Abstract

Stroke survivors carry a high risk of recurrence. Antithrombotic medications are paramount for secondary prevention and thus crucial to reduce the overall stroke burden. Appropriate antithrombotic agent selection should be based on the best understanding of the physiopathological mechanism that led to the initial ischemic injury. Antiplatelet therapy is preferred for lesions characterized by atherosclerosis and endothelial injury, whereas anticoagulant agents are favored for cardiogenic embolism and highly thrombophilic conditions. Large randomized controlled trials have provided new data to support recommendations for the evidence-based use of antiplatelet agents and anticoagulant agents after stroke. In this review, the authors cover recent trials that have altered clinical practice, cite systematic reviews and meta-analyses, review evidence-based recommendations based on older landmark trials, and indicate where there are still evidence-gaps and new trials being conducted.

Keywords: anticoagulants, antiplatelets, antithrombotics, ischemic stroke, secondary prevention

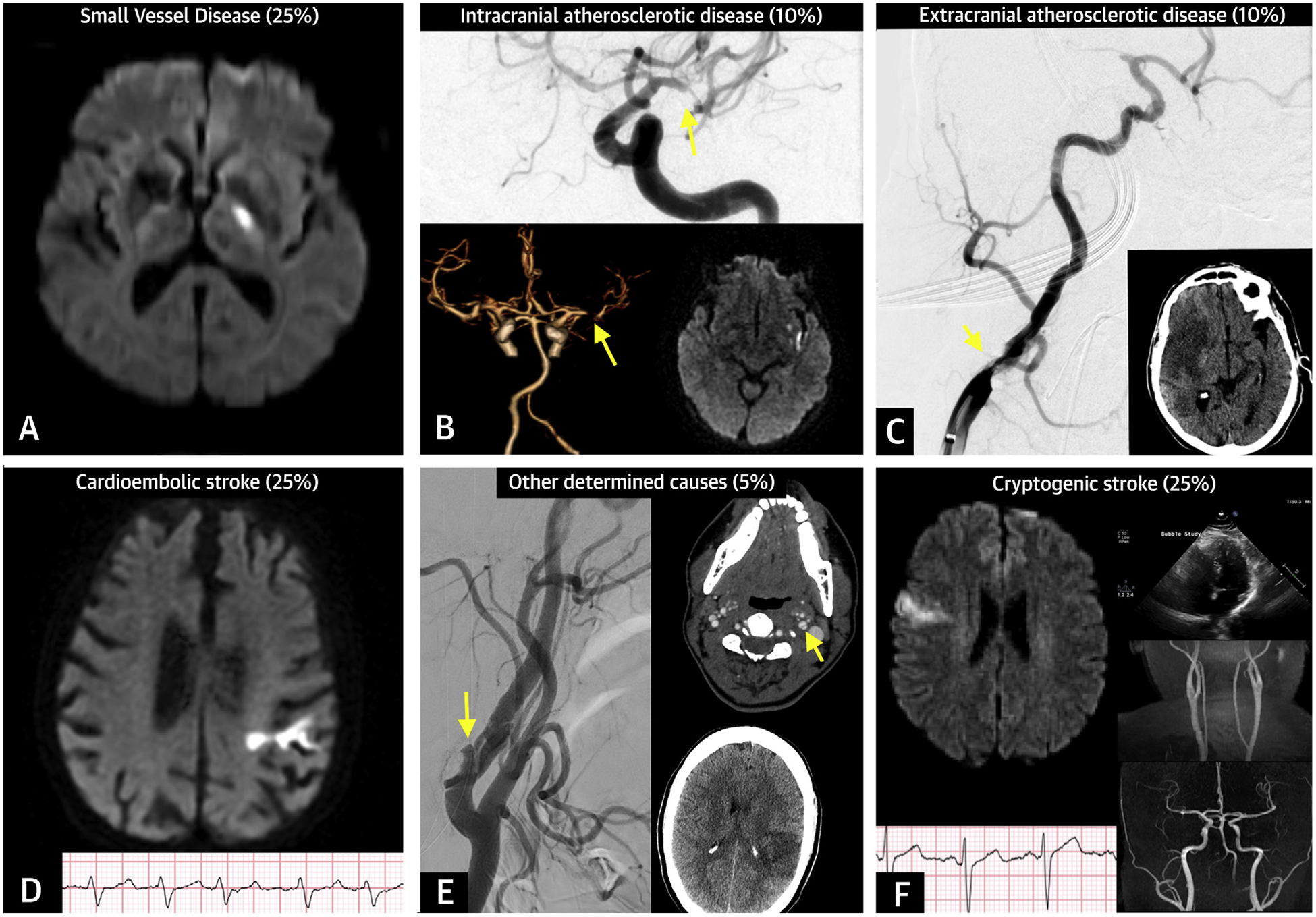

Tremendous strides have been made in the management of cerebrovascular disorders. Ischemic stroke is more challenging to treat than coronary artery disease due to the variety of mechanisms that can lead to cerebral ischemia. Stroke subtypes include: 25% due to cardioembolism; 10% due to extracranial atherosclerotic disease; 10% due to intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAD); 25% due to small vessel disease (SVD); 5% from other determined causes; and 25%, labeled cryptogenic, without a definite understanding of the cause (Figure 1). Some of the latter have been classified as embolic strokes of undetermined source (ESUS) where the cause could be an under-recognized cardiac source or a nonstenosing arterial lesion (1). Diagnostic imaging of the brain, arteries, and heart have enhanced our ability to identify the most likely mechanism of injury.

FIGURE 1. Prevalence of Stroke Subtypes.

(A) Small vessel disease: brain magnetic resonance imaging showing an acute left internal capsule lacunar infarct (<20 mm) on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequence. (B) Intracranial atherosclerotic disease: cerebral angiogram and computed tomography angiogram showing left middle cerebral artery stenosis (>90%) (arrow) associated with acute infarct on left insula. (C) Extracranial atherosclerotic disease: cerebral angiogram showing right middle cerebral artery occlusion associated with severe stenosis of ipsilateral cervical internal carotid (arrow). (D) Cardioembolic stroke: left frontal cortical infarct on DWI sequence associated with atrial fibrillation on electrocardiogram. (E) Other determined causes of stroke: dissection of the left cervical internal carotid artery (arrows) associated with ischemic stroke on the left frontal lobe. (F) Cryptogenic stroke: right frontal cortical infarct on DWI sequence with no definite cardioembolic source based on cardiac monitoring or echocardiography, and no evidence of large-artery steno-occlusive disease.

The immediate period after stroke has been the target of time-sensitive therapies including thrombolysis and endovascular thrombectomy. Beyond this stage, therapeutic goals are to reduce the risk of stroke recurrence and prevent medical complications. The pattern of recurrence varies by stroke subtype, being the highest for large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA) in the early phase, whereas for cardioembolic strokes, the long-term risk is steadily high and is associated with higher mortality (2,3). In addition, particular mechanisms of injury such as SVD presenting with capsular warning syndrome are characterized by early neurological deterioration (4). Antithrombotic agents contribute to preventing recurrent stroke and vascular events after an ischemic stroke.

In this paper, we review the latest evidence for the use of antithrombotic agents in patients who have symptomatic cerebrovascular disease. We organized our discussion on the basis of the likely etiology of the initial stroke. Our aims were to cover recent trials that have altered clinical practice, cite systematic reviews and meta-analyses, review evidence-based recommendations, and indicate where there are still unanswered questions and new trials being conducted.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING SELECTION AMONG ANTITHROMBOTIC AGENTS

Antithrombotic agents are part of a comprehensive risk factor management strategy to prevent short- and long-term recurrence after stroke and include anticoagulant agents and platelet antiaggregant agents.

After noncardioembolic stroke, antiplatelet agents are the therapy of choice to reduce recurrent stroke (Table 1). Anticoagulation has not been found to be superior to antiplatelet agents and increases the risk of hemorrhagic complications (5). Aspirin is widely available and has well-documented efficacy in preventing stroke recurrence (6–8). Dipyridamole is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor often used in combination with aspirin that has been demonstrated to reduce stroke recurrence when compared with placebo (9). In addition, a meta-analysis found that aspirin-dipyridamole was superior to aspirin alone in preventing major vascular events after stroke (10). Notably, aspirin-dipyridamole has a high discontinuation rate, largely due to headaches (9,10). Clopidogrel inhibits the adenosine diphosphate receptor resulting in platelet antiaggregation. Clopidogrel has not been compared with placebo in secondary stroke prevention. Two large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated benefits of clopidogrel when compared with aspirin, and the similarity between clopidogrel and the combination of aspirin and dipyridamole (11,12). For long-term prevention of stroke recurrence, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin plus clopidogrel has not demonstrated benefit and led to significantly increased hemorrhagic complications (13–15); whereas 2 recent RCTs showed DAPT is beneficial in the short term after transient ischemic attack (TIA) and minor ischemic stroke (see the following text) (16,17).

TABLE 1.

