Abstract

Background

Lung cancer patients commonly report stigma, often attributing it to the well-established association of smoking as the leading preventable cause. Theory and research suggest that patients’ smoking history may differentiate patients’ experience of lung cancer stigma. However, there is inconsistent evidence whether lung cancer stigma varies by patients’ smoking history, owing to limitations in the literature.

Purpose

This study examined differences in lung cancer patients’ reported experience of lung cancer stigma by smoking history.

Method

Participants (N = 266, 63.9% female) were men and women with lung cancer who completed a validated, multidimensional questionnaire measuring lung cancer stigma. Multivariable regression models characterized relationships between smoking history (currently, formerly, and never smoked) and lung cancer stigma, controlling for psychological and sociodemographic covariates.

Results

Participants who currently smoked reported significantly higher total, internalized, and perceived lung cancer stigma compared to those who formerly or never smoked (all p < .05). Participants who formerly smoked reported significantly higher total and internalized stigma compared to those who never smoked (p < .001). Participants reported similar levels of constrained disclosure, regardless of smoking history (p = .630).

Conclusions

Total, internalized, and perceived stigma vary meaningfully by lung cancer patients’ smoking history. Patients who smoke at diagnosis are at risk for experiencing high levels of stigma and could benefit from psychosocial support. Regardless of smoking history, patients reported similar levels of discomfort in sharing information about their lung cancer diagnosis with others. Future studies should test relationships between health-related stigma and associated health behaviors in other stigmatized groups.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Stigma, Smoking, Disclosure, Health behavior

The majority of lung cancer patients report experiencing significant levels of stigma, and stigma is generally highest among patients who smoke at diagnosis, followed by those who formerly smoked, then by those who never smoked.

Some people with chronic health conditions, such as those with lung cancer, are characterized as targets of stigma [1]. The majority (95%) of lung cancer patients report experiencing stigma [2], which is often attributed to the negative attitudes about cigarette smoking and about the disease itself [3, 4]. Lung cancer stigma is a multifaceted construct that encompasses perceived stigma (i.e., negative appraisal and devaluation from others), internalized stigma (i.e., perceptions of stigma from others that are internalized by the individual, characterized by shame, guilt, and/or self-blame), and constrained disclosure (i.e., discomfort in discussing one’s lung cancer) [2, 5]. The general population and medical professionals evidence negatively biased perceptions toward lung cancer patients [6], and researchers have demonstrated that lung cancer stigma contributes to the burden of illness for patients. In fact, a growing body of cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence demonstrates that higher lung cancer stigma is associated with poorer health-related outcomes, such as higher anxiety and depressive symptoms, bothersome physical symptoms, and worse quality of life [7–11]. Further research is needed to characterize the psychosocial and behavioral characteristics (e.g., smoking history) associated with lung cancer stigma. Doing so will allow researchers to identify groups of patients at risk to experience clinically meaningful stigma [7], who could benefit from psychosocial interventions aimed to reduce stigma and improve health.

Some studies have demonstrated that feelings of regret, guilt, and/or shame (indicators of internalized stigma) are higher among those who smoked [8, 9], whereas others have found no differences by patients’ smoking history in constrained disclosure [8] or stigma-related social isolation [10, 11]. Thus, smoking history may differentiate lung cancer patients’ experience of certain (but not all) facets of lung cancer stigma; however, the measures of lung cancer stigma vary across studies [3], which precludes direct comparison. Feelings of internalized stigma may be higher among those who currently or formerly smoked because the psychological experiences of guilt and regret are closely linked with the experience of smoking [12]. By contrast, other facets, such as constrained disclosure may be experienced more broadly across smoking history groups because there are many reasons why lung cancer patients may feel uncomfortable sharing their diagnosis. Patients are commonly asked about their smoking behavior after sharing their lung cancer diagnosis, and they perceive this question to imply blame and/or convey smoking-related assumptions [2]. Patients may also avoid talking about their diagnosis because they do not want to burden others, be treated as vulnerable, or be pitied [13].

