Abstract

Invasive stratified mucin-producing carcinoma (ISMC) is a recently described tumor with similar morphology to stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion (SMILE). SMILE and ISMC likely arise from HPV-infected reserve cells in the cervical transformation zone that retain their pluripotential ability to differentiate into various architectural and cytological patterns. This is important, as small studies have suggested that ISMC may be a morphologic pattern associated with more aggressive behavior than usual HPV-associated adenocarcinoma. We sought to study the morphologic spectrum of this entity and its associations with other, more conventional patterns of HPV-associated carcinomas.

Full slide sets from 52 cases of ISMC were reviewed by an international panel of gynecological pathologists and classified according to the new International Endocervical Criteria and Classification system. Tumors were categorized as ISMC if they demonstrated stromal invasion by solid nests of neoplastic cells with at least focal areas of mucin stratified throughout the entire thickness, as opposed to conventional tall columnar cells with luminal gland formation. Tumors comprising pure ISMC, and those mixed with other morphologic patterns, were included in the analysis.

Twenty-nine pure ISMCs (56%) and 23 ISMCs mixed with other components (44%) were identified. Other components included 13 cases of usual-type adenocarcinoma, 6 adenosquamous carcinoma, 3 mucinous-type adenocarcinoma, 1 high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma. ISMC displayed architectural diversity (insular, lumen-forming, solid, papillary, trabecular, micropapillary, single cells) and variable cytologic appearance (eosinophilic cytoplasm, cytoplasmic clearing, histiocytoid features, glassy cell-like features, signet ring-like features, bizarre nuclei, squamoid differentiation). Awareness of the spectrum of morphologies in ISMC is important for accurate and reproducible diagnosis so that future studies to determine the clinical signficance of ISMC can be conducted.

Keywords: Invasive stratified mucin-producing carcinoma, ISMC, Stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion, SMILE, Morphology

Introduction

Stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion (SMILE), initially described in 2000 by Park et al.,1 is a pre-invasive neoplasm of the uterine cervix, thought to arise from the reserve cells of the transformation zone.1,2 It consists of cells containing mucin in the form of cytoplasmic clearing or discrete cytoplasmic vacuoles stratified throughout the entire epithelial thickness, and is included in the 2014 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of Female Reproductive Organs as a variant pattern of endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS).3 SMILE is characterized by hybrid morphology without classic gland formation and can resemble high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), often coexisting with HSIL and AIS which are associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection.1,2,4–7 SMILE has also been reported in association with invasive carcinomas such as adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), believed by some investigators to represent phenotypic instability.2,4–7

Invasive stratified mucin-producing carcinoma (ISMC) was described in 2016 by Lastra et al.8 as a morphologic variant of endocervical adenocarcinoma (ECA), with similar morphology to SMILE, its putative precursor. The few studies evaluating ISMC have suggested that this tumor subtype is potentially more aggressive, with worse outcomes compared to usual-type endocervical adenocarcinoma (UEA)8–10 and with a substantial risk of distant metastatic disease, especially to the lungs.9 These initial results are based on small retrospective studies and though ISMC was shown to have worse disease free and disease specific survival on univariate analysis in the Hodgson paper, the significance was lost on multivariate analysis.10 It remains to be seen if ISMC is a truly bad actor as compared to UEA, but they do seem to present at higher stage, which could account for the worse outcomes.

ISMC is recognized as a mucinous subtype of HPV-associated adenocarcinoma by the International Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Criteria and Classification (IECC) system,11 which classifies endocervical adenocarcinomas into two main categories based on morphologic features: HPV–associated (HPVA) and non-HPV-associated (NHPVA). In our previous IECC publication, all tested ISMCs were high-risk HPV- mRNA-positive by in-situ hybridization (7/7 cases), and 8/8 cases tested for p16 showed block-like positivity. Unlike other HPVA adenocarcinomas, ISMCs more frequently showed mutation-type p53 staining (28.5%) and, less frequent PAX8 labeling.11, 12

Because of its phenotypic plasticity, ISMC can simulate other tumor types. For example, our group recently reported that ISMC is a frequent diagnostic mimic of ASC, a tumor which by definition has distinct squamous and glandular components.12 Of 59 cases originally diagnosed as ASC in the prior study, 9 were reinterpreted as pure ISMC and 10 as ISMC with other components (e.g. mixed with usual-type HPV-associated adenocarcinoma). This is an important distinction since there have been prior studies showing worse prognosis of adenosquamous carcinoma compared to adenocarcinoma.13 When ISMCs were removed from our group of ASC, the clinical profiles were similar to HPV-associated adenocarcinomas, such as age, symptoms, macroscopy and FIGO stage at diagnosis.12

Given the limited morphological data in the literature regarding ISMC, and the importance of diagnostic accuracy in recognizing this potentially aggressive entity, we sought to better characterize its morphologic spectrum and association with other histotypes.

Materials and Methods

Institutional approval for this study was obtained from each of the participating centers.

