Abstract

A comprehensive characterization of the molecular processes controlling cell fate decisions is essential to derive stable progenitors and terminally differentiated cells that are functional from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). Here, we report the use of quantitative proteomics to describe early proteome adaptations during hPSC differentiation toward pancreatic progenitors. We report that the use of unbiased quantitative proteomics allows the simultaneous profiling of numerous proteins at multiple time points, and is a valuable tool to guide the discovery of signaling events and molecular signatures underlying cellular differentiation. We also monitored the activity level of pathways whose roles are pivotal in the early pancreas differentiation, including the Hippo signaling pathway. The quantitative proteomics data set provides insights into the dynamics of the global proteome during the transition of hPSCs from a pluripotent state toward pancreatic differentiation.

Keywords: differentiation, human, pancreatic progenitors, pluripotent, proteomics, stem cells

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) and in vitro manipulation of cell fate provide a unique approach for derivation of maturing cell types for cell replacement therapy and to generate model systems for studying human organ development and disease.1–3 The molecular characterization of intermediate cell states during the differentiation process has so far been insufficiently addressed.

Global quantitative proteomics allows for simultaneous profiling of cellular proteomes at multiple time points during hPSC differentiation. Thus, utilizing this technology improves our understanding of the dynamic protein abundance patterns regulating hPSC differentiation. Here, we combine in-depth quantitative proteomics analysis with existing singular protein tracking methods (eg, immunofluorescence [IF] and flow cytometry) to exemplify the power of global quantitative proteomics for directed differentiation of hPSCs toward pancreatic progenitor cells.

Differentiated multipotent pancreatic progenitors are considered key for both modeling early pancreas development and for future treatment of diabetes.4,5 These cells can produce glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells both in vitro6,7 and in vivo.8,9 However, cellular heterogeneity has been recognized as a potential concern secondary to batch-variability during the final stages of differentiation toward β-like cells. This caveat may in turn contribute to the variability encountered when using published protocols for differentiation.6,7 We propose that comprehensive and systematic proteomics characterization is useful to fine-tune the differentiation process, and to discover additional proteins contributing to pancreatic cell fate establishment.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Cell sources

Commercial control fibroblasts (AG16102) were purchased from Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, New Jersey), and reprogrammed into human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) in two separate labs (A.K.K.T. and R.N.K. labs) using nonintegrative CytoTune-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) and integrative human STEMCCA Cre-excisable constitutive polycistronic (OKSM) lentiviruses,10 respectively, hence corresponding to two independent hiPSC lines. The H9 line, WA09 (human embryonic stem cells [hESCs]), came from the WiCell Research Institute, Inc (Madison, Wisconsin). For the proteomics study, we generated replicates for each of the hiPSC-derived cell cultures, including triplicates of hiPSCs and cells differentiated until day 17, and duplicates for days 5 and 12. The cells were multiplexed with isobaric labeling (tandem mass tag [TMT]) and subjected to liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis on an Orbitrap Fusion instrument (as detailed below). For the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), FACS, and Western blot validation experiments, cells were harvested at days 0, 5, 12, and 17 of the pancreatic progenitor protocol. For the stem-cell-derived β (SC-β) cell protocol, differentiating cells were harvested at days 0, 13 (corresponding to pancreatic progenitor cells), 20, and 35 (corresponding to SC-β cells). qPCR validation experiments were done in triplicates both for pancreatic progenitor differentiation as well as the SC-β cell protocol. FACS and Western blot validation experiments were performed at least twice.

2.2 |. Differentiation protocols

hiPSCs and hESCs were differentiated into pancreatic progenitors via modification of previously described methods.11–13 In brief, hPSCs were treated with Collagenase IV (Life Technologies, Waltham, Massachusetts) and Dispase (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) at a 1:1 ratio for 3–5 minutes before being manually passaged and passed through a 70 μm cell strainer to remove the mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). hPSCs were then differentiated 2 days later in RPMI 2% B27 (without vitamin A) (Gibco, Waltham, Massachusetts) supplemented with 100 ng/mL Activin A (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota), 3 μM CHIR99021 (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK), 10 μM LY294002 (LC Labs, Woburn, Massachusetts) for 3 days, 50 ng/mL Activin A for 2 days, 50 ng/mL FGF2, 3 μM all-trans retinoic acid (RA) (WAKO, Osaka, Japan), 10 mM nicotinamide (Nic) (Sigma Aldrich, Singapore) for 5 days, 50 ng/mL FGF2, 3 μM RA, 10 mM Nic, 20 μM DAPT (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 4 days and 50 ng/mL FGF2, 10 mM Nic, 20 μM DAPT for 3 days to derive pancreatic progenitors.

hPSCs were also differentiated into SC-β cells following the differentiation protocol by Pagliuca et al7 on low attachment plates with shaking for the duration of the whole differentiation protocol, without transfer to a bioreactor.

2.3 |. mRNA extraction and reverse transcription

PrepEase RNA Spin Kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, California) was used to extract total RNA from the hESC line H9 or the hiPSC line that was differentiated into pancreatic progenitor-like and/or pancreatic β-like cell lineages. After 300 μL of RA1 buffer was added to each well of a 12-well tissue culture plate, homogenates were transferred to spin columns and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To remove genomic DNA from the preparation, DNase was diluted in 10× reaction buffer provided in the kit and on-column incubation was allowed to take place for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT). After washing the column with the RA2 and RA3 buffers provided in the kit, RNA was eluted with 40 μL of RNase-free water following centrifugation at 15 000g for 1 minute at RT. Purified RNA was quantified using the NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A 2 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, Massachusetts) and cDNA was diluted to a final concentration of 2.5 ng/μL in RNase-free water.

2.4 |. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

qPCR was performed on the CFX384 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California) with iTaq universal SYBR Green supermix fluorescent label (Bio-Rad). Each reaction consisted of 1.9 μL nuclease-free water, 1× SYBR green supermix, 300 nM of each forward and reverse primer and 2.5 μL of cDNA template for a final volume of 10 μL. Samples were run in duplicate on 384-well plates (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). Cycling parameters were as follows: 95°C for 3 minutes followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 seconds and 60°C for 30 seconds. At the end of the amplification phase, a dissociation step was performed to identify a single melting temperature for each primer set. Sequences of primers used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

List of quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) primers

| Gene | Accession number | Forward primer (5′ to 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACTB | NM_001101.3 | TTGCCGATCCGCCGCCCGTC | CCCATGCCCACCATCACGCCCTGG |

