Abstract

Background

The lack of locally validated screening instruments contributes to poor detection of depression in primary care. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a brief and freely available screening tool which was developed for primary care settings; however, its accuracy may be affected by the population in which it is administered. This study aimed to determine the validity and reliability of PHQ-9 for screening depression in a primary care population in Botswana.

Methods

Data was collected from a conveniently selected sample of 257 adult primary care attendants. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) depression module was used as a gold standard to assess criterion validity.

Results

Sensitivity and specificity of the PHQ-9 for screening for major depression were 72.4 and 76.3 respectively at a cut off score of nine or more. The area under the ROC curve was 0.808. The PHQ-9 demonstrated good internal consistency with a Cronbach alpha of 0.799. Criterion validity was demonstrated by significant correlation (r = 0.528, p < 0.001) between PHQ-9 and the MINI. Significant negative correlation between PHQ-9 scores and all four domains of the WHO quality of life questionnaire- brief version scores demonstrated good convergent validity.

Conclusions

The PHQ-9 is a reliable and valid instrument to screen for depression in primary care facilities in Botswana. Primary care clinicians in Botswana may use the PHQ-9 to screen for depression with a cut –off score of nine. Further studies should focus on integrating routine depression screening in primary care.

Keywords: Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Primary health care, Botswana, Depression, Validity, Reliability

Background

Depression is an important public health problem. It is a disabling chronic mental health problem commonly encountered in primary care. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, unipolar depressive disorders will become the leading cause of the global burden of disease by 2030 (World Federation for Mental Health (WFMH), 2012).

The prevalence of depression is markedly higher in people with other medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases, for example: 17 to 28% of patients with cardiovascular conditions and diabetes mellitus have been found to have depression [1, 2]. The co-morbidity of chronic conditions and depressions is associated with worse outcomes [3, 4]. Because most people with chronic diseases are diagnosed and managed in primary care, detecting depression at this early stage may improve outcomes.

WHO mental health GAP Intervention Guide has shown that depression can be reliably diagnosed and treated in primary care [5]. Despite treatment for depression in primary care being feasible, affordable and cost-effective [6]; the condition is often underdiagnosed and undertreated in primary care settings, especially in low to middle income countries (LMIC) [7]. Factors such as: inadequate numbers of specialised mental health workers, stigma associated with mental illness, and lack of locally validated screening instruments contribute to poor rates of diagnosis and treatment of depression in primary care.

Screening tools, if used appropriately may help health care workers to accurately identify patients with depressive disorders and initiate appropriate management. There are several screening and diagnostic tools available for depression [8, 9], however, not all of the instruments are suitable for use in primary care settings. The use of some depression screening and or diagnostic tools is limited by cost, time needed to administer the tools and in the case of self-administered tools, the patient’s ability to accurately complete the tool.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) was specifically developed for use in primary care settings [10], is available at no cost and has been validated in several settings to screen for depression [9–12]. As with many diagnostic tools the accuracy of the PHQ-9 may be affected by the population in which it is administered [13, 14]. Although a study of the PHQ-9 amongst 4 different ethnic groups found that the interpretation of the PHQ-9 did not differ amongst the ethnic groups, all four groups were in America and could have similar understanding of depression based on a shared environment [15]. It is therefore important to determine the optimal cut-off point when screening for depression using the PHQ-9 in a specific population.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the validity and reliability of an interviewer administered PHQ-9 for screening depression among primary care patients in Botswana. The MINI major depressive episode module was used as a reference standard. This is the first study to investigate the reliability and validity of a depression screening tool in Botswana.

Methods

Study design and site description

The study utilised a cross sectional design. The study was conducted at two primary care facilities in Gaborone, the capital and largest city in Botswana (population ~ 200,000) [16]. The two facilities were purposively selected to make the sample heterogeneous. One facility is located in a low-income area and the other in a predominantly middle to high income area. The two facilities also have a psychiatric nurse on site, who were crucial in providing further management to study participants who were found to have depression.

Study population

The study targeted adult patients attending the selected clinics during the months of May and June 2019. Convenience sampling was used to select potential participants, selecting patients in the order they came to the clinic. To be included in the study, patients had to be 18 years or older and be able to comprehend and complete study components in Setswana or English. Patients with moderate to severe intellectual disability, experiencing acute psychotic symptoms and having any unstable medical condition were not included in the study.

Measures

Researcher designed socio demographic clinical questionnaire

The researchers designed an instrument to capture social and demographic data such as gender and income. The instrument also screened for history of chronic medical conditions including hypertension, cancer, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and family history of any mental illness.