Major Trials in Long-Term Secondary Prevention After Noncardioembolic Stroke

| Study (Ref. #) | Population | N | Intervention | Follow-Up | Primary Endpoint | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IST (7) | Ischemic stroke with onset <48 h | 19,435 | Aspirin vs. avoid aspirin | 6 months | Mortality at 14 days Mortality, dependence, or incomplete recovery at 6 months |

9.0% vs. 9.4% 62.2% vs. 63.5% |

NS ARR = 1.3% NNT = 77 |

| CAST (8) | Ischemic stroke with onset <48 h | 21,106 | Aspirin vs. placebo | 4 weeks | Death or nonfatal stroke at 4 weeks | 5.3% vs. 5.9% | ARR = 0.7% NNT = 153 |

| ATT Collaboration meta-analyses (6) | Previous stroke or TIA | 6,170 (10 trials) | Aspirin vs. control | — | Serious vascular events (stroke, MI, or vascular death) Any stroke |

6.78%/yr vs. 8.06%/yr 3.9%/yr vs. 4.7%/yr |

ARR = 1.3% NNT = 78 ARR = 1.7% NNT = 128 |

| WARSS (5) | Ischemic stroke within 30 days | 2,206 | Warfarin vs. aspirin | 2 yrs | Death and recurrent ischemic strokes | 17.8% vs. 16% | NS |

| ESPS-2 (9) | Ischemic stroke or TIA in last 3 months | 6,602 | Aspirin vs. placebo Dipyridamole vs. placebo Aspirin-dipyridamole vs. placebo |

2 yrs | Stroke recurrence | 12.5% vs. 15.2% 12.8% vs. 15.2% 9.5% vs. 15.2% |

ARR = 2.7% NNT = 37 ARR = 2.4% NNT = 42 ARR = 5.7% NNT = 18 |

| ESPRIT (10) | Minor ischemic stroke or TIA in prior 6 months | 2,739 | Aspirin-dipyridamole vs. aspirin | 3.5 yrs | Vascular mortality, nonfatal stroke, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal major bleeding | 12.7% vs. 15.7% | ARR = 3% NNT = 33 |

| CAPRIE (11) | Subgroup: ischemic stroke onset ≥1 week and ≥6 months | 6,431 | Clopidogrel vs. aspirin | 1.9 yrs | Ischemic stroke, MI, or vascular death | 7.2% vs. 7.7% | NS |

| PRoFESS (12) | Ischemic stroke in prior 90 days | 20,332 | Aspirin-dipyridamole vs. clopidogrel | 2.5 yrs | Stroke recurrence | 9.0% vs. 8.8% | NS |

| MATCH (13) | Ischemic stroke within 3 months and ≥1 additional cardiovascular risk factor | 7,599 | Aspirin/clopidogrel vs. clopidogrel | 18 months | Ischemic stroke, MI, vascular death, or hospitalization for acute ischemic event | 16% vs. 17% | NS |

| SPS3 (14) | Lacunar stroke in prior 6 months | 3,020 | Aspirin/clopidogrel vs. aspirin/placebo | 3.4 yrs | Incident stroke | 2.7%/yr vs. 2.5%/yr | NS |

| CHARISMA (15) | Subgroup: diagnosis of stroke or TIA | 4,320 | Clopidogrel/aspirin vs. placebo/aspirin | 28 months | Stroke recurrence | 4.8% vs. 6% | NS |

| CSPS-2 (18) | Ischemic stroke in previous 26 weeks | 2,757 | Cilostazol vs. aspirin | 29 months | Stroke recurrence | 6.1% vs. 8.9% | ARR = 2.9% NNT = 36 |

| PLATO (19) | Subgroup: patients with acute coronary syndrome with history of stroke or TIA | 1,152 | Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel | 1 yr | Stroke, MI, vascular death | 19% vs. 20.8% | NS |

ARR = absolute risk reduction; ATT = Antithrombotic Trialists; CAPRIE = Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events; CAST = Chinese Acute Stroke Trial; CHARISMA = Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management and Avoidance; CSPS-2 = Cilostazol for prevention of secondary stroke; ESPRIT = European/Australasian Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischemia Trial; ESPS-2 = European Stroke Prevention Study-2; IST = International Stroke Trial; MATCH = Management of Atherothrombosis With Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients; MI = myocardial infarctions; NNT = number needed to treat; NS = nonsignificant; PLATO = Platelet inhibition and patient outcomes; PRoFESS = Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes; SPS3 = Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes; TIA = transient ischemic attack; WARSS = Warfarin versus Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study.

Cilostazol is a phosphodiesterase-3 inhibitor with vasodilatory as well as antiplatelet effects. A Japanese RCT showed that cilostazol was noninferior to aspirin in preventing stroke recurrence after noncardioembolic stroke and was associated with fewer hemorrhagic complications (18). Similar to clopidogrel, ticagrelor acts on the platelet P2Y12 pathway, but ticagrelor reversibly binds to the P2Y12 receptor and is direct acting, whereas clopidogrel requires metabolic activation. In patients with history of stroke or TIA, ticagrelor was not different than clopidogrel in preventing vascular events (19). Other antiplatelet agents are almost never used due to their adverse effect profile or unproven efficacy.

Antiplatelet selection should be based on known efficacy, safety, cost, and patient preference. Current guidelines recommend aspirin monotherapy, the combination aspirin-dipyridamole, or clopidogrel after noncardioembolic stroke. Clopidogrel is recommended in the setting of aspirin allergy (20). Antithrombotic agent selection for patients who have stroke while on appropriate therapy has been poorly studied. On the basis of platelet function testing, one-third of patients on aspirin or clopidogrel are deemed to be non-responders. However, therapy modification in this subset of patients resulted in no benefit (21). More recently, a systematic review showed that the addition of or a switch to another antiplatelet agent in patients with “aspirin failure” was associated with fewer vascular events (22). These results, however, require confirmation.

Cardioembolic strokes occur primarily in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), valvular heart disease, and cardiomyopathies predisposing to intracardiac thrombus formation and are prevented with anticoagulation. Vitamin K antagonists (VKA) such as warfarin have been available for almost a century and are the anticoagulant agents most commonly prescribed worldwide. The newer direct oral anticoagulant agents (DOAC) include direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) and factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban). In contrast to VKA, DOACs do not require coagulation monitoring, have no food interactions, and only few drugs interactions. The role of anticoagulant agents after cardioembolic strokes and other thrombophilic conditions is discussed in the following text.

ACUTE ISCHEMIC STROKE AND TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK

Immediately after ischemic stroke or TIA, there is a major opportunity to institute treatments that can prevent stroke recurrence. Within 48 h of an event, aspirin provides benefit compared with placebo. In 2 large RCTs that enrolled more than 40,000 patients, there was a 1.3% absolute risk reduction (ARR) in the rate of death and disability at 6 months with aspirin compared with placebo (number needed to treat [NNT] = 77) (7,8). As a result, initiation of aspirin within 48 h of an ischemic stroke is recommended.

Two recent RCTs have evaluated DAPT in acute cerebral ischemia (15,16). Conducted exclusively in China, the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients With Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events) trial included patients with high-risk TIA or minor stroke within 24 h of onset (16). Subjects in the DAPT arm received a 300-mg loading dose of clopidogrel followed by 75 mg daily for 90 days along with aspirin 75 mg daily during the first 21 days, whereas the control group received aspirin alone through 90 days. Stroke recurrence was 8.2% with DAPT compared with 11.7% with aspirin (ARR = 3.5%; NNT = 29). In a time-course analysis, stroke reduction with DAPT was primarily seen in the first 10 days, whereas the risk of any bleeding (although not statistically significant) was constant during 21 days of DAPT (23). Because stroke subtype distribution (i.e., higher prevalence of LAA), as well as the prevalence of genetic polymorphisms affecting clopidogrel metabolism, differ in China compared with other populations, there was uncertainty about generalizability to non-Chinese patients (24,25).

The POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial studied early DAPT in a broader population with mild stroke or high-risk TIA (17). Candidates for reperfusion interventions, as well as those with carotid stenosis eligible for endarterectomy were excluded. Including 10 countries, 4,881 patients were enrolled within 12 h of symptom onset. Patients assigned to DAPT received a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel, followed by 75 mg daily. All patients received aspirin (50 to 325 mg). During 90-day follow-up, the primary endpoint of stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or vascular death occurred in 5% of patients receiving DAPT and in 6.5% receiving aspirin alone (ARR = 1.5%; NNT = 66). Ischemic stroke was also reduced among patients receiving DAPT (4.6% vs. 6.3%; ARR = 1.7%; NNT = 59). Major hemorrhage was increased with DAPT compared with aspirin alone (0.9% vs. 0.4%; p = 0.02), but there was no increase in symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). The event rate was lower than expected, particularly among patients with TIA, which could be partially explained by the inclusion of mimics and low-risk patients (17).

Different time windows were analyzed in the POINT trial, and a divergent pattern emerged for ischemic and hemorrhagic outcomes. Prevention of ischemic events on DAPT was statistically significant at both 7 days and 30 days. However, major bleeding was not different at 7 days but significantly increased in days 8 to 90. Given the finding from the CHANCE trial that 3 weeks of DAPT reduced stroke without an increase in major hemorrhagic events, some have argued that 3 weeks represents the “sweet spot” to optimize benefits and reduce risks. A recent meta-analysis also found that 3 weeks of DAPT appears to provide the optimal balance of stroke reduction and bleeding avoidance (26). More intensive antiplatelet regimen with 3 combined agents (aspirin, clopidogrel, and dipyridamole) showed no benefit over guideline-based therapy (27).

The SOCRATES (Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Treated With Aspirin or Ticagrelor and Patient Outcomes) trial enrolled 13,199 patients with high-risk TIA or mild stroke from 33 countries (28). Subjects received a 180-mg loading dose of ticagrelor (followed by 90 mg twice daily) or aspirin 300-mg loading dose (followed by 100 mg daily). Within 90 days, the endpoint of stroke, MI, or death occurred in 6.7% of patients receiving ticagrelor and 7.5% receiving aspirin (p = 0.07), and ischemic stroke occurred in 5.8% patients treated with ticagrelor and 6.7% with aspirin (p = 0.046). No difference in bleeding complications was seen among groups.

