Abstract

Background:

Promoting Resilience in Stress Management (PRISM) is a skills-based, early palliative care intervention with demonstrated efficacy in adolescents and young adults with cancer.

Aim:

Utilizing data from a randomized clinical trial of PRISM versus Usual Care, we examined whether response to PRISM differed across key sociodemographic characteristics.

Design:

Adolescents and young adults with cancer completed patient-reported outcome measures of resilience, hope, benefit-finding, quality of life, and distress at enrollment and 6-months. Participants were stratified by: sex, age, race, and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage based on home address (Area Deprivation Index scores with 8-10=most disadvantaged). Differences in the magnitude of effect sizes between stratification subgroups were noted using a conservative cut-off of d>0.5.

Setting/participants:

Participants were 12 to 25 years-old, English-speaking, and receiving cancer-care at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Results.

92 adolescents and young adults (48 PRISM, 44 Usual Care) completed baseline measures. They were 43% female, 73% 12-17 years-old, 64% White, and 24% most disadvantaged. Effect sizes stratified by sex, age, and race were in an expected positive direction and of similar magnitude for the majority of outcomes with some exceptions in magnitude of treatment-effect. Those who lived in less disadvantaged neighborhoods benefited more from PRISM, and those living in most disadvantaged benefited less.

Conclusions.

PRISM demonstrated a positive effect for the majority of outcomes regardless of sex, age, and race. It may not be as helpful for adolescents and young adults living in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Future studies must confirm its generalizability and integrate opportunities for improvement by targeting individual needs.

This trial has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02340884).

Keywords: cancer, oncology, adolescent, young adult, demographic factors, psycho-oncology, randomized clinical trial, resilience, psychosocial factors

BACKGROUND

Adolescents and young adults (12-25 years old) with cancer have unique developmental and psychosocial needs. In addition to coping with their medical illness, adolescents and young adults struggle with normal developmental challenges, life transitions, and decisions regarding independence, education, employment, self-identity, and social, romantic, and family relationships.1-5 Adolescent and young adult cancer survivors experience inferior psychosocial outcomes in comparison to their younger pediatric and older adult counterparts, with significantly higher psychological distress, poorer quality of life, and fewer positive health benefits.6, 7 These impairments translate into medical expenditures and workplace productivity losses.8

A potential target of palliative care interventions is teaching coping skills to bolster psychological well-being and promote resilience resources.9-11 Resilience is defined as the process of harnessing resources to sustain physical and emotional well-being during and after any stressor.12 Resilience interventions have the potential to improve psychosocial and biological disease outcomes, but few have been developed and tested with adolescents and young adults with cancer.13-15 Promoting Resilience in Stress Management (PRISM) is a brief, developmentally appropriate, early palliative care intervention based on traditional cognitive behavioral therapy; PRISM teaches coping skills in the domains of stress management, goal setting, cognitive restructuring (catching negative self-talk, and evaluating the evidence for and against negative cognitions), and benefit finding (finding meaning/benefit from the illness experience).16 In a phase II randomized clinical trial testing the PRISM intervention against psychosocial Usual Care in adolescents and young adults with cancer, PRISM was associated with clinically and statistically significant improvements in patient-reported resilience, hope, benefit-finding, cancer-specific quality of life, and psychological distress.17, 18

In addition to determining efficacy and effectiveness, a research priority in psychosocial intervention research is to assess the external validity of evidence-based interventions when delivered to diverse sociodemographic backgrounds in real world clinical settings.19 The Division 12 Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures, consisting of clinical psychologists in psychology departments, medical schools, and private practice, was created to educate providers, patients, and third party payers on efficacious and effective psychotherapies.20, 21 The Task Force published a report with the objective of identifying and disseminating information on empirically supported psychotherapies; the ultimate goal was to expand the reach of interventions of known efficacy into routine clinical care.20 This oft-cited report has been the target of critical commentary questioning the generalizability of the interventions enumerated by the Task Force as individuals who enroll in psychotherapy intervention studies tend to be female, White, educated, and middle/upper class.22, 23

To explore PRISM’s potential generalizability, we conducted a post-hoc descriptive analysis utilizing data from the phase II PRISM randomized clinical trial. Specifically, we examined whether response to PRISM differed for adolescents and young adults stratified across four key sociodemographic characteristics: sex, age, race, and relative neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage defined via Area Deprivation Index state decile scores using participant home addresses.

METHODS

Design, setting, and participants

Data collection for the phase II, parallel, 1:1 randomized clinical trial17, 18 was conducted between January 2015 and October 2016. Participants ages 18-25 provided written informed consent, and those ages 12-17 provided written assent with parental written consent. The study was approved by the Seattle Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB Protocol #: 15300). English-speaking adolescents and young adults, 12 to 25 years old, were eligible if they had a new cancer diagnosis or progressive, recurrent, or refractory cancer, and were receiving cancer-care at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Recruitment and randomization

Participants were recruited via in-person approaches in inpatient or outpatient clinics. 100 participants were randomized to psychosocial Usual Care alone or Usual Care plus PRISM. Study staff were blinded to randomization assignment, and staff collecting outcomes data remained blinded.

Psychosocial Usual Care

All participants received psychosocial Usual Care. At Seattle Children’s Hospital, this includes an assigned social worker who conducts a comprehensive psychosocial assessment. Access to additional psychosocial services was provided on the basis of the social worker’s assessment, and available upon family or provider request.

The PRISM Intervention

PRISM is an early palliative care intervention based on resilience, positive psychological, and coping theories and evidence-based interventions tested in other clinical populations. This brief, manualized, skills-based program has been successfully delivered with fidelity by bachelors-level non-specialists. Four individual treatment sessions occurred approximately every other week, each 30-50 minutes long. After completing the main sessions, optional once monthly “booster” sessions were provided. Intervention materials were tailored based on age for adolescents (12-17 years old) and young adults (18-25 years). PRISM’s development, feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy has previously been reported.16, 17

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Adolescents and young adults completed a comprehensive battery of validated patient-reported outcome measures at baseline and at 6-months:

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CDRISC-10) assesses self-perceptions of resilience.24 Higher scores indicate greater resilience.

