Abstract

Background

Pediatric phase I oncology trials have historically focused on safety and toxicity, with objective response rates (ORRs) <10%. Recently, with an emphasis on targeted approaches, response rates may have changed. We analyzed outcomes of recent phase I pediatric oncology trials.

Materials and Methods

This was a systematic review of phase I pediatric oncology trials published in 2012–2017, identified through PubMed and EMBASE searches conducted on March 14, 2018. Selection criteria included full‐text articles with a pediatric population, cancer diagnosis, and a dose escalation schema. Each publication was evaluated for patient characteristics, therapy type, trial design, toxicity, and response.

Results

Of 3,431 citations, 109 studies (2,713 patients) met eligibility criteria. Of these, 78 (72%) trials incorporated targeted therapies. Median age at enrollment/trial was 11 years (range 3–21 years). There were 2,471 patients (91%) evaluable for toxicity, of whom 300 (12.1%) experienced dose‐limiting toxicity (DLT). Of 2,143 patients evaluable for response, 327 (15.3%) demonstrated an objective response. Forty‐three (39%) trials had no objective responses. Nineteen trials (17%) had an ORR >25%, of which 11 were targeted trials and 8 were combination cytotoxic trials. Targeted trials demonstrated a lower DLT rate compared with cytotoxic trials (10.6% vs. 14.7%; p = .003) with similar ORRs (15.0% vs. 15.9%; p = .58).

Conclusion

Pediatric oncology phase I trials in the current treatment era have an acceptable DLT rate and a pooled ORR of 15.3%. A subset of trials with target‐specific enrollment or combination cytotoxic therapies showed high response rates, highlighting the importance of these strategies in early phase trials.

Implications for Practice

Enrollment in phase I oncology trials is crucial for development of novel therapies. This systematic review of phase I pediatric oncology trials provides an assessment of outcomes of phase I trials in children, with a specific focus on the impact of targeted therapies. These data may aid in evaluating the landscape of current phase I options for patients and enable more informed communication regarding risk and benefit of phase I clinical trial participation. The results also suggest that, in the current treatment era, there is a rationale to increase earlier access to targeted therapy trials for this refractory patient population.

Keywords: Phase I, Pediatric oncology, Targeted therapy, Systematic review, Toxicity, Outcome

Short abstract

This systematic review of pediatric oncology phase I trials describes the safety profile and response outcomes from recent trials, comparing cytotoxic and targeted trials in the era of targeted therapies.

Introduction

Although considerable progress has been made in the treatment of pediatric cancer in recent decades, 20%–25% of children will still die because of their disease, and an estimated 40% of pediatric cancer survivors will face significant late treatment effects 1, 2. Novel therapies are needed to improve upon existing treatment options 3.

With the primary objectives of describing drug toxicities, determining the maximum tolerated dose (MTD), and assessing the pharmacokinetics, phase I oncology studies represent the crucial first step to evaluate the clinical impact of a novel anticancer agent. With the recognition that pediatric patients constitute an inherently vulnerable patient population, pediatric phase I studies are frequently initiated after determination of the adult safety profile. This historical pattern is advantageous in that data from adult patients can inform the design of the pediatric trial, which decreases the likelihood that a pediatric patient would be enrolled at a biologically ineffective dose or have undue toxicity without the potential of benefit. At the same time, this introduces additional delay in the timeline of pediatric drug development 4. Furthermore, given different disease subtypes and biologic variation, early determination of a drug's inactivity in an adult population for an adult cancer may negatively affect development of pediatric trials, even though the agent may not have the same outcome in a pediatric cancer with a different underlying biology 5.

Whereas phase I trials historically focused on conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy agents, the majority of current and future early phase pediatric oncology trials investigate targeted drugs and/or incorporate earlier combinatorial strategies, often combining targeted agents with chemotherapy 3, 5, 6, 7, 8. Several recent prior reviews examining the pediatric oncology phase I experience have been limited by small number of studies included, restriction to a single institution or treatment center experience, or restriction to a specific subpopulation of pediatric oncology studies 9, 10, 11. There has been a relative paucity of reviews comparing safety and response data for cytotoxic versus targeted early phase trials 12, 13.

With an increasing number of targeted agents being tested in phase I trials, either as single agents or in combination, the landscape of phase I pediatric oncology trials continues to evolve. To this end, addressing in a comprehensive manner the characteristics and outcomes of pediatric patients enrolled in phase I oncology trials in the current treatment era would be informative. We undertook a systematic review of pediatric oncology phase I trials published from 2012 through 2017 and report on our findings, describing the safety profile and response outcomes in pediatric oncology phase I trials and comparing cytotoxic and targeted phase I trials in the era of targeted therapies.

Materials and Methods

Study Design: Search Strategy and Study Eligibility Criteria

We systematically searched PubMed and EMBASE for peer‐reviewed phase I pediatric clinical oncology trials published between January 1, 2012, and March 14, 2018. We chose the start date of 2012 in order to ensure that an adequate number of studies identified were most reflective of the current treatment era. Studies were identified through a PubMed and EMBASE search for English‐language reports using strategies that included key words and relevant MeSH and Emtree terms. Our exact literature search strategies in PubMed and EMBASE are presented in supplemental online Table 1. We followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for this protocol‐based systematic review (supplemental online Table 2). The protocol is available upon request from the authors.

