Abstract

Abnormal neurochemical signaling is often the underlying cause of brain disorders. Electrochemical microsensors are widely used to monitor neurochemicals with high spatial-temporal resolution. However, they rely on carbon fiber microelectrodes that often limit their sensing performance. In this study, we demonstrate the potential of a hybrid multiwall carbon nanotube (MWCNT) film modified boron-doped ultrananocrystalline diamond (UNCD) microelectrode (250 μm diameter) microsensor for improved detection of dopamine (DA) in the presence of common interferents. A series of modified microelectrodes with varying film thicknesses were microfabricated by electrophoretic deposition (EPD) and characterized by scanning electron microscopy, x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and silver deposition imaging. Using cyclic voltammetry, the 100-nm “thin” film microelectrode produced the most favorable combination of DA sensitivity value of 36 ±2% μA/μM/cm2 with a linear range of 33 nM to 1 μM and a limit of detection (LOD) of 9.5 ± 1.2% nM. The EIS spectra of these microelectrodes revealed three regions with inhomogeneous pore geometry and differing impedance values and electrochemical activity, which was found to be film thickness dependent. Using differential pulse voltammetry, the modified microelectrode showed excellent selectivity by exhibiting three distinct peaks for the DA, serotonin and excess ascorbic acid in a ternary mixture. These results provide two key benefits: first, remarkable improvements in DA sensitivity (>125-fold), selectivity (>2000-fold) and LOD (>180-fold), second, these MWCNTs can be selectively coated with a simple, scalable and low cost EPD process for highly multiplexed microsensor technologies. These advances offer considerable promise for further progress in chemical neurosciences.

Keywords: Nanocrystalline diamond, Carbon nanotube, Microelectrode, Dopamine, Sensitivity, Impedance spectroscopy

1. Introduction

Neurochemical monitoring is a critical tool for identifying the neural basis of human behavior and treating brain disorders. Studies have shown that abnormal neurochemical signaling is often the underlying cause of brain disorders such as epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury and drug addiction [1,2]. Hence, to treat such brain disorders, it is important to quantify the dynamics of such neurochemicals as dopamine (DA), glutamate, GABA, adenosine and serotonin (HT-5). Among these neurochemicals, DA is an important catecholamine in the mammalian central nervous system [3] because it is a central player in the brain “reward” system, and also plays a critical role in various bodily functions, i.e. motor control, motivation and cognition and in several debilitating neuropathologies [1,4]. Levels of HT-5 are linked to depression, addiction and other functions ranging from appetite to sleep [5]. Since DA and HT-5 are electrochemically active, they are readily measured using electrochemical techniques such as fast scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) and amperometry techniques with excellent spatial (micron range) and temporal (sub-second range) resolution in vitro and in vivo [6]. These methods routinely use carbon fiber microelectrodes (CFM) and glassy carbon electrodes (GCE) with sub-micromolar sensitivity [7,8]. One of the grand challenges in this field is to develop a highly multiplexed microelectrode array (MEA) microsensor with a minimal footprint in order to detect many neurochemicals simultaneously with high sensitivity and high selectivity for a meaningful understanding of brain function and brain disorder mechanisms [9]. This requires the integration of multiple ultra-small microelectrodes into an array on a single chip. The main disadvantage of the use of ultra-small microelectrodes are that they have reduced electroactive surface area, with limited availability of DA adsorption sites and edge plane graphite sites, which results in poor sensitivity [10]. Several research groups have demonstrated high sensitivity by employing flame etching, laser ablation and electrochemical pretreatments (e.g. extended waveforms, overoxidation) that alter the microelectrode’s surface charge [8,11–13]. However, the pretreatments are generally short-lived due to electrode loss from chemical etching [14]. Additionally, traditional electrode materials used to develop ultra-small microelectrodes lack selectivity. For example, DA and HT-5 have similar oxidation potentials (E0), since their E0 varies by less than 150 mV (i.e. E0 (DA) = 200 mV, E0 (HT-5) = 320mV vs. Ag/AgCl) and many electrodes cannot distinguish them in the presence of ascorbic acid (AA) that is also present in the brain at much higher (100–1000 fold) concentrations [15–17]. Polymer coatings (e.g. nafion) are now routinely used to block anionic molecules such as AA but they increase the response time of analyte measurements [18]. This twofold problem of achieving high sensitivity and high selectivity can be addressed by employing carbon nanotube (CNT)-enabled three-dimensional microelectrode scaffolds that could significantly increase the electroactive/adsorption sites for higher sensitivity and electrocatalytic/defect rich sites for higher selectivity detection. CNTs have been used to modify CFMs, graphite, GCE, carbon paste and diamond-like carbon (DLC) to increase DA adsorption sites, decrease oxidation overpotentials and improve sensitivity [4,8,19–21]. For example, Sainio et al., developed a complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor compatible DLC- multi walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) macro composite electrode. The MWCNTs were grown directly on top of a DLC film and exhibited reversible charge transfer kinetics and 500 nM DA detection sensitivity as compared to a 10 μM sensitivity for a bare DLC electrode [4]. Other groups have used nafion/CNT coatings on modified GCEs for detecting low concentrations of DA in the presence of AA and uric acid [8].

In this study, we have microfabricated and fully characterized a hybrid MWCNT film modified boron-doped ultrananocrystalline diamond (UNCD) microelectrode for DA detection in the presence of 5-HT and AA. The UNCD thin film was chosen as the bare microelectrode material because of its unique nanoscale structure - ultra-small equiaxed grains (2–5 nm diameter) and inherently ultra-smooth surface (Ra of ~5–8nm rms, root mean square) and excellent electrochemical properties - superior chemical inertness and dimensional stability, wide electrochemical potential window, extremely low background currents, and exceptional biocompatibility for brain chemical sensing [1,22,23]. Several groups including ours have used microlithographic techniques to produce well- defined, reproducible microelectrode geometries on conductive diamond films and wires for in vitro and in vivo neurochemical measurements [17,24–28]. MWCNT was chosen as a modifying layer for the UNCD because of its ballistic electronic properties, high surface area, excellent interfacial adsorption properties and enhanced electrocatalytic activity. Several techniques have been employed previously to modify surfaces with CNTs, namely, Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD), drop casting and electrophoretic deposition (EPD) [29,30]. CVD processes are quite expensive - involving cumbersome microfabrication processes, costly cleanroom equipment and high temperature growth processes that severely limit the electrode and electrode substrate material choices [30–32]. Drop casting neither controls the thickness nor achieves a highly selective, uniform coating thickness on microelectrode surfaces [30]. However, EPD is well suited to deposit charged particles like CNTs with highly controllable coating thicknesses and precise integration of the coating on microelectrodes [33]. In this work, MWCNTs of varying thicknesses (100–500 nm) on 250 pm diameter UNCD microelectrodes were selectively deposited using EPD. For the first time, the effect of MWCNT film coatings on the electrochemical characteristics of a conductive UNCD microelectrode (sensitivity, selectivity, electrode-reaction kinetics, S/N ratio, limits of detection, film stability) have been quantitatively assessed via the detection of DA with this novel sensing technology. Cyclic voltammetry (CV), Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), silver (Ag) deposition imaging (SDI) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) techniques were used to develop a detailed understanding of this new class of MWCNT modified diamond microelectrodes for neurochemical detection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. UNCD microelectrode MEA microfabrication

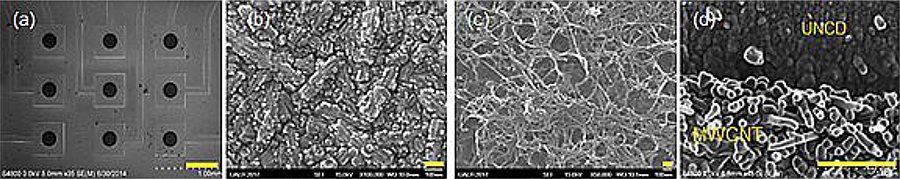

The substrates employed for these microelectrodes were four inch silicon wafers with a 1-μm thick thermal SiO2 (Wafer World Inc.) surface coating. A 2 μm thick boron-doped UNCD film was then deposited with a Hot Filament Chemical Vapor Deposition (HFCVD) process from Advanced Diamond Technologies, Inc (Romeoville, IL, USA) [34–37]. The UNCD film resistivity was ~0.08 Ω·cm as measured by a 4-point probe from a witness wafer (Pro4, Lucas Labs, Gilroy, CA). The average roughness of the UNCD film was <10 nm rms based on AFM measurements (Digital Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA). Optical microlithography was used to pattern 21 chips per wafer. Each chip was micro patterned into nine individually electrically addressable 250 μm disk microelectrodes (~0.05 mm2 geometrical area) in a 3 × 3 microelectrode array (MEA) format, shown in Fig. 1a and b (details described elsewhere) [10,34].

