Abstract

Introduction:

Olfactory dysfunction (OD) is a common problem affecting up to 20% of the general population. Previous studies identified olfactory cleft mucus proteins associated with OD in chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) but not in a healthy population. This study aimed to identify olfactory cleft mucus proteins associated with olfaction in individuals without sinus disease.

Methods:

Subjects free of sinus disease completed medical history questionnaires collecting demographics, comorbidities and past exposures. Olfactory testing was performed using Sniffin’ Sticks evaluating threshold, discrimination and identification. Olfactory cleft mucus (OC) and in select cases inferior turbinate mucus (IT) was collected with Leukosorb paper and assays performed for 17 proteins, including growth factors, cytokines/chemokines, cell cycle regulators and odorant binding protein (OBP).

Results:

A total of 56 subjects were enrolled with an average age of 47.8 years (SD 17.6 years), and included 33 of females (58.9%). Average Threshold/Discrimination/Identification (TDI) score was 30.3 (SD 6.4). In localization studies, OBP concentrations were significantly higher in OC than IT mucus (p=0.006). Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A/p16INK4a), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2/MCP-1), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20/MIP-3a) all inversely correlated with overall TDI (all rho≥−0.479, p≤0.004). Stem cell factor (SCF) positively correlated with overall TDI (rho=0.510, p=0.002).

Conclusions:

Placement of leukosorb paper is relatively site specific for olfactory proteins and it is feasible to collect a variety of olfactory cleft proteins that correlate with olfactory function. Further study is required to determine mechanisms of OD in non-CRS subjects.

Keywords: Olfactory disorders, olfaction, olfactory test, nasal mucosa, cytokines, growth factor, hyposmia, anosmia

Introduction

Olfactory dysfunction (OD) is a significant and common problem in the general population, with one study finding OD affecting up to 20% of patients without sinonasal symptoms.1 While chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is one of the most common causes of OD, there are numerous other causes, including traumatic, viral, toxin exposure, smoking, allergic, neurodegenerative and idiopathic. Regardless of cause, the inability or decreased ability to smell has a significant influence on quality of life and nutrition due to diminished taste, which can lead to weight loss due to lack of interest in eating or weight gain due to increased intake to compensate for lack of sensory stimulation.2–6 Lack of olfaction can also become a safety issue, with one study finding that anosmics were 3 times more likely than normosmics to experience a life threatening situation due to inability to detect olfactory cues such as the odor of spoiled food and the smell of smoke or natural gas.2–3,7–8 Anosmia has also been associated with increased mortality in multiple studies, and OD has been associated with multiple neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive impairment, Parkinson’s disease, frontotemporal degeneration and Huntington’s disease.4,9–10 There has been recent interest in using olfaction as a prognosticator and predictor of clinical outcomes in these neurodegenerative disorders.2,11

Though the impact of OD is evident, it is likely that most etiologies involve multi-factorial mechanisms. CRS-associated OD for example, can be obstructive due to polyps or edema, but also appears to have inflammatory mechanisms independent of obstructed airflow.12–13 Improved understanding of the mechanisms playing a role in various types of OD requires assessment of the local microenvironment of the olfactory neuroepithelium. The study of olfactory cleft mucus is advantageous because it can be collected in a minimally invasive fashion and thus could serve as a potential avenue for future diagnostic and prognostic testing. Investigations related to CRS have found that multiple inflammatory mediators in olfactory cleft mucus are associated with OD, likely reflecting tissue eosinophilia and type 2 inflammation.12–16 Non-CRS related OD likely occurs via different mechanisms which could include changes in the olfactory epithelium with decreases in number of receptors, general thinning of the olfactory epithelium, alterations in patterns or distribution of olfactory receptors, and patchy respiratory metaplasia, but these have not been thoroughly studied.3,17

