Abstract

There is a growing body of evidence that endophytic fungal metabolites possess important biological activities. Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers., a well-known grass species with potential medicinal properties, is under-explored for the diversity of endophytic fungal species and their metabolites. We report here the diversity of endophytic fungi in the culm, leaf and inflorescence of Cynodon dactylon when cultured on moist blotter (MB), potato dextrose agar (PDA) and malt extract agar (MEA). Species richness, Shannon and Simpson diversity and evenness indices showed that PDA followed by MEA supported the growth of the largest number of fungal species. Amongst four fungal species tested, Curvularia tsudae was selected for further studies on antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. The mycelial mat (MM) and culture filtrate (CF) of PD broth grown Curvularia tsudae extracted with ethyl acetate and methanol, respectively, were subjected to antimicrobial assay against five bacterial and four fungal test isolates. Results indicated that the ethyl acetate extract of CF had moderate activity against Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas fluorescence and Staphylococcus aureus whereas the methanolic MM extract showed high to moderate activity to Aspergillus flavus, A. niger and Fusarium oxysporum. Cyclic voltammetric analysis of ethyl acetate extract showed very good antioxidant activity and the extract contained coumarins when determined by HPLC. High-resolution orbitrap LC–MS of ethyl acetate extract revealed the presence of metabolites with antimicrobial and antioxidant and other biological activities. Finding of the present study suggested that Curvularia tsudae could be exploited for pharmaceutical applications.

Keywords: Antimicrobial activity, Cyclic voltammetry, Diversity and evenness, HPLC, OHR LC–MS

Introduction

Endophytic fungi reside in plant tissues without causing any symptoms of the disease (Petrini 1987). Endophytic fungi are known for their bioactive metabolites with proven pharmaceutical and industrial applications (Strobel 2003; Daisy 2003; Porras-Alfaro and Bayaman 2011) and abilities to protect host plants against abiotic and biotic stresses (Schardl 1997; Sampangi- Ramaiah et al. 2020), besides promoting plant growth (Gonda et al. 2010; Rekha and Shivanna 2014). Since, several hundred endophytic fungal species could be isolated from a single plant (Tan and Zou 2001), there has been heightened curiosity in researchers to investigate the potential bioactive metabolites with applications in human welfare.

Cynodon dactylon (Bermuda grass) of Poaceae, a traditional medicinal plant, is well documented for antimicrobial, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, diuretic, anti-emetic (Dhar et al. 1968; Ahmed et al. 1994; Liu et al. 2004; Rekha and Shivanna 2014) and antidiabetic properties and treating dysentery, dropsy and secondary syphilis (Kirtikar and Basu 1980; Chopra and Handa 1982). Given the above immense potential, C. dactylon was chosen for detailing the endophytic fungal diversity. Besides this, few resident endophytic fungal species were tested for the antimicrobial activity in their metabolites against clinical microorganisms and also for determining the electrochemical potential of metabolites in support of the prevalence of antioxidant activity. The endophytic fungal mycochemical composition of metabolites was also determined. The prominent chemical constituents present in the endophytic fungal extracts were determined by HPLC and OHR LC–MS. The present study is an attempt to search for novel compounds of endophytic fungal origin with antimicrobial, antioxidant and other biological activities.

Materials and methods

Selection of the study site and grass species

Three study sites, each with three plants, located (13°44ʹ6″N and 75°35′52″E) in Singanamane region in Bhadravathi taluk of Karnataka, with C. dactylon growing abundantly in the region were chosen for the study. This region consists of red loam soil and receives an annual rainfall of 1123 mm and experiences a temperature of 23–25 °C. Characterization of Cynodon dactylon was based on the morphological characteristics (Bhat and Nagendran 2001; Vasanthakumari et al. 2010) and identity and approval of grass species were also done by comparison with the herbarium specimens in the Department of studies in Applied Botany, Kuvempu University.

Isolation and characterization of endophytic fungal species from grass species

Cynodon dactylon plants at flowering (Mar-Aug) were randomly selected and tagged, and inflorescence, culm and leaf samples were collected in moistened and sterilized polypropylene covers and processed in the laboratory within 24 h. The plant samples were washed in running tap water and surface-disinfected (Achar and Shivanna 2013). Samples were cut into 1-cm-long segments in aseptic condition and incubated on moist blotter (MB) method (Shivanna and Vasanthakumari 2011) and on potato dextrose or malt extract agar (PDA and MEA, Himedia Laboratories, Mumbai) media unamended or amended with chloramphenicol (100 mg L−1) and incubated under 12/12 h light/nUV light (350–400 nm) regime at 23 ± 2 °C for 5–7 days (Achar and Shivanna 2013). The fungal species expressing on the incubated segments were identified based on morpho-characteristics of fruiting bodies and spores (Barnett 1972; Ellis 1976; Subramanian 1983; Rao and Manoharachary 1990). The identity of endophytic fungal species was confirmed by comparing with specimen characteristics detailed in Index Fungorum (www.indexfungorum.org).

A fungal endophyte C. tsudae with high antimicrobial activity (based on the preliminary study) was selected for molecular characterization. The ITS regions of DNA of the candidate fungal species were selected for characterization by Cetyl trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Wu et al. 2001). The DNA was isolated and amplified out by using the Eppendorf Nexus gradient polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machine. The 25 μl reaction mixture (2.5 μl of 10 × PCR buffer, 16.8 μl of PCR H2O, 1 μl of 200 m MNTP, 0.2 μl of Taq polymerase) was added to 1 μl of each primer (ITS1: 5′– TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGC-3′ and ITS4: 5′– TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) and 2.5 μl of fungal DNA (Teuber et al. 2017). The DNA database was sequenced by Sanger sequencing and the assembled sequence data was submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene bank to obtain the accession number. Based on the DNA sequence homology, the fungal species were identified. The nucleotide sequences of isolates of the present study and selected reference strains from different hosts obtained from the NCBI database were compared for their relatedness and grouped into distinct clades by the neighbor-joining method (MEGA 7.0, Friedrich et al. 2005).

Preparation of crude extract of endophytic fungi

Endophytic fungal species like Aspergillus flavus, Cladosporium cladosporioides, Curvularia tsudae and Penicillium citrinum documented in C. dactylon in the suggested study were preferred for determining the presence of antimicrobial activity in the culture filtrate (CF) and mycelial mat (MM) extracts. Isolates were initially cultured on PDA and incubated as described previously. The culture discs (5-mm-dia.) of the above isolates from the actively growing margin on PDA were inoculated separately into PD broth (300 ml, pH 5.6) contained in Erlenmeyer flasks and incubated in dark at 21 ± 2 ºC for of 8–10 days with periodic shaking. Fungal metabolites were extracted by solvents; the CF was extracted with ethyl acetate in a separating funnel. The MM was dried (40 ºC) and powdered, which was then extracted with methanol. The CF and MM extracts were evaporated to dryness and resultant CF and MM compounds were dried at room temperature using the rotary flash evaporator and re-extracted with respective solvents to obtain the condensed extracts (Bhardwaj et al. 2015).