The Hope Scale assesses hopeful and goal-directed patterns of thought.25 Higher scores indicate greater hope.

The Benefit and Burden Scale for Children assesses perceived benefits and burdens of illness.26 Higher scores indicate greater benefit-finding.

The Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) Generic Short-Form assesses the domains of general physical, emotional, social, and school well-being. The PedsQL Cancer Module assesses the domains of cancer-specific symptoms, anxiety/worries, cognitions, and communication.27, 28 Higher scores indicate better quality of life.

The Kessler-6 Psychological Distress Scale (K-6) assesses global psychological distress.29, 30 Higher scores indicate greater distress.

Additional Measures

Demographics questionnaire: Adolescents and young adults reported their sex, age, and race at baseline.

Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage: The Area Deprivation Index (ADI) is a neighborhood disadvantage metric comprised of 17 education, employment, housing quality, and poverty measures derived from Census data and the American Community Survey data.31 Participant home addresses gathered from medical chart review at the time of this post-hoc analysis (July to August 2018) were entered into Neighborhood Atlas (www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu); addresses are linked to ADI scores.31 ADI state decile scores range from 1=least disadvantaged to 10=most disadvantaged and were dichotomized into less disadvantaged (1-7) vs. most disadvantaged (8-10) utilizing established cut-offs.31-33

Statistical Analyses

Sociodemographic and other characteristics at enrollment were summarized using descriptive statistics. We calculated means and standard deviations for change in patient-reported outcome measures from baseline to 6 months, by study arm and stratification subgroups of sex (males, females), age (adolescents 12-17 years, older adolescents and young adults 18-25 years), race (Whites, non-Whites), and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage (less disadvantaged, most disadvantaged). We estimated Cohen’s d effect sizes (i.e., standardized scores of PRISM vs. Usual Care effect on score change from baseline to 6 months) within stratification subgroups for each patient-reported outcome measure. By convention, Cohen’s d>0.2 is considered a small to moderate effect and Cohen’s d>0.5 is considered a moderate to large effect.34 For the majority of patient-reported outcome measures, a positive treatment effect associated with PRISM is illustrated by a positively-valenced Cohen’s d. For distress only, a positive treatment effect associated with PRISM is illustrated by a negative Cohen’s d, i.e., a reduction in distress.

As the randomized clinical trial was not powered for this post-hoc analysis, we did not test the statistical significance of treatment effect modification based on stratification variables. We utilized a conservative cut-off score of d>0.5 (a moderate to large effect) in determining whether variations in magnitude of effect sizes among stratification groups were noteworthy; differences in magnitude of effect sizes d≤0.5 between stratification subgroups were considered similar in magnitude. We report on findings observed based on descriptive summary statistics, standardized effect sizes, and graphical representations of stratification groups. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

100 adolescents and young adults were enrolled, and 92 participants (44 Usual Care, 48 PRISM) completed baseline assessment measures.17 Distribution of age, race, and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage were generally similar across study arms (Table 1). Study participants were 43% female, 73% were 12-17 years-old, 64% were White, and 24% lived in a most disadvantaged neighborhood relative to Washington State. With respect to neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, we used state (rather than national) relative comparisons as a large majority of participants lived in less disadvantaged neighborhoods on a national scale; our sample distribution is representative of Washington State where our study was conducted. PRISM recipients were less commonly female than Usual Care recipients (33% versus 55%) and less likely to speak English as a second language (2% versus 23%). Cohen’s d (95% Confidence Interval (CI)) for PRISM vs. Usual Care, by stratification variables are presented in Table 2. Data reflecting patient-reported outcome measure scores at baseline and 6 months by stratification variables are presented in supplemental Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and instrument scores at the time of enrollment.

| Usual Care (n = 44) | PRISM (n = 48) | All [N=92] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Female | 24 (55) | 16 (33) | 40 (43) |

| 12-17 years old at enrollment | 32 (73) | 35 (73) | 67 (73) |

| 18-25 years old at enrollment | 12 (27) | 13 (27) | 25 (27) |

| Non-White race | 19 (43) | 14 (29) | 33 (36) |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity | 17 (39) | 5 (10) | 22 (24) |

| Most disadvantaged (ADI score 8-10)a | 11 (24) | 10 (25) | 21 (24) |

| First language other than English | 10 (23) | 1 (2) | 11 (12) |

| Leukemia/lymphoma | 27 (61) | 30 (63) | 57 (62) |

| Central nervous system (CNS) | 3 (7) | 3 (7) | 6 (7) |

| Non-CNS solid tumor | 14 (32) | 15 (31) | 29 (32) |

| Advanced cancer at enrollment | 14 (32) | 10 (21) | 24 (26) |

| Instrument Score at Baseline | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Resilience (CDRISC-10) | 28 (5.8) | 29 (6.2) | 29 (6.0) |

| Hope-Total (Hope Scale) | 51 (8.1) | 49 (8.4) | 50 (8.3) |

| Benefit Finding (Benefit and Burden Scale for Children) | 37 (8.2) | 34 (9.5) | 35 (9.0) |

| Generic quality of life (PedsQL SF-15) | 59 (21.3) | 62 (16.0) | 61 (18.6) |

| Cancer-specific quality of life (PedsQL Cancer Module) | 65 (16.9) | 66 (15.9) | 65 (16.3) |

| Global psychological distress (Kessler-6) | 8 (4.8) | 6 (4.5) | 7 (4.7) |

The Area Deprivation Index (ADI) is a neighborhood disadvantage metric derived from Census data and the American Community Survey data utilizing participant home addresses. We stratified state decile scores ranging from 1=least disadvantaged to 10=most disadvantaged by 1-7 (less disadvantaged) vs. 8-10 (most disadvantaged) utilizing established cut-offs. Scores were not available for 2 PRISM and 4 UC participants.

Table 2.

