Abstract

Research on the recovery domains beside clinical recovery of people with severe mental illness in need of supported accommodations is limited. The aim of this study was (1) to investigate which recovery interventions exist for this group of people and (2) to explore the scientific evidence. We conducted a scoping review, including studies with different designs, evaluating the effectiveness the recovery interventions available. The search resulted in 53 eligible articles of which 22 focused on societal recovery, six on personal recovery, five on functional recovery, 13 on lifestyle-interventions, and seven on creative and spiritual interventions. About a quarter of these interventions showed added value and half of them initial promising results. The research in this area is still limited, but a number of recovery promoting interventions on other areas than clinical recovery have been developed and evaluated. Further innovation and research to strengthen and repeat the evidence are needed.

Keywords: Mental health recovery, Societal participation, Severe mental illness, Supported accommodation, Supported housing

Introduction

Most people with severe mental health problems can recover and live in the community with or without support (Keet et al. 2019). A relatively small group of people (10–20%) has long-term, severe and complex needs but consumes 25–50% of the mental health and social care budget (Killaspy et al. 2016). Killaspy et al. (2016) therefore referred to this group as a ‘low volume, high needs’ group. These people often have major negative and ongoing positive symptoms in addition to other mental, social and physical health problems. They need the permanent support of supported housing facilities or residential care (Killaspy 2016; Leff et al. 2015; Sandhu et al. 2017; van Hoof et al. 2015). These services offer practical daily care, nursing and support to persons with severe mental illness (SMI) in their daily lives, aiming at improvements in recovery and functioning. Nevertheless, people with long-term SMI still report unmet needs concerning health, work, social relations and daily activities (Bitter et al. 2016; de Heer-Wunderink et al. 2012a, b).

Over the past two decades, there have been increasing attention for what it means to recover from a mental illness. There is a growing recognition that recovery is more than the remission of psychiatric symptoms. The current vision is that recovery is ‘a way of living a satisfying, hopeful and contributing life even with limitations caused by illness’ (Anthony 1993). Several authors described that recovery comprises multiple aspects (Couwenbergh and van Weeghel 2014; Davidson et al. 2005; Leamy et al. 2011; Resnick et al. 2005). An example of a classification that is used often in the Netherlands is: clinical, functional, social and personal recovery (Couwenbergh and van Weeghel 2014). First, clinical recovery refers to a decrease in clinical symptoms such as hallucinations, anxiety or depressive feelings (Liberman et al. 2002). The other dimensions are of more recent attention. Functional recovery refers to executive functioning such as planning and problem solving (Savla et al. 2012). Societal recovery is about regaining everyday functioning in areas such as work, social relationships, housing and leisure (Farkas and Anthony 2010). Personal recovery refers to a person’s own experience and is about hope, empowerment, self-determination and regaining the identity of someone who is living a meaningful life despite the presence of symptoms (Anthony 1993; van Gestel-Timmermans et al. 2012a). Recovery dimensions are closely related and influence each other constantly in complex processes (Davidson et al. 2005).

Treatment and support for people with SMI therefore should ideally focus on all dimensions of recovery and be tailored to a person’s individual needs (Bitter et al. 2016; van Weeghel et al. 2019a). Several types of psychosocial interventions have been developed to support people with SMI in their recovery on the dimensions next to the clinical one (Slade et al. 2014). Rehabilitation methods, for example, focus on clients’ personal goals and wishes regarding daily life and societal recovery. Examples of well-known methods in this field are the ‘choose-get-keep’ approach, also referred to as Boston psychiatric rehabilitation, (Anthony et al. 2002), illness management and recovery (IMR) (Mueser et al. 2006) and the strengths model of case management (Rapp and Goscha 2006). Other methods focus on a specific aspects of life. These include individual placement and support (IPS) in which people are supported to gain and stay in competitive employment (Burns et al. 2007; Michon et al. 2011). Other methods aim to improve cognitive functioning or practical skills; these include social and independent living skill modules, cognitive remediation programs and cognitive adaptation training (CAT) (Hansen et al. 2012; Marder et al. 1996; Stiekema et al. 2015). More recently, interventions have been developed especially focusing on personal recovery, sometimes provided by experts-by-experience (Boevink et al. 2016; Fox and Horan 2016; van Gestel-Timmermans et al. 2012b).

There is an increasing amount of research on the effectiveness of interventions addressing several outcomes. IPS, for example, has shown to have a strong and consistent effect on vocational outcomes (Michon et al. 2011). Furthermore, the Boston approach has been shown to increase social functioning and goal attainment (Swildens et al. 2011). Studies concerning several other interventions, such as the strengths model and those aimed at personal recovery, have reported varying results (Ibrahim et al. 2014; Lloyd-Evans et al. 2014; Tse et al. 2016).

Although research on these interventions have shown promising results, studies on interventions for clients living in supported accommodations such as residential care and supported housing services, however, lack behind (Chilvers et al. 2006; McPherson et al. 2018). Available studies were executed mainly with participants who live independently with a relative small amount of support. Also, most of the available studies concern interventions that focus on a selective group of motivated clients who can formulate concrete goals (Michon et al. 2011; Swildens et al. 2011). We cannot assume that these practices are suitable and valuable for people with SMI living in supported accommodations, of which is known their needs are more complex and some have lost their motivation and goals in life (Bitter et al. 2016; de Heer-Wunderink 2012).

For that reason, this study aims to identify and evaluate studies on psychosocial interventions focusing on the dimensions of recovery besides the clinical one, in supported accommodation for people with severe mental illness. The findings of this study can contribute to the further development of the content and quality of the support offered by supported accommodation.

Aims of the Study

With this review, we aim to answer the following questions:

Which interventions have been applied and evaluated to support clients with severe mental illness using supported accommodation in their recovery on domains besides clinical recovery?

What scientific evidence is available about the outcomes of these interventions?

Methods

We choose to conduct a scoping review, as these are established for use when the objective is to examine the extent, range and nature of research activity in a certain field and to summarize and disseminate the research findings (Pham et al. 2014). We followed the steps described by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) in their framework for the execution of a scoping review: (a) identify the research question, (b) identify relevant studies, (c) select the studies, (d) chart the data and (e) collate, summarize and report the results.

Search Strategy

To answer our first research question, we searched the following databases: PubMed, Psycinfo, Embase and Cinahl (January 2018, Update December 2019). These databases were chosen to cover medical (PubMed and Embase) as well as psychological (Psycinfo) and nursing (Cinahl) literature. We formulated and combined search terms concerning: (a) the setting and population (mental disorder/illness, schizophrenia, psychosis, inpatient rehabilitation, supported accommodation, sheltered housing, housing facility, community housing, community facility, supported housing, residential facility and residential care), (b) the scope and outcome of the intervention (psychosocial, societal, recovery, functioning, rehabilitation, health, wellness and cognition), and (c) study type (clinical trial, randomized controlled trial, evaluation study, experimental trial, naturalistic study, follow up study, quasi-experimental and case study).

To select studies that corresponded with our research aims, we formulated inclusion and exclusion criteria. We included peer-reviewed articles that were published in English from January 2000 till December 2019; aimed at adult clients with severe mental illness receiving services from housing services or comparable long-term (> 1 year) supported accommodation; evaluated psychosocial interventions focussing on personal, functional or societal recovery outcomes; evaluated the outcomes of an intervention on the client level; and evaluated outcomes by means of effect evaluation all types of designs except for expert opinions and case studies. As we aimed to give an overview of existing interventions for this group, we also included protocol papers and checked if there were results published already. To be able to provide a clearly defined answer to the research questions and to keep the results manageable, we also formulated exclusion criteria. Studies were excluded if they primarily focussed on substance abuse; intellectual and/or developmental disability, including brain damage; or on homelessness; or if they were executed in developing countries.

