Table of Contents

-

1.

Need for digital health during the COVID-19 pandemic 2

-

2.

Monitoring strategies during a pandemic: Here to stay 3

-

3.

Therapy for COVID-19 and potential electrical effects 7

-

4.

The future: Digital medicine catalyzed by the pandemic 9

References 10

1. Need for digital health during the COVID-19 pandemic

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), started in the city of Wuhan in late 2019. Within a few months, the disease spread toward all parts of the world and was declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020. The current health care dilemma worldwide is how to sustain the capacity for quality services not only for those suffering from COVID-19 but also for non-COVID-19 patients, all while protecting physicians, nurses, and other allied health care workers.

The pandemic poses challenges to electrophysiologists at several levels. Hospitalized COVID-19-positive patients may have preexisting arrhythmias, develop new arrhythmias, or be placed at increased arrhythmic risk from therapies for COVID-19. Cardiac arrhythmia incidence in hospitalized patients has been documented in a few published studies, with reported rates of 7.9%1 and 16.7%2 in hospitals in New York City and Wuhan, respectively, and up to 44%2 in patients requiring intensive care. Life-threatening arrhythmias (ventricular tachycardia [VT]/ventricular fibrillation [VF]) can occur in up to 6% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection.3 There have also been several case reports of atrioventricular block in hospitalized patients, which is otherwise rarely described during viral illness.4 , 5 Although the residual left ventricular dysfunction and arrhythmic risk are currently unknown, preliminary pathophysiological,6 histological,7 and imaging8 data suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection holds the potential to induce durable myocardial changes predisposing to arrhythmias or heart failure.

Electrocardiographic monitoring and inpatient monitoring services may become necessary but face the potential hurdles of limited telemetry wards, contamination of equipment and infection in health care personnel, and shortage of personal protective equipment.9 , 10 In parallel, there is a continued responsibility to maintain care of COVID-19-negative patients with arrhythmias. These pressures have led to inventive utilization and adaptation of existing telemedicine technologies as alternative options.

This document discusses how digital health may facilitate electrophysiology practice for patients with arrhythmia, whether hospitalized for COVID-19 or not. The representation of authors from some of the most severely affected countries, such as China, Spain, Italy, and the United States, is a tribute from our worldwide community to those colleagues who have worked on the front lines of the pandemic.

2. Monitoring strategies during a pandemic: Here to stay

In light of the current pandemic, monitoring strategies should focus on selecting high-risk patients in need of close surveillance and using alternative remote recording devices to preserve personal protective equipment and protect health care workers from potential contagious harm.

Inpatient

For inpatient monitoring, telemetry is reasonable when there is concern for clinical deterioration (as may be indicated by acute illness, vital signs, or sinus tachycardia), or in patients with cardiovascular risk factors and/or receiving essential QT-prolonging medications. Telemetry is generally not necessary for persons under investigation without concern for arrhythmias or clinical deterioration and for those not receiving QT-prolonging drug therapy. In situations in which a hospital’s existing telemetry capacity has been exceeded by patient numbers or when conventional telemetry monitoring is not feasible, such as off-site or nontraditional hospital units, mobile devices may be used, for example, mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry (MCT), as an adjunctive approach to support inpatient care.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 The majority of MCT devices can provide continuous arrhythmia monitoring using a single-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and allow for real-time and offline analysis of long-term ECG data. Telemetry can be extended using patch monitoring.16 , 17 Smartphone ECG monitors are wireless and have also been utilized during the current pandemic. Information is limited, however, on how parameters such as QTc measured on a single- (or limited number) lead ECG can reliably substitute for 12-lead ECG information.18 , 19 In 1 study, QT was underestimated by the smartphone single-lead ECG.20

Outpatient

The principles of remote patient management, crossing geographic, social, and cultural barriers, can be extended to outpatient care and are important to maintain continuity of care for non-COVID-19 patients.21, 22, 23 Virtual clinics move far beyond simple telephone contacts by integrating information from photos, videos, mobile heart rhythm and mobile health devices recording ECG, and remote cardiovascular implantable electronic device (CIED) interrogations.24 A variety of platforms have been developed and used specifically to provide telehealth to patients via video teleconferencing25 , 26 (Table 1 ). Most health care centers have expanded use of telemedicine, with some reporting 100% transformation of in-person clinic visits to telemedicine-based visits in order to maintain care for non-COVID-19 patients, thus obviating their need to come to the hospital or clinic. This supplements social distancing measures and reduces the risk of transmission, especially for the older and more vulnerable populations. It also becomes a measure to control intake into emergency rooms and outpatient facilities and to permit rapid access when necessary to subspecialists.

Table 1.

EMR = electronic medical record; HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; PHI = protected health information.

United Kingdom.

Global.

United States.

Europe.

South America—Brazil.

Encrypted, but not specifically a telehealth platform.

