Abstract

Background

At present, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, is spreading all over the world, with disastrous consequences for people of all countries. The traditional Chinese medicine prescription Dayuanyin (DYY), a classic prescription for the treatment of plague, has shown significant effects in the treatment of COVID-19. However, its specific mechanism of action has not yet been clarified. This study aims to explore the mechanism of action of DYY in the treatment of COVID-19 with the hope of providing a theoretical basis for its clinical application.

Methods

First, the TCMSP database was searched to screen the active ingredients and corresponding target genes of the DYY prescription and to further identify the core compounds in the active ingredient. Simultaneously, the Genecards database was searched to identify targets related to COVID-19. Then, the STRING database was applied to analyse protein–protein interaction, and Cytoscape software was used to draw a network diagram. The R language and DAVID database were used to analyse GO biological processes and KEGG pathway enrichment. Second, AutoDock Vina and other software were used for molecular docking of core targets and core compounds. Finally, before and after application of DYY, the core target gene IL6 of COVID-19 patients was detected by ELISA to validate the clinical effects.

Results

First, 174 compounds, 7053 target genes of DYY and 251 genes related to COVID-19 were selected, among which there were 45 target genes of DYY associated with treatment of COVID-19. This study demonstrated that the use of DYY in the treatment of COVID-19 involved a variety of biological processes, and DYY acted on key targets such as IL6, ILIB, and CCL2 through signaling pathways such as the IL-17 signaling pathway, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, and cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction. DYY might play a vital role in treating COVID-19 by suppressing the inflammatory storm and regulating immune function. Second, the molecular docking results showed that there was a certain affinity between the core compounds (kaempferol, quercetin, 7-Methoxy-2-methyl isoflavone, naringenin, formononetin) and core target genes (IL6, IL1B, CCL2). Finally, clinical studies showed that the level of IL6 was elevated in COVID-19 patients, and DYY can reduce its levels.

Conclusions

DYY may treat COVID-19 through multiple targets, multiple channels, and multiple pathways and is worthy of clinical application and promotion.

Keywords: Dayuanyin, Coronavirus disease 2019, Network pharmacology, Molecular docking, Mechanism research

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first discovered in Wuhan, China, on December 12, 2019, but to date, no definitive conclusion has been drawn about its origin. According to the classification of syndromes in traditional Chinese medicine, COVID-19 is classified as an “epidemic disease” (damp-warm disease), and it is a highly contagious disease. In the early stages of damp-warm diseases, “damp-warm disease with syndrome of pathogen blocking pleuro-diaphragmatic interspace” is very common and is a specific stage and phenomenon in the pathological process of the disease. This symptom first appeared in the Theory of Epidemic Febrile Disease by Wu Youke during the Ming Dynasty, and he created Dayuanyin (DYY), described in the book. After 2019-nCoV invades the human body, it disturbs and damages the human immune system, further causing different degrees of damage to various organs throughout the body [1, 2]. DYY, a traditional Chinese medicine prescription, has played an important role in the prevention and treatment of epidemic diseases in documented history and literature. It has been used to treat influenza [3], atypical pneumonia [4], AIDS [5] and other diseases and has proven to be very effective in clinical applications. At the same time, through clinical observation of COVID-19 patients in the early stage of DYY treatment, it was found that this prescription can improve the clinical symptoms and signs of patients, improve the prognosis of patients, and shorten the course of disease [6, 7], making it worthy of clinical application and promotion. However, its mechanism of action in COVID-19 patients has not yet been clarified.

Network pharmacology, originally proposed by Andrew L Hopkins, includes systems biology, pharmacology, mathematics, computer network analysis, etc. As a useful tool for systematically evaluating and demonstrating the rationality of drugs, it has now been widely accepted [8, 9]. The application of network pharmacology in traditional Chinese medicine provides us with new possibilities for screening active ingredients of drugs and targets for disease treatment, which is helpful for explaining the mechanism of action of drugs for disease treatment at a system level [10]. Molecular docking is a theoretical simulation method that mainly studies intermolecular interactions and predicts their binding mode and affinity [11]. Not only can it be used for drug development, but it can also provide keen insights into protein function prediction and other important issues [12].

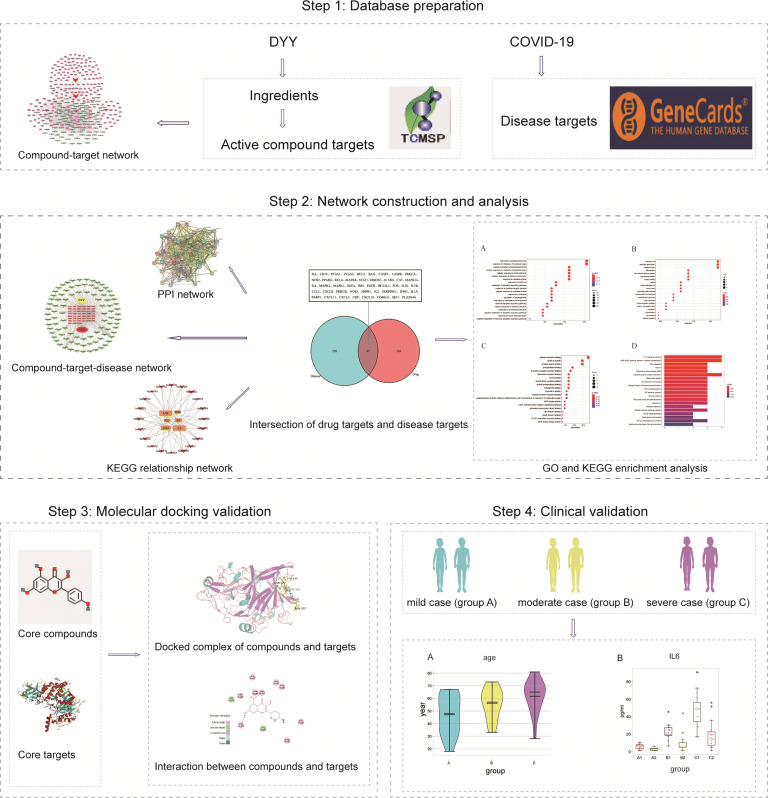

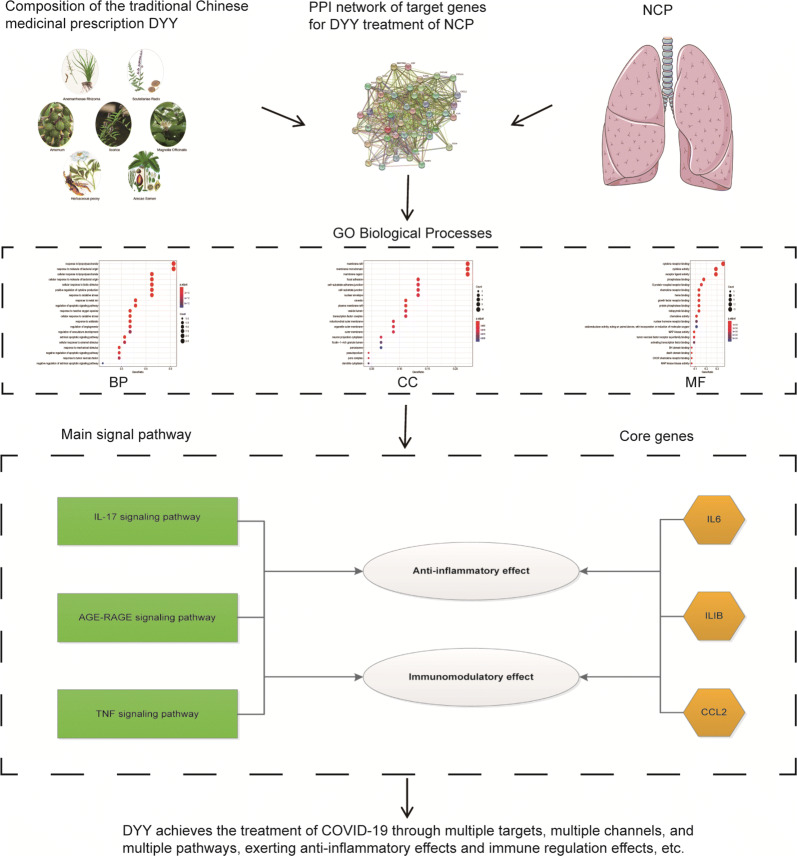

This study aimed to use network pharmacology and molecular docking to preliminarily explore the mechanism of action of this prescription in the treatment of COVID-19 patients, with the goal of widely using this prescription for COVID-19 patients with early damp-warm syndromes to improve the patients’ condition and to prevent the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak. A technological road-map of the experimental procedures of our study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Technological road-map

Methods

Acquisition of the chemical composition and target information of DYY

The Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform (TCMSP) records 499 common traditional Chinese medicines (Chinese Pharmacopoeia 2010 edition) and elaborates their ingredients, the corresponding target information and common disease information related to traditional Chinese medicines [13]. The database provides pharmacokinetic information for each compound, such as drug-like (DL), oral bioavailability (OB), and blood-brain barrier (BBB). In this study, the TCMSP database (http://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php) was used to search for and determine the active ingredients in the composition of the DYY decoction. At the same time, target genes were predicted for these active ingredients. OB and DL property are important reference standards for evaluating whether compounds can be used as drugs. In this study, OB ≥ 30% and DL ≥ 0.18 were used as screening thresholds [14]. According to the selected active ingredients of DYY, the target genes corresponding to the above active ingredients derived from DrugBank were further screened using Perl language in combination with the TCMSP database.

