Abstract

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a member of the neurotrophin growth factor family, well known for its role in the homeostasis of the cardiovascular system. Recently, the human BDNF Val66Met single nucleotide polymorphism has been associated with the increased propensity for arterial thrombosis related to acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and immunohistochemistry analyses, we showed that homozygous mice carrying the human BDNF Val66Met polymorphism (BDNFMet/Met) undergoing left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery ligation display an adverse cardiac remodeling compared to wild-type (BDNFVal/Val). Interestingly, we observed a persistent presence of pro-inflammatory M1-like macrophages and a reduced accumulation of reparative-like phenotype macrophages (M2-like) in the infarcted heart of mutant mice. Further qPCR analyses showed that BDNFMet/Met peritoneal macrophages are more pro-inflammatory and have a higher migratory ability compared to BDNFVal/Val ones. Finally, macrophages differentiated from circulating monocytes isolated from BDNFMet/Met patients with coronary heart disease displayed the same pro-inflammatory characteristics of the murine ones. In conclusion, the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism predisposes to adverse cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction in a mouse model and affects macrophage phenotype in both humans and mice. These results provide a new cellular mechanism by which this human BDNF genetic variant could influence cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, myocardial infarction, macrophage phenotype, cardiovascular disease

1. Introduction

Neurotrophins are a family of proteins well known for their critical role in the development, maintenance, and plasticity of the neurons [1] as well as of the heart and vasculature tissue development [2,3,4]. Among the members of this family of proteins, particular attention has been paid to the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a key regulator of homeostasis and pathogenesis of the cardiovascular system [5,6]. BDNF triggers the activation of endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and monocyte/macrophages [7,8,9,10], and promotes cardiac microvasculature development and dynamics [4,11,12], suggesting its important role in orchestrating the mechanisms of repair after myocardial infarction (MI) [10].

Low circulating BDNF levels were associated with future coronary events and mortality in angina pectoris patients [13] and with heart failure biomarkers and adverse left ventricular (LV) cardiac remodeling [14]. Moreover, in different mouse models, low BDNF levels affect cardiac remodeling [15] and are associated with reduced ejection fraction and vascularization of the border zone of the infarcted region [16]. Okada et al. [16] provided evidence that these effects are independent of the cardiomyocyte-specific ablation of BDNF but mainly related to circulating BDNF and its cerebral output. BDNF, in addition to its ability to favor angiogenesis, promotes the shift of macrophage phenotype from M1 to M2 with consequent modification of inflammatory microenvironment [9] and, potentially, with an improvement of cardiac function after MI.

In humans, the presence of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the BDNF gene, leading to valine to methionine substitution at position 66 in the prodomain region of the BDNF protein (BDNF Val66Met) determines the reduction of cerebral BDNF levels [17], and it is related to mood disorders and neurodegenerative diseases [18]. Several studies investigated the potential implications of this mutation in the context of cardiovascular diseases, but their results were controversial [19,20,21]. We showed that Met homozygosity is associated with arterial thrombosis in a knock-in mouse model and with increased risk of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in humans [21]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine, in a mouse model carrying the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, the impact of the mutation on cardiac remodeling after MI focusing on the characterization of macrophage phenotype. Besides, to support the potential relevance of the data obtained in the animal model we analyzed the macrophages spontaneously differentiated from monocytes isolated from homozygous Val or Met human carriers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Studies

BDNF Val66Met mice [22] were generated by heterozygous BDNF Val/Met interbreeding and offspring were genotyped by PCR analysis of tail tip-derived genomic DNA. Animal studies were in conformity with the European ethics legislation and approved by the Italian National Ministry of Health (375-2017PR and 270-2019PR). All procedures were performed in 10–12-week-old wild-type control (BDNFVal/Val) or BDNFMet/Met mice. Surgical procedures were performed in mice anesthetized with ketamine chlorhydrate (75 mg/kg; Intervet, Segrate, Milan, Italy) and medetomidine hydrochloride (1 mg/kg; Virbac, Milan, Italy).

2.2. Left Anterior Descending (LAD) Coronary Artery Ligation Model

As previously described [23], MI was induced in anesthetized mice by ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery using a 7-0 silk suture through left thoracotomy under anesthetized mice and mechanical ventilation. Successful ligation was verified by visual inspection of the left ventricular (LV) apex for myocardial blanching, indicating interruption of the coronary blood flow. Atipamezole (0.5 mg/kg, Virbac, Milan, Italy) was administered to encourage animal awakening, and then the animals were extubated and monitored.

Based on our previous data [24], infarcted mice with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LV EF), within the range 35–45%, obtained by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) at 24 h, were included into the study and randomized into two different experimental protocols as follows.

Protocol 1. The impact of BDNFVal66Met polymorphism on cardiac remodeling following MI was evaluated on BDNFVal/Val and BDNFMet/Met mice. Mice were longitudinally examined before LAD ligation (baseline) and 24 h, 1, 4, and 8 weeks after surgery by cMRI in order to evaluate LV parameters. After the last cMRI visualization, mice were euthanized and cardiac tissue collected for histological analyses.

Protocol 2. The implication of macrophage polarization in cardiac remodeling following MI was evaluated on BDNFVal/Val and BDNFMet/Met sacrificed at 3, 5, and 7 days after MI.

2.3. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Mice were anesthetized with inhaled 1% isoflurane (Merial, Toulouse, France) in 100% oxygen, fixed on a holder and placed into the 3.8-cm coil. The temperature was monitored rectally. The images were acquired using a 4.7T vertical-bore MR magnet (Bruker, Germany) and a retrospective gated cine gradient echo sequence with the following parameters: Echo time (TE) 1.9 ms, repetition time (TR) 10 ms, field of view 4 × 4 cm2, acquisition matrix 128 × 128 pixels, slice thickness 1.3 mm, 6–8 axial slices spaced 1 mm to fully cover the LV.

The magnetic resonance images were analyzed using custom software implemented in Python environment along the lines [24] in order to obtain end-diastolic (LV EDV), end-systolic (LV ESV), and stroke volumes (LV SV); ejection fraction (LV EF); and ventricular mass (LV mass).

