Abstract

Objective

This study aims to assess the relationship between Food and Nutrition Literacy (FNLIT) and dietary diversity score (DDS); FNLIT and nutrient adequacy (NAR%, MAR%) in school-age children in Iran.

Results

This cross-sectional study was undertaken on 803 primary school students in Tehran, Iran. Socio-economic, as well as three 24-h dietary recalls were collected through interviewing students and their mothers/caregivers. FNLIT was measured by a self-administered locally designed and validated questionnaire. Low level of FFNL was significantly associated with higher odds of low DDS (OR = 2.19, 95% CI 1.32–3.62), the first tertile of fruit diversity score (OR = 3.88, 95% CI 2.14–6.99), and the first tertile of dairy diversity score (OR = 9.60, 95% CI 2.07–44.58). Low level of IFNL was significantly associated with probability of lower meat diversity score (OR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.07–2.81). Low level of FLL was also significantly associated with probability of lower DDS (OR = 1.81, 95% CI 1.11–2.94), dairy diversity score (OR = 2.01, 95% CI 1.02–3.98), and meat diversity score (OR = 2.14, 95% CI 1.32–3.45).Low FNLIT and its subscales were associated with higher odds of low level of NAR of protein, calcium, vitamin B3, B6, B9, as well as the probability of lower level of MAR.

Keywords: Food and Nutrition Literacy, Dietary diversity, Nutrient adequacy, School age children, Iran

Introduction

Prevalence of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) is a public health problem in Iran [1]. Therefore, an important priority for the health sector is capacity building within the public to prevent NCDs by empowering people to take control of the determinants of their health and disease [2]. Health literacy is considered as one of the most important skills to enable individuals to control health determinants [3]. Due to wide scope of health issues and because of the growing prevalence of diet-related chronic diseases [4], evidence suggest that one should consider health literacy more specifically [5]. As a result, food literacy/nutrition literacy has been proposed and conceptualized.

Studies have found that food literacy/nutrition literacy can have a critical role in shaping children’s dietary behaviors [6] and enabling them to have healthy food choices [7, 8]. In Iran, nutrition transition has taken place due to urbanization and rapid socio-economic changes and have resulted in a tendency toward a more westernized dietary pattern, especially among children and adolescents [9]. This general shift in children’s diet is characterized as low consumption of fruit and vegetables, fiber-rich foods and dairy products [10], as well as high consumption of fatty, sugary and convenience foods [11].

Considering today’s children food environment, improving food and nutrition literacy provides an opportunity for them to acquire appropriate skills and act more consciously [12]. Identifying the relation between food and nutrition literacy and children dietary intake is important for the development of effective prevention and management strategies in these age groups [6]. Yet, there is a gap of published evidence in this area. Therefore, This study aims to assess the relationship between Food and Nutrition Literacy (FNLIT) and dietary diversity score (DDS); as well as FNLIT and nutrient adequacy (NAR%, MAR%) in school-age children in Tehran, Iran.

Main text

Methods

Study design and setting

This school-based cross-sectional survey was performed using a multistage random cluster sampling design. The study was conducted in Tehran the capital city of Iran from November to January 2016. The STROBE (Strengthening The Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) study conduct [13] and participant flow is outlined in (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Study participants

The sample included 803 primary school students (419 boys and 384 girls) aged 10–12 years (power study 88%; response rate = 89.2%) from different socio-economic districts. Selected students and their parents were invited to take part in the study after signing a consent letter.

