in the operating system or app impeding participant access [71-74]. This indicates that app functioning requires ongoing maintenance. This might be a challenge for apps that are developed with limited funding from universities or governments compared with commercial companies that often have higher budgets. Further research is required to explore factors that impact the shelf life of health-related apps and to develop suggestions on sustainable ways to leverage technology to share health-related information.

The use of the MARS tool, specifically developed for app evaluation, is a strength of this study. However, the MARS tool had not been published at the time of the 2015 study [4]. The original study adapted the Quality Component Scoring System to assess apps; however, this tool was originally developed to evaluate the quality of medical websites [75], and not all items were appropriate for apps.

Although the national infant feeding guidelines in Australia have remained consistent since the previous study [40], the uptake of this information has not improved. Research indicates that gaps exist in the current infant feeding practices. Begley et al’s [76] research with mothers, using focus groups, in Western Australia found that less than half of the participants had heard of the Australian Infant Feeding Guidelines or were aware that the recommended age for the introduction of solid foods was around 6 months; many participants believed that the guidelines were based on opinion rather than scientific research. A survey of mother-infant dyads in Western Australia and South Australia during 2010 to 2011 found that the feeding behaviors of participants fell short of Australian feeding guidelines, where although 93% of mothers initiated breastfeeding, only 42% of infants were breastfed to 6 months, and 97% of infants received solid food by 6 months [77].

Implications for Practice

It is well established that early childhood experiences have a significant impact on optimal child development [40]. Child and family health nurses in the community play an integral role in monitoring children’s growth and development and providing guidance and support to parents. Child and family health nurses and lactation consultants work in an environment that has limited staffing and financial resources.

Many parents live in isolation from extended families and turn to social networking sites for advice from peers for health-related information. Conflicting advice and lack of continuity of care from health professionals often adds to their confusion about how they should care for their children [78,79]. Increasingly, parents require direction and guidance to seek evidence-based educational resources. Parents seek information that is easily accessible and affordable. Information provided during consultation in the child and family health nurse clinics often dispels the parents’ concerns, but parents may be unable to absorb all the information at one time and often require educational resources that they can refer back to once they have gone home. Appropriate internet websites and smartphone apps are key to meeting this need.

Parents, particularly first-time parents, are bombarded with information from a variety of sources, especially from websites and smartphone apps. Although information evaluation tools supported by librarians, academics, and the government [57,80,81] for critically assessing health information quality can support the health and digital literacy of parents, these tools may not be widely known to the layperson. Similarly, clinicians who regularly support new parents often receive requests for advice about apps and cannot confidently provide a recommendation if they are unaware of app evaluation tools [82] or have insufficient time to evaluate apps. One way to overcome this challenge is to establish a trusted app or similar logo (logo similar to that of the Health on the Net Foundation Code of Conduct’s logo) or a repository of approved apps, such as the United Kingdom’s National Health Service Apps Library [83], which can be applied to evidence-based apps that do not promote particular products.

Conclusions

Improved functionality, suitability, and user engagement of smartphone apps in recent years are welcome developments for parents seeking guidance on infant feeding and activity. However, the high-quality content of apps is critical to good health outcomes. Assessment of available apps revealed that some provided very useful information, but there was wide disparity in reliability and consistency with evidence-based knowledge. Many apps provided additional information outside their focal topic or area of expertise; others offered information largely designed to promote their products. In some instances, this information was limited and did not provide comprehensive advice consistent with evidence-based guidelines.

Abbreviations

- F-K

Flesch-Kincaid

- iOS

iPhone Operating System

- IRR

interrater reliability

- MARS

Mobile App Rating Scale

- mHealth

mobile health

- SAM

Suitability Assessment of Materials

- SMOG

Simple Measure of Gobbledygook

Google Trends for app search key terms.

App search and evaluation protocol.

App evaluation tools used.