| AFP | NM_001134.3 | TGCTTCCAAACAAAGGCAGCAACAG | TGTACATGGGCCACATCCAGGAC |

| BAPX1 | NM_001189.4 | GCACCAGGCCAGGGGTTGAT | AGATGTGGAGACCCCCGGCT |

| CDX2 | NM_001265.6 | CGGCAGCCAAGTGAAAACCAGG | TCGGCTTT CCTCCGGATGGTG |

| CEBPA | NM_004364.4 | CCGGATCTCGAGGCTTGCCC | TAGACGCACCAAGTCCGGCG |

| CERI | NM_005454.2 | CATTGGGAGACCTGCAGGACAGT | CGCGGCTCCAGGAAAATGAACAG |

| HOXD10 | NM_002148.3 | CGTGTCCAGTCCCGAAGTGC | CTGATCTCTAGGCGGCGCTC |

| LRIG3 | NM_001136051.2 | TCCCCACTCCAACCTGCGAC | CCACACAGCAAACCACGGCT |

| OSR1 | NM_145260.3 | TGGTTCAGACCCAGCGAGGGA | CTGAAGGGGACTGGGGAAGCC |

| PBX1 | NM_002585.3 | ATTTCTGGATGCGCGGCGGAA | GCTTGGCTTCCATGGGCTGACA |

| SOX2 | NM_003106.3 | GACGGAGCTGAAGCCGCCGGG | CGCTGCCCGCGGGACCACAC |

| TEAD1 | NM_021961.5 | AGGATT GCCCCAGGTGTCCC | GCCATTTGTGCTCGCCTGGT |

| YAP1 | NM_001282101.1 | AACTGCTTCGGCAGGTGAGGC | CCCACCATCCTGCTCCAGTGT |

2.5 |. Immunofluorescence staining

The cells were fixed in 1% PFA, washed with PBS, and blocked with 5% donkey serum for 1 hour. Primary and secondary antibodies were both diluted with 2% donkey serum. Antibody sources were as follows: CXCR4-APC conjugated, BD Biosciences (1:20); SOX17-PE conjugated, R&D Systems (1:20); PDX1, Cell Signaling (1:100); HNF1β, Santa Cruz (1:100); NGN3, BCBC. The primary antibody (1:100) was incubated overnight at 4°C. The secondary (1:400) was added the next day and incubated for 1 hour at RT (in the dark). The nuclei were stained with DAPI for 2–5 minutes on a rocker.

2.6 |. Flow cytometry

2.6.1 |. Pancreatic progenitors

Differentiated cells were dispersed into single cells using trypsin 0.25% (Life Technologies) at 37C for 5 minutes and neutralized with DMEM 10% FBS (Logan, Utah). Single cells were isolated using 40 μM filters. The cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 20 minutes at RT, washed with ice-cold FACS buffer (PBS + 5% FBS and resuspended in FACS buffer). For cells stained for intracellular proteins, resuspension was done in FACS buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Blocking and antibody staining were performed in 96-well plates. After 1 hour of blocking at RT, cells were subsequently resuspended in FACS buffer with primary antibodies and incubated for 1 hour at RT. Antibodies used: PDX1, ab47308 (Abcam) (1:100) and NKX6.1, LS-C124275 (Life Span, Seattle, Washington) (1:100). Cells were washed three times with FACS buffer and then incubated in FACS buffer with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at RT. Secondary antibodies used were Alex Fluor 488 Donkey Anti-Goat IgG (H+L), A11055 (1:500) and Alex Fluor 594 Goat Anti-Guinea Pig IgG (H+L), A11076 (1:500) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After washing three times with FACS buffer, cells were analyzed using LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California). FACS analysis was performed using FlowJo software.

2.6.2 |. Definitive endoderm

The staining of definitive endoderm cells was carried out according to the protocol above, except for the primary antibody staining, whereby the cells were first blocked with FACS buffer and then stained with CXCR4-APC conjugated primary antibody, BD Biosciences (1:20) for 1 hour at RT. After washes, cells were then blocked with FACS buffer +0.1% Triton X-100 and stained with SOX17-PE conjugated primary antibody, R&D Systems (1:200). Because the primary antibodies were conjugated, secondary antibody staining was not performed.

2.7 |. Western blotting

Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with trypsin (Life Technologies) for 5 minutes at 37°C. Dislodged cells were neutralized with MEF media (Logan) and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes to obtain the cell pellet. Cell pellet were lysed in M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the presence of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma Aldrich). Protein lysates were then quantified using BCA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) were performed using the Mini-PROTEAN Tetra Cell system (Bio-Rad) at 150 V for 1 hour. Forty micrograms of proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad) at 100 V for 1 hour. The blots were then blocked for 1 hour in 5% blocking buffer (nonfat milk powder) and probed with the respective primary antibodies and secondary antibodies. TEAD1, Cell Sig #12292 (1:1000), YAP1, Cell Sig #14074 (1:1000), Phospho SMAD1/5/9, Cell Sig #13820 (1:1000), Total SMAD1, Cell Sig #9743S (1:1000), Phospho SMAD2, Cell Sig #3108 (1:1000), Total SMAD2, Cell Sig #3102 (Danvers, Massachusetts) (1:1000), β-ACTIN, Sigma #A5541 (Sigma Aldrich) (1:20000). Chemiluminescent signals were detected using Super Signal West Dura Extended Duration substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.8 |. Cell lysis and protein digestion

Cell cultures were washed with PBS (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California) and harvested by centrifugation, and resuspended in PBS containing protease inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Cells were lysed in buffer containing 8 M urea, 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES pH 8.5 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri), and protease inhibitors. The protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Novagen EMD Chemicals, San Diego, California). Dry aliquots containing ~100 μg of proteins were reduced with 10 mM TCEP (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and incubated for 30 minutes at RT, alkylated with 15 mM iodoacetamide and incubated for 30 minutes at RT in the dark. Excess iodoacetamide was quenched with 15 mM DTT for 15 minutes at RT in the dark. Chloroform-methanol precipitation was performed as previously described.14 Each sample was resuspended in 200 mM HEPES pH 8.5, and digested with LysC (Wako, Richmond, Virginia) at an enzyme to protein ratio of 1:100 for 3 hours at RT. This was followed by trypsin digestion at an enzyme to protein ratio of 1:50 overnight at 37°C.

2.9 |. TMT 10-plex labeling

TMT reagents were resuspended in ACN (Sigma-Aldrich). Desalted peptides were resuspended in 100 μL of 200 mM HEPES pH 8.5, 30 μL of ACN, and 10 μL of the TMT reagents were added to the respective peptide samples, gently vortexed, and incubated for 1.5 hours at RT. To prevent unwanted labeling, the reaction was quenched by adding 10 μL of 5% hydroxylamine and incubated for 15 minutes at RT. Equal amounts of the TMT-labeled samples were combined and concentrated to near dryness, followed by desalting via C18 solid phase extraction.

2.10 |. Off-line basic pH reversed phase fractionation

The combined labeled peptide samples were pre-fractionated by basic pH reverse phase HPLC as previously described,14 using an Agilent (P/N 770995–902) 300Extend-C18, 5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm id column, connected to an Agilent Technology off-line LC-system. Solvent A was 5% ACN, 10 mM NH4HCO3 pH 8, and solvent B was 90% ACN, NH4HCO3 pH 8. The samples were resuspended in 500 μL solvent A and loaded onto the column. Column flow was set to 0.8 mL/min and the gradient length was 70 minutes, as follows: from 0 to 35 minutes solvent 50% A/ 50% B, from 35 to 50 minutes 100% B, and from 50 to 70 minutes 100% A. The labeled peptides were fractionated into 96 fractions, and further combined into a total of 12 fractions. Each fraction was acidified with 1% formic acid (FA) (Sigma-Aldrich), concentrated by vacuum centrifugation to near dryness, and desalted by StageTip. Each fraction was dissolved in 5% ACN/ 5% FA for LC-MS/MS analysis.

2.11 |. LC-MS3 analysis

From each of the 12 fractions, approximately 5 μg was dissolved in 1% aqueous FA prior to LC-MS/MS analysis on an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, California) coupled to a Proxeon EASY-nLC II liquid chromatography (LC) pump (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were fractionated on a 75 μm inner diameter microcapillary column packed with approximately 0.5 cm of Magic C4 resin (5 μm, 100 Å, Michrom Bioresources) followed by approximately 35 cm of GP-18 resin (1.8 μm, 200 Å, Sepax, Newark, Delaware). For each analysis, we loaded approximately 1 μg onto the column.

