Abstract

Objective:

There is a lack of standardisation in the terminology used to describe gout. The aim of this project was to develop a consensus statement describing the recommended nomenclature for disease states of gout.

Methods:

A content analysis of gout-related articles from rheumatology and general internal medicine journals published over a five year period identified potential disease states and the labels commonly assigned to them. Based on these findings, experts in gout were invited to participate in a Delphi exercise and face-to-face consensus meeting to reach agreement on disease state labels and definitions.

Results:

The content analysis identified 13 unique disease states and a total of 63 unique labels. The Delphi exercise (n=76 respondents) and face-to-face meeting (n=35 attendees) established consensus agreement for eight disease state labels and definitions. The agreed labels were: ‘asymptomatic hyperuricemia’, ‘asymptomatic monosodium urate crystal deposition’, ‘asymptomatic hyperuricemia with monosodium urate crystal deposition’, ‘gout’, ‘tophaceous gout’, ‘erosive gout’, ‘first gout flare’ and ‘recurrent gout flares’. There was consensus agreement that the label ‘gout’ should be restricted to current or prior clinically evident disease caused by monosodium urate crystal deposition.

Conclusion:

Consensus agreement has been established for the labels and definitions of eight gout disease states, including ‘gout’ itself. The Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN) recommends the use of these labels when describing disease states of gout in research and clinical practice.

Keywords: gout, urate, hyperuricemia, monosodium urate crystals, nomenclature, language, terminology

INTRODUCTION

The language used to describe gout is characterised by a lack of consistent terminology and definitions.1,2 In particular, many different terms are used interchangeably to describe different disease states and their constituent features. This lack of agreement and clarity has implications for how disease related concepts are communicated in both clinical and research settings.3–5 Notably, there is no universally accepted definition of ‘gout’ itself.6

The Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN) is an international, multidisciplinary network for collaborative research, committed to advancing all aspects of the crystal deposition-associated disorders. G-CAN has supported a project to establish consensus agreement on the nomenclature of hyperuricaemia and gout, its primary objective being the promotion of accurate, well defined, terms that facilitate understanding of disease related concepts. The intended audience is health care professionals and non-physician scientists in clinical and research settings.

In the first stage of the G-CAN gout nomenclature project, consensus agreement was reached on the labels and definitions of the disease elements of gout. The content analysis of the literature and subsequent G-CAN-endorsed consensus statement have been published, with the results of the latter summarised in Table 1.1,7 Using these results as a framework, the objective of this second stage of the G-CAN gout nomenclature project was to reach agreement on the nomenclature of disease states of gout. For the purpose of this project, a disease state was defined as ‘a clinically meaningful cluster of the presence, or absence, of two or more disease elements’. Here, we describe the process and outcomes of this project addressing the labels and definitions of the disease states of gout.

Table 1.

G-CAN endorsed labels and definitions of the disease elements of gout7

| Consensus label | Consensus definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical elements | 1. Monosodium urate crystals | The pathogenic crystals in gout (chemical formula: C5H4N4NaO3). |

| 2. Urate | The circulating form of the final enzymatic product generated by xanthine oxidase in purine metabolism in humans (chemical formula: C5H3N4O3−). | |

| 3. Hyperuricemia† | Elevated blood urate concentration over the saturation threshold. | |

| Clinical elements | 4. Gout flare | A clinically evident episode of acute inflammation induced by monosodium urate crystals. |

| 5. Intercritical gout | The asymptomatic period after or between gout flares, despite the persistence of monosodium urate crystals. | |

| 6. Chronic gouty arthritis | Persistent joint inflammation induced by monosodium urate crystals. | |

| 6a. G-CAN recommendation | The label ‘chronic gout’ should be avoided. | |

| 7. Tophus | An ordered structure of monosodium urate crystals and the associated host tissue response. | |

| 8. Subcutaneous tophus | A tophus that is detectable by physical examination. | |

| 9. Podagra | A gout flare at the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint. | |

| Imaging elements | 10. Imaging evidence of monosodium urate crystal deposition | Findings that are highly suggestive of monosodium urate crystals on an imaging test. |

| 11. Gouty bone erosion | Evidence of a cortical break in bone suggestive of gout (overhanging edge with sclerotic margin). |

In British English, hyperuricaemia.

