Abstract

Hepatitis C (HCV) and alcohol use are patient risk factors for accelerated fibrosis progression, yet few randomized controlled trials have tested clinic-based alcohol interventions. 181 patients with HCV and qualifying alcohol screener scores at three liver center settings were randomly assigned to: 1) medical provider-delivered Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), including motivational interviewing counseling and referral out for alcohol treatment (SBIRT-only), or 2) SBIRT plus six months of integrated co-located alcohol therapy (SBIRT+Alcohol Treatment). The Timeline Followback Method assessed alcohol use at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months. Co-primary outcomes were alcohol abstinence at 6 months and heavy drinking days between 6 and 12 months. Secondary outcomes included grams of alcohol consumed per week at 6 months. Mean therapy hours across six months were 8.8 for SBIRT-only and 10.1 for SBIRT+Alcohol Treatment participants. The proportion of participants exhibiting full alcohol abstinence increased from baseline to 3, 6, and 12 months in both treatment arms, but no significant differences were found between arms (baseline to 6 months, 7.1% to 20.5% for SBIRT-only; 4.2% to 23.3% for SBIRT+Alcohol Treatment; p=0.70). Proportions of participants with any heavy drinking days decreased in both groups at 6 months but did not significantly differ between the SBIRT-only (87.5% to 26.7%) and SBIRT+Alcohol Treatment (85.7% to 42.1%) arms (p=0.30). Although both arms reduced average grams of alcohol consumed per week from baseline to 6 and 12 months, between-treatment effects were not significant. Conclusion: Patients with current or prior HCV-infection will engage in alcohol treatment when encouraged by liver medical providers. Liver clinics should consider implementing provider-delivered SBIRT and tailored alcohol treatment referrals as part of standard of care.

Keywords: Behavioral, integrated care, therapy, Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral to Treatment, SBIRT

Affecting an estimated 71 million people worldwide (1), chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection can lead to fibrosis, cirrhosis and life-shortening complications of portal hypertension and hepatocellular carcinoma (2). Alcohol use in the setting of HCV infection is associated with increased rates of fibrosis progression, liver-related mortality, and overall mortality (3).

Compared to people without HCV, people with HCV infection living in the United States (US) are estimated to be excessive drinkers 1.3 times more often (4). Consequently, guidelines recommend abstinence from alcohol and clinical interventions to facilitate alcohol cessation in patients with active infection (5, 6). Even after HCV cure with therapy, patients with cirrhosis remain at higher risk for fibrosis progression and hepatocellular carcinoma; these patients are particularly cautioned against excessive alcohol use (5, 6).

“Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT)” is an evidence-based alcohol-reduction practice. This 5–10 minute intervention includes an alcohol screener followed by dialogue with patients to elicit their thoughts about their alcohol use. SBIRT follows the principles of Motivational Interviewing, “a person-centered, goal-oriented method of communication for eliciting and strengthening intrinsic motivation for positive change” and has a strong evidence base (7, 8). Systematic reviews (9, 10) and meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials (9) show the effectiveness of SBIRT in reducing hazardous drinking in patients presenting in primary care and other settings. Across 32 controlled studies, SBIRT was more effective than no counseling, and often as effective as more extensive treatment (10). The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recommends behavioral counseling interventions for primary care patients with risky or harmful alcohol use (11). While SBIRT has been adopted to address risky alcohol use in various healthcare settings (12), randomized controlled trials of SBIRT delivered in hepatology clinics have not been conducted.

The main treatment arm of this trial encompasses a co-located integrated care model addressing both HCV and alcohol use. Integrated care can be conceptualized on a continuum from services being coordinated (information shared across settings), to co-located (both services delivered at one location), to integrated (merged medical and behavioral health components in one treatment plan) (13). This trial builds upon the experience of our pilot study with co-located and integrated HCV and alcohol treatment components, including individual and group therapy; participants experienced alcohol abstinence rates of 21% at baseline versus 44% at six months (14).

For a comparison group, we choose SBIRT instead of standard of care because indications in 2014 were that SBIRT would become widely implemented in liver clinics and thus become standard of care. Also, because SBIRT is less resource-intensive, we wanted to know if integrated HCV-alcohol treatment was superior to SBIRT or not. To our knowledge, the current study is the first randomized controlled trial to compare provider-delivered SBIRT to provider-delivered SBIRT plus co-located integrated HCV-alcohol treatment in hepatology clinics. The primary aim was to compare the efficacy of these two interventions on two co-primary outcomes, alcohol abstinence and relapse, among patients with ongoing alcohol use with current or prior chronic HCV.

Methods

Design Overview

This unblinded, randomized, pragmatic trial enrolled patients with current or prior chronic HCV who drank alcohol. Participants were randomly assigned to either SBIRT-only (i.e., the SBIRT model that includes a patient-administered alcohol Screener, medical provider-delivered Brief Intervention using motivational interviewing counseling, and Referral to outside alcohol Treatment) or SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment (i.e., SBIRT plus up to six months of integrated co-located individual and/or group therapy that provided motivational, cognitive, and behavioral strategies to reduce alcohol consumption).

Trial design details have been published (15) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02176980). The study received a priori approval by the Duke Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB), the University of North Carolina (UNC) Medical Center IRB, and the Durham Veterans Administration (VA) IRB and was also overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board. Protocols conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

Setting and Participants

Participants were recruited between October 2014 and September 2017 from three diverse liver center settings. The Duke University Health System included several academically affiliated gastroenterology (GI), hepatology, and infectious diseases (ID) clinics based on the campus and in the community of Durham, North Carolina. The UNC Medical Center – Chapel Hill included academically affiliated public liver clinics based on the campus and an off-site clinic in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Finally, the Durham VA Medical Center included the GI, liver, ID-GI, and HCV treatment management clinics.

Inclusion criteria required previously confirmed chronic HCV, irrespective of HCV treatment status (before, during, or after direct acting antiviral (DAA) therapy); an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (16) score of ≥4 for women or ≥8 for men; at least one alcoholic drink in the past 60 days; age 18 years or older; ability to understand and speak English; not currently engaged in effective substance abuse treatment; willing to be involved in the study for 12 months; and able to access transportation to attend at least one individual therapy session. Patients with active psychosis, as determined by referring medical providers, were excluded.

Randomization

After enrollment and baseline data collection, within each site, each participant was randomly assigned, randomization sequence, generated by independent statisticians, to SBIRT-only or SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment on a 1:1 basis, stratified by AUDIT score (<20; ≥20). An AUDIT score of 20 or greater indicates likely alcohol dependence (17). At the VA site only, randomization was also stratified by sex because fewer patients are women. The randomization schema was programmed into survey software; individual assignments were concealed from study staff until the intervention was assigned.