2.4. Tissue Collection and Section Preparation

In order to prepare specimens for histological analysis, the abdominal aorta was cannulated and the heart was arrested in diastole, with 2 mL of a solution of 0.1 M CdCl2 and 1 M KCl, and retrogradely perfused with 0.01 M phosphate saline buffer (PBS) and then with 4% (v/v) phosphate-buffered formalin for 10 min each. Hearts were collected and tissues post-fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin for 24 h and embedded in paraffin. Consecutive 8-µm heart axial (along the apex-basis axis) sections were prepared.

2.5. Determination of Infarct Size and Cardiomyocytes’ Cross-Sectional Area

MI size was determined on LV axial section (one for each millimeter of LV). To define the infarct lengths, endocardial infarct length was taken as the length of endocardial infarct scar surface that included greater than 50% of the whole thickness of myocardium, and epicardial infarct length as the length of the transmural infarct region. Epicardial infarct ratio was obtained by dividing the sum of epicardial infarct lengths from all sections by the sum of epicardial circumferences from all sections. Endocardial infarct ratio was calculated similarly. Infarct size derived from this approach was calculated as ((epicardial infarct ratio + endocardial infarct ratio)/2) × 100 [25].

For collagen staining, heart sections were incubated in 0.1% Sirius red solution (Direct Red 80, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), mounted with DPX (Distyrene and xylene) mountant for microscopy, and images acquired with a high-resolution digital camera using 1:1 macro-lens. Myocytes’ cross-sectional area (MCSA) was measured on 3 tissue sections from each heart stained with germ agglutinin–Alexa Fluor 488, incubated with Hoechst 33258 nuclear stain (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), and then mounted using fluorescence mounting medium (Dako, Milan, Italy). Images from the non-infarcted region (222 μm x 166 μm) were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 200, Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Cross-sectional area of 100–150 cardiomyocytes from each mouse was measured on transversally sectioned cells with circularity greater than 0.6 and round nuclei. All quantitative analyses were performed in blind using Photoshop CS6 (Adobe System) or Image J (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.6. Cardiac Macrophage Extraction and Flow Cytometer Analysis

Hearts were collected from mice 3, 5, or 7 days after LAD ligation. Macrophages were isolated from the heart following a previously published protocol [26]. Briefly, tissue was minced in small pieces (2–3 mm length) and digested with 600 U/mL collagenase II and 10 U/mL DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) in Hanks buffered saline solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and filtered through a 30-µm separation filter to generate a single-cell suspension. Macrophages were isolated after gradient centrifugation at the interphase between 35% and 70% Percoll solutions (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), then washed with PBS, permeabilized, and stained with the following fluorophore-conjugated antibodies: CD206-APC (eBioscience-Thermo Fisher, Paisley, Scotland, UK), CD68-PE (eBioscience-Thermo Fisher, Paisley, Scotland, UK), and CD11c-FITC (eBioscience-Thermo Fisher, Paisley, Scotland, UK). Nonspecific staining was eliminated, incubating the same number of cells as in the surface markers’ antibody tube with isotype control antibody, matched to the surface marker antibody’s host species and class. Samples were analyzed by NovoCyte flow cytometer (ACEA Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) and the percentage of positive cells was compared with fluorescence-labeled isotype controls. A minimum of 10,000 events was collected in the CD68+ gate by flow cytometry.

2.7. Mouse Peritoneal Macrophage Isolation

Seventy-two hours after thioglycollate broth injection, macrophages were harvested from the peritoneum with ice-cold PBS, centrifuged, and suspended in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin (100 U/mL each) (Gibco, Rodano, Milan, Italy) and plated as previously described [27]. After one hour, plates were washed and adherent cells were left for four hours in DMEM medium after which they were lysed TRIzol Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) or within RIPA (Radioimmunoprecipitation assay) buffer (1% Triton X-100 in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5) plus 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM benzamidine, and 1 mM sodium vanadate, all from Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA. After incubation on ice for 1 h, the lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min for BDNF detection and frozen for further analyses.

2.8. BDNF Analysis

BDNF was measured by commercial Emax Immunoassay system kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in whole macrophages’ extract lysed in RIPA buffer.

2.9. Migration Assay

Boyden chamber assay. Cell migration under unstimulated conditions and in response to a migratory factor was assessed by using a 48-well microchemotaxis Boyden chamber [28]. Briefly, triplicate wells of the lower part of the microchemotaxis chamber were filled with DMEM (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) with 0.2% BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) ± 20 ng/mL MCP-1 (Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1) (Thermo Fisher, Paisley, Scotland, UK). A 5-µm pore diameter polycarbonate membrane coated with collagen was placed on the top and the chamber was tightened. Peritoneal macrophages (1 × 105 cells) were added to the upper wells for 3 h at 37 °C. The membrane was then removed, adherent cells on the top were eliminated, and the membrane was stained with Diff-Quik reagents. Each test group was assayed in at least 3 replicates and pictures of typical fields were taken under high-power light microscopy. Migrated cells were evaluated by blind counting cells in 12 random fields for each experimental group with the Image J software.

The agarose spot migration assay was adapted from Ahmed et al. [29]. Ten µL of low-gelling temperature agarose (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) containing vehicle, LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) (10 ng/mL), or MCP-1 (20 ng/mL) (Thermo Fisher, Paisley, Scotland, UK) were put on the surface of a microscope glass slide coated with gelatin. Then, 5 × 105 macrophages were seeded on every microscope glass slide with DMEM medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin (100 U/mL each), non-adherent cells were washed with PBS after 1 h, and macrophages were allowed to migrate for 24 h in DMEM medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin (100 U/mL each) (Gibco, Rodano, Milan, Italy) and 10% of serum (Euroclone, Pero, Milan, Italy). Photos were taken using a 5 × magnification with a Zeiss Axioskop (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with an intensified charge-coupled device (CCD) camera system (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA). The number of migrated macrophages was determined by blind counting cells in 8 random fields for each experimental group.

