Abstract

The sobering reality of the COVID-19 pandemic is that it has brought people together at home at a time when we want them apart in the community. This will bring both benefits and challenges. It will affect people differently based upon their age, health status, resilience, family support structures, and socio-economic background. This article will assess the impact in high income countries like Australia, where the initial wave of infection placed the elderly at the greatest risk of death whilst the protective measures of physical distancing, self-isolation, increased awareness of hygiene practices, and school closures with distance learning has had considerable impact on children and families acutely and may have ramifications for years to come.

Keywords: Covid 19, SARS-CoV-2, Social distancing, Isolation, Infection, Psychological trauma, Education

Mitigating the spread of infection with physical distancing

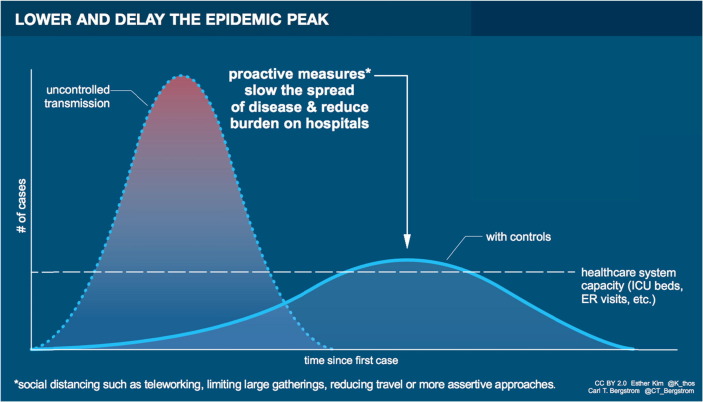

The concept of “flattening the curve” to prevent uncontrolled transmission of infection in a pandemic, slow the spread, and reduce burden on hospitals (Fig. 1 ) was actually learned over a century ago. When US troops returned from World War I they brought with them the Spanish influenza, a devastating pandemic which would kill an estimated 50 million people globally, more than were killed by weapons in both World Wars combined [1]. Nature is the World's greatest terrorist.

Fig. 1.

Lower and delay the epidemic peak: “flattening the curve” (Esther Kim & Carl T Bergstrom, http://ctbergstrom.com/covid19.html).

The response differed in different US cities. Philadelphia's public health director, Wilmer Krusen, made light of the influenza spreading rapidly through the troops and the public, saying the people of Philadelphia could avoid catching influenza by staying warm, keeping their feet dry and their bowels open [2]. Against the advice of his medical experts, Krusen allowed a Liberty Loan parade planned for September 28th, 1918 to go ahead, because it would raise millions of dollars in war bonds. Massed crowds watched troops, scouts and marching bands parade through Philadelphia's streets. Three days later, all Philadelphia's 31 hospitals were full; within a week of the parade 2,600 people died [2].

