This phase 2 randomized clinical trial evaluates the safety and efficacy of the combination treatment of pembrolizumab plus docetaxel vs docetaxel alone in patients with previously treated advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

Key Points

Question

Can a combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy provide clinical benefits in immunotherapy-naive patients with disease progression after treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy?

Findings

In this phase 2 randomized clinical trial of 78 patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the combination of pembrolizumab plus docetaxel was well tolerated and substantially improved overall response rate and progression-free survival in patients with advanced disease and progression after platinum-based chemotherapy, including NSCLC with EGFR variations.

Meaning

Results suggest that the combination of pembrolizumab and docetaxel in previously treated NSCLC improves overall response rate and progression-free survival irrespective of programmed cell death ligand 1 or EGFR variation status, highlighting the potential role for this therapeutic combination in the second-line setting; these findings warrant further evaluation compared with immunotherapy.

Abstract

Importance

Because of socioeconomic factors, many patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) do not receive immunotherapy in the first-line setting. It is unknown if the combination of immunotherapy with chemotherapy can provide clinical benefits in immunotherapy-naive patients with disease progression after treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy.

Objective

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combination of pembrolizumab plus docetaxel in patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC following platinum-based chemotherapy regardless of EGFR variants or programmed cell death ligand 1 status.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Pembrolizumab Plus Docetaxel for Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer (PROLUNG) trial randomized 78 patients with histologically confirmed advanced NSCLC in a 1:1 ratio to receive either pembrolizumab plus docetaxel or docetaxel alone from December 2016 through May 2019.

Interventions

The experimental arm received docetaxel on day 1 (75 mg/m2) plus pembrolizumab on day 8 (200 mg) every 3 weeks for up to 6 cycles followed by pembrolizumab maintenance until progression or unacceptable toxic effects. The control arm received docetaxel monotherapy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was overall response rate (ORR). Secondary end points included progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival, and safety.

Results

Among 78 recruited patients, 32 (41%) were men, 34 (44%) were never smokers, and 25 (32%) had an EGFR/ALK alteration. Forty patients were allocated to receive pembrolizumab plus docetaxel, and 38 were allocated to receive docetaxel. A statistically significant difference in ORR, assessed by an independent reviewer, was found in patients receiving pembrolizumab plus docetaxel vs patients receiving docetaxel (42.5% vs 15.8%; odds ratio, 3.94; 95% CI, 1.34-11.54; P = .01). Patients without EGFR variations had a considerable difference in ORR of 35.7% vs 12.0% (P = .06), whereas patients with EGFR variations had an ORR of 58.3% vs 23.1% (P = .14). Overall, PFS was longer in patients who received pembrolizumab plus docetaxel (9.5 months; 95% CI, 4.2-not reached) than in patients who received docetaxel (3.9 months; 95% CI, 3.2-5.7) (hazard ratio, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.13-0.46; P < .001). For patients without variations, PFS was 9.5 months (95% CI, 3.9-not reached) vs 4.1 months (95% CI, 3.5-5.3) (P < .001), whereas in patients with EGFR variations, PFS was 6.8 months (95% CI, 6.2-not reached) vs 3.5 months (95% CI, 2.3-6.2) (P = .04). In terms of safety, 23% (9 of 40) vs 5% (2 of 38) of patients experienced grade 1 to 2 pneumonitis in the pembrolizumab plus docetaxel and docetaxel arms, respectively (P = .03), while 28% (11 of 40) vs 3% (1 of 38) experienced any-grade hypothyroidism (P = .002). No new safety signals were identified.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this phase 2 study, the combination of pembrolizumab plus docetaxel was well tolerated and substantially improved ORR and PFS in patients with advanced NSCLC who had previous progression after platinum-based chemotherapy, including NSCLC with EGFR variations.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02574598

Introduction

Globally, lung cancer remains the leading cause of mortality from neoplastic disease.1 Novel therapeutic strategies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, have dramatically improved clinical outcomes as first-line and second-line treatments in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).2,3,4 Results from large clinical trials, such as the KEYNOTE-001 trial,5 have changed the prognostic outlook for a particular subgroup of patients, showing a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 25% in patients with a programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) tumor proportion score of 50% or greater who were treated with immunotherapy. Moreover, results from the CheckMate 057, OAK, and KEYNOTE-010 randomized clinical trials have shown that nivolumab, atezolizumab, and pembrolizumab can outperform docetaxel in overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and OS.6,7,8 Results from a long-term follow-up of patients with PD-L1 expression of 50% or greater from the KEYNOTE-010 study9 showed a prolonged median OS across patients who received pembrolizumab compared with docetaxel (16.9 vs 8.2 months). Taken together, these findings have led to the rapid approval of immunotherapy agents and have promoted this form of therapy as the standard of care for treatment of patients with EGFR–wild-type NSCLC.10

Unfortunately, despite the overwhelming evidence for the use of immunotherapy in clinical practice, access to immune checkpoint inhibitors poses significant challenges, and as a result, many patients do not receive them as first-line treatment.11,12,13,14 Docetaxel and platinum-based chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab are additional options for patients with NSCLC who do not have access to immunotherapy.15 Unfortunately, the use of docetaxel with or without ramucirumab or nintedanib has yielded low ORR of less than 25% and limited OS outcomes in previous studies.16,17 This highlights the limited benefits with these agents as well as the need for agents that can considerably improve patient outcomes.16,17 Moreover, the concomitant use of other drugs, such as steroids and antibiotics, has been a concern because of their undesirable capability to reduce immunotherapy efficacy.18,19,20

Therefore, other studies, such as the KEYNOTE-189 trial,21 have explored the combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy and demonstrated that this strategy can improve clinical outcomes compared with chemotherapy alone for first-line treatment, irrespective of PD-L1 expression. These results suggest that the combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy can have a synergic effect in NSCLC.