Fig. 1.

SEM images showing (a) a 3 × 3 microarray with nine individually addressable 250-μm UNCD microelectrodes. (b, c) an unmodified UNCD and MWCNT-modified UNCD microelectrode at higher magnification, respectively. (d) Cross-sectional view of the MWCNT modified microelectrode interface. Scale bars for (a-d) are 500 μm, 100nm, 100nm and 1 μm, respectively.

2.2. Reagents and chemicals

All chemicals were reagent grade and purchased from Sigma Aldrich Chemical Co. The chemicals were used as received unless otherwise specified. Deionized (DI) water was prepared using a three-filter purification system from Continental Water Systems (Modulab DI recirculator, service deionization polisher).

2.3. EPD process

A 1 mg/mL MWCNT suspension in DI water (PD15L-5–20, OD: 15 ± 5nm, Length: 1–5 μm, 5% —COOH functionalized) was purchased from Nanolab, Inc (Waltham, MA). The MWCNT consists of 98.92%wt carbon, 0.14% sulfur and 0.94% iron based the EDAX data from the supplier. Before EPD, a 5 μM MgCl2 −6H2 O salt solution was added to the MWCNT suspension and sonicated for 30 min. This imparted a positive charge to the MWCNTs [33,38]. A 3 × 3 UNCD MEA was placed on a custom cell with a ~1.5 mm spacing from the counter electrode (platinum wire, Alfa Aesar). A ~30 μL MWCNT suspension was placed between the UNCD chip and the Pt counter. A step-wise voltage scan (−3 V to −9V) was applied using Gamry reference 600 Potentiostat (Gamry instruments, Warminster, PA, USA) to the UNCD microelectrode for various time durations (0 s to 500 s) until MWCNTs of desired thicknesses were deposited. After the EPD process was completed, the chip was soaked in DI water for 5 min and then gently rinsed for 30 s to remove any non-specifically bound MWCNTs and chloride salt residues. Finally, the MWCNT- modified UNCD microelectrodes were dried in an oven at 50° C for 45 min (Fig. 1c and d).

2.4. Morphological and structural characterization

The surface morphology of the microelectrode was examined using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM: Hitachi S-4800). The film thickness was measured using SEM and surface profilometry (Dektak 150 stylus surface profiler, Veeco Instruments, NY, USA). In addition, the films were characterized by Raman spectroscopy (Control Development 2DMPP with λ:532 nm). The XPS studies were performed using Thermo scientific K-Alpha system with a base pressure of 5 × 10−9 mbar using the AlKα (1486.8 eV) X-ray monochromatized radiation with a pass energy of 50 eV (resolution: 0.5 eV). The peak fitting was carried out using the Thermo Avantage Data system. Ag particles were deposited on to the microelectrodes by applying a constant potential of −0.5V for 60s in a 3mM AgNO3/0.01M perchloric acid solution.

2.5. Electrochemical measurements

All electrochemical experiments were carried out with an Autolab potentiostat (PGSTAT 302N, Metrohm USA) configured in a three-electrode setup using a Pt coil (Alfa Aesar) counter electrode and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE, Accumet, New Hampshire, USA) as the reference electrode. The potentiostat was equipped with a Frequency Response Analyzer 2, ECD and Multiplex modules and Nova 1.10.3 software. The microelectrode was configured as the working electrode. The microelectrode surfaces were exposed to the analyte or electrolyte solutions and sealed with a 4mm diameter O-ring in a custom micro fabricated Teflon cell. For each MEA chip, the electrical isolation of the pads was measured using a two-point probe multimeter. This ensured the integrity of the SiO2 passivation, which is essential for stable electrochemical performance. Prior to characterization, the MEA was briefly sonicated in ethanol for 30 s and dried in nitrogen. Cyclic voltammograms were recorded between −0.2 V and +0.8 V vs. SCE with a scan rate of 100 mV/s. Differential pulse voltammograms were recored with a 20 mV modulation amplitude and 5 mV step potential. The EIS spectra were recorded between 100 kHz and 100 mHz with a 10 mV ac signal amplitude (rms value) at open circuit potential (OCP). The impedance data were analysed by applying a non-linear least squares fitting to the appropriate theoretical model represented by an equivalent electrical circuit. All measurements were conducted in solutions of 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6/5 mM K3Fe(CN)6 in 1 M KCl and 100 μM DA in 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS). All experiments were repeated at least 3 times using three different microelectrodes (n = 3) for more than one MEA chip. The cyclic voltammograms and the impedance spectra shown below are representative of this data. All solutions were freshly prepared on the same day that the experiments were conducted and purged with nitrogen gas for 5 min before use.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. EPD of MWCNTs on UNCD microelectrodes: effect of process parameters

Three EPD process parameters - voltage (−3V to −9V), deposition time (up to 500 s) and MWCNT concentration (0.5 mg/mL and 1 mg/mL) were controlled to study the MWCNT film coverage, film uniformity and film thickness (see supplementary information, Table S1). Excellent film coverage and film uniformity was observed at low MWCNT concentration (0.5 mg/mL), low voltage (−4.5 V) and longer deposition times (300 s to 500 s). High voltage (−9V) and high MWCNT concentration (1.0 mg/mL) resulted in thick, nonuniform films. Since a highly uniform continuous coverage of MWCNTs with a controllable thickness is important to reliable functioning of the microelectrode, lower voltage values (i.e. slower deposition rates), longer deposition times and low MWCNT concentration (i.e. better surface coverages) were selected for detailed characterization of the modified microelectrode. Fig. 1c and d illustrates the random and open pore structure of the MWCNT network within the modified film. Surface profilometry measurements showed an increase in average surface roughness from 9.5 nm rms for the UNCD (control surface) to 18 nm rms for the MWCNT thin film (n = 3, data not shown). This is expected since the randomly oriented 3D network of MWCNTs with open pores generated a rougher surface (Fig. 1 c and d). These measurements also show that careful control of this porous structure is necessary in order to obtain improved chemical sensing performance. A detailed discussion concerning the electrochemical properties of the modified microelectrodes is presented in the following sections.

Curve fitting of Raman data indicates that the UNCD is a mixture of sp3 diamond grains and unstructured sp3 and sp2 amorphous carbon grain boundaries, characterized by six D-band (disordered graphite) peaks and a G-band (crystalline graphite) peak at 1560 cm−1, (see supplementary information, Fig. 1Sa, Table S2 and the details within) [10,37,39,40]. D-band peaks from 1310 to 1355 cm−1 include a relatively weak peak at 1332 cm−1 for the phase pure diamond along with the 1350 cm−1 peak for graphite. A relatively low value of the ratio of the intenstity of the D1332 peak to the intenstity of G1560 peak (I(D1332)/I(G1560)) of 0.4 indicates that defects due to disorder in the film is less prevalent. The Raman spectrum of thin film modified microelectrode exhibited two intense broad D and G peaks (see supplementary information, Fig. 1Sb) [41]. Two G-peaks were observed at 1515 and 1590 cm−1. The absence of a radial breathing mode shows that the MWCNT diameter is greater than 2 nm, which is expected as per the MWCNT supplier’s datasheet. The D-band is related to vibrations of sp3 carbon atoms of defects and disorder from nanotubes [42]. The 1342 and 1350 cm−1 peaks correspond to distortion in the sp2 crystalline graphite structure. A high value of the I(D)1350/I(G)1590 ratio of 0.78 indicates the nanocrystalline graphitic nature of MWCNTs [41,42]. with a high level of disorder arising from surface defects that are due to the presence of oxygen functionalities. The exact nature of these surface functionalites and their effect on DA sensitivity, selectivity and electochemical activity was studied in more detail using CV, DPV, EIS, XPS and SDI techniques as enumerated in the following sections. The 500 cm−1 peak in thickest MWCNT film signifies a high purity and less defect prone MWCNT network [43] (see supplementary information, Fig. 1Sc). The 1163 cm−1 peak from C—H bending vibrations are attributed to aromatic rings present in the MWCNT [41]. The 1220 cm−1 peak is attributed to sp3 states of carbon demonstrating the disruption of the aromatic system of π-electrons and prominently present in —COOH functionalized CNTs such as those being employed here [41,44]. The other peaks are similar to those observed in the thin film microelectrode. A high value of I(D)1342/I(G)1511 of 1.1 indicates a higher degree of defects contributed by distorted sp2 graphitic structures [41,42].