Peptides were separated using a 3-hour gradient of 6% to 26% acetonitrile in 0.125% FA at a flow rate of approximately 350 nL/min. Each analysis used the multinotch MS3-based TMT method15 on an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer. The scan sequence began with an MS1 spectrum (Orbitrap analysis; resolution 120 000; mass range 400–1400 m/z; automatic gain control [AGC] target 2 × 105; maximum injection time 100 ms). Precursors for MS2/MS3 analysis were selected using a TopSpeed of 2 seconds. MS2 analysis consisted of collision-induced dissociation (quadrupole ion trap analysis; AGC 4 × 103; normalized collision energy [NCE] 35; maximum injection time 150 ms). Following acquisition of each MS2 spectrum, we collected an MS3 spectrum using our recently described method15 in which multiple MS2 fragment ions were captured in the MS3 precursor population using isolation waveforms with multiple frequency notches. MS3 precursors were fragmented by high-energy collision-induced dissociation (HCD) and analyzed using the Orbitrap (NCE 55; AGC 5 × 104; maximum injection time 150 ms, resolution was 60 000 at 400 m/z).

2.12 |. Mass spectrometry data analyses

The acquired raw data files were converted to peak lists using MSConvert16 and searched using X!Tandem,17 MyriMatch,18 MS Amanda,19 MS-GF+,20 Comet,21 and OMSSA22 via SearchGUI23 version 1.24.0 against a concatenated target/decoy version of the Homo sapiens reviewed complement of UniProt (downloaded October 2014: 20 196 target sequences) where the decoy sequences are the reversed version of the target sequences.

The search settings were: (a) carbamidomethylation of Cys (+57.021464 Da), TMT 10-plex on peptide N-term peptide and Lys (+229.163 Da) as fixed modifications; (b) oxidation of Met (+15.995 Da) as variable modification; (b) precursor mass tolerance 10.0 ppm; (d) fragment mass tolerance 0.5 Da; and (e) trypsin as enzyme allowing maximum two missed cleavages. All other settings were set to the defaults of SearchGUI.

The search engine results were assembled into peptides and proteins using PeptideShaker24 version 0.37.3 validated at a 1% false discovery rate (FDR) estimated using the target and decoy distributions.25 A confidence level is provided for every match as complement of the posterior error probability, estimated using the target and decoy distributions of matches.26 Notably, protein ambiguity groups were built based on the uniqueness of peptide sequences in proteins as described in Reference 27, and a representative protein was chosen for every group based on the evidence level provided by UniProt. In the following analysis, proteins identified by MS will implicitly refer to protein ambiguity groups.

The MS proteomics data along with identification results have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange consortium28 via the PRIDE partner repository29,30 with the data set identifiers PXD003338.

For each validated protein, the TMT reporter ions were extracted from spectra of validated PSMs and de-isotoped using the isotope abundance matrix31 provided by the manufacturer. Intensities were normalized via the median intensity to limit the ratio deviation.32 Peptide and protein ratios were estimated using maximum likelihood estimators.33 Only proteins presenting two or more validated and quantified peptides were retained for the quantitative analysis. Standard contaminants were excluded from downstream statistical analysis.

The pathway analyses were generated through the use of QIAGEN’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, QIAGEN Redwood City, www.qiagen.com/ingenuity). We used the software EPCLUST (http://www.bioinf.ebc.ee/EP/EP/EPCLUST) and k-means clustering (n = 15) to illustrate dynamic proteome changes.

3 |. RESULTS

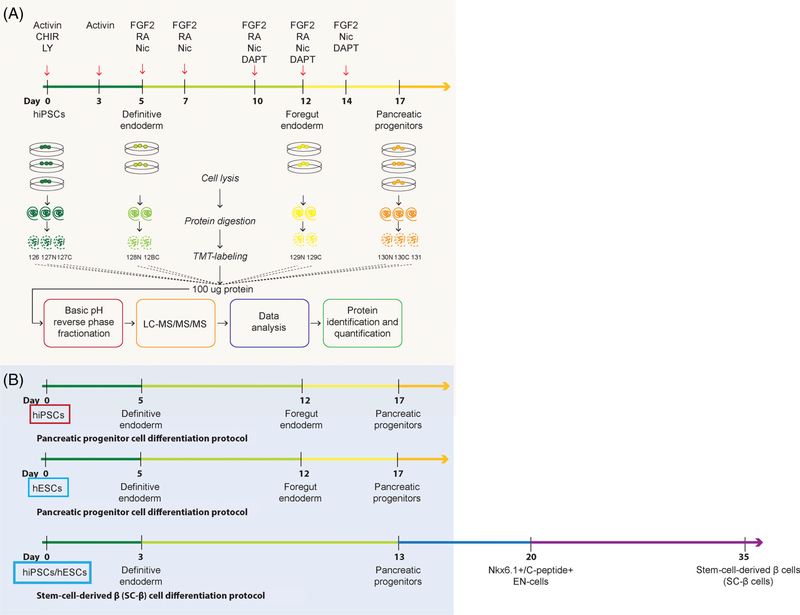

To describe the proteome dynamics during early stages of pancreatic differentiation, we used a serum-free differentiation protocol34 to produce definitive endoderm, foregut endoderm and pancreatic progenitor cells (Figure 1). IF confirmed NANOG+ cells in hiPSCs (day 0), SOX17, and CXCR4 expression in definitive endoderm cells (day 5), HNF1β+ cells in foregut endoderm (day 12), and positive staining for PDX1 in pancreatic progenitors at day 17 of the differentiation protocol (Supplementary Figure S1A,B). Flow cytometry analyses further confirmed >80% SOX2+ cells at day 0, 30%−50% SOX17+ cells, 70%90% CXCR4+ cells, 40%−50% SOX17+ CXCR4+ cells at day 5, >60% HNF1β+ cells at day 12, and >90% PDX1+ cells, 10%−30% NKX6.1+ cells at day 17 of differentiation in iAGb hiPSCs and H9 hESCs (Supplementary Figure S1C,D). We multiplexed triplicates (n = 3) from each of days 0 and 17, and duplicates (n = 2) from each of days 5 and 12 with isobaric labeling (TMT). A total of 10 samples (TMT 10-plex) from hiPSCs, representing the temporal course of early pancreas differentiation, were combined, subjected to basic pH reversed-phase fractionation and analyzed by liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (Figure 1A). Our proteomics analysis allowed for confident (1% FDR) identification of 7790 protein groups (after grouping of proteins with common peptides27) of which 6898 protein groups were quantified across all 10 samples with at least one unique peptide sequence. Key findings from our proteomics experiment were subsequently independently validated using qPCR and Western blotting across two additional cell lines, including the iAGb hiPSCs and H9 hESCs differentiated toward pancreatic progenitors as well as SC-β cells (Figures 1B, 2–4; Supplementary Figure S1E).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic overview of in vitro pancreatic progenitor differentiation and the experimental proteomics workflow. A, Quantitative mass spectrometry-based study with time course characterization of proteomics changes during in vitro differentiation of human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) toward pancreatic progenitors. This figure illustrates the 17-day pancreatic differentiation protocol.11,34,57 Cells were harvested at four developmental time points: hiPSCs (day 0), definitive endoderm (day 5), foregut endoderm (day 12), and pancreatic progenitors (day 17). Triplicates from each of days 0 and 17, and duplicates from each of days 5 and 12, were processed for proteomics analysis (lysis, digestion, multiplexed with isobaric labeling ([tandem mass tag [TMT]) and combined prior to basic pH reversed-phase fractionation and analyzed by liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry for protein identification and quantification. B, Proteomics findings were independently validated in two cell lines, including one new hiPSC line (also derived from AG16102) as well as one human embryonic stem cell (hESC) line (H9). Both lines were differentiated according to the pancreatic progenitor protocol, and also following the stem-cell-derived β (SC-β) cell protocol7

FIGURE 2.