Most prior studies have combined patients who formerly or currently smoked into one analytic category due to the small number of recruited patients who currently smoked [12, 14]. As such, less is known about whether lung cancer stigma varies by smoking history among those who currently, formerly, and never smoked. One study demonstrated that lung cancer patients who currently smoked evidenced higher levels of internalized stigma than participants who formerly or never smoked [8]. This study also showed that constrained disclosure was equivalent across all three smoking history groups. However, this study faced the following limitations: (a) the study enrolled a relatively low number of participants who currently smoked (n = 8), (b) the stigma measure was not specifically developed for use in lung cancer patients, and (c) the comparison of stigma by smoking history did not adjust for potentially important covariates (e.g., age, sex, depressive symptoms). Therefore, research is needed to investigate whether the pattern of findings from Williamson et al. [8] can be replicated in a larger sample of patients and using a separate, well-validated measure of lung cancer stigma.

Our research team recently developed the Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory, which was validated using rigorous psychometric procedures and captures the experience of internalized stigma, perceived stigma, and constrained disclosure [5, 7]. In the current study, this measure was used to test whether lung cancer stigma varied by patients’ smoking history, controlling for sociodemographic and psychological covariates. Based on theory and research [2, 8, 9], it was hypothesized that total, internalized, and perceived lung cancer stigma would be highest among those who currently smoked, followed by those who formerly smoked, and then by those who never smoked. It was also predicted that constrained disclosure would not statistically differ across the smoking history groups based on theory and research that patients may have several reasons to not share their lung cancer diagnosis, regardless of smoking history [8, 13].

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through outpatient thoracic oncology clinics at two National Cancer Institute (NCI) designated cancer centers in the Southern and Northeastern regions of the USA. Participants were eligible if they were: (a) 18 years of age; (b) diagnosed with or treated for lung cancer (any type, any stage) within the last 12 months; and (c) able to read and respond to questionnaires in English. Participants were excluded if they evidenced cognitive impairment. Additional efforts were made to recruit current smokers. All participants provided written informed consent, and all procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at both sites. This study reports secondary analyses from a multiphase, multisite study on characterizing stigma in lung cancer patients; additional information on the sample and study methods have been reported previously [5, 7].

Procedure

Eligible participants who provided informed consent completed questionnaires on sociodemographic characteristics, smoking history, lung cancer stigma, and depressive symptoms. Participants could complete questionnaires via a tablet provided by research staff, a secure web-based portal from their own computer, or a pencil-and-paper survey.

Measures

Smoking history was categorized following well-established guidelines [7, 9]. Participants who reported smoking fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime were categorized as participants who never smoked; those who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and had quit smoking by the time of data collection were categorized as participants who formerly smoked; and those who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and were currently smoking (“every day” or “some days”) were categorized as participants who currently smoked.

Lung cancer stigma was assessed using the 25-item Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory, which has demonstrated good reliability and validity [5, 7]. Participants rated items on a five-point Likert scale (“not at all” to “extremely”), with higher scores indicating higher stigma. A total score and subscales for internalized stigma (e.g., “I have felt guilty about my lung cancer”), perceived stigma (e.g., “People have told me I was to blame for getting lung cancer”), and constrained disclosure (e.g., “It has been hard to tell people that I have lung cancer”) were computed; all showed adequate reliability (all α > .78). In addition, participants were categorized based on an empirically derived cutpoint (≥38 total), indicating clinically meaningful stigma [7]. The full scale can be accessed through the National Cancer Institute Grid-Enabled Measures Database at https://www.gem-measures.org/public/DownloadMeasure.aspx?mdocid=435.

The 10‐item short form of the Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale was used to assess depressive symptoms [15]. Participants rated items (e.g., “I felt depressed”) on a four-point scale (“rarely” to “all of the time”) to indicate their mood. This scale has previously demonstrated good reliability and validity (current α = .69).

