Abstract

Vitamin D plays a key role in the maintenance of calcium/phosphate homeostasis and elicits biological effects that are relevant to immune function and metabolism. It is predominantly formed through UV exposure in the skin by conversion of 7-dehydrocholsterol (vitamin D3). The clinical biomarker, 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-(OH)-D), is enzymatically generated in the liver with the active hormone 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D then formed under classical endocrine control in the kidney. Vitamin D metabolites are measured in biomatrices by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). In LC–MS/MS, chemical derivatization (CD) approaches have been employed to achieve the desired limit of quantitation. Recently, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) has also been reported as an alternative method. However, these quantitative approaches do not offer any spatial information. Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) has been proven to be a powerful tool to image the spatial distribution of molecules from the surface of biological tissue sections. On-tissue chemical derivatization (OTCD) enables MSI to image molecules with poor ionization efficiently. In this technical report, several derivatization reagents and OTCD methods were evaluated using different MSI ionization techniques. Here, a method for detection and spatial distribution of vitamin D metabolites in murine kidney tissue sections using an OTCD–MALDI–MSI platform is presented. Moreover, the suitability of using the Bruker ImagePrep for OTCD-based platforms has been demonstrated. Importantly, this method opens the door for expanding the range of other poor ionizable molecules that can be studied by OTCD–MSI by adapting existing CD methods.

Introduction

Vitamin D has become a priority area of research worldwide. It is a vital component for a number of biological processes such as calcium homeostasis1 and immune function.2 The hormone is studied not only from the aspect of vitamin D deficiency against diseases such as rickets or osteoporosis3,4 but also as a potential treatment of diseases including cancer and mental disorders.5−8 Vitamin D is mainly formed through UV exposure to the skin, through conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to the metabolite vitamin D3 but can also be supplied via vitamin-D-sourced foods as vitamin D2.9−11 The precursor is metabolized in the liver via enzymatic hydroxylation to produce 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-(OH)-D), a clinical biomarker. Further hydroxylation is then carried out in the kidney, producing the active hormone 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25-(OH)2-D), known to be the active ligand of the vitamin D receptor protein and elicits transcriptional effects.12,13 Vitamin D metabolites are primarily measured in biomatrices by immunoassays or liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS).14 Steroidal class compounds are known to have poor ionization efficiency in mass spectrometry (MS) because of a lack of ionizable moieties. To overcome this issue, chemical derivatization (CD) approaches have been used in LC–MS/MS-based platforms using both electrospray ionization (ESI) and atmospheric pressure chemical ionization.15,16 CD is intended to increase the ionization efficiency by tackling ion suppression effects and potential isobaric interferences. Recently, it has been shown that vitamin D metabolites, with the aid of CD, can be detected and quantified by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI).17 These methods are primarily being used to assess levels of vitamin D metabolites in clinical settings. MS is currently being used to measure vitamin D metabolites in serum/plasma and tissue homogenate samples. These quantitative approaches, however, do not offer any spatial information. Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) enables the ability to gain spatial information of various molecules with spectra being mapped to individual pixels. Molecules can be localized and quantified to a host of different organ/tissue types. On-tissue chemical derivatization (OTCD) is enabling MSI to push the boundary of poor ionizable molecules to be imaged within tissues by increasing signal intensity, shifting m/z values, and overcoming poor ionization performance. Previous studies have shown the use of several derivatization reagents in MSI applications. Some examples are Girard-T reagent targeting steroids18,19 and triamcinolone acetonide,20 pyrylium salts for primary amine moiety molecules,21 and 1,1′-thiocarbonyldiimidazole for 3-methoxysalicylamine.22 Other OTCD approaches have also been successfully trialed, such as a high-voltage electrospray deposition using 2-picolylamine for endogenous fatty acids in rat brain tissue.23

In this article, several derivatization reagents, deposition techniques, and reaction conditions were evaluated using different ionization techniques including MALDI and desorption electrospray ionization (DESI) to achieve best ion production yields in MSI analysis of vitamin D metabolites in murine tissue sections. For the first time, a method for detection and spatial distribution of vitamin D metabolites using an OTCD–MALDI–MS platform is presented. Specifically, endogenous 1,25-(OH)2-D3 and 25-(OH)-D3 were detected within a mouse kidney using Amplifex as the derivatization reagent and results were confirmed by LC–MS/MS. The suitability of Bruker’s ImagePrep is also demonstrated for an automated and robust method for OTCD–MSI applications.