The objective of this phase 2 randomized clinical trial was to evaluate the effect of combination therapy with pembrolizumab plus docetaxel vs docetaxel alone for the treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC who had progression after platinum-based chemotherapy. We hypothesized that patients treated with pembrolizumab plus docetaxel would have a better ORR compared with those treated with docetaxel alone.

Methods

Study Design

The Pembrolizumab Plus Docetaxel for Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer (PROLUNG) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02574598) was a comparative, open-label, phase 2 randomized clinical trial performed at the National Cancer Institute, Mexico in Mexico City. The study was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of treatment with pembrolizumab plus docetaxel vs docetaxel alone in patients with advanced NSCLC who had disease progression after platinum-based chemotherapy. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the institutional review board of the National Cancer Institute, Mexico and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki22 and the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Good Clinical Practice guidelines.23 Before inclusion in the trial, all patients provided written informed consent. They were not compensated for participation. Further information can be found in the trial protocol in Supplement 1.

Patients

From December 2016 through May 2019, a total of 80 patients from the National Cancer Institute, Mexico in Mexico City who were at least 18 years old with histologically confirmed metastatic NSCLC (regardless of PD-L1 expression), measurable disease per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 1 were eligible to participate. Eligibility criteria regarding pretreatments included patients who had disease progression after treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients with EGFR variations (formerly mutations) were eligible to participate if they had disease progression with at least 1 approved epidermal growth factor receptor–tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI) and platinum-based chemotherapy. In total, 78 patients agreed to participate in the study and were enrolled. Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Procedures

Patients included in the study were randomized in a 1:1 ratio using a random numbers table to receive either docetaxel monotherapy (75 mg/m2, day 1, every 3 weeks) for 6 cycles or pembrolizumab (200 mg, day 8, every 3 weeks) plus docetaxel (75 mg/m2, day 1, every 3 weeks) for 6 cycles followed by maintenance therapy with pembrolizumab until disease progression or unacceptable toxic effects.

Study Assessments

The primary outcome was ORR assessed by a blinded independent reviewer according to RECIST version 1.1. Secondary end points included PFS, OS, and safety profile.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was calculated to estimate a 2-sample proportion with a difference of 25%. The null hypothesis stated that the proportion between groups would be equal (H0: P2 = P1), whereas the alternative hypothesis stated that the proportion between groups would not be equal (H1: p2(7%)! = p1(32%)). The α value was set at .05, and power was set at 0.80. Therefore, the sample size estimate resulted in 78 patients (39 per group).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as arithmetic means or medians with SDs or percentiles for descriptive purposes, and categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Inferential comparisons were made using the t test or the Mann-Whitney U test dependent on normal or abnormal data distribution as determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests were used for assessment of the statistical significance of categorical variables, with significance defined as P < .05 when using a 2-tailed test. ORR was defined as the sum of complete response or partial response assessed by RECIST version 1.1 and was presented as a percentage with 95% CIs. To assess the correlation between observers, we performed a scatterplot of the best tumor response (assessed by RECIST version 1.1) as the continuous variable and reported the Pearson correlation value (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). PFS was defined as the time from random assignment until disease progression or death by any cause. OS was defined as the time from the date of trial enrollment until death or loss to follow-up. PFS and OS were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method, whereas comparisons among subgroups were examined using the log-rank test. For survival curve analysis, all variables were dichotomized according to their medians. A multivariate Cox proportional regression analysis was performed to assess the effect of the intervention, adjusting for statistically significant covariates (P < .10), in a forward stepwise model. Statistical significance was determined as P < .05 using a 2-tailed test. Exploratory analyses were performed for the main outcomes in the population of patients with oncogenic drivers and according to PD-L1 expression levels, if available. Stata, version 15 (StataCorp LP) was used for all statistical analysis. Data cutoff was July 7, 2019.