Analytic Strategy

Pearson’s correlations, t-tests, analysis of variances, chi-squares, and Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted as appropriate to characterize relationships between sociodemographic characteristics, depressive symptoms, lung cancer stigma, and smoking history. Multivariable linear regression models were conducted to evaluate smoking history as a predictor of lung cancer stigma. The lung cancer stigma total score and subscale scores were each entered as the dependent variable in four separate models. Planned follow-up comparisons were conducted to evaluate between-group differences in lung cancer stigma scores by smoking history when the omnibus factor of smoking history significantly predicted the outcome. Age, sex, and depressive symptoms were selected as a priori covariates. Any other sociodemographic characteristic (i.e., education, marital status, race/ethnicity) associated with smoking history or lung cancer stigma at p < .05 was also added as a covariate. Two-tailed significance tests were used, and p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Sample characteristics

Participants (N = 266) were men (n = 96, 36.1%) and women with lung cancer, who were, on average, 63.31 years old (standard deviation [SD] = 10.80). There were 60 participants who never smoked, 154 who formerly smoked, and 49 who currently smoked at the time of study enrollment (3 had missing smoking data). The majority was married (n = 162, 60.9%) and non-Hispanic white (n = 209, 78.6%), and half obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher (n = 133, 50.0%). Participants had a mean of 52.37 (SD = 16.27) for lung cancer stigma (n = 212, 79.7% surpassed the cutoff for clinically meaningful stigma), and 8.53 (SD = 6.09) on depressive symptoms (n = 95; 35.7% evidenced scores ≥10, suggestive of clinical depression) [15].

Covariates

Smoking history groups differed significantly by age (F[2, 259] = 3.17, p = .044), education (Kruskal–Wallis H = 6.30, p = .043), marital status (Kruskal–Wallis H = 6.79, p = .034), and race/ethnicity (Kruskal–Wallis H = 10.30, p = .006) but not by gender or depressive symptoms (all p > .07). Participants who never smoked were more likely to have completed a bachelor’s degree or beyond (n = 38/60, 63.3%) compared to those who formerly smoked (n = 68/153, 44.4%, χ2 = 6.15, p = .013). Also, participants who never smoked were more likely to be married (n = 41/56, 73.2%) compared to those who currently smoked (n = 24/49, 49.0%, χ2 = 6.51, p = .011). Finally, a greater proportion of participants who currently smoked (n = 43/48, 89.6%) were non-Hispanic white compared to participants who never (n = 40/60, 66.7%, χ2 = 7.87, p = .005) and formerly smoked (n = 126/152, 82.9%, χ2 = 6.67, p = .010). Sociodemographic characteristics by smoking history group are displayed in Supplementary File 1.

Perceived lung cancer stigma scores differed significantly by marital status (t[248] = −2.64, p = .001) such that unmarried participants reported significantly higher perceived stigma (M = 18.40, SD = 6.61) compared to married participants (M = 16.51, SD = 4.63). Additionally, race/ethnicity significantly differentiated participants on total stigma (t[256] = 2.50, p = .013) and internalized stigma (t[256] = 3.05, p = .003). Specifically, non-Hispanic white participants (compared to racial/ethnic minority participants) reported significantly higher total (M = 53.64, SD = 16.12 vs. M = 47.40, SD = 15.91) and internalized stigma (M = 25.70, SD = 9.96 vs. M = 21.03, SD = 9.61). Finally, depressive symptoms were correlated significantly with total stigma and all lung cancer stigma subscale scores (r = .31–.40, all p < .001). There were no differences in lung cancer stigma scores by education (all p > .65) or gender (all p > .16). Stigma was not associated significantly with age (all p > .46). Based on these findings, education, marital status, and race/ethnicity were included in addition to a priori covariates (i.e., age, sex, and depressive symptoms) in all subsequent analyses.