Cohen's d (95% CI) for PRISM vs. Usual Care, by stratification variables. Counts represent numbers completing 6 month assessments.

| Gender | Age | Race | Area Deprivation Index (ADI) State Decile Scoresa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male PRISM: n=24 Usual Care: n=17 |

Female PRISM: n=12 Usual Care: n=21 |

12-17 PRISM: n=27 Usual Care: n=26 |

18-25 PRISM: n=9 Usual Care: n=12 |

White PRISM: n=27 Usual Care: n=21 |

non-White PRISM: n=9 Usual Care: n=17 |

1-7 PRISM: n=28 Usual Care: n=26 |

8-10 PRISM: n=8 Usual Care: n=8 |

|

| Resilience | 0.4 (−0.2, 1.0) | 0.7 (0.0, 1.5) | 0.3 (−0.2, 0.8) | 1.3 (0.3, 2.3) | 0.6 (0.0, 1.2) | 0.2 (−0.6, 1.0) | 0.7 (0.1, 1.2) | −0.4 (−1.4, 0.6) |

| Hope | 0.5 (−0.1, 1.1) | 0.6 (−0.1, 1.4) | 0.5 (−0.1, 1.0) | 0.9 (−0.0, 1.8) | 0.6 (0.1, 1.2) | 0.3 (−0.5, 1.1) | 0.7 (0.1, 1.2) | 0.0 (−1.0, 1.0) |

| Benefit finding | 0.4 (−0.2, 1.1) | 0.3 (−0.4, 1.0) | 0.4 (−0.1, 1.0) | 0.4 (−0.5, 1.2) | 0.2 (−0.4, 0.8) | 0.9 (0.0, 1.8) | 0.3 (−0.2, 0.9) | 0.6 (−0.5, 1.6) |

| Generic QoL | 0.3 (−0.3, 0.9) | 0.4 (−0.4, 1.1) | 0.3 (−0.3, 0.8) | 0.2 (−0.7, 1.0) | 0.2 (−0.3, 0.8) | 0.6 (−0.2, 1.4) | 0.5 (0.0, 1.1) | −0.7 (−1.7, 0.3) |

| Cancer-specific QoL | 0.4 (−0.2, 1.0) | 1.2 (0.4, 1.9) | 0.8 (0.2, 1.3) | 0.4 (−0.5, 1.3) | 0.8 (0.2, 1.4) | 0.6 (−0.3, 1.4) | 0.8 (0.3, 1.4) | 0.1 (−0.9, 1.0) |

| Distress | 0.2 (−0.4, 0.8) | −0.6 (−1.4, 0.1) | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.4) | −0.1 (−1.0, 0.7) | −0.1 (−0.7, 0.5) | −0.3 (−1.1, 0.5) | −0.4 (−1.0, 0.1) | 0.6 (−0.4, 1.6) |

Note: Variations in magnitude of effect sizes between stratification subgroups of d>0.5 (medium to large effect) are in bold.

The Area Deprivation Index (ADI) is a neighborhood disadvantage metric derived from Census data and the American Community Survey data utilizing participant home addresses. We stratified state decile scores ranging from 1=least disadvantaged to 10=most disadvantaged by 1-7 (less disadvantaged) vs. 8-10 (most disadvantaged) utilizing established cut-offs.

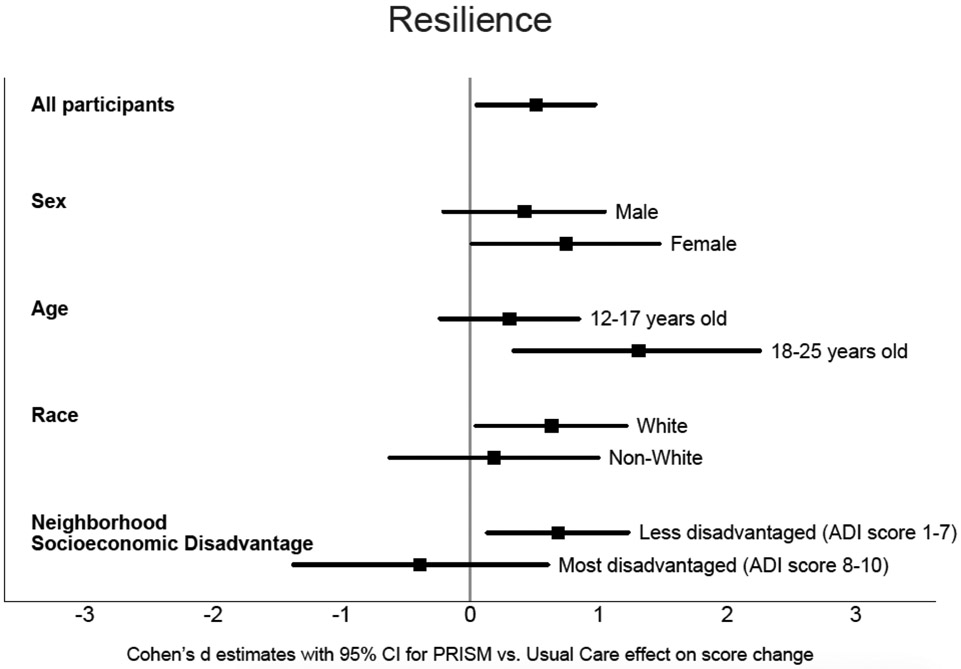

Resilience.

We observed consistent direction and magnitude of effect sizes suggesting PRISM outperformed Usual Care for resilience across the stratification subgroups of sex and race (Table 2, Figure 1). The positive treatment effect for resilience was small in adolescents 12-17 years old (d=0.3, 95% CI: −0.2,0.8) and large in older adolescents and young adults 18-25 years old (d=1.3, 95% CI: 0.3,2.3). On neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, those categorized as “less disadvantaged” showed a medium to large positive effect (d= 0.7, 95% CI: 0.1,1.2) whereas the “most disadvantaged” showed a small to medium negative effect (d=−0.4, 95% CI: −1.4,0.6).

