Abstract

Background:

Brain donation in studies on aging remains a critical pathway to discovering and improving preventive measures and treatments for Alzheimer’s dementia and related disorders. Brain donation for research is almost exclusively obtained from non-Latinx Whites of higher socioeconomic status in the United States. Despite persistent efforts, it has been difficult to obtain consent for brain donation among diverse participants. Hence, our understanding of Alzheimer’s dementia and related disorders remains incomplete. The purpose of this methodological paper was to propose and outline a two-phase sequential mixed-methods research study design to identify barriers and facilitators of brain donation among diverse older adults.

Methods:

The first phase will consist of qualitative focus groups using a three (participant minority status: African American, Latinx, or White of lower income) by two (participant brain donation decision: consented or declined) design. The second phase will include statistical analyses of quantitative measures of existing data representing categories of variables that may be associated with decision making regarding brain donation.

Discussion:

Next steps must include conducting qualitative focus groups and subsequent data analyses, resulting in overarching themes. Afterward, qualitative themes will be operationalized using quantitative variables for statistical analyses. This proposed study design can provide the foundation for designing and implementing effective and culturally competent survey instruments, educational tools, and intervention strategies in an effort to facilitate brain donation among diverse older adults.

Keywords: Study Design, Brain Donation, Decision Making, Minority Health, Health Equity

Introduction

Brain tissue from persons enrolled in longitudinal studies on aging remains a critical pathway to uncovering mechanisms related to the development, treatment, and prevention of Alzheimer’s dementia and related disorders (Boise, Hinton, Rosen, & Ruhl, 2016; Carlos, Poloni, Medici, Chikhladze, Guaita, & Ceroni, 2019; Striley, Milani, Kwiatkowski, DeKosky, & Cottler, 2019). In the United States, available brain tissue obtained at death originates almost exclusively from non-Latinx Whites of higher socioeconomic status. Despite continuous efforts, difficulties exist in obtaining consent for brain donation from persons who belong to minority populations including African Americans, Latinxs, and Whites of lower socioeconomic status (Barnes, Shah, Aggarwal, Bennett, & Schneider, 2012; Bilbrey, Humber, Plowey, Garcia, Chennapragada, Desai, et al., 2018; Bonner, Darkwa, & Gorelick, 2000; Jefferson, Lambe, Cook, Pimontel, Palmisano, & Chaisson, 2011; Kaye, Dame, Lehman, & Sexton, 1999; Lambe, Cantwell, Islam, Horvath, & Jefferson, 2010). Additionally, this disparity exists even among older adults who consented to brain donation, with lower numbers of completed brain autopsies for older minorities compared to those who are non-Latinx Whites. Hence, current brain donation and resultant brain tissue do not represent the racial, ethnic, and economic diversity of older adults (Filshtein, Dugger, Jin, Olichney, Farias, & Carvajal-Carmona, 2019). As such, our understanding of Alzheimer’s dementia and related disorders remains severely limited in these underrepresented and understudied populations. As older minorities including African Americans and Latinxs face an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) compared to their non-Latinx White counterparts (Gaugler, James, Johnson, Marin, & Weuve, 2019), insufficient brain tissue among minority populations may exacerbate existing disparities in AD and aging.

The first step to obtaining brain tissue for research is voluntary consent. Previous literature has focused on reasons why older minorities, especially older African Americans, may or may not consent to brain donation for research (Boise et al., 2016; Bonner et al., 2000; Darnell, McGuire, & Danner, 2011; Jefferson et al., 2011; Kaye et al., 1999; Lambe et al., 2010; Schnieders, Danner, McGuire, Reynolds, & Abner; 2013). These studies have largely employed qualitative research designs and methods, such as focus groups and individual interviews, to understand factors associated with consenting to brain donation. Qualitative methodologies provide in-depth insight into participants’ attitudes, beliefs, and thoughts regarding a particular issue (Creswell & Creswell, 2017; Creswell & Poth, 2017). Researchers use qualitative methods when relatively little knowledge exists about a particular issue or when less is known about a particular issue within a specific group of people (Creswell & Creswell, 2017; Creswell & Poth, 2017). Hence, qualitative research designs can provide in-depth participant perspectives on complex and sensitive issues, including brain donation, especially among older minorities.