2.10. Human Studies

Homozygous BDNFVal/Val and BDNFMet/Met carriers (age 50–80 y) were identified within a large set of male patients with a clinical history of stable angina or acute coronary syndrome followed by coronary artery bypass graft surgery, previously genotyped by our group for the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism [21]. Patients were matched for genotype, age clinical presentation of coronary heart disease as stable and unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction, and pharmacological treatments. All the patients were under aspirin and statins, one patient per group was under anticoagulant, and 92% of BDNFVal/Val patients and 71% of BDNFMet/Met patients were under beta-blockers. After selected candidates provided written informed consent, a detailed anamnesis and physical examination were carried out and venous blood was obtained at fasting from an antecubital vein. The study complied with the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethical Committee of Centro Cardiologico Monzino IRCCS (Istituto di ricovero e cura a carattere scientifico) (R455/16-CCM 471). Human mononuclear cells were separated from venous blood by centrifugation on Ficoll-Paque Plus (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) density gradient, and monocytes were isolated by selective adhesion [30]. Monocyte to macrophage differentiation was obtained by cultivating monocytes in Medium 199 (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with l-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin (all from Gibco, Rodano, Milan, Italy), and 10% of autologous serum at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for seven days, as previously described [31].

2.11. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

Total cellular RNA was isolated from human and murine macrophages using TRIzol Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and a Direct-zol RNA extraction kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using the iScript Advanced cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Segrate, Milan, Italy).

Samples of cDNA were incubated in 15 µL Luna® Universal qPCR mix containing the specific primers and fluorescent dye SYBR Green (New England Biolabs, Pero, Milan, Italy). RT-qPCR was carried out in triplicate for each sample on the CFX Connect real-time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Segrate, Milan, Italy), as previously described [32]. Gene expression was analyzed using parameters available in CFX Manager Software 3.1 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Segrate, Milan, Italy). Then, qPCR was carried out using the primer sequences shown in Table S1.

2.12. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software (San Diego, CA, USA). Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test or by 2-way-ANOVA (with repeated measures when necessary) for main effects of treatment, time, and genotype, followed by a Bonferroni post hoc analysis. p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data represent mean ± SEM. All human performed analyses were adjusted for age and drug treatments.

3. Results

3.1. BDNF Val66Met Polymorphism Affects Left Ventricle Remodelling After LAD Ligation

To establish the effect of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism in heart remodeling after MI, the BDNFVal/Val and homozygous BDNFMet/Met mice underwent left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery ligation, and cardiac morphology and function were assessed by cMRI at 24 h and 1, 4, and 8 weeks after surgery. At baseline, BDNFVal/Val and BDNFMet/Met mice displayed normal and comparable heart parameters (Table 1).

Table 1.

Left ventricular (LV) parameters obtained by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) analysis.

| Genotype | Time | Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (cMRI) Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV EF (%) | LV EDV (µL) | LV ESV (µL) | LV Mass (mg) | ||

| BDNFVal/Val | baseline | 67.5 ± 1.7 | 47.2 ± 3.3 | 15.6 ± 1.7 | 82.3 ± 3.1 |

| 24 h | 37.2 ± 1.8 | 59.9 ± 4.7 | 37.4 ± 2.8 | 72.2 ± 3.8 | |

| 1 week | 36.9 ± 1.8 | 71.7 ± 5.9 | 45.1 ± 3.9 | 88.0 ± 6.5 | |

| 4 weeks | 36.1 ± 2.2 | 92.1 ± 4.5 | 59.1 ± 4.2 | 84.8 ± 3.3 | |

| 8 weeks | 31.8 ± 2.9 | 91.0 ± 6.6 | 62.7 ± 6.3 | 89.2 ± 3.8 | |

| BDNFMet/Met | baseline | 69.9 ± 2.4 | 43.7 ± 2.3 | 13.5 ± 1.7 | 80.8 ± 3.5 |

| 24 h | 36.2 ± 1.1 | 73.1 ± 1.8 | 46.7 ± 1.7 | 82.8 ± 3.5 | |

| 1 week | 33.5 ± 3.1 | 97.5 ± 7.2 | 66.5 ± 7.1 | 97.6 ± 3.1 | |

| 4 weeks | 26.0 ± 2.4 * | 128.0 ± 12.9 * | 96.9 ± 11.8 ** | 95.6 ± 3.8 | |

| 8 weeks | 25.5 ± 2.5 | 140.2 ± 13.3 *** | 107.1 ± 13.0 *** | 104.1 ± 3.8 * | |

BDNFVal/Val: N = 7 mice, BDNFMet/Met: N = 10 mice; LV: left ventricular; EF: ejection fraction; EDV: end-diastolic volume; ESV: end-systolic volume. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 vs BDNFVal/Val.

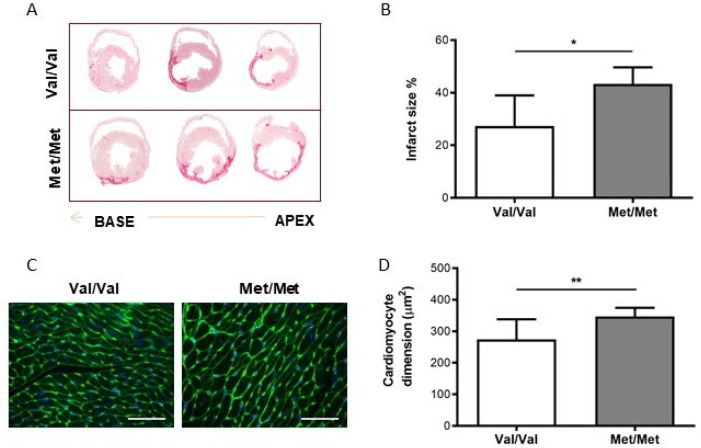

As a consequence of MI, 24 h after LAD ligation an important reduction of left ventricular ejection fraction (LV EF%) was observed in both experimental groups (BDNFVal/Val: −45 ± 2%, BDNFMet/Met: −47 ± 2%). Although BDNFMet/Met mice showed an increase of left ventricle end-diastolic and systolic volumes compared to BDNFVal/Val group (LV EDV: BDNFVal/Val: +27 ± 5%; BDNFMet/Met: +70 ± 7% and LV ESV: BDNFVal/Val: +149 ± 17%; BDNFMet/Met: +294 ± 48%), no significant difference in the cMRI parameters was detected either at 24 h or 1 week after LAD ligation. Four weeks after surgery, BDNFMet/Met mice displayed a significant increase in LV EDV and LV ESV compared to BDNFVal/Val (p < 0.05 for LV EDV and p < 0.01 for LV ESV) with a concurrent LV EF% reduction (p < 0.05). The LV EDV and the LV ESV differences were maintained until 8 weeks after LAD ligation, when also a significant increase of LV mass was observed in BDNFMet/Met (p < 0.05) (Table 1). At the same time point, histological examination showed that BDNFMet/Met mice have a larger infarct size % (p < 0.05) (Figure 1A,B) and a greater myocyte cross-sectional area (MCSA) in non-infarcted left ventricular regions (p < 0.05) than BDNFVal/Val mice (Figure 1C,D).