Figure 1.

Standardized Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale score change for PRISM vs. Usual Care effect (Cohen's d, 95% Confidence Interval) by stratification subgroups

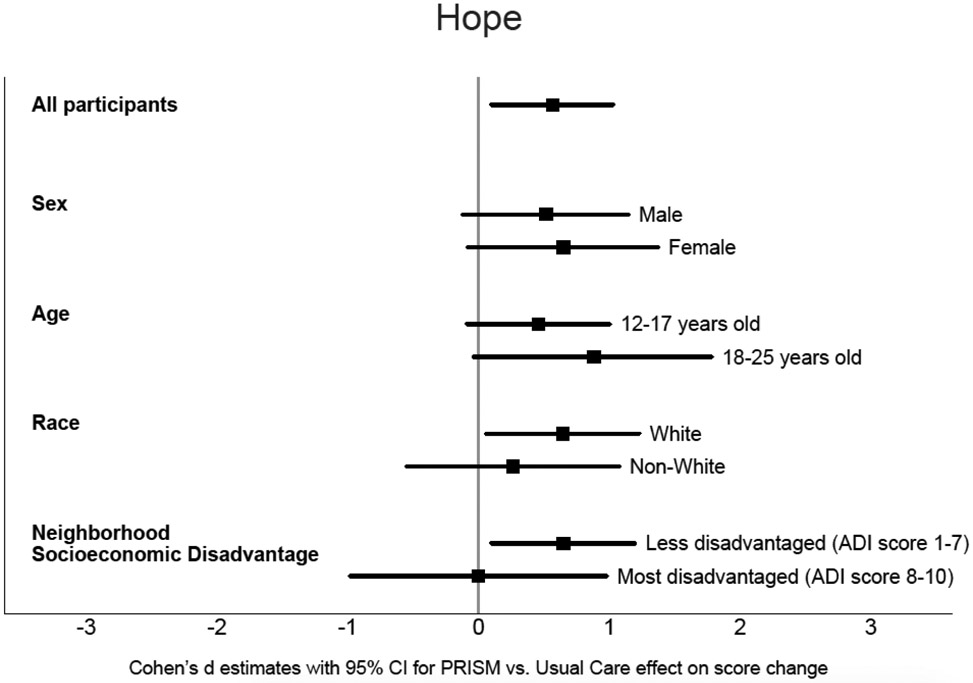

Hope.

We observed consistent direction and magnitude of effect sizes suggesting PRISM outperformed Usual Care for hope across the stratification subgroups of sex, age, and race (Table 2, Figure 2). Those categorized as “less disadvantaged” showed a medium to large positive effect (d= 0.7, 95% CI: 0.1,1.2), whereas the “most disadvantaged” showed a null effect (d=0.0, 95% CI: −1.0,1.0).

Figure 2.

Standardized Hope Scale score change for PRISM vs. Usual Care effect (Cohen's d, 95% Confidence Interval) by stratification subgroups

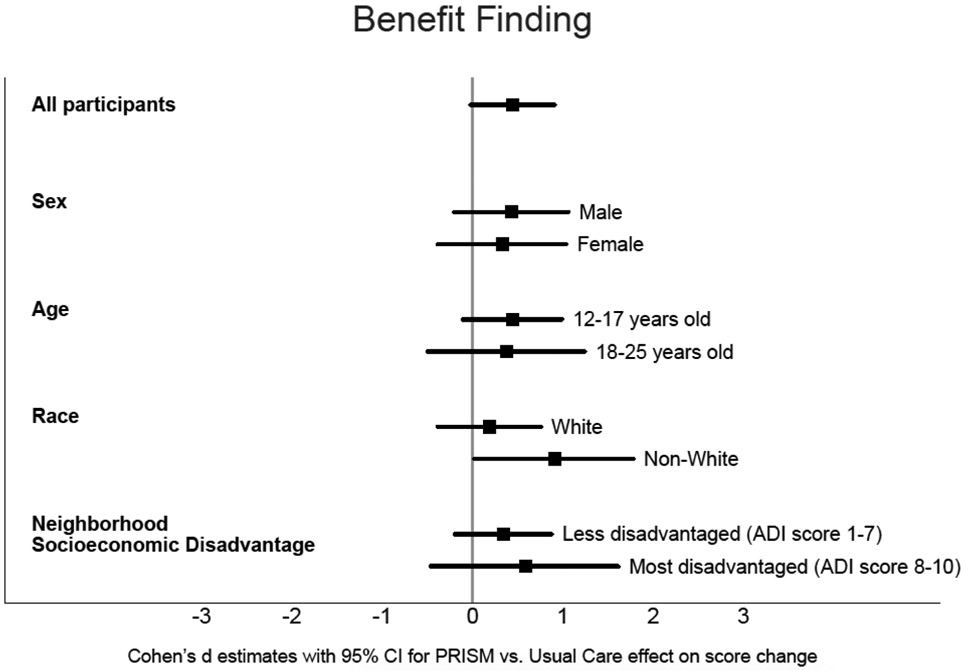

Benefit-finding.

We observed consistent direction and magnitude of effect sizes suggesting PRISM outperformed Usual Care for benefit-finding across the stratification subgroups of sex, age, and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage (Table 2, Figure 3). For race, the positive effect was small in Whites (d=0.2, 95% CI: −0.4,0.8), and large in non-Whites (d=0.9, 95% CI: 0.0,1.8).

Figure 3.

