Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Little is known about elder abuse and neglect in the LGBT community, however this population faces a greater risk of abuse, and likely experiences abuse differently, and needs different resources. We conducted focus groups to investigate LGBT older adults’ perspectives on and experience with elder mistreatment.

Methods:

We conducted 3 focus groups with 26 participants recruited from senior centers dedicated to LGBT elders. A semi-structured questionnaire was developed, focus groups were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, and analyzed using grounded theory.

Results:

Key themes that emerged included: definitions and etiologies of abuse, intersectionality of discrimination from multiple minority identities, reluctance to report, and suggestions for improving outreach. Participants defined elder abuse in multiple ways including abuse from systems, and by law enforcement and medical providers. Commonly reported etiologies included: social isolation due to discrimination, internalization of stigma, intersection of discrimination from multiple minority identities, and an abuser’s desire for power and control. Participants were somewhat hesitant to report to police, however most felt strongly that they would not report abuse to their medical provider. Most reported that they would feel compelled to report if they knew someone was being abused, however they did not know who to report to. Strategies participants suggested to improve outreach included: increasing awareness about available resources, and researchers engaging with the LGBT community directly.

Conclusion:

LGBT older adults conceptualize elder abuse differently, and have different experiences with police and medical providers. Improved outreach to this potentially vulnerable population is critical to ensuring their safety.

Keywords: LGBT, elder abuse, neglect

Introduction:

Elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation are common and have serious health, social, and financial consequences. In surveys of older adults, it is estimated that 5–10% experience mistreatment each year including physical, sexual, emotional/psychological, and financial abuse, or neglect.1,2 Victimization increases the risk of mortality,3 disability,4 hospitalization,5 and institutionalization,6 and likely costs billions of dollars each year.

While research in elder mistreatment has expanded in recent years, there is a great need for a better understanding of how minority populations experience abuse and access services. Little is known about lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) older adults’ unique experiences.

LGBT older adults have faced a lifetime of discrimination;7 are more likely to have experienced sexual and intimate partner violence;8 more often have developed families of choice resulting in reliance on aging friends and non-biologically related caregivers;9 and are more likely to be HIV positive. Each of these may place them at a higher risk for mistreatment in later life as their health declines, partners and loved ones pass away, and the complications of HIV status, including HIV-related dementia, increase.10 In the limited literature available, 22.1% of LGBT adults over age 60 reported that they had been harmed, hurt or neglected by a caregiver, 25.7% reported knowing someone who had been mistreated, 11 and over 60% had experienced psychological abuse.12 In addition to being at increased risk , LGBT older adults may also have had very different relationships with service providers and likely have developed different help seeking behaviors.13 To address some of these issues, academic medical groups have provided guidance to improve care for LGBT patients and have cited the need for research and improved understanding of issues pertinent to this population.14

Our goal was to improve our understanding of LGBT older adults’ experiences with elder mistreatment, access to resources, and interactions with medical and service providers.

Methods:

We conducted focus groups with LGBT older adults to gain insight into their experiences with elder mistreatment, barriers they face in accessing resources, and ways that medical and service providers can improve outreach and support to this community. Because little is known about elder abuse among LGBT older adults, qualitative methods are ideally suited for the in-depth investigation of this complex social issue.15 Focus groups have previously been successfully used in elder abuse16–18 and intimate partner violence among younger LGBT adults.19,20

This study was conducted in collaboration with a national leader in LGBT older adult service provision, Services & Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Elders (SAGE). SAGE runs senior centers dedicated to LGBT elders in each of the 5 boroughs in New York City and has more than 5,000 members. These community centers provide services including: care management, social activities, congregate meals, adult day programs, benefits counseling, nursing services, and physical activities. SAGE leads the National Resource center on LGBT Aging to develop resources and trainings to improve the care of older adults and has been actively engaged in research focused on improving the care and treatment of LGBT older adults.21,22

Questionnaire Development

We developed a semi-structured questionnaire which was adapted iteratively throughout the research process. The initial questionnaire included questions from previous studies16,23 as well as those developed by the authors. All questions were piloted with SAGE members and staff to ensure sensitivity and comprehensibility. Questions focused on the definition of elder abuse, prevalence in the community, members’ willingness to report or reach out to services, and barriers to reporting and accessing care (Supplementary Table S1).