This study had two purposes. The first was to determine if our mucus collection technique is specific to the olfactory cleft and a reliable method for isolating olfaction-specific proteins. OBP has been reported to be produced exclusively by olfactory epithelium, thus we compared levels of this protein between OC and IT mucus to confirm site specificity.18 Our second purpose was to investigate the presence of a broad array of proteins representative of potential mechanisms that could play a role in OD. This included growth factors, inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, and senescence-related proteins. Secondary aims of this study were to investigate whether there were any demographic factors, comorbidities or exposures which may also be associated with non-CRS related OD.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) (HR# E-607 R). Healthy subjects without the diagnosis of CRS were enrolled between January 2017 and February 2018. Study subjects were selected on a voluntary basis from university and local communities and from subjects who had previously participated in non-rhinologic research studies at MUSC. Exclusion criteria included those on immunosuppressive medications at the time of enrollment including systemic steroids/chemotherapy, history of autoimmune disorders, or a history of dementia, Alzheimer’s, or Parkinson’s disease. Patients who were currently taking blood thinning medications, have a history of adverse reaction to anesthetics/decongestants such as lidocaine and phenylephrine, respectively, or a history of vasovagal syncope were also excluded due to inability to perform endoscopy in these patients with minimal harm. Once enrolled, patients completed medical history questionnaires to collect demographic data such as age, gender, race, height and weight, as well as information on medical comorbidities and past exposures which may be associated with olfactory dysfunction.

Objective Olfactory Testing

Objective olfactory testing was performed using Sniffin’ Sticks (Burghardt, Wedel, Germany) following manufacturer protocols. Each subject was tested in a one-on-one environment by a trained clinical research coordinator masked to other clinical data. The testing evaluated odor threshold, odor discrimination and odor identification. The threshold test was performed using serial dilutions of n-butanol in a single series, triple-forced choice procedure. The discrimination test utilized groups of three pens with 2 containing the same odorant and 1 a different odorant, presented randomly to the subject with a forced choice procedure. The identification test was performed with 16 different odorants presented at suprathreshold intensity using multiple choice procedures. Threshold was scored from 1 to 16 and the discrimination and identification tests were scored from 0 to 16. The overall threshold discrimination identification (TDI) score was obtained by combining the three individual scores for a minimum score of 1 and a maximum score of 48, with higher scores representing better olfactory function.

Olfactory Cleft Mucus Collection and Analysis

Nasal endoscopy was performed on each study subject using rigid 3mm, 0 degree endoscopes (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) after application of topical lidocaine and phenylephrine to the nasal cavity via atomizer. With endoscopy, the nasal cavity and olfactory cleft were examined for evidence of sinonasal inflammation or obstructive pathology. Under direct visualization, a 1 cm by 2 cm Leukosorb filter paper (Pall Scientific, Port Washington, NY) strip was placed into the olfactory cleft of each side, and kept in place for three minutes, as described in previously published studies.12,19 The Leukosorb paper was then removed and placed into cuvettes that were immediately centrifuged at 4°C for 30 minutes. The mucus was then combined from each side, transferred by pipette to a cryotube, and stored at −80°C until performance of assays.

Odorant Binding Protein Analysis

To assess olfactory specificity and localization we measured odorant binding protein (OBP) which has been reported to be site specific.18 A group of 22 normosmic subjects were selected for paired analysis of OBP. For these subjects, Leukosorb strips were placed in each olfactory cleft as described above, as well as on the head of each inferior turbinate in order to compare levels of OBP between the two sites. Nasal mucus was prepared as described above. OBP concentration levels were assessed using standardized ELISA method following the kit instructions (LifeSpan Biosciences Inc, Seattle, WA). The large volume of mucus needed to conduct the OBP analysis limited our ability to also screen for immune mediators in this cohort.

