This systematic review and meta-analysis quantifies the risk of recurrence and death associated with minimally invasive vs open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer in observational studies optimized to control for confounding.

Key Points

Question

Are the findings of high-quality observational studies consistent with the results of a randomized clinical trial that found that minimally invasive hysterectomy was associated with a higher risk of recurrence and death compared with open surgery?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 high-quality studies comprising 9499 patients, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy was associated with shorter overall and disease-free survival among women with operable cervical cancer compared with open surgery.

Meaning

These results provide evidence to support the survival benefit associated with open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer; these findings are consistent with a recent randomized clinical trial.

Abstract

Importance

Minimally invasive techniques are increasingly common in cancer surgery. A recent randomized clinical trial has brought into question the safety of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer.

Objective

To quantify the risk of recurrence and death associated with minimally invasive vs open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer reported in observational studies optimized to control for confounding.

Data Sources

Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (inception to March 26, 2020) performed in an academic medical setting.

Study Selection

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, observational studies were abstracted that used survival analyses to compare outcomes after minimally invasive (laparoscopic or robot-assisted) and open radical hysterectomy in patients with early-stage (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2009 stage IA1-IIA) cervical cancer. Study quality was assessed with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and included studies with scores of at least 7 points that controlled for confounding by tumor size or stage.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) checklist was used to abstract data independently by multiple observers. Random-effects models were used to pool associations and to analyze the association between surgical approach and oncologic outcomes.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Risk of recurrence or death and risk of all-cause mortality.

Results

Forty-nine studies were identified, of which 15 were included in the meta-analysis. Of 9499 patients who underwent radical hysterectomy, 49% (n = 4684) received minimally invasive surgery; of these, 57% (n = 2675) received robot-assisted laparoscopy. There were 530 recurrences and 451 deaths reported. The pooled hazard of recurrence or death was 71% higher among patients who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy compared with those who underwent open surgery (hazard ratio [HR], 1.71; 95% CI, 1.36-2.15; P < .001), and the hazard of death was 56% higher (HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.16-2.11; P = .004). Heterogeneity of associations was low to moderate. No association was found between the prevalence of robot-assisted surgery and the magnitude of association between minimally invasive radical hysterectomy and hazard of recurrence or death (2.0% increase in the HR for each 10-percentage point increase in prevalence of robot-assisted surgery [95% CI, −3.4% to 7.7%]) or all-cause mortality (3.7% increase in the HR for each 10-percentage point increase in prevalence of robot-assisted surgery [95% CI, −4.5% to 12.6%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

This systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies found that among patients undergoing radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy was associated with an elevated risk of recurrence and death compared with open surgery.

Introduction

Women with early-stage cervical cancer who undergo radical hysterectomy are usually cured, with 5-year disease-free survival rates exceeding 90% in some studies.1,2,3 For more than a century, radical hysterectomy was performed predominantly through an open abdominal approach.4,5 In 1992, the laparoscopic approach for radical hysterectomy to treat cervical cancer was introduced.6,7 Over the next 25 years, traditional laparoscopic and robot-assisted minimally invasive hysterectomy gained widespread acceptance as a standard treatment for early-stage cervical cancer.8,9

Unexpectedly, the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial,3 a randomized, open-label, noninferiority study comparing minimally invasive radical hysterectomy with open radical hysterectomy, found that minimally invasive hysterectomy was associated with a higher risk of recurrence and death compared with open surgery. Women randomized to the minimally invasive arm experienced almost 4 times the risk of recurrence and 6 times the risk of death compared with women randomized to laparotomy.

In a statement released after the publication of the LACC trial, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology encouraged surgeons to discuss these data with patients undergoing surgery for cervical cancer,10 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network cervical cancer guidelines were revised to define the open abdominal approach as the “standard and recommended approach to radical hysterectomy.”11 Although randomized clinical trials have unequaled internal validity, the generalizability of such studies may be limited by differences between the study participants and the population of patients in routine clinical practice.12 Furthermore, complex interventions, such as surgery, may differ between research and real-world settings. Therefore, well-designed observational studies can be an important adjunct to the findings from randomized clinical trials. Two prior meta-analyses13,14 found no difference in overall and disease-free survival between minimally invasive and open radical hysterectomy. However, these meta-analyses do not include several recently published studies and include the results of studies that are unquestionably biased because of their failure to control for any confounders.15,16,17,18 Therefore, we undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to appraise and synthesize the available real-world evidence comparing the risk of recurrence and death between patients who underwent minimally invasive vs open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer.

Methods

Literature Search

In this systematic review and meta-analysis performed in an academic medical setting, a search was performed in Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (inception to March 26, 2020). Search structures, Medical Subject Headings, and keywords were tailored to each database by a medical research librarian (K.J.K.) specializing in systematic reviews. Searches were not limited by date, language, or study type. Grey literature resources were reviewed, such as conferences and dissertations found in Embase, for additional relevant studies. Reference lists of the included articles were searched manually. The complete MEDLINE and Embase search strings are listed in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Our findings are reported in accord with the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) reporting guideline.19 The study protocol is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020153893).