Study Selection Process

In the first and second selection phase, the first two authors each screened a separate part of the titles from the initial search, and of the remaining papers they screened the abstracts on relevance. When there was doubt, the selection was made in consensus. The first and second author determined final inclusion by discussing the interpretation of the inclusion criteria in certain cases. When doubt persisted about an abstract, the article was included so that a more careful decision could be made in the next phase.

In the third phase, the first and second author read the full-text of the remaining articles and made a final selection. In this final phase, both authors each read half of the articles independently. Again, articles about which doubt existed were discussed until consensus was reached. The selected studies then were categorised in a qualitative synthesis, based on the dimensions of recovery: societal, functional and personal, and additional in vivo categories were made when needed.

Outcome Evaluation

Our second aim was to evaluate what is already known about the outcomes of these interventions. Therefore, the second phase of the qualitative synthesis was evaluation of each study to understand the status of the available evidence of each intervention found. First, we formulated categories of designs based on Evans’ hierarchy of evidence (2003): randomized (controlled) study, uncontrolled longitudinal study, or other (all other designs except case studies and expert opinions). Next, we evaluated the results of relevant outcomes and (where possible) the effect sizes of these results. Again, three options were possible: Large or medium effects, small effects, or neutral, unclear, unknown or not convincing yet. Based on these criteria, we concluded there was one of three options: (a) added value when a randomized control trial (RCT) resulted in small, large or medium effects, (b) promising first results when other designs than RCTs showed positive results, or (c) no evidence for the effectiveness yet when there were neutral or negative results or no results yet. The first and second author executed this quality assessment independently. Each assessed an equal part and then discussed the results until they reached a consensus. This review is part of a larger research project which received ethical approval from the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Elisabeth Hospital in Tilburg (NL41169.008.12).

Results

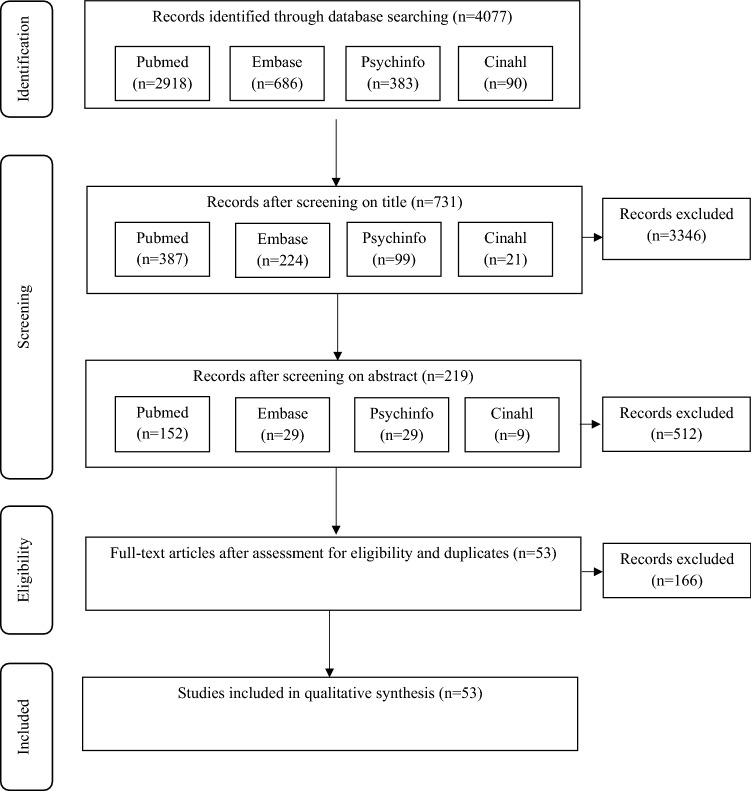

Fifty three articles met the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of the search, while Table 1 shows the results of the qualitative synthesis of the included articles. Five categories were formed. Three were based on the often distinguished dimensions of the recovery process: societal recovery, personal recovery and functional recovery, and two were formed in vivo: lifestyle, and cultural and spiritual.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Type, amount and evidence of included studies

| Type of intervention | Including | No. of studies | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Societal recovery | Approaches aiming at personal goals, (social) skills training, occupational therapy | 22 |

4 added value 11 promising results 7 no evidence yet |

| Personal recovery | Peer run, empowerment, confidence, hope, meaning | 6 |

2 added value 4 promising results |

| Functional recovery | Cognitive remediation/training, cognitive adaptation | 5 |

3 added value 2 no evidence yet |

| Lifestyle | Health promotion, exercise, healthy meals | 13 |

7 promising results 6 no evidence yet |

| Spiritual and creative | Tai chi, music therapy, art therapy | 7 |

3 added value 3 promising results 1 no evidence yet |

Most of the included studies focused on societal recovery (n = 22), addressing psychiatric rehabilitation approaches, occupational therapy and skills training. Studies concerned with personal recovery (n = 6) focused on peer-run programs, illness management and recovery, and interventions aiming at increasing empowerment. Studies in the functional recovery category (n = 5) examined cognitive training or remediation. Those in the lifestyle category (n = 13) were aimed at a healthy lifestyle, (e.g. physical exercise and healthy eating). The last category, cultural and spiritual interventions (n = 7), looked at tai chi, music therapy and art therapy.

Evaluation of Results of the Interventions

We evaluated the outcomes of all included studies (see Table 2 for a summary). Following is a description of the overall picture for each category.

Table 2.

Results of qualitative synthesis

| Authors | Design and study duration | Setting | Study population (N) | Intervention | Main outcomes | Main findings | Added value/promising first result/no evidence for effectiveness yet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Societal recovery | |||||||

| Park and Han (2018) |

Quasi-experimental pretest–posttest Duration: 5 weeks |

Rehabilitation centers | People with chronic schizophrenia (n = 41) | CEP-S: Communication Enhancement Program |

Communication skills Empathy Relationship skills Problem-solving skills |

Increased communication skills and relationship skills | Promising first results |

| Beentjes et al. (2018) |

Exploratory cluster RCT Duration: 12 months |

Extensive inpatient and/or outpatient psychiatric treatment including case management at nine MHC institutes, including supported housing | People with SMI (N = 41) | e-IMR + IMR | Illness management, self-management, recovery, symptoms, quality of life, and general health | No significant results and low e-IMR use | No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| Sheridan et al. (2018) |

Qualitative, written diary data Duration: 9 months |

Mental health services including 28% supported accommodation | People with enduring mental illness (N = 34) | Volunteer partner group, supported socialisation programme to stimulate social/leisure activities | n/a | Positive findings on: involvement ‘normalising’ life, sense of connectedness, physical health, and facilitating engagement with culture, integrate socialising into identity, perceived social capacity | Promising first results |

| Bitter et al. (2017) |

Cluster RCT Duration: 20 months |

Sheltered/supported housing facilities |

People suffering from SMI (N = 263) 71% inpatients |

Comprehensive approach to rehabilitation (CARe) Methodology |

Functioning Personal recovery Quality of life |

Quality of life increased and amount of care needs decreased in both groups | No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| Loi et al. (2016) |

Pre-post, non- randomized, study Duration: 6 weeks |

Residential facility | Older adults suffering from SMI (N = 5) | Short educational training course on using the internet and touch screen |

Social isolation Self esteem Internet use |

No sign improvements or worsening in both outcomes | No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| Magliano et al. (2016) |

Controlled non-randomized study Duration: 2 months |

Residential facilities | People suffering from SMI (N = 114) | VADO Approach: Skills assessment and definition of goals (based on Falloon’s CBT and inspired by Boston (or choose-get-keep) approach) | Functioning | Positive result on functioning | Promising first results |

| Killaspy et al. (2015) |

Cluster RCT Duration: 12 months |

Inpatient rehabilitation units | People suffering from SMI (N = 344) | Staff training program designed to increase patients’ engagement in activities | The degree to which patients were engaged in activity over the previous week | No difference between the groups in engagement in activities | No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| Sanches et al. (2015) |

