Abstract

Pediatric concussion is a growing health concern. Concussion is generally poorly understood within the community. Many parents are unaware of the signs and varying symptoms of concussion. Despite the existence of concussion management and return to play guidelines, few parents are aware of how to manage their child’s recovery and return to activities. Digital health technology can improve the way this information is communicated to the community. A multidisciplinary team of pediatric concussion researchers and clinicians translated evidence-based, gold-standard guidelines and tools into a smartphone application with recognition and recovery components. HeadCheck is a community facing digital health application developed in Australia (not associated with HeadCheck Health) for management of concussion in children aged 5–18 years. The application consists of (I) a sideline concussion check and (II) symptom monitoring and symptom-targeted psychoeducation to assist the parent manage their child’s safe return to school, exercise and sport. The application was tested with target end users as part of the development process. HeadCheck provides an accessible platform for disseminating best practice evidence. It provides feedback to help recognize a concussion and symptoms of more serious injuries and assists parents guide their child’s recovery.

Keywords: Brain concussion, mobile application, pediatrics, post-concussion symptoms

Background

The consequences of concussion, when poorly managed, can limit child and adolescent participation in physical activity, school and organized sports (1). Concussion is a mild brain injury caused by biomechanical forces that results in a range of post-concussion symptoms (PCS) (i.e., somatic, cognitive, and emotional symptoms, sleep disturbance, and behavioral changes) (2). For most children and adolescents these symptoms resolve within 2 weeks (3,4), however, a minority continue to have symptoms beyond 1 month (3,5,6), which impact their participation in normal activities. Concussion is a growing public health concern. Each year an estimated four million children with concussion present to hospital Emergency Departments (ED) worldwide (6,7). Importantly, this figure is thought to represent only 12% of all pediatric concussions (6,8).

Timely recognition of concussion and step-wise recovery management is key to limiting the long-term impact of such injuries (1). Studies examining the impact of rest and activity post injury (9,10) have led to recommendations that cognitive and physical rest is appropriate for only a brief period (24 to 48 hours post injury), followed by graduated increases in activity in the context of symptom monitoring (11,12). Based on this information, the International Concussion in Sports Group (CISG) recently created guidelines (2) and tools (13-15) to assist with concussion recognition, and safe return to school and play (2). These guidelines have been adopted by major sporting codes (16,17) and incorporated into hospital guidelines (18). While these resources exist in the community and scientific literature, and are increasingly available in online format, wide dissemination remains a major challenge. Consequently, this information often fails to reach children and families impacted by concussion. A recent Australian study found that 93% of families presenting to a pediatric emergency service were unaware of concussion best practice guidelines (19). In organized sports, it was found that 42% of concussions were not managed according to recommended guidelines (19). Surveys have also identified low levels of knowledge of concussion and normal recovery trajectories at the community level (20,21).

Digital health tools provide the opportunity to address these gaps in care, and improve service delivery and health outcomes. These innovative tools can facilitate communication at a community level to contribute to the management of children who have sustained a concussion. To achieve significant advances in the clinical care of children after concussion, there is a need for accessible, evidence-based, and timely management. Disappointingly, a recent systematic review of concussion smartphone applications (apps) found that none of the 70 apps reviewed fulfilled criteria for being evidence-based (22).

HeadCheck is an interactive digital solution designed using the latest scientific knowledge of child concussion. It aims to provide the community with ready access to current clinical best practice. The app was initially created in 2015 as a sideline assessment tool (23), and has recently been extended to assist parents, coaches, and first aiders recognize the signs of concussion and manage a child’s safe return to normal activities (school, exercise and sport). HeadCheck provides individualized guidance for return to activity based on the child’s symptoms throughout their recovery. HeadCheck was developed by a multidisciplinary team of pediatric concussion researchers, ED physicians, allied health professionals and a digital health technology company (Curve Tomorrow). The app was developed as part of a collaboration between the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI), the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) and the Australian Football League (AFL). The app’s content is consistent with the 5th CISG consensus guidelines (2), and incorporates validated tools such as the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool 5th Edition (SCAT5 and Child SCAT5) (14,15), the Pocket Concussion Recognition Tool 5th Edition (CRT5) (13), and the Post Concussion Symptom Inventory (PCSI) (24), in an accessible tool, delivered via smartphone.

