Abstract

Background

Multiple chronic conditions may erode physical functioning, particularly in the context of complex self-management demands and depressive symptoms. Yet, little is known about how discordant conditions (i.e., those with management requirements that are not directly related and increase care complexity) among couples are linked to functional disability.

Purpose

We evaluated own and partner individual-level discordant conditions (i.e., discordant conditions within individuals) and couple-level discordant conditions (i.e., discordant conditions between spouses), and their links to levels of and change in functional disability.

Methods

The U.S. sample included 3,991 couples drawn from nine waves (1998–2014) of the Health and Retirement Study. Dyadic growth curve models determined how individual-level and couple-level discordant conditions were linked to functional disability over time, and whether depressive symptoms moderated these links. Models controlled for age, minority status, education, each partner’s baseline depressive symptoms, and each partner’s number of chronic conditions across waves.

Results

Wives and husbands had higher initial disability when they had their own discordant conditions and when there were couple-level discordant conditions. Husbands also reported higher initial disability when wives had discordant conditions. Wives had a slower rate of increase in disability when there were couple-level discordant conditions. Depressive symptoms moderated links between disability and discordant conditions at the individual and couple levels.

Conclusions

Discordant chronic conditions within couples have enduring links to disability that partly vary by gender and depressive symptoms. These findings generate valuable information for interventions to maintain the well-being of couples managing complex health challenges.

Keywords: Chronic illness, Spouses, Disability, Multimorbidity

Chronic conditions with discordant self-management requirements within individuals and between spouses are linked to functional disability, and these links partly vary by gender and depressive symptoms.

Introduction

Multimorbidity, or having at least two chronic conditions, affects almost half (42%) of adults in the USA [1]. Multimorbidity is linked to higher rates of hospitalization, disability, and mortality [2, 3]. Multiple chronic conditions may be especially challenging to manage when they involve discordant treatment goals (e.g., reducing pain vs. lowering blood pressure) which are not directly related and heighten care complexity [4–7]. Multimorbidity also contributes to depressive symptoms that further magnify risk of poor functional health [8–11]. Functional disability (i.e., difficulty with activities of daily living) is a key health indicator because it erodes independence and limits one’s ability to participate in everyday tasks related to home, work, and/or leisure domains that are central to well-being [12]. Interventions targeting depression among people with multimorbidity may improve their physical function [13, 14]. Hence, it is imperative to consider the role of depressive symptoms in shaping long-term links between multimorbidity and functional disability.

There is increasing recognition that spouses influence one another’s mental and physical health [15–18]. Nonetheless, little is known about the implications of multimorbidity patterns within couples for functional disability. We evaluated how chronic conditions with discordant self-management requirements at the individual level (i.e., within individuals) and at the couple level (i.e., between spouses) are associated with disability over a 16 year period, and whether these links are moderated by depressive symptoms.

The concordant–discordant model of comorbidities proposes that multimorbidity is more difficult to manage in the context of conditions that have treatment goals and self-management requirements that are discordant, or not directly related [7]. Concordant conditions represent parts of the same pathophysiological risk profile and share treatment goals that are likely to be the focus of an overall disease management plan. When a person has diabetes and hypertension, for instance, cardiovascular risk reduction activities (e.g., monitoring blood pressure and cholesterol levels) are a major aspect of managing these conditions that can be treated synergistically. Although diabetes requires a number of other self-management activities (e.g., blood glucose monitoring and insulin injections), cardiovascular risk reduction is a crucial component of disease management for both diabetes and hypertension. By contrast, discordant conditions (e.g., diabetes and arthritis) are not directly related in their pathogenesis or self-management. Consequently, a wider range of strategies is needed for discordant conditions that competes with limited resources and complicates decisions about prioritizing self-management tasks, possibly amplifying the risk of adverse outcomes [4, 7]. A person with diabetes and arthritis, for example, may manage pain and joint stiffness which does not directly support diabetes management and may take time and energy from effectively carrying out diabetes-related management activities. Consistent with the concordant–discordant model, among chronic kidney disease patients, discordant conditions have been linked to increased rates of emergency department visits, hospitalization, and death [5]. Likewise, the number of conditions discordant with cardiovascular risk has been associated with poorer lipid management [6].

Comorbid depressive symptoms may exacerbate the long-term link between discordant conditions and disability for several reasons. People who have both multimorbidity and elevated depressive symptoms lack motivation and energy, and thus, are less likely to initiate and sustain illness management activities that maintain physical function [19–22]. Depressive symptoms might also either take clinical priority that detracts from the self-management of chronic health problems or be undertreated because of complex medical issues that dominate treatment plans [7]. Moreover, the management of chronic medical illness and comorbid depressive symptoms is not typically integrated, and so individuals often have difficulty enacting self-care goals (e.g., increasing physical activity) that are broadly beneficial [20]. Over time, the complex self-management challenges faced by individuals with both discordant conditions and higher depressive symptoms may contribute to worse trajectories of functional disability.

Wives’ and husbands’ discordant conditions may have implications for their own and their partners’ functional disability, especially in the presence of depressive symptoms. Medical morbidity, depressive symptoms, and functional limitations are interrelated and show cross-partner associations over time among older couples [15–18]. Considering this spousal interdependence, one spouse’s discordant conditions might disrupt the self-care of each partner, making them both more vulnerable to functional decline. Couple-level discordance in which one or more discordant conditions are present between spouses might also complicate self-care routines in the marriage, potentially accelerating disability among both partners. As one example, a wife with diabetes may need to follow a low-sugar diet that is not required for her husband with lung disease. This may result in dietary changes within the couple that her husband might not support, which in turn complicates her diabetes self-management. Wives and husbands with higher depressive symptoms may be most susceptible to functional decline when there are individual-level and/or couple-level discordant conditions within the marriage because they have fewer internal resources to buffer these effects.

Wives may be most at risk of increased disability in the presence of their own and their partners’ discordant conditions and couple-level discordant conditions, particularly when they have higher depressive symptoms. Relative to husbands, wives receive less family support in managing their own medical conditions and depressive symptoms, are less likely to care for themselves when ill, and report more family-related barriers to self-care [23–25]. Furthermore, compared with husbands, wives provide more caregiving and emotional support in response to their partners’ health problems [24, 26] that may diminish their own well-being and functioning. Accordingly, wives may have higher initial disability and develop incident disability at a faster rate than husbands when there are discordant conditions within the couple, and these links may be intensified when wives report greater depressive symptoms.