Multi site RCT Duration: 12 months |

FACT teams and supported and sheltered housing facilities | People suffering from SMI | Boston university approach to psychiatric rehabilitation (BPR; aka choose-get-keep) |

Societal participation Patients’ experience of success Quality of life Recovery |

Protocol | Results not known yet |

| Anthony et al. (2014) |

Pre-post study Duration: 18 months |

28 service programs |

People suffering from SMI (N = 238) 49% sheltered facility |

Residential and employment goal setting procedure in a choose-get-keep rehabilitation program |

Employment status Residential status Earnings |

Participants with residential goals improved sign on residential status and earnings; intervention completers improved on employment status – Participants with employment goals improved significant on employment status and earnings |

Promising first results |

| Lindstrom et al. (2012) |

Prospective pre-test, post-test, and follow up test Duration: 6 months |

Supported or sheltered housing facilities |

People suffering from SMI (N = 17) 82% inpatients |

Home based occupational therapy intervention aiming at identifying, realising and sustaining meaningful daily occupations |

Goal attainment Motor and process skills Social interaction Satisfaction with daily occupations ADL Psychiatric symptoms |

Sign improvements on goal attainment, social interaction, and satisfaction with daily occupations, ADL and psychiatric symptoms | Promising first results |

| Ellison et al. (2011) |

Pre-post design Duration: 12 months |

State-wide implementation in several community facilities and supervised facilities |

People suffering from SMI (N = 511 and 221) controls for the analysis of service use and costs (40% inpatients) |

Intensive psychiatric rehabilitation based on choose-get-keep model | Role functioning on several domains Service use and service costs | A positive effect on residential status and earnings for completers | Promising first results |

| McMurran et al. (2011) |

Pragmatic multi centre RCT Duration: 1.5 year |

Community settings including residential or supported care settings |

340 planned suffering from personality disorder |

Psycho education combined with problem solving (PEPS) therapy | Social Functioning (SFQ) | Protocol | No results yet |

| Fagan-Pryor et al. (2009) |

Retrospective outcome evaluation Duration: 3 years prior to- and 3 year post-implementation |

Inpatient psychiatric facility | Male veterans suffering from SMI (N = 47) | Psychiatric rehabilitation and recovery based program based on choose-get-keep model with focus on housing |

Discharge Community tenure Number of admissions |

– Significant larger community tenure in discharged participants pre-post implementation | Promising first results |

| Levitt et al. (2009) |

RCT Duration: 12 months |

Supportive housing | 104 persons with SMI | Illness management and recovery |

Illness Management and Recovery Scales Psychosocial functioning Quality of life Symptoms |

Significant difference in self-reported and clinician ratings of illness management, symptoms and psychosocial functioning of the quality of life scale | Added value |

| Pratt et al. (2008); Mueser et al. (2010) |

RCT Duration: 3 years |

Community residents, |

Older adults (> + 50 years) suffering from SMI (N = 183) 50% inpatients |

HOPES program: Social skills training and health management; 24 months |

Psychosocial functioning Community functioning Self-efficacy Health |

– Significant improvements in performance measures of social skills, psychosocial and community functioning, negative symptoms, and self-efficacy |

Added value |

| Vandevooren et al. (2007) |

Retrospective repeated measures design Duration: Prior to program: Annually over a 6-year period, before and after, 1 year follow up |

Residential home | People suffering from SMI (N = 25) | Systematic rehabilitation approach based on choose-get-keep model |

Community tenure Number of admissions Living situation |

– Significant change in community tenure over 7 year period | Promising first results |

| Seo et al. (2007) |

Quasi experimental design Duration: 2 months |

Inpatient ward in psychiatric hospital | Persons diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 74) | Social skills group training based on Liberman and Bellack modules |

Social skills Self esteem Assertiveness skills Problem-solving skills Conversational skills |

Differences in improvements of a number of social skills and self-esteem in favour of the intervention group | Promising first results |

| Pioli et al. (2006) |

Partially randomized multi centric trial Duration: 12 months |

Residential and day care centres |

People diagnosed with schizophrenic disorder (N = 98) 33% living in sheltered facilities |

VADO: Skills assessment and definition of goals |

Social functioning Psychiatric symptoms |

Significant improvement on psychiatric symptoms and social functioning | Promising first results |

| Rogers et al. (2006) |

RCT Duration: 24 months |

Intensive care receivers of State Department of Mental Health |

Adults suffering from major mental illness (N = 135) 50% inpatients |

Psychiatric vocational rehabilitation (PVR) using choose-get-keep model |

Psychiatric symptoms Quality of life Self esteem Vocational & educational status |

No sign differences over time in employment status, symptoms, quality of life or self-esteem | No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| Oka et al. (2004) |

Retrospective study Duration: Minimal 3 yrs. follow up |

Previously long term hospitalized persons, recently discharged and living independently or in a residential home | Persons diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 52) | Hybrid occupational therapy and supported employment |

Hospitalization Community tenure Social functioning |

Social functioning improved significantly greater after supported employment was started Mean number of hospitalization decreased Community tenure increased significantly |

Promising first results |

| Anzai et al. (2002) |

RCT Duration: 1 year |

Inpatient facility | Persons diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 32) | Illness self-management skills training program based on the community re-entry module of Liberman et al. |

Psychotic symptoms Knowledge and skills Rehabilitation skills |

Significant improvement in knowledge and (rehabilitation) skills in the intervention group Patients in the intervention group spent significantly more time in community in comparison to the control group |

Added value |

| Tsang and Pearson (2001) |

Cluster randomized pilot test Duration: 3 months |

Community-based staffed residential facilities | Persons diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 97) | Social skills training in the context of vocational rehabilitation |

Work related social skills, self-perceived Social skills in role play exercise Job motivation checklist Vocational outcome and adjustment |

Work related social skills; self-perceived and measured with role play were both significantly higher in the two training groups Training group with follow up support most successful in job search |

Added value |

| Personal recovery | |||||||

| Nowak et al. (2018) |

Pre-post evaluation Duration: 6 weeks |

Clinics | People diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 46) | Recovery-oriented cognitive behavioral workshop |

Recovery Psychosocial functioning |

No significant change over time in total recovery Improvement regarding confidence and hope, feeling less dominated by symptoms, psychosocial functioning and psychopathology |

Promising first results |

| Boevink et al. (2016) |

RCT Duration: 24 months |

2 community treatment teams and 2 sheltered housing organisations |

Persons suffering from severe mental illness (N = 163) 28% inpatients |

User run recovery programme TREE |

Empowerment Mental health confidence Loneliness |

Sign more mental health confidence Less care needs Less self-reported symptoms Less likelihood of institutional residence |

Added value |

| Mancini et al. (2013) |

Quasi-experimental design Duration: 6 months |

Psychiatric hospitals | People suffering from SMI (N = 110) | Pro-recovery; a 14-week consumer developed approach including structured group-sessions | Pro-recovery Evaluation Instrument: social satisfactions; quality of life, well-being, recovery | Significant effect on consumer’s perception of the recovery attitudes of staff | Promising first results |

| Park and Sung (2013) |

Repeated-measure design with matched controls Duration: 10 weeks |

Psychiatric hospitals | Persons diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 46) | The empowerment program for schizophrenic patients: A nursing intervention focusing on patients’ strength and hopes of recovery |