Electrophysiology is well placed for virtual consultations. All preobtained data, including ECGs, ambulatory ECG monitoring, cardiac imaging, and coronary angiography can be adequately reviewed electronically. Digital tools such as direct-to-consumer mobile ECG (Table 2 ) and wireless blood pressure devices can be used to further complement the telehealth visit without in-person contact. CIED, wearable/mobile health, and clinical data can be integrated into the clinician workflow.

Table 2.

Examples of remote ECG and heart rate monitoring devices

| Device | Type | CE mark | FDA clearance | Additional features/notes | Website | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld devices | AliveCor KardiaMobile | Wireless | Yes | Yes | FDA cleared for AF (1-lead) and for QTc (6L) for COVID-19 patients on HCQ ± AZM | https://www.alivecor.com/kardiamobile |

| Beurer ME 90 | Wireless 1-lead ECG |

Yes | No | https://www.beurer.com/web/gb/products/medical/ecg-and-pulse-oximeter/mobile-ecg-device/me-90-bluetooth.php | ||

| Cardiac Designs ECG Check | Wireless 1-lead ECG |

Yes | Yes | https://www.cardiacdesigns.com | ||

| CardioComm Solutions HeartCheck CardiBeat and ECG Pen | Wireless 1-lead ECG |

Yes | Yes | https://www.theheartcheck.com | ||

| COALA | Wireless 1-lead ECG |

Yes | Yes | Remote lung auscultation | https://www.coalalife.com | |

| Eko DUO | Wireless 1-lead ECG |

Yes | Yes | Remote cardiac auscultation/ phonocardiogram | https://www.ekohealth.com | |

| Omron Blood Pressure + EKG Monitor | Wireless 1-lead ECG + BP cuff |

No | Yes | United States and Canada only | https://omronhealthcare.com | |

| EKGraph | Wireless 1-lead ECG |

No | Yes | United States | https://sonohealth.org | |

| Mobile cardiac telemetry devices | Qardio QardioCore |

Chest strap 1-lead ECG |

Yes | No | ECG, HR, HRV, RR, activity | https://www.getqardio.com/qardiocore-wearable-ecg-ekg-monitor-iphone |

| BardyDx CAM | Patch 1-lead ECG |

Yes | Yes | Under clinical investigation for QTc monitoring in COVID-19 patients | https://www.bardydx.com | |

| BioTel Heart | Patch 1-lead ECG |

Yes—only for extended Holter | Yes | FDA cleared for QTc monitoring | https://www.myheartmonitor.com/device/mcot-patch | |

| BodyGuardian MINI Family/BodyGuardian MINI PLUS | Wireless Patch: 1-lead ECG/Wired 3-lead ECG |

Yes | Yes | ECG, HR, HRV, RR | https://www.preventicesolutions.com/hcp/body-guardian-mini-family | |

| iRhythm Zio patch/Zio AT | Patch 1-lead ECG |

Yes | Yes | https://www.irhythmtech.com | ||

| InfoBionic MoMe Kardia | Wired 3-lead ECG |

Yes | Yes | Remote lung auscultation | https://infobionic.com | |

| MediBioSense MBS HealthStream, VitalPatch, MCT |

Patch 1-lead ECG |

Yes | Yes | Monitors up to 8 vital signs | https://www.medibiosense.com | |

| MEMO Patch | Patch/watch 1-lead ECG |

No | No | Asia; Korea FDA approved | https://www.huinno.com | |

| MediLynx PocketECG | Wired 3-lead ECG |

Yes | Yes | HRV | https://www.pocketecg.com | |

| RhythMedix RhythmStar | Wired 3-lead ECG |

No | Yes | https://www.rhythmedix.com | ||

| Samsung S-patch Cardio | Patch 1-lead ECG |

Yes | No | Asia; Korea FDA approved | https://www.samsungsds.com/global/en/solutions/off/cardio/cardio.html | |

| Smartwatches | Apple Watch | 1-lead ECG | Yes | Yes | FDA cleared for AF notification | https://www.apple.com/watch |

| Withings Move ECG | 1-lead ECG | Yes | No | Requires Health Mate app for ECG analysis/AF detection | https://www.withings.com/us/en/move-ecg |

AF = atrial fibrillation; AZM = azithromycin; BP = blood pressure; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; ECG = electrocardiogram; FDA = Food & Drug Administration; HCQ = hydroxychloroquine; HR = heart rate; HRV = heart rate variability; RR = respiratory rate.

Additional diagnostic information might be obtained without in-person contact using home enrollment of prescribed ambulatory rhythm monitors. Patch monitors can be mailed to patient homes and easily self-affixed, unlike Holter monitors with cables and electrodes requiring placement by health care workers. In some cases, new or follow-up telehealth visits will require an adjunctive in-person visit to perform a 12-lead ECG, ECG stress test, echocardiogram, or other diagnostic procedures. Occasionally, conventional clinic visits are required to accurately assess the impact of comorbidities or frailty on procedural risk, or to allow comfortable discussion with multiple family members when planning procedures with high risk. Telephone-only visits (ie, without video) may allow for a broader reach due to ease and ubiquitous accessibility as a communication strategy for immediate access for urgent matters.