In synthesizing the recent data, short-term DAPT with aspirin plus clopidogrel initiated within 24 h is beneficial for patients with recent TIA or minor stroke (Table 2), whereas antiplatelet monotherapy is recommended after moderate-to-severe strokes due to the potential risk of hemorrhagic transformation. The role of ticagrelor remains the subject of an ongoing RCT (29), which aims to compare ticagrelor combined with aspirin versus aspirin alone in preventing stroke and death after a mild ischemic stroke or high-risk TIA.

TABLE 2.

Suggested Recommendations on Antithrombotic Therapies for Secondary Prevention in Patients With Common Causes of Cerebral Ischemia

| Recommendation | Class* | Level† | Relevant Studies (Ref. #) | Intervention | Follow-Up | Endpoint | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute minor stroke or TIA | DAPT within 24 h of onset and continuation for 21 days‡ | II | A | CHANCE (16) POINT (17) |

Aspirin/clopidogrel vs. aspirin Aspirin/clopidogrel vs. aspirin |

90 days 90 days |

Stroke recurrence Ischemic stroke, MI, or vascular death |

8.2% vs. 11.7% 5.0% vs. 6.5% |

ARR = 3.5% NNT = 29 ARR = 1.7% NNT = 59 |

| SVD | Long-term DAPT is not recommended§ | III | A | SPS3 (14) | Aspirin/clopidogrel vs. aspirin/placebo | 3.4 yrs | Incident stroke Safety: major hemorrhages |

2.5%/yr vs. 2.7%/yr 2.1%/yr vs. 1.1%/yr |

NS ARI = 3.2% NNH = 31 |

| ICAD | Anticoagulation is not recommended over antiplatelet therapy§ DAPT for 90 days in severe stenosis (70%-99%) might be reasonable§ |

III IIb |

A B |

WASID (32) SAMMPRIS (33) |

Warfarin vs. aspirin PTAS plus aggressive medical therapy vs. aggressive medical therapy only |

36 months 32 months |

Ischemic stroke, ICH, or vascular death Safety: death Stoke or death |

21.8% vs. 22.1% 9.7% vs. 4.3% 23% vs. 15% |

NS ARI = 5.4% NNH = 19 ARI = 8.2% NNH = 12 |

| ECAD | Low-dose aspirin is recommended before CEA and may be continued indefinitely DAPT for at least 30 days after CAS‖ |

I I |

A C |

ACE (48) McKevitt et al.(52) |

Low-dose (81–325 mg) vs. high-dose (650–1,300 mg) aspirin Aspirin/clopidogrel vs. 24 h heparin plus aspirin |

3 months 30 days |

Stroke, MI, or death Neurological complications |

6.2% vs. 8.4% 0% vs. 25% |

ARR = 2.1% NNT = 46 ARR = 25% NNT = 4 |

| AF | Long-term anticoagulation for AF¶ DOACs are favored over warfarin in DOAC-eligible patients¶ |

I I |

A A |

EAFT (62) Ntaios 2017 et al. (meta-analysis) (69) |

Anticoagulation vs. placebo DOAC vs. warfarin |

2.3 yrs 1.8 to 2.8 yrs |

Stroke, MI, systemic embolism, or vascular death Stroke or systemic embolism Safety: intracranial hemorrhage |

8%/yr vs. 17%/yr 4.9% vs. 5.7% 1.0% vs. 1.9% |

ARR = 12.2% NNT = 8 ARR = 0.8%; NNT = 127 ARR = 0.9% NNT = 133 |

| ESUS | DOACs are not recommended over antiplatelets‡ | III | A | NAVIGATE-ESUS (80) RESPECT-ESUS (81) |

Rivaroxaban vs. aspirin Dabigatran vs. aspirin |

11 months 19 months |

Stroke or systemic embolism Safety: major bleeding Stroke recurrence Safety: major bleeding |

5.1%/yr vs. 4.8%/yr 1.8%/yr vs. 0.7%/yr 4.1%/yr vs. 4.8%/yr 1.7%/yr vs. 1.4%/yr |

NS ARI = 1.1% NNH = 92 NS NS |

Class of recommendation: I = benefit outweigh risk (strong); IIa = benefit outweigh risk (moderate); IIb = benefit might outweigh risk (weak); and III = no benefit or harm.

Level of Evidence: A = high-quality evidence from meta-analyses or high-quality randomized controlled trials; B = moderate-quality evidence, data from single randomized control trial or nonrandomized studies; and C = limited data or expert opinion.

Our interpretation based on new evidence released after the publication of pertinent guidelines.

2014 Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (20).

2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease (50).

2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation (61).

ACE = Aspirin and Carotid Endarterectomy Trial; AF = atrial fibrillation; ARI = absolute risk increase; ARR = absolute risk reduction; CAS = carotid artery stenting; CEA = carotid endarterectomy; CHANCE = Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients With Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events; DOACs = direct oral anticoagulant agents; DAPT = dual antiplatelet therapy; EAFT = European Atrial Fibrillation Trial; ECAD = extracranial atherosclerotic disease; ESUS = embolic stroke of undetermined source; ICAD = Intracranial atherosclerotic disease; NAVIGATE-ESUS = New Approach Rivaroxaban Inhibition of Factor Xa in a Global Trial versus Aspirin to Prevent Embolism in Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source; NNH = number needed to harm; POINT = Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke; PTAS = percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting; RESPECT-ESUS = Randomized, Double-blind, Evaluation in Secondary Stroke Prevention Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of the Oral Thrombin Inhibitor Dabigatran versus Aspirin in Patients with Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source; SAMMPRIS = Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent stroke in Intracranial Stenosis; SPS3 = Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes; WASID = Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

LARGE-ARTERY ATHEROSCLEROSIS

INTRACRANIAL ATHEROSCLEROTIC DISEASE.

ICAD is more prevalent among Asians, Blacks, and Hispanics, thus is likely the most common vascular lesion in stroke patients worldwide (30). Even with intensive medical management, individuals with ICAD and high-grade stenosis have a 30-day and 1-year risk of stroke recurrence of 5% and 15%, respectively (31).

Anticoagulation was found not to be safe in symptomatic ICAD. The WASID (Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease) trial compared aspirin 1,300 mg daily versus warfarin in individuals with stroke or TIA within 90 days due to ICAD (50% to 99% stenosis) (32). The study was stopped early due to excess major hemorrhage (8.3% vs. 3.2%; p = 0.01) and death (9.7% vs. 4.3%; p = 0.02) in the warfarin arm. With 569 participants followed for 1.8 years, the primary endpoint of ischemic stroke, brain hemorrhage and vascular death occurred in 22% in both groups.

The SAMMPRIS (Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis) trial was designed to assess endovascular therapy in symptomatic ICAD (31). Individuals with ICAD (70% to 99% stenosis) within 30 days from an index stroke or TIA were randomized to best medical therapy with or without stenting (Wingspan system, Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, California; formerly Boston Scientific Neurovascular). Best medical therapy included DAPT with aspirin and clopidogrel for 90 days followed by aspirin alone, aggressive management of blood pressure, lipids and other vascular risk factors, and a lifestyle modification program. The study was discontinued due to a higher 30-day rate of stroke and death in the endovascular arm (14.7%) compared with the medical arm (5.8%) (p = 0.002). The primary outcome of stroke and death remained better for the medical arm during prolonged follow-up (15% vs. 23%; p = 0.025) (33).

Better outcomes in the medical arm of the SAMMPRIS trial compared with historical controls have been attributed to statins, aggressive risk factor control, and the use of DAPT (34). Therefore, data from the SAMMPRIS trial has been extrapolated to support the use of DAPT in ICAD. A subanalysis of the CHANCE trial showed no significant benefit in 90-day stroke reduction among ICAD patients treated with DAPT compared with aspirin alone (11.3% vs. 13.6%; p = 0.44) (35). However, these results were underpowered and could be influenced by clopidogrel resistance as mentioned in the preceding text. Another study that supports DAPT for patients with LAA found a significant decrease in microembolic signals at 7 days with DAPT compared with aspirin alone (36). To date, no RCT focused on ICAD has compared antiplatelet monotherapy with DAPT.

The TOSS (Trial of Cilostazol in Symptomatic Intracranial Arterial Stenosis) trial (37) randomized 135 participants to aspirin plus cilostazol versus aspirin alone within 2 weeks of their index event and found that ICAD progression at 6 months occurred in 7% on combined therapy versus 29% on aspirin alone (p = 0.008). A larger study comparing cilostazol plus aspirin versus clopidogrel plus aspirin in 457 individuals found no difference in ICAD progression at 7 months (9.3% vs. 15.5%; p = 0.09) or recurrent stroke (4.7% vs. 2.6%; p = 0.32) (38). Recent results from the CSPS (Cilostazol Stroke Prevention Study for Antiplatelet Combination) trial reported lower stroke recurrence among patients with LAA (or at least 2 risk factors for atherosclerosis) when treated with cilostazol plus aspirin or clopidogrel compared with aspirin or clopidogrel alone (2.2% vs. 4.5%; ARR = 2.3%), without an increase in hemorrhagic events. The benefit of DAPT with cilostazol was maintained in the ICAD subgroup (4% vs. 9.2%; ARR = 5.2%). However, this open-label study was stopped at 47% of planned recruitment and enrolled only Japanese participants (39).