Study Selection

After the initial search, 2 of us (R.N. and A.M.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the articles to identify potentially relevant studies. A full-text review was performed on studies identified as potentially relevant in the title and abstract review. The 2 of us (R.N. and A.M.) independently screened the full-text articles to apply inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and by seeking the opinion of a third reviewer (J.A.R.-H.).

Eligibility Criteria

Observational cohort studies were included in the meta-analysis if they met the following eligibility criteria: (1) enrolled adult patients (18 years or older) with stage IA1 to IIA (with or without lymphovascular space invasion based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2009 staging system) squamous cell, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma of the cervix who were treated with either minimally invasive (traditional or robot-assisted laparoscopy) or open radical hysterectomy; (2) compared overall survival or disease-free or progression-free survival; (3) used a survival analysis method accounting for censoring and unequal follow-up among groups; (4) attempted to control for factors known to alter prognosis in cervical cancer, such as tumor size (stage was considered an acceptable proxy for size), which could also alter choice of surgical approach; (5) reported a median follow-up of at least 24 months; and (6) had a Newcastle-Ottawa Scale score of 7 points or higher and was interpreted as being of good quality.20

Studies were excluded if the results were reported in conference abstracts, letters, editorials, or any publication other than a peer-reviewed original research article or a technical report from a national public health organization. Studies were also excluded if the study population was duplicated in another study included in our meta-analysis. When studies of duplicate populations were identified, we selected the study that included more institutions or more patients.

Quality Assessment

The quality of each study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for evaluating the quality of nonrandomized studies.20 The scale evaluates study bias and assigns points in the following 3 domains: appropriate selection of participants, appropriate measures of exposure and outcome variables, and appropriate control of confounding. The scale yields a quantitative summary score and qualitative categorization of quality (poor, fair, or good) based on the number of points in the 3 domains. This categorization allows for assessment of bias such that a study is considered low quality if it is adequate in 2 domains but inadequate in a third domain. Two of us (R.N. and A.M.) independently assessed and scored each study according to the preestablished criteria.20 As is accepted in the literature,21,22,23,24 study quality was judged to be high if the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale score was at least 7 points (of a possible 9) and categorized as good (3 or 4 points in the selection domain, 2 or 3 points in the exposure and outcome domain, and 1 or 2 points in the comparability domain). Otherwise, study quality was considered low.

Data

One of us (R.N.) extracted the following data from all included studies: covariate-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs of recurrence or death (disease-free survival) or all-cause mortality (overall survival) among patients undergoing minimally invasive radical hysterectomy compared with open radical hysterectomy, covariates included in the analysis (including demographic information, tumor size, tumor stage, and year of diagnosis), number of minimally invasive and open radical hysterectomies, number of laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgical procedures, and number of deaths and recurrences. These data were validated by another of us (A.M.). When data were unavailable in a publication, efforts were made to contact the corresponding author to obtain missing details.

Statistical Analysis

Data were pooled using random-effects models25 to allow for between-study variability. Choice of the random-effects model was based on the clinical heterogeneity in terms of inclusion criteria, follow-up time, and technique identified in the included studies. Heterogeneity was assessed among included studies using the I2 statistic,26 and I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.26 Funnel plots were used to examine publication bias. Pooled HRs and 95% CIs were estimated to compare the risk of recurrence or death and the risk of all-cause mortality for patients treated with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy relative to open radical hysterectomy.

Random-effects meta-regression was used to investigate whether use of robot-assisted surgery in the minimally invasive group modified associations between minimally invasive radical hysterectomy and recurrence or death. In addition, each study was classified as predominantly using traditional or robot-assisted laparoscopy when more than 75% of minimally invasive radical hysterectomies used one of these approaches. Pooled HRs and 95% CIs were estimated for the risk of recurrence or death or the risk of all-cause mortality separately for studies in which laparoscopic or robot-assisted minimally invasive hysterectomy was the predominant approach.

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of the main findings. To investigate whether any studies had a disproportionate influence on the results of the meta-analysis, data were pooled after serially excluding each study included in the main analysis. To assess whether the results were sensitive to choice of meta-analysis model, a fixed-effects meta-analysis was performed. To assess whether choice between overlapping studies altered the main findings, the analysis was repeated including the excluded studies instead of those included in the main analysis.

All analyses were performed in Stata/MP, version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC). All reported statistical tests are 2 sided, with a significance level of .05.