Interventions

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT). Provider-patient conversations about alcohol were already standard of care in the three sites. For the study, we structured this conversation using SBIRT. HCV patients completed a self-reported AUDIT survey (16) upon clinic visit and then saw medical providers (HCV specialists with medical, physician assistant, and nurse practitioner degrees) trained in SBIRT, who provided counseling based on patients’ AUDIT answers. Medical providers were encouraged to conduct SBIRT during every visit for patients indicating current alcohol use, whether or not they were enrolled in the study or had previously received SBIRT. SBIRT was especially encouraged for scores (≥8 for men and ≥4 for women) that meet the recommendation of the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism guide (18). Patients received SBIRT prior to being approached by their medical provider about study participation. This Brief Intervention aspect of SBIRT consisted of talking with patients for 5–10 minutes about their thoughts on their alcohol use using the principles of Motivational Interviewing (7, 8). Pre-study, all medical providers attended a two-hour educational session about the FRAMES steps: giving Feedback on how the patient’s alcohol use may affect their current and future health; stating that it is the patient’s Responsibility to change behavior; Advising to stop drinking due to medical concerns; offering a Menu of options for cutting down on drinking; expressing Empathy; and reinforcing the patient’s Self-efficacy to change (19).

SBIRT-only group. Following SBIRT and study consent, participants randomly assigned to the SBIRT-only group were referred by study staff for alcohol treatment that was tailored to their individual needs based on insurance status, geographic location, and transportation resources. Example referral sites included university-affiliated outpatient programs, short-term or long-term residential detoxification/addiction treatment, and Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous alone or in conjunction with other treatments.

SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment group. Following SBIRT and study consent, participants randomly assigned to the integrated HCV-alcohol treatment were contacted by their site’s addiction therapist. The integrated treatment differed slightly by site. At Duke, an addiction therapist was co-located in the clinics; at the VA, one addiction therapist from within the VA system was available; and at UNC, a therapist was located across the street from the UNC liver clinic. The addiction therapist and medical provider communicated through on-site contact and shared notes via the electronic medical record (EMR). To standardize implementation across sites and providers, a 24-session manual-based treatment with content on HCV and alcohol use was developed. The addiction therapist offered up to a total of 36 individual and group therapy sessions spaced according to addiction therapist recommendations and participant preference. Therapists used principles of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (20), Motivational Enhancement Therapy (8), and substance abuse treatment, applicable to both alcohol and substance use. The session content integrated HCV and alcohol issues into alcohol treatment, liver health, and personal domains, with didactic content and homework in the manual. Therapy began with three core sessions for increasing knowledge about HCV, alcohol, and liver health; enhancing motivation to decrease alcohol use; developing multiple skills for decreasing alcohol use; implementing alcohol reduction behaviors and meaningful activities; and improving health and well-being practices. Additional sessions consisted of content (e.g., sleep) jointly chosen for relevance by the participant and addiction therapist. Therapy emphasized alcohol reduction but also addressed substance use when present. All sessions were audiorecorded and quality assurance was conducted on all initial sessions per therapist followed by a random subset of throughout the study.

Although in-person individual therapy was encouraged, due to the pragmatic nature of the study, phone therapy was also offered and commonly used to increase retention. Group therapy was offered at the Duke site only. Psychiatric treatment was offered by a study psychiatrist to participants who requested a consult or when recommended by the addiction therapist. The study psychiatrist provided services for the duration of their 6-month participation in the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment arm in the liver clinic setting and documented encounters in the shared EMR. Tailored treatment recommendations consisted of prescribing medications for anxiety, depression, or alcohol relapse-prevention, as appropriate.

We hypothesized that the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment participants would do significantly better than SBIRT-only participants on all primary and secondary outcomes.

Outcomes and Follow-up

Primary outcomes. The co-primary study outcomes were: a) alcohol abstinence, defined as the proportion of participants with no alcohol consumed during the 30 days in the 6th month post-baseline, and b) alcohol relapse, defined as the proportion of participants with any heavy drinking days (i.e., ≥5 or more drinks for men and ≥4 for women) occurring in the 7 to 12 months after enrollment among participants with full abstinence at the 6th month (21).

The Timeline Followback, a reliable and validated interview measure for alcohol use outcomes, was used to assess primary outcomes (22). Compared to data from blood tests and reports from friends and family members, the self-reported Timeline Followback method has been shown to be more complete over time and result in higher reported amounts of alcohol use (17, 23). In addition, to encourage accurate reporting, staff collected urine samples at in-person interviews and informed participants that the sample would be tested for alcohol and substance use. Study staff were trained on the Timeline Followback by one of the measure’s original developers. Participants were asked to recall the type and amount of alcohol consumed per day for the past 90 or 180 days, assisted by identifying special dates on calendars and creating patterns of drinking. Staff recorded responses on paper and conducted double data entry for this primary outcomes measure.

Secondary outcomes. Using the Timeline Followback, our secondary alcohol outcomes included: 1) grams of alcohol consumed per week at 6 months; 2) grams of alcohol consumed per week at 12 months; 3) the number of heavy drinking days in the 6-month period after enrollment; and 4) the number of alcohol-abstinent days at 12 months. Additionally, self-reported and urine-tested substance use data were analyzed.

Follow-up. We conducted interviews at baseline and at 3, 6, and 12 months. For participants assigned to the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment arm, 6 months marked the end of their treatment period.

Descriptive Measures

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-8, which consists of eight items assessing symptoms during the past two weeks (24). Scores range from 0 to 24. Based on validation studies, depression was defined as a score ≥10 (25). Anxiety symptoms were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, which consists of seven items assessing symptoms during the past two weeks (26). Scores range from 0 to 21 with anxiety defined as a score ≥8 (27).

We abstracted participant medical records for liver status. Participants were considered to have compensated cirrhosis if they had no history of complications of portal hypertension plus liver biopsy consistent with cirrhosis, transient elastography score greater than 12.5 kPa, or FIB-4 scores greater than 3.25. Decompensated cirrhosis was defined as history of ascites, variceal hemorrhage, or hepatic encephalopathy.

Statistical Analysis

As previously reported, in our pre-study power analysis for dependent drinkers at six months we assumed a 39% abstinence rate for the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment group and 10% for the SBIRT-only group (15). For harmful drinkers, we assumed a 57% versus 25% abstinence rate for the respective groups. Between six and twelve months, we expected heavy drinking days in the SBIRT-only group to decrease by 29% and in the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment group to decrease by 42%. We sought 230 patients. The final sample size of 181 patients provided approximately 90% power to test the co-primary hypotheses (15).

Analysis was intent-to-treat, i.e., included all participants as randomly assigned. A priori demographic and disease characteristics were compared between treatment intervention arms using the t-test (continuous variables) or chi-square test (categorical variables). Descriptive statistics were computed for all outcomes by treatment intervention arm, at each time point in the overall sample and within specific participant subgroups of interest (i.e., at baseline, heavy drinkers, non-heavy/light drinkers, participants with and without cirrhosis). Mean numbers of abstinent days and heavy drinking days were plotted over time by treatment arm.