Results

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

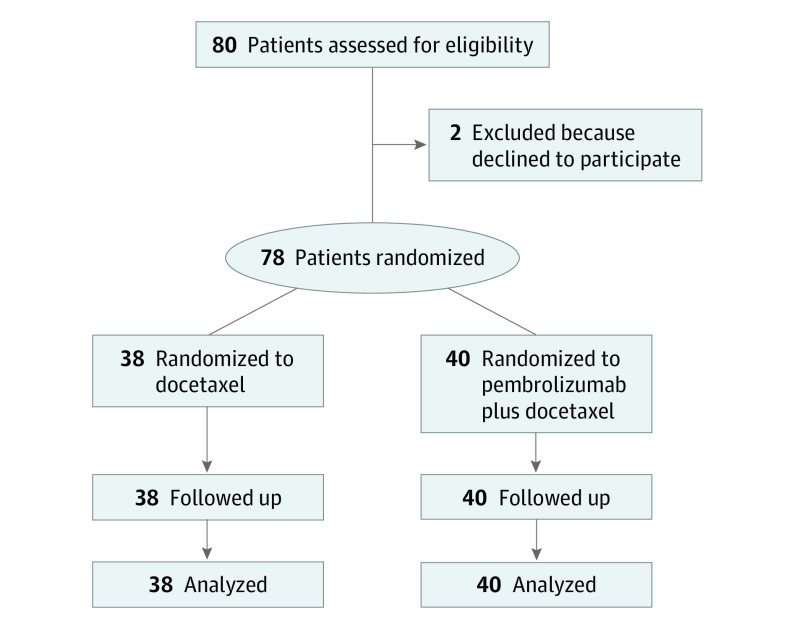

From December 2016 through May 2019, a total of 80 patients with NSCLC were reviewed for eligibility. Among those eligible, 2 patients declined to participate; therefore, a total of 78 patients were included in the study. Among 78 recruited patients, 32 (41%) were men, 34 (44%) were never smokers, and 25 (32%) had an EGFR/ALK alteration. After 1:1 randomization, 40 patients were allocated to receive pembrolizumab plus docetaxel, designated as the experimental arm, and 38 were allocated to receive docetaxel, the control arm (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics, including sex, age, smoking exposure, performance status, and EGFR variation status, were well balanced between the 2 arms. The most frequent histologic diagnosis was adenocarcinoma, accounting for 37 (93%) patients in the experimental arm and 33 (87%) patients in the control arm. A total of 25 patients with EGFR variations were included in the study—12 in the experimental arm and 13 in the control arm. Furthermore, among the 78 randomized patients, 30 (39%) were PD-L1 negative, 30 (39%) were PD-L1 positive, and 4 (5%) were not evaluable owing to insufficient tissue; the test was not performed in 14 patients (18%) (Table). The most common previous chemotherapy regimen was carboplatin and pemetrexed, which was received by 26 patients (65%) in the experimental group and 18 (47%) in the control arm. Median PFS to previous platinum-based chemotherapy was 5.5 months (95% CI, 3.9-8.3) in the experimental arm compared with 5.9 months (95% CI, 4.5-9.9) in the control arm. All 25 patients with EGFR variations received a first- or second-generation EGFR-TKI (afatinib or gefitinib) prior to platinum-based chemotherapy. Median follow-up was 8.9 months (95% CI, 4.2-15.9) for patients in the pembrolizumab plus docetaxel arm and 7.9 months (95% CI, 3.9-16.9) in the docetaxel arm. Moreover, 15 of 40 patients (38%) in the experimental arm are still receiving the assigned therapy, compared with 7 of 38 patients (18%) in the control arm who are still being observed while receiving docetaxel treatment.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram for the PROLUNG Study.

Table. General Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pembrolizumab plus docetaxel (n = 40) | Docetaxel (n = 38) | |

| Male sex | 19 (48) | 13 (34) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50.1 (13.2) | 62.1 (11.6) |

| ≥60 y | 17 (43) | 24 (63) |

| Never smoker | 17 (43) | 17 (45) |

| Smoking index, median (IQR)a | 26.6 (3.2-50.0) | 12.3 (1.6-40.0) |

| Wood smoke exposure | 9 (23) | 12 (32) |

| Index, median (IQR)b | 50.0 (5.0-114.0) | 36.0 (16.0-96.0) |

| Exposure to asbestos | 3 (8) | 4 (11) |

| ECOG status of 0-1 | 38 (95) | 38 (100) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 37 (93) | 33 (87) |

| Histologic subtype | ||

| Lepidic | 3 (8) | 2 (6) |

| Acinar/papillary | 12 (32) | 16 (49) |

| Micropapillary/solid | 15 (41) | 10 (30) |

| Not specified | 7 (19) | 5 (15) |

| Oncotarget variation | ||

| EGFR/ALK positive | 12 (30) | 13 (34) |

| EGFR subtype | ||

| E19del | 8 (67) | 9 (69) |

| E21L858R | 2 (17) | 3 (23) |

| E20T790M | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Other | 1 (8) | 1 (8) |

| CEA, median (IQR), pg/mL | 12.9 (4.7-81.6) | 8.9 (2.3-130.0) |

| PD-L1 status | ||

| Negative | 18 (45) | 12 (32) |

| Positive | 14 (35) | 16 (42) |

| Not assessable | 1 (3) | 3 (8) |

| Not tested | 7 (18) | 7 (18) |

| PD-L1 expression | ||

| Low expression (<50%) | 11 (79) | 10 (63) |

| High expression (≥50%) | 3 (21) | 6 (38) |

Abbreviations: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IQR, interquartile range; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1.

Calculated as number of cigarettes smoked per day times years of tobacco use divided by 20.

Calculated as hours per day of exposure per years of exposure.