METHODS

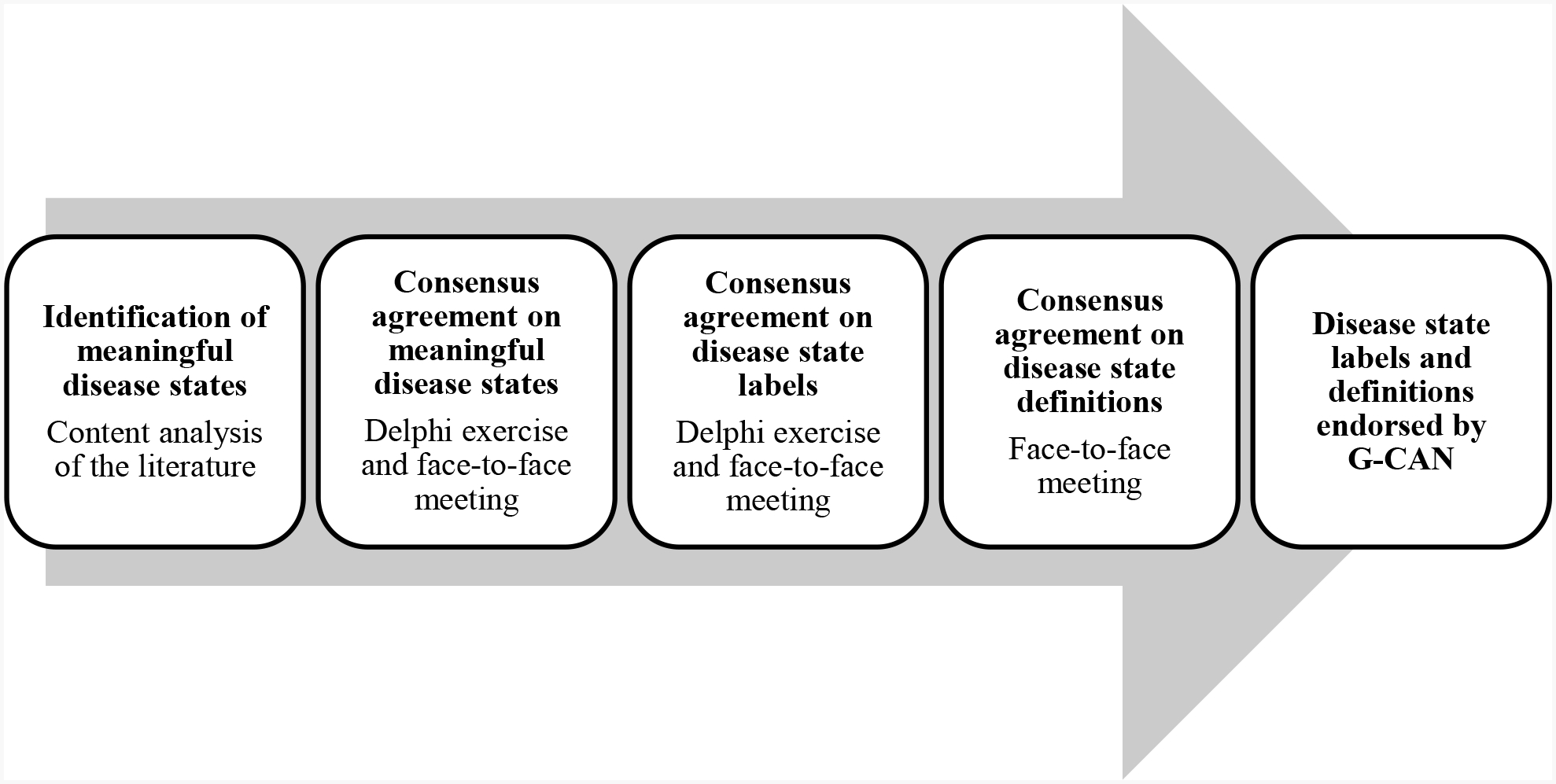

This work consisted of three components: a content analysis of the literature, a Delphi exercise and a face-to-face consensus meeting. The content analysis of the literature was performed to identify the language currently used to represent disease states of gout. The results of this analysis were then used as the basis for two group consensus exercises - a Delphi exercise and a face-to-face meeting - with the overall objective of reaching agreement on a nomenclature for disease states of gout. A schematic representation of these project components is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Outline of the project to develop the Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN) consensus statement regarding the labels and definitions of disease states of gout.