Antimicrobial assay in vitro

The solvent extracts of the selected endophytes were screened for their antimicrobial activity by well diffusion method (Raviraja et al. 2006). The crude extracts (10 mg) of CF or MM were dissolved in 1000 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and diluted to 100, 50, 25 and 12.5%. Each well in the agar plate received 20 μl of the extract. The experiment was carried out in triplicate. Amoxicillin (Amozlin-250), chloramphenicol (Paraxin 250, Abbott Healthcare Pvt. Ltd.) or ciprofloxacin (Ciprodac 250, CADILA Pharmaceuticals limited) (250 mg l−1) were used as positive controls for bacterial assay, while bavistin and fluconazole were used as a positive control for fungal assay; DMSO served as the negative control. Test organisms included two gram-positive bacteria—Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC 902), Enterococcus faecalis (MTCC 439) and three gram-negative bacteria- Escherichia coli (MTCC 1559), Pseudomonas fluorescens (MTCC 9768) and Salmonella enterica (MTCC 738); one clinical fungal pathogen- Candida albicans (MTCC 3017) and three other fungal species—Aspergillus niger (isolated from Bhadravathi soil), Fusarium oxysporum (MTCC 2485), and Aspergillus flavus (MTCC 2813). All except A. niger were obtained from the Institute of Microbial Technology (IMTECH), Chandigarh, India. The diameter of the zone of inhibition (ZI, mm) formed around each well was measured to evaluate the antimicrobial activity.

Mycochemical assay

The solvent extracts of C. tsudae were assayed for the presence of secondary metabolites like alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, sterols, tannins, glycosides, triterpenoids, coumarins, quinones, anthraquinones, phlobatannins, lignin, oils and fats, saponins, reducing sugar and amino acids by the method of Harborne (1984).

Assay of the electrochemical potential of C. tsudae metabolites

The electrochemical potential of the partially purified fungal extracts was determined by Cyclic Voltammetry using the Electrochemical Workstation CHI 660c. The experimental set up consisted of glassy carbon, the working electrode and methanol extract modified glassy carbon electrode (GCE) (3-mm dia.), a platinum wire as a counter electrode and saturated calomel as a reference electrode (Arulpriya et al. 2010). The electrode was pretreated with potassium chloride (1 M, 2 mg) to evaluate the effect of different scan rates on the anodic oxidation of the extract. The redox potential behavior of extracts was read by modifying the sweep rate from 50 to 300 mV s−1. The voltammetric measurement of the fungal extracts was run at different scan rates, the concentration at the pH range of 6–7 (Deepa et al. 2014).

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis

The metabolite extracts of C. tsudae exhibiting antimicrobial and antioxidant activities were dissolved in water (20 mg ml−1) and centrifuged (12,000 rpm, 10 min). The supernatant was concentrated for HPLC analysis at 30 ºC and analysed with methanol/phosphate (20:80) as the mobile phase, and a sample injection volume of 20 μl-at the flow rate: 1.0 ml min−1, and detection wavelength of 327 nm (Chen et al. 2010a, b).

OHR LC–MS analysis

The partially purified ethyl acetate extract of C. tsudae was subjected to chemical profiling by OHR LC–MS (Q-Exactive Plus Biopharma—Thermo Scientific Xcalibur, Version 4.2.28.14). The extracted compounds were separated on a Hypersil Gold 3 micron 100 × 2.1 mm (Thermo Scientific) column. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in milli Q water as solvent A and methanol as solvent B with a flow rate of 1 ml min−1 (Kumara et al. 2014). The data were obtained by collecting the full-scan mass, and compounds were detected using a UV detector at λ max of 290 nm. The direct infusion was done by both negative and positive ionization modes and at mass (m/z) ranging from 50 to 8000 amu (analyzed at Sophisticated Analytical Instrument Facility (SAIF), IIT, Bombay).

Statistical methods

The incubated plates were arranged in complete randomized design and the triplicate data were analyzed to determine the colonization frequency (%) of fungal isolates and diversity and evenness indices and species richness of endophytic fungal isolates (Simpson and Shannon) (Suryanarayanan et al. 2000) and antimicrobial activity (Duncan’s multiple range test, P < 0.05, Chen et al. 2010a).

Results and discussion

Among the grass species, Lolium and Festuca were investigated extensively for their endophytic association with fungi (Clay 1990; Saikkonen et al. 2016). However, less scrutiny is paid to other grass species and the associated endophytic fungi. Cynodon dactylon is cosmopolitan in distribution and finds importance in traditional herbal medicine (Dhar et al. 1968). As with other grass species (Rekha and Shivanna, 2014), C. dactylon is also colonized by endophytic fungal isolates, that might vary in their diversity depending on the habitat and eco-geographical conditions. In this context, this grass species growing in the human-inhabited Singanamane region of Bhadravathi district of Karnataka was selected for the study. Several studies document the mutualistic association of endophytic fungi with host plants that might vary depending on the study regions (Lu et al. 2000; Radu and Kqueen 2002; Handayani et al. 2017).

The present investigation revealed that an overall of 23 endophytic fungal species of 13 genera of six families accompanies C. dactylon (Table 1). The endophytic fungal species occurrence in plant segments also varied depending on the isolation method; it was high on PDA followed by MEA and least in MB. The PDA medium is well identified to support the growth of several fungal species, including the fast-growing ones that suppressed the slow-growing species. Hence, the slow-growing species require other media such as MEA or Czapek dox agar for their expression (Sun et al. 2013). Species of Aspergillus and Penicillium expressed high on PDA, whereas species of Cladosporium and Curvularia, and part of morphotypes expressed on MEA. Chaetomium globosum, Stachybotrys chartarum and species of Alternaria expressed well in the MB method (Table 1). The high expression of remarkable fungal endophytes on the MB could be attributed to the stress induced by the lack of availability of nutrients during fungal expression (Tibpromma et al. 2018) or due to the abundant availability of nutrients in the substratum favoring fungal growth. In contrast to the present study, endophytic fungi like Glomerella cingulata, Macrophomina phaseolina, Monodictys fluctuate, Myrothecium roridum, Pestalotiopsis mangiferae and Trichoderma harzianum were found abundantly in C. dactylon growing in the forest region (Rekha and Shivanna 2014). These reflections implied that the diversity of endophytic fungal communities in C. dactylon growing Singanamane region varied considerably in comparison to those existing in the uninhabited region of Lakkavalli forest (Rekha and Shivanna 2014).

Table 1.