Research using a subsample of the data analyzed in the present manuscript showed that individual-level discordant conditions were linked to higher depressive symptoms among both wives and husbands, and these links became stronger across an 8 year period [27]. Beyond these associations, couple-level discordant conditions were also associated with higher depressive symptoms among husbands. Therefore, it is important to consider whether individual-level and couple-level discordant conditions are more strongly linked to functional disability over time in the presence of higher levels of depressive symptoms that may amplify health risks.

This study evaluated how individual-level and couple-level discordant conditions are linked to initial levels of and change in functional disability over a 16 year period. We also considered the moderating role of depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that wives and husbands would report higher baseline disability and greater increases in disability when they or their partners had discordant conditions and when there were discordant conditions between spouses. We predicted that these links would be exacerbated for wives and husbands when their own baseline depressive symptoms were high. Finally, we predicted that the aforementioned associations would be stronger for wives than husbands.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

This study included a U.S. sample of 3,991 heterosexual married or cohabiting couples from nine waves (1998–2014) of the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study (HRS). The HRS has collected data biennially since 1992 with a response rate of over 80% at each wave. Participants are provided with a written study information document prior to each interview. At the beginning of each interview, participants are read a confidentiality statement and give oral consent by agreeing to be interviewed. In line with the University of Michigan’s policies, internal review board approval was not required for this paper because we used publicly available secondary data with no individual identifiers.

In 1998, phone interviews were conducted with 21,384 participants, of whom 13,820 (65%) were married and 551 (3%) had a cohabiting partner. Of these, 13,854 (96%) had partners who also completed an interview in 1998. Thirty individuals in same-sex couples were removed from analyses. A total of 10,042 participants from unique households were married to or cohabiting with the same partner (hereafter referenced as spouse) in 1998 and participated in at least three consecutive waves with this spouse beginning in 1998 through up to 2014.

Of the 10,042 participants, 2,060 were removed due to missing data, resulting in an analytic sample of 3,991 wives and husbands (see Table 1 for baseline characteristics and scores on study variables) with complete data at baseline and for at least three consecutive waves (i.e., 1998, 2002, and 2004). On average, couples participated in seven waves (SD = 2.2; range = 3–9). We included data from all waves in which both partners had complete data in order to assess the couple as the unit of analysis [28]. Most participants (97%) were married at baseline and were aged 50 or older (90.9% of wives and 98.5% of husbands). The age range for wives was 25 to 94 years and the age range for husbands was 25 to 96 years. Although a small percentage (5.3%) of participants were under 50 at baseline, almost one in five (18.0%) of U.S. adults aged 18–44 have two or more chronic conditions [1] and disability affects a substantial portion of younger adults (e.g., 16.0% aged 18–34 and 19.0% aged 35–44 among non-Hispanic Whites, and 17.3% aged 18–34 and 25.7% aged 35–44 among Blacks) [29].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and scores on study variables for wives and husbands

| Variable | Wives | Husbands | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age | 61.1** | 9.3 | 64.5 | 8.8 |

| Education in years | 12.6* | 2.8 | 12.7 | 3.3 |

| Number of chronic health conditions | 1.3** | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.3** | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.5 |

| Functional disability | 0.3* | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| % | % | |||

| Minority status | 11.0 | 11.3 | ||

| Individual-level discordant conditions | 34.4 | 35.7 | ||

| Couple-level discordant conditions | 51.5 | 51.5 |

Note. N = 3,991 couples.

*Significant gender difference at p < .05.

**Significant gender difference at p < .001.

We tested whether the participants in this study were different from the 2,675 married or partnered individuals who had complete data at baseline but not for at least three consecutive study waves. Wives and husbands who were younger (wives: b = −0.04, p < .001; husbands: b = −0.04, p < .001), non-Hispanic White (wives: b = −0.25, p = .012; husbands: b = −0.26, p = .008), had a spouse with fewer chronic conditions (wives: b = −0.25, p < .001; husbands: b = −0.11, p = .019), had fewer depressive symptoms (wives: b = −0.06, p = .001; husbands: b = −0.10, p < .001), had a spouse with fewer depressive symptoms (wives: b = −0.13, p < .001; husbands: b = −0.08, p < .001), had couple-level discordant conditions (wives: b = 0.13, p = .004; husbands: b = 0.12, p = .008), and had less disability (wives: b = −0.10, p = .001; husbands: b = −0.14, p < .001) were significantly more likely to be included in this study. For wives only, those who were more educated (b = 0.03, p = .007) and had a spouse with discordant conditions (b = 0.11, p = .038) were significantly more likely to be included in this study. For husbands only, those who had fewer chronic conditions (b = −0.21, p < .001) and had discordant conditions (b = 0.12, p = .023) were significantly more likely to be included in this study.

Measures

Functional disability

Participants reported whether they had difficulty (1 = yes, 0 = no) with six activities of daily living (ADL; walking across the room, dressing, bathing, eating, getting in and out of bed, and using the toilet) and five instrumental activities of daily living (IADL; preparing meals, shopping for groceries, making phone calls, taking medications, and handling money) that have good reliability and construct validity [30]. Summed scores for total ADL/IADL disability were created at each wave. Compared with using ADL as a measure of disability, an ADL/IADL scale has better content validity and greater sensitivity by age [31].

Time

Time (year centered at baseline in 1998) was considered as a predictor to examine rate of change in disability across the 16 year period.

Individual-level and couple-level discordant chronic conditions

At each wave, participants reported whether they had been diagnosed by a physician with seven major chronic health conditions: arthritis, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, lung disease, and stroke. These chronic conditions were selected to be regularly assessed in the HRS on the basis of their prevalence and strong associations with disability and mortality [32]. Individual-level discordant conditions occurred when individuals had one or more conditions with discordant management requirements (1 = yes, −1 = no) based on previous literature [6–8, 33]. Couple-level discordant conditions occurred when participants reported having one or more conditions that are discordant from one or more of their spouses’ conditions (1 = yes, −1 = no). Diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and stroke are all considered to be concordant with one another because they share the self-management goal of cardiovascular risk reduction, and the remaining combinations of conditions are considered to be discordant. There were a total of 15 possible pairs of discordant chronic conditions (see Table 2). We considered both own and partner individual-level discordant conditions and couple-level discordant conditions at baseline.

Table 2.