Data collection

Food and nutrition literacy assessments

Food and nutrition literacy (FNLIT) was measured by a valid self-administered questionnaire [14]. The questionnaire consisted of 4 true–false and 42 likert-type items within two cognitive and skill domains. Cognitive domain included two sub-scales: understanding food and nutrition information (UFNI, 10 items) and nutritional health knowledge (NHK, 5 items). Skill domain consisted of four sub-scales: functional food and nutrition literacy (FFNL, 10 items), interactive food and nutrition literacy (IFNL, 7 items), food choice literacy (FCL, 6 items) and critical food and nutrition literacy (CFNL, 4 items). Finally, Food label literacy (FLL) was evaluated by 4 true–false items. According to ROC analysis, three levels for FNLIT was low (≤ 51), medium (> 51– < 74) and high (≥ 74), where the FNLIT score ranged from 25.8 to 96.8 [15]. The questionnaire was completed by students.

Dietary intake assessments

Three 24-h dietary recalls (2 week-days and one holiday) was collected by interviewing the students and their mothers and/or other caregivers. To identify misreporting, BMR (basal metabolic rate) was estimated by using the equations published by Schofield (16). An individual’s daily food intake was considered under-reported, if EI (energy intake) to BMR ratio (EI/BMR) was less than 1.14, or over-reported if it was higher than 2.5 (17). Over- and under-reporters were excluded from the study as ‘misreporters’. After data cleaning and excluding all outliers and diet recall misreporters (170 students), 493 students remained for statistical analysis (see Additional file 1: Fig.S1). The characteristics of subjects excluded did not differ significantly from those remained in the study. Dietary intake adequacy-The nutrient adequacy ratio (NAR%)- was calculated for energy and 11 nutrients. NAR was calculated as the intake of a nutrient divided by the recommended intake for that nutrient (RNI) [16]. Mean adequacy ratio (MAR %) was calculated as a measure of the adequacy of overall diet, where MAR is the sum of each NAR (truncated at 100%) divided by the number of nutrients (excluding energy and protein) [17].

Dietary Diversity Score (DDS)–DDS was calculated as part of the pyramid serving database that was categorized into 23 broad food groups. Each of the 5 broad food categories received a maximum diversity score of 2 of the 10 possible score points. To be counted as a “consumer” for any of the food groups categories, a respondent needed to consume at least one-third serving at any time during a 3-day survey period [18].

Covariates

A number of evidence-based covariates [19–22] were considered in the study. Anthropometric measurements were taken [23]. BMI-Z-score for age and sex was calculated by WHO AnthroPlus, 2007 [24]. Physical activity was measured through interviewing children by the locally validated version of Child and Adolescent International physical activity questionnaires [25, 26]. Household food security status was measured using a locally validated 18-item USDA’s Household Food Security Survey Module through face-to-face interview with mothers [27, 28]. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics were collected by a questionnaire through interviewing with students and verified by their mothers and/or caregivers thereafter.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Chi square test was used for analysis of general characteristics of participants. Independent sample t test was used to evaluate the differences between continuous variable between two sexes. Multinomial logistic regression analysis adjusting for confounding factors of the lower two tertiles compared with the higher tertile of MAR, NAR and DDS was conducted. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, US).

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

Table 1, summarizes background characteristics of the studied children by FNLIT status.

Table 1.

General characteristics of 10–12 years old students by FNLIT (Food and Nutrition Literacy) status in Tehran

| Demographic characteristics | Total | Low FNLIT ≤ 51 | Moderate/high FNLIT > 51 | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Sex | 800 | 0.46 | ||

