Abstract

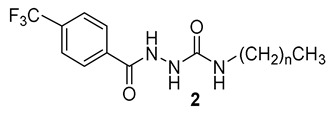

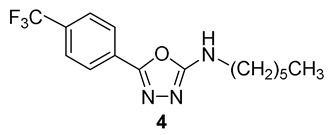

Based on the isosterism concept, we have designed and synthesized homologous N-alkyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamides (from C1 to C18) as potential antimicrobial agents and enzyme inhibitors. They were obtained from 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide by three synthetic approaches and characterized by spectral methods. The derivatives were screened for their inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) via Ellman’s method. All the hydrazinecarboxamides revealed a moderate inhibition of both AChE and BuChE, with IC50 values of 27.04–106.75 µM and 58.01–277.48 µM, respectively. Some compounds exhibited lower IC50 for AChE than the clinically used drug rivastigmine. N-Tridecyl/pentadecyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamides were identified as the most potent and selective inhibitors of AChE. For inhibition of BuChE, alkyl chain lengths from C5 to C7 are optimal substituents. Based on molecular docking study, the compounds may work as non-covalent inhibitors that are placed in a close proximity to the active site triad. The compounds were evaluated against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and nontuberculous mycobacteria (M. avium, M. kansasii). Reflecting these results, we prepared additional analogues of the most active carboxamide (n-hexyl derivative 2f). N-Hexyl-5-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-amine (4) exhibited the lowest minimum inhibitory concentrations within this study (MIC ≥ 62.5 µM), however, this activity is mild. All the compounds avoided cytostatic properties on two eukaryotic cell lines (HepG2, MonoMac6).

Keywords: antimycobacterial activity, acetylcholinesterase inhibition, butyrylcholinesterase inhibition, cytostatic properties, hydrazides, 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide

1. Introduction

The development of novel drugs involves various medicinal chemistry approaches, including the widely used isostere/bioisostere strategy [1]. A bioisostere is a molecule that results from the exchange of an original atom or a group of atoms for an alternative, roughly similar atom or group of atoms. Based on physical and/or chemical similarity, isosteric compounds may share analogous pharmacological behavior. Usually, it is a way to ameliorate disadvantageous features of current drugs and drug candidates, e.g., low activity, drug resistance, toxicity, poor pharmacokinetic profile, etc. It is also possible to establish an original bioactivity [2,3].

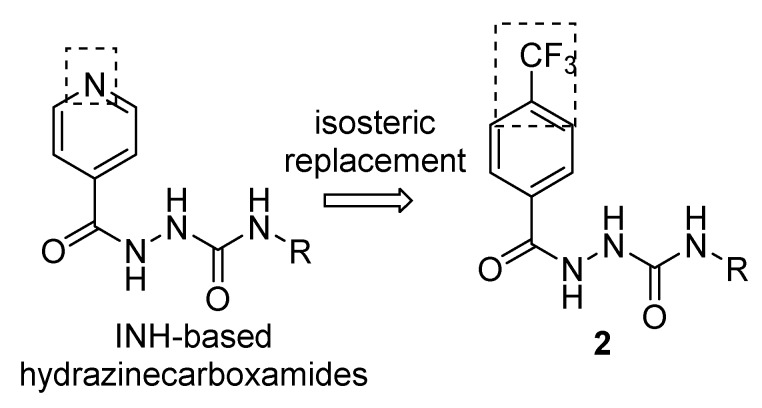

In our previous study, we successfully implemented a bioisosteric concept for isoniazid-based hydrazones where the antimycobacterial drug isoniazid (isonicotinoylhydrazide, INH) was replaced by 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide [4]. What is more, N2-substituted derivatives of 4-(trifluoro-methyl)benzohydrazide (1) have been reported as antibacterial molecules effective against both Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria [4,5,6], Gram-positive cocci including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, yeasts and molds [4], anticonvulsants [7,8], cytostatic/antiproliferative and cytotoxic [9,10], metal-chelating [5,10] or anti-inflammatory agents [9]. That is why we applied this approach of also for biologically active N-alkyl-2-isonicotinoylhydrazine-1-carboxamides [11,12] using replacement of INH scaffold by isosteric 4-(trifluoromethyl)hydrazide 1 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Design of the 1,2-diacylhydrazines 2 based on 4-(trifluoromethyl)hydrazide 1 scaffold.

Then, we screened novel molecules for their antimicrobial and cytostatic properties. Moreover, since many scaffolds carrying aromatic trifluoromethyl group have showed inhibition of acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase (AChE and BuChE) [13,14,15], we tested novel hydrazides also for this bioactivity.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

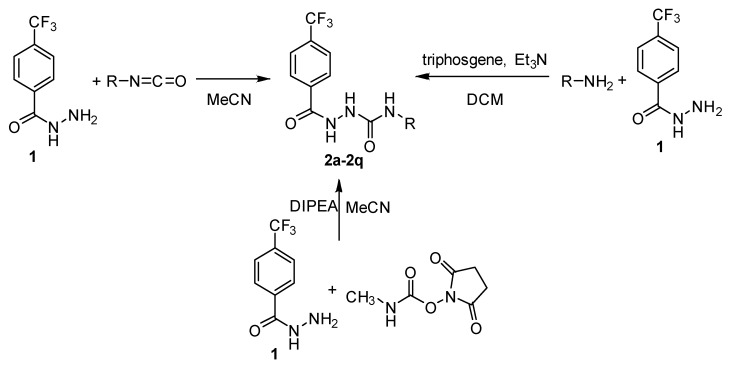

Analogously to our previous works [11,12], hydrazine-1-carboxamides were obtained using three synthetic approaches. Most of the derivatives (2b–2i, 2k, 2l, 2n, 2p–2q) were prepared from commercially available isocyanates and the hydrazide 1 in acetonitrile. This reaction (method A) is simple, quick and it provides high yields, up to quantitative ones (89–99%). For the synthesis of N-decyl, tridecyl and pentadecyl derivatives 2i, 2m and 2o, where the required isocyanates were not commercially available, we prepared them in situ using the corresponding amines and triphosgene in the presence of triethylamine (TEA) under a nitrogen atmosphere, followed by addition of the hydrazide 1. The yields of this method B ranged from 78% to 91%. Finally, for the synthesis of N-methyl derivative 1a, N-succinimidyl N-methylcarbamate in the presence of a non-nucleophilic tertiary base (N,N-diisopropylethylamine, DIPEA) was used as a non-toxic and crystalline methyl isocyanate substitute (method C with a good yield of 77%). An overview of the synthetic approaches used is depicted in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of N-alkyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamides 2a–2q (R: n-alkyl from C1 to C16 and C18; DIPEA: N,N-diisopropylethylamine; DCM: dichloromethane).

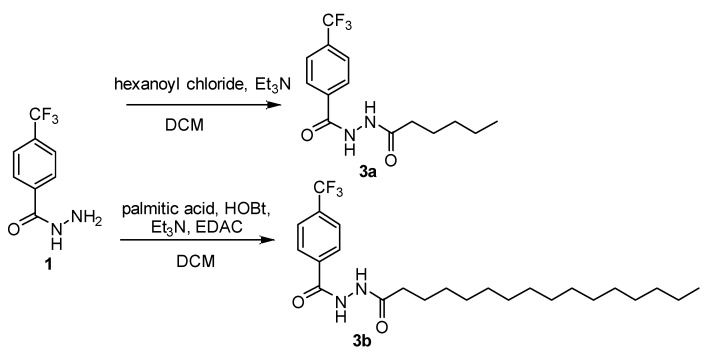

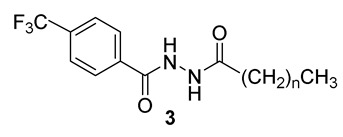

Based on the antimycobacterial activity of the derivative 2f, we decided to prepare several its analogues. First, we investigated the 1,2-diacylhydrazines 3 (Scheme 3), i.e., derivative with no secondary amine group. The N´-hexyl derivative 3a was prepared via direct acylation from the 1 and hexanoyl chloride in the presence of base (TEA; yield 79%). In order to investigate the length of the acyl chain, also N´-hexadecanoyl derivative 3b was synthesized using carbodiimide (EDAC)/1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt)-mediated coupling (97%).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 1,2-diacylhydrazines 3 (DCM: dichloromethane; HOBt: 1-hydroxybenzotriazole; EDAC: 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride).