Individual-level and couple-level discordant conditions among wives and husbands at baseline

| Pairs of discordant conditions | Wife | Husband | Couple |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |

| Arthritis–Cancer | 5.7 | 5.1 | 9.5 |

| Arthritis–Diabetes | 5.7** | 7.5 | 12.0 |

| Arthritis–Heart disease | 8.8*** | 12.9 | 18.2 |

| Arthritis–Hypertension | 24.1* | 22.1 | 37.6 |

| Arthritis–Lung disease | 4.9 | 4.1 | 7.1 |

| Arthritis–Stroke | 1.8 | 2.2 | 4.0 |

| Cancer–Diabetes | 1.2 | 1.6 | 2.2 |

| Cancer–Heart disease | 1.7** | 2.8 | 3.9 |

| Cancer–Hypertension | 4.5 | 4.3 | 8.6 |

| Cancer–Lung disease | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.3 |

| Cancer–Stroke | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Lung disease–Diabetes | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| Lung disease–Heart disease | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.8 |

| Lung disease–Hypertension | 3.6* | 2.7 | 5.9 |

| Lung disease–Stroke | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

Note. Fifteen possible pairs of discordant conditions within individuals and between spouses are presented. Individuals and couples with one or more pairs of discordant conditions were categorized as having discordant conditions. N = 3,991 couples.

*Significant gender difference at p < .05.

**Significant gender difference at p < .01.

***Significant gender difference at p < .001.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed at baseline using the 8-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; 34). This widely used measure has been found to have good reliability and validity among middle-aged and older adults [34, 35]. Participants reported whether they had experienced the following symptoms much of the time in the past week: felt everything was an effort, had restless sleep, could not get going, felt depressed, felt lonely, felt sad, was happy, and enjoyed life. Ratings for the two positive items were reverse coded. Items were summed (wives α = 0.75; husbands α = 0.71).

Covariates

Covariates included baseline sociodemographic characteristics: age, minority status (1 = racial/ethnic minority, −1 = non-Hispanic White), and education in years. Models also controlled for own and partner baseline depressive symptoms and own and partner number of chronic health conditions at each wave.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated dyadic growth curve models using GENLIN in SPSS version 24 [28]. Multilevel models included the recommended two levels for longitudinal dyadic data, with the lower level representing variability due to within-person repeated measures for wives and husbands and the upper level representing between-couple variability. Models estimated robust standard errors and allowed correlated errors among individuals and between spouses in a given wave using an unstructured correlation matrix. We used a negative binomial distribution with log as the link function to adjust for low overall disability. This approach is commonly used when modeling count data outcomes which are overdispersed, meaning that the variance (e.g., wave 1 = 0.91; wave 9 = 3.57) is greater than the mean (e.g., wave 1 = 0.27; wave 9 = 0.74).

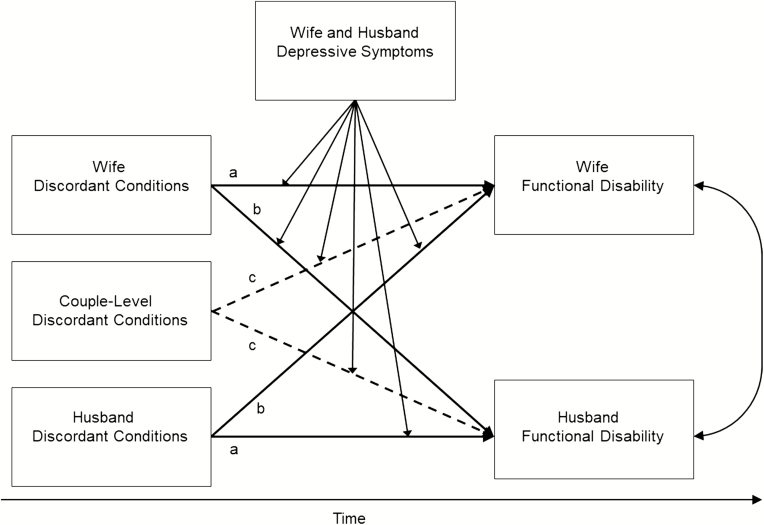

In this study, actor effects represent how wives’ and husbands’ own discordant conditions are linked to their own disability, whereas partner effects represent how their partners’ discordant conditions are linked to their own disability. We also considered how couple-level discordant conditions are linked to disability as a couple-level effect. We controlled for age, minority status, education, own and partner baseline depressive symptoms, and both partners’ number of chronic conditions at each wave. Figure 1 shows a simplified conceptual model for this study.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model showing how wives’ and husbands’ discordant chronic conditions and couple-level discordant chronic conditions are associated with functional disability over time. The moderating role of depressive symptoms was tested on actor effects (path a), partner effects (path b), and couple-level effects (path c) among wives and husbands.

Model 1 focused on individual-level discordant conditions as predictors and Model 2 added couple-level discordant conditions as a predictor. The first step determined how baseline individual-level discordant conditions (Model 1) and couple-level discordant conditions (Model 2) are linked to initial disability. The second step examined how baseline individual-level discordant conditions (Model 1) and couple-level discordant conditions (Model 2) are linked to change in disability over time. Interaction terms (time X actor discordant conditions and time X partner discordant conditions in Model 1; time X couple discordant conditions was added in Model 2) tested whether baseline discordant conditions are linked to rates of change in disability.

The third step tested the moderating effects of wives’ and husbands’ baseline depressive symptoms on links between discordant conditions and initial disability. We entered interaction terms (actor discordant conditions X actor depressive symptoms and partner discordant conditions X actor depressive symptoms in Model 1; couple discordant conditions X actor depressive symptoms was added in Model 2) to test whether own depressive symptoms moderated how own and partner baseline discordant conditions (Model 1) and couple-level discordant conditions (Model 2) are linked to wives’ and husbands’ initial disability. In the fourth step, three-way interactions (time X actor discordant conditions X actor depressive symptoms; time X partner discordant conditions X actor depressive symptoms in Model 1; time X couple discordant conditions X actor depressive symptoms was added in Model 2) tested whether own depressive symptoms moderated how own and partner baseline discordant conditions (Model 1) and couple-level discordant conditions (Model 2) are linked to wives’ and husbands’ rate of change in disability. We included two-way interaction terms (time X actor depressive symptoms and time X partner depressive symptoms in Models 1 and 2) to account for the effects of own and partner depressive symptoms over time.

We used a distinguishing variable to estimate separate intercepts and slopes for wives and husbands (1 = wife, −1 = husband). Continuous baseline covariates were grand mean centered and continuous time-varying covariates were person-level mean centered. We explored the nature of significant interactions by testing the statistical significance of links between discordant conditions and disability at the individual and couple levels when baseline depressive symptoms were low (score of 0) versus high (score of 3, one standard deviation above the mean). For significant three-way interactions, we estimated the model with a four-category variable representing each of four groups including low depressive symptoms (range = 0–2) and high depressive symptoms (range = 3–8) to compare the slopes [1]: no discordant conditions + low depressive symptoms [2]; no discordant conditions + high depressive symptoms [3]; discordant conditions + low depressive symptoms [4]; discordant conditions + high depressive symptoms.

