Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an unprecedented health crisis worldwide, with the numbers of infections and deaths worldwide multiplying alarmingly in a matter of weeks. Accordingly, governments have been forced to take drastic actions such as the confinement of the population and the suspension of face-to-face teaching.

In Spain, due to the collapse of the health system the government has been forced to take a series of important measures such as requesting the voluntary incorporation of final-year nursing and medical students into the health system.

The objective of the present work is to study, using a phenomenological qualitative approach, the perceptions of students in this exceptional actual situation.

A total of 62 interviews were carried out with final-year nursing and medicine students from Jaime I University (Spain), with 85% reporting having voluntarily joined the health system for ethical and moral reasons.

Results from the inductive analysis of the descriptions highlighted two main categories and a total of five sub-categories. The main feelings collected regarding mood were negative, represented by uncertainty, nervousness, and fear.

This study provides a description of the perceptions of final-year nursing and medical students with respect to their immediate incorporation into a health system aggravated by a global crisis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Phenomenological study, Health crisis, Students, Health sciences

1. Introduction

For the first time in recent years a disease of pandemic proportions has violently shaken the foundations of the entire global community, affecting an exceptionally vulnerable aging society characterized by a prevalence of modern chronic diseases (Arabi et al., 2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of the new coronavirus disease “COVID-19” in February 2020 (Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it, n.d.). On 30 January, WHO declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). On 11 March, the WHO Director-General characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic (WHO, 2020), and stated that “there is a high risk of COVID-19 spreading to other countries around the world”. Within a few months, Europe became one of the continents most affected by the disease, with Italy and Spain being particularly vulnerable to the devastating effects of the virus. In March 2020, WHO made the assessment that COVID-19 could be characterized as a pandemic and within a few weeks the number of declared cases in Spain reached a total of 219,329 and 25,613 deaths (Spain: WHO COVID-19 Dashboard, n.d.).

The health situation forced the Spanish government to declare a state of emergency (BOE.es - Sumario del día 14/03/2020 [WWW Document], n.d.) and establish a national quarantine with total paralysis of the production sector, leading to serious consequences for economic growth and development. The national educational system has been affected by unprecedented historical measures, with university programs being taken remotely via distance learning without physical class attendance. This situation is particularly complex in health sciences studies and health-related fields which require a minimum practical training component. Nursing and medical schools have been profoundly affected due to this unprecedented health situation.

The health system gradually collapsed due to the tremendous increase in number of COVID-19 cases, and hospital infrastructures were not able to transfer/manage patients with respiratory conditions. This led to the need to increase the numbers of short stay units, hospitalization beds, general supplies, ventilators, and protective and safety equipment (PPE). This shortage was particularly marked in the provision of biosafe protective clothing and equipment among health professionals. The percentage of COVID-19-positive health workers was estimated to be close to 20.4% (44,000 infected professionals) by the first week of May, and increasing with a rapid growing rate (Coronavirus: 44.758 sanitarios infectados en España [WWW Document], n.d.). This situation triggered the need to hire new staff and strengthen existing health services.

Of the measures discussed by the Spanish expert committee, one was highlighted by the government to be implemented as soon as possible. On the basis of the state of emergency declared due to the COVID-19 outbreak, the government made the extraordinary commitment of hiring final-year students from nursing and medical degrees (BOE.es - Documento BOE-A-2020-3700 [WWW Document], n.d.). Although these future professionals are non-registered nurses and doctors, they cover mandatory clinical rotations throughout their 6- and 4-year medicine and nursing programs, respectively, in a controlled work situation supervised by experts. The personal and professional outlook of these students changed completely with the opportunity to voluntarily face a real health emergency with potential exposure to COVID-19.

Qualitative research focused on health professionals' experiences in pandemic situations such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (Gearing et al., 2007) or influenza (Corley et al., 2010a; Kam et al., 2013) provides very helpful information in this regard. A structured analysis of the subject's individual experience is a valuable tool to better organize resources and human infrastructure due to the unpredictable nature of emergency situations. In addition, the qualitative study of the subject's experiences (health professionals) when facing situations with isolated infected patients is critical for elaborating a contingency plan to prevent problems in the professional's performance (Kam et al., 2013).