Efficacy

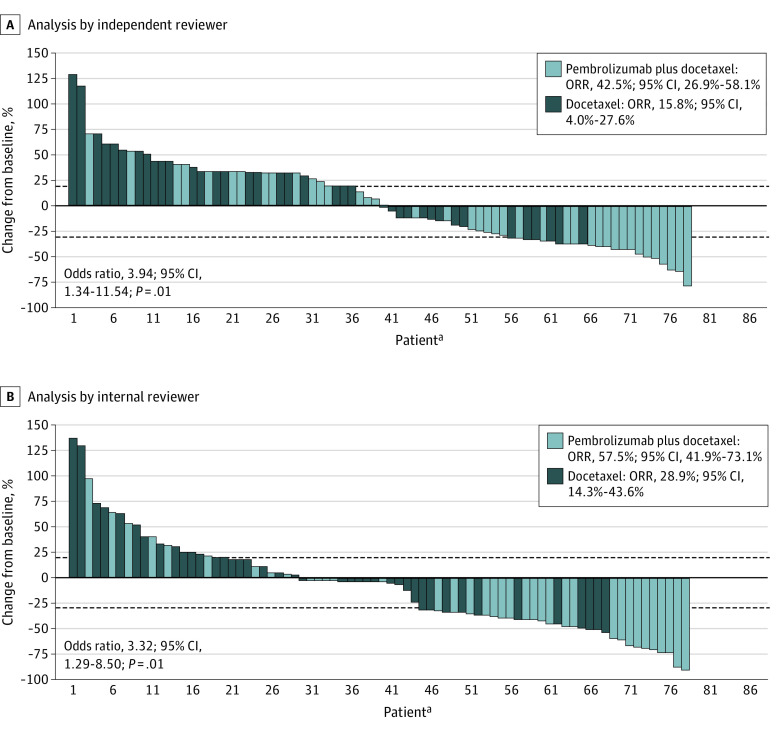

In the intention-to-treat population, the ORR according to the blinded independent reviewer was 42.5% (95% CI, 26.9%-58.1%) vs 15.8% (95% CI, 4.0%-27.6%) (odds ratio [OR], 3.94; 95% CI, 1.34-11.54; P = .01) with pembrolizumab plus docetaxel vs docetaxel, respectively, while these values were 57.5% (95% CI, 41.9%-73.1%) vs 28.9% (95% CI, 14.3%-43.6%) (OR, 3.32; 95% CI, 1.29-8.50; P = .01) following analysis by the internal investigator (Figure 2). The correlation coefficient between investigator and blinded independent reviewer was 0.855 (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Among patients with histologic diagnosis of adenocarcinoma, ORR was 56.8% (95% CI, 40.5%-73.0%) vs 33.3% (95% CI, 16.9%-49.7%) (OR, 2.62; 95% CI, 0.99-6.94; P = .05) in the pembrolizumab plus docetaxel and the docetaxel arms, respectively. Additionally, in patients with EGFR–wild-type NSCLC, ORR was 35.7% (95% CI, 17.5%-53.8%) vs 12.0% (95% CI, 0%-25.0%) (P = .045) (OR, 4.10; 95% CI, 0.97-17.10; P = .06) in the experimental and control arms, respectively (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). For patients with EGFR variations, ORR was 58.3% (95% CI, 28.9%-87.7%) in the experimental arm vs 23.1% (95% CI, 0.0%-47.2%) (P = .14) in the control group (OR, 4.60; 95% CI, 0.83-26.20; P = .08) (eTable 1 and eFigure 2 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Best Tumoral Percentage Change From Baseline for the Study Population by Independent and Internal Reviewers.

aPatients sorted by maximum percentage of decrease in descending order by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1.

ORR indicates overall response rate.