Results

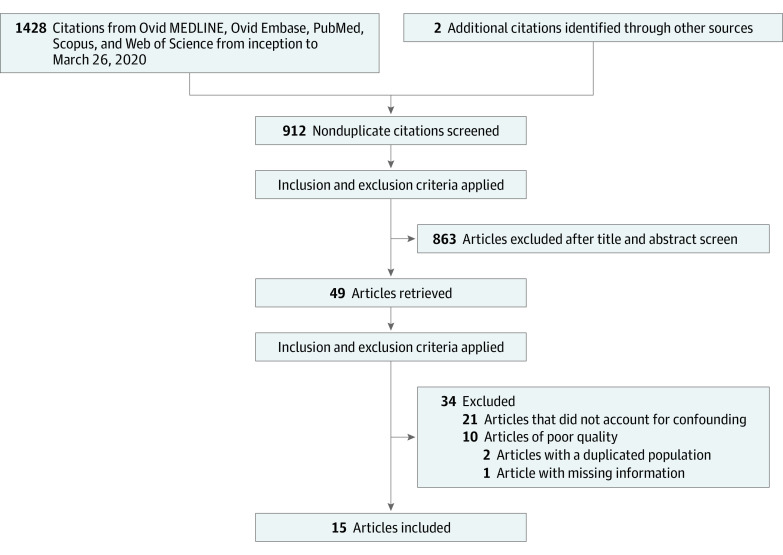

The initial search identified 1428 citations. A report from a national cancer registry27 and 1 hand-searched article28 were added; therefore, after duplicates were removed, we abstracted 912 unique citations. Of those screened, 49 observational studies comparing minimally invasive with open radical hysterectomy were evaluated for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Twenty-one studies15,16,18,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46 that did not present the results of a survival analysis accounting for confounding variables were excluded (eTable 2 in the Supplement). One study47 that did not provide enough information to assess quality was excluded. Two pairs of studies48,49,50,51 included overlapping patient populations. To avoid duplication bias, we included one study among each duplicated pair based on the number of participants and institutions.

Data quality of the remaining articles was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Ten studies17,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60 were excluded for having a score of less than 7 points, and 15 studies27,28,48,50,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71 met all of the criteria for inclusion in our meta-analysis. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram72 (Figure 1) shows the entire review process from the original search to the final selection of studies. Overall Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores ranged from 7 to 8 points (maximum score, 9 points) for the 15 included studies.27,28,48,50,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71 The analyzed high-quality studies are listed in eTable 4 in the Supplement, which shows the number of procedures performed, number of deaths and recurrences, study era, follow-up time, study type, covariates controlled for, and the strategy to control for confounding by tumor size or stage. All studies used either propensity score methods (matching or inverse probability of treatment weighting) or multivariable regression analysis and included tumor size or stage to account for differences between groups.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram.

PRISMA indicates Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Data from 9499 patients who underwent radical hysterectomy were included in the meta-analysis. Forty-nine percent of patients (n = 4684) received minimally invasive surgery, of whom 57% (n = 2675) received robot-assisted laparoscopy. There were 530 recurrences and 451 deaths reported.

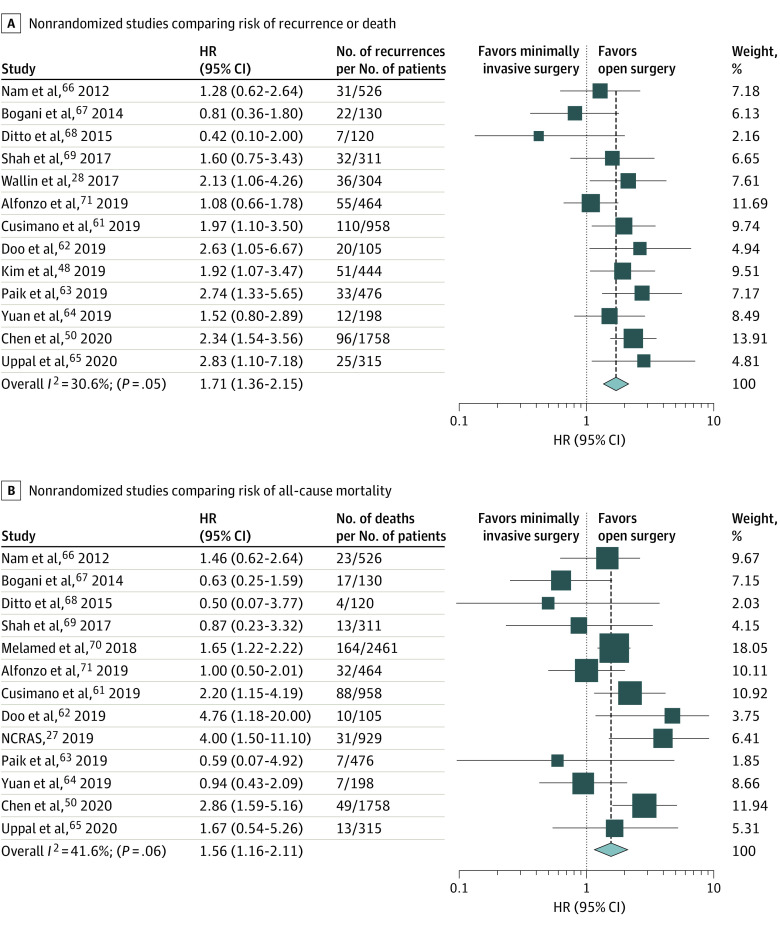

Thirteen studies28,48,50,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71 that reported confounder-adjusted survival analyses for disease-free survival, which included 6109 patients, were pooled in a random-effects model (Figure 2A). The pooled hazard of recurrence or death was 71% higher among patients who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy compared with those who underwent open surgery (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.36-2.15; P < .001), with low to moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 30.6%; P = .05). We pooled the results of 13 studies27,50,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71 that reported confounder-adjusted HRs for all-cause mortality and included 8751 patients (Figure 2B). Pooling the results from these studies demonstrated that minimally invasive radical hysterectomy was associated with a 56% higher hazard of death compared with open surgery (HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.16-2.11; P = .004), with low to moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 41.6%; P = .06).

