Abstract

Background

Sorafenib has been recommended as the first-line treatment and shown to prolong the median overall survival (OS) of patients with advanced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Recently, a growing number of earlier studies showed the application of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) plus sorafenib in patients diagnosed at the advanced-stage HCC. This study aimed to compare the outcomes of RFA plus sorafenib versus sorafenib alone and identify prognostic factors related to OS for BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.

Methods

A total of 276 consecutive patients in BCLC stage C with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread were enrolled in this retrospective study. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier analysis, and the log-rank test examined the statistical differences between the transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and sorafenib groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to investigate the prognostic factors for OS.

Results

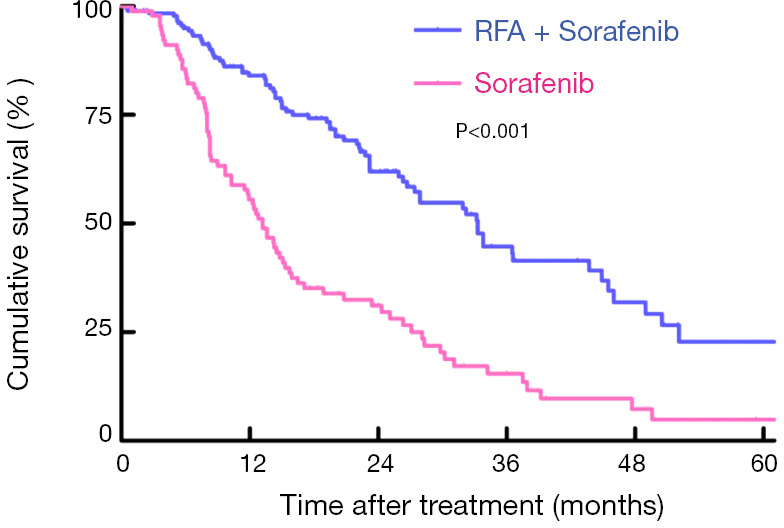

Based on the Kaplan-Meier curves, patients treated with RFA plus sorafenib showed better OS than those undergoing sorafenib, with respective OS at 1, 3 and 5 years (84.0%, 43.1%, 22.8% vs. 55.6%, 29.6%, 4.8%, Log-rank P<0.001). The univariate analysis and multivariate analysis showed that tumor size, tumor number, treatment method, albumin, bilirubin, and the Child-Pugh score were associated with OS. According to the subgroups analyses based on the tumor size and tumor number, there were significant differences in OS among overall subsets except in patients with tumor number ≥4 between RFA plus sorafenib and sorafenib therapy.

Conclusions

RFA plus sorafenib provided better prognostic performance than sorafenib, which should be suggested as an alternative treatment modality compared with sorafenib for BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.

Keywords: Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), sorafenib, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)

Introduction

Liver cancer is the seventh most common primary malignancy and the third-ranked cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (1), of which hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for more than 90% (2). The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system, by right of its prominent advantages in its prognostic prediction, has been widely adopted for treatment allocation in clinical practice (3,4). Due to dormant and asymptomatic characteristics, a large portion of the HCC patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage beyond the optimal indications of curative treatments like hepatectomy, liver transplantation, and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) (5).

Based on the BCLC staging system, patients were classified as BCLC stage C with symptomatic tumors [performance status (PS), 1–2], vascular invasion, or extrahepatic spread, which have a dismal prognosis with an expected median overall survival (OS) of 6–8 months (3). Sorafenib, an orally administered multikinase inhibitor, has been considered to be the first-line treatment and shown to prolong the median OS of patients with advanced unresectable HCC (6,7).

RFA is the standard therapy for very early-stage (single tumor <2 cm in diameter without vascular invasion/satellites in patients with ECOG-0 and well-preserved liver function) and early-stage HCC patients (ECOG-0, single tumor or three nodules <3 cm and preserved liver function) according to the BCLC staging classification (6), which has been verified in several studies to improve survival outcomes especially when combined with other therapies including transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and sorafenib (8,9). With the development of the imaging-guided location, artificial hydrothorax, and perioperative management, aggressive therapies (including but not limited to RFA and liver resection) are no longer contraindications but alternative treatment options in advanced HCC. Recently, a growing number of studies have indicated the application of RFA in patients with intermediate- and advanced-stage HCC, including patients with tumor thrombus (10,11).