Supplementary tables and figures.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: EDW and ST designed the study and the main conceptual ideas. AT, CL, DS, HC, JJ, and EDW undertook the app searches on Google Play search engine or iOS App Store and evaluated the apps. HC undertook statistical analysis. HC, CR, EDW, and ST wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Wallwiener S, Müller M, Doster A, Laserer W, Reck C, Pauluschke-Fröhlich J, Brucker SY, Wallwiener CW, Wallwiener M. Pregnancy eHealth and mHealth: user proportions and characteristics of pregnant women using web-based information sources-a cross-sectional study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Nov;294(5):937–44. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4093-y.10.1007/s00404-016-4093-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy RA, Mullaney L, Reynolds CM, Cawley S, McCartney DM, Turner MJ. Preferences of women for web-based nutritional information in pregnancy. Public Health. 2017 Feb;143:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.10.028.S0033-3506(16)30330-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker LO, Mackert MS, Ahn J, Vaughan MW, Sterling BS, Guy S, Hendrickson S. e-Health and new moms: contextual factors associated with sources of health information. Public Health Nurs. 2017 Nov;34(6):561–8. doi: 10.1111/phn.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taki S, Campbell KJ, Russell CG, Elliott R, Laws R, Denney-Wilson E. Infant feeding websites and apps: a systematic assessment of quality and content. Interact J Med Res. 2015 Sep 29;4(3):e18. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.4323. https://www.i-jmr.org/2015/3/e18/ v4i3e18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silver L. Pew Research Center. Washington, DC, USA: Pew Research Center; 2019. Feb 5, [2019-03-18]. Smartphone Ownership Is Growing Rapidly Around the World, but Not Always Equally http://www.pewglobal.org/2019/02/05/smartphone-ownership-is-growing-rapidly-around-the-world-but-not-always-equally/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: Australian Government; 2018. Mar 28, [2019-03-20]. 8146.0 - Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2016-17 https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/8146.0 . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Communications and Media Authority. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: Australian Government; 2017. Nov, [2019-03-18]. Communications Report 2016-17 https://www.acma.gov.au/publications/2017-09/report/communications-report-2016-17 . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corbett P, Huggins K. Deloitte Australia. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu; 2018. [2019-03-18]. Mobile Consumer Survey 2019 - The Australian Cut https://www2.deloitte.com/au/mobileconsumer . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuman AJ. What's new in baby tech. Contemp Pediatr. 2016;37(3):37–40. https://www.contemporarypediatrics.com/article/what%E2%80%99s-new-baby-tech/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wellde PT, Miller LA. There's an app for that!: new directions using social media in patient education and support. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2016;30(3):198–203. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000177.00005237-201607000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aungst TD, Clauson KA, Misra S, Lewis TL, Husain I. How to identify, assess and utilise mobile medical applications in clinical practice. Int J Clin Pract. 2014 Feb;68(2):155–62. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudhry BM. Expecting great expectations when expecting. Mhealth. 2018;4:2. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2017.12.01. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2017.12.01.mh-04-2017.12.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pehora C, Gajaria N, Stoute M, Fracassa S, Serebale-O'Sullivan R, Matava CT. Are parents getting it right? A survey of parents' internet use for children's health care information. Interact J Med Res. 2015 Jun 22;4(2):e12. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.3790. https://www.i-jmr.org/2015/2/e12/ v4i2e12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hearn L, Miller M, Fletcher A. Online healthy lifestyle support in the perinatal period: what do women want and do they use it? Aust J Prim Health. 2013;19(4):313–8. doi: 10.1071/PY13039.PY13039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helle C, Hillesund ER, Wills AK, Øverby NC. Evaluation of an ehealth intervention aiming to promote healthy food habits from infancy-the Norwegian randomized controlled trial early food for future health. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019 Jan 3;16(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0763-4. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-018-0763-4 .10.1186/s12966-018-0763-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Australian Breastfeeding Association. Reach Health Promotion Innovations. Curtin University. Healthway Feed Safe. 2016. [2019-03-18]. http://www.feedsafe.net/

- 17.NHS National Health Service UK. [2019-03-18]. Baby Buddy https://www.nhs.uk/apps-library/baby-buddy/

- 18.Family Health Service. The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2016. [2019-03-18]. 'Info for Nursing Mum' Mobile App https://www.fhs.gov.hk/tc_chi/archive/files/bf_app.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Vision Philippines. Quezon City, Philippines: World Vision; 2018. [2019-03-18]. Mother-Baby Friendly Philippines to Turn Over its Reporting Platform to DOH https://www.worldvision.org.ph/stories/mother-baby-friendly-philippines-to-turn-over-its-reporting-platform-to-doh/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Midland Maternity Action Group. HealthShare Ltd. Midland District Health Boards BreastFedNZ. 2018. [2019-03-18]. http://www.breastfednz.co.nz/

- 21.Schindler-Ruwisch JM, Roess A, Robert RC, Napolitano MA, Chiang S. Social support for breastfeeding in the era of mhealth: a content analysis. J Hum Lact. 2018 Aug;34(3):543–55. doi: 10.1177/0890334418773302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jimenez-Zabala A. Clinical Trials. US National Library of Medicine; 2016. [2019-03-18]. Mother's Milk Messaging: Evaluation of a Bilingual APP to Support Initiation and Exclusive Breastfeeding in New Mothers (MMM) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02958475 . [Google Scholar]