There are many barriers to implementation, such as inadequate reimbursement, licensing/regulatory and privacy issues, lack of infrastructure, resistance to change, lack of access/poor Internet coverage, restricted financial resources, and limited technical skills (eg, in the elderly patient population). Some telehealth and remote ECG monitoring technologies may be simply unaffordable and/or unavailable, leading to different levels of uptake within communities and across the globe. All stakeholders should collaborate to address these challenges and promote the safe and effective use of digital health during the current pandemic. In recent months, regulations have been eased to permit consults with new patients, issuing prescriptions, and obtaining consents. In that sense, the COVID-19 pandemic may serve as an opportunity to evolve current technologies into indispensable tools for our future cardiological practice.

3. Therapy for COVID-19 and potential electrical effects

No specific cure exists for COVID-19.28, 29, 30 Potential COVID-19 therapies, especially hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, are being investigated in ongoing trials but also have been used off-label in many parts of the world. These may exert QT-prolonging effects31 (Table 3 ) and, since recent observational data have questioned their efficacy, require a careful risk-benefit adjudication.32 Combination therapy (eg, hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin) may have synergistic effects on QT prolongation.33 , 34 In a retrospective cohort study of 1438 COVID-19 patients hospitalized in metropolitan New York (ie, a disease epicenter), cardiac arrest was more frequent in patients who received hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin than in patients who received neither drug.35 The adjusted hazard ratio for in-hospital mortality for treatment with hydroxychloroquine alone was 1.08, for azithromycin alone was 0.56, and for combined hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin was 1.35. However, none of these hazard ratios were statistically significant. The observational design of this study may limit interpretation of these findings. In the absence of clear efficacy data, treatment options should be individualized taking into account their proarrhythmic potential for torsade de pointes, which may be enhanced by concomitant administration of other QT-prolonging drugs (eg, antiarrhythmics, psychotropics, etc).

Table 3.

Effect on QTc and proarrhythmia of experimental pharmacological therapies for COVID-1936

| QTc prolongation | TdP risk | |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroquine37, 38, 39, 40 | Moderate ↑ | Low risk of TdP |

| Hydroxychloroquine41 | Moderate ↑ | Low risk of TdP |

| Azithromycin42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 | Moderate ↑ | Very low risk of TdP |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir37 | Moderate ↑ | Low risk of TdP |

| Tocilizumab49 | Mild ↑ or ↓ | NR |

| Fingolimod | Mild ↑ | NR |

| Remdesivir | NR | NR |

| Interferon alfacon-1 | NR | NR |

| Ribavirin | NR | NR |

| Methylprednisolone | NR | NR |

NR = not reported; TdP = torsade de pointes.

In COVID-19 patients receiving prior antiarrhythmic therapy, there should be a thorough consideration of risk vs benefit before initiating any QT-prolonging COVID-19 therapies, especially considering their unproven value. For instance, although some recent observational studies highlight adverse effects of hydroxychloroquine in treating this infectious disease, its use is likely to persist outside of randomized trials because of its affordability and global availability compared with, for example, remdesivir.35 If one of these drugs is judged to be critical, monitoring should be initiated. If life-threatening arrhythmias (VT/VF) occur, the benefit of antiarrhythmic drugs, notably amiodarone, outweighs the potential harm of hydroxychloroquine or other QT-prolonging drugs targeting COVID-19, and in these cases antiarrhythmic drugs should be prioritized and used as deemed necessary. Most importantly, all modifiable predisposing factors for QTc prolongation (electrolyte disturbances, drug-to-drug interaction) that may enhance arrhythmia susceptibility should be corrected, and the small subset of individuals with an underlying genetic predisposition such as congenital long QT syndrome (in whom QTc-prolonging medications are contraindicated) should be identified. Additionally, caution must be exercised in case of subclinical or manifest myocarditis that may increase the vulnerability to proarrhythmias associated with QT-prolonging drugs.

If drugs that exert a QT-prolonging effect are to be initiated in an inpatient setting, a baseline 12-lead ECG should be acquired. Following review of the QTc, patients can be stratified into low-risk group (QTc of <500 ms or <550 ms in the setting of wide baseline QRS) or high-risk group (baseline QTc of ≥500 ms or ≥550 ms in the setting of wide baseline QRS, or patients who are started on combination therapies), guiding selection of telemetered vs nonmonitored beds.50 Low-risk patients treated with QT-prolonging agents may be monitored using MCT (or another available wearable) with twice-a-day transmission of QTc measurements and any urgent alerts. High-risk patients would require more continuous monitoring and follow-up QTc measurements using telemetry preferably (but if unavailable, other remote monitoring devices). A second QTc assessment via telemetry or other remote devices after 2 doses may be helpful in identifying “QTc reactors”—patients who have an exaggerated response to QT-prolonging agents. An increase in QTc by ≥60 ms or to QTc ≥500 ms on any follow-up QT assessment is considered significant and should prompt a reassessment of risks vs benefits of continuing the drug.