Helplessness Recovery (patient report and nurse report) |

Significant effect on helplessness and recovery | Added value |

| Willemse et al. (2009) |

Pilot evaluation Duration: 12 weeks |

Long stay ward of three psychiatric hospitals and one sheltered housing | Older people (mean age: 67) (N = 36) | Searching for meaning in life-program |

The Philadelphia geriatric center morale Quality of life |

Significant increase in life satisfaction | Promising first results |

| Randal et al. (2003) |

Matched control evaluation study Duration: depending on individual trajectories |

Inpatient rehabilitation unit | 9 people with treatment resistant schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | Individual, flexible, recovery-focused multimodal therapy (21 months) | Positive and negative symptoms, rehabilitation | Reduction in positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and in general psychopathology symptoms. General behavior scores on the Rehabilitation Evaluation of Hall and Baker were clinically improved | Promising first results |

| Functional recovery | |||||||

| Schutt et al. (2017) |

Pre-post pilot study Duration: 2 months |

Group home | 6 residents | Cognitive remediation | Neurocognitive performance | No significant gains in cognitive performance | No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| Stiekema et al. (2015) |

Cluster RCT Duration: 24 months |

Long stay departments of 3 institutions | 100 planned | Cognitive adaptation training of nurses and specialists |

Executive functioning Cognitive strengths and weakness Everyday functioning Quality of life Empowerment |

Protocol | Results not known yet |

| Sánchez et al. (2013) |

RCT Duration: 3 months |

Psychiatric hospital | Persons diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 84) | REHACOP, integrative cognitive remediation program that taps all basic cognitive functions |

Neuro-cognition Clinical symptoms Functioning |

Significant effect on neuro-cognition, negative symptoms, disorganization, and emotional distress | Added value |

| Lindenmayer et al. (2012) |

RCT Duration: 3 months |

Persons diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 59) (93% inpatients) |

Cognitive remediation (CR) + social cognitive intervention | Social cognition and neurocognitive functions, psychopathology and social functions | Combined CR with emotion perception remediation produced greater improvements in emotion recognition, emotion discrimination, social functioning, and neurocognition compared with CR alone | Added value | |

| Medalia et al. (2001) |

RCT Duration: 5–6 weeks |

Inpatient psychiatric centre | Persons with schizophrenia (N = 54) | Remediation of cognitive problem solving skills |

Independent community living Verbal knowledge, judgement, and problem solving Verbal memory and narrative recall |

For independent living change scores, a significant between-group difference was found | Added value |

| Healthy lifestyle | |||||||

| Looijmans et al. (2019) |

Multi-site randomized controlled pragmatic trial Duration 12 months |

Flexible Assertive Community Treatment (F- ACT) teams and sheltered living teams | SMI patients (N = 140) | Multimodal lifestyle approach, including a web-based tool to improve patients’ cardiometabolic health | Primary: differences in waist circumstance at 6 and 12 months Secondary: BMI and metabolic syndrome Zscore |

No statistical significant differences found on the p and s outcomes Readiness to change dietary behavior improved |

No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| Sweeney et al. (2019) |

RCT and cost effectiveness evaluation Duration 8 months |

Residential and non-residential community mental health services | Smokers with SMI (N = 382) | Quitlink utilizing the existing mental health peer workforce to link SSMI to a tailored smoking quitline service |

Continuous abstinence Secondary: 7-day abstinence, increased quit attempts, and reductions in cigarettes per day, cravings and withdrawal, mental health symptoms and other substance use, and improvements in quality of life |

Protocol | No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| Ringen et al. (2018) |

Prospective naturalistic intervention study Duration: 7 months |

University hospital and a private inpatient psychiatric care facility | Long term inpatients (N = 83) | Motivational interventions, psychical activity and establishment of a basic infrastructure regarding activity and diet | Psychical activity, motivation, self-esteem, life satisfaction, functioning, symptoms | No increase of physical activity level. Triglyceride levels and numbers of smokers were significantly reduced and a significant decrease in symptom levels was observed | No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| O’Hara et al. (2017) |

Structured interviews and qualitative data: two focus groups and field notes Duration: 12 weeks |

Supportive housing | People with SMI | Peer based group Lifestyle balance | Feasibility, acceptability, adaptations |

Participants attended on average 8/12 sessions Perceived it as helpful and satisfactory |

Promising first results |

| Looijmans et al. (2017) |

Cluster RCT Duration: 12 months |

Residential and long-term teams of 2 mental health care organizations | People suffering from severe mental illness (N = 371) | Lifestyle intervention focusing on cardio metabolic health |

Waist circumference Body mass index Metabolic syndrome z-score |

Waist circumference decreased 1.51 cm in the intervention group versus control group after 3 months and metabolic syndrome z-score decreased 0.22. After 12 months, the decrease in waist circumference was no longer significant | Promising first results |

| Hjorth et al. (2016) |

Cluster RCT Duration: 12 months |

Longterm psychiatric treatment facilities | Staff members serving as role models for severely and chronically mental ill patients (N = 174) | Health promotion intervention for staff as role modelling for patients |

Waist circumference BMI Weight Lung PEEP Blood pressure Physical fitness Tobacco and alcohol consumption Quality of life |

No effects found on client level There was a relation in: Staff and patient change in quality of life |

No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| Hutchison et al. (2016) |

Pre-post study Duration: 12 months |

Long term residential mental health care facility | Persons suffering from with severe mental illness (N = 43) |

In SHAPE program, a health promotion program aiming at physical activity and healthy diet, using assessment, fitness plan, weekly meetings education, incentives, and group motivational celebrations |

Physical activity Physical health Recovery Severity of depression Self-perceived ability to implement health-promoting behaviors Hopefulness |

100% expressed a nutrition and exercise goal, and weekly logs were filled in by the majority Physical activity, health has increased Recovery and depression improved significantly Self-perceived ability improved for wellbeing and exercise |

Promising first results |

| Gill et al. (2016) |

Pilot: Single group pre-post design Duration: 8 weeks |

Supported housing programs and ACT program | Adults with serious mental illnesses (N = 77) |

Wellness for life inter-professional health promotion intervention Including: Exercise, nutritional counselling, health literacy education, and peer wellness coaching |

Blood pressure Blood glucose Waist circumference Body weight Physical strength and flexibility BMI Readiness to change Health status |

Average blood pressure and waist circumference decreased Strength and flexibility improved Readiness for diet and exercise improved |

Promising first results |

| Loh et al. (2016) |

Pilot RCT Duration: 3 months |

Long stay ward | Patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 104) | Structured walking intervention | Health related quality of life | Positive effect on quality of life, wellbeing and psychiatric symptoms | Promising first results |

| Cabassa et al. (2015) |

RCT Duration: 18 months |

Supportive housing | 300 planned | Peer-led healthy lifestyle program |

Weight Quality of life Recovery |

Protocol | No results yet |

| Oertel-Knochel et al. (2014) |

Matched pre-post design Duration: 1 week before and 1 week after the intervention |

Long-term patients suffering from a major depression or schizophrenia (N = 51) |

Exercise group: Cognitive training + aerobic exercise Relaxation group: Cognitive training + relaxation 12 sessions in for weeks |

Cognitive performance Symptoms Wellbeing |

Increase in cognitive performance in the domains visual learning, working memory and speed of processing, a decrease in state anxiety and an increase in subjective quality of life between pre- and post-testing | Promising first results | |

| Verhaeghe et al. (2013) |

Cluster preference RCT Duration: 6 months |

Sheltered housing organisations | Adults with mental disorders (N = 324) |

Health promotion program aiming at physical activity and healthy eating |

Body weight BMI Waist circumference Fat mass Health-related quality of life Psychiatric symptom severity |