Case selection

Slides from 52 cases of ISMCs were collected from 10 institutions (USA: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [MSKCC], New York, NY, and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; Romania: University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology of Târgu Mureș, and Regional Institute of Oncology, Iasi; Japan: Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo; Mexico: Hospital de Oncología Mexico City, Mexico City; Israel: Sheba Medical Center, Tel- Hashomer, Ramat Gan; Italy: Ospedale Sacro Cuore Don Calabria, Negrar; Canada: Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center, Toronto; Germany: University Hospital Leipzig, Leipzig). The cases from Toronto and Leipzig were reviewed by four authors (KJP + CPH + RAS and KJP + LCH, respectively). The remaining cases were reviewed by an international panel of experienced pathologists from the submitting institutions.

Morphologic assessment

In the internationally reviewed cases, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides containing tumor (an average of 12 slides per case) were examined at a multiheaded microscope. A consensus diagnosis was reached in every case, with at least two and as many as four study pathologists reviewing slides. The cases from Toronto and Leipzig were initially reviewed by the submitting authors, and subsequently reviewed and confirmed by RAS and/or KJP. The 52 study cases were classified according to the IECC system. Invasive stratified mucin-producing carcinoma was diagnosed in the presence of a stromal-invasive carcinoma composed of nests filled with stratified tumor cells containing intracytoplasmic mucin, similar to the in-situ counterpart (SMILE). For the purposes of this study, pure ISMC was classified separately from ISMC mixed with other HPV-associated components (ISMCmixed) such as UEA, mucinous not otherwise specified (MUC), ASC and neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC). Tumors were classified as mixed if the ISMC portion constituted ≥10% but <90% of the entire tumor. Cases where ISMC represented <10% of the entire tumor were excluded. Other architectural and cytologic features were noted when observed: insular, solid, papillary, micropapillary, extravasated mucin, single cell; the quality of the cytoplasm was characterized (mucinous, eosinophilic, clear) as was the presence and nature of inflammatory infiltrates. Tumors were subsequently categorized as having Silva A, B or C pattern of invasion. Briefly, Silva pattern A is composed of well-demarcated glands with rounded contours arranged in a preserved lobular configuration, without destructive stromal invasion, single cells or lymph-vascular invasion (LVI). Pattern B tumors have only “limited” destructive stromal invasion in a background of pattern A, defined by stromal-invasive small clusters or individual tumor cells in a focally desmoplastic stroma, often with an inflammatory infiltrate. Pattern C is characterized by diffusely destructive stromal invasion by glands associated with a desmoplastic stromal reaction.14 The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, status of lymph node metastases (LNM) and association with precursor lesions (such as SMILE, in situ adenocarcinoma or high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion HSIL) were recorded in all cases.

Results

A total of 29 pure ISMC (56%) (Fig. 1) and 23 ISMCmixed (44%) cases were identified. Patients’ ages ranged from 22–78 years, but most cases (75%) occurred in patients under 50. Most tumors (36) were 2009 FIGO stage I (70%), 5 cases were FIGO stage II (9.6%), 6 cases were FIGO stage III (11.5%) and 1 case was FIGO stage IV (1.9%). Staging data was unavailable in 4 cases. Among the ISMCmixed tumors, 13 cases contained UEA, 6 contained ASC, 3 contained MUC, and 1 had an NEC component. Most cases (92%) were Silva C pattern (both ISMC and ISMCmixed). Only 2 cases were Silva A (both pure ISMC) and 2 cases were Silva B (1 pure ISMC, and 1 ISMCmixed). One-third of cases presented with LNM. All FIGO stage III and IV carcinomas had LNM, while 20% of stage II and 14% of stage I ISMCs demonstrated LNM. Seven cases were associated with SMILE, 4 cases with HSIL, 6 cases with conventional in situ adenocarcinoma, 12 cases with a combination of these; and in 23 cases the in situ component was not identified, most probably being overgrown by the invasive component.