Colonization frequency of endophytic fungal species occurring in the aerial parts of Cynodon dactylon by potato dextrose agar (PDA), malt extract agar (MEA) and moist blotter method (MB) methods

| Fungal species | Fungal incidence (%)a /Incubation methods | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PDA | MEA | MB | |

| Anamorphic ascomycetes | |||

| Aspergillus spp.b | 32.01 (3) | 33.89 (3) | 0 |

| Alternaria spp.c | 0.99 (2) | 0.99 (2) | 3.48 (1) |

| Cladosporium spp.d | 5.64 (3) | 20.53 (3) | 5 (3) |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 3.99 | 0 | 0 |

| Penicillium spp.e | 78.96 (5) | 37.04 (5) | 0 |

| Total fungal incidence (%)f | 121.59 (14) | 92.45 (13) | 8.48 (4) |

| Teleomorphic ascomycetes | |||

| Bipolaris vietoriae | 0 | 0 | 0.44 |

| Chaetomium globosum | 0.66 | 0 | 5.21 |

| Curvularia spp.g | 6.12 (2) | 10.98 (2) | 1.22 (1) |

| Drechslera specifera | 4.98 | 15.99 | 0.88 |

| Helminthosporium velutinum | 0 | 0 | 0.44 |

| Stachybotrys chartaram | 0.33 | 0.99 | 16 |

| Total fungal incidence (%)h | 12.09 (15) | 27.96 (4) | 24.19 (6) |

| Morphotypesi | 10.35 (3) | 26.08 (3) | 0 |

aFungal endophyte occurrence was calculated based on the number of segments colonized by each fungus over the total number of segment studied and represented as percentage, Data are an average of 3 replicate with 100 segments in each replicates. MB Moist blotter method, PDA potato dextrose agar, MEA Malt extract agar

bAspergillus species total incidence in three methods = A. niger (19.8, 20.97 and 0), A. flavus (1.5, 6.26 and 0) and A. awamori (10.65, 6.66 and 0)

cAlternaria spp. = A. alternata (0.33, 0.66 and 1.16), A. tensis (0, 0.33 and 0)

dCladosporium spp. = C. cladosporioides (2.77, 11.54 and 1.66), C. harbarum (2.81, 8.99 and 0)

ePenicillium spp. = P. citrinum (23.32, 17.73 and 0), P. cumenea (39.32, 11.66 and 0), Penicillium spp.(Green mycelia) (2.99, 3.99 and 0), Penicillium spp.1(whitish pink mycelia) (11.99, 1 and 0) and Penicillium spp.2( whitish yellow mycelia) (1.33, 2.66 and 0)

fTotal anamorphic ascomycetes fungal incidence; gCurvularia spp. = C. tsudae (2.11, 3.99 and 0), C. lunata (1.33, 2.33 and 1.22)

hTotal teleomorphic ascomycetes fungal incidence

iNSF 1 = white (Non sporulating Fungi)(11.77, 8.2 and 0), NSF 2 = Black (9.32, 7.76 and 0) and NSF 3 (gray) ( 4.99, 2.76 and 0)

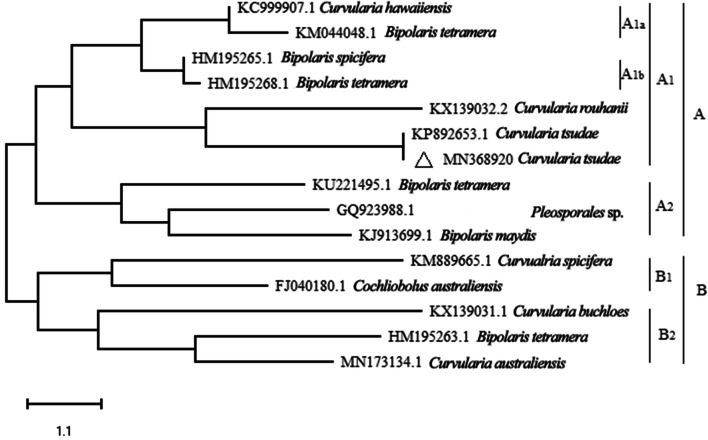

The present study also detailed the expression of more anamorphic than the teleomorphic ascomycetous forms. The assemblages of anamorphic and teleomorphic ascomycetous forms on PDA and MEA have been noted to be distinct in tropical regions and other grass species (Marquez et al. 2007; Higgins et al. 2014). Among isolates (Aspergillus flavus, Cladosporium cladosporioides, C. tsudae and Penicillium citrinum) that were randomly selected for determining the antimicrobial activity in vitro, an isolate of C. tsudae (isolate 007) was identified as highly effective in inhibiting clinical strains in vitro (data not shown). The confirmation of the identity of the isolate was supported by its ITS regions of rDNA as Curvularia tsudae (Tsuda & Ueyama) H. Deng (sequence submitted to.NCBI Gene Bank, Acc. No. MN368920). The nucleotide sequence was matched for the relatedness with those of distinct species of Curvularia isolated from different hosts and a phylogenetic tree was constructed (Fig. 1). The tree segregated into two main clusters (A and B) and each one, in turn, is separated into two sub-clusters like A1 and A2 and B1, B2. Further, subclades of A1 are divided into A1a and A1b. The nucleotide sequence of the fungal endophyte C. tsudae got clustered in the sub-cluster A and again in A1. Further, the clustering of sequences of isolate 007 of C. tsudae and Curvularia rouhanii sourced from NCBI database and different geographical areas suggested the close evolutionary relationship between them. Similarly, the evolutionary relationship of endophytic Alternaria alternata, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Pestalotiopsis virgatula in Vitex negundo were also examined by establishing the phylogenetic tree (Ramesh and Rajendran 2017).

Figure 1.

Phylogentic tree showing the relationship among Curvularia tsudae endophytic fungi and with other related reference fungal species based on the sequence homologies. The tree was constructed based on the 18S rDNA gene sequences (ITS1-58S-ITS2) fragments sequence by using neighbour—joining method. Δ represents the sequence of above isolate from Cynodon dactylon

The Shannon and Simpson diversity and evenness indices of the endophytic fungal communities were higher on PDA than on MEA (Table 2). Among the aerial regions of grass species, the culm followed by leaf harbored most anamorphic and teleomorphic ascomycetes. Similar observations were also made in other studies (Amritha et al. 2012; D’souza and Bhat 2013). In addition to this, apart of fungal isolates failed to sporulate by any of the methods tested and such of them were identified as morphotypes or operational taxonomic units (OTUs). Previous studies have also chronicled the incidence of more than a few morphotypes that were later characterized as Phoma herbarum and Fusarium oxysporum by differentiating the ITS regions of morphotypes (Shivanna and Vasanthakumari 2011; Rekha and Shivanna 2014).

Table 2.