Growth factor, cytokine and chemokine analysis

All proteins, except CDKN2A/p16 and OBP, were quantified by LegendPlex Mix & Match Cytometric Bead Array (San Diego, CA) following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol and read on a Guava easy Cyte 8HT flow cytometer (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA). Data analysis was performed with LegendPlex software provided by the manufacture. CDKN2A/p16 was quantified by ELISA following the kit instructions (LifeSpan Biosciences).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were performed for all study subjects, including demographics and comorbidities. For each olfactory cleft mucus protein analyzed, the descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, median, maximum and minimum were generated. The frequency with which each olfactory cleft mucus proteins was within detectable limits of the assay in the olfactory cleft mucus was recorded. For the purposes of analysis, samples with protein concentrations outside of the detectable limits, either too high or too low, were assigned the maximum and minimum values of detection set by the assay manufacturer, respectively. Association between the TDI score and concentration of olfactory cleft proteins was determined using Spearman rank-order correlations. Similarly, correlations among individual proteins were determined using spearman correlations. The OBP analysis between the olfactory cleft and inferior turbinate mucus samples was performed using the one-tailed paired samples T-test. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 56 subjects were enrolled into the study cohort, with demographics, comorbidities, exposures and olfactory testing results represented in Table 1. Thirty-four subjects were included in the olfactory cleft mucus protein analysis and 22 subjects (all normosmic) were included in the OBP analysis. The average age of the cohort was 47.8 years (SD 17.6 years), with the majority being female and Caucasian. Allergic rhinitis, former smoking status and respiratory exposures were commonly reported. Subjects represented the spectrum of olfactory dysfunction, with 42.9% (24/56 participants), having some degree of OD as defined by a TDI score cutoff below 30.5 for females and 29.5 for males.26 Correlations between baseline demographic factors, comorbidities and exposures with total TDI score were performed but none were found to be statistically significant (data not shown).

Table 1.

Demographics and comorbidities of study sample (n = 56)

| Mean (SD) | n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 47.8 (17.6) | ||

| Gender | Female | 33 (58.9%) | |

| Male | 23 (41.1%) | ||

| Race | Black | 11 (19.6%) | |

| Other | 5 (8.9%) | ||

| White | 40 (71.4%) | ||

| Diabetes | 5 (8.9%) | ||

| High Blood Pressure | 15 (26.8%) | ||

| Major Hospitalizations | 16 (28.6%) | ||

| Cancer | 4 (7.1%) | ||

| Asthma | 3 (5.4%) | ||

| Allergic Rhinitis | 18 (32.1%) | ||

| GERD | 7 (12.5%) | ||

| High Cholesterol | 13 (23.2%) | ||

| Depression | 5 (8.9%) | ||

| Anxiety | 5 (8.9%) | ||

| Apnea | 3 (5.4%) | ||

| Alcohol Status | Current Drinker | 38 (67.9%) | |

| Former Drinker | 3 (5.4%) | ||

| Never Drinker | 15 (26.8%) | ||

| Alcoholic Drinks/Week | 4.9 (13.0) | ||

| Smoking | Never smoker | 39 (69.6%) | |

| Former smoker | 14 (25.0%) | ||

| Current smoker | 3 (5.4%) | ||

| Military service | 6 (10.7%) | ||

| Any/several of the following exposures: chemical odors, exhaust fumes, pollution/smog, wood dust | 10 (17.9%) | ||

| BMI | 26.9 (5.2) | ||

| Olfactory function | |||

| Threshold | 6.6 (2.8) | ||

| Discrimination | 11.0 (2.3) | ||

| Identification | 12.6 (2.5) | ||

| TDI Total Score | 30.3 (6.4) | ||

In order to assess site specificity, OBP analysis was performed on a cohort of 22 normosmic study participants. The mean concentration (pg/mL) of OBP was significantly higher in the olfactory cleft than at the inferior turbinate, (148.2 ± 124.5 vs 105.4 ± 54.0; p =0.006), suggesting good localization of this method.

Table 2 presents the mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum concentrations of the eighteen olfactory cleft mucus proteins evaluated by the analysis, along with the frequency of olfactory mucus samples having detectable levels of the proteins of interest. Standard deviations of the protein levels were relatively large in general, indicating that there was variation between samples. Due to an error generating the standard curve for one set of EGF samples, only 22 patients had values for this analysis. Three patients lacked sufficient sample volumes to conduct the analysis for IL-1β, TNF-α, CCL2, CXCL5, CCL20, and CDKN2A/p16. Another three patients had only OBP ELISA performed due to insufficient sample volumes. Nine of the 17 proteins had detectable levels in 100% of the samples, with 14 detectable greater than 80% of the time. The three proteins detected with a frequency less than 80% were GM-CSF, M-CSF and SCF at 79.41%, 76.47% and 64.71%, respectively.

Table 2.