Methods

Design

HeadCheck was developed using Curve Tomorrow’s ‘Design Way’ (25). This approach is based on elements of Stanford D.School (26), IDEO design thinking (27), Google Sprint (28), and human-centered design (29). This approach ensures the experience of the end user is at the forefront of development and dissemination at all stages of the product lifespan. Curve Tomorrow’s framework allows for agile development, and involvement of key stakeholders (25).

Development

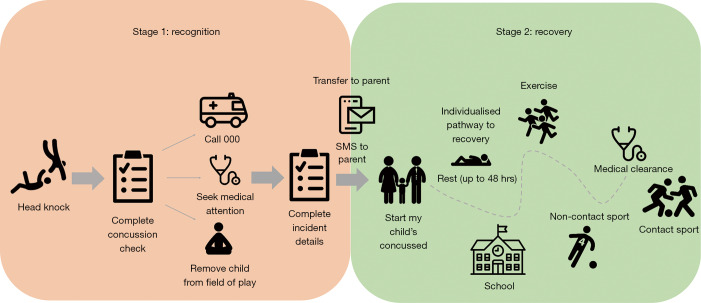

The HeadCheck app incorporates two main components: Recognition and Recovery. The Recognition component, or ‘Concussion Check’ is a sideline assessment that helps to determine injury severity and whether urgent or acute medical attention is required. The Recovery component includes symptom monitoring and symptom-targeted psychoeducation, individualized to the child to assist the parent manage safe return to school, exercise and sport (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HeadCheck Recognition and Recovery components.

Stage 1: recognition—Concussion Check

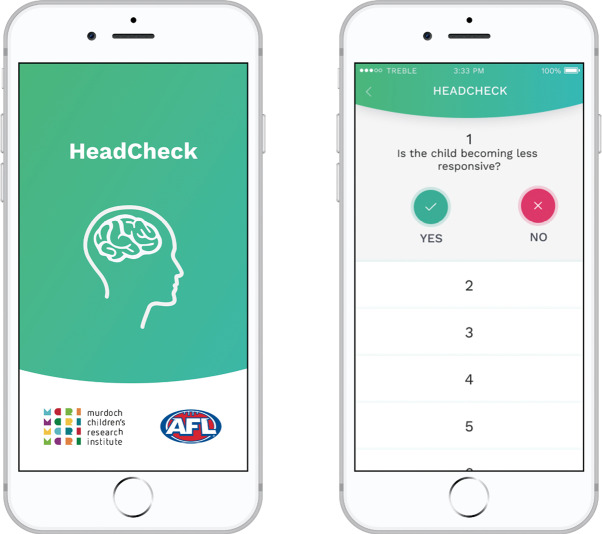

The Concussion Check takes the user through a series of questions to identify if the child has a concussion and provides real time instructions on what to do (e.g., call an ambulance, remove the child from the field of play). Content is derived from the CRT5 and SCAT5/Child SCAT5 symptom lists. The Concussion Check also monitors more serious symptoms (18), which allow users to recognize signs of a more serious head injury and take appropriate medical action (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

HeadCheck’s ‘Concussion Check’.

HeadCheck allows for a seamless handover between first line response (e.g., Concussion Check completed by first aider) and parents. When a first aider uses Concussion Check, the app populates a text message sending the parent symptom details and a link to download the app.

Stage 2: recovery—My Child’s Concussed

Entry

Parents enter directly into the recovery phase ‘My Child’s Concussed’ after downloading the app within the four days post injury. For those who enter from day two onward, additional questions are included to determine at which stage in the program they should start.