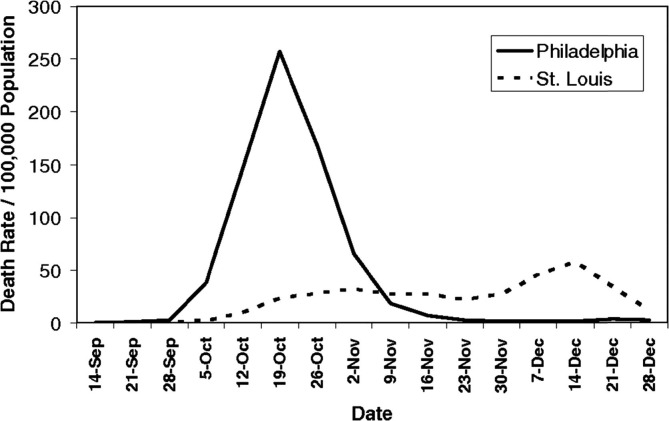

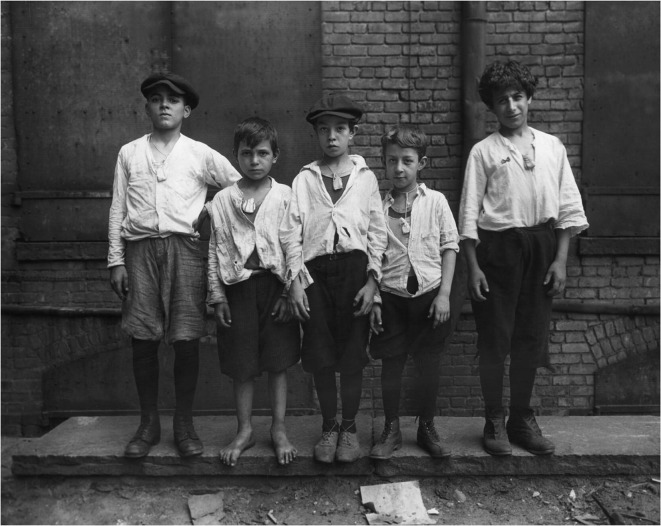

In contrast, despite opposition from tradespeople, the health commissioner of St Louis, Dr Max Starkloff, banned public gatherings, published an editorial telling people to avoid crowds, and shut cinemas and pool halls. St Louis flattened the curve (Fig. 2 ) and saved lives: the mortality in Philadelphia was eight times higher than in St Louis [2]. As we planned for a possible pandemic, public health experts and epidemiologists took notice of the lessons from 1918, emphasizing the need for rapid introduction of measures such as social distancing [3], [4]. How ironic then that the US was one of the countries that reacted latest to the COVID-19 pandemic. We may scoff at the folk remedies desperate people employed a hundred years ago for lack of an effective treatment or vaccine (Fig. 3 ), but are we so much better nowadays, as we hoard unproven and even toxic medicines such as hydroxychloroquine? Pandemics induce panic [5].

Fig. 2.

Epidemic curve of pandemic influenza in 1918: Philadelphia held a parade, St Louis banned public gatherings and “flattened the curve” [2], [3], [4].

Fig. 3.

US boys wear bags of camphor around their necks, thought to protect against influenza, 1918 (derived from Ref. [2]).

The effectiveness of flattening the curve is shown by the figures. In May 2020, Australia has flattened the curve, the US and the UK have yet to do so. By May 9th 2020 Australia (population 25 million) had had 6,914 cases of proven SARS-CoV-2 infection (18 new cases in the previous 24 hours) and a total of 97 deaths. The same day, the US (population 328.2 million) had had 1,321,785 cases of proven SARS-CoV-2 infection (28,369 new cases in the previous 24 hours) and a total of 78,615 deaths (2,239 deaths in the previous 24 hours). That day, the UK (population 66.7 million) had had 206,715 cases of proven SARS-CoV-2 infection (5,514 new cases in the previous 24 hours) and a total of 30,615 deaths (539 deaths in the previous 24 hours). While the observed mortality strongly depends on the extent and nature of testing, the current mortality rate is 5.9% of proven cases in the US, a staggering 14.8% in the UK, but only 1.4% in Australia, a tenth of the UK rate. It has been estimated that, without “social distancing”, by the time 60% of Australians were infected with SARS-CoV-2, which is the estimated proportion needed to achieve herd immunity and cease transmission, there would be 130,000 deaths [6].

Australia introduced various public health measures earlier than the US and the UK, stopping flights from China, quarantining overseas arrivals, testing widely, and tracing and quarantining contacts. These were effective in keeping our numbers of cases down. However, “social distancing” has likely contributed to keeping the numbers of cases and deaths low.

Several authors have commented that we should probably talk of physical distancing rather than social distancing, because of the importance of avoiding social isolation. The figures are not yet available, but it is almost certain that effective distancing and other measures like improved education about hand-washing and hygiene etiquette will result in a fall in non-COVID-19 viral infections and viral-associated conditions in children. Public health measures directed against COVID-19 are likely to result in lower circulation rates of respiratory viruses, so lower admission rates for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza related illness. In addition, episodes of virus-induced wheeze should fall as well. These potential positive benefits may be hard to distinguish from a decrease in asthma presentations related to delay or lack of seeking healthcare because of fears of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 disease. Italian paediatricians described worrying delays in presentation for non-COVID-19 conditions [7]. We must be careful that children with unrelated conditions do not become a secondary casualty of COVID-19.