Gene name standardization

Perl language was used in combination with the UniProtKB search function in the UniProt database (http://www.uniprot.org/, update in 2018-04-10), the protein name was entered, the species was limited to humans, and the retrieved protein name was corrected to the official name of the protein.

Construction of network diagrams of compounds and corresponding targets

The compounds and predicted targets in the DYY formula obtained through the TCMSP database were imported into Cytoscape 3.6.1 software, and a compound-target network diagram was drawn to obtain the top five core compounds.

Acquisition of disease targets

The keyword “novel coronavirus pneumonia” was entered into the Genecards (https://www.genecards.org/, version 4.12) database to obtain target genes related to the COVID-19 disease.

Intersection of disease genes and drug genes

The target genes predicted from the active ingredients in DYY were intersected and mapped with the target genes predicted for the COVID-19 disease to obtain the target genes of DYY for the treatment of COVID-19. The Venn Diagram package in R was used to draw a Venn diagram.

Protein–protein interaction analysis and core target screening

The target genes for DYY treatment of COVID-19 were entered into the STRING database for protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis, “Homo sapiens” was selected, the minimum required interaction score was set to > 0.9, the protein interaction network map was downloaded, and R3.5.0 was used to screen core genes.

Construction of network visualization

The active ingredients of DYY, the targets corresponding to the active ingredients, and the targets predicted for the COVID-19 disease were imported into Cytoscape 3.6.1 software, and a drug-target-disease network diagram was constructed for network visualization.

GO analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

The DAVID database (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) can functionally annotate many genes and help us understand the biological process and meaning behind genes. The target genes selected above were combined with R language and DAVID database for Gene Ontology (GO) biological process enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment.

Construction of KEGG relationship network

The pathway ID numbers and the genes involved in the KEGG-enriched pathways were imported into Cytoscape software, the number of adjacent nodes in the network was calculated, and the size of the nodes in the network was determined according to the number of adjacent nodes to construct a KEGG relationship network.

Molecular docking verification of core compounds and core target genes

Firstly, the top five core compounds were selected, and the two-dimensional structure diagrams of the compounds were downloaded from the PubChem database, imported into Chem3D software to draw the three-dimensional structure diagrams of the core compounds and optimize the energy, and saved in mol2 format. Then, the files were imported into AutoDockTools-1.5.6 software to add charge and display rotatable keys and then saved in pdbqt format. Secondly, the protein crystal structures corresponding to the core target genes were downloaded from the PDB database, imported into Pymol software to remove water molecules and heteromolecules, imported into AutoDockTools-1.5.6 software to add hydrogen atoms and charge operations, saved to pdbqt format, and imported into Discovery Studio 3.5 Client software to search for active pockets. Finally, the above core compounds were used as ligands, and the proteins corresponding to the core target genes were used as receptors for molecular docking. The results were analysed and interpreted using PyMOL software and Discovery Studio 3.5 Client.

Clinical validation of the core target IL6

In this study, a total of 45 patients who were hospitalized in Third People’s Hospital of Hubei Province and Lei Shen Shan Hospital during the period from January 25, 2019 to March 8, 2020 were selected. The TCM syndrome of the selected patients was “plague (syndrome of pathogen hidden in interpleuro-diaphramatic space)”, and DYY was used for treatment. ELISA was used to detect changes in IL6 levels at the time of before and after treatment for 1 week. All statistical analyses were performed by GraphPad Prism version 7.00 software. T test was used for comparisons before and after treatment in each group. Our data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Mechanism of action of DYY in the treatment of COVID-19

Adobe Illustrator CC software was used to draw the chart for the specific mechanism of DYY treatment of COVID-19.

Results

Acquisition of the active ingredient and target information of DYY

The composition of DYY is magnolia officinalis(MO), amomum(AM), arecae semen(AS), herbaceous peony(HP), scutellariae radix(SR), anemarrhenae rhizoma(AR) and licorice(LR), as shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S1. A total of 839 DYY active ingredients were obtained from TCMSP database. Among them, the number of active ingredients from magnolia officinalis, amomum, arecae semen, herbaceous peony, scutellariae radix, anemarrhenae rhizoma and licorice was 52, 139, 59, 85, 143, 81, 280, respectively. After screening by the ADME standard (OB ≥ 30%, DL ≥ 0.18), 174 compounds were obtained, among which the number of compound from magnolia officinalis, amomum, arecae semen, herbaceous peony, scutellariae radix, anemarrhenae rhizoma and licorice was 8, 2, 8, 13, 3, 15, 92, respectively. Among them, MOL000073 (ent-Epicatechin) was a common compound of amomum, scutellariae radix, and licorice; MOL004961 (quercetin) was a common compound of licorice and arecae semen; MOL000211 (mairin) was a common compound of herbaceous peony and licorice; MOL000358 (beta-sitosterol) was a common compound of scutellariae radix and herbaceous peony; MOL000359 (sitosterol) was a common compound of licorice, scutellariae radix and herbaceous peony; and MOL000449 (stigmasterol) was a common compound of anemarrhenae rhizoma and scutellariae radix.

According to the results obtained by screening the active ingredients against the TCMSP database, there were a total of 7053 targets in the DrugBank. Among them, the number of targets of magnolia officinalis, amomum, arecae semen, herbaceous peony, scutellariae radix, anemarrhenae rhizoma and licorice was 379,1162,406, 990, 1203, 407 and 2506, respectively. After screening by the ADME standard (OB ≥ 30%, DL ≥ 0.18), 2766 targets related to the bioactive components were obtained, among which the number of targets from magnolia officinalis, amomum, arecae semen, herbaceous peony, scutellariae radix, anemarrhenae rhizoma and licorice was 32, 179, 41, 122, 436, 188, 1768, respectively. The distribution of candidate compounds and targets in each herb is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Active ingredients of compounds

| MOL ID | Component name | OB% | DL | Number of targets | Herb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOL010482 | WLN: 6OVR BVO6 | 43.74 | 0.24 | 9 | AS |

| MOL010485 | EPA | 45.66 | 0.21 | 2 | AS |

| MOL010489 | Resivit | 30.84 | 0.27 | 4 | AS |

| MOL001749 | ZINC03860434 | 43.59 | 0.35 | 4 | AS |

| MOL002032 | DNOP | 40.59 | 0.4 | 5 | AS |

| MOL002372 | (6Z,10E,14E,18E)-2,6,10,15,19,23-hexamethyltetracosa-2,6,10,14,18,22-hexaene | 33.55 | 0.42 | 0 | AS |

| MOL000004 | Procyanidin B1 | 67.87 | 0.66 | 11 | AS |

| MOL000073 | ent-Epicatechin | 48.96 | 0.24 | 6 | AS |

| MOL000073 | ent-Epicatechin | 48.96 | 0.24 | 6 | AM |

| MOL000074 | (4E,6E)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)hepta-4,6-dien-3-one | 67.92 | 0.24 | 7 | AM |