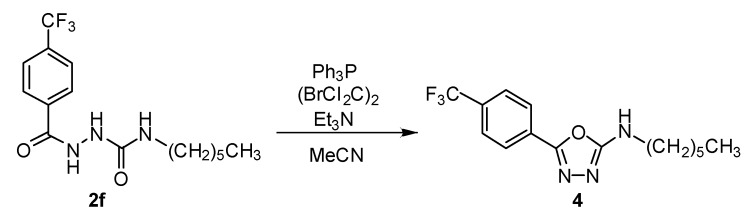

According to [11], the derivative 2f was cyclized to corresponding N-hexyl-5-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-amine (4) by treatment with triphenylphosphine, 1,2-dibromo-1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane and TEA in anhydrous acetonitrile (82%; Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of 1,3,4-oxadiazole-2-amine 4 (Ph3P: triphenylphosphine; (BrCl2C)2: 1,2-dibromo-1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane).

All the compounds 2–4 (Table 1) were characterized by their 1H- and 13C-NMR and infrared spectra and melting points. Additionally, the purity was checked by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and elemental analysis.

Table 1.

IC50 values for AChE and BuChE.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | n | IC50 AChE (µM) | IC50 BuChE (µM) | Selectivity BuChE/AChE |

| 2a | 0 | 31.23 ± 1.87 | 84.16 ± 2.10 | 2.7 |

| 2b | 1 | 56.32 ± 0.54 | 102.80 ± 2.75 | 1.8 |

| 2c | 2 | 82.27 ± 3.31 | 112.70 ± 0.98 | 1.4 |

| 2d | 3 | 38.60 ± 1.32 | 87.81 ± 7.96 | 2.3 |

| 2e | 4 | 43.59 ± 0.41 | 58.01 ± 0.78 | 1.3 |

| 2f | 5 | 49.16 ± 2.36 | 72.47 ± 1.51 | 1.5 |

| 2g | 6 | 59.16 ± 2.38 | 79.29 ± 1.53 | 1.3 |

| 2h | 7 | 76.97 ± 4.75 | 101.28 ± 0.99 | 1.3 |

| 2i | 8 | 106.75 ± 1.73 | 82.24 ± 3.42 | 0.8 |

| 2j | 9 | 49.47 ± 1.74 | 191.81 ± 6.83 | 3.9 |

| 2k | 10 | 40.71 ± 0.37 | 179.12 ± 2.96 | 4.4 |

| 2l | 11 | 45.25 ± 0.69 | 264.14 ± 0.22 | 5.8 |

| 2m | 12 | 28.90 ± 0.67 | 277.48 ± 10.27 | 9.6 |

| 2n | 13 | 38.74 ± 1.14 | 261.70 ± 17.20 | 6.8 |

| 2o | 14 | 27.04 ± 1.13 | 233.18 ± 15.69 | 8.6 |

| 2p | 15 | 68.63 ± 0.56 | 186.75 ± 13.24 | 2.7 |

| 2q | 17 | 72.31 ± 2.01 | 145.72 ± 2.60 | 2.0 |

| ||||

| 3a | 4 | 67.12 ± 3.05 | 109.98 ± 0.20 | 1.6 |

| 3b | 14 | 91.87 ± 6.79 | 148.60 ± 0.36 | 1.6 |

| ||||

| 4 | - | 71.32 ± 0.63 | 118.40 ± 1.46 | 1.7 |

| 1 | - | 69.37 ± 1.38 | 204.00 ± 2.69 | 2.9 |

| Rivastigmine | 56.10 ± 1.41 | 38.40 ± 1.97 | 0.7 | |

AChE and BuChE inhibition are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = three independent experiments). The three lowest IC50 values for each enzyme are given in bold.

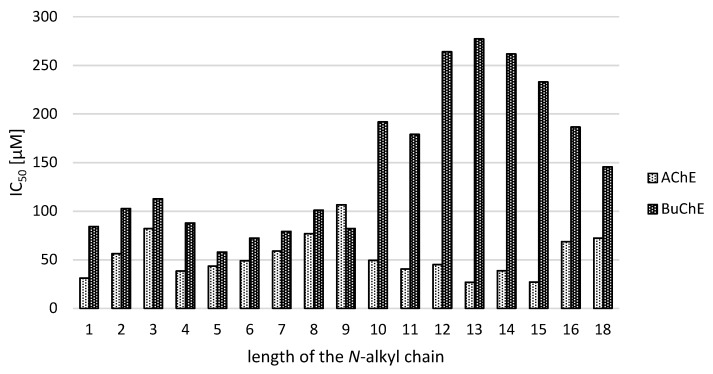

2.2. Inhibition of Acetyl- and Butyrylcholinesterase

Newly synthesized N-alkyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamides 2a–2q were evaluated for their in vitro potency to inhibit AChE from electric eel (EeAChE) and BuChE from equine serum (EqBuChE) using modified Ellman’s spectrophotometric method [16]. The results (Table 1 and Figure 1) were compared with those determined for rivastigmine, a clinically used drug for treatment of various dementia. From chemical point of view, it is an aromatic carbamate-based dual inhibitor of both cholinesterases. The efficacy of inhibitors is expressed as IC50, i.e., the concentration causing 50% inhibition of the enzyme activity. Based on IC50 values for both enzymes, selectivity indexes (SI) as the ratio of IC50 for BuChE/IC50 for AChE to quantify the preference for AChE were calculated (Table 1). The results were compared with those obtained for rivastigmine, an established carbamate used in the therapy of not only Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s dementias due to its cholinergic effect. From molecular pharmacology point of view, this drug belongs to dual acylating pseudo-irreversible inhibitors of both AChE and BuChE.

Figure 1.

The dependence of enzyme inhibition on alkyl chain length of N-substituted-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide scaffold 2.

Generally, with only one exception (the nonyl derivative 2i), the hydrazine-1-carboxamides 2 are stronger inhibitors of AChE. Focusing on this enzyme, IC50 values were found in a close range of 27.04 (2o)–106.75 (2i) µM. The values of ten compounds (2a, 2d–2f, 2j–2o) are superior to the IC50 for rivastigmine (56.10 µM), the other two (2b and 2g) produced comparable in vitro activity. By comparison with the parent hydrazide 1, the majority of its carboxamides (2a, 2b, 2d–2g, and 2j–2o) showed an improved inhibition of AChE; thus, this structural modification can be considered as successful increasing the activity by up to 2.6 times (1 vs. 2o and 2m).

Of course, in these analogues the length of N-alkyl chain is the only structural factor influencing the inhibitory properties. Interestingly, the elongation of the substituent decreases the activity (from C1 to C3, 31.2 and 82.3 µM, respectively). Then a drop of IC50 value was observed (IC50 of C4 = 38.6 µM) followed by analogous gradual reduction of the inhibitory properties up to the global minimum of 106.8 µM (2i). Next three compounds (decyl, undecyl and dodecyl 2j–2l) exhibited similar improved activity around 40–50 µM, followed by even more efficient tetradecyl (2n) and especially the best tridecyl 2m and pentadecyl 2o derivatives (IC50 28.9 and 27.0 µM, respectively). Then, IC50 values are increasing slowly again (up to C18 with 72.31 µM). Starting from C10 to C16, even-odd effect can be observed favoring odd alkyls. These structure-activity relationships and trends are depicted in Figure 1.

Analyzing results of BuChE inhibition, somewhat different results and structure-activity relationships were found. Overall, IC50 values for BuChE were higher and in a broader concentration range from 58.0 µM (N-pentyl molecule 2e) up to 277.5 µM (the most active AChE inhibitor 2m). None of the derivatives 2 exhibited more potent inhibition than rivastigmine (38.4 µM). Notably, twelve carboxamides showed an improved inhibition of the parent 4-CF3-benzohydrazide 1 (2a–2k, 2p, 2q), even up to 3.5 times (1 vs. 2e). Clearly, N-n-alkyl from butyl to nonyl (2d–2i) is essential for enhanced BuChE inhibition with an optimum of 5–7 carbons (Figure 1). The gradual diminishing of the enzyme inhibition potency was observed for these extending chain length: from C1 to C3, C5 → C8, C9 → C10, C11 → C13.