Participant Recruitment

Focus groups were held in June-July 2016 at SAGE centers. Participants were recruited from among SAGE members through regular programming advertisements. Participants were only included if they spoke English and were believed by SAGE staff to have the capacity to consent. A SAGE staff member with social work training (PH) observed each focus group to assist any participant who became distressed during the conversation or if a participant reported abuse. Participants were instructed to use coded identifiers rather than their names in order to maintain confidentiality. No demographic information nor prior abuse history was collected in order to foster an open environment and encourage active participation by all participants. Focus groups were audio recorded and fully transcribed. We used the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research to guide collection, analysis, and reporting of the data.24 The study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

Grounded theory was used to analyze the transcripts. This included iterative refinement of the questionnaire between each group as participant responses and discussion directed future conversations.. Themes were identified by members of the research team after iterative review of the transcripts. Once codes were developed, the research team reviewed the themes for accuracy and the transcripts were re-reviewed and coded. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. All of the key themes reached saturation by the end of the third focus group.

Results:

Three focus groups of 8–10 participants each (26 total) were conducted at three SAGE centers each representing a different borough of New York City. Participants were all SAGE members, identified as LGBT, and were over age 50.

An Expanded Definition of LGBT Elder Mistreatment

Classically, elder abuse is defined as verbal, physical, sexual, or financial abuse of an older adult by a person of trust such as a family member, friend, significant other, or caregiver1, and participants identified this as occurring in their community: “I’ve known lots of physical relation, gay relationships that have regrettably got involved with physical abuse from one to another.” However, participants reported an expanded definition of abuse for their community including ostracism from family due to LGBT status, and concerns about abuse from service providers such as medical providers and police (Table1). For example, one participant explained: “When I go to my doctor, I’m afraid to talk about who I am and ask for help…And for me, that’s a form of abuse.”

Table 1:

Themes, categories, and representative quotations from focus groups with LGBT Older Adults’ regarding the themes of definitions and etiologies of abuse.

| Categories | Representative Quotations |

|---|---|

| Definitions of Abuse | |

| Typical definition of elder abuse | “elder abuse is an… intentional act, which may be medical, physical, mental or social, … a failure to act by a caregiver or a person or people in a relationship… which causes harm to a person who is 60 plus years old “ |

| Ostracism due to LGBT status | “he move away… and then when [his mother] died the sister of all of his relatives, only they inform him that she passed away but he doesn’t go to the funeral, …because the family … doesn’t like to mingle with him. So I think it is abusive mentally” |

| “And I find that a lot of us are isolated and ostracized by our families” | |

| Service providers | “… if you have to call the police for a situation and they come and it’s SGL, same gender loving people, they think it’s a joke.” |

| “I mean it’s not the physical abuse I suffered at the hands of New York’s finest “ | |

| “When I go to my doctor, I’m afraid to talk about who I am and ask for help, and that to me is a hindrance for me getting the care that I need. And for me, that’s a form of abuse…I’m not going to get the right kind of medical care that I deserve. “ | |

| Etiologies of Abuse | |

| Desire for Power and Control | “I think it’s a power trip that people in terms of if they feel inferior it helps their self-definition to hurt someone lower than themselves.” |

| Cycles of Family Violence | “But besides that, we’ve got to, we’ve really got to go back into our family and our history and people in general because abuse just doesn’t start … as a child, some of us are abused by our parents … They could be hating for whatever reason, but when they grow, as a child they’re abused, and they bring that up through the ages with the kids beating up their kids, the kids beating up their kids, and it goes up on the line. It’s just not one, bad thing, it’s ongoing. “ |

| Abuse due to increased dependency and changing roles | “The grown children might not have the patience. It’s like when… the children were small you had so much patience to teach them this…but when you get up in age they don’t have that patience.” |