| MOL000085 | Beta-daucosterol_qt | 36.91 | 0.75 | 1 | AM |

| MOL000088 | Beta-sitosterol 3-O-glucoside_qt | 36.91 | 0.75 | 0 | AM |

| MOL000092 | Daucosterin_qt | 36.91 | 0.76 | 0 | AM |

| MOL000094 | Daucosterol_qt | 36.91 | 0.76 | 0 | AM |

| MOL000096 | (−)-Catechin | 49.68 | 0.24 | 11 | AM |

| MOL000098 | quercetin | 46.43 | 0.28 | 154 | AM |

| MOL005970 | Eucalyptol | 60.62 | 0.32 | 25 | MO |

| MOL005980 | Neohesperidin | 57.44 | 0.27 | 7 | MO |

| MOL001910 | 11alpha,12alpha-epoxy-3beta-23-dihydroxy-30-norolean-20-en-28,12beta-olide | 64.77 | 0.38 | 0 | HP |

| MOL001918 | Paeoniflorgenone | 87.59 | 0.37 | 0 | HP |

| MOL001919 | (3S,5R,8R,9R,10S,14S)-3,17-dihydroxy-4,4,8,10,14-pentamethyl-2,3,5,6,7,9-hexahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-15,16-dione | 43.56 | 0.53 | 2 | HP |

| MOL001921 | Lactiflorin | 49.12 | 0.8 | 0 | HP |

| MOL001924 | Paeoniflorin | 53.87 | 0.79 | 4 | HP |

| MOL001925 | Paeoniflorin_qt | 68.18 | 0.4 | 0 | HP |

| MOL001928 | Albiflorin_qt | 66.64 | 0.33 | 0 | HP |

| MOL001930 | Benzoyl paeoniflorin | 31.27 | 0.75 | 0 | HP |

| MOL000211 | Mairin | 55.38 | 0.78 | 1 | HP |

| MOL000358 | Beta-sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | 38 | HP |

| MOL000359 | Sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | 3 | HP |

| MOL000422 | Kaempferol | 41.88 | 0.24 | 63 | HP |

| MOL000492 | (+)-Catechin | 54.83 | 0.24 | 11 | HP |

| MOL001689 | Acacetin | 34.97 | 0.24 | 0 | SR |

| MOL000173 | Wogonin | 30.68 | 0.23 | 0 | SR |

| MOL000228 | (2R)-7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-2-phenylchroman-4-one | 55.23 | 0.2 | 22 | SR |

| MOL002714 | Baicalein | 33.52 | 0.21 | 37 | SR |

| MOL002908 | 5,8,2′-Trihydroxy-7-methoxyflavone | 37.01 | 0.27 | 0 | SR |

| MOL002909 | 5,7,2,5-tetrahydroxy-8,6-dimethoxyflavone | 33.82 | 0.45 | 13 | SR |

| MOL002910 | Carthamidin | 41.15 | 0.24 | 4 | SR |

| MOL002911 | 2,6,2′,4′-tetrahydroxy-6′-methoxychaleone | 69.04 | 0.22 | 0 | SR |

| MOL002913 | Dihydrobaicalin_qt | 40.04 | 0.21 | 4 | SR |

| MOL002914 | Eriodyctiol (flavanone) | 41.35 | 0.24 | 8 | SR |

| MOL002915 | Salvigenin | 49.07 | 0.33 | 18 | SR |

| MOL002917 | 5,2′,6′-Trihydroxy-7,8-dimethoxyflavone | 45.05 | 0.33 | 17 | SR |

| MOL002925 | 5,7,2′,6′-Tetrahydroxyflavone | 37.01 | 0.24 | 6 | SR |

| MOL002926 | Dihydrooroxylin A | 38.72 | 0.23 | 0 | SR |

| MOL002927 | Skullcapflavone II | 69.51 | 0.44 | 21 | SR |

| MOL002928 | Oroxylin a | 41.37 | 0.23 | 26 | SR |

| MOL002932 | Panicolin | 76.26 | 0.29 | 14 | SR |

| MOL002933 | 5,7,4′-Trihydroxy-8-methoxyflavone | 36.56 | 0.27 | 18 | SR |

| MOL002934 | NEOBAICALEIN | 104.34 | 0.44 | 22 | SR |

| MOL002937 | DIHYDROOROXYLIN | 66.06 | 0.23 | 11 | SR |

| MOL000358 | beta-sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | 38 | SR |

| MOL000359 | Sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | 3 | SR |

| MOL000525 | Norwogonin | 39.4 | 0.21 | 12 | SR |

| MOL000552 | 5,2′-Dihydroxy-6,7,8-trimethoxyflavone | 31.71 | 0.35 | 21 | SR |

| MOL000073 | ent-Epicatechin | 48.96 | 0.24 | 6 | SR |

| MOL000449 | Stigmasterol | 43.83 | 0.76 | 31 | SR |

| MOL001458 | Coptisine | 30.67 | 0.86 | 9 | SR |

| MOL001490 | bis[(2S)-2-ethylhexyl] benzene-1,2-dicarboxylate | 43.59 | 0.35 | 1 | SR |

| MOL001506 | Supraene | 33.55 | 0.42 | 0 | SR |

| MOL002879 | Diop | 43.59 | 0.39 | 3 | SR |

| MOL002897 | Epiberberine | 43.09 | 0.78 | 11 | SR |

| MOL008206 | Moslosooflavone | 44.09 | 0.25 | 25 | SR |

| MOL010415 | 11,13-Eicosadienoic acid, methyl ester | 39.28 | 0.23 | 1 | SR |

| MOL012245 | 5,7,4′-trihydroxy-6-methoxyflavanone | 36.63 | 0.27 | 6 | SR |

| MOL012246 | 5,7,4′-trihydroxy-8-methoxyflavanone | 74.24 | 0.26 | 6 | SR |

| MOL012266 | Rivularin | 37.94 | 0.37 | 22 | SR |

| MOL001677 | Asperglaucide | 58.02 | 0.52 | 5 | AR |

| MOL003773 | Mangiferolic acid | 36.16 | 0.84 | 0 | AR |

| MOL000422 | Kaempferol | 41.88 | 0.24 | 63 | AR |

| MOL004373 | Anhydroicaritin | 45.41 | 0.44 | 37 | AR |

| MOL004489 | Anemarsaponin F_qt | 60.06 | 0.79 | 1 | AR |

| MOL004492 | Chrysanthemaxanthin | 38.72 | 0.58 | 0 | AR |

| MOL004497 | Hippeastrine | 51.65 | 0.62 | 11 | AR |

| MOL004514 | Timosaponin B III_qt | 35.26 | 0.87 | 2 | AR |

| MOL000449 | Stigmasterol | 43.83 | 0.76 | 31 | AR |

| MOL004528 | Icariin I | 41.58 | 0.61 | 1 | AR |

| MOL004540 | Anemarsaponin C_qt | 35.5 | 0.87 | 3 | AR |

| MOL004542 | Anemarsaponin E_qt | 30.67 | 0.86 | 0 | AR |

| MOL000483 | (Z)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl)-N-[2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl]acrylamide | 118.35 | 0.26 | 8 | AR |

| MOL000546 | diosgenin | 80.88 | 0.81 | 16 | AR |

| MOL000631 | Coumaroyltyramine | 112.9 | 0.2 | 10 | AR |

| MOL001484 | Inermine | 75.18 | 0.54 | 17 | LR |

| MOL001792 | DFV | 32.76 | 0.18 | 12 | LR |

| MOL000211 | Mairin | 55.38 | 0.78 | 1 | LR |

| MOL002311 | Glycyrol | 90.78 | 0.67 | 11 | LR |

| MOL000239 | Jaranol | 50.83 | 0.29 | 13 | LR |

| MOL002565 | Medicarpin | 49.22 | 0.34 | 34 | LR |

| MOL000354 | Isorhamnetin | 49.6 | 0.31 | 37 | LR |

| MOL000359 | Sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | 3 | LR |

| MOL003656 | Lupiwighteone | 51.64 | 0.37 | 21 | LR |

| MOL003896 | 7-Methoxy-2-methyl isoflavone | 42.56 | 0.2 | 43 | LR |

| MOL000392 | Formononetin | 69.67 | 0.21 | 39 | LR |

| MOL000417 | Calycosin | 47.75 | 0.24 | 22 | LR |

| MOL000422 | Kaempferol | 41.88 | 0.24 | 63 | LR |

| MOL004328 | Naringenin | 59.29 | 0.21 | 37 | LR |

| MOL004805 | (2S)-2-[4-hydroxy-3-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)phenyl]-8,8-dimethyl-2,3-dihydropyrano[2,3-f]chromen-4-one | 31.79 | 0.72 | 12 | LR |