Ticagrelor has not been studied specifically in ICAD, but amongst SOCRATES trial participants with proximal atherosclerotic disease, ticagrelor was superior to aspirin in preventing stroke, MI, or death at 90 days (6.7% vs. 9.6%; ARR = 2.9%) (40). For Asian participants, among whom ICAD is common, events recurrence was lower with ticagrelor than aspirin(9.7% vs. 11.6%; ARR = 1.9%) (41).

For TIA or stroke due to ICAD, RCTs data supports current recommendations of the use of antiplatelet therapy, high-intensity statins, good blood pressure control, and exercise (20). DAPT beyond the acute phase in ICAD remains investigational. Endovascular approaches should be reserved for those with recurrent events despite optimal medical management.

EXTRACRANIAL CAROTID DISEASE.

Extracranial carotid disease is responsible for 10% to 15% of all ischemic strokes. Patients with stroke, TIA, and amaurosis fugax caused by carotid disease often have recurrent symptoms, with the highest risk in the first 2 weeks after the index event, and therefore, prompt revascularization should be considered. In data largely from pre-statin era, 3 RCTs revealed significant benefit of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) over medical management for symptomatic stenosis of 70% to 99% (ARR = 16% at 5 years; NNT = 6.3), a lower benefit for 50% to 69% stenosis (ARR = 4.6% at 5 years; NNT = 22), and no benefit or harm for <50% stenosis (42). Carotid artery stenting (CAS) has emerged as an alternative to CEA. A pooled analysis of 3 RCTs comparing CEA with CAS in symptomatic carotid stenosis showed that CEA was safer than CAS (30-day rate of stroke or death: 4.4% vs. 7.7%; p < 0.001). However, the short-term outcomes were similar among patients younger than 70 years of age (30-day rate of stroke or death: CEA 4.5% vs. CAS5.1%) (43). More recently, the long-term follow-up of the ICSS (International Carotid Stenting Study) showed similar cumulative 5-year risk of fatal or disabling stroke between CEA and CAS (6.5% vs.6.4%) (44).

The benefit from CEA appears to diminish after 2 weeks (NNT = 5 within 2 weeks vs. NNT = 125 after 12 weeks) (45), but carotid intervention within 48 h is associated with greater periprocedural ipsilateral stroke and death (46). Therefore, it is critical to institute appropriate medical therapy until revascularization can be performed and in those not eligible for intervention to prevent recurrent carotid-related stroke and decrease procedural vascular complications.

Aspirin use before CEA is now standard of care. A RCT comparing aspirin versus placebo before CEA found a significant reduction in stroke and death without an increase in pre-operative bleeding (47). The ACE (Aspirin and Carotid Endarterectomy) trial compared low-dose (81 mg and 325 mg) to high-dose aspirin (650 mg and 1,300 mg) in the periprocedural period and found a lower risk of stroke, MI, or death with lower doses (3.2% vs. 8.2%; p = 0.002) (48). DAPT before CEA has been traditionally avoided because of the increased risk of surgical bleeding. A large registry that included almost 7,000 patients who had CEAs for symptomatic disease showed that DAPT was not associated with a lower risk of perioperative stroke and death (1.3% vs. 1.5%; p = 0.7) but had a higher risk of neck bleeding requiring surgical exploration (1.5% vs. 0.6%; p = 0.02) (49).

The recommendation to use DAPT before and for at least 30 days after CAS (50,51) is largely based on the coronary published reports. A small trial comparing antithrombotic agents in CAS showed higher neurological complications with aspirin plus 24 h of heparin compared with aspirin plus clopidogrel (52).

Beyond the procedural period and among those not eligible for intervention, antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, or aspirin-dipyridamole is recommended indefinitely after CEA and CAS (50,51). Ticagrelor needs further investigation as an option for those with atherosclerotic disease (40).

EXTRACRANIAL VERTEBRAL DISEASE.

Among posterior circulation strokes, 10% to 20% of patients have proximal atherosclerotic extracranial disease (53). The same medical management recommended for carotid disease is followed for extracranial vertebral disease (50,51). Two trials failed to show superiority of stenting over medical management (54,55). A recent trial, unfortunately discontinued due to funding issues, showed that stenting was safe and suggested a trend toward better outcomes (56). To date, no data support endovascular intervention for vertebral artery disease.

AORTIC ARCH ATHEROSCLEROTIC DISEASE.

Seminal studies have identified an association between aortic arch atherosclerosis and ischemic stroke, particularly when large plaques (>4 mm) are present (57,58). Compared with other stroke mechanisms, there are relatively scarce data on antithrombotic treatment for secondary prevention in arch disease.

In the observational FSAPS (French Study of Aortic Plaques in Stroke) trial, those on antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy had similar recurrent events (57). The ARCH (Aortic Arch Related Cerebral Hazard) trial (59) was specifically designed to study aortoembolism. Patients with stroke, TIA, or peripheral embolism from thoracic arch plaques >4 mm were randomized to DAPT versus warfarin. In 349 participants followed for a mean of 3.4 years, the outcome of stroke, MI, peripheral embolism, and vascular death occurred in 7.6% on DAPT and 11.3% on warfarin (p = 0.2); only vascular death was significantly more frequent in the anticoagulation group. In the SOCRATES post hoc analysis, the subgroup with known arch disease and/or carotid stenosis <50% had a lower rate of stroke, MI, or death within 90 days when treated with ticagrelor compared with aspirin (3.7% vs. 7.1%; ARR = 3.4%; p = 0.02) (60).

Therefore, the current published reports support as a Class I recommendation treating patients with aortic arch disease and stroke or TIA with antiplatelet agents (20). There is no evidence that warfarin is useful in this condition.

CARDIOGENIC EMBOLISM

ATRIAL FIBRILLATION.

Long-term anticoagulation is recommended for secondary stroke prevention in patients with AF (61) (Table 2). The EAFT (European Atrial Fibrillation Trial) was the first RCT to show this effect (62). When compared with placebo, this RCT found 8% ARR for recurrent stroke with warfarin (NNT = 12) and 2% ARR in patients receiving aspirin (NNT = 50). A meta-analysis showed that warfarin was superior to aspirin for prevention of vascular events (odds ratio: 0.55; 95% confidence interval: 0.37 to 0.82) or recurrent stroke (odds ratio: 0.36; 95% confidence interval: 0.22 to 0.58) (63). However, hemorrhagic risk was significantly increased by anticoagulation. The optimal international normalized ratio (INR) range for VKA anticoagulation is between 2.0 and 3.0 (61).

DOACs were compared with warfarin in patients with AF in 4 RCTs (64–67). In addition, 1 trial compared apixaban with aspirin in AF patients not suitable for treatment with warfarin (68). All studies comparing DOACs with warfarin had subgroups of AF patients with a prior TIA or stroke. In 20,500 patients, DOACs were associated with a marginal benefit as demonstrated by reduction of stroke and systemic embolism (ARR = 0.8%; NNT = 127), any stroke (ARR = 0.7%; NNT = 142), and intracranial hemorrhage (ARR = 0.9%; NNT = 113) over 1.8 to 2.8 years (69). Therefore, DOACs are favored over warfarin in secondary stroke prevention in patients with AF, except in those with moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis or mechanical heart valve (61). In patients with moderate-to-severe kidney disease, adjusted doses of DOACs are required, whereas in those with end-stage renal disease or requiring dialysis, warfarin is recommended instead of DOACs (61).

OTHER CARDIOEMBOLIC SOURCES.

Mitral stenosis, commonly secondary to rheumatic fever, have a high risk of systemic embolism and is frequently complicated by AF (70). In the absence of high-quality evidence, there is general consensus that anticoagulation is indicated in patients with mitral stenosis and previous stroke or AF (20,70). Patients with moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis were systematically excluded from RCTs comparing DOACs and warfarin (71); therefore, long-term VKA therapy (INR 2 to 3) is recommended (70). There are scarce data regarding the effect of other valvular heart diseases on stroke risk.

Mechanical heart valves carry a high stroke risk and life-long therapy with VKA (INR 2.3 to 3.5) is mandatory (70). Warfarin was superior to dabigatran in patients with mechanical heart valves, both in terms of efficacy and safety (72). Bioprosthetic valves have a lower risk of thromboembolism when compared with mechanical valves. For patients with mitral bioprosthetic valves, anticoagulation with VKA (INR 2 to 3) for 3 months followed by antiplatelet therapy is recommended. For aortic bioprosthetic valves, including transcatheter aortic valve bioprosthesis, antiplatelet therapy is suggested over anticoagulation (70). There are no data to support the long-term use of anticoagulation in patients with bioprosthetic valves.

The WARCEF (Warfarin Versus Aspirin in Reduced Cardiac Ejection Fraction) trial compared warfarin (INR 2.0 to 3.5) to aspirin (325 mg) among 2,305 patients with heart failure and low ejection fraction (73). The primary outcome of ischemic stroke, ICH, or death was not significantly different between groups (7.5% vs. 7.9%; p = 0.40) during a mean follow-up of 3.5 years. Patients on warfarin had a lower rate of ischemic events (0.7% vs. 1.4%; p = 0.005). However, as expected, hemorrhages were higher with warfarin (1.8% vs. 0.9%; p < 0.001). Pooled analysis of 4 studies investigating anticoagulation in patients with heart failure suggest an increased risk of bleeding counterbalanced by a marginal benefit in ischemic stroke prevention (74).

Acute MI can lead to formation of a left ventricular thrombus. Anticoagulation with heparin followed by 3 months of VKA is recommended (20). Whether DOACs have a similar efficacy and safety in this situation remains to be proven.