Numbers of influenza cases are also expected to be lower because of higher rates of influenza immunisation. Health authorities have emphasized that concomitant infection with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza is likely to increase severity, so have stressed the increased need for influenza immunisation in 2020. Indeed, some Australian sporting codes have mandated that players need to be immunised against influenza before being allowed to play. It is interesting that the obvious need for a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 has caused even anti-vaccination proponents like Donald Trump, who has repeatedly claimed that vaccines cause autism, to push for a vaccine against COVID-19 (even if he did initially ask experts if influenza vaccine might cure COVID-19 patients [8]). Increased trust in vaccines may be one positive to come out of COVID-19.

Other possible benefits from “social distancing” include increased use of technology to communicate. Unable to travel to national and international meetings, many of us are “meeting” through video conferencing, something that we know would reduce carbon emissions [9]. Children meanwhile are learning how to learn from home using technology. The interaction between people and technology continues to increase and this could be leveraged to more efficient use of the internet for medical education.

Psychosocial costs of physical distancing

There have been a considerable number of papers on the adverse and potential adverse psychosocial effects of quarantine [where people who may have been exposed to Covid-19 are kept for 14 days until they can be cleared the risk of developing the infection themselves] and the social isolation [state of complete of near complete lack of contact between a person and other members of society] associated with COVID-19 [10], [11], [12]. Sustained time between parents and children may be advantageous where worries about income, job security and domestic violence do not predominate. Some will have found a positive experience with more time and the lack of competing activities compressed into the end-of-the-day time. Contact with extended problematic family members may decrease and the safety of online contact makes many family contact arrangements with children of separated, divorced and combatively conflicted families less fraught.

The ability to make physical isolation not descend into social isolation has been key to reducing the psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on the Australian population. The emphasis on exercise, maintenance of non-COVID related health, people keeping in contact and maintaining essential services have provided the maintenance of social fabric. The UK seems to have managed to increase social isolation, especially of the elderly, without always achieving physical isolation and preventing community transmission. The young and the elderly suffer most in any tear in the social fabric.

In any case, the psychological effects are likely to be mixed, may be short or long term, or within acute on previously chronic disadvantaged backgrounds. All of these factors represent short term trends and vary greatly from region to region, even in the same country. However, there are two longer term concerns, that represent ongoing threats to young people.

The first is a specific physical threat caused by the thromboembolic nature of Covid-19 leading to the development of inflammation of the small vessels of the brain – endothelialitis – which may increase the likelihood of anxiety, depression, psychosis and other neuropsychiatric disorders in the same way that the influenza pandemic did in the early 20th century [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. The spectrum of inflammatory casualty varied from frank neurological signs to mixed neurology and psychiatry and to psychiatry only. These acute and chronic encephalidites are already well documented with other conditions [21], [22], [23]. It remains to be seen what the specific distribution of ACE-2 receptors in endothelial cells in the central nervous system during different age epochs [24], [25], [26] and different ethnic cohorts yields. It is possible that a number of previously paediatric idiopathic, multi-system inflammatory disorders such as Kawasaki disease may be re-examined through a COVID-19 lens with benefit.

The other longer-term psychosocial concern is a philosophical one, which was already in evidence before the pandemic, involving a loss of confidence by young people in the competence of older generations to manage the survival and good order of society. Concerns about climate change, deepening international inequality of wealth and health, wide scale corruption, even in so-called developed countries, and the indifference to the good of society in favour of the good of the economy, all represent for many young people examples of existing generations’ incompetence, greed and callous indifference to the needs of disadvantaged casualties. The ‘guardianship’ or ‘parental’ role of older generations for younger ones in this view is seriously questioned, and in some cases rejected.

Parenting or guardianship capacity usually involves three basic elements:

-

1.

Commitment of parents to children involving tangible sacrifice of time and effort, if necessary to their own disadvantage, on behalf of their children and their futures. Mere verbal affirmations of love and commitment for children are anaemic pretences.

-

2.

Protection from harm, present and future, emotionally and physically. COVID-19 has demonstrated to young people in some countries that those in parental roles in some countries are incompetent, tell lies and are corrupt. In other countries young people have seen older generations deal with the problem effectively, communicate truthfully and manage equitably. Young people have been asked to behave responsibly to protect older people. The implication that older people should behave responsibly to protect young people in the future is clear.

-

3.