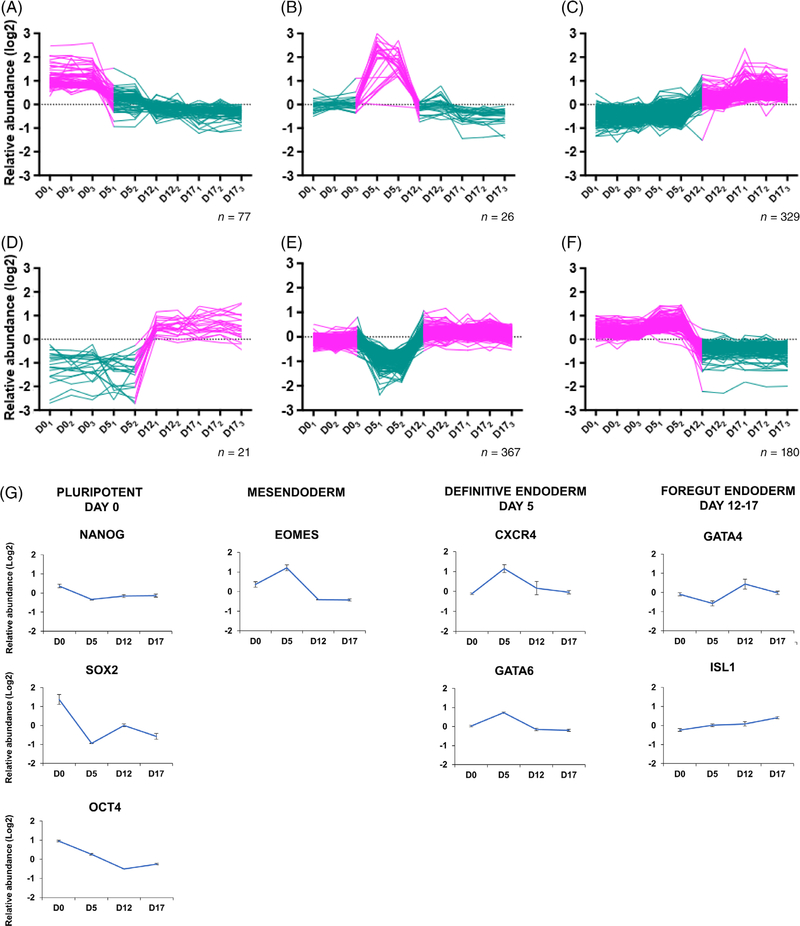

Clustering of proteome abundance profiles during differentiation toward pancreatic progenitors. A-F, The log2 relative abundance of all proteins quantified in the current data set (6898 proteins) was subjected to k-means clustering (n = 15). The six most distinct clusters are shown. Increased relative abundance is shown in red, whereas decreased relative abundance is shown in green. G, Markers for pluripotency and early pancreatic differentiation. H, A selection of proteins from clusters A-C were independently validated by gene expression analysis in two cell lines, including one human embryonic stem cell (hESC) (H9) line in (i) and (iii) and one human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) line in (ii). Both lines were differentiated according to the pancreatic progenitor protocol (i) and (ii), additionally H9 cells were differentiated following the stem-cell-derived β (SC-β) cell protocol (iii).7 I, Genes from the stomach, liver, and intestinal lineage were validated using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analyses in H9 cells

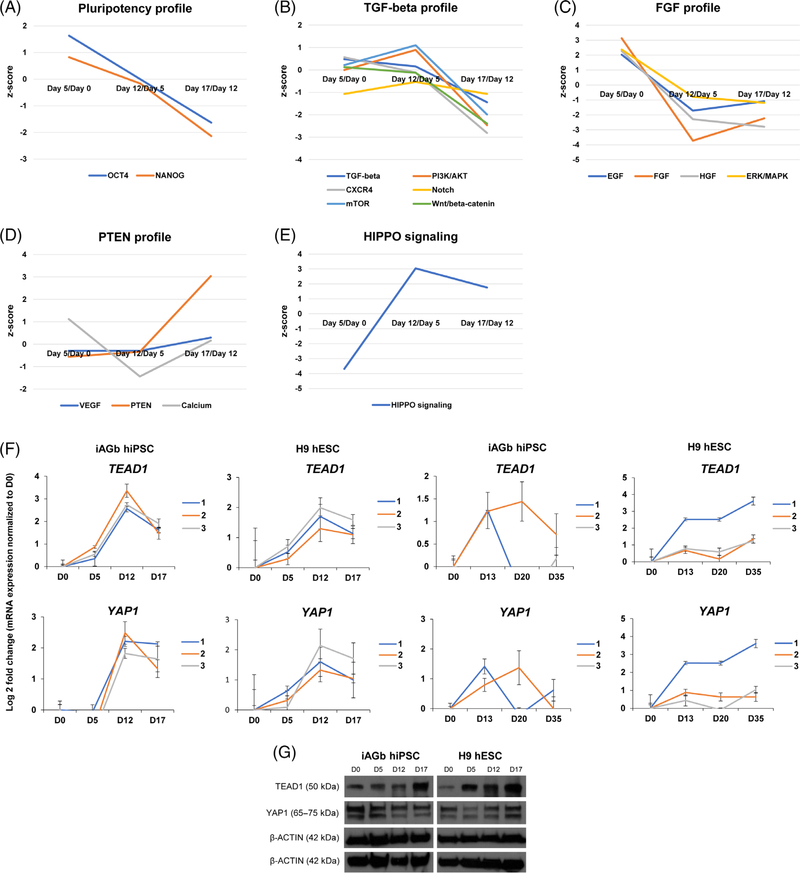

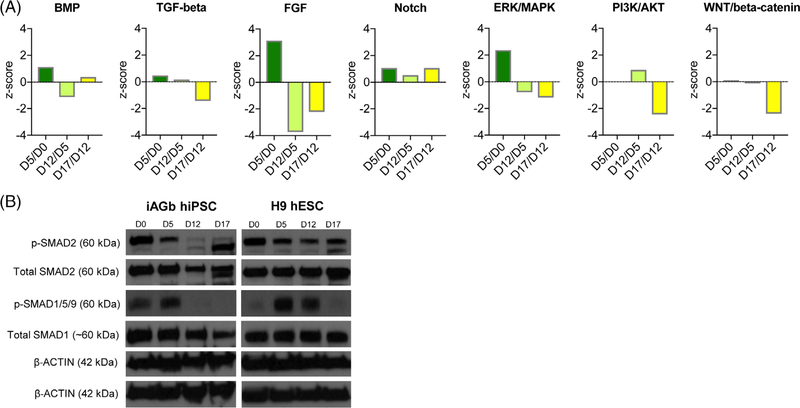

FIGURE 4.