To examine two binary outcomes: 1) full abstinence from alcohol during month 6 and 2) any heavy drinking days during months 7–12 post baseline, among the participants that fully abstained during month 6, we applied a Robust Poisson regression model using a natural log link function and robust variance estimator. Model variables included: time point in the course of the study (baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months post-baseline), baseline date, treatment intervention arm (SBIRT-only; SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment), baseline AUDIT score group (<20; ≥ 20), treatment site (Duke; UNC; VA), and any demographic or disease characteristics that significantly differed between treatment arms despite the randomization. Population-averaged effects were specified for repeated observations. Using the parameter estimates from each model, differences between one month pre-baseline and month 6 post-baseline for full abstinence, and between 3 months pre-baseline and months 7–12 post-baseline for any heavy drinking days, were compared between treatment intervention arms.

Additionally, utilizing the same model variables as in the Poisson regression, we used a Generalized Least Squares regression model to examine continuous outcomes: 1) the number of heavy drinking days, among the participants who fully abstained during month 6, 2) grams of alcohol consumed, and 3) number of heavy drinking days. In all models, population-averaged effects were specified for repeated observations. Using the parameter estimates from each model, differences in the number of heavy drinking days between 3 months pre-baseline and months 7–12 post-baseline were compared between treatment arms; differences in grams of alcohol consumed and number of heavy drinking days between 1 month pre-baseline and month 6 post-baseline were compared between treatment arms. For each regression model, only observations with complete data for the outcome and independent variables were included. Subgroup analyses were considered exploratory; we did not control for multiplicity in these analyses.

All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata v 15.1 (28).

Results

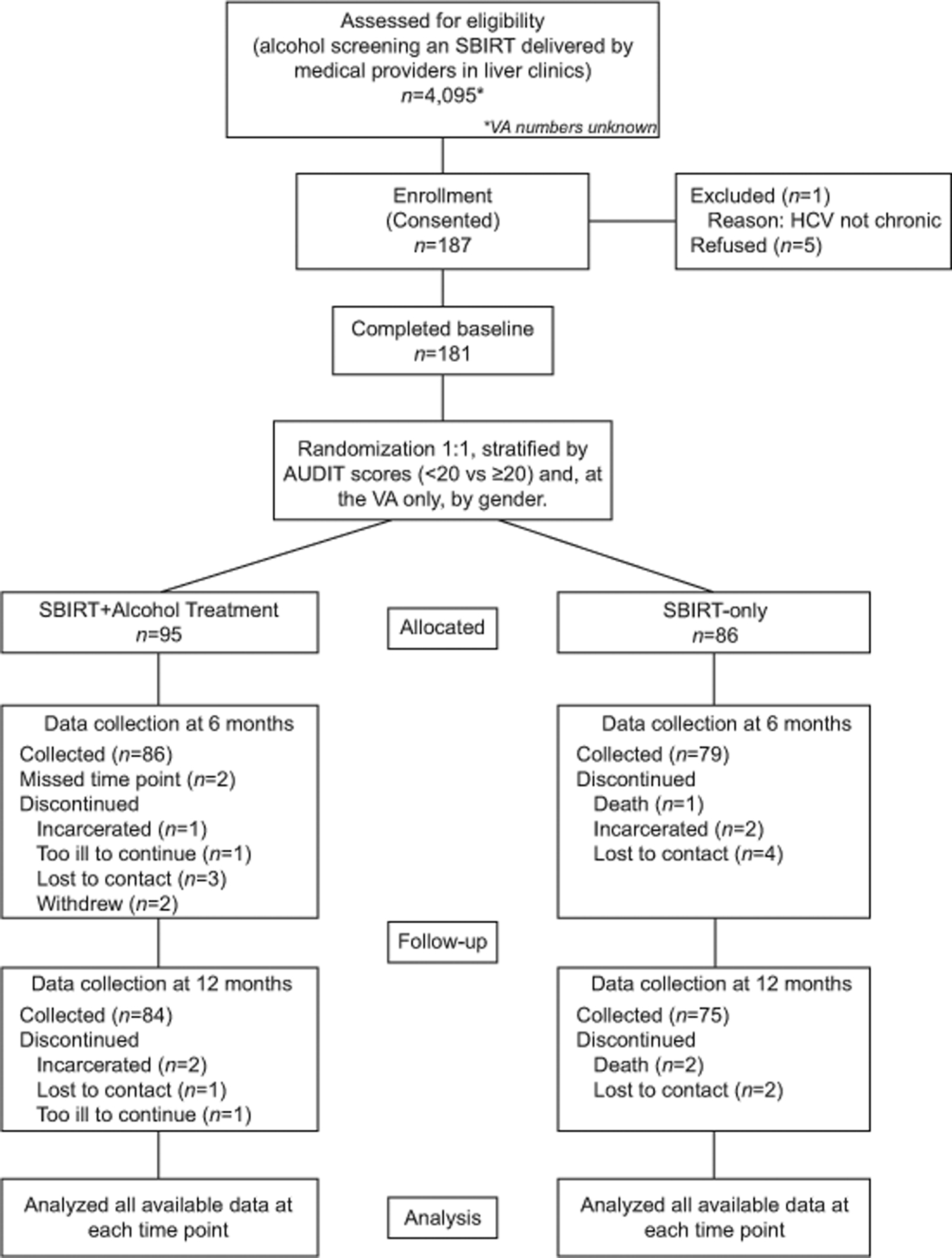

The study CONSORT flow diagram is provided in Figure 1. Between October 2014 and September 2017, 181 patients were randomly assigned, with 95 to SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment and 86 to SBIRT-only. Interview data at 6 months were available for 86/95 (90.5%) SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment participants and 79/86 (91.8%) SBIRT-only participants. SBIRT-only participants experienced 7, and SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment participants also experienced 7 adverse events, defined as hospitalization and death. No adverse events could be specifically traced to either the SBIRT-only or the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment.

Figure 1.

Hep ART study participant flowchart

Primary Outcomes

Tables 1 and 2 depict the baseline participant demographic and disease characteristics. At the Duke site, 109 participants were randomized; at UNC, 53; and at the VA, 19. Factors were well-balanced between treatment arms except for race-ethnicity, which differed significantly across three levels (p=0.003), so the statistical models included it as a covariate.

Table 1.