Species richness, diversity and evenness indices of endophytic fungi communities occurring in the aerial parts of Cynodon dactylon

| Incubation methodsa | Species richness | Diversity index | Evenness index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shannon (H’) | Simpson (D’) | Shannon (J’) | Simpson(E’) | ||

| MB | 8 | 1.42 | 3.70 | 0.58 | 0.4 |

| PDA | 20 | 2.54 | 4.00 | 0.64 | 0.5 |

| MEA | 18 | 2.57 | 4.20 | 0.68 | 0.5 |

aData based on the values of three different locations and data are averaged of three replicates, each incubation method with three samples (inflorescence, leaf and culm); 100 segments/sample/grass

The qualitative analysis of CF and MM of C. tsudae indicated the existence of outstanding secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, coumarins, glycosides, phenols, sterols, tannins and triterpenoids. Among the above, alkaloids and flavonoids are reported to be produced by grass endophytes (Clay 1990; Tan and Zou 2001; Chandrappa et al. 2013); the above compounds as well as tannins and triterpenoids reported for the antimicrobial property (Chandrappa et al. 2013). Some of these compounds with bioactive principles could have been stimulated in the host plant system due to the stress conditions (Santos et al. 2015).

In the present study, metabolites in ethyl acetate and methanol extracts of C. tsudae produced high antibacterial activity to all clinical strains (Tables 3, 4). In a previous study, Curvularia lunatus, also endophytic in C. dactylon, showed moderate activity to the clinical pathogens in vitro (Rekha and Shivanna 2014). An isolate of Curvularia from perennial grasses was also reported with good antibacterial activity (Raviraja et al. 2006). The antifungal activity of endophytic fungal metabolites was attributed to the activity of alkaloids, coumarins or phenols present in the extract (Bojase et al. 2002; Bhardwaj et al. 2015). In the present study, the partially purified extract of C. tsudae CF and MM showed the antibacterial activity higher than the positive standard controls like amoxicillin, chloramphenicol or ciprofloxacin. The high activity of C. tsudae metabolites inhibiting clinical species suggested its future application in the control of clinical microbes. This endophyte could be producing metabolites capable of inhibiting the colony culture of clinical species by targeting the biosynthesis of DNA gyrase, cell wall or proteins, respectively, similar to those of the standard antibiotics used in the study. The mycelial extract of C. tsudae also showed high antifungal activity to F. oxysporum and C. albicans but less than the standard bavistin @ 0.5 mg ml−1 and fluconazole at 10 mg ml−1 (Table 4). On the other hand, ethyl acetate fraction of C. tsudae showed high activity to F. oxysporum and moderate activity to C. albicans and A. niger which suggested that metabolites of C. tsudae might differ in its ability to inhibit different microorganisms. The high antibacterial potential of CF and MM extracts as compared to the authentic standards pointed at the possible involvement of alkaloids, coumarins, flavonoids and phenols, either individually or synergistically. However, specific novel compounds produced by C. lunatus were also reported with antifungal properties (Rekha and Shivanna 2014). On the ontrary, the low antifungal potential at a select concentration as compared to the authentic standards could be due to the production of insufficient of metabolites (Singh et al. 2017).

Table 3.

Antibacterial activity of ethyl acetate and methanol extracts of Curvularia tsudae endophytic in Cynodon dactylon

| Crude extract of fungal isolates | Zone of inhibition (mm)a/ test bacterial isolates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sab | Efb | Sec | Ecc | Pfc | |

| Ethyl acetate extract of culture filtrate concentrations (%) | |||||

| 100 | 16.33 ± 0.57** | 18.33 ± 0.55 | 17.33 ± 0.57 | 17.33 ± 0.57* | 18.33 ± 0.57 |

| 50 | 14.33 ± 0.55 | 15.33 ± 0.57 | 15.33 ± 0.57 | 14.33 ± 0.55* | 13.33 ± 0.57 |

| 25 | 11.33 ± 0.56** | 10.33 ± 0.53 | 10.33 ± 0.57 | 10.33 ± 0.57 | 8.33 ± 0.53** |

| 12 | 8.33 ± 0.50 | 5.33 ± 0.50 | 7.33 ± 0.52** | 6.33 ± 0.57 | 6.33 ± 0.57 |

| Methanol extract of mycelial mat concentrations (%) | |||||

| 100 | 25.33 ± 0.57** | 14.33 ± 0.55 | 16.33 ± 0.57* | 16.33 ± 0.57 | 18.33 ± 0.57* |

| 50 | 15.33 ± 0.54 | 11.33 ± 0.56* | 12.33 ± 0.57 | 13.33 ± 0.57 | 14.66 ± 0.54 |

| 25 | 11.33 ± 0.56 | 7.33 ± 0.50 | 10.33 ± 0.57 | 11.33 ± 0.56 | 12.33 ± 0.57 |

| 12 | 9.33 ± 0.51 | 5.33 ± 0.57** | 5.33 ± 0.50 | 8.33 ± 0.53** | 9.33 ± 0.51 |

| Amoxicillin | 6.33 ± 0.52 | 3.33 ± 0.50 | 5.33 ± 0.57 | 5.33 ± 0.57 | 6.33 ± 0.57 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 18.33 ± 0.55 | 16.66 ± 0.57 | 14.33 ± 0.55 | 15.33 ± 0.57 | 9.33 ± 0.57 |

| Chloramphenicol | 12.33 ± 0.57 | 7.33 ± 0.57 | 9.33 ± 0.51 | 10.33 ± 0.57 | 6.33 ± 0.57 |

Values are mean ± SE of three replicates

*The antibacterial activity were compared using Duncan’s multiple range test (P = 0.05)

aValues are mean inhibition zone of three replicates (n = 3) crude extracts were dissolved DMSO (Dimethyl sulfoxide) at 10 mg in 1.5 ml of DMSO. Each well received 6.66 μl/well (20 μgml−1)

bg positive bacteria; SaStaphylococcus aureus, Ef Enterococcus faecalis

cg negative bacteria, SeSalmonella enterica,EcEscherichia coli, PfPseudomonas fluorescens

Table 4.