Figure 1.

Characterization of the infarcted hearts isolated from BDNFVal/Val (Val/Val) and BDNFMet/Met (Met/Met) mice. (A) Representative photomicrographs of infarct size evaluated from the base (left) to the apex (right) by Sirius red staining measured at 8 weeks after surgery. (B) Infarct size expressed as percentage of the length of the infarct scar on the LV total circumferential length. (C) Representative immunofluorescence (40×, scale bar: 50 µm) and (D) measurement of myocyte cross-sectional area (MCSA) in the remote left ventricle (LV). N = 6/group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

3.2. BDNF Val66Met Polymorphism Affects the Physiological Accumulation of M1- and M2-Like Macrophages after LAD Ligation

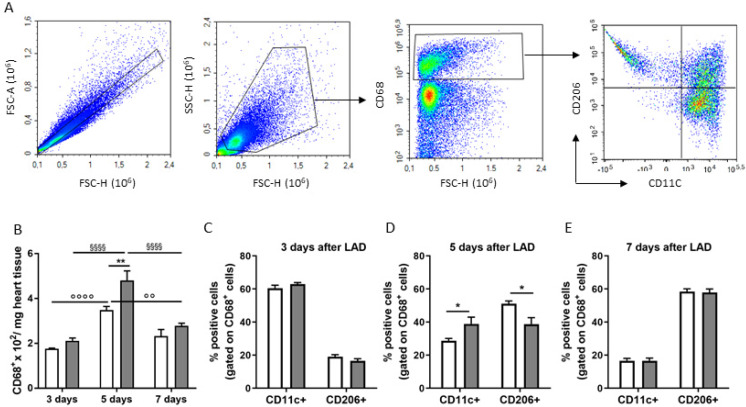

Ischemia triggers the accumulation of macrophages that plays a fundamental role in post-MI damage and in the subsequent cardiac remodeling [33]. Indeed, it is well known that the macrophage phenotype regulates the inflammatory phase and influences the reparative phase favoring collagen deposition and scar formation. Then, we profiled macrophages’ accumulation in the myocardium and we investigated the cardiac macrophage subsets at 3, 5, and 7 days after MI.

The infarct induced, in both BDNFVal/Val and BDNFMet/Met mice, the accumulation of macrophages (CD68+ cells), which peaked on day 5. Of note, at day 5, infarcted BDNFMet/Met heart accumulated a greater number of macrophages compared to BDNFVal/Val (Figure 2A,B), suggesting a prolonged recruitment of macrophages in the heart of mutant mice.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analyses (FACS) of macrophages isolated at a different time point (3, 5, and 7 days) after the induction of myocardial infarction in BDNFVal/Val (white bar graph) and BDNFMet/Met (grey bar graph) mice. (A) Representative FACS plots showing the gating strategy for CD11c+ (CD11c+/CD68+) and CD206+ (CD206+/CD68+). Quantification of macrophage subsets according to the expression of (B) CD68 positive cells, CD206, and CD11c positive cells at (C) 3, (D) 5, (E) 7 days after LAD. N = 6/group/time; * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 BDNFVal/Val vs. BDNFMet/Met; °° p < 0.01 and °°°° p < 0.001 BDNFVal/Val comparison at different time points; §§§§ p < 0.001 BDNFMet/Met comparison at different time points.

According to the literature, we found a progressive reduction in classically activated macrophages (CD11c+/CD68+, pro-inflammatory M1-like) associated with a concomitant increase in alternatively activated macrophage markers (CD206+/CD68+, M2-like) from day 3 to day 7 after LAD ligation (Figure 2C–E) in BDNFVal/Val mice.

Remarkably, on day 5, BDNFMet/Met mice still showed a persistent presence of CD11c+/CD68+ macrophages and, of consequence, a reduced accumulation of CD206+/CD68+ macrophages, compared to BDNFVal/Val (Figure 2C–E).

3.3. BDNF Mutation Influences Murine Macrophage Polarization

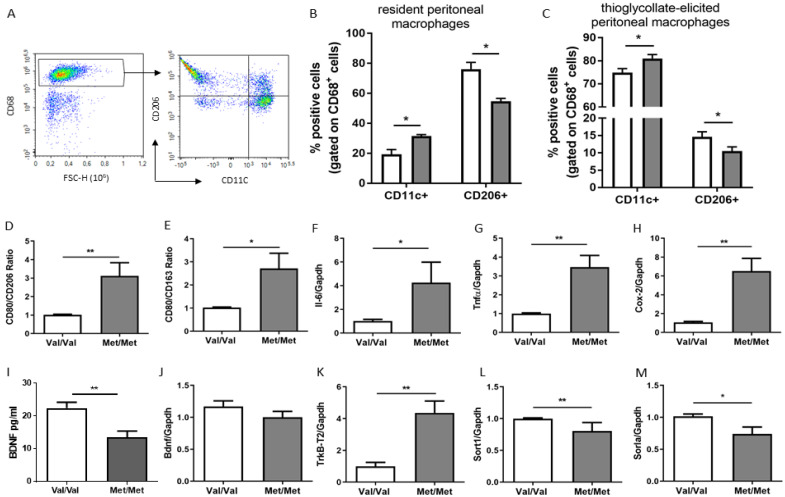

To assess whether the BDNF Val66Met affects macrophage polarization, in vitro studies were performed in resident and thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages isolated from BDNFVal/Val and BDNFMet/Met mice.