- 23.White BK, Martin A, White JA, Burns SK, Maycock BR, Giglia RC, Scott JA. Theory-based design and development of a socially connected, gamified mobile app for men about breastfeeding (Milk Man) JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016 Jun 27;4(2):e81. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5652. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/2/e81/ v4i2e81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewkowitz AK, Anderson M. Clinical Trials. US National Library of Medicine; 2017. [2019-03-18]. Impact of a Smartphone Application on Postpartum Weight Loss and Breastfeeding Rates Among Low-income, Urban Women https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03167073 . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang K, Gerling K, Chen W, Geurts L. Information and communication systems to tackle barriers to breastfeeding: systematic search and review. J Med Internet Res. 2019 Sep 27;21(9):e13947. doi: 10.2196/13947. https://www.jmir.org/2019/9/e13947/ v21i9e13947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Resourcing Parents. Families NSW; 2019. [2019-04-10]. Love Talk Sing Read Play App http://ltsrp.resourcingparents.nsw.gov.au/home/resources . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deadly Tots. Families NSW; 2019. [2019-04-10]. Deadly Tots App http://deadlytots.com.au/Page/deadlytotsapp . [Google Scholar]

- 28.NSW Health. NSW Government; 2019. [2019-04-11]. New App Helps On-Time Vaccination for Kids https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/news/Pages/20181210_00.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- 29.Red Nose Australia healthdirect. 2019. [2019-04-10]. Red Nose Safe Sleeping App https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/red-nose-safe-sleeping-app .

- 30.Wen LM, Baur LA, Simpson JM, Rissel C, Wardle K, Flood VM. Effectiveness of home based early intervention on children's BMI at age 2: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2012 Jun 26;344:e3732. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3732. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22735103 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NSW Health. NSW Government; 2018. [2019-04-10]. $1.2 Million Bump for Healthy Mums and Bubs https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/news/Pages/20180723_01.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao J, Freeman B, Li M. How do infant feeding apps in China measure up? A content quality assessment. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017 Dec 6;5(12):e186. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8764. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2017/12/e186/ v5i12e186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richardson B, Dol J, Rutledge K, Monaghan J, Orovec A, Howie K, Boates T, Smit M, Campbell-Yeo M. Evaluation of mobile apps targeted to parents of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit: systematic app review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Apr 15;7(4):e11620. doi: 10.2196/11620. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/4/e11620/ v7i4e11620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Australian Communications and Media Authority. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: Australian Government; 2013. [2019-03-20]. Communications Report 2012-13 https://www.acma.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-08/Communications-report-2012-13.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 35.Research 2 Guidance. Berlin, Germany: Research2Guidance; 2017. [2019-03-20]. mHealth Economics 2017 – Current Status and Future Trends in Mobile Health https://research2guidance.com/product/mhealth-economics-2017-current-status-and-future-trends-in-mobile-health/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Google Play. California, USA: Google LLC; 2019. [2019-04-10]. Android Apps on Google Play https://play.google.com/store/apps . [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith J. ZDNet. CBS Interactive; 2017. Sep 13, [2019-01-23]. Apple's iTunes Removes iOS App Store From Desktop Version https://www.zdnet.com/article/apple-removes-ios-app-store-from-desktop-versions-of-itunes/ [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carr A. Research Guides - Austin Community College. Austin, Texas, USA: Austin Community College; 2019. [2019-09-19]. Content Farms: What is a Content Farm? https://researchguides.austincc.edu/contentfarms . [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1532-0464(08)00122-6 .S1532-0464(08)00122-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Health and Medical Research Council . Infant Feeding Guidelines: Information for Health Workers. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: Australian Government; 2012. [2019-01-21]. https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/n56_infant_feeding_guidelines.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 41.Department of Health. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: Australian Government; 2010. [2019-01-21]. Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the Early Years (Birth to 5 Years) http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/F01F92328EDADA5BCA257BF0001E720D/$File/Birthto5years_24hrGuidelines_Brochure.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 42.Health on the Net Foundation Per Carlbring: Nyheter. [2020-01-21]. Health-Related Web Site Evaluation Form https://www.carlbring.se/form/itform_eng.pdf .

- 43.Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, Zelenko O, Tjondronegoro D, Mani M. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015 Mar 11;3(1):e27. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3422. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2015/1/e27/ v3i1e27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doak C, Doak L, Root J. Aspirius Library. 2008. [2019-01-23]. Suitability Assessment of Materials For Evaluation of Health-Related Information for Adults http://aspiruslibrary.org/literacy/sam.pdf .