Antifungal activity of ethyl acetate and methanol extracts of Curvularia tsudae endophytic in Cynodon dactylon

| Crude extract of fungal isolates | Zone of inhibition (mm)a / test fungal isolates | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicansb | F. oxysporumc | A. niger | |

| Ethyl acetate extracts of culture filtrate concentrations (%) | |||

| 100 | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 10.33 ± 1.52* | 5.33 ± 0.57 |

| 50 | 2.33 ± 0.57 | 7.0 ± 1.0 | 3.33 ± 0.57 |

| 25 | 1.33 ± 0.57 | 4.66 ± 0.57** | 0 ± 0 |

| Methanol extract of mycelial mat concentrations (%) | |||

| 100 | 5.33 ± 0.57* | 14 ± 1.0 | 3.33 ± 0.57 |

| 50 | 3.33 ± 0.57 | 7.66 ± 1.15** | 7.0 ± 1.0 |

| 25 | 1.33 ± 0.57 | 3.33 ± 0.57 | 4.5 ± 0.70 |

| Bavistin | 5.33 ± 0.57 | 19.33 ± 0.57 | 13.66 ± 0.5 |

| Fluconazole | 6.27 ± 0.58 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

Values are mean ± SE of three replicates

*The antifungal activity were compared using Duncan’s multiple range test (P = 0.05)

aValues are mean inhibition zone of three replicate (n = 3); crude extracts were used at 20 μg ml−1 (20 μg per well)

bClinical pathogen

cPlant pathogen; concentration (12%) has low activity then the control; Positive control bavistin has used at 10 mg/ml and fluconazole at 0.5 mg/ml

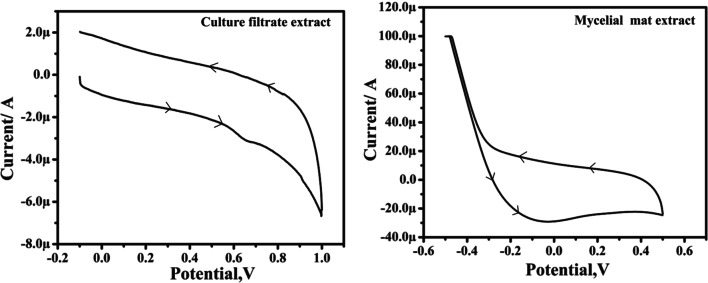

Cyclic voltammetry that was employed to determine the reducing ability of extracts yielded a good correlation between redox potential and antioxidant property. The ethyl acetate extract of endophytic fungi under the influence of anodic and cathodic current potential (Ipa, 0.6) generated two curves which increased with an increase in the scan rate; and this increase is directly proportional to the root of scan rate (v1/2). This high redox potential in the CF metabolite suggested its good antioxidant potential. The anodic peak produced between 0.6 and 0.7 V at pH 7 corresponded to high values of Ipa (one peak) for the CF which indicated the presence of a prominent compound. On the other hand, the failure of MM extract to produce any peak indicated the lack of any compound with high redox potential (Fig. 2). Indication of good antioxidant activity in the extract is associated with the predominant presence of flovonoid and phenolic compounds (Sochor et al. 2013). Noel et al. (2000) and Simić et al. (2007) also proved that compounds with strong scavenging capacity oxidize relatively at low potential. Further, the shifting of anodic peak potential towards the positive value was shown to possess the scavenging oxygen-free-radicals in the extract (Keffous et al. 2016). Observations of the current study prompted the further investigation of compounds relating to the antimicrobial and antioxidant activities.

Figure 2.

Cyclic voltammogram of ethyl acetate extract of culture filtrate and methanol extract of mycelial mat of Curvularia tsudae. The measurement was carried out at a scan rate of 50–300 mV s-1 and using glassy carbon (3-mm dia.) as working electrode, saturated calomel as the reference electrode, and a platinum wire as the auxiliary electrode at pH 7.0

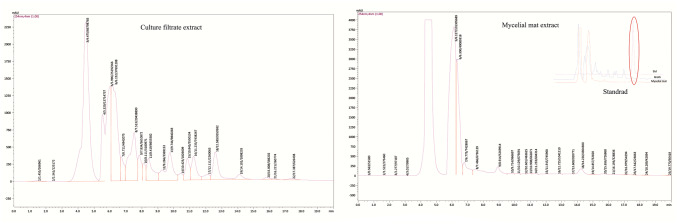

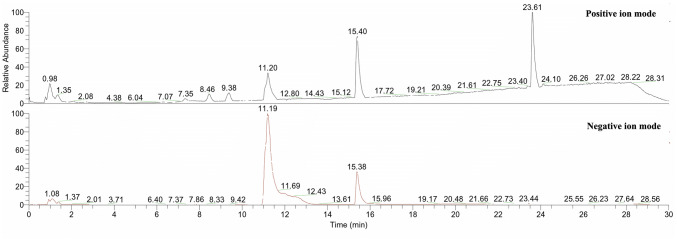

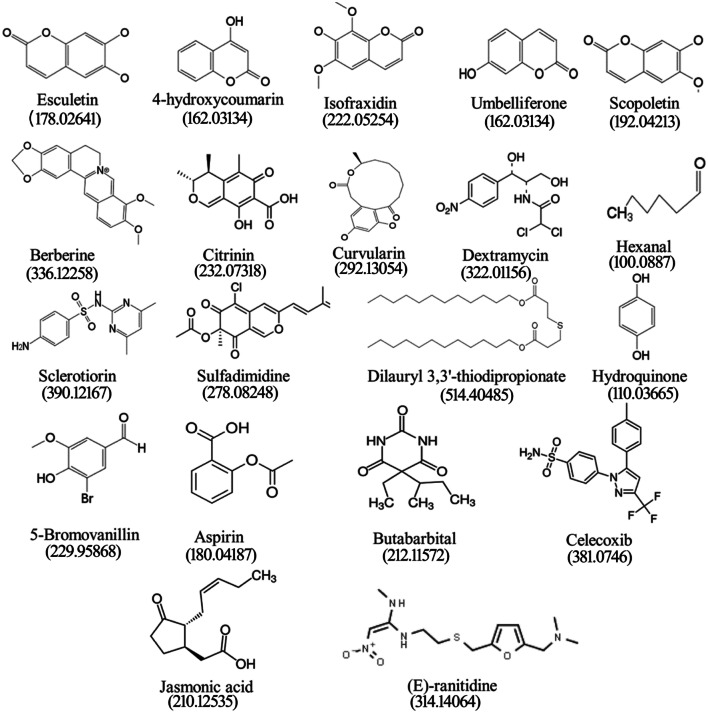

The HPLC chromatograms of both the CF and MM extracts of C. tsudae showed peaks at a retention time of 14.43 min, in comparison to the UV spectra generated by coumarins standard under identical chromatogram conditions (Fig. 3). The compounds present in CF and MM were identified by HPLC as coumarins. Hence, either coumarins or few analogous compounds could be responsible for high electrochemical behavior associated with strong redox potential suggesting the possible antimicrobial activity. Liu et al. (2008) also reported the production of 7-amino-4-methyl coumarin from endophytic Xylaria species in Ginkgo biloba with a high antimicrobial spectrum. The previous experiments suggested that both coumarins and flavonoids have antioxidant and antimicrobial properties (Umashankar et al. 2014). In the present study, OHR LC–MS analysis of CF extract yielded abundant positive [M + H]+ and negative [M-H]− ions that were distinguished based on their chemical constituents and associated activities. The chromatograms (Fig. 4) exhibiting prominent peaks corresponded to more than 25 compounds in the extract. Among them, compounds like esculetin, 4-hydroxycoumarin, isofraxidin, umbelliferone and scopoletin are the intermediate forms of coumarins with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties (Table 5). In previous research work, isocoumarins were identified with potential antimicrobial and antitumor activities (Liu et al. 2005). Other synergistic compounds included berberine, citrinin, curvularin, dextramycin, hexanal, sclerotiorin, sulfadimidine, dilauryl 3,3′-thiodipropionate, hydroquinone and 5-bromovanillin with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties (Fig. 5; Table 5).