Given this unprecedented global health crisis and the exceptional actions taken by the competent authorities to voluntarily incorporate final-year students to the healthcare system, we consider that this study could address a new global reality. Knowledge of the experiences, perceptions, and fears of future healthcare professionals will form the core of a rapid and better future response. Thus, the aim of this phenomenological research focuses on the study of the individual experiences lived by final-year nursing and medical students for the first time facing the immediate reality of professional incorporation into a strongly threatening environment.

2. Methods

In this study, we implemented a phenomenological theory approach to achieve the main aims proposed. Phenomenology is understood as the study of phenomena based on a careful description of the informant's experiences in the manner in which they have been lived. This vision appears to be a very useful instrument for those working in the field of health sciences (Toombs, 2001). Our phenomenological qualitative design followed a procedure associated with focus-group data collection to engage the essence, constituents, and understanding of this experience. We used the methodology of reduction for the search and analysis of all possible meanings (Dahlberg, 2006).

2.1. Informants and data collection

We used a convenience sampling method with final-year nursing and medical students from Jaime I University (Castellón, Spain). One of the main characteristics of this qualitative methodology is that the researcher is intimately involved in data collection and analysis, which implies an intimate interaction between the researcher and the study participants (Cypress, 2015). We initially contacted the participants with information on the purpose and design of the study.

Phenomenological studies use a semi-structured interview format in order to garner knowledge by facilitating a free flow of information from participants. Thus, the use of an open-ended discourse opens up the appearance of relevant information to the participants, helping to capture the described lived experiences (Ingham-Broomfield 2015). Given the exceptional situation of the national emergency status, personal face-to-face interviews had to be substituted by the use of semi-structured interviews through the Qualtrics platform (Barnhoorn et al., 2014) (Provo, Utah, USA). Data were collected from March to April 2020.

2.2. Data analysis

Data analysis proceeded following the general outlines derived from Giorgi and Giorgi, 2004 (Giorgi and Giorgi, 2004) through the methodology of reduction. Data were analyzed to identify interrelated themes and insights through a qualitative process which requires reading the whole text several times and a process of coding which facilitates the identification of themes and subthemes. Following Giorgi's proposal, the first step of analysis was to gain access to the essence of the experience, making sense of the whole statement by the discrimination of meaning units for transformation into groups of meaning. Finally, all transformed meanings were synthesized into a consistent statement related to the subject's experience (Hycner, 1985).

2.3. Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was requested from the ethics committee of the Jaume I University Ethical Review Board. The study was conducted in accordance with national and international standards following the 1995 Helsinki Declaration (JAVA, 2013). The study was in compliance with the Spanish Fundamental Law on Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights. All the participants were informed in writing of the aims of the study and their right to decline to participate or withdraw at any time.

3. Results

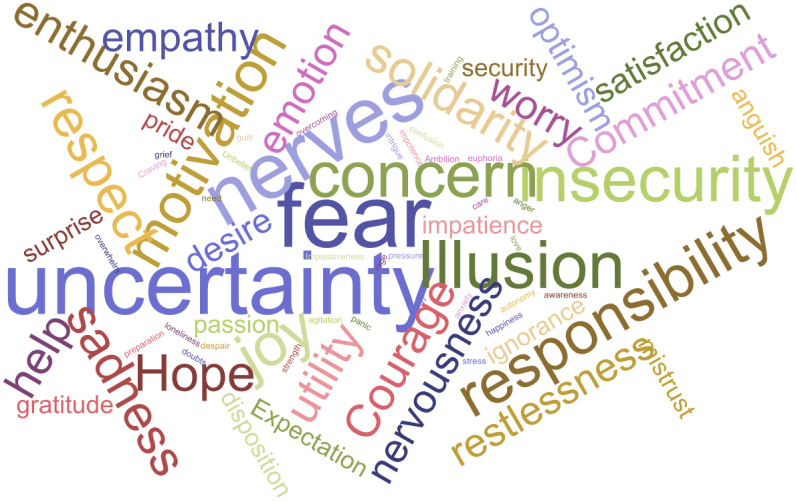

A total of 147 questionnaires were distributed to eligible final-year nursing (n = 65) and medical students (n = 82). The completed questionnaire ratio was 42.17%. Fig. 1 reflects the flow of respondents. The semi-structured interview questionnaire designed to achieve the different objectives proposed is represented in Table 1 . The demographic characteristics of participating students are summarized in Table 2 . The categories and sub-categories emerging from the interview data are listed in Table 3 .

Fig. 1.