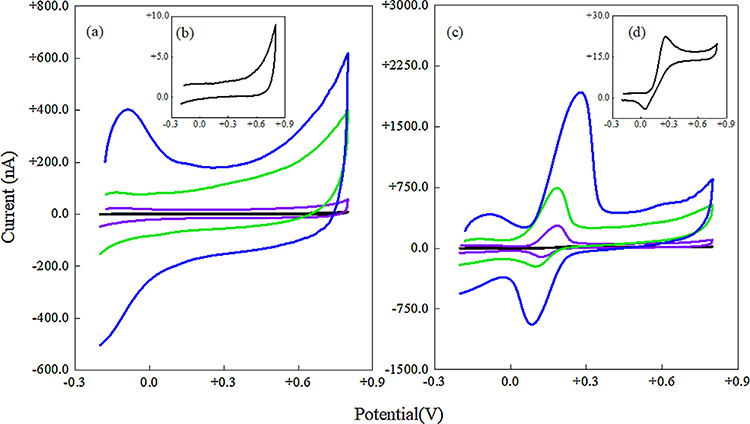

3.2. CV characterization of MWCNT modified UNCD microelectrodes: effect of MWCNT film thickness on DA sensor metrics – sensitivity, LOD, selectivity and stability

Fig. 2 shows the electrochemical response in 1X PBS (Fig. 2a and b) and 100 μM DA in 1X PBS (Fig. 2c and d) of the unmodified and MWCNT film modified UNCD microelectrodes used in this study. Based on the minimal variability in CV parameter values, excellent reproducibility in electrochemical signal strengths were observed for these microelectrodes. The% variation of the CV parameter values was 0–10% (n = 3) as derived from measurement of three different MEAs (Table 1). Sensitivity is defined as IS/[CDA × A], where IS is the forward peak current from the cyclic voltammograms at a scan rate of 100 mV/s (Fig. 2c and d), CDA is the DA concentration, which is 100 μM for this study and A is the geometrical area of the UNCD microelectrode, πR2, where R=125 μm is the radius of the UNCD microelectrode. Electrode reaction-kinetics data can be obtained from the peak potential separations (ΔEp) between the forward and reverse peak currents (Eanodic - Ecathodic) of the redox system. Studies show ΔEp and the associated slope of the cyclic voltammogram from inner and outer-sphere redox systems could be a reliable CV indicator to study electrode reaction rates [45,46]. S/N ratio is defined as the ratio of IS/Ic, where IC is the background or charging current recorded in 1X PBS buffer solution (Fig. 2a and b). The sensitivity was found to be critically dependent on MWCNT film thickness. When the MWCNT thickness increases from thin (~100 nm) to thickest (~500 nm), the sensitivity increased, the S/N ratio decreased and the electrode-reaction kinetics initially became more rapid and then slowed at increasing thickness. The charging current (IC) that is proportional to electrode area increased from 0.9 ± 2% nA (unmodified) to 170 ± 3% nA (thickest film), i.e. a 200-fold increase in electrode surface area. This is expected since MWCNT’s specific surface areas are very high and more MWCNTs are expected to be deposited at longer deposition times. Secondly, the ΔEp decreased 4-fold from 200 ±5% mV to 60 ± 4% mV when the UNCD was modified with a thin film. The lowest ΔEp value of 60 mV is still larger than the value corresponding to a reversible two electron redox process (which is 29.5 mV). This value slowly returned to 200 mV when the thickest film was deposited, which is the same value as that for the unmodified microelectrode. This ΔEp dependence on film thickness was previously observed with the presence of a porous MWCNT layer on top of a planar electrode [47,48]. This observed behavior is due to the geometrical and chemical effects of the modified electrode interface. The modified surface obviously provides a more porous geometry that significantly alters the diffusion behavior of the DA, as there will be a marked contribution from the thin liquid layer adjacent to the UNCD electrode surface. From a chemical standpoint, the modified electrode surface is dominated by carboxylic acid and oxygen functional groups (details in section 3.4) that are known to influence DA adsorption behavior [16]. It is also expected that the peak current will be higher for the modified microelectrode, as there is a relatively high electroactive electrode surface area within the porous MWCNT film. Thus, the peak current and ΔEp values should depend on the film thickness for the modified microelectrode. Thirdly, the DA peak currents increased from 13 ± 5% nA (unmodified) to 1650 ± 8% nA (thickest film), i.e. a 127-fold increase in sensitivity even with a constant value for the geometrical surface area of the UNCD microelectrode. Another advantage of the modified microelectrode is that the DA anodic peak shifts to less oxidative potentials, i.e. from +0.28 ± 5% V to +0.12 ± 3% V as the film thickness is reduced from ~500 nm to ~100 nm.

Fig. 2.

CV characterization of unmodified and MWCNT film modified UNCD microelectrodes. (a, b) Voitammograms taken in 1X PBS buffer (inset for UNCD). (c, d) Voltammograms obtained in 100 μM DA in 1X PBS (inset for UNCD). Legends: Unmodified UNCD (black curve), thin film (purple), thick film (green) and thickest film (blue). Scan rate is 100 mV/s. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 1.

Cyclic voltammetry data from the different MWCNT film modified UNCD microelectrodes and an unmodified UNCD (control). A 100 μM DA in 1X PBS buffer or 1X PBS buffer only was used. The scan rate is 100 mV/s. The background charging current (Ic) was computed from Figs. 3a and b. The dopamine signal (Is) was computed from Figs. 3c and d.

| Microelectrode type | ΔEp (mV) | Eanodic (mV) | Is (nA) | Ic (nA) | Sensitivity (μA/μMcm2) | S/N ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmodified UNCD (control) | 200 | 250 | 13 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 15 |

| Thin film | 60 | 200 | 240 | 16.5 | 5 | 15 |

| Thick film | 85 | 200 | 650 | 76 | 14 | 9 |

| Thickest film | 200 | 280 | 1650 | 170 | 32 | 9 |

The S/N ratio was high (S/N > 15) at the thin film microelectrode. This value is similar to that for an unmodified UNCD microelectrode, which is known to exhibit ultra-low charging currents and thus, a high S/N ratio. But the S/N ratio decreased from 15 to 9 as the film thickness was increased. The possible causes are explained using the EIS and XPS data discussed in the following sections. Table 2 shows a performance comparison between the modified microelectrode, a carbon fiber microelectrode (CFM) [39], the current “gold” standard for DA sensing and other CNT-modified electrodes as reported in the literature. Clearly, the MWCNT-modified UNCD microelectrodes demonstrate significant improvements in all performance metrics.

Table 2.

Comparison of MWCNT modified UNCD microelectrode performance with respect to others work involving electrodes with MWCNT modification in the literature. υ is the scan rate.

| Type of Electrode | Sensitivity (μA/μMcm2) | ΔEp (mV) | υ (mV/s) | S/N | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO-IL-MWCNT/GCE | 5.1 | 20 | 100 | <5 | Wang 2015 [64] |

| CNT/DLC | 2.2 | 26 | 50 | 10 | Sainio 2015 [4] |

| CNT/Au | 37 | 270 | 100 | <2 | Li 2014 [20] |

| SWCNT/CCE | 0.1 | 50 | 50 | <2 | Habibi 2010 [21] |

| Thin MWCNT-UNCD | 5 | 60 | 100 | 15 | This work |

| Thickest MWCNT-UNCD | 32 | 200 | 100 | 9 | This work |

| CFM | 1.1 | 83 | 100 | 6 | This work |

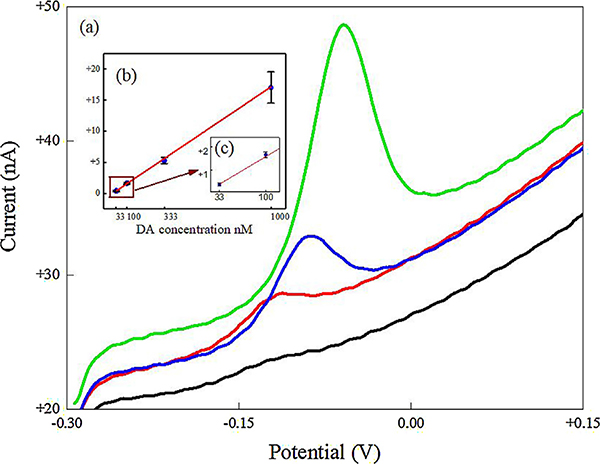

For evaluating the LOD, selectivity and film stability, thin film microelectrodes were chosen because of their near optimal combination of sensitivity, electrode-reaction kinetics and S/N ratio. Calibration curves were obtained from unmodified and thin film microelectrodes for different DA concentrations (1 nM - 100 μM) in 1X PBS buffer (n = 3). Thin film microelectrodes showed a linear range from 33 nM to 1 μM (correlation coefficient ~0.9996) with a sensitivity of 36 ± 2% μA μM−1 cm−2 (Fig. 3), which falls within the range required under physiological conditions. An anodic shift in the DA peak from ~ −120 mV to −60 mV was observed as the concentration was increased. This could be due to a shift from thin layer diffusion dominance to a thin layer – semi-infinite diffusion mechanism as DA concentration was increased. The unmodified microelectrodes showed a linear concentration dependence in the range from 1 μM to 100 μM (correlation coefficient ~0.999) with a sensitivity of 0.26 ± 5% μA μM−1 cm−2. LOD was calculated based on 3.3σ/S value reported in Sainio et al., [4] where c is the standard deviation of 16 measurements at DA’s oxidation potential from the blank CV voltammogram taken in 1X PBS (n = 3) and S is the sensitivity across the linear range. The LOD for thin film and unmodified microelectrodes are 9.5 ± 1.2% nM and 1.8 ± 5% μM, respectively, i.e. a 180-fold increase in LOD after MWCNT film modification.