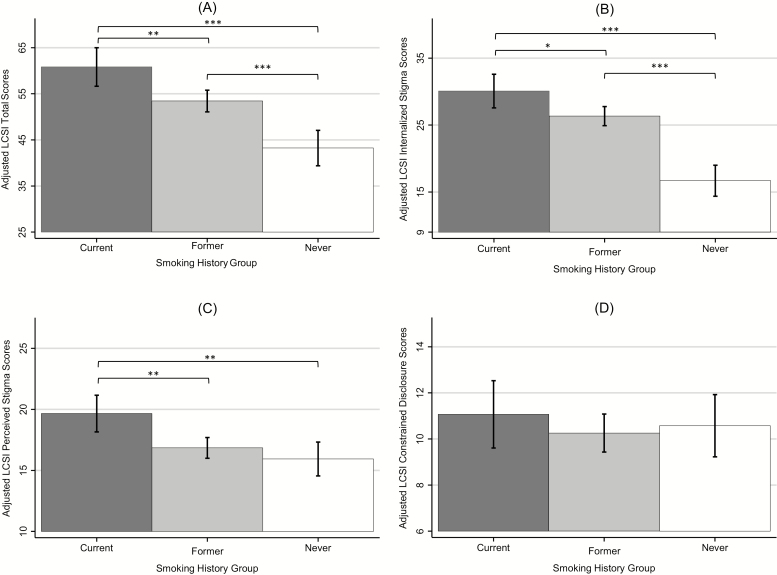

Differences in Lung Cancer Stigma by Smoking History

Multivariable regressions indicated that smoking history significantly differentiated participants on total lung cancer stigma (ΔR2 = .11, F[2, 235] = 18.53, p < .001), internalized stigma (ΔR2 = .19, F[2, 235] = 33.24, p < .001), and perceived stigma (ΔR2 = .05, F[2, 234] = 6.93, p = .001) beyond covariates (see Fig. 1). Smoking history did not differentiate participants on constrained disclosure (ΔR2 < .01, F[2, 235] = 0.46, p = .630). Raw and adjusted group means for stigma total and subscale scores are shown in Supplementary File 2.

Fig. 1.

Adjusted mean scores of lung cancer stigma. Total stigma (A), internalized stigma (B), perceived stigma (C), and constrained disclosure (D) by smoking history group. Results are adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status, race/ethnicity, and depressive symptoms. Error bars reflect 95% confidence intervals. LCSI = Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Participants who currently smoked reported significantly higher total lung cancer stigma scores than those who formerly (b = 7.39, standard error [SE] = 2.44, p = .003) and never smoked (b = 17.59, SE = 2.94, p < .001). Additionally, participants who formerly smoked reported significantly higher total lung cancer stigma scores than those who never smoked (b = 10.19, SE = 2.31, p < .001). Participants who currently smoked reported significantly higher internalized stigma than those who formerly (b = 3.74, SE = 1.47, p = .012) and never smoked (b = 13.40, SE = 1.77, p < .001). Similarly, participants who currently smoked reported significantly higher perceived stigma than those who formerly (b = 2.82, SE = 0.88, p = .002) and never smoked (b = 3.73, SE = 1.06, p = .001). Participants who formerly smoked evidenced higher internalized stigma than those who never smoked (b = 9.67, SE = 1.40, p < .001); however, participants who formerly smoked did not differ significantly from those who never smoked on perceived stigma (b = 0.91, SE = 0.84, p = .276). A significantly greater proportion of participants who currently (n = 46/49, 93.9%) or formerly smoked (n = 129/151, 85.4%) evidenced clinically meaningful lung cancer stigma compared to those who never smoked (n = 36/60, 60.0%, χ2 = 16.29–16.61, all p < .001).