Included studies were pediatric oncology phase I or phase I/II studies for which results of the phase I portion was provided separately. Key inclusion criteria were the following: (a) diagnosis of any malignancy, hematologic or solid; (b) enrollment was primarily pediatric with the majority of participants (over 80%) being aged less than 25 years, or results of a pediatric patient cohort were reported separately; and (c) assessment of toxicity of one or more drugs with a planned dose escalation schema was described. Exclusion criteria were as follows: noncancer diagnosis; trial not phase I in design or only reporting on pharmacokinetic data; no dose escalation schema; primary transplant/transplant‐related outcomes in nature; not a pediatric patient population. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined prospectively.

A single investigator assessed citations and full‐text articles for eligibility criteria. If there was any uncertainty regarding an article meeting all eligibility criteria, the article was discussed and reviewed by a second investigator to make a final determination about eligibility. The second investigator reviewed and verified key data extracted from the publications by the first investigator.

Selected papers were coded according to the following categories with the use of a data extraction form, which collected the following data if reported: patient enrollment characteristics, eligible diagnoses, study drug characteristics including single or multiple agents, drug(s) type (targeted, cytotoxic, or combination of targeted and cytotoxic agents), and route of drug delivery, dose escalation schema, toxicities, including any toxic death or other death on study, MTD/recommended phase II dose (RP2D), and response data. For manuscripts with missing response data, efforts were made to contact the corresponding author on the publication to obtain this data, but all attempts were unsuccessful. In addition, a risk of bias assessment was applied to all included articles. This risk of bias assessment focused on whether reporting bias was present, identifying if there was selective reporting or incomplete response data included in the publication.

Definitions

We prospectively developed definitions of cytotoxic and targeted trials according to the degree to which the trial was defined by either cytotoxic agents or targeted agents.

A drug was classified as “cytotoxic” if it worked by a nonspecific mechanism of action to kill rapidly dividing cells. Typically these agents interfere with DNA replication, stability, or cell division.

A drug was classified as “targeted” if the primary mechanism of action was focused on working through a specific pathway with general sparing of nontarget tissue effects. This could include immunologic targeting (e.g., CD19 targeting), signal transduction inhibition (e.g., AKT inhibition), or differentiation promotion (e.g., histone deacetylase inhibition) 4, 12. We further subdivided targeted agents into two groups: “specific” targeted therapy or “nonspecific” targeted therapy. Those targeting essential growth drivers (e.g., vandetanib for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B associated medullary thyroid carcinoma) 14 or targeting a specific cell‐surface marker (e.g., blinatumomab for acute lymphoblastic leukemia) 15 were classified as “specific” targeted therapy. Thus, drugs in the “specific” targeted therapy group had to be utilized for the purpose of targeting a specific pathway or molecule acting as a primary oncogenic driver or addressing the target in a disease population where the presence of the target was confirmed. Those targeting more general growth‐related molecules 16 were classified as “nonspecific” targeted therapy (e.g., sorafenib in children with refractory solid tumors or leukemias) 17.

Prior to any data analysis, definitions for targeted and cytotoxic trials were selected, based on the degree to which the study drug or combination of study drugs represented a targeted therapy approach. For trials of combination therapies including multiple agents, either multiagent chemotherapy, multiple targeted therapies, or a combination of chemotherapy and targeted agent(s), the trial was overall considered to be a targeted therapy trial if all agents were targeted in nature (either specific or nonspecific), or if a “specific targeted therapy” agent was included along with a chemotherapy agent.

All dose‐limiting toxicities (DLTs), as defined by the individual trials, were included. Toxic death was defined by individual trials, generally a fatal toxicity at least possibly attributable to the study drug. Response was evaluated using standard response criteria depending on the nature of included diagnoses. Objective response was generally defined as the sum of complete and partial responses, with a subset of trials including additional individual study criteria for response designations.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed enrollment characteristics using descriptive statistics. Baseline characteristics were summarized as number and percentage of patients for categorical variables and median and range for continuous variables. For each trial in the analyses, using results as presented in the included publication, the number of patients enrolled, number of toxic deaths, number of patients with DLTs, whether an MTD or RP2D was established from the trial, number of evaluable patients, number of patients with objective responses, and number of patients with stable disease were obtained and used as primary data. Pooled estimates of DLT rate were calculated by dividing the sum of all patients with a reported DLT (pooled numerator) by the sum of all patients evaluable for toxicity (pooled denominator) across all included trials. Pooled estimates of objective response rate (ORR) were calculated by dividing the sum of all patients with a reported objective response (pooled numerator) by the sum of all patients evaluable for response (pooled denominator) across all included trials.