| Male | 419 (52.4) | 52 (55.9) | 367 (51.9) | |

| Female | 381 (47.6) | 41 (44.1) | 340 (48.1) | |

| Grade | 800 | 0.26 | ||

| Fifth | 413 (51.6) | 43 (46.2) | 370 (52.3) | |

| Sixth | 387 (48.4) | 50 (53.8) | 337 (47.7) | |

| Birth order | 798 | 0.15 | ||

| < 2 | 437 (54.8) | 44 (47.8) | 393 (55.7) | |

| ≥ 2 | 361 (45.2) | 48 (52.2) | 313 (44.3) | |

| Father age tertile (year): | 790 | 0.47 | ||

| T1:30–40 | 300 (38.0) | 38 (42.7) | 262 (37.4) | |

| T2:41–45 | 265 (33.5) | 25 (28.1) | 240 (34.2) | |

| T3: ≤ 46 | 225 (28.5) | 26 (29.2) | 199 (28.4) | |

| Mother age tertile (year): | 794 | 0.20 | ||

| T1:23–35 | 288 (36.3) | 34 (37.0) | 254 (36.2) | |

| T2:36–40 | 303 (38.2) | 41 (44.6) | 262 (37.3) | |

| T3: ≥ 41 | 203 (25.6) | 17 (18.5) | 186 (26.5) | |

| Ethnicity | 797 | 0.99 | ||

| Fars | 441 (55.3) | 50 (54.3) | 391 (55.5) | |

| Azeri | 228 (28.6) | 27 (29.3) | 201 (28.5) | |

| Fars-Azeri | 56 (7.0) | 7 (7.6) | 49 (7.0) | |

| Other | 72 (9.0) | 8 (8.7) | 64 (9.1) | |

| School type | 800 | 0.78 | ||

| Public | 725 (90.6) | 85 (91.4) | 640 (90.5) | |

| Private | 75 (9.4) | 8 (8.6) | 67 (9.5) | |

| Family size | 797 | 0.140 | ||

| ≤ 3 | 160 (20.1) | 15 (16.3) | 145 (20.6) | |

| 4 | 465 (58.3) | 50 (54.3) | 415 (58.9) | |

| ≥ 5 | 172 (21.6) | 27 (29.3) | 145 (20.6) | |

| Fa ther education | 789 | 0.45 | ||

| Illiterate to ≤ 5 years | 85 (10.8) | 12 (13.5) | 73 (10.4) | |

| 6–9 years up to diploma | 395 (50.1) | 47 (52.8) | 384 (49.7) | |

| Associate’s degree or higher | 309 (39.2) | 30 (33.7) | 279 (39.9) | |

| Mother education | 794 | 0.001* | ||

| Illiterate up to ≤ 5 years | 86 (10.8) | 13 (14.1) | 73 (10.4) | |

| 6–9 years up to diploma | 461 (58.1) | 66 (71.7) | 395 (56.3) | |

| Associate’s degree or higher | 247 (31.1) | 13 (14.1) | 234 (33.3) | |

| Father job position | 690 | 0.11 | ||

| Worker | 106 (13.6) | 18 (20.5) | 88 (12.8) | |

| Employee/clerk | 327 (41.4) | 36 (40.9) | 291 (42.2) | |

| High rank employee | 139 (17.9) | 10 (11.4) | 129 (18.7) | |

| Retired | 20 (2.6) | 4 (4.5) | 16 (2.3) | |

| Self-manager | 186 (23.9) | 20 (22.7) | 166 (24.1) | |

| Mother employment | 794 | 0.58 | ||

| Working | 630 (79.3) | 75 (81.5) | 55 (79.1) | |

| Housewife | 164 (20.7) | 17 (18.5) | 147 (20.9) | |

| Other income source of family members | 799 | 0.98 | ||

| No | 752 (94.1) | 84 (90.3) | 668 (94.6) | |

| Yes | 47 (5.9) | 9 (9.7) | 38 (5.4) | |

| House ownership status | 799 | 0.55 | ||

| Owner | 427 (53.4) | 49 (52.7) | 378 (53.5) | |

| Tenant | 262 (32.8) | 32 (34.4) | 230 (32.6) | |

| Mortgage | 35 (4.4) | 6 (6.5) | 29 (4.1) | |

| Other | 75 (9.4) | 6 (6.5) | 69 (9.8) | |