Figure 3.

HPLC of culture filtrate (ethyl acetate) and mycelia mat (methanol) extracts of Curvularia tsudae showing the presence of coumarins. The mobile phase used was 0.1% methanol/phosphate (20:80, v/v) at the flow rate of 1.0 mL min-1. Registrations of peak and retention time were recorded by refractive index detection. Fungal samples showed a peak with retention time 14.10 and 14.22 min, which was found to be identical to authentic coumarins

Figure 4.

OHR LC-MS profiling of ethyl acetate extract of Curvularia tsudae endophytic in Cynodon dactylon. Both upper and lower panel shows typical ion chromatograms, obtained in ESI and APCI (positive and negative mode ionization). Retention times (in minutes) are indicated for the most intense peaks (difference between the two detectors is 0.15 min)

Table 5.

Chemical composition of ethyl acetate extracts of Curvularia tsudae endophytic fungi in Cynodon dactylon

| Sl. No | Compound | Molecular formula and weight RT [min] | mzCloud Best Match | Properties | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sulfadimidine | C12H14N4O2S 278.08248 0.98 | 80.8 | Antifungal agent | Chowdhary and Kaushik, (2018) |

| 2 | Methyl 4,6-dideoxy-4-[(2,4-dihydroxybutanoyl)amino]-2-O-methylhexopyranoside | C12H23NO7 293.14678 1.35 | 90.5 | Unknown | |

| 3 | Hydroquinone | C6H6O2 110.03665 2.08 | 62.1 | Antioxidant agent | NCI, (2003) |

| 4 | 5-Bromovanillin | C8H7BrO3 229.95868 4.38 | 65.8 | Antioxidant agent | Gaspar et al. (2009) |

| 5 | Celecoxib | C17H14F3N3OS 381.0746 6.04 | 69.4 | Anti-inflammatory agent | Srisailam and Veeresham (2010) |

| 6 | Butabarbital | C10H16N2O3 212.11572 7.07 | 72.5 | Analgesic agent | Lednicer and Szmuszkovicz (1980) |

| 7 | Esculetin | C9H6O4 178.02641 7.35 | 80.1 | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and antitumour, anticoagulant agents | Liang et al. (2017) |

| 8 | Isofraxidin | C11H10O5 222.05254 9.38 | 71.7 | Antioxidant | Li et al., (2014) |

| 9 | 4,6-Dichloro-N-phenyl-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine | C9H6Cl2N4 239.99784 11.20 | 80.2 | Unknown | |

| 10 | Dextramycin | C11H12Cl2N2O5 322.01156 12.80 | 89.0 | Antibiotic | NCATS, (2012) |

| 11 | Curvularin | C16H20O5 292.13054 14.43 | 65.4 | Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory | Ha (2017); Ataides et al. (2018) |

| 12 | 4-Hydroxycoumarin | C9H6O3 162.03134 15.12 | 73.7 | Antioxidant | Bye and King (1970) |

| 13 | 7,7-Dimethyl-10-oxo-5,6,7,8,9,10-hexahydrobenzo[8]annulen-5-yl trifluoroacetate | C16H17F3O3 314.11232 15.40 | 77.0 | Unknown | |

| 14 | Jasmonic acid | C12H18O3 210.12535 17.72 | 66.6 | Plant growth promoter | Fonseca et al. (2009) |

| 15 | Aspirin | C9H8O4 180.04187 19.21 | 70.4 | Anti-inflammatory analgesic, antipyretic, and anticoagulant agents | NCI, (2003) |

| 16 | Sclerotiorin | C21H23ClO5 390.12167 20.39 | 77.9 | Antimicrobial and anticancer agents | Lin et al., (2012) |

| 17 | Scopoletin | C10H8O4 192.04213 21.61 | 61.1 | Antifungal agent | Carpinella et al. (2005) |

| 18 | Citrinin | C13H14O5 232.07318 22.75 | 58.8 | Antimicrobial agent | Mazumder et al. (2002) |

| 19 | Berberine | C20H18NO4 336.12258 23.40 | 63.9 | Antimicrobial agent | Egan et al. (2016) |

| 20 | Methyl N-[(9H-fluoren-9-ylmethoxy)carbonyl] Phenylalanylphenyl alaninate | C34H32N2O5 548.2332 23.61 | 77.5 | Unknown | |

| 21 | Umbelliferone | C9H6O3 162.03134 26.26 | 51.3 | Antimicrobial agent | Jurd et al. (1971) |

| 22 | Dilauryl 3,3′-thiodipropionate | C30H58O4S 514.40485 27.02 | 62.5 | Antioxidant | Karahadian and Lindsay (1988) |

| 23 | (E)-Ranitidine | C13H22N4O3S 314.14064 28.22 | 89.0 | Anti-Inflammatory agent | NCATS, (2003) |

| 24 | Hexanal | C6H12O 100.0887 28.31 | 60.6 | Antimicrobial agent | Katoch et al. (2017) |

| 25 | 2-Chloro-5-[5-(3-chlorophenyl)-1,3-oxazol-2-yl]-4-(trifluoromethyl)pyridine | C15H7Cl2F3N2O 357.9887 11.19 | 61.4 | Unknown |

Figure 5.

Chemical structure and molecular mass of compounds detected in the culture filtrate of Curvularia tsudae endophytic in Cynodon dactylon by OHR LC–MS

In the present study, some compounds were established with high retention peaks in both positive and negative modes, however, information on biological activities of such compounds is not available and this requires further investigation. Compounds such as aspirin, butabarbital, celecoxib, jasmonic acid and (E)-ranitidine present in the extract of C. tsudae are known to be associated with anticoagulant, analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities (Fig. 5) and plant growth promotion (NSATS 2003; Lednicer and Szmuszkovicz 1980; Srisailam and Veeresham 2010; Fonseca et al. 2009; Institiute and USA, 2003).

The present study revealed that C. dactylon harbored endophytic fungal assemblages whose expression depended on the plant parts. The frequency of occurrence of the fungal endophytes depended on the isolation methods employed. Amongst the endophytic fungi, an isolate of C. tsudae showed antimicrobial activity and particularly, antibacterial activity higher than the standard positive controls. The metabolites of C. tsudae exhibited electrochemical behavior with high redox potential suggesting the antioxidant activity. The presence of five coumarin analog compounds in the extract suggested their possible application and exploitation in pharmaceutical industries. Some of the metabolites of C. tsudae were also documented with other pharmaceutical and agricultural importance.

