ABSTRACT

Inconsistent associations between lipids and circulating markers of fat-soluble vitamin and carotenoid status have been reported. The aim of this hypothesis-generating study was to examine the contribution of the LC-MS-based lipidome, characterized by lipid class, carbon count, and the number of unsaturated bonds, to the interindividual variability in circulating concentrations of retinol, carotenoids, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, α-tocopherol, γ-tocopherol, and phylloquinone in 35 overweight and obese, but healthy men. A sparse partial least-squares method was used to accomplish this aim. Highly abundant phospholipids and triglycerides (TGs) contributed to the interindividual variability in phylloquinone, α-tocopherol, and γ-tocopherol. Interindividual variability in lycopene concentrations was driven by concentrations of low-abundant TG. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3, retinol, and the other carotenoids were not influenced by lipids. Except for lycopene, evaluation of lipids beyond class does not appear to further explain the interindividual variability in circulating concentrations of fat-soluble vitamins and carotenoids.

Keywords: lipids, fat-soluble vitamins, carotenoids, phylloquinone, tocopherol, retinol, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, lipidomics, micronutrients, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

Lipidomics does not appear to explain the interindividual variability in most circulating concentrations of fat-soluble vitamins and carotenoids beyond the interindividual variability explained by class.

Introduction

Validated biomarkers of micronutrient status are important tools in observational studies linking micronutrient exposure to disease risk (1). In the case of hydrophobic fat-soluble vitamins and carotenoids, the associations between various lipid classes and the interindividual variability of these circulating biomarkers are not consistent (2–6).

In the fasted state, retinol and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 circulate on specific binding proteins, but vitamin E and vitamin K forms and carotenoids are transported with lipids on lipoproteins (2, 7–10). Blood lipid profiles are typically described by triglycerides (TGs), total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol. However, thousands of distinct lipid molecular species have been identified in the circulation (11). Whereas TGs, free cholesterol, and cholesterol esters (ChEs) are the most abundant constituents of lipoproteins, glycerophospholipids, diglycerides (DGs), and free fatty acids (FFAs) constitute other important lipid classes (11, 12). Furthermore, esterified fatty acids can differ in carbon-chain length and the number of unsaturated bonds (11). With technological advances in characterization of the lipidome, there is an opportunity to broaden the study of lipids and their influence on these micronutrient biomarkers.

Following work by van den Broek et al. (13), in which micronutrients were correlated with molecules measured across multiple metabolomic and proteomic platforms, the objective of this hypothesis-generating study was to examine the contribution of the lipidome, characterized by lipid class, carbon-chain length, and number of unsaturated bonds, to the interindividual variability in circulating fat-soluble vitamins and carotenoids.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a secondary analysis of data from the placebo arm of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 5-wk intervention trial (NCT00655798) conducted from December 2006 to June 2007, to investigate the anti-inflammatory effects of nutritional interventions in 36 overweight and obese men with low-grade inflammation (14). The men (mean ± SD age: 47 ± 10 y) were otherwise healthy, with BMI 25.6–34.7 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included high fasting total cholesterol; acute inflammation (C-reactive protein >10 mg/L); a chronic disease related to inflammation (e.g., arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease); use of anticoagulant, antiplatelet, or anti-inflammatory medication; smoking; unexplained weight loss; alcohol intake >28 units/wk; following a weight-reduction diet; or use of dietary supplements. Placebo capsules contained 365 mg microcrystalline cellulose (Microz Food Supplements) or 1360 mg soy lecithin (Solgar Vitamin and Herb). The study protocol was approved by the independent Medical Ethics Committee (METOPP) (Tilburg, Netherlands).

Biochemical analyses

At the end of the 5-wk placebo period, blood samples were collected 4 h after a light standard breakfast (1597 kJ, % energy: 8.6 protein, 17.0 fat, 72.4 carbohydrates) preceded by an overnight fast (14). Samples for plasma lipids and micronutrient analysis were collected in lithium-heparinized tubes and tubes containing tri-potassium salts of EDTA (K3-EDTA), respectively. Serum and plasma were centrifuged for 15 min at 2000 × g at 4°C and separated within 30 min of collection and stored at −80°C in the dark until analysis.