Results and Discussion

Reagent Screening and Ionization Assessment (Off-Tissue)

This novel application of OTCD coupled with MSI permits detection of endogenous vitamin D metabolites within tissues by generating permanently charged derivatives which yielded intense signals upon MALDI–Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FTICR)–MSI analysis. The spatial distribution of both 25-(OH)-D3 and 1,25-(OH)2-D3 in mouse kidney was assessed. This technique has the potential to be applied to other vitamin D metabolites to investigate vitamin D intracrinology in multiple biological tissues.

In this article, several LC–MS-based derivatization reagents were evaluated using the reaction conditions to investigate the performance in different MSI ionization modes, specifically MALDI and DESI. These reagents (PTAD, DMEQ-TAD, and Amplifex (Figure S1) were screened off, and on-tissue with instrument parameters optimized using a stable isotope of vitamin D (d6-25-hydroxyvitamin-D3 (d6-25-(OH)-D3)) as an internal standard (ITSD). During off-tissue ionization evaluation, the derivatized PTAD metabolite displayed no fingerprint signal across any of the investigated ionization methods, indicating that PTAD is not suitable for MALDI or DESI analysis. The Amplifex ISTD derivative was detected using both MALDI–MS at m/z 738.5437; 0.27 ppm mass accuracy; 1.8 × 108 signal intensity; and signal/noise (S/N) of 3.1 × 108 (Figure S2b) and DESI–MS at m/z 738.5447; 1.62 ppm mass accuracy; 1.1 × 107 signal intensity; and S/N of 1.7 × 106 (Figure S2c). DMEQ-TAD derivative was also detected using MALDI–MS at m/z 752.4863; 0.12 ppm mass accuracy; 7.2 × 107 signal intensity; and S/N of 2.2 × 105 (Figure S3b) and DESI–MS at m/z 752.4843; 2.78 ppm mass accuracy; 2.5 × 105 signal intensity; and S/N of 1342 (Figure S3c). As expected, Amplifex outperformed DMEQ-TAD in terms of ion signal production for vitamin D metabolite derivatives in positive ion mode, primarily because of its positively charged quaternary amine moiety.

On-Tissue Spotting Assessment, Amplifex Reaction Conditions, and OTCD Sample Preparation Optimization

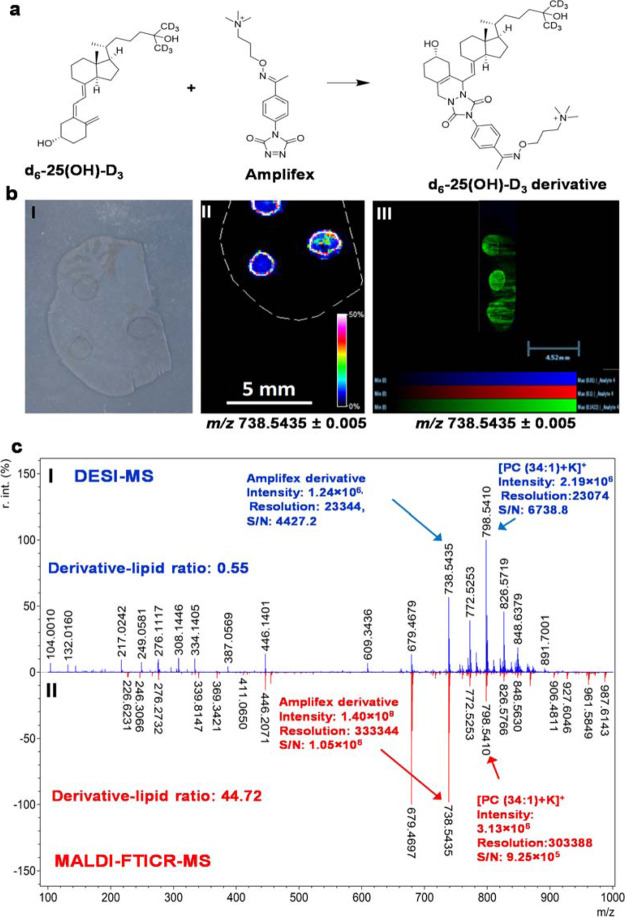

Based on the off-tissue screening results, Amplifex and DMEQ-TAD were selected as suitable reagents for an on-tissue ion suppression assessment. On-tissue ionization suppression was conducted as described in Supporting Information Section 1.2 using a control (blank) tissue section (Figure 1). Amplifex derivative was detected on tissue in MALDI–MSI [Figure 1c(II)] at m/z 738.5435; 0.01 ppm mass accuracy; 1.4 × 108 signal intensity; and S/N 1.05 × 106 (Figure 1c). Using DESI–MSI (Figure 1cI), the Amplifex derivative was detected at m/z 738.5435; 0.01 ppm mass accuracy, with a signal intensity of 1.24 × 106, and S/N of 4427.