Groups of canonical signaling pathways with similar activation patterns, comparing the proteome of human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) to that of cells differentiated until day 5, days 5 to 12, and days 12 to 17, respectively. A, OCT4 and NANOG signaling pathways. B, TGF-β, Notch, PI3K-Akt, mTOR, CXCR4, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. C, Epidermal (EGF), hepatocyte (HGF) and fibroblast growth factors (FGF) and ERK/MAPK signaling pathways. D, VEGF, PTEN, and calcium signaling. E, The activation profile of Hippo signaling pathway. The y-axis displays the z-score, whereas the x-axis shows the time point of differentiation. F, The abundance level of TEAD1 and YAP1 were validated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using two additional cell lines, one human embryonic stem cell (hESC) line (H9) as well as in a second line of hiPSCs derived from fibroblasts AG16102. The validation was done in cells differentiated according to the pancreatic progenitor protocol (i) and (ii), as well as stem-cell-derived β (SC-β) cell protocol (iii).7 Error bars indicate SD of triplicate samples from three independent experiments labeled 1, 2, 3 in the figures. G, TEAD1 and YAP1 protein expression level were also assessed using Western blotting on iAGb hiPSC line and H9 hESC line

3.1 |. Proteome adaptations occur in waves during early differentiation

To obtain an overview of the global proteome changes occurring during early stages of in vitro pancreatic differentiation, we clustered the 6898 quantified proteins based on their time course abundance profiles using k-mean clustering (n = 15). This approach allowed us to identify protein abundance patterns characteristic for the various differentiation stages. Although the levels of most proteins (5992 of 6898) showed similar abundance levels, 906 proteins showed changes in protein profile with characteristic waves of proteome adaptations at early stages of differentiation (Figure 2A–F).

Three distinct clusters emerged including one with the highest abundance at day 0 (Figure 2A), one on day 5 (Figure 2B), and one from day 12 until day 17 (Figure 2C), whereas three other waves showed mirror-image abundance profiles, with decreased abundance at the corresponding stages of differentiation (Figure 2D–F). The proteins included in the different clusters are available in Supplementary Table S1.

We compared our proteomics data with previously reported proteomics characterization of hiPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine cells35 (Supplementary Table S2). Additionally, our proteomics analysis showed increased protein levels of the pluripotent stem cell markers NANOG, SOX2, and OCT4 (Figure 2G). Proteins of the definitive endoderm-specific cluster35 were confirmed in our data, including increased protein levels of the mesendoderm marker EOMES and GATA6 in our day 5 cells (Figure 2G). We also found increased protein levels of CXCR4 at day 5. At the primitive gut tube stage (day 12), we found increased GATA4 levels. Moreover, we found increasing protein levels of the transcription factor ISL1 from day 12 until day 17.

We observed that several of the proteins had abundance profiles correlating with that of well-curated markers of pluripotency and differentiation. To evaluate whether the protein profiles of the clusters (Figure 2A–F) were also detectable at the mRNA level, two additional cell lines (one new hiPSC and one hESC) were differentiated toward pancreatic progenitors using the same protocol as used for the proteomics experiment (Figure 1B). Additionally hESCs were differentiated following the SC-β cell protocol7 (Figure 1B). The increased gene expression levels of SOX2 at day 0 using both protocols (Figure 2H, ii and iii) across two different cell lines validated the increased protein expression of SOX2 previously identified in cluster A. Increased gene expression levels of CER1 and LRIG3 at day 5 (pancreatic progenitor protocol) were observed for both the hESC and new hiPSC lines (Figure 2H, i and ii), validating the increased protein level of CER1 and LRIG3 found in cluster B. Furthermore, following the SC-β cell protocol, we found increased expression of CER1 and LRIG3 at day 13 corresponding to pancreatic progenitor cells. Increased gene expression levels of PBX1 validated the increased protein level of PBX1 at the two latest stages of the pancreatic progenitor protocol, corresponding to day 12 (foregut endoderm) and day 17 (pancreatic progenitors) for both hiPSC- and hESC-derived cells. The same was observed in hESCs differentiated until day 13 (SC-β cell protocol).7 We also evaluated the fate commitment of the differentiated cells to other lineages such as the stomach, liver, and intestine (Figure 2I), and observed some transcripts representing other gut cell types. Overall, comparison of signature markers both with gene expression and proteomics profiling showed corresponding abundance profiles, validating our proteomics approach for the discovery of protein signatures.

3.2 |. Evaluation of target pathways of the differentiation protocol

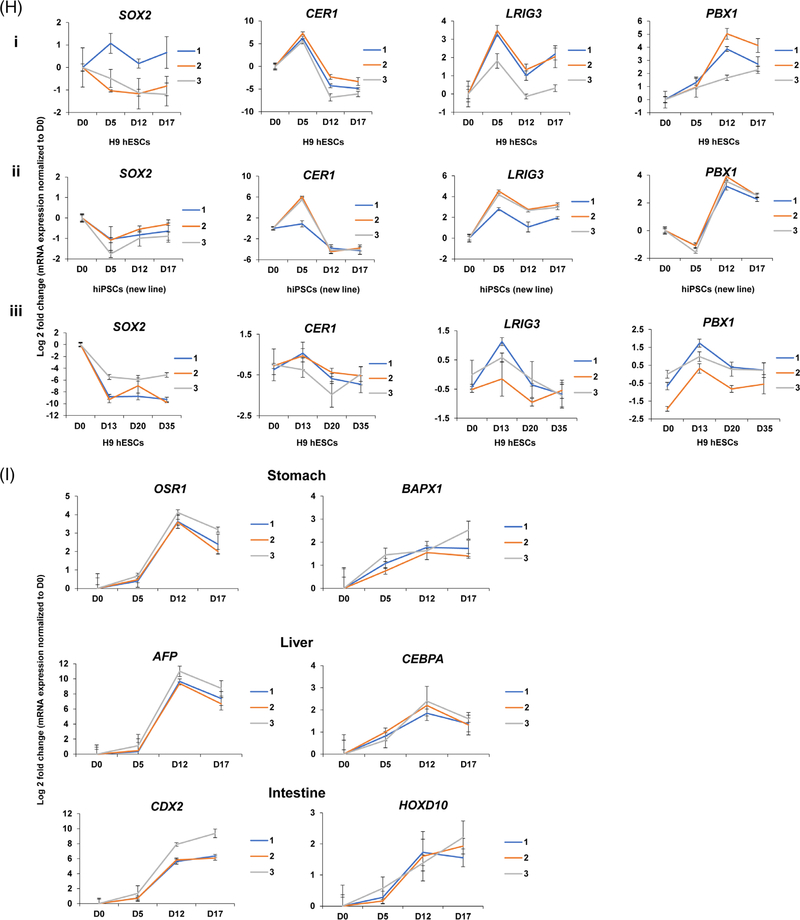

Next, we investigated the protein levels in pathways that are involved and modulated in the applied differentiation protocol, namely: TGF-β/Activin, Notch, Wnt, MAPK, PI3K-AKT, and BMP signaling pathways (Figure 1A). Pathway analysis revealed time course changes in the activation profiles of these canonical signaling networks (Supplementary Table S3). Specification of pancreatic maturation was maintained through a combination of factors, including TGF-β, RA, and FGF.36 In addition, stimulation by Activin A was required for induction of endoderm, as reflected by the observed activation of TGF-β at days 5 and 12. This is in contrast to the subsequent inhibition of TGF-β that was necessary for endocrine lineage commitment, as observed by reduced z-score between days 12 and 17 (Figure 4B). The BMP pathway inhibited pancreas specification in foregut endoderm,37 suggesting that suppression of BMP signaling in foregut cells was required for pancreatic fate determination. This was consistent with our results in which BMP signaling was inhibited at day 12 of differentiation (Figure 3A). Phosphorylation level of SMAD2 (downstream target of TGF-β) was reduced after day 5 of differentiation, as confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 3B). We also observed reduced phospho-SMAD1/5/9 (downstream component of the BMP pathway) (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Regulation levels of target pathways of the differentiation protocol. A, The figure shows activation profiles (z-score) of PI3K-AKT, TGF-β, MAPK, WNT, NOTCH, and BMP signaling pathways according to the differentiation protocol comparing the proteome of human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) to that of cells differentiated until days 5, days 5 to 12, and days 12 to 17, respectively. The x-axis shows the time points of differentiation and the y-axis display the z-score. The z-score is given by the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software, which predicts predict activated pathways (positive z-score) or inhibited pathways (negative z-scores) of each canonical pathway based on the relative abundance of all proteins in the given pathway at a given time point. B, Phosphorylation level of SMAD2 (downstream target of TGF-β) and SMAD1/5/9 (downstream component of the BMP pathway) and the total SMAD2 and total SMAD1 during pancreatic progenitor differentiation were assessed by Western blotting

