Abstract

Cancer patients are vulnerable to complications of respiratory viruses. This systematic review and meta-analysis sought to examine the prevalence of cancer and its association with disease severity in patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Searches were performed in MEDLINE, EMBASE and ScienceDirect from their inception until 28 April 2020. Severe disease was considered to encompass cases resulting in death or as defined by the primary study authors. Meta-analysis was performed using random-effect models. We included 20 studies involving 32,404 patients from China, the United Kingdom, the United States, Italy, Singapore, Thailand, France, India and South Korea. The pooled prevalence of cancer was 3.50% (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.70 to 5.80). The pooled prevalence was not moderated by study mean age, proportion of females or whether the study was conducted in/outside of China. Patients with cancer were more likely to experience severe COVID-19 disease compared to patients without cancer (pooled risk ratio 1.76, 95% CI 1.39 to 2.23). Our findings reiterate the need for additional precautionary measures to ensure that patients with cancer are not exposed to COVID-19, and if they become infected, extra attention should be provided to minimise their risk of adverse outcomes.

Keywords: COVID-19, coronavirus, SARS, pandemic

Inroduction

The world is battling an immense threat from novel corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19). As of 28 April 2020, more than 3.1 million confirmed COVID-19 cases had been reported from over 150 countries, among whom over 220,000 had died [1]. Most COVID-19-related deaths have been attributed to multiple organ failure in older or comorbid individuals [2].

A recent meta-analysis estimated that 2% of patients with COVID-19 had cancer [3]. However, the analysis included only data from China and did not evaluate the association of cancer with severe COVID-19 disease. Cancer patients may be more susceptible to COVID-19 than healthy individuals due to their high immunosuppressive burden caused by the cancer and anticancer treatments [4]. Improved understanding of the burden of cancer in COVID-19 patients may help to guide clinical management. Hence, in this study, we aimed to estimate the prevalence of cancer among COVID-19-infected patients as well as ascertain the association between cancer and disease severity.

Methods

A systematic review was performed in accordance with the recommendations outlined in the PRISMA statement [5] and the Cochrane Handbook [6]. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and ScienceDirect using the terms ‘comorbidities’ or ‘clinical characteristics’ or ‘epidemiological’ and ‘COVID-19’ or ‘Coronavirus’ or ‘2019-nCoV’ or ‘SARS-CoV-2’ or ‘2019 novel coronavirus’ (Supplemental Table S1). The search was last updated on April 28, 2020. Further searches were also performed via the websites of the World Health Organization (WHO) and key public health institutions in some of the most affected countries (Supplementary Table S2) [1]. The reference lists of identified studies were also screened for additional papers. Two reviewers (O.O and R.O) performed article screening and any disagreements were resolved via consensus. Severe disease was considered to encompass cases resulting in death [7] or as defined by the study authors [7]. The quality of individual studies was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for non-randomized studies [8]. For each study, two reviewers (R.O and O.O) independently collected data, including author details, country (region), mean age, proportion of females, and data on prevalence and disease severity. We excluded studies based on family clusters, those focusing solely on deceased individuals and case series involving <10 patients or only children. Moreover, reviews, commentaries and editorials were excluded. Furthermore, because a national-based study in China was published with data up to February 11, 2020, we excluded all sub-national studies in China that recruited only patients up until that date. However, if a study based in China recruited patients beyond this date, they were included. Also, if studies from the same region or hospital recruiting patients over the period were present, we selected the report with the larger sample size or more detailed data.

Table S1. Search strategy.

| 1 COVID-19.mp. 2 COVID-19.m_titl. 3 2019 novel coronavirus.mp. 4 2019 novel coronavirus.m_titl. 5 2019-nCoV.mp. 6 2019-nCoV.m_titl. 7 SARS-CoV-2.m_titl. 8 SARS-CoV-2.m_titl. 9 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 10 comorbidities.mp. or Comorbidity/ 11 comorbidity.mp. 12 clinical characteristics.mp. 13 clinical characteristics.m_titl. 14 epidemiological.mp. 15 epidemiolog*.mp. or Epidemiology/ 16 epidemiological.m_titl. 17 epidemiological.mp. 18 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 19 9 and 18 |