Analogous “oscillating” activity without one dominant trend depending on alkyl chain length has been described previously, e.g., by Imramovský et al. [17]. There are many factors influencing inhibition of AChE and BuChE, not solely the length of n-alkyl chain, e.g., such as lipophilicity, electronic and steric effects. Moreover, inhibitors of AChE can interact with more enzyme “subsites”, either with one or with more at once. They may interfere with peripheral anionic site, catalytic esteratic subsite (competitively, irreversibly or pseudo-irreversibly), anionic site in the active site, or they can bind into a narrow aromatic gorge, thus preventing access of the substrate to the catalytic triad [18]. Based on the alkyl length, a change of fitting into enzyme can occur. The alkyls that are flexible may also adopt a conformation that allows a better interaction with the enzyme.

All the derivatives 2 act as dual inhibitors of both cholinesterase enzymes. With an exception of N-nonyl carboxamide 2i, the derivatives produced more intense inhibition of AChE. We used selectivity index for its quantification. Some of short and intermediate alkyls led to a comparatively balanced inhibition of both cholinesterases (SI ≤ 1.5; propyl 2c, from pentyl 2e to octyl 2h). Contrarily, four derivatives led to a significantly preferential inhibition of AChE (SI > 5; 2l–2o). Notably, an escalated AChE selectivity is related to longer alkyls (from C10 to C15).

Then, we screened an inhibition of cholinesterases caused by three analogues synthesized for their potential antimycobacterial activity primarily (3a, 3b and 4). These derivatives produced identical or decreased inhibition of AChE when compared to the parent hydrazide 1 (67.1–91.9 µM vs. 69.4 µM). On the other hand, all of them are more potent inhibitors of BuChE (IC50 values from 110 to 148.6 µM) with similar selectivity indexes. The shorter carbon chain (C6) is preferred over long one (C16). In general, the amides 3 and the oxadiazole 4 do not overcome the in vitro effect of the hydrazinecarboxamides 2.

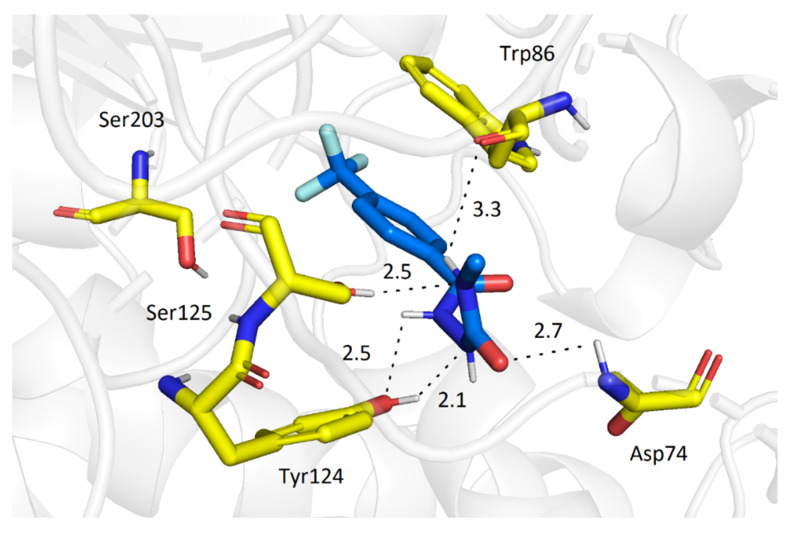

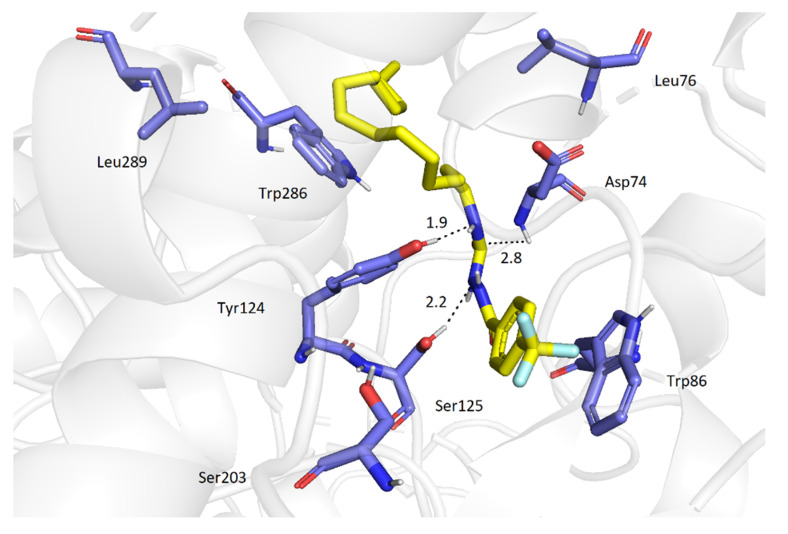

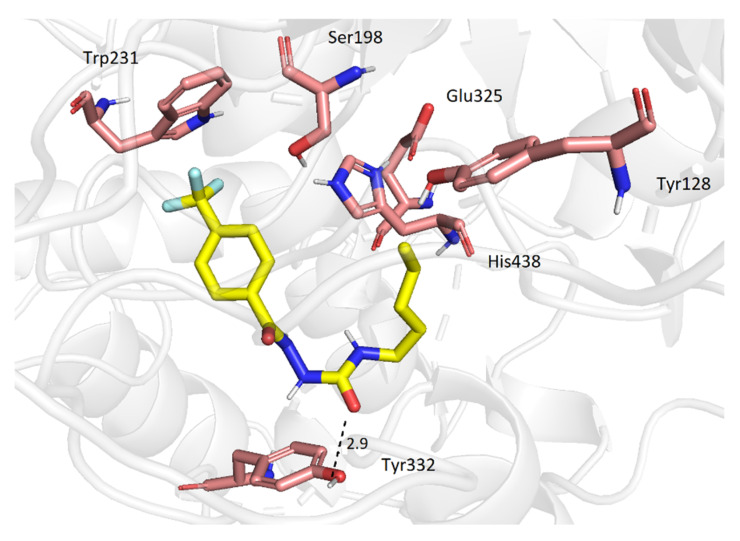

Molecular Docking Study

In order to presume possible binding mode of the prepared molecules with human AChE (pdb code 4PQE) and BChE (pdb code 1POI), molecular modelling study was performed. The most potent compound 2o and the third most active derivative 2a against AChE, were chosen as representatives for thorough investigation of ligand-enzyme interactions in the active site of AChE. Similarly, the carboxamide 2e, being the most potent molecule against BuChE, was used for the determination of the binding mode in BuChE.

The best docking pose of 2a in AChE showed the molecule of the ligand placed deep within the cavity, in a close proximity to the active site triad (Figure 2). A significant amount of H-bonds (with Ser125, Tyr124, Trp86 and Asp74) indicates highly favorable orientation of 2a. Additionally, π-π stacking with Trp86 further stabilizes the ligand-enzyme non-covalent complex. Also, the carboxamide 2o binds closely to the catalytic triad at the bottom of the cavity (Figure 3) in a similar manner. There are three hydrogen bonds (with Ser125, Tyr124 and Asp74) and, in addition, this binding mode is stabilized by π-π stacking interaction with Trp86. The long tridecyl chain is heading out of the gorge (forming hydrophobic interactions with Leu76, Leu289 and Trp286), thereby hindering access of AChE to the active site.

Figure 2.

Molecular interactions of 2a (blue) and AChE.

Figure 3.

Molecular interactions of 2o (yellow) and AChE.

Concerning BuChE, all the presented compounds displayed a similar orientation in the active site of BuChE, regardless of the growing size of their molecules. This may be due to a relatively spacious cavity of BuChE compared to the one in AChE. However, the derivative 2e displayed only a few detectable interactions, namely H-bond with Tyr332 and CF-π with Trp231 (Figure 4). Nevertheless, the ligand possesses the ability to block the catalytic triad completely.

Figure 4.

Molecular interactions of 2e (yellow) and BuChE.