| MOL004806 | Euchrenone | 30.29 | 0.57 | 10 | LR |

| MOL004808 | Glyasperin B | 65.22 | 0.44 | 21 | LR |

| MOL004810 | Glyasperin F | 75.84 | 0.54 | 18 | LR |

| MOL004811 | Glyasperin C | 45.56 | 0.4 | 24 | LR |

| MOL004814 | Isotrifoliol | 31.94 | 0.42 | 14 | LR |

| MOL004815 | (E)-1-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3-(2,2-dimethylchromen-6-yl)prop-2-en-1-one | 39.62 | 0.35 | 20 | LR |

| MOL004820 | Kanzonols W | 50.48 | 0.52 | 21 | LR |

| MOL004824 | (2S)-6-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-2-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-4-methoxy-2,3-dihydrofuro[3,2-g]chromen-7-one | 60.25 | 0.63 | 21 | LR |

| MOL004827 | Semilicoisoflavone B | 48.78 | 0.55 | 17 | LR |

| MOL004828 | Glepidotin A | 44.72 | 0.35 | 25 | LR |

| MOL004829 | Glepidotin B | 64.46 | 0.34 | 15 | LR |

| MOL004833 | Phaseolinisoflavan | 32.01 | 0.45 | 22 | LR |

| MOL004835 | Glypallichalcone | 61.6 | 0.19 | 27 | LR |

| MOL004838 | 8-(6-hydroxy-2-benzofuranyl)-2,2-dimethyl-5-chromenol | 58.44 | 0.38 | 6 | LR |

| MOL004841 | Licochalcone B | 76.76 | 0.19 | 19 | LR |

| MOL004848 | Licochalcone G | 49.25 | 0.32 | 17 | LR |

| MOL004849 | 3-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-8-(1,1-dimethylprop-2-enyl)-7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-coumarin | 59.62 | 0.43 | 23 | LR |

| MOL004855 | Licoricone | 63.58 | 0.47 | 15 | LR |

| MOL004856 | Gancaonin A | 51.08 | 0.4 | 20 | LR |

| MOL004857 | Gancaonin B | 48.79 | 0.45 | 22 | LR |

| MOL004860 | licorice glycoside E | 32.89 | 0.27 | 0 | LR |

| MOL004863 | 3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-8-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)chromone | 66.37 | 0.41 | 18 | LR |

| MOL004864 | 5,7-dihydroxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-8-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)chromone | 30.49 | 0.41 | 20 | LR |

| MOL004866 | 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-6-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)chromone | 44.15 | 0.41 | 16 | LR |

| MOL004879 | Glycyrin | 52.61 | 0.47 | 17 | LR |

| MOL004882 | Licocoumarone | 33.21 | 0.36 | 7 | LR |

| MOL004883 | Licoisoflavone | 41.61 | 0.42 | 19 | LR |

| MOL004884 | Licoisoflavone B | 38.93 | 0.55 | 17 | LR |

| MOL004885 | Licoisoflavanone | 52.47 | 0.54 | 20 | LR |

| MOL004891 | Shinpterocarpin | 80.3 | 0.73 | 30 | LR |

| MOL004898 | (E)-3-[3,4-dihydroxy-5-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)phenyl]-1-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one | 46.27 | 0.31 | 12 | LR |

| MOL004903 | Liquiritin | 65.69 | 0.74 | 6 | LR |

| MOL004904 | Licopyranocoumarin | 80.36 | 0.65 | 16 | LR |

| MOL004905 | 3,22-Dihydroxy-11-oxo-delta(12)-oleanene-27-alpha-methoxycarbonyl-29-oic acid | 34.32 | 0.55 | 0 | LR |

| MOL004907 | Glyzaglabrin | 61.07 | 0.35 | 18 | LR |

| MOL004908 | Glabridin | 53.25 | 0.47 | 25 | LR |

| MOL004910 | Glabranin | 52.9 | 0.31 | 11 | LR |

| MOL004911 | Glabrene | 46.27 | 0.44 | 19 | LR |

| MOL004912 | Glabrone | 52.51 | 0.5 | 21 | LR |

| MOL004913 | 1,3-dihydroxy-9-methoxy-6-benzofurano[3,2-c]chromenone | 48.14 | 0.43 | 10 | LR |

| MOL004914 | 1,3-dihydroxy-8,9-dimethoxy-6-benzofurano[3,2-c]chromenone | 62.9 | 0.53 | 9 | LR |

| MOL004915 | Eurycarpin A | 43.28 | 0.37 | 19 | LR |

| MOL004917 | Glycyroside | 37.25 | 0.79 | 0 | LR |

| MOL004924 | (-)-Medicocarpin | 40.99 | 0.95 | 2 | LR |

| MOL004935 | Sigmoidin-B | 34.88 | 0.41 | 6 | LR |

| MOL004941 | (2R)-7-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)chroman-4-one | 71.12 | 0.18 | 15 | LR |

| MOL004945 | (2S)-7-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-8-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)chroman-4-one | 36.57 | 0.32 | 12 | LR |

| MOL004948 | Isoglycyrol | 44.7 | 0.84 | 7 | LR |

| MOL004949 | Isolicoflavonol | 45.17 | 0.42 | 15 | LR |

| MOL004957 | HMO | 38.37 | 0.21 | 27 | LR |

| MOL004959 | 1-Methoxyphaseollidin | 69.98 | 0.64 | 29 | LR |

| MOL004961 | Quercetin der. | 46.45 | 0.33 | 17 | LR |

| MOL004966 | 3′-Hydroxy-4′-O-Methylglabridin | 43.71 | 0.57 | 28 | LR |

| MOL000497 | Licochalcone a | 40.79 | 0.29 | 32 | LR |

| MOL004974 | 3′-Methoxyglabridin | 46.16 | 0.57 | 28 | LR |

| MOL004978 | 2-[(3R)-8,8-dimethyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrano[6,5-f]chromen-3-yl]-5-methoxyphenol | 36.21 | 0.52 | 31 | LR |

| MOL004980 | Inflacoumarin A | 39.71 | 0.33 | 15 | LR |

| MOL004985 | icos-5-enoic acid | 30.7 | 0.2 | 1 | LR |

| MOL004988 | Kanzonol F | 32.47 | 0.89 | 8 | LR |

| MOL004989 | 6-prenylated Eriodictyol | 39.22 | 0.41 | 8 | LR |

| MOL004990 | 7,2′,4′-trihydroxy-5-methoxy-3-arylcoumarin | 83.71 | 0.27 | 15 | LR |

| MOL004991 | 7-Acetoxy-2-methylisoflavone | 38.92 | 0.26 | 25 | LR |

| MOL004993 | 8-prenylated eriodictyol | 53.79 | 0.4 | 8 | LR |

| MOL004996 | Gadelaidic acid | 30.7 | 0.2 | 1 | LR |

| MOL000500 | Vestitol | 74.66 | 0.21 | 30 | LR |

| MOL005000 | Gancaonin G | 60.44 | 0.39 | 20 | LR |

| MOL005001 | Gancaonin H | 50.1 | 0.78 | 12 | LR |

| MOL005003 | Licoagrocarpin | 58.81 | 0.58 | 29 | LR |

| MOL005007 | Glyasperins M | 72.67 | 0.59 | 26 | LR |

| MOL005008 | Glycyrrhiza flavonol A | 41.28 | 0.6 | 17 | LR |

| MOL005012 | Licoagroisoflavone | 57.28 | 0.49 | 18 | LR |

| MOL005013 | 18α-hydroxyglycyrrhetic acid | 41.16 | 0.71 | 0 | LR |

| MOL005016 | Odoratin | 49.95 | 0.3 | 20 | LR |

| MOL005017 | Phaseol | 78.77 | 0.58 | 14 | LR |

| MOL005018 | Xambioona | 54.85 | 0.87 | 8 | LR |

| MOL005020 | Dehydroglyasperins C | 53.82 | 0.37 | 18 | LR |

| MOL000098 | Quercetin | 46.43 | 0.28 | 154 | LR |

Construction of network diagrams of compounds and corresponding targets

The compounds and corresponding targets in the DYY formula were imported into Cytoscape software to draw a compound-target network diagram (see Fig. 2). In this study, degree was selected as a measure of node importance. With the help of the Network Analyzer plug-in in Cytoscape software, the topology parameters of the network were calculated and analysed from the perspective of network node importance. Degree refers to the number of edges associated with a node. The greater the degree of a node is, the larger the node area in the graph. That is, the larger the node area is, the greater the importance of the node in the network. The compounds in Fig. 2 and their corresponding targets were used as network nodes. Figure 2 shows that one compound can act on multiple target genes, and multiple compounds can also act on one target gene at the same time. Among the compounds, MOL000422 (kaempferol), MOL000098 (quercetin), MOL003896 (7-Methoxy-2-methyl isoflavone), MOL004328 (naringenin), MOL000392 (formononetin) and MOL000358 (beta-sitosterol) occupied the largest area on the graph among all compounds and were important core compounds.