In an exploratory manner, we compared the distributions of the outcome variables (rate of DLT and ORR), expressed as a percentage per trial as the unit of analysis, according to the categorical variables of trial type (cytotoxic vs. targeted) and relevant disease type (neuro‐oncology only vs. all other diagnoses; leukemia only vs. all other diagnoses) with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. These analyses were planned a priori. As an alternative approach to evaluate for differences between cytotoxic and targeted trial groups, we compared cytotoxic versus targeted pooled proportions with a reported DLT or objective response (as described earlier), employing a chi‐squared test on a 2×2 frequency table obtained from the pooled data. All reported p values are two tailed. Statistical analyses were performed using R software.

Results

Trial and Patient Characteristics

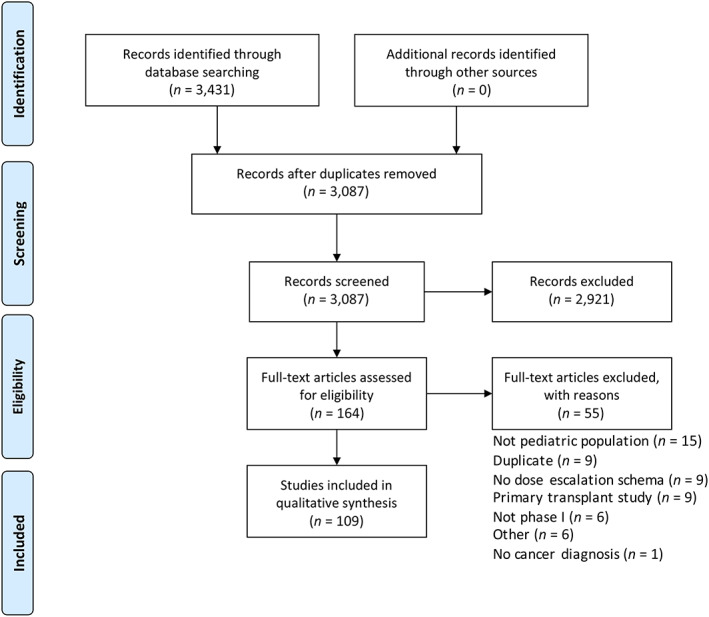

The search was conducted on March 14, 2018, and returned 3,431 abstracts, with 3,087 abstracts remaining after duplicates were removed. Of the 3,087 records screened, there were 164 full‐text articles assessed for eligibility, with 55 articles excluded based on the following reasons: trials that did not include cancer diagnosis (n = 1), trials that were not phase I in design or those that only reported on pharmacokinetic data without any associated trial outcome data (n = 6), trials without a dose escalation schema (n = 9), trials that were focused on hematopoietic stem cell transplantation/transplant‐related outcomes (n = 9), trials with an adult rather than pediatric patient population (n = 15), remaining duplicate publications (n = 9), and other (n = 6; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram demonstrates the results of the literature search and study selection process.

A total of 109 phase I pediatric oncology clinical trials met eligibility criteria. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of included trials. Seventy‐eight trials (72%) incorporated at least one targeted agent, with 61 trials (56%) considered targeted therapy trials and 48 trials (44%) considered cytotoxic therapy trials based on definitions described in the Materials and Methods section. There was a median of 21 enrolled patients per trial (range 4–79), with a median of 3 dose levels (range 1–9). The most prevalent study design employed was a 3+3 design (n = 63, 58%), with the rolling six design also commonly used (n = 24, 22%). In 94 trials (86%), an MTD and/or RP2D was established from the phase I study. For a list of all 109 included trials, please refer to supplemental online Table 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Characteristic | Total trials (n = 109), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of drugs | |

| One drug | 66 (61) |

| Two or more drugs | 43 (39) |

| Type of tumor | |

| Solid tumors (including CNS tumors) | 28 (26) |

| CNS tumors only | 21 (19) |

| Leukemia only | 19 (17) |

| Solid tumors (excluding CNS tumors) | 16 (15) |

| Neuroblastoma only | 15 (14) |

| Other | 9 (8) |

| Lymphoma only | 1 (1) |

| Study design | |

| 3+3 | 63 (58) |

| Rolling six | 24 (22) |

| Adaptive/continual reassessment method | 8 (7) |

| Other | 7 (6) |

| Not reported | 7 (6) |

| MTD/RP2D established | 94 (86) |

| Number of dose levels, median (range) | 3 (1–9) |

| Type of triala | |

| Targeted | |

| Group 1: Specific targeted agents with targeted agent dose escalation | 15 (14) |

| Group 2: Nonspecific targeted agents with targeted agent dose escalation | 40 (36) |

| Group 3: Specific targeted agents plus cytotoxic agents | 6 (6) |

| Cytotoxic | |

| Group 4: Nonspecific targeted agents plus cytotoxic agents with targeted agent dose escalation | 6 (6) |

| Group 5: Nonspecific targeted agents plus cytotoxic agents with other dose escalation | 11 (10) |

| Group 6: Cytotoxic agents only | 31 (28) |

For all trial groups (1–6), single agent or multiagent therapy combinations were included.

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; RP2D, recommended phase II dose.