Results

Baseline characteristics and scores on study variables are shown in Table 1. Paired t tests and McNemar tests were performed to examine baseline gender differences. Compared with husbands, wives were significantly younger, had less education, reported fewer chronic conditions, had greater depressive symptoms, and reported more disability.

Table 2 displays the baseline frequency of 15 possible combinations of discordant conditions. Arthritis and hypertension were the most common discordant conditions for wives and husbands. Relative to husbands, wives were significantly less likely to have arthritis and diabetes, arthritis and heart disease, or cancer and heart disease but were significantly more likely to have arthritis and hypertension or lung disease and hypertension.

Tables 3 and 4 present the dyadic growth curve model parameters for Models 1 and 2, respectively. Unstandardized coefficients, standard errors, incidence rate ratios (IRR), and confidence intervals (CI) are presented.

Table 3.

Dyadic growth curve model examining the effects of individual-level discordant conditions on wives’ and husbands’ functional disability

| Parameter | Wives | Husbands | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | IRR | 95% CI | b | SE | IRR | 95% CI | |

| Step 1 | ||||||||

| Time | 0.14*** | 0.01 | 1.15 | 1.12, 1.17 | 0.14*** | 0.01 | 1.15 | 1.13, 1.18 |

| Age | 0.05*** | 0.003 | 1.05 | 1.05, 1.06 | 0.06*** | 0.003 | 1.06 | 1.05, 1.06 |

| Minority status | 0.17*** | 0.03 | 1.18 | 1.12, 1.24 | 0.06* | 0.03 | 1.07 | 1.01, 1.12 |

| Education in years | −0.06*** | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.93, 0.95 | −0.07*** | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.93, 0.95 |

| Actor Number of chronic conditions | 0.15*** | 0.04 | 1.17 | 1.08, 1.26 | 0.31*** | 0.04 | 1.37 | 1.27, 1.47 |

| Partner Number of chronic conditions | 0.08* | 0.03 | 1.08 | 1.01, 1.15 | 0.14*** | 0.03 | 1.15 | 1.08, 1.23 |

| Actor Depressive symptoms | 0.21*** | 0.01 | 1.24 | 1.22, 1.26 | 0.23*** | 0.01 | 1.26 | 1.23, 1.28 |

| Partner Depressive symptoms | 0.03* | 0.01 | 1.03 | 1.01, 1.05 | 0.05*** | 0.01 | 1.05 | 1.03, 1.07 |

| Actor Discordant conditions | 0.36*** | 0.02 | 1.43 | 1.38, 1.49 | 0.28*** | 0.02 | 1.33 | 1.28, 1.38 |

| Partner Discordant conditions | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.98, 1.06 | 0.06** | 0.02 | 1.06 | 1.02, 1.10 |

| QICC | 51399.61 | |||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||

| Time X Actor Discordant conditions | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.97, 1.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.02 |

| Time X Partner Discordant conditions | 0.001 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.01 |

| QICC | 51397.64 | |||||||

| Step 3 | ||||||||

| Actor Discordant conditions X Actor Depressive symptoms | −0.001 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.01 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.02 |

| Partner Discordant conditions X Actor Depressive symptoms | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.03 |

| QICC | 51398.29 | |||||||

| Step 4 | ||||||||

| Time X Actor Discordant conditions X Actor Depressive symptoms | 0.01*** | 0.003 | 1.01 | 1.01, 1.02 | 0.01* | 0.004 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.01 |

| Time X Partner Discordant conditions X Actor Depressive symptoms | 0.001 | 0.003 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.01 |

| QICC | 51092.35 |

Note. Estimates are presented from each step in the analysis. Step 4 also included two-way interaction terms (time X actor depressive symptoms and time X partner depressive symptoms). N = 3,991 couples.

IRR incidence rate ratio; CI confidence interval; QICC Corrected Quasi-likelihood under Independence Model Criterion.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 4∙.

Dyadic growth curve model examining the effects of couple-level discordant conditions on wives’ and husbands’ functional disability

| Parameter | Wives | Husbands | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | IRR | 95% CI | b | SE | IRR | 95% CI | |

| Step 1 | ||||||||

| Time | 0.14*** | 0.01 | 1.15 | 1.13, 1.17 | 0.14*** | 0.01 | 1.15 | 1.13, 1.18 |

| Age | 0.05*** | 0.003 | 1.05 | 1.05, 1.06 | 0.05*** | 0.003 | 1.06 | 1.05, 1.06 |

| Minority status | 0.16*** | 0.03 | 1.18 | 1.12, 1.24 | 0.06* | 0.03 | 1.06 | 1.01, 1.12 |

| Education in years | −0.06*** | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.93, 0.95 | −0.07*** | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.93, 0.95 |

| Actor Number of chronic conditions | 0.16*** | 0.04 | 1.17 | 1.08, 1.26 | 0.31*** | 0.04 | 1.37 | 1.27, 1.47 |

| Partner Number of chronic conditions | 0.08* | 0.03 | 1.08 | 1.01, 1.15 | 0.15*** | 0.03 | 1.16 | 1.08, 1.24 |

| Actor Depressive symptoms | 0.21*** | 0.01 | 1.23 | 1.21, 1.25 | 0.23*** | 0.01 | 1.26 | 1.23, 1.28 |

| Partner Depressive symptoms | 0.03* | 0.01 | 1.03 | 1.01, 1.05 | 0.04*** | 0.01 | 1.04 | 1.03, 1.06 |

| Actor Discordant conditions | 0.32*** | 0.02 | 1.38 | 1.32, 1.43 | 0.24*** | 0.02 | 1.27 | 1.22, 1.32 |

| Partner Discordant conditions | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.94, 1.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.01 | 0.97, 1.05 |

| Couple Discordant conditions | 0.11*** | 0.03 | 1.11 | 1.06, 1.17 | 0.13*** | 0.02 | 1.13 | 1.08, 1.19 |

| QICC | 51281.84 | |||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||

| Time X Actor Discordant conditions | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.02 |

| Time X Partner Discordant conditions | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.02 | −0.003 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.01 |

| Time X Couple Discordant conditions | −0.02* | 0.01 | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.01 |

| QICC | 51271.44 | |||||||

| Step 3 | ||||||||

| Actor Discordant conditions X Actor Depressive symptoms | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.03 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.02 |

| Partner Discordant conditions X Actor Depressive symptoms | 0.02** | 0.01 | 1.02 | 1.01, 1.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.03 |

| Couple Discordant conditions X Actor Depressive symptoms | −0.03** | 0.01 | 0.97 | 0.95, 0.99 | −0.003 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.02 |

| QICC | 51263.34 | |||||||

| Step 4 | ||||||||

| Time X Actor Discordant conditions X Actor Depressive symptoms | 0.01** | 0.003 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.02 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.01 |

| Time X Partner Discordant conditions X Actor Depressive symptoms | 0.000 | 0.003 | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 |

| Time X Couple Discordant conditions X Actor Depressive symptoms | 0.003 | 0.004 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.01 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.02 |

| QICC | 50957.55 |

Note. Estimates are presented from each step in the analysis. Step 4 also included two-way interaction terms (time X actor depressive symptoms and time X partner depressive symptoms).