Symptom assessment

At entry, parents answer questions about the incident and complete a baseline symptom assessment. The parent version of the PCSI (24) is used to track recovery, providing both before injury and current symptom reports. The PCSI includes 20 items, with responses scored on a 7-point Guttman scale (from 0–6). Ratings are repeated at one, 3 and 7 days post injury, and when all recovery tasks are complete.

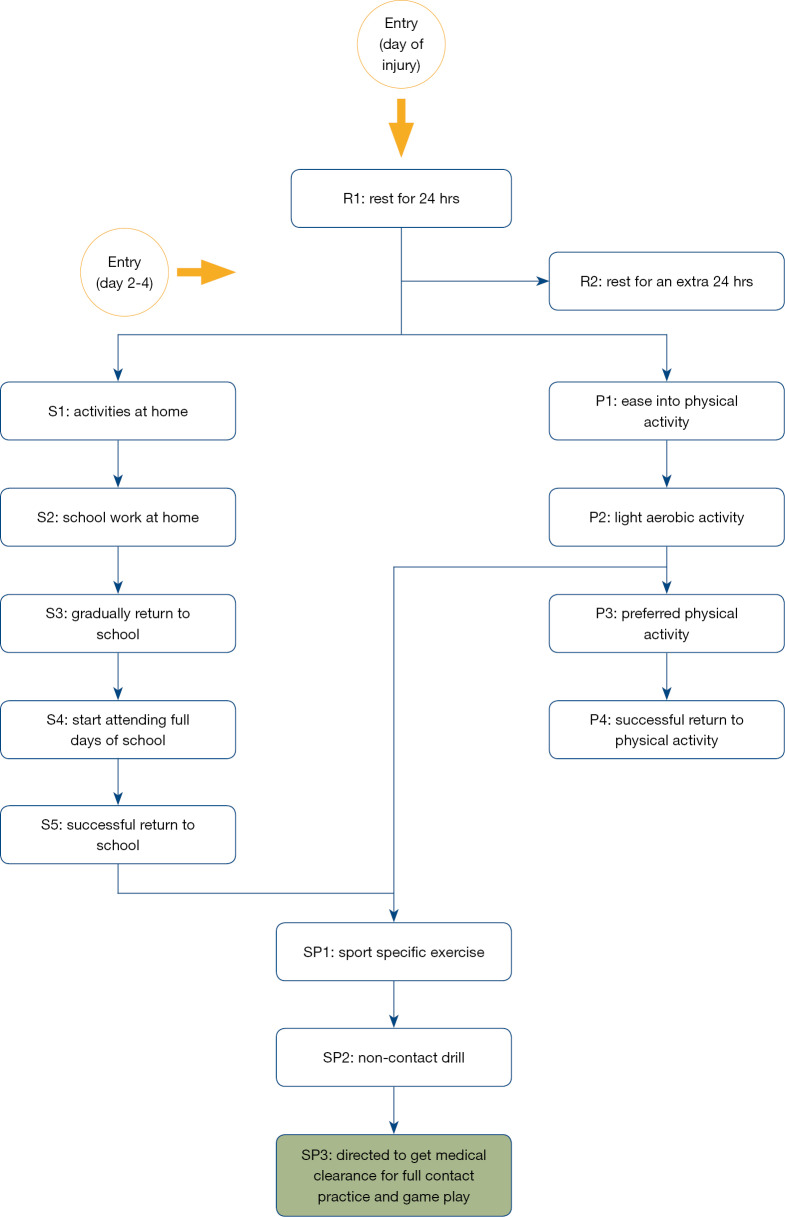

Psychoeducation

The CISG recommendations outlining the step-by step process for returning to normal activity, school and sport (2,6) were used to create the psychoeducation recovery component in the app. These recommendations were translated into sequential tasks covering four stages as outlined in Table 1. In each of the stages, parents receive both education and tasks. Progression through these tasks are dependent on symptom ratings.