Demographics of participants (N=181) at baseline by treatment arm

| Characteristics | SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment (N=95) | SBIRT Only (N=86) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) or M (SD) | % (n) or M (SD) | % (n) or M (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 55.0 (9.6) | 54.8 (9.5) | 54.9 (9.5) |

| Female | 28.4% (27) | 29.1% (25) | 28.7% (52) |

| Male | 71.6% (68) | 70.9% (61) | 71.3% (129) |

| Married/cohabitating | 27.5% (25) | 33.7% (28) | 30.5% (53) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 70.5% (67) | 46.5% (40) | 59.1% (107) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 24.2% (23) | 38.4% (33) | 30.9% (56) |

| Other (including bi-/multi-racial) | 5.3% (5) | 15.1% (13) | 9.9% (18) |

| High school or below | 58.9% (56) | 59.3% (51) | 59.1% (107) |

| Some college or associate degree | 30.5% (29) | 32.6% (28) | 31.5% (57) |

| Bachelor degree or above | 10.5% (10) | 8.1% (7) | 9.4% (17) |

| Full time | 26.3% (25) | 30.2% (26) | 28.2% (51) |

| Part time | 13.7% (13) | 9.3% (8) | 11.6% (21) |

| Unemployed | 14.7% (14) | 23.3% (20) | 18.8% (34) |

| Disabled | 36.8% (35) | 31.4% (27) | 34.3% (62) |

| Other | 8.4% (8) | 5.8% (5) | 7.2% (13) |

| Individual monthly income in dollars | 1,665 (2,552) | 1,476 (1,573) | 1,575 (2,143) |

| Own or rent apartment, room or house | 69.5% (66) | 73.3% (63) | 71.3% (129) |

| Someone else’s apartment, room or house | 21.1% (20) | 17.4% (15) | 19.3% (35) |

| Shelter, street or outdoors | 6.3% (6) | 4.7% (4) | 5.5% (10) |

| Other | 3.2% (3) | 4.7% (4) | 3.9% (7) |

| Private | 32.6% (31) | 30.2% (26) | 31.5% (57) |

| Government: Medicare, Medicaid etc. | 45.3% (43) | 41.9% (36) | 43.6% (79) |

| Other public: VA etc. | 8.4% (8) | 11.6% (10) | 9.9% (18) |

| Local charity care plan | 2.1% (2) | 2.3% (2) | 2.2% (4) |

| None | 11.6% (11) | 14.0% (12) | 12.7% (23) |

| Duke | 57.9% (55) | 62.8% (54) | 60.2% (109) |

| UNC | 28.4% (27) | 30.2% (26) | 29.3% (53) |

| VA | 13.7% (13) | 7.0% (6) | 10.5% (19) |

Notes.

Data are missing for 7 participants for marital status and 1 participant for income in dollars; this latter participant reported that his monthly income fell between $500 and $1,000.

Table 2:

Disease characteristics of participants at baseline

| Characteristics | SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment (N=95) | SBIRT Only (N=86) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time since HCV diagnosis (years) | 8.1 (8.7) | 7.3 (7.8) | 7.7 (8.3) |

| Naïve (including pre-treatment) | 80.0% (76) | 80.2% (69) | 80.1% (145) |

| Experienced | 20.0% (19) | 19.8% (17) | 19.9% (36) |

| No cirrhosis | 67.4% (64) | 68.6% (59) | 68.0% (123) |

| Compensated cirrhosis | 31.6% (30) | 29.1% (25) | 30.4% (55) |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 1.1% (1) | 2.3% (2) | 1.7% (3) |

| AUDIT ≥ 20 | 17.9% (17) | 16.3% (14) | 17.1% (31) |

| None/mild | 11.6% (11) | 7.0% (6) | 9.4% (17) |

| Moderate | 20.0% (19) | 24.4% (21) | 22.1% (40) |

| Severe | 68.4% (65) | 68.6% (59) | 68.5% (124) |

| 5+ days, i.e. heavy alcohol use | 55.8% (53) | 55.3% (47) | 55.6% (100) |

| 0–4 days, i.e. lighter alcohol use | 44.2% (42) | 44.7% (38) | 44.4% (80) |

| Marijuana | 52.6% (50) | 42.4% (36) | 47.8% (86) |

| Other drugs[3] | 34.7% (33) | 24.4% (21) | 29.8% (54) |

| Presence of HIV | 8.4% (8) | 3.5% (3) | 6.1% (11) |

| Depression symptoms severity mean score (PHQ8) | 8.0 (5.4) | 7.5 (5.4) | 7.8 (5.4) |

| Presence of depression (PHQ8≥10) | 36.8% (35) | 37.2% (32) | 37.0% (67) |

| Anxiety symptoms severity mean score (GAD7) | 7.3 (5.3) | 7.7 (6.1) | 7.5 (5.7) |

| Presence of anxiety (GAD7≥10) | 30.9% (29) | 38.4% (33) | 34.4% (62) |

| Presence of anxiety and/or depression | 42.6% (40) | 47.7% (41) | 45.0% (81) |

| Transport time to and from clinic (minutes) | 81 (66) | 86 (74) | 84 (70) |

Notes.

Alcohol Use Disorder was not assessed clinically but was based on responses to structured research interview questions.

Assessment of binge drinking was based on structured timeline followback (TLFB) research interview questions.

A binge drinking day = 5 or more standard drinks for men, 4 or more standard drinks for women.

Other drugs include cocaine, heroin, non-prescription methadone, and opioids and sedatives in amounts greater than prescribed.

Data were missing in 3 participants for (self-reported) time since HCV diagnosis; 1 participant for binge drinking; 1 participant for marijuana use; 1 participant for anxiety; and 1 participant for transport time to and from the clinic.

HCV diagnosis year was missing for 10 participants in their electronic medical records; therefore their self-reported year of diagnosis was used for analysis.

Results for full abstinence during month 6 by intervention are shown in Table 3. The proportion of participants exhibiting full alcohol abstinence increased from baseline to months 3, 6, and 12 in both treatment arms. No significant differences were found between treatment arms for full abstinence in the 6th month versus baseline (7.1% to 20.5%, SBIRT-only baseline and month 6; 4.2% to 23.3%, SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment baseline and month 6; estimated coefficient for the 6-month intervention effect is 0.65 (95% CI −0.65, 1.96), p=0.33).

Table 3:

Percentages of participants with full abstinence for 30 days by intervention

| % (n/N) | 30 days prior to BL | 30 days comprising the 3rd month post BL | 30 days comprising the 6th month post BL (primary outcome) | 30 days comprising the 12th month post BL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The entire sample (N=181) | N=180 | N=164 | N=164 | N=154 |

| SBIRT Only | 7.1% (6/85)* | 19.0% (15/79) | 20.5% (16/78)** | 26.4% (19/72) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 4.2% (4/95) | 21.2% (18/85) | 23.3% (20/86) | 25.6% (21/82) |

| Six-month intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 0.65 [−0.65, 1.96]; p=.327 | |||

| Males (N=129) | N=128 | N=116 | N=116 | N=106 |

| SBIRT Only | 6.7% (4/60) | 19.3% (11/57) | 19.3% (11/57) | 27.5% (14/51) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 4.4% (3/68) | 18.6% (11/59) | 16.9% (10/59) | 25.5% (14/55) |

| Six-month intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 0.33 [−1.24, 1.89]; p=.680 | |||

| Females (N=52) | N=52 | N=48 | N=48 | N=48 |

| SBIRT Only | 8.0% (2/25) | 18.2% (4/22) | 23.8% (5/21) | 23.8% (5/21) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 3.7% (1/27) | 26.9% (7/26) | 37.0% (10/27) | 25.9% (7/27) |

| Six-month intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 1.30 [−1.18, 3.78]; p=.305 | |||

| Black, single-racial, non-Hispanic (N=107) | N=107 | N=99 | N=101 | N=97 |

| SBIRT Only | 7.5% (3/40) | 13.2% (5/38) | 21.1% (8/38) | 25.0% (9/36) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 4.5% (3/67) | 18.0% (11/61) | 25.4% (16/63) | 26.2% (16/61) |

