After implementing to varying degrees of success non-pharmaceutical interventions to control the COVID-19 outbreak, countries around the world are now lifting restrictions, many seemingly without heed of epidemic curves, reproductive number estimates, or regional differences in these. Economic pressures are driving these decisions, with the detrimental effects of an economic crisis anticipated to outweigh the damage caused by the virus. There is some justification for this concern: the World Bank estimates that at least 71 million people will be pushed into extreme poverty, itself a public health issue, as a result of the pandemic. Thus, for some countries it seems lifting lockdown restrictions is not a choice but a necessity. All countries, however, should endeavour to lift restrictions in a way that considers the scientific evidence. Any increase in cases and deaths resulting from relaxing restrictions too quickly will likely diminish public trust at a time when public confidence in decision makers is already low.

In the UK, which as of June 10 ranks fourth in the world in number of COVID-19 cases and second in number of deaths, public approval of the Conservative Government's handling of the COVID-19 outbreak has declined steadily during lockdown. According to a YouGov survey, only 41% of people in the UK on May 29 said they thought the government was handling the issue of COVID-19 very or somewhat well, compared with a high of 72% on March 27. Loss of confidence in the UK Government results in part from confusing and inconsistent messaging at the government's daily media briefings, a lack of transparency around the scientific evidence and who exactly is informing policy, neglect of care homes as cases and deaths in hospitals rose, and refusal to acknowledge the dearth of personal protective equipment available to health-care workers. Prime Minister Boris Johnson's continued support of his chief advisor Dominic Cummings after Cummings broke lockdown rules was perhaps the final nail in the coffin of public trust. Unsurprisingly, hypocrisy and an attitude of “one rule for us, another for them” does not win public favour.

Elsewhere, public confidence in country leadership is similarly declining. Unpopular internationally and domestically before the outbreak, support for Brazil's President Jair Bolsonaro has since taken a further nosedive because of his failure to acknowledge the seriousness of the pandemic and his open flouting of lockdown rules while thousands of Brazilians die from COVID-19. Bolsonaro's actions have sown confusion and dissent among the Brazilian population, made worse by the government's decision on June 5 to cease publishing cumulative totals of COVID-19 cases and deaths and to remove months of data from the public domain. After public outrage, accusations of censorhip, and a ruling by a Supreme Court judge, these data were quickly reinstated, but the damage had already been done.

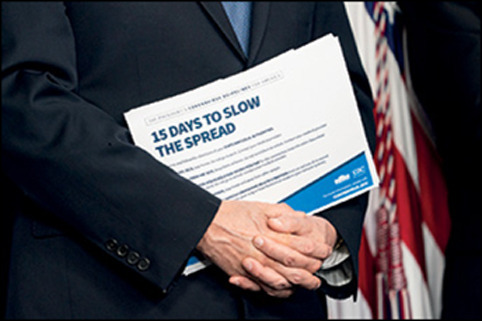

In the USA, President Donald Trump has made clear from the beginning of the outbreak that the US economy is his priority, and with encouragement from the president, many states had entirely lifted lockdown restrictions by the end of May. Lifting these measures occurred despite infections still increasing in some states and the country's ranking as worst affected in the world. The human toll of the pandemic in the USA, combined with disastrous press briefings, Trump's decision to terminate the USA's relationship with WHO, and his aggressive response to Black Lives Matter demonstrations, has led Trump's popularity to slump.

Public distrust of authorities has detrimental effects on control of infectious diseases. Not only does it permit conspiracy theories to take hold, but it also fosters vaccine hesitancy. It is not clear when a COVID-19 vaccine will be ready to deploy, but its success will to a great extent be determined by people's acceptance of immunisation. Vaccine hesitancy has been on the rise, and evidence from a survey in France suggests the situation is no different for COVID-19. 26% of respondents to the survey said they would not use a vaccine if one became available, with differences in acceptance related to the candidate who respondents voted for in the first round of the 2017 presidential election. This finding demonstrates the integral role of politicians in acceptance of public health interventions. Public mistrust in leadership could also undermine the public's compliance with, and so success of, responses to a second wave of infections.

Governments and political leaders around the world might become casualties of COVID-19. How they have responded to the outbreak and listened to and communicated with their citizens will be important in deciding their fates in future elections. Public trust must be earnt, and COVID-19 has made clear who is and is not worthy of that trust.

© 2020 Joyce N Boghosian