COVID-19, caused by a highly contagious newly identified type of coronavirus, has resulted in a myriad of prevention, care, and treatment challenges throughout the U.S. While people of all age groups are susceptible to the coronavirus, individuals living with comorbidities are at an increased risk of experiencing severe illness, morbidity, and mortality. Persons with substance use disorder (SUD), particularly persons who inject drugs (PWID), are at higher risk of suffering complications from COVID-19 due to poor pulmonary health from smoking and vaping practices, HIV and TB infection, and compromised immune systems. In addition, PWID face economic, social, and environmental challenges, such as homelessness, poverty, unemployment, food insecurity and incarceration that place them at increased risk of COVID-19 through community spread (Volkow, 2020). In addition, many prisons and jails are releasing people detained for non-violent offenses. Given that many jail detainees and prison inmates live with SUD, this population is especially vulnerable to increased overdose risk and other SUD-related harms. With the implementation of social distancing strategies, increased stress, anxiety, and resurgence of mental health comorbidities may exacerbate substance use at a time of reduced supply and resultant decreased quality of street drugs, as well as increased need for services among this vulnerable population. All these challenges and risk factors are likely to be worsened at the very moment when SUD prevention, treatment, and harm reduction services are seriously disrupted.

Syringe services programs (SSPs) are community-based programs that offer tailored social and medical services to PWID, including access to sterile and clean injection equipment, onsite and referrals to substance use treatment, HIV and Hepatitis C (HCV) testing, and overdose prevention through naloxone distribution. Currently, there are over 400 SSP locations across the United States (US) providing life-saving care to PWID. However, with the unprecedented developments regarding COVID-19, service delivery may be severely disrupted, and operational changes may be imperative to protect SSP staff and to ensure continuity of services. We provide preliminary data regarding SSP operational and service delivery changes during the US’ response to the COVID-19 global pandemic and provide key policy and service provision implications for SSPs.

A convenience sample of 82 SSPs in the U.S. was contacted via telephone to inquire about operational changes due to the COVID-19 outbreak. If selected sites did not respond, data were collected using publicly available sources, such as websites and social media accounts where SSPs distribute information to SSP clients. If select SSPs did not have regularly updated information publicly available or were unable to be reached by phone, they were excluded from the present analysis. In total, we collected data from 65 SSP sites from 33 states in the US, including 14 sites in New York City. Data regarding whether or not the SSP was still operating, changes in hours of operation, changes in syringe distribution method (e.g. fixed site, mobile unit, delivery), offering of HIV and HCV testing and what safety measures have been implemented to protect staff and clientele were recorded. COVID-19 prevention measures included social distancing and SSP staff wearing personal protection equipment (PPE) when engaging with participants. Data collection occurred over a one-week period between March 19 - 26, 2020.

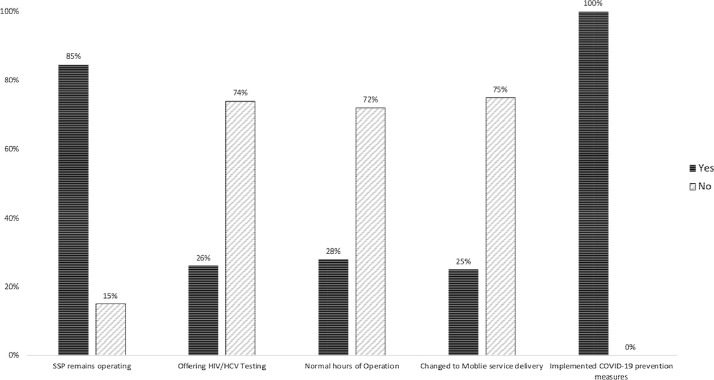

Of the 65 SSP sites, the majority of programs (84.6%) have remained open; however, 10 programs (15.4%) have discontinued all SSP operations due to COVID-19 and 16 (24.6%) have switched to mobile delivery of new injection equipment. The 10 SSP locations that discontinued services represented 9 different states, suggesting no geographical concentration of closures. All open sites have implemented COVID-19 prevention measures to protect SSP staff operating the programs and SSP participants. The majority of the programs that have remained open are operating under restricted hours of operation (72.3%). Only 17 (26.1%) programs have continued providing HIV/HCV testing onsite, with the majority discontinuing their medical services (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of syringe services programs providing syringe services, offering HIV/HCV testing, normal hours of operation, changed to mobile service delivery and implemented COVID-19 prevention measures.