Figure 1.

On-tissue spotting experiments by MALDI and DESI MSI platforms using Amplifex as a derivatization reagent. (a) Vitamin D–Amplifex derivatization reaction scheme and (b) on-tissue spotting experiments. (I) Optical image of control tissue section (II) MALDI–MSI molecular distribution map of spotted d6-25-(OH)-D3 Amplifex derivative at m/z 738.5435 ± 0.005. (III) DESI–MSI molecular distribution map of spotted ISTD vitamin D standard Amplifex derivative at m/z 738.5435 ± 0.005; (c) representative zoomed-out single-pixel mass spectrum of d6-25-(OH)-D3-Amplifex derivative spotted region using (I) DESI-qTOF-MS. (II) MALDI–FTICR–MS both with a mass accuracy of 1.08 ppm against theoretical monoisotopic mass. Data were normalized to TIC. Spatial resolution was set at 100 μm, with scale bars shown. Signal intensity is depicted by color on the scale shown. Spectrum was postcalibrated to CHCA cluster matrix ion at +ve m/z 417.0483.

The DMEQ-TAD derivative was also detected by MALDI–MSI at m/z 752.4848; 2.11 ppm mass accuracy with a signal intensity of 6.3 × 107; and S/N of 1.2 × 104 (Figure S4) and DESI–MSI at m/z 752.4730; 1.7 ppm mass accuracy, signal intensity around 0.8 × 104, and S/N of 340 (Figure S5). On-tissue Amplifex and DMEQ-TAD VitD derivatives showed good ionization in both the MALDI and DESI–MSI platforms with best results achieved using the Amplifex-MALDI–MSI platform. Analyte diffusion was observed during DESI–MSI, which may be related to solvent spraying and charging effects caused by the chemical nature of the derivatization reagent. Based on the results obtained from on-tissue screening experiments, MALDI–MSI using Amplifex as a derivatization reagent was selected as the imaging platform for final reaction and sample preparation optimization. Off- and on-tissue reaction parameters were evaluated with an optimal CD condition achieved at 1 h at room temperature (RT) for both off-tissue (Figure S6a) and on-tissue derivatization (Figure S6b). Regarding reagent deposition and OTCD, two methods were evaluated for MSI performance in terms of analyte detection, diffusion, and reproducibility. The Bruker ImagePrep and a commercial artistic airbrush were assessed. The airbrush application method was adapted from previous studies,23 and the Bruker ImagePrep method was adapted and customized for reagent deposition as described in the Materials and Methods section “OTCD–MSI Analysis of Endogenous Vitamin D Metabolite Derivatives in Mouse Kidney Tissue Sections”. Figure S7 clearly shows that the automated ImagePrep method outperformed the manual airbrush. Ion signal intensity was increased in the ImagePrep MS images, as better S/N ratios (ImagePrep 2800 and airbrush 1200) were obtained than with the airbrush method (Supporting Information Figure S7d). Moreover, tissue-to-tissue reproducibility and analyte diffusion were improved by using the Bruker ImagePrep approach (Figure S7d).

When using manual sample preparation methods, analyst-to-analyst variations have a negative impact on reproducibility in MS and particularly with MSI analysis. These parameters in manual OTCD methods are very difficult to control. On the contrary, these potential issues are well controlled in the automated method as both reagent application and CD reaction can be carried out using the same device. In this method, several key parameters can be controlled such as drying, incubation time, and spray frequency. Another advantage of the automated ImagePrep is that both application and derivatization reaction are performed under an inert atmosphere, allowing oxygen-sensitive chemical reactions to be carried out robustly. However, one disadvantage to mention is that in the ImagePrep, temperature cannot be controlled and thus would not be applicable to OTCD reactions that require controlled temperatures.

Distribution of Endogenous Vitamin D Metabolites in Mouse Kidney Tissue by OTCD–MALDI–FTICR–MSI

For the first time, vitamin D metabolites were successfully detected, and their spatial distribution was assessed in murine kidney tissue sections using the optimized automated OTCD–MALDI–MSI platform. Hydroxylation of the precursor 25-hydroxyvitamin D occurs in the kidney to produce the active metabolite, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, by the enzyme CYP27B1.28,29 Therefore, this gives a good rationale for the selection of the kidney as a target/suitable metabolic tissue to perform this MSI feasibility study.