Flow cytometry analysis revealed a higher number of CD11c+ and lower abundance of CD206+ in cells isolated from BDNFMet/Met when compared to BDNFVal/Val in both resident and thioglycolate-elicited macrophages (Figure 3A–C). In addition, BDNFMet/Met thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages expressed significantly higher levels of marker CD80 (BDNFVal/Val: 1.03 ± 0.02 vs. BDNFMet/Met: 1.35 ± 0.16, p < 0.05) and lower levels of alternatively activated macrophage markers CD206 (BDNFVal/Val: 1.02 ± 0.01 vs. BDNFMet/Met: 0.63 ± 0.16, p < 0.05) and CD163 (BDNFVal/Val: 1.00 ± 0.001 vs. BDNFMet/Met: 0.58 ± 0.08, p < 0.001), with an increase in the CD80/CD206 and CD80/CD163 ratio (Figure 3A,B). The abnormal ratio in classically/alternatively activated macrophage markers detected in mutant macrophages was associated with a greater expression of inflammatory cytokines (Figure 3F–H) that well reflected their predominant pro-inflammatory (M1-like) phenotype.

Figure 3.

Characterization of peritoneal macrophages isolated from BDNFVal/Val (Val/Val, white bar graph) and BDNFMet/Met (Met/Met, grey bar graph) mice. (A) Representative FACS plots showing the gating strategy for CD11c+ (CD11c+/CD68+) and CD206+ (CD206+/CD68+). Quantification of (B) resident and (C) thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophage according to the expression of CD206 and CD11c positive cells. The mRNA expression levels of genes related to (D,E) classically/alternatively activated macrophage marker ratio, (F,G,H) inflammatory genes (Il-6, Tnf-α, and Cox-2), (J) Bdnf, and (K) TrkB-T2, and (L,M) genes involved in its sorting (Sort1 and Sorla). (I) BDNF levels detected by ELISA assay. N = 6 mice/group, * p < 0.05, and ** p < 0.01.

Interestingly, BDNF Val66Met polymorphism reduced the levels of BDNF in macrophages (Figure 3I) without affecting its mRNA levels (Figure 3J), and increased the expression of its specific receptor TrkB-T2 (Figure 3K). In addition, a significant reduction of both Sort1 and Sorl1, known to mediate the trafficking and sorting of TrkB receptors of BDNF, were found in mutant macrophages (Figure 3L,M).

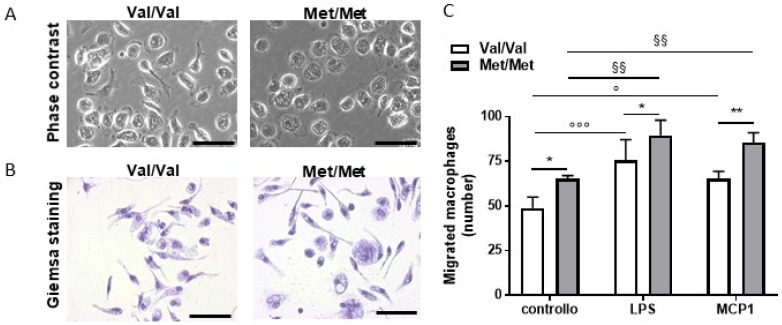

3.4. BDNFVal66Met Polymorphism Affects Murine Macrophages’ Shape and Migratory Ability

As previously described in several studies [34], here we observed that the pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype was associated with morphological and functional changes. In particular, the microscopic examination of macrophages showed that cells isolated from BDNFMet/Met mice exhibited mainly a round morphotype compared to BDNFVal/Val that, in turn, were prevalently spindle/elongated (Figure 4A,B).

Figure 4.

Morphology and functionality of BDNFVal/Val (Val/Val) and BDNFMet/Met (Met/Met) peritoneal macrophages. (A) Representative images of phase-contrast microscopy and (B) Giemsa staining, 40×, scale bar: 50 µm. (C) Migratory ability analyzed by agarose spot migration assay. N = 4 independent experiments; * p < 0.05, and ** p < 0.01 Val/Val vs. Met/Met; ° p < 0.05 and °°° p < 0.005 vs. BDNFVal/Val control macrophages; §§ p < 0.001 vs. BDNFMet/Met control macrophages.

In addition, in vitro cell migration studies showed that elicited BDNFMet/Met macrophages displayed a higher migratory ability compared to BDNFVal/Val (Figure 4C and Figure S1). This increase still remained significantly different both in response to MCP-1 and after LPS stimulation, providing evidence of a broad migratory alteration induced by the presence of this mutation (Figure 4C and Figure S1).

3.5. Effect of BDNFVal66Met Polymorphism on Human Macrophages Phenotype

Finally, we compared the phenotype of monocyte-derived macrophages isolated from BDNFVal/Val and BDNFMet/Met coronary artery disease (CAD) patients representing the subset of the same cohort of CAD patients previously analyzed [21].

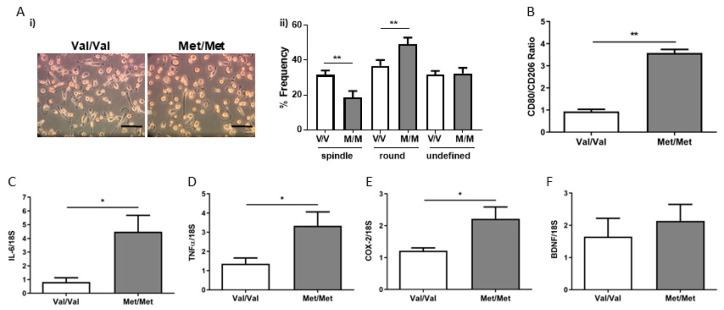

As observed in mouse peritoneal macrophages, the macrophage obtained from BDNFMet/Met subjects showed a higher percentage of round morphotype, while BDNFVal/Val macrophages had a prevalently elongated/spindle shape (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Characterization of BDNFVal/Val (Val/Val, white bar graph) and BDNFMet/Met (Met/Met, grey bar graph) human macrophages. (A) (i) Bright field representative images (20×, scale bar: 50 µm) and (ii) frequency in round, spindle, and undefined human macrophages. (B) mRNA levels of genes related to M1/M2 markers ratio, (C–E) inflammatory genes (IL-6, TNF-α, and COX-2) and (F) BDNF. N = 13/14 patient genotype/group, * p < 0.05, and ** p < 0.01.

In addition, in the presence of the mutation, we observed an increase in the transcript level of CD80 (BDNFVal/Val: 1.00 ± 0.26; BDNFMet/Met: 3.52 ± 0.87, p < 0.05) and lower levels of CD206 (BDNFVal/Val: 1.10 ± 0.20; BDNFMet/Met: 0.28 ± 0.08, p < 0.01) with an increase in the CD80/CD206 ratio (Figure 5B). Finally, BDNFMet/Met human macrophages expressed a significantly higher level of inflammatory genes (Figure 5C–E). As showed above in mouse macrophages, the BDNF mRNA levels were similar between Met and Val carrier patients (Figure 5F).