Table 1. HeadCheck recovery stages.

| HeadCheck recovery stages | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Rest at home | 24 to 48 hours rest |

| Return to school | Start from tasks at home and progress to full attendance at school |

| Return to physical activity | Start with symptom limited exercise (e.g., walking) and graduate to normal activity |

| Return to organized sport | Start sport specific exercise (once returned to full time school and physical activity has progressed to light aerobic activity) to non-contact drills. Requires medical clearance to participate in full contact practice and game play |

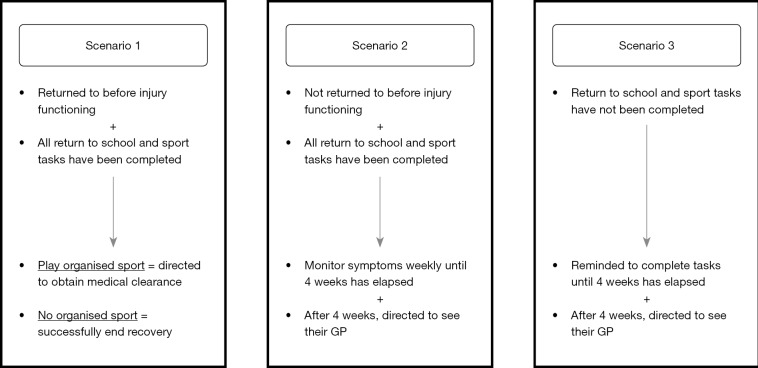

HeadCheck delivers individualized pathways to recovery by (I) assessing whether completing a task made the child’s symptoms worse, (II) restricting progression of some tasks by time (e.g., 24 hours), and (III) delaying some activities until others are completed (e.g., return to school must be complete before return to organized sport) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

HeadCheck return to activity pathways.

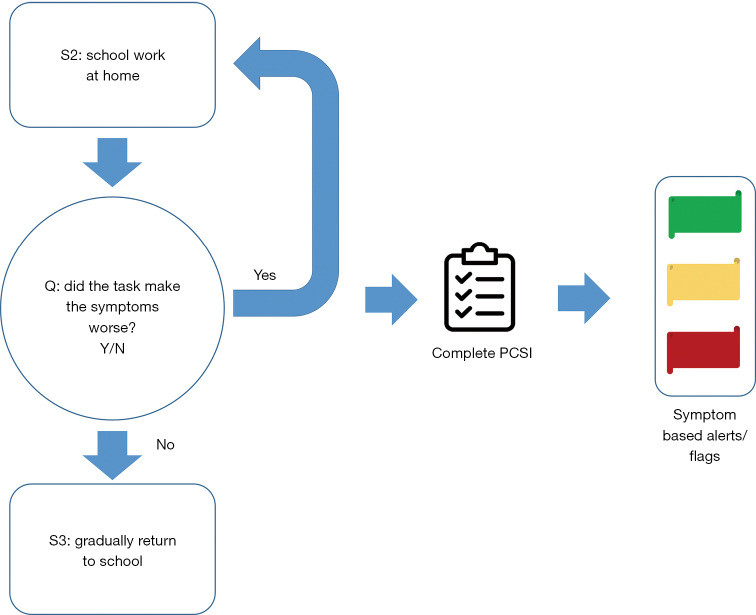

Symptom monitoring

On completion of each activity, parents are asked whether completing the task made the child’s symptoms worse. If symptoms are not exacerbated, they move on to the next recovery phase. If a task exacerbated symptoms, the parent completes the PCSI and receives further feedback based on current symptom ratings (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

HeadCheck activity and symptom monitoring.

Symptom alert system

The app contains a ‘flag based’ alert system to (I) identify a difference in ‘before injury’ and ‘current’ symptoms on the PCSI, and (II) provide a recommendation to seek medical attention if needed.