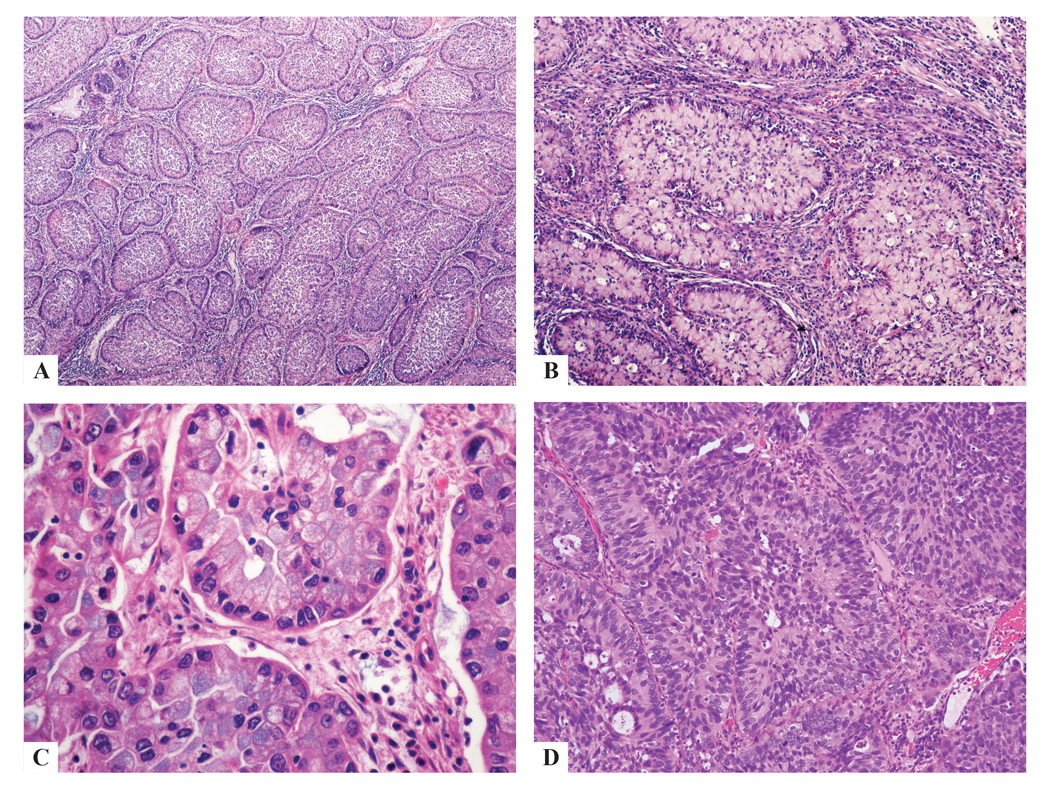

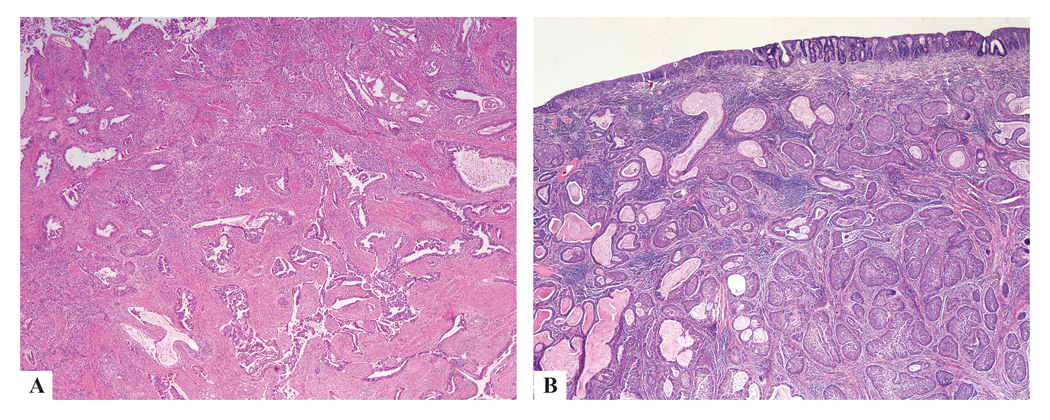

Figure 1:

Pure ISMC classically shows nests of stratified columnar cells with nuclear palisading along the periphery of the nests (a-d), with variable amounts of intracytoplasmic mucin ranging from mucin-rich (a-c) to mucin-poor (d); nuclei were unifrom, small, round-to-ovoid with inconspicuous nucleoli (b-d).

Typical histologic appearance of ISMC

Pure ISMC cases classically showed nests of stratified mucinous cells, with round/ovoid, slighly irregular nuclei, no prominent nucleoli, and nuclear peripheral palisading, infiltrating cervical stroma. Mucin vacuoles were seen throughout the nests in variable amounts, from “mucin-rich” (abundant cytoplasmic mucin) to “mucin-poor” (reduced cytoplasmic mucin). Apoptotic bodies and mitoses (characteristic for HPV infection) and peri- and intratumoral neutrophilic infiltrates, sometimes exuberant, were recognized in all cases (Fig. 1).