- 45.Australian Government . Digital Guides. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia; 2019. [2019-01-23]. Writing Style https://guides.service.gov.au/content-guide/writing-style/ [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kincaid PJ, Fishbourne Jr R, Rogers R, Chissom BS. ucf stars - University of Central Florida. Milington, Tennessee, USA: Institute for Simulation and Training; 1975. [2019-01-21]. Derivation Of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count And Flesch Reading Ease Formula) For Navy Enlisted Personnel https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1055&context=istlibrary . [Google Scholar]

- 47.McLaughlin HG. SMOG Grading - a new readability formula. J Read. 1969;12(8):639–46. https://ogg.osu.edu/media/documents/health_lit/WRRSMOG_Readability_Formula_G._Harry_McLaughlin__1969_.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 48.My Byline Media Readability Formulas. [2019-01-23]. http://www.readabilityformulas.com/

- 49.Microsoft Word Help Center . Microsoft Support. Washington, USA: Microsoft Corporation; 2019. [2019-01-23]. Get Your Document's Readability and Level Statistics https://support.office.com/en-us/article/test-your-document-s-readability-85b4969e-e80a-4777-8dd3-f7fc3c8b3fd2 . [Google Scholar]

- 50.SA Health. Adelaide, South Australia, Australia: Government of South Australia; 2013. [2019-01-21]. Policy Guideline: Guide for Engaging with Consumers and the Community https://tinyurl.com/y92z2o54 . [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Second Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manlongat D. University of Windsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Ontario, Canada: University of Windsor; 2017. [2020-04-02]. The Effects of Introducing Prenatal Breastfeeding Education in the Obstetricians' Waiting Rooms https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/7276/ [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wheaton N, Lenehan J, Amir LH. Evaluation of a breastfeeding app in rural Australia: prospective cohort study. J Hum Lact. 2018 Nov;34(4):711–20. doi: 10.1177/0890334418794181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taki S, Russell CG, Wen LM, Laws RA, Campbell K, Xu H, Denney-Wilson E. Consumer engagement in mobile application (app) interventions focused on supporting infant feeding practices for early prevention of childhood obesity. Front Public Health. 2019;7:60. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00060. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown HM, Bucher T, Collins CE, Rollo ME. A review of pregnancy apps freely available in the Google Play Store. Health Promot J Austr. 2019 Jun 21; doi: 10.1002/hpja.270. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown HM, Bucher T, Collins CE, Rollo ME. A review of pregnancy iPhone apps assessing their quality, inclusion of behaviour change techniques, and nutrition information. Matern Child Nutr. 2019 Jul;15(3):e12768. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Genetic Alliance . Trust It or Trash It? Washington DC, USA: Access To Credible Genetics Resource Network; 2009. [2019-09-06]. http://www.trustortrash.org/TrustorTrash.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mack Jeremy, Mack Ryann. Fnd. 2019. [2019-09-16]. https://fnd.io/

- 59.Samuel S. Search engine optimisation to improve your visibility online. In Pract. 2013 Jun 17;35(6):346–9. doi: 10.1136/inp.f2703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ahn A. Android Developers Blog. California, USA: Google LLC; 2018. Jan 30, [2019-09-05]. How We Fought Bad Apps and Malicious Developers in 2017 https://android-developers.googleblog.com/2018/01/how-we-fought-bad-apps-and-malicious.html . [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seneviratne S, Seneviratne A, Kaafar MA, Mahanti A, Mohapatra P. Spam mobile apps: characteristics, detection, and in the wild analysis. ACM Trans Web. 2017 Apr 10;11(1):1–29. doi: 10.1145/3007901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang H, Li H, Li L, Guo Y, Xu G. Why Are Android Apps Removed From Google Play?: A Large-Scale Empirical Study. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories; MSR'18; May 28-29, 2018; Gothenburg, Sweden. 2018. pp. 231–42. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hughson JP, Daly JO, Woodward-Kron R, Hajek J, Story D. The rise of pregnancy apps and the implications for culturally and linguistically diverse women: narrative review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018 Nov 16;6(11):e189. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.9119. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2018/11/e189/ v6i11e189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: Australian Government; 2016. [2020-03-03]. Proficiency in Spoken English/Language by Age by Sex (SA2+) http://stat.data.abs.gov.au/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ABS_C16_T08_SA . [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hetherington MM, Cecil JE, Jackson DM, Schwartz C. Feeding infants and young children. From guidelines to practice. Appetite. 2011 Dec;57(3):791–5. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.07.005.S0195-6663(11)00521-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lupton D. The use and value of digital media for information about pregnancy and early motherhood: a focus group study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016 Jul 19;16(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0971-3. https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-016-0971-3 .10.1186/s12884-016-0971-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fleming SE, Vandermause R, Shaw M. First-time mothers preparing for birthing in an electronic world: internet and mobile phone technology. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2014 Mar 19;32(3):240–53. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2014.886104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lynch C, Nikolova G. The internet: a reliable source for pregnancy and birth planning? A qualitative study. MIDIRS Midwifery Dig. 2015;25(2):193–9. https://repository.uwl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1682/ [Google Scholar]