Figure 2. Meta-analysis Results.

A and B, Confounder-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) (95% CI) for recurrence or death28,48,50,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71 (A) and for all-cause mortality27,50,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71 (B) among patients who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy (compared with open surgery) is shown for individual studies and pooled results from meta-analysis. The box size corresponds to the weight of the study in the meta-analysis. The diamond depicts the point estimate (95% CI) of the pooled estimate. The vertical dotted black line is centered at the null, whereas the dashed black line is centered at the pooled HR estimate. Summing weights may not equal 100 due to rounding. NCRAS indicates National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service.

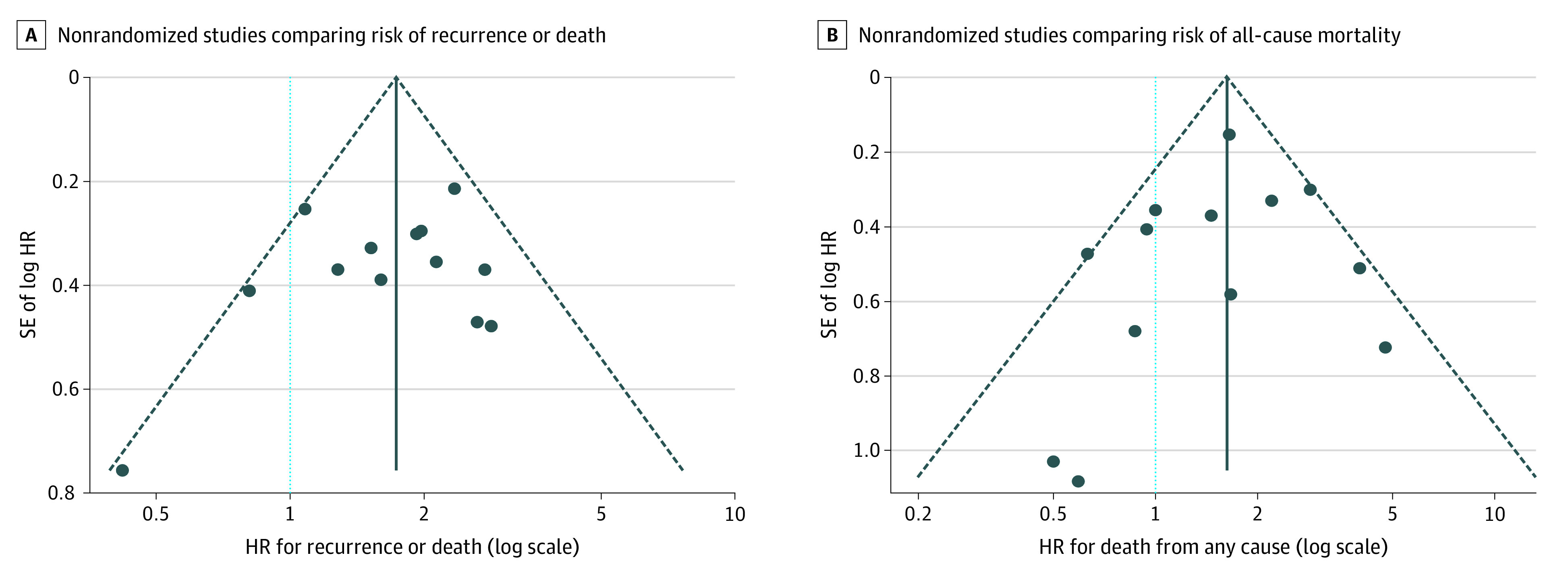

Funnel plots of study precision vs the magnitude of association are shown in Figure 3. Visual inspection shows little evidence of asymmetry in plots evaluating disease recurrence or death or all-cause mortality, suggesting the absence of substantial publication bias.

Figure 3. Funnel Plots Assessing the Distribution of Study Results Against Study Uncertainty.

A and B, The relative symmetry of association estimates (blue dots) around the pooled estimates (solid vertical line) suggests the absence of publication bias. Dashed lines depict the pseudo–95% CI around the pooled estimate, and the dotted light blue line corresponds to a null association. HR indicates hazard ratio; SE, standard error.

Use of robot-assisted radical hysterectomy among the included studies varied substantially, ranging from 0% to 100%. In 7 studies,28,50,62,65,69,70,71 minimally invasive surgery was performed predominantly by a robot-assisted approach (79%-100%), whereas traditional laparoscopy predominated in 8 studies27,48,61,63,64,66,67,68 (85%-100%). In a random-effects meta-regression model, we found no statistically significant association between the prevalence of robot-assisted surgery and the magnitude of the association between minimally invasive radical hysterectomy and risk of recurrence or death (2.0% increase in the HR for each 10-percentage point increase in prevalence of robot-assisted surgery [95% CI, −3.4% to 7.7%]) or risk of all-cause mortality (3.7% increase in the HR for each 10-percentage point increase in prevalence of robot-assisted surgery [95% CI, −4.5% to 12.6%]). In a stratified analysis (eFigure 1 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement), minimally invasive radical hysterectomy was associated with an increased risk of recurrence or death in studies in which robot-assisted laparoscopy predominated (HR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.36-2.60) and in those in which traditional laparoscopy predominated (HR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.10-2.16). Minimally invasive radical hysterectomy was also associated with a statistically significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality in studies in which robot-assisted laparoscopy predominated (HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.18-2.56) and a non–statistically significant elevation of this risk in studies in which traditional laparoscopy predominated (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.81-2.25).