Olfactory cleft mucus proteins and descriptive statistics and frequency of detectable limits (Count, %). Protein concentrations in pg/mL unless otherwise noted.

| Cytokine | n | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Detectable n (%) | Above n (%) | Below n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGF | 22 | 853.0 | 703.1 | 658.3 | 188.3 | 3235.8 | 22/22 (100.0%) | - | - |

| bFGF | 34 | 266.8 | 307.2 | 120.2 | 19.1 | 1529.2 | 29/34 (85.3%) | - | 5/34 (14.7%) |

| G-CSF | 34 | 8838.0 | 8961.2 | 5437.2 | 195.8 | 35499.0 | 34/34 (100.0%) | - | - |

| GM-CSF | 34 | 21.6 | 14.0 | 14.7 | 4.1 | 62.6 | 27/34 (79.4%) | - | 7/34 (20.6%) |

| HGF | 34 | 4256.1 | 3884.2 | 2858.4 | 65.6 | 15508.1 | 33/34 (97.1%) | - | 1/34 (2.9%) |

| M-CSF | 34 | 78.8 | 89.3 | 62.5 | 3.4 | 366.6 | 26/34 (76.5%) | - | 8/34 (23.5%) |

| SCF | 34 | 79.7 | 118.5 | 29.9 | 2.7 | 546.1 | 22/34 (64.7%) | - | 12/34 (35.3%) |

| TGF-a | 34 | 392.2 | 221.6 | 404.0 | 38.4 | 860.0 | 34/34 (100.0%) | - | - |

| VEGF | 34 | 4640.1 | 2642.6 | 3963.1 | 1294.6 | 13953.4 | 34/34 (100.0%) | - | - |

| IL-1B | 31 | 420.3 | 721.0 | 164.2 | 24.0 | 3712.7 | 31/31 (100.0%) | - | - |

| TNF-a | 31 | 24.7 | 23.8 | 15.1 | 2.6 | 86.3 | 30/31 (96.8%) | - | 1/31 (3.2%) |

| CCL2 (MCP-1) | 31 | 693.9 | 735.3 | 407.2 | 123.6 | 3957.2 | 31/31 (100.0%) | - | - |

| IL-6 | 31 | 416.6 | 592.6 | 173.4 | 10.3 | 2531.7 | 31/31 (100.0%) | - | - |

| CXCL5 | 31 | 9149.4 | 7733.0 | 6900.8 | 130.3 | 23500.6 | 28/31 (90.3%) | 3/31 (9.7%) | - |

| CCL20 (MIP-3a) | 31 | 4169.6 | 6404.7 | 1306.3 | 70.2 | 24406.2 | 29/31 (93.5%) | 2/31 (6.5%) | - |

| CDKN2A/p16INK4a | 31 | 9124.5 | 8552.0 | 8023.0 | 45.2 | 26828.5 | 31/31 (100.0%) | - | - |

| OBP | 22 | 148.2 | 124.5 | 141.6 | 17.9 | 525.0 | 22/22 (100.0%) | - | - |

EGF=Epidermal growth factor; bFGF=Basic fibroblast growth factor; G-CSF= Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; GM-CSF = Granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factory; HGF = Hepatocyte growth factor; M-CSF = Macrophage colony-stimulating factor; SCF = Stem cell factor; TGF-a = Transforming growth factor-alpha; VEGF = Vascular endothelial growth factor; IL-1B = Interleukin 1B; TNF-a = Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; CCL2= Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; IL-6 = Interleukin 6; CXCL5 = C-X-C motif chemokine 5; CCL20 = Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20; CDKN2A/p16INK4a = Cyclin-dependent kinase Inhibitor 2A; OBP = Odorant binding protein 2A

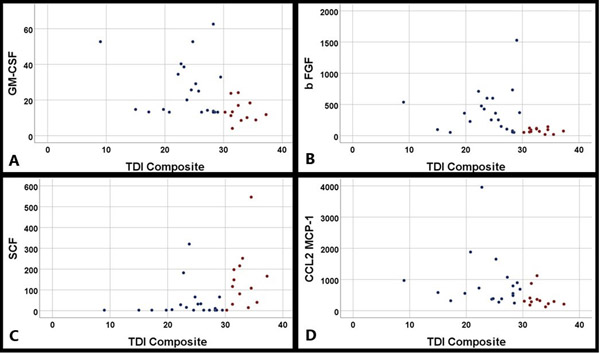

Spearman correlations of the eighteen olfactory cleft mucus proteins with the composite TDI score are shown in Table 3. Of the 18 olfactory cleft mucus proteins analyzed, 6 significantly correlated with the composite TDI score. Negative correlations were found for CDKN2A/p16INK4a, bFGF, CCL2/MCP-1, GM-CSF and CCL20/MIP-3a. A positive correlation was found for SCF with overall TDI. When dividing the subjects into hyposmic and normosomic groups, the average concentrations of these 6 significantly correlated proteins were found to be significantly different (Table 4).