| Financial support source | 799 | 0.94 | ||

| No | 781 (97.7) | 91 (97.8) | 690 (97.7) | |

| Yes | 18 (2.3) | 2 (2.2) | 16 (2.3) | |

| Physical activity tertile (MET.h/day) | 787 | 0.31 | ||

| Mean T1: 33 | 260 (33.0) | 36 (39.1) | 224 (32.2) | |

| Mean T2: 38.37 | 262 (33.3) | 25 (27.2) | 237 (34.1) | |

| Mean T3: 47.71 | 265 (33.7) | 31 (33.7) | 234 (33.7) | |

| Z score for BMI | 800 | 0.16 | ||

| Thinness | 15 (1.9) | 4 (4.3) | 11 (1.6) | |

| Normal | 381 (47.6) | 47 (50.5) | 334 (47.2) | |

| Overweight | 213 (26.6) | 19 (20.4) | 194 (27.4) | |

| Obese | 191 (23.9) | 23 (24.7) | 168 (23.8) | |

| HH food security status | 746 | 0.33 | ||

| FS | 560 (75.1) | 59 (68.6) | 501 (75.9) | |

| FI without hunger | 131 (17.6) | 19 (22.1) | 112 (17.0) | |

| FI with hunger | 55 (7.4) | 8 (9.3) | 47(7.1) |

HH household, FS food secure, FI food insecure

*Significant at p < 0.05 for x2 tests

Food and nutrition literacy (FNLIT)

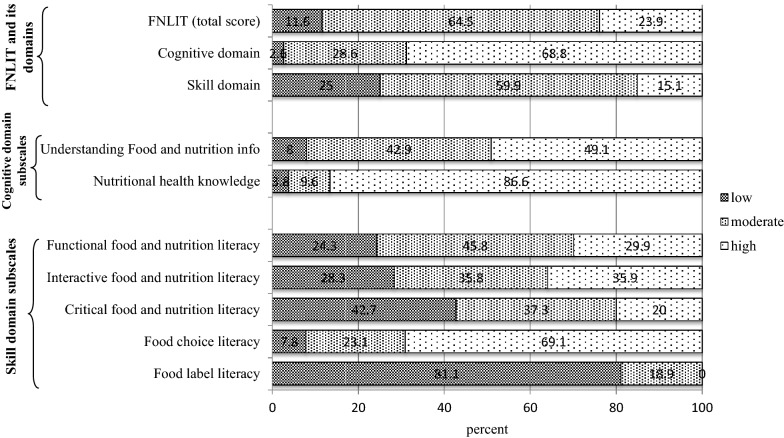

FNLIT status of the participants is presented in Fig. 1. Almost 25% of students had low scores in FNLIT skill domain, while the majority scored moderate to high in cognitive domain (97.4%). Among subscales of FNLIT skill domain, high proportion of students had low scores in CFNL (42.7%) as well as food label literacy (81.1%). However, they scored better in FCL and only 7.8% scored low.

Fig. 1.

Food and nutrition literacy status in 10–12 years old students in Tehran

Dietary intake adequacy

MAR and NAR of certain nutrients by sex are presented in (Additional file 2: Fig.S2). The multinomial-adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) of the lower two tertiles compared with the highest tertile of MAR and NAR of certain nutrients are presented in (Additional file 3: Table S1). Low levels of FNLIT was significantly associated with odds of lower level of NAR of protein (OR = 2.02, 95% CI 1.02–8.95). Low level of UFNI significantly increased the probability of having lower level of MAR and NAR of vitamin B9 (OR = 2.91, 95% CI 1.03–8.23, OR = 2.98, 95% CI 1.04–8.51 respectively). Low level of FFNL was significantly associated with odds of lower levels of MAR and NAR of vitamin B6 (OR = 3.12, 95% CI 1.38–7.05, OR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.10–4.83, respectively) and with odds of lower two tertiles compared with higher tertile of NAR of calcium (OR = 2.98, 95% CI 1.46–6.11, OR = 2.34, 95% CI 1.16–4.76 respectively). Low level of FCL was significantly associated with probability of lower level of NAR of vitamin B3 (OR = 3.65, 95% CI 1.05–12.69) and low level of FLL was significantly associated with probability of lower level of NAR of calcium (OR = 2.28, 95% CI 1.16–4.49).