Fig. 2.

Compounds and corresponding targets network diagram. The green arrows in the figure represent the MOL numbers of the compound, and the red arrows represent the top five compounds with the largest area. The pink rectangles represent the target genes predicted by the compound. Lines represent the relationship between nodes. The larger the graph area is, the more connections there are to the node, and the more important the node is

Acquisition of disease target

A total of 251 genes related to COVID-19 were obtained by searching the Genecards database. The relevance score was used as the selection criterion to obtain the top 30 genes (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Top 30 genes related to COVID-19

| No | Gene symbol | Description | Relevance score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TNF | Tumor necrosis factor | 33.08 |

| 2 | IL6 | Interleukin 6 | 31.28 |

| 3 | CXCL8 | C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 8 | 31.05 |

| 4 | CD40LG | CD40 ligand | 30.56 |

| 5 | IL10 | Interleukin 10 | 30.33 |

| 6 | IFNG | Interferon gamma | 27.48 |

| 7 | CRP | C-Reactive protein | 25.76 |

| 8 | STAT1 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 | 22.73 |

| 9 | MBL2 | Mannose binding Lectin 2 | 22.1 |

| 10 | TP53 | Tumor protein P53 | 19 |

| 11 | CCL2 | C–C motif chemokine Ligand 2 | 18.13 |

| 12 | IL2 | Interleukin 2 | 17.68 |

| 13 | CCL5 | C–C motif chemokine Ligand 5 | 16.71 |

| 14 | IFNA1 | Interferon alpha 1 | 16.65 |

| 15 | EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | 16.29 |

| 16 | CXCL10 | C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 10 | 15.3 |

| 17 | TGFB1 | Transforming growth factor beta 1 | 14.98 |

| 18 | IL1B | Interleukin 1 beta | 13.78 |

| 19 | ACE2 | Angiotensin I converting enzyme 2 | 12.32 |

| 20 | CSF2 | Colony stimulating factor 2 | 11.95 |

| 21 | PPARG | Peroxisome proliferator Activated Receptor Gamma | 11.93 |

| 22 | CCR5 | C–C motif chemokine Receptor 5 (Gene/Pseudogene) | 11.37 |

| 23 | CXCL9 | C–X–C motif Chemokine Ligand 9 | 11.3 |

| 24 | GPT | Glutamic–pyruvic Transaminase | 11.12 |

| 25 | MAPK1 | Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase 1 | 11.09 |

| 26 | CASP3 | Caspase 3 | 10.88 |

| 27 | IFNB1 | Interferon beta 1 | 10.77 |

| 28 | ALB | Albumin | 10.68 |

| 29 | FGF2 | Fibroblast growth factor 2 | 10.53 |

| 30 | SFTPD | Surfactant protein D | 10.47 |

Intersection of drug targets and disease targets

The above DYY drug target genes were intersected with COVID-19 disease targets to obtain possible genes associated with DYY treatment of COVID-19. The results showed that there was a total of 45 genes associated with DYY treatment of COVID-19 (see Additional file 2: Fig. S2).

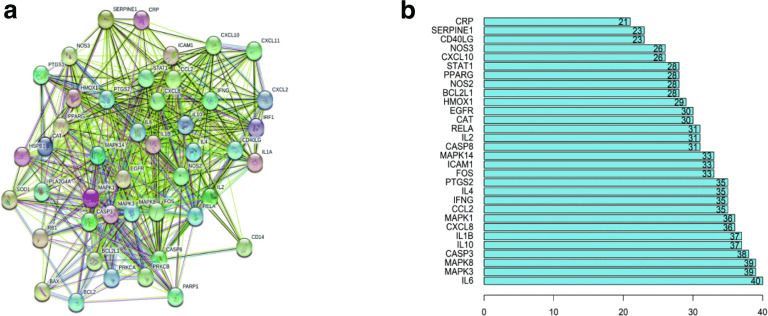

PPI analysis and core target screening

The STRING database was used to draw a PPI network diagram of DYY for COVID-19 (see Fig. 3a). As shown in Fig. 3a, the network diagram consisted of 45 nodes and 581 edges, for which the average node degree was 25.8, and the PPI enrichment p-value was < 1.0e−16. The above PPI network was processed using R language, and the top 30 core genes were selected (see Fig. 3b). Figure 3b shows that the top 30 core genes had a node degree greater than 21, and the top genes, such as IL6, MAPK3, MAPK8, CASP3, IL10, IL1B, CXCL8, MAPK1, CCL2, IFNG and IL4, had a higher number of connections than other genes, all showing 35 or more connections.

Fig. 3.

Protein interaction diagram and core gene bar chart. In the protein interaction diagram (a), the nodes represent proteins, and the connections represent interactions between proteins. The more connections there are, the greater the degree of connection. The node degree value indicates the number of connections between any node in the diagram and other nodes. In the core gene bar chart (b), the abscissa represents the number of genes, and the ordinate represents the name of the gene

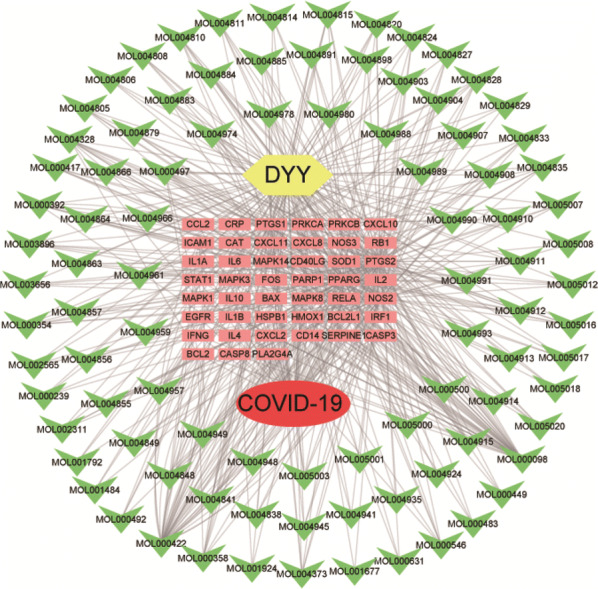

Construction of network visualization

The active ingredients of DYY, the targets corresponding to the active ingredients, and the targets predicted for COVID-19 were imported into Cytoscape software to build a drug-target-disease network diagram (see Fig. 4). The network had a total of 139 nodes (including 94 compound nodes and 45 gene nodes) and 546 connections.

Fig. 4.

Drug-target-disease regulation network diagram. The yellow polygon in the figure represents the drug (DYY), the red circle represents the disease (COVID-19), the green arrows represent the compounds, and the pink boxes represent the targets of action

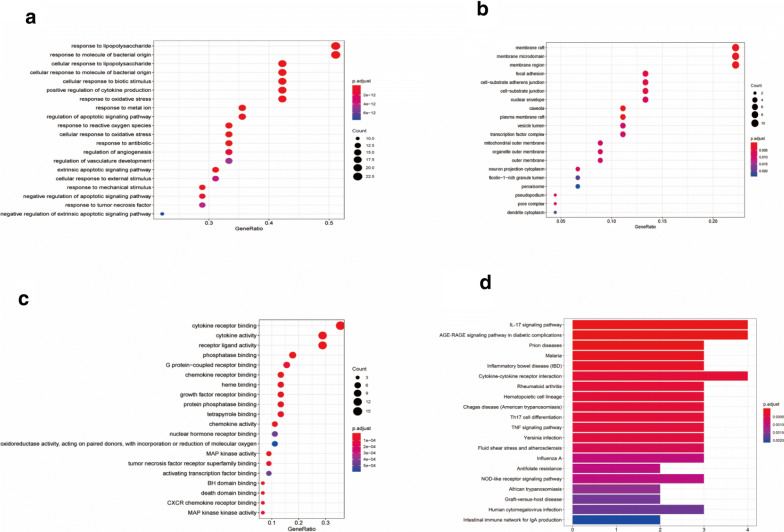

GO analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

The R language and DAVID database were used for GO enrichment analysis by using the above-mentioned targets of DYY to treat COVID-19, and the number of biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF) entries was 1,506, 33 and 83, respectively. The top 30 biological processes were screened and are represented as graphical bubbles (see Fig. 5a–c). The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified 40 signaling pathways, and the top 20 entries were selected and are represented by a bar graph (see Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