Baseline characteristics of the patients enrolled are summarized in Table 2. Total enrollment was 2,713 patients, with 1,703 enrolled patients in targeted trials and 1,010 enrolled patients in cytotoxic trials. The median age at enrollment/trial was 11 years (range 3–21 years). The median number of prior regimens/trial was 2.

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Total number | Cytotoxic trials | Targeted trials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled patients, n | 2,713 | 1,010 | 1,703 |

| Patients evaluable for toxicity, n (%) | 2,471 (91) | 918 (91) | 1,553 (91) |

| Patients evaluable for response, n (%) | 2,143 (79) | 725 (72) | 1,418 (83) |

| Male patients, n (%) | 1,471 (54) | 532 (53) | 939 (55) |

| Age, median/trial (range), yearsa | 11 (3–21) | 10 (5–21) | 12 (3–19) |

| Prior regimens: median/trial (range) | 2 (0–9) | 2 (0–9) | 2 (9–6) |

| Prior radiationb | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 941 (35) | 289 (29) | 652 (38) |

| Unavailable | 57 studies | 29 studies | 28 studies |

| Prior stem cell transplantationb | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 341 (13) | 86 (9) | 255 (15) |

| Unavailable | 77 studies | 35 studies | 42 studies |

Age represents the median age reported in the trial and thus is reported as a median and range of the median ages per trial.

The number of patients who had received prior radiation or who had undergone prior stem hematopoietic stem cell transplant was difficult to assess as only a minority of studies reported these data.

Toxicity Outcome Characteristics

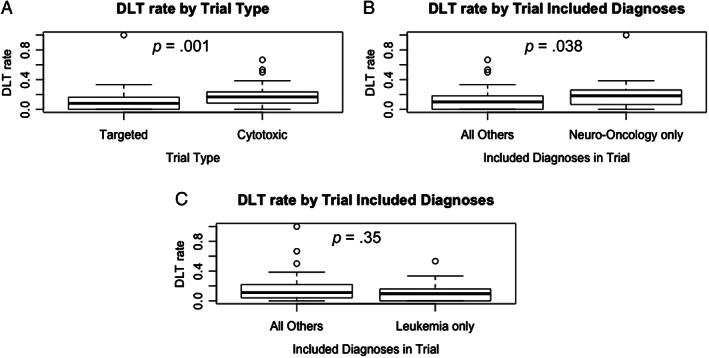

Comparison of the rate of DLT per trial (DLT/trial) between the targeted and cytotoxic trial groups indicated an association between type of therapy and rate of DLT, with a lower rate of DLT/trial among targeted therapy trials (p = .001), the median (25th percentile to 75th percentile) DLT rate for targeted trials of 8% (0%–16%) compared with 17% (8%–24%) for cytotoxic trials. When compared with other trial types, trials including only neuro‐oncology diagnoses trended toward a higher rate of DLT/trial (p = .04). Trials including only leukemia diagnoses did not have significantly different rates of DLT compared with all other trials (p = .35; Fig. 2). Across all included trials, 2,471 patients (91%) were evaluable for toxicity, of whom 300 (12.1%) experienced at least one DLT, for a pooled DLT rate of 12.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 10.9%–13.5%). Comparison between the 61 targeted trials and the 48 cytotoxic trials demonstrated a lower pooled DLT rate of 10.6% (95% CI, 9.1%–12.3%) across the targeted trial group, compared with 14.7% (95% CI, 12.5%–17.2%) for the cytotoxic trial group (p = .003). Reported study related deaths were limited (n = 3), with many studies not specifically commenting on toxic death or other death on study.

Figure 2.

The rate of DLT per trial for all included trials. (A): Targeted (n = 61) and cytotoxic (n = 48) trial groups. (B): Neuro‐oncology–only trials (n = 21) and all other trials (n = 88). (C): Leukemia‐only trials (n = 19) and all other trials (n = 90). Box‐and‐whisker plots display the 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile, with end of whiskers designating 1.5 × interquartile range (IQR). Circles depict potential outliers, for those trials with DLT rate greater than 1.5 × IQR from the median.Abbreviation: DLT, dose‐limiting toxicity.