Content analysis of the literature

This component of the project had two aims: first, to establish the range of disease states described in the contemporary gout- and hyperuricemia-related literature; and second, to identify the labels currently used to denote these disease states. Articles were extracted from the ten highest-ranked general rheumatology journals, and the five highest-ranked general internal medicine journals (according to Impact Factor, 2016 Thomson-Reuters Journal Citation Reports) published between 1st January 2013 and 31st January 2018. These journals are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Relevant articles within each journal were identified through MEDLINE using the search terms ‘gout’ or ‘urate’ or ‘hyperuricemia’ without exclusion criteria. This methodology was used to provide a suitably large representation of contemporary literature for the extraction of disease states and their labels, with the intention of reflecting the current language of gout and hyperuricaemia, rather than its progression over time.

For the purpose of this project, a disease state was defined as a ‘clinically meaningful cluster of the presence, or absence, of two or more disease elements’. The G-CAN-endorsed labels and definitions for the disease elements of gout are summarised in Table 1. A cluster was considered ‘meaningful’ if the co-occurrence of these disease elements had the potential to impact either disease prognosis or management. Articles were manually searched for passages of text referring to the collective presence, or absence, of two or more disease elements. Labels for each identified disease state were extracted to determine the range and frequency of unique labels. Disease state labels were taken verbatim from the examined text, except where the labels for component disease elements were modified to comply with existing G-CAN consensus statement for disease elements (as shown in Table 1). Labels were considered ‘unique’ if they used different words or phrases to describe a disease state. For each article, the use of a unique label was recorded only once. All articles were analyzed by a single investigator (DB). To ensure the accuracy of the disease state and label identification, the first 10 articles examined were jointly reviewed by a second investigator (ND) with 98% agreement on identified disease element clusters.

Delphi exercise

The Delphi exercise was conducted as a series of three web-based surveys using Survey Monkey™ software (SurveyMonkey Inc., San Mateo, CA). Physicians and non-physician scientists with expertise in gout were identified through their membership of G-CAN and invited by email to participate in the first round of the survey. Subsequent rounds were only made available to those who had engaged in the previous surveys. In each survey, respondents were presented with disease states identified by the content analysis of the literature, represented by the disease element clusters. Respondents were first asked if each proposed disease state was meaningful for disease prognosis or management. Next, respondents were asked to select and rank their preferred labels for each disease state from a list of options derived from the content analysis of the literature; labels were included if present in at least two of the articles analysed, with the frequency with which they occurred in the literature also shown. In the first round, respondents were also able to nominate their own preferred disease states or labels that had not already been presented; these were included as voting options in the second round of the Delphi if nominated by at least two respondents. Respondents were given the option to comment on disease states or labels that they felt either strongly for or against; a thematic summary of these comments was provided as group feedback in subsequent rounds according to Delphi principles. Disease state label options were refined as the Delphi rounds progressed. Voting on whether a disease state was meaningful, and for its preferred label, ceased once consensus agreement was achieved, defined as at least 80% agreement.

Face-to-face meeting

The face-to-face meeting took place on the 20th of October 2018 in Chicago, IL. All G-CAN members were invited to attend irrespective of their involvement in the Delphi exercise. There were two main objectives for this meeting. The first objective was to address those disease states for which consensus agreement was not met at the conclusion of the Delphi exercises, either for whether they were meaningful, or for the preferred label. The second objective was to agree on a definition for each disease state included in the final consensus statement. Attendees were provided pre-reading that included a summary of the content analysis of the literature, results of the Delphi exercise, and draft definitions of the disease states as a starting point for discussion. The meeting was conducted as a facilitated discussion, moderated by two investigators (DB and ND). Key points raised by attendees were summarised, refined by group discussion, and then brought forward for voting by show of hands. Consensus agreement was defined as at least 80% agreement by those present at the time of voting.

The group was first asked to consider which of the proposed disease states should be included in the nomenclature based on the results of the Delphi exercise. It was agreed that only those disease states that had achieved consensus agreement as being meaningful following the three rounds of the Delphi exercise would be included. Next, disease state labels for which consensus agreement had not been reached during the Delphi exercise were discussed and voted on. Finally, the definitions for each disease state were developed and iteratively modified until consensus agreement was reached.