GO analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis graphs. In the bubble charts in (a–c), the ordinate represents the names of the BP, CC, and MF terms, respectively, and the abscissa represents the degree of enrichment. In (d), the ordinate represents the names of the pathways, and the abscissa represents the number of genes enriched in the pathway. The P value indicates the significance of enrichment. The smaller the P value is, the higher the significance of enrichment, and the redder the colour on the graph

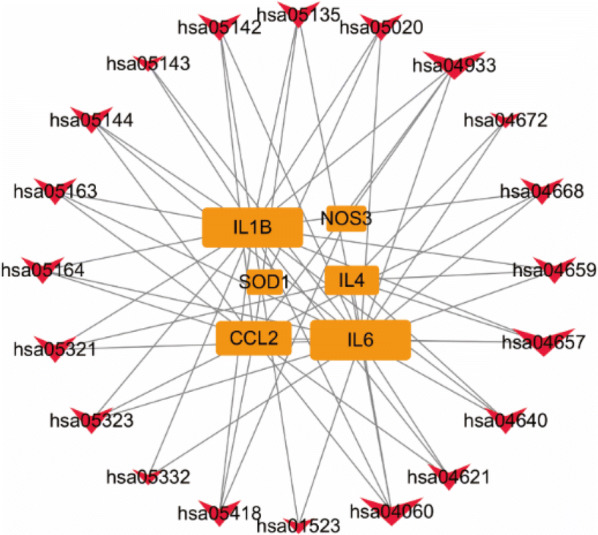

Construction of the KEGG relationship network

The top 20 pathways involved in DYY treatment of COVID-19 and the genes enriched in these pathways were imported into Cytoscape software to build a KEGG relationship network diagram (see Fig. 6). In Fig. 6, the pathways and the genes enriched in the pathways were used as network nodes, and we selected the top three pathways (hsa04657 (IL-17 signaling pathway), hsa04933 (AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications), and hsa0406 (cytokine–cytokine recev] ptor interaction pathway)) and top three target genes (IL6, ILIB, CCL2) enriched in these pathways according to degree.

Fig. 6.

KEGG relationship network diagram. The red arrows indicate the pathway IDs. The larger the arrow is, the greater the number of genes connected to the pathway. The orange box indicates the name of the gene. The larger the box is, the greater the number of pathways connected

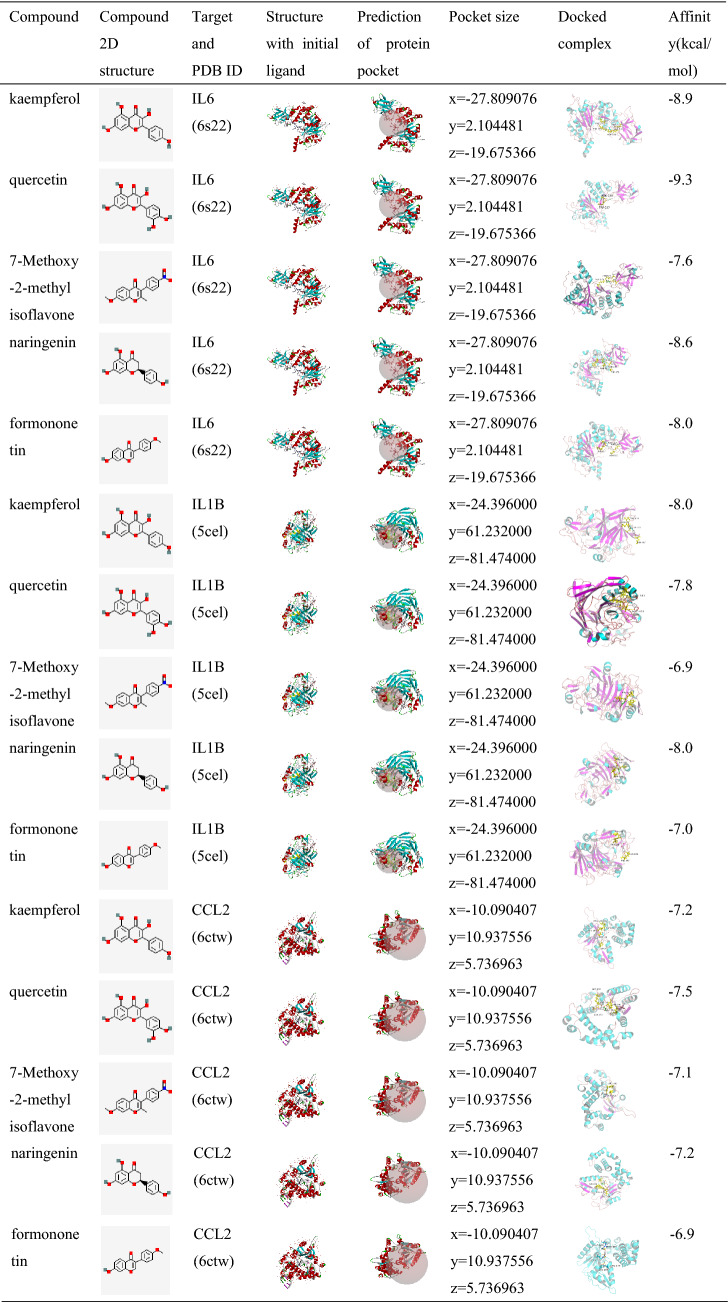

Molecular docking verification of core compounds and core target genes

The results obtained by the molecular docking software are shown in Table 3. The letters x, y and z were used to represent the size and position of the pocket. The final selected pocket is shown in bold in the column titled ‘Pocket size’. The results of the docking of the receptor and ligand are shown under ‘Docked complex’, and the residues docked with the small-molecule ligand are shown as yellow sticks. The structure with the initial ligand and the predicted protein pocket were processed by Discovery Studio 3.5 Client software, and the docked complex was processed by PyMOL software. As seen from Table 3, the scores for the five core compounds (kaempferol, quercetin, 7-Methoxy-2-methyl isoflavone, naringenin, formononetin) and protein crystal structures corresponding to the core target genes (IL6, IL1B, CCL2) were all greater than -5 kcal/mol, indicating that the compound had a certain affinity for the protein crystal structure. The interactions between some ligands (small-molecule compounds) and receptors (proteins) are shown in Additional file 3: Fig. S3. Additional file 3: Fig. S3 shows that the small-molecule compounds were tightly bound to the protein residues via various interactions.

Table 3.

Molecular docking results

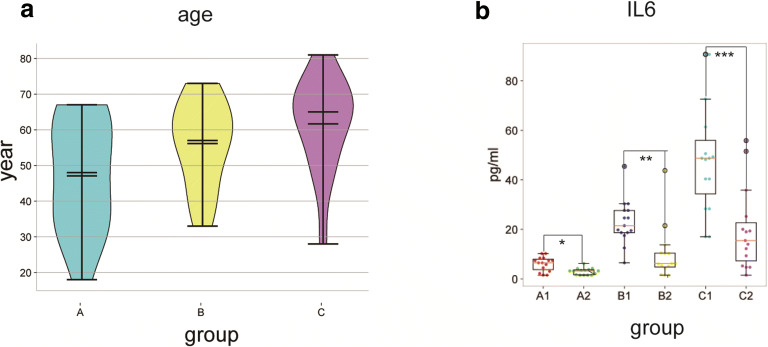

Clinical validation of the core target IL6

Of the 45 patients selected, 15 were mild cases (group A), 15 were moderate cases (group B), and 15 were severe cases (group C). The age distribution of each group of patients and changes in IL6 levels before and after treatment are shown in Fig. 7a, b, respectively. Compared with the severe cases, Fig. 7a shows that the mild and moderate cases were younger. Figure 7b shows that a majority of the patients had different levels of IL6 elevation before treatment (the normal reference value of IL6 is 0–7 pg/ml), and the increase in IL6 was most pronounced in severe cases. After treatment, IL6 decreased in all groups, and differences within each group before and after treatment were statistically significant.