Fig. 3.

LOD studies of MWCNT film modified UNCD microelectrodes. (a) Voltammograms showing only the forward scan is taken at different DA concentrations. Legends: 33 nM (black curve), 100 nM (red), 333 nM (blue) and 1 μM (green). Scan rate is 100 mV/s. (c) Linear fit between DA concentration and DA peak current. (d) Inset showing the fitting for lower DA concentrations. Linear fit parameters obtained:y = (0.018 ± 3.51 × 10−4) x + (2.66 ± 1.58);R2 = 0.9996.(For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

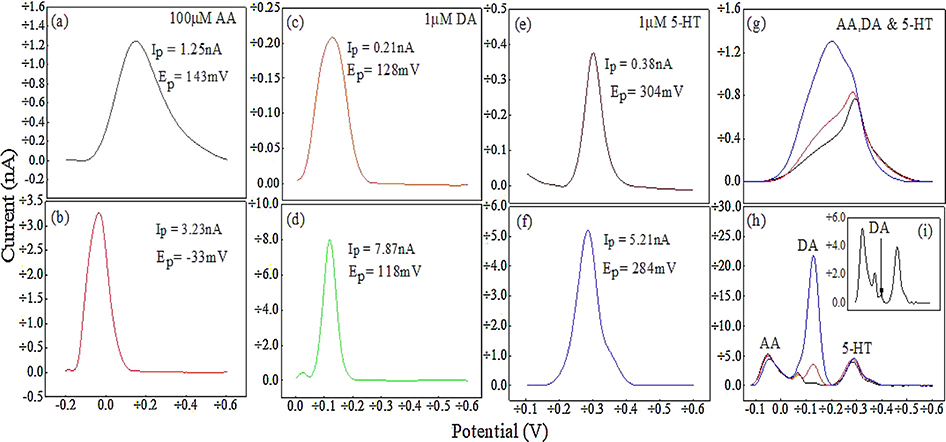

The chemical selectivity of the thin film microelectrode was assessed using DPV technique. Representative differential pulse voltammograms of individual AA, DA and 5-HT solutions as measured by unmodified (Fig. 4a, c and e) and thin film microelectrodes (Fig. 4b, d and f) demonstrate that both microelectrodes can measure these analytes individually. The moving average method available in the NOVA 10.1 software was used to correct the baseline currents in the voltammograms. The oxidation peaks were narrower for the thin film microelectrode and the AA peak was located at the lowest potential (−33 mV) as compared to DA (118 mV) and 5-HT (284 mV), which is consistent with previous studies using CNTs [16]. The DPV peak currents (Ip, nA) and full width at half maximum (FWHM, mV) for 100 μM AA, 1 μM DA and 1 μM 5-HT are 3.23 ±8% nA, 7.87 ± 12% nA, 5.12 ± 6% nA and 122 ± 12% mV, 52 ± 4% mV, 70 ±6 % mV, respectively (n = 3). A shoulder is observed on the DA and 5-HT oxidation peak resulting from their oxidation byproducts, consistent with previous studies [16,48–50]. In contrast, the unmodified microelectrode showed broad peaks with the DA peak located at the lowest potential (128 mV) as compared to AA (143 mV) and 5-HT (304 mV). The Ip and FWHM for 100 μM AA, 1 μM DA and 1 μM 5-HT are 1.25 ± 5% nA, 0.21 ± 7% nA, 0.38 ± 8% nA and 256 ± 8% mV, 118 ± 8% mV, 59 ± 2% mV, respectively. Also, the AA peak overlaps the DA and 5-HT peaks, which demonstrates poor selectivity. In addition to peak position and peak width, the thin film microelectrode has a significant effect on peak current. For a given DA concentration, the ip at the modified microelectrode is 38 times greater than that of an unmodified microelectrode. Similarly, for a given 5-HT concentration, it is 14 times greater. In a ternary mixture of AA, DA and 5-HT, the unmodified microelectrode is unable to distinguish all three chemicals due to overlapping Ep (Fig. 4g). This indicates that it is unsuitable for multiplexing when AA is present. In contrast, the modified microelectrode is capable of distinguishing DA and 5-HT in the presence of excess amounts of AA with three distinct peaks (Fig. 4h), which are comparable to CNT based microsensors that are directly grown on metal catalysts [16]. The modified microelectrode measured as low as 50 nM DA in the presence of 1 μM 5-HT and 100 μM AA, which demonstrates a 2000-fold selectivity.

Fig. 4.

Baseline-corrected differential pulse voltammograms (DPV) of 100 μM AA, 1 μM DA and 1 μM 5-HT with unmodified (a, c, e) and MWCNT thin film modified (b, d, f) UNCD microelectrode. (g, h) DPV plots of a ternary mixture of 100 μM AA, 1 μM HT-5 and DA (100nM - black curve, inset “i”, 1 μM – red, 10 μM – blue) with unmodified and modified microelectrode, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Finally, MWCNT film stability was assessed by subjecting the thin film microelectrode to electrochemical cycling for up to 5 h, a common protocol applied when CNT microelectrodes are used for chemical detection (see supplementary information, Fig. S2). The sensor metrics almost remain unchanged during the cycling treatment. This demonstrates excellent stability for the MWCNT film and also implies excellent suitability for acute chemical sensing and brain slice studies that normally requires microsensors to be fully functional for few hours.

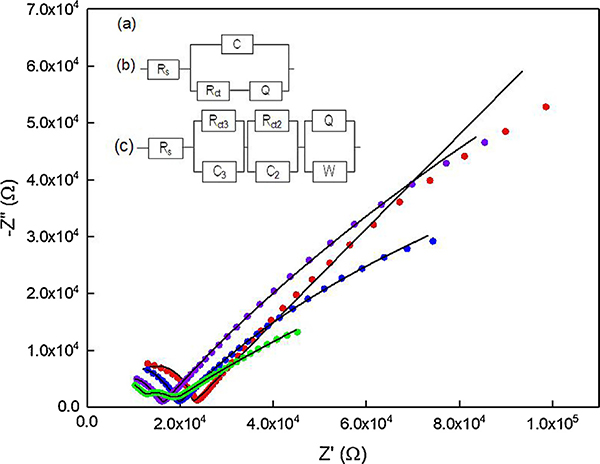

3.3. EIS characterization of MWCNT- modified UNCD microelectrodes: effect of MWCNT film thickness on interfacial properties

The EIS spectrum of an unmodified UNCD microelectrode is fitted to [Rs(C[RctQ])], a slightly modified two-Q circuit model [34] (Fig. 5b). For the modified microelectrode, we developed an electrochemical pore model to describe different types of pores resulting from film modification (see supplementary information). According to the model, the modified microelectrode is comprised of three regions, namely Region 1, Region 2 and Region 3 that have varying electrochemical activity. The total current and the corresponding electrochemical activity varies in each region due to differences in the geometrical structure of the pores. Region 3 is considered to be a highly electrochemically active, Region 2 is considered to be a pure resistor, and Region 1 is a less electrochemically active region. EIS data was collected from the three modified microelectrodes, viz. thin, thick and thickest films and fitted to these circuit models. The Nyquist plots of the impedance data for the microelectrodes are shown in Fig. 5a. The Nyquist plot of the thin film shows an arc of a semi-circle at high frequencies followed by a straight-line at low frequencies. The model as described in Fig. 5c was fitted to the EIS data. The model is a combination of three circuits contributing to an overall impedance and each corresponds to the three different regions on the modified microelectrode as described above. The values of the circuit elements (Table 3) show that each region contributes to a different degree to the overall impedance (Z) values. The circuit corresponding to low impedance is due to highly electrochemically active region and the circuit corresponding to very high impedance is due to the least electrochemically active region. Thus, this circuit model further validates the proposed pore model described above (see supplementary information for the details).