Provision of need, present and future, physically and emotionally.

The issue of competence extends beyond the protection from harm and asks what sort of society do we need or want? Young people are now aware of what could be, of what is in different countries in the world. Reasonable and affordable housing, health care, education together with the building of safe communities all contribute to sense of ‘felt security’ [27], [28]. Their empathic reach extends beyond their own community, country and ethnic groups as result of online information and communication. The response to the COVID-19 Pandemic will leave some young people deeply disaffected based on the indifference or incompetence of the older generations they observe. On the other hand, countries such as New Zealand, Taiwan, Germany, Singapore will have communicated a deep commitment to their young people, the capacity to prevent harm and to provide need both now and in the future.

Societal costs of physical distancing

Delays in declaring the COVID-19 crisis a pandemic by the WHO have been rightly criticised [29] and have led to the need for all countries to mitigate the spread of the disease, the centrepiece of which is social or physical distancing. Successful social isolation comes at an enormous, if not incalculable cost. Unemployment or under-employment result in financial hardship with loss of ability to pay for food and housing, increased homelessness, disruption of education, reduced focus on medical and dental health, higher rates of parental alcoholism, domestic violence and suicide [30], [31]. These impacts are often delayed after the acute health crisis passes, the consequences linger for years and impact indirectly on morbidity and mortality.

Economics

The cost of COVID-19 to governments will be enormous. It has been estimated that since World War II, the average economic recession results in an increase in unemployment of around 2% [32]. In a wealthy country like Australia, the cost of supporting the population for the first three months of lockdown has been estimated at $AUS4 billion per week and the unemployment rate has risen by 1% to 6.2% in 4 weeks after commencing the lockdown. However, the true impact of the social isolation is better reflected by the rate of “underemployment”, which currently approaches 20% [abs.gov.au accessed 20th May 2020].

Loss of household income leads to reduced discretionary spending, risking adequate nutrition for children, inability to meet commitments to rental or mortgage payments, jeopardising for some their living arrangements and leading to more homelessness and pressure on overcrowded emergency accommodation resources [33]. Overcrowding leads to greater risks of cross-infection and illness, dislocation from community and family supports and psychosocial stressors affecting mood and resilience [34]. In the end, loss of financial independence leads to increased mental health problems with depression and suicide, alcoholism, domestic violence and a spiral of emotional decay that can ruin families and cost lives.

Liberties

A direct consequence of social isolation is the loss of liberties. Freedom of movement within one’s local area, socialising with friends and family, ability to exercise where and when you choose are confronting for many. Especially for children, the emotional joy of visiting relatives, particularly the elderly such as grandparents, was abruptly removed. Intergenerational conversations and interactions are the cornerstone of many cultures and their curtailment, even for months, compromises the social capital one sees emanating from these life experiences. The loss of social interactions, so important for children and parents is emotionally draining. Children enrich their creativity from free play [35] but parents also benefit from sharing experiences with other adults, discussing common issues and seeking validation when unsure in parenting matters [36]. The inability for parents to have social time with other adults at their homes, at restaurants, at organised sport or enjoying cultural performances in music and theatre may have significant impacts upon their mood and resilience, with repercussions on family functioning and wellbeing of children [37].

Education

Educational outcomes are likely to be a long-term casualty of COVID-19 restrictions. School closures are an expensive but effective way of slowing the peak of a pandemic [38]. However, other measures such as rapid contact tracing and case isolation, surveillance networks and personal protective equipment for healthcare workers are much more cost-efficient [39]. Indeed, the closure of schools has probably been more effective in protecting teachers than the students themselves, as children aged <10 years comprise <1% of cases of COVID-19, similar to the proportion for SARS and MERS [40] and do not appear to be the “super-spreaders” as seen in influenza epidemics [41]. Remote learning, developed with some haste, has at best provided a temporary bridge to effective learning, as many parents would attest. The consequences of the inconsistent educational structures during remote learning will be watched with interest in the years to come. The impact could have be measured with the nationwide Australian annual “NAPLAN” testing of literacy and numeracy for children in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9. Interestingly, the Federal Government has announced its decision [June 1st, 2020, www.nap.edu.au] to cancel the “NAPLAN” exam this year, which could be seen as politically adept but an opportunity missed to inform about the objective educational outcomes of transient enforced distance education.