Overall, previous qualitative research has found altruism and perceptions of brain donation as beneficial to the person or future generations as facilitators (Darnell et al., 2011; Schnieders et al., 2013). Concerns about the invasiveness of the autopsy and potential parameters of religious beliefs regarding burial and entry into Heaven are perceived as barriers (Boise et al., 2016; Jefferson et al., 2011; Lambe et al., 2010). Much of the research can be organized into three categories of inquiry, each with its own set of limitations. See Table 1. For example, some research focuses exclusively on older African Americans, but runs the risk of generalizing barriers and facilitators to other diverse racial, ethnic, and economic groups. Other investigators may include multiple racial and ethnic groups, but data are aggregated across racial and ethnic groups, preventing the ability to identify unique barriers and potential facilitators across all minority groups and within minority groups. Finally, some researchers include both participants who consented to and declined brain donation in one focus group. Without a clear understanding of facilitators of brain donation as expressed by people who have agreed, we may not fully leverage qualitative data to inform recruitment strategies and education materials aimed toward people who have not consented to brain donation. Additionally, without qualitative research designs examining unique factors of brain donation decision making among people who have consented, researchers and others may lose opportunities to create and improve upon approaches to increase the number of successful brain autopsies among older minorities.

Table 1:

Selecta Qualitative Research on Brain Donation Decision Making among Older Minorities and Key Study Characteristics.

| Qualitative Methodology | Exclusive African American Sample | Aggregated Data Across Racial/Ethnic Groups | Agnostic to Brain Donation Decision Status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boise, Hinton, Rosen, & Ruhl, 2016 | Focus Group | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Bonner, Darkwa, & Gorelick, 2000 | Interview | ✓ | ||

| Darnell, McGuire, & Danner, 2011 | Interview (Recruitment) | ✓ | ||

| Lambe, Cantwell, Islam, Horvath, & Jefferson, 2010 | Focus Group | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Schnieders, Danner, McGuire, Reynolds, & Abner, 2013 | Interview (Educational) | ✓ |

We selected components of literature that we believe represent pathways to current knowledge regarding brain donation decision making among older minorities. This list is not intended to be exhaustive.

Qualitative research designs remain key for understanding barriers and facilitators of brain donation among older minorities. However, as with all research designs, qualitative methods possess limitations such as decreased importance placed on representative sample sizes. Instead, qualitative research methodologies prioritize “saturation” or the conclusion that further data collection is not needed, as it will not yield new information (Queirós, Faria, & Almeida, 2017; Saunders, Sim, Kingstone, Baker, Waterfield, Bartlam, et al., 2018; Tuckett, 2004). Qualitative research designs are also traditionally inductive, with a focus on in-depth examination of issues in particular populations and serve as a basis for generating hypotheses and theories. Conversely, quantitative methodologies typically test hypotheses and theories through deductive approaches. Thus, through the integration of quantitative research methodologies, we may offset qualitative design limitations. We may use quantitative measurements to operationalize concepts set forth by qualitative research designs in an effort to test and understand relationships between variables within a larger, more representative sample. Ultimately, quantitative research designs can allow for the triangulation and expansion of qualitative research findings (Bailey, 2018; Jick, 1979). Hence, both qualitative approaches and quantitative assessments may provide a fuller and more complete understanding of decision making for brain donation among diverse older adults.

Mixed-methods research designs pair qualitative and quantitative approaches into one study to address a singular purpose using both participant perspectives and numeric-based measurement instruments. Mixed-methods research designs may result in the development and testing of survey instruments, educational tools, and intervention strategies regarding a particular issue among specific groups of people. To our knowledge, no study has proposed or utilized a mixed-methods research design to examine barriers and facilitators of consenting to brain donation, including among older minorities. Thus, the purpose of this paper was to describe a proposed two-phase sequential mixed-methods research design (Creswell, 2013; Driscoll, Appiah-Yeboah, Salib, & Rupert, 2007) aimed toward identifying specific qualitative factors and quantitative correlates that serve as either barriers to or facilitators of brain donation among older minorities who are African American, Latinx, or White of lower income.

Proposed Design and Methods

This paper sets forth a proposed novel approach – a two-phase sequential mixed-methods research design – to address consenting to brain donation among diverse older adults. As this paper is a methodological one, this section outlines the goals and rationale of the proposed study design as well as considerations for subsequent execution of the proposed study design. The following aspects of prospective research by the authors and other researchers are set forth in this section, as well, including: (1) recommended study participant criteria; (2) proposed recruitment methods; and (3) suggested procedures for conducting qualitative focus groups with older minorities. The subsequent Discussion and Implications section outlines intended data analyses for both qualitative and quantitative data appropriate for the proposed study design.