As shown in Figure 2, two endogenous vitamin D metabolites were detected as Amplifex derivatives at m/z 732.5053, corresponding to the 25-(OH)-D3 (Figure 2c) and m/z 748.4992 for 1,25-(OH)2-D3 (Figure 2d), with a mass accuracy of 0.68 ppm (Figure 2e) and 1.20 ppm (Figure 2f), against their theoretical monoisotopic protonated masses, respectively. To confirm the identification of the active metabolite 1,25-(OH)2-D3, collision-induced dissociation (CID) experiments were performed on high signal intensity region of interests (ROI) within the tissue section. The CID on the M+ ion at m/z 748.49 showed a main fragment at m/z 689.4493 with a loss of 59 Da corresponding to the trimethylamine moiety (Figure S8). These results are in agreement with previous literature reports.17 LC/MS was also performed to confirm the presence of the active metabolite (1,25-(OH)2-D3) on the tissue homogenate, giving a concentration of 132.6 pg/g (Figure 2g).

Figure 2.

Molecular distribution of endogenous vitamin D metabolites detected as Amplifex derivatives in a mouse kidney section using the optimized and automated OTCD–MALDI–MSI platform. (a) Illustration of a kidney section; (b) optical image of mouse kidney; (c) molecular distribution map of 25-OH-D3-Amplifex derivative (m/z 732.5053 ± 0.005); (d) molecular distribution map of 1,25-(OH)2-D3-Amplifex derivative (m/z 748.4992 ± 0.005); and (e) representative single-pixel MALDI–FTICR–MS mass spectrum for 25-(OH)-D3-Amplifex derivative with a mass accuracy of 0.68 ppm against theoretical monoisotopic mass (shown inset). (f) Representative single-pixel MALDI–FTICR–MS mass spectrum for 1,25-(OH)2-D3-Amplifex derivative with a mass accuracy of 1.20 ppm against theoretical monoisotopic mass (shown inset). (g) Active metabolite (1-25-(OH)2-D3) confirmation by LC–MS/MS. Data were normalized to TIC. Spatial resolution was analyzed at 100 μm, with scale bars shown. Signal intensity is depicted by color on the scale shown. Spectrum was postcalibrated to CHCA cluster matrix ion at +ve m/z 417.0483.