The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) is commonly used for stratifying the HCC stage and selecting appropriate patients in treatment decisions in the BCLC system (12). Besides, PS has been proved to be an independent prognostic indicator of HCC patients in each stage undergoing different treatment modalities (13-15).

Although the availability of RFA combined with sorafenib in advanced HCC was preliminarily revealed in published studies, whether BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread could benefit from RFA combined with sorafenib compared with sorafenib monotherapy remain to be fully elucidated.

This present study aims to compare the survival outcomes of RFA plus sorafenib and sorafenib alone and identified prognostic factors related to OS for BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective study included consecutive HCC patients who underwent RFA plus sorafenib or sorafenib alone at our department from January 2010 to December 2017. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (I) patients classified as BCLC stage C; (II) no vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread; (III) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS score 1; (IV) Child-Pugh class A or B disease; (V) no previous therapy for HCC. Patients were excluded if any of the following reasons existed: (I) patients with other uncontrolled ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or simultaneous malignancies of another system; (II) patients with cardiopulmonary, renal or cerebral dysfunction.

HCC was diagnosed by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) based on the American Association for the Study of the Liver Disease or European Association for the Study of Liver disease (AASLD/EASL) guidelines (16,17). Clinical, laboratory and imaging data of enrolled patients were collected from the hospital database. Given the retrospective study design, the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived. This investigation was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital and performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki on human research.

Treatment and follow-up

RFA was performed with real-time ultrasonography guidance using a 17-gauge cooled-tip electrode (Cool-tip RF ablation system, Valleylab, Boulder. Co., USA). Also, percutaneous RFA was performed under local anesthesia with conscious sedation. One probelike electrode with a 2 or 3 cm exposed tip connected to a 500 kHz radiofrequency generator (Cool tip; Covidien, Boulder, Colo) was used. An electrode with a 2 cm tip was chosen for patients with a tumor diameter of 2 cm or smaller, while an electrode with a 3 cm tip was selected for patients with tumor size larger than 2 cm. Ablation at 60 W (3 cm exposed tip) or 40 W (2 cm exposed tip) was started after insertion of the electrode into the tumor. The mean duration of one ablation was 10–15 minutes.

For the sorafenib procedure, it was taken as a standard dose of 400 mg twice daily (800 mg/d) initially. Dose modification or treatment interruption temporarily was performed if drug-related toxicity was occurred according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria Adverse Events version 3.0. Sorafenib was administered continuously if possible until unacceptable toxicities occurred, disease progression developed, or death. All patients were followed up every 2 weeks in the first 6 weeks and every 6–8 weeks in the later therapeutic process, as proper. Sorafenib had begun after the diagnosis of HCC in the sorafenib group, and patients started to take sorafenib 1–3 days after RFA in the RFA plus sorafenib group.

Routine examinations were conducted at each follow-up, including physical examinations, blood tests [serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) level, serum biochemistry, liver biochemistry], and imaging examinations (chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal CT or MRI).

Statistical analysis

OS was defined as the time from the date of RFA or sorafenib therapy until death or the last follow-up. The last visit was done on December 10, 2019. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables are expressed as means (interquartile range). Differences in baseline characteristics of enrolled patients between two groups were compared using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier analysis, and the statistical differences between the RFA plus sorafenib and the log-rank test examined sorafenib monotherapy groups. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) for survival and its 95% confidence intervals (CI) of prognostic factors for OS according to the univariate and multivariate analyses. Two multivariate models with stepwise methods were separately performed for selecting the independent prognostic factors to avoid collinearity: model 1, including the baseline characteristics but excluding the Child-Pugh score; model 2 including the Child-Pugh score and baseline characteristics without albumin and bilirubin. Statistically significant was taken as a two-sided P values ≤0.05 for all analyses. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS software version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

According to the inclusion criteria, a total of 276 consecutive patients with BCLC stage C HCC were included in this present study. Of these patients, the RFA plus sorafenib group and sorafenib monotherapy group formed 186 and 90 patients, respectively. The characteristics between the two groups were no significant differences according to the statistical analysis. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study patients.