Exit criteria

Criteria to establish that the child has returned to pre injury status are based on cut-off scores validated by Hearps and colleagues (3) (see Figure 5). To meet clearance criteria, the child requires ≤1 difference in symptom severity for all items on the PCSI, compared to ‘before injury’ ratings (3). An illustration of HeadCheck discharge pathways is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

HeadCheck discharge criteria.

Test with target end users

AFL community leagues—user feedback/design validation

A design validation process sought feedback on the acceptability and feasibility of HeadCheck from AFL community leagues in August 2017. Trainers, first aiders, team managers, coaches and club presidents (n=18) provided feedback. A selection of the survey results are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Results from user feedback/design validation.

| Survey statement | Level of agreement | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| This app has increased my awareness in recognizing the signs of concussion. | Agree | 13 (72.2) |

| Strongly Agree | 1 (5.6) | |

| Does HeadCheck help you to advise parents to seek appropriate medical help following a suspected concussion? | Somewhat | 6 (33.3) |

| Definitely | 9 (50.0) | |

| Would you use this app if there was an incident where a child received a ‘knock’ (suspected concussion)? | Yes | 12 (70.6) |

| No | 1 (5.9) |

The Royal Children’s Hospital Emergency Department—pilot study

The recovery component of HeadCheck was piloted in the RCH ED in February 2018. This pilot study was approved by The Royal Children’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 37360). All participants gave informed consent prior to participation. The pilot assessed the efficacy of psychoeducation, impact on parental worry and anxiety, and feasibility of using the app in the recovery from a real incident.

A total of 13 parents of RCH ED patients with concussion were eligible for the study, nine agreed to participate, and seven provided feedback. The average age of participants was 7 years (SD=1.6), and five participants were male (71%). A selection of the survey results from this study are outlined in Table 3. All parents said they would use the app again if their child had a concussion, and the overall rating of the app was high (either 4/5 or 5/5). Parents also provided constructive feedback on the app and recommendations for new features that could enhance the product.

Table 3. Results from RCH Emergency Department pilot study.

| Survey statement | Level of agreement | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| This app has increased my awareness of the importance of concussion recovery. | Agree | 5 (71.4) |

| Strongly agree | 1 (14.3) | |

| This app has increased my knowledge of safely managing my child's recovery from concussion. | Agree | 6 (85.7) |

| Strongly agree | 0 (0) | |

| The app helped me to decide when to send my child back to school or back to practice/contact sport or normal activities. | Agree | 0 (0) |

| Strongly agree | 6 (85.7) |

Frontline clinicians

Clinical input was sought from ED consultants, ED nurse practitioners, sports medicine physicians, neurosurgeons, clinical psychologists, neuropsychologists, and physiotherapists. Multiple sessions were conducted to review and refine app content. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to gather feedback on the acceptability, feasibility and utility of the app.

Community release

In partnership with the AFL, HeadCheck was launched in Australia in May 2018. HeadCheck was made available as a free download on Australian iOS and Android platforms. As of May 2019, the app has been downloaded to approximately 29,000 smartphones.

Results and conclusions

Our primary aim in developing HeadCheck was to create an accessible, evidence-based and interactive smartphone tool which assisted concussion recognition acutely, and provided timely, individualized management to assist parents manage their child’s recovery. Our recent work suggests that community access to written and online management guidelines is surprisingly limited (19). Our goal was to ensure that evidence-based child concussion management could be widely disseminated in the community.

Evidence-based

HeadCheck content is derived from the 5th CISG consensus statement (2,6), validated tools (13-15,24), and current clinical best practice. The app reduces the barrier of paper or online resources (19) and facilitates easy access to information via smartphone.

Return to school and play guidelines were translated by clinicians into straightforward, step-wise tasks. Early intervention is actively encouraged (9-12), with examples of tasks the child can complete provided at each stage of recovery.