Response Outcome Characteristics

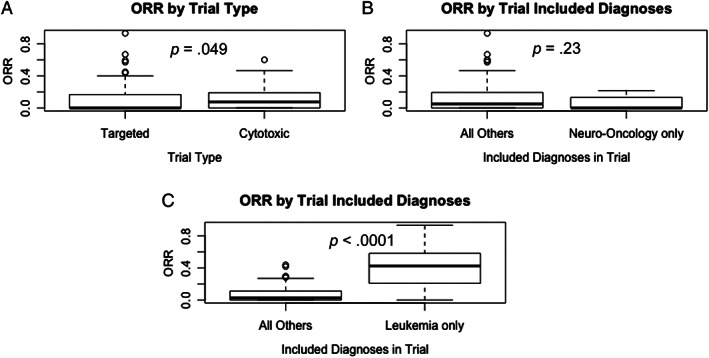

Of 2,143 patients (79%) evaluable for response in 97 trials, 327 (15.3%) demonstrated an ORR (211 complete remission [CR], 19 complete remission with incomplete count recovery [CRi], 97 partial remission [PR]). Forty‐three (39%) trials had no objective responses. ORR data was not available for 12 included studies. Trials including only leukemia diagnoses were associated with a higher ORR, the ORR per trial (ORR/trial) for leukemia trials with a median (25th percentile to 75th percentile) of 42% (22%–58%), which was significantly higher than the ORR/trial for all other trials, 3% (0%–11%) (p < .0001). For the targeted trials, the median ORR/trial (25th percentile to 75th percentile) was 0% (0%–17%) compared with the cytotoxic trials, 8% (0%–19%), with the two groups demonstrating some potential differences in the distribution of results (p = .049; Fig. 3). Nineteen trials (17%) had an ORR greater than 25% (leukemia trials, 11; solid tumor trials, 8), of which 11 were targeted trials and 8 were combination cytotoxic trials. In the targeted therapy trial group with trial ORR >25%, there was a majority of leukemia trials (n = 7). There were four leukemia trials in the cytotoxic trial group with trial ORR >25% (Table 3). Across all included trials, there were 327 patients with an objective response (CR + PR +CRi) of the 2,143 patients evaluable for response, for a pooled ORR of 15.3% (95% CI, 13.8%–16.9%). Comparison between the 61 targeted trials and the 48 cytotoxic trials demonstrated similar pooled rates of ORR: 15.0% (95% CI, 13.1%–16.9%) versus 15.9% (95% CI, 13.3%–18.7%); p = .58.

Figure 3.

The ORR per trial for all included trials. (A): Targeted (n = 61) and cytotoxic (n = 48) trial groups. (B): Neuro‐oncology–only trials (n = 21) and all other trials (n = 88). (C): Leukemia‐only trials (n = 19) and all other trials (n = 90). Box‐and‐whisker plots display the 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile, with end of whiskers designating 1.5 × interquartile range (IQR). Circles depict potential outliers, for those trials with ORR greater than 1.5 × IQR from the median.Abbreviation: ORR, objective response rate.

Table 3.

Included trials with objective response rate >25%

| Study/PMID | Trial type | Study agent(s) | Number enrolled | ORR, % | Target‐specific enrollmenta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mosse 2013/ 23598171 28 |

Targeted | Crizotinib | 79 | 27 | No |

|

DuBois 2015/ 25602966 29 |

Targeted | MIBG, irinotecan, vincristine | 32 | 28 | Yes |

|

Ladenstein 2013/ 23924804 30 |

Targeted | Ch14.18 antibody | 16 | 29 | Yes |

|

Wayne 2017/ 28983018 31 |

Targeted | Moxetumomab | 55 | 32 | Yes |

|

Raetz 2014/ 24276047 32 |

Targeted | EZN‐3042 | 6 | 40 | No |

|

Fox 2013/ 23766359 14 |

Targeted | Vandetanib | 16 | 44 | Yes |

|

Zwann 2013/ 23715577 33 |

Targeted | Dasatinib | 63 | 45 | No |

|

Fry 2018/ 29155426 34 |

Targeted | CD22 CAR T cells | 21 | 57 | Yes |

|

von Stackelberg 2016/ 27998223 15 |

Targeted | Blinatumomab | 49 | 59 | Yes |

|

Lee 2015/ 25319501 35 |

Targeted | CD19 CAR T cells | 21 | 67 | Yes |

|

Gardner 2017/ 28408462 36 |

Targeted | CD19 CAR T cells | 43 | 93 | Yes |

|

Tran 2015/ 25551355 37 |

Cytotoxic | Oxaliplatin, doxorubicin | 7 | 29 | N/A |

|

Navid 2013/ 23143218 38 |

Cytotoxic | Bevacizumab, sorafenib, cyclophosphamide | 19 | 29 | N/A |

|

Mascarenhas 2013/ 23335436 39 |

Cytotoxic | Oxaliplatin, doxorubicin | 17 | 29 | N/A |

|

Elmoneim 2012/ 22887831 40 |

Cytotoxic | Clofarabine, cytarabine | 13 | 36 | N/A |

|

Venkatramani 2013/ 23894304 41 |

Cytotoxic | Vincristine, irinotecan, temozolomide, bevacizumab | 13 | 42 | N/A |

| Cooper 2014/ 24771494 42 | Cytotoxic | Clofarabine, cytarabine | 51 | 46 | N/A |

|

Rheingold 2017/ 28295182 43 |

Cytotoxic | Temsirolimus, re‐induction chemotherapy | 16 | 47 | N/A |

|

Alexander 2016/ 27507877 44 |

Cytotoxic | Selinexor, fludarabine, cytarabine | 18 | 60 | N/A |

Target‐specific enrollment only applicable to targeted therapy trials. N/A designated for all cytotoxic trials.

Abbreviations: CAR, chimeric‐antigen receptor; MIBG, metaiodobenzylguanidine; N/A, not applicable; ORR, objective response rate; PMID, PubMed identifier.