| “I think a lot of times through the years, I mean, it was loving and everything, but after while when one gets kind of ill.. they become like co-habitating… it’s like you’re in a prison without bars. You want to leave, but there’s no place to go; you’re up in age now. So you have to deal with whatever happens…. And you resent that… and the loving that you had before, it’s kind of like fades away.” | |

| Increased victimization due to LGBT status & aging | “And the answer is there are still people today who think that they can get away with… abuse towards homosexuals via the senior.” |

| “But I bet if you took a survey, you’d find there’s a lot of still harbored resentment against this community and because of the resentment… the LGBT community is much more susceptible to abuse and then when you become elderly and frail and defenseless, even more.” | |

| “We have more than one thing to fight against. The discrimination of being LGBT and… then you have the double whammy of being elderly.” | |

| Isolation of family & lack of advocates | “And I find that a lot of us are isolated and ostracized by our families, so when we have to depend on nursing homes and medical facilities and we don’t have anybody to advocate and come and visit us to make sure that we’re alright and that things are going fine for us, those are the times when we are abused. You see it happening all the time, you know… riddled with bed sores because nobody cares. Nobody’s visiting, nobody’s taking heed to what’s happening to the older adult in the community.” |

| Providers’ communication | “When I go, “What’s your pain level?” It’s so and so. Okay, bah, bah, bah, into the computer. Alright, bah, bah, bah, you’re out.” |

| Medical P roviders Personal Bias | “My mother was in a nursing home, 95, terrible problem with her knee. I went out and I found a doctor in the hall…he said to my mother, ‘Alright, what’s the problem?’ She says, ‘My left knee is in terrible pain,’ so the doctor didn’t give her anything…’What do you want at your age? You’re 95.” |

| “Also we need to be careful when other gay people go especially to the doctors…Try to let them know that you are gay and that way they… comfortable to take care of us because some of them no” | |

| Under-resourced Long Term Care | “Because my impression is that a lot of people were hired because economically it was cheaper to get people who are less qualified.” |

Etiologies of abuse

Participants identified multiple etiologies including: the desire for power and control; cycles of family violence; changing roles and increased dependency; the intersection of LGBT and aging identity; isolation of family and lack of advocates; and discrimination by medical providers (Table 1). The intersection of being LGBT and aging was often highlighted as increasing the risk for abuse: “We have more than one thing to fight against. The discrimination of being LGBT and … then you have the double whammy of being elderly.” This was of great concern as participants were worried that some may believe that they could “get away with… abuse towards homosexuals via the senior” and this may represent a different etiology unique to their community. Participants also identified causes of abuse from medical providers including lack of communication skills, personal biases including both heteronormative and ageist beliefs, and under resourced long term care options that contribute to psychological abuse and neglect.

Reaching out for Help

Many participants reported willingness to reach out for help and advocate for themselves, while others reported nervousness about reaching out to law enforcement or other providers (Table 2). Participants also recognized that while they may be very willing and able to advocate for themselves at the time of the focus groups, this may greatly change if they become frail or cognitively impaired and dependent on others. Additionally, participants reported a great willingness to advocate on the behalf of others, and several identified themselves as “fighters” who could help others as one participant described: “You see another human being being battered and you want to do something”.

Table 2:

Themes, categories and representative quotations from focus groups with LGBT Older Adults’ regarding the themes reaching out for help, barriers to accessing services, and potential solutions

| Categories | Representative Quotations |

|---|---|

| Reaching out for Help | |

| Willing to advocate for self | “I always pray I have my right mind all the time because when you don’t have your mind then you know, your body might be there, but you still got to depend on these people, but then they start treating you a certain way where, let’s say I have my right mind now, it’s something somebody told abuse to me, I can go to the police and tell them or I can go someplace else and tell them….But when I get much older, I may not have that type of mind. And I hope and pray I always have that mind.” |

| Willing to advocate for others | “And you know, you say, “Well, it’s not my problem. Do I or don’t I want to get involved in somebody else’s domestic quarrels?” But if you see it, how can you not react? I mean … you see another human being being battered and you want to do something” |

