Introduction and Basic Principles of Management

The recent onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created an unprecedented set of medical management problems, largely because of the rapid global speed of onset, the severity of management problems for approximately 5%-10% of patients, prevalence of asymptomatic carriers, and general lack of experience internationally in this type of pandemic care.1 The bat-human transmission of a novel coronavirus originated in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and had spread to most continents and 150 countries by March 11, 2020, when it was declared to be a pandemic. What has made this situation unique is the potential for spread by contact and aerosolized droplets with a potential dwell time of some hours in the air and longer on surfaces, with symptoms that can arise 2-14 days or longer after exposure,2 and with predominantly asymptomatic spread. Although the symptoms are quite characteristic, with fever, cough, fatigue, sputum production, dyspnea, and myalgia predominating, there is substantial overlap with the common cold, influenza, and seasonal allergies, which make early diagnosis more challenging.1 Sudden onset of loss of taste sensation has been described, although this is less helpful for the patient already on chemotherapy.

Limited data exist for COVID-19 infection outcomes in patients with cancer. Early reports from China have suggested that patients with cancer are twice as likely to become infected and are at high risk for severe clinical events defined as a need for ventilation, admission to an intensive care unit, or death.3,4 An additional study of 138 hospitalized patients in Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University suggested that hospital-acquired transmission accounted for 41.3% of admitted patients.5 Together, these findings highlight a critical need to redefine treatment goals and safety of our current cancer care delivery paradigm.

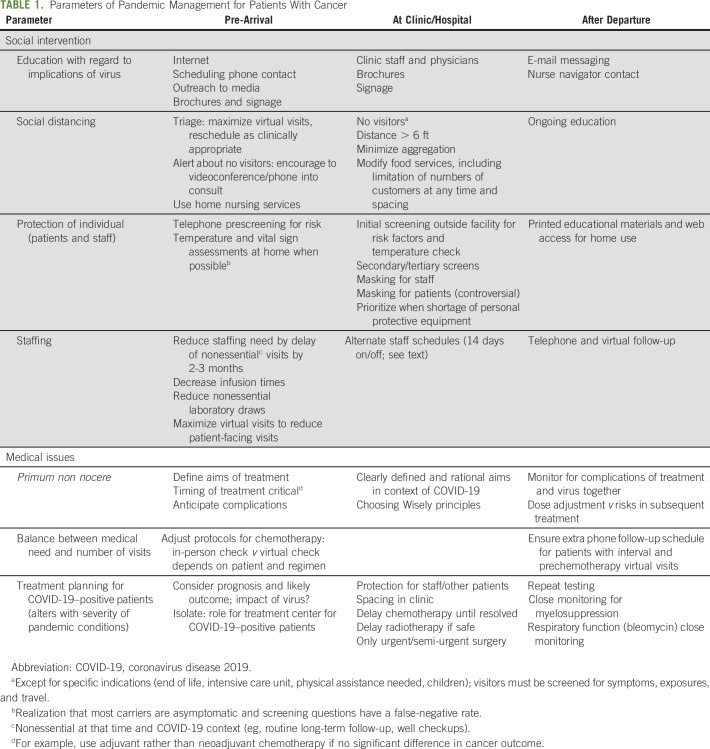

General principles of management were established during the evolution of the severe acute respiratory syndrome and Zika virus epidemics, and many have been applied de facto to the current situation (Table 1). However, the rapidity of global spread and the aforementioned features have mandated the development of creative strategies of management when scant definitive information is available in the literature.

TABLE 1.

Parameters of Pandemic Management for Patients With Cancer

Levine Cancer Institute (LCI) is an academic-hybrid, multisite cancer care facility with 25 locations in North Carolina and South Carolina serving urban and rural populations. LCI employs > 2,000 staff, including > 150 clinicians and scientists, and cares for > 17,000 new patients per year, with 200,000 visits per year. Approximately 2,000 patients are entered into cancer trials annually, with 65,000 seen in outreach education and cancer prevention activities, and > 600 bone marrow transplantations (BMTs) and 50 chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR T)–cell treatments have occurred since LCI was established within the Atrium Health system. Atrium Health comprises > 40 hospitals in three states, delivering care at 12 million encounters annually. To ensure the safest care for patients, draconian new approaches have been urgently required for both our health system and our cancer institute to deal with the pandemic. Because LCI involves a major teaching hospital, several rural and smaller urban hospitals, and office-based practices, we have designed an approach that caters to each setting. This article codifies these approaches to guide others in view of the paucity of published information.