In sensitivity analyses, serial exclusion of studies did not have a large association with the point estimates for pooled HRs for recurrence or death (range, 1.62-1.83) or all-cause mortality (range, 1.44-1.68). Pooled HRs remained statistically significant irrespective of excluded studies (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Study results were also insensitive to selection between duplicate studies and to selection between fixed and mixed-effects models (eAppendix in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of high-quality, nonrandomized cohort studies comparing minimally invasive vs open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer, minimally invasive techniques were associated with a higher risk of recurrence and death. These results are consistent with the findings of the LACC trial,3 a randomized noninferiority trial that unexpectedly demonstrated a higher risk of recurrence and death among patients with cervical cancer randomly assigned to laparoscopic or robot-assisted radical hysterectomy compared with those randomly assigned to open surgery. However, these results differ from 2 older meta-analyses of observational studies13,14 and conflict with a long-standing consensus that minimally invasive and open surgery are both acceptable approaches to radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer.73

Because participation in clinical trials is limited to only 5% of adult patients with cancer,74 the results of randomized clinical trials, such as the LACC trial, may not be generalizable to patients receiving routine clinical care.12 Although observational studies are susceptible to bias, they may be more generalizable to real-world settings and can thus play an important role in assessing the effectiveness of interventions. After excluding studies with major methodological deficiencies, such as lack of control for confounding,15,17,39,42,52,53,54,55,56,57,59,60 dubious reporting of survival analysis,16,18,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,58 and implausible outcome ascertainment,57 we demonstrated that higher-quality studies based on real-world data were generally concordant with the findings from the LACC trial.

The magnitude of associations estimated in the present study is considerably smaller than the effects reported by the LACC trial. Possible reasons for this discrepancy include the likelihood of residual confounding in observational studies leading to an underestimation of the risk of recurrence and death in minimally invasive surgery, as well as bias in the LACC trial findings as a result of early stoppage leading to an overestimation of these harms.75

It is important to note that the 15 studies included in our meta-analysis are heterogeneous with respect to their conclusions. Some studies concluded that minimally invasive surgery was associated with an increased risk of death27,50,61,62,70 or recurrence28,48,50,61,62,63,65 compared with open surgery, whereas other studies64,66,67,68,69,71 concluded that there is no association. Several studies64,66,67,68 that concluded that surgical approach was not associated with the risk of recurrence or death based these conclusions on few events and were thus underpowered to detect clinically relevant outcomes. In all studies that concluded that there was no association between minimally invasive surgery and progression-free or overall survival, the 95% CI included the pooled point estimates calculated in the present analysis. This finding suggests that none of these studies could exclude the presence of an association of the magnitude that we observed in this meta-analysis.

The present meta-analysis is larger (in terms of studies and patients) and included studies that were not available to the authors of prior meta-analyses.13,14 In addition to including recently published studies, our meta-analysis differs methodologically from the older meta-analyses. We required that included studies demonstrate an effort to address confounding at a minimum by demographic factors and tumor size or stage. Studies that fail to control for confounding are likely to be biased in favor of minimally invasive surgery because factors associated with a good prognosis in cervical cancer—including small tumor size, earlier stage, private insurance, and nonblack race—are more prevalent among women who undergo minimally invasive radical hysterectomy.70 Accordingly, including such studies in meta-analyses will produce biased estimates. Among 4 studies included in a meta-analysis by Wang and colleagues,13 2 had no strategy for control of known confounders and reported only crude associations.16,17 Similarly, of 10 studies included in the meta-analysis by Cao and colleagues,14 7 did not report a covariate-adjusted estimate of overall or disease-free survival15,16,17,18 or reported results that were inconsistent with their methods.43,44,46

Low to moderate heterogeneity was found in estimates of the hazard of recurrence and mortality associated with minimally invasive surgery. Differences in the association between surgical approach and recurrence or death that are not explained by chance alone may be altered by several factors. Three retrospective studies48,62,63 found that the magnitude of association between minimally invasive radical hysterectomy and recurrence or death may be associated with tumor size. Similarly, a population-based cancer registry study61 from Canada found a statistically significant interaction between tumor stage and minimally invasive surgery, suggesting that increased risk of recurrence and death may be limited to patients with macroscopic disease. Another possible explanation for observed heterogeneity is the technique used for minimally invasive surgery. Some studies have hypothesized that uterine manipulators or open colpotomy may disseminate tumor cells at the time of minimally invasive surgery.76 However, there is no conclusive evidence that tumor size or surgical technique can account for the inferior oncologic outcomes associated with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy. Because tumor size, manipulator use, and colpotomy technique were not consistently reported in the studies included in our meta-analysis, we were unable to address the contribution of these factors in this study. Some authors have suggested that robot-assisted minimally invasive radical hysterectomy may not carry the same risks as traditional laparoscopy77; however, the present study does not support this hypothesis.