Medical review

The price of isolation and a sense of societal obligation to assist may inadvertently include reluctance to bring unwell children for medical assessment where the risks of medical review in the community or hospital can be over-emphasised leading to late diagnoses with very unwell children [42]. The much-heralded substitute for face to face clinical consultations has been the use of web-based platforms or telephone consultations, but whilst helpful for routine follow-up consultations such as stable asthma, they do have significant limitations for new or challenging diagnostic cases as they lack the ability for physical examination. Moreover, the ability to readily access routine investigations such as spirometry or polysomnography has also been lost with the concerns about infection risk, albeit mainly extrapolated from valid concerns in the care of adults rather than children.

Fear juxtaposed with risk

Another consequence of social isolation is a greater reliance on social and electronic media for information which may fuel anxiety, adversely influence daily living and lead to a form of post-traumatic stress disorder [43]. For children and parents alike, a culture of fear may evolve from communication overreach: the graphic images presented on social media, news feeds and on television; at times in situations which may misrepresent the risk. This may manifest with disproportionate anxiety with an impact on rational choices for unnecessarily prolonging isolation for relatively mild health conditions, returning children to schooling, presenting for medical care and engaging in social contact with extended families and friends as restrictions are cautiously lifted. It becomes a fine balance between mitigating risk and civil liberties [44]. It is true that heightened mental health concerns linger for some time after traumatic global events [12]. The ability to provide reassurance for the community will be as challenging as garnering the war-time levels of co-operation that have been evident in the responses of communities around the world, especially from those most severely traumatised in China, Italy, England, Spain, Brazil, Russia and America. This is juxtaposed with vastly milder courses to date, such as in Australia and New Zealand, but where there have been similarly motivated populations rallying to prevent the threat of COVID-19 illness overwhelming the health care resource. A key responsibility for political leaders will be to maintain the support of their communities as we patiently await the promise of a vaccine. For parents, the ability to provide love, understanding, reassurance and demonstrate resilience for children is important at times of crisis.

Societal benefits of physical distancing

Lessons can be learnt from pandemics and following the H1NI pandemic of 2009, it was suggested that communication and co-operation problems will challenge the WHO and political leaders with the next pandemic [45]. Prescient! However, science has fared better with the march of technology enabling scientists to unravel the genetic code of SARS-Cov-2, develop antibody tests and commence work on developing a vaccine within weeks of the first recognised cluster of cases [46]. Such rapidity of response would have been thought impossible twenty years ago.

Technology literacy

Importantly, the basic technology literacy has improved across the age spectrum. Parents have had to work from home, using platforms for work conferencing calls and had to do their own work within makeshift spaces, often shared with children learning from home. This has ramifications for flexibility in attendance in centralised workplaces such as city office towers and reduced peak hour transport demands as working hours may be reconfigured around family needs [47]. Whilst disruptive and imperfect, it appears to have been achievable for many people and so can provide the fundamentals for a more flexible attitude to work based on productivity rather than presenteeism.

Work and lifestyle

It is possible there will be some re-evaluation of the impact of work on lifestyle. The pace of work for many may be altered by the experience of social isolation, resulting in a recalibration of financial needs with emotional wellbeing [48]. This may be reflected for some with a re-prioritisation of the importance of family contact, especially with older relatives. The counsel of those with much life experience is often under-appreciated by younger people until it is removed.

Appreciation of friendships

Similarly, the central role of friends in our lives cannot be underestimated. This is true at any age, but better understood when relationships are changed by distance and the lack of personal touch. Simple gestures that we take for granted like a hug or a handshake often mean as much as the information imparted in a conversation. Whilst economic realities are emphasised by governments, for many it is the excitement of communal gatherings, for children playing in an outdoor park, people gathering for picnics, community prayer, people playing sport or watching their children participating in sport, and the sharing of meals at family gatherings or in restaurants that galvanise communities after the restrictions of the lockdown.