Objectives and proposed study design

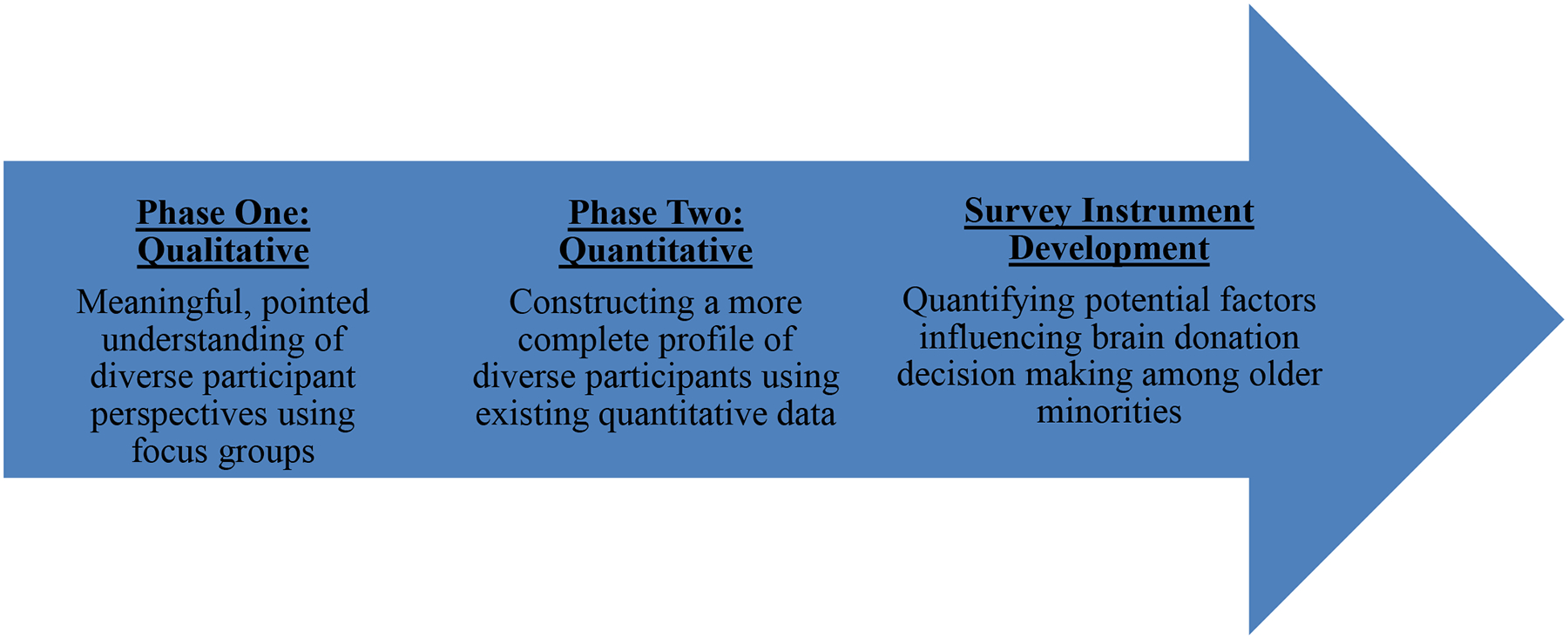

We outline a proposed two-phase sequential mixed-methods research study design aimed toward identifying and understanding barriers and facilitators to consenting to brain donation among older minorities. With this research design, data from the first phase (qualitative) inform the second phase (quantitative) - denoting a pipeline from qualitative data collection representing diverse participant perspectives to creating a more complete profile of older minorities who consent to or decline brain donation using quantitative data. The first objective of this study is to identify factors that either serve as barriers or facilitators to consenting to brain donation among diverse older minorities. Qualitative methods, specifically focus groups, will be used to address the first objective. Focus group themes (or findings) from the first phase will inform potential variables to explore using quantitative measures in the second phase. Hence, the second, but equally important, objective of this study is to identify possible correlates of consenting to or declining brain donation among diverse older adults using quantitative measurements and subsequent statistical analyses. Once both qualitative themes and quantitative correlates are identified, we propose merging the two phases to: (1) facilitate the development of more complete profiles of diverse older adults who agree to and decline brain donation; and (2) allow for the subsequent development of a culturally competent survey instrument that will assess brain donation decision making among diverse older adults. The survey instrument will allow for a fuller yet expeditious assessment of diverse older adults who may or may not be likely to consent to brain donation and potential reasons why. See Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Proposed Two-Phase Sequential Mixed-Methods Research Design: Data from Phase One Inform Phase Two to Create a Pipeline Resulting in Survey Instrument Development.