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

For this study we used the English version of the PHQ-9 by Kroenke et al. to screen for depression [10]. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item instrument used to screen for depression. Respondents indicate frequency of depression symptoms in the preceding 2 weeks on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (nearly every day), for a total score ranging from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating increased likelihood of a major depressive disorder. Total scores are interpreted as follows: Minimal depression (0–4), Mild depression (5–9), Moderate depression (10–14) and Severe depression (20–27) [10]. In the study by Kroenke et al. (2001); total scores of 10 or more on the PHQ-9 predicted a depressive disorder at a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88%. The PHQ-9 demonstrated an excellent internal reliability with a Cronbach’s α of 0.89 [10]. The PHQ-9 has been used previously in Botswana [17].

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) is a short diagnostic structured interview developed in Europe and the United States to explore 17 psychiatric disorders [18, 19]. It is fully structured to allow administration in about 15 to 20 min even by non-specialized interviewers [20, 21]. The MINI-plus demonstrates good sensitivity, specificity, validity and reliability in the assessment of psychiatric disorders [18, 20, 21]. The major depressive episode module was used in this study as a gold standard.

World Health Organization Quality of Life scale Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF)

The instrument is used to assess cross cultural quality of life across four domains: Physical health, psychological health, social relationships and environmental health. It assesses the respondent’s perceptions in the context of their standards, concerns and culture [22]. Respondents are requested to endorse perceived quality of life on a 5-point likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely) with higher scores indicating a higher quality of life [23]. The WHOQOL-BREF has demonstrated good to excellent psychometric properties and is reliable with a Cronbach α of more than 0.7 for all domains [23].

Data collection procedures

Research assistants were trained by the authors to administer the English and Setswana versions of socio-demographic questionnaire, the PHQ-9 and the WHOQOL-BREF and the MINI major depressive episode module.

Participants were recruited conveniently by selecting consecutive patients from the consultation waiting room. Those interested to participate in the study were directed to a research assistant in a private room. A written informed consent was obtained before commencing with data collection. Each participant was sequentially interviewed by two research assistants in either Setswana or English according to the participant’s preference. The first research assistant administered the socio-demographic questionnaire and the PHQ-9. Upon completion of the first interview each participant was then directed to a different room where the second research assistant (a Bachelor of Psychology graduate) who was blinded to the results of the PHQ-9 screening, then administered the MINI major depressive episode module and the WHOQOL-BREF.

Participants who were found to be suicidal or who screened positive for depression were referred to a psychiatric nurse stationed at the facility for further management.

Data analysis

Items means, standard deviations, frequencies and percentages were calculated for the socio-demographic variables. Independent samples t-tests was carried out to compare the mean PHQ-9 scores in the groups of depressed and not depressed patients according to MINI-Plus diagnosis.

Reliability

In order to investigate the reproducibility and consistency of PHQ-9, reliability coefficients as measured by Cronbach’s alpha were calculated.

Concurrent and convergent validity

Using spearman’s correlation analysis, the relationship between scores of PHQ-9 and MINI-plus diagnosis was investigated to determine the magnitude of the relationship between the two measures. Convergent and concurrent validity require that PHQ-9 should correlate with MINI-Plus diagnosis whilst it inversely correlates with quality of life as determined by the WHOQoL-BREF.

Factor structure

Before performing factor analysis, the correlation matrix was inspected to check for the strength of correlation and then factorability was tested using explanatory factor analysis using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. We calculated KMO = 0.838 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (469.303, df = 36, p < 0.001) making factor analysis an appropriate method.

Sensitivity and specificity

For each PHQ-9 cutoff point, sensitivity or true positive rate (proportion of individuals with MDE according to MINI criteria that correctly identified by PHQ-9), specificity or true negative rate (proportion of individuals without MDE according to the gold standard correctly identified as such by PHQ-9), Positive predictive value +PPV (proportion of true positives among all positives identified by the PHQ-9) and Negative predictive value -NPV (proportion of true negatives among all those who will score negative by PHQ-9 was calculated. Positive likelihood ratio + LR (probability of an individual without the condition having a positive test) and Negative likelihood ratio –LR (probability of an individual without the condition having a negative test) 95% confidence intervals for each of these parameters was reported.

Youden’s index was used as a criterion for choosing the “optimal” threshold value for the PHQ-9 test, the threshold value for which the value of [sensitivity + specificity − 1] is maximized.

Criterion validity was assessed by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The PHQ-9 point showing simultaneously the highest sensitivity and specificity was evaluated using the ROC curve. PHQ-9’s accuracy was estimated by the area under the ROC curve. All analyses were performed using Stata® version 14.0 software.