Covariates

Higher depressive symptoms were associated significantly with higher lung cancer stigma scores in all models (b = 0.24–0.90, all p < .001), adjusting for other covariates and smoking history. Unmarried (vs. married) participants reported significantly higher levels of perceived stigma (b = 1.51, SE = 0.75, p = .046). All other relationships between covariates and stigma scores were not statistically significant in fully adjusted models (all p > .19).

Discussion

Clinically meaningful lung cancer stigma (total lung cancer stigma score ≥37.5) was experienced by the majority of participants who currently (93.9%), formerly (85.4%), and never smoked (60.0%). Based on prior work, this cutpoint demonstrates optimal sensitivity (0.93) and specificity (0.70) in predicting which patients also experience clinically significant levels of depressed mood [7]. As predicted, smoking history differentiated patients on total, internalized, and perceived lung cancer stigma, adjusting for age, sex, education, marital status, race/ethnicity, and depressive symptoms. These findings and those of Williamson et al. [8] suggest that internalized stigma is highest among lung cancer patients who currently smoke, followed by those who formerly smoked, and then by those who never smoked. Perceived stigma was higher among patients who currently smoked compared to those who formerly or never smoked, which is a novel finding. Additionally, both studies demonstrated that constrained disclosure did not differ significantly between smoking history groups [8]. These studies used different measures to assess lung cancer stigma and were conducted in independent samples, which builds confidence in the emerging evidence that patients’ smoking history is associated with certain (but not all) facets of lung cancer stigma.

Participants who currently smoked endorsed the highest levels of total, internalized, and perceived stigma and were most likely to experience clinically meaningful stigma. Findings are consistent with qualitative research [2]. Notably, cigarette smoking is a stigmatized behavior in and of itself [16]. Therefore, lung cancer patients who smoke may face a “double-hit” of being stigmatized for their smoking in addition to their disease status, emphasizing the importance of delivering nonstigmatizing smoking cessation efforts for lung cancer patients [17]. Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, unmarried participants reported higher levels of perceived stigma than married participants, over and above smoking history, depressive symptoms, and other covariates. These findings indicate that unmarried participants may need additional psychosocial support, and future research should investigate potential buffering effects of spousal support. No other sociodemographic characteristic (e.g., age, sex, race/ethnicity, education) was associated with stigma in fully adjusted models.

Interestingly, lung cancer patients endorsed similar levels of constrained disclosure across smoking history groups, which suggests that the experience of constrained disclosure is a pervasive aspect of lung cancer stigma. Indeed, prior research has shown that patients feel constrained in sharing information about their lung cancer diagnosis with acquaintances [2], medical providers [2], and/or close loved ones [18]. Future studies should further investigate the many possible reasons that lead to constrained disclosure [2, 13] and whether these reasons vary by smoking history. Routine assessment of smoking behavior is essential for high-quality lung cancer screening and treatment, and research is needed to identify how medical professionals can communicate with patients about their smoking history without making the patients feel stigmatized [17]. Our team is developing an empathic communication skills module designed to reduce stigma and facilitate acceptance of referral for tobacco treatment services.

Regarding implications for practice, most participants experienced stigma and may benefit from psychosocial support (particularly around constrained disclosure). Notably, lung cancer patients who smoke at diagnosis might be identified for additional psychosocial support that aims to reduce internalized stigma and promote engagement with smoking cessation interventions. This study also advances theoretical understanding of lung cancer stigma specifically [2] and health-related stigma broadly [1] through identifying internalized and perceived stigma as facets of stigma that vary meaningfully by patterns of health behaviors (e.g., smoking) associated with the stigmatized disease. A notable limitation is that data were cross-sectional; longitudinal research is needed to clarify temporal relationships between smoking history (including length of time since smoking cessation), smoking behavior change, and stigma. Additional work is needed to test whether these findings are generalizable outside of NCI-designated cancer centers (e.g., rural settings, community oncology practices). Strengths of this study include its use of a lung cancer stigma measure with strong psychometric properties, its large subsample of participants who currently smoke, and its inclusion of sociodemographic and psychological covariates.