Reflected is the flow of respondents.

Table 1.

Guide used for the semi-structured interview questionnaire.

| Questionaire distributed to the students |

|---|

| What is your opinion on the government's decision to have recruit final-year nursing and medical students to join the health system during the COVID-19 outbreak? |

| Are you willing to join as a volunteer? |

| If yes or not. What are the reasons? |

| Describe 5 feelings that can define your current mood in relation to fact of joining the health system. |

| What are your main concerns and/or fears of working with COVID patients? No word limits. |

| If you join the health system, what situation or situations are you afraid to face? |

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participated students.

| Participated students (N = 80) ƒ(%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 (22.6) |

| Female | 48 (77.4) |

| University degree | |

| Nursing | 29 (46.8) |

| Medicine | 33 (55.2) |

| Age | |

| 25 | |

| s.e.m. | ±7.44 |

| Previous experience | |

| Yes | 6 (9.7) |

| Not | 56 (90.3) |

| Pending subjects | |

| Yes | 6 (9.7) |

| Not | 56 (90.3) |

Table 3.

Categories and sub-categories emerging from the interview data.

| Categories | Sub-categories | Labels |

|---|---|---|

| Pandemic perception of the emergency and a threatening clinical context as a risk of infection. | Fear to the risk of infection |

Infection Disease Safety Exposure Personal Protection Overwhelmed Health |

| Fear to the risk of transmission to the family context |

Transmission vector Cohabitation Home Grandparents Family home Vulnerable Group Cross-infection Asymptomatic Loved ones Contagion |

|

| Fear to the health system disorganization and lack of PPEs |

PPEs Shortage disorganization risk Lack of protection Lack of resources Lack of coordination Saturation |

|

| Fear to be unprepared in the current emergency working situation. | Lack of knowledge and skills in the professional practice |

Lack of trust Skills Confidence Accuracy Obstacle Clumsiness, Hesitation Technical proficiency Insecurity Inexperience Not useful burden Lack of skills Frustration |

| Fear to cope and manage difficult situations |

Passing Death Therapeutic Relationship Emotional impact Family problems Loneliness Death Young patients |

Students' attitudes on voluntary acceptance of the Spanish government appeal.

The students' descriptions were fully transcribed and are identified as description 1 (D1), description 2 (D2), etc.

From a total of 62 informants, 85.5% (n = 53) reported that they had voluntarily agreed to join the health system in the current emergency situation; conversely, 14.5% (n = 9) reported that they had not agreed to join the health system. The reasons given by the students who joined voluntarily were as follows: the need for help given the current situation (n = 32; 65.3%), moral obligations (n = 9; 18.4%), altruistic and vocational aspects related to the healthcare profession (n = 6; 12.2%), and finally, humanitarian and cooperation reasons (n = 2; 4.1%). Students who responded that they had not joined the health system reported their reasons as follows: concerns surrounding not having enough physical or legal protection and the possibility of transmitting the infection to their relatives (n = 4; 44%), belonging to or having family members belonging to a vulnerable group (n = 2; 22.2%), and concerns that joining the health system would interfere with their university studies (33.3%; n = 3).

3.1. Categories and sub-categories

3.1.1. Category 1. Perception of the pandemic and the threatening clinical context as posing a risk of infection

This category reflects the perceptions of nursing and medical final-year students with respect to their working conditions. The students' perceptions were focused on facing these situations with a lack of PPE, the significant threat of infection, and the corresponding risk of transmission to family members.

3.1.1.1. Sub-category 1.1. Fear of the risk of infection

Students described fears of finding a high-risk working situation with infected patients, with the need to use PPE. They were also confronted by a lack of knowledge on how to use this equipment. Moreover, they described their concerns with not being adequately protected and becoming infected.

-

•

[…] my only concern is knowing how to protect myself adequately when facing infected patients (D39).

-

•

[…] getting infected or not knowing how to maintain the confinement measures (D32).

-

•

[…] we are very concerned about exposure, especially for our own safety considering the PPE shortage (D7).

3.1.1.2. Sub-category 1.2. Fear of transmission risk to the family context

It is of note that the major concern of students (n = 28; 45.16%), was the possibility of getting infected, being vectors of the virus in their homes, and infecting their relatives.

-

•

[…] if unfortunately I get infected, my greatest fear would be remaining asymptomatic and harming the relatives with whom I live by infecting them as well (D36).