| Variable | Combination therapy group (n=186) | Sorafenib group (n=90) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/F) | 167/19 | 73/17 | 0.045 |

| Age (years) | 54 (45–63) | 52 (47–64) | 0.308 |

| Age (<60/≥60) | 123/63 | 66/24 | 0.227 |

| HBsAg (P/N) | 161/25 | 80/10 | 0.586 |

| ALT level (U/L) | 45 (29–76) | 42 (27–73) | 0.629 |

| AST level (U/L) | 56 (39–78) | 58 (44–81) | 0.393 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41.3 (36.2–44.1) | 40.6 (37.2–43.6) | 0.151 |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 17.9 (12.6–21.0) | 16.5 (12.1–20.6) | 0.435 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 186 (136–248) | 192 (141–237) | 0.846 |

| AFP level (≤400/>400) | 104/82 | 43/47 | 0.204 |

| Child-Pugh score (A5/A6/B7) | 126/46/14 | 62/21/7 | 0.968 |

| Tumor number (1/2–3/≥4) | 97/51/38 | 48/21/21 | 0.725 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 7.1 (4.2–9.8) | 7.6 (4.7–9.6) | 0.343 |

| BUN (μmol/L) | 5.2 (4.1–7.3) | 4.9 (4.2–6.8) | 0.252 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 63.2 (57.6–76.8) | 65.7 (53.6–78.2) | 0.497 |

| INR | 1.08 (1.02–1.13) | 1.09 (1.03–1.12) | 0.090 |

AFP, alpha fetoprotein; ALBI, Albumin-Bilirubin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; PT, prothrombin time; SD, standard deviation; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine.

Survival analyses of patients between TACE and sorafenib group

The last follow-up for all included patients was December 2019. For patients undergoing RFA plus sorafenib therapy, 77 patients had died during a median follow-up period of 24.9 months. However, in the sorafenib group, only 14 patients were alive while the median follow-up reached 39.7 months. Based on the Kaplan-Meier curves, patients treated with RFA plus sorafenib were shown to have better OS than those undergoing sorafenib, with respective OS at 1,3 and 5 years (84.0%, 43.1%, 22.8% vs. 55.6%, 29.6%, 4.8%, Log-rank P<0.001; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS. RFA, radiofrequency ablation; OS, overall survival.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of OS

Based on the univariate analysis for OS, the following factors were associated with survival: tumor size, tumor number, treatment method, albumin, bilirubin, and Child-Pugh score (P<0.05; Table 2). Factors above were performed in multivariate analysis (Table 3). In multivariate model 1, tumor size (HR, 1.054; 95% CI, 1.010–1.101; P=0.017), tumor number (HR, 1.943; 95% CI, 1.537–2.457; P<0.001), total bilirubin (HR, 1.037; 95% CI, 1.019–1.054; P<0.001), albumin (HR, 0.887; 95% CI, 0.847–0.929; P<0.001) and treatment method (HR, 0.965; 95% CI, 0.931–1.001; P<0.001) were identified as independent predictors of OS. As for the multivariate model 2, the independent prognostic factors included tumor size (HR, 1.057; 95% CI, 1.014–1.102; P=0.009), tumor number (HR, 2.007; 95% CI, 1.588–2.538; P<0.001), Child-Pugh score (HR, 1.367; 95% CI, 1.181–1.501; P=0.007) and treatment method (HR, 2.273; 95% CI, 1.632–3.166; P<0.001).

Table 2. Univariable analysis of prognostic factors of overall survival.

| Factors | Univariable Cox regression | |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard rate (95% CI) | P value | |

| Male sex | 0.729 (0.467–1.138) | 0.164 |

| Age (≥60 years) | 0.843 (0.596–1.193) | 0.335 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 1.052 (1.012–1.094) | 0.010 |

| AFP (>400 ng/mL) | 1.325 (0.964–1.822) | 0.083 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 0.873 (0.837–909) | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 1.049 (1.033–1.066) | <0.001 |

| PLT (×109/L) | 1.001 (0.999–1.003) | 0.193 |

| AST level (U/L) | 1.002 (0.998–1.005) | 0.124 |

| ALT level (U/L) | 1.003 (0.999–1.007) | 0.119 |

| Child-Pugh score | 1.484 (1.178–1.869) | 0.001 |

| Positive HBsAg | 1.379 (0.849–2.240) | 0.194 |

| BUN (μmol/L) | 1.040 (0.976–1.108) | 0.230 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 0.997 (0.988–1.006) | 0.512 |

| Treatment method | 2.661 (1.931–3.666) | <0.001 |

| INR | 1.003 (0.983–1.024) | 0.764 |

| Tumor number (1/2–3/≥4) | 2.421 (1.910–3.068) | <0.001 |

AFP, alpha fetoprotein; PLT, platelets; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of overall survival.