| Barriers to Accessing Services | |

| Not knowing who to call | “Participant 7: And I have witnessed these kind of things happening, so we need to know who do you call if you can’t call a police officer to address an issue? Who do you call? Participant 8: Ghostbusters. Participant 7: Oh, Ghostbusters? Oh, do you know, what do you do?” |

| Participant X:”That’s good to know. I didn’t realize 311” Participant Y:”Right, the trick is if… I heard about elder abuse from my friend in the nursing home.. then you call 3–1-1, yeah. The cops don’t need to be disturbed with…they have enough trouble.” | |

| Lack of housing options | “What I fear is that if I have to go into a nursing home and you find out that I’m a gay person and they’re not accepting of that, how will I be treated? So, that’s a fear that I have.” |

| “They usually do fear going [to a nursing home]… because they might have seen it one time visiting a nursing home how they’re really treated ….and they’re just sitting there with food sitting in front of them. No one’s helping them to eat it… I might stay at home and be abused rather than be abused you know by other strangers.” | |

| Denial as coping strategy | “She has fear in her, but she’s saying to herself, if I don’t say anything it will go away. You know, and that’s, that’s their form of healing. ….. You just covered it up; but it’s always there. Because if you talk about it, then it becomes more painful….. Leave it alone…. I won’t bother with it, it don’t bother me. Even though they always still remember it.” |

| Potential Solutions | |

| Using review committees to discuss discrimination | “But I suppose there are committees on morbidity, okay…. I don’t see any reason why they shouldn’t use the same kind of committee structure that the medical staff are familiar with to police their behavior.” |

| Interviewing patients alone & repeatedly asking | “Maybe as far as like noticing their conversations, things that, you know, stir up conversations without them knowing what you’re really getting at and just look out for the answers and, you know, just kind of watch out for it and then …there’s stuff that you might be able to do.” |

| Extending existing programs | “I sit in my own neighborhood right up the street … my folding chair that I usually take to the beach, putting it in my neighborhood and just watching and, you know, anybody, you know, I just pull out my phone and say, “Hey, you know, there’s something going on here.” …so if we had one less case of abuse or well, I mean it could be a mugging, that’s an abuse, or a robbery. If we had one less, then I say it was successful.” |

| “Yeah. Right now the city is, I think, only giving [cell phones] to abused women…Okay. But I guess abused anybody should get those little phones. The city has a huge free supply of them. Everybody throws them out. They get programmed for 9–1-1 push button.” | |

| Improving mental health care | “I think what you all need to really focus on as a medical profession is psychiatry, psychological, and… mental abuse.” |

| Desire to work with researchers | “Our doctors, our lawyers, you know, our professional people, and I thank you for coming out and…Moderator: Thank you for having me. Participant 7: Yes, and addressing this issue because if you don’t know and if you don’t come out and do these kind of things and listen, you won’t know what to do.” |

Barriers to Reporting and Accessing Services

Participants reported a multitude of factors that created barriers to reporting and accessing services (Table 2). Many participants reported distrust of police or medical providers, others merely didn’t know who to talk to or call if they had a concern or problem, for example: “Participant 7: who do you call if you can’t call a police officer to address an issue? Who do you call? Participant 8: Ghostbusters.”

Lacking alternative options for housing and care provision was often discussed as a barrier to reporting and accessing services. Many participants felt that as members of the LGBT community ending up in a nursing home may be a worse than dealing with the abuse from one’s family, as one described “ I might stay at home and be abused rather than be abused … by other strangers”. Another barrier discussed was the feeling that by reporting the abuse, the victim would have to acknowledge that it was real and that denial often can serve as an important coping mechanism.

Potential Solutions

Participants had ideas for solutions and expressed a great willingness to work with researchers (Table 2). Specifically recommendations were made to improve medical providers’ interaction with LGBT older adults including: using review committees to discuss issues of discrimination, interviewing patients alone, and being persistent in asking patients about abuse.

Recommendations for community members focused on extending existing programs such as neighborhood watch or cell phone applications which can record instances of abuse. Participants also suggested solutions that addressed what they considered to be the root of the problem, such as mental illness among perpetrators and ignorance on the part of service providers.