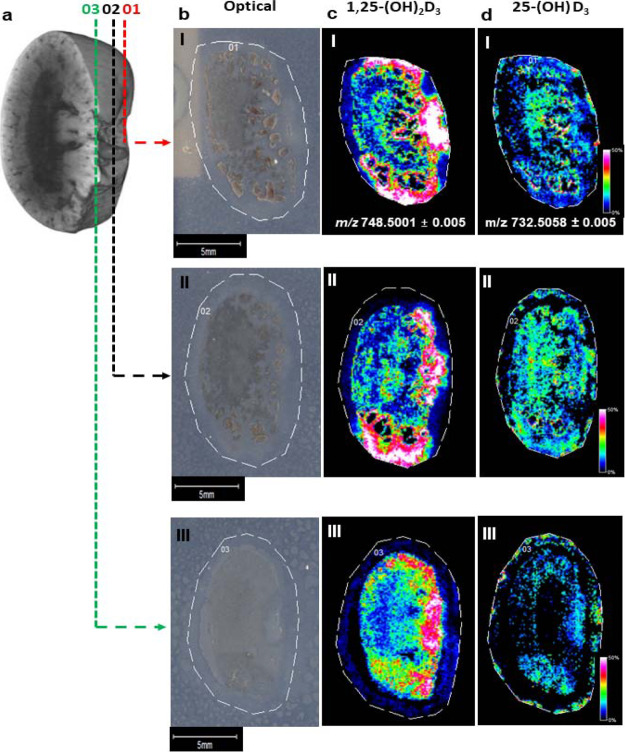

To study the molecular distribution pattern of vitamin D metabolites across the mouse kidney, the molecular mapping of three sections were assessed. As shown in Figure 3, 1,25-(OH)2-D3 was mainly detected across the cortex gathering near the renal vein and 25-(OH)-D3 was mainly distributed across the medulla and inner cortex. However, as shown in Figure 3, the 25-(OH)-D3 metabolite formation was depth-dependent, as its normalized signal intensity varies across a series of adjacent kidney sections (n = 3), with the detected signal decreasing throughout the tissue. This suggests that 3D molecular mapping analysis may provide valuable information regarding metabolism across the entire tissue. Knowing the tissue distribution of vitamin D metabolites may be key in the understanding of the synthesis and function of the active metabolite 1,25-(OH)2-D3 as it has a key role in the calcium absorption and it is a potent ligand in gene transcription pathways across various tissues.9,30 Previous studies have detected the CYP27B1 enzyme by immunohistochemistry in the proximal tubules of kidney nephrons, located in the cortex region of the tissue.31 In vivo pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics experiments using stable isotope tracers in combination with MSI might be able to expand the knowledge of vitamin D metabolism by understanding the biology of vitamin D and the CYP27B1 enzyme activity at tissue-specific levels.

Figure 3.

Molecular distribution assessment of endogenous vitamin D metabolites detected as Amplifex derivatives on three adjacent sections of mouse kidney using the optimized and automated OTCD–MALDI–MSI platform. (a) Illustration of a kidney section. [b(I,II)] Optical images of adjacent mouse kidney. [c(I,III)] Molecular distribution map of 1-25-(OH)2-D3-Amplifex derivative (m/z 748.5001 ± 0.005). [d(I–III)] Molecular distribution map of 25-(OH)-D3-Amplifex derivative (m/z 732.5058 ± 0.005). Data were normalized to TIC. Spatial resolution was analyzed at 100 μm, with scale bars shown. Signal intensity is depicted by the color on the scale shown.

Quantitative MSI Feasibility

A VitD metabolite-stable isotope (deuterium labeled, d2) was used in this study as an ISTD for method development purposes, and it is currently commercially available. Therefore, quantitative MSI (qMSI) of VitD metabolites would be achievable by applying well-known models such as mimetic tissue, tissue extinction coefficient, and standard on-tissue spotting. Because VitD metabolites are endogenously present in key metabolic tissues such as kidney, a potential qMSI approach is to use a calibration based on a range of known deuterated labeled VitD solutions (used as standards) with a fixed amount of a 13C labeled (as an ISTD) spiked onto a series of tissue homogenates. As the ionization is mainly driven by the derivatization reagent quaternary amine moiety, it would be valid to assume that the response factors of all Amplifex-VitD derivatives will be close to 1. In this case, the more conservative and accurate qMSI approach would be to use the mimetic tissue method as it would minimize any topology-related effects, usually observed during manual or automated tissue-spotting approaches. Analysis could be performed using VitD (d2/13C) ratios containing pixels employing three replicates and two MSI platforms such as MALDI-TOF-qMSI and MALDI–FTICR-qMSI. The average intensity of each layer of the mimetic tissue model can be correlated with the known spiked concentration to generate a calibration curve. This curve can then be used to quantify ROIs on the target tissue. These results will be compared to the conventional gold standard quantitative platform using HPLC–MS/MS. For calculations, linear or nonlinear regression analysis can be used depending on factors such as matrix-to-analyte ratio, nonuniform tissue-ion suppression, interferences from matrix background signals, and different ion detection/counting technologies.

Conclusions

MSI with OTCD is a powerful new tool to study the spatial distribution of vitamin D metabolites within tissues. This is the first technique capable of detecting and potentially quantifying low physiological endogenous tissue levels of vitamin D metabolites. qMSI using stable isotope standards would be achieved by applying well-established qMSI approaches. We have demonstrated its utility for measuring endogenous concentrations within murine kidney, a key metabolic organ for vitamin D metabolism. This offers the opportunity for many novel insights into tissue-specific vitamin D biology. Moreover, the suitability of using the automated ImagePrep for reagent deposition and as a reaction chamber for OTCD-based platforms shows a promising outcome and offers the ideal conditions to achieve reproducible MSI images. Importantly, the use of OTCD–MSI facilitates/enables the analysis of previously inaccessible biologically relevant molecules through adaptation of existing CD methods.

Materials and Methods

Sources of Chemicals

ISTD 26,26,26,27,27,27-D6-25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (d6-25-(OH)-D3), Amplifex Diene reagent, 4-phenyl-1,2,4-trazoline-3,5-dione (PTAD), and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (UK). 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-(OH)2-D3) was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (UK). 4-(2-(6,7-Dimethoxy-4-methyl-3-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinoxalinyl)ethyl)-1,2,4-triazoline-3,5-dione reagent (DMEQ-TAD) was purchased from Abcam (UK). Solvents were of HPLC grade from Fisher Scientific (UK).