In the outpatient setting, a recent statement from the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) “cautions against use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for COVID-19 outside of the hospital setting or a clinical trial due to risk of heart rhythm problems.” (This does not affect FDA-approved uses for malaria, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis.)51 Exceptions to this practice are acknowledged to occur in some regions, as these drugs have been used outside the United States without regulatory warnings. Under these conditions, or when these drugs are maintained after hospital discharge, consumer mobile ECG devices capable of generating QTc measurements may be used. If the QTc increases significantly, physicians can consider a change or discontinuation of medication via the phone or virtual medical services.

Electrocardiographic monitoring during clinical trials

Several double- and multi-arm blind randomized controlled trials are underway worldwide for COVID-19 outpatients utilizing different medications that may prolong the QT interval.52, 53, 54, 55, 56 These drugs are being tested either alone or in various combinations and are being compared with one another, with differential dosing regimens and/or placebo. These drugs are also being tested for postexposure prophylaxis in high-risk groups.

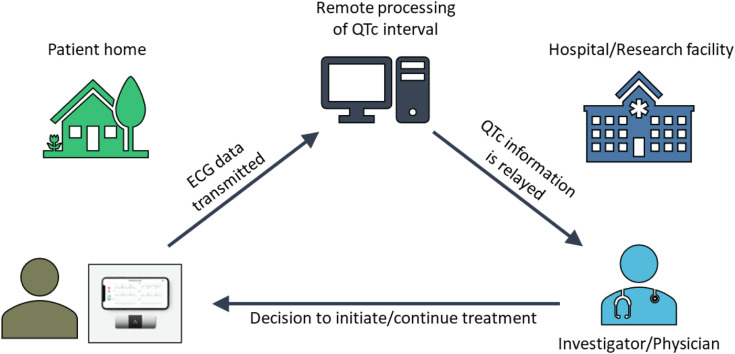

Mobile health using smartphone-based portable ECG devices as QTc monitoring tools is an innovative and economical solution to conduct monitoring in outpatient trials. For instance, in 1 trial evaluating hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin (hydroxychloroquine alone and hydroxychloroquine/azithromycin combination) against a placebo, participants receive remote training to acquire a 6-lead ECG at baseline and then at specified follow-up intervals through the trial period (Figure 1 ). These ECGs are transmitted to a remote QTc monitoring site, where the QTc is assessed and monitored over the treatment period.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) acquisition and transmission using a smartphone-based portable ECG monitor.

4. The future: Digital medicine catalyzed by the pandemic

The COVID-19 public health emergency has forced changes to traditional norms of health care access and delivery across all continents.10 It has accelerated adoption of telemedicine and all aspects of digital health, regarded as a positive development. Today’s new reality will likely define medicine going forward. Many monitoring and diagnostic testing aspects of both inpatient and outpatient care will be increasingly served by digital medicine tools.

The need for contactless monitoring for inpatients triaged to intensive care unit, telemetry, or nonconventional environments, as well as for outpatients needing continued management, has triggered novel implementation of digital health monitoring tools. Some centers have created algorithms based on predictive analytics of electronic medical record (EMR) data. Centralized monitoring or mobile continuous monitoring has improved patient outcomes, reduced manpower needs, and is being utilized more commonly.57 The use of wearables such as watches, smartphones, and smart beds (with elimination of cables and skin electrodes) for in-hospital telemetry is a novel approach. This type of wireless monitoring may be continued after discharge, permitting prolonged surveillance of rhythm and other physiological parameters.12 Bracelet technologies may transmit multiple parameters (eg, heart rate, sleep, oxygen desaturation index, and blood pressure) via a smartphone link to centralized hubs. These technologies provide a solution for intensive monitoring extending beyond the hospital environment.

Outpatient management has been revolutionized since the start of the pandemic. Social distancing measures and restricted clinic access have driven the rapid adoption of telehealth mechanisms to continue management of non-COVID-19 patients. Virtual visits that have been used for decades to reach isolated communities,58 but less commonly utilized in advanced health systems, have now become the mainstay of ambulatory care across all subspecialties. The initial experience appears to have been positive for both patients and caregivers. Heart rhythm professionals are fortunate to have a choice of wireless technologies to relay monitored information to maintain connection.12 Wearable and smartphone-based devices allow convenient real-time monitoring for arrhythmias on a long-term basis due to the comfort associated with their small size and ease of use while reducing patient and health care worker exposure. Remote CIED monitoring has existed for decades.24 It is strongly endorsed by professional societies, but in practice only a fraction of its diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities has been utilized—until now.59 Since the start of the pandemic, utilization of wireless communication with CIEDs has grown exponentially, permanently altering the future of device follow-up. Patient outcomes may be improved with intensive device-based monitoring compared with traditional in-clinic evaluations at regular intervals.60 Recent data indicate that in-person CIED evaluation can be extended safely to at least biennially when daily digital connectivity is maintained.61 Remote monitoring has the potential advantage of detecting and alerting caregivers (and in the future—patients directly) about important parameter changes, enabling earlier patient hospitalization, even during a presymptomatic phase.62