Telehealth

For doctors a legacy of the pandemic will likely be a re-shaping of medical consultations. Healthcare workers have used telehealth for children and families with some success for time, especially in the fields of allied health, radiology, psychiatry and retrieval medicine [49]. It is by no means a panacea for all health interactions as the inability for detailed physical examination risks a greater potential for misdiagnosis in previously unseen patients [49]. The reality is that whether living close by or remotely, for follow-up consultations telehealth will be part of the picture in future. Parents and their children, particularly those more self-conscious with behavioural problems or body image issues, may feel more comfortable communicating from the security of their homes. This will save time, the expense and inconvenience of travel for patients and families, result in less missed work for parents and possibly be more cost efficient for doctors who may see more patients in a shorter time frame, reducing waiting lists and improving the health of their patients. However, there will need to be negotiation with governments over health care funding arrangements as part of the ‘new normal” for medical consultations in many countries.

Educational aims:

The reader will be able to appreciate:

-

•

Rapid implementation of physical distancing and improved hygiene etiquette has saved likely many thousands of lives.

-

•

The unintended psychosocial traumas of physical distancing may persist for many years but there have been some unforeseen benefits as well.

-

•

Economic consequences will be severe but likely dwarfed by the intergenerational scepticism of international leadership and co-operation in response to the Pandemic.

Directions for future research

-

•

To assess the impact of physical distancing, hand hygiene and telehealth on the broader health care burden of people with chronic illnesses.

-

•

To assess the long-term impact of physical distancing and social isolation in response to Covid 19 on mental health for vulnerable groups within society.

-

•

To evaluate the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions, including physical distancing, school closures, and personal protective equipment, when responding to pandemics to prepare countries for efficient and early public and health care interventions in the future.

References

- 1.Isaacs D. HarperCollins; Sydney: 2019. Defeating the ministers of death: the compelling history of vaccination. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roos D. How U.S. cities tried to halt the spread of the 1918 Spanish flu. History Stories, March 27th 2020. Link: https://www.history.com/news/spanish-flu-pandemic-response-cities (accessed May 9th, 2020).

- 3.Hatchett R.J., Mecher C.E., Lipsitch M. Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic. PNAS. 2007;104:7582–7587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610941104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bootsma M.C.J., Ferguson N.M. The effect of public health measures on the 1918 influenza pandemic in U.S. cities. PNAS. 2007;104:7588–7593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611071104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaacs D., Britton P., Preisz A. Ethical reflections on the COVID-19 pandemic: the epidemiology of panic. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;14 doi: 10.1111/jpc.14882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blakely T, Wilson N. The maths and ethics of minimising COVID-19 deaths. Health & Medicine, The University of Melbourne, 23rd March 2020. Link: https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/the-maths-and-ethics-of-minimising-covid-19-deaths (accessed May 9th, 2020).

- 7.Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Appicelli A, Marchetti F, Cardinale F, Trobia G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. Published Online April 9, 2020 10.1016/+S2352-4642(20)30108-5 (accessed May 9th, 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Duncan C. Trump suggests using flu vaccine on coronavirus and is instantly corrected by health experts. The Independent, March 2020. Link: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/trump-coronavirus-flu-vaccine-us-pandemic-meeting-leonard-schleifer-a9371286.html?utm_source=reddit.com (accessed May 9th, 2020).