Table S2. Institutional websites of some of the countries searched.

| Country | Institution | Website |

|---|---|---|

| Global | World Health Organization | https://www.who.int/ |

| USA | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | https://www.cdc.gov/ |

| China | Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention | http://www.chinacdc.cn/en/ |

| Spain | National Centre of Epidemiology, Institute of Health Carlos III | https://www.isciii.es/Paginas/Inicio.aspx |

| Germany | Robert Koch Institute (RKI) | https://www.rki.de/EN/Home/homepage_node.html |

| France | Santé Publique France | https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/ |

| Iran | Ministry of Health and Medical Education | http://www.behdasht.gov.ir/ |

| UK | Public Health England | https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/public-health-england |

| Switzerland | Federal Office of Public Health | https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home.html |

| The Netherlands | National Institute of Public Health and the Environment | https://www.rivm.nl/en |

| Canada | Public Health Agency of Canada | https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health.html |

Meta-analysis of prevalence was performed using Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation to adjust for variance instability [9]. Owing to anticipated between-study heterogeneity, random-effect model was used [6]. Furthermore, pooled risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived to characterise the association between cancer and the occurrence of severe disease. Between-study heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic [5]. A leave-one-out sensitivity analyses assessed the stability of pooled estimates. We applied meta-regression to determine whether the pooled prevalence was moderated by the age of study participants, gender distribution or location of the study (in/outside of China). All analyses were conducted using Stata SE software version 16 (StataCorp, TX, USA). A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

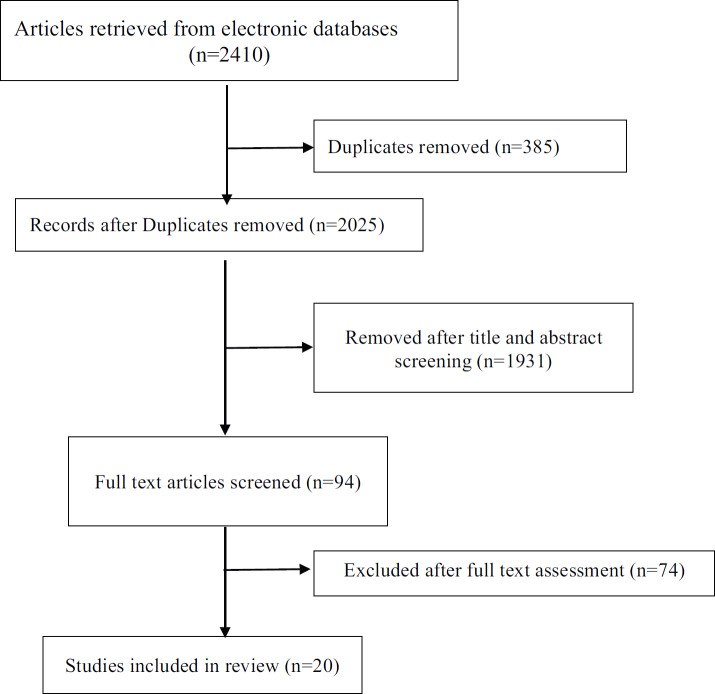

The electronic searches retrieved 2,410 citations. Following removal of duplicates and screening of titles and abstracts, 94 articles were selected for full text evaluation. Twenty articles were retained after full-text assessment (Figure 1) [10–29]. The included studies were from China (n = 10), the United Kingdom (n = 2), South Korea (n = 1), the United States (n = 2), Italy (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), India (n = 1), France (n = 1) and Thailand (n = 1). The studies involved a total of 32,404 patients. The mean age ranged from 40.3 to 75.0 years and 18.0% to 67.1% of the patients were females (Table 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart of studies selection process.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Study No. | Author details** | Country (location) |