Our data clearly emphasizes the disruption of services provided at SSPs and highlights the need for SSP support in providing education, prevention and strategies to avoid emerging infectious disease outbreaks. It is important to recognize that SSPs are often the setting that links PWID to primary care and is often the primary care site in communities throughout the US. For example, one study showed that the majority (76%) of 530 clients interviewed from 23 SSPs surveyed in California received the 10 recommended preventative services at their local SSP (Heinzerling et al., 2006). In another study, SSP participants reported they were able to access SSP services promptly and felt welcomed without judgment (Burr et al., 2014). Notably, many PWID are unable to access care or are unwilling to do so due to pervasive stigma within the traditional healthcare system, so emergency departments often are used as their care setting of last resort. SSPs remain on the frontlines in offering culturally competent healthcare to PWID. The World Health Organization affirms that SSPs need to be supported with a wide range of complimentary services in order to improve health outcomes of PWID (W.H.O., 2007)

Another important finding of our study is that the majority of SSPs have ceased their provision of HIV/HCV testing. Innovative strategies must be developed in order to provide HIV and HCV testing during the COVID-19 era of social distancing, including provisional temperature and symptom screenings for COVID-19 alongside rapid HIV/HCV testing. SSPs also offer a key venue for diagnosis and surveillance of COVID-19 in PWID. Along with testing, educating participants on the increased risks of overdose through disruptions and deterioration of the drug supply should include recommendations to cautiously increase personal supply in the case of a shortage, if this action is feasible due to personal use patterns and safety as well as legal ramifications. Needs-based syringe distribution to account for SSP service disruptions and provision of fentanyl testing strips and naloxone for overdose prevention are paramount. Social distancing guidance should include innovative strategies such as scheduling a phone check-in after use for people who are using alone. Lack of SSP services, particularly access to syringes and HIV/HCV testing, increases risk for silent HIV and HCV outbreaks, masked by the current COVID-19 pandemic. Integrating prevention through mask provision and health promotion through education, hand sanitizer, and food distribution, SSPs should be utilized in the agile public health response to COVID-19 in this vulnerable and underserved population, mitigating demand on overwhelmed hospital systems. In particular, we recommend implementation of telehealth delivery systems (e.g. buprenorphine, antiretroviral initiation) at SSP sites to reduce physical physician visits, maintain access to lifesaving medications, and prioritize meeting PWID where they are.

Author Contributions

TSB conceptualization and writing original draft, LRM and HET conceptualized the study. TSB contributed to the majority of the manuscript writing, including all drafts and revisions. NN assisted in data collection and analysis. LRM and HET directed study process. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration and Ethics

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami deemed this research not human subjects because it was conducted for the purpose of informing program operational policies at the Miami SSP (IRB#20200387) under the Florida State of Emergency.

Declaration of Competing Interests

None

Acknowledgments

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami deemed this research not human subjects because it was conducted for the purpose of informing program operational policies at the Miami SSP (IRB#20200387) under the Florida State of Emergency.

References

- Burr C.K., Storm D.S., Hoyt M.J., Dutton L., Berezny L., Allread V., Paul S. Integrating health and prevention services in syringe access programs: a strategy to address unmet needs in a high-risk population. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(1_suppl1):26–32. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzerling K.G., Kral A.H., Flynn N.M., Anderson R., Scott A., Gilbert M., Bluthenthal R.N. Unmet need for recommended preventive health services among clients of California syringe exchange programs: implications for quality improvement. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81(2):167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.008. . . . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W.H. (2007). Guide to starting and managing needle and syringe programmes.

- Volkow N.D. Collision of the COVID-19 and Addiction Epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/m20-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]