| Factors | Multivariate model 1 | Multivariate model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard rate (95% CI) | P value | Hazard rate (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 1.054 (1.010–1.101) | 0.017 | 1.057 (1.014–1.102) | 0.009 | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 0.887 (0.847–0.929) | <0.001 | – | – | |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 1.037 (1.019–1.054) | <0.001 | – | – | |

| Tumor number | 1.943 (1.537–2.457) | <0.001 | 2.007 (1.588–2.538) | <0.001 | |

| Child-Pugh score | – | – | 1.367 (1.181–1.501) | 0.007 | |

| Treatment method | 0.965 (0.931–1.001) | <0.001 | 2.273 (1.632–3.166) | <0.001 | |

Subgroup analysis

Tumor size and tumor number were further stratified in distinct groups to identify whether the two factors influenced the efficacy of HR. Tumor size was divided into three groups. Considering patients with tumor size ≤3 cm, patients undergoing RFA plus sorafenib were shown to have better OS than those treated with sorafenib alone (Log-rank P<0.001). For patients with a tumor size between 3–5 cm, there was a significant difference in OS between the two groups (Log-rank P=0.001). Among the patients with tumor size ≥5 cm, patients undergoing RFA plus sorafenib showed a better OS than those treated with sorafenib monotherapy (Log-rank P=0.001).

Furthermore, tumor number was also classified into three groups (single tumor, 2–3 tumors, ≥4 tumors). In entire subsets, according to the subgroup analyses, patients in the RFA plus sorafenib group showed better OS than those in the sorafenib group. The results of the subgroup analyses were summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Subgroup analyses of prognostic factors of overall survival.

| Variables | N (liver resection/TACE) | Median survival (liver resection vs. TACE) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| ≤3 | 74/28 | 46.000±8.944 vs. 13.600±1.786 | <0.001 |

| 3–5 | 55/30 | 36.500±3.491 vs. 10.300±3.149 | 0.001 |

| ≥5 | 57/32 | 25.900±2.764 vs. 12.800±4.384 | 0.001 |

| Tumor number | |||

| 1 | 97/48 | 45.500±6.470 vs. 24.300±6.170 | <0.001 |

| 2–3 | 51/21 | 32.300±9.221 vs. 10.300±2.136 | 0.001 |

| ≥4 | 38/21 | 11.300±2.606 vs. 8.000±3.151 | 0.273 |

TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Discussion

In this present retrospective study, we demonstrated that RFA plus sorafenib showed a significantly better OS in BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread, compared with patients undergoing sorafenib alone. Besides, the treatment method (RFA plus sorafenib vs. sorafenib) was an independent predictive factor of the better OS, while tumor size and tumor number were independent predictors of more inferior OS.

Based on the BCLC staging system, sorafenib is proposed as the standard treatment option for HCC patients in BCLC stage C which includes a great diversity of patients with single or multiple factors, such as symptomatic tumors harming PS (ECOG PS 1–2), macrovascular invasion (either segmental or portal invasion) or extrahepatic spread (lymph node involvement or metastases). Nevertheless, as for considerable heterogeneity, the diverse prognosis was observed in the C stage under the treatment of sorafenib, of which the efficacy is not satisfying. Multiple previous studies have advocated that sorafenib could inhibit the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of HCC cells after insufficient RFA, which may be used to prevent the progression of HCC after RFA (18). Gatti et al. reported a case of an HCC patient with tumor thrombus extending into the inferior vena cava treated with percutaneous ultrasound-guided RFA in which an excellent radiological and clinical response was observed (19).

Additionally, PS, which is applied to assess the patient’s capability of self-care, is deemed to be an influential predictive factor concerning OS for HCC patients. As is known to all, treatment modality is highly related to the OS of HCC patients. PS, to some extent, could influence treatment decisions. To avoid confounding factors, only patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread undergoing RFA plus sorafenib or sorafenib alone were enrolled in this present study. Our present study showed that RFA plus sorafenib was more effective than sorafenib in enhancing prognostic survival in these patients. This result showed that RFA plus sorafenib might be a more effective treatment option for BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to revealed prognostic factors about OS. Patients with poor prognosis were associated with a high grade of ECOG PS, which has been proved in earlier studies. For multivariable analysis, albumin, bilirubin, and the Child-Pugh score were entered in two different Cox proportional hazards regression models to avoid collinearity. The patients with poorer prognosis were relevant with larger tumor size higher bilirubin levels. High albumin level was regarded as an indicator of a better OS.