G-CAN endorsement

[The results of the project and consensus nomenclature statement have been reviewed and endorsed by the G-CAN Board of Directors.]

RESULTS

Content analysis of the literature

A total of 539 articles were extracted using the search criteria. Analysis of these articles identified 13 disease states that were categorised into preclinical states, clinical states, and states describing the disease course of gout (Table 2). In total, there were 63 unique labels identified for these 13 disease states. A detailed description of these results is shown in the Supplementary Material.

Table 2.

Results of the content analysis of 539 gout- and hyperuricemia-related articles: disease element clusters identified as potentially meaningful disease states of gout and characteristics of their labels.

| Disease states represented by disease element clusters | Number of articles labelling disease state (% of total articles) | Number of unique labels identified | Most frequently used labels (% of articles referencing disease state) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical states | Hyperuricemia† without clinical disease elements2 of gout | 79 (14.5%) | 1 | Asymptomatic hyperuricemia† (100%) |

| Imaging evidence of MSU1 crystal deposition without clinical disease elements2 of gout | 32 (5.9%) | 8 | Asymptomatic MSU1 crystal deposition (43.8%) | |

| Hyperuricemia† with imaging evidence of MSU1 crystal deposition and without clinical disease elements2 of gout | 32 (5.9%) | 4 | Asymptomatic hyperuricemia† with MSU1 crystal deposition (90.6%) | |

| Clinical states | Presence of MSU1 crystals with Clinical disease elements2 of gout | 61 (11.3%) | 14 | Symptomatic gout (50.8%) |

| Presence of MSU1 crystals with any of the following: frequent recurrent gout flares, chronic gouty arthritis, subcutaneous tophi or imaging disease elements3 of gout | 72 (13.4%) | 6 | Severe gout (81.9%) | |

| Presence of MSU1 crystals with at least one subcutaneous tophus | 106 (19.7%) | 3 | Tophaceous gout (81.1%) | |

| Chronic gouty arthritis with at least one subcutaneous tophus | 10 (1.9%) | 4 | Chronic tophaceous gouty arthropathy (40.0%) | |

| Presence of MSU1 crystals with any of the following: gout flare, chronic gouty arthritis and without subcutaneous tophi | 10 (1.9%) | 3 | Non-tophaceous gout (80%) | |

| Presence of MSU1 crystals with clinical disease elements2 of gout and with at least one gouty bone erosion | 6 (1.1%) | 1 | Erosive gout (100%) | |

| Disease course states | The first episode of gout flare without preceding intercritical gout | 73 (13.5%) | 5 | Incident gout (75.3%) |

| More than one episode of gout flare with intercritical gout | 79 (14.7%) | 8 | Recurrent gout flares (94.9%) | |

| Presence of MSU1 crystals with clinical disease elements2 of gout and early in the course of disease natural history | 19 (3.5%) | 4 | Early gout (68.4%) | |

| Presence of MSU1 crystals with clinical disease elements2 of gout and late in the course of disease natural history | 9 (1.7%) | 2 | Longstanding gout (66.7%) | |

In British English, hyperuricaemia.

Monosodium urate.

Clinical disease elements: gout flare, intercritical gout, chronic gouty arthritis, subcutaneous tophus.

Imaging disease elements: imaging evidence of monosodium urate crystal deposition, gouty bone erosion.

Delphi exercise

Seventy-six G-CAN members responded to the first round of the survey; of these, 72 (95%) completed all three rounds. The respondents included 34 members from Europe (45%), 24 from North America (32%), 13 from the Asia-Pacific region (17%), and five from Latin America (7%). The majority of respondents were rheumatologists (n=67, 88%); other physician specialists (n=4, 5%) and non-physician scientists (n=5, 7%) also participated.

Of the 13 disease states identified from the content analysis of the literature, nine were deemed to be meaningful by consensus agreement (Table 3). Of these nine disease states deemed to be meaningful, seven disease states reached consensus agreement on their preferred label: ‘asymptomatic hyperuricemia’, ‘asymptomatic monosodium urate crystal deposition’, ‘severe gout’, ‘tophaceous gout’, ‘erosive gout’, ‘first gout flare’ and ‘recurrent gout flares’ (Table 4). A detailed description of the Delphi exercise results regarding whether disease states were meaningful and preferred labels is shown in the Supplementary Material.