Timely management

HeadCheck allows for timely management of concussion by (I) allowing early recognition of concussion symptoms at the time of injury, (II) alerting the user to potential signs and symptoms of a more serious head injury, and (III) providing individualized symptom monitoring throughout the recovery phase. This allows parents to understand whether their child’s recovery is progressing as expected, when their child is ready to move to the next phase of recovery, or when their child may need additional medical attention.

Accessible

A key strength of HeadCheck is that key stakeholders were engaged throughout the app development to provide content, feedback, and suggestions for improvement. The app allows for evidence-based information to be accessed by hard to reach or vulnerable communities. Rural areas or non-elite child and adolescent sport teams may not have access to medical personnel on the sideline. HeadCheck allows first aiders or coaches to alert medical personnel or direct parents to seek medical attention for a potential concussion after a head knock.

Other benefits

Concussion recognition and its recovery is normalized through the app. Parents are exposed to the typical symptoms of concussion in the Concussion Check, and are provided with education and appropriate tasks throughout the recovery phase.

The app also provides the opportunity for de-identified epidemiological data to be collected on key questions important to clinicians, researchers and the community, which may assist with addressing issues such as concussion incidence in the community, symptom severity and typical duration of recovery, geographic ‘hotspots’ for concussion, and use of helmets at time of injury.

Challenges

One of the key challenges in creating HeadCheck was to provide evidence-based content, underpinned by current clinical best practice, translated into tasks and education that parents could use with their child. It was important to minimize the burden placed on parents to complete symptom checks, and to maximize identification of signs of a more serious injury or delayed recovery. A flag-based symptom alert system was developed to provide a responsive but considered approach to identifying when a child may need additional medical attention.

Balancing privacy, anonymity, and data collection was another critical consideration. While collecting data to answer key questions was important to the team, ultimately the privacy and confidentiality of users was of greater importance.

Clinical implications

The use of HeadCheck could increase presentations of children with a ‘head knock’ or suspected concussion to ED’s and other medical practitioners. This increase would not be unexpected given trajectories described in the US where the introduction of concussion legislation and increased public awareness has led to an increase in health care use (30).

In-app symptom monitoring throughout recovery facilitates early identification of children who are struggling with ongoing symptoms. HeadCheck directs parents of children with ongoing or concerning symptoms to seek medical attention when these symptoms are reported. This could allow active intervention (e.g., education, physiotherapy, psychology, medication) to commence earlier for these children.

Future directions

Building on the current platform, future versions of HeadCheck could provide more targeted information for different age groups, self-monitoring and education for adolescents, further support for ongoing symptoms (e.g., link to medical helpline), and integrate additional data collection for research. Development plans also consider an extension of the app to an adult version.