Criteria for proposed study participation

For both study phases, we recommend conducting focus groups with participants from (first qualitative phase) and analyzing data collected as part of (second quantitative phase) four ongoing longitudinal cohort studies of aging. All cohort studies are community-based with all participants tested individually within their residences in and around an urban metropolitan area. Cohort studies include brain donation as either a study requirement or an optional component of the study. Two cohort studies exclusively consisting of older African Americans and one cohort study solely pertaining to older Latinxs seek brain donation as an option for participants. One cohort study largely comprised of older Whites requires brain donation for study participation. For Whites of lower income who decline brain donation, we recommend recruiting from cohort study-affiliated testing sites. The proposed study design and all cohort studies have been approved by an Institutional Review Board at the Rush University Medical Center.

Eligibility criteria for the proposed study, both first and second phases, will include: (1) being 60 years of age or older; (2) being free of dementia; (3) self-identification as African American or Latinx; (4) self-identification as non-Latinx White with self-reported income at or below approximately 150% of the 2018 Federal Poverty Level (https://aspe.hhs.gov/2018-poverty-guidelines), or a yearly income equal to or less than $19,999; and (5) agreeing to or declining brain donation. As part of cohort study participation, each person undergoes an annual structured clinical evaluation including a review of medical history, neurological examination, and cognitive function testing, as previously described (Barnes, Lewis, Begeny, Yu, Bennett, & Wilson, 2012; Bennett, Buchman, Boyle, Barnes, Wilson, & Schneider, 2018). A clinician then classifies persons with respect to dementia using the criteria of the joint working group of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINDS/ADRDA) (McKhann, Drachman, Folstein, Katzman, Price, & Stadlan, 1984), which require a history of cognitive decline and evidence of impairment in at least two cognitive domains. All participants report their race (e.g. African American/Black) and ethnicity (i.e. Hispanic: yes or no) based on categories from the 1990 United States Census Bureau as well as their gender (i.e. male or female), date of birth, years of education, marital status (i.e. married, separated, divorced, or widowed), and income. Annual income is measured using the show-card method from the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (Huntley, Ostfeld, Taylor, Wallace, Blazer, Berkman, et al., 1993), in which participants are asked to select 1 of 10 levels of total annual family income.

Proposed phase one: qualitative focus groups

Qualitative focus group guides

In order to conduct the proposed focus groups in the future, two Focus Group Guides have been developed (Krueger & Casey, 2000) – one for participants who have agreed to brain donation and one for participants who have declined brain donation. Each Guide represents a set of content areas with corresponding questions. Guide content areas and related questions were developed by examining previous literature, performing clinic observations, and community-based exposure to and engagement with people who represent communities where proposed participant sampling will occur (e.g. community health fairs geared toward older adults, especially older minorities). Overall, Guides will provide structure for focus groups and serve as tools for the moderator to lead focus group discussions. As proposed focus groups will be semi-structured, Guides will provide content areas and questions for the moderator to facilitate discussion but Guides will not dictate the order of questions; rather, focus group participants will shape the flow of the discussion. In the proposed study, both Guides contain seven content areas: (1) knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease; (2) perceptions of research; (3) perceptions and knowledge of brain donation; (4) brain donation decision; (5) altruism and thinking of the future (family and future generations); (6) religious beliefs; and (7) closing questions. A sample question for participants who agreed to brain donation will include, “What did your family say about your decision to donate your brain?” Conversely, a sample question for participants who declined brain donation will include, “What information would you need to reconsider brain donation?”