Animal and Tissue Collection

Experiments were conducted in accordance with the Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Male nude CD-1 mice (aged 6–8 weeks, weighing approximately 27–34 g) were housed at a RT of 20–24 °C, with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Animals were housed in individually ventilated cages with standard certified diet food and water provided ad libitum. Animals were sacrificed by schedule I. Organs were then extracted and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until MSI analysis.

Tissue Sectioning and Mounting

Tissues were cryosectioned on a sagittal plane for brain tissue (control tissue for spotting experiments) and top-down (horizontal) section for mouse kidney (12 μm). Sectioning was performed using a Leica cryostat model CM 1850 UV (Leica Biosystems, Nußloch, Germany). Sections were thaw-mounted onto conductive indium tin oxide-coated slides (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, GmbH), dried in a vacuum desiccator (RT, 30 min), and then stored at −80 °C.

Off- and On-Tissue Method Development and Amplifex Reaction Condition Optimization

See the Supporting Information.

OTCD–MSI Analysis of Endogenous Vitamin D Metabolite Derivatives in Mouse Kidney Tissue Sections

At −80 °C, tissue sections were dried in a vacuum desiccator (20 min). Amplifex reagent (5 mL, 0.1 mg/mL in 50:50 v/v acetonitrile/water) was applied to the tissue sections by ImagePrep (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, GmbH). The ImagePrep parameters were set as follows: “matrix thickness”: 40 cycles, spray power: 25%, and a fixed spray time of 2.2 s. Incubation was set to 30 s with a fixed dry time of 60 s, leading to a final OTCD time of 60 min/slide with a reagent density of 0.02 mg/cm2. An artistic airbrush was also evaluated as an OTCD method adapted from Cobice et al.24 Briefly, a reaction solution of Amplifex (2 mL, 0.25 mg/mL in 50:50 v/v acetonitrile/water) was sprayed positioned 20 cm away from the target with a N2 pressure of 1.2 bar. The reagent density was 0.02 mg/cm2. Then, the slide was placed in a closed reaction container, containing a 1:1 v/v solution of acetonitrile/water and a moist Kimwipe under the lid and placed in an oven at 37 °C for 1 h.

Matrix Application

CHCA (6 mL, 5 mg/mL in 70:30 v/v acetonitrile/water + 0.1% v/v TFA) was applied in four passes using a 3D printer, as described in Tucker et al.25 A flow rate of 0.1 mL/min with a gas pressure of 2 bar, a bed temperature of 30 °C, a z-height of 30 mm, and a velocity of 1100 mm/min were achieved, averaging a run time of 24 min per slide. A uniform coating of matrix was achieved with 0.12 mg/cm2.

Instrumentation

Spotting assessment and MSI were performed using a 9.4 T SolariX MALDI–FTICR–MS (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) employing a Smartbeam 2 kHz laser, with instrument control using FTMS control v2.2.0 (build 150) FlexImaging version 5.1 (build 80) and data analysis using mMass software v5.5.0 for mass spectral postprocessing and recalibration.26,27 DESI–MSI experiments were performed on a commercial DESI 2D source (OmniSpray 2D Source, Prosolia Inc, Indianapolis, IN, USA) mounted on a Waters Xevo G2-XS quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, Manchester, UK). CD reaction optimization was performed on an Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex 4800 MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Foster City, California, USA) equipped with a neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser operating at 355 nm (200 Hz repetition rate). The mass range was acquired from 400 to 800 Da, focusing on the appropriate base peak ion in positive reflector mode. The instrument was calibrated using CAL MIX 5 as per manufacturer guidelines.

Confirmatory LC–MS/MS analysis was performed using a triple-quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometer (QTRAP 6500, AB Sciex, Cheshire, UK) coupled with an ACQUITY ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography system (UHPLC; Waters, Manchester, UK).