Fig. 5.

(a) Nyquist plots of unmodified and MWCNT film modified UNCD microelectrodes-unmodified (red dotted), thin MWCNT film (purple dotted), thick MWCNT film (blue dotted) and thickest MWCNT (green dotted). (b) The equivalent circuit of the unmodified UNCD. (c) Equivalent circuit of MWCNT-modified UNCD microelectrodes. The electrolyte is 5 mM Fe(CN)63−/4− in 1 M KCl. 10 mV amplitude, OCP, 0.1 Hz-100 KHz. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 3.

Values of interfacial parameters of MWCNT-modified UNCD microelectrodes obtained by fitting the circuit to experimental data. The% errors for the circuit elements are 0–20%.

| Microelectrode type | Rs (KΩ) |

Region 3 |

Region 2 |

Region 1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3(nF) | Rct3(KΩ) | C2(PF) | Rct2 (KΩ) | YQ1 (μMho) | N | YW (μMho) | ||

| Thin MWCNT-UNCD | 4.3 | 7.1 | 1.8 | 128 | 9.7 | 4.4 | 0.16 | 10.6 |

| Thick MWCNT-UNCD | 3.7 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 83 | 13.1 | 9 | 0.15 | 10.6 |

| Thickest MWCNT- UNCD | 2.8 | YQ (nMho)/N 109/0.7 | 6.6 | 85 | 8.5 | 28.7 | 0.24 | 9.8 |

The impedance Z3 contributed by the first RC circuit is described below:

| (1) |

The C3 and Rct3 are the capacitance of the pore walls and charge transfer resistance of the pores, respectively. C3 is of the order of nanofarads, Rct3 is of the order of kilo-ohms, and therefore at low frequencies, the impedance of the pores of this region is equivalent to Rct3. Whereas at high frequencies, the impedance of the pores is less than Rct3. Thus, at high frequencies, the AC signal cannot penetrate deeply into the pores because of the IR drop, and a low impedance value for the pore walls is observed. However, at low frequencies, the AC signal can penetrate deeply into the pores and thus, the impedance is high. This frequency dependence behavior of the pore impedance of this region is similar to that of De Levie’s pore model [51] (see supplementary information). Further, the RC circuit for this region suggests that these pores are comprised of continuous walls with the fewest openings as C arises from a homogenous structure. The impedance of such pores is dependent on the frequency of the AC signal and corresponds to a scenario where the condition Iin> Iout is satisfied in the proposed model (see supplementary information). The capacitance described in the circuit may correspond to the total capacitance of the pore walls at low frequencies. For a thin and thick film, the impedance described above corresponds to Region 3, a highly electrochemically active region.

The impedance Z2 contributed by the second RC circuit is described below:

| (2) |

The C2 value is of the order of picofarads and the Rct2 value is of the order of kΩs. Therefore, the denominator term in the above expression for all frequencies will satisfy the following condition, 1 >>ωRct2C2 and therefore the equation can be simplified to:

| (3) |

Hence, this RC circuit corresponds to a less electroactive region on the electrode where the impedance of the pores does not depend on the frequency of the signal. From the above model, this scenario Iin = Iout will be satisfied because such a region behaves like a resistor. Therefore, the impedance described in Eq. (3) corresponds to Region 2 as described in the proposed model.

The third circuit comprises of impedance due to the Constant Phase Element (CPE) and the Warburg (mass transfer) impedance. The total impedance contributed by this circuit is described below:

| (4) |

where Yq is the admittance of an ideal capacitor and Yw is the admittance of diffusion, and ω is the frequency. The CPE is a consequence of the inhomogeneities in the structure of the pore walls. Therefore, diffusion has multiple paths and the electroactive species can enter and leave a pore at different points along the length of the pore. Similarly, the AC signal can enter or leave at different points as well. If the total current entering through pore is less than the current leaving the pore (Iin< Iout), this can result in an overall small current in the pores leading to reduced electrochemical activity. This is mainly a geometrical effect, which depends on pore geometry and their surroundings. The impedance of these pores is mainly diffusion dependent and it correspond to Region 1. As shown in Table 3, the values of Yq and Yw are of the order of irMho. This means that ZT will be of the order of MΩ irrespective of other factors such as frequency and the value of N and as a result Z1, will contribute towards a high impedance at the electrode surface.

For thick film microelectrodes, Region 2 becomes slightly more resistive, the C in Region 3 is reduced by a factor of 0.5 and the admittance of Region 1 increased by a factor of 2. As shown in Eq. (4), admittance is inversely related to impedance. By increasing the film thickness from thick to thickest, for Region 3, the C of the circuit is replaced by a CPE, which implies that the walls of such pores have become inhomogenous. The Rct in such regions increases by a factor of 3. This implies that as the film thickness is increased the electroactive species inside the pores of Region 3 become saturated due the lack of diffusion of new electroactive species and a corresponding higher Rct. This increase in impedance of these pores contributes to an overall increase in charging current (Ic) “noise”. The impedance of Region 2 remains the same as that of a thin film electrode. However, the admittance of Region 1 increases by a factor of 7, presumably due to lower contact resistance between the UNCD and the overlying MWCNT film. Thus, such pores have become more electrochemically active even though their walls remain inhomogenous and the Warburg element is equivalent. Thus, electroactive species can diffuse by multiple pathways and contribute to an overall increase in the redox current “signal” (Is). On the whole, as the film thickness increases, impedances of Region 3 increase and contribute to noise, while impedances of Region 2 are equivalent. However, in Region 1, the impedance of the pores decreases, as they become more electrochemically active and contribute significantly towards the overall signal at the microelectrode. Since a high sensitivity and high S/N ratio is expected from any sensor, it is important to understand which regions and to what extent each region contributes to the signal and noise. The EIS model demonstrates that for thin film microelectrodes, Region 3 and Region 1 contribute towards the signal and Region 2 towards the noise. While, for thickest film microelectrodes, Region 3 and Region 2 contribute more noise and Region 1 contributes more signal. Furthermore, at thicker films, the arc at high frequencies is suppressed. The main reason for such behavior is that the pores have become more inhomogeneous. The circuit fitting parameters incorporate this effect by adjusting the capacitance element to a CPE as shown in Fig. 5. Therefore, this model illustrates that the sensor metrics for a given analyte can be tuned by controlling the relative thicknessess (or volumes) of the three regions in the microelectrode. This was validated here experimentally by measuring DA.

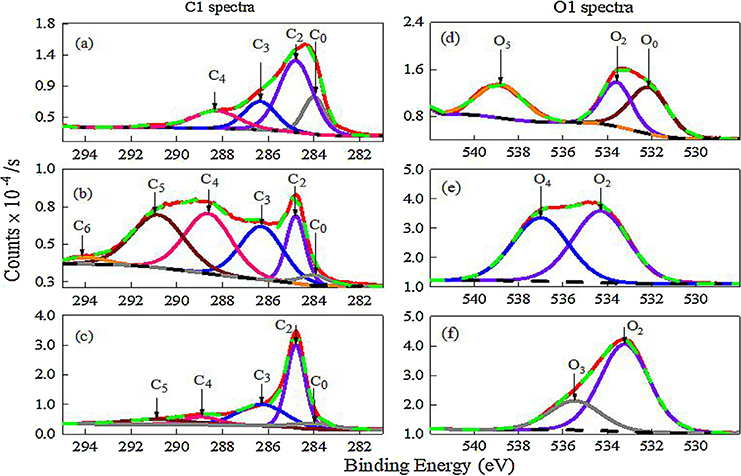

3.4. XPS characterization of MWCNT-modified UNCD microelectrodes: effect of surface functional groups on electrochemical properties