2.3. Antimycobacterial Activity

Since the hydrazine-1-carboxamides 2 are isosteres of previously reported antimycobacterial 2-isonicotinoylhydrazine-1-carboxamides [11], initially we screened in vitro antimycobacterial activity of the derivatives 2. The panel of mycobacteria covers drug-susceptible strain Mycobacterium tuberculosis 331/88 (i.e., H37Rv) and three atypical mycobacterial strains, namely Mycobacterium avium 330/88 (polydrug-resistant) and one collection strains of Mycobacterium kansasii (235/80) and a clinical isolate (M. kansasii 6509/96).

For most compounds, the exact determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) was not feasible due to their limited solubility in the testing medium (evidenced by precipitation and/or turbidity); their MIC exceeded 250 µM. None of the derivatives 1–4 was capable of M. avium inhibition. M. tuberculosis and both strains of M. kansasii were inhibited by six compounds. Among primarily designed derivatives 2, the derivatives with the shortest alkyl chains (2a and 2b) were negligibly active (MIC of 1000 µM). On the other hand, N-hexyl derivative 2f exhibited a uniform MIC of 250 µM. Thus, we synthesized and evaluated its analogues 3 and 4. The cyclization of the carboxamide 2f to 1,3,4-oxadiazole 4 retained potency for M. tuberculosis (MIC of 125–250 µM) and improved activity against M. kansasii mildly (62.5–250 µM). N´-hexanoylhydrazide 3a exhibited lower MIC for M. tuberculosis (125 µM), but this modification hampered efficacy against M. kansasii (>250 µM).

Drawing a comparison between the parent hydrazide 1 [4] and its analogues, two derivatives were superior (3a, 4) and the activity of 2f was identical. All of these compounds produced lower MIC against M. kansasii. The first-line antituberculotic hydrazide drug isoniazid (INH), involved for comparison, exhibited significantly higher growth inhibition of M. tuberculosis (1 µM) and the isolate of M. kansasii from a patient. On the other hand, the hydrazide 2f and the oxadiazole 4 were superior against M. kansasii 235/80.

Despite these structure-activity relationships described, the activity against both tuberculous and nontuberculous mycobacteria is significantly lower than in the case of original N-alkyl-2-isonicotinoylhydrazine-1-carboxamides, i.e., derivatives of INH. That is why no MIC for multidrug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains were determined.

2.4. Cytostatic Properties

Since compounds containing trifluoromethyl group has been known for their toxic action on eukaryotic cells and approved as anticancer drugs [19], we investigated cytostatic properties of the derivatives 2–4 using human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) and monocyte (MonoMac6) cell lines. The compounds with shorter alkyls (2a–2d) and parent 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide (1) as well avoided any cytostatic action for both cell lines at a concentration of 100 µM. The remaining compounds have no cytostatic effect up to 50 µM. Higher concentrations were not investigated due to solubility problems, i.e., precipitation of crystals. In sum, none of the compounds showed any cytostatic properties against these eukaryotic cells.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General

All the reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany) or Penta Chemicals (Prague, Czech Republic) and they were used as received. The purity of the compounds was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). TLC plates were coated with 0.2 mm Merck 60 F254 silica gel (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) with UV detection (254 nm). The melting points were determined on a B-540 Melting Point apparatus (Büchi, Flawil, Switzerland) using open capillaries and they are uncorrected. Infrared spectra were recorded on a FT-IR spectrometer using the ATR-Ge method (Nicolet 6700 FT-IR, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in the range of 650–4000 cm−1. The NMR spectra were measured in DMSO-d6 or N,N-dimethylformamide-d7 (DMF-d7) at ambient and higher (80 °C) temperature using a Varian V NMR S500 instrument (500 MHz for 1H and 126 MHz for 13C; Varian Corp., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The chemical shifts δ are given in ppm and were referred indirectly to tetramethylsilane via signals of DMSO-d6 (2.50 for 1H and 39.51 for 13C spectra) or DMF-d7 (2.75, 2.92 and 8.03 for 1H, 29.76, 34.89 and 163.15 for 13C spectra). The coupling constants (J) are reported in Hz. Elemental analysis was performed on a Vario MICRO Cube Element Analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme, Hanau, Germany). Both calculated and found values are given as percentages.

The calculated logP values (ClogP) that are the logarithms of the partition coefficients for octan-1-ol/water, were determined using the program CS ChemOffice Ultra version 18.0 (CambridgeSoft, Cambridge, MA, USA).

The identity of the known compounds was established using NMR and IR spectroscopy. Additionally, their purity was checked by melting points measurement and elemental analysis. The compounds were considered pure if they agree within ±0.4% with theoretical values.

3.1.2. Synthesis of N-alkyl Hydrazine-1-carboxamides 2

Method A

4-(Trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide (1, 204.2 mg, 1.0 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous acetonitrile (MeCN, 8 mL) and then the appropriate isocyanate (1.05 mmol) was added in one portion. The reaction mixture was stirred at the room temperature for 8 h, then stored for 2 h at −20 °C. Resulting precipitate was filtered off, washed with a small volume of MeCN and dried. The products were recrystallised from ethyl acetate if necessary.

Method B

Method B is based on generation of an appropriate isocyanate in situ. Triphosgene (bis(trichloromethyl)carbonate; 118.7 mg, 0.4 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM; 5 mL) under nitrogen atmosphere and the appropriate amine (1.01 mmol) dissolved in anhydrous DCM (5 mL) was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature, then treated with triethylamine (TEA; 293 µL, 2.1 mmol). After 30 min, 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide (1, 204.2 mg, 1.0 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 10 h at room temperature, then evaporated to dryness, treated with water (10 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate, filtered off and evaporated to dryness to give the final product, which was crystallised from ethyl acetate.

Method C

4-(Trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide (1, 204.2 mg, 1.0 mmol) was dissolved in acetonitrile (5 mL) and mixed with N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA; 2.0 mmol, 348 µL) and N-succinimidyl N-methylcarbamate (258.2 mg, 1.5 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at the room temperature for 24 h, formed precipitate was filtered off and crystallised from ethyl acetate.

3.1.3. Synthesis of 1,2-diacylhydrazines 3

Method A

4-(Trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide (1, 204.2 mg, 1.0 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (8 mL) together with triethylamine (1.5 mmol, 209 µL). Then, an acyl chloride (1.1 mmol) was added in one portion. The reaction mixture was stirred at the room temperature for 1 h. Then, resulted precipitate was filtered off, washed with a small volume of DCM and crystallised from ethyl acetate.

Method B

4-(Trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide (1, 204.2 mg, 1.0 mmol) was mixed with triethylamine (1.5 mmol, 209 µL), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (HOBt; 1 mmol, 153.1 mg) and appropriate acid (1 mmol) in DCM (8 mL). The mixture was cooled down to 0 °C. Then, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDAC; 1.5 mmol, 287.6 mg) was added in one portion and the reaction mixture was let stir at the room temperature. After 48 h, resulted precipitate was filtered off, washed with a small volume of DCM and crystallised from ethyl acetate.

3.1.4. Synthesis of 1,3,4-oxadiazole 4

Triphenylphosphine (1.5 mmol, 393.4 mg) was added to the stirred suspension of 1,2-dibromo-1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane (0.83 mmol, 271.1 mg) and N-hexyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]-hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2f, 0.75 mmol, 248.5 mg) in anhydrous MeCN (4 mL) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min and then cooled to 0 °C. Triethylamine (3.3 mmol, 459 µL) was added dropwise, and the stirring continued for an additional 10 h. Resulting crystals were filtered off, washed with a small volume of water followed by MeCN and dried to provide pure 4.

3.2. Product Characterization

N-Methyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2a). White solid; yield 77% (method C); mp 237–238.5 °C. IR (ATR): 3310, 3269, 3074, 1656, 1643, 1583, 1546, 1509, 1425, 1411, 1326, 1315, 1260, 1165, 1116, 1071, 1016, 914, 858, 766, 694, 643, 629 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.30 (1H, s, NH), 8.05 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.93 (1H, s, NH), 7.83 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H3, H5), 6.44 (1H, q, J = 6.1 Hz, NH-alkyl), 2.54 (3H, d, J = 6.1 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.49, 158.93, 136.83, 132.00 (q, J = 31.9 Hz), 128.71, 125.61 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 124.41 (q, J = 272.5 Hz), 26.76. Anal. Calcd for C10H10F3N3O2 (261.20): C, 45.98; H, 3.86; N, 16.09. Found: C, 45.79; H, 4.01; N, 15.93.