Hospital | Last follow up | Sample size | Mean age | % Female |

No. (%) with cancer |

No. (%) severe diseasea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer patients | Non-cancer | |||||||||

| 1. | COVID-19 National Emergency Response Center, Epidemiology and Case Management Team, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [10] | South Korea | Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | February 14, 2020 | 28 | 42.6 | 46.4 | 1 (3.6) | - | - |

| 2. | ICNARC [11] | United Kingdom |

England, Wales and Northern Ireland critical care units | March 26, 2020 | 775a | 60.2 | 29.1 | 12 (1.2) | - | - |

| 3. | Wu et al [12] | China (Jiangsu) | 3 grade IIIA hospitals | February 14, 2020 | 80 | 46.1 | 51.3 | 1 (1.3) | - | - |

| 4. | The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team [13] | China | Nationwide | February 11, 2020 | 20982b | - | 48.6 | 107 (0.5) | 6 (5.6) | 400 (1.9) |

| 5. | Zhu et al [14] | China (Outside of Hubei) | Anhui Province ED | February 20, 2020 | 32 | 46.0 | 53.0 | 2 (6.3) | - | - |

| 6. | Sun et al [15] | Singapore | National Centre for Infectious Diseases |

February 16, 2020 | 54 | 42.0 | 46.3 | 0 (0.0) | - | - |

| 7. | Chen et al [16] | China (Wuhan) | Tongji Hospital | February 28, 2020 | 274 | 62.0 | 38.0 | 7 (3.0) | 5 (71.4) | 108 (40.4) |

| 8. | Guo et al [17] | China (Wuhan) | No. 7 Hospital of Wuhan | February 23, 2020 | 187 | 58.5 | 51.3 | 13 (7.0) | - | - |

| 9. | McMichael et al [18] | US (Washington) | skilled nursing facility in King County | March 18, 2020 | 167 | 72.0 | 67.1 | 15 (9.0) | - | - |

| 10. | Gupta et al [19] | India (New Delhi) | Sarfdarjung hospital | March 19, 2020 | 21 | 40.3 | 33.3 | 0 (0.0) | - | - |

| 11. | Klopfenstein et al [20] | France | NFC hospital | March 17, 2020 | 54 | 47.0 | 67.0 | 2 (4.0) | - | - |

| 12. | Richardson et al [21] | US (New York) | Northwell Health hospitals | April 4, 2020 | 5700 | 63.0 | 39.7 | 320 (6.0) | - | - |

| 13. | Pan et al [22] | China (Hubei) | Wuhan Hanan Hospital, Wuhan Union Hospital, and Huanggang Central Hospital | March 18, 2020 | 204 (digestive =103) |

52.9 | 52.5 | 13 (6.37) | 4 (50.0)c | 33 (34.7)c |

| 14. | Pongpirul et al [23] | Thailand | Bamrasnaradura Infectious Diseases Institute | January 31, 2020 | 11 | 61.0 | 45.5 | 0 (0) | - | - |

| 15. | Feng et al [24] | China (Multicentre) |

Jinyintan Hospital in Wuhan, Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center in Shanghai and Tongling People’s Hospital in Anhui Province | February 15, 2020 | 476 | 53.0 | 43.1 | 12 (2.5) | 7 (58.3) | 117 (25.2) |

| 16. | Yu et al [5] | China (Wuhan) | Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University | February 17, 2020 | 1524 | - | - | 12 (0.79) | - | - |

| 17. | Grasselli et al [26] | Italy (Lombardy) | 72 hospitals | March 18, 2020 | 1591a | 63.0 | 18.0 | 81 (8.0) | - | - |

| 18. | Wang et al [27] | China (Wuhan) | Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University | February 13, 2020 | 116 | 54 | 42.2 | 12 (10.3) | 11 (91.6) | 58/104 |

| 19. | Chu et al [28] | China (Wenzhou city) | First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University | February 23, 2020 | 33a | 65.2 | 33.3 | 1 (3.0) | - | - |

| 20. | Tomlins et al [29] | UK (England) | North Bristol NHS Trust | March 30, 2020 | 95 | 75.0 | 37.0 | 20 (21) | 3 (15.0) | 17 (22.7) |