Results

Study sample characteristics

Majority of the participants in our study were female at 66.9% (n = 172) and the mean age of our participants was 34.3 years. The most common chronic diagnosis was HIV at 21.6% (n = 60) and alcohol was the most commonly used substance. Only 2.4% of the study participants had previously been diagnosed with a mental illness. Other characteristics are as depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants characteristics

| Variable | Category | Frequency (N = 257) |

Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 172 | 66.9 |

| Male | 85 | 33.1 | |

| Age | Mean; Median; Range | 34.3; 32.0; 18–79 | |

| Age | 18–24 Years | 70 | 27.2 |

| 25 and Above | 187 | 72.8 | |

| Marital status | Single | 63 | 24.6 |

| In a relationship | 87 | 34.0 | |

| Married | 29 | 11.3 | |

| Widowed | 8 | 3.1 | |

| Divorced | 10 | 3.9 | |

| Cohabiting | 59 | 23.0 | |

| Missing | 1 | ||

| Employment status | Unemployed | 60 | 23.3 |

| Self Employed | 35 | 13.6 | |

| Part Time | 9 | 3.5 | |

| Casual labourer | 9 | 3.5 | |

| Full time Employment | 125 | 48.6 | |

| Student | 19 | 7.4 | |

| Religiona | Islam | 4 | 1.5 |

| Christianity | 226 | 87.3 | |

| African Tradition religion | 13 | 5.0 | |

| Other | 15 | 5.8 | |

| None | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Missing | 2 | ||

| Education Level | Never went to school | 6 | 2.3 |

| Primary | 29 | 11.3 | |

| Junior Secondary | 85 | 33.1 | |

| Senior Secondary | 73 | 28.4 | |

| Tertiary | 64 | 24.9 | |

| Diagnosisa | HIV | 60 | 21.6 |

| Hypertension | 44 | 15.8 | |

| Stroke/CVA | 6 | 2.2 | |

| Diabetes | 5 | 1.8 | |

| Other | 21 | 7.6 | |

| None | 142 | 51.1 | |

| Missing | 4 | ||

| Diagnosis | None | 142 | 56.1 |

| One | 89 | 35.2 | |

| Multiple/Comorbid | 22 | 8.7 | |

| Missing | 4 | ||

| Incomea | Below P600 | 45 | 17.6 |

| 600–2399 | 106 | 41.4 | |

| 2400–4199 | 44 | 17.2 | |

| 4200–6000 | 23 | 9.0 | |

| Above 6000 | 19 | 7.4 | |

| Not Disclosed | 19 | 7.4 | |

| Missing | 1 | ||

| Substance Use | Alcohol | 110 | 37.4 |

| Dagaa | 14 | 4.8 | |

| Tobacco | 31 | 10.5 | |

| other-Name | 2 | 0.7 | |

| No | 137 | 46.6 | |

| Missing | 2 | ||

| Substance Use | None | 137 | 53.7 |

| One | 88 | 34.5 | |

| Multiple | 30 | 11.8 | |

| Missing | 2 | ||

| Relative with mental Illness | Yes | 59 | 23.2 |

| No | 179 | 70.5 | |

| Don’t Know | 16 | 6.3 | |

| Missing | 3 | ||

| Relative with mental illness | No | 195 | 76.8 |

| Yes | 59 | 23.2 | |

| Missing | 3 | ||

| History of mental illness | Yes | 6 | 2.4 |

| No | 249 | 97.6 | |

| Missing | 2 | ||

| Missing | 2 | ||

aThe numbers do not add up to 257 because the participants answered more than one option

Prevalence of depression

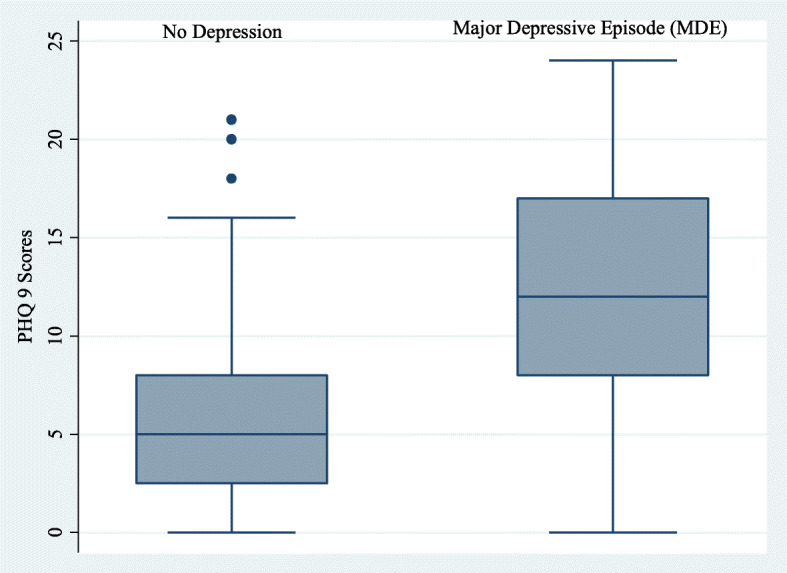

A total of 105 participants fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode, using the gold standard MINI depression module corresponding to a prevalence of 40.9% (95% C. I 35.0–47.1). The mean depression scores in the PHQ-9 were significantly higher among the depressed as compared to the non-depressed as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Box diagram and distribution scores of the PHQ-9 scores for participants with depression and those without depression

Reliability of PHQ-9

Table 2 presents the results of reliability. The PHQ-9 demonstrated good internal reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.799.