Discussion

Considering the changing treatment landscape in phase I pediatric oncology trials with a greater emphasis on inclusion of targeted agents, we aimed to explore trial outcomes in the current treatment era, with a particular focus on evaluating toxicity profiles and response rates. In this systematic review of phase I pediatric oncology trials in the era of targeted therapies, we found that targeted therapy trials were associated with lower rates of DLT than cytotoxic therapy trials, while achieving comparable objective response rates.

The safety profile in pediatric oncology phase I trials is primarily characterized by rate of DLT. In our analysis, we found that DLT rates were low in phase I trials, with a pooled DLT rate of 12.1% for all included trials. This is generally regarded as an acceptable rate of DLT, with other comparable analyses reviewing the phase I pediatric oncology trial literature reporting a similar or higher rate of DLT for the study group in question (supplemental online Table 4) 4, 9, 10, 11, 12. When comparing trials according to type of therapy, we found that the cytotoxic trial group had a higher pooled estimate of DLT rate (14.7%) as compared with the targeted therapy trial group, where the pooled DLT rate was 10.6% (p = .003). Likewise, a comparison of DLT rates per trial between targeted and cytotoxic trial groups demonstrated an increased rate of DLT per trial in the cytotoxic trial group (p = .001). Similar findings were also reported by Dorris et al. in their recent systematic review of solid tumor phase I trials in pediatric oncology 12. These data support that the toxicity profile may be different for phase I trials in the era of targeted therapy. The median number of dose levels per study was three, lower than the four median dose levels reported by a study of pediatric oncology phase I trial study conduct efficiency. The decline in the median number of dose levels, especially given that an MTD/RP2D was established in the majority of the included trials (n = 94), is encouraging in light of the conclusion that a maximum of four dose levels could substantively shorten study timelines without any compromise in patient safety 4.

Although ORR is not a primary objective of phase I studies, response rates in such trials may serve as early indicator of clinical activity, prompting further evaluation in a phase II setting. The pooled ORR for all included trials in this study was 15.3%. This is in contrast to the 9.6% pooled ORR previously reported in a study published in 2005, which included trials published from the prior decade (years 1990 to 2004) 4. Overall, pediatric oncology phase I trials in the current treatment era demonstrate a greater response rate compared with those previously reported in the literature, when targeted therapies were less prevalent.

Pooled estimates of ORR for the cytotoxic trial group (15.9%) as compared with the targeted trial group (15.0%), were similar (p = .58), whereas a comparison of ORR using data on a per trial basis between targeted and cytotoxic trials groups demonstrates some potential differences in the distribution of results (p = .049). In addition to basing this on results per trial with varying numbers of subjects per study, there was a high degree of variability of trial response rates in the targeted trial group, which included more trials with an exceptionally high ORR, as well as a higher proportion of trials with no objective responses.

Of note, a subset of included trials reported objective response rates of >25%, which signifies an unprecedented response rate in most phase I studies based on historical outcomes (Table 3). Overall, phase I leukemia trials accounted for a large proportion of the trials with these higher response rates and were associated with significantly higher ORRs per trial with a median (25th percentile to 75th percentile) of 42% (22%–58%), compared with 3% (0%–11%) for all other trials (p < .0001). In a recent systematic review and meta‐analysis approach, a significantly higher overall response rate in hematological malignancies than in solid tumors was similarly reported 13. Of note in this study, the higher trial response rates among the leukemia trial population did not correspond to a higher rate of DLT per trial in this trial subgroup (p = .35). Cellular therapy, specifically chimeric‐antigen receptor (CAR) T‐cell therapy was featured prominently in this trial subset with ORR >25%, with 4 of the 11 targeted therapy trials being CAR T‐cell trials for relapsed/refractory leukemia. In 8 of the 11 targeted therapy trials, there was enrollment according to presence of the relevant target. The impressive success of these novel targeted therapies, even in the phase I setting, must be tempered with the high cost, making such therapies potentially cost‐prohibitive and difficult to access in the current era. Future directions should focus on improving access and lowering cost 18, 19. Of the eight cytotoxic trials with trial ORR >25%, all trials offered combination therapy, either of multiple cytotoxic agents (n = 4) or of cytotoxic and targeted agents (n = 4), further supporting the role for early introduction of combination therapy with novel agents to improve the risk/benefit ratio of phase I trials. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of target‐specific enrollment and combinatorial approaches that can be achieved even in early phase trials, which may contribute to higher response rates.

Limitations of our study include the fact that studies were limited to English‐language publications in peer‐reviewed journals. DLT definitions relied on individual study definitions and were not uniform across all studies. With regard to incomplete or missing data, a minority of studies (n = 12) did not provide response data, only toxicity data. As such these studies were not included in ORR calculations, which could introduce some degree of bias. Lastly, our analyses of DLT and ORR for this systematic review included pooled rates of DLT and ORR. There was sufficient historical precedent in the pediatric oncology literature for pursuing this analysis 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, but we recognize the limitations of interpreting these pooled calculations. We also sought out additional analyses that did not rely on this approach to pooled calculations to further understand the significance of the data from the included trials. With regard to the Wilcoxon rank sum test, it assumes that rate of DLT and ORR estimates reported in a given trial have no error. We acknowledge that there is a degree of variability in these estimates considering the varying numbers of subjects included per study as well as the number of subjects per trial with toxicity and response data reported.