Concerns about Other Types of Victimization

In addition to elder abuse, many participants were very concerned about the potential for violence at the hands of strangers; being targeted for mass violence; and having inadequate support from social safety net systems. For example, the shooting in Orlando that occurred before the focus groups took place concerned some that gay communities may be particularly targeted for violence, and that older members of their community may be more vulnerable to this violence. As one participant explained: “I can now take my feelings, my prejudices and I can use them against you because you’re harmless, you’re defenseless.”

Discussion:

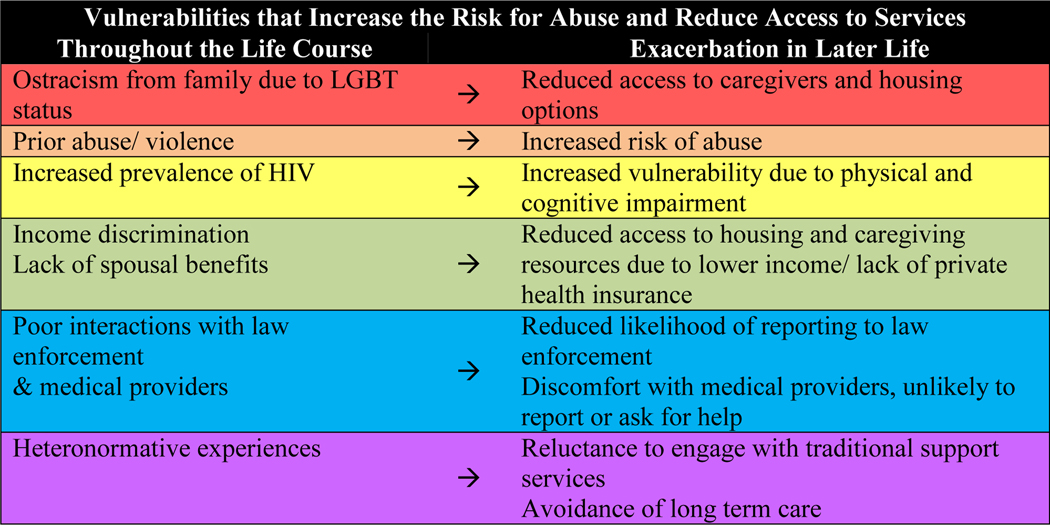

Members of SAGE participating in these focus groups reported themes previously described in other populations and also highlighted perspectives and experiences unique to their LGBT identity and lives. They defined elder abuse in ways that are broader than definitions currently used, identified numerous etiologies for abuse specific to their communities, and proposed potential solutions to barriers for accessing services and care. In addition, they also reported concerns about other types of victimization that have not been explored in the elder justice literature to date. Overall, participants described experiences from both early and later life that are different because they are LGBT, are often exacerbated by the aging process, and increase their vulnerability to abuse and reduced the likelihood that they would report (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Vulnerabilities that increase the risk of abuse and reduce likelihood to report elder abuse throughout the life course that are exacerbated in later life in the LGBT community

Participants defined, identified etiologies and barriers for reporting, and suggested solutions for elder abuse that have been previously reported in the literature for other populations. Family violence was a central concern of participants and many felt that this was due to shifting roles and increased care burden as loved ones aged, while others reported mental illness playing a large role in the etiology of this type of abuse. Many discussed that cycles of family violence exist within the LGBT community and are perhaps further exacerbated by their LGBT identity and the stigma that surrounds it highlighting how the intersections of age and LGBT identity can increase risk. Barriers to reporting elder abuse were also similar to the general population and included: a lack of housing or care options; shame, denial, and guilt; and a desire to maintain family connections.25

The particular lack of options for housing and care provision was often cited as a reason that an older LGBT adult may not choose to report.13 Unfortunately, for many elder abuse victims the safest discharge is often placement in a long term care setting, and elder abuse shelters are often operated out of nursing facilities.26 While this may make some people physically safer, these settings can be particularly difficult for LGBT older adults who may receive inadequate care and social isolation from other residents due to their sexual orientation.10,27,28 Additionally, LGBT older adults may have more limited informal caregiver networks as many did not have or adopt children and lost partners and friends in the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s thus limiting their options for safe housing and caregivers. The fear of long term care, both from their perceived increased risk of abuse due to being LGBT and from experiences with loved ones whom they perceived had received inadequate care was cited by many participants as a key reason not to ask for help.