Table 3.

Results of the Delphi exercise for agreement about whether the proposed gout disease states are meaningful1.

| Disease states represented by disease element clusters | Delphi exercise | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus achieved2 (round) | Agreement (%) | ||

| Preclinical states | Hyperuricemia† without clinical disease elements3 of gout | Yes (1) | 84% |

| Imaging evidence of MSU4 crystal deposition without clinical disease elements3 of gout | Yes (1) | 89% | |

| Hyperuricemia† with imaging evidence of MSU4 crystal deposition without clinical disease elements3 of gout | Yes (1) | 86% | |

| Clinical states | Presence of MSU4 crystals with clinical disease elements3 of gout | Yes (1) | 97% |

| Presence of MSU4 crystals with any of the following: frequent recurrent gout flares, chronic gouty arthritis, subcutaneous tophi or imaging disease elements5 of gout | Yes (1) | 93% | |

| Presence of MSU4 crystals with subcutaneous tophi | Yes (1) | 89% | |

| Chronic gouty arthritis with at least one subcutaneous tophus | No | 74% after round 3 | |

| Presence of MSU4 crystals with any of the following: gout flare, chronic gouty arthritis; without subcutaneous tophi | No | 74% after round 3 | |

| Presence of MSU4 crystals with clinical disease elements3 of gout and with at least one gouty bone erosion | Yes (1) | 85% | |

| Disease course states | The first episode of gout flare without preceding intercritical gout | Yes (1) | 92% |

| More than one episode of gout flare with intercritical gout | Yes (1) | 88% | |

| Presence of MSU4 crystals with clinical disease elements3 of gout and early in the course of disease natural history | No | 67% after round 3 | |

| Presence of MSU4 crystals with clinical disease elements3 of gout and late in the course of disease natural history | No | 69% after round 3 | |

In British English, hyperuricaemia.

‘Meaningful’ defined as ‘having important implications for disease management and/or prognosis’.

Consensus defined as ≥80% agreement on preferred label.

Clinical disease elements: gout flare, intercritical gout, chronic gouty arthritis, subcutaneous tophus.

Monosodium urate.

Imaging disease elements: imaging evidence of monosodium urate crystal deposition, gouty bone erosion.

Table 4.

Results of the Delphi exercise and face-to-face consensus meeting for agreement on the labels for the disease states of gout.

| Disease states represented by disease element clusters | Delphi exercise | Face-to-face meeting | Agreed label | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus achieved1 (round) | Agreement (%) | Consensus achieved2 | Agreement (%) | |||

| Preclinical states | Hyperuricemia† without clinical disease elements2 of gout | Yes (3) | 85% | - | - | Asymptomatic hyperuricemia† |

| Imaging evidence of MSU3 crystal deposition without clinical disease elements3 of gout | Yes (3) | 86% | - | - | Asymptomatic monosodium urate crystal deposition | |

| Hyperuricemia† with imaging evidence of MSU3 crystal deposition without clinical disease elements2 of gout | No | - | Yes | 100% | Asymptomatic hyperuricemia† with monosodium urate crystal deposition | |

| Clinical states | Presence of MSU3 crystals with clinical disease elements2 of gout | No | - | Yes | 97% | Gout |

| Presence of MSU3 crystals with any of the following: frequent recurrent gout flares, chronic gouty arthritis, subcutaneous tophi or imaging disease elements4 of gout | Yes (2) | 82% | - | - | Severe gout5 | |

| Presence of MSU3 crystals with subcutaneous tophi | Yes (1) | 89% | - | - | Tophaceous gout | |

| Presence of MSU3 crystals with clinical disease elements2 of gout and with at least one gouty bone erosion | Yes (1) | 82% | - | - | Erosive gout | |

| Disease course states | The first episode of gout flare without preceding intercritical gout | Yes (3) | 83% | - | - | First gout flare |

| More than one episode of gout flare with intercritical gout | Yes (3) | 89% | - | - | Recurrent gout flares | |

In British English, hyperuricaemia.

Consensus defined as ≥80% agreement on preferred label.

Clinical disease elements: gout flare, intercritical gout, chronic gouty arthritis, subcutaneous tophus.

Monosodium urate.