Gaining Information From Other Sites

The standard LCI approach of tumor-specific management by multidisciplinary teams, which blends evidence-based data and clinical expertise and in-house data, has provided a platform for modified approaches to pandemic care on the basis of an amalgam of risk- and outcome-based considerations. We have initiated teleconferences with international physician leaders who have set treatment policies for patients affected by COVID-19, including an international webinar presented by the AAGL. We have learned from the scant peer-reviewed literature. One of our authors (L.M.) has had extensive experience in epidemic management of HIV and Zika virus at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease and with Doctors Without Borders. There has also been extensive and ongoing communication with other cancer centers.

Practical Aspects

The essence of management for oncology patients during a pandemic is protection that is focused on patients, their caregivers and families, and clinical staff (Table 1). To achieve this, interventions should include consideration of the demography of the patients and available physical facilities, staffing, and information technology. Other external factors such as the response from government, level of social chaos, policies developed by health insurance payers, and local government are crucial but beyond the scope of this article. The risk/benefit ratio is important in the choice of approach: The patient who is likely to be in a curative setting requires different considerations than one who faces management of a treatable, but incurable disease or one with end-of-life management. Equally, the likely toxicities of treatment (especially myelosuppression and cardiopulmonary toxicity) need to be considered carefully for patients at risk for COVID-19 infection.

Patient management.

The size of the clinical practice will dictate the scope and range of interventions that can be offered to individual patients: A huge multisite, multidisciplinary cancer practice will perforce have a great range and volume of extant resources at baseline, but the principles remain unchanged and can be adapted while considering the available staffing and clinical and fiscal resources. For example, although our practice has been able to draw on virtual clinical and social support of patients by > 30 nurse navigators, a reasonable alternative for small clinical practices would be to use an amalgam of nurse and/or office managers augmented, perhaps, by a social worker or community social support resources to achieve similar goals.

Irrespective of the size of the facility, social distancing is one of the foremost aspects of care, supported extensively by experience in China and Europe. Of importance, Taiwanese health officials have been meticulous in documenting travel histories and symptoms in the local population (after absolute border closure) and have used cell phone contact and tracking, augmented by fiscal penalties, to ensure that at-risk and affected patients practice social isolation meticulously. In the oncology clinic, social distancing can be achieved by the following:

Selection of patients for delay of appointments or virtual visits by telephone or videoconferencing to reduce absolute numbers and crowding; this is influenced by acuity and severity of the clinical problem, whether the patient is on active treatment or in post-treatment “well” surveillance, and at the same time, prescreening for symptoms of COVID-19 and exposures take place

Physical distancing and separation in the clinic, with improved efficiencies to reduce waiting times (eg, lengthened appointment times to 20 minutes); spacing of chairs in waiting areas

Adjustment of treatment regimens to reduce the need for patients to be in the hospital or clinic, provided that safety and outcome are not substantially affected (eg, alteration of intravenous to oral etoposide for small-cell carcinoma, altered radiotherapy fractionation for bone pain, reduced use of intravenous bone-stabilizing agents in metastatic prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy)

Use of day hospital or urgent cancer care unit to reduce visits to the emergency department augmented by expanded home nursing services by staff trained to manage oncology issues

These considerations are implemented before the arrival of patients, during clinic or hospital visits, and after departure, as summarized in Table 1. Criteria for patient-under-investigation testing have been defined by our health system and include influenza-like-illness (fever ≥ 100.4°F, subjective fever, plus cough or dyspnea) plus one risk factor (immunocompromised, lung disease [including asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], long-term care, homelessness, or imprisonment, or patient unable to give history). Availability of testing kits obviously influences implementation.

Staffing issues.