Table 3.

Spearman correlations of cytokines with TDI.

| Cytokine | r s | p |

|---|---|---|

| CDKN2A/p16INK4a | −.591 | <.001 |

| bFGF | −.508 | .002 |

| CCL2 (MCP-1) | −.507 | .004 |

| GM-CSF | −.479 | .004 |

| CCL20 (MIP-3a) | −.479 | .006 |

| SCF | .510 | .002 |

| CXCL5 | −.286 | .119 |

| IL-6 | −.232 | .208 |

| EGF | −.146 | .517 |

| G-CSF | −.135 | .447 |

| IL-1B | −.113 | .546 |

| HGF | −.072 | .686 |

| TNF-a | −.061 | .745 |

| M-CSF | .259 | .140 |

| TGF-a | .231 | .189 |

| VEGF | .161 | .363 |

Table 4.

Comparison of average concentrations of significantly correlated proteins from spearman correlation between normosmic and hyposmic subjects

| TDI Categories | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normosmia | Hyposmia | ||

| CDKN2A/p16INK4a | 1791.3 (5293.2) | 13756.0 (6802.9) | <.001 |

| bFGF | 80.0 (38.1) | 382.4 (343.6) | .001 |

| CCL2 (MCP-1) | 393.0 (297.8) | 884.0 (865.1) | .006 |

| GM-CSF | 14.1 (6.0) | 26.2 (15.5) | .006 |

| CCL20 (MIP-3a) | 1021.6 (1136.5) | 6157.7 (7536.5) | .002 |

| SCF | 147.7 (143.7) | 37.6 (76.9) | .001 |

We then examined correlations of the 6 significant olfactory cleft mucus proteins with individual threshold, discrimination, and identification scores to determine if certain proteins were associated with different aspects of olfaction (Table 5). While several of the proteins appeared to impact all aspects of olfaction, there were some that appeared to impact threshold, discrimination, and identification differently. For example, GM-CSF, SCF and CCL2 affected all aspects of olfaction at significant or near significant levels. However, CCL20 had a moderate association with threshold, but it had no apparent association with discrimination or identification.

Table 5.

Spearman correlations of significant olfactory cleft mucus proteins with T, D, I individual scores.

| bFGF | GM-CSF | SCF | CCL2 (MCP-1) | CCL20 (MIP-3a) | CDKN2A/p 16INK4a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | r s | −.353 | −.313 | .304 | −.436 | −.425 | −.460 |

| p | .041 | .071 | .081 | .014 | .017 | .009 | |

| Discrimination | r s | −.473 | −.432 | .540 | −.319 | −.199 | −.609 |

| p | .005 | .011 | .001 | .081 | .284 | <.001 | |

| Identification | r s | −.282 | −.408 | .364 | −.380 | −.296 | −.164 |

| p | .106 | .017 | .034 | .035 | .106 | .377 | |

Discussion

OD is a common condition that has significant morbidity to those who live with this condition. Unlike CRS-related OD which has established treatments and reasonable outcomes, most non-CRS related OD lacks highly effective treatment options. Topical and systemic corticosteroids are commonly employed in treatment of olfactory loss. In a systematic review looking specifically at non-CRS related OD, Yan et al. found that there was limited evidence for the efficacy of systemic corticosteroids with two retrospective reviews showing clinically significant improvement in only 27% of patients, and one randomized-controlled trial evaluating twice daily budesonide rinses showing improvement in 43.9% of patients.20–23 Since the introduction of olfactory training protocols by Hummel in 2009, olfactory training has become an option for treatment in patients with OD.24 It has shown efficacy in treating olfactory loss in patients with OD related to neurodegenerative, post-traumatic and post-viral etiologies, though it has only improved olfaction in approximately 30–50% of patients.25 The variable results from these treatment options are likely reflective of the heterogeneous etiologies of non-CRS related OD.