| Six-month intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 0.73 [−0.87, 2.33]; p=.372 | |||

| Other races (including White, bi- and multi-racial) and/or Hispanic (N=74) | N=73 | N=65 | N=63 | N=57 |

| SBIRT Only | 6.7% (3/45) | 24.4% (10/41) | 20.0% (8/40) | 27.8% (10/36) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 3.6% (1/28) | 29.2% (7/24) | 17.4% (4/23) | 23.8% (5/21) |

| Six-month intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 0.50 [−2.08, 3.09]; p=.702 | |||

| Heavy alcohol users at BL (N=100) | N=100 | N=92 | N=94 | N=87 |

| SBIRT Only | 0.0% (0/47) | 13.3% (6/45) | 10.9% (5/46) | 21.4% (9/42) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 0.0% (0/53) | 12.8% (6/47) | 14.6% (7/48) | 11.1% (5/45) |

| Intervention effect model does not converge | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00]; p<.001 | |||

| Lighter alcohol users at BL (N=80) | N=80 | N=71 | N=69 | N=66 |

| SBIRT Only | 15.8% (6/38) | 27.3% (9/33) | 35.5% (11/31) | 34.5% (10/29) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 9.5% (4/42) | 31.6% (12/38) | 34.2% (13/38) | 43.2% (16/37) |

| Six-month intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 0.49 [−0.83, 1.82]; p=.464 | |||

| Severe alcohol use disorder at BL (N=124) | N=123 | N=111 | N=110 | N=106 |

| SBIRT Only | 6.9% (4/58) | 14.8% (8/54) | 19.2% (10/52) | 26.5% (13/49) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 4.6% (3/65) | 21.1% (12/57) | 15.5% (9/58) | 14.0% (8/57) |

| Six-month intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 0.22 [−1.35, 1.79]; p=.780 | |||

| Moderate, mild, or none alcohol user disorder at BL (N=57) | N=57 | N=53 | N=54 | N=48 |

| SBIRT Only | 7.4% (2/27) | 28.0% (7/25) | 23.1% (6/26) | 26.1% (6/23) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 3.3% (1/30) | 21.4% (6/28) | 39.3% (11/28) | 52.0% (13/25) |

| Six-month intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 1.07 [−1.44, 3.59]; p=.402 | |||

| Presence of cirrhosis at BL (N=58) | N=57 | N=54 | N=53 | N=49 |

| SBIRT Only | 7.7% (2/26) | 16.0% (4/25) | 16.7% (4/24) | 31.8% (7/22) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 6.5% (2/31) | 20.7% (6/29) | 24.1% (7/29) | 25.9% (7/27) |

| Six-month intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 0.47 [−1.53, 2.46]; p=.647 | |||

| No cirrhosis present at BL (N=123) | N=123 | N=110 | N=111 | N=105 |

| SBIRT Only | 6.8% (4/59) | 20.4% (11/54) | 22.2% (12/54) | 24.0% (12/50) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 3.1% (2/64) | 21.4% (12/56) | 22.8% (13/57) | 25.5% (14/55) |

| Six-month intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 0.84 [−0.95, 2.62]; p=.357 | |||

Notes.

BL = baseline

Coef = Coefficient

CI = confidence interval

Table 4 presents the proportion of participants with any heavy drinking days and the number of heavy drinking days per month, among participants who fully abstained in the 6th month (N=37), by time period and treatment arm. No significant differences were found. Proportions of participants with any heavy drinking days decreased from 85.7% over 3 months before baseline to 42.1% over months 7–12 post baseline in the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment arm and 87.5% to 26.7% in the SBIRT-only arm (estimated coefficient for the intervention effect (95% CI) is 0.5 (−0.5, 1.4); p=0.33). Mean number of heavy drinking days decreased from 6.8 (SD=7.0) to 1.1 (SD=1.2) in the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment arm and from 8.1 (SD=10.9) to 1.3 (SD=1.8) in the SBIRT-only arm (p=0.68).

Table 4:

Drinking relapse among participants who fully abstained during the 30 days comprising the 6th month post baseline

| Characteristics | 3 months before BL | Months 7–12 post BL |

|---|---|---|

| Any heavy drinking days, % (n/N) | ||

| SBIRT Only (N=16) | 87.5% (14/16) | 26.7% (4/15) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment (N=21) | 85.7% (18/21) | 42.1% (8/19) |

| Intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 0.47 [−0.48, 1.43]; p=.328 | |

| Number of heavy drinking days per month, mean (SD), median | ||

| SBIRT Only (N=16) | 8.1 (10.9), 3.7 | 1.3 (1.8), 0.6 |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment (N=21) | 6.8 (7.0), 3.7 | 1.1 (1.2), 0.6 |

| Intervention effect, coef (95% CI); p | 1.1 [−4.0, 6.1]; p=.681 | |

Notes.

Heavy drinking day = 5+ standard drinks for men or 4+ standard drinks for women on a day

BL = baseline

Coef = coefficient

CI = confidence interval

Subgroup Analyses of Primary Outcomes

No significant intervention effects were found for full abstinence among any of the participant subgroups analyzed: heavy alcohol users, light alcohol users, participants with cirrhosis, and participants without cirrhosis (Table 3).

Secondary Outcomes

Both arms exhibited significantly fewer grams (g) alcohol consumed per week from baseline to months 6 and 12. On average, SBIRT-only participants consumed 186g/week (SD=165) at baseline and 94g/week (SD=123) in month 6. SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment participants consumed 206g/week (SD=243) at baseline and 134g/week (SD=246) in month 6. Results were similar at 12 months. No significant between-treatment effects were observed (6-month intervention effect estimated coefficient is 22.1g/week (95% CI: −32.7, 76.9), p=0.43; 12-month intervention effect estimated coefficient is 27.7g/week (95% CI: −25.7, 81.1), p=0.31).