Connectivity permits longitudinal follow-up, with advantages ranging from individual disease management to assessment of the penetration of recommended therapies into communities.60 , 63 The ability for CIED remote monitoring data to be streamed to or accessed by multiple providers can facilitate communication and cooperative treatment and should be encouraged. This will require approval by patients, regulators, and manufacturers. Lessons learned from implantable devices can be applied widely in telemedicine. Regulatory bodies have been responsive, for example, approving smartphone-based QT interval measurement and telehealth services across state lines in the United States. The pandemic experience should serve as an impetus to expedite the resolution of persistent challenges, such as validation of digital technologies, infrastructure for data management (and mechanism for relay to patients and caregivers), interoperability with EMR, application of predictive analytics, cybersecurity (and with it the capability for limited forms of remote CIED programming), and reimbursement.64, 65, 66

In summary, the crisis precipitated by the pandemic has catalyzed the adoption of remote patient management across many specialties and for heart rhythm professionals, in particular. This practice is here to stay—it will persist even if other less arrhythmogenic treatment strategies evolve for COVID-19 and after the pandemic has passed. This is an opportunity to embed and grow remote services in everyday medical practice worldwide.

Footnotes

Developed in partnership with and endorsed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), and the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS).

For copies of this document, please contact the Elsevier Inc. Reprint Department (reprints@elsevier.com). Permissions: Multiple copies, modification, alteration, enhancement, and/or distribution of this document are not permitted without the express permission of the Heart Rhythm Society. Instructions for obtaining permission are located at https://www.elsevier.com/about/our-business/policies/copyright/permissions.

This article has been copublished in Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, EP Europace, the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the Journal of Arrhythmia, and Heart Rhythm. These articles are identical except for minor stylistic and spelling differences in keeping with each journal’s style. Correspondence: Heart Rhythm Society, 1325 G St NW, Suite 400, Washington, DC 20005. E-mail address: clinicaldocs@hrsonline.org.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Author disclosure table

| Writing group member | Employment | Honoraria/speaking/consulting | Speakers’ bureau | Research∗ | Fellowship support∗ | Ownership/partnership/principal/majority stockholder | Stock or stock options | Intellectual property/royalties | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Niraj Varma, MA, MD, PhD, FACC, FRCP (Chair) | Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio | 1: BIOTRONIK; 1: EP Solutions; 1: Medtronic; 1: MicroPort | None | 1: Boston Scientific; 2: Abbott |

None | None | None | None | None |

| Nassir F. Marrouche, MD, FHRS (Vice-Chair) | Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana | 0: Biosense Webster; 0: BIOTRONIK; 0: Cardiac Design; 0: Medtronic; 1: Preventice |

None | 0: Abbott; 0: Boston Scientific; 0: GE Healthcare; 5: Biosense Webster |

None | None | None | None | None |

| Luis Aguinaga, MD, MBA, PhD, FESC, FACC | Centro Privado de Cardiología, Tucuman, Argentina | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Christine M. Albert, MD, MPH, FHRS, FACC | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California | 1: Roche Diagnostics | None | 5: Abbott; 5: NIH; 5: Roche Diagnostics | None | None | None | None | None |

| Elena Arbelo, MD, MSci, PhD | Arrhythmia Section, Cardiology Department, Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Institut d’Investigacións Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain | 1: Biosense Webster | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Jong-Il Choi, MD, PhD, MHS | Korea University Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Mina K. Chung, MD, FHRS, FACC | Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio | 2: ABIM | None | 5: AHA; 5: NIH | None | None | None | 1: Elsevier; 1: UpToDate | 0: ACC (EP Section Leadership Council member); 0: AHA (Chair, ECG & Arrhythmias Committee; Member, Clinical Cardiology Leadership Committee; Member, Committee on Scientific Sessions Programming); 0: Amarin (Data monitoring committee member); 0: BIOTRONIK (EPIC Alliance steering committee member); 2: AHA (Associate Editor, Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology) |

| Giulio Conte, MD, PhD | Cardiocentro, Lugano, Switzerland | None | None | 5: Boston Scientific; 5: Swiss National Science Foundation | None | None | None | None | None |

| Lilas Dagher, MD | Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Laurence M. Epstein, MD, FACC | Northwell Health, North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, New York | 1: Abbott; 2: Medtronic; 2: Spectranetics Corporation |