Fig. 7.

Graph of patient age distribution and IL 6 levels. In (a), the abscissa represents group, and the ordinate represents age. In (b), the abscissa represents the group, and the ordinate represents the level of IL6, where A1, B1, and C1 represent patients before treatment while A2, B2, and C2 represent patients after treatment in each group. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. (n = 15 per group); *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, and***p < 0.001. the after treatment groups(A2, B2, C2) vs. the before treatment groups(A1, B1, C1)

Mechanism of action of DYY in the treatment of COVID-19

Based on the above studies, the specific mechanism of the action of DYY in the treatment of COVID-19 is shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Mechanism of action of DYY in the treatment of COVID-19

Discussion

As of April 6, 2020, the cumulative number of COVID-19 confirmed cases worldwide has exceeded 1.2 million. However, no vaccine or definitive antiviral drugs are available for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Therefore, it is crucial to find out medicines with confirmed curative effects for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 as soon as possible to improve the patient’s condition and prevent the ongoing outbreak of COVID-19.

In this study, we first searched and screened a database of traditional Chinese medicine database to obtain 174 DYY compounds and 7053 corresponding target genes. Ent-epicatechin, quercetin, mairin, beta-sitosterol, sitosterol, and stigmasterol are common compounds of two or more Chinese medicines. Studies have shown that quercetin can reduce apoptosis induced by hypoxia and rescue phosphorylation of AMPK [15]. Beta-sitosterol has antipyretic, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant functions and plays roles in cough and phlegm elimination, immune regulation and tissue repair [16, 17]. Stigmasterol is present in the membrane [18] and has anti-inflammatory effects [19]. The compound-target network diagram (Fig. 2) shows that there was a complex network relationship between the compounds and the targets. Kaempferol, quercetin, 7-Methoxy-2-methyl isoflavone, naringenin, formononetin, and beta-sitosterol had the largest number of targets and were core compounds.

By searching the disease database, we found a total of 251 genes related to COVID-19. Drug target genes and disease related genes were intersected, and a total of 45 target genes for DYY treatment of COVID-19 were finally obtained (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). These genes were analysed by PPI analysis to obtain the corresponding network diagram (Fig. 3a). Figure 3a shows that the target genes of DYY for the treatment of COVID-19 were not independent, and there was a certain relationship among these genes. The core gene map in Fig. 3b shows that the top-ranking genes were IL6, MAPK3, MAPK8, CASP3, IL10, IL1B, CXCL8, MAPK1, CCL2, IFNG, IL4, etc. These genes were mainly concentrated in the inflammatory response, immune modulation, and cellular stress processes, which indicated that they might play a key role in DYY treatment of COVID-19. It is well known that IL6, IL10, IL1B, and IL4 are all members of the interleukin family. Interleukins play an important role in transmitting information, regulating immune cells, mediating T and B cell activation, and responding to inflammation [20, 21]. CCL2 and CXCL8 belong to the chemokine family and are important inflammatory cytokines. They play an important role in the migration of Tregs to inflammatory tissues [22] and in immune regulation in the body [23]. MAPK3, MAPK8, and MAPK1 are members of the MAPK family and can participate in responses to potentially harmful abiotic stress stimuli [24].

At the same time, a network of drug active ingredients, target genes corresponding to the active ingredients and disease targets was constructed as shown in Fig. 4. We can see that one compound can act on multiple target genes. Similarly, one target gene can also correspond to multiple compounds. That is, multiple compounds can act on a common target. Based on the above analysis, we concluded that multiple active ingredients in the traditional Chinese medicine prescription DYY can act on COVID-19 through multiple targets.

Through functional enrichment analysis of target genes for DYY treatment of COVID-19, GO biological process and KEGG pathway enrichment maps were obtained (see Fig. 5). It can be seen from Fig. 5 that in the GO terms, the BP terms (Fig. 5a) were mainly associated with the cell’s response to processes such as lipopolysaccharide, molecule of bacterial origin, biotic stimulus, cytokine production, oxidative stress, and adaptive signaling pathways. CC terms (Fig. 5b) were mainly associated with various membranes, including membrane raft, membrane microdomain, membrane region, plasma membrane raft, nuclear envelope, and mitochondrial outer membrane, etc.; the terms were also associated with focal adhesion, cell-substrate adherens junction, cell-substrate junction, etc. The MF terms (Fig. 5c) were mainly associated with various receptors (cytokine, chemokine, growth factor, CXCR chemokine, G protein-coupled, nuclear hormone receptors), binding functions (phosphatase, heme, protein phosphatase, tetrapyrrole, BH domain, death domain, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily) and various cytokine, ligand, and kinase activities (cytokine, receptor ligand, MAP kinase, chemokine, oxidoreductase). The pathways involved in the KEGG enrichment pathway (Fig. 5d) were mainly the IL-17 signaling pathway, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway, cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, TNF signaling pathway, and NOD-like receptor signaling pathway. The diseases involved were mainly infectious and immune diseases. Infectious diseases included viral infectious diseases (prion diseases, influenza A, human cytomegalovirus infection, etc.), parasitic infectious diseases (malaria, Chagas disease, African trypanosomiasis, etc.) and bacterial infectious diseases (Yersinia infection). Immune diseases included inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and graft-versus-host disease.

As shown in Fig. 6, hsa04657 (IL-17 signaling pathway), hsa04933 (AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications), and hsa0406 (cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction pathway) enriched the highest number of genes, indicating that these pathways may play an important role in the mechanism of action of DYY in the treatment of COVID-19. The IL-17 signaling pathway is involved in the body’s immune response [25, 26] and inflammatory response [27]. The AGE-RAGE signaling pathway has important protective effects on bones and the heart and participates in oxidative stress response [25] and fibrosis transduction [22]. The cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction is a key pathway for regulating the cellular inflammatory response [28]. IL6, ILIB, CCL2 and other genes occupy a large rectangular area, indicating that there are more pathways connected to these genes. Therefore, it can be speculated that these genes play a key role in the mechanism of action of DYY in the treatment of COVID-19. IL6, ILIB, and CCL2 represent a wide range of inflammatory mediators and pathways. Many animal and human experiments have demonstrated that IL6 has a wide range of anti-inflammatory effects [29]. ILIB has analgesic, immunomodulatory, anti-hypoxia, and anti-inflammatory functions. CCL2 is an important inflammasome-associated chemokine [30]. Inhibition of CCL2 can reduce the infiltration of peripheral inflammatory cells such as monocytes and neutrophils [9]. NOS3 is a vasoprotective gene [31] that regulates vascular tone, blood pressure and platelet aggregation [32]. Research reports have shown that NOS3 can affect metabolism in the urea cycle of the methylation pathway, which is essential for preventing systemic inflammation [33].

By combining the core target gene bar chart (Fig. 3b) and the KEGG relationship network diagram (Fig. 6), we can see that IL6 is one of the most critical genes for anti-inflammatory and immune regulation in COVID-19 patients treated with DYY. Based on the comparison of COVID-19 patients before and after treatment with DYY, the IL6 level of COVID-19 patients increased to different degrees when they were admitted to the hospital but decreased after treatment, further confirming that DYY may play an important role in anti-inflammatory and immune regulation and may have other effects in the treatment of COVID-19 patients.

Conclusions

In summary, we speculate that DYY may play an anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory role in COVID-19 by acting on multiple target proteins, such as IL6, ILIB, and CCL2. The role of DYY involves a variety of biological processes, mainly signaling pathways such as the IL-17 signaling pathway, cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, and AGE-RAGE signaling pathway, involved in diabetic complications. In short, DYY plays a role in COVID-19 treatment through multiple targets, multiple channels, and multiple pathways, making it worthy of clinical application and promotion. However, only part of the specific mechanism of action of DYY has been clinically verified, and further verification is needed in subsequent experiments.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Composition diagram of DYY.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2. Venn diagrams of drug targets and disease targets.