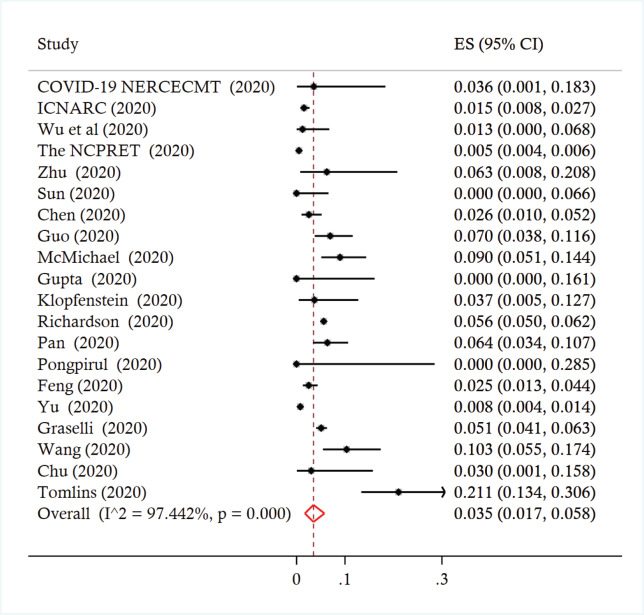

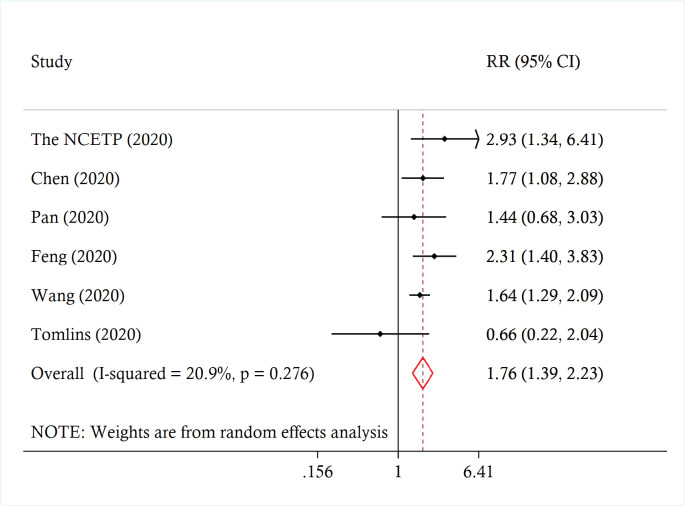

Across the studies, the reported prevalence of cancer ranged from 0% to 21.0%. The pooled prevalence was 3.5% (95% CI 1.7 to 5.8%, I2 = 97.4%) (Figure 2). A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis did not change the results (point estimate ranged from 3% to 4%). There was no significant moderation of the pooled prevalence by the participants’ mean age (coefficient = 0.0034, p = 0.247), proportion of females (coefficient = 0.0006, p = 0.557) or being conducted in/outside of China (coefficient = −0.009, p = 0.795). Across six studies involving 22,046 patients, those with cancer were more likely to experience severe disease compared to patients without cancer (pooled risk ratio (RRpooled) 1.76, 95% CI 1.39 to 2.23, I2 = 20.9%) (Figure 3). A leave-one-out analyses did not change the results (the estimates ranged from RRpooled 1.66 (95% CI 1.27 to 2.17) to 1.82 (95% CI 1.26 to 2.64)).

Figure 2. Forest plot of prevalence of cancer among patients infected with COVID-19.

Figure 3. Forest plot of association between cancer and severe disease among COVID-19 patients.

Discussion

The results of our meta-analysis suggest a low prevalence of cancer among COVID-19 patients. However, patients with cancer are 76% more likely to experience severe disease compared to those without cancer. This finding is consistent with a recent study which reported that the fatality of cancer patients infected with the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV in 2012 was significantly higher compared to patients without cancers [31]. The greater likelihood of severe COVID-19 in patients with cancer may reflect their increased vulnerability to developing complications of respiratory viruses [32]. Moreover, many oncology patients often have additional risk factors for severe COVID-19, such as advanced age and presence of other comorbidities [32].

Our study highlights the need to implement extra precautionary measures (including an awareness campaign) to ensure that patients with cancer are not exposed to the virus during the current outbreak and future outbreaks. The development of a COVID-19 vaccine or treatment modality may also be useful towards reducing the risk of this vulnerable population. Furthermore, it is imperative that during the current COVID-19 outbreak, measures are implemented to minimise interruptions in the provision of essential medical services to cancer patients.