Spectrum of histologic features of ISMC

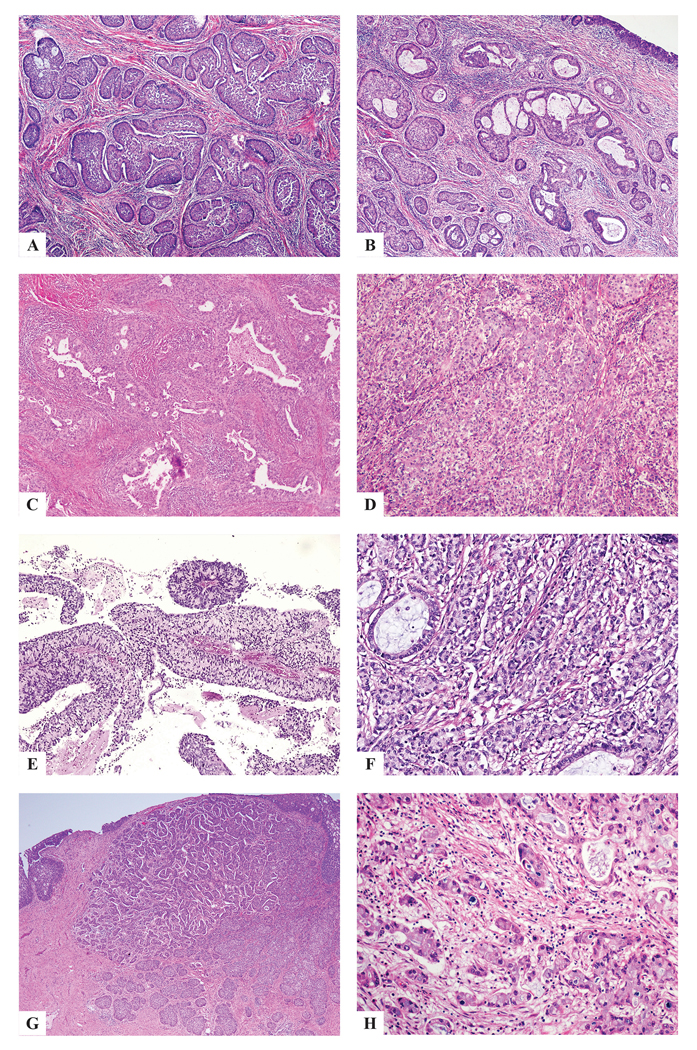

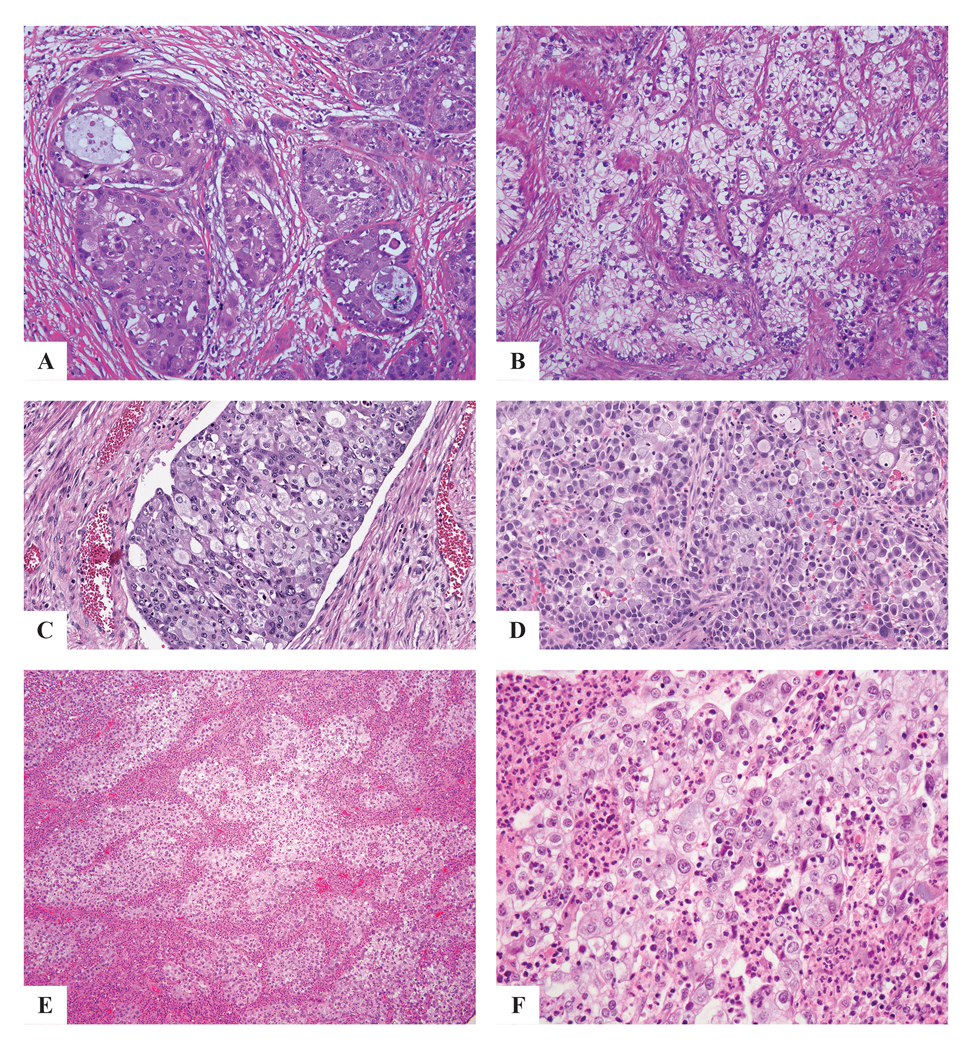

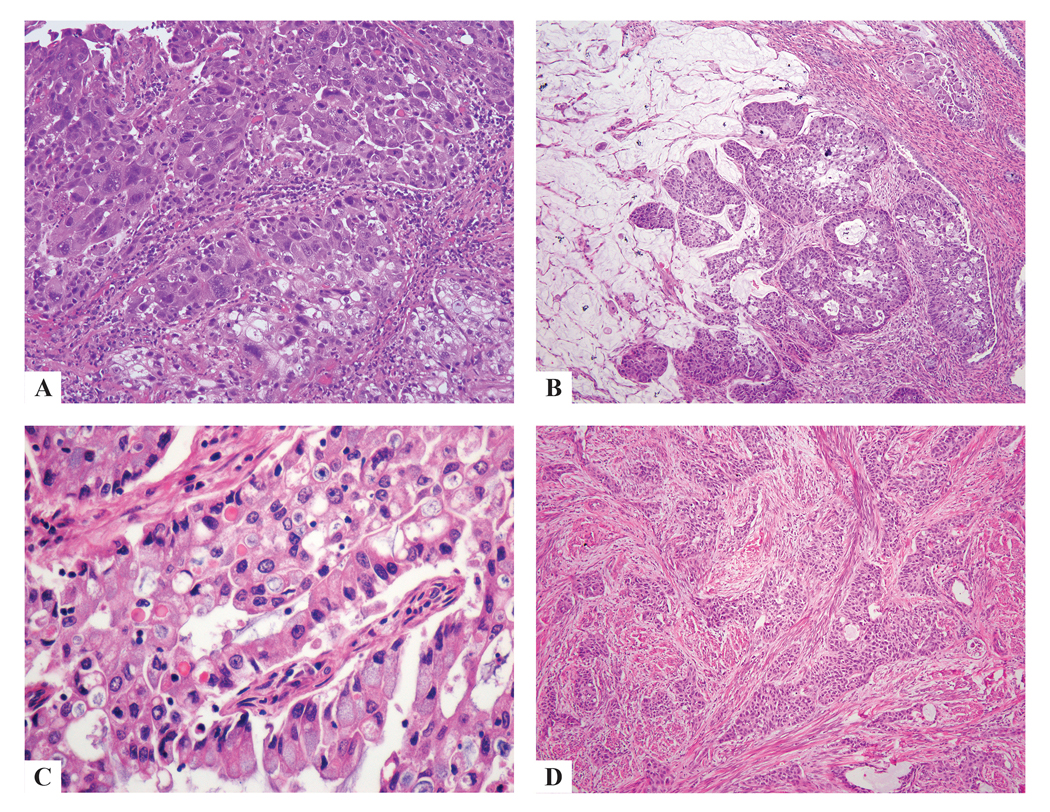

Every case demonstrated classic ISMC morphology (at least 10% of the tumor by our definition) and the various architectural patterns were noted: insular (50 cases), glandular (15 cases), solid (10 cases), papillary (1 case), trabecular (8 cases), micropapillary (2 cases) and single cell (9 cases) with variable amounts of stroma (Fig. 2). There was also cytologic variability: tumor cells usually had intracytoplasmic mucin but also showed delicate eosinophilic cytoplasm (7 cases), cytoplasmic clearing (2 cases), histiocytoid (2 cases), glassy cell-like (1 case) and signet ring-like features (2 cases) (Fig. 3). Other features noted in these tumors included bizarre nuclear atypia (3 cases), squamoid differentiation in the form of cells with dense eosinophilic cytoplasm lacking intercellular bridges and keratinization (1 case), extravasated pools of mucin (3 cases), and hyaline-like globules (1 case) (Fig. 4). These findings were present in various combinations, although not every tumor showed all of the features.

Figure 2:

ISMC with architectural diversity: insular (a), gland- or lumen-forming (b,c), solid (d), papillary (e), trabecular (f), micropapillary (g) single cells (h).

Figure 3:

ISMC with cytologic diversity: eosinophilic cytoplasm (a), cytoplasmic clearing (b), histiocytoid features (c), signet ring-like features (d), glassy cell-like features with infiltrating neutrophils and eosinophils (e,f).

Figure 4:

ISMC presenting bizarre nuclear atypia (a), extravasated pools of mucin (b), hyaline-like globules (c) squamoid differentiation (d).

ISMC mixed with other histologies

ISMC was mixed with UEA, as well as conventional AIS and SMILE (Fig. 5). The UEA and ISMC components were generally distinct and separate, though in areas they appeared to fuse with lumen formation within the ISMC nests (Fig. 5).