Fat-soluble vitamins and carotenoids

Retinol, α-tocopherol, γ-tocopherol, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, and lycopene concentrations were measured in 2013, as previously described (13, 15, 16), in a laboratory that adheres to international bioanalytical guidelines for daily and long-term performance and participates in ring-tests. Serum phylloquinone was measured in 2019 from archived serum samples stored for ≤12 y at −80°C using reversed-phase HPLC with fluorometric detection in the Vitamin K Laboratory at the Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University, which participates in the vitamin K external quality assurance scheme (17, 18).

Plasma lipids

Plasma lipids were analyzed directly after study conclusion (2006/2007) with electrospray LC-MS using a Thermo Linear Trap Quadrupole equipped with a Thermo Surveyor HPLC pump, described previously (19). As described, the LC-MS platform performance was assessed by quality control sample (pooled plasma from all participants) analysis, placed after every 10 samples, and method performance was monitored using 5 internal standards and duplicate sample analysis (20). Concentrations of 131 lipids including 6 lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs), 19 phosphatidylcholines (PCs), 11 sphingomyelins (SPMs), 14 ChEs, 55 TGs, 4 DGs, and 22 FFAs were quantified. Baseline TGs, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol were measured with enzymatic techniques. LDL cholesterol was determined by the Friedewald calculation (14, 21).

Statistical analyses

Placebo-phase micronutrient and lipid data were not available for 1 participant so 35 of the 36 participants were included in this analysis. Circulating micronutrient and plasma lipid concentrations were described by means ± SDs. Given the small sample size and large number of highly correlated lipid exposures, we modeled the variability in circulating concentrations of each micronutrient using sparse partial least-squares (sPLS) regression. This method avoids overfitting when there may be few underlying or latent factors (components) that account for the variability in exposures and response variables (22). Using this technique, components are constructed to account for as much variability in the exposures as possible while maximizing the explained variability of the outcome (micronutrient). Loadings reflect the contribution of exposures (lipids) to the component (22).

The spls function from the mixOmics R package (23) in regression mode was used to decompose information from the 131 lipids into fewer components. The number of components for each model was determined by maximizing the predictability of the model with the fewest number of components that explained variability in both the predictor and response variables. A component was selected if its Q2 value, a parameter used to assess the goodness of prediction, was ≥0.0975, a cutoff proposed by Tenenhaus (24). R2 is regarded as a measure of explained variability and Q2 is equivalent to R2 when the training set model is applied to a test set. A Q2 that approximates R2 is a qualitative indicator that the sPLS model performance was not unique to the training data set.

Each model was cross-validated using the tune.spls function with the M-fold method, which resamples the data into n (35 in this analysis) groups, replicated 100 times. With 1 independent outcome per model, we investigated the number of lipids (25, 50, 75, 100, 125, or 131) to retain for ≤10 components. Components were added to the model if there was a gain in performance based on a 1-sided t test. All variables were centered and scaled. Phylloquinone, α-tocopherol, γ-tocopherol, lycopene, α-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin were skewed so these data were ln-transformed.

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive data for micronutrients and plasma lipids. ChEs, TGs, and PCs were the most abundant lipid classes. SPMs, FFAs, and DGs were present in very low quantities. ChEs (18:1) were ∼4 times more abundant than any other lipid. TGs with 50, 52, and 54 carbons were also highly abundant. These TGs contained 1–3, 1–4, and 3–5 unsaturated bonds, respectively. The top PCs had 34 and 36 carbons.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive data for the fat-soluble vitamins, carotenoids, and total lipids with sparse partial least-squares model parameters for the micronutrients

| Explained variability, R2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Components, n | Exposures, n | Vitamin or carotenoid | Lipids | Predictability, Q2 | |

| Phylloquinone,1 nM | 1.7 ± 1.7 | 1 | 131 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| Retinol, µM | 1.97 ± 0.31 | 1 | 131 | 1.00 | 0.34 | 0.03 |

| α-Tocopherol,1 µM | 29.0 ± 6.2 | 1 | 75 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 0.27 |

| γ-Tocopherol,1 µM | 1.74 ± 0.68 | 2 | 50, 131 | 1.00, 0.60 | 0.24, 0.21 | 0.20, 0.18 |