- 9.Isaacs D. Climate change: whose responsibility? J Paediatr Child Health. 2019;55:615–616. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kisely K, Warren N, McMahon L, Dalais C, Henry I, Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis BMJ 2020; 369 (Published 05 May 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 2020 April 10 (Epub ahead of print; accessed May 31 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Menninger K.A. Psychoses associated with influenza, I: General data: statistical analysis. JAMA. 1919;72:235–241. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manjunatha N., Math S.B., Kulkarni G.B., Chaturvedi S.K. The neuropsychiatric aspects of influenza/swine flu: a selective review. Indus Psychiatry J. 2011;20(2):83–90. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.102479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morens D.M., Taubenberger J.K., Fauci A.S. The persistent legacy of the 1918 influenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:225–229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotfis K., Williams Roberson S., Wilson J.E., Dabrowski W., Pun B.T., Ely E.W. COVID-19: ICU delirium management during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Crit Care. 2020;24 doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02882-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuckey S.L., Goh T.D., Heffernan T., Rowan D. Hyperintensity in the subarachnoid space on FLAIR MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:913–921. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larvie M, Lev MH, Hess CP. More on Neurologic Features in Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection NEJM Editorial Online May 26, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020; (published online May 6.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Graus F., Titulaer M.J., Balu R., Benseler S. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):391–404. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binks S.N.M., Klein C.J., Waters P., Pittock S.J., Irani S.R. LGI1, CASPR2 and related antibodies: a molecular evolution of the phenotypes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(5):526–534. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-315720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jammoul A., Li Y., Rae-Grant A. Autoantibody-¬mediated encephalitis: Not just paraneoplastic, not just limbic, and not untreatable. Clevel Clin J Med. 2016;83(1):43–53. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.83a.14112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel AB, Verma A. Editorial: Nasal ACE2 Levels and COVID-19 in Children JAMA. Published online May 20, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Bunyavanich S, Do A, Vicencio A. Research letter: nasal gene expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in children and adults JAMA Published online May 20, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Mackay H. Australia; Hachette Sydney: 2019. What makes us tick. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarren-Sweeney Michael. The mental health of children in out-of-home care. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(4):345–349. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32830321fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durrheim DN, Gostin LO, Moodley S. When does a major outbreak become a Public Health Emergency of International Concern? Lancet Infect Dis; published May 19, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30401-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Broman C.L., Hamilton V.L., Hoffman W.S. The impact of unemployment on families. Michigan Family Rev. 1997;2(2) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frasquilho D., de M., Matos, Marques A., Neville F., Gaspar T., Caldas-de-Almeida J.M. Unemployment, parental distress and youth emotional well-being: the moderation roles of parent-youth relationship and financial deprivation. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2015;1–8 doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandes N. Economic effects of coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) on the world economy. Available at SSRN 3557504. 2020 Mar 22.

- 33.Hurd M.D., Rohwedder S. Effects of the financial crisis and great recession on American households. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2010:30. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bubonya M., Cobb-Clark D.A., Wooden M. Job loss and the mental health of spouses and adolescent children. IZA J Labor Econ. 2017;6(1):6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fehr K.K., Russ S.W. Pretend play and creativity in preschool-age children: associations and brief intervention. Psychol Aesth Creat Arts. 2016;10(3):296. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bornstein M.H., Putnick D.L., Suwalsky J.T. Parenting cognitions→ parenting practices→ child adjustment? The standard model. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30(2):399–416. doi: 10.1017/S0954579417000931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armstrong M.I., Birnie-Lefcovitch S., Ungar M.T. Pathways between social support, family well being, quality of parenting, and child resilience: What we know. J Child Fam Stud. 2005;14(2):269–281. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu J.T., Cowling B.J., Lau E.H., Ip D.K., Ho L.M., Tsang T. School closure and mitigation of pandemic (H1N1) 2009, Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(3):538. doi: 10.3201/eid1603.091216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lockhart S.L., Duggan L.V., Wax R.S., Saad S., Grocott H.P. Personal protective equipment (PPE) for both anesthesiologists and other airway managers: principles and practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Anaesth. 2020;23:1. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01673-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelvin A.A., Halperin S. COVID-19 in children: the link in the transmission chain. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30236-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Munro A.P., Faust S.N. Children are not COVID-19 super spreaders: time to go back to school. Arch Dis Child. 2020 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazzerini M., Barbi E., Apicella A., Marchetti F., Cardinale F., Trobia G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolescent Health. 2020;4(5):e10–e11. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dutheil F., Mondillon L., Navel V. PTSD as the second tsunami of the SARS-Cov2 pandemic. Psychol Med. 2020;24:1–6. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Studdert D.M., Hall M.A. Disease control, civil liberties, and mass testing—calibrating restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2007637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fineberg H.V. Pandemic preparedness and response—lessons from the H1N1 influenza of 2009. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1335–1342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petherick A. Developing antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1101–1102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30788-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bryan M.L., Sevilla A. Flexible working in the UK and its impact on couples’ time coordination. Rev Econ Household. 2017;15(4):1415–1437. doi: 10.1007/s11150-017-9389-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Netemeyer R.G., Warmath D., Fernandes D., Lynch J.G., Jr How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. J Consumer Res. 2018;45(1):68–89. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Utidjian L., Abramson E. Pediatric telehealth: opportunities and challenges. Pediatric Clin. 2016;63(2):367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]