In conclusion, these findings showed that lung cancer stigma is experienced by most patients, particularly among (but not limited to) those who currently smoked. This study sets the stage for future research to further characterize the psychosocial and behavioral correlates of health-related stigma and to develop targeted psychosocial interventions to reduce stigma and improve health and well-being for lung cancer patients.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Lung Cancer Partnership and the National Cancer Institute (T32CA009461; P30CA008748; R03CA193986; R03CA154016; K07CA207580; P30CA023074; P30CA142543). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. There are no other financial disclosures.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

Study concept and design: T. J. Williamson, H. A. Hamann, J. S. Ostroff Acquisition and/or interpretation of data: All authors Statistical analysis: T. J. Williamson Drafting of the manuscript: T. J. Williamson Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors Data visualization: T. J. Williamson Project administration: H. A. Hamann, J. S. Ostroff Supervision:H. A. Hamann, J. S. Ostroff

Ethical Approval All research was conducted in adherence with ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2000.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank those who participated in this research.

References

- 1. Van Brakel WH. Measuring health-related stigma—A literature review. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11:307–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hamann HA, Ostroff JS, Marks EG, Gerber DE, Schiller JH, Lee SJ. Stigma among patients with lung cancer: A patient-reported measurement model. Psychooncology. 2014;23:81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chambers SK, Dunn J, Occhipinti S, et al. . A systematic review of the impact of stigma and nihilism on lung cancer outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Conlon A, Gilbert D, Jones B, Aldredge P. Stacked stigma: Oncology social workers’ perceptions of the lung cancer experience. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2010;28:98–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hamann HA, Shen MJ, Thomas AJ, Craddock Lee SJ, Ostroff JS. Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of a patient-reported outcome measure for lung cancer stigma: The lung cancer stigma inventory (LCSI). Stigma Health. 2018;3:195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sriram N, Mills J, Lang E, et al. . Attitudes and stereotypes in lung cancer versus breast cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ostroff JS, Riley KE, Shen MJ, Atkinson TM, Williamson TJ, Hamann HA. Lung cancer stigma and depression: Validation of the Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory. Psychooncology. 2019;28:1011–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williamson TJ, Choi AK, Kim JC, et al. . A longitudinal investigation of internalized stigma, constrained disclosure, and quality of life across 12 weeks in lung cancer patients on active oncologic treatment. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1284–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Criswell KR, Owen JE, Thornton AA, Stanton AL. Personal responsibility, regret, and medical stigma among individuals living with lung cancer. J Behav Med. 2016;39:241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cataldo JK, Jahan TM, Pongquan VL. Lung cancer stigma, depression, and quality of life among ever and never smokers. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:264–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown Johnson CG, Brodsky JL, Cataldo JK. Lung cancer stigma, anxiety, depression, and quality of life. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2014;32:59–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. LoConte NK, Else-Quest NM, Eickhoff J, Hyde J, Schiller JH. Assessment of guilt and shame in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer compared with patients with breast and prostate cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2008;9:171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gray RE, Fitch M, Phillips C, Labrecque M, Fergus K. To tell or not to tell: Patterns of disclosure among men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2000;9:273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cataldo JK, Slaughter R, Jahan TM, Hwang WJ. Measuring stigma in people with lung cancer: Psychometric testing of the cataldo lung cancer stigma scale. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;1:46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Björgvinsson T, Kertz SJ, Bigda-Peyton JS, McCoy KL, Aderka IM. Psychometric properties of the CES-D-10 in a psychiatric sample. Assessment. 2013;20:429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stuber J, Galea S, Link BG. Smoking and the emergence of a stigmatized social status. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:420–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamann HA, Ver Hoeve ES, Carter-Harris L, Studts JL, Ostroff JS. Multilevel opportunities to address lung cancer stigma across the cancer control continuum. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1062–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Badr H, Taylor CL. Social constraints and spousal communication in lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.