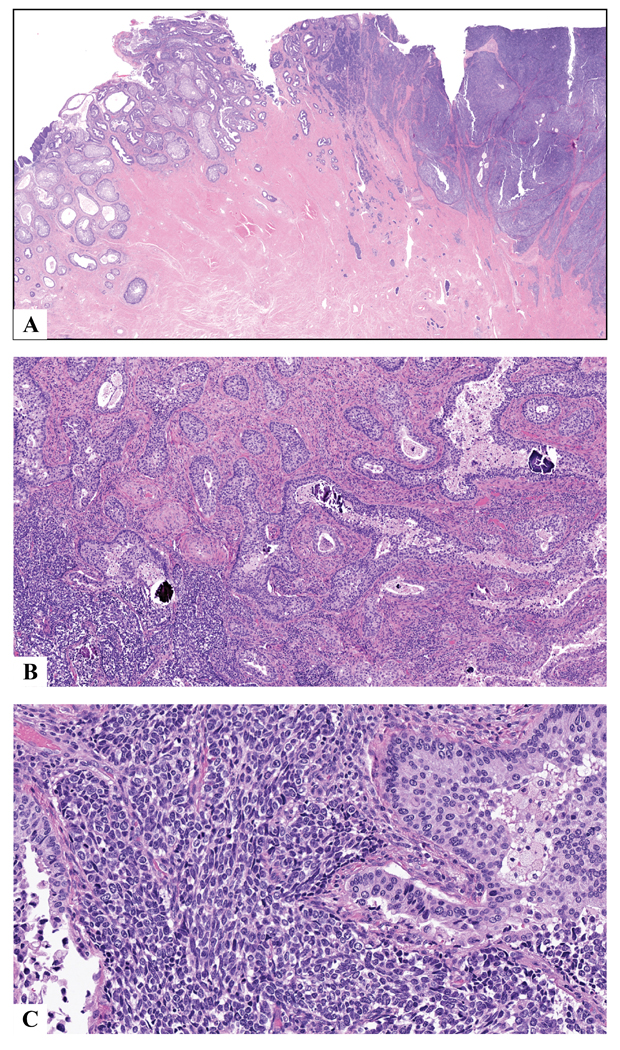

Figure 5:

ISMC with UEA showing distinct separation, as well as areas of intimate intermingling of both components (a), and some foci showing lumen formation within ISMC nests, with overlying AIS and SMILE (b).

The 1 case of ISMC with high-grade NEC showed that the two components were mostly separate and distinct, with mixture of the elements at the junction (Fig. 6). The neuroendocrine tumor had features of both small cell carcinoma (small blue nuclei with minimal cytoplasm) and large cell NEC (ample cytoplasm with prominent nucleoli), which in areas showed intimate admixture with adenocarcinoma (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the ISMC component showed areas of intratumoral psammomatous calcifications (Fig. 6).

Figure 6:

ISMC (left) with high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (right) showing distinct separation of the two components except at the junction in the middle where the two component intermingle (a). Tumors at the junction with some foci showing psammomatous calcifications in ISMC nests (b). The neuroendocrine component is a mixture of small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, with cells ranging from small blue with minimal cytoplasm to more prominent cytoplasm with open chromatin and prominent nucleoli (c).

Discussion

ISMC is a recently described morphologic variant of endocervical adenocarcinoma, likely arising from HPV-infected reserve cells of the cervix that retain their pluripotential ability to differentiate into various architectural and cytological patterns. This phenotypic plasticity has resulted in this tumor being classified as something other than a mucinous adenocarcinoma in the past. Moreover, ISMC has been reported to have a poorer prognosis than other histologic subtypes of HPV-associated endocervical adenocarcinoma, albeit in small limited series.

Initially described by Lastra et al., ISMC is characterized by invasive nests of tumor cells with peripheral palisading, variable amounts of intracytoplasmic mucin or clear vacuoles stratified throughout its entire thickness.8 Intraepithelial neutrophilic infiltrates, apoptotic bodies and frequent mitotic figures are common and are easily identified.8 A “mucin-poor” ISMC has also been described, which shows similar morphologic features but reduced intracytoplasmic mucin.8

ISMC may occur in pure form or may be associated with usual-type or mucinous adenocarcinoma, ASC or NEC. Lastra et al.8 described 7 pure ISMC and 1 usual-type adenocarcinoma with an ISMC component. In the present study, we desribe 29 cases of pure ISMC and 23 cases of ISMC coexisting with other carcinoma subtypes. In both pure ISMC and ISMCmixed, the tumor can display a wide morphologic spectrum that can impart an ambiguous appearance and make it difficult to classify the tumor.

The exact incidence of ISMC is not known since this is a newly described entity. In our prior study, ISMCs were diagnosed as ASC (including glassy cell-type and mucoepidermoid type), SCC, or various subtypes of adenocarcinoma of the cervix.12 ISMC may be difficult to distinguish from traditional poorly differentiated HPV-associated usual- or mucinous-type adenocarcinoma, and in fact it may not always be possible to make a clear distinction. All three variants share easily identifiable apoptotic bodies and mitotic figures at scanning magnification with intracytoplasmic mucin, although the amount of mucin differs from one lesion to another based on IECC definitions.11 In ISMC, however, islands of tumor cells show a characteristic peripheral nuclear palisade in most cases, even if only in parts of the tumor, a feature not seen in the other entities. Furthermore, p40 and p63 are often expressed in the peripheral cells of the tumor cell nests (regardless of the presence of palisading), and p53 more commonly shows mutation-type labeling.12