Significant results on body weight, BMI, waist circumference, fat mass, however disappeared during follow up except for fat mass | Promising first results |

| Forsberg et al. (2010) |

Cluster RCT Duration: 12 months |

8 Supported housing facilities and 2 housing support programmes | Persons with severe mental illness (N = 41) | 12 month Lifestyle intervention program |

Quality of life Functioning Psychiatric symptoms |

No difference found between the study groups | No evidence for effectiveness yet |

| Spiritual and creative | |||||||

| Berry et al. (2016) |

Cluster RCT Duration: 6 months |

Psychiatric rehabilitation wards |

Patients with complex mental health needs (N = 51 patients and 85 staff) |

24 one-hour sessions focussing on staff-patients relationships per ward over 6 months |

Staff and patient relationships Staff wellbeing Patient functioning |

Significant less depersonalization in staff Less feeling of criticism by patients and improvement of ward organization and relationships by patients |

Added value |

| Ho et al. (2014) |

3-arm RCT Duration: 24 weeks |

Residential rehabilitation complex | Patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (N = 153) | Tai chi |

Symptom management Motor coordination Memory Daily living function Stress levels |

Protocol | No results yet |

| Gold et al. (2013) |

Pragmatic parallel trial Duration: 9 months |

Specialised mental health care settings | Adults with severe mental disorders (N = 144) | 3 months biweekly individual resource-oriented music therapy |

Negative symptoms General symptoms Motivation for change Self-efficacy Self-esteem Social relationships |

Effect on negative symptoms, functioning, clinical global impressions, social avoidance through music, and vitality | Added value |

| Kwon et al. (2013) |

Quasi-experimental pretest–posttest design Duration: 7 weeks |

Mental health rehabilitation complex | Adults with severe mental disorders (N = 55) | 7 week group music therapy | Brain wave, cognitive function, behavior | Effect on alpha waves revealing that the participants in the music therapy may have experienced more joyful emotions throughout the sessions. The experimental group also showed improved cognitive function and positive behavior (social competence, social interest & personal neatness) while their negative behaviors was significantly less | Promising first results |

| Ho et al. (2012) |

Pilot RCT Duration: 12 weeks |

Mental health rehabilitation complex | Patients with chronic schizophrenia (N = 30) | Tai chi (6 weeks) |

Movement coordination Negative symptoms Disability |

Effect on movement coordination and interpersonal functioning. Fewer disruptions to life activities at 6 weeks after the intervention | Promising first results |

| Gelkopf et al. (2006) |

Cluster randomized trial Duration: 3 months |

Psychiatric hospital | Patients with chronic schizophrenia (N = 29) |

Humorous movies Daily for 3 months |

Positive and negative symptoms Anxiety Depression Anger Social functioning Treatment insight Therapeutic alliance |

Significant larger difference over time in reduction of negative symptoms, depression and anxiety than in control group The intervention group showed a significant larger improvement in time than the control group on the social functioning scale |

Added value |

| Hayashi et al. (2002) |

Non randomized, controlled study Duration: 4 months |

Long stay wards of mental health care institute | Female patients with chronic psychoses (N = 66) |

Group musical therapy Including, listening to and making music and group communication about it |

Psychotic symptoms Objective quality of life Subjective musical experiences Ward activity and—adjustment |

A significant advantage was found of the intervention for psychotic symptoms, quality of life, musical experience, and ward activity over time during the intervention Effects did not last at follow up |

Promising first results |

Societal Recovery

This category contains the greatest number of studies (n = 22). These studies focussed on diverse interventions. Nine evaluated interventions aimed at general goal achievement, seven at achieving specific and/or disability management and two at vocational rehabilitation. One study concerned a staff-training program designed to increase patients’ engagement.

Of the nine studies that evaluated interventions aimed at goal attainment, seven interventions were totally or partly based on the ‘choose-get-keep’ model (Anthony et al. 2014; Ellison et al. 2011; Fagan-Pryor et al. 2009; Magliano et al. 2016; Pioli et al. 2006; Sanches et al. 2015; Vandevooren et al. 2007). Three of the goal attainment studies were RCTs, and four were uncontrolled/pre-post design. Five of these studies showed (small) positive results (Ellison et al. 2011; Fagan-Pryor et al. 2009; Magliano et al. 2016; Pioli et al. 2006; Vandevooren et al. 2007), among others, concerning functioning and residential status. Bitter et al. (2017) evaluated, by means of a cluster randomized trial, CARe: A rehabilitation approach based on the strengths model and personal recovery in teams of supported accommodation, but did not find any differences in outcomes between the clients of trained and untrained teams.

Of the studies on interventions concerning skills and illness/disability management, two RCT studies evaluated the illness management and recovery (IMR) approach (Beentjes et al. 2018; Levitt et al. 2009). The Levitt study reported significant improvements in illness management, symptoms and psychosocial functioning, while the Beentjes’ e-IMR study did not due to low implementation rates. Lindström et al. (2012) conducted a study on a home-based occupational therapy intervention aiming at daily occupations including remediation and compensatory strategies. The authors observed positive significant results on most outcomes (goal attainment, social interaction, satisfaction with daily occupations, activities of daily living (ADL) and psychiatric symptoms). Anzai et al. (2002) examined an RCT on an training program for illness management skills based on Liberman’s community re-entry module, resulting in positive effects including knowledge and skills and community participation. In a small, pre-post study on a short educational training course on using the internet and touch screen, no effects were found on social isolation, self-esteem and internet use (Loi et al. 2016). Three studies (Park and Han 2018; Seo et al. 2007; Tsang and Pearson 2001) examined societal recovery explicitly focussed on social skills. Tsang and Pearson (2001) evaluated social skills training in the context of vocational rehabilitation. This cluster randomized pilot found positive results for work-related social skills, motivation to seek employment and success in job search. Seo et al. (2007) conducted a quasi-experimental study on social skills group training that included conservational and assertiveness skills based on the Liberman modules. The results showed a difference in improvement of social skills and self-esteem in favour of the intervention group. Park and Han (2018) studied with a quasi-experimental design a 5-week communication program based on communication theory of Walsh and existing of ten sessions. They found improved communication, and relational skills, but no improvement in problem solving, though used an alpha of 0.70.

Two studies evaluated interventions aimed at vocational rehabilitation. Oka et al. (2004) evaluated a hybrid occupational therapy and supported employment intervention by means of a retrospective study. Positive results were achieved concerning social functioning and hospitalisation. Rogers et al. (2006) evaluated the choose-get-keep approach in a vocational context compared with enhanced state vocational rehabilitation and found no differences between the groups. A positive effect on vocational status was found for both interventions, indicating that a rehabilitation approach aiming at work can be effective for this group.

Finally, the remaining studies were concerned with client engagement in activities (Killaspy et al. 2015; Sheridan et al. 2018) and psychoeducation based on cognitive behavioral therapy (McMurran et al. 2011). Killaspy et al. (2015) evaluated a staff-training program designed to increase patients’ engagement in activities. In this cluster-randomized trial, no differences were found between the study groups in engagement in activities. Sheridan et al. (2018) studied the effects of a supported socialisation volunteer partner group to stimulate social and leisure activities. In their qualitative thematic analyses of diary data they found indications for positive effects on involvement in normalising life, connectedness, physical health, social capacity and culture engagement. McMurran et al. (2011) published on a protocol to evaluate a 12-session group intervention aimed at problem solving.

Personal Recovery

The six studies in this category evaluated interventions aimed at personal recovery (including outcomes on empowerment, hope, confidence, and quality of life or comparable). All studies showed added value or promising first results. Of these studies, one was an RCT and five were semi-controlled or pre-post designs. Two studies were peer-run interventions. One of these peer-run interventions examined confidence and care needs (Boevink et al. 2016) and the other on consumers’ perception of the recovery attitudes on the staff (Mancini et al. 2013).