| 25-OH-vitamin D3, nM | 63.2 ± 32.8 | 9 | 50, 25, 131, 131, 131, 131, 100, 25, 50 | 1.00, 0.54, 0.45, 0.33, 0.26, 0.16, 0.11, 0.6, 0.5 | 0.10, 0.13, 0.10, 0.25, 0.11, 0.7, 0.3, 0.4, 0.2 | 0.17, −0.28, −0.38, −0.15, 0.26, 0.10, 0.21, −0.20, −0.34 |

| Lycopene,1 µM | 0.62 ± 0.30 | 1 | 25 | 1.00 | 0.26 | 0.20 |

| α-Carotene,1 µM | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 1 | 50 | 1.00 | 0.19 | −0.17 |

| β-Carotene, µM | 0.40 ± 0.17 | 1 | 100 | 1.00 | 0.22 | 0.03 |

| β-Cryptoxanthin,1 µM | 0.22 ± 0.20 | 1 | 25 | 1.00 | 0.25 | −0.15 |

| Total cholesterol,2 mg/dL | 231 ± 37 | |||||

| LDL cholesterol,2 mg/dL | 152 ± 31 | |||||

| HDL cholesterol,2 mg/dL | 47 ± 9 | |||||

| Total triglycerides,2 mg/dL | 147 ± 72 | |||||

Skewed distribution.

Plasma lipids were measured at the baseline study visit.