Acknowledgements

A part of the research paper is based on the M.Sc. project work of the first author who acknowledges Kuvempu University for financial support. The authors thank the Sophisticated Analytical Instrument Facility (SAIF), IIT, Bombay for OHR LC–MS service for chemical profiling. Special thanks to Mr. Chethan Kumar Naik and Mr. Shashikumar J.K, Department of Industrial Chemistry, Kuvempu University, Shankaraghatta, for the assistance during Cyclic voltammetric analysis.

Author contributions

MBS conceived the initial work idea and NR performed the laboratory experiments and data analysis. MBS, NR and MMV worked on the data interpretation of the work. BEKS helped NR to perform Cyclic voltammetry in their laboratory. NR prepared the first draft copy of the manuscript and the corrections were made and finalized by MBS. All four authors NR, MMV, BEKS and MBS authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

R. Nischitha, Email: nischithalraj9@gmail.com

M. M. Vasanthkumari, Email: mmvasantha@yahoo.co.in

B. E. Kumaraswamy, Email: kumaraswamy21@gmail.com

M. B. Shivanna, Email: mbshivanna@yahoo.co.uk

References

- Achar KGS, Shivanna MB. Colletotrichum leaf spot disease in Naravelia zeylanica and its distribution in Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary, India. Indian Phytopathol. 2013;66:125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Reza MS, Jabbar A. Antimicrobial activity of Cynodon dactylon. Fitoterapia. 1994;65:463–464. [Google Scholar]

- Amirita A, Sindhu P, Swetha J, Vasanthi NS, Kannan KP. Enumeration of endophytic fungi from medicinal plants and screening of extracellular enzymes. World J Sci Tech. 2012;2:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Arulpriya P, Lalitha P, Hemalatha S. Cyclic voltammetric assessment of the antioxidant activity of petroleum ether extract of Samanea saman (Jacq.) Merr Pelagia Res Libr. 2010;1(3):24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ataides D, Pamphile JA, Garcia A, Dos Santos Ribeiro MA, Polonio JC, Sarragiotto MH, Clemente E. Curvularin produced by endophytic Cochliobolus sp. G2–20 isolated from Sapindus saponaria L. and evaluation of biological activity. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2018;8(12):032–037. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett HL, Hunter BB (1972) Illustrated genera of imperfect fungi. Illustrated genera of imperfect fungi, 3rd ed

- Bhardwaj A, Sharma D, Jadon N, Agrawal PK. Antimicrobial and phytochemical screening of endophytic fungi isolated from spikes of Pinus roxburghii. Arch Clin Microbiol. 2015;6(3):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KG, Nagendran CR (2001) Sedges and Grasses (Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts). Dehra Dun, Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh (Ed).

- Bojase G, Majinda RR, Gashe BA, Wanjala CC. Antimicrobial flavonoids from Bolusanthus speciosus. Planta Med. 2002;68(07):615–620. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bye A, King HK. The biosynthesis of 4-hydroxycoumarin and dicoumarol by Aspergillus fumigatus Fresenius. Biochemi J. 1970;117(2):237–245. doi: 10.1042/bj1170237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpinella MC, Ferrayoli CG, Palacios SM. Antifungal synergistic effect of scopoletin, a hydroxycoumarin isolated from Melia azedarach L. fruits. J Agri Food Chem. 2005;53(8):2922–2927. doi: 10.1021/jf0482461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrappa CP, Anitha R, Jyothi P, Rajalakshmi K, Seema MH, Sharanappa GMP. Phytochemical analysis and antibacterial activity of endophytes of Embelia tsjeriam (L.) Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2013;3:467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Sang X, Li S, Zhang S, Bai L. Studies on a chlorogenic acid-producing endophytic fungi isolated from Eucommia ulmoides Oliver. J Indu Microbial Biotechnol. 2010;37(5):447–454. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XM, Dong HL, Hu KX, Sun ZR, Chen J, Guo SX. Diversity and antimicrobial and plant-growth-promoting activities of endophytic fungi in Dendrobium loddigesii Rolfe. J Plant Growth Regula. 2010;29(3):328–337. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra RN, Handa KL (1982) Indigenous drugs of India, 2nd ed, Academic Publishers India 504

- Chowdhary K, Kaushik N. UPLC–MS and dereplication-based identification of metabolites in antifungal extracts of fungal endophytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci India Sect B Biol Sci. 2018;89(4):1379–1387. [Google Scholar]

- Clay K. Fungal endophytes of grasses. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 1990;21(1):275–297. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza MA, Bhat DJ. Occurrence of microfungi as litter colonizers and endophytes in varied plant species from the Western Ghats forests, Goa. India Mycosphere. 2013;4(567):582. [Google Scholar]

- Deepa R, Manjunatha H, Krishna V, Kumara SB. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity and antioxidant activity by electrochemical method of ethanolic extract of Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb bark. J Biotechnol Biomateri. 2014;4(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar ML, Dhawan M, Melhrotra CL. Screening of Indian plants for biological activity. Part I Indian J Experi Biol. 1968;6:232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan JM, Kaur A, Raja HA, Kellogg JJ, Oberlies NH, Cech NB. Antimicrobial fungal endophytes from the botanical medicine goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis) Phytochem letters. 2016;17:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2016.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MB (1976) More dematiaceous hyphomycetes. Kew, commonwealth mycological institute

- Fonseca S, Chini A, Hamberg M, Adie B, Porzel, Kramell R, Miersch O, Wasternack C, Solano R (2009) (+)-7-iso-Jasmonoyl-l-isoleucine is the endogenous bioafctive jasmonate. Nat Chem Biol 5(5): 344 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gaspar A, Garrido EM, Esteves M, Quezada E, Milhazes N, Garrido J, Borges F. New insights into the antioxidant activity of hydroxycinnamic acids: synthesis and physicochemical characterization of novel halogenated derivatives. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44(5):2092–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gond SK, Verma VC, Mishra A, Kumar A, Kharwar RN (2010) Role of fungal endophytes in plant protection. In: Arya A, Perello AE Mycoscience (eds) Management of Fungal plant pathogens, CAB International, Wallingford, pp 183–197

- Ha T, Ko W, Lee S, Kim YC, Son JY, Sohn J, Oh H. Anti-inflammatory effects of curvularin-type metabolites from a marine-derived fungal strain Penicillium sp. SF-5859 in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW264 7. macrophages. Marine Drugs. 2017;15(9):282. doi: 10.3390/md15090282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harborne BJ. Methods of plant analysis, in Phytochemical Methods. 2. London: Chapmann and Hall; 1984. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jurd L, King AD, Jr, Mihara K. Antimicrobial properties of umbelliferone derivatives. Phytochem. 1971;10(12):2965–2970. [Google Scholar]