One study focussed especially on elderly patients and showed a small but positive result concerning life satisfaction (Willemse et al. 2009). Park and Sung (2013) reported results of a study on a 6-week, recovery-oriented nursing intervention. This study also showed positive results on helplessness and recovery, but due to the non-controlled design, these results need further confirmation in replication studies. There were two studies on therapies to enhance personal recovery (Nowak et al. 2018; Randal et al. 2003). Randal et al. (2003) conducted a small, matched-control evaluation study on individual recovery-focused multimodal therapy. Following Evans’ design hierarchy, the results can be interpreted as promising with outcomes showing significantly more improvement of positive and negative symptoms and a decrease of deviant behavior, e.g. verbal aggression and violence. Nowak et al. did a pre-post study on a recovery-oriented cognitive behavioral workshop of 6 weeks. They found no significant change in total recovery, but they did find significant improvements in sub scales including confidence, hope and psycho social functioning.

Functional Recovery

This category included five studies evaluating interventions focused on improvement of cognitive and executive functions. Four were RCTs, and one had a pre-post design. A study on an integrative program that focused on all basic cognitive functions showed positive results concerning vocational outcomes, family contact and social competence (Sánchez et al. 2013). Lindenmayer et al. (2012) conducted an RCT on an intervention that combined cognitive remediation with social cognition training. The combined intervention resulted in greater improvements in emotion recognition, emotion discrimination, social functioning and neuro-cognition compared with cognitive remediation alone. Another study resulting in interesting results was a cognitive remediation intervention focusing on problem solving skills (Medalia et al. 2001). This study found a significant difference for independent living. Schutt et al. (2017) executed a small pre-post study on a cognitive remediation intervention, but did not find relevant outcomes. Stiekema et al. (2015) published on their protocol to evaluate a cognitive adaptation training (CAT).

Healthy Lifestyle

We found thirteen studies focusing on lifestyle interventions; all were published after 2010. Seven were RCTs, five were semi-controlled or pre-post studies and one was qualitative. Seven of these studies showed promising first results, four did not show evidence and two were protocol papers. Loh et al. (2016) executed a (pilot) RCT on a structured walking intervention. In this study, the participants of the control group scored slightly better on quality of life, psychiatric symptoms, physical role limitations and physical functioning after 3 months. Hjorth et al. (2016) evaluated an intervention program for improving physical health in staff and its impact on patient’s health. The intervention had a positive effect on the waist circumference and blood pressure for the staff, and there was a statistically significant association between the staff change in each facility and the patients’ change in health parameters.

Looijmans et al. (2017) conducted a cluster RCT on lifestyle intervention that focused on cardio metabolic health. This intervention led to positive results after 3 months on waist circumstance and metabolic syndrome. The same research group studied the use of a web-based tool (Looijmans et al. 2019) in FACT teams and sheltered living teams. Findings indicate no significant improvements on the primary and secondary outcomes and an improvement on the readiness to change. Oertel-Knöchel et al. (2014) conducted a combined cognitive–aerobic/relaxation intervention showing that physical exercise is a valuable addition to cognitive training. Verhaeghe et al. (2013), Cabassa et al. (2015), Forsberg et al. (2010) and O’Hara et al. (2017) also all studied a lifestyle program. Verhaeghe et al. conducted a cluster RCT on a comprehensive lifestyle intervention (psycho-education, supervised exercise and individual support) in sheltered housing services. Although initially small positive results were achieved on weight, body mass index (BMI) and waist circumstances, these results almost all disappeared during follow-up. No differences were found regarding secondary outcomes (i.e., symptoms and quality of life). Cabassa et al. published a study protocol. Forsberg et al. did not find support for the added value. O’Hara et al. studied the results of a peer based group and did this qualitatively, using focus groups and field notes, and added this with structured interviews. The results indicate participants attended on average three quarter of the sessions and perceived them as helpful and satisfactory. Ringen et al. (2018), Hutchison et al. (2016) and Gill et al. (2016) all executed pre-post evaluations on a promotion / motivational program, of which the first did not show improvements and the latter two resulted in positive results on physical activity and physical health. Sweeney and Baker, finally, published two protocol papers on an intervention in which existing peer workers tailor clients to appropriate smoking quitline service (Sweeney et al. 2019).

Spiritual and Creative Therapy

This category contained seven studies. Two studies (one protocol) evaluated Tai chi (Ho et al. 2012, 2014) of which a pilot RCT showed promising results concerning movement and interpersonal functioning. Three studies (Gold et al. 2013; Hayashi et al. 2002; Kwon et al. 2013) evaluated a form of music therapy. In all studies, positive results were achieved concerning amount others: Negative symptoms (Gold et al. 2013), cognitive function (Hayashi et al. 2002), positive behavior (Kwon et al. 2013), and quality of life (Hayashi et al. 2002). These positive results, however, did not last through the last follow-up.

One study in this category evaluated the effect of watching humorous movies. Watching these movies regularly for 3 months appeared to have a small positive effect on negative symptoms, depression and anxiety, and social competence (Gelkopf et al. 2006). The seventh study was a cluster trial on a ward intervention to improve patient-staff relationships and wellbeing leading to significant differences in depersonalization in staff and criticism experienced by clients (Berry et al. 2016).

Discussion

With this study, we aimed to achieve insight into which psychosocial interventions are available to support recovery in other dimensions than the clinical one and evaluated in people with SMI who live in supported accommodations. Additionally, we explored what scientific knowledge is available about the outcomes of these interventions. We found 53 studies with different types of interventions aiming at several non-clinical dimensions of recovery. Almost a quarter (22.6%) of these interventions showed added value and almost half of them (47.2%) first promising results. This is a hopeful result that shows that improvement on recovery is possible, even for people with SMI living in supported accommodations which are, as shown in the introduction, often dealing with long-term and complex needs. The articles included in this study provide knowledge concerning the current use of psychosocial interventions in supported accommodations and give us new insights in the opportunities for implementation, further development and evaluation of interventions.

These findings indicate that there have been some practice and research attention for the other dimensions of recovery for the group of people who need supported accommodation in the last 20 years. Interventions aimed at societal recovery have the longest tradition in general mental healthcare, which is reflected in the larger number of papers found for the group living in supported accommodations and their publication date as well. Of these, most interventions were based on the Boston choose-get-keep rehabilitation approach which showed inconsistent results, some no added value, some promising results. Further study needs to bring answers to when, for whom and why these interventions do or do not work. Realist evaluations are the most suiting design for this (Wong et al. 2016). Interventions showing the most consistent added value included IMR and social and self-management skills trainings and are therefore relevant to follow and replicate.

Additionally, we found small amounts of papers concerning the two other known recovery dimensions: personal and functional recovery. Developments which are relevant to follow and replicate if we truly want the whole group with SMI to profit from the paradigm shift in mental health care towards a broader definition of recovery in which more recognition exists for the personal experience of people with mental illnesses (Leamy et al. 2011). On personal recovery, markedly, all six interventions found had added value or promising results. Noteworthy are the two interventions with added value: the TREE peer-to-peer intervention and the empowerment program provided by nurses. Of the five functional recovery interventions, three showed added value, which all included cognitive remediation interventions. Cognitive adaptation training have not been studied frequently, but is one to follow: it is in concept easy to implement and if effective, a large contribution to independent functioning can be expected. Interventions on the functional recovery dimension are especially relevant when considering that cognitive dysfunction and related negative symptoms can be strong obstructing factors in the life of people with severe mental health problems (Quee et al. 2014; Stiekema et al. 2016).