Micropapillary architecture associated with ISMC may resemble serous carcinoma. This is important because most gynecologic pathologists now believe that primary serous carcinoma of endocervix is extraordinarily rare or nonexistent.11 The presence of a p53-mutated and HPV-negative serous carcinoma in the cervix most likely derives from a coexistent endometrial or adnexal serous carcinoma. A recent paper by Alvarado-Cabrero described endocervical micropapillary adenocarcinoma as a variant pattern of invasive adenocarcinoma, microscopically represented by small, tightly cohesive papillary groups of neoplastic cells, with eosinophilic cytoplasm, atypical nuclei and surrounded by clear spaces resembling vascular channels. This pattern is seen usually in association with HPV infection, wild p53 expression and is associated with LNM and poor clinical outcomes.15 The micropapillary pattern may occur in association with a variety of ECA subtypes, and we report this pattern with ISMC for the first time. To differentiate micropapillary HPV associated cervical adenocarcinoma from serous carcinoma of the endometrium or adnexa, HPV testing by RNA in situ hybridization (RISH) would be the most expeditious ancillary test, as we have shown previously the high sensitivity and specificity of RISHt.11 p16 would not necessarily be useful since it is usually diffuse and strong in both ISMC and serous carcinoma; p53 would only be useful if it has a wild type pattern since aberrant p53 can be seen in ISMC.

Several cases in our study had focal to extensive areas of tumor cells with cytoplasmic clearing, atypical and bizarre nuclei, and hyaline-like globules. Some of these areas were solid while others were papillary in architecture, all of which led to consideration of clear cell carcinoma (CCC). CCC is a rare, HPV-independent neoplasm with characteristic solid, papillary and/or tubulocystic architecture composed of cuboidal, hobnail or flattened cells with clear and/or eosinophilic cytoplasm.16 Immunohistochemistry might be helpful in this setting, as CCC is usually positive for HNF-1β and Napsin A. However, caution must be exercised; in a previous study from our group, HNF-1β did not have the anticipated discriminatory power for CCC and was found to be positive in other subtypes of ECA, including ISMC.17 A better ancillary test would be HPV in-situ hybridization (mRNA), as CCC is negative for HPV.

Some tumors have glassy cell features or areas of squamoid differentiation, which may make them difficult to differentiate from ASC of the cervix, as discussed above.12 Tumor cells with glassy cell features are characterised by sharp cytoplasmic margins, “ground glass” eosinophilic cytoplasm, large round/ovoid nuclei with prominent nucleoli; those with squamoid differentiation have dense eosinophilic cytoplasm but lacks intercellular bridges and keratinization. The frequent positivity of ISMC for MUC6 supports glandular differentiation, while patchy p40 and p63 in the peripheral cells of the same nests support some degree of primitive squamous differentiation. In contrast, ASC contains distinctive components of glandular and squamous neoplasia that are readily appreciated using H&E stains only.12 SCC, the most common malignant tumor of the cervix, should be considered in the differential diagnosis with ISMC because of the frequently nested growth pattern in both, and cytoplasmic clearing due to glycogenation in the former. The presence of intercellular bridges, keratinization, and diffuse expression of p63 and p40 support a diagnosis of SCC.

In this study, 30% of ISMCs were FIGO stage II or higher, in contrast to UEAs (of which 14% were stage II or higher in a prior study).18 We also found that ISMC more frequently exhibits diffusely destructive stromal invasion (Silva Pattern C) compared to UEA (92% versus 76%).19 Silva pattern C is frequently associated with disease recurrence (22%) and death from disease (8%),14 all of which suggests that ISMC may be an aggressive variant of HPV-associated endocervical adenocarcinoma. This has been studied by other groups, but the cohort sizes were relatively limited. 8–10 The true significance of ISMC morphology, either in pure form or as part of a mixed tumor, is yet to be determined, but preliminary studies suggest that the specific morphology may belie an underlying mechanism that results in worse outcome, not unlike other aggressive tumors with well-defined histology (e.g. small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, gastric type endocervical adenocarcinoma).

In conclusion, ISMC is a recently described cervical tumor that can display a wide morphologic spectrum mimicking different malignant tumors of the cervix, with an unusual immunohistochemical profile. It is important to recognize the morphologic spectrum of ISMC, as these are potentially aggressive tumors compared with usual-type adenocarcinoma; they are diagnosed at higher stages, and more frequently demonstrate destructive stromal invasion.

In order to better understand the significance of ISMC morphology with respect to outcomes, additional studies and more detailed data are needed. This requires reproducible recognition of this morphologic variant, which we have attempted to provide in this study.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Soslow reports the following, outside the submitted work: personal fees from Ebix/Oakstone (preparation of recorded lectures); personal fees from Cambridge University Press (royalties); personal fees from Springer Publishers (royalties); personal fees from Roche (one lecture).