Proposed focus group recruitment

Two methods will be used to recruit focus group participants. For the first method, study staff will identify eligible persons based on the above criteria who belong to one of the cohort studies. Once study staff identify eligible persons, they will provide telephone calls, letters, and/or in-person visits to introduce the proposed study. Simultaneously, study staff will use a second method consisting of recruiting from community-based sites where existing cohort study participants and affiliated persons frequent including churches, community centers, senior groups, health centers, libraries, and senior living facilities. At these community-based locations, study staff will post flyers and hold presentations regarding the purpose of the proposed study and subsequent focus group participation. After contact with interested persons to ascertain eligibility and to confirm interest via voluntary verbal consent, staff will begin scheduling times and locations for focus groups.

Proposed focus group procedures

Each participant will take part in one focus group. We propose a three (participant minority status: African American, Latinx, or White of lower income) by two (participant brain donation decision: consented or declined) design for focus groups. More specifically, six separate focus groups should be conducted, consisting of: (1) older African Americans who consented; (2) older African Americans who declined; (3) older Latinxs who consented; (4) older Latinxs who declined; (5) older Whites of lower income who consented; and (6) older Whites of lower income who declined. Based on a qualitative sampling algorithm (Krueger & Casey, 2014), it is proposed that each focus group consists of approximately 5–8 older adults with a total amount of 30–48 participants - approximately 15–24 participants who consented to brain donation and approximately 15–24 participants who declined brain donation.

Each focus group should include an explanation of the purpose of the focus group and what comprises participation, orally leading participants through Informed Consent and HIPAA documents, participant completion of a demographic survey, and the use of audio-recorders. All participants should provide written consent prior to activation of audio-recorders. Once each focus group is completed, all focus group data including audio-recordings should be uploaded to a secure server behind a firewall. Audio-recordings should be electronically transferred to a medical transcription agency. Transcription should include the de-identification of participants by replacing participant names with a random participant identification number such as “Interviewee 1” and deletion of any names and other protected health information. To ensure fidelity and consistency cross all focus groups, one person should serve as the moderator, accompanied by at least two trained study staff.

Proposed phase two: quantitative variables

As part of the cohort studies, an array of data are collected that represent variables postulated or previously shown to be associated with aging or chronic diseases of aging including AD (Aggarwal, Wilson, Beck, Rajan, Mendes De Leon, Evans, et al., 2014; Bennett, Schneider, Tang, Arnold, & Wilson, 2006; Boyle, Barnes, Buchman, & Bennett, 2009; Buchman, Boyle, Wilson, Fleischman, Leurgans, & Bennett, 2009; Hill, Mogle, Bhargava, Whitaker, Bhang, Capuano, et al., 2018; Lewis, Aiello, Leurgans, Kelly, & Barnes, 2010; Turner, James, Capuano, Aggarwal, & Barnes, 2017; Wilson, Barnes, Krueger, Hoganson, Bienias, & Bennett, 2005; Wilson, Barnes, Mendes de Leon, Aggarwal, Schneider, Bach, et al., 2002; Wilson, Krueger, Arnold, Schneider, Kelly, Barnes, et al., 2007; Wilson, Segawa, Boyle, & Bennett, 2012). Quantitative variables that operationalize qualitative themes – likely representing categories such as cognition, demographic characteristics, experiential, psychological, social, and spirituality - will be selected for standard statistical analyses.