Similarly, safety of staff is of paramount importance. LCI has initiated an alternative staffing roster such that teams are “on deck” and “away” mostly for 14-day shifts in view of the incubation time for COVID-19,2 and this ensures a constant supply of COVID-19–negative staff. For high acuity, intense services, such as BMT, the on-deck team spends a week on the BMT unit and a week in outpatient clinics, and the teams then swap. The away team returns to service at 14 days, removing the first team from patient contact. When staff numbers do not permit this, options include amalgamation or simply closing units that are no longer able to provide staff because of the numbers of COVID-19–positive staff who are ill or in surveillance. Teams are constructed by using physicians and maximizing the use of advanced practice professionals (APPs), emphasizing their operations at the upper end of their licenses. Universal masking for all patient-facing staff is emphasized, contingent on supplies, and staff are required to wear scrubs or other washable clothing for patient facing. In view of personal protective equipment shortages, we have developed a three-dimensional printing mechanism to create our own clear plastic masks. If COVID-19 becomes ubiquitous, the rotation may be maintained to avoid staff exhaustion. Special considerations have been created for pregnant staff members, who are specifically rostered away from proven COVID-19–positive patients and, wherever possible, away from patient-facing roles.

At LCI, we have developed a specific clinic for COVID-19–positive well patients (without clinical syndrome of viral infection) that is staffed by clinician and staff volunteers. Increased personal protective equipment and more rigorous standard operating procedures have been evolved for this site, which are beyond the scope of this article.

Communication.

It is obvious that clear and defined communication for patients and families is essential in any cancer treatment algorithm, but this is even more important in the setting of a pandemic where fear and uncertainty abound. Verbal and written communication for patients and families is important to define the key issues that surround cancer management as well as the modifications created to deal with the pandemic and clear explanation for the reasons underlying those changes. Equally important is clear and repeated communication to staff, both written and by virtual meetings, most particularly about the changing demography and epidemiology of the pandemic, the supply of personal protective equipment, and repeated definition of the emphasis of safety for patients and staff. Presence of leadership in the clinical environment is also important in supporting morale, creating a calm environment, and reducing fear. All multisite tumor conferences, lectures, and teaching activities are carried out using virtual technology, with the majority of peer review conducted in most cases by the team rotated to non–patient-facing duties in the 14-day rotations.

Electronically Accessible Pathways

LCI created an electronic clinical pathways tool, Electronically Accessible Pathways, to provide standardized, evidence-based, continually updated clinical pathways for all LCI network providers and staff. The goal was to standardize care, provide access to patient services and clinical trials, promote specialized care by local providers, and deliver care in a standardized manner across a wide geographical region by giving access to standardized treatment approaches, diagnostic and molecular testing, clinical trials, and patient resources. The clinical pathways can be updated in near real time on the basis of the urgency of information. Users have easy access to updated clinical trials information, clinical notifications, patient and provider teaching documents, program information (eg, tobacco cessation), and other clinical resources centralized to a single site.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have created a new section that covers the COVID-19 updates that reflect the rapidly changing hospital operations and policies within hours, a litmus test on our pathway technology platform. For example, as infusion time slots and staffing presented new challenges, we have made systemwide changes to use particular regimens that save infusion visits and time without compromising patient safety or treatment efficacy. These edits occurred on the treatment pages so that providers were informed and directed on how to proceed. While this is a somewhat sophisticated approach that has leveraged an extant system, similar outcomes can be achieved using editable white boards or computerized share-point sites in a small office.

Radiation Oncology

The radiation oncology department at the LCI is a nine-site network that has ensured continued state-of-the-art treatment while using social distancing (Table 1). All follow-ups and consults are now conducted as virtual visits. The only patients who come to the clinic are those deemed after physician review to need treatment, and simulations and radiation are scheduled contemporaneously. Existing patients continue treatment to completion but with no visitors. Weekly on-treatment medical visits occur through virtual technology to maintain family engagement in the care of patients. Social distancing is enforced through widely spaced on-deck chairs. Secretarial and dosimetry staff work from home, and the physics staff have limited in-clinic hours. An alternate-week staffing model for all patient-facing aspects is in place. Each unit of therapists per machine is self-contained, with no rotational coverage from other staff. Each unit also is socially distanced from the other units. The at-home physicians and AAPs continue to engage in full support of the clinic and are the primary providers of remote follow-ups and consultations as well as peer review. The team has worked closely with the referring clinicians to establish triage strategies that ensure that a delay in treatment should have a minimal adverse effect on patient outcome. The most common delayed treatments include patients with low-risk breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ as well as patients with low-risk prostate cancer. When each patient’s case is peer reviewed, the reviewing physician also assesses potential for delay or alternate fractionation with consideration of hypofractionation, although we routinely adhered to the American Society for Radiation Oncology Choose Wisely guidelines for short palliative courses before the pandemic. Two low-volume centers were closed to allow transfer of staff to the remaining centers to facilitate alternating teams. The treatment processes and documentation are standardized and electronic, which facilitated staff transfers seamlessly.