MALDI–FTICR–MSI

MALDI–MSI was performed using a 9.4 T SolariX. The instrument was calibrated prior to analysis using red phosphorus clusters during method development and optimization operated in magnitude mode at 516 K size at a mass range of m/z 600–900 using one average scan in positive ion mode. Four hundred shots were accumulated per pixel/spot at 2000 Hz frequency employing a minimum laser focus. Kidney section images were acquired using the optimized imaging method operated in constant accumulation of selected ion mode at m/z 732 (Q-isolation) with an isolation window of 100 Da in positive ion mode. The mass resolution at m/z 700 was 40,000. The same laser parameters were used as per the development method. Images were acquired at a spatial resolution of 100 × 100 μm, generated using the FlexImaging version 5.1 software (Bruker Daltonik GmbH), and then normalized with the total ion current (TIC). A 95% data reduced profile spectrum and spectrum peak list were saved for further analysis. Optical images were taken using a flatbed scanner (Cannon LiDE-20, Cannon, UK). CID experiment on 1,25-(OH)2-D3 was performed at m/z 748.49 with an isolation window of 20 Da, isolation time of 2 s, and 800 laser shots using 35 eV collision energy.

DESI–MSI

See the Supporting Information.

Confirmatory LC–MS/MS Analysis

See the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from the Department for Employment and Learning (DEL) Northern Ireland and the Research Challenge Fund from Ulster University.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- MALDI

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization

- DESI

desorption electrospray ionization

- FTICR-MS

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry

- OTCD

on-tissue chemical derivatization

- CD

chemical derivatization

- 25-(OH)-D3

25-hydroxyvitamin D3

- 1,25-(OH)2-D3

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

- MSI

mass spectrometry imaging

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c01697.

Method development including CD reaction conditions, ion suppression assessment, sample preparation optimization, VitD metabolites, off-tissue spotting experiments, on-tissue ionization assessment, VitD–Amplifex reaction conditions, optimization of OTCD, CID experiments, LC gradient, multiple reaction monitoring conditions, off-tissue reagent screening results, and on-tissue ionization suppression assessment (PDF)

Author Present Address

▽ K.W.S.: National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida 32310-4005, United States