One notable element of our review included the observation of significant heterogeneity in reporting practices across different phase I studies. Notably, toxic death and other death on study were not systematically reported; thus toxic death rate across all studies could not clearly be determined. These metrics represent a crucial aspect of describing the toxicity profile of a novel agent. A greater degree of standardization in reporting practices for publication of early phase study results should be encouraged within the pediatric oncology community. This would facilitate both more transparent communication of results and a greater understanding of the implications for practice stemming from each study's results.

Finally, we recognize that the definitions of cytotoxic and targeted trials differ from the approaches that others comparing cytotoxic and targeted therapies have taken 12, 13. With consideration given to the nature of the targeted therapy and the dose escalation details, these definitions for cytotoxic and targeted trials represent a rational approach to characterizing combination trials, which were important to include to comprehensively evaluate the phase I treatment landscape.

Conclusion

Historically, there has been significant debate surrounding phase I cancer research, particularly in the inherently vulnerable pediatric population, with a question of any direct benefit for the individual patient 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27. These data provide further information to improve discussions about the risk/benefit ratio of phase I trials in pediatric oncology in the current treatment landscape. This systematic review supports the relative safety of phase I trials and also demonstrates some promising response data in a subset of phase I trials, particularly trials with target‐specific enrollment and combinatorial treatment strategies. With a more nuanced understanding of the current landscape of phase I trials, there may be a rationale to increase earlier access to select early phase clinical trials for the relapsed/refractory pediatric oncology patient population.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Julia W. Cohen, Srivandana Akshintala, Brigitte C. Widemann, Seth M. Steinberg, Nirali N. Shah

Provision of study material or patients: Julia W. Cohen, Eli Kane, Helen Gnanapragasam, Nirali N. Shah

Collection and/or assembly of data: Julia W. Cohen, Eli Kane, Helen Gnanapragasam, Nirali N. Shah

Data analysis and interpretation: Julia W. Cohen, Srivandana Akshintala, Brigitte C. Widemann, Seth M. Steinberg, Nirali N. Shah

Manuscript writing: Julia W. Cohen, Srivandana Akshintala, Brigitte C. Widemann, Seth M. Steinberg, Nirali N. Shah

Final approval of manuscript: Julia W. Cohen, Srivandana Akshintala, Eli Kane, Helen Gnanapragasam, Brigitte C. Widemann, Seth M. Steinberg, Nirali N. Shah

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplemental Tables

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute Intramural Research Program.