-

•

[…] not managing properly and vectoring the infection from one patient to another, and coming back home not knowing if I am infected, causing risk to my family because my brother and father are a vulnerable group (D17).

Some students also described the risk of infection as a large concern when living with relatives belonging to vulnerable groups.

-

•

[…] my worry is not having a place to stay in case I join the health system. Two of my relatives are part of the vulnerable group and I would be very afraid of coming back home after working at the hospital (D9).

3.1.1.3. Subcategory 1.3. Fear of health system disorganization and lack of PPE

Another of the main concerns raised by the students in their descriptions was clearly related to their perception of disorganization at the hospital, shortage of general medical equipment (particularly PPE), lack of trained personal, and numbers of patients above the actual capacity of hospital services.

-

•

[…] virus exposure, lack of PPE, and hospital patient saturation (D43).

-

•

[…] risk of infection due to the lack of PPE available at the hospitals right now (D22).

-

•

[…] my biggest concern is not having the adequate PPE to prevent virus infection (D36).

-

•

[…] lack of equipment, not feeling safe when working with infected patients, not knowing whether they might have COVID19, lack of general hospital supplies (D20).

-

•

[…] not having proper PPE and good post-infection treatments (D33).

3.1.2. Category 2. Fear of being unprepared in the current emergency working situation

This second category included the descriptions highlighted by students regarding their fear of newly joining the health system, lack of professional and previous experience, and facing difficult situations exceeding their capacity.

3.1.2.1. Subcategory 2.1. Lack of knowledge and skills in professional practice

The students described feeling prepared due to the practical training received during their studies; however, they felt afraid of facing clinical situations which could be overwhelming and being responsible for complications caused as a result of their performance.

-

•

[…] we have successfully completed most of the degree subjects, but I'm not 100% confident about performing my job without hesitation. I am scared of committing medical malpractice (D14).

Some other students described feeling afraid of not being useful when facing clinical situations that exceeded their abilities, and being a burden on the experienced professionals.

-

•

[…] I am very concerned about exposure. Moreover, I am concerned about facing critically infected patients and not having enough skills to take quick action without being a nuisance to others (D7).

3.1.2.2. Subcategory 2.2. Fear of coping with and managing difficult situations

It is interesting that some of the students described feeling prepared for professional practice but not for end-of-life situations or supporting family members at the time of mourning.

-

•

[…] I am afraid of dealing with the death of young patients, not using PPE correctly, and facing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (D26).

-

•

[…] my biggest fear and concern is seeing patients dying because they can't get adequate attention or because we cannot do anything else to help them (D31).

-

•

[…] I am afraid of not knowing how to establish a patient–nurse relationship in these cases, not to knowing what to do to avoid infection, and not to knowing the right thing to do regarding COVID-19 symptoms (D10).