SMALL VESSEL DISEASE

Cerebral SVD is responsible for 25% of all ischemic strokes and the annual risk of recurrence is 2–7% (2,14). Lacunar infarcts are suspected by clinical presentation (lacunar syndromes), and confirmed on neuroimaging by the presence of small (<20 mm) subcortical infarcts located in the territory of single perforating arteries (14). A pooled analysis of RCTs found that, compared with placebo, any single antiplatelet agent after a lacunar infarct lowers the rate of any stroke (ARR = 3.5%; NNT = 29) and ischemic stroke (ARR = 5.9%; NNT = 17) (75).

Most of the trials discussed in the preceding text included diverse stroke subtypes, and results cannot be completely extrapolated to patients with SVD. Alternatively, the long-term efficacy of DAPT was specifically studied in the SPS3 (Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes) study. This study randomized 3,020 patients with magnetic resonance imaging–confirmed lacunar infarcts to receive clopidogrel 75 mg plus aspirin 325 mg daily versus the same dose of aspirin plus placebo. After a mean follow-up of 3.4 years, stroke recurrence was not reduced by DAPT (2.5% vs. 2.7%/year; p = 0.48), and the risk of hemorrhage was increased (2.1% vs. 1.1%/year; p < 0.01) (14). These findings were concordant with the MATCH trial, which found no benefit of DAPT versus clopidogrel monotherapy (Table 1). Of note, more than 50% of patients enrolled in the MATCH trial were categorized as SVD (13).

Due to its pleiotropic properties such as arteriolar vasodilation and protection of the vascular endothelium, cilostazol is potentially effective for preventing cerebral injury among patients with SVD (76,77). The ECLIPse (Effect of Cilostazol in Acute Lacunar Infarction Based on Pulsatility Index of Transcranial Doppler) trial found that cilostazol effectively decreased the pulsatility index, used as a marker of small vessel resistance (76). The safety and efficacy of cilostazol together with isosorbide mononitrate to prevent recurrent strokes and progression of SVD is under study (78).

CRYPTOGENIC STROKE

EMBOLIC STROKE OF UNDETERMINED SOURCE.

Cryptogenic strokes that are nonlacunar, have no definite cardioembolic source, and no evidence of LAA are thought to have an embolic mechanism (1). These patients are classified as ESUS, and represent 10% to 21% of all ischemic strokes (1,79). ESUS patients are relatively young (65 years of age average), and the rate of recurrence is about 5% annually.

Under the assumption of an embolic mechanism, 4 RCTs were initiated comparing anticoagulation with aspirin after ESUS. The NAVIGATE-ESUS (New Approach Rivaroxaban Inhibition of Factor-Xa in a Global Trial Versus Aspirin to Prevent Embolism in Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) trial randomized 7,213 patients to either rivaroxaban 15 mg daily or aspirin 100 mg. The trial was terminated early due to increased bleeding and the absence of an offsetting benefit in the rivaroxaban arm. The median follow-up was 11 months. The endpoint of first recurrent stroke or systemic embolism occurred in 172 patients (4.8%) on rivaroxaban and 160 patients (4.4%) on aspirin (annualized rate 5.1% vs. 4.8%; p = 0.52). The rate of major bleeding was higher for rivaroxaban compared with aspirin (annualized rate 1.8% vs. 0.7%; p < 0.001) (80). The RESPECT-ESUS (Randomized, Double-blind, Evaluation in Secondary Stroke Prevention Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of the Oral Thrombin Inhibitor Dabigatran Versus Aspirin in Patients With Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) trial randomized 5,390 patients to either dabigatran 150 mg or 110 mg twice daily depending on age and kidney function or aspirin 100 mg daily. During a mean follow-up of 19 months, recurrent stroke occurred in 117 patients (6.6%) on dabigatran and 207 patients (7.7%) on aspirin (annualized rate 4.1% vs. 4.8%; p = 0.10). The rate of major bleeding was similar in both groups (annualized rate 1.7% vs. 1.4%; p = 0.30) (81). Both trials defined major bleeding according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis: fatal bleeding, or bleeding in a critical organ, or requiring transfusion of ≥2 U, or hemoglobin fall ≥2 g/dl.

The ATTICUS (Apixaban for Treatment of Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) trial plans to randomize 500 ESUS patients to apixaban 5 mg twice daily or aspirin 100 mg daily. The primary outcome is at least 1 new ischemic lesion identified by magnetic resonance imaging at 12 months (82). The ARCADIA (Atrial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke) trial aims to compare apixaban versus aspirin in ESUS patients at high risk of cardioembolism on the basis of atrial cardiopathy detected on 12-lead electrocardiogram abnormalities, left atrium enlargement on echocardiography, or presence of elevated amino terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (83).

In conclusion, anticoagulation with DOACs has not been superior to aspirin for stroke prevention in patients with ESUS (Table 2). Whether this is also true for selected high-risk subgroups needs to be shown.

CRYPTOGENIC STROKE AND PATENT FORAMEN OVALE.

Paradoxical embolism through a patent foramen ovale (PFO) may be implicated in a proportion of patients with cryptogenic stroke (84). Secondary prevention strategies in these patients include PFO closure, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulant agents (84,85). A pooled analysis of 6 RCTs comparing PFO closure plus antiplatelet therapy versus any antithrombotic agent (antiplatelet and/or anticoagulation) showed significant stroke reduction in the closure group compared with controls (risk ratio = 0.39; p = 0.01), despite a significant risk of developing AF among patients undergoing intervention (risk ratio = 4.33; p < 0.001). All studies except 1 (86) included patients <60 years of age. A subanalysis of 2 studies comparing PFO closure to antiplatelet agents showed that the former remained more effective in preventing stroke recurrence (risk ratio = 0.36; p = 0.01) (85). Another study compared PFO closure versus anticoagulation (VKA or DOACs), and no significant benefit was found (87). Finally, 3 RCTs that compared anticoagulation versus antiplatelet agents showed fewer ischemic strokes in patients assigned to anticoagulation; however, none found a significant difference (87–89).

In summary, PFO closure plus long-term antiplatelet therapy is superior to antiplatelet agents alone in carefully selected patients (i.e., younger than 60 years of age). PFO closure and anticoagulation may have similar efficacy in preventing stroke recurrence, but available data are less robust. When PFO closure is contraindicated, the benefit of anticoagulation over antiplatelet therapy is unclear (85).

OTHER DETERMINED ETIOLOGIES

Uncommon stroke etiologies may be recognized after more extensive evaluations among patients with unrevealing initial work up. This category includes nonatherosclerotic vasculopathies (i.e., arterial dissection, vasculitis, vasospasm), hypercoagulable states, hematologic disorders, and monogenic etiologies (90). In the absence of RCTs, antiplatelet agents are generally prescribed to prevent stroke recurrence. However, management of many of these conditions is mostly based on treating the underlying disorder. Antithrombotic agents remain the pivotal treatment in some of these conditions, thus worth mentioning in the current review.

CERVICAL ARTERIAL DISSECTION.

Cervical arterial dissection (CAD) is a common cause of stroke in the young. Stroke recurrence is generally low; however, the first few weeks after presentation represents a high-risk time period (91,92). Therefore, 3 to 6 months of antithrombotic agents after diagnosis are recommended (20). A systematic review including 1,285 patients with CAD found no difference between anticoagulant agents and antiplatelet agents in the rate of death (1.2% vs. 2.6%; p = 0.2), or ischemic stroke (1.9% vs. 2%; p = 0.4) (93). The rate of ICH and extracranial hemorrhage in the anticoagulation group was 0.8% and 1.6%, respectively, compared with no hemorrhagic complications seen with antiplatelet agents.

The CADISS (Cervical Artery Dissection In Stroke Study) is the only RCT of antithrombotic agents in CAD. Patients received either antiplatelet agents or anticoagulation for 3 months after diagnosis of CAD. Ipsilateral stroke occurred in 3 of 101 patients receiving antiplatelet agents versus 1 of 96 on anticoagulation (p = 0.66). There were no deaths, but 1 patient receiving anticoagulation had a subarachnoid hemorrhage (94). The infrequency of endpoint occurrence precludes any definitive conclusion.

HYPERCOAGULABLE STATES

INHERITED THROMBOPHILIAS.

A causal relationship between stroke and inherited thrombophilias (factor V Leiden, prothrombin G20210A mutation, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T mutation, protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, and antithrombin III deficiency) remains poorly established, and routine testing is not advised (95).

Long-term anticoagulation with VKA or heparin products is recommended for patients with unprovoked venous thrombosis and an underlying thrombophilia (95,96), yet some data suggest DOACs are a suitable alternative (97,98). By contrast, published reports on antithrombotic therapy for arterial thrombosis (i.e., ischemic stroke) are limited. Current guidelines recommend that anticoagulation should be considered in the setting of recurrent cryptogenic strokes and known inherited thrombophilia (20).

ANTIPHOSPHOLIPID SYNDROME.

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS) is an antibody-induced thrombophilia characterized by recurrent thrombosis (venous and arterial) and pregnancy morbidity. In the Euro-Phospholipid Project, 20% of the patients with APLS presented with ischemic stroke and 11% with TIAs (99). Conversely, it is estimated that 1 in 5 strokes in all young patients (<50 years of age) are associated with APLS, although all ages can be affected (100).

A systematic review showed that APLS patients with previous stroke had high thrombosis recurrence despite being on antiplatelet agents or standard anticoagulation, and found that <4% of all events occurred with an INR >3.0, thus advocating for an aggressive therapeutic target in high-risk patients (101). Two RCTs with insufficient power compared high-intensity warfarin (INR 3.1 to 4.0) versus standard anticoagulation and found that high-intensity anticoagulation had no significant benefit (102,103). Finally, 1 observational study and 1 small randomized trial suggested that the combination of antiplatelet agents and anticoagulation may be more effective than either alone (104,105).