Dietary diversity

Unadjusted and adjusted multinomial logistic regression of the lower two tertiles compared with the higher tertile of DDS are presented in Table 2. Adjusting for mother education, slightly improved the odds of certain DDS groups, including DDS, fruit diversity score and dairy diversity score for FFNL, and protein foods diversity score for IFNL.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odd Ratios (95% CI) of Dietary Diversity Score (DDS) for FNLIT scale and its subscales in 10–12 years students in Tehran (n = 493)

| Dietary diversity score (DDS) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | DDS | Fruits | Dairies | Protein foods | ||||||||||||

| Models | Unadjusted relative risk ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted relative risk ratio (95% CI) | Unadjusted relative risk ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted relative risk ratio(95% CI) | Unadjusted relative risk ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted relative risk ratio (95% CI) | Unadjusted relative risk ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted relative risk ratio (95% CI) | ||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | |

| Low FFNL | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.19* (1.32, 3.62) | 0.85 (0.48, 1.52) | 2.25* (1.35, 3.76) | 0.88 (0.49, 1.56) | 3.88* (2.14, 6.99) | 1.68*(1.06, 2.67) | 3.90* (2.17, 7.00) | 1.72*(1.08, 2.74) | 9.60*(2.07, 44.58) | 6.88*(1.45, 32.65) | 9.80*(2.08, 46.11) | 7.13*(1.48, 34.26) | 0.98 (0.55, 1.74) | 0.98 (0.58, 1.64) | 0.98 (0.55, 1.74) | 0.98 (0.58, 1.64) |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Low IFNL | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 0.96 (0.61, 1.52) | 0.94 (0.58, 1.52) | 0.98 (0.62, 1.54) | 0.94 (0.58, 1.52) | 0.83 (0.47, 1.49) | 0.97 (0.65, 1.46) | 0.83 (0.46, 1.49) | 0.98 (0.65, 1.48) | 1.05 (0.47, 2.33) | 1.02 (0.44, 2.33) | 1.06 (0.47, 2.36) | 1.02 (0.44, 2.35) | 0.91 (0.52, 1.58) | 1.73*(1.07, 2.81) | 0.92 (0.53, 1.59) | 1.75*(1.08, 2.84) |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Low FLL | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.81*(1.11, 2.94) | 1.32 (0.81, 2.15) | 1.71*(1.05, 2.79) | 1.33 (0.81, 2.16) | 1.07 (0.58, 1.99) | 1.39 (0.90, 2.15) | 1.06 (0.57, 2.05) | 1.32 (0.85, 2.37) | 2.01*(1.02, 3.98) | 2.16*(1.03, 4.50) | 1.98 (0.81, 4.86) | 2.05*(1.01, 4.36) | 1.64 (0.97, 2.76) | 2.14*(1.32, 3.45) | 1.61 (0.95, 2.73) | 2.06*(1.27, 3.34) |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

Multinomial logistic regression, adjusted for mother education

Only those variables that were significantly associated with FNLIT and its subscales were reported

FNLIT Food and Nutrition Literacy, Cognitive subscales including: UFNI Understanding Food and Nutrition Literacy, NHK Nutritional Health Knowledge, Skill subscales including, FFNL, Functional Food and Nutrition Literacy, IFNL Interactive Food and Nutrition Literacy, FCL Food Choice Literacy, CFNL Critical Food and Nutrition Literacy, FLL Food Label Literacy

*Significant at p < 0.05

Discussion

The present study showed that low food and nutrition literacy may be a barrier to dietary diversity and nutrient adequacy in school age children. Previous research has shown that high food literacy is associated with increased consumption of fruits and vegetables [29, 30]. Children and adolescents who assisted in preparing meals were more likely to engage in food preparation-related behaviors such as buying fresh vegetables, writing grocery lists and preparing meals with chicken, fish or vegetables [31]. Besides, FNLIT skills encompass the ability to obtain factual dietary information and develop an understanding of factors that can enhance or inhibit nutritional health [5] and may promote diet diversity and nutrient adequacy through improving understanding of available food and nutrition information and adherence to the dietary guidelines [5]. Low level of FNLIT was significantly associated with probability of lower level of meat group diversity (as major sources of protein and iron) and NAR of calcium, the two major limiting nutrients in the Iranian’s diet [32].