Discussion and Implications

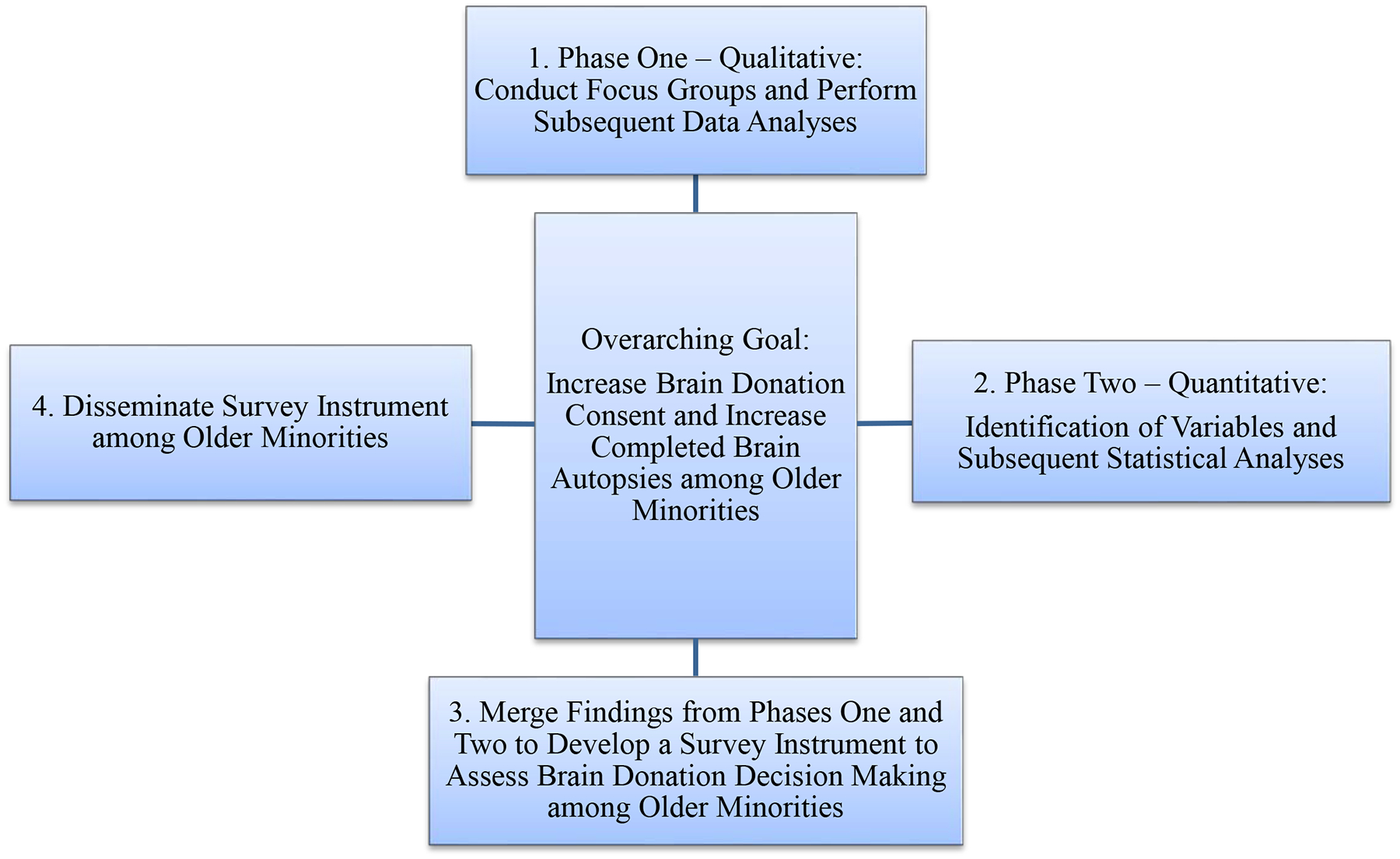

In this paper, we proposed a two-phase sequential mixed-methods research approach (Driscoll et al., 2007) to understand barriers and facilitators associated with decision making regarding brain donation among diverse older adults including African Americans, Latinxs, and Whites of lower income. In order to execute the proposed design, seminal next steps must include conducting qualitative focus groups until saturation is reached and subsequent qualitative data analyses. To analyze qualitative data, we propose an inductive Grounded Theory Approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998) with Open Coding (i.e. data-driven coding that does not begin with preconceptions) (Gibbs, 2018) followed by Constant Comparative Coding (i.e. contrasting the meaning of a code between groups of people or different environments to discover the dimensionality of a code) (Gibbs, 2018). These qualitative data analyses will allow researchers and others to better understand barriers and facilitators to brain donation, overall, as well as differences between minority groups. Qualitative data analyses will yield themes, subthemes, and codes related to barriers and facilitators of brain donation among diverse older adults.

Once qualitative data analyses are completed, quantitative variables of interest that operationalize themes, subthemes, and codes gleaned from the qualitative focus groups should be identified for standard statistical data analyses such as descriptive analyses, multiple regression analyses, and between-group comparisons using standard quantitative approaches. Quantitative analyses will allow the examination of potential differences between older minorities based on brain donation status and variables representing categories including demographic characteristics, cognition, experiential, psychological, social, and spirituality. Quantitative statistical analyses will also assess within-minority group differences on these same variables.