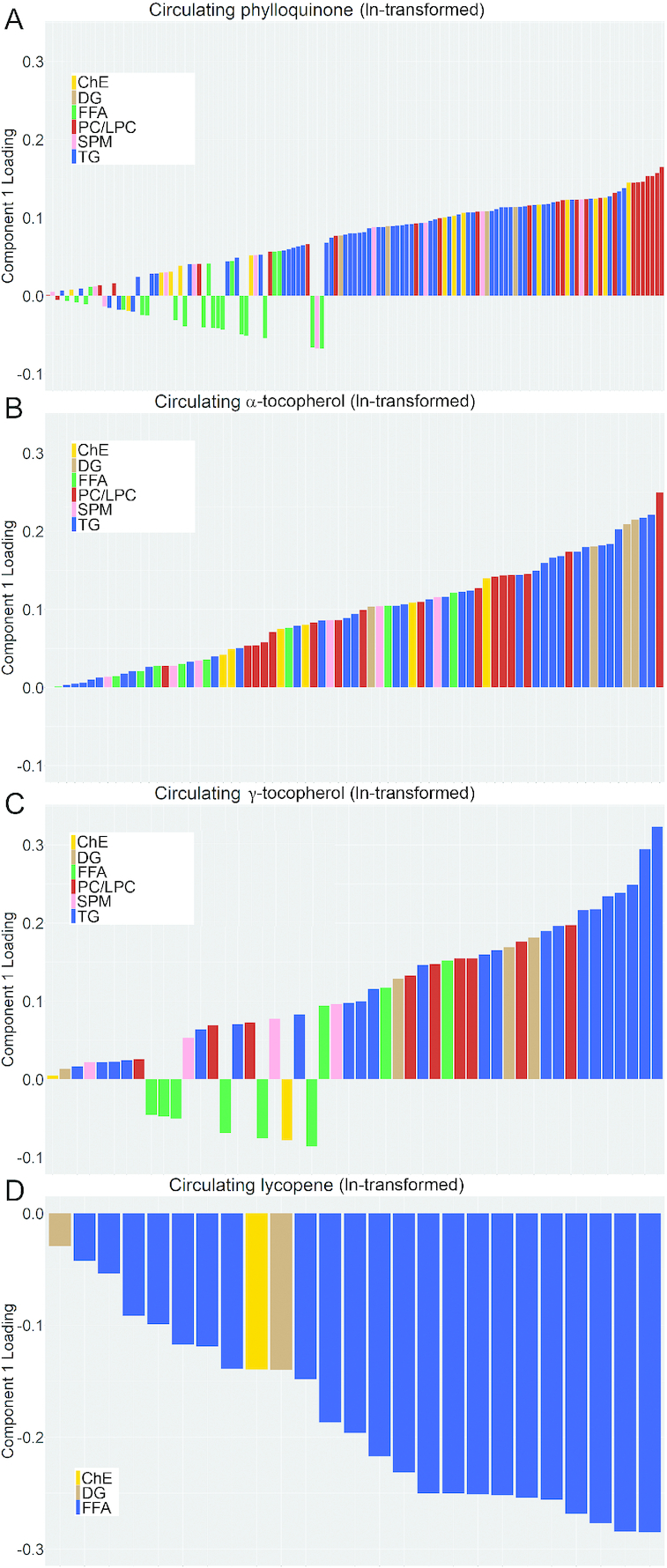

Table 1 shows the number of components, exposures, R2, and Q2 for each sPLS model. Figure 1 and Supplemental Tables 1–4 show the component 1 loadings for phylloquinone, α-tocopherol, γ-tocopherol, and lycopene, the micronutrients for which a robust model was established. Highly abundant LPCs (16:0) and PCs (34 or 36 carbons, 1–3 unsaturated bonds) explained the most variability in circulating phylloquinone. After these, several low-abundant ChEs and high-abundant TGs (50:2, 50:3, 52:1, 52:2) also contributed. The variability in γ-tocopherol was primarily explained by high-abundant TGs (52:4, 54:3–6, and 56:2–5) in addition to PCs (34:0) and few DGs. The variability in α-tocopherol was also explained by TGs and select PCs and DGs, with an overlap in carbon count and the number of unsaturated bonds. The variability in circulating lycopene was explained by TGs with 40–52 carbons. All loadings were negative, indicating an inverse relation. The top contributors had 40–46 carbons and 0–2 unsaturated bonds. Q2 was not comparable with R2 for retinol, α-carotene, β-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin so these models were not robust. For 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, the model appeared overfitted, requiring 9 components, none of which sufficiently accounted for variability in the exposures and response variables with adequate performance. For example, component 1 maximized the variability in circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 with Q2 > 0.0975, but only explained 10% of the variance in lipids. In contrast, component 4 explained more variance in lipids (25%), but limited variability in 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (33%) and had poor performance (Q2 = −0.15).

FIGURE 1.

Plasma lipid loading plots of component 1 from cross-sectional sparse partial least-squares regression models for circulating concentrations of (A) phylloquinone (131 lipids), (B) α-tocopherol (75 lipids), (C) γ-tocopherol (50 lipids), and (D) lycopene (25 lipids). ChE, cholesterol ester; DG, diglyceride; FFA, free fatty acid; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; SPM, sphingomyelin; TG, triglyceride.

Discussion

Using a sPLS technique, the relations between lipids (characterized by class, carbon-chain length, and the number of unsaturated bonds) and the interindividual variability in blood-based markers of fat-soluble vitamin and carotenoid status were assessed in healthy overweight and obese adult males. We found that lipids contributed to the variability in circulating phylloquinone, α-tocopherol, γ-tocopherol, and lycopene, but not 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, retinol, α-carotene, β-carotene, or β-cryptoxanthin.

The largest interindividual variability in circulating concentrations was observed for phylloquinone. We observed that high relative abundance TGs contributed to the variability in serum phylloquinone, but the contribution of highly abundant PC and LPC was unexpectedly greater. Phylloquinone concentrates in the TG-rich lipoprotein fraction (10), but it is plausible phylloquinone and TGs share transport mechanisms without a causal relation between the molecules. That high-abundant lipids explained the most variability in circulating phylloquinone suggests that total PCs and TGs sufficiently account for the variability in circulating phylloquinone and differentiation by number of carbons and unsaturated bonds does not explain more. These data also suggest that variances in PC/LPC may be more indicative of circulating phylloquinone than variances in TGs. The association between circulating phylloquinone and PC/LPC is not well-studied. However, there is biological plausibility to our findings. PC is critical to VLDL synthesis and higher circulating phylloquinone has been associated with higher VLDL particle number, independently of TGs (25) (JM Kelly, unpublished results). In addition, based on the chemical structure of phylloquinone, we posit that phylloquinone resides at the surface of the lipoprotein with PC rather than in the core with TGs (26, 27). Further research is required to confirm this. Importantly, these findings should not be extrapolated to other forms of vitamin K because the transport of menaquinones in the body is not well understood.

Consistent with the report by van den Broek et al. (13), the interindividual variability in α-tocopherol concentrations was also sensitive to variances in highly abundant PC/LPC. We also observed contributions of TGs for both vitamin E vitamers. That vitamin K and vitamin E vitamers were similarly influenced by lipids is in line with evidence that suggests there is overlap in the metabolic pathways of these 2 fat-soluble vitamins (26, 28, 29).