N-Ethyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2b). White solid; yield 89% (method A); mp 231.5–232.5 °C. IR (ATR): 3309, 3071, 2984, 1666, 1640, 1576, 1545, 1508, 1461, 1379, 1325, 1313, 1255, 1173, 1120, 1085, 1069, 1015, 858, 694, 625 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.32 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H2, H6), 7.90 (1H, s, NH), 7.86 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H3, H5), 6.53 (1H, t, J = 5.7 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.09–3.02 (2H, m, CH2), 1.01 (3H, t, J = 7.1 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.40, 158.21, 136.81, 131.65 (q, J = 31.9 Hz), 128.66, 125.47 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 124.08 (q, J = 272.7 Hz), 34.24, 15.70. Anal. Calcd for C11H12F3N3O2 (275.23): C, 48.00; H, 4.39; N, 15.27. Found: C, 48.15; H, 4.44; N, 14.98.

N-Propyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2c). White solid; yield 97% (method A); mp 227.5–228.5 °C. IR (ATR): 3273, 2967, 2878, 1688, 1657, 1647, 1558, 1543, 1489, 1328, 1262, 1170, 1128, 1071, 1017, 901, 859, 776, 631 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.32 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.89–7.84 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.53 (1H, t, J = 6.0 Hz, NH-alkyl), 2.98 (2H, dt, J = 7.4, 6.1 Hz, N-CH2), 1.40 (2H, sext, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2), 0.82 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.38, 158.34, 136.81, 131.63 (q, J = 31.9 Hz), 128.65, 125.48 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 124.08 (q, J = 272.4 Hz), 41.18, 23.21, 11.41. Anal. Calcd for C12H14F3N3O2 (289.25): C, 49.83; H, 4.88; N, 14.53. Found: C, 50.05; H, 4.64; N, 14.80.

N-Butyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2d). White solid; yield 96 % (method A); mp 224.5–225.5 °C. IR (ATR): 3295, 2967, 2938, 2879, 1662, 1642, 1581, 1543, 1508, 1489, 1340, 1326, 1315, 1245, 1170, 1121, 1072, 1015, 857, 694, 636 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.32 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.89–7.84 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.51 (1H, t, J = 5.8 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.02 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.37 (2H, p, J = 7.3 Hz, C2H2), 1.26 (2H, sext, J = 7.3 Hz, C3H2), 0.86 (3H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.38, 158.32, 136.81, 131.64 (q, J = 31.9 Hz), 128.65, 125.47 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 124.07 (q, J = 272.4 Hz), 39.05, 32.15, 19.59, 13.87. Anal. Calcd for C13H16F3N3O2 (303.28): C, 51.48; H, 5.32; N, 13.86. Found: C, 51.33; H, 5.60; N, 13.78.

N-Pentyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2e). White solid; yield 98 % (method A); mp 227–228 °C. IR (ATR): 3297, 3074, 2936, 2877, 1655, 1639, 1582, 1547, 1510, 1481, 1333, 1326, 1315, 1258, 1238, 1171, 1122, 1071, 1015, 858, 694, 642, 629 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.31 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.2 Hz, H2, H6), 7.88–7.84 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.51 (1H, t, J = 5.8 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.01 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.39 (2H, p, J = 7.2 Hz, C2H2), 1.31–1.18 (4H, m, C3H2, C4H2), 0.85 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.37, 158.30, 136.80, 131.63 (q, J = 31.9 Hz), 128.64, 125.46 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 124.07 (q, J = 272.5 Hz), 39.36, 29.68, 28.67, 22.05, 14.09. Anal. Calcd for C14H18F3N3O2 (317.31): C, 52.99; H, 5.72; N, 13.24. Found: C, 52.78; H, 5.68; N, 13.36.

N-Hexyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2f). White solid; yield 99 % (method A); mp 209.5–210 °C. IR (ATR): 3296, 2930, 2862, 1668, 1640, 1580, 1543, 1508, 1471, 1343, 1326, 1314, 1268, 1254, 1171, 1120, 1072, 1015, 857, 719, 696, 627 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.28 (1H, s, NH), 8.04 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.85–7.82 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.48 (1H, t, J = 5.8 Hz, NH-alkyl), 2.97 (2H, q, J = 6.5 Hz, N-CH2), 1.35 (2H, p, J = 7.3 Hz, C2H2), 1.26–1.18 (6H, m, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2), 0.82 (3H, t, J = 7.0 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.74, 158.67, 137.18, 131.99 (q, J = 31.9 Hz), 129.01, 125.85 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 124.44 (q, J = 272.6 Hz), 39.78, 31.58, 30.34, 26.50, 22.62, 14.44. Anal. Calcd for C15H20F3N3O2 (331.33): C, 54.37; H, 6.08; N, 12.68. Found: C, 54.55; H, 6.00; N, 12.49.

N-Heptyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2g). White solid; yield 95 % (method A); mp 210.5–212.5 °C. IR (ATR): 3303, 3072, 2955, 2927, 2857, 1668, 1638, 1582, 1548, 1471, 1379, 1327, 1311, 1258, 1171, 1120, 1072, 1015, 856, 696, 629 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.31 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.88–7.84 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.51 (1H, t, J = 5.8 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.00 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.38 (2H, p, J = 7.0 Hz, C2H2), 1.29–1.18 (8H, m, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2), 0.84 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.36, 158.31, 136.80, 131.63 (q, J = 31.9 Hz), 128.64, 125.45 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 124.06 (q, J = 272.4 Hz), 39.38, 31.45, 30.01, 28.64, 26.42, 22.21, 14.09. Anal. Calcd for C16H22F3N3O2 (345.36): C, 55.64; H, 6.42; N, 12.17. Found: C, 55.59; H, 6.62; N, 12.32.

N-Octyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2h). White solid; yield 98 % (method A); mp 217–218 °C. IR (ATR): 3295, 2926, 2856, 1654, 1639, 1581, 1546, 1481, 1327, 1315, 1249, 1171, 1121, 1073, 1015, 858, 694, 632 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.32 (1H, s, NH), 8.08 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.89–7.84 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.51 (1H, t, J = 5.9 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.01 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.38 (2H, p, J = 6.7 Hz, C2H2), 1.29–1.18 (10H, m, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2), 0.84 (3H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.37, 158.32, 136.81, 131.64 (q, J = 32.0 Hz), 128.64, 125.45 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 124.07 (q, J = 272.5 Hz), 39.40, 31.42, 30.02, 28.96, 28.88, 26.48, 22.26, 14.09. Anal. Calcd for C17H24F3N3O2 (359.39): C, 56.81; H, 6.73; N, 11.69. Found: C, 56.68; H, 6.69; N, 11.53.

N-Nonyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2i). White solid; yield 99 % (method A); mp 204–206 °C. IR (ATR): 3297, 3071, 2925, 2854, 1666, 1638, 1582, 1546, 1471, 1343, 1327, 1315, 1257, 1170, 1121, 1072, 1015, 857, 695, 628 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.32 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.88–7.83 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.51 (1H, t, J = 5.7 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.00 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.37 (2H, p, J = 6.9 Hz, C2H2), 1.28–1.18 (12H, m, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2, C8H2), 0.84 (3H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.39, 158.34, 136.81, 131.65 (q, J = 31.8 Hz), 128.66, 125.47 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 124.08 (q, J = 272.5 Hz), 39.40, 31.48, 30.03, 29.20, 29.02, 28.86, 26.49, 22.28, 14.12. Anal. Calcd for C18H26F3N3O2 (373.41): C, 57.90; H, 7.02; N, 11.25. Found: C, 58.07; H, 6.95; N, 11.31.

N-Decyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2j). White solid; yield 90 % (method B); mp 204–205 °C. IR (ATR): 3301, 2921, 2854, 1667, 1638, 1584, 1548, 1471, 1327, 1314, 1529, 1172, 1122, 1073, 1015, 857, 719, 695, 645, 630 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.31 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.88–7.83 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.50 (1H, t, J = 5.8 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.00 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.37 (2H, p, J = 6.8 Hz, C2H2), 1.29–1.18 (14H, m, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2, C8H2, C9H2), 0.84 (3H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.34, 158.29, 136.79, 131.62 (q, J = 32.1 Hz), 128.62, 125.43 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 124.05 (q, J = 272.5 Hz), 39.37, 31.45, 30.00, 29.21, 29.13, 28.98, 28.87, 26.46, 22.24, 14.07. Anal. Calcd for C19H28F3N3O2 (387.44): C, 58.90; H, 7.28; N, 10.85. Found: C, 58.82; H, 6.99; N, 11.00.