Of note, as expected given the observational nature of the data, there was evidence of high statistical heterogeneity in the pooled prevalence of cancer. This does not necessarily invalidate the findings. Further assessment revealed that the heterogeneity was not entirely explained by differences in age or gender distribution among study population. Also, while the included studies originated from a few countries, around half were conducted in China which may affect the generalisability of our findings. Hence, further analysis would be necessary as the COVID-19 pandemic evolves and data from other regions become available.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that COVID-19 patients with cancer are more likely to experience severe disease than those without cancer. This emphasises the need to adopt additional precautionary measures to ensure that these vulnerable patients are not exposed to the virus, and if they become infected, extra attention should be provided to minimise their risk of adverse outcomes.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Supplementary material

References

- 1.The Center for Systems Sciences and Engineering, John Hopkins University. Coronavirus COVID 19 Global cases. [29/03/20]. [ https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6]

- 2.European Centre for Disease prevention and control (ECDC) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK – seventh update. 2020. [29/03/20]. [ https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/RRA-seventh-update-Outbreak-of-coronavirus-disease-COVID-19.pdf]

- 3.Desai A, Sachdeva S, Parekh T, et al. COVID-19 and cancer: lessons from a pooled meta-analysis. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:557–559. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalathil SG, Thanavala Y. High immunosuppressive burden in cancer patients: a major hurdle for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65(7):813–819. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1810-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2019. version 6.0 (updated July 2019) Cochrane, 2019 [ www.training.cochrane.org/handbook] [DOI]

- 7.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2012. [ http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp]

- 9.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.COVID-19 National Emergency Response Center, Epidemiology and Case Management Team, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of 28 Cases of Coronavirus Disease in South Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020;11(1):8–14. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.1.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ICNARC report on COVID-19 in critical care 27 March 2020. [27/03/20]. [ https://www.icnarc.org/About/Latest-News/2020/03/27/Report-On-775-Patients-Critically-Ill-With-Covid-19]

- 12.Wu J, Liu J, Zhao X, et al. Clinical characteristics of imported cases of COVID-19 in Jiangsu Province: a multicenter descriptive study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. pii: ciaa199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. Vital Surveillances: The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) — China, 2020. China CDC Weekly. 2020;2(8):113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu W, Xie K, Lu H, et al. Initial clinical features of suspected coronavirus disease 2019 in two emergency departments outside of Hubei, China. J Med Virol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Sun Y, Koh V, Marimuthu K, et al. Epidemiological and clinical predictors of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Chen T, Wu T, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.McMichael TM, Currie DW, Clark S, et al. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N Engl J Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Gupta N, Agrawal S, Ish P, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic profile of the initial COVID-19 patients at a tertiary care centre in India. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2020;90(1) doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2020.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klopfenstein T, Kadiane-Oussou NJ, Toko L, et al. Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Med Mal Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.04.006. pii: S0399-077X(20)30110-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Pan L, Mu M, Yang P, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with digestive symptoms in Hubei, China: a descriptive, cross-sectional, multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115 doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pongpirul WA, Mott JA, Woodring JV, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(7) doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Y, Ling Y, Bai T, et al. COVID-19 with different severity: a multi-center study of clinical features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Graselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Wang L, Li X, Chen H, et al. Coronavirus disease 19 infection does not result in acute kidney injury: an analysis of 116 hospitalized patients from Wuhan, China. Am J Nephrol. 2020. pp. 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Chu Y, Li T, Fang Q, et al. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. J Infect. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Tomlins J, Hamilton F, Gunning S, et al. Clinical features of 95 sequential hospitalised patients with novel coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19), the first UK cohort. J Infect. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Jazieh AR, Alenazi TH, Alhejazi A, et al. Outcome of oncology patients infected with coronavirus. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:471–475. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hicks KL, Chemaly RF, Kontoyiannis DP. Common community respiratory viruses in patients with cancer: more than just “common colds”. Cancer. 2003;97(10):2576–2587. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinkove R, McQuilten Z, Adler J, et al. Managing haematology and oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim consensus guidance. Med J Aust. 2020. [ https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/212/10/managing-haematology-and-oncology-patients-during-covid-19-pandemic-interim] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]