In contrast to the observations for phylloquinone, α-tocopherol, and γ-tocopherol, lycopene was inversely related to variances in a few low-abundant TGs. That low-abundant TGs accounted for the most variability in lycopene suggests there is something unique about TGs with 40–46 carbons and few unsaturated bonds with respect to circulating lycopene. Interestingly, a robust sPLS model was established for lycopene, but not the other carotenoids. Variances in circulating retinol and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 were not explained by lipids. This was not unexpected given that both fat-soluble vitamins are transported on specific binding proteins (7, 8).

Total lipids and the relative abundance of lipids according to the number of carbons and unsaturated bonds for these participants are consistent with previous reports (11) and micronutrient concentrations were within expected ranges for this population (13, 30). However, there are several limitations of this study. First, this was a cross-sectional analysis so it cannot be determined whether lipids influence micronutrients or vice versa. Second, the cohort was a small sample of healthy overweight and obese males and there was no control group of normal-weight males, which limits generalizability. Finally, for this pilot study, the cross-validation procedure was conducted in subsets of the same cohort rather than in separate training and validation data sets, so replication in larger and more diverse cohorts is needed.

This was a study to investigate the associations of lipids, categorized by lipid class, the number of carbons, and the number of unsaturated bonds, with circulating concentrations of fat-soluble vitamins and carotenoids. Except for lycopene, refinement of the lipidome beyond class did not further characterize the interindividual variability in these micronutrients. However, based on these analyses, future investigations of the role of PC/LPC in vitamin E and K metabolism are merited.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—JMK, GM, SLB, JMO, CES, and GSH: designed the research; SW and TJvdB: provided essential materials; JMK, GM, and TJvdB: analyzed the data; JMK and SLB: wrote the paper; JMK, SLB, and SW: had primary responsibility for the final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

Supported by the USDA Agricultural Research Service under Cooperative Agreement no. 581950-7-707 and in addition by DSM.

Author disclosures: the authors report no conflicts of interest.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA.

Supplemental Tables 1–4 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/cdn/.

Abbreviations used: ChE, cholesterol ester; DG, diglyceride; FFA, free fatty acid; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; sPLS, sparse partial least-squares; SPM, sphingomyelin; TG, triglyceride.

Contributor Information

Jennifer M Kelly, Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA.

Gregory Matuszek, Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA.

Tim J van den Broek, Research Group Microbiology & Systems Biology, Netherlands Institute for Applied Science (TNO), Zeist, Netherlands.

Gordon S Huggins, Center for Translational Genomics, Molecular Cardiology Research Institute, Tufts Medical Center and Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA.

Caren E Smith, Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA.

Jose M Ordovas, Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA.

Suzan Wopereis, Research Group Microbiology & Systems Biology, Netherlands Institute for Applied Science (TNO), Zeist, Netherlands.