Although only studies that attempted to adjust for confounders were selected for our meta-analysis, propensity score methods and multivariable regression analysis can only control for measured confounders. Residual confounding remains an important concern and is likely to result in an underestimation of the harms associated with minimally invasive surgery in this study. The included studies span 7.5 years on average, and most relied on historical controls in the open surgery group. Only 3 studies27,64,70 included contemporaneous groups; of the remaining studies, only 2 studies27,61 controlled for year of diagnosis in their analysis. Use of historical controls may bias studies in favor of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy because of advances in treatment that occurred contemporaneously with adoption of minimally invasive surgery, as well as because minimally invasive groups may have less follow-up time to accrue events.78

Limitations

Important limitations of this systematic review and meta-analysis include the possibility of bias because of residual confounding in the included studies. However, we believe this bias is likely to result in an underestimation of the harms associated with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy. In addition, we were not able to evaluate factors that may modify the association between minimally invasive surgery and survival outcomes, such as tumor size and surgical technique.

Conclusions

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of high-quality observational studies, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy was associated with shorter overall and disease-free survival than open surgery among women with early-stage cervical cancer. These results provide real-world evidence that may aid patients and clinicians engaged in shared decision-making about surgery for early-stage cervical cancer.

eTable 1. Search Strings

eTable 2. Studies Excluded Due to Absence of Confounder-Adjusted Survival Analysis

eTable 3. Quality Assignments Based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

eTable 4. High-Quality Studies Included in Meta-Analysis

eTable 5. Sensitivity of Main Results to Study Exclusion

eFigure 1. Meta-analysis Recurrence-Free Survival Stratified by Preponderance of Robotic Surgery

eFigure 2. Meta-analysis of Overall Survival Stratified by Preponderance of Robotic Surgery

eAppendix. Results of Sensitivity Analyses

eReferences.

References

- 1.Sedlis A, Bundy BN, Rotman MZ, Lentz SS, Muderspach LI, Zaino RJ. A randomized trial of pelvic radiation therapy versus no further therapy in selected patients with stage IB carcinoma of the cervix after radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73(2):177-183. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters WA III, Liu PY, Barrett RJ II, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(8):1606-1613. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(20):1895-1904. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark JG. A more radical method of performing hysterectomy for cancer of the uterus. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1895;6:120-124. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ries E. The operative treatment of cancer of the cervix. JAMA. 1906;XLVII(23):1869-1872. doi: 10.1001/jama.1906.25210230005001b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nezhat CR, Burrell MO, Nezhat FR, Benigno BB, Welander CE. Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with paraaortic and pelvic node dissection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(3):864-865. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91351-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canis M, Maze G, Wattiez A, Pouly J, Chapron C, Bruhat M. Vaginally assisted laparoscopic radical hysterectomy. J Gynecol Surg. 1992;8:103-105. doi: 10.1089/gyn.1992.8.103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uppal S, Liu JR, Reynolds RK, Rice LW, Spencer RJ. Trends and comparative effectiveness of inpatient radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer in the United States (2012-2015). Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152(1):133-138. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Neugut AI, et al. Comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive and abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1):11-17. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Society of Gynecologic Oncology Notice to SGO members: emerging data on the surgical approach for radical hysterectomy in the treatment of women with cervical cancer. Published November 13, 2018. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.sgo.org/clinical-practice/guidelines/notice-to-sgo-members-emerging-data-on-the-surgical-approach-for-radical-hysterectomy-in-the-treatment-of-women-with-cervical-cancer/

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: cervical cancer version 1. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cervical_blocks.pdf

- 12.Berger ML, Sox H, Willke R, et al. Duplicate: recommendations for good procedural practices for real-world data studies of treatment effectiveness and/or comparative effectiveness designed to inform health care decisions: report of the joint ISPOR-ISPE Special Task Force on Real-World Evidence in Health Care Decision Making. Value Health. 2017;7:1033-1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YZ, Deng L, Xu HC, Zhang Y, Liang ZQ. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the management of early stage cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:928. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1818-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao T, Feng Y, Huang Q, Wan T, Liu J. Prognostic and safety roles in laparoscopic versus abdominal radical hysterectomy in cervical cancer: a meta-analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25(12):990-998. doi: 10.1089/lap.2015.0390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong TW, Chang SJ, Lee J, Paek J, Ryu HS. Comparison of laparoscopic versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for FIGO stage IB and IIA cervical cancer with tumor diameter of 3 cm or greater. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(2):280-288. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee EJ, Kang H, Kim DH. A comparative study of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with radical abdominal hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156(1):83-86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malzoni M, Tinelli R, Cosentino F, Fusco A, Malzoni C. Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy in patients with early cervical cancer: our experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(5):1316-1323. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0342-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobiczewski P, Bidzinski M, Derlatka P, et al. Early cervical cancer managed by laparoscopy and conventional surgery: comparison of treatment results. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(8):1390-1395. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181ba5e88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting: Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells GA, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale. Accessed May 5, 2020. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 21.Houghton JSM, Nickinson ATO, Morton AJ, et al. Frailty factors and outcomes in vascular surgery patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. Published online October 22, 2019. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang T, Sidorchuk A, Sevilla-Cermeño L, et al. Association of cesarean delivery with risk of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in the offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e1910236. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammed SH, Habtewold TD, Birhanu MM, et al. Neighbourhood socioeconomic status and overweight/obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e028238. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gholami F, Moradi G, Zareei B, et al. The association between circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19(1):248. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1236-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (NCRAS) From the British Gynaecological Cancer Society Comparisons of overall survival in women diagnosed with early stage cervical cancer during 2013-2016, treated by radical hysterectomy using minimal access or open approach. Published May 2019. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://www.bgcs.org.uk/ncras-cervical-cancer-radical-hysterectomy-analysis/