2-[4-(Trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]-N-undecylhydrazine-1-carboxamide (2k). White solid; yield 98 % (method A); mp 201.5–203 °C. IR (ATR): 3304, 3070, 2955, 2920, 2853, 1667, 1638, 1583, 1545, 1471, 1377, 1343, 1328, 1315, 1259, 1170, 1122, 1073, 1015, 857, 718, 696, 629 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.30 (1H, s, NH), 8.06 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H2, H6), 7.88–7.83 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.51 (1H, t, J = 5.9 Hz, NH-alkyl), 2.99 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.38 (2H, p, J = 6.8 Hz, C2H2), 1.29–1.18 (16H, m, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2, C8H2, C9H2, C10H2), 0.83 (3H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.50, 158.41, 136.87, 131.69 (q, J = 32.1 Hz), 128.72, 125.56 (q, J = 3.9 Hz), 124.04 (q, J = 272.5 Hz), 39.39, 31.53, 30.07, 29.29, 29.27, 29.25, 29.06, 28.95, 26.53, 22.33, 14.19. Anal. Calcd for C20H30F3N3O2 (401.47): C, 59.83; H, 7.53; N, 10.47. Found: C, 59.94; H, 7.74; N, 10.65.

N-Dodecyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2l). White solid; yield 99 % (method A); mp 197.5–200 °C. IR (ATR): 3306, 3071, 2956, 2917, 2851, 1667, 1640, 1584, 1545, 1471, 1441, 1327, 1315, 1254, 1172, 1122, 1073, 1015, 857, 718, 696, 628 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.31 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H2, H6), 7.88–7.84 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.50 (1H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.00 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.37 (2H, p, J = 6.8 Hz, C2H2), 1.30–1.17 (18H, m, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2, C8H2, C9H2, C10H2, C11H2), 0.84 (3H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.38, 158.32, 136.82, 131.64 (q, J = 32.0 Hz), 128.65, 125.47 (q, J = 3.9 Hz), 124.08 (q, J = 272.6 Hz), 39.34, 31.47, 30.00, 29.25, 29.24, 29.20, 29.13, 29.01, 28.89, 26.48, 22.27, 14.12. Anal. Calcd for C21H32F3N3O2 (415.49): C, 60.70; H, 7.76; N, 10.11. Found: C, 60.69; H, 7.74; N, 10.27.

N-Tridecyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2m). White solid; yield 91 % (method B); mp 199–200 °C. IR (ATR): 3302, 2918, 2851, 1667, 1639, 1583, 1546, 1471, 1328, 1315, 1263, 1171, 1122, 1073, 1015, 857, 718, 696, 640, 622 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.30 (1H, s, NH), 8.06 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.89–7.84 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.50 (1H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.00 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.42–1.15 (22H, m, C2H2, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2, C8H2, C9H2, C10H2, C11H2, C12H2), 0.84 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.35, 158.29, 136.80, 131.61 (q, J = 32.0 Hz), 128.63, 125.46 (q, J = 3.9 Hz), 124.05 (q, J = 272.6 Hz), 39.37, 31.45, 30.00, 29.28–29.11 (5C, overlapping), 28.98, 28.86, 26.45, 22.25, 14.10. Anal. Calcd for C22H34F3N3O2 (429.52): C, 61.52; H, 7.98; N, 9.78. Found: C, 61.44; H, 7.86; N, 10.01.

N-Tetradecyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2n). White solid; yield 97 % (method A); mp 193.5–195.5 °C. IR (ATR): 3302, 3918, 2851, 1667, 1639, 1584, 1546, 1471, 1379, 1328, 1314, 1258, 1172, 1122, 1073, 1015, 857, 719, 695, 637, 628 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.31 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.88–7.83 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.50 (1H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.00 (2H, q, J = 6.7 Hz, N-CH2), 1.42–1.13 (24H, m, C2H2, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2, C8H2, C9H2, C10H2, C11H2, C12H2, C13H2), 0.84 (3H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.35, 158.29, 136.80, 131.62 (q, J = 32.0 Hz), 128.63, 125.48 (q, J = 3.9 Hz), 124.06 (q, J = 272.6 Hz), 39.37, 31.45, 30.01, 29.29-29.12 (6C, overlapping), 28.98, 28.86, 26.46, 22.25, 14.11. Anal. Calcd for C23H36F3N3O2 (443.55): C, 62.28; H, 8.18; N, 9.47. Found: C, 62.39; H, 8.30; N, 9.54.

N-Pentadecyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2o). White solid; yield 78 % (method B); mp 178.5–180.5 °C. IR (ATR): 3308, 2954, 2919, 2850, 1667, 1638, 1582, 1554, 1471, 1329, 1315, 1259, 1170, 1122, 1073, 1015, 857, 719, 696, 644, 622 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.30 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H2, H6), 7.88–7.84 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.51 (1H, t, J = 5.7 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.01 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.42–1.13 (26H, m, C2H2, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2, C8H2, C9H2, C10H2, C11H2, C12H2, C13H2, C14H2), 0.84 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.37, 158.30, 136.79, 131.64 (q, J = 32.0 Hz), 128.63, 125.46 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 124.07 (q, J = 272.6 Hz), 39.37, 31.44, 30.00, 29.29-29.11 (7C, overlapping), 28.98, 28.86, 26.44, 22.24, 14.09. Anal. Calcd for C24H38F3N3O2 (457.57): C, 63.00; H, 8.37; N, 9.18. Found: C, 62.78; H, 8.44; N, 9.09.

N-Hexadecyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2p). White solid; yield 99 % (method A); mp 191.5–193.5 °C. IR (ATR): 33308, 2955, 2916, 2850, 1667, 1639, 1585, 1544, 1471, 1379, 1328, 1315, 1263, 1172, 1122, 1073, 1015, 857, 718, 696, 647, 638, 627 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.31 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, H2, H6), 7.89–7.85 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.50 (1H, t, J = 5.7 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.00 (2H, q, J = 6.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.41–1.16 (28H, m, C2H2, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2, C8H2, C9H2, C10H2, C11H2, C12H2, C13H2, C14H2, C15H2), 0.85 (3H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 165.35, 158.31, 136.78, 131.65 (q, J = 32.0 Hz), 128.64, 125.46 (q, J = 3.9 Hz), 124.08 (q, J = 272.6 Hz), 39.37, 31.44, 30.00, 29.29–29.10 (8C, overlapping), 28.97, 28.86, 26.44, 22.23, 14.10. Anal. Calcd for C25H40F3N3O2 (471.60): C, 63.67; H, 8.55; N, 8.91. Found: C, 63.73; H, 8.69; N, 8.77.

N-Octadecyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide (2q). White solid; yield 98 % (method A); mp 193.5–196 °C. IR (ATR): 3303, 2191, 2850, 1666, 1639, 1586, 1548, 1470, 1329, 1315, 1256, 1172, 1122, 1074, 1015, 857, 719, 695, 648, 640, 630 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.30 (1H, s, NH), 8.07 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H2, H6), 7.88–7.84 (3H, m, NH, H3, H5), 6.49 (1H, t, J = 5.9 Hz, NH-alkyl), 3.00 (2H, q, J = 7.0 Hz, N-CH2), 1.41–1.12 (32H, m, C2H2, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2, C8H2, C9H2, C10H2, C11H2, C12H2, C13H2, C14H2, C15H2, C16H2, C17H2), 0.85 (3H, t, J = 6.9 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMF, 80 °C): δ 165.95, 158.48, 137.48, 132.13 (q, J = 33.9 Hz), 128.44, 125.29 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 124.10 (q, J = 272.5 Hz), 39.91, 31.63, 30.14, 29.38, 29.31, 29.14, 28.99, 28.90 (overlapping signals, partly overlapping with solvent signals), 26.71, 22.29, 13.38. Anal. Calcd for C27H44F3N3O2 (499.65): C, 64.90; H, 8.88; N, 8.41. Found: C, 65.04; H, 8.99; N, 8.30.