- 69.Health On the Net. Geneva, Switzerland: Health on the Net Foundation; 2019. [2019-11-25]. The Commitment to Reliable Health and Medical Information on the Internet https://www.hon.ch/HONcode/Patients/Visitor/visitor.html . [Google Scholar]

- 70.Becker S, Miron-Shatz T, Schumacher N, Krocza J, Diamantidis C, Albrecht U. mHealth 2.0: experiences, possibilities, and perspectives. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2014 May 16;2(2):e24. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3328. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2014/2/e24/ v2i2e24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.White B, Giglia RC, White JA, Dhaliwal S, Burns SK, Scott JA. Gamifying breastfeeding for fathers: process evaluation of the Milk Man mobile app. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2019 Jun 20;2(1):e12157. doi: 10.2196/12157. https://pediatrics.jmir.org/2019/1/e12157/ v2i1e12157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Litterbach E, Russell CG, Taki S, Denney-Wilson E, Campbell KJ, Laws RA. Factors influencing engagement and behavioral determinants of infant feeding in an mHealth program: qualitative evaluation of the Growing healthy program. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017 Dec 18;5(12):e196. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8515. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2017/12/e196/ v5i12e196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taki S, Russell CG, Lymer S, Laws R, Campbell K, Appleton J, Ong K, Denney-Wilson E. A mixed methods study to explore the effects of program design elements and participant characteristics on parents' engagement with an mHealth program to promote healthy infant feeding: the Growing healthy program. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:397. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00397. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Venter W, Coleman J, Chan VL, Shubber Z, Phatsoane M, Gorgens M, Stewart-Isherwood L, Carmona S, Fraser-Hurt N. Improving linkage to HIV care through mobile phone apps: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018 Jul 17;6(7):e155. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8376. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2018/7/e155/ v6i7e155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martins EN, Morse LS. Evaluation of internet websites about retinopathy of prematurity patient education. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005 May;89(5):565–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.055111. http://bjo.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15834086 .89/5/565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Begley A, Ringrose K, Giglia R, Scott J. Mothers' understanding of infant feeding guidelines and their associated practices: a qualitative analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Mar 29;16(7):1141. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071141. http://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph16071141 .ijerph16071141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Magarey A, Kavian F, Scott JA, Markow K, Daniels L. Feeding mode of Australian infants in the first 12 months of life. J Hum Lact. 2016 Nov;32(4):NP95–104. doi: 10.1177/0890334415605835.0890334415605835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hesson A, Fowler C, Rossiter C, Schmied V. 'Lost and confused': parent representative groups' perspectives on child and family health services in Australia. Aust J Prim Health. 2017 Dec;23(6):560–6. doi: 10.1071/PY17072.PY17072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rossiter C, Fowler C, Hesson A, Kruske S, Homer CS, Kemp L, Schmied V. Australian parents’ experiences with universal child and family health services. Collegian. 2019 Jun;26(3):321–8. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Meriam Library. Chico, California, USA: California State University, Chico; 2004. [2020-03-02]. Evaluating Information – Applying the CRAAP Test https://library.csuchico.edu/sites/default/files/craap-test.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 81.US National Library of Medicine. US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health . Medline Plus. Bethesda, Maryland, USA: US National Library of Medicine; 2017. [2020-03-02]. Evaluating Health Information https://medlineplus.gov/evaluatinghealthinformation.html . [Google Scholar]

- 82.Skiba D. Evaluation tools to appraise social media and mobile applications. Inform. 2017 Sep 15;4(3):32. doi: 10.3390/informatics4030032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.NHS National Health Service UK. 2019. [2019-09-06]. NHS Apps Library https://www.nhs.uk/apps-library/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Google Trends for app search key terms.

App search and evaluation protocol.

App evaluation tools used.

Supplementary tables and figures.