None | None | None | None | None | None | 2: Boston Scientific (Clinical Events Committee) |

| Hamid Ghanbari, MD, FACC | University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan | 2: Preventice | None | 1: BIOTRONIK; 1: Boston Scientific; 1: Medtronic; 1: Toyota | None | None | None | None | 1: Preventice (Travel/Entertainment) |

| Janet K. Han, MD, FHRS, FACC | VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California | 1: Abbott; 1: Medtronic | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Hein Heidbuchel, MD, PhD, FESC, FEHRA | Antwerp University and University Hospital, Antwerp, Belgium | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| He Huang, MD, FACC, FESC, FEHRA | Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Dhanunjaya R. Lakkireddy, MD, FHRS, FACC | Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute and Research Foundation, Overland Park, Kansas | 1: BIOTRONIK; 2: Abbott |

1: Abiomed; 1: Biosense Webster; 1: Boston Scientific; 2: Janssen |

None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Tachapong Ngarmukos, MD, FAPHRS, FACC | Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand | 1: Abbott; 1: Bayer; 1: Biosense Webster; 1: BIOTRONIK; 1: Boehringer Ingelheim; 1: Boston Scientific; 1: Daiichi Sankyo; 1: Medtronic; 1: Pfizer |

None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Andrea M. Russo, MD, FHRS, FACC | Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, New Jersey | None | None | 1: MediLynx; 2: Boehringer Ingelheim; 2: Boston Scientific |

None | None | None | 1: UpToDate | 0: ABIM (Member, ABIM Cardiovascular Board); 0: Apple Inc. (Steering Committee Apple Heart Study); 0: Boston Scientific (Steering Committee, Research) |

| Eduardo B. Saad, MD, PhD, FHRS, FESC | Hospital Pró-Cardíaco, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | 1: Biosense Webster | None | None | None | None | None | None | 1: Abbott (Travel/Entertainment) |

| Luis C. Saenz Morales, MD | CardioInfantil Foundation, Cardiac Institute, Bogota, Colombia | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Kristin E. Sandau, PhD, RN | Bethel University, St. Paul, Minnesota | 1: Japanese Association of Cardiovascular Nursing | None | None | None | None | None | None | 1: Patient Safety Authority |

| Arun Raghav M. Sridhar, MD, MPH, FACC | University of Washington, Seattle, Washington | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Eric C. Stecker, MD, MPH, FACC | Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon | None | None | 4: AHA | None | None | None | None | None |

| Paul D. Varosy, MD, FHRS, FACC | VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System and University of Colorado, Aurora, Colorado | None | None | 4: NIH | None | None | None | None | 0: ACC (Committee Chair); 0: AHA (Committee Member); 0: NCDR (Committee Chair/Member) |

Number value: 0 = $0; 1 = ≤$10,000; 2 = >$10,000 to ≤$25,000; 3 = >$25,000 to ≤$50,000; 4 = >$50,000 to ≤$100,000; 5 = >$100,000.

ABIM = American Board of Internal Medicine; ACC = American College of Cardiology; AHA = American Heart Association; NCDR = National Cardiovascular Data Registry; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

Research and fellowship support are classed as programmatic support. Sources of programmatic support are disclosed but are not regarded as a relevant relationship with industry for writing group members or reviewers.

References

- 1.Goyal P., Choi J.J., Pinheiro L.C., et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2372–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo T., Fan Y., Chen M., et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:811–818. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azarkish M., Laleh Far V., Eslami M., Mollazadeh R. Transient complete heart block in a patient with critical COVID-19. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2131. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noll A, William A, Varma N. A young woman presenting with a viral prodrome, palpitations, dizziness, and heart block. JAMA Cardiol. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kochi A.N., Tagliari A.P., Forleo G.B., Fassini G.M., Tondo C. Cardiac and arrhythmic complications in patients with COVID-19. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020;31:1003–1008. doi: 10.1111/jce.14479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao X.H., Li T.Y., He Z.C., et al. A pathological report of three COVID-19 cases by minimal invasive autopsies [in Chinese] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:411–417. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200312-00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inciardi R.M., Lupi L., Zaccone G., et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:819–824. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sapp J.L., Alqarawi W., MacIntyre C.J., et al. Guidance on minimizing risk of drug-induced ventricular arrhythmia during treatment of COVID-19: a statement from the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:948–951. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Udwadia Z.F., Raju R.S. How to protect the protectors: 10 lessons to learn for doctors fighting the COVID-19 coronavirus. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020;76:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabriels J., Saleh M., Chang D., Epstein L.M. Inpatient use of mobile continuous telemetry for COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2020;6:241–243. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinberg J.S., Varma N., Cygankiewicz I., et al. 2017 ISHNE-HRS expert consensus statement on ambulatory ECG and external cardiac monitoring/telemetry. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:e55–e96. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garabelli P., Stavrakis S., Albert M., et al. Comparison of QT interval readings in normal sinus rhythm between a smartphone heart monitor and a 12-lead ECG for healthy volunteers and inpatients receiving sotalol or dofetilide. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:827–832. doi: 10.1111/jce.12976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castelletti S., Dagradi F., Goulene K., et al. A wearable remote monitoring system for the identification of subjects with a prolonged QT interval or at risk for drug-induced long QT syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2018;266:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.03.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gropler M.R.F., Dalal A.S., Van Hare G.F., Silva J.N.A. Can smartphone wireless ECGs be used to accurately assess ECG intervals in pediatrics? A comparison of mobile health monitoring to standard 12-lead ECG. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Food & Drug Administration VitalConnect, Inc. VitalPatch: letter of authorization (April 26, 2020) https://www.fda.gov/media/137397/download Available from.