Additional to the known recovery dimensions, we found a relatively large number of studies on healthy lifestyle (13) and on the spiritual and creative domain (7). Healthy lifestyle is a relevant life area as a substantial number of people suffering from a severe mental illness are affected by comorbid medical conditions which influence their life expectancy, quality of life and recovery on other dimensions (Scott and Happell 2011). No interventions showed added value, but half of them were promising. Noteworthy is that most of the health promotion interventions, all including exercise and some a healthy diet as well, showed promising results. Interesting was the structured walking intervention showing promising results, which seems an easy to implement intervention with large impact. Five interventions: the peer led, smoking, web-based, and the two health promotion/motivational interventions by staff did not show added value. The results indicate that concrete lifestyle programs might add more to the results.

In the spiritual and creative intervention category three music therapies were studied of which, noteworthy, one showed added value and two promising results. Tai chi was twice studied as intervention: one showing no results and one promising results. Markedly, humorous movie watching as intervention showed added value. This finding relates to current insights: cultural interventions have high potential for health gains as was recently underlined in a scoping review of the WHO (Fancourt and Finn 2019).

This broader scope and promising results are hopeful developments especially as people with severe mental illness experience several unmet needs (Bitter et al. 2016; de Heer-Wunderink 2012; Wiersma 2006). However, compared with the ambulatory treated people with mental illness, the number of studies we found on recovery can still be considered relatively low (van Weeghel et al. 2019b). This is not surprising because since the start of deinstitutionalisation in the second half of the twentieth century, the focus of practice, research and policy increasingly shifted towards the development of ambulant and community-oriented services (Burns and Firn 2017). Although this was an important development in mental health care, which led to the increasing opportunity for people with SMI to participate in society, the risk exists that a knowledge gap emerges concerning the group in need supported accommodation (McPherson et al. 2018). It is therefore important that more studies focus on this group to gain more insight in what these people need in their recovery and to develop interventions that match their needs.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

This study has several strengths and limitations. A strength was the broad scope. Our aim was to provide an impression of psychosocial interventions that exist for people with SMI who need supported accommodation and to provide first insights into what is known about the effectiveness of these interventions. Therefore, we used a broad search strategy and included a variety of interventions aiming at a broad range of outcomes and executed in different settings and (international) contexts, and included all types of study designs. When developments in the recovery field are a bit further along, a quantitative synthesis would add to our knowledge. At this point the number of studies in the supported accommodation field is too small yet to perform a quantitative review (Chilvers et al. 2006; McPherson et al. 2018). A point of attention is that we used information provided in the included articles only, which sometimes was somewhat poor, for example not all papers published effect sizes. So, it might be that the quality of some papers is displayed more positively if it was based on the p values only. Another note is that when performing a review, a selection of specific search terms is chosen. There is always a risk that not all relevant papers end up in the results due to word use in titles, abstracts and key words. When reading this and other reviews, this should be kept in mind. Nevertheless, this study provides a broad overview of interventions on several dimensions of recovery besides the clinical one that can give supported accommodation an impression of interventions that may be relevant and sufficient to implement, and bring the recovery forward, even in people that cope with severe, and therefore often complex and long-term, mental illnesses.

Suggestions for Development of Practice and Research

Research specifically focussing on the recovery dimensions besides clinical recovery of people with severe mental illness who live in supported accommodations remains limited but seems to be in development. We also can conclude that a broader vision towards recovery in these settings has gained attention and that, regarding all other dimensions of recovery, hopeful results have been achieved so far.

Four challenges can be appointed concerning the practice and research of interventions for people with severe mental illness who live in supported accommodations. The first challenge is the further development and professionalization of recovery-oriented care and support offered for this specific group of people. Effective and promising interventions should be developed and made available for all people with severe mental illness, despite their place in the care landscape (Couwenbergh and van Weeghel 2014).

The second challenge is to accompany developments in practice with research to gain more insight into what works, for whom and what does not, so that the provided care can be more personalized. Specific knowledge is needed concerning the group of people who are in need of supported accommodation. For example, we were surprised that for some well-known recovery interventions, for example, the wellness recovery action plan (WRAP) (Fukui et al. 2011) or narrative enhancement and cognitive therapy (NECT) (Fukui et al. 2011), no studies were found explicitly focussing on people living in supported accommodation. Here may lay a chance for further development, as it is worthwhile to study interventions that have proved themselves in ambulant contexts to see if they also can help clients with more complex and supported living needs.

The third challenge is the integration of different approaches towards recovery. In several countries, different forms of support are fragmentized (Boevink et al. 2016). For example, in the Netherlands a separation exists between clinical mental health care services and supported accommodation services. The insight is growing that integration of different aspects of recovery may lead to better outcomes (Corrigan et al. 2012). This might lead to improvement of recovery orientation of the care for people living in supported accommodation. Altogether, it is recommended that supported accommodation services reconsider their scope and position in the care landscape and consider broadening and strengthening their recovery-oriented services, as well as stronger collaborations between stakeholders including mental health treatment providers, supported housing organisations and local organizations for community support.

The fourth challenge is the professionals’ interest, knowledge and implementation skills to adapt and use state-of-the-art interventions. Working evidence based asks for an innovative mind set as well as time and support in keeping up-to-date and using new interventions that were proven effective in research.

Funding

The funding was provided by Five supported housing organisations and Storm Rehabilitation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Neis Bitter, Email: n.bitter@rivierduinen.nl.

Diana Roeg, Email: d.p.k.roeg@tilburguniversity.edu.

Chijs van Nieuwenhuizen, Email: ch.vannieuwenhuizen@tilburguniversity.edu.

Jaap van Weeghel, Email: j.vanweeghel@tilburguniversity.edu.

References

- Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;16(4):11. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA, Cohen MR, Farkas M, Gagne C. Psychiatric rehabilitation. 2. Boston: Boston University, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA, Ellison ML, Rogers ES, Mizock L, Lyass A. Implementing and evaluating goal setting in a statewide psychiatric rehabilitation program. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 2014;57(4):228–237. [Google Scholar]

- Anzai N, Yoneda S, Kumagai N, Nakamura Y, Ikebuchi E, Liberman RP. Rehab rounds: Training persons with schizophrenia in illness self-management: A randomized controlled trial in Japan. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(5):545–547. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.5.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Beentjes TAA, Goossens PJJ, Vermeulen H, Teerenstra S, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MWG, van Gaal BGI. E-IMR: E-health added to face-to-face delivery of Illness Management & Recovery programme for people with severe mental illness, an exploratory clustered randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):962. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3767-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry K, Haddock G, Kellett S, Roberts C, Drake R, Barrowclough C. Feasibility of a ward-based psychological intervention to improve staff and patient relationships in psychiatric rehabilitation settings. British Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2016;55(3):236–252. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitter NA, Roeg DPK, van Nieuwenhuizen Ch, van Weeghel J. Identifying profiles of service users in housing services and exploring their quality of life and care needs. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):419. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1122-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitter NA, Roeg DPK, van Assen MALM, van Nieuwenhuizen Ch, van Weeghel J. How effective is the comprehensive approach to rehabilitation (CARe) methodology? A cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):396. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1565-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boevink W, Kroon H, van Vugt M, Delespaul P, van Os J. A user-developed, user run recovery programme for people with severe mental illness: A randomised control trial. Psychosis. 2016;8(4):287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Firn M. Outreach in community mental health care: A manual for practitioners. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Catty J, Becker T, Drake RE, Fioritti A, Knapp M, Van Busschbach JT. The effectiveness of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2007;370(9593):1146–1152. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61516-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Stefancic A, O’Hara K, El-Bassel N, Lewis-Fernández R, Luchsinger JA, Palinkas LA. Peer-led healthy lifestyle program in supportive housing: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:388. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0902-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers, R., Macdonald, G. M., & Hayes, A. A. (2006). Supported housing for people with severe mental disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, CD000453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Corrigan PW, Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, Solomon P. Principles and practice of psychiatric rehabilitation: An empirical approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Couwenbergh, C., & van Weeghel, J. (2014). Crossing the bridge: National action plan to improve care of severe mental illness. Phrenos, Center of expertise in Utrecht.