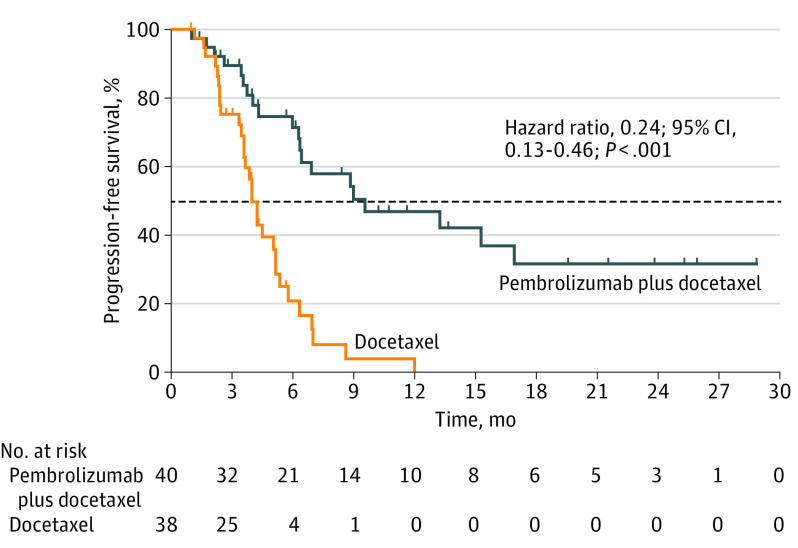

In terms of PFS, pembrolizumab plus docetaxel was significantly associated with a better clinical outcome compared with docetaxel alone (9.5 months; 95% CI, 4.2-not reached; vs 3.9 months; 95% CI, 3.2-5.7; P < .001). After adjustment for statistically significant covariates, the trial intervention (pembrolizumab plus docetaxel) was an independently associated factor with lower hazards for progression (hazard ratio [HR], 0.24; 95% CI, 0.13-0.46; P < .001) (Figure 3). In patients with adenocarcinoma, PFS was also significantly improved (6.2 months; 95% CI, 3.5-13.1; vs 3.7 months; 95% CI, 2.1-not reached; P = .03) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). For patients with EGFR–wild-type NSCLC, PFS was 9.5 months (95% CI, 3.9-not reached) vs 4.1 months (95% CI, 3.5-5.3) (HR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.13-0.55; P < .001), while patients with EGFR variations also had a prolonged PFS if treated with pembrolizumab plus docetaxel vs docetaxel alone (6.8 months; 95% CI, 6.2-not reached; vs 3.5 months; 95% CI, 2.3-6.2; HR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.07-92.60; P = .04), respectively (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2). Median duration of response was also higher in the experimental arm (11.0 months; 95% CI, 6.2-23.7; vs 5.2 months; 95% CI, 4.4-6.2; P = .03) (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2). Data on OS are still immature because the trial protocol requires a minimum follow-up of 24 months and 45 events (deaths) before data analysis. At this time, the median follow-up is 8.9 months, and 38 events have been registered (eTable 3, eFigure 5, and eFigure 6 in Supplement 2). A complete analysis of OS is planned.

Figure 3. Progression-Free Survival Among Patients in the PROLUNG Study.

Safety

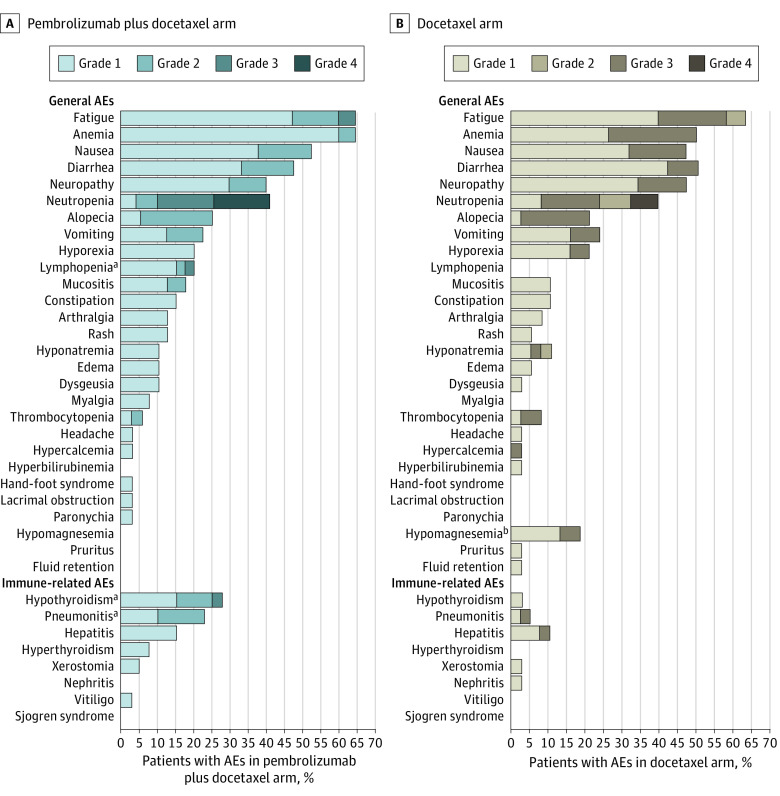

In terms of safety, the only statistically significant differences identified in any-grade, non–immune-related adverse events (AEs) were for hypomagnesemia (0 of 40 [0%] vs 7 of 38 [18%]; P = .004) and lymphopenia (8 of 40 [20%] vs 0 of 38 [0%]; P = .004) in the pembrolizumab plus docetaxel and docetaxel arms, respectively. Common AEs in both arms included fatigue (26 of 40 [65%] vs 34 of 38 [63%]), anemia (26 of 40 [65%] vs 19 of 38 [50%]), nausea (21 of 40 [53%] vs 18 of 38 [47%]), diarrhea (19 of 40 [48%] vs 19 of 38 [50%]), and neutropenia (16 of 40 [40%] vs 15 of 38 [40%]) in the pembrolizumab plus docetaxel and docetaxel arms. In terms of immune-related AEs, significantly more cases of pneumonitis were observed in the pembrolizumab plus docetaxel arm (9 of 40 [23%] vs 2 of 38 [5%]; P = .03); however, none of these were higher than grade 1 to 2, and all resolved favorably. Additionally, 11 of 40 patients (28%) in the experimental arm presented with hypothyroidism, compared with 1 of 38 (3%) in the control arm (P = .002). No additional immune-related AEs were identified that significantly differ across the study groups (Figure 4; eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Figure 4. General and Immune-Related Adverse Events (AEs) Among Patients Randomized to Pembrolizumab Plus Docetaxel Compared With Docetaxel Alone.

aHigher frequency (P < .05) compared with patients receiving docetaxel.

bHigher frequency (P < .05) compared with patients receiving pembrolizumab plus docetaxel.