Additionally, different treatment methods (RFA plus sorafenib vs. sorafenib) became a significant independent predictor of OS. Subgroup analysis revealed that both RFA plus sorafenib and sorafenib were significantly related to OS in the entire subsets in which RFA plus sorafenib provided better prognostic performance than sorafenib except in patients with tumor number ≥4. No significant difference was observed in the group of patients with tumor number ≥4, which may be caused by the high incidence of recurrence or deteriorate liver function after repeated RFA therapy. These results revealed that RFA plus sorafenib might be a more effective treatment choice for BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.

However, there were several limitations to this study that should be discussed. The primary limitation is the retrospective design of this study, which could introduce information bias. All the procedures and administrations were conducted by the same seasoned team to ensure quality control and alleviate potential bias. Additionally, this study was conducted at a single center with a small sample size which could reduce its representativeness. Further high-quality prospective studies with a large sample size are needed. Finally, most of the patients in our study were Chinese with an infection of hepatitis B virus as the cause of HCC, compared with most western countries where the etiologies of HCC were mainly hepatitis C virus infection and alcoholic liver disease.

In conclusion, this retrospective study demonstrated that RFA plus sorafenib could provide a better survival outcome and should be suggested as an alternative treatment modality compared with sorafenib for BCLC stage C patients with PS 1 but without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Given the retrospective study design, the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived. This investigation was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Tangdu Hospita and performed in adherence with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm.2020.03.71). LL serves as the unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Translational Medicine from Apr 2020 to Mar 2022. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Association for the Study of the Liver . Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69:182-236. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsilimigras DI, Bagante F, Sahara K, et al. Prognosis After Resection of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) Stage 0, A, and B Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Assessment of the Current BCLC Classification. Ann Surg Oncol 2019;26:3693-700. 10.1245/s10434-019-07580-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Freitas LBR, Longo L, Santos D, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma staging systems: Hong Kong liver cancer vs Barcelona clinic liver cancer in a Western population. World J Hepatol 2019;11:678-88. 10.4254/wjh.v11.i9.689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong JH, Peng NF, You XM, et al. Tumor stage and primary treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma at a large tertiary hospital in China: A real-world study. Oncotarget 2017;8:18296-302. 10.18632/oncotarget.15433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advancedhepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:25-34. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378-90. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Ji S, Ji H, Liu L, et al. Clinical efficacy analysis of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) combined with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in primary liver cancer and recurrent liver cancer. J BUON 2019;24:1402-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giorgio A, Merola MG, Montesarchio L, et al. Sorafenib Combined with Radio-frequency Ablation Compared with Sorafenib Alone in Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Invading Portal Vein: A Western Randomized Controlled Trial. Anticancer Res 2016;36:6179-83. 10.21873/anticanres.11211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren Y, Cao Y, Ma H, et al. Improved clinical outcome using transarterial chemoembolization combined with radiofrequency ablation for patients in Barcelona clinic liver cancer stage A or B hepatocellular carcinoma regardless of tumor size: results of a single-center retrospective case control study. BMC Cancer 2019;19:983. 10.1186/s12885-019-6237-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen ZW, Lin ZY, Chen YP, et al. Clinical efficacy of endovascular radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of portal vein tumor thrombus of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Ther 2018;14:145-9. 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_784_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu CY, Lee YH, Hsia CY, et al. Performance status in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: determinants, prognosticimpact, and ability to improve the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer system. Hepatology 2013;57:112-9. 10.1002/hep.25950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J, Li A, Yang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of TACE in combination with sorafenib for the treatment of TACE-refractory advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese patients: a retrospective study. Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:2761-8. 10.2147/OTT.S131022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitale A, Burra P, Frigo AC, et al. Survival benefit of liver resection for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across differentBarcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages: a multicentre study. J Hepatol 2015;62:617-24. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facciorusso A, Del Prete V, Antonino M, et al. Serum ferritin as a new prognostic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with radiofrequency ablation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:1905-10. 10.1111/jgh.12618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruix J, Sherman M, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases . Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-2. 10.1002/hep.24199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Association For The Study Of The Liver and European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer . EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908-43. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong S, Kong J, Kong F, et al. Sorafenib suppresses the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinomacells after insufficient radiofrequency ablation. BMC Cancer 2015;15:939. 10.1186/s12885-015-1949-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gatti P, Giorgio A, Ciracì E, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma tumor thrombus entering the inferior vena cava treated with percutaneous RF ablation: a case report. J Ultrasound 2019;22:363-70. 10.1007/s40477-019-00361-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as