XPS studies were carried out to understand the origin of the differing levels of electrochemical activity of the microelectrode regions as identified in the EIS studies. The C1 s spectrum of an unmodified UNCD microelectrode (Fig. 6a) mainly consists of phase pure sp3 hybridized diamond grains (C2 peak) and non-diamond amorphous carbon in grain boundaries (C0 peak). A list of possible surface functional groups for sp2 and sp3 surfaces are shown in Fig. S4 (see supplementary information). The C3 and C4 peaks corresponds to the C—O and C=O groups along the grain boundaries. The Q and Rct values obtained from the EIS spectrum are actually determined by which C1 s and O1 s peaks appears in the XPS spectrum (Table S3). The highly oxidized functional groups such as O2 and O5 that are present in the grain boundaries (Fig. 6d) contribute to the Q value and the C1 s and O1 s peaks contribute to the Rct value, respectively. In general, the presence of C1 s and O1 s peaks are indicative of high and low electrochemical activity regions, respectively [22,23,52,53]. The [O/C + O] ratio of ~0.3 calculated from [54] core level C1 (284.8 eV) and O1 (532 eV) spectra suggests a quasireversible electrochemical behavior as reported previously [10,55]. The MWCNT thin film modified microelectrode has more electrochemically active carbon functionalities, namely C0, C2, C3, C4, C5 and C6 (Fig. 6b). C1s spectra revealed a highly ordered graphitic structure (C2 peak) accompanied by detects (C0 peak) orginating from carbon atoms that are no longer in the regular tubular MWCNT structure [56,57]. A lower percentage of sp2 carbon (1.0 ±0.16%) in the thin film resulted in a lower background current or noise and thus, a higher S/N ratio. Besides the presence of aromatic and aliphatic functionalities (C3, C4 peaks), the (π → π*) satellite peak that is assigned to shake up structures, increased the overall electrical conductivity of the thin film microelectrode [58]. Interestingly, the highly electroactive Region 1 observed in the EIS spectra and the high S/N ratio of >15 observed in the cyclic voltammogram could possibly be due to the presence of the satellite peak and a low sp2 content. The [O/C + O] ratio is ~0.8, a high abundance of carboxylic and phenolic groups (C3, C4, O2, O4 peaks) (Fig. 6e) allowed for enhanced adsorption-desorption kinetics for the dopamine - dopamine quinone redox couple, which caused DA sensitivity to increase [53]. For the thickest film microelectrode, the [O/C + O] ratio decreased to ~0.5 suggests removal of some oxygen functional groups (e.g., carboxyl groups, etc.) [54] and there was no satellite peak. The sp2 carbon content increased (C2 peak) and more importantly, there was a significant presence of a less electrochemically active ketone (O3) group (Fig. 6c and f). These factors overall contributed to a more resistive electrode Region 3 as observed in EIS and a lower S/N ratio of DA detection as observed in the cyclic voltammogram. The thin film microelectrode exhibited trace amounts (0.03 At %) of magnesium (Mg) at ~1305 eV that are due to MgCl2 salt that was added to the MWCNT suspension during the EPD process [33]. The thickest film sample showed Mg in the form of native oxide and carbonate at a much higher weight percentage (6.3 At %). We assume that these impurities could have contributed to blocking of some of the pores, which reduced the number of DA diffusion pathways, increased the Rct of Region 3 and lowered the S/N to 9. This will require further study.

Fig. 6.

C1 and O1 XPS spectra of (a, d) unmodified, (b, e) thin MWCNT film and (c, f) thickest MWCNT film modified UNCD microelectrodes. Legends: experimental spectrum (red curve), fitted spectrum (green), background (black dotted). (a-c) Fitted C1 spectrum consists of C0 peak (gray), C2 (violet), C3 (blue), C4 (pink), C5 (wine) and C6 (orange). (d-f) Fitted O1 spectra consists of O0 peak (wine), O2 (violet), O3 (gray), O4 (blue), O5 (orange). The surface functionality and binding energy for each C1 and O1 peak is shown in Table S3 (see supplementary information). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

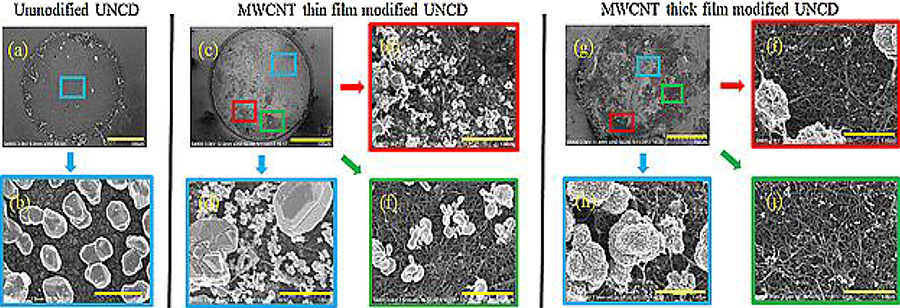

3.5. SDI of MWCNT-modified UNCD microelectrodes: effect of MWCNT film thickness on electrochemical activity

Mapping of electrodeposited metal particles is an established technique to study the hetereogenities in electrical conductivity and electrochemical activity on an electrode surface [59,60]. A highly uniform distribution of Ag particles across the unmodified UNCD microelectrode surface (2.04±3% particles/μm2) reveals one region with identical electroactivity (Fig. 7a and b). The nearly spherically shaped Ag particles (diameter ~500 nm ± 19%) confirms a diffusion-controlled particle growth mechanism due to Ostwald ripening and this is expected on hydrophobic surfaces such as unmodified UNCD microelectrode [61].

Fig. 7.

SEM images of Ag particle mapping on (a, b) unmodified, (c-f) MWCNT thin film and (g-j) MWCNT thickest film modified UNCD microelectrodes. Cyan colored squares represents densely-deposited areas, red squares for semi-densely and green squares for sparsely deposited areas. Scale bars for (a, c, g) are 100 μm and for (b, d, e, f, h, i & j) are 1 μm. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The MWCNT thin film microelectrode showed irregularly shaped, high-density, large Ag particles (diameter ~900 nm ± 18%) that were deposited on highly conductive regions (Fig. 7c and d) and this could be due to high-density defects within the MWCNT network [62]. Hydrophilic MWCNT regions aided the formation of small-sized Ag particle clusters (~3–4.5 μm) favoring dendritic growth [61]. This is due to the inhomogeneity of the interfacial surface tension resulting in non-uniform distribution of the Ag precursors (Fig. 7e) [59]. Also, the clusters that were observed in and around the pores of MWCNT network could be due to Michael addition and Schiff base reaction [63] primarily with redox active carbon-oxygen functionalites of MWCNT. In addition, a low-density, scattered formation of smaller Ag particles was found in less conductive regions [59,61] (4.7 ± 23% particles/μm2). This could be due to reduced availability of redox active carbon- oxygen functionalities in those less conductive pores (Fig. 7f) [63]. The MWCNT thickest film microelectrode (Fig. 7g and h) showed “cauliflower-like” Ag particle formation (diameter ~800 nm ± 21%) in —COOH rich, high conductivity regions of the MWCNT network [62]. The Ag particle distribution suggests a random allocation of hydrophilic, conductive regions (Fig. 7h) coexisting with resistive regions (Fig. 7i and j), which agrees well with EIS findings.

4. Conclusion

We have shown that MWCNT film modified UNCD microelectrodes provide an excellent combination of key microsensor metrics such as sensitivity, selectivity, limit of detection and S/N ratio for neurochemical detection. The complementary Raman, XPS, EIS spectra and SDI have identified three regions of varying electrochemical activity, which can be tailored to further improve the electrochemical resolution of the many brain analytes in addition to DA and 5-HT. For instance, by choosing an appropriate set of EPD process parameters and MWCNT film properties, the randomness of the pore structure within the MWCNT film can be customized to enhance the detection performance metrics. This work demonstrates that the properties of this new class of hybrid MWCNT-UNCD microelectrode are dependent upon the MWCNT film thickness, their pore structure and surface functionalities. The key benefits of the hybrid microelectrode are - First, remarkable improvements in DA sensitivity (>125-fold), selectivity (>2000-fold) and LOD (>180-fold) offer great promise for advancing the chemical neuroscience field. Second, MWCNTs can be selectively coated with a simple, scalable and low cost EPD process for multiplexed neurochemical sensing. Third, this work will establish a new generation of ultra-miniaturized microelectrode arrays that are highly suitable for advanced neuroelectrochemical studies.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the Louisiana Board of Regents- RCS support fund [grant number LEQSF(2014–17)-RD-A-07], the National Aeronautics and Space Administration [grant number NNX13ABA], the National Science Foundation OIA/EPSCoR [grant number 1632891].

Biographies

Chao Tan He is currently a Ph.D. student at Louisiana Tech University. His research interest is to investigate advanced materials for multiplexed brain analyte sensing.

Gaurab Dutta He is currently a Ph.D. student at Louisiana Tech. His research is to develop a diamond electrochemical microsensor for chronic neurochemical monitoring.

Haocheng Yin He is currently a Ph.D. student at Louisiana Tech. His research is to develop novel nanoscale electrodes for electroanalytical applications.

Shabnam Siddiqui She is a research assistant professor in Center for Biomedical Engineering Rehabilitation Science at Louisiana Tech. Her research interests are in understanding the electrochemical properties of nanomaterials and their application in sensing and energy storage.

Prabhu Arumugam He is an assistant professor in Mechanical Engineering and Institute for Micromanufacturing at Louisiana Tech. His research interests are in the development of carbon nanomaterial based electrochemical microsensor technologies.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2017.11.054.