Table 2.

Reliability of PHQ-9

| PHQ-9 Items | PHQ-9 Questions | Scale Mean if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | Items Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-1 | Little interest or fun in doing things | 7.80 | 0.540 | 0.773 | 0.90 ± 1.08 |

| PHQ-2 | Feeling down, depressed or hopeless | 7.34 | 0.602 | 0.764 | 1.36 ± 1.17 |

| PHQ-3 | Trouble falling asleep, staying asleep or sleeping too much | 7.44 | 0.484 | 0.781 | 1.26 ± 1.23 |

| PHQ-4 | Feeling tired or having little energy | 7.62 | 0.456 | 0.784 | 1.08 ± 1.15 |

| PHQ-5 | Poor appetite or overeating | 7.66 | 0.494 | 0.779 | 1.04 ± 1.19 |

| PHQ-6 | Feeling bad about yourself, or that you’re a failure or have let yourself or your family down | 7.57 | 0.456 | 0.784 | 1.13 ± 1.15 |

| PHQ-7 | Trouble concentrating on things such as reading the newspaper or watching television | 7.68 | 0.522 | 0.775 | 1.02 ± 1.11 |

| PHQ-8 | Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed. Or the opposite | 8.15 | 0.404 | 0.790 | 0.55 ± 0.97 |

| PHQ-9 | Thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way | 8.33 | 0.466 | 0.784 | 0.37 ± 0.82 |

| Overall | Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.799 | 8.65 ± 6.1 | ||

Sensitivity and specificity

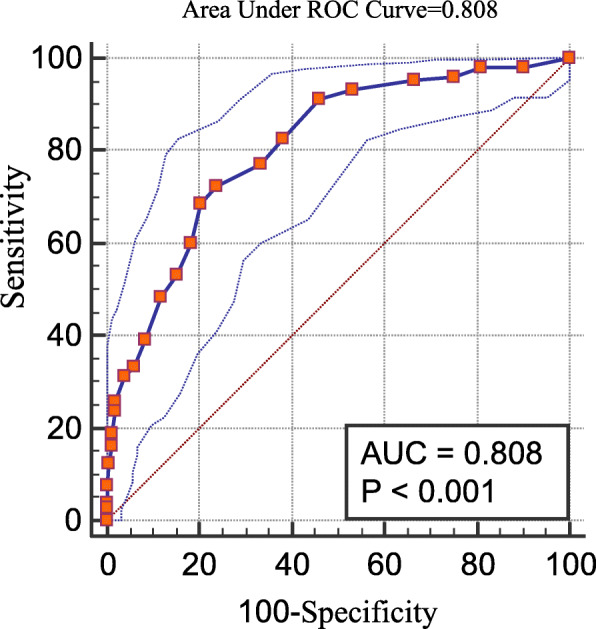

Table 3 shows sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratio, positive predictive value and negative predictive value for each of the PHQ-9 cutoff points compared to the gold standard interview (MINI). As expected, sensitivity decreased progressively as the cutoff points increased, with a marked decrease between the ≥10 and ≥ 11 cutoff points (from 68.6 to 60.0%) while specificity between these two cutoff points increased from 79.6 to 81.6%. The standard cut off score of 10 or higher yielded a sensitivity of 68.6 and a specificity of 79.6. Both Youden’s index and the cutoff point of maximum sensitivity and specificity according to the Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) (Fig. 2) indicate the ≥9 cutoff point as most suitable for identifying individuals at increased risk of having depression in this population. At total of 112 individuals (43.6%; 95% C. I 37.4–49.4) scored ≥9 in the PHQ-9 scale. Sensitivity at this point was 72.4% (95% C. I 62.8–80.7) and specificity of 76.3% (95%CI 68.7–82.5).