- Katoch M, Bindu K, Phull S, Verma MK. An endophytic Fusarium sp. isolated from Monarda citriodora produces the industrially important plant-like volatile organic compound hexanal. Microbiol. 2017;163(6):840–847. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keffous F, Belboukhari N, Sekkoum K, Djeradi H, Cheriti A, Aboul-Enein HY. Determination of the antioxidant activity of Limoniastrum feei aqueous extract by chemical and electrochemical methods. Cogent Chem. 2016;2(1):1186141. [Google Scholar]

- Kirtikar KK, Basu BD. Indian Medicinal Plants. 2. India: Lalit Mohan Publication; 1980. p. 2650. [Google Scholar]

- Kumara PM, Soujanya KN, Ravikanth G, Vasudeva R, Ganeshaiah KN, Shaanker RU. Rohitukine, a chromone alkaloid and a precursor of flavopiridol, is produced by endophytic fungi isolated from Dysoxylum binectariferum Hook. f and Amoora rohituka (Roxb) Wight Arn Phytomed. 2014;21(4):541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lednicer D, Szmuszkovicz J (1980) U.S. Patent No. 4,212,878. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

- Li P, Zhao QL, Wu LH, Jawaid P, Jiao YF, Kadowaki M, Kondo T. Isofraxidin, a potent reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger, protects human leukemia cells from radiation-induced apoptosis via ROS/mitochondria pathway in p53-independent manner. Apoptosis. 2014;19(6):1043–1053. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-0984-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Ju W, Pei S, Tang Y, Xiao Y. Pharmacological activities and synthesis of esculetin and its derivatives: a mini-review. Molecules. 2017;22(3):387. doi: 10.3390/molecules22030387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay RC. Evaluation of the mechanism of dilauryl thiodipropionate antioxidant activity. J Am Oil Chemists Soci. 1988;65(7):1159–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Liu JY, Song YC, Zhang Z, Wang L, Guo ZJ, Zou WX, Tan RX. Aspergillus fumigatus CY018, an endophytic fungus in Cynodon dactylon as a versatile producer of new and bioactive metabolites. J biotechnol. 2004;114(3):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Dong M, Chen X, Jiang M, Lv X, Zhou J. Antimicrobial activity of an endophytic Xylaria sp. YX-28 and identification of its antimicrobial compound 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;78(2):241–247. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Yin H, Peng H, Li D. Endophytic fungi–a potential new resource of natural medicines. Chin J Curr Trad West Med. 2005;3:404–405. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder PM, Mazumder R, Mazumder A, Sasmal DS. Antimicrobial activity of the mycotoxin citrinin obtained from the fungus Penicillium citrinum. Anci Sci life. 2002;21(3):191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institiute, USA (2003) Compound information. https://ncit.nci.nih.gov/ncitbrowser/ConceptReport.jsp?dictionary=NCI_Thesaurus&ns=NCI_Thesaurus&code=C287 Accessed 23 Nov 2019

- Noel M, Suryanarayanan V, Santhanam R. The influence of fluoride media and CH3CN on the voltammetric behavior of ferrocene, quinhydrone, and methyl phenyl sulfide on Pt and carbon electrodes. Electroanalysis. 2000;12(13):1039–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Petrini O. Taxonomy of endophytic fungi of aerial plant tissues. In: Fokkema NJ, van den Heuvel, editors. Microbiology of the Phyllosphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. pp. 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Porras-Alfaro A, Bayman P. Hidden fungi, emergent properties: endophytes and microbiomes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2011;49:291–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radu S, Kqueen CY. Preliminary screening of endophytic fungi from medicinal plants in Malaysia for antimicrobial and antitumor activity. Malaysian J Med sci. 2002;9(2):23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh V, Rajendran A. The molecular phylogeny and taxonomy of endophytic fungal species from the leaves of Vitex negundo L. Stud Fungi. 2017;2(1):26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rao RP, Manoharachary C (1990) Soil Fungi from Andhra Pradesh 45–48

- Raviraja NS, Maria GL, Sridhar KR. Antimicrobial evaluation of endophytic fungi inhabiting medicinal plants of the Western Ghats of India. Engineer Life Sci. 2006;6(5):515–520. [Google Scholar]

- Rekha D, Shivanna MB. Diversity, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of fungal endophytes in Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. and Dactyloctenium aegyptium (L.) P. Beauv. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2014;3:573–591. [Google Scholar]

- Saikkonen K, Young CA, Helander M, Schardl CL. Endophytic Epichloë species and their grass hosts: from evolution to applications. Plant mol Boil. 2016;90(6):665–675. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0399-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampangi-Ramaiah MH, Dey P, Jambagi S, Kumari MV, Oelmüller R, Nataraja KN, Ravishankar KV, Ravikanth G, Shaanker RU. An endophyte from salt-adapted Pokkali rice confers salt-tolerance to a salt-sensitive rice variety and targets a unique pattern of genes in its new host. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59998-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos IPD, Silva LCND, Silva MVD, Araújo JMD, Cavalcanti MDS, Lima VLDM. Antibacterial activity of endophytic fungi from leaves of Indigofera suffruticosa Miller (Fabaceae) Frontiers Microbial. 2015;6:350. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardl CL, Leuchtmann A, Chung KR, Penny D, Siegel MR. Coevolution by common descent of fungal symbionts and grass hosts. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Shivanna MB, Vasanthakumari MM. Temporal and spatial variability of rhizosphere and rhizoplane fungal communities in grasses of the subfamily Chloridoideae in the Lakkavalli region of the Western Ghats in India. Mycosphere. 2011;2(255):271. [Google Scholar]

- Simić A, Manojlović D, Šegan D, Todorović M. Electrochemical behavior and antioxidant and prooxidant activity of natural phenolics. Molecules. 2007;12(10):2327–2340. doi: 10.3390/12102327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T, Jyoti K, Patnaik A, Singh A, Chauhan R, Chandel SS. Biosynthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles using an endophytic fungal supernatant of Raphanus sativus. J Gen Engineer Biotechnol. 2017;15(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sochor J, Dobes J, Krystofova O, Ruttkay-Nedecky B, Babula P, Pohanka M, Kizek R. Electrochemistry as a tool for studying antioxidant properties. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2013;8(6):8464–8489. [Google Scholar]

- Srisailam K, Veeresham C. Biotransformation of celecoxib using microbial cultures. Appl Biochemi Biotechnol. 2010;160(7):2075–2089. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8789-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel GA, Daisy B. Bioprospecting for microbial endophytes and their natural products. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:491–502. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.491-502.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian CV (1983) Hypomycetes taxonomy and biology, Vol I and II, Academic Press, London, pp 930

- Tan RX, Zou WX. Endophytes: a rich source of functional metabolites. Nat Prod Rep. 2001;18:448–459. doi: 10.1039/b100918o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umashankar T, Govindappa M, Ramachandra YL. In vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of partially purified coumarins from fungal endophytes of Crotalaria pallida. Inter J Cur Microbiol Appl Sci. 2014;3(8):58–72. [Google Scholar]