If an older LGBT victim tries to access services in the community, they may also face unique barriers. Domestic violence service providers such as shelters, who predominantly serve younger victims, feel unprepared to serve LGBT adults often citing a lack of training, funding, or dedicated resources for victims of same-sex partners or male victims of intimate partner violence.29 Most importantly victims themselves have found these resources to be unhelpful, and in some cases even harmful, and often turn to family of choice members first.19,20 Older adults trying to access these resources may face the dual challenge of being an older adult and LGBT, both of which these providers may be uncomfortable in serving.

In each group participants were concerned with, and many had experienced, abuse from medical providers replicating concerns reported in prior studies.12 This varied from verbally derisive or discriminatory comments to providing inadequate care. This relationship with the medical system may be rooted in history for many participants as they have experienced a very different health care system than their heterosexual peers. While great strides have been made, this population grew up during a time where homosexuality was illegal7 and considered a mental illness,30 and for many people, law enforcement and medical professionals helped to further victimize, rather than advocate for this community. As such, LGBT older adults’ relationships with service providers may be drastically different than non-LGBT older adults and younger LGBT adults, and may impact their willingness to seek help if they were in an abusive situation. While the laws have changed and the medical profession has worked to rectify some of these relationships,14 these efforts have been recent and many LGBT older adults may still face discrimination in the doctor’s office. In a recent survey 40% of LGBT people ages 60–75 said their doctor does not know their sexual orientation,24 and 46% of transsexual older adults have reported being denied or provided inferior healthcare because of their gender identity.21,31 The participants in our study reported discomfort with their health care providers, particularly around how open to be about their LGBT identity, and were concerned about this impacting their medical care. This greatly impacted their willingness to report abuse, particularly if the abuse were related to their LGBT status.

Best practices for providing medical care for older LGBT adults can be found from several sources. Fredriksen- Goldsen ,et. al provide recommendations to providers caring for older LGBT adults to improve cultural competency including examining their own attitudes about LGBT communities and understanding the historical and social context that LGBT patients live in.32 Providers can also take simple steps to provide a more inclusive care setting including posting signage indicating an inclusive environment, adjusting social history questions to ask about family of choice rather than just biological family, and adjusting forms to identify gender identity.13,33,34 While universal screening in primary care is not currently recommended for elder abuse,35 the Elder Abuse Suspicion Index, may be used to start a conversation with patients about abuse.36 There are a number of resources available to older adults experiencing abuse which can be found through the National Center for Elder Abuse, and specialized resources can be found through local Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE) programs.

Other service providers and service systems as a whole also concerned participants. LGBT older adults are more likely to have lower incomes due to a lifetime of discrimination due to their LGBT status, are less likely to have traditional spousal support from retirement and health plans due to this discrimination, and depend more on social service programs.29 The budget constraints of these programs were particularly concerning to participants in the Bronx, one of the lower income boroughs in New York City. Participants often felt that the limitations of these programs were a form of systemic abuse as their daily needs were commonly unmet by the support offered by programs such as Medicaid.

Many LGBT older adults have faced victimization throughout their lives, often in the form of stranger or street violence and many participants worried that this type of violence would escalate in later life as LGBT older adults became easier targets for homophobic hate crimes. They felt that much of this was rooted in discrimination and bias that will hopefully change as legalization of gay marriage and other rights that have been won in recent years start to impact the culture. Most would willingly report this kind of abuse and had suggestions to use technology or neighborhood watch programs to help ensure the safety of everyone in the community.

Participants were able to recommend concrete ways that service providers could help to start identifying and treating this kind of abuse, and felt that this was important. Some suggested improvements included: interviewing older adults alone, being persistent in asking about their home life, believing older adults when they do report, and treating the mental illnesses of perpetrators. In addition, they suggested using systems already in place to improve medical care, such as using a morbidity and mortality review format for complaints or incidents of discrimination in health care. They also expressed an understanding of budgetary limitations in the health care system and felt this lead to inadequate training and hiring unqualified staff, particularly in long term care, which lead to abuse and discrimination.