References

- [1].Pagels M, Hall CE, Lawrence NS, Meredith A, Jones TGJ, Godfried HP, Pickles CSJ, Wilman J, Banks CE, Compton RG, Jiang L, All-diamond microelectrode array device, Anal. Chem. 77 (2005) 3705–3708, 10.1021/ac0502100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Suzuki I, Fukuda M, Shirakawa K, Jiko H, Gotoh M, Carbon nanotube multi-electrode array chips for noninvasive real-time measurement of dopamine, action potentials, and postsynaptic potentials, Biosens. Bioelectron. 49 (2013) 1–6, 10.1016/j.bios.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Adams RN, Probing brain chemistry with electroanalytical techniques, Anal. Chem. 48 (1976) 1126A–1138A, 10.1021/ac50008a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sainio S, Palomäki T, Rhode S, Kauppila M, Pitkänen O, Selkälä T, Toth G, Moram M, Kordas K, Koskinen J, Laurila T, Carbon nanotube (CNT) forest grown on diamond-like carbon (DLC) thin films significantly improves electrochemical sensitivity and selectivity towards dopamine, Sens. Actuators B Chem. 211 (2015) 177–186, 10.1016/j.snb.2015.01.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kapur S, Remington G, Serotonin-dopamine interaction and its relevance to schizophrenia, Am. J. Psychiatry 153 (1996) 466–476, 10.1176/ajp.153.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Robinson DL, Venton BJ, Heien ML, Wightman RM, Detecting subsecond dopamine release with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry in vivo, Clin. Chem. 49 (2003) 1763–1773, 10.1373/49.10.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pihel K, Walker QD, Wightman RM, Overoxidized polypyrrole-coated carbon fiber microelectrodes for dopamine measurements with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, Anal. Chem. 68 (1996) 2084–2089, 10.1021/ac960153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wang HS, Li TH, Jia WL, Xu HY, Highly selective and sensitive determination of dopamine using a Nafion/carbon nanotubes coated poly(3-methylthiophene) modified electrode, Biosens. Bioelectron. 22 (2006) 664–669, 10.1016/j.bios.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zachek MK, Takmakov P, Moody B, Wightman RM, McCarty GS, Simultaneous decoupled detection of dopamine and oxygen using pyrolyzed carbon microarrays and fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, Anal. Chem. 81 (2009) 6258–6265, 10.1021/ac900790m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dutta G, Siddiqui S, Zeng H, Carlisle JA, Arumugam PU, The effect of electrode size and surface heterogeneity on electrochemical properties of ultrananocrystalline diamond microelectrode, J. Electroanal. Chem. 756 (2015) 61–68, 10.1016/jjelechem.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Strand AM, Venton BJ, Flame etching enhances the sensitivity of carbon-fiber microelectrodes, Anal. Chem. 80 (2008) 3708–3715, 10.1021/ac8001275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nemes P, Vertes A, Laser ablation electrospray ionization for atmospheric pressure, in vivo, and imaging mass spectrometry, Anal. Chem 79 (2007) 8098–8106, 10.1021/ac071181r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Arumugam PU, Chen H, Siddiqui S, Weinrich JAP, Jejelowo A,Li J, Meyyappan M, Wafer-scale fabrication of patterned carbon nanofiber nanoelectrode arrays: a route for development of multiplexed, ultrasensitive disposable biosensors, Biosens. Bioelectron. 24 (2009) 2818–2824, 10.1016/j.bios.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li J, Koehne JE, Cassell AM, Chen H, Ng HT, Ye Q, Fan W, Han J, Meyyappan M, Inlaid multi-walled carbon nanotube nanoelectrode arrays for electroanalysis, Electroanalysis 17 (2005) 15–27, 10.1002/elan.200403114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kovach PM, Ewing AG, Wilson RL, Mark Wightman R, In vitro comparison of the selectivity of electrodes for in vivo electrochemistry, J. Neurosci. Methods 10 (1984) 215–227, 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90058-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rand E, Periyakaruppan A, Tanaka Z, Zhang DA, Marsh MP, Andrews RJ, Lee KH, Chen B, Meyyappan M, Koehne JE, A carbon nanofiber based biosensor for simultaneous detection of dopamine and serotonin in the presence of ascorbic acid, Biosens. Bioelectron. 42 (2013) 434–438, 10.1016/j.bios.2012.10.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Huang J, Liu Y, Hou H, You T, Simultaneous electrochemical determination of dopamine, uric acid and ascorbic acid using palladium nanoparticle-loaded carbon nanofibers modified electrode, Biosens. Bioelectron. 24 (2008) 632–637, 10.1016/j.bios.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Salimi A, Abdi K, Khayatian GR, Amperometric detection of dopamine in the presence of ascorbic acid using a nafion coated glassy carbon electrode modified with catechin hydrate as a natural antioxidant, Microchim. Acta 144 (2004) 161–169, 10.1007/s00604-003-0048-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hočevar SB,Wang J, Deo RP, Musameh M, Ogorevc B, Carbon nanotube modified microelectrode for enhanced voltammetric detection of dopamine in the presence of ascorbate, Electroanalysis 17 (2005) 417–422, 10.1002/elan.200403175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Li S, Guo J, Chan M, Yuan J, Multi-walled carbon nanotube coated microelectrode array for high-throughput, sensitive dopamine detection, 9th IEEE Int Conf. Nano/Micro Eng. Mol. Syst. IEEE-NEMS; (2014) 643–646, 10.1109/NEMS.2014.6908894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Habibi B, Jahanbakhshi M, Pournaghi-Azar MH, Simultaneous determination of acetaminophen and dopamine using SWCNT modified carbon-ceramic electrode by differential pulse voltammetry, Electrochim. Acta 56 (2011) 2888–2894, 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.12.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Luong JH, Male KB, Glennon JD, Boron-doped diamond electrode: synthesis, characterization, functionalization and analytical applications, Analyst 134 (2009) 1965, 10.1039/b910206j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Suzuki A, Ivandini TA, Yoshimi K, Fujishima A, Oyama G, Nakazato T, Hattori N, Kitazawa S, Einaga Y, Fabrication, characterization, and application of boron-doped diamond microelectrodes for in vivo dopamine detection, Anal. Chem. 79 (2007) 8608–8615, 10.1021/ac071519h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Arumugam PU, Zeng H, Siddiqui S, Covey DP, Carlisle JA, Garris PA, Characterization of ultrananocrystalline diamond microsensors for in vivo dopamine detection, Appl. Phys. Lett. 102 (2013) 253107, 10.1063/1.4811785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xie S, Shafer G, Wilson CG, Martin HB, In vitro adenosine detection with a diamond-based sensor, Diam. Relat. Mater. 15 (2006) 225–228, 10.1016/j.diamond.2005.08.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Koehne JE, Marsh M, Boakye A, Douglas B, Kim IY, Chang SY, Jang DP, Bennet KE, Kimble C, Andrews R, Meyyappan M, Lee KH, Carbon nanofiber electrode array for electrochemical detection of dopamine using fast scan cyclic voltammetry, Analyst 136 (2011) 1802, 10.1039/c1an15025a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Xiao X, Birrell J, Gerbi JE, Auciello O, Carlisle JA, Low temperature growth of ultrananocrystalline diamond, J. Appl. Phys. 96 (2004) 2232–2239, 10.1063/1.1769609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Krauss AR, Auciello O, Gruen DM, Jayatissa A, Sumant A, Tucek J, Mancini DC, Moldovan N, Erdemir A, Ersoy D, Gardos MN, Busmann HG, Meyer EM, Ding MQ, Ultrananocrystalline diamond thin films for MEMS and moving mechanical assembly devices, Diam. Relat. Mater. 10 (2001) 1952–1961, 10.1016/S0925-9635(01)00385-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Halonen N, Rautio A, Leino A, Kyllo T, Huuhtanen M, Keiski RL, Kiricsi I, Ajayan PM, Vajtai R, Three-dimensional carbon nanotube catalyst support membranes, ACS Nano 4 (2010) 2003–2008, 10.1021/nn100150x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Luo J, Wu Y, Lin S, Review Recent developments of carbon nanotubes hybrid assemblies for sensing, Am. J. Nano Res.Appl.3 (2015) 23–28, 10.11648/j.nano.s.2015030101.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kong J, Cassell AM, Dai H, Chemical vapor deposition of methane for single-walled carbon nanotubes, Chem. Phys. Lett. 292 (1998) 567–574, 10.1016/S0009-2614(98)00745-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chhowalla M, Teo KB, Ducati C, Rupesinghe NL, Amaratunga GA, Ferrari AC, Roy D, Robertson J, Milne WI, Growth process conditions of vertically aligned carbon nanotubes using plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition, J. Appl. Phys. 90 (2001)5308–5317, 10.1063/!.1410322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhao H, Song H, Li Z, Yuan G, Jin Y, Electrophoretic deposition and field emission properties of patterned carbon nanotubes, Appl. Surf. Sci. 251 (2005) 242–244, 10.1016/j.apsusc.2005.03.202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Siddiqui S, Dai Z, Stavis CJ, Zeng H, Moldovan N, Hamers RJ, Carlisle JA, Arumugam PU, A quantitative study of detection mechanism of a label-free impedance biosensor using ultrananocrystalline diamond microelectrode array, Biosens. Bioelectron. 