- 17.VitalConnect. COVID-19. https://vitalconnect.com/covid-19-remote-patient-monitoring Available from.

- 18.Rimmer L.K., Rimmer J.D. Comparison of 2 methods of measuring the QT interval. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7:346–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rimmer L.K. Bedside monitoring of the QT interval. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7:183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koltowski L, Balsam P, Glłowczynska R, et al. Kardia Mobile applicability in clinical practice: a comparison of Kardia Mobile and standard 12-lead electrocardiogram records in 100 consecutive patients of a tertiary cardiovascular care center [published online ahead of print January 15, 2019]. Cardiol J. 10.5603/CJ.a2019.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Ohannessian R. Telemedicine: potential applications in epidemic situations. Eur Res Telemed. 2015;4:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollander J.E., Carr B.G. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S., Yang L., Zhang C., et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varma N., Ricci R.P. Telemedicine and cardiac implants: what is the benefit? Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1885–1895. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NHSX. Information governance. https://www.nhsx.nhs.uk/covid-19-response/data-and-information-governance/information-governance Available from.

- 26.NHS Digital Approved video consultation systems. https://digital.nhs.uk/services/future-gp-it-systems-and-services/approved-econsultation-systems Available from.

- 27.National Health Service Procurement of pre-approved suppliers of online and video consultation systems for GP practices to support COVID-19. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/C0079-Suppliers-of-online-and-video-consultations.pdf Available from.

- 28.Grein J., Ohmagari N., Shin D., et al. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2327–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Society of Cardiology ESC guidance for the diagnosis and management of CV disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.escardio.org/Education/COVID-19-and-Cardiology/ESC-COVID-19-Guidance Available from. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- 30.Chen Z., Hu J., Zhang Z., et al. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: results of a randomized clinical trial. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.22.20040758. 2003.2022.20040758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haeusler I.L., Chan X.H.S., Guérin P.J., White N.J. The arrhythmogenic cardiotoxicity of the quinoline and structurally related antimalarial drugs: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2018;16:200. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1188-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geleris J., Sun Y., Platt J., et al. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2411–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chorin E, Wadhwani L, Magnani S, et al. QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes in patients with COVID-19 treated with hydroxychloroquine/azithromycin [published online ahead of print May 11, 2020]. Heart Rhythm. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Saleh M., Gabriels J., Chang D., et al. Effect of chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and azithromycin on the corrected QT interval in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13:e008662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.120.008662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenberg E.S., Dufort E.M., Udo T., et al. Association of treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York state. JAMA. 2020;323:2493–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CredibleMeds COVID-19 experimental therapies and TdP risk. https://www.crediblemeds.org/blog/covid-19-experimental-therapies-and-tdp-risk Available from. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- 37.Vicente J., Zusterzeel R., Johannesen L., et al. Assessment of multi-ion channel block in a phase I randomized study design: results of the CiPA phase I ECG biomarker validation study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;105:943–953. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mzayek F., Deng H., Mather F.J., et al. Randomized dose-ranging controlled trial of AQ-13, a candidate antimalarial, and chloroquine in healthy volunteers. PLoS Clin Trials. 2007;2:e6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0020006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wozniacka A., Cygankiewicz I., Chudzik M., Sysa-Jedrzejowska A., Wranicz J.K. The cardiac safety of chloroquine phosphate treatment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: the influence on arrhythmia, heart rate variability and repolarization parameters. Lupus. 2006;15:521–525. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2345oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teixeira R.A., Martinelli Filho M., Benvenuti L.A., Costa R., Pedrosa A.A., Nishióka S.A. Cardiac damage from chronic use of chloroquine: a case report and review of the literature. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2002;79:85–88. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2002001000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGhie T.K., Harvey P., Su J., Anderson N., Tomlinson G., Touma Z. Electrocardiogram abnormalities related to anti-malarials in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36:545–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang M., Xie M., Li S., et al. Electrophysiologic studies on the risks and potential mechanism underlying the proarrhythmic nature of azithromycin. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2017;17:434–440. doi: 10.1007/s12012-017-9401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi Y., Lim H.S., Chung D., Choi J.G., Yoon D. Risk evaluation of azithromycin-induced QT prolongation in real-world practice. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1574806. doi: 10.1155/2018/1574806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.US Food and Drug Administration ZITHROMAX (azithromycin) for IV infusion only. Highlights of prescribing information. Reference ID: 4051690. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/050733s043lbl.pdf Available from.