Lastly, directly stemming from both qualitative findings and quantitative results, it is possible to create a survey instrument addressing barriers and facilitators to brain donation among diverse older minorities. The survey instrument should consist of items that operationalize findings yielded from qualitative focus group data and address significant quantitative variables related to decision making regarding brain donation. The survey instrument will allow for a more expedited assessment of barriers and facilitators to brain donation among older minorities. See Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Potential Next Steps for the Proposed Two-Phase Sequential Mixed-Methods Research Design.

This paper provides insight into the purpose and elements of a proposed two-phase sequential mixed-methods research design. More specifically, the proposed study design aims to denote a pipeline from qualitative data collection to creating a more complete profile of older minorities who consent to or decline brain donation using quantitative data (Cameron, 2009; Driscoll et al., 2007; Natasi, Hitchcock, Sarkar, Burkholder, Varjas, & Jayasena, 2007). The proposed pipeline extends to developing a survey instrument where the goal is, in part, to gain an expeditious yet thorough understanding of potential factors that impact decision making of diverse older adults that consent to or decline brain donation (Fetters, Curry, & Creswell, 2013; Natasi et al., 2007). By bringing together qualitative and quantitative methods and findings into one study, researchers and others are better poised to develop and implement survey instruments, educational tools, and intervention strategies originally designed to be culturally competent and person-centered instead of tailored or modified versions of existing materials and protocols (Fetters et al., 2013; Natasi et al., 2007). Hence, this proposed mixed-methods research approach can provide a foundation for culturally competent and effective recruitment and retention efforts to increase older minority representation in available brain tissue, which can facilitate health equity in human neuroscience research.

Acknowledgement

We thank the participants and staff of The Health Equity through Aging Research and Discussion (HEARD) Study and all cohort studies at the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [diversity supplement to grant number P30AG10161-S] to CMG, [grant numbers P30AG10161 and R01AG17917] to DAB, and [grant number RF1AG022018] to LLB. Funders did not play a role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Statement of Ethics

All procedures have been approved by the Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. All participants will provide written informed consent for study participation.

References

- 1.Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Rajan KB, De Leon CFM, Evans DA, & Everson-Rose SA (2014). Perceived stress and change in cognitive function among adults aged 65 and older. Psychosomatic medicine, 76(1), 80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey CA (2018). A Guide to Qualitative Field Research. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes LL, Lewis TT, Begeny CT, Yu L, Bennett DA, & Wilson RS (2012). Perceived discrimination and cognition in older African Americans. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 18(5), 856–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes LL, Shah RC, Aggarwal NT, Bennett DA, & Schneider JA (2012). The Minority Aging Research Study: ongoing efforts to obtain brain donation in African Americans without dementia. Current Alzheimer Research, 9(6), 734–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, & Schneider JA (2018). Religious orders study and rush memory and aging project. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 64(1), S161–S189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Tang Y, Arnold SE, & Wilson RS (2006). The effect of social networks on the relation between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and level of cognitive function in old people: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Neurology, 5(5), 406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilbrey AC, Humber MB, Plowey ED, Garcia I, Chennapragada L, Desai K, Rosen A, Askari N, & Gallagher-Thompson D (2018). The impact of Latino values and cultural beliefs on brain donation: results of a pilot study to develop culturally appropriate materials and methods to increase rates of brain donation in this under-studied patient group. Clinical Gerontologist, 41(3), 237–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boise L, Hinton L, Rosen HJ, & Ruhl M (2016). Will my soul go to heaven if they take my brain? beliefs and worries about brain donation among four ethnic groups. The Gerontologist, 57(4), 719–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonner GJ, Darkwa OK, & Gorelick PB (2000). Autopsy recruitment program for African Americans. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 14(4), 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Buchman AS, & Bennett DA (2009). Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(5), 574–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Fleischman DA, Leurgans S, & Bennett DA (2009). Association between late-life social activity and motor decline in older adults. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(12), 1139–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron R (2009). A sequential mixed model research design: design, analytical and display issues. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 3(2), 140–152. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlos AF, Poloni TE, Medici V, Chikhladze M, Guaita A, & Ceroni M (2019). From brain collections to modern brain banks: a historical perspective. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 5, 52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creswell JW (2013). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Creswell JW, & Creswell JD (2017). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creswell JW, & Poth CN (2017). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darnell KR, McGuire C, & Danner DD (2011). African American participation in Alzheimer’s disease research that includes brain donation. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 26(6), 469–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Driscoll DL, Appiah-Yeboah A, Salib P, & Rupert DJ (2007). Merging qualitative and quantitative data in mixed methods research: how to and why not. Ecological and Environmental Anthropology (University of Georgia), 18 http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmeea/18 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fetters MD, Curry LA, & Creswell JW (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6pt2), 2134–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filshtein TJ, Dugger BN, Jin LW, Olichney JM, Farias ST, Carvajal-Carmona L, Lott P, Mungas D, Reed B Beckett L, & DeCarli C (2019). Neuropathological diagnoses of demented Hispanic, Black, and Non-Hispanic White decedents seen at an Alzheimer’s disease center. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 68(1)145–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaugler J, James B, Johnson T, Marin A, & Weuve J (2019). 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers & Dementia, 15(3), 321–387. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibbs GR (2018). Analyzing Qualitative Sata (Vol. 6). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glaser BG, & Strauss A (1967). The discovery of Grounded Theory. Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill NL, Mogle J, Bhargava S, Whitaker E, Bhang I, Capuano AW, Arvanitakis Z, Bennett DA, & Barnes LL (2018). Differences in the associations between memory complaints and depressive symptoms among Black and White older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 10.1093/geronb/gby091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. https://aspe.hhs.gov/2018-poverty-guidelines.