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, +LR, −LR, PPV, NPV, accuracy for different PHQ-9 cut-off points compared to the gold standard MINI and Youden’s index

| Cut-off Points | N(%) | Sensitivity (95% C.I) | Specificity (95% C.I) | +LR (95% C.I) | -LR (95% C.I.) | PPV (95% C.I) | NPV (95% C.I) | Youden’s Indexa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥5 | 179 (69.6%) | 93.3 (86.7–97.3) | 46.7 (38.6–55.0) | 1.8 (1.5–2.0) | 0.14 (0.07–0.3) | 54.7 (50.8–58.6) | 91 (82.9–95.5) | 0.4004 |

| ≥6 | 166 (64.6%) | 91.4 (84.4–96.0) | 54.0 (45.7–62.1) | 2.0 (1.7–2.4) | 0.16 (0.08–0.3) | 57.8 (53.3–62.2) | 90.1 (82.7–94.5) | 0.4538 |

| ≥7 | 145 (56.4%) | 82.9 (74.3–89.5) | 61.8 (53.6–69.6) | 2.2 (1.7–2.7) | 0.28 (0.2–0.4) | 60 (54.6–65.2) | 83.9 (77.1–89.0) | 0.4470 |

| ≥8 | 132 (51.4%) | 77.1 (67.9–84.8) | 66.5 (58.3–73.9) | 2.3 (1.8–2.9) | 0.34 (0.2–0.5) | 61.4 (55.4–67.0) | 80.8 (74.4–85.9) | 0.4359 |

| ≥9 | 112 (43.6%) | 72.4 (62.8–80.7) | 76.3 (68.7–82.8) | 3.1 (2.2–4.2) | 0.36 (0.3–0.5) | 67.9 (60.8–74.2) | 80 (74.3–84.7) | 0.4870 |

| ≥10 | 103 (40.1%) | 68.6 (58.8–77.3) | 79.6 (72.3–85.7) | 3.4 (2.4–4.7) | 0.39 (0.3–0.5) | 69.9 (62.3–76.5) | 78.6 (73.2–83.1) | 0.4818 |

| ≥11 | 91 (35.4%) | 60.0 (50.0–69.4) | 81.6 (74.5–87.4) | 3.3 (2.3–4.7) | 0.49 (0.4–0.6) | 69.2 (60.9–76.5) | 74.7 (69.8–79.1) | 0.4158 |

| ≥12 | 79 (30.7%) | 53.3 (43.3–63.1) | 84.9 (78.2–90.2) | 3.5 (2.3–5.3) | 0.55 (0.4–0.7) | 70.9 (61.6–78.7) | 72.5 (68.0–76.6) | 0.3820 |

| ≥13 | 69 (26.8%) | 48.6 (38.7–58.5) | 88.2 (81.9–92.8) | 4.1 (2.5–6.6) | 0.58 (0.5–0.7) | 73.9 (63.8–82.0) | 71.3 (67.1–75.1) | 0.3673 |

| ≥14 | 54 (21.0%) | 39.1 (29.7–49.1) | 91.5 (85.8–95.4) | 4.6 (2.6–8.1) | 0.67 (0.6–0.8) | 75.9 (64.0–84.8) | 68.5 (64.9–71.8) | 0.3050 |

LR + Positive likelihood ratio, LR– Negative likelihood ratio, PPV Positive predictive value, NPV Negative predictive value; (a) Youden’s Index = [Sensitivity + Specificity-1]

Fig. 2.

Receiver operator characteristics curve for the performance of Patient Health Questionnaire Scale (PHQ-9) compared to MINI

The PHQ-9 demonstrated very good accuracy with an area under the ROC (AUC) of 0.808 (95% C. I 0.755–0.854) as depicted in Fig. 2.

Concurrent and convergent validity

The PHQ-9 scores correlated with the results of MINI (r = 0.528, p < 0.001). As expected, higher PHQ-9 score correlated with lower quality of life in all domains of the WHOQoL-BREF. The correlation between PHQ-9 scores and WHOQoL-BREF scores on all the four domains were found to have a significant negative correlation in all the four domains of WHOQoL-BREF (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlations between PHQ-9 depression scores, quality of life domain scores and depression

| Pearson’s Correlations | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PHQ-9 Depression Scores | 1 | |||||

| 2. Physical Quality of Life | −0.330a | 1 | ||||

| 3. Psychological Quality of Life | −0.468a | 0.348a | 1 | |||

| 4. Social Quality of Life | −0.411a | 0.377a | 0.414a | 1 | ||

| 5. Environmental Quality of Life | −0.499a | 0.403a | 0.483a | 0.529a | 1 | |

| 6. Major Depression Episodeb | 0.525a | −0.244a | −0.346a | −0.299a | −0.389a | 1 |

a Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), b Spearman’s rho Correlation