4. Discussion

Despite the advances in prevention and treatment, cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the world, with an estimated 23.3 million deaths by 2030 [35]. Among the pathologies, myocardial infarction represents a major burden since it might result in heart failure if it does not prove fatal immediately.

In the present study, using the humanized BDNF Val66Met homozygous knock-in mice, we found that the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism predisposes to adverse cardiac remodeling with a persistent presence of pro-inflammatory macrophages and a reduced accumulation of reparative macrophage phenotype in the infarcted heart.

The macrophage population in mouse ischemic heart was heterogeneous and changes during the time after the event. In particular, pro-inflammatory (M1) macrophages were dominant at day 1–3 post-MI, whereas reparative (M2) macrophages represented the majority between days 5–7 [36]. Indeed, the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages played a key role in the first step after damage, releasing several inflammatory factors, including cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and Matrix metallopeptidases (MMPs), in order to clear the damaged area from cell debris and degrade the extracellular matrix [37]. The anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages were involved in the reparative processes, they produced anti-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic, and pro-reparative factors in order to facilitate neo-angiogenesis and scar repair [38].

The correct temporal window during which pro-inflammatory or reparative macrophages are present in the infarcted area is fundamental for the correct process of cardiac remodeling, improving myocardial repair, and function post-MI [37]. The persistence of pro-inflammatory macrophages for a prolonged period can lead to the expansion of infarct size and to a delayed resolution of inflammation [39]. Thus, extensive matrix degradation, compromised ventricular wall integrity, cardiac rupture, and fibrosis are followed by impaired systolic function, chamber dilation, and ventricular hypertrophy [40]. Therefore, the adverse cardiac remodeling observed in BDNFMet/Met mice could well be traced back to the persistent presence of pro-inflammatory, rather than reparative, macrophages after MI. However, we cannot exclude that other leukocyte populations might affect adverse cardiovascular remodeling in BDNFMet/Met mice. Here, we showed that mutation improves M1-like polarization. However, at day 3 post-MI, no difference between the two groups was observed, suggesting that the presence of a highly inflammatory cardiac environment has the same impact on the polarization of both BDNFVal/Val and BDNFMet/Met macrophages. In addition, mutation prevents an appropriate M2-like polarization. Interestingly at day 5 post-MI (when M2 phenotype starts to be favored), the difference between genotypes occurs, suggesting a likely defect to induce a proper M2 polarization. Specific studies must be carried out to unravel this important issue.

Interestingly, a similar macrophage shift was recently observed also in the epidydimal adipose tissue of BDNFMet/Met mutant mice, where macrophages expressed higher levels of pro-inflammatory marker CD80 compared to BDNFVal/Val mice [32], suggesting that this mutation might predispose macrophages to a pro-inflammatory phenotype in different tissues and experimental conditions.

In line with the in vivo model, ex vivo studies showed that the Met mutation predisposes to M1-like phenotype. Indeed, according to the definition of M1 or M2 macrophage phenotype [41], both human and mouse BDNFMet/Met macrophages displayed a higher ratio between CD80 and CD163 and/or CD206 markers, greater levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α, and lower levels of TGF-β and IL-10, and increased migratory ability than BDNFVal/Val macrophages. In addition, the abnormal ratio between round and spindle macrophages observed in Met carriers well reflects this phenotype. Actually, round macrophages are characterized by genes encoding for the pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (CCR2+), showing an M1-like pro-inflammatory phenotype. On the contrary, spindle-shaped macrophages overexpress IL-10 and TGFβ, typical of M2 anti-inflammatory/reparative (CCR2−) macrophages, and possess wound repair ability [42].

After MI, the damaged cardiac tissue was able to initiate an influx of CCR2+ macrophages that produce pro-inflammatory cytokines [43,44], displaying an M1-like phenotype. Interestingly, suppression of the CCR2 receptor activity by specific siRNA and inhibition of CCR2+ macrophage recruitment in the ischemic area significantly reduced infarct size in mouse models and concomitantly decreased MCP-1, IL-1-β, IL-6, and TNF-α expression [39,42,45]. In contrast, depletion of resident cardiac CCR2- macrophages in a murine model of myocardial infarction increased infarct area, reduced LV systolic function, and exaggerated LV remodeling [42]. Therefore, the migration of circulating monocytes and resident macrophages to the damaged area plays a key role in the subsequent cardiac remodeling. In this regard, future studies will be necessary to establish the specific contribution of circulating monocytes and resident macrophages as well as the role of the cardiac environment in this animal model.