Our team aim for the HeadCheck app to be utilized widely in the community, various sporting codes and schools, and to become standard practice in concussion clinics and EDs.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Australian Football League (AFL).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm.2020.03.50). VA reports other from Australian Football League, grants from Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, during the conduct of the study. VCR reports other from Australian Football League, grants from The Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, during the conduct of the study. GD is a member of AFL Concussion Working Group. NA reports other from Australian Football League, grants from The Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, during the conduct of the study. AP reports other from Australian Football League, grants from The Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation, during the conduct of the study. PC reports other from Australian Football League, outside the submitted work. PH reports other from Employed by AFL, during the conduct of the study; other from AFL A/A, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Halstead ME, Walter KD, Moffatt K. Sport-related concussion in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20183074. 10.1542/peds.2018-3074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:838-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hearps SJ, Takagi M, Babl FE, et al. Validation of a score to determine time to postconcussive recovery. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20162003. 10.1542/peds.2016-2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ledoux AA, Tang K, Yeates KO, et al. Natural progression of symptom change and recovery from concussion in a pediatric population. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173:e183820. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlow KM, Crawford S, Stevenson A, et al. Epidemiology of postconcussion syndrome in pediatric mild traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics 2010;126:e374-81. 10.1542/peds.2009-0925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis GA, Anderson V, Babl FE, et al. What is the difference in concussion management in children as compared with adults? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:949-57. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branche C, Ozanne-Smith J, Oyebite K, et al. World report on child injury prevention. World Health Organization, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arbogast KB, Curry AE, Pfeiffer MR, et al. Point of health care entry for youth with concussion within a large pediatric care network. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:e160294. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown NJ, Mannix RC, O’Brien MJ, et al. Effect of cognitive activity level on duration of post-concussion symptoms. Pediatrics 2014;133:e299-e304. 10.1542/peds.2013-2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maerlender A, Rieman W, Lichtenstein J, et al. Programmed physical exertion in recovery from sports-related concussion: a randomized pilot study. Dev Neuropsychol 2015;40:273-8. 10.1080/87565641.2015.1067706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider KJ, Leddy JJ, Guskiewicz KM, et al. Rest and treatment/rehabilitation following sport-related concussion: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:930-4. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leddy J, Hinds A, Sirica D, et al. The role of controlled exercise in concussion management. PM R 2016;8:S91-S100. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Echemendia RJ, Meeuwisse W, McCrory P, et al. The concussion recognition tool 5th edition (CRT5): background and rationale. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:870-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Echemendia RJ, Meeuwisse W, McCrory P, et al. The sport concussion assessment tool 5th edition (SCAT5): background and rationale. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:848-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis GA, Purcell L, Schneider KJ, et al. The child sport concussion assessment tool 5th edition (child scat5): background and rationale. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:859-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elkington LJ, Hughes DC. Australian Institute of Sport and Australian Medical Association position statement on concussion in sport. Med J Aust 2017;206:46-50. 10.5694/mja16.00741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.League NF. NFL Head, Neck and Spine Committee's Concussion Protocol Overview. Available online: https://www.playsmartplaysafe.com/newsroom/videos/nfl-head-neck-spine-committees-concussion-protocol-overview/

- 18.The Royal Children's Hospital (2018). Head injury - return to school and sport. Retrieved 13 March, 2019.

- 19.Haran HP, Bressan S, Oakley E, et al. On-field management and return-to-play in sports-related concussion in children: are children managed appropriately? J Sci Med Sport 2016;19:194-9. 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKinlay A, Bishop A, McLellan T. Public knowledge of ‘concussion’and the different terminology used to communicate about mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI). Brain Inj 2011;25:761-6. 10.3109/02699052.2011.579935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mannings C, Kalynych C, Joseph MM, et al. Knowledge assessment of sports-related concussion among parents of children aged 5 years to 15 years enrolled in recreational tackle football. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;77:S18-S22. 10.1097/TA.0000000000000371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwan V, Bihelek N, Anderson V, et al. A review of smartphone applications for persons with traumatic brain injury: what is available and what is the evidence? J Head Trauma Rehabil 2019;34:E45-E51. 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis G, Thurairatnam S, Feleggakis P, et al. HeadCheck™. J Paediatr Child Health 2015;51:830-1. 10.1111/jpc.12879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gioia G, Schneider J, Vaughan C, et al. Which symptom assessments and approaches are uniquely appropriate for paediatric concussion? Br J Sports Med 2009;43:i13-i22. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curve Tomorrow. Curve's Design Way. Retrieved 6 September, 2019. Available online: https://www.curvetomorrow.com.au/

- 26.Stanford d.School. Stanford D.School. Retrieved 18 April, 2019. Available online: https://dschool.stanford.edu/

- 27.IDEO. Design Thinking. Retrieved 18 April, 2019. Available online: https://www.ideou.com/pages/design-thinking

- 28.Google Sprint. The Design Sprint. Retrieved 18 April, 2019. Available online: https://www.gv.com/sprint/

- 29.Murray E, Hekler EB, Andersson G, et al. Evaluating digital health interventions: key questions and approaches. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:843-51. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibson TB, Herring SA, Kutcher JS, et al. Analyzing the effect of state legislation on health care utilization for children with concussion. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:163-8. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as