- 26. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1990/cp-1/cp-1-1.pdf.

- 27.Huntley J, Ostfeld AM, Taylor JO, Wallace RB, Blazer D, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Kohout J, Lemke JH, Scherr PA, & Korper SP (1993). Established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly: study design and methodology. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 5(1), 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jefferson AL, Lambe S, Cook E, Pimontel M, Palmisano J, & Chaisson C (2011). Factors associated with African-American and White elders’ participation in a brain donation program. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 25(1), 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jick TD (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 602–611. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaye JA, Dame A, Lehman S, & Sexton G (1999). Factors associated with brain donation among optimally healthy elderly people. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 54(11), M560–M564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krueger RA, & Casey MA (2000). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krueger RA & Casey MA (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 5th edition Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambe S, Cantwell N, Islam F, Horvath K, & Jefferson AL (2010). Perceptions, knowledge, incentives, and barriers of brain donation among African American elders enrolled in an Alzheimer’s research program. The Gerontologist, 51(1), 28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis TT, Aiello AE, Leurgans S, Kelly J, & Barnes LL (2010). Self-reported experiences of everyday discrimination are associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels in older African-American adults. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 24(3), 438–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, & Stadlan EM (1984). Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease Report of the NINCDS‐ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology, 34(7), 939–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nastasi BK, Hitchcock J, Sarkar S, Burkholder G, Varjas K, & Jayasena A (2007). Mixed methods in intervention research: theory to adaptation. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Queirós A, Faria D, & Almeida F (2017). Strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods. European Journal of Education Studies, 3(9), 369–387. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, Burroughs B, & Jinks C (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schnieders T, Danner DD, McGuire C, Reynolds F, & Abner E (2013). Incentives and barriers to research participation and brain donation among African Americans. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 28(5), 485–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strauss A, & Corbin J (1998). Basics of qualitative research: procedures and techniques for developing Grounded Theory. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Striley CW, Milani SA, Kwiatkowski E, DeKosky ST, & Cottler LB (2019). Community perceptions related to brain donation: evidence for intervention. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 15(2), 267–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tuckett AG (2004). Qualitative research sampling: the very real complexities. Nurse Researcher, 12(1), 47–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner AD, James BD, Capuano AW, Aggarwal NT, & Barnes LL (2017). Perceived stress and cognitive decline in different cognitive domains in a cohort of older African Americans. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(1), 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Krueger KR, Hoganson G, Bienias JL, & Bennett DA (2005). Early and late life cognitive activity and cognitive systems in old age. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 11(4), 400–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Aggarwal NT, Schneider JS, Bach J, Pilat J, Beckett LA, Arnold SE, Evans DA, & Bennett DA (2002). Depressive symptoms, cognitive decline, and risk of AD in older persons. Neurology, 59(3), 364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, Kelly JF, Barnes LL, Tang Y, & Bennett DA (2007). Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(2), 234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson RS, Segawa E, Boyle PA, & Bennett DA (2012). Influence of late-life cognitive activity on cognitive health. Neurology, 78(15), 1123–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.1990 United States Census Bureau Report, (https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1990/cp-1/cp-1-1.pdf) accessed on March 18, 2020.