BMT and CAR T

Largely on the basis of experience with other respiratory viruses, recipients of hematopoietic stem-cell transplants (HCTs), CAR T cells, or other immunosuppressive therapies are known to be at high risk of developing severe clinical infection. Thus, most HCT and CAR T-cell procedures have been canceled or delayed on the basis of parameters like chance of sustained disease-free survival, disease aggressiveness, and comorbidities. Patients are reviewed by disease-specific teams and then prioritized by the cellular therapy team. Recipients and donors are instructed to follow protective behavior before procedures. Recipients are screened and tested for COVID-19 within 72 hours of conditioning or lymphodepleting therapy.

Specific guidelines for the management of COVID-19–positive patients, patients in whom COVID-19 infection is suspected, and COVID-19–negative patients have been developed for the protection of patients and staff. COVID-19–negative inpatients with hematologic malignancies are housed on a protected environment floor with physicians, APPs, and nurses using appropriate personal protective equipment. COVID-19–positive patients are placed on a COVID-19–positive floor. Workflow for patients with febrile neutropenia incorporates standard COVID-19 risk stratification with clinical judgment. Direct patient exposure is minimized. Visitors are prohibited with very few exceptions, and where possible, telemedicine is used for patient interactions. One physical examination is performed each day by an APP or a physician. Rounding by the inpatient team is virtual. We work collaboratively with palliative care for goals-of-care discussions.

Similar principles are followed for outpatients as previously outlined for other specialties herein. Oral therapies are substituted for parenteral therapies wherever safe and effective. Nonessential laboratory tests and infusion visits are minimized. Transfusion guidelines have been revised and are more strictly enforced with lower RBC (hemoglobin, 7 g/dL) and platelet (10,000/μL) thresholds, commensurate with the clinical context. Oral electrolyte replacement therapy is used wherever possible. For transplant recipients and others receiving inhaled or intravenous pentamidine for Pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim or atovaquone has been substituted. Similar considerations apply to patients with sickle cell disease and other noncancer hematologic disorders, in all cases emphasizing patient safety.

Gynecologic Oncology

The challenges in gynecologic oncology are somewhat different in that faculty take primary responsibility for the delivery of chemotherapy in addition to extended time spent in the operating room. Clinic operations are symmetrical with other departments within LCI (as previously described). To decrease exposure risk, new patients are limited to those with known or suspected cancer, pelvic mass, or high-grade pre-invasive disease. New patient referrals with low-grade pre-invasive disease, ovarian cysts unlikely to represent malignancy, or hereditary mutations are delayed for 2-3 months. For established patients, LCI guidelines (as previously described) are followed, including policies to reduce nonessential visits and so forth. Infusion duration has been shortened when possible in conjunction with pharmacy. A rotational staffing model is used. Surgical considerations are summarized next.

Surgical Considerations

The departments of gynecologic oncology, surgical oncology, hepatobiliary surgery, and other subspecialty groups have adhered to a common approach to cancer surgery, again predicated on urgency of need versus patient and staff safety. All cases are categorized as essential or nonessential surgery; nonessential surgery is delayed to conserve resources and prevent exposures. In gynecologic oncology, essential surgeries are categorized according to a prioritization that is based on known cancer that requires urgent resection to obtain the best outcomes, known cancer that could be treated with an alternative strategy to achieve equivalent outcomes, pre-invasive high-grade disease or pelvic mass with normal markers, and elective surgery; these follow the Society of Gynecologic Oncology guidelines. Similar guidelines have been established by other specialty surgical societies.

Route of surgery and COVID-19 status are important considerations and are summarized in the Joint Statement by AAGL, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, and related organizations.6 Controversy surrounds the respective merits of laparoscopic versus open surgery in this context, with consideration of evacuating any smoke plume during open surgery or pneumoperitoneum into a closed system being crucial and the number of participating personnel being minimized. Clinic operations are the same as in other LCI departments.