Imaging disease elements: imaging evidence of monosodium urate crystal deposition, gouty bone erosion.

The disease state ‘severe gout’ was subsequently determined not to be clinically meaningful by consensus agreement2 during the face-to-face consensus meeting

Face-to-face meeting

A total of 35 G-CAN members attended the face-to-face meeting, the majority of whom were rheumatologists (n=33, 94%). Of those attending, 32 (91%) had also participated in all three rounds of the Delphi exercise. The panel included 18 members from Europe (51%), 11 from North America (31%), four from the Asia-Pacific region (11%), and two from Latin America (6%). The number of attendees participating in voting activities during the meeting varied from 28 to 35.

Agreement about which disease states are meaningful

The first item raised was the proposal that only disease states reaching consensus agreement as being meaningful during the Delphi exercise should be included within the final disease state consensus statement. This proposal was unanimously agreed upon (35 of 35 voting in favour), reducing the total number of disease states for consideration to nine; this was further reduced to eight when it was unanimously agreed to eliminate the disease state ‘the presence of monosodium urate crystals with any of the following: frequent recurrent gout flares, chronic gouty arthritis, subcutaneous tophi or imaging disease elements of gout’. This disease state, labelled ‘severe gout’ through the Delphi exercise, was thought to be a broad, non-specific state that would be difficult to define in clinical and research settings. It was also considered to be potentially misleading for gout treatment; for example, it might imply that patients not fulfilling this definition have ‘non-severe gout’ and that urate lowering therapy is not warranted in this case. For the cluster of disease elements: ‘hyperuricemia with imaging evidence of monosodium urate crystal deposition but without clinical disease elements of gout’, consensus agreement on this state being meaningful was achieved through the Delphi exercise. However, a number of respondents commented that this state was similar to the disease state, ‘asymptomatic monosodium urate crystal deposition’, and therefore may be redundant. After being put to vote, it was unanimously agreed (35/35 in favour) that this represented a unique and meaningful disease state, distinct from ‘asymptomatic monosodium urate crystal deposition’ which could represent a state of asymptomatic crystal deposition irrespective of serum urate concentration. The final eight disease states deemed meaningful by consensus agreement at the conclusion of both the Delphi exercise and face-to-face meeting are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

G-CAN endorsed labels and definitions for the disease states of gout.

| Consensus label | Consensus definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Preclinical states | 1. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia† | Hyperuricemia† in the absence of gout. |

| 2. Asymptomatic monosodium urate crystal deposition | Evidence of monosodium urate crystal deposition in the absence of gout. Monosodium urate crystal deposition may be demonstrated by imaging or microscopic analysis. | |

| 3. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia† with monosodium urate crystal deposition | Hyperuricemia† with evidence of monosodium urate crystal deposition in the absence of gout. Monosodium urate crystal deposition may be demonstrated by imaging or microscopic analysis. | |

| Clinical states | 4. Gout | A disease caused by monosodium urate crystal deposition with any of the following clinical presentations (current or prior): gout flare, chronic gouty arthritis or subcutaneous tophus. |

| 5. Tophaceous gout | Gout with at least one subcutaneous tophus. | |

| 6. Erosive gout | Gout with at least one gouty bone erosion. | |

| Disease course states | 7. First gout flare | The first episode of gout flare. |

| 8. Recurrent gout flares | More than one gout flare. | |

| Additional recommendation on disease states not addressed by the nomenclature | Where there is more than one disease state present, these can be combined (for example: tophaceous and erosive gout). Where there are additional elements present, not recognized as disease states, these will be labelled as the recognized disease state with or without additional disease elements (for example: tophaceous gout with chronic gouty arthritis). | |

In British English, hyperuricaemia.

Disease state labels

Consensus agreement was achieved on two disease state labels that remained unresolved after the Delphi exercise. These consensus labels were: ‘asymptomatic hyperuricemia with monosodium urate crystal deposition’ and ‘gout’ (Table 4). Further details on voting results are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

For the disease state referring to ‘hyperuricemia with imaging evidence of monosodium urate crystal deposition but without clinical disease elements of gout’, the label ‘asymptomatic hyperuricemia with monosodium urate crystal deposition’ was very close to reaching consensus following the Delphi exercise with 79% agreement; after being put to vote, consensus agreement was reached with 33 of 35 (94%) in favor of this label.