In order to develop highly efficacious future therapies, there must be an understanding of the underlying mechanisms behind the pathogenesis of OD. Assessing the local microenvironment of the olfactory neuroepithelium will be critical to developing this mechanistic understanding. A variety of methods have been previously utilized in previous studies to assess the olfactory epithelial environment, including biopsies with histopathologic study, and collection of olfactory mucus using methods such as lavage and aspiration.12–13,17,26–28 Unfortunately, these methods suffer from sampling error and the potential to include samples from non-olfactory cleft sites via spill over from adjacent sites. The study of olfactory cleft mucus collected via placement of absorbable sponges or paper in the olfactory cleft has gained popularity in the CRS realm and has provided insights into the various inflammatory mechanisms.12–13 In order to ascertain the specificity of our method to the olfactory epithelium, we compared the levels of OBP between the olfactory cleft and inferior turbinate mucus samples. OBPs are small soluble proteins of the lipocalin family which are produced at high levels in the olfactory epithelium by Bowman’s glands and are thought to be involved in aiding the dissolution of hydrophobic odorants into the mucus aqueous layer to reach the receptor binding sites.18,29 OBPs were previously reported to be specific to the olfactory epithelium.18 We found higher concentrations of OBP in the olfactory cleft mucus as compared to the inferior turbinate mucus (p = 0.006). It is unclear if the presence of OBP in inferior turbinate mucus reflects olfactory mucus that has drained inferiorly or if OBP production also occurs at non-olfactory sites. Regardless, our finding suggests that the mucus collected via the Leukosorb filter paper placement into the olfactory cleft is relatively specific to the olfactory epithelium and thus, a valid method to evaluate the microenvironment surrounding the olfactory interface.

Previous reports of olfactory mucus protein analysis in non-CRS adults have been quite limited and it is likely secondary to the fact that the etiology of OD in these subjects is heterogeneous. Given that such etiologies could include viral, traumatic, allergic, smoke exposure, other environmental exposure, neurodegenerative disease and idiopathic causes, we selected a broad spectrum of proteins to measure fibrosis, inflammation, growth factors and senescence. It is important to note that the main focus of this investigation was to determine if collection of these mediators was feasible and if there were any associations with olfaction highlighting areas of future study. The design of this study makes it difficult draw any conclusions regarding causation. Moreover, since the protein assays were performed in a cross-sectional manner, it is impossible to determine whether the elevated levels of these proteins are preceding olfactory loss or if these proteins are elevated as a response to olfactory loss in an attempt to heal injured olfactory epithelium after insult.

Utilizing this strategy, this study found significant correlations with a variety of proteins from different functional groups. In the growth factor group, bFGF was found to be inversely correlated with olfactory function. This protein functions in wound healing, stimulating fibroblast proliferation and has also been found to promote neural regeneration, prevent death of injured neurons and promote proliferation of stem cells in vitro. 30–31 For the cytokines and chemokines, GM-CSF, CCL2, and CCL20 were significantly inversely correlated with olfactory function, whereas SCF were positively correlated with olfaction. The specific interactions in which these proteins affect olfactory function are not clear and will require further investigation. It is interesting that some cytokines included in our panel which were previously correlated with olfaction in CRS patients, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), TNFα and interleukin-6 (IL-6), were not correlated in this study.12,32–33 The differences in the cytokine profiles between CRS and non-CRS mucus samples point to the likelihood that the development of hyposmia mediated by inflammatory factors in CRS versus non-CRS patients occurs through distinct mechanisms and will ultimately require distinct treatment strategies. Additionally, the senescence protein CDKN2A/p16INK4a, or the p16 protein, a cell cycle mediator which functions in preventing transition from the G1 phase to the S phase of the cell cycle, was negatively correlated with olfactory function. Continual renewal and turnover is necessary for optimal olfactory function and impairment of this function may be related to the elevated p16 levels. CDKN2A/p16INK4a was also significantly correlated with every other significant protein in our analysis, which may indicate that senescence may represent a broad, non-specific factor that plays a role in several types of non-CRS OD.