Among the patients allocated to receive pembrolizumab plus docetaxel, 4 of 40 patients (15%) required a docetaxel dose reduction, and 3 of 40 patients (8%) discontinued treatment permanently. For patients in the control arm, 10 of 38 (26%) required a dose reduction, and none discontinued treatment.

Discussion

Currently, immunotherapy is the standard first-line therapy for patients with advanced NSCLC without actionable variations owing to a clear survival benefit. However, many patients do not receive immunotherapy in the first-line setting because of limited access in several world regions, cost constraints, and patient contraindications owing to comorbidities.11,12,13,14 The PROLUNG trial was designed as an independent initiative before immunotherapy became the second-line standard of care,6,7,8,24 using docetaxel as the control arm. After publication of previously mentioned studies during the course of this trial, an amendment allowed patients in the control arm to receive immunotherapy after progression. Additionally, the combination therapy used in this study was designed to first treat patients with chemotherapy on day 1 to enhance antigen liberation and increase the potential effects of immunotherapy-mediated outcomes.25

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized clinical trial to prospectively report that the combination of pembrolizumab and docetaxel is safe and efficacious in patients with advanced NSCLC that had previously progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy. The study results show a clear benefit in ORR and PFS for the combination compared with chemotherapy alone. These results are comparable to previously published data on each single agent, which have systematically shown an ORR of 10% to 17% in patients who experienced progression after platinum-based chemotherapy and received docetaxel.26,27,28,29 However, in the pembrolizumab plus docetaxel arm, the ORR obtained in this study outperformed the ORR of patients who received immunotherapy alone in the second-line setting, highlighting a possible synergic effect between chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Interestingly, ORR was particularly high in both arms, which suggests true synergy between docetaxel and pembrolizumab rather than an additive effect because the response rate for pembrolizumab alone in unselected patients, including one-third of patients with EGFR variations, cannot fully explain this increase. However, the high response rate in patients with EGFR variations did not translate into a similar PFS benefit, which suggests a shorter duration of responses. The synergistic effect has been extensively studied in the first-line setting, with the KEYNOTE-189 trial21 reporting an ORR of 47% vs 18% (P < .001) in patients receiving pembrolizumab and platinum-based chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone. Other studies, such as the IMpower130 trial,30 reported similar findings in ORR for patients treated with atezolizumab, carboplatin, and nab-paclitaxel compared with patients receiving carboplatin and nab-paclitaxel (49% vs 31%; OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.48-2.89).

Although to our knowledge a direct comparison of combined immunotherapy and chemotherapy vs immunotherapy alone has not yet been reported, indirect assessment of the results and published data of immunotherapy alone in the second-line setting suggests that combined therapy could be associated with greater efficacy without added safety signals.30 The molecular mechanism behind this potential synergistic effect has not been fully elucidated; however, studies point to an increase in immunogenicity owing to antigen release and positive modulation of the immune response.31

Interestingly, when considering the hazards for progression in studies that compared immunotherapy and chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone, results showed an HR of 0.52,21 compared with the HR of 0.24 in our study. This observation could potentially dissect the profile from each individual chemotherapy agent used in each therapy line. It is well known that second-line docetaxel offers a lower PFS compared with first-line, platinum-based chemotherapy. In this context, addition of immunotherapy helps overcome the PFS limitations of docetaxel.6,7,8,9,10

Most studies that evaluate immunotherapy show a considerable effect on OS but limited effect on PFS. This suggests that immunotherapy could influence subsequent therapies.29,30,31,32,33,34 To date, OS data from our trial are still immature. At this point, a tendency toward an improved OS in the pembrolizumab plus docetaxel arm of the study cannot be stated.

One interesting finding in this study is the efficacy profile in patients with EGFR variations, a commonly underrepresented population in immunotherapy trials. Third-generation agents were unavailable at the time of our study design, and therefore therapeutic options for patients who had disease progression after treatment with EGFR-TKIs were urgently needed. Among our study population, 25 patients (32%) had EGFR variations. Although this proportion might seem elevated, it should be noted that patients from Latin America are known to present with higher EGFR variation frequencies compared with non-Hispanic white individuals.35,36,37 Among this patient subgroup, ORR benefits are significant when comparing patients in each study arm. Furthermore, PFS benefit is also maintained in patients with EGFR variations. The IMpower150 study38 included a small number of patients with EGFR variations among its study population. Our results closely resemble those reported in this previous trial, with patients with EGFR variations having an HR of 0.42 with immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and bevacizumab following progression after treatment with EGFR-TKIs.38 Taken together, these data support the need for a continued search for combination strategies in this patient subgroup and provide evidence that the previous notion against immunotherapy should be challenged with well-designed larger trials.

AEs of any cause were reported in 51 of 78 patients (65%) included in this study. Pembrolizumab plus docetaxel presented a safety profile consistent with the individual agents; nonetheless, the increase in pneumonitis and hypothyroidism (although grade 1-2) is notable and should be considered in future study designs.

Interestingly, febrile neutropenia occurred at similar rates in both arms, and patients with this AE received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Previous studies have reported abscopal responses in patients who underwent radiotherapy while receiving granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and it would be interesting to study whether this intervention could also lead to an enhanced antitumor immune response in immunotherapy-treated patients.39 It is important to note that AEs were mostly grade 1 to 2 and manageable. Additionally, among patients who required dose reductions, only 3 patients in the experimental arm had to discontinue chemotherapy, although they did continue with pembrolizumab maintenance. No treatment-related deaths occurred.