Standardized Benefit and Burden Scale for Children score change for PRISM vs. Usual Care effect (Cohen's d, 95% Confidence Interval) by stratification subgroups

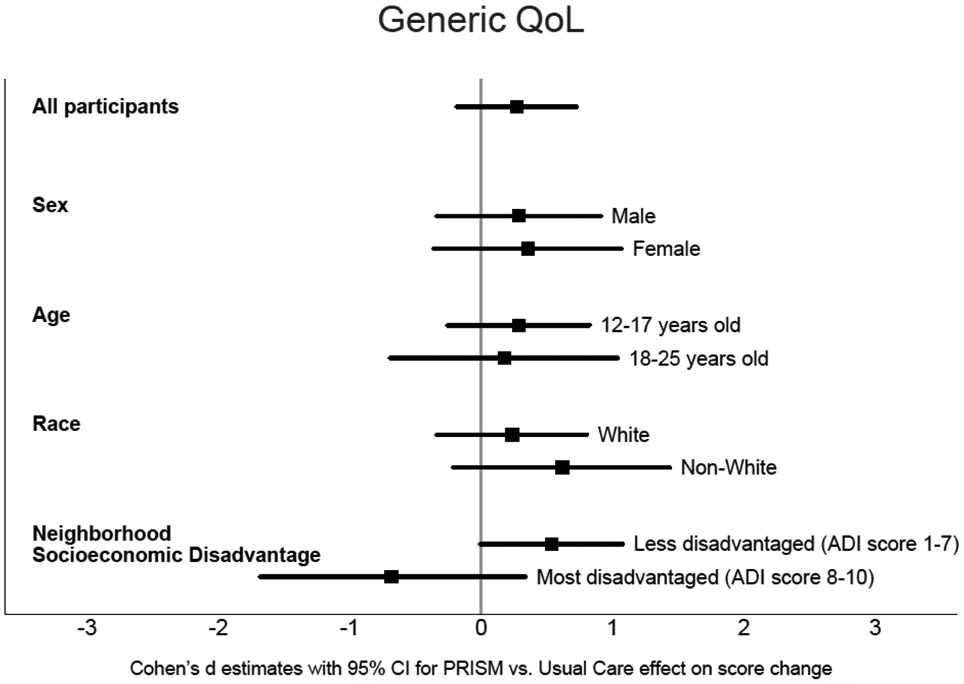

Generic quality of life.

We observed consistent direction and magnitude of effect sizes suggesting PRISM outperformed Usual Care for generic quality of life across the stratification subgroups of sex, age, and race (Table 2, Figure 4). Those categorized as “less disadvantaged” showed a medium positive effect (d=0.5, 95% CI: 0.0,1.1), whereas the “most disadvantaged” showed a medium to large negative effect (d=−0.7, 95% CI: −1.7,0.3).

Figure 4.

Standardized Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) Generic Short-Form score change for PRISM vs. Usual Care effect (Cohen's d, 95% CI) by stratification subgroups

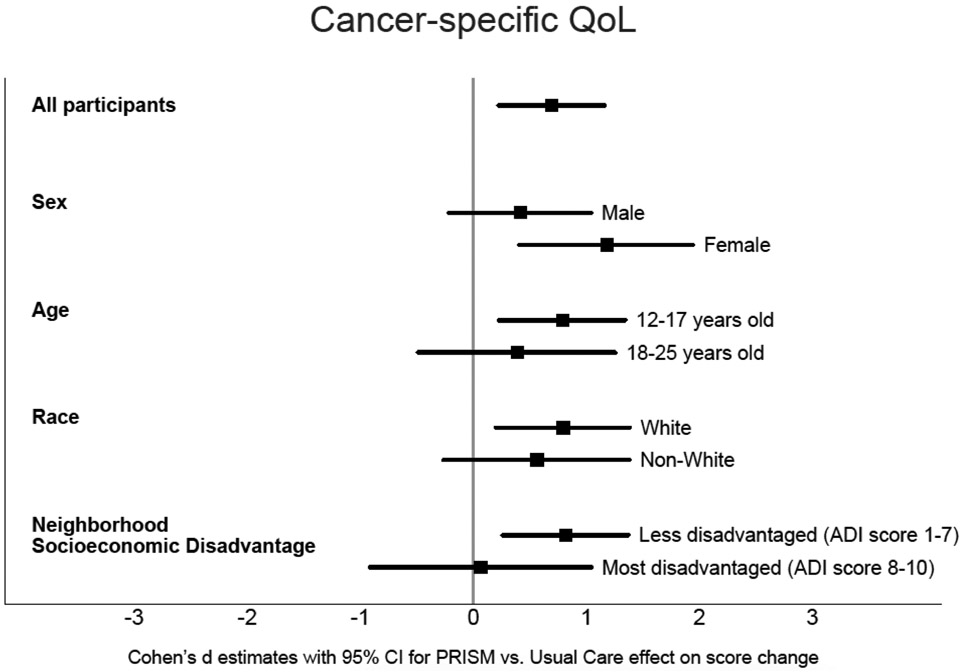

Cancer-specific quality of life.

We observed consistent direction and magnitude of effect sizes suggesting PRISM outperformed Usual Care across the stratification subgroups of age and race. The positive treatment effect was small to medium (d=0.4, 95% CI: −0.2,1.0) in males and large (d=1.2, 95% CI: 0.4,1.9) in females (Table 2, Figure 5). Those categorized as “less disadvantaged” showed a large positive effect (d=0.8, 95% CI: 0.3,1.4), whereas the “most disadvantaged” showed a null effect (d=0.1, 95% CI: −0.9,1.0).

Figure 5.

Standardized Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) Cancer Module score change for PRISM vs. Usual Care effect (Cohen's d, 95% Confidence Interval) by stratification subgroups