IRR incidence rate ratio; CI confidence interval; QICC Corrected Quasi-likelihood under Independence Model Criterion.

N = 3,991 couples. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Associations Between Individual-Level Discordant Conditions and Functional Disability

Wives’ functional disability

Table 3 (Model 1) shows that wives reported significantly higher initial disability when they had discordant conditions at baseline (b = 0.36, IRR = 1.43, p < .001, 95% CI [1.38, 1.49]). Husbands’ baseline discordant conditions were not significantly associated with wives’ initial level of disability.

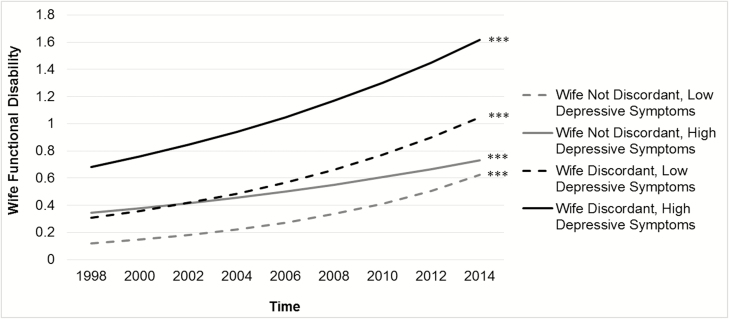

Wives’ depressive symptoms moderated the link between wives’ discordant conditions at baseline and their own rate of change in disability (b = 0.01, IRR = 1.01, p < .001, 95% CI [1.01, 1.02]). Figure 2 shows that significant increases in disability were found for wives with discordant conditions and high depressive symptoms (b = 0.11, IRR = 1.11, p < .001, 95% CI [1.09, 1.14]), wives with discordant conditions and low depressive symptoms (b = 0.15, IRR = 1.17, p < .001, 95% CI [1.14, 1.20]), wives without discordant conditions and with high depressive symptoms (b = 0.09, IRR = 1.10, p < .001, 95% CI [1.07, 1.13]), and wives without discordant conditions and with low depressive symptoms (b = 0.21, IRR = 1.23, p < .001, 95% CI [1.20, 1.26]). A comparison of the four slopes demonstrated that wives with discordant conditions and high depressive symptoms showed the highest level of disability but a slower rate of increase than wives without discordant conditions who had low depressive symptoms (b = −0.11, IRR = 0.90, p < .001, 95% CI [0.86, 0.93]) and wives with discordant conditions and low depressive symptoms (b = −0.07, IRR = 0.93, p < .001, 95% CI [0.90, 0.97]). Husbands’ baseline discordant conditions were not significantly associated with wives’ rate of change in disability.

Fig. 2.

Significant moderating effect of wives’ depressive symptoms on the link between their own discordant conditions at baseline and rate of change in disability. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) show wives’ rate of change in disability over time. ***p < .001.

Husbands’ functional disability

Table 3 (Model 1) shows that husbands reported significantly higher initial disability when they had discordant conditions at baseline (b = 0.28, IRR = 1.33, p < .001, 95% CI [1.28, 1.38]) and when wives had discordant conditions at baseline (b = 0.06, IRR = 1.06, p = .003, 95% CI [1.02, 1.10]).

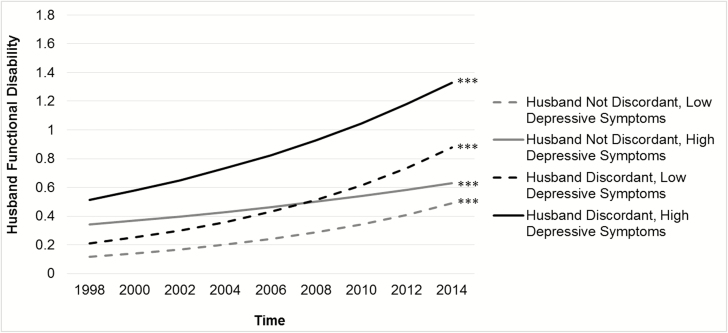

Husbands’ baseline depressive symptoms moderated the association between their own discordant conditions at baseline and rate of change in disability (b = 0.01, IRR = 1.01, p = .043, 95% CI [1.00, 1.01]). As displayed in Fig. 3, significant increases in disability were found for husbands with discordant conditions and high depressive symptoms (b = 0.12, IRR = 1.13, p < .001, 95% CI [1.10, 1.15]), husbands with discordant conditions and low depressive symptoms (b = 0.18, IRR = 1.20, p < .001, 95% CI [1.17, 1.22]), husbands without discordant conditions and with high depressive symptoms (b = 0.08, IRR = 1.08, p < .001, 95% CI [1.05, 1.11]), and husbands without discordant conditions and with low depressive symptoms (b = 0.18, IRR = 1.19, p < .001, 95% CI [1.16, 1.23]). A comparison of the slopes revealed that husbands with discordant conditions and high depressive symptoms showed the highest level of disability but a slower rate of increase than husbands without discordant conditions who had low depressive symptoms (b = −0.06, IRR = 0.94, p = .005, 95% CI [0.90, 0.98]) and husbands with discordant conditions and low depressive symptoms (b = −0.06, IRR = 0.95, p = .009, 95% CI [0.91, 0.99]). Husbands with discordant conditions and high depressive symptoms showed a faster rate of increase in disability than husbands without discordant conditions who reported high depressive symptoms (b = 0.10, IRR = 1.10, p = .001, 95% CI [1.04, 1.16]). Wives’ baseline discordant conditions were not significantly linked to husbands’ rate of change in disability.

Fig. 3.

Significant moderating effect of husbands’ depressive symptoms on the link between their own discordant conditions at baseline and rate of change in disability. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) show husbands’ rate of change in disability over time. ***p < .001.