A morphogen-like role for FGF signaling has also been suggested for early pancreas differentiation, in which intermediate levels of FGF2 can induce the formation of PDX1+ cells.38 Our data suggested that FGF signaling is inhibited at day 12 of differentiation (Supplementary Table S3). A low Wnt/β-catenin signaling environment is required for foregut development39 and was consistent with inhibition of Wnt signaling at day 12 (Figure 3A). The Notch pathway is a negative regulator of Neurogenin 3 (NGN3), suggesting that suppression of Notch is required for the generation of NGN3+ cells.40 Consistently, our proteomics data showed inhibition of the Notch pathway that was maintained throughout the 17 days of early pancreatic differentiation (Figure 3A). We could not detect a corresponding increase in NGN3 protein levels, which probably was beneficial up to the pancreatic progenitor stage (day 17), after which NGN3 becomes necessary for endocrine lineage commitment and the generation of mono-hormonal cells.6

Our findings indicated that careful time course profiling of proteome changes during hPSC differentiation is a reliable approach to assess the downstream proteome adaptations to treatments with the small molecules and growth factors used in the differentiation protocol.

3.3 |. Profiling dynamic signaling network during pancreatic differentiation

To classify the temporal proteome dynamic data set into canonical signaling pathways, we compared protein abundances on day 5 vs day 0, day 12 vs day 5, and day 17 vs day 12 cells, and performed an unbiased pathway analysis using the software Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software. IPA predicts activated pathways (positive z-scores) or inhibited pathways (negative z-scores) based on the relative abundance of all proteins in the given pathway at a given time point. We identified similar dynamic patterns of groups of pathways. The complete list of the canonical signaling pathways is found in Supplementary Table S3. Our quantitative data set mapped to a total of 162 canonical signaling pathways. These data allowed us to study the activation profiles of well-known signaling events important for pancreatic differentiation, as well as to identify other signaling pathways that were regulated simultaneously in these differentiating cells.

The hPSC-stage (D0) was characterized by increased OCT4 and NANOG expressions, which would decrease after the cells had differentiated toward definitive endoderm (Figure 4A). TGF-β, Notch, PI3K-AKT, mTOR, CXCR4, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways were all activated at the start of differentiation (positive z-score at day 5 compared to day 0), followed by a subsequent negative z-score in the cell populations at days 12 and 17 (Figure 4B). This suggests that the inhibition of TGF-β, Notch, PI3K-AKT, mTOR, CXCR4, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling occurs after the establishment of definitive endoderm.

Another interesting pathway activation profile was observed for epidermal (EGF), hepatocyte (HGF), and fibroblast growth factors (FGF). This group of signaling events showed positive z-scores at the start of differentiation followed by negative z-scores in cells differentiated until day 17 (Figure 4C). VEGF, PTEN, and calcium signaling showed increased activity in pancreatic progenitors (Figure 4D). This unbiased pathway analysis revealed groups of pathways whose activity profiles correlate with that of well-known signaling events that are important for pancreatic development.41–44

Interestingly, the most pronounced differential regulation comparing temporal proteome dynamics between days 5 and 0, days 12 and 5, and day 17 compared to day 12 was evident for the Hippo pathway (Figure 4E). Studies on Hippo signaling in the developing pancreas have reported that the key proteins, TEAD1 together with YAP1, activate important pancreatic signaling factors, and regulate the expansion of pancreatic progenitors.45 With our unbiased pathway analysis, we report how in-depth quantitative proteomics could be a useful validation tool and possibly a hypothesis-generating tool for future studies.

The abundance of TEAD1 and YAP1 was further validated by gene expression analysis using two dissimilar differentiation protocols that generate pancreatic progenitors, namely: (a) monolayer13,34 and (b) Pagliuca et al.7 We found similarly increased expression profiles in pancreatic progenitor cells, particularly at days 12 and 17 of protocol (a) and at day 13 of protocol (b) (Figure 4F). TEAD1 and YAP1 showed the highest expression at day 13, and also showed a moderate increase in SC-β cells (day 35). Western blot analyses showed increasing expression of TEAD1 protein, with a peak expression on day 17, whereas YAP1 protein did not appear to increase significantly (Figure 4G). We also investigated the protein level of TEAD1 and YAP1 in adult human islets. In our previously reported proteomics characterization46 of stage 6 (S6) and stage 7 (S7) cells (corresponding to immature and maturing β-like cells),6 TEAD1 and YAP1 showed decreased abundance in adult human islets as compared to S6 and S7 cells. These findings could suggest an important function of Hippo signaling involved in early pancreas differentiation in vitro.

In the present pilot study, we report the potential of in-depth proteome characterization of cells during the intermediate stages of directed differentiation. The data reveal thousands of proteins that change simultaneously whereas the hiPSCs alter their cell fate and include a previously unidentified potential role for the Hippo pathway in early pancreatic differentiation. We propose that quantitative proteomics is a useful tool for further understanding of the pancreas differentiation process.

4 |. DISCUSSION

The paucity of human islets for diabetes treatment has prompted a massive endeavor to employ hESCs and hiPSCs as a renewable source of insulin-producing cells.47 Likewise, differentiated, multipotent pancreatic progenitors become essential in the modeling of early pancreas development as these cells can be directed to produce glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vitro6,7 and in vivo.8,9 Understanding the molecular processes underlying the functional specification of hPSCs during their differentiation is, therefore, of paramount importance for the field of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine. Using unbiased quantitative proteomics, which allow the simultaneous profiling of ~7000 proteins during hiPSC differentiation, we have presented a large-scale proteomic profiling of in vitro pancreatic differentiation of hiPSCs. In addition, we have also mapped the activation profiles of known signaling pathways, as well as discover signaling events and novel molecular signatures of early pancreatic differentiation, including a potential regulatory role of the Hippo signaling pathway.

Significant advances have been made over the past decade recapitulating pancreatic development in vitro using hESCs and hiPSCs, using the extensive knowledge gained from studies of pancreatic organogenesis in model organisms.44,48 As previously described, many of the signaling pathways important in the developing pancreas are well-defined and include TGF-β, Notch, Wnt/β-catenin, Shh, BMP, FGF, and EGF pathways.41–44 A recent study identified the bipotent pancreatic progenitor fate to be regulated by integrin α5 acting via the F-actin-YAP1-Notch mechanosignaling axis.49 Notably, the role of Hippo signaling for pancreas development has not been fully explored. Using human embryonic pancreas and ESC-derived progenitors, TEAD1 and the coactivator YAP1 were recognized to activate key regulatory genes and to promote the development of pancreatic multipotent progenitors.45 Consistent with these finding, the canonical pathway of Hippo signaling showed the most pronounced differential regulation in our proteomics data set, in which the protein levels of both TEAD1 and YAP1 were increased in pancreatic progenitors. Previous studies have shown that the Hippo signaling effector protein YAP1 is lost following endocrine specification in mice,50 and that YAP1 is undetectable in adult pancreatic islets. In another study, differentiation of stem cell-derived insulin producing β cells is further enhanced by YAP1 inhibition.51 Consistent with these reports, we also found a reduced expression of both TEAD1 and YAP1 in the proteome of adult human islets as compared to immature β-like cells (S6) and maturing β-like cells (S7). Considering the Hippo pathway is also known to integrate signals from Notch, TGF-β, and Wnt signaling,52–54 our findings suggest that the molecular fingerprint of pancreatic differentiation includes complex protein interactions that remain to be determined.