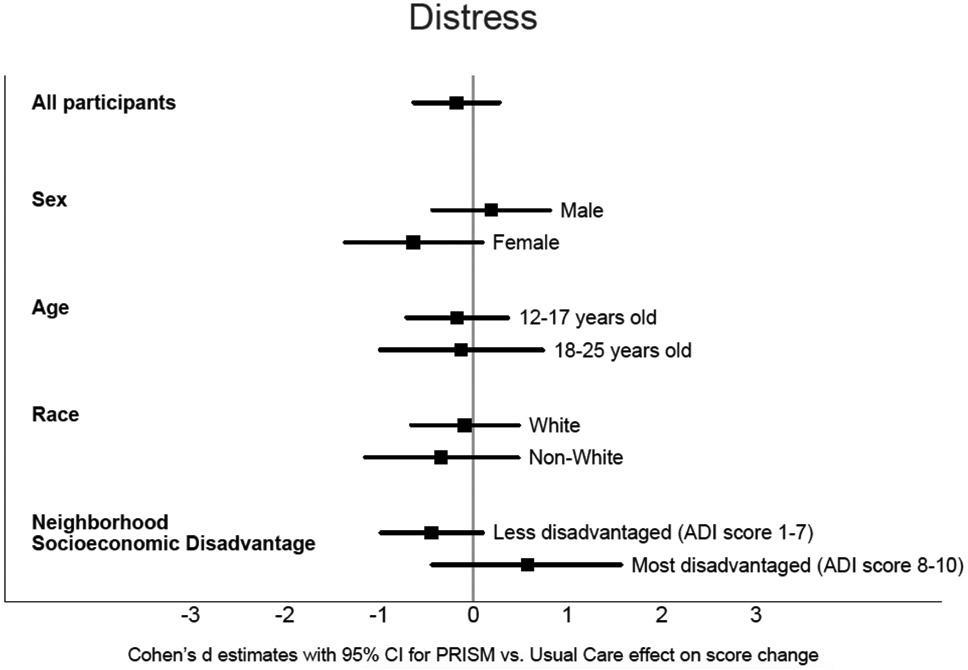

Distress.

We observed consistent direction and magnitude of effect sizes suggesting PRISM outperformed Usual Care across the stratification subgroups of age and race (Table 2, Figure 6). Males showed a small negative treatment response (increased distress, d=0.2, 95% CI: −0.4,0.8) while females had a medium to large positive treatment response (decreased distress, d=−0.6, 95% CI: −1.4,0.1). Those categorized as “less disadvantaged” showed a medium effect of decreased distress (d=−0.4, 95% CI: −1.0,0.1), whereas the “most disadvantaged” showed a medium effect of increased distress (d=0.6, 95% CI: −0.4,1.6).

Figure 6.

Standardized Kessler-6 Psychological Distress Scale score change for PRISM vs. Usual Care effect (Cohen's d, 95% Confidence Interval) by stratification subgroups

Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage

90% of participants in the PRISM arm completed all 4 main sessions; 83% had the optional 5th session. 71% had at least 1 booster session. The number of sessions did not differ for those categorized as “most disadvantaged” based on Area Deprivation Index scores. There is a moderate degree of overlap between being non-White and socioeconomically disadvantaged. 11% of White participants and 47% of non-White participants were categorized as “most disadvantaged” based on Area Deprivation Index scores. In the “non-White” category, 7 identified as Asian, 2 as Black, 11 as Hispanic/Latino, 8 as Mixed race, and 5 as “other”.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

Previous publications of the single-center phase II randomized clinical trial focused on PRISM’s efficacy and treatment effect sizes relative to Usual Care, with primary analyses adjusting for participant sex, race, and first language demonstrating unchanged slope estimates of the regression model.17 In order to better understand PRISM’s generalizability and potential to help diverse populations, we conducted this exploratory analysis of existing data. We found that PRISM’s positive effect was largely universal for adolescents and young adults with different sex, age, and racial backgrounds. The exceptions were a greater magnitude of treatment effect for females on cancer-specific quality of life, older adolescents and young adults on resilience, and non-Whites on benefit-finding. This is particularly impactful given that older and non-White adolescents and young adults are typically considered vulnerable populations. However, we identified trends to suggest that those who lived in less disadvantaged neighborhoods benefited more from PRISM and those living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods benefited less. Taken together, these finding suggest that PRISM may work for different people in different ways, and may not work consistently as currently designed for those from disadvantaged neighborhoods.

What this study adds

There is widespread interest in increasing the awareness, dissemination, and implementation of empirically supported treatments in routine clinical care.20 However, it is unclear whether such treatments, largely tested with individuals of homogeneous sociodemographic characteristics may be translatable to diverse groups. We selected sex, age, race, and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage because these are important clinical variables theorized to be associated with intervention efficacy. For example, there is evidence for sex-specific differences in emotion regulation strategies with women preferring social support and primary coping strategies (behavioral change to alleviate stress) and men preferring avoidant and passive coping strategies.35 However, little research has examined whether men and women respond differently to psychotherapy interventions and previous findings are mixed.36, 37 Likewise, prior research has shown an increase in cognitive emotion regulation strategies from middle adolescence to late adolescence and adulthood.35 Stratifying by age allowed us to explore differential responses to treatment based on developmental changes for teens compared to emerging adults. Also, few treatment studies have been conducted with ethnic minorities, who experience disproportionately greater material hardship and social stressors associated with psychological disorders than Whites38, 39 and significant disparities in access to care and quality of psychological services.40 Finally, neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with both physical and mental health such that those lowest on the hierarchy experience the poorest health outcomes.41

PRISM targets cognitive emotion regulation strategies which may be more impactful for older adolescents and young adults more facile with cognitive problem-solving due to age-normative stages of development, and for females who tend to use these skills more frequently.35 Moreover, ceiling effects were observed such that males had better baseline scores for quality of life and distress; this is unsurprising given that prevalence rates of anxiety and depressive disorders among females is higher than males.42, 43 Additionally, race and community experiences may define cultural values and inform coping strategies. Disparities due to discrimination and chronic exposure to racism, limited community resources, and neighborhood violence may contribute to traumatic stress and corresponding quality of life.40, 44, 45 Interestingly, non-White adolescents and young adults in our study demonstrated similar positive responses to PRISM as White adolescents and young adults, and experienced an even greater magnitude of treatment response on benefit-finding. Our findings underscore these complexities and nuances, and paying additional attention to these and other sociodemographic variables is critical to optimize intervention efficacy. For example, our data suggest that adolescents and young adults living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods may require step-wise interventions that begin with screening for material hardship and addressing concrete resource needs before intervening on resilience with PRISM.46, 47 Encouragingly, although previous literature has suggested that low socioeconomic status is a predictor of psychosocial treatment dropout48, the number of PRISM sessions delivered did not differ based on neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage status and an overwhelming majority of participants completed the intervention.