Associations Between Couple-Level Discordant Conditions and Functional Disability

Wives’ functional disability

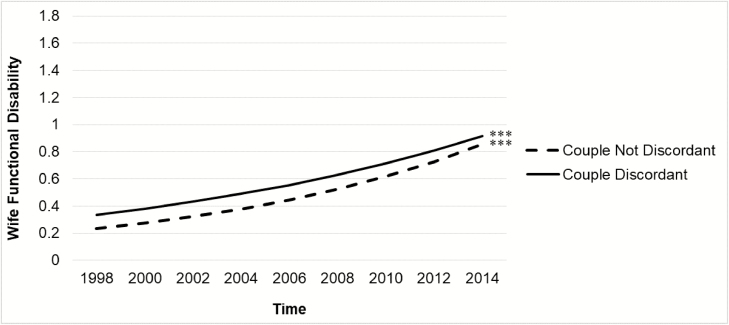

Table 4 (Model 2) shows that the interaction between time and couple-level discordant conditions was significant. When there were couple-level discordant conditions at baseline, wives had a significantly slower rate of increase in disability (b = −0.02, IRR = 0.98, p = .040, 95% CI [0.96, 1.00]). As depicted in Fig. 4, wives showed significant linear increases in disability but the rate of increase was higher when couple-level discordant conditions were absent (b = 0.16, IRR= 1.18, p < .001, 95% CI [1.14, 1.21]) than when they were present (b = 0.13, IRR = 1.13, p < .001, 95% CI [1.11, 1.16]).

Fig. 4.

Significant interaction of couple-level discordant conditions at baseline and wives’ rate of change in disability. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) show wives’ rate of change in disability over time. ***p < .001.

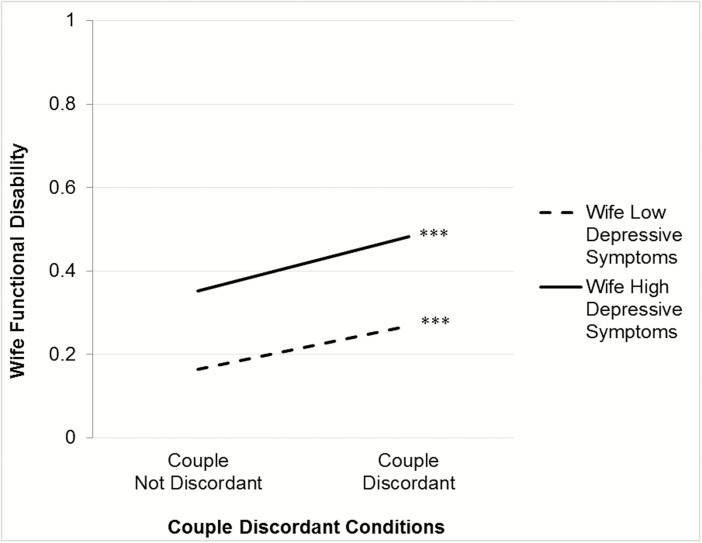

Wives’ baseline depressive symptoms moderated how couple-level discordant conditions were linked to their own initial disability (b = −0.03, IRR = 0.97, p = .007, 95% CI [0.95, 0.99]). Figure 5 shows that wives reported significantly higher initial disability when there were couple-level discordant conditions, but this link was stronger when wives’ depressive symptoms were low (b = 0.24, IRR = 1.27, p < .001, 95% CI [1.18, 1.37]) than when they were high (b = 0.16, IRR = 1.17, p < .001, 95% CI [1.08, 1.26]).

Fig. 5.

Significant moderating effect of wives’ depressive symptoms on the link between couple-level discordant conditions at baseline and their own initial disability. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) show wives’ initial level of disability. ***p < .001.

Husbands’ functional disability

Table 4 (Model 2) shows that husbands reported significantly higher initial disability when there were couple-level discordant conditions (b = 0.13, IRR = 1.13, p < .001, 95% CI [1.08, 1.19]). Couple-level discordant conditions were not significantly associated with husbands’ rate of change in disability. Husbands’ depressive symptoms did not moderate these associations.

Post Hoc Tests

We tested the dyadic growth curve models by adding four interaction terms (actor discordant conditions X partner depressive symptoms, time X actor discordant conditions X partner depressive symptoms, partner discordant conditions X partner depressive symptoms, and time X partner discordant conditions X partner depressive symptoms) in Model 1 and two interaction terms (couple discordant conditions X partner depressive symptoms and time X couple discordant conditions X partner depressive symptoms) in Model 2 to evaluate whether partner depressive symptoms moderated how own and partner discordant conditions and couple-level discordant conditions were linked to disability.

Partner depressive symptoms moderated the association between wives’ own discordant conditions and their initial disability (b = 0.03, IRR = 1.04, p = .002, 95% CI [1.01, 1.06]). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, wives had significantly higher levels of disability when they had discordant conditions; however, this association was intensified when husbands’ depressive symptoms were high (b = 0.47, IRR = 1.60, p < .001. 95% CI [1.53, 1.68]) rather than low (b = 0.37, IRR = 1.45, p < .001, 95% CI [1.38, 1.52]).

Partner depressive symptoms also moderated the association between partner discordant conditions and the rate of change in husbands’ disability (b = 0.01, IRR = 1.01, p = .049, 95% CI [1.00, 1.01]). Significant increases in husbands’ disability were found when wives had discordant conditions and high depressive symptoms (b = 0.14, IRR = 1.15, p < .001, 95% CI [1.12, 1.18]), wives had discordant conditions and low depressive symptoms (b = 0.14, IRR = 1.15, p < .001, 95% CI [1.12, 1.18]), wives without discordant conditions had high depressive symptoms (b = 0.12, IRR = 1.13, p < .001, 95% CI [1.10, 1.16]), and wives without discordant conditions had low depressive symptoms (b = 0.16, IRR = 1.18, p < .001, 95% CI [1.15, 1.21]). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, husbands had the highest initial level of disability which increased over time when wives had discordant conditions and high depressive symptoms, but the rate of increase did not differ significantly relative to the other three slopes.

Finally, we estimated the main models including 192 additional couples in which both partners had complete data at baseline (1998) and in at least two subsequent waves through 2014 that were not consecutive. Relative to the 3,991 couples in the main analysis, the 192 additional couples in this post hoc analysis included participants who were younger (wives: b = −0.04, p < .001, husbands: b = −0.04, p < .001), were more likely to be a racial/ethnic minority (wives: b = 0.37, p < .001, husbands: b = 0.39, p < .001), and had lower education (wives only: b = −0.07, p = .002). These participants did not differ in their baseline reports of own and partner depressive symptoms, own and partner number of chronic health conditions, own and partner individual-level discordant conditions, or couple-level discordant conditions. The same pattern of findings emerged with two exceptions. First, the association between couple-level discordant conditions at baseline and a slower rate of increase in functional disability over time among wives became marginally significant (b = −0.02, IRR = 0.98, p = .054, 95% CI: [0.97, 1.00]). Second, the interaction between partner discordance and actor depressive symptoms for husbands became significant (b = 0.02, IRR = 1.02, p = .047, 95% CI: [1.00, 1.04]). Husbands reported higher initial disability when wives had discordant conditions and husbands’ depressive symptoms were high (b = 0.09, IRR = 1.09, p = .011, 95% CI: [1.02, 1.17]) but not low (b = 0.04, IRR = 1.04, p = .276, 95% CI: [0.97, 1.12]).