FLL was one of the weakest areas among the studied children. However, the question is to what degree food labeling is an appropriate approach and what type of information and labeling approaches can be helpful for children. Previous reports have identified food label reading as one of the key areas to improve food choices and dietary intakes in children [33]. In Iran, mandatory nutrition labeling for food products has recently been initiated while there are still gaps in its regulatory policy [34]. Besides, this concept and its application has not been entered in public education programs, including schools curricula and textbooks to empower individuals in making healthy food choices [35]. This may explain low scores observed in the study population with regard to questions on food labels.

The considerable proportions of students with low food and nutrition literacy in skill domain imply a gap in food and nutrition skill development in primary school curriculums in the country. This is not a surprise as based on content analysis of primary school textbooks in Iran, nutritional content of school textbooks were mainly theoretical and impractical [35]. This leads to many students with high food and nutrition knowledge, but limited skills in their dietary practices. Even though, nutrition knowledge has been identified as essential for behavior change [36], knowledge alone is generally not sufficient to produce sustained behavior change in complex behaviors [36]. Therefore, FNLIT subscale-based interventions should be designed to improve students’ skills and nutrition behaviors. For example, the results provide a reminder of the need to support improvements in food choices and dietary behaviors by helping young people to develop skills such as those required to interpret food labeling.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that low level of FNLIT is associated with nutritional inadequacy in school-age childeren and low DDS and may play an important role in shaping their dietary intake. FNLIT is expected to have effect on one’s ability to assess information when choosing foods, comprehend food labels, and apply dietary recommendations. Therefore, it is important for educators and program planners to assess and enhance FNLIT of young people. Stakeholders, including policy makers, food manufacturers, health providers, educators, and businesses should also play their roles so as to achieve a bigger impact on future generation.

Limitation

The current study has several limitations.

First, there was a possibility of recall bias and social desirability bias.

Second, due to its cross-sectional design, our study was not able to establish any cause-effect relationship of food and nutrition literacy on children’s dietary intakes.

Third, the excluded data was quite large, due to lack of access to parents by phone, although we found no significant difference in characteristics of dropout subjects with those remained in the study.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. STROBE study conduct and participant flow of the study.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2. The nutrient adequacy ratio percent of certain nutrients by sex in 10–12 years students in Tehran (n = 493).

Additional file 3: Table S1. Adjusted Odd Ratios (95% CI) of nutrient adequacy ratio (MAR%/NAR%) of certain nutrients for FNLIT scale and its subscales in 10–12 years students in Tehran (n = 493).

Acknowledgements

The authors hereby express their appreciation to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute (NNFTRI) for funding the study. All coordinators, interviewers, and students who participated in this study are appreciated.

Abbreviations

- FNLIT

Food and nutrition literacy

- NCDs

Non-communicable diseases

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- HEI

Healthy eating index

- BMR

Basal metabolic rate

- NAR

Nutrient adequacy ratio

- RNI

Recommended intake for that nutrient

- MAR

Mean adequacy ratio

- DDS

Dietary diversity score

- BMI

Body mass index

- METs-h/day

Metabolic equivalents hour/day

- UFNI

Understanding Food and Nutrition Information

- NHK

Nutritional health knowledge

- FFNL

Functional food and nutrition literacy

- IFNL

Interactive food and nutrition literacy

- FCL

Food choice literacy

- CFNL

Critical food and nutrition literacy

- FLL

Food label literacy

Authors’ contributions

AD was responsible for analysing and interpreting the data, drafting and editing the article. NO, NKM, HE-Z carried out the study design and analysis. AD, ZA, HH, collected data. AD, NO, NKM, MA1, MA2 and HE-Z participated in conceiving and designing the research, revising the article and collecting data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the approval and funding of the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute (NNFTRI) (Grant number. 1394.20/16-10-2015).