N′-Hexanoyl-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide (3a). White solid; yield 79 % (method A); mp 188–190 °C. IR (ATR): 3203, 2953, 2874, 1600, 1572, 1516, 1475, 1423, 1406, 1324, 1223, 1165, 1126, 1109, 1067, 1016, 860, 726, 690, 648, 628 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.52 (1H, s, NH), 9.91 (1H, s, NH), 8.05 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.87 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H3, H5), 2.18 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CO-CH2), 1.55 (2H, p, J = 7.3 Hz, C3H2), 1.33–1.25 (4H, m, C4H2, C5H2), 0.87 (3H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 171.71, 164.53, 136.53, 131.76 (q, J = 31.8 Hz), 128.52, 125.64 (q, J = 3.9 Hz), 124.04 (q, J = 272.3 Hz), 33.39, 30.93, 24.91, 22.03, 14.02. Anal. Calcd for C14H17F3N2O2 (302.29): C, 55.62; H, 5.67; N, 9.27. Found: C, 55.73; H, 5.88; N, 9.34.

N′-Palmitoyl-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide (3b). White solid; yield 97 % (method B); mp 152–153.5 °C. IR (ATR): 3195, 2952, 2916, 2848, 1672, 1603, 1571, 1516, 1480, 1465, 1413, 1329, 1226, 1211, 1165, 1125, 1108, 1069, 1016, 873, 859, 767, 723, 693, 651, 627 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 10.50 (1H, s, NH), 9.89 (1H, s, NH), 8.05 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H2, H6), 7.88 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz, H3, H5), 2.17 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CO-CH2), 1.54 (2H, p, J = 7.3 Hz, C3H2), 1.33–1.14 (24H, m, C4H2, C5H2, C6H2, C7H2, C8H2, C9H2, C10H2, C11H2, C12H2, C13H2, C14H2, C15H2), 0.84 (3H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMF): δ 171.73, 164.65, 136.93, 132.09 (q, J = 32.2 Hz), 128.43, 125.50 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 124.18 (q, J = 272.3 Hz), 33.54, 31.68, 29.48, 29.47, 26.45, 29.38, 29.22, 29.14, 29.00, 28.96 (overlapping signals, partly overlapping with solvent signals), 25.41, 22.39, 13.56. Anal. Calcd for C24H37F3N2O2 (442.56): C, 65.13; H, 8.43; N, 6.33. Found: C, 65.31; H, 8.25; N, 6.39.

N-Hexyl-5-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-amine (4). White solid; yield 82%; mp 91–92.5 °C. IR (ATR): 3202, 2954, 2874, 1599, 1572, 1517, 1475, 1323, 1223, 1170, 1125, 1109, 1066, 1015, 860, 726, 690, 649, 627 cm−1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.98 (2H, d, J = 8.2 Hz, H2, H6), 7.92 (1H, t, J = 5.7 Hz, NH), 7.87 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz, H3, H5), 3.24 (2H, td, J = 7.1, 5.6 Hz, N-CH2), 1.56 (2H, p, J = 7.1 Hz, C2H2), 1.36–1.23 (6H, m, C3H2, C4H2, C5H2), 0.85 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH3). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 164.14, 156.54, 130.15 (q, J = 32.0 Hz), 128.91, 126.35 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 125.82, 124.03 (q, J = 272.2 Hz), 42.73, 31.04, 28.85, 26.00, 22.16, 13.99. Anal. Calcd for C15H18F3N3O (313.32): C, 57.50; H, 5.79; N, 13.41. Found: C, 57.59; H, 5.97; N, 13.59.

3.3. Determination of AChE and BuChE Inhibition

IC50 values were determined using the spectrophotometric Ellman’s method modified according to Zdražilová et al. [16], which is a simple, rapid and direct method to determine the SH and -S-S- group content. This method is widely used for the screening of the efficiency of cholinesterases inhibitors. The enzymatic activity is measured indirectly by quantifying the concentration of the 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoic acid ion formed in the reaction between the thiol reagent 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) and thiocholine, a product of acetylthiocholine substrate hydrolysis by cholinesterases [20].

The enzyme activity in final reaction mixture (2000 µL) was 0.2 U/mL, concentration of acetylthiocholine (or butyrylthiocholine) 40 µM and concentration of 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) 0.1 mM for all reactions. The tested compounds were dissolved in DMSO and then diluted in demineralized water to the concentration of 1 mM. For all the tested compounds and a standard carbamate rivastigmine five different concentrations of inhibitor in final reaction mixture were used. All measurements were carried in triplicates and the average values of reaction rate (v0-uninhibited reaction, vi-inhibited reaction) were used for construction of the dependence v0/vi vs. concentration of inhibitor. From obtained equation of regression curve, IC50 values were calculated.

Acetylcholinesterase used was obtained from electric eel (Electrophorus electricus L.; EeAChE) and butyrylcholinesterase from equine serum (EqBuChE). Rivastigmine was used as a reference cholinesterase inhibitor. All the enzymes, substrates and rivastigmine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Prague, Czech Republic).

3.4. Molecular Docking

Crystallographic structures of human AChE and human BChE were obtained from Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org; pdb codes 4PQE and 1POI, respectively). The 3D structures of ligands were prepared in Chem3D Pro 19.1 (ChemBioOffice 2019 Package, CambridgeSoft, Cambridge, MA, USA). In the preparation process, all water molecules were removed from the enzymes and structures of enzymes and ligands were optimized using UCSF Chimera software package (Amber force field) [21]. Docking was performed using Autodock Vina [22] and Autodock 4.2 [23] (a Lamarckian genetic algorithm was used). The 3D affinity grid box was designed to include the full active and peripheral site of AChE and BChE. The number of grid points in the x-, y- and z-axes was 20, 20 and 20 with grid points separated by 1 Å (Autodock Vina) and 40, 40 and 40 with grid points separated by 0.4 Å (Autodock 4). The graphic visualisations of the ligand-enzyme interactions were prepared in PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5 Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, USA).

3.5. Antimycobacterial Activity

Derivatives of 1 were screened in vitro for their potential antimycobacterial activity against M. tuberculosis 331/88 (H37Rv; dilution of this strain was 10−3), Mycobacterium avium 330/88 (resistant to isoniazid, rifampicin, ofloxacin and ethambutol; dilution 10−5) and two strains of M. kansasii: 235/80 (dilution 10−4) and the clinically isolated M. kansasii strain 6509/96 (dilution 10−4) according to ref. [24]. The collection strains were obtained from Czech National Collection of Type Cultures (Prague, Czech Republic). The following concentrations were used: 1000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, and 1 μM. MIC (reported in μM) was the lowest concentration at which the complete inhibition of mycobacterial growth occurred. Isoniazid (INH) as a first-line oral antimycobacterial drug and the synthetic precursor 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide (1) were used as reference compounds.

3.6. Cytostatic Activity Evaluation

HepG2, human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (ATCC-HB8065) and MonoMac-6 cells (CC124; Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen and Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% foetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 160 µg/mL gentamycin at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in water-saturated atmosphere and grown to confluence and were plated into 96-well plate with initial cell number of 5.0–10.0 × 103 per well. After 24 h incubation at 37 °C, cells were treated with the compounds in 200 μL final volume containing 1.0% (v/v) DMSO. Cells were incubated with the compounds at 0.0128–100 µM concentration range for overnight. Control cells were treated with serum free medium (RPMI-1640) only or with DMSO (c = 1.0% v/v) at 37 °C for overnight. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with serum free medium (RPMI-1640). Cells were cultured for a further 72 h in serum containing medium.

The cell viability was determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The solution of MTT (45 μL, 2 mg/mL) was added to each well, which was reduced to insoluble violet formazan dye crystals within the living cells. After 3.5 h of incubation at 37 °C the cells were centrifuged for 5 min (2000 rpm) and supernatant was removed. The obtained formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 μL of DMSO and the optical density (OD) of the samples was measured at λ = 540 and 620 nm, respectively, employing an ELISA reader (iEMS Reader, Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). OD620 values were subtracted from OD540 values and the percent of cytostasis was calculated using the following equation:

| Cytostatic effect (%) = [1 − (ODtreated/ODcontrol)] × 100 |

where ODtreated and ODcontrol correspond to the optical densities of the treated and the control cells, respectively). For each compound, at least two independent experiments were carried out with four parallel measurements.