More recently, DOACs have been proposed as an alternative for APLS (106). A RCT reported no thrombosis or major bleeding in low-risk APLS patients treated with rivaroxaban, suggesting similar efficacy to warfarin (107). Various case series showed conflicting results regarding the efficacy of DOACs among patients with APLS (108). The use of DOACs in thrombotic APLS is the aim of several ongoing RCTs.

STROKE AND MALIGNANCY.

Ischemic stroke is common among cancer patients. Cancer may lead to stroke via hypercoagulability, paradoxical emboli, nonbacterial endocarditis, tumor embolization, and local tumor compression, or alternatively, by treatment-related complications such as radiation-related large-vessel arteriopathy (109).

Anticoagulation with either low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or DOACs may be recommended for cancer-associated thrombosis (110–112). The mechanism of injury as well as the overall prognosis should be considered when selecting antithrombotic therapy. The TEACH (Trial of Enoxaparin Versus Aspirin in Cancer Patients With Stroke) study showed no difference in the rates of stroke, major bleeding, and survival between enoxaparin and aspirin (113). However, results were limited by low patient enrollment mainly due to aversion to receive enoxaparin injections. The OASIS-CANCER (Optimal Anticoagulation Strategy In Stroke Related to Cancer) trial is an ongoing RCT that aims to compare the efficacy and safety of VKA, LMWH, and DOACs for prevention of recurrent stroke or systemic embolism in cancer patients.

CEREBRAL VENOUS THROMBOSIS

Although not from an arterial occlusion, ischemic or hemorrhagic infarctions may occur due to cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). On the basis of 2 RCTs, anticoagulation with heparin products is recommended for acute CVT, regardless of the presence of intracranial hemorrhage (114). LMWH has been associated with lower mortality, fewer hemorrhagic complications, and better long-term functional outcome when compared with unfractionated heparin (115,116).

After the acute phase, guidelines recommend anticoagulation with VKA for a variable period of time (3 to 12 months) (20,117). The optimal duration, as well as the effectiveness of DOACs, is uncertain. The EXCOA-CVT (Extending Oral Anticoagulation Treatment After Acute Cerebral Vein Thrombosis) trial is a RCT designed to compare the efficacy of short-term (3 to 6 months) versus long-term (12 months) anticoagulation after CVT (118). Another phase III trial is comparing dabigatran with warfarin for thrombosis prevention after CVT (119).

ANTITHROMBOTIC THERAPY AFTER INTRACRANIAL HEMORRHAGE

Antithrombotic agent–associated ICH is associated with larger hematoma volume, hematoma expansion, and worse outcomes (120). All antithrombotic agents should be discontinued at presentation, and rapid reversal of anticoagulation is recommended (Table 3) (121,122). For patients taking antiplatelet agents, routine platelet transfusion is not recommended (123). After bleeding cessation, early use of low-dose heparin is considered safe and effective in preventing deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (121).

TABLE 3.

Investigational Questions in the Use of Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients With Cerebrovascular Disease

| Investigational Question | Ongoing Trials |

|---|---|

| Acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack | |

| DAPT (ticagrelor and aspirin) after a minor ischemic stroke or TIA | THALES (NCT03354429) |

| DOACs vs. antiplatelet therapy after minor ischemic stroke or TIA | ADANCE (NCT01924325) |

| TRACE (NCT01923818) | |

| DATAS II (NCT02295826) | |

| DAPT (clopidogrel and aspirin) after mild-to-moderate ischemic stroke | ATAMIS (NCT02869009) |

| Small vessel disease | |

| Cilostazol to prevent recurrent lacunar strokes and progression of cerebral small vessel disease | LACI-2 (NCT03451591) |

| Large artery atherosclerotic disease | |

| Cilostazol plus aspirin or clopidogrel for stroke prevention of in patients with large artery atherosclerosis | CSPS (NCT01995370) |

| DORIC (NCT02983214) | |

| Cardioembolic stroke | |

| DOACs for stroke prevention in valvular heart disease and AF | DECISIVE (NCT02982850) |

| INVICTUS-ASA (NCT02832531) | |

| INVICTUS-VKA (NCT02832544) | |

| Optimal time to resume anticoagulation in patients with acute ischemic stroke and AF | OPTIMAS (NCT03759938) |

| TIMING (NCT02961348) | |

| ELAN (NCT03148457) | |

| Other determined etiologies | |

| DOACs for prevention of thromboembolisms in patients with APLS | ASTRO-APS (NCT02295475) |

| TRAPS (NCT02157272) | |

| RISAPS (NCT03684564) | |

| Optimal anticoagulation strategy for ischemic stroke related to cancer | OASIS-CANCER (NCT02743052) |

| ENCHASE (NCT03570281) | |

| Embolic stroke of undetermined source (cryptogenic stroke) | |

| DOACs for stroke prevention in patients with ESUS and high-risk of cardioembolism | ATTICUS (NCT02427126) |

| ARCADIA (NCT03192215) | |

| Cerebral venous thrombosis | |

| Efficacy and safety of a short-term (3–6 months) versus long-term (12 months) anticoagulation after CVT | EXCOA-CVT (ISRCTN25644448) |

| Dabigatran versus warfarin to prevent thrombotic events after CVT | RE-SPECT CVT (NCT02913326) |

| Antithrombotic therapy after intracranial hemorrhage | |

| Safety of restarting antithrombotic agents in patients with antithrombotic agent-related ICH | RESTART (ISRCTN71907627) |

| RESTART-FR (NCT02966119) | |

| APACHE-AF (NCT02565693) | |

| NASPAF-ICH (NCT02998905) | |

| SoSTART (NCT03153150) | |

| A3-ICH (NCT03243175) | |

| Efficacy and safety of DOACs compared with aspirin for stroke prevention in patients AF and previous ICH | NASPAF-ICH (NCT02998905) |

| Efficacy and safety of cilostazol to prevent stroke recurrence in patients with previous of ICH | PICASSO (NCT01013532) |

A3-ICH = Avoiding Anticoagulation After IntraCerebral Haemorrhage; ADANCE = Apixaban Versus Dual-antiplatelet Therapy (Clopidogrel and Aspirin) in Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events; APACHE-AF = Apixaban After Anticoagulation-associated Intracerebral Haemorrhage in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation; ARCADIA = AtRial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke; ASTRO-APS = Apixaban for Secondary Prevention of Thromboembolism Among Patients With AntiphosPholipid Syndrome; ATAMIS = Antiplatelet Therapy in Acute Mild-Moderate Ischemic Stroke; ATTICUS = Apixaban for Treatment of Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source; CSPS = Cilostazol Stroke Prevention Study for Antiplatelet Combination; CVT = cerebral venous thrombosis; DATAS II = Dabigatran Following Transient Ischemic Attack and Minor Stroke; DECISIVE = Dabigatran Versus Conventional Treatment for Prevention of Silent Cerebral Infarct in Atrial Fibrillation Associated With Valvular Disease; DORIC = Diabetic Artery Obstruction: is it Possible to Reduce Ischemic Events With Cilostazol?; ELAN = Early Versus Late Initiation of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Post-ischaemic Stroke Patients With Atrial fibrillatioN (ELAN): an International, Multicentre, Randomised-controlled, Two-arm, Assessor-blinded Trial; ENCHASE = Edoxaban for the Treatment of Coagulopathy in Patients With Active Cancer and Acute Ischemic Stroke: a Pilot Study; EXCOA-CVT = the benefit of EXtending oral antiCOAgulation treatment after acute Cerebral Vein Thrombosis; INVICTUS-ASA = INVestIgation of rheumatiC AF Treatment Using Vitamin K Antagonists, Rivaroxaban or Aspirin Studies, Superiority; INVICTUS-VKA = INVestIgation of rheumatiC AF Treatment Using Vitamin K Antagonists, Rivaroxaban or Aspirin Studies, Non-Inferiority; LACI-2 = LACunar Intervention Trial-2; NASPAF-ICH = NOACs for Stroke Prevention in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Previous ICH; OASIS-CANCER = Anticoagulation in Cancer Related Stroke; OPTIMAS = OPtimal TIMing of Anticoagulation After Acute Ischaemic Stroke: a Randomised Controlled Trial; PICASSO = PreventIon of CArdiovascular Events in iSchemic Stroke Patients With High Risk of Cerebral HemOrrhage; RE-SPECT CVT = A Clinical Trial Comparing Efficacy and Safety of Dabigatran Etexilate With Warfarin in Patients With Cerebral Venous and Dural Sinus Thrombosis; RESTART = REstart or STop Antithrombotics Randomised Trial; RESTART-FR = REstart or STop Antithrombotic Randomised Trial in France; RISAPS = RIvaroxaban for Stroke Patients With AntiPhospholipid Syndrome; SoSTART = Start or STop Anticoagulants Randomised Trial; THALES = Acute STroke or Transient IscHaemic Attack Treated With TicAgreLor and ASA for PrEvention of Stroke and Death; TIMING = TIMING of Oral Anticoagulant Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke With Atrial Fibrillation; TRACE = Treatment of Rivaroxaban Versus Aspirin for Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events; TRAPS = Rivaroxaban in Thrombotic Antiphospholipid Syndrome other abbreviations as in Table 2.