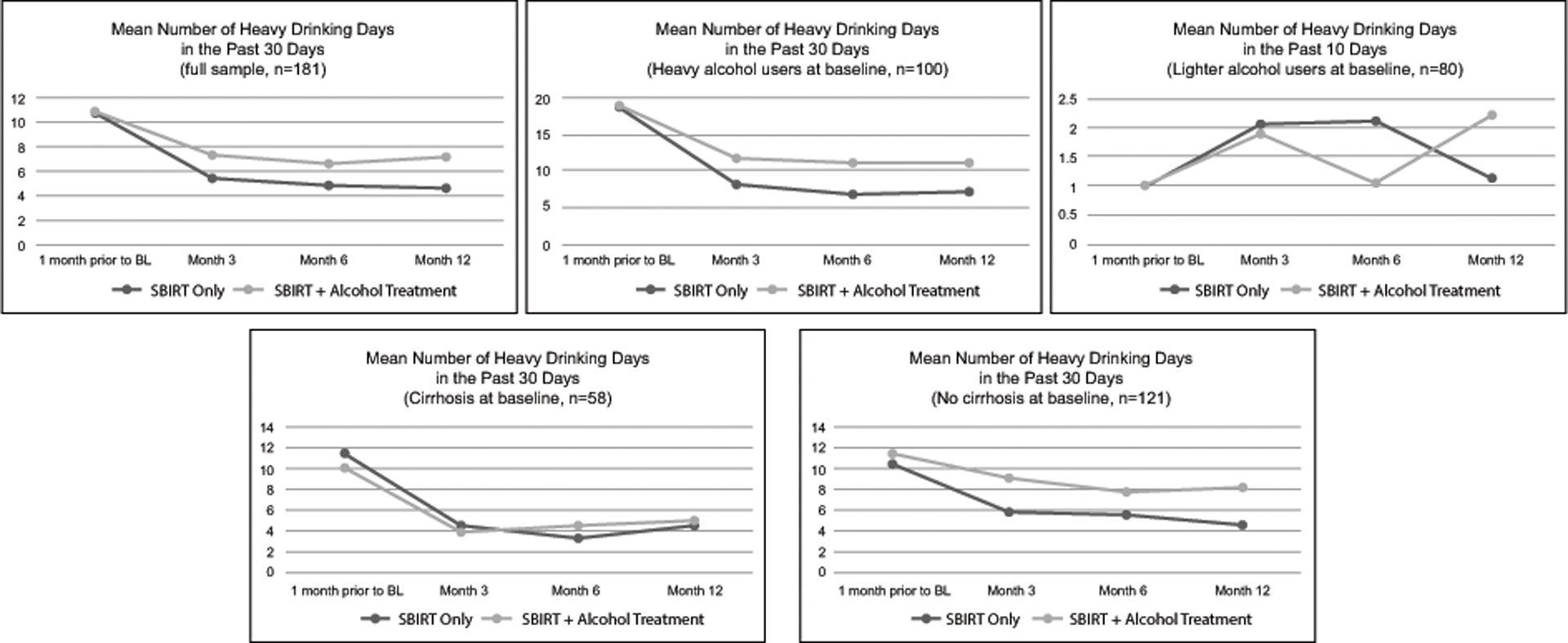

Figure 2 illustrates mean numbers of heavy drinking days at baseline and in months 3, 6 and 12 for the full sample and among participant subgroups. Among all participants, both treatment arms improved over time by similar amounts (1.8 heavy drinking days in the past month, 95% CI: −1.5, 5.1, p=0.29 for 6-month intervention effect). Among participants with heavy alcohol use at baseline (binge drinking for 5 or more days during past 30 days; N=99), the SBIRT-only participants improved more than the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment participants from baseline to month 6 (4.2 heavy drinking days in the past month, 95% CI: −0.6, 9.0, p=0.09 without adjustment for multiple comparisons).

Figure 2.

Number of heavy drinking days

Figure 3 illustrates numbers of days abstinent at baseline and in months 3, 6, and 12 months. Significant differences between arms were not found at any follow-up time point versus baseline, for the full sample or among subgroups.

Figure 3:

Number of alcohol abstinence days

Table 5 depicts alcohol therapy and service use for both treatment arms. SBIRT-only participants reported a mean of 8.8 (SD=31.5) alcohol therapy hours over 6 months post-baseline, compared to a mean of 10.1 (SD=14.9) hours of study-provided clinic-based alcohol and non-study alcohol therapies for SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment participants.

Table 5:

All alcohol services utilized by the 181 study participants between baseline and 6 months follow-up, including and beyond the study alcohol treatment offered to participants in the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment arm

| Panel A: Alcohol therapies including the study alcohol treatment (co-located alcohol treatment) and non-study alcohol treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | # sessions, mean (SD), median | # total hours, mean (SD), median | Participation in 4+ sessions, % (n/N) | Participation in 1–3 sessions, % (n/N) | Non-participation, % (n/N) |

| Hep ART study-provided alcohol treatment, individual and group sessions co-located in liver clinics | |||||

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment Arm | 7.2 (7.2), 5 | 7.2 (9.0), 4 | 55.8% (53/95) | 32.6% (31/95) | 11.6% (11/95) |

| Individual sessions | 5.8 (5.2), 4 | 5.0 (4.8), 3.6 | 54.7% (52/95) | 33.7% (32/95) | 11.6% (11/95) |

| Group sessions | 1.4 (3.8), 0 | 2.2 (6.1), 0 | 13.7% (13/95) | 3.2% (3/95) | 83.2% (79/95) |

| Non-Hep ART study alcohol treatment, individual and group sessions* | |||||

| SBIRT Only Arm | 2.8 (8.5), 0 | 8.8 (31.5), 0 | 12.2% (10/82) | 6.1% (5/82) | 81.7% (67/82) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment Arm | 1.3 (5.6), 0 | 2.7 (11.3), 0 | 6.7% (6/90) | 3.3% (3/90) | 90.0% (81/90) |

| Hep ART and non-Hep ART alcohol treatment* | |||||

| SBIRT Only Arm | 2.8 (8.5), 0 | 8.8 (31.5), 0 | 12.2% (10/82) | 6.1% (5/82) | 81.7% (67/82) |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment Arm | 8.7 (9.8), 6.5 | 10.1 (14.9), 4.7 | 60.0% (54/90) | 28.9% (26/90) | 11.1% (10/90) |

| Panel B: Alcohol services other than alcohol treatment | ||

|---|---|---|

| AA, NA, and support groups | Any participation, % (n/N) | # sessions among the participants, mean (SD), median |

| SBIRT Only | 22.0% (18/82) | 27.4 (28.8), 17 |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 23.1% (21/91) | 10.6 (11.2), 6 |

| Residential alcohol treatment | Any participation, % (n/N) | # days among the participants, mean (SD), median |

| SBIRT Only | 2.5% (2/81) | 16.5 (16.3), 16.5 |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 1.1% (1/90) | 7.0 (0.0), 7 |

| Alcohol detox treatment | Any participation, % (n/N) | # days among the participants, mean (SD), median |

| SBIRT Only | 7.4% (6/81) | 4.2 (1.7), 4 |

| SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment | 5.6% (5/90) | 6.6 (3.8), 7 |

Excluding sessions required for receiving medication that keeps participant away from heroine

Notes.

AA = Alcoholics Anonymous

NA = Narcotics Anonymous

Supplemental Table 1 depicts urine-tested substance use outcomes. No significant differences were found over time or between treatment arms.

Discussion

SBIRT and other evidence-based alcohol reduction interventions have been developed and disseminated in various healthcare settings to address harmful alcohol use. However, randomized controlled trials of alcohol interventions delivered in hepatology clinics with patients at risk for liver disease progression have not been conducted (12). Although we hypothesized that participants in the more intensive six-month SBIRT plus integrated alcohol treatment condition would have better alcohol outcomes than patients who received only provider-delivered SBIRT, this randomized controlled trial showed that patients randomized to either intervention had improved alcohol outcomes but with no significant between-group differences.