Limitations

The data we have presented here should be interpreted in light of the study limitations. Foremost, the study was designed in the absence of recently established information; therefore, several factors were not available during the patient selection process. Patients in this study were not required to have positive PD-L1 expression. Additionally, patients with common oncogenic driver variations, including EGFR, could be enrolled. This generated a heterogeneous population in which several already characterized subgroups were present. Another important limitation is that the control arm received docetaxel, which represented the standard of care in the second-line setting when the study was designed. It is important that further studies be designed using pembrolizumab, or another programmed cell death 1 inhibitor, as a control so that the effect of the combination can be directly compared with the current standard of care. Another important factor is that patients were not required to undergo brain imaging prior to study start. Therefore, we could not assess the potential association of brain metastases with the outcome. Finally, a longer follow-up is needed to fully evaluate the OS effect of the experimental intervention because our current data are immature at this time.

Conclusions

Results from this phase 2 study suggest that the combination of pembrolizumab and docetaxel in patients with advanced NSCLC with disease progression after platinum-based chemotherapy improves ORR and PFS irrespective of PD-L1 or EGFR variation status. This highlights the potential role for this therapeutic combination in the second-line setting and warrants the design of larger, phase 3 trials that use immunotherapy as the control.

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

eTable 1. Therapeutic response by study arm in patients with wilt-type EGFR and those with EGFR mutations.

eTable 2. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the factors related with PFS.

eTable 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of the factors related with OS.

eTable 4. Adverse events and immune-related adverse by therapeutic arm and grade.

eTable 5. Treatment details and subsequent therapy.

eFigure 1. Correlation of the best tumor response (% change) from baseline between internal and independent reviewers.

eFigure 2. Waterfall-plot of the best tumor percentage change from baseline for wild type-EGFR patients (A) and EGFR-mutated patients (B).

eFigure 3. PFS by study arm in patients with EGFR mutations (A) and wild-type EGFR patients (B).

eFigure 4. Duration of response for patients receiving pembrolizumab plus docetaxel (PD) compared with those receiving docetaxel alone (D).

eFigure 5. Overall survival for patients by therapeutic arm (A); and for patients with (B) and without (C) EGFR mutations (note: data is still immature).

eFigure 6. Progression free survival (A) and overall survival (B) for patients who subsequently received pembrolizumab after progressing to docetaxel.

eFigure 7. PFS for patients in both arms of the study (PD vs. D), according to positive PD-L1 expression (A) or negative PD-L1 expression (B).

eFigure 8. Progression free survival for patients who received subsequent therapy among patients in the experimental arm (pembrolizumab plus docetaxel) and progressed (blue line) and those who subsequently received pembrolizumab following progression to docetaxel (red line).