Despite their complex history with all types of service providers, including medical providers, participants were very willing to engage with researchers from a medical institution, and wanted to improve things for themselves and the next generation. Participants profusely thanked researchers for coming to them and eliciting their opinions, and expressed their desire to engage more actively with researchers and providers who want to serve the LGBT community.

Limitations:

This study was only conducted in three boroughs of New York City, limiting its applicability to other populations and contexts. New York has the largest network of LGBT senior centers in the country making it an ideal place to start the investigation of this topic, however it also has a larger LGBT community and a fundamentally different culture than other places in the country and the world where LGBT populations may face more discrimination and violence. Further investigation in the other parts of the country, including in rural areas, are necessary. In addition, while we were able to talk to many participants, demographics and prior abuse history were not collected, making it difficult to assess whether a broad range of perspectives within the LGBT community were represented. Further studies should seek to engage transgender, bisexual, and other LGBT minority groups.

Conclusion:

LGBT older adults identified multiple types of abuse, described etiologies, and proposed concrete solutions to these issues. Participants also reported being willing to engage with researchers and service providers, including medical providers, to improve identification of and response to elder abuse in this community. In each group, it was clear that the intersection between LGBT status and aging greatly impacted the risk for abuse, the experience of abuse, and the services that were perceived to be available and acceptable for this potentially vulnerable population. Future research should include older adults from other LGBT communities to further understand this complicated issue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Sponsor role: This project was supported by the American Federation of Aging Research, Medical Student Training in Aging Research grant. Tony Rosen’s participation was supported by a GEMSSTAR (Grants for Early Medical and Surgical Subspecialists’ Transition to Aging Research) grant (R03 AG048109) and a Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders Career Development Award in Aging (K76 AG054866) from the National Institute on Aging. He is also the recipient of a Jahnigen Career Development Award, supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Geriatrics Society, the Emergency Medicine Foundation, and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. The sponsors were not involved in the study design, data collection, nor manuscript preparation.

Previously Presented: 2017 Annual Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society, Presidential Poster Session

Funding: Elizabeth Bloemen’s participation was supported by MSTAR (Medical Student Training in Aging Research) grant from the American Federation for Aging Research. Tony Rosen’s participation was supported by a GEMSSTAR (Grants for Early Medical and Surgical Subspecialists’ Transition to Aging Research) grant (R03 AG048109) and a Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders Career Development Award in Aging (K76 AG054866) from the National Institute on Aging. He is also the recipient of a Jahnigen Career Development Award, supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Geriatrics Society, the Emergency Medicine Foundation, and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

End Notes:

- 1.Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, et al. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: the National Elder Mistreatment Study. American journal of public health 2010;100:292–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yon Y, Mikton CR, Gassoumis ZD, Wilber KH. Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global health 2017;5:e147–e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA, Charlson ME. The mortality of elder mistreatment. JAMA 1998;280:428–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyer CB, Pavlik VN, Murphy KP, Hyman DJ. The high prevalence of depression and dementia in elder abuse or neglect. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2000;48:205–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong X, Simon MA. Elder abuse as a risk factor for hospitalization in older persons. JAMA internal medicine 2013;173:911–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong X, Simon MA. Association between Reported Elder Abuse and Rates of Admission to Skilled Nursing Facilities: Findings from a Longitudinal Population-Based Cohort Study. Gerontology 2013;59:464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. Resilience and Disparities among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults. The Public policy and aging report 2011;21:3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikel L. Walters JC, Breiding Matthew J. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czaja SJ, Sabbag S, Lee CC, et al. Concerns about aging and caregiving among middle-aged and older lesbian and gay adults. Aging & mental health 2015:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westwood S. Abus and older lesbian, gay bisexual, and trans (LGBT) people: a commentary and research agenda. Journal of elder abuse & neglect 2019;31:97–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossman AH, Frank JA, Graziano MJ, et al. Domestic harm and neglect among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Journal of homosexuality 2014;61:1649–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook-Daniels L, Munson M. Sexual violence, elder abuse, and sexuality of transgender adults, age 50+: Results of three surveys. Journal of GLBT Family Studies 2010;6:142–77. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook-Daniels L. Lesbian, gay male, bisexual and transgendered elders: Elder abuse and neglect issues. Journal of elder abuse & neglect 1998;9:35–49. [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Geriatrics Society Ethics C. American Geriatrics Society care of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults position statement: American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2015;63:423–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krumholz HM, Bradley EH, Curry LA. Promoting publication of rigorous qualitative research. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes 2013;6:133–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ploeg J, Lohfeld L, Walsh CA. What is “elder abuse”? Voices from the margin: the views of underrepresented Canadian older adults. Journal of elder abuse & neglect 2013;25:396–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mysyuk Y, Westendorp RG, Lindenberg J. Perspectives on the Etiology of Violence in Later Life. Journal of interpersonal violence 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enguidanos S, DeLiema M, Aguilar I, Lambrinos J, Wilber K. Multicultural voices: Attitudes of older adults in the United States about elder mistreatment. Ageing and society 2014;34:877–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guadalupe-Diaz XL, Jasinski J. “I Wasn’t a Priority, I Wasn’t a Victim”: Challenges in Help Seeking for Transgender Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Violence against women 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turell SC, Herrmann MM. “Family” support for family violence: exploring community support systems for lesbian and bisexual women who have experienced abuse. Journal of lesbian studies 2008;12:211–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espinoza R. Out & Visible: The Experiences and Attitudes of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults, Ages 45–75. Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott French LC-D, Michael Munson, Jody Herman, Kari Greene, Emily Greytak. Inclusive Questions for Older Adults: A Practical Guide to Collecting Data on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. National Resource Center on LGBT Aging 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong X, Chang ES, Wong E, Wong B, Simon MA. How do U.S. Chinese older adults view elder mistreatment?: findings from a community-based participatory research study. Journal of aging and health 2011;23:289–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International journal for quality in health care : journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study: Self-Reported Prevalence and Documented Case Surveys 2012. (Accessed October 13, 2013, at http://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/Under%20the%20Radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf.)

- 26.Reingold DA. An elder abuse shelter program: build it and they will come, a long term care based program to address elder abuse in the community. Journal of gerontological social work 2006;46:123–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Movement Advancement Project SAfGE, Center for American Progress. LGBT Older Adults and Inhospitable Care Environments. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stein GL, Beckerman NL, Sherman PA. Lesbian and gay elders and long-term care: Identifying the unique psychosocial perspectives and challenges. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 2010;53:421–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ford CL, Slavin T, Hilton KL, Holt SL. Intimate partner violence prevention services and resources in Los Angeles: issues, needs, and challenges for assisting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clients. Health promotion practice 2013;14:841–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drescher J. Queer diagnoses revisited: The past and future of homosexuality and gender diagnoses in DSM and ICD. International review of psychiatry 2015;27:386–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Cook-Daniels L, Kim HJ, et al. Physical and mental health of transgender older adults: an at-risk and underserved population. The Gerontologist 2014;54:488–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Jen S, Bryan AEB, Goldsen J. Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Other Dementias in the Lives of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Older Adults and Their Caregivers: Needs and Competencies. Journal of applied gerontology : the official journal of the Southern Gerontological Society 2018;37:545–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radix A, Maingi S. LGBT Cultural Competence and Interventions to Help Oncology Nurses and Other Health Care Providers. Seminars in oncology nursing 2018;34:80–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cloyes KG, Hull W, Davis A. Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers. Seminars in oncology nursing 2018;34:60–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Final Update Summary: Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse of Elderly and Vulnerable Adults: Screening. . 2016. 2019, at https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/intimate-partner-violence-and-abuse-of-elderly-and-vulnerable-adults-screening.)

- 36.Yaffe MJ, Wolfson C, Lithwick M, Weiss D. Development and validation of a tool to improve physician identification of elder abuse: The Elder Abuse Suspicion Index (EASI)©. Journal of elder abuse & neglect 2008;20:276–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.