When performing subscale analysis of the TDI scores, most proteins were found to correlate with a number of different aspects of the objective olfactory test and may indicate non-specific effects. CCL20 appeared to be one exception with relative isolated effects upon threshold and no discernible impact upon discrimination or identification. Decreases in odor threshold are most often considered a result of nasal cavity dysfunction with functional olfactory neuroepithelium, as patients can discriminate and identify odors when given suprathreshold stimuli. It may be that CCL20 is associated with inflammatory etiologies, such as allergies, smoking or inhaled toxins which preferentially impact respiratory epithelium with less impact upon the olfactory neuroepithelium. On the other hand, decline in discrimination and identification abilities may represent dysfunction of olfactory neuroepithelium or central olfactory processing.3,11 The influence of these proteins upon the various aspects of olfaction likely overlap, and parsing out these interactions will require further study.

A unique aspect of this study is the method of patient recruitment. Most olfaction studies tend to categorize patients by clinically assessed etiologies of smell loss (such as traumatic, post-viral, inflammatory, etc.), recruited from clinics which specialize in treating olfactory dysfunction. Our study, on the contrary, recruited subjects from the healthy population irrespective of perceived olfactory functional status. In fact, many of our study participants had no knowledge that they were hyposmic until after objective olfactory testing was performed as part of the study protocol. Due to this, most of our patients would likely fall under the “idiopathic” category of olfactory loss. This may have been an advantageous study design as it removes bias and allows for recruitment of a study population which is a truly heterogeneous group.

The main limitation of this pilot study is the small sample size and cross-sectional design which limits the conclusions that can be drawn from the results. The goal of this investigation was to find associations and provide preliminary data, and thus, these findings should be considered groundwork for future inquiry. The fact that significant associations were seen across a number of cytokines suggests that larger, confirmatory studies would be indicated and likely to be fruitful. Additionally, the results of the OBP analysis were able to show that collection of olfactory mucus from the olfactory cleft is relatively specific to the olfactory epithelium and this technique shows promise for areas of future study. The technique of analyzing olfactory mucus proteins may be an avenue for prognostication or allow for identification of therapeutic targets for patients with idiopathic olfactory dysfunction.

Conclusions

In this study, we were able to show though the OBP paired analysis, that mucus collection via leukosorb sponges in the olfactory cleft is relatively site-specific for the protein milieu surrounding the olfactory neuroepithelium. This allowed us to find correlations between 6 different olfactory cleft mucus proteins and objective olfactory function. These proteins are likely associated with a broad number of potential mechanisms, including wound healing, neural regeneration, inflammation, fibrosis, and senescence that vary from patient to patient. With subscale analysis, these proteins were differentially correlated with the individual threshold, discrimination and identification scores, indicating there may be both peripheral respiratory and olfactory epithelium specific processes involved in the development of non-CRS OD. Further inquiries are required replicate these findings and then elucidate the role these proteins play in the pathogenesis of olfactory loss.

Figure 1.

Scatterplots of correlations between olfactory cleft protein concentrations (A) GM-CSF, B) bFGF, C) SCF and D) CCL2) and total TDI score. (Red = normosmic, Blue = hyposmic)

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research (SCTR) Institute, with an academic home at the Medical University of South Carolina CTSA, NIH/NCATS Grant Number KL2TR001452 & UL1TR001450. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NCATS.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest/Disclosures: ZMS is a consultant for Optinose, Olympus and Healthy Humming, LLC and on the advisory board for Regeneron and Novartis. RJS is a consultant for Olympus, Sanofi, Optinose, Healthy Humming, LLC, and Stryker. RJS and ZMS have received grant support from Entellus, Optinose, Intersect, GSK, Astra Zeneca, Roche and Sanofi.