Supportive Oncology

LCI has made a major commitment to patient and caregiver support. The department of supportive oncology incorporates sections of palliative medicine, cancer integrative medicine, psychological oncology, cancer rehabilitation, cardio-oncology, cancer nutrition, cancer navigation, and cancer survivorship. Many centers have simply discontinued many of these services, whereas our approach has been to leverage virtual or telemedicine wherever possible. Nonurgent appointments have been rescheduled, with urgent meetings altered to virtual consults and new patients carefully triaged depending on acuity. For new patients, referring clinicians are routinely contacted to determine urgency and need for in-person versus virtual consultation. Virtual platforms are used routinely except when in-person visits are required, and meticulous personal protection and room sterilization protocols are followed. LCI is built on an extensive nurse navigator program, with > 30 subspecialist navigators distributed throughout our network; their entire program has been shifted to telephone and virtual platforms with carefully scripted voice mails for outgoing messages and telephone identification blocking to facilitate incoming calls on personal cell phones. Navigators are available by telephone or video to participate in in-person medical consultation if needed. All the clinical sections conduct weekly interdisciplinary team meetings to ensure that frail and/or complex patients have an effective, coordinated, and well-communicated plan of care. The department has also developed electronic support materials aimed at patients with cancer, caregivers, and clinicians in this challenging time.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The safety of patients and clinical trials staff remains paramount. We thus have shifted to a dual-team model, similar to that described for the clinical treatment teams in which half the research staff work in person and half work remotely in 2-week periods. Staff who do not need to be patient facing work exclusively remotely. Each disease section reviewed its respective clinical trial portfolios, keeping in mind that clinical trials that afforded opportunities for treatments otherwise not available would be prioritized. Registry, specimen collection, and other nonurgent patient treatment studies have been temporarily suspended to avoid added patient and staff exposure. Every attempt is made to adhere to clinical trial protocols, but when patient safety dictates variation from protocol, the deviation is reported accordingly.

In summary, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has created a complex set of management problems for patients with cancer in which patients, caregivers, and staff are potentially placed at increased risk. Protection for all participants is the hallmark of successful approaches to the situation, accompanied by social distancing, careful review of the aims and urgency of treatment, extensive use of virtual consultation, and modification of therapeutic approaches to reduce patient-facing contact whenever appropriate and safe. To make this more acceptable for patients and staff, meticulous strategies of communication are essential. We have summarized the approach taken in a large, multisite, multidisciplinary cancer center to prioritize quality and safety of care.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Derek Raghavan, Edward S. Kim, S. Jean Chai, Kevin Plate, Edward Copelan, Stuart Burri, Jubilee Brown, Laura Musselwhite

Administrative support: Derek Raghavan, Kevin Plate

Collection and assembly of data: Derek Raghavan, Edward S. Kim, T. Declan Walsh, Jubilee Brown, Laura Musselwhite

Data analysis and interpretation: Derek Raghavan, Edward S. Kim, S. Jean Chai, Jubilee Brown, Laura Musselwhite

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Levine Cancer Institute Approach to Pandemic Care of Patients With Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Derek Raghavan

Consulting or Advisory Role: Gerson Lehrman Group, Caris Life Sciences (Inst) Uncompensated relationship, and ceased in May 2018

Edward S. Kim

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Merck, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Genentech

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Merck, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Genentech

Research Funding: Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Ignyta, Genentech, Roche

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Roche, Pfizer, Merck

S.Jean Chai

Consulting or Advisory Role: Cardinal Health

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Cardinal Health

T. Declan Walsh

Leadership: Nualtra

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Nualtra

Research Funding: Nualtra

Stuart Burri

Employment: Southeast Radiation Oncology Group

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Southeast Radiation Oncology Group, Radiation Oncology Centers of the Carolinas

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Novocure

Jubilee Brown

Honoraria: Clovis Oncology, Tesaro

Consulting or Advisory Role: Clovis Oncology, Tesaro, Olympus

Research Funding: Tesaro, Genentech

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Olympus

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: Estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. [epub ahead of print on March 10, 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. [epub ahead of print on March 25, 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint GI society message: COVID-19 clinical insights for our community of gastroenterologists and gastroenterology care providers http://www.asge.org/home/joint-gi-society-message-covid-19