Editor's Note: See the related commentary by Peter C. Adamson on page 468 of this issue.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Hirsch S, Marshall LV, Carceller Lechon F et al. Targeted approaches to childhood cancer: Progress in drug discovery and development. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2015;10:483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC et al. Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 2014;120:2497–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adamson PC. Improving the outcome for children with cancer: Development of targeted new agents. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:212–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee DP, Skolnik JM, Adamson PC. Pediatric phase I trials in oncology: An analysis of study conduct efficiency. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:8431–8441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vassal G, Zwaan CM, Ashley D et al. New drugs for children and adolescents with cancer: The need for novel development pathways. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e117–e124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Allen CE, Laetsch TW, Mody R et al. Target and agent prioritization for the Children's Oncology Group‐National Cancer Institute Pediatric MATCH Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109:djw274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forrest SJ, Geoerger B, Janeway KA. Precision medicine in pediatric oncology. Curr Opin Pediatr 2018;30:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seibel NL, Janeway K, Allen CE et al. Pediatric oncology enters an era of precision medicine. Curr Probl Cancer 2017;41:194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim A, Fox E, Warren K et al. Characteristics and outcome of pediatric patients enrolled in phase I oncology trials. The Oncologist 2008;13:679–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morgenstern DA, Hargrave D, Marshall LV et al. Toxicity and outcome of children and adolescents participating in phase I/II trials of novel anticancer drugs: The Royal Marsden experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bautista F, Di Giannatale A, Dias‐Gastellier N et al. Patients in pediatric phase I and early phase II clinical oncology trials at Gustave Roussy: A 13‐year center experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2015;37:e102–e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dorris K, Liu C, Li D et al. A comparison of safety and efficacy of cytotoxic versus molecularly targeted drugs in pediatric phase I solid tumor oncology trials. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:e26258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Waligora M, Bala MM, Koperny M et al. Risk and surrogate benefit for pediatric phase I trials in oncology: A systematic review with meta‐analysis. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fox E, Widemann BC, Chuk MK et al. Vandetanib in children and adolescents with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B associated medullary thyroid carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:4239–4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. von Stackelberg A, Locatelli F, Zugmaier G et al. Phase I/phase II study of blinatumomab in pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:4381–4389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mano H. The EML4‐ALK oncogene: Targeting an essential growth driver in human cancer. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2015;91:193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Widemann BC, Kim A, Fox E et al. A phase I trial and pharmacokinetic study of sorafenib in children with refractory solid tumors or leukemias: A Children's Oncology Group Phase I Consortium report. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:6011–6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lin JK, Lerman BJ, Barnes JI et al. Cost effectiveness of chimeric antigen receptor T‐cell therapy in relapsed or refractory pediatric B‐cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:3192–3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whittington MD, McQueen RB, Ollendorf DA et al. Long‐term survival and value of chimeric antigen receptor T‐cell therapy for pediatric patients with relapsed or refractory leukemia. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172:1161–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cousino MK, Zyzanski SJ, Yamokoski AD et al. Communicating and understanding the purpose of pediatric phase I cancer trials. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4367–4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hazen RA, Zyzanski S, Baker JN et al. Communication about the risks and benefits of phase I pediatric oncology trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2015;41:139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berg SL. Ethical challenges in cancer research in children. The Oncologist 2007;12:1336–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ekert H. Can phase I cancer research studies in children be justified on ethical grounds? J Med Ethics 2013;39:407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Glannon W. Phase I oncology trials: Why the therapeutic misconception will not go away. J Med Ethics 2006;32:252–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haylett WJ. Ethical considerations in pediatric oncology phase I clinical trials according to the Belmont Report. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2009;26:107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Joffe S, Miller FG. Rethinking risk‐benefit assessment for phase I cancer trials. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2987–2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miller VA, Cousino M, Leek AC et al. Hope and persuasion by physicians during informed consent. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3229–3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mosse YP, Lim MS, Voss SD et al. Safety and activity of crizotinib for paediatric patients with refractory solid tumours or anaplastic large‐cell lymphoma: A Children's Oncology Group phase 1 consortium study. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:472–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DuBois SG, Allen S, Bent M et al. Phase I/II study of (131)I‐MIBG with vincristine and 5 days of irinotecan for advanced neuroblastoma. Br J Cancer 2015;112:644–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ladenstein R, Weixler S, Baykan B et al. Ch14.18 antibody produced in CHO cells in relapsed or refractory stage 4 neuroblastoma patients: A SIOPEN phase 1 study. MAbs 2013;5:801–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wayne AS, Shah NN, Bhojwani D et al. Phase 1 study of the anti‐CD22 immunotoxin moxetumomab pasudotox for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2017;130:1620–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raetz EA, Morrison D, Romanos‐Sirakis E et al. A phase I study of EZN‐3042, a novel survivin messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) antagonist, administered in combination with chemotherapy in children with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): A report from the Therapeutic Advances in Childhood Leukemia and Lymphoma (TACL) consortium. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:458–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zwaan CM, Rizzari C, Mechinaud F et al. Dasatinib in children and adolescents with relapsed or refractory leukemia: Results of the CA180‐018 phase I dose‐escalation study of the Innovative Therapies for Children with Cancer Consortium. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2460–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fry TJ, Shah NN, Orentas RJ et al. CD22‐targeted CAR T cells induce remission in B‐ALL that is naive or resistant to CD19‐targeted CAR immunotherapy. Nat Med 2018;24:20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler‐Stevenson M et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: A phase 1 dose‐escalation trial. Lancet 2015;385:517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gardner RA, Finney O, Annesley C et al. Intent‐to‐treat leukemia remission by CD19 CAR T cells of defined formulation and dose in children and young adults. Blood 2017;129:3322–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tran HC, Marachelian A, Venkatramani R et al. Oxaliplatin and doxorubicin for relapsed or refractory high‐risk neuroblastoma. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2015;32:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Navid F, Baker SD, McCarville MB et al. Phase I and clinical pharmacology study of bevacizumab, sorafenib, and low‐dose cyclophosphamide in children and young adults with refractory/recurrent solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mascarenhas L, Malogolowkin M, Armenian SH et al. A phase I study of oxaliplatin and doxorubicin in pediatric patients with relapsed or refractory extracranial non‐hematopoietic solid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1103–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abd Elmoneim A, Gore L, Ricklis RM et al. Phase I dose‐escalation trial of clofarabine followed by escalating doses of fractionated cyclophosphamide in children with relapsed or refractory acute leukemias. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;59:1252–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Venkatramani R, Malogolowkin M, Davidson TB et al. A phase I study of vincristine, irinotecan, temozolomide and bevacizumab (vitb) in pediatric patients with relapsed solid tumors. PLoS One 2013;8:e68416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cooper TM, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB et al. AAML0523: A report from the Children's Oncology Group on the efficacy of clofarabine in combination with cytarabine in pediatric patients with recurrent acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2014;120:2482–2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rheingold SR, Tasian SK, Whitlock JA et al. A phase 1 trial of temsirolimus and intensive re‐induction chemotherapy for 2nd or greater relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: A Children's Oncology Group study (ADVL1114). Br J Haematol 2017;177:467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alexander TB, Lacayo NJ, Choi JK et al. Phase I study of selinexor, a selective inhibitor of nuclear export, in combination with fludarabine and cytarabine, in pediatric relapsed or refractory acute leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:4094–4101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplemental Tables