- Davidson L, Borg M, Marin I, Topor A, Mezzina R, Sells D. Processes of recovery in serious mental illness: Findings from a multinational study. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2005;8(3):177–201. [Google Scholar]

- de Heer-Wunderink, C. (2012). Successful community living: A 'Utopia'? A survey of people with severe mental illness in Dutch Regional Institutes for Residential Care. Groningen.

- de Heer-Wunderink C, Visser E, Caro-Nienhuis A, Sytema S, Wiersma D. Supported housing and supported independent living in the Netherlands, with a comparison with England. Community Mental Health Journal. 2012;48(3):321–327. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9381-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Heer-Wunderink C, Visser E, Sytema S, Wiersma D. Social inclusion of people with severe mental illness living in community housing programs. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(11):1102–1107. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison ML, Rogers ES, Lyass A, Massaro J, Wewiorski NJ, Hsu ST, Anthony WA. Statewide initiative of intensive psychiatric rehabilitation: Outcomes and relationship to other mental health service use. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2011;35(1):9. doi: 10.2975/35.1.2011.9.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. Hierarchy of evidence: A framework for ranking evidence evaluating healthcare interventions. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2003;12(1):77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan-Pryor EC, Haber LC, Harlan D, Rumple S. The impact of a recovery-based program on veterans with long inpatient psychiatric stays. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30(6):372–376. doi: 10.1080/01612840802488640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329834/9789289054553-eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- Farkas M, Anthony WA. Psychiatric rehabilitation interventions: A review. International Review of Psychiatry. 2010;22(2):114–129. doi: 10.3109/09540261003730372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg KA, Björkman T, Sandman PO, Sandlund M. Influence of a lifestyle intervention among persons with a psychiatric disability: A cluster randomised controlled trail on symptoms, quality of life and sense of coherence. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(11–12):1519–1528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, Horan L. Individual perspectives on the Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) as an intervention in mental health care. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. 2016;20(2):110–125. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui S, Starnino VR, Susana M, Davidson LJ, Cook K, Rapp CA, Gowdy EA. Effect of Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) participation on psychiatric symptoms, sense of hope, and recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2011;34(3):2014. doi: 10.2975/34.3.2011.214.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelkopf M, Gonen B, Kurs R, Melamed Y, Bleich A. The effect of humorous movies on inpatients with chronic schizophrenia. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194(11):880–883. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243811.29997.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill KJ, Zechner M, Zambo Anderson E, Swarbrick M, Murphy A. Wellness for life: A pilot of an interprofessional intervention to address metabolic syndrome in adults with serious mental illnesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2016;39(2):147. doi: 10.1037/prj0000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold C, Mössler K, Grocke D, Heldal TO, Tjemsland L, Aarre T, Assmus J. Individual music therapy for mental health care clients with low therapy motivation: Multicentre randomised controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2013;82(5):319–331. doi: 10.1159/000348452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JP, Østergaard B, Nordentoft M, Hounsgaard L. Cognitive adaptation training combined with assertive community treatment: A randomised longitudinal trial. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;135(1):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi N, Tanabe Y, Nakagawa S, Noguchi M, Iwata C, Koubuchi Y, Sugita K. Effects of group musical therapy on inpatients with chronic psychoses: A controlled study. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2002;56(2):187–193. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2002.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth P, Davidsen A, Kilian R, Jensen SOW, Munk-Jørgensen P. Intervention to promote physical health in staff within mental health facilities and the impact on patients’ physical health. Nordic Journal of Pyschiatry. 2016;70(1):62–71. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2015.1050452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho RTH, Au Yeung FS, Lo PH, Law KY, Wong KO, Cheung IK, Ng SM. Tai-chi for residential patients with schizophrenia on movement coordination, negative symptoms, and functioning: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/923925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho RTH, Wan AHY, Au-Yeung FSW, Lo PHY, Siu PJCY, Wong CPK, Chan CLW. The psychophysiological effects of tai-chi and exercise in residential schizophrenic patients: A 3-arm randomized controlled trial. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014;14(1):364. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison SL, Terhorst L, Murtaugh S, Gross S, Kogan JN, Shaffer SL. Effectiveness of a staff promoted wellness program to improve health in residents of a mental health long-term care facility. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2016;37(4):257–264. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1126774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim N, Michail M, Callaghan P. The strengths based approach as a service delivery model for severe mental illness: A meta-analysis of clinical trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):243. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0243-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keet R, de Vetten-Mc Mahon M, Shields-Zeeman L, Ruud T, van Weeghel J, Mulder CL, Pieters G. Recovery for all in the community; position paper on principles and key elements of community-based mental health care. BMC Psychiatry. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2162-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killaspy H. Supported accommodation for people with mental health problems. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(1):74–75. doi: 10.1002/wps.20278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killaspy H, Marston L, Green N, Harrison I, Lean M, Cook S, Leavey G. Clinical effectiveness of a staff training intervention in mental health inpatient rehabilitation units designed to increase patients' engagement in activities (the Rehabilitation Effectiveness for Activities for Life [REAL] study): Single-blind, cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(1):38–48. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killaspy H, Marston L, Green N, Harrison I, Lean M, Holloway F, Koeser L. Clinical outcomes and costs for people with complex psychosis; a naturalistic prospective cohort study of mental health rehabilitation service users in England. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0797-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M, Gang M, Oh K. Effect of the group music therapy on brain wave, behavior, and cognitive function among patients with chronic schizophrenia. Asian Nursing Research. 2013;7(4):168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):445–452. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff HS, Chow CM, Pepin R, Conley J, Ph B, Allen IE, Seaman CA. Does one size fit all? What we can and can't learn from a meta-analysis of housing models for persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2015;60(4):473–482. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt AJ, Mueser KT, DeGenova J, Lorenzo J, Bradford-Watt D, Barbosa A, Chernick M. Randomized controlled trial of illness management and recovery in multiple-unit supportive housing. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(12):1629–1636. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.12.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, Gutkind D. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14(4):256–272. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer J-P, McGurk SR, Khan A, Kaushik S, Thanju A, Hoffman L, Herrmann E. Improving social cognition in schizophrenia: A pilot intervention combining computerized social cognition training with cognitive remediation. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;39(3):507–517. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindström M, Hariz GM, Bernspång B. Dealing with real-life challenges: Outcome of a home-based occupational therapy intervention for people with severe psychiatric disability. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2012;32(2):5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Evans B, Mayo-Wilson E, Harrison B, Istead H, Brown E, Pilling S, Kendall T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):39. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh SY, Abdullah A, Bakar AKA, Thambu M, Jaafar NRN. Structured walking and chronic institutionalized schizophrenia inmates: A pilot rct study on quality of life. Global Journal of Health Science. 2016;8(1):238. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n1p238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loi SM, Hodson S, Huppert D, Swan J, Mazur A, Lautenschlager NT. Can a short internet training program improve social isolation and self-esteem in older adults with psychiatric conditions? International Psychogeriatrics. 2016;28(10):1737–1740. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looijmans A, Stiekema APM, Bruggeman R, Van der Meer L, Stolk RP, Schoevers RA, Corpelijn E. Changing the obesogenic environment to improve cardiometabolic helath in residential patients with a severe mental illness: Cluster randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;211(5):296–303. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.117.199315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looijmans A, Jörg F, Bruggeman R, Schoevers RA, Corpeleijn E. Multimodal lifestyle intervention using a web-based tool to improve cardiometabolic health in patients with serious mental illness: Results of a cluster randomized controlled trial (LION) BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):339. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]