The safety of restarting antithrombotic agents after ICH remains unclear. Observational studies suggest that antiplatelet resumption does not carry a major hazard (124–126). A single-center study found that aspirin use was associated with ICH recurrence among patients with lobar ICH, thus exposing the higher risk of platelet inhibition among patients with ICH associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (127).

A decision analysis model showed that restarting VKA in patients with AF after a lobar ICH was associated with lower quality-adjusted life expectancy, whereas the difference in patients with deep ICH was minimal (128). A joint analysis of 3 observational studies found that anticoagulation resumption after ICH was associated with decreased mortality and better functional outcome, regardless of hematoma location (129). A systematic review evaluated anticoagulation resumption among 5,306 ICH patients with AF, prosthetic heart valves, previous venous thrombosis, and previous ischemic stroke. With a median time for restarting anticoagulation of 10 to 39 days, resumption was associated with lower risk of thromboembolic events (6.7% vs. 17.6%), and no significant risk of ICH recurrence (8.7% vs. 7.8%) during a mean follow-up ranged from 12 to 43 months (130). A recent meta-analysis with overlapping inclusion criteria revealed similar results (131).

In summary, restarting antithrombotic agents after ICH should be considered, particularly in high-risk thromboembolic conditions. It has been suggested that avoidance of antithrombotic agents for 2 to 4 weeks after ICH is reasonable (132). However, given the observational nature of published data, there is a lack of evidence-based recommendations. Numerous ongoing RCTs target this clinical situation. The RESTART (Restart or Stop Antithrombotics Randomised Trial) study is a multicenter RCT comparing starting versus avoiding antiplatelet drugs after a antithrombotic agent–associated ICH (133). Several other trials aim to investigate the safety of restarting anticoagulation in patients with AF after a spontaneous ICH. The chief investigators of these RCTs have created the COCROACH (Collaboration of Controlled Randomized Trials of Oral Antithrombotic Drugs After Intracranial Hemorrhage) study for a prospective pre-planned individual-patient data meta-analysis in order to maximize the power of their findings (134).

ONGOING TRIALS AND FUTURE PROSPECTS

Well-designed RCTs and meta-analysis have provided guidance on the use of antithrombotic agents for secondary prevention in common stroke subtypes such as those attributed to SVD, LAA, and AF. However, data are scarce in less common stroke etiologies. In addition, RCTs are not adequate to address many challenging situations, including the coexistence of more than 1 stroke mechanism, high bleeding risk patients, or patients who had stroke recurrence despite being on the recommended therapy. To date, many questions with respect to antithrombotic agent use among patients with cerebrovascular disease remain unanswered (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Recommendations for Oral Anticoagulant Agent Reversal in Intracranial Hemorrhage

| Anticoagulant Agent | Mechanism of Action | Reversal | Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K antagonist (warfarin) | Inhibits factors II, VII, IX, X | Administer Vitamin K 10 mg IV Clotting factor repletion: First line: 4F-PCC 25–50 U/kg Second line: FFP 10–15 ml/kg |

PT INR |

| Dabigatran | Direct thrombin inhibitor | Idracizumab 5 g IV If above not available: 4F-PCC 50 U/kg IV Consider hemodialysis |

TT ECT aPTT |

| Apixaban Rivaroxaban Edoxaban | Direct factor Xa inhibitors | Andexanet alfa 400–800 mg IV If above not available: 4F-PCC 50 U/kg IV |

PT Anti-factor Xa activity (not widely available) |

4F-PCC = 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate; aPTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; ECT = ecarin clotting time; FFP = fresh frozen plasma; INR = international normalized ratio; IV = intravenous; PT = prothrombin time; TT = thrombin time.

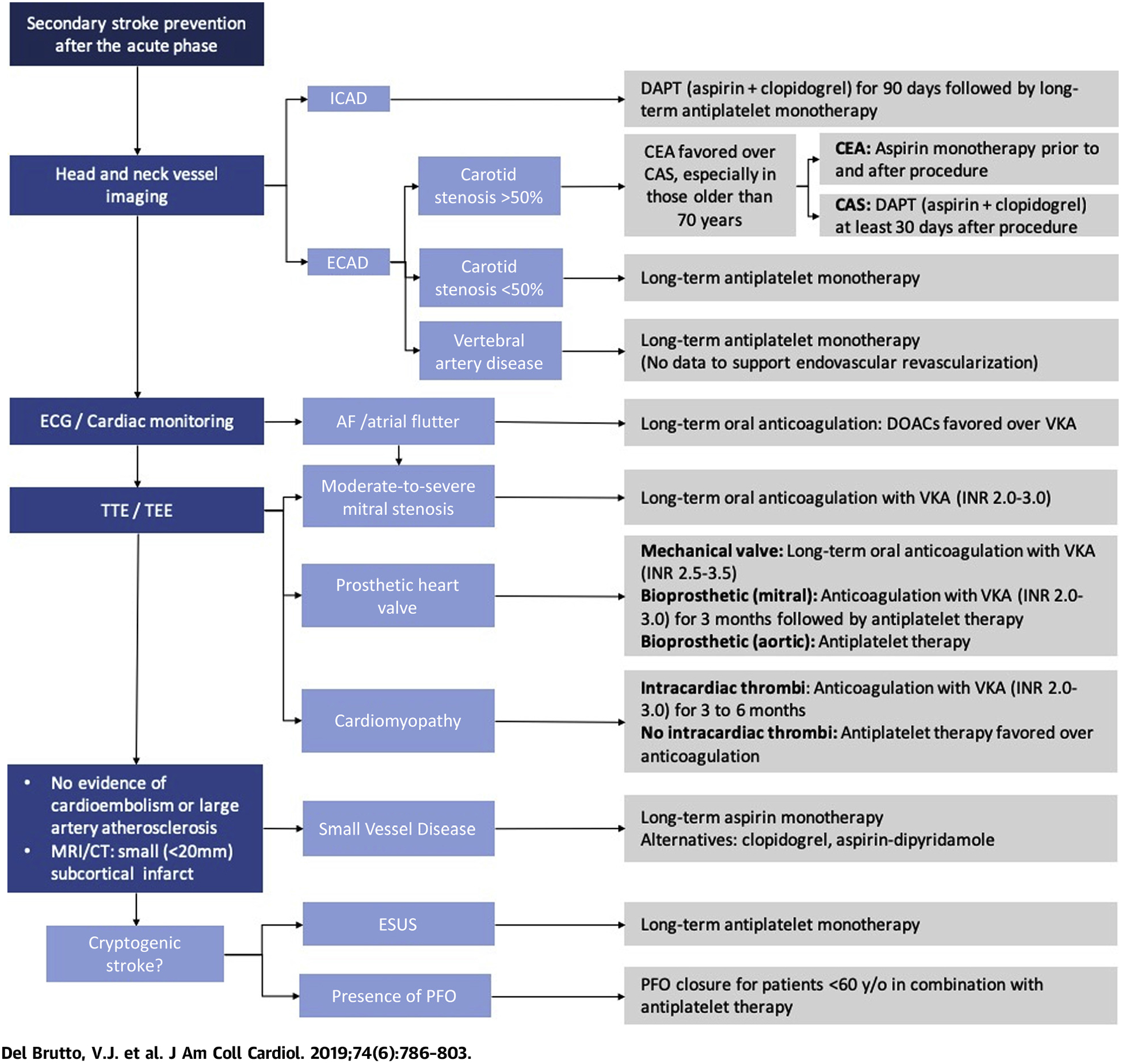

The best approach to select antithrombotic agents in patients with stroke is to first identify the likely mechanism of injury (Central Illustration). When occlusion of perforator vessels is suspected to be secondary to SVD, antiplatelet monotherapy after the acute phase is effective as long as other risk factors such as arterial hypertension are well controlled. In LAA, aggressive platelet antiaggregation is beneficial in the acute phase due to the high thrombogenicity caused by plaque rupture, whereas the use of statins and strict vascular risk factors control is more relevant in the long term to reduce atherosclerosis progression. When the thromboembolic mechanism is attributed to blood stasis such as what occurs in AF, or when inherited or acquired thrombophilias are implicated, anticoagulant agents are recommended. DOACs have emerged as a convenient alternative to VKA among patients with AF. Nevertheless, DOACs efficacy in other thrombophilic conditions predisposing to stroke remains to be proven in large RCTs.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Approach to the Use of Antithrombotic Therapy for Secondary Prevention After Ischemic Stroke.

AF = atrial fibrillation; CAS = carotid artery stenting; CEA = carotid endarterectomy; CT = computerized tomography; DAPT = dual antiplatelet therapy; DOAC = direct oral anticoagulant agents; ECAD = extracranial atherosclerotic disease; ECG = electrocardiogram; ESUS = embolic stroke of undetermined source; ICAD = intracranial atherosclerotic disease; INR = international normalized ratio; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PFO = patent foramen ovale; TEE = transesophageal echocardiogram; TTE = transthoracic echocardiogram; VKA = vitamin K antagonist.

Finally, the stroke mechanism remains undetermined in a significant proportion of patients. Two recent RCTs failed to show that DOACs are beneficial in ESUS, and suggest that covert AF is perhaps not as common as previously thought. Furthermore, these trials have led us to rethink cryptogenic stroke definition. Ongoing trials that take into account a more refined classification of patients according to high risk versus low risk of embolism may provide us a better understanding on how to evaluate and treat these patients.