Limitations

This analysis has several limitations which warrant consideration. First, we utilized existing data from a phase II randomized clinical trial; these analyses were exploratory. Thus, these preliminary findings did not include formal tests of moderation and statistical significance. Due to small subsample sizes within stratification groups, however, wide confidence intervals were associated with even medium to large effect sizes. This implies that the “true” effect for those strata could be zero. Thus, our precision and corresponding confidence in the findings is limited. Our post-hoc analysis is intended to be hypothesis-generating and should be substantiated in future randomized clinical trials with larger sample sizes adequately powered for formal statistical tests of effect modification. Similarly, it is possible that our inability to detect differences in PRISM’s efficacy for stratification groups other than neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage is because we lacked power to do so.

The phase II study was conducted at a single institution and we only included English-speaking adolescents and young adults because PRISM has only been validated in English. We did not recruit participants based on pre-specified sociodemographics. We collected data on only four key sociodemographic characteristics of interest which is limited in scope. We were unable to examing the effect of language; there was only 1 participant in the PRISM arm who spoke English as a second language. We examined age effects based on the stratification of adolescents (12-17 years old) and young adults (18-25 years old); our ability to conduct finer grained age stratifications based on developmental characteristics was limited due to sample size constraints. Additionally, there was only a dichotomous (female/male) choice for sex, and adolescents and young adults with other sexual identities were unaccounted for. We were unable to parse apart race of adolescents and young adults into finer-grained analyses as numbers based on race/ethnicity were too small to compare aside from the collapsed categories of White/non-White. We observed that only those living in less disadvantaged neighborhoods experienced consistently positive treatment effects with PRISM outperforming Usual Care for all patient-reported outcome measures. Additionally, we only utilized a neighborhood-level measure of socioeconomic disadvantage and adolescents and young adults lived in relatively advantaged neighborhoods which is representative of Washington State; this has important practice implications for generalizability to disadvantaged and impoverished neighborhoods on a national level. No household-level measure was collected which may have a cumulative impact on PRISM efficacy. With respect to the moderate degree of overlap between a participant’s ethnic minority status and disadvantaged socioeconomic status, it is not possible to parse apart the independent contributions of each on patient-reported outcomes. Due to the delayed timing of the post-hoc medical record abstraction relative to the dates of the PRISM trial, it is possible that participants may have moved in the interim to a neighborhood with a different ADI score. Thus, the home addresses on record may not accurately represent all participants’ levels of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage at the time of the PRISM trial data collection. Finally, we did not collect data on the timing and influence of medical confounders such as disease progression and cancer treatment which may interact with psychosocial outcomes.

Implications and future directions

In order to create a model of psychosocial risk to inform the matching of adolescents and young adults to appropriate interventions and the tailoring of interventions to individual needs, additional variables should be collected, for example on prior stressors such as adverse childhood experiences, patient and parent psychopathology, poor family functioning, and material hardship and other financial concerns.49, 50 Although fidelity of PRISM delivery was universally excellent, participant-level engagement based on sociodemographic characteristics is unknown. Hence, we may be missing an important piece of the picture. Our findings are meant to be hypothesis-generating, and should be replicated in future treatment studies powered for this sub-analysis and deliberately sampling from diverse sociodemographic backgrounds.

In conclusion, PRISM is a promising early palliative care intervention that is efficacious and seems to work for different people in different ways. It is important to explore methods to adapt the intervention to enhance efficacy in the domains that matter to adolescents and young adults and their families. Future research will focus on the early implementation of PRISM in routine clinical care, and expanded screening for a wide range of baseline social and psychological variables that may influence its robustness and goodness-of-fit. Further research on individual characteristics that predict or moderate symptom improvement and purposeful selection of participants of diverse backgrounds will help shed light on the external validity of this evidence-based intervention.51 This will facilitate the matching of adolescents and young adults to interventions they are most likely to benefit from, tailoring of interventions to individual needs, and the dissemination and implementation of practice-ready interventions with potential for real-world impact.

Supplementary Material

Key statements.

What is already known about the topic?

Early palliative care interventions have the potential to improve psychosocial outcomes.

The Promoting Resilience in Stress Management (PRISM) intervention has been shown to be feasible, acceptable, and efficacious for adolescents and young adults with cancer.

Little is known about the generalizability of empirically supported interventions to individuals of diverse sociodemographic backgrounds.

What this paper adds

PRISM seems to work for different people in different ways.

This exploratory analysis suggests the direction and magnitude of PRISM’s positive effect is consistent across most patient-reported outcome measures for adolescents and young adults when stratified by sex, age, and race with some exceptions.

Adolescents and young adults who lived in less socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods benefited more from PRISM for the majority of patient-reported outcome measures, and those in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods benefited less.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

PRISM is a helpful early palliative care intervention for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Tailoring PRISM to meet individual needs is an important area of future research in order to enhance its impact for those presenting with pre-existing stressors.

Future research must include more diverse populations to confirm PRISM’s generalizability.

Consideration of sociodemographic characteristics may provide opportunities to strengthen palliative care interventions like PRISM.

Acknowledgments:

We thank the patients and families for their willingness to participate in this study. We also thank Michele Shaffer for her contribution to the statistical design of this study, and Claire Wharton, Lauren Eaton, Victoria Klein, Stacy Garcia, and Katy Fladeboe for their work on enrollment, data collection and management, intervention administration, and administrative support.

Funding: Dr. Lau is funded through the University of Washington Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence’s T32 Research Fellowship Program (grant number: T32 HL125195). This study was funded through grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (KL2TR000421) and CureSearch for Children’s Cancer awarded to Dr. Rosenberg. The opinions presented here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the funders.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest to report.

Research Ethics and Patient Consent: Participants provided written informed consent and the Seattle Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB Protocol #: 15300).