Discussion

This study adds to the growing literature on health-related spousal interdependence by demonstrating that discordant chronic conditions are linked to functional disability within couples over time in ways that partly depend on gender and depressive symptoms. The findings were observed over and above sociodemographic factors and health characteristics such as both spouses’ number of chronic conditions, revealing robust associations. Roughly two-thirds of chronically ill older adults are married, and most have spouses with their own chronic conditions [36]. As such, it is critical to gain a more nuanced understanding of complex care and self-management needs within couples and their enduring implications for functional health.

Consistent with our hypothesis, wives and husbands reported higher initial disability when they had their own discordant conditions. These findings are in line with the concordant–discordant model and research showing that multiple chronic conditions are associated with adverse health outcomes when they have competing self-management goals that increase care complexity [4–7]. Extending this framework, wives and husbands also reported higher initial levels of disability when there were discordant conditions between spouses. In addition, husbands reported higher initial disability when wives had discordant conditions. Although we predicted that this association would be stronger for wives, partner discordant conditions may be linked to greater disability among husbands because they tend to be more dependent on their wives’ health-related support than vice versa [37, 38]. Indeed, men usually name a spouse or partner as their primary source of support, whereas women more often name people outside the marriage such as female friends and relatives [26]. When a wife has her own discordant conditions that require more complex self-management, she may be less able to effectively guide her husband’s self-care behaviors to protect his functional health.

Over time, wives showed a slower rate of increase in disability in the presence of couple-level discordant conditions, regardless of their depressive symptoms. One potential explanation for this somewhat counterintuitive finding is that wives with one or more discordant conditions from their husbands may sustain shared engagement in self-care behaviors recommended for their husbands’ health problems that aid in preserving their own functional health. For instance, a wife with arthritis who has a husband with heart disease might join her husband in various cardiovascular risk reduction activities to manage his health (e.g., following a low-salt diet and a regular exercise program) that mitigate her own trajectory of functional decline. Relatedly, when there are discordant conditions between spouses, wives may be more likely to use dyadic coping strategies (e.g., managing each partner’s conditions as a team) that ultimately help us to maintain wives’ functional health. Supporting this possibility, research indicates that dyadic coping strategies are linked to better well-being among couples managing chronic illness, and that women may use these strategies more frequently than men [39].

Wives had higher levels of initial disability when there were couple-level discordant conditions at baseline, but this link was weaker when wives reported high depressive symptoms. This finding is counter to our hypothesis that depressive symptoms would exacerbate the link between couple-level discordant conditions and disability. Considering the higher levels of disability among wives with high depressive symptoms, it is plausible that the strong link between depressive symptoms and disability may have minimized the association between couple-level discordant conditions and disability.

Post hoc tests showed that the association between wives’ discordant conditions and initial disability was stronger when husbands reported high depressive symptoms. Prior research suggests that wives provide more emotional support to husbands when husbands experience depression than vice versa [25]. When husbands have greater depressive symptoms, wives might prioritize their husbands’ well-being to the neglect of their own illness self-management. This may ultimately contribute to higher levels of disability among wives who must also manage their own complex care needs.

Unexpectedly, wives and husbands with discordant conditions and high depressive symptoms had a slower rate of increase in disability than their counterparts who reported low depressive symptoms with and without discordant conditions. Wives and husbands with discordant conditions and high depressive symptoms have higher initial disability, which may result in a relatively lower capacity for increased disability. Alternatively, comorbid depressive symptoms are linked to higher healthcare utilization among older patients with chronic illness and multimorbidity [40, 41]. Thus, another tentative explanation is that wives and husbands with discordant conditions and elevated depressive symptoms may receive more frequent healthcare that attenuates incident disability. By contrast, husbands with discordant conditions and high depressive symptoms showed a faster rate of increase in disability than husbands without discordant conditions who reported high depressive symptoms. Discordant conditions might therefore play a substantial role in the development of incident disability among husbands with high levels of depressive symptoms. This may in part be due to poorer health-related self-management (e.g., a lower likelihood of avoiding high-fat foods, limiting salt intake, having health screening checks, and seeking advice from medical providers) among men than women [42, 43], which could be amplified in the context of complex care needs.

We acknowledge seven limitations. First, chronic conditions were self-reported using a restricted range, possibly underestimating the prevalence of individual-level and couple-level discordant conditions. Second, there was a low prevalence of discordant conditions, depressive symptoms, and functional disability, and so the findings may not generalize to couples with higher rates of discordant conditions, clinical depression, and/or severe disability. Third, couples in this study were married or cohabiting and heterosexual, limiting generalizability to couples who separate/divorce, noncohabiting partners, and same-sex couples. Fourth, most couples were non-Hispanic white, and so the findings may not generalize to more ethnically diverse couples. Fifth, relative to participants in this study, married or cohabiting participants who were excluded because of missing data differed in their sociodemographic and health characteristics, which may present bias. For example, excluded participants were older, were more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities, had fewer depressive symptoms, had a spouse with fewer depressive symptoms, and had greater disability. As a consequence, the findings might not apply to individuals and couples with these characteristics. Sixth, the magnitude of the effects was relatively small; yet even small effects may have a significant clinical and public health impact [44]. Last, the findings on individual-level discordant conditions may not generalize to individuals who do not have a partner. The presence of a partner in middle and later life is another potential source of bias in that those who are married and have stable marriages are more likely to be non-Hispanic white than a racial/ethnic minority [45]. Nevertheless, this study lays the groundwork for subsequent research to generate a more complete understanding of when and how discordant conditions are associated with disability among individuals and couples.

Future research should consider mechanisms that may account for the current findings. Elucidating short-term processes that explain how own and partner discordant conditions and couple-level discordant conditions are linked to disability among individuals with varying degrees of depressive symptoms would be particularly informative. Such pathways may involve modifiable factors (e.g., physical activity) that can be targeted during interventions to maintain both partners’ health and functioning. Pinpointing unique circumstances under which couples are more or less resilient to discordant conditions along with effective coping resources (e.g., self-efficacy) are key directions for future work.