The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were determined from the dose-response curves. The curves were defined using MicrocalTM Origin1 version 7.6 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). Cytostasis (%) was plotted as a function of concentration, fitted to a sigmoidal curve and, based on this curve, the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value was determined representing the concentration of a compound required for 50% inhibition in vitro.

4. Conclusions

Based on the isostere concept, we designed and prepared a series of N-alkyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamides using three synthetic procedures. Although they were proposed as possible isoniazid analogues, their antimycobacterial activity was predominantly low. The most active N-hexyl-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]hydrazine-1-carboxamide served as a lead structure for further structural optimization providing 1,2-diacylhydrazines and 1,3,4-oxadiazole. However, these modifications resulted in improved, but still mild antimycobacterial properties, again below expectation. Together with this antibacterial action, these compounds lack any cytostatic properties for eukaryotic cell lines despite the presence of a trifluoromethyl group.

The hydrazinecarboxamides were found to be dual inhibitors of both acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase with IC50 values in the micromolar range. Almost all the derivatives inhibited AChE preferentially. N-Methyl, tridecyl and pentadecyl groups contributed to the most potent inhibition of AChE, while pentyl, hexyl and heptyl substituents led to an improved activity against BuChE. Molecular docking suggested the binding mode for the hydrazine-1-carboxamides, which are placed deep in the cavity in a close proximity to the active site triad.

In general, although designed as bioisosteres, new carboxamides did not behave pharmacologically in the same way as original isoniazid derivatives, in other words, they are not bioisosteres in the strict sense, but only isosteres. We identified several structure-activity relationships including the conclusion that the modification of the parent 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide scaffold provided more active compounds with interesting biological properties for further structural optimization.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jaroslava Urbanová for the language assistance provided and the staff of the Department of Organic and Bioorganic Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy in Hradec Králové, Charles University, for the technical assistance. The authors wish to acknowledge financial support from the University of Pardubice, Faculty of Chemical Technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.K.; Methodology, M.K., Š.Š., M.Š., J.S. and S.B.; Investigation, M.K., Z.B., Š.Š., K.S., M.Š., J.S. and L.H.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.K. and M.Š.; Writing—Review and Editing, Š.Š., K.S., S.B. and J.V.; Supervision, M.K., S.B. and J.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Czech Science Foundation, grant number 20-19638Y, the project EFSA-CDN (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000841) co-funded by ERDF. Szilvia Bősze wish to thank the financial support of the ELTE Institutional Excellence Program (NKFIH-1157-8/2019-DT), which is supported by the Hungarian Ministry of Human Capacities and the ELTE Thematic Excellence Programme supported by the Hungarian Ministry for Innovation and Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 1–4 are available from the authors.

References

- 1.Lima L.M., Barreiro E.J. Bioisosterism: A Useful Strategy for Molecular Modification and Drug Design. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005;12:23–49. doi: 10.2174/0929867053363540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamada Y., Kiso Y. The application of bioisosteres in drug design for novel drug discovery: Focusing on acid protease inhibitors. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2012;7:903–922. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2012.712513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonandi E., Christodoulou M.S., Fumagalli G., Perdicchia D., Rastelli G., Passarella D. The 1,2,3-triazole ring as a bioisostere in medicinal chemistry. Drug Discov. Today. 2017;22:1572–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krátký M., Bősze S., Baranyai Z., Stolaříková J., Vinšová J. Synthesis and biological evolution of hydrazones derived from 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:5185–5189. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamadar A., Duhme-Klair A.K., Vemuri K., Sritharan M., Dandawatec P., Padhye S. Synthesis, characterisation and antitubercular activities of a series of pyruvate-containing aroylhydrazones and their Cu-complexes. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:9192–9201. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30322a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vavříková E., Polanc S., Kočevar M., Horváti K., Bősze S., Stolaříková J., Vávrová K., Vinšová J. New fluorine-containing hydrazones active against MDR-tuberculosis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:4937–4945. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He X., Zhong M., Zhang T., Wu W., Wu Z., Yang J., Xiao Y., Pan Z., Qiu G., Hu X. Synthesis and anticonvulsant activity of N-3-arylamide substituted 5,5-cyclopropanespirohydantoin derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:5870–5877. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He X., Zhong M., Zhang T., Wu W., Wu Z., Xiao Y., Hu X. Synthesis and anticonvulsant activity of ethyl 1-(2-arylhydrazinecarboxamido)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropanecarboxylate derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;54:542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L., Shi L., Soars S.M., Kamps J., Yin H. Discovery of Novel Small-Molecule Inhibitors of NF-κB Signaling with Antiinflammatory and Anticancer Properties. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:5881–5899. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalinowski D.S., Sharpe P.C., Bernhardt P.V., Richardson D.R. Structure–Activity Relationships of Novel Iron Chelators for the Treatment of Iron Overload Disease: The Methyl Pyrazinylketone Isonicotinoyl Hydrazone Series. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:331–344. doi: 10.1021/jm7012562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vosátka R., Krátký M., Švarcová M., Janoušek J., Stolaříková J., Madacki J., Huszár S., Mikušová K., Korduláková J., Trejtnar F., et al. New lipophilic isoniazid derivatives and their 1,3,4-oxadiazole analogues: Synthesis, antimycobacterial activity and investigation of their mechanism of action. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;151:824–835. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rychtarčíková Z., Krátký M., Gazvoda M., Komlóová M., Polanc S., Kočevar M., Stolaříková J., Vinšová J. N-Substituted 2-Isonicotinoylhydrazinecarboxamides — New Antimycobacterial Active Molecules. Molecules. 2014;19:3851–3868. doi: 10.3390/molecules19043851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krátký M., Štěpánková Š., Houngbedji N.-H., Vosátka R., Vorčáková K., Vinšová J. 2-Hydroxy-N-phenylbenzamides and Their Esters Inhibit Acetylcholinesterase and Butyrylcholinesterase. Biomolecules. 2019;9:698. doi: 10.3390/biom9110698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahim F., Ullah H., Taha M., Wadood A., Javed M.T., Rehman W., Nawaz M., Ashraf M., Ali M., Sajid M., et al. Synthesis and in vitro acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory potential of hydrazide based Schiff bases. Bioorg. Chem. 2016;68:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krátký M., Štěpánková Š., Vorčáková K., Švarcová M., Vinšová J. Novel Cholinesterase Inhibitors Based on O-Aromatic N,N-Disubstituted Carbamates and Thiocarbamates. Molecules. 2016;21:191. doi: 10.3390/molecules21020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zdrazilova P., Stepankova S., Komers K., Ventura K., Cegan A. Half-inhibition concentrations of new cholinesterase inhibitors. Z. Nat. C. 2004;59:293–296. doi: 10.1515/znc-2004-3-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imramovsky A., Stepankova S., Vanco J., Pauk K., Monreal-Ferriz J., Vinsova J., Jampilek J. Acetylcholinesterase-Inhibiting Activity of Salicylanilide N-Alkylcarbamates and Their Molecular Docking. Molecules. 2012;17:10142–10158. doi: 10.3390/molecules170910142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Čolović M.B., Krstić D.Z., Lazarević-Pašti T.D., Bondžić A.M., Vasić V.M. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors: Pharmacology and Toxicology. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2013;11:315–335. doi: 10.2174/1570159X11311030006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torre B.G., Albericio F. The Pharmaceutical Industry in 2019. An Analysis of FDA Drug Approvals from the Perspective of Molecules. Molecules. 2020;25:745. doi: 10.3390/molecules25030745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinko G., Calic M., Bosak A., Kovarik Z. Limitation of the Ellman method: Cholinesterase activity measurement in the presence of oximes. Anal. Biochem. 2007;370:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. Autodock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krátký M., Vinšová J., Novotná E., Mandíková J., Trejtnar F., Stolaříková J. Antibacterial Activity of Salicylanilide 4-(Trifluoromethyl)-benzoates. Molecules. 2013;18:3674–3688. doi: 10.3390/molecules18043674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]