For the first time, we provided evidence that the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism affects the macrophage phenotype in both an animal model and in humans. In particular, macrophages spontaneously differentiated from BDNFMet/Met patients displayed an inflammatory M1-like phenotype, despite that the patients were under treatment with statins. Indeed, it is well known that these compounds, beyond their strong lipid-lowering effect, polarize the macrophages’ phenotype toward M2, decreasing their inflammatory profile [46,47,48]. Thus, our data suggest that statin treatment may not be sufficient to counteract the inflammatory macrophage phenotype of BDNFMet/Met patients. Based on these data, we can speculate that a phenotypic alteration in BDNFMet/Met macrophages might affect the onset and progression of cardiovascular disease; although, it will be important to confirm all the modifications observed in mutant mouse macrophages also in human.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, these results provide new insights into the already well-established role of BDNF in the cardiovascular system, suggesting a new cellular mechanism by which the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism could affect pathological cardiovascular conditions. Further studies are necessary to transfer this information into daily clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Simonelli for collecting human biological samples, and G.I. Colombo for patient genotyping.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/9/5/1084/s1. Figure S1: Migratory ability of peritoneal macrophages in Boyden chamber assay. Table S1: Primer sequences of the analyzed genes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.B.; formal analyses and data curation, L.S. (Leonardo Sandrini), L.C., P.A., M.Z., and S.S.B.; investigation, L.S. (Leonardo Sandrini), L.C., P.A., S.F., S.C., and S.E.; patient recruitment, J.P.W., who also contributed to the discussion on the results from a biological point of view, review, and editing; S.B., L.S. (Luigi Sironi), F.S.L., S.B., J.P.W., and E.T.; supervision and funding acquisition, S.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente) grants number RC 2018 MPP1.2A-ID 2634597, RC 2019 MPP 2B—ID 2755316. Co-funding provided by the contribution of the Italian “5 × 1000” tax (2015 and 2016), and Cariplo Foundation (2018-0525).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gonzalez A., Moya-Alvarado G., Gonzalez-Billaut C., Bronfman F.C. Cellular and molecular mechanisms regulating neuronal growth by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2016;73:612–628. doi: 10.1002/cm.21312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donovan M.J., Hahn R., Tessarollo L., Hempstead B.L. Identification of an essential nonneuronal function of neurotrophin 3 in mammalian cardiac development. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:210–213. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tessarollo L., Tsoulfas P., Donovan M.J., Palko M.E., Blair-Flynn J., Hempstead B.L., Parada L.F. Targeted deletion of all isoforms of the trkC gene suggests the use of alternate receptors by its ligand neurotrophin-3 in neuronal development and implicates trkC in normal cardiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:14776–14781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donovan M.J., Lin M.I., Wiegn P., Ringstedt T., Kraemer R., Hahn R., Wang S., Ibañez C.F., Rafii S., Hempstead B.L. Brain derived neurotrophic factor is an endothelial cell survival factor required for intramyocardial vessel stabilization. Development. 2000;127:4531–4540. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.21.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pius-Sadowska E., Machaliński B. BDNF—A key player in cardiovascular system. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2017;110:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amadio P., Porro B., Sandrini L., Fiorelli S., Bonomi A., Cavalca V., Brambilla M., Camera M., Veglia F., Tremoli E., et al. Patho-physiological role of BDNF in fibrin clotting. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:389. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37117-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amadio P., Baldassarre D., Sandrini L., Weksler B.B., Tremoli E., Barbieri S.S. Effect of cigarette smoke on monocyte procoagulant activity: Focus on platelet-derived brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Platelets. 2017;28:60–65. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2016.1203403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kermani P., Rafii D., Jin D.K., Whitlock P., Schaffer W., Chiang A., Vincent L., Friedrich M., Shido K., Hackett N.R., et al. Neurotrophins promote revascularization by local recruitment of TrkB+ endothelial cells and systemic mobilization of hematopoietic progenitors. J. Clin. Investig. 2005;115:653–663. doi: 10.1172/JCI200522655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji X.C., Dang Y.Y., Gao H.Y., Wang Z.T., Gao M., Yang Y., Zhang H.T., Xu R.X. Local Injection of Lenti-BDNF at the Lesion Site Promotes M2 Macrophage Polarization and Inhibits Inflammatory Response After Spinal Cord Injury in Mice. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015;35:881–890. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0182-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kermani P., Hempstead B. BDNF Actions in the Cardiovascular System: Roles in Development, Adulthood and Response to Injury. Front. Physiol. 2019;10:455. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anastasia A., Deinhardt K., Wang S., Martin L., Nichol D., Irmady K., Trinh J., Parada L., Rafii S., Hempstead B.L., et al. Trkb signaling in pericytes is required for cardiac microvessel stabilization. PLoS ONE. 2014:9e87406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao L., Zhang L., Chen S., Yuan Z., Liu S., Shen X., Zheng X., Qi X., Lee K.K., Chan J.Y., et al. BDNF-mediated migration of cardiac microvascular endothelial cells is impaired during ageing. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012;16:3105–3115. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang H., Liu Y., Zhang Y., Chen Z.Y. Association of plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cardiovascular risk factors and prognosis in angina pectoris. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;415:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahls M., Könemann S., Markus M.R.P., Wenzel K., Friedrich N., Nauck M., Völzke H., Steveling A., Janowitz D., Grabe H.J., et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is related with adverse cardiac remodelling and high NTproBNP. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:15421. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51776-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halade G.V., Ma Y., Ramirez T.A., Zhang J., Dai Q., Hensler J.G., Lopez E.F., Ghasemi O., Jin Y.F., Lindsey M.L. Reduced BDNF attenuates inflammation and angiogenesis to improve survival and cardiac function following myocardial infarction in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013;305:H1830–H1842. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00224.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okada S., Yokoyama M., Toko H., Tateno K., Moriya J., Shimizu I., Nojima A., Ito T., Yoshida Y., Kobayashi Y., et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor protects against cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction via a central nervous system-mediated pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:1902–1909. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ieraci A., Madaio A.I., Mallei A., Lee F.S., Popoli M. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Val66Met Human Polymorphism Impairs the Beneficial Exercise-Induced Neurobiological Changes in Mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:3070–3079. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuccato C., Cattaneo E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2009;5:311–322. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang R., Babyak M.A., Brummett B.H., Hauser E.R., Shah S.H., Becker R.C., Siegler I.C., Singh A., Haynes C., Chryst-Ladd M., et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rs6265 (Val66Met) polymorphism is associated with disease severity and incidence of cardiovascular events in a patient cohort. Am. Heart J. 2017;190:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sustar A., Nikolac Perkovic M., Nedic Erjavec G., Svob Strac D., Pivac N. A protective effect of the BDNF Met/Met genotype in obesity in healthy Caucasian subjects but not in patients with coronary heart disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016;20:3417–3426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amadio P., Colombo G.I., Tarantino E., Gianellini S., Ieraci A., Brioschi M., Banfi C., Werba J.P., Parolari A., Lee F.S., et al. BDNFVal66met polymorphism: A potential bridge between depression and thrombosis. Eur. Heart J. 2017;38:1426–1435. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Z.-Y., Jing D., Bath K.G., Ieraci A., Khan T., Siao C.-J., Herrera D.G., Toth M., Yang C., McEwen B.S., et al. Genetic Variant BDNF (Val66Met) Polymorphism Alters Anxiety-Related Behavior. Science. 2006;314:140–143. doi: 10.1126/science.1129663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarnavski O., McMullen J.R., Schinke M., Nie Q., Kong S., Izumo S. Mouse cardiac surgery: Comprehensive techniques for the generation of mouse models of human diseases and their application for genomic studies. Physiol. Genomics. 2004;16:349–360. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franzosi M., Guerrini U., Castiglioni L., Sironi L., Nobili E., Tremoli E., Caiani E.G. Feasibility of quantitative analysis of regional left ventricular function in the post-infarct mouse by magnetic resonance imaging with retrospective gating. Comput. Biol. Med. 2011;41:829–837. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castiglioni L., Colazzo F., Fontana L., Colombo G.I., Piacentini L., Bono E., Milano G., Paleari S., Palermo A., Guerrini U., et al. Evaluation of Left Ventricle Function by Regional Fractional Area Change (RFAC) in a Mouse Model of Myocardial Infarction Secondary to Valsartan Treatment. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0135778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mouton A.J., DeLeon-Pennell K.Y., Rivera Gonzalez O.J., Flynn E.R., Freeman T.C., Saucerman J.J., Garrett M.R., Ma Y., Harmancey R., Lindsey M.L. Mapping macrophage polarization over the myocardial infarction time continuum. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2018;113:26. doi: 10.1007/s00395-018-0686-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amadio P., Tarantino E., Sandrini L., Tremoli E., Barbieri S.S. Prostaglandin-Endoperoxide Synthase-2 deletion affects the natural trafficking of annexin A2 in monocytes and favours venous thrombosis in mice. Thromb. Haemost. 2017;117:1486–1497. doi: 10.1160/TH16-12-0968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giunzioni I., Bonomo A., Bishop E., Castiglioni S., Corsini A., Bellosta S. Cigarette smoke condensate affects monocyte interaction with endothelium. Atherosclerosis. 2014;234:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed M., Basheer H.A., Ayuso J.M., Ahmet D., Mazzini M., Patel R., Shnyder S.D., Vinader V., Afarinkia K. Agarose Spot as a Comparative Method for in situ Analysis of Simultaneous Chemotactic Responses to Multiple Chemokines. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1075. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00949-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eligini S., Violi F., Banfi C., Barbieri S.S., Brambilla M., Saliola M., Tremoli E., Colli S. Indobufen inhibits tissue factor in human monocytes through a thromboxane-mediated mechanism. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;69:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eligini S., Cosentino N., Fiorelli S., Fabbiocchi F., Niccoli G., Refaat H., Camera M., Calligaris G., De Martini S., Bonomi A., et al. Biological profile of monocyte-derived macrophages in coronary heart disease patients: Implications for plaque morphology. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:8680. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandrini L., Ieraci A., Amadio P., Zarà M., Mitro N., Lee F.S., Tremoli E., Barbieri S.S. Physical Exercise Affects Adipose Tissue Profile and Prevents Arterial Thrombosis in BDNF Val66Met mice. Cells. 2019;8:875. doi: 10.3390/cells8080875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinberger T., Schulz C. Myocardial infarction: A critical role of macrophages in cardiac remodelling. Front. Physiol. 2015;6:107. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McWhorter F.Y., Wang T., Nguyen P., Chung T., Liu W.F. Modulation of macrophage phenotype by cell shape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:17253–17258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308887110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathers C.D., Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan X., Anzai A., Katsumata Y., Matsuhashi T., Ito K., Endo J., Yamamoto T., Takeshima A., Shinmura K., Shen W., et al. Temporal dynamics of cardiac immune cell accumulation following acute myocardial infarction. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2013;62:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ter Horst E.N., Hakimzadeh N., van der Laan A.M., Krijnen P.A., Niessen H.W., Piek J.J. Modulators of Macrophage Polarization Influence Healing of the Infarcted Myocardium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:29583–29591. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma Y., Mouton A.J., Lindsey M.L. Cardiac macrophage biology in the steady-state heart, the aging heart, and following myocardial infarction. Transl. Res. 2018;191:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leuschner F., Dutta P., Gorbatov R., Novobrantseva T.I., Donahoe J.S., Courties G., Lee K.M., Kim J.I., Markmann J.F., Marinelli B., et al. Therapeutic siRNA silencing in inflammatory monocytes in mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore K.J., Koplev S., Fisher E.A., Tabas I., Björkegren J.L.M., Doran A.C., Kovacic J.C. Macrophage Trafficking, Inflammatory Resolution, and Genomics in Atherosclerosis: JACC Macrophage in CVD Series (Part 2) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018;72:2181–2197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yap J., Cabrera-Fuentes H.A., Irei J., Hausenloy D.J., Boisvert W.A. Role of Macrophages in Cardioprotection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2474. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bajpai G., Bredemeyer A., Li W., Zaitsev K., Koenig A.L., Lokshina I., Mohan J., Ivey B., Hsiao H.M., Weinheimer C., et al. Tissue Resident CCR2- and CCR2+ Cardiac Macrophages Differentially Orchestrate Monocyte Recruitment and Fate Specification Following Myocardial Injury. Circ. Res. 2019;124:263–278. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ridker P.M., Everett B.M., Thuren T., MacFadyen J.G., Chang W.H., Ballantyne C., Fonseca F., Nicolau J., Koenig W., Anker S.D., et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:1119–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Epelman S., Lavine K.J., Beaudin A.E., Sojka D.K., Carrero J.A., Calderon B., Brija T., Gautier E.L., Ivanov S., Satpathy A.T., et al. Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Majmudar M.D., Keliher E.J., Heidt T., Leuschner F., Truelove J., Sena B.F., Gorbatov R., Iwamoto Y., Dutta P., Wojtkiewicz G., et al. Monocyte-directed RNAi targeting CCR2 improves infarct healing in atherosclerosis-prone mice. Circulation. 2013;127:2038–2046. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X., Xiao S., Li Q. Pravastatin polarizes the phenotype of macrophages toward M2 and elevates serum cholesterol levels in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018;46:3365–3373. doi: 10.1177/0300060518787671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Meij E., Koning G.G., Vriens P.W., Peeters M.F., Meijer C.A., Kortekaas K.E., Dalman R.L., van Bockel J.H., Hanemaaijer R., Kooistra T., et al. A clinical evaluation of statin pleiotropy: Statins selectively and dose-dependently reduce vascular inflammation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otrocka-Domagała I., Paździor-Czapula K., Maślanka T. Simvastatin Impairs the Inflammatory and Repair Phases of the Postinjury Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018;2018:7617312. doi: 10.1155/2018/7617312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.