In conclusion, a rational antithrombotic agent selection based on the suspected mechanism of injury is the best approach to select the appropriate therapy to prevent stroke recurrence after cerebral ischemia. Decisions should be individualized according to the risk of adverse effects such as bleeding. Vascular risk factors and high-risk behaviors must also be modified and strictly controlled. There are still many unanswered questions and several ongoing trials aim to clarify the efficacy of newer medications with alternative mechanisms of action and safer pharmacological profiles.

HIGHLIGHTS.

23% of all ischemic strokes are recurrent events.

Antithrombotic agents are part of a comprehensive risk factor management strategy to prevent stroke recurrence.

Contemporary trials guide management in common stroke causes. However, data for less common stroke etiologies are limited.

Ongoing trials aim to clarify the efficacy of novel pharmacological approaches to reduce stroke recurrence.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Chaturvedi has received grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Diener has received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to Advisory Boards, or oral presentations from Abbott, Achelios, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, CoAxia, Corimmun, Covidien, Daiichi-Sankyo, D-Pharm, Fresenius, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Johnson & Johnson, Knoll, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Medtronic, MindFrame, Neurobiological Technologies, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Paion, Parke-Davis, Pfizer, Portola, Sanofi, Schering Plough, Servier, Solvay, St. Jude, Syngis, Talecris, Thrombogenics, WebMD Global, and Wyeth; has received financial support for research projects from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck, Novartis, Janssen-Cilag, Sanofi, Syngis, and Talecris; has served as editor of Neurology International Open, Aktuelle Neurologie, and Arzneimitteltherapie, as coeditor of Cephalalgia, and on the editorial board of Lancet Neurology, Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, European Neurology, and Cerebrovascular Disorders; and has served as chair of the Treatment Guidelines Committee of the German Society of Neurology and contributed to the EHRA and ESC guidelines for the treatment of AF. Dr. Romano receives salary support (to the Department of Neurology at the University of Miami) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Multiple Program Director/Principal Investigator (PD/PI) Award (1R01NS084288). Dr. Sacco has received institutional grant support from the NIH, the American Heart Association, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Del Brutto has reported that he has no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- APLS

antiphospholipid syndrome

- ARR

absolute risk reduction

- CAD

cervical arterial dissection

- CAS

carotid artery stenting

- CEA

carotid endarterectomy

- CVT

cerebral venous thrombosis

- DAPT

dual antiplatelet therapy

- DOAC

direct oral anticoagulant agent

- ESUS

embolic stroke of undetermined source

- ICAD

intracranial atherosclerotic disease

- ICH

intracerebral hemorrhage

- INR

international normalized ratio

- LAA

large-artery atherosclerosis

- LMWH

low-molecular-weight heparin

- MI

myocardial infarction

- NNT

number needed to treat

- PFO

patent foramen ovale

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SVD

small vessel disease

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

- VKA

vitamin K antagonist

REFERENCES

- 1.Hart RG, Diener HC, Coutts SB, et al. Embolic strokes of undetermined source: the case for a new clinical construct. Lancet Neurol 2014;13: 429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petty GW, Brown RD, Whisnant JP, Sicks JD, O’Fallon WM, Wiebers DO. Ischemic stroke sub-types: a population-based study of functional outcome, survival, and recurrence. Stroke 2000; 31:1062–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Monteiro Tavares L, et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2182–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohara T, Uehara T, Sato S, et al. Small vessel occlusion is a high-risk etiology for early recurrent stroke after transient ischemic attack. Int J Stroke 2019. March 27 [E-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohr JP, Thompson JL, Lazar RM, et al. A comparison of warfarin and aspirin for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1444–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009;373:1849–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet 1997;349:1569–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CAST (Chinese Acute Stroke Trial) Collaborative Group. CAST: randomised placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet 1997;349:1641–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, Sivenius J, Smets P, Lowenthal A. European stroke prevention study. 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci 1996;143:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halkes PH, van Gijn J, Kappelle LJ, Koudstaal PJ, Algra A. Aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin alone after cerebral ischaemia of arterial origin (ESPRIT): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006;367:1665–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996;348:1329–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med 2008;359: 1238–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Coffey CS, Pearce LA. Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med 2012;367: 817–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hankey GJ, Hacke W, Easton JD, et al. Effect of clopidogrel on the rate and functional severity of stroke among high vascular risk patients: a pre-specified substudy of the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management and Avoidance (CHARISMA) trial. Stroke 2010;41:1679–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2013;369:11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston SC, Easton DJ, Farrant M, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med 2018;379: 215–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinohara Y, Katayama Y, Uchiyama S, et al. Cilostazol for prevention of secondary stroke (CSPS 2): an aspirin-controlled, double-blind, randomized non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:959–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James SK, Storey RF, Khurmi NS, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes and a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. Circulation 2012;125: 2914–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:2160–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Depta JP, Fowler J, Novak E, et al. Clinical outcomes using a platelet function-guided approach for secondary prevention in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke 2012;43:2376–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee M, Saver JL, Hong KS, Rao NM, Wu YL, Ovbiagele B. Antiplatelet regimen for patients with breakthrough strokes while on aspirin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2017. September;48:2610–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan Y, Jing J, Chen W, et al. Risks and benefits of clopidogrel-aspirin in minor stroke or TIA: Time course analysis of CHANCE. Neurology 2017;88: 1906–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong LK. Global burden of intracranial atherosclerosis. Int J Stroke 2006;1:158–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosemary J, Adithan C. The pharmacogenetics of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19: ethnic variation and clinical significance. Curr Clin Pharmacol 2007;2: 93–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hao Q, Tampi M, O’Donnell M, Foroutan F, Siemieniuk RAC, Guyatt G. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone for acute minor ischemic stroke or high risk transient ischemic attack: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018;363: k5108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bath PM, Woodhouse LJ, Appleton JP, et al. Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and dipyridamole versus clopidogrel alone or aspirin and dipyridamole in patients with acute cerebral ischaemia (TARDIS): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 superiority trial. Lancet 2018;391:850–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Albers GW, et al. Ticagrelor versus aspirin in acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2016;375: 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H, et al. The Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Treated with Ticagrelor and Aspirin for Prevention of Stroke and Death (THALES) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke 2019. February 12 [E-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorelick PB, Wong KS, Bae HJ, Pandey DK. Large artery intracranial occlusive disease: a large worldwide burden but a relatively neglected frontier. Stroke 2008;39:2396–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:993–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1305–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derdeyn CP, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, et al. Aggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trial. Lancet 2014;383:333–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turan TN, Nizam A, Lynn MJ, et al. Relationship between risk factor control and vascular events in the SAMMPRIS trial. Neurology 2017;88: 379–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L, Wong KS, Leng X, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy in stroke and ICAS: subgroup analysis of CHANCE. Neurology 2015;85:1154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Lin WH, Zhao YD, et al. The effectiveness of dual antiplatelet treatment in acute ischemic stroke patients with intracranial arterial stenosis: a subgroup analysis of CLAIR study. Int J Stroke 2013;8:663–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon SU, Cho YJ, Koo JS, et al. Cilostazol prevents the progression of the symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis: the multicenter double-blind placebo-controlled trial of cilostazol in symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. Stroke 2005;36:782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon SU, Hong KS, Kang DW, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination antiplatelet therapies in patients with symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis. Stroke 2011;42:2883–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toyoda K. Dual antiplatelet therapy using cilostazol for secondary stroke prevention in high-risk patients: the Cilostazol Stroke Prevention Study for Antiplatelet Combination (CSPS.com) (abstr). Paper presented at: International Stroke Conference of the American Heart Association; February 6th, 2019; Honolulu, HI. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amarenco P, Albers GW, Denison H, et al. Efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus aspirin in acute stroke or transient ischaemic attack of atherosclerotic origin: a subgroup analysis of SOCRATES, a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:301–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Minematsu K, Wong KS, et al. Ticagrelor in acute stroke or transient ischemic attack in Asian patients: from the SOCRATES trial. Stroke 2017;48:167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, et al. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet 2003;361:107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonati LH, Fraedrich G. Age modifies the relative risk of stenting versus endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis–a pooled analysis of EVA-3S, SPACE and ICSS. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011;41:153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonati LH, Dobson J, Featherstone RL, et al. Long-term outcomes after stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of symptomatic carotid stenosis: the International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS) randomised trial. Lancet 2015;385:529–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP, Barnett HJ. Endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis in relation to clinical subgroups and timing of surgery. Lancet 2004; 363:915–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Milgrom D, Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Antoniou SA, Torella F, Antoniou GA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of very urgent carotid intervention for symptomatic carotid disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2018;56:622–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindblad B, Persson NH, Takolander R, Bergqvist D. Does low-dose acetylsalicylic acid prevent stroke after carotid surgery? A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. Stroke 1993;24:1125–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor DW, Barnett HJ, Haynes RB, et al. ASA and Carotid Endarterectomy (ACE) Trial Collaborators. Low-dose and high-dose acetylsalicylic acid for patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1999; 353:2179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones DW, Goodney PP, Conrad MF, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy reduces stroke but increases bleeding at the time of carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg 2016;63:1262–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:e16–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naylor AR, Ricco JB, de Borst GJ, et al. Management of atherosclerotic carotid and vertebral artery disease: 2017 clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2018;55:3–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKevitt FM, Randall MS, Cleveland TJ, Gaines PA, Tan KT, Venables GS. The benefits of combined anti-platelet treatment in carotid artery stenting. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2005;29: 522–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gordon Perue GL, Narayan R, Zangiabadi AH, et al. Prevalence of vertebral artery origin stenosis in a multirace-ethnic posterior circulation stroke cohort: Miami Stroke Registry (MIAMISR). Int J Stroke 2015;10:185–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]