The second disease state label that remain unresolved following the Delphi exercise concerned the disease state ‘the presence of monosodium urate crystals with clinical disease elements of gout’. The two most preferred labels for this disease state following the Delphi exercise were ‘gout’ (56% agreement) and ‘symptomatic gout’ (43% agreement). This situation raised the fundamental question of whether ‘gout’ refers to the underlying pathophysiological process of monosodium urate crystal deposition or the clinically evident sequelae of crystal deposition. Consensus agreement for the label ‘gout’ to describe the disease state ‘the presence of monosodium urate crystals with clinical disease elements of gout’ was achieved with 34 of 34 (100%, one abstention) voting in favour. Thus, consensus was reached that the label ‘gout’ should be reserved for clinically evident disease.

Disease state definitions

Consensus agreement was achieved for the definitions of all eight disease states of gout (Table 5). Relevant issues arising from group discussions on the composition of these definitions are outlined here. Further details on voting results are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

When considering the definition of the disease state of gout it was considered important to include reference to ‘a disease caused by monosodium urate crystal deposition’ resulting in clinical disease elements. Therefore ‘gout’, according to this definition, requires current or prior clinically evident symptoms or signs resulting from monosodium urate crystal deposition. The issue was also raised as to whether ‘monosodium urate crystal-proven’ should be used as a modifier for the label ‘gout’. Although use of this descriptor is popular in clinical practice, it strictly refers to method of diagnosis, which can be achieved through a number of modalities, including synovial fluid analysis, ultrasound or dual-energy computed tomography. As this does not represent a separate disease state, it was not included in the recommended nomenclature.

Disease state labels not specifically addressed by the nomenclature

Throughout discussions it was acknowledged that disease states are not necessarily mutually exclusive and that the potential for overlap exists. It was also recognised that a consensus nomenclature cannot formally address all combinations of disease elements of gout. This led to the suggestion of a hierarchical approach to address those disease states that are not formally included in the agreed nomenclature. Specifically, the following recommendation was proposed: ‘Where there is more than one disease state present, these can be combined (for example, ‘tophaceous and erosive gout’). Where there are additional elements present, not recognized as disease states, these will be labelled as the recognized disease state with or without additional disease elements (for example, ‘tophaceous gout with chronic gouty arthritis’)’. This proposal was unanimously agreed on with 27 of 27 voting in favour (100%, one abstention).

DISCUSSION

In this project, we have achieved consensus agreement on the labels and definitions for disease states of gout. This project builds on the G-CAN-endorsed nomenclature for the disease elements of gout,7 which provided a foundation for both the extraction of disease element clusters in the content analysis of the literature, and for the formulation of disease state terminology. The G-CAN endorsed labels for disease elements and for disease states should be used concurrently where appropriate. These technical language labels and definitions for disease states [which have been endorsed by G-CAN] have been developed for use by health care professionals and non-physician scientists in clinical and research settings.

Our content analysis of the literature demonstrated that the existing terminology of the disease states of gout is deficient in a number of key areas. Disease states were, in general, infrequently mentioned, poorly defined or inconsistently labelled in the large body of contemporary gout-related literature that was analysed. With the exception of ‘asymptomatic hyperuricemia’, little mention was made of pre-clinical disease states defined by the presence of monosodium urate crystal deposition on imaging and the absence of clinical disease elements of gout. Given the latest advances and increasing availability of advanced imaging such as ultrasound and dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) in the detection of monosodium urate crystal deposition, there is a need to consistently label and define these pre-clinical states. This project has provided consensus labels and definitions for two further pre-clinical disease states: ‘asymptomatic monosodium urate crystal deposition’ and ‘asymptomatic hyperuricemia with monosodium urate crystal deposition’.

One of the key outcomes of this project was defining the label ‘gout’. There was much discussion about what constitutes ‘gout’, whether it is the presence of monosodium urate crystal deposition, or more specifically, the clinical manifestations resulting from this crystal deposition. In this consensus statement, we recommend the label ‘gout’ be used only when there are current or prior clinical symptoms or signs of monosodium urate crystal deposition. The prognostic significance of asymptomatic monosodium urate crystal deposition is currently uncertain and we recommend that the label ‘gout’ is not used in the absence of current or prior clinical symptoms or signs caused by monosodium urate crystal deposition. Another key outcome was the rejection of non-specific labels of the clinical features of gout, such as ‘severe gout’, which are, despite their ambiguity, present in a number of international gout management guidelines.8–11 Where cluster of elements cannot be described using a single label, guidance has been provided for the use of consistent nomenclature.