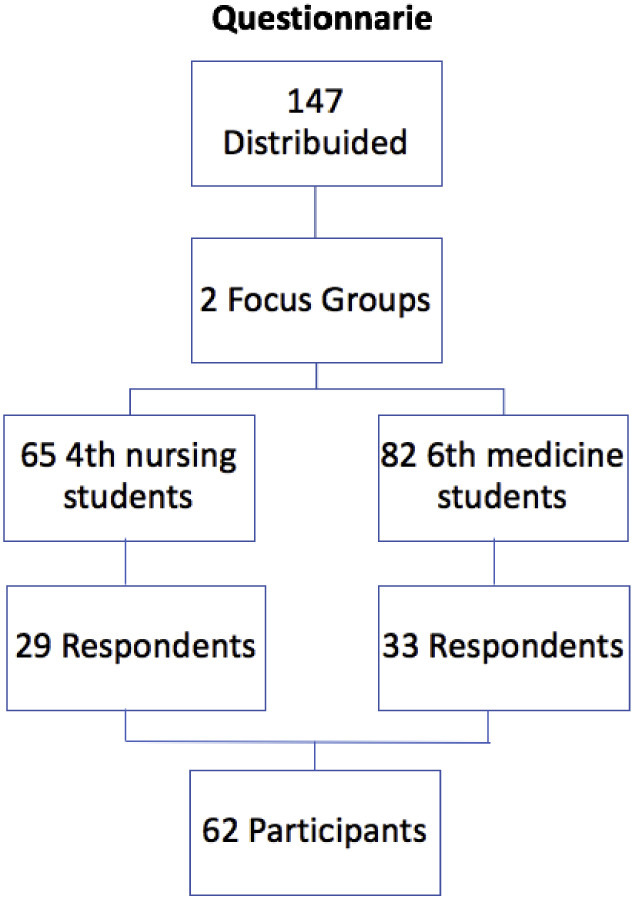

3.2. Cloud of thoughts “Students' feelings and mood”

Based on the emotions, perceptions, and feelings gathered in the students' descriptions regarding their voluntary incorporation into the health system, we have created an easy and representative word cloud image (Fig. 2 ). This is a practical and simplified way to analyze qualitative data, allowing us to highlight the most important and frequent words in student descriptions.

Fig. 2.

Depicted is a word cloud image. Highlighted are the most important and frequent words in student descriptions.

4. Discussion

The main objective of this research was to study, from a qualitative point of view, final-year nursing and medical students' perceptions and fears triggered by the immediate voluntary incorporation into professional practice requested by the Spanish government as an exceptional COVID-19 measure.

Health science professionals must have a strong foundation for practice based on human relationships. These professionals are thus completely dedicated to the patients, and require strong ethical, altruistic, and vocational values (Rosa Jiménez-López et al., 2012). In particular, nursing and medical professionals must develop their practice based on specific human values that highlight the importance of ethical values (Omery et al., 1995).

One of the latest WHO reports, the State of the World's Nursing Report 2020 (State of the World's Nursing Report - 2020, n.d.), reveals a significant lack of nursing staff, depicting a global deficiency of 5.9 million professionals. In addition, the WHO Director-General, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has emphasized that throughout history nurses have been at the forefront of the global fight against health-threatening epidemics and pandemics, as is currently the case. Currently, worldwide sanitary staff are showing their compassion and courage in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [WWW Document], n.d.).

Health workers are at the front line of the COVID-19 outbreak response. The latest published infection rates for health workers are estimated to be close to 20% in Lombardy, 26% in Spain, and 19.6% in the Netherlands (The Lancet, 2020). This situation has caused an incredible demand for health professionals, who in most cases make a voluntary decision to form part of the health system. Moreover, the COVID-19 crisis has provided an unexpected opportunity for some retired professionals to return to work in the health system. According to our results, it is clear that over 85% of our informants responded positively to the government appeal. Nursing and medical students voluntarily accepted the government's request due to ethical, moral, altruistic, and vocational reasons.

There are two reasons why COVID-19 is a major threat to life. First, it has been demonstrated to affect not only the elderly population suffering from additional health problems but healthy individuals as well. This disease is much more severe than the usual seasonal influenza. Secondly, the virus demonstrates exponential growth, with an enormous infection rate (Gates, 2020). One of the main fears that students described was the risk of being infected by COVID-19. This finding is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that students in a similar situation of risk react with fear and anxiety for their own safety (Cassidy, 2006). In addition, in previous pandemic situations, the same reaction was observed in experienced health professionals (Balicer et al., 2006; Corley et al., 2010b; Ives et al., 2009; McMullan et al., 2016). However, these professionals were willing to work despite the potential risk of infection (Corley et al., 2010b; Leiba et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2008).

Besides personal health, fear among participants regarding the susceptibility of their significant others to infection was reported. This appears to be especially significant in the case of participants with family members with associated risk factors. More than 45% of the students reported a fear of the possibility of infecting relatives. These perceptions are consistent with other studies which demonstrate that the three most important goals in the future professional performance of science students are correlated to family safety, sense of achievement, and happiness (Michal Rassin, 2010; Rassin, 2008). Jiménez-López et al. (2016) reported in a qualitative study that the main personal values of nursing students included being good children and caring for their grandparents. These results are in accordance with our results, which described how transmission of the disease to the family was one of the main student concerns.

As with other fast-spreading infections, media coverage can be considered as an effective way to mitigate disease spread during the initial stage of an outbreak (Zhou et al., 2020). In a situation of generalized panic, COVID-19 has come to reach the deepest corners of our minds and life. At the ground zero of COVID-19 infection (Wuhan, Hubei, China), signs of fatigue, exhaustion, and frustration, as well as fear of being infected and transmitting the virus, were detected in health workers, paramedics, volunteers, virologists, and those working in the media. These emotions and feelings prevailed among those involved in the first line of control and press coverage of the disease (Chen et al., 2020). These facts justify the students' perception of fear observed in their descriptions.