Interestingly, our data suggest that the activation of Notch, TGF-β, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway shows similar dynamic patterns following early pancreatic progenitor differentiation. Previous studies reported that TGF-β signaling inhibits the differentiation of pancreatic progenitors into the endocrine lineage55,56; our study indicates the inactivation of TGF-β signaling from day 12 of the in vitro differentiation protocol,11,12,57 suggesting a loss of the inhibitory role of TGF-β signaling for further differentiation of these cells toward the endocrine specification. The canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway has a known role in endoderm patterning, and a low Wnt/β-catenin signaling environment is required for foregut development.39 Our data showed low Wnt/β-catenin signaling in definitive endoderm cells, followed by their inhibition in cell populations differentiated until days 12 and 17. The Notch pathway is a negative regulator of Neurogenin 3 (NGN3), suggesting that inhibition of Notch is required for the generation of NGN3+ cells.40 Consistent with this, our proteomics data showed that the inhibition of Notch was maintained throughout the 17 days of early pancreatic differentiation. Comparable activation profile of Hippo signaling with the Notch, TGF-β, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways therefore argues for their collective roles during pancreas differentiation.

There are many approaches to quantitative proteomics including a similar study using a label-free approach reported recently.35 The latter approach is different in many aspects as compared to the TMT 10-plex labeling that we report. Label-free proteomics allows for analysis of multiple samples that are analyzed separately and the procedure is sensitive to variations in sample processing and LC-MS analysis. On the other hand, in the TMT-labeling approach, peptides in 10 samples are labeled with isobaric mass tags and then combined so that downstream experimental conditions are similar for all samples. This approach also allows for sample fractionation to increase proteome coverage. Using the TMT 10-plex labeling, we applied stringent criteria for data analysis with 1% FDR, protein identification required two or more unique peptides, and the unique peptides for each protein needed to be detected in each sample. Low abundance proteins, such as the transcription factors SOX17, PDX1, NKX6.1, and PTF1A that are expected to be expressed in a stage-specific manner in differentiating cells, may therefore not be detected. Since we combined hiPSCs and pancreatic progenitors, the signal from a protein with low abundance would also end up being diluted using the TMT-labeling approach as compared to the label-free approach.

5 |. SUMMARY

The signaling pathways and molecular signatures that are necessary to generate the progenitor cells of in vivo pancreas development are not fully characterized yet.9 hPSC differentiation can be used to derive cellular populations that express organ-specific progenitor markers; however, it is unclear if such cells truly recapitulate the molecular signatures of naturally occurring progenitor cells. Therefore, characterizations of the proteome, such as that presented in this study, warrant continued research in order to unravel the key signaling pathways, establish their relationships to each other, and their interactions with the core transcription factor networks regulating pancreatic progenitor cell fate decisions.

Supplementary Material

Significance statement.

Quantitative proteomic profiling of early proteome adaptations during human pluripotent stem cell differentiation toward pancreatic progenitors is presented. In this study, the activation profiles of known signaling pathways were mapped at various stages during early pancreatic differentiation, resulting in the discovery of signaling events and novel molecular signatures, including a potential regulatory role for the Hippo signaling pathway during early pancreatic differentiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

L.S.W.L. is supported by an A*STAR Graduate Scholarship. A.K.K.T. is supported by the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology (IMCB), A*STAR, A*STAR JCO Career Development Award (CDA) 15302FG148, NMRC/OFYIRG/018/2016-00, A*STAR ETPL Gap Funding ETPL/18-GAP005-R20H, Lee Foundation Grant SHTX/LFG/002/2018, Skin Innovation Grant SIG18011, NMRC OF-LCG/DYNAMO, FY2019 SingHealth Duke-NUS Surgery Academic Clinical Programme Research Support Programme Grant, Precision Medicine and Personalised Therapeutics Joint Research Grant 2019, SingHealth Duke-NUS Transplant Centre – Multi-Visceral Transplant Fund Award and the Industry Alignment Fund – Industry Collaboration Project (IAF-ICP). This work was also supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant R01 DK67536, the Harvard Stem Cell Institute (R.N.K.), NIH/NIDDK grant K01 DK098285 (J.A.P.), Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI), and a U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant F31DK098931 (I.A.V), Western Norway Regional Health Authority, Diabetesforbundet, Bergen Research Foundation, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation (H.R.), Norsk Endokrinologisk forenings reisestipend, Diabetesforbundet, and Inger R. Haldorsens legat (H.V.).

Funding information

Agency for Science, Technology and Research; Inger R. Haldorsens legat; Norsk Endokrinologisk forenings reisestipend; Novo Nordisk Foundation; Bergen Research Foundation; Diabetesforbundet; Western Norway Regional Health Authority; U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), Grant/Award Number: F31DK098931; Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI); NIH/NIDDK, Grant/Award Number: K01 DK098285; Harvard Stem Cell Institute (R.N.K.); National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: R01 DK67536