35 (2012) 284–290, 10.1016/j.bios.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Naguib NN, Elam JW, Birrell J, Wang J, Grierson DS, Kabius B, Hiller JM, Sumant AV, Carpick RW, Auciello O, Carlisle JA, Enhanced nucleation, smoothness and conformality of ultrananocrystalline diamond (UNCD) ultrathin films via tungsten interlayers, Chem. Phys. Lett. 430 (2006) 345–350, 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.08.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [36].McCreery R, Advanced carbon electrode materials for molecular electrochemistry, Chem. Rev. 108 (2008) 2646–2687, 10.1021/cr068076m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zeng H, Konicek AR, Moldovan N, Mangolini F, Jacobs T, Wylie I, Arumugam PU, Siddiqui S, Carpick RW, Carlisle JA, Boron-doped ultrananocrystalline diamond synthesized with an H-rich/Ar-lean gas system, Carbon N.Y. 84(2015) 103–117, 10.1016/j.carbon.2014.11.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Choi WB, Jin YW, Kim HY, Lee SJ, Yun MJ, Kang JH, Choi YS, Park NS, Lee NS, Kim JM, Electrophoresis deposition of carbon nanotubes for triode-type field emission display, Appl. Phys. Lett. 78 (2001) 1547–1549, 10.1063/1.1349870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dutta G, Tan C, Siddiqui S, Arumugam PU, Enabling long term monitoring of dopamine using dimensionally stable ultrananocrystalline diamond microelectrodes, Mater. Res. Express 3 (2016) 94001, 10.1088/2053-1591/3/9/094001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Alcantar-Peňa J, Montes J, Arellano-Jimenez M, Aguilar JEO, Berman-Mendoza D, Garcĭa R, Yacaman MJ, Auciello O, Low temperature hot filament chemical vapor deposition of ultrananocrystalline diamond films with tunable sheet resistance for electronic power devices, Diam. Relat. Mater. 69 (2016) 207–213, 10.1016/j.diamond.2016.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lehman JH, Terrones M, Mansfield E, Hurst KE, Meunier V, Evaluating the characteristics of multiwall carbon nanotubes, Carbon N. Y. 49 (2011) 2581–2602, 10.1016/jxarbon.2011.03.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zanin H, May PW, Lobo AO, Saito E, Machado JP, Martins G, Trava-Airoldi VJ, Corat EJ, Effect of multi-walled carbon nanotubes incorporation on the structure, optical and electrochemical properties of diamond-Like carbon thin films, J. Electrochem. Soc. 161 (2014) H290–H295, 10.1149/2.011405jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [43].May PW, Ludlow WJ, Hannaway M, Heard PJ, Smith JA, Rosser KN, Raman and conductivity studies of boron-doped microcrystalline diamond, facetted nanocrystalline diamond and cauliflowerdiamond films, Diam. Relat. Mater. 17 (2008) 105–117, 10.1016/j.diamond.2007.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Peng H, Alemany LB, L Margrave J, Khabashesku VN, Sidewall carboxylic acid functionalization of single-walled carbon nanotubes, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125 (2003) 15174–15182, 10.1021/ja037746s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bennett JA, Wang J, Show Y, Swain GM, Effect ofsp2-bonded nondiamond carbon impurity on the response of boron-doped polycrystalline diamond thin-film electrodes, J. Electrochem. Soc. 151 (2004) E306, 10.1149/1.1780111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bard AJ, Faulkner LR,Leddy J, Zoski CG, Electrochemical methods: fundamentals and applications, Wiley, 1980, 10.1016/B978-0-12-381373-2.00056-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Streeter I, Wildgoose GG, Shao L, Compton RG, Cyclic voltammetry on electrode surfaces covered with porous layers: an analysis of electron transfer kinetics at single-walled carbon nanotube modified electrodes, Sens. Actuators B 133 (2008) 462–466, 10.1016/j.snb.2008.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Keeley GP, Lyons MEG, The effects of thin layer diffusion at glassy carbon electrodes modified with porous films of single-walled carbon nanotubes, Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 4 (2009) 794–809. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mphuthi NG, Adekunle AS, Fayemi OE, Olasunkanmi LO, Ebenso EE, Dong H, Sun CQ, Bein D, Lemoine P, Quinn JP, Phthalocyanine doped metal oxide nanoparticles on multiwalled carbon nanotubes platform for the detection of dopamine, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 43181, 10.1038/srep43181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Laurila T, Protopopova V, Rhode S, Sainio S, Palomaki T, Moram M, Feliu JM, Koskinen J, New electrochemically improved tetrahedral amorphous carbon films for biological applications, Diam. Relat. Mater. 49 (2014) 62–71, 10.1016/j.diamond.2014.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [51].De Levie R, Electrochemical Response of Porous and Rough Electrodes, John Wiley & Sons, 1967, 10.1002/SERIES6122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Notsu H, Yagi I, Tatsuma T, Tryk DA, Fujishima A, Introduction of oxygen-containing functional groups onto diamond electrode surfaces by oxygen plasma and anodic polarization, Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2 (1999)522–524, 10.1149/1.1390890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Duo I, Levy-Clement C, Fujishima A, Comninellis C, Electron transfer kinetics on boron-doped diamond Part I: influence of anodic treatment, J. Appl. Electrochem. 34 (2004) 935–943, 10.1023/B:JACH.0000040525.76264.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tu Y, Ichii T, Utsunomiya T, Sugimura H, Vacuum-ultraviolet photoreduction of graphene oxide: electrical conductivity of entirely reduced single sheets and reduced micro line patterns, Appl. Phys. Lett. 106 (2015) 133105, 10.1063/L4916813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Wang M, Simon N, Charrier G, Bouttemy M, Etcheberry A, Li M, Boukherroub R, Szunerits S, Distinction between surface hydroxyl and ether groups on boron-doped diamond electrodes using a chemical approach, Electrochem. Commun. 12 (2010) 351–354, 10.1016/j.elecom.2009.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Datsyuk V, Kalyva M, Papagelis K, Parthenios J, Tasis D, Siokou A, Kallitsis I, Galiotis C, Chemical oxidation of multiwalled carbon nanotubes, Carbon N. Y. 46 (2008) 833–840, 10.1016/j.carbon.2008.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ago H, Kugler T, Cacialli F, Salaneck WR, Shaffer MSP, Windle AH, Friend RH, Work functions and surface functional groups of multiwall carbon nanotubes, J. Phys. Chem. B 103 (1999) 8116–8121, 10.1021/jp991659y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Lascovich JC, Scaglione S, Comparison among XAES PELS and XPS techniques for evaluation of sp2 percentage in a-C:H, Appl. Surf. Sci. 78 (1994) 17–23, 10.1016/0169-4332(94)90026-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Colley AL, Williams CG, Johansson UDH, Newton ME, Unwin PR, Wilson NR, Macpherson JV, Examination of the spatially heterogeneous electroactivity of boron-doped diamond microarray electrodes, Anal. Chem. 78 (2006) 2539–2548, 10.1021/ac0520994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Peric-Grujic A, Neskovic OM, Veljkovic MV, Lausevic ZV, Lausevic MD, Surface characterization of silver and palladium modified glassy carbon, Bull. Mater. Sci. 30 (2007) 587–593, 10.1007/s12034-007-0093-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Paunovic M, Schlesinger M, Fundamentals of Electrochemical Deposition, Wiley, 2006, 2005058421. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Haniyeh F, Abdollah A, Abolghasem D, Controlled growth of well-Aligned carbon nanotubes, electrochemical modification and electrodeposition of multiple shapes of gold nanostructures, Mater. Sci. Appl. 4 (2013) 667–678, 10.4236/msa.2013.411083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Sileika TS, Do Kim H, Maniak P, Messersmith PB, Antibacterial performance of polydopamine-modified polymersurfaces containing passive and active components, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 3 (2011) 4602–4610, http://dx.doiorg/10.1021/am200978h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Wang M, Gao Y,Zhang J,Zhao J, Highly dispersed carbon nanotube in new ionic liquid-graphene oxides aqueous dispersions for ultrasensitive dopamine detection, Electrochim. Acta 155 (2015) 236–243, 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.12.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.