References

- 1.Landis BN, Konnerth CG, and Hummel T. A Study on the Frequency of Olfactory Dysfunction. Laryngoscope 2004;114:1764–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attems J, Walker L, and Jellinger KA. Olfaction and Aging: A Mini-Review. Gerentolog 2015;51:485–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doty RL and Kamath V. The influences of age on olfaction: a review. Front Psychol 2014;5:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kershaw JC and Mattes RD. Nutrition and taste and smell dysfunction. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018;4(1):3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattes RD and Cowart BJ. Dietary assessment of patients with chemosensory disorders. J Am Diet Assoc 1994;94(1):50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doty RL. Age-related deficits in taste and smell. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 2018;51:815–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deems DA, Doty RL, Settle RG, et al. Smell and taste disorders, a study of 750 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Smell and Taste Center. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;117:519–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pence TS, Reiter ER, DiNardo LJ, et al. Risk factors for hazardous events in olfactory-impaired patients. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:951–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto JM Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, et al. Olfactory dysfunction predicts 5-year mortality in older adults. PLoS One 2014;9:e107541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubert CR, Fischer ME, Pinto AA, et al. Sensory Impairments and Risk of Mortality in Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017;75(5):710–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marin C, Vilas D, Langdon C, et al. Olfactory dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Disease. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018;18(8):42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlosser RJ, Mulligan JK, Hyer JM, et al. Mucous Cytokine Levels in Chronic Rhinosinusitis-Associated Olfactory Loss. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;142(8):731–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J, Chandra RK, Li P, et al. Olfactory and middle meatal cytokine levels correlate with olfactory function in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 2018;128(9):E304–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavin J, Min JY, Lidder A, et al. Superior turbinate eosinophilia correlates with olfactory deficit in chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Laryngoscope 2017;127(10):2210–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauser LJ, Chandra RK, Ping L, et al. Role of tissue eosinophils in chronic rhinosinusitis-associated olfactory loss. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2017;7(10:957–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soler ZM, Sauer DA, Mace J, and Smith TL. Relationship between clinical measures and histopathological findings in chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;141(4):454–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holbrook EH, Wu E, Curry WT, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of human olfactory tissue. Laryngoscope 2011;121(8):1687–1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briand L, Eloit C, Nespoulous C, et al. Evidence of Odorant-Binding Protein in the Human Olfactory Mucus: Location, Structural Characterization, and Odorant-Binding Properties. Biochemistry 2002;41:7241–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rebuli ME, Speen AM, Clapp PW, et al. Novel applicatiosn for noninvasive sampling method of the nasal mucosa. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2017;312(2):L288–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan CH, Overdevest JB, and Patel ZM. Therapeutic use of steroids in non-chronic rhinosinusitis olfactory dysfunction: a systematic evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2018;00:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stenner M, Vent J, Huttenbrink KB, et al. Topical therapy in anosmia: relevance of steroid-responsiveness. Laryngoscope 2008;118:1681–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schriever VA, Merkonidis C, Gupta N, et al. Treatment of smell loss with systemic methylprednisolone. Rhinology 2012;50:284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen TP and Patel ZM. Budesonide irrigation with olfactory training improves outcomes compared with olfactory training alone in patients with olfactory loss. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2018;8:997–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hummel T, Rissom K, Reden J, et al. Effects of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss. Laryngoscope 2009;119:496–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel ZM. The evidence for olfactory training in treating patients with olfactory loss. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;25:43–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soler ZM, Hyer JM, Karnezis TT, et al. The olfactory cleft endoscopy scale correlates with olfactory metrics in patients with chronic sinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2016;6(3):293–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vandehende-Szymanski C, Hochet B, Chevelier D, et al. Olfactory cleft opacity and CT score are predictive factors of smell recovery in surgery in nasal polyposis. Rhinology 2015;53(1):29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Debat H, Eloit C, Blon F, et al. Identification of human olfactory cleft mucus proteins using proteomic analysis. J Proteome Res 2007;6(5):1985–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zarzo M The sense of smell: molecular basis of odorant recognition. Biol Rev 2007;82:455–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nota J, Takahashi H, Hakuba N, et al. Treatment of neural anosmia by topical application of basic fibroblast growth factor-gelatin hydrogel in the nasal cavity: An experimental study in mice. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;139(4):396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukuda Y, Katsunuma S, Uranagase A, et al. Effect of intranasal administration of neurotrophic factors on regeneration of chemically degenerated olfactory epithelium in aging mice. Neuro Report 2018:29(16):1400–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia DS, Chen M, Smith AK, et al. Role of type 1 tumor necrosis factor receptor in inflammation-associated olfactory dysfunction. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2017;7(2):160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sultan B, May LA, and Lane AP. The role of TNF-α in inflammatory olfactory loss. Laryngoscope 2011;121(11):2481–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]