Funding: This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 (Dr. Soslow, Dr. Park).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Park JJ, Sun D, Quade BJ, Flynn C, Sheets EE, Yang A, McKeon F, Crum CP. Stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesions of the cervix: adenosquamous or columnar cell neoplasia? Am J Surg Pathol. 2000; 24:1414–1419. DOI: 10.1097/00000478-200010000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle DP, McCluggage WG. Stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion: report of a case series with associated pathological findings. Histopathology. 2015; 66: 658–663. DOI: 10.1111/his.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoler M, Bergeron C, Colgan TJ, et al. Tumours of the Uterine Cervix In: Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, et al. , editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs, 4th Edition Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2014. p 184. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onishi J, Sato Y, Sawaguchi A, Yamashita A, Maekawa K, Sameshima H, Asada Y. Stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion with invasive carcinoma: 12 cases with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural findings. Hum Pathol. 2016. September; 55:174–181. DOI: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwock J, Ko HM, Dubé V, Rouzbahman M, Cesari M, Ghorab Z, Geddie WR. Stratified Mucin-Producing Intraepithelial Lesion of the Cervix: Subtle Features Not to Be Missed. Acta Cytol. 2016; 60:225–231. DOI: 10.1159/000447940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park KJ, Soslow RA. Current concepts in cervical pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009; 133:729–738. DOI: 10.1043/1543-2165-133.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Backhouse A, Stewart CJ, Koay MH, Hunter A, Tran H, Farrell L, Ruba S. Cytologic findings in stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion of the cervix: A report of 34 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016; 44:20–25. DOI: 10.1002/dc.23381. Epub 2015 Oct 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lastra RR, Park KJ, Schoolmeester JK. Invasive stratified mucin producing carcinoma and stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion (SMILE): 15 cases presenting a spectrum of cervical neoplasia with description of a distinctive variant of invasive adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016; 40:262–269. DOI: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horn LC, Handzel R, Borte G, Siebolts U, Haak A, Brambs CE. Invasive stratified mucin-producing carcinoma (i-SMILE) of the uterine cervix: report of a case series and review of the literature indicating poor prognostic subtype of cervical adenocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019; 145:2573–2582. DOI: 10.1007/s00432-019-02991-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodgson A, Olkhov-Mitsel E., Howitt BE, Nucci MR, Parra-Herran C. International endocervical adenocarcinoma criteria and classification (IECC): correlation with adverse clinicopathological features and patient outcome. J Clin Pathol. 2019; 72: 347–353. DOI: 10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stolnicu S, Barsan I, Hoang L, Patel P, Terinte C, Pesci A, Aviel-Ronen S, Kiyokawa T, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Pike MC, Oliva E, Park KJ, Soslow RA. International endocervical adenocarcinoma criteria and classification (IECC): a new pathogenetic classification for invasive adenocarcinomas of the endocervix. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42:214–226. DOI: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stolnicu S, Hoang L, Hanko-Bauer O, Barsan I, Terinte C, Pesci A, Aviel-Ronen S, Kiyokawa T, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Oliva E, Park KJ, Soslow RA. Cervical adenosquamous carcinoma: detailed analysis of morphology, immunohistochemical profile, and clinical outcomes in 59 cases. Mod Pathol. 2019. February;32(2):269–279. DOI: 10.1038/s41379-018-0123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Lee JY, Lee C, Hahn S, Kim MA, Kim HS, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS. Prognosis of adenosquamous carcinoma compared with adenocarcinoma in uterine cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014; 24(2):289–294). DOI: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz De Vivar A,Roma AA,Park KJ,Alvarado-Cabrero I,Rasty G,Chanona-Vilchis JG,Mikami Y,Hong SR,Arville B,Teramoto N,Ali-Fehmi R,Rutgers JK,Tabassum F,Barbuto D,Aguilera-Barrantes I,Shaye-Brown A,Daya D, Silva EG. Invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma: proposal for a new pattern-based classification system with significant clinical implications: a multi-institutional study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013; 32:592–601. DOI: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31829952c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarado-Cabrero I, McCluggage WG, Estevez-Castro R, Perez-Montiel D, Stolnicu S, Ganesan R, Vella J, Castro R, Canedo-Matute J, Gomez-Cifuentes J, Rivas-Lemus VM, Park KJ, Soslow RA, Oliva E, Valencia-Cedillo R. Micropapillary cervical adenocarcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019; 43:802–809. DOI: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young RH, Scully RE. Oxyphilic clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. A report of nine cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987; 11:661–677. DOI: 10.1097/00000478-198709000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stolnicu S, Barsan I, Hoang L, Patel P, Chririboga L, Terinte C, Pesci A, Aviel-Ronen S, Kiyokawa T, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Pike MC, Oliva E, Park KJ, Soslow RA. Diagnostic algorithmic proposal based on comprehensive immunohistochemical evaluation of 297 invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42:989–1000. DOI: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stolnicu S,Hoang L,Chiu D,Hanko-Bauer O,Terinte C,Pesci A,Aviel-Ronen S7,Kiyokawa T,Alvarado-Cabrero I,Oliva E,Park KJ,Abu-Rustum NR,Soslow RA. Clinical Outcomes of HPV-associated and Unassociated Endocervical Adenocarcinomas Categorized by the International Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Criteria and Classification (IECC). Am J Surg Pathol. 2019; 43:466–474. DOI: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stolnicu S I,Hoang L, Patel P, Terinte C, Pesci A,Aviel-Ronen S, Kiyokawa T, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Oliva E, Park KJ, Abu-Rustum NR, Pike MC, Soslow RA. Stromal invasion pattern identifies patients at lowest risk of lymph node metastasis in HPV-associated endocervical adenocarcinomas, but is irrelevant in adenocarcinomas unassociated with HPV. Gynecol Oncol. 2018; 150:56–60. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.04.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]