Exploratory factor analysis

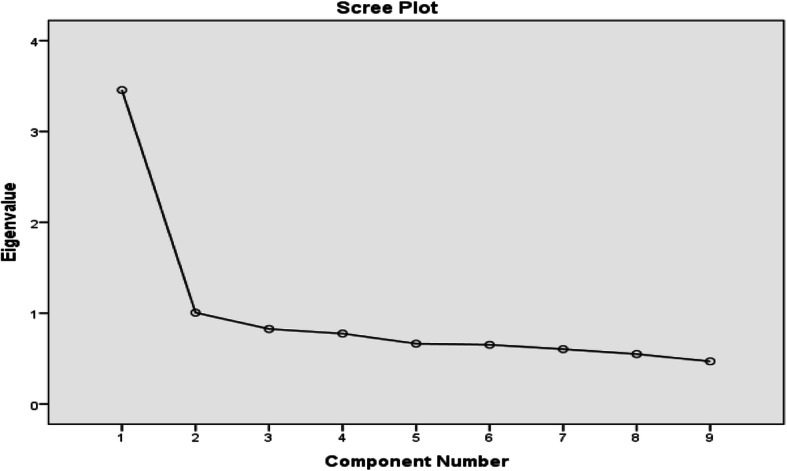

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO = 0.838). and Bartlett test of sphericity (469.308, df = 36, P < 0.001) justified a dimension reducing procedure such as the factor analysis. The measure of sampling adequacy was > 0.80, so the items could be considered suitable for factor analyses. The scree plot (Fig. 3) revealed one dominant dimension with a big decrease between first and second eigenvalues and small decreases afterward (eigenvalues: 3.4, 1.0, 0.8, 0.7, 0.66, 0.65, 0.6, 0.5 and 0.469). Factor loadings ranged from 0.54 to 0.82. The percentage of total variance explained by the first factor was 38.4% and the second factor explained 11.2% of the variance.

Fig. 3.

Scree-plot

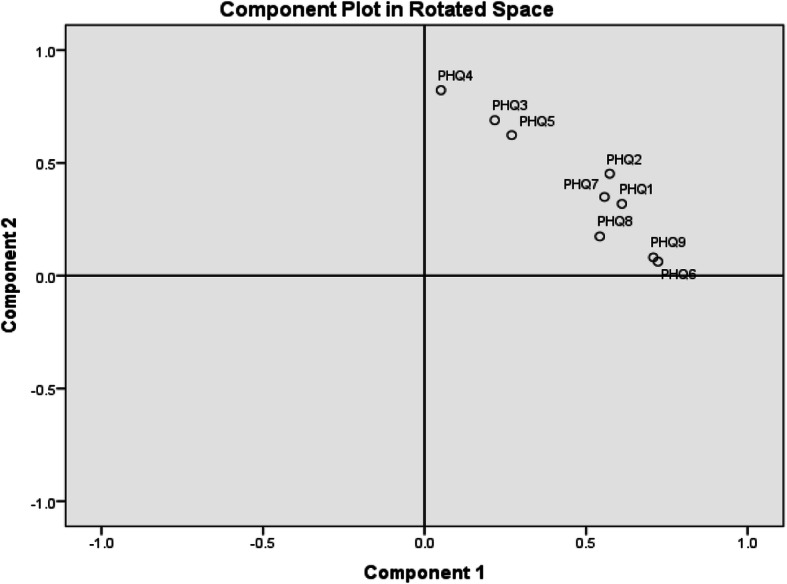

These two factors explained 49.6% of the variance as shown in the scree plot graph (Fig. 3). Factor 1 included questions 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, and 9 and factor two 3, 4, and 5 (Table 5). These factors did not reflect the multidimensional structure PHQ-9. However, component rotated space (Fig. 4) revealed only one factor and to judge the strength of the measurement dimension, the following cut off points were used for variance explained by the measure: > 40% is considered a strong measurement dimension, > 30% is considered a moderate measurement dimension, and > 20% is considered a minimal dimension. Factor 1 explained approximately 40% of the variance which is supportive of unidimensionality.

Table 5.

Exploratory factors loadings and explained variance after rotation for the PHQ-9 items

| Factors | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings | Eigen Values | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Cronbach’s Alpha | ||

| Factor 1 | PHQ-1 | 0.611 | 3.456 | 38.394 | 38.394 | 0.749 |

| PHQ-2 | 0.573 | |||||

| PHQ-6 | 0.722 | |||||

| PHQ-7 | 0.557 | |||||

| PHQ-8 | 0.542 | |||||

| PHQ-9 | 0.708 | |||||

| Factor 2 | PHQ-3 | 0.689 | 1.006 | 11.173 | 49.567 | 0.615 |

| PHQ-4 | 0.823 | |||||

| PHQ-5 | 0.623 | |||||

Fig. 4.