Another significant finding from this study was related the perceptions of professional training and competency of participants when facing difficult situations. Students felt a lack of professional knowledge and hands-on skills, which generated serious emotions of suffering. This perception was aggravated by the health crisis caused by the pandemic. Students' fears and perceptions are fully justified (Ramírez et al., 2011) and are in accordance with the experiences of other professionals working in hospitals in the case of pandemics such as SARS in 2003 (Maunder, 2004) or COVID-19 (Chen et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020). It is also important to highlight the great importance of psychological support for health workers in these situations (Shojaei and Masoumi, 2020; Williamson et al., n.d.).

Another aspect outlined by the students was coping with patient death. Different studies have already addressed the need among medical and nursing students to incorporate coping strategies focused on dealing with the dying patient (Trivate et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2005)

5. Conclusion

This study has allowed us to learn the perceptions of final-year nursing and medicine students with respect to their voluntary professional incorporation into an extraordinary situation as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the threats posed by COVID-19, students were willing to accept the government appeal due to social commitment, vocation, and professional ethics. However, students conveyed messages based on negative emotions such as anxiety, fear, uneasiness, and serious concern with respect to the critical health situation caused by the pandemic. Moreover, they reported a notable fear of possible infection and further transmission of the disease to their families. A disorganized scenario, lack of PPE and professional experience, and coping with difficult situations such patient death were also major student concerns.

In this pandemic we have had to rely on final-year students being able to work side-by-side with health professionals in order to minimize system overload. This study provides a rich description of the perceptions of final-year nursing and medical students with respect to their immediate incorporation into a health system aggravated by a global crisis. Moreover, this study will help to detect student learning deficits, which will allow universities to better optimize the curriculum and student training needs in order to ensure their success as future professionals. Finally, we believe that this research will provide a helpful tool to learn from the current global emergency situation and will serve as a reference for future potential pandemics.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

The data presented in this manuscript are original and are not under consideration elsewhere. In the present work we do not have any conflict of financial interest.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the Permanent Seminar on Educational Innovation at the Jaime I, university, “Learning based on clinical problems” (ECLIBAP).

References

- Arabi Y.M., Murthy S., Webb S. COVID-19: a novel coronavirus and a novel challenge for critical care. Intensive Care Med. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05955-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balicer R.D., Omer S.B., Barnett D.J., Everly G.S. Local public health workers’ perceptions toward responding to an influenza pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhoorn J.S., Haasnoot E., Bocanegra B.R., van Steenbergen H. QRTEngine: an easy solution for running online reaction time experiments using Qualtrics. Behav. Res. Methods. 2014;47:918–929. doi: 10.3758/s13428-014-0530-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOE.es - Documento BOE-A-2020-3700 [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2020-3700 (accessed 4.6.20).

- BOE.es - Sumario del día 14/03/2020 [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://boe.es/boe/dias/2020/03/14/ (accessed 4.6.20).

- Cassidy I. Student nurses’ experiences of caring for infectious patients in source isolation. A Hermeneutic Phenomenological Study. 2006:1247–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Liang M., Li Y., Guo J., Fei D., Wang L., He L., Sheng C., Cai Y., Li X., Wang J., Zhang Z. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley A., Hammond N.E., Fraser J.F. International Journal of Nursing Studies The experiences of health care workers employed in an Australian intensive care unit during the H1N1 Influenza pandemic of 2009: A phenomenological study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010;47:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley A., Hammond N.E., Fraser J.F. The experiences of health care workers employed in an Australian intensive care unit during the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009: a phenomenological study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010;47:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus: 44.758 sanitarios infectados en España [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.redaccionmedica.com/secciones/sanidad-hoy/coronavirus-sanitarios-infectados-espana-contagio--2979 (accessed 5.7.20).