Sarah L Booth, Email: sarah.booth@tufts.edu, Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- 1. Pfeiffer CM, Schleicher RL, Johnson CL, Coates PM. Assessing vitamin status in large population surveys by measuring biomarkers and dietary intake – two case studies: folate and vitamin D. Food Nutr Res. 2012;56:5944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schmölz L. Complexity of vitamin E metabolism. World J Biol Chem. 2016;7(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bohn T, Desmarchelier C, Dragsted LO, Nielsen CS, Stahl W, Rühl R, Keijer J, Borel P. Host-related factors explaining interindividual variability of carotenoid bioavailability and tissue concentrations in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61(6):1600685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stiles AR, Kozlitina J, Thompson BM, McDonald JG, King KS, Russell DW. Genetic, anatomic, and clinical determinants of human serum sterol and vitamin D levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(38):E4006–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kelly JM, Ordovas JM, Matuszek G, Smith CE, Huggins GS, Dashti HS, Ichikawa R, Booth SL. The contribution of lipids in vitamin K biomarker response to vitamin K supplementation. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63(24):1900399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Borel P, Desmarchelier C. Bioavailability of fat-soluble vitamins and phytochemicals in humans: effects of genetic variation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2018;38:69–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blomhoff R, Green MH, Berg T, Norum KR. Transport and storage of vitamin A. Science. 1990;250(4979):399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haddad JG, Matsuoka LY, Hollis BW, Hu YZ, Wortsman J. Human plasma transport of vitamin D after its endogenous synthesis. J Clin Invest. 1993;91(6):2552–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Desmarchelier C, Borel P. Overview of carotenoid bioavailability determinants: from dietary factors to host genetic variations. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2017;69:270–80. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Erkkilä AT, Lichtenstein AH, Dolnikowski GG, Grusak MA, Jalbert SM, Aquino KA, Peterson JW. Plasma transport of vitamin K in men using deuterium-labeled collard greens. Metabolism. 2004;53(2):215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Quehenberger O, Armando AM, Brown AH, Milne SB, Myers DS, Merrill AH, Bandyopadhyay S, Jones KN, Kelly S, Shaner RL. Lipidomics reveals a remarkable diversity of lipids in human plasma. J Lipid Res. 2010;51(11):3299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cox RA, Garcia-Palmieri MR. Cholesterol, triglycerides, and associated lipoproteins. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JWeditors. Clinical methods: the history, physical, and laboratory examinations. 3rd ed Boston (MA): Butterworths; 1990. pp. 153–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13. van den Broek TJ, Kremer BHA, Marcondes Rezende M, Hoevenaars FPM, Weber P, Hoeller U, van Ommen B, Wopereis S. The impact of micronutrient status on health: correlation network analysis to understand the role of micronutrients in metabolic-inflammatory processes regulating homeostasis and phenotypic flexibility. Genes Nutr. 2017;12(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bakker GC, van Erk MJ, Pellis L, Wopereis S, Rubingh CM, Cnubben NH, Kooistra T, van Ommen B, Hendriks H. An antiinflammatory dietary mix modulates inflammation and oxidative and metabolic stress in overweight men: a nutrigenomics approach. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(4):1044–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lauridsen C, Halekoh U, Larsen T, Jensen SK. Reproductive performance and bone status markers of gilts and lactating sows supplemented with two different forms of vitamin D. J Anim Sci. 2010;88(1):202–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aebischer C-P, Schierle J, Schuep W. Simultaneous determination of retinol, tocopherols, carotene, lycopene, and xanthophylls in plasma by means of reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:348–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davidson KW, Sadowski JA. Determination of vitamin K compounds in plasma or serum by high-performance liquid chromatography using postcolumn chemical reduction and fluorimetric detection. Methods Enzymol. 1997;282:408–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Card DJ, Shearer MJ, Schurgers LJ, Harrington DJ. The external quality assurance of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) analysis in human serum. Biomed Chromatogr. 2009;23(12):1276–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wopereis S, Rubingh CM, van Erk MJ, Verheij ER, van Vliet T, Cnubben NHP, Smilde AK, van der Greef J, van Ommen B, Hendriks H. Metabolic profiling of the response to an oral glucose tolerance test detects subtle metabolic changes. PLoS One. 2009;4(2):e4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Kloet FM, Bobeldijk I, Verheij ER, Jellema RH. Analytical error reduction using single point calibration for accurate and precise metabolomic phenotyping. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(11):5132–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lê Cao K-A, Boitard S, Besse P. Sparse PLS discriminant analysis: biologically relevant feature selection and graphical displays for multiclass problems. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Le Cao K-A, Rohart F, Gonzalez I, Dejean S, Gautier B, Bartolo F, Monget P, Coquery J, Yao F, Liquet B. mixOmics: omics data integration project. R package version 6.1.1. [Internet] 2016. Available from:https://bioconductor.org/packages/mixOmics/. Accessed May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tenenhaus M. La régression PLS: théorie et pratique. Paris (France): Editions Technic; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25. van der Veen JN, Kennelly JP, Wan S, Vance JE, Vance DE, Jacobs RL. The critical role of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine metabolism in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2017;1859(9):1558–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shearer MJ, Okano T. Key pathways and regulators of vitamin K function and intermediary metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2018;38:127–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nowicka B, Kruk J. Occurrence, biosynthesis and function of isoprenoid quinones. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(9):1587–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reboul E. Vitamin E bioavailability: mechanisms of intestinal absorption in the spotlight. Antioxidants. 2017;6(4):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Traber MG. Vitamin E and K interactions – a 50-year-old problem. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(11):624–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shea M, Booth S. Concepts and controversies in evaluating vitamin K status in population-based studies. Nutrients. 2016;8(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.