Component Plot in Rotated Space

Discussion

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability [24] and the second leading cause of years of life lived with disability [25]. However, depression still remains under-recognized in primary care settings [26]. Identifying depression in primary care patients can be a challenge, especially in busy clinics. A short and valid screening tool can assist in the identification of patients with depression in different primary care settings. This study aimed to estimate the reliability and validity of PHQ-9 for the identification of depression in patients attending primary health care facilities in Botswana.

Using the gold standard MINI depression module, 40.9% (95% C. I 35.0–47.1) of the study population met the criteria for current Major Depressive Episode. This was higher than the prevalence of 38% in an earlier study of HIV-infected patients in Botswana [27] and the prevalence of 30.3% found among primary care patients in Malawi [28], but lower than 56% in a South African Primary care population [29]. The variance in the studies could be explained by the different depression diagnostic tools used in the studies. Additionally, factors such as HIV status, socio-economic status and cultural influences on the understanding of depression may influence the results.

The internal consistency analysis of the PHQ-9 was assessed using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and it was found to be 0.799. This indicates that the PHQ-9 has acceptable predictive performance. Our findings were comparable or slightly lower to that seen in validation studies in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa whose Cronbach alpha values were found to be 0.76 in South Africa [11], 0.83 in Malawi [30] and 0.85 in Ethiopia [31].

When the PHQ-9 was compared with the gold-standard diagnosis of the MINI, it performed well showing reasonable accuracy in identifying cases of depression. The area under the ROC curve was found to be 0.808, suggesting good diagnostic ability of the PHQ-9 score. Kroenke at al., (2001) used a cut off, of 10, with a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 88%. We found that, using the PHQ-9, depression was best identified by a cut off nine. At this cut off, the PHQ-9 had moderately high sensitivity (72.4%) and specificity (76.3%) in our study population. A validation study in a chronic disease out-patient clinic in Malawi also determined the optimal cut-of score to be nine, however the sensitivity was lower than in our study (64%) whilst the specificity was higher at 94% [30]. The performance of the PHQ-9 was similar to that from a range of other settings in sub-Saharan Africa [11, 12] and indicate that the PHQ-9 has reasonable sensitivity and specificity to be used as a screening tool for depression in this setting. Although the sensitivity and specificity values found in this study are not as high as found by Kroenke et al., (2001) this could be because of the use of the MINI as a gold standard; a recent meta-analysis showed that the sensitivity of the PHQ-9 was lower (0.77 versus 0.88) when using the MINI as the gold standard as compared to semi-structured interviews [32].

The construct validity of PHQ-9 was established by the factor analysis. All the items had factor loading in the range 0.54–0.82. Items related to low energy (0.82), feeling bad about self (0.72) and suicide (0.708) were most strongly related to the underlying construct meeting the diagnostic criteria for depression.

The PHQ-9 depression questionnaire appears to be a reliable and valid screening instrument for identifying depression in Botswana at a cut off score of nine or higher.

One of the strengths of this study is that it is the first to validate the PHQ-9 in Botswana. Another strength of our study includes the use of a clinical diagnostic gold standard to assess validity.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that the participants were drawn from only two primary health care facilities in the capital of Gaborone which may not be representative of the wider population. The use of convenience sampling presents a sampling error which limits generazibility of the findings.

Conclusion

It is through primary health care services that mental health disorders can be observed and diagnosed. Thus, to improve health outcomes of patients in primary care, mental health disorders such as depression should be integrated into routine management. High burden of disease and negative impact on health outcomes, highlight this need for early diagnosis and management of depression. Despite being a middle-income country, poverty and high levels of income inequality persist and this has been found to predict depression in our population. Our study, similar to previous studies, demonstrates that the PHQ-9 is a reliable and valid instrument to screen for depression in primary care facilities in Botswana. The maximal specificity and sensitivity at a cut off score of 9 in our population compared to a cut off of 10 found in previous studies underscores the importance of validating the PHQ-9 in different socio-cultural populations. We recommend that, further studies should focus on integration of routine depression screening using the PHQ-9 in primary care.

Acknowledgements

Our gratitude goes to University of Botswana: Office of Research and Development for funding the study.

The authors are grateful to the cooperation of the patients and staff from the two clinics where data was collected. We also thank our research assistants; Golekanye Morutwa, Boitshepo Mosupiemang, Tiro Motsamai, Kebakaone Marumo, Olorato Morerinyane, Kevin Tshidviso and Tebogo Majoo.