- 28.Wallin E, Flöter Rådestad A, Falconer H. Introduction of robot-assisted radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer: impact on complications, costs and oncologic outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(5):536-542. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corrado G, Cutillo G, Saltari M, et al. Surgical and oncological outcome of robotic surgery compared with laparoscopic and abdominal surgery in the management of locally advanced cervical cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(3):539-546. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zanagnolo V, Minig L, Rollo D, et al. Clinical and oncologic outcomes of robotic versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for women with cervical cancer: experience at a referral cancer center. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(3):568-574. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendivil AA, Rettenmaier MA, Abaid LN, et al. Survival rate comparisons amongst cervical cancer patients treated with an open, robotic-assisted or laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: a five year experience. Surg Oncol. 2016;25(1):66-71. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sert BM, Boggess JF, Ahmad S, et al. Robot-assisted versus open radical hysterectomy: a multi-institutional experience for early-stage cervical cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(4):513-522. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laterza RM, Uccella S, Casarin J, et al. Recurrence of early stage cervical cancer after laparoscopic versus open radical surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(3):547-552. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu T, Chen X, Zhu J, et al. Surgical and pathological outcomes of laparoscopic versus abdominal radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy and/or para-aortic lymph node sampling for bulky early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(6):1222-1227. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corrado G, Vizza E, Legge F, et al. Comparison of different surgical approaches for stage IB1 cervical cancer patients: a multi-institution study and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2018;28(5):1020-1028. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo J, Yang L, Cai J, et al. Laparoscopic procedure compared with open radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy in early cervical cancer: a retrospective study. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11(11):5903-5908. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S156064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gil-Moreno A, Carbonell-Socias M, Salicrú S, et al. Radical hysterectomy: efficacy and safety in the dawn of minimally invasive techniques. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(3):492-500. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim TYK, Lin KKM, Wong WL, Aggarwal IM, Yam PKL. Surgical and oncological outcome of total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy versus radical abdominal hysterectomy in early cervical cancer in Singapore. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2019;8(2):53-58. doi: 10.4103/GMIT.GMIT_43_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matanes E, Abitbol J, Kessous R, et al. Oncologic and surgical outcomes of robotic versus open radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(4):450-458. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li G, Yan X, Shang H, Wang G, Chen L, Han Y. A comparison of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy and laparotomy in the treatment of Ib-IIa cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105(1):176-180. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magrina JF, Kho RM, Weaver AL, Montero RP, Magtibay PM. Robotic radical hysterectomy: comparison with laparoscopy and laparotomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109(1):86-91. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sert MB, Abeler V. Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: comparison with total laparoscopic hysterectomy and abdominal radical hysterectomy: one surgeon’s experience at the Norwegian Radium Hospital. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(3):600-604. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, Nam JH. Laparoscopic versus open radical hysterectomy for elderly patients with early-stage cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(3):195.e1-195.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, Nam JH. Laparoscopic compared with open radical hysterectomy in obese women with early-stage cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(6):1201-1209. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318256ccc5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim YK, Chia YN, Yam KL. Total laparoscopic Wertheim’s radical hysterectomy versus Wertheim’s radical abdominal hysterectomy in the management of stage I cervical cancer in Singapore: a pilot study. Singapore Med J. 2013;54(12):683-688. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2013242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, Nam JH. Laparoscopic versus open radical hysterectomy in patients with stage IB2 and IIA2 cervical cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108(1):63-69. doi: 10.1002/jso.23347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eoh KJ, Lee JY, Nam EJ, Kim S, Kim SW, Kim YT. The institutional learning curve is associated with survival outcomes of robotic radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):152. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-6660-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim SI, Lee M, Lee S, et al. Impact of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy on survival outcome in patients with FIGO stage IB cervical cancer: a matching study of two institutional hospitals in Korea. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;155(1):75-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim SI, Cho JH, Seol A, et al. Comparison of survival outcomes between minimally invasive surgery and conventional open surgery for radical hysterectomy as primary treatment in patients with stage IB1-IIA2 cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153(1):3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen B, Ji M, Li P, et al. Comparison between robot-assisted radical hysterectomy and abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: a multicentre retrospective study. Gynecol Oncol. Published online February 14, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen C, Liu P, Ni Y, et al. Laparoscopic versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for stage IB1 cervical cancer patients with tumor size ≤ 2 cm: a case-matched control study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25(5):937-947. doi: 10.1007/s10147-020-01630-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cantrell LA, Mendivil A, Gehrig PA, Boggess JF. Survival outcomes for women undergoing type III robotic radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: a 3-year experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117(2):260-265. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toptas T, Simsek T. Total laparoscopic versus open radical hysterectomy in stage IA2-IB1 cervical cancer: disease recurrence and survival comparison. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014;24(6):373-378. doi: 10.1089/lap.2013.0514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiao M, Zhang Z. Total laparoscopic versus laparotomic radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy in cervical cancer: an observational study of 13-year experience. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(30):e1264. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang W, Chu HJ, Shang CL, et al. Long-term oncological outcomes after laparoscopic versus abdominal radical hysterectomy in stage IA2 to IIA2 cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(7):1264-1273. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Diver E, Hinchcliff E, Gockley A, et al. Minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer is associated with reduced morbidity and similar survival outcomes compared with laparotomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(3):402-406. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim JH, Kim K, Park SJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of abdominal versus laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer in the postdissemination era. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51(2):788-796. doi: 10.4143/crt.2018.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu TWY, Ming X, Yan HZ, Li ZY. Adverse effect of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy depends on tumor size in patients with cervical cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:8249-8255. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S216929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pedone Anchora L, Turco LC, Bizzarri N, et al. How to select early-stage cervical cancer patients still suitable for laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: a propensity-matched study. Ann Surg Oncol. Published online January 2, 2020. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-08162-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brandt B, Sioulas V, Basaran D, et al. Minimally invasive surgery versus laparotomy for radical hysterectomy in the management of early-stage cervical cancer: survival outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;156(3):591-597. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.12.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cusimano MC, Baxter NN, Gien LT, et al. Impact of surgical approach on oncologic outcomes in women undergoing radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(6):619.e1-619.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doo DW, Kirkland CT, Griswold LH, et al. Comparative outcomes between robotic and abdominal radical hysterectomy for IB1 cervical cancer: results from a single high volume institution. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153(2):242-247. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paik ES, Lim MC, Kim MH, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and abdominal radical hysterectomy in early stage cervical cancer patients without adjuvant treatment: ancillary analysis of a Korean Gynecologic Oncology Group Study (KGOG 1028). Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154(3):547-553. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuan Z, Cao D, Yang J, et al. Laparoscopic vs. open abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: a single-institution, propensity score matching study in China. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1107. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uppal S, Gehrig PA, Peng K, et al. Recurrence rates in patients with cervical cancer treated with abdominal versus minimally invasive radical hysterectomy: a multi-institutional retrospective review study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(10):1030-1040. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nam JH, Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT. Laparoscopic versus open radical hysterectomy in early-stage cervical cancer: long-term survival outcomes in a matched cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(4):903-911. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bogani G, Cromi A, Uccella S, et al. Laparoscopic versus open abdominal management of cervical cancer: long-term results from a propensity-matched analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):857-862. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ditto A, Martinelli F, Bogani G, et al. Implementation of laparoscopic approach for type B radical hysterectomy: a comparison with open surgical operations. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(1):34-39. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.10.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shah CA, Beck T, Liao JB, Giannakopoulos NV, Veljovich D, Paley P. Surgical and oncologic outcomes after robotic radical hysterectomy as compared to open radical hysterectomy in the treatment of early cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017;28(6):e82. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(20):1905-1914. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alfonzo E, Wallin E, Ekdahl L, et al. No survival difference between robotic and open radical hysterectomy for women with early-stage cervical cancer: results from a nationwide population-based cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;116:169-177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koh WJ, Greer BE, Abu-Rustum NR, et al. Cervical cancer, version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(4):395-404. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Unger JM, Cook E, Tai E, Bleyer A. The role of clinical trial participation in cancer research: barriers, evidence, and strategies. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:185-198. doi: 10.14694/EDBK_156686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hughes MD, Pocock SJ. Stopping rules and estimation problems in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1988;7(12):1231-1242. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780071204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Köhler C, Hertel H, Herrmann J, et al. Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with transvaginal closure of vaginal cuff: a multicenter analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29(5):845-850. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2019-000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tewari KS. Minimally invasive surgery for early-stage cervical carcinoma: interpreting the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer trial results. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(33):3075-3080. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Melamed A, Rauh-Hain JA, Ramirez PT. Minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer: when adoption of a novel treatment precedes prospective, randomized evidence. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(33):3069-3074. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Search Strings

eTable 2. Studies Excluded Due to Absence of Confounder-Adjusted Survival Analysis

eTable 3. Quality Assignments Based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

eTable 4. High-Quality Studies Included in Meta-Analysis

eTable 5. Sensitivity of Main Results to Study Exclusion

eFigure 1. Meta-analysis Recurrence-Free Survival Stratified by Preponderance of Robotic Surgery

eFigure 2. Meta-analysis of Overall Survival Stratified by Preponderance of Robotic Surgery

eAppendix. Results of Sensitivity Analyses

eReferences.