Although 44% of HCV infected participants achieved alcohol abstinence at six months in our pilot study (14), and 36% percent achieved alcohol abstinence in an integrated care study by Dieperink et al. (29), only 23% achieved this in the SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment arm. Moreover, we had anticipated that 10% of SBIRT-only participants would achieve alcohol abstinence at six months (15) but observed that 21% were abstinent at 6 months. For reasons discussed below, the SBIRT plus intensive alcohol treatment arm under-performed and the provider-delivered SBIRT-only arm out-performed expectations.

Contributing to the lack of between-group differences may have been the absence of a true “treatment as usual” group. Participants in the SBIRT-only arm all received medical provider-delivered brief alcohol counseling and some acted on alcohol treatment referrals. Based on other studies (30), we had not expected many SBIRT-only participants to follow through on alcohol treatment referrals, yet 12% reported participating in four or more, and 6% in one to three, external alcohol counseling sessions. In contrast, 60% of SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment participants reported engaging in four or more alcohol treatment sessions (see Table 5), making the similar outcomes between arms all the more noteworthy. Follow-through on referrals by SBIRT-only participants may have been due to the involvement of research staff in making alcohol treatment referrals or that SBIRT-trained medical providers beginning their patient encounters with an emphasis on alcohol reduction, combined with the patients having HCV, may have effectively motivated follow through. In addition, it is possible that both groups benefited from the study’s data collection components, which included a detailed assessment of alcohol use and drinking motives at baseline as well as at two time points before the final study endpoint. Previous studies have opined that data collection procedures and frequent interactions with research staff can have inadvertent positive effects on study outcomes (31).

This study’s findings suggest implications for integrated alcohol care in liver clinics. Few integrated HCV-alcohol treatment models have been tested in patients with liver disease (32). A systematic literature review found only five behavioral studies targeting alcohol reduction among patients with HCV (33). Published HCV-alcohol integrated treatments have mainly focused on people who inject drugs recruited from needle exchange settings (34), or patients with severe alcohol use disorders (35). Two studies tested integrated care for patients with less severe alcohol use. Although limited by nonrandomized study designs, the findings indicated increased initiation of HCV antiviral therapy and reduced or abstinent alcohol consumption (29, 36). In a retrospective study, in heavy-drinking chronic HCV patients undergoing HCV treatment, SBIRT plus additional thirty-minute cognitive behavioral sessions (average=4.5) with a co-located psychiatric nurse specialist was associated with significant drinking reductions and alcohol abstinence (29). Another study that tested four sessions of motivational enhancement therapy delivered by psychologists to patients with HCV and alcohol use disorder found more days of alcohol abstinence in the treatment group (37). These studies and our pilot study were conducted prior to the current era of widely available DAA treatments for HCV.

Prior to the DAA era, alcohol abstinence was recommended during HCV treatment with interferon regimens due to concerns about lower response rates and increased adverse events with ongoing alcohol use. In contrast, DAA regimens are well-tolerated with high response rates. During our earlier pilot, many payers restricted DAA’s to those with no alcohol use, which may have motivated higher abstinence (38). While alcohol reduction with a goal of abstinence is still recommended to patients with co-existing HCV infection, alcohol use is not considered a contraindication to antiviral therapy. As a result, patients in recent years may be less motivated to decrease their alcohol use. The current study is important in that it shows that patients with current or prior HCV-infection will engage in alcohol treatment when encouraged by liver medical providers, even in the DAA era. Our trial demonstrates the value of integrating alcohol use disorder interventions into hepatitis care and could serve as a model for incorporating other alcohol treatments, including psychosocial, behavioral, and pharmacological treatments, to provide patient-centered holistic approaches to these comorbid diseases. The current study’s findings highlight that liver clinic medical providers’ provision of alcohol screening and discussion is feasible and acceptable to patients; patient-provider discussions about alcohol remain relevant to liver health even after HCV cure.

The current study provides new insights about integrated care in subspecialty clinics. First, at two university-based liver clinics, patients were willing to enroll and engage in clinic-based alcohol treatment. Addiction therapists at all clinics offered telephone therapy, which turned out to be the predominant delivery mode at the public university-based liver clinic. At the VA site, it was more difficult to enroll patients for several possible reasons, including ongoing engagement in alcohol or mental health treatment conveniently offered at the same VA location (although not in the liver clinics specifically). In addition, a larger number of VA HCV-infected patients in care had received DAA therapy by the time we started recruiting in the VA in 2016, leading to fewer patients with HCV attending the clinic. For all sites, it was difficult to recruit eight patients simultaneously to deliver group therapy. Virtual visit options for group therapy should be explored in future research.

This study’s findings further suggest important implications for implementation of SBIRT as part of routine care in liver clinics. Recent recommendations support the use of SBIRT as a model for integrated care of patients with chronic liver disease and substance use and mental health problems (39). Large research projects with substantial funding have effectively implemented SBIRT in medical practices, but the evidence that SBIRT can be implemented in clinics with little external funding remains limited (40).

The current design and findings suggests that medical provider-delivered SBIRT in liver clinics may be feasible and effective, even in liver clinics with little external funding to provide SBIRT. Specifically, we organized a two-hour, annual training for the medical providers in each liver clinic and engaged an SBIRT trainer to provide didactic content and facilitate role plays. We utilized NIAAA-developed handouts for SBIRT that were shared with clinic providers. Beyond training, some clinic resources were necessary to sustain SBIRT. These included the receptionist handing out the AUDIT screener to patients and medical providers engaging in brief alcohol counseling with patients. The referral out for alcohol treatment required 10–20 minutes. Although our study team conducted these referrals, in the absence of research funding and staff, someone in the liver clinic would need to take responsibility for arranging for referral for specialty addiction care. In a word of caution, for patients with alcohol-induced liver disease, more intensive treatments than those studied here may be needed.

This study has several limitations. The study lacked a treatment as usual control group, and substituted an SBIRT-based enhanced treatment as usual intervention. Because both treatment groups improved, and in the absence of a pure treatment as usual control group, it is not possible to tease apart the effects of medical provider attention during study referral or the detailed alcohol assessments during data collection. Similarly, data collection or research staff attention may have served as an alcohol intervention.

In addition, by design we enrolled patients with various alcohol use levels because of its deleterious effect on hepatitis C progression. At baseline, over 30% had less than a severe alcohol use disorder. If a higher percentage had severe alcohol use disorder, it is possible that we would have seen greater differences between treatment arms, given that SBIRT works less well for people with more severe alcohol use (41). Furthermore, the integrated care intervention was not fully implemented as intended. Only one site ever provided group alcohol therapy, which can be a highly effective treatment (42). Also, because of limited space in the liver clinic, one site required participants to cross a street to a nearby but less familiar setting which may have been perceived as being similar to a referral. Furthermore, SBIRT-only participants participated in a similar number of alcohol treatment hours as SBIRT + Alcohol Treatment participants. Researchers of future studies of integrated care in liver clinics may want to introduce accountability or contingency management techniques to improve session compliance. Finally, few VA patients enrolled (n=19). Recruitment from three diverse liver clinics enhances generalizability, which is nevertheless limited by our geographic location in central North Carolina.