Author Contributions

D.F.C. and R.M.A.H. conceived and coordinated the experiments. K.W.S., B.F., and D.F.C. designed the experiments. K.W.S., B.F., F.L.C., and C.L.M. carried out MS experiments. K.W.S., B.F., P.D.T., and D.F.C conducted data processing and analysis. K.W.S., B.F., and D.F.C. wrote the manuscript, which was edited by all co-authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Fleet J. C. The role of vitamin D in the endocrinology controlling calcium homeostasis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 453, 36–45. 10.1016/j.mce.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair R.; Maseeh A. Vitamin D: The “sunshine” vitamin. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2012, 3, 118–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick M. F.; Binkley N. C.; Bischoff-Ferrari H. A.; Gordon C. M.; Hanley D. A.; Heaney R. P.; Murad M. H.; Weaver C. M. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C. L.; Greer F. R. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics 2008, 122, 1142–1152. 10.1542/peds.2008-1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty D.; Dvorkin S. A.; Rodriguez E. P.; Thompson P. D. Vitamin D receptor agonist EB1089 is a potent regulator of prostatic “intracrine” metabolism. Prostate 2014, 74, 273–285. 10.1002/pros.22748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu C. Vitamin D and diabetes: where do we stand?. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 108, 201–209. 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda U.; Mutowo M. P.; Smith B. J.; Wluka A. E.; Renzaho A. M. N. Vitamin D supplementation to reduce depression in adults: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition 2015, 31, 421–429. 10.1016/j.nut.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner P. P.; Sharony L.; Miodownik C. Association between mental disorders, cognitive disturbances and vitamin D serum level: current state. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 23, 89–102. 10.1016/j.clnesp.2017.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle D. D. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 319–329. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R. R.; Phillips K. M.; Horst R. L.; Munro I. C. Vitamin D mushrooms: comparison of the composition of button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) treated postharvest with UVB light or sunlight. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 8724–8732. 10.1021/jf201255b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nölle N.; Argyropoulos D.; Ambacher S.; Müller J.; Biesalski H. K. Vitamin D2 enrichment in mushrooms by natural or artificial UV-light during drying. LWT--Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 85, 400–404. 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.11.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pike J. W.; Christakos S. Biology and mechanisms of action of the vitamin D hormone. Endocrinol. Metabol. Clin 2017, 46, 815–843. 10.1016/j.ecl.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. W.; Thompson P. D.; Rodriguez E. P.; Mackay L.; Cobice D. F. Effects of vitamin D as a regulator of androgen intracrinology in LNCAP prostate cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 519, 579–584. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volmer D. A.; Mendes L. R. B. C.; Stokes C. S. Analysis of vitamin D metabolic markers by mass spectrometry: current techniques, limitations of the “gold standard” method, and anticipated future directions. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2015, 34, 2–23. 10.1002/mas.21408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman C. J.; Wiebe D. A.; Dey S.; Plath J.; Kemnitz J. W.; Ziegler T. E. Development of a sensitive LC/MS/MS method for vitamin D metabolites: 1, 25 Dihydroxyvitamin D2&3 measurement using a novel derivatization agent. J. Chromatogr. B: Biomed. Sci. Appl. 2014, 953–954, 62–67. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeff-Armas L. A.; Kaufmann M.; Lyden E.; Jones G. Serum 24, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 response to native vitamin D2 and D3 Supplementation in patients with chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1041–1045. 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y.; Müller M.; Stokes C. S.; Volmer D. A. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 29, 1456–1462. 10.1007/s13361-018-1956-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobice D. F.; Mackay C. L.; Goodwin R. J. A.; McBride A.; Langridge-Smith P. R.; Webster S. P.; Walker B. R.; Andrew R. Mass spectrometry imaging for dissecting steroid intracrinology within target tissues. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 11576–11584. 10.1021/ac402777k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobice D. F.; Livingstone D. E. W.; McBride A.; MacKay C. L.; Walker B. R.; Webster S. P.; Andrew R. Quantification of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 kinetics and pharmacodynamic effects of inhibitors in brain using mass spectrometry imaging and stable-isotope tracers in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 148, 88–99. 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barré F. P. Y.; Flinders B.; Garcia J. P.; Jansen I.; Huizing L. R. S.; Porta T.; Creemers L. B.; Heeren R. M. A.; Cillero-Pastor B. Derivatization strategies for the detection of triamcinolone acetonide in cartilage by using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 12051–12059. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariatgorji M.; Nilsson A.; Källback P.; Karlsson O.; Zhang X.; Svenningsson P.; Andren P. E. Pyrylium salts as reactive matrices for MALDI-MS imaging of biologically active primary amines. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 26, 934–939. 10.1007/s13361-015-1119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacon A.; Zagol-Ikapitte I.; Amarnath V.; Reyzer M. L.; Oates J. A.; Caprioli R. M.; Boutaud O. On-tissue chemical derivatization of 3-methoxysalicylamine for MALDI-imaging mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 46, 840–846. 10.1002/jms.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q.; Comi T. J.; Li B.; Rubakhin S. S.; Sweedler J. V. On-tissue Derivatization Via Electrospray Deposition for Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Endogenous Fatty Acids in Rat Brain Tissues. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 5988–5995. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobice D. F.; Livingstone D. E. W.; Mackay C. L.; Goodwin R. J. A.; Smith L. B.; Walker B. R.; Andrew R. Spatial Localization and Quantitation of Androgens in Mouse Testis by Mass Spectrometry Imaging. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 10362–10367. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker L. H.; Conde-González A.; Cobice D.; Hamm G. R.; Goodwin R. J. A.; Campbell C. J.; Clarke D. J.; Mackay C. L. MALDI matrix application utilizing a modified 3D printer for accessible high resolution mass spectrometry imaging. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 8742–8749. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohalm M.; Kavan D.; Novák P.; Volný M.; Havlíček V. mMass 3: a cross-platform software environment for precise analysis of mass spectrometric data. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 4648–4651. 10.1021/ac100818g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sládková K.; Houška J.; Havel J. Laser desorption ionization of red phosphorus clusters and their use for mass calibration in time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2009, 23, 3114–3118. 10.1002/rcm.4230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle D. D.; Patzek S.; Wang Y. Physiologic and pathophysiologic roles of extra renal CYP27b1: Case report and review. BoneKEy Rep. 2018, 8, 255–267. 10.1016/j.bonr.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman D.; Krishnan A. V.; Swami S.; Giovannucci E.; Feldman B. J. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2014, 14, 342–357. 10.1038/nrc3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire O.; Pollock C.; Martin P.; Owen A.; Smyth T.; Doherty D.; Campbell M. J.; McClean S.; Thompson P. Regulation of CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 expression and modulation of “intracrine” metabolism of androgens in prostate cells by liganded vitamin D receptor. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 364, 54–64. 10.1016/j.mce.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M. B.; Andersen C. B.; Nielsen J. E.; Bagi P.; Jørgensen A.; Juul A.; Leffers H. Expression of the vitamin D receptor, 25-hydroxylases, 1α-hydroxylase and 24-hydroxylase in the human kidney and renal clear cell cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 121, 376–382. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.