- Cypress B.S. Qualitative research. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2015;34:356–361. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg K. The essence of essences - the search for meaning structures in phenomenological analysis of lifeworld phenomena. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being. 2006;1:11–19. doi: 10.1080/17482620500478405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gates B. Responding to Covid-19 — a once-in-a-century pandemic? N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/nejmp2003762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing R.E., Saini M., Mcneill T. 2007. Experiences and Implications of Social Workers Practicing in a Pediatric Hospital Environment Affected by SARS 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, A.P., Giorgi, B.M., 2004. The descriptive phenomenological psychological method, in: Qualitative Research in Psychology: Expanding Perspectives in Methodology and Design. American Psychological Association, pp. 243–273. doi: 10.1037/10595-013. [DOI]

- Hycner R.H. Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data. Hum. Stud. 1985;8:279–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00142995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham-Broomfield R. The Issue of Nurses Understanding Research. Aust. Nurs. Midwifery J. 2015;22:36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives J., Greenfield S., Parry J.M., Draper H., Gratus C., Petts J.I., Sorell T., Wilson S. Healthcare workers’ attitudes to working during pandemic influenza: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAVA Declaration of Helsinki World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Bull. world Heal. Organ. 2013;79:373–374. (doi:S0042-96862001000400016 [pii) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-López F.R., Roales-Nieto J.G., Seco G.V., Preciado J. Values in nursing students and professionals: an exploratory comparative study. Nurs. Ethics. 2016;23:79–91. doi: 10.1177/0969733014557135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam L., Rn K., Nurse R., Shuk H., Maria Y., Professional F. Perceptions of emergency nurses during the human swine influenza outbreak: a qualitative study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2013;21:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiba A., Goldberg Avi, Hourvitz A., Amsalem Y., Aran A., Weiss G., Leiba R., Yehezkelli Y., Goldberg Avishay, Levi Y., Bar-Dayan Y. Lessons learned from clinical anthrax drills: evaluation of knowledge and preparedness for a bioterrorist threat in israeli emergency departments. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2006;48:194–199.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Chen M., Zheng X., Liu J. Screening for Chinese medical staff mental health by SDS and SAS during the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder R. The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto: lessons learned. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2004;359:1117–1125. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullan C., Brown G.D., O’Sullivan D. Preparing to respond: Irish nurses’ perceptions of preparedness for an influenza pandemic. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2016;26:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michal Rassin R.N. Values grading among nursing students - differences between the ethnic groups. Nurse Educ. Today. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it (accessed 4.6.20).

- Omery A., Henneman E., Billet B., Luna-Raines M., Brown-Saltzman K. Ethical issues in hospital-based nursing practice. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 1995;9:43–53. doi: 10.1097/00005082-199504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez A.V., Angelo M., González L.A.M. Vivencia de estudiantes de enfermería de la transición a la práctica profesional: Un enfoque fenomenológico social. Texto e Context. Enferm. 2011;20:66–73. doi: 10.1590/s0104-07072011000500008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rassin M. Nurses’ professional and personal values. Nurs. Ethics. 2008;15:614–630. doi: 10.1177/0969733008092870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa Jiménez-López F., Segura-Sánchez A., Moreno San Pedro E., Teresa Lorente-Molina M. Profile of personal values for health sciences students. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2012;12:415–426. [Google Scholar]

- Shojaei S.F., Masoumi R. The importance of mental health training for psychologists in COVID-19 outbreak. Middle East J. Rehabil. Heal. Stud. In Press. 2020 doi: 10.5812/mejrh.102846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spain: WHO COVID-19 Dashboard [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://covid19.who.int/region/euro/country/es (accessed 5.7.20).

- State of the World's Nursing Report - 2020 [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.who.int/publications-detail/nursing-report-2020 (accessed 4.8.20).

- The Lancet COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toombs S.K. Springer; Dordrecht: 2001. Introduction: Phenomenology and Medicine; pp. 1–26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trivate T., Dennis A.A., Sholl S., Wilkinson T. Learning and coping through reflection: Exploring patient death experiences of medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2019:19. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1871-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed 4.8.20).

- Williams C.M., Wilson C.C., Olsen C.H. Dying, death, and medical education: student voices. J. Palliat. Med. 2005;8:372–381. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Medicine, N.G.-O., 2020, undefined, n.d. COVID-19 and experiences of moral injury in front-line key workers. academic.oup.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wong, T., Koh, G., Cheong, S., … H.L.-A.-A.O., 2008, undefined, n.d. Concerns, perceived impact and preparedness in an avian influenza pandemic–a comparative study between healthcare workers in primary and tertiary care, annals.edu.sg. [PubMed]

- Zhou W.K., Wang A.L., Xia F., Xiao Y.N., Tang SY1. Effects of media reporting on mitigating spread of COVID-19 in the early phase of the outbreak. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020;17:2693–2707. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2020147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]