In conclusion, the results of this randomized trial indicate that alcohol use outcomes can be improved in liver clinic patients with current or prior HCV when receiving either provider-delivered SBIRT or six months of integrated HCV-alcohol counseling, combined with study enrollment and detailed alcohol use data collection. Future research can better determine the benefits of SBIRT provision to patients with HCV by testing it against a no-enhancement standard of care group. Given the moderate degree of resources required to implement SBIRT, paired with the potential harm of alcohol use for patients with current and prior HCV, liver clinics should consider implementing provider-delivered SBIRT and alcohol treatment referral practices as part of standard of care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the many study interventionists who implemented the study. These include addiction therapists Cathryn Mainville and Hayden Dawes; liver clinic medical providers Janet Jezsik, Elizabeth Goacher, Krista Edelman, Gabe Mansouraty, Dawn Piercy, Nicole Fesel, Ami Patel, Yuval Patel, Ahmad Farooq, Dawn Harrison, Danielle Cardona, Jama Darling, Steve Choi, Kimberly Pollis, Cynthia Moylan, Nancy Shen, Colleen Boatright, Joyce Davis; addiction psychiatrist Roy Stein; and Durham VA Social Work Supervisor for Mental Health Larry Rhodes. We also thank our study interviewers, including Becca Heine, Carla Mena, Courtenay Pierce, and Lavanya Vasudevan; our data managers including Donna Safley and Ceci Chamorro; our data entry team including Blen Biru, Andy Elkins, Lauren Hunt, Caesar Lubangakene, Nneka Molokwu, and Michael West; and Malik Muhammad Sohail for literature review.

Financial Support

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01AA021133-01A1] and supported by the Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH-funded program (5P30 AI064518).

Abbreviations

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- SBIRT

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment

- DAA

direct acting antiviral

- AUDIT

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

- UNC

University of North Carolina

- VA

Veterans Affairs

- EMR

electronic medical record

References

- 1.The Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. The Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(3):161–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thein HH, Yi Q, Dore GJ, Krahn MD. Estimation of stage-specific fibrosis progression rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Hepatology. 2008;48(2):418–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Younossi ZM, Zheng L, Stepanova M, Venkatesan C, Mir HM. Moderate, excessive or heavy alcohol consumption: each is significantly associated with increased mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(7):703–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor AL, Denniston MM, Klevens RM, McKnight-Eily LR, Jiles RB. Association of hepatitis C virus with alcohol use among U.S. adults: NHANES 2003–2010. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(2):206–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. 2019. [Available from: https://www.hcvguidelines.org/.] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2018. J Hepatol. 2018;69(2):461–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(5):843–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change. Second edition ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beich A, Thorsen T, Rollnick S. Screening in brief intervention trials targeting excessive drinkers in general practice: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):536–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bien TH, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a review. Addiction. 1993;88(3):315–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preventive US Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(7):554–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernstein E, Topp D, Shaw E, Girard C, Pressman K, Woolcock E, et al. A preliminary report of knowledge translation: lessons from taking screening and brief intervention techniques from the research setting into regional systems of care. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(11):1225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blount A Integrated primary care: organizing the evidence. Families, Systems & Health. 2003;21(2):121–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proeschold-Bell RJ, Patkar AA, Naggie S, Coward L, Mannelli P, Yao J, et al. An integrated alcohol abuse and medical treatment model for patients with hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(4):1083–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proeschold-Bell RJ, Evon DM, Makarushka C, Wong JB, Datta SK, Yao J, et al. The Hepatitis C-Alcohol Reduction Treatment (Hep ART) intervention: Study protocol of a multi-center randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;72:73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, Dept. of Mental Health and Substance Dependence; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2005. [updated January 2007; cited 2011 May 15]. Available from: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/practitioner/cliniciansguide2005/clinicians_guide.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hester RK, Miller WR. Handbook of alcoholism treatment approaches. Second ed. Boston, MA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck AT, Wright FD, Newman CF. Cocaine abuse In: Freeman A, Dettilio F, eds. Comprehensive Casebook of Cognitive Therapy. New York, NY: Plenum; 1992: 1185–92. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang SJ, Winchell CJ, McCormick CG, Nevius SE, O’Neill RT. Short of complete abstinence: an analysis exploration of multiple drinking episodes in alcoholism treatment trials. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(12):1803–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol Timeline Followback (TFLB) In: Association AP, ed. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000: 477–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Self-report issues in alcohol abuse: state of the art and future directions. Behav Assess. 1990;12(1):77–90. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1–3):163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15.0 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dieperink E, Ho SB, Heit S, Durfee JM, Thuras P, Willenbring ML. Significant reductions in drinking following brief alcohol treatment provided in a hepatitis C clinic. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(2):149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisner C, Mertens J, Parthasarathy S, Moore C, Lu Y. Integrating primary medical care with addiction treatment: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286(14):1715–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCambridge J, Kypri K. Can simply answering research questions change behaviour? Systematic review and meta analyses of brief alcohol intervention trials. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e23748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonner JE, Barritt ASt, Fried MW, Evon DM. Time to rethink antiviral treatment for hepatitis C in patients with coexisting mental health/substance abuse issues. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(6):1469–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doyle JS, Hunt D, Aspinall EJ, Hutchinson SJ, Goldberg DJ, Nguyen T, et al. A systematic review of interventions to reduce alcohol consumption among individuals with chronic HCV infection, P734. J Hepatol. 2014;60(1):S314–S5. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein MD, Charuvastra A, Maksad J, Anderson BJ. A randomized trial of a brief alcohol intervention for needle exchangers (BRAINE). Addiction. 2002;97(6):691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willenbring ML, Olson DH. A randomized trial of integrated outpatient treatment for medically ill alcoholic men. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(16):1946–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knott A, Dieperink E, Willenbring ML, Heit S, Durfee JM, Wingert M, et al. Integrated psychiatric/medical care in a chronic hepatitis C clinic: effect on antiviral treatment evaluation and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2254–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dieperink E, Fuller B, Isenhart C, McMaken K, Lenox R, Pocha C, et al. Efficacy of motivational enhancement therapy on alcohol use disorders in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2014;109(11):1869–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canary LA, Klevens RM, Holmberg SD. Limited access to new hepatitis C virus treatment under state Medicaid programs. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(3):226–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel K, Maguire E, Chartier M, Akpan I, Rogal S. Integrating care for patients with chronic liver disease and mental health and substance use disorders. Federal Practitioner. 2018;35(Suppl 2):S14–S23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hargraves D, White C, Frederick R, Cinibulk M, Peters M, Young A, et al. Implementing SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment) in primary care: lessons learned from a multi-practice evaluation portfolio. Public Health Rev. 2017;38:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glass JE, Hamilton AM, Powell BJ, Perron BE, Brown RT, Ilgen MA. Speciality substance use disorder services following brief alcohol intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction. 2015;110(9):1404–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance Abuse Treatment: Group Therapy, a Treatment Improvement Protocol, TIP 41 HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15–3991 Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.