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available upon request after approval by the authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute’s (NNFTRI’s) ethics committee (approval code was IR.SBMU.nnftri.Rec.1394.20). Written informed consent was obtained from students and their parents, prior to commencement of the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Azam Doustmohammadian, Email: doost_mohammadi@yahoo.com.

Nasrin Omidvar, Email: omidvar.nasrin@gmail.com.

Nastaran Keshavarz-Mohammadi, Email: n_keshavars@yahoo.com.

Hassan Eini-Zinab, Email: hassan.eini@gmail.com.

Maryam Amini, Email: maramin2002@yahoo.com.

Morteza Abdollahi, Email: morabd@yahoo.com.

Zeinab Amirhamidi, Email: zeynab.amirhamidi@gmail.com.

Homa Haidari, Email: homa_haidari@yahoo.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13104-020-05123-0.

References

- 1.Sarrafzadegan N, Baghaei A, Sadri G, Kelishadi R, Malekafzali H, Boshtam M, Amani A, Rabie K, Moatarian A, Rezaeiashtiani A. Isfahan healthy heart program: evaluation of comprehensive, community-based interventions for non-communicable disease prevention. Prev Control. 2006;2(2):73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.precon.2006.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali MK, Rabadan-Diehl C, Flanigan J, Blanchard C, Narayan KM, Engelgau M. Systems and capacity to address noncommunicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries. Sci Transl Med. 2013 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . Jakarta declaration on health promotion into the 21st century. Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popkin BM. What can public health nutritionists do to curb the epidemic of nutrition-related noncommunicable disease? Nutr Rev. 2009;67(Suppl 1):S79–S82. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velardo S. The nuances of health literacy, nutrition literacy, and food literacy. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47(4):385. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.04.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaitkeviciute R, Ball LE, Harris N. The relationship between food literacy and dietary intake in adolescents: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(4):649–658. doi: 10.1017/s1368980014000962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nutbeam D, Kickbusch I. Advancing health literacy: a global challenge for the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15(3):183–184. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vidgen HA, Gallegos D. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite. 2014;76:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghassemi H, Harrison G, Mohammad K. An accelerated nutrition transition in Iran. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(1A):149–155. doi: 10.1079/phn2001287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diethelm K, Jankovic N, Moreno LA, Huybrechts I, De Henauw S, De Vriendt T, Gonzalez-Gross M, Leclercq C, Gottrand F, Gilbert CC, Dallongeville J. Food intake of European adolescents in the light of different food-based dietary guidelines: results of the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Study. Public health nutrition. 2012;15(3):386–398. doi: 10.1017/s1368980011001935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savige GS, Ball K, Worsley A, Crawford D. Food intake patterns among Australian adolescents. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16(4):738–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vidgen HA,Gallegos D. What is food literacy and does it influence what we eat: a study of Australian food experts. Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. 2011. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/45902/.