Another important area for future research is to explore the concept of discordant conditions from the perspective of individuals and partners in their daily lives. Identifying aspects of discordance in day-to-day illness management at individual and couple levels that have the greatest impact on self-care would advance knowledge of how and why discordant conditions are associated with disability. Qualitative and mixed method studies in which individuals and couples describe their experiences also hold considerable promise in developing more fine-grained definitions and measures of discordance.

In summary, discordant conditions within couples have distinct implications for functional disability that partly differ by gender and depressive symptoms. Devising strategies to promote functional health among couples with complex self-management demands may help preserve their well-being and independent functioning.

Supplementary Material

Prior presentation

The findings from this paper were presented in part at the 126th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association in San Francisco, CA in 2018.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers P30AG012846 and R03AG057838-01).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M.. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bähler C, Huber CA, Brüngger B, Reich O. Multimorbidity, health care utilization and costs in an elderly community-dwelling population: A claims data based observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marengoni A, von Strauss E, Rizzuto D, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. The impact of chronic multimorbidity and disability on functional decline and survival in elderly persons. A community-based, longitudinal study. J Intern Med. 2009;265:288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boyd CM, Fortin M. Future of multimorbidity research: How should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design. Public Health Rev. 2010;32:451–474. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowling CB, Plantinga L, Phillips LS, et al. . Association of multimorbidity with mortality and healthcare utilization in chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lagu T, Weiner MG, Hollenbeak CS, et al. . The impact of concordant and discordant conditions on the quality of care for hyperlipidemia. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1208–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, Lapointe L, Dubois MF, Almirall J. Psychological distress and multimorbidity in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Quiñones AR, Markwardt S, Botoseneanu A. Multimorbidity combinations and disability in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:823–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quiñones AR, Markwardt S, Thielke S, Rostant O, Vásquez E, Botoseneanu A. Prospective disability in different combinations of somatic and mental multimorbidity. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. 2018;73:204–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith DJ, Court H, McLean G, et al. . Depression and multimorbidity: A cross-sectional study of 1,751,841 patients in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:1202e1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gallo JJ, Hwang S, Joo JH, et al. . Multimorbidity, depression, and mortality in primary care: Randomized clinical trial of an evidence-based depression care management program on mortality risk. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:380–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith SM, Wallace E, O’Dowd T, Fortin M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD006560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoppmann CA, Gerstorf D, Hibbert A. Spousal associations between functional limitation and depressive symptom trajectories: Longitudinal findings from the study of Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD). Health Psychol. 2011;30:153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Monin J, Doyle M, Levy B, Schulz R, Fried T, Kershaw T. Spousal associations between frailty and depressive symptoms: Longitudinal findings from the cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:824–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Polenick CA, Renn BN, Birditt KS. Dyadic effects of depressive symptoms on medical morbidity in middle-aged and older couples. Health Psychol. 2018;37:28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thomeer MB. Multiple chronic conditions, spouse’s depressive symptoms, and gender within marriage. J Health Soc Behav. 2016;57:59–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: Impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278–3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Detweiler-Bedell JB, Friedman MA, Leventhal H, Miller IW, Leventhal EA. Integrating co-morbid depression and chronic physical disease management: Identifying and resolving failures in self-regulation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:1426–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harrison M, Reeves D, Harkness E, et al. . A secondary analysis of the moderating effects of depression and multimorbidity on the effectiveness of a chronic disease self-management programme. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McKellar JD, Humphreys K, Piette JD. Depression increases diabetes symptoms by complicating patients’ self-care adherence. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30:485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosland AM, Heisler M, Choi HJ, Silveira MJ, Piette JD. Family influences on self-management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: Do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic Illn. 2010;6:22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomeer MB, Reczek C, Umberson D. Gendered emotion work around physical health problems in mid- and later-life marriages. J Aging Stud. 2015;32:12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomeer MB, Umberson D, Pudrovska T. Marital processes around depression: A gendered and relational perspective. Soc Ment Health. 2013;3:151–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Monin JK, Clark MS. Why do men benefit more from marriage than do women? Thinking more broadly about interpersonal processes that occur within and outside of marriage. Sex Roles. 2011;65:320–326. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Polenick CA, Birditt KS, Turkelson A, Bugajski BC, Kales HC. Discordant chronic conditions and depressive symptoms: Longitudinal associations among middle-aged and older couples. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 2019. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL.. Dyadic Data Analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taylor DM. Americans with disabilities: 2014. Household economic studies. Curr Popul Rep. 2018:P70–P152. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fonda S, Herzog AR.. Documentation of Physical Functioning Measured in the Health and Retirement Study and the Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old Study. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center University of Michigan; 2004. HRS/AHEAD Documentation Report. [Google Scholar]

- 31. LaPlante MP. The classic measure of disability in activities of daily living is biased by age but an expanded IADL/ADL measure is not. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65:720–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fisher GG, Faul JD, Weir DR, Wallace RB.. Documentation of Chronic Disease Measures in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS/AHEAD). Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center University of Michigan; 2005. HRS/AHEAD Documentation Report. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Polenick CA, Leggett AN, Webster NJ, Han BH, Zarit SH, Piette JD. Multiple chronic conditions in spousal caregivers of older adults with functional disability: Associations with caregiving difficulties and gains. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2017. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Steffick DE. Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center University of Michigan; 2000. HRS/AHEAD Documentation Report. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Karim J, Weisz R, Bibi Z, Rehman S. Validation of the eight-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) among older adults. Curr Psychol. 2015;34:681–692. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piette JD, Rosland AM, Silveira M, Kabeto M, Langa KM. The case for involving adult children outside of the household in the self-management support of older adults with chronic illnesses. Chronic Illn. 2010;6:34–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. August KJ, Sorkin DH. Marital status and gender differences in managing a chronic illness: The function of health-related social control. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1831–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Umberson D. Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:907–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Falconier MK, Kuhn R. Dyadic coping in couples: A conceptual integration and a review of the empirical literature. Front Psychol. 2019;10:571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bock JO, Luppa M, Brettschneider C, et al. . Impact of depression on health care utilization and costs among multimorbid patients–from the MultiCare Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Han KM, Ko YH, Yoon HK, Han C, Ham BJ, Kim YK. Relationship of depression, chronic disease, self-rated health, and gender with health care utilization among community-living elderly. J Affect Disord. 2018;241:402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Deeks A, Lombard C, Michelmore J, Teede H. The effects of gender and age on health related behaviors. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A, Nillapun M, Jonwutiwes K, Bellisle F. Gender differences in food choice: The contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rutledge T, Loh C. Effect sizes and statistical testing in the determination of clinical significance in behavioral medicine research. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Raley RK, Sweeney MM, Wondra D. The growing racial and ethnic divide in U.S. Marriage patterns. Future Child. 2015;25:89–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.