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pacheco JM, Camidge DR, Doebele RC, Schenk E. A changing of the guard: immune checkpoint inhibitors with and without chemotherapy as first line treatment for metastatic non–small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:195. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morabito A. Second-line treatment for advanced NSCLC without actionable mutations: is immunotherapy the ‘panacea’ for all patients? BMC Med. 2018;16(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1011-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu D-P, Cheng X, Liu Z-D, Xu S-F. Comparative beneficiary effects of immunotherapy against chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC: meta-analysis and systematic review. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(2):1568-1580. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garon EB, Hellmann MD, Rizvi NA, et al. Five-year overall survival for patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab: results from the phase I KEYNOTE-001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(28):2518-2527. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim D-W, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1540-1550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627-1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. ; OAK Study Group . Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non–small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):255-265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbst RS, Garon EB, Kim D-W, et al. LBA4—long-term follow-up in the KEYNOTE-010 study of pembrolizumab (pembro) for advanced NSCLC, including in patients (pts) who completed 2 years of pembro and pts who received a second course of pembro. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl 10):x42-x43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy511.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frederickson AM, Arndorfer S, Zhang I, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer: a network meta-analysis. Immunotherapy. 2019;11(5):407-428. doi: 10.2217/imt-2018-0193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerson R, Zatarain-Barrón ZL, Blanco C, Arrieta O. Access to lung cancer therapy in the Mexican population: opportunities for reducing inequity within the health system. Salud Publica Mex. 2019;61(3):352-358. doi: 10.21149/10118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao W, Huang J, Hutton D, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness analysis of first-line pembrolizumab treatment for PD-L1 positive, non–small cell lung cancer in China. J Med Econ. 2019;22(4):344-349. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2019.1570221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chouaid C, Bensimon L, Clay E, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pembrolizumab versus standard-of-care chemotherapy for first-line treatment of PD-L1 positive (>50%) metastatic squamous and non-squamous non–small cell lung cancer in France. Lung Cancer. 2019;127:44-52. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrón-Barrón F, Guzmán-De Alba E, Alatorre-Alexander J, et al. Guía de Práctica Clínica Nacional para el manejo del cáncer de pulmón de células no pequeñas en estadios tempranos, localmente avanzados y metastásicos. Salud Publica Mex. 2019;61(3):359-414. doi: 10.21149/9916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurishima K, Watanabe H, Ishikawa H, Satoh H, Hizawa N. A retrospective study of docetaxel and bevacizumab as a second- or later-line chemotherapy for non–small cell lung cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7(1):131-134. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popat S, Mellemgaard A, Reck M, Hastedt C, Griebsch I. Nintedanib plus docetaxel as second-line therapy in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology: a network meta-analysis vs new therapeutic options. Future Oncol. 2017;13(13):1159-1171. doi: 10.2217/fon-2016-0493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garon EB, Ciuleanu T-E, Arrieta O, et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second-line treatment of stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy (REVEL): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9944):665-673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60845-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arbour KC, Mezquita L, Long N, et al. Impact of baseline steroids on efficacy of programmed cell death-1 and programmed death-ligand 1 blockade in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(28):2872-2878. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.79.0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee . Metastatic non–small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl 4):iv192-iv237. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derosa L, Hellmann MD, Spaziano M, et al. Negative association of antibiotics on clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell and non–small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(6):1437-1444. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. ; KEYNOTE-189 Investigators . Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078-2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) adopts Consolidated Guideline on Good Clinical Practice in the Conduct of Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use. Int Dig Health Legis. 1997;48(2):231-234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123-135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fossella FV, DeVore R, Kerr RN, et al. ; TAX Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Study Group . Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel versus vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(12):2354-2362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Maio M, Perrone F, Chiodini P, et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of docetaxel administered once every 3 weeks compared with once every week second-line treatment of advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1377-1382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.8251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J-K, Hahn S, Kim D-W, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors vs conventional chemotherapy in non–small cell lung cancer harboring wild-type epidermal growth factor receptor: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(14):1430-1437. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macedo-Pérez EO, Morales-Oyarvide V, Mendoza-García VO, Dorantes-Gallareta Y, Flores-Estrada D, Arrieta O. Long progression-free survival with first-line paclitaxel plus platinum is associated with improved response and progression-free survival with second-line docetaxel in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74(4):681-690. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2522-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West H, McCleod M, Hussein M, et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non–small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(7):924-937. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30167-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galon J, Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(3):197-218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0007-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez P, Peters S, Stammers T, Soria J-C. Immunotherapy for the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(9):2691-2698. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horn L, Spigel DR, Vokes EE, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: two-year outcomes from two randomized, open-label, phase III trials (CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(35):3924-3933. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.3062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peters S, Reck M, Smit EF, Mok T, Hellmann MD. How to make the best use of immunotherapy as first-line treatment of advanced/metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(6):884-896. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arrieta O, Ramírez-Tirado L-A, Báez-Saldaña R, Peña-Curiel O, Soca-Chafre G, Macedo-Perez E-O. Different mutation profiles and clinical characteristics among Hispanic patients with non–small cell lung cancer could explain the “Hispanic paradox”. Lung Cancer. 2015;90(2):161-166. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arrieta O, Cardona AF, Martín C, et al. Updated frequency of EGFR and KRAS mutations in nonsmall-cell lung cancer in Latin America: the Latin-American Consortium for the Investigation of Lung Cancer (CLICaP). J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(5):838-843. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campos-Parra AD, Zuloaga C, Manríquez MEV, et al. KRAS mutation as the biomarker of response to chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer: clues for its potential use in second-line therapy decision making. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015;38(1):33-40. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318287bb23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reck M, Mok TSK, Nishio M, et al. ; IMpower150 Study Group . Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy in non–small-cell lung cancer (IMpower150): key subgroup analyses of patients with EGFR mutations or baseline liver metastases in a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(5):387-401. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30084-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golden EB, Chhabra A, Chachoua A, et al. Local radiotherapy and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to generate abscopal responses in patients with metastatic solid tumours: a proof-of-principle trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):795-803. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00054-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

eTable 1. Therapeutic response by study arm in patients with wilt-type EGFR and those with EGFR mutations.

eTable 2. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the factors related with PFS.

eTable 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of the factors related with OS.

eTable 4. Adverse events and immune-related adverse by therapeutic arm and grade.

eTable 5. Treatment details and subsequent therapy.

eFigure 1. Correlation of the best tumor response (% change) from baseline between internal and independent reviewers.

eFigure 2. Waterfall-plot of the best tumor percentage change from baseline for wild type-EGFR patients (A) and EGFR-mutated patients (B).

eFigure 3. PFS by study arm in patients with EGFR mutations (A) and wild-type EGFR patients (B).

eFigure 4. Duration of response for patients receiving pembrolizumab plus docetaxel (PD) compared with those receiving docetaxel alone (D).

eFigure 5. Overall survival for patients by therapeutic arm (A); and for patients with (B) and without (C) EGFR mutations (note: data is still immature).

eFigure 6. Progression free survival (A) and overall survival (B) for patients who subsequently received pembrolizumab after progressing to docetaxel.

eFigure 7. PFS for patients in both arms of the study (PD vs. D), according to positive PD-L1 expression (A) or negative PD-L1 expression (B).

eFigure 8. Progression free survival for patients who received subsequent therapy among patients in the experimental arm (pembrolizumab plus docetaxel) and progressed (blue line) and those who subsequently received pembrolizumab following progression to docetaxel (red line).

Data Sharing Statement