- 13.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doustmohammadian A, Omidvar N, Keshavarz-Mohammadi N, Abdollahi M, Amini M, Eini-Zinab H. Developing and validating a scale to measure food and nutrition literacy (FNLIT) in elementary school children in Iran. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):0179196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doustmohammadian A, Keshavarz Mohammadi N, Omidvar N, Amini M, Abdollahi M, Eini-Zinab H, Amirhamidi Z, Esfandiari S, Nutbeam D. Food and nutrition literacy (FNLIT) and its predictors in primary schoolchildren in Iran. Health Promot Int. 2018 doi: 10.1093/heapro/day050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.FAO/WHO . Human Vitamin and Mineral Requirements. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation. Rome: FAO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatloy A, Torheim L, Oshaug A. Food variety Ð a good indicator of nutritional adequacy of the diet? A case study from an urban area in Mali, West Africa. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:891–898. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haines PS, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. The diet quality index revised: a measurement instrument for populations. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(6):697–704. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geboers B, de Winter AF, Luten KA, Jansen CJ, Reijneveld SA. The association of health literacy with physical activity and nutritional behavior in older adults, and its social cognitive mediators. J Health Commun. 2014;19(sup2):61–76. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.934933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bostock S, Steptoe A. Association between low functional health literacy and mortality in older adults: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e1602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SY, Sim S, Park B, Kong IG, Kim JH, Choi HG. Dietary habits are associated with school performance in adolescents. Medicine. 2016;95(12):e3096. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000003096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoellner J, Connell C, Bounds W, Crook L, Yadrick K. Nutrition literacy status and preferred nutrition communication channels among adults in the lower mississippi delta. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(4):A128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization . Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. Geneva: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . AnthroPlus software, software for assessing growth and development of the world’s children. Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aadahl M, Jørgensen T. Validation of a new self-report instrument for measuring physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(7):1196–1202. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074446.02192.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelishadi R, Rabiei K, Khosravi A, Famouri F, Sadeghi M, Rouhafza H,Shirani S. Assessment of physical activity of adolescents in Isfahan. 2001.

- 27.Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W,Cook J. Guide to measuring household food security. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security in the United States: Revised 2000. No. 6. March 2000. USDA, Food and Nutrition Services, Alexandria, VA., 2000

- 28.Rafiei M, Nord M, Sadeghizadeh A, Entezari MH. Assessing the internal validity of a household survey-based food security measure adapted for use in Iran. Nutr J. 2009;8(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burrows TL, Lucas H, Morgan PJ, Bray J, Collins CE. Impact evaluation of an after-school cooking skills program in a disadvantaged community: back to basics. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2015;76(3):126–132. doi: 10.3148/cjdpr-2015-005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Utter J, Denny S, Lucassen M, Dyson B. Adolescent cooking abilities and behaviors: associations with nutrition and emotional well-being. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(1):5. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laska MN, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Does involvement in food preparation track from adolescence to young adulthood and is it associated with better dietary quality? Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(7):1150–1158. doi: 10.1017/s1368980011003004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azizi H, Asadollahi K, Esmaeili ED, Mirzapoor M. Iranian dietary patterns and risk of colorectal cancer. Health Promot Perspect. 2015;5(1):72. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2015.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talagala IA, Arambepola C. Use of food labels by adolescents to make healthier choices on snacks: a cross-sectional study from Sri Lanka. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:739. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3422-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delshadian Z, Koushki M, Mohammadi R, Mrtazavian A. Evaluation of food labeling for dairy, meat and fruit juice products launched in Tehran market. Iranian J Food Sci Technol. 2015;13(1):83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Omidvar N, Amini M, Zahedi-Rad M, Khatam A. Content analysis of school textbooks in a view of improving nutritional knowledge and skills of primary school children. The 2th international and the 14th Iranian nutrition congress. 4–7 September,Tehran. 2016.

- 36.Worsley A. Nutrition knowledge and food consumption: can nutrition knowledge change food behaviour? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2002;11(Suppl 3):S579–S585. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-6047.11.supp3.7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. STROBE study conduct and participant flow of the study.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2. The nutrient adequacy ratio percent of certain nutrients by sex in 10–12 years students in Tehran (n = 493).

Additional file 3: Table S1. Adjusted Odd Ratios (95% CI) of nutrient adequacy ratio (MAR%/NAR%) of certain nutrients for FNLIT scale and its subscales in 10–12 years students in Tehran (n = 493).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available upon request after approval by the authors.