Additional file 3: Fig. S3. Two-dimensional structure diagram of ligand-receptor interaction. The interaction forces between the small-molecule compound ligands and protein receptors in Fig. S3 are shown in different colors. Purple to gray represent electrostatic, van der waals, convalent bond, water and metal interaction, respectively.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hui Tian for her writing assistance.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- DYY

Dayuanyin

- TCMSP

Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform

- DL

Drug-like

- OB

Oral bioavailability

- BBB

Blood–brain barrier

- PPI

Protein–protein interaction

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- MO

Magnolia officinalis

- AM

Amomum

- AS

Arecae semen

- HP

Herbaceous peony

- SR

Scutellariae radix

- AR

Anemarrhenae rhizoma

- LR

Licorice

- BP

Biological process

- CC

Cellular component

- MF

Molecular function

Authors’ contributions

XR, PD, LL, JZ conceived and designed the study; XR, PD wrote the paper; KZ, JH, HX, DD, SH and XC performed the study and analyzed the data; LL and JZ supervised the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Young medical talents in Hubei Province, the Research Program on prevention and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 with traditional Chinese medicine through the Shaanxi Province Special Emergency Fund in 2020 (2020-YJ005), and the Research Program on prevention and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 with traditional Chinese medicine through the Ankang Special Emergency Fund in 2020 (AK2020XG06, AK2020XG07).

Availability of data and materials

The data used to support the results of this study can be obtained from the first author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional ethics board of Hubei NO.3 People’s Hospital of Jianghan University (2020 -19). Informed consent of the study was waived because of the retrospective nature and the analysis used anonymous clinical data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Footnotes

Xiaofeng Ruan and Peng Du are equal frst authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Liming Liu, Email: 31641191@qq.com.

Jianjun Zhang, Email: 18963989890@189.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13020-020-00346-6.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meo SA, Alhowikan AM, Al-Khlaiwi T, Meo IM, Halepoto DM, Iqbal M, Usmani AM, Hajjar W, Ahmed N. Novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV: prevalence, biological and clinical characteristics comparison with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:2012–2019. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202002_20379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang J, Yan L-L. Observation on 100 cases of influenza treated with Chaihuda original drink. Inner Mongolia Tradit Chin Med. 2005;24:29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang T. Hang Qi is a scourge, and evil protozoa-on the etiology, pathogenesis and treatment of infectious SARS pneumonia. J Tianjin Univ Tradit Chin Med. 2003;22:58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo Y-Y, Xu L-R, Wu S-T, Qiu Q, Li L-P, Meng P-F, et al. Exploring the effect mechanism of Chai Yu Da Yuan Yin on the prevention and treatment of AIDS based on Fuqi theory. Shizhen Tradit Chin Med Tradit Chin Med. 2019;30:1677–1678. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding RC, Long QH, Liu L, Wang P, Huang XY, Ming SP. Experience of using Dayuan Decoction to treat new coronavirus pneumonia. J Tradit Chin Med. 2020;70:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruan XF, Feng YW, Zhao K, Huang JC, Chen Y, Liu LM. Treating one elderly patient with severe COVID-19 from the angle of treating damp-warm disease. Shanghai J Tradit Chin Med. 2020;54:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Yang J. A bioinformatics investigation into the pharmacological mechanisms of the effect of Fufang Danshen on pain based on methodologies of network pharmacology. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5913. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40694-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong Z, Zhou Y, Wang J. Identifying potential drug targets in hepatocellular carcinoma based on network analysis and one-class support vector machine. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10442. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46540-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie R-F, Liu S, Yang M, Xu JQ, Li Z-C, Zhou X. Effects and possible mechanism of Ruyiping formula application to breast cancer based on network prediction. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5249. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41243-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noureldein MH. In silico discovery of a perilipin 1 inhibitor to be used as a new treatment for obesity. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:457–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pires DE, Ascher DB. CSM-lig: a web server for assessing and comparing protein-small molecule affinities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W557–W561. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ru J, Li P, Wang J, Zhou W, Li B, Huang C, et al. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J Cheminform. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong Y, Duan L, Chen H-W, Liu Y-M, Zhang Y, Wang J. Network pharmacology-based prediction and verification of the targets and mechanism for panax notoginseng saponins against coronary heart disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:6503752. doi: 10.1155/2019/6503752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo G, Gong L, Sun L, Xu H. Quercetin supports cell viability and inhibits apoptosis in cardiocytes by down-regulating miR-199a. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47:2909–2916. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1640711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikewuchi JC, Ikewuchi CC, Ifeanacho MO. Nutrient and bioactive compounds composition of the leaves and stems of Pandiaka heudelotii: a wild vegetable. Heliyon. 2019;5:e01501. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Meng Y, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Geng X, Li M, Li Z, Zhang D. Functional nano-catalyzed pyrolyzates from branch of Cinnamomum camphora. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2019;26:1227–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bansal R, Sen SS, Muthuswami R, Madhubala R. A plant like cytochrome P450 subfamily CYP710C1 gene in leishmania donovani encodes sterol C-22 desaturase and its over-expression leads to resistance to amphotericin B. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Sá Müller CM, Coelho GB, Araújo MC, Saúde-Guimarães DA. Lychnophora pinaster ethanolic extract and its chemical constituents ameliorate hyperuricemia and related inflammation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;242:112040. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt NH, Ball HJ, Hansen AM, Khaw LT, Guo J, Bakmiwewa S, Mitchell AJ, Combes V, Grau GE. Cerebral malaria: gamma-interferon redux. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:113. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee HC, Yu HP, Liao CC, Chou AH, Liu FC. Escin protects against acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice via attenuating inflammatory response and inhibiting ERK signaling pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11:5170–5182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Z, Jegga AG, Bezerra JA. Gene-disease associations identify a connectome with shared molecular pathways in human cholangiopathies. Hepatology. 2018;67:676–689. doi: 10.1002/hep.29504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turi KN, Shankar J, Anderson LJ, Rajan D, Gaston K, Gebretsadik T, et al. Infant viral respiratory infection nasal immune-response patterns and their association with subsequent childhood recurrent wheeze. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1064–1073. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2348OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad MK, Abdollah NA, Shafie NH, Yusof NM, Razak S. Dual-specificity phosphatase 6 (DUSP6): a review of its molecular characteristics and clinical relevance in cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2018;15:14–28. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2017.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berntsen NL, Fosby B, Tan C, Reims HM, Ogaard J, Jiang X, et al. Natural killer T cells mediate inflammation in the bile ducts. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:1582–1590. doi: 10.1038/s41385-018-0066-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishikawa Y, Shimoda N, Fereig RM, Moritaka T, Umeda K, Nishimura M, et al. Neospora caninum dense granule protein 7 regulates the pathogenesis of neosporosis by modulating host immune response. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84:e01350. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01350-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pang X, Zhang K, Huang J, Wang H, Gao L, Wang T, Sun Y, Chen L, Wang J. Decryption of active constituents and action mechanism of the traditional Uighur prescription (BXXTR) alleviating IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in BALB/c mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1822. doi: 10.3390/ijms19071822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He Y, Shi J, Nguyen QT, You E, Liu H, Ren X, et al. Development of highly potent glucocorticoids for steroid-resistant severe asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:6932–6937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816734116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu X, Burfeind KG, Michaelis KA, Braun TP, Olson B, Pelz KR, Morgan TK, Marks DL. MyD88 signalling is critical in the development of pancreatic cancer cachexia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10:378–390. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christersdottir T, Pirault J, Gisterå A, Bergman O, Gallina AL, Baumgartner R, et al. Prevention of radiotherapy-induced arterial inflammation by interleukin-1 blockade. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2495–2503. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang RT, Wu D, Meliton A, Oh MJ, Krause M, Lloyd JA, et al. Experimental lung injury reduces krüppel-like factor 2 to increase endothelial permeability via regulation of RAPGEF3-Rac1 signaling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:639–651. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0668OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malik R, Rannikmäe K, Traylor M, Georgakis MK, Sargurupremraj M, Markus HS, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 3 novel loci associated with stroke. Ann Neurol. 2018;84:934–939. doi: 10.1002/ana.25369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johns R, Chen ZF, Young L, Delacruz F, Chang NT, Yu CH, Shiao S. Meta-analysis of NOS3 G894T polymorphisms with air pollution on the risk of ischemic heart disease worldwide. Toxics. 2018;6:44. doi: 10.3390/toxics6030044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Composition diagram of DYY.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2. Venn diagrams of drug targets and disease targets.

Additional file 3: Fig. S3. Two-dimensional structure diagram of ligand-receptor interaction. The interaction forces between the small-molecule compound ligands and protein receptors in Fig. S3 are shown in different colors. Purple to gray represent electrostatic, van der waals, convalent bond, water and metal interaction, respectively.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the results of this study can be obtained from the first author upon reasonable request.