Data Management and Sharing: Our data cannot legally or ethically be released as our participants include minors, and they and their parents did not provide consent for data sharing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zebrack BJ. Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2011; 117: 2289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas DM, Albritton KH and Ferrari A. Adolescent and young adult oncology: an emerging field. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28: 4781–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zebrack B and Isaacson S. Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30: 1221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nass SJ, Beaupin LK, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. Oncologist. 2015; 20: 186–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eiser C, Penn A, Katz E and Barr R. Psychosocial issues and quality of life. Semin Oncol. 2009; 36: 275–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazak AE, Derosa BW, Schwartz LA, et al. Psychological outcomes and health beliefs in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer and controls. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28: 2002–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleyer A The adolescent and young adult gap in cancer care and outcome. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005; 35: 182–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guy GP Jr., Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Estimating the health and economic burden of cancer among those diagnosed as adolescents and young adults Health Aff (Millwood: ). 2014; 33: 1024–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller KA, Wojcik KY, Ramirez CN, et al. Supporting long-term follow-up of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: Correlates of healthcare self-efficacy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017; 64: 358–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molina Y, Yi JC, Martinez-Gutierrez J, Reding KW, Yi-Frazier JP and Rosenberg AR. Resilience among patients across the cancer continuum: diverse perspectives. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014; 18: 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg AR, Yi-Frazier JP, Wharton C, Gordon K and Jones B. Contributors and Inhibitors of Resilience Among Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2014; 3: 185–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonanno GA, Westphal M and Mancini AD. Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011; 7: 511–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen BL, Thornton LM, Shapiro CL, et al. Biobehavioral, immune, and health benefits following recurrence for psychological intervention participants. Clin Cancer Res. 2010; 16: 3270–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker E, Martins A, Aldiss S, Gibson F and Taylor RM. Psychosocial Interventions for Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer During Adolescence: A Critical Review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2016; 5: 310–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F and Bohlmeijer E. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13: 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg AR, Yi-Frazier JP, Eaton L, et al. Promoting Resilience in Stress Management: A Pilot Study of a Novel Resilience-Promoting Intervention for Adolescents and Young Adults With Serious Illness. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015; 40: 992–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg AR, Bradford MC, McCauley E, et al. Promoting Resilience in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer: Results From the PRISM Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg AR, Bradford MC, Barton KS, et al. Hope and benefit finding: results form the PRISM randomized control trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;e27485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misra G Psychosocial Interventions for Health and Well-Being. Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambless DL and Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998; 66: 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chambless DL, Baker MJ, Baucom DH, et al. Update on empirically validated therapies, II. The clinical psychologist. 1998; 51: 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vessey JT and Howard KI. Who seeks psychotherapy? Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1993; 30: 546. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambless DL and Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001; 52: 685–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connor KM and Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety. 2003; 18: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, et al. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991; 60: 570–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Currier JM, Hermes S and Phipps S. Brief report: Children’s response to serious illness: perceptions of benefit and burden in a pediatric cancer population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009; 34: 1129–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K and Dickinson P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer. 2002; 94: 2090–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varni JW and Limbers CA. The PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales Young Adult Version: feasibility, reliability and validity in a university student population. J Health Psychol. 2009; 14: 611–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological medicine. 2002; 32: 959–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM and Kessler RC. Improving the K6 short scale to predict serious emotional disturbance in adolescents in the USA. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010; 19 Suppl 1: 23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 161: 765–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kind AJH and Buckingham WR. Making Neighborhood-Disadvantage Metrics Accessible - The Neighborhood Atlas. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378: 2456–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Durfey SNM, Kind AJH, Gutman R, et al. Impact Of Risk Adjustment For Socioeconomic Status On Medicare Advantage Plan Quality Rankings Health Aff (Millwood: ). 2018; 37: 1065–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sawilowsky SS. New effect size rules of thumb. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimmermann P and Iwanski A. Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. International journal of behavioral development. 2014; 38: 182–94. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thase ME, Reynolds CF 3rd, Frank E, et al. Do depressed men and women respond similarly to cognitive behavior therapy? Am J Psychiatry. 1994; 151: 500–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogrodniczuk JS, Piper WE, Joyce AS and McCallum M. Effect of patient gender on outcome in two forms of short-term individual psychotherapy. J Psychother Pract Res. 2001; 10: 69–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mays VM and Albee GW. Psychotherapy and ethnic minorities. History of psychotherapy: A century of change. 1992: 552–70. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horrell SCV. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy with adult ethnic minority clients: A review. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008; 39: 160. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernal G and Scharron-del-Rio MR. Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2001; 7: 328–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Demakakos P, Nazroo J, Breeze E and Marmot M. Socioeconomic status and health: the role of subjective social status. Soc Sci Med. 2008; 67: 330–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT and Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2011; 45: 1027–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McLaughlin KA and King K. Developmental trajectories of anxiety and depression in early adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015; 43: 311–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alegria M, Vallas M and Pumariega AJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010; 19: 759–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alegria M, Alvarez K, Ishikawa RZ, DiMarzio K and McPeck S. Removing Obstacles To Eliminating Racial And Ethnic Disparities In Behavioral Health Care Health Aff (Millwood: ). 2016; 35: 991–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bona K, London WB, Guo D, Frank DA and Wolfe J. Trajectory of Material Hardship and Income Poverty in Families of Children Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Prospective Cohort Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016; 63: 105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pelletier W and Bona K. Assessment of Financial Burden as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015; 62 Suppl 5: S619–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edlund MJ, Wang PS, Berglund PA, Katz SJ, Lin E and Kessler RC. Dropping out of mental health treatment: patterns and predictors among epidemiological survey respondents in the United States and Ontario. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159: 845–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kazak AE, Brier M, Alderfer MA, et al. Screening for psychosocial risk in pediatric cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012; 59: 822–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schilling EA, Aseltine RH Jr. and Gore S. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: a longitudinal survey. BMC Public Health. 2007; 7: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turner JA, Holtzman S and Mancl L. Mediators, moderators, and predictors of therapeutic change in cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2007; 127: 276–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.