In summary, this consensus statement presents recommended labels and definitions for disease states of gout. The Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN) recommends the use of these labels when communicating in the scientific literature and in professional practice.

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGES.

The language used to describe gout is characterised by a lack of consistent terminology and definitions.

Consensus agreement has been reached about the labels and definitions of disease states of gout.

The agreed labels are: ‘asymptomatic hyperuricemia’, ‘asymptomatic monosodium urate crystal deposition’, ‘asymptomatic hyperuricemia with monosodium urate crystal deposition’, ‘gout’, ‘tophaceous gout’, ‘erosive gout’, ‘first gout flare’ and ‘recurrent gout flares’.

The label ‘gout’ should be restricted to current or prior clinically evident disease caused by monosodium urate crystal deposition.

The Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN) recommends the use of these labels when communicating in the scientific literature and in professional practice.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Pamela Love (G-CAN Executive Director and Board Secretary), Sharon Andrews (G-CAN Executive Assistant) and Andrea Love for assisting in the organisation of the face-to-face consensus meeting.

Funding

Work by DB was supported by an Australian Rheumatology Association/Arthritis South Australia Post-Graduate Rheumatology grant.

Footnotes

Disclosures

AKT has received speaking fees and honoraria for advisory boards from Berlin Chemie Menarini, Novartis, Grünenthal and AstraZeneca.

JAS has received consultant fees from Crealta/Horizon, Medisys, Fidia, UBM LLC, Medscape, WebMD, the National Institutes of Health and the American College of Rheumatology. JAS owns stock options in Amarin pharmaceuticals and Viking therapeutics. JAS is a member of the executive of OMERACT, an organization that develops outcome measures in rheumatology and receives arms-length funding from 36 companies. JAS is a member of the Veterans Affairs Rheumatology Field Advisory Committee. JAS is the editor and the Director of the UAB Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Satellite Center on Network Meta-analysis. JAS previously served as a member of the following committees: member, the American College of Rheumatology’s (ACR) Annual Meeting Planning Committee (AMPC) and Quality of Care Committees, the Chair of the ACR Meet-the-Professor, Workshop and Study Group Subcommittee and the co-chair of the ACR Criteria and Response Criteria subcommittee.

ND has received speaking fees from Pfizer, Horizon, Janssen, and AbbVie, consulting fees from Horizon, AstraZeneca, Dyve Biosciences, Hengrui, and Kowa, and research funding from Amgen and AstraZeneca.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bursill D, Taylor WJ, Terkeltaub R, Dalbeth N. The nomenclature of the basic disease elements of gout: A content analysis of contemporary medical journals. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018; 48(3): 456–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards NL, Malouf R, Perez-Ruiz F, Richette P, Southam S, DiChiara M. Computational Lexical Analysis of the Language Commonly Used to Describe Gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016; 68(6): 763–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liddle J, Roddy E, Mallen CD, et al. Mapping patients’ experiences from initial symptoms to gout diagnosis: a qualitative exploration. BMJ Open 2015; 5(9): e008323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaccher S, Kannangara DR, Baysari MT, et al. Barriers to Care in Gout: From Prescriber to Patient. J Rheumatol 2016; 43(1): 144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh CP, Prior JA, Chandratre P, Belcher J, Mallen CD, Roddy E. Illness perceptions of gout patients and the use of allopurinol in primary care: baseline findings from a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016; 17(1): 394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bardin T, Richette P. Definition of hyperuricemia and gouty conditions. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014; 26(2): 186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bursill D, Taylor WJ, Terkeltaub R, et al. Gout, Hyperuricemia, and Crystal-Associated Disease Network Consensus Statement Regarding Labels and Definitions for Disease Elements in Gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019; 71(3): 427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hui M, Carr A, Cameron S, et al. The British Society for Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017; 56(7): e1–e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012; 64(10): 1431–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(1): 29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivera F, Andres M, Carmona L, et al. Multinational evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout: integrating systematic literature review and expert opinion of a broad panel of rheumatologists in the 3e initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73(2): 328–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.