- 45.Ray W.A., Murray K.T., Hall K., Arbogast P.G., Stein C.M. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1881–1890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poluzzi E., Raschi E., Motola D., Moretti U., De Ponti F. Antimicrobials and the risk of torsades de pointes: the contribution from data mining of the US FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Drug Saf. 2010;33:303–314. doi: 10.2165/11531850-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng Y.J., Nie X.Y., Chen X.M., et al. The role of macrolide antibiotics in increasing cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2173–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maisch N.M., Kochupurackal J.G., Sin J. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular complications. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27:496–500. doi: 10.1177/0897190013516503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grange S., Schmitt C., Banken L., Kuhn B., Zhang X. Thorough QT/QTc study of tocilizumab after single-dose administration at therapeutic and supratherapeutic doses in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;49:648–655. doi: 10.5414/cp201549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giudicessi J.R., Noseworthy P.A., Friedman P.A., Ackerman M.J. Urgent guidance for navigating and circumventing the QTc-prolonging and torsadogenic potential of possible pharmacotherapies for coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1213–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.US Food & Drug Administration FDA cautions against use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for COVID-19 outside of the hospital setting or a clinical trial due to risk of heart rhythm problems. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-cautions-against-use-hydroxychloroquine-or-chloroquine-covid-19-outside-hospital-setting-or Available from.

- 52.ClinicalTrials.gov COVID-19 clinical trials. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=COVID+19&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist Available from.

- 53.ClinicalTrials.gov Efficacy of novel agents for treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection among high-risk outpatient adults: an adaptive randomized platform trial. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04354428?type=Intr&cond=COVID+19&map_cntry=US&map_state=US%3AWA&draw=2 Available from.

- 54.ClinicalTrials.gov WU 352: open-label, randomized controlled trial of hydroxychloroquine alone or hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin or chloroquine alone or chloroquine plus azithromycin in the treatment of SARS CoV-2 infection. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04341727?type=Intr&cond=COVID+19&map_cntry=US&map_state=US%3AMO&draw=2 Available from.

- 55.ClinicalTrials.gov Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection among adults exposed to coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a blinded, randomized study. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04328961?type=Intr&cond=COVID+19&map_cntry=US&map_state=US%3AWA&draw=2 Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.ClinicalTrials.gov ChemoPROphyLaxIs For covId-19 Infectious Disease (the PROLIFIC Trial) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04352933?type=Intr&cond=COVID+19&draw=2 Available from.

- 57.Cantillon D.J., Loy M., Burkle A., et al. Association between off-site central monitoring using standardized cardiac telemetry and clinical outcomes among non-critically ill patients. JAMA. 2016;316:519–524. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bagchi S. Telemedicine in rural India. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e82. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Slotwiner D., Varma N., Akar J.G., et al. HRS expert consensus statement on remote interrogation and monitoring for cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:e69–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hindricks G., Varma N., Kacet S., et al. Daily remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillators: insights from the pooled patient-level data from three randomised controlled trials (IN-TIME, ECOST, TRUST) Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1749–1755. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watanabe E., Yamazaki F., Goto T., et al. Remote management of pacemaker patients with biennial in-clinic evaluation: continuous home monitoring in the Japanese at-home study: a randomized clinical trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.119.007734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Varma N., Epstein A.E., Irimpen A., Schweikert R., Love C., TRUST Investigators Efficacy and safety of automatic remote monitoring for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator follow-up: The Lumos-T Safely Reduces Routine Office Device Follow-up (TRUST) trial. Circulation. 2010;122:325–332. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.937409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Varma N., Jones P., Wold N., Stein K. How well do results from large randomized clinical trials diffuse into clinical practice? Impact of MADIT-RIT in a large cohort of implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients (ALTITUDE) [abstract] Eur Heart J. 2014;35(Suppl. 1) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saxon L.A., Varma N., Epstein L.M., Ganz L.I., Epstein A.E. Factors influencing the decision to proceed to firmware upgrades to implanted pacemakers for cybersecurity risk mitigation. Circulation. 2018;138:1274–1276. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Slotwiner D.J., Abraham R.L., Al-Khatib S.M., et al. HRS white paper on interoperability of data from cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:e107–e127. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heidbuchel H., Hindricks G., Broadhurst P., et al. EuroEco (European Health Economic Trial on Home Monitoring in ICD Patients): a provider perspective in five European countries on costs and net financial impact of follow-up with or without remote monitoring. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:158–169. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]