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robinton DA, Daley GQ. The promise of induced pluripotent stem cells in research and therapy. Nature. 2012;481:295–305. 10.1038/nature10761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussein SM, Puri MC, Tonge PD, et al. Genome-wide characterization of the routes to pluripotency. Nature. 2014;516:198–206. 10.1038/nature14046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu SM, Hochedlinger K. Harnessing the potential of induced pluripotent stem cells for regenerative medicine. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:497505 10.1038/ncb0511-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loo LSW, Lau HH, Jasmen JB, Lim CS, Teo AKK. An arduous journey from human pluripotent stem cells to functional pancreatic beta cells. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:3–13. 10.1111/dom.12996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teo AK, Wagers AJ, Kulkarni RN. New opportunities: harnessing induced pluripotency for discovery in diabetes and metabolism. Cell Metab. 2013;18:775–791. 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rezania A, Bruin JE, Arora P, et al. Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1121–1133. 10.1038/nbt.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pagliuca FW, Millman JR, Gurtler M, et al. Generation of functional human pancreatic beta cells in vitro. Cell. 2014;159:428–439. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroon E, Martinson LA, Kadoya K, et al. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:443–452. 10.1038/nbt1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agulnick AD, Ambruzs DM, Moorman MA, et al. Insulin-producing endocrine cells differentiated in vitro from human embryonic stem cells function in macroencapsulation devices in vivo. STEM CELLS TRANSLA-TIONAL MEDICINE. 2015;4:1214–1222. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.5966/SCTM.2015-0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teo AK, Windmueller R, Johansson BB, et al. Derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with maturity onset diabetes of the young. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:5353–5356. 10.1074/jbc.C112.428979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teo AK, Valdez IA, Dirice E, Kulkarni RN. Comparable generation of activin-induced definitive endoderm via additive Wnt or BMP signaling in absence of serum. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:5–14. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teo AK, Tsuneyoshi N, Hoon S, et al. PDX1 binds and represses hepatic genes to ensure robust pancreatic commitment in differentiating human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:578–590. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng HJN, Jasmen BJ, Lim CS, et al. HNF4A haploinsufficiency in MODY1 abrogates liver and pancreas differentiation from patient-derived iPSCs. iScience. 2019;16:192–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paulo JA, Gygi SP. A comprehensive proteomic and phosphor-proteomic analysis of yeast deletion mutants of 14–3-3 orthologs and associated effects of rapamycin. Proteomics. 2015;15:474–486. 10.1002/pmic.201400155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McAlister GC, Nusinow DP, Jedrychowski MP, et al. MultiNotch MS3 enables accurate, sensitive, and multiplexed detection of differential expression across cancer cell line proteomes. Anal Chem. 2014;86: 7150–7158. 10.1021/ac502040v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chambers MC, Maclean B, Burke R, et al. A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:918–920. 10.1038/nbt.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craig R, Beavis RC. TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1466–1467. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabb DL, Fernando CG, Chambers MC. MyriMatch: highly accurate tandem mass spectral peptide identification by multivariate hypergeometric analysis. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:654–661. 10.1021/pr0604054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorfer V, Pichler P, Stranzl T, et al. MS Amanda, a universal identification algorithm optimized for high accuracy tandem mass spectra. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:3679–3684. 10.1021/pr500202e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S, Pevzner PA. MS-GF+ makes progress towards a universal database search tool for proteomics. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5277 10.1038/ncomms6277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eng JK, Jahan TA, Hoopmann MR. Comet: an open-source MS/MS sequence database search tool. Proteomics. 2013;13:22–24. 10.1002/pmic.201200439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geer LY, Markey SP, Kowalak JA, et al. Open mass spectrometry search algorithm. J Proteome Res. 2004;3:958–964. 10.1021/pr0499491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaudel M, Barsnes H, Berven FS, Sickmann A, Martens L. SearchGUI: an open-source graphical user interface for simultaneous OMSSA and X!Tandem searches. Proteomics. 2011;11:996–999. 10.1002/pmic.201000595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaudel M, Burkhart JM, Zahedi RP, et al. PeptideShaker enables reanalysis of MS-derived proteomics data sets. Nat Biotechnol. 2015; 33:22–24. 10.1038/nbt.3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;604:55–71. 10.1007/978-1-60761-444-9_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nesvizhskii AI. A survey of computational methods and error rate estimation procedures for peptide and protein identification in shotgun proteomics. J Proteomics. 2010;73:2092–2123. 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nesvizhskii AI, Aebersold R. Interpretation of shotgun proteomic data: the protein inference problem. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4: 1419–1440. 10.1074/mcp.R500012-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vizcaino JA, Deutsch EW, Wang R, et al. ProteomeXchange provides globally coordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat Biotech. 2014;32:223–226. 10.1038/nbt.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vizcaino JA, Cote RG, Csordas A, et al. The PRoteomics IDEntifications (PRIDE) database and associated tools: status in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1063–D1069. 10.1093/nar/gks1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martens L, Hermjakob H, Jones P, et al. PRIDE: the proteomics identifications database. Proteomics. 2005;5:3537–3545. 10.1002/pmic.200401303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaudel M, Sickmann A, Martens L. Peptide and protein quantification: a map of the minefield. Proteomics. 2010;10:650–670. 10.1002/pmic.200900481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaudel M, Sickmann A, Martens L. Introduction to opportunities and pitfalls in functional mass spectrometry based proteomics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1844:12–20. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burkhart JM, Vaudel M, Zahedi RP, Martens L, Sickmann A. iTRAQ protein quantification: a quality-controlled workflow. Proteomics. 2011;11:1125–1134. 10.1002/pmic.201000711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teo AK, Lau HH, Valdez IA, et al. Early developmental perturbations in a human stem cell model of MODY5/HNF1B pancreatic hypoplasia. Stem Cell Reports. 2016;6:357–367. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haller C, Chaskar P, Piccand J, et al. Insights into islet differentiation and maturation through proteomic characterization of a human iPSC-derived pancreatic endocrine model. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2018;12: e1600173 10.1002/prca.201600173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spence JR, Wells JM. Translational embryology: using embryonic principles to generate pancreatic endocrine cells from embryonic stem cells. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3218–3227. 10.1002/dvdy.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossi JM, Dunn NR, Hogan BL, Zaret KS. Distinct mesodermal signals, including BMPs from the septum transversum mesenchyme, are required in combination for hepatogenesis from the endoderm. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1998–2009. 10.1101/gad.904601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ameri J, Stahlberg A, Pedersen J, et al. FGF2 specifies hESC-derived definitive endoderm into foregut/midgut cell lineages in a concentration-dependent manner. STEM CELLS. 2010;28:45–56. 10.1002/stem.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Rankin SA, Sinner D, Kenny AP, Krieg PA, Zorn AM. Sfrp5 coordinates foregut specification and morphogenesis by antagonizing both canonical and noncanonical Wnt11 signaling. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3050–3063. 10.1101/gad.1687308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Apelqvist A, Li H, Sommer L, et al. Notch signalling controls pancreatic cell differentiation. Nature. 1999;400:877–881. 10.1038/23716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim SK, Hebrok M. Intercellular signals regulating pancreas development and function. Genes Dev. 2001;15:111–127. 10.1101/gad.859401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oliver-Krasinski JM, Stoffers DA. On the origin of the beta cell. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1998–2021. 10.1101/gad.1670808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCracken KW, Wells JM. Molecular pathways controlling pancreas induction. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:656–662. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pagliuca FW, Melton DA. How to make a functional beta-cell. Development. 2013;140:2472–2483. 10.1242/dev.093187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cebola I, Rodriguez-Segui SA, Cho CH, et al. TEAD and YAP regulate the enhancer network of human embryonic pancreatic progenitors. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:615–626. 10.1038/ncb3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vethe H, Bjorlykke Y, Ghila LM, et al. Probing the missing mature beta-cell proteomic landscape in differentiating patient iPSC-derived cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4780 10.1038/s41598-017-04979-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo T, Hebrok M. Stem cells to pancreatic beta-cells: new sources for diabetes cell therapy. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:214–227. 10.1210/er.2009-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santosa MM, Low BS, Pek NM, Teo AK. Knowledge gaps in rodent pancreas biology: taking human pluripotent stem cell-derived pancreatic beta cells into our own hands. Front Endocrinol. 2015;6:194 10.3389/fendo.2015.00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mamidi A, Prawiro C, Seymour PA, et al. Mechanosignalling via integrins directs fate decisions of pancreatic progenitors. Nature. 2018;564:114–118. 10.1038/s41586-018-0762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.George NM, Day CE, Boerner BP, Johnson RL, Sarvetnick NE. Hippo signaling regulates pancreas development through inactivation of Yap. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:5116–5128. 10.1128/MCB.01034-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosado-Olivieri EA, Anderson K, Kenty JH, Melton DA. YAP inhibition enhances the differentiation of functional stem cell-derived insulin-producing beta cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1464 10.1038/s41467-019-09404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu J, Poulton J, Huang YC, Deng WM. The hippo pathway promotes Notch signaling in regulation of cell differentiation, proliferation, and oocyte polarity. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1761 10.1371/journal.pone.0001761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Irvine KD. Integration of intercellular signaling through the Hippo pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:812–817. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mauviel A, Nallet-Staub F, Varelas X. Integrating developmental signals: a Hippo in the (path)way. Oncogene. 2012;31:1743–1756. 10.1038/onc.2011.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nostro MC, Sarangi F, Ogawa S, et al. Stage-specific signaling through TGFbeta family members and WNT regulates patterning and pancreatic specification of human pluripotent stem cells. Development. 2011;138:861–871. 10.1242/dev.055236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rezania A, Riedel MJ, Wideman RD, et al. Production of functional glucagon-secreting alpha-cells from human embryonic stem cells. Diabetes. 2011;60:239–247. 10.2337/db10-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teo AK, Ali Y, Wong KY, et al. Activin and BMP4 synergistically promote formation of definitive endoderm in human embryonic stem cells. STEM CELLS. 2012;30:631–642. 10.1002/stem.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.