Abbreviations

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

- MINI

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- WHOQoL-BREF

World Health Organisation Quality of Life Scale Brief Version

Authors’ contributions

KM1 and KM2 conceptualised the study and developed the proposal. KM1 wrote the first draft, KM2 and GNW critically revised the intellectual content of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by University of Botswana Internal funding Round 36 research grant for early career researchers. The first and second author work at the University of Botswana. The University did not have any input in the development or implementation of the study or this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the University of Botswana Independent Review Board (UBR/RES/IRB/BIO/122) and the Botswana Ministry of Health and Wellness, Health Research and Development Division (13/18/1). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written consent to participate and confidentiality was maintained by use of serial codes in all questionnaires.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.American Heart Association . Depression after a cardiac event or diagnosis. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang H-J, Kim S-Y, Bae K-Y, Kim S-W, Shin I-S, Yoon J-S, et al. Comorbidity of depression with physical disorders: research and clinical implications. Chonnam Med J. 2015;51(1):8. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2015.51.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voinov B, Richie WD, Bailey RK. Depression and chronic diseases: it is time for a synergistic mental health and primary care approach. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(2) Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23930236. Cited 4 Sept 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.World Health Organization. WHO | WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP).: WHO. World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/en/. Cited 20 Feb 2017.

- 6.Araya R, Flynn T, Rojas G, Fritsch R, Simon G. Cost-effectiveness of a primary care treatment program for depression in low-income women in Santiago, Chile. Am J Psychiatry S2- Am J Insa. 2006;(8):1379–87 Available from: http://repositorio.uchile.cl/bitstream/handle/2250/127622/Araya_Ricardo.pdf?sequence=1. Cited 14 May 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.World Federation For Mental Health (WFMH). Depression: a global crisis. World Ment Heal Day. 2012;32 Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/wfmh_paper_depression_wmhd_2012.pdf.

- 8.Lloyd-Williams M, Spiller J, Ward J. Which depression screening tools should be used in palliative care? Palliat Med. 2003;17(1):40–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Nabbe P, Le Reste JY, Guillou-Landreat M, Munoz Perez MA, Argyriadou S, Claveria A, et al. Which DSM validated tools for diagnosing depression are usable in primary care research? A systematic literature review. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;39:99-105. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhana A, Rathod SD, Selohilwe O, Kathree T, Petersen I. The validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire for screening depression in chronic care patients in primary health care in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0503-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cholera R, Gaynes BN, Pence BW, Bassett J, Qangule N, Macphail C, et al. Validity of the patient health questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in a high-HIV burden primary healthcare clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2014;167:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monahan PO, Shacham E, Reece M, Kroenke K, Ong’Or WO, Omollo O, et al. Validity/reliability of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 depression scales among adults living with HIV/AIDS in Western Kenya. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):189–197. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0846-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhong Q, Gelaye B, Fann JR, Sanchez SE, Williams MA. Cross-cultural validity of the Spanish version of PHQ-9 among pregnant Peruvian women: a Rasch item response theory analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014;158:148–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi KL, Spitzer RL. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becker TD, Ho-Foster AR, Poku OB, Marobela S, Mehta H, Cao DTX, et al. “It’s when the trees blossom”: explanatory beliefs, stigma, and mental illness in the context of HIV in Botswana. Qual Health Res. 2019:104973231982752 Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1049732319827523. Cited 10 Feb 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Motlhatlhedi K, Setlhare V, Ganiyu A, Firth J. Association between depression in carers and malnutrition in children aged 6 months to 5 years. Afr J Prim Heal Care Fam Med. 2017;9(1):6. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Harnett Sheehan K, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):224–231. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl. 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinninti NR, Madison H, Musser E, Rissmiller D. MINI International Neuropsychiatric Schedule: Clinical utility and patient acceptance. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18(7):361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, et al. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):232–241. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. WHO | WHO Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF): WHO; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/whoqolbref/en/. Cited 1 Sept 2018.

- 23.Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial a report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO . Depression fact sheet N 369. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (London, England) 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawler K, Mosepele M, Seloilwe E, Ratcliffe S, Steele K, Nthobatsang R, et al. Depression among HIV-positive individuals in Botswana: a behavioral surveillance. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):204–208. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9622-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udedi M. The prevalence of depression among patients and its detection by primary health care workers at Matawale Health Centre (Zomba) Malawi Med J. 2014;26(2):34–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folb N, Lund C, Fairall LR, Timmerman V, Levitt NS, Steyn K, et al. Socioeconomic predictors and consequences of depression among primary care attenders with non-communicable diseases in the Western Cape, South Africa: cohort study within a randomised trial chronic disease epidemiology. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1194. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2509-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Udedi M, Muula AS, Stewart RC, Pence BW. The validity of the patient health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus in non-communicable diseases clinics in Malawi. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2062-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelaye B, Williams MA, Lemma S, Deyessa N, Bahretibeb Y, Shibre T, et al. Validity of the patient health questionnaire-